1 Introduction on Metacognition in Language Teaching

This Element was inspired by my experience at a forum on methodology in applied linguistics in Osaka, Japan. During the event, a teacher commented on the importance of my presentation on metacognition in language teaching and learning, urging me to delve deeper into this topic. This encouragement resonated with me, and I decided to explore the subject further through this Element for several reasons. First, I currently teach in Macao, where incorporating metacognition into language teaching and learning comes with substantial challenges; many students here struggle with motivation in language learning. I believe that fostering metacognitive awareness could provide useful strategies to help these students become more engaged, autonomous learners. However, I also believe that we need more understanding on this topic, especially in challenging situations where motivation is lacking. The cultural context of Macao, with its unique blend of Chinese and Portuguese influences, adds another layer of complexity to this issue. Unlike many other regions, students in Macao mostly do not face pressure from high-stakes testing and societal expectations. This is largely because the society and government have casinos as one of the biggest sources of income, which can further dampen their intrinsic motivation to learn languages. The relatively stable economic achievement provided by the casino industry might lead students to feel less urgency in pursuing academic excellence, including language proficiency. To address this, educators must explore innovative approaches that resonate with students’ experiences and interests, potentially integrating technology and collaborative learning to spark curiosity and engagement. Additionally, professional development for teachers on how to effectively implement metacognitive strategies in the classroom could be crucial in overcoming these challenges. Ultimately, a deeper exploration of the interplay between metacognition and motivation in this context could lead to more effective teaching practices and improved language learning outcomes.

Second, I have an extensive track record of publications involving metacognition in language teaching. My research has delved deeply into how metacognitive strategies can enhance second language vocabulary acquisition and writing, providing insights into both theoretical frameworks and practical applications. These publications have explored various aspects of metacognition, such as self-regulation, self-efficacy, and strategic planning, and their impact on learners’ ability to acquire and apply new language skills effectively. Now is an opportune time to share my findings with a broader audience, enabling readers to better understand this crucial matter.

Finally, although metacognition is a well-recognised topic in educational psychology, it has not received the attention it deserves in the context of language teaching. In educational psychology, metacognition is celebrated for its role in enhancing learning processes, promoting self-awareness, and improving problem-solving skills across various disciplines (Flavell, Reference Flavell1979). However, when it comes to language teaching, the application of metacognitive strategies remains underexplored and underutilised. After Wenden (Reference Wenden1998) highlighted this issue in language learning, there still hasn’t been sufficient attention given to it. This oversight is significant, given the potential benefits that metacognition can bring to language learners, such as improved comprehension, enhanced vocabulary acquisition, and greater overall language proficiency. The lack of emphasis on metacognition in language education may stem from traditional teacher-centred methods that prioritise rote memorisation and repetitive practice over reflective and strategic learning, particularly in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context. Such approaches often fail to engage learners in meaningful ways or to develop their ability to think critically about their own learning processes. Integrating metacognitive approaches into language curricula can empower students to take control of their learning, fostering a deeper understanding and more meaningful engagement with the language. Addressing this gap in attention could lead to innovative teaching practices that not only enhance language skills but also equip learners with lifelong learning strategies. By fostering a metacognitive mindset, educators can help students become more self-directed, adaptable, and effective learners, capable of navigating the complexities of language acquisition and beyond.

As mentioned earlier, interest in this area has grown following Wenden’s (Reference Wenden1998) seminal publication; however, comprehensive resources remain needed, which describe how to apply metacognitive strategies in language pedagogy (Rose, Reference Rose2012). This Element aims to fill that gap by synthesising the extant literature, providing practical insights, and highlighting the role of metacognitive training in language learning. By doing so, I hope to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in language teaching and offer tools for educators seeking to improve students’ language-learning experiences through enhanced metacognitive awareness.

At least three notable books have addressed metacognition in language teaching. The first is Goh and Vandergrift’s (Reference Goh and Vandergrift2021) work on metacognition in listening. They examine both the theory of metacognition in listening and the adoption of associated strategies in the English as a second language (ESL)/English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom. The focus is on the often understudied area of second language communication skills, that is, listening. Goh and Vandergrift (Reference Goh and Vandergrift2021) reviewed listening-related research, outlining how listening instruction has traditionally been delivered and pointing out the drawbacks of these approaches. Pitfalls include a lack of understanding of the listening process itself and an overemphasis on input comprehension as the exemplar of listening skills. The authors argued for a learner-centred approach to listening instruction that integrates metacognitive strategies. These techniques are meant to help learners understand how they learn, thus teaching students to self-correct and improve their overall listening experience.

The second one is Haukås et al.’s (Reference Haukås, Bjørke and Dypedahl2018) discussion of metacognition in language teaching and learning. This complete volume is divided into theoretical and empirical sections, offering a multifaceted view of metacognition. It covers a range of perspectives, including metalinguistic and multilingual awareness as well as language learning and teaching in both second-language (L2) and third-language (L3) settings. They also summarise empirical studies related to writing, teacher education, and classroom communication. Its breadth is remarkable: this work features numerous contexts and views on metacognition in language learning and teaching. One highlight of Haukås et al.’s (Reference Haukås, Bjørke and Dypedahl2018) work is their accentuation of the importance of metacognition in language teacher education. The authors advocate for a stronger focus on developing metacognitive skills among experienced and future teachers. They stress that fostering an interest in metacognition is essential for teachers to enhance their own instructional practices and to help students develop these critical skills. This process mandates knowledge sharing and collaboration.

The third one, authored by L. Teng (Reference Teng2022), offers an in-depth exploration of self-regulation within the realm of second language learning and teaching. This pivotal work applies self-regulation theory to language acquisition, presenting a groundbreaking conceptual framework designed to evaluate multidimensional self-regulated learning strategies. By connecting these strategies with social, psychological, and linguistic factors, Teng provides a holistic view of how learners can effectively manage their own language learning processes. She delves into the practical applications and contributions of self-regulated learning (SRL) to second and foreign language (L2) writing, examined from both sociocognitive and sociocultural perspectives. This work showcases a thorough and up-to-date review of the conceptual and methodological issues surrounding SRL, as well as the latest research on its application in L2 learning and teaching contexts. L. Teng’s volume further details the design and outcomes of a comprehensive large-scale project that includes both observational and intervention studies, investigating SRL strategies in L2 writing. This research highlights the critical importance of a cross-disciplinary understanding of SRL strategies, emphasising their role in advancing theoretical frameworks and extending their applications to L2 education broadly, with a particular focus on L2 writing. Additionally, this work discusses various strategy questionnaires and their validation processes, offering valuable insights into the discussion of self-regulated learning strategies. By providing these tools and methodologies, L. Teng’s work contributes significantly to enhancing the effectiveness of language education, empowering learners to become more autonomous and proficient in their language acquisition endeavours.

Contributing to the existing body of knowledge, this Element reports on metacognition in reading, writing, listening, and vocabulary learning along with the assessment of metacognition in language teaching. There is little doubt that metacognition is instrumental to effective language learning and teaching. Through this Element, readers will come to realise the importance of metacognitive awareness in language pedagogy. Successful language learners are aware of the complexities of the target language they hope to master, the hurdles involved in the learning process, their own beliefs about language learning and teaching, and techniques that can be employed to overcome these obstacles. The same principles apply to language educators: to deliver more impactful lessons, teachers must not only be aware of their pedagogical practices and beliefs but also understand how different instructional methods suit students’ personal profiles and environments. It is similarly necessary to remember that teachers are lifelong learners themselves, continually refining their understanding of the language they teach and searching for ways to make their lessons more appealing and beneficial to students.

Against this backdrop, this Element represents a much-needed contribution to the field of language teaching, including listening, writing, reading, and vocabulary learning. Despite the limitations of insufficient information on understanding the role of metacognition in speaking, this Element spotlights the importance of metacognitive awareness across multiple domains of language education, emphasising its role in enhancing both teaching and learning processes. By highlighting the critical need for metacognitive skills, this Element provides ample justification for the topic’s theoretical exploration and practical application. It underscores how metacognitive awareness can lead to more effective language acquisition by enabling learners to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning strategies. Moreover, this Element addresses the essential need to cultivate metacognitive skills not only among learners but also among pre-service and in-service teachers. By doing so, it helps to bridge the gap between theory, research, practice, and assessment, ensuring that educational practices are informed by the latest insights and methodologies. This alignment is crucial for developing a more integrated approach to language teaching, where theoretical concepts are seamlessly translated into classroom strategies and assessment tools. This Element is indispensable for anyone involved in language teaching, as it contains tactical guidance for fostering metacognitive awareness. It offers educators practical strategies to enhance the general effectiveness of language teaching, equipping them with the tools to nurture independent, reflective, and strategic learners. By integrating these approaches into their teaching practices, educators can significantly improve learning outcomes and contribute to the development of lifelong language learning skills among their students.

2 Understanding Metacognition

Metacognition is key in distinguishing effective language learners from less effective ones; it significantly affects students’ decision making and success in acquiring a language. Language teachers are crucial in nurturing students’ metacognitive awareness, namely by modelling metacognitive strategies during instruction. It is equally critical for teachers to possess a metacognitive understanding of their pedagogical methods in order to enhance students’ language-learning experiences. Thus, the comprehension of metacognition is imperative to consider.

2.1 An Understanding of Metacognition from Educational Psychology

2.1.1 Definition of Metacognition

The concept of metacognition has long intrigued educational psychologists, and its importance in academic achievement is well established. Metacognitive knowledge improves the quality and effectiveness of academic learning (Schraw, Reference Schraw1998). This awareness not only improves self-regulated learning (SRL; Wenden, Reference Wenden2002) but also fosters learner autonomy (Victori & Lockhart, Reference Victori and Lockhart1995), allowing students to take charge of their educational journeys and adapt to various learning environments. Furthermore, metacognitive skills are closely linked to scholastic achievement, as they empower learners to set goals, monitor their progress, and adjust their approaches to overcome challenges (Zimmerman & Bandura, Reference Zimmerman and Bandura1994). By cultivating these skills, students can achieve higher levels of academic success and develop the resilience needed to tackle complex tasks. Fairbanks et al. (Reference Fairbanks, Duffy and Faircloth2010) contended that teachers who recognise metacognition’s place in learning can better support students’ development. By integrating metacognitive strategies into their teaching practices, educators can create a more supportive learning environment that encourages students to reflect on their thinking, evaluate their understanding, and apply their knowledge more effectively.

Due to its interdisciplinary nature and multiple theoretical perspectives, metacognition has no universal definition. However, in the field of educational psychology, the description that Flavell provided in the 1970s is widely regarded as foundational. Known for his theory-of-mind approach, he explained metacognition as ‘the active monitoring and consequent regulation and orchestration of these processes in relation to the cognitive objects or data on which learners bear, usually in the service of some concrete goal or objective’ (Flavell, Reference Flavell and Resnick1976, p. 232). A core feature of this definition is that metacognition involves applying the theory of mind to cognitive tasks.

The theory of mind refers to one’s cognitive ability to ‘attribute mental states, such as beliefs, desires, and intentions, to oneself and others’ (Lockl & Schneider, Reference Lockl and Schneider2006, p. 16). Boekaerts (Reference Boekaerts1997) expanded on this notion by stating that metacognition encompasses not only a theory of mind but also a ‘theory of self, theory of learning, and learning environments’ (p. 165). Building on these ideas, Flavell (Reference Flavell1979) further defined metacognition as learners’ awareness of their cognitive and executive processes with the aim of regulating various aspects of cognitive activities. He proposed three domains within metacognition: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, and metacognitive strategies. Additionally, Flavell (Reference Flavell1979) conceptualised metacognition as consisting of four components: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals, and strategy activation.

2.1.2 Frameworks on Understanding Metacognition

Flavell (Reference Flavell1985) introduced a holistic, two-dimensional framework to clarify metacognition. These dimensions are knowledge of metacognition (person, task, and strategies) and regulation of metacognition (planning, monitoring, and evaluating). His model captures both the cognitive nature of metacognition and this concept’s role in knowledge regulation. Many researchers have adopted the classification to operationalise metacognition. Flavell’s framework affords teachers a richer sense of students’ metacognition, enabling instructors to more readily facilitate change in students’ learning processes and outcomes. For instance, learners’ comprehension of person-oriented variables influences their decision making when choosing strategies, monitoring these techniques’ application, and transferring them to new learning tasks. Similarly, learners’ knowledge of task-related variables empowers them to select approaches suited to specific activities. Learners’ understanding of different strategies also guides them in making informed decisions about options, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of their educational endeavours. Understanding the notions of planning, monitoring, and evaluating is of utmost importance for teachers and learners alike. A solid grasp of planning allows teachers to develop well-structured lessons that align with desired learning outcomes. Moreover, by closely monitoring students’ progress, teachers can identify individual strengths and weaknesses and offer targeted support to encourage optimal learning. Evaluation enables teachers to assess learning outcomes, provide timely and constructive feedback, and foster students’ growth. Meanwhile, learners benefit from understanding planning, monitoring, and evaluating by being able to set clear and achievable goals, track their progress, and make necessary adjustments. They employ SRL strategies to appraise their own performance, reflect on their comprehension, and improve by taking ownership of their education and becoming self-directed learners.

Also in the realm of metacognition, scholars have embraced a framework that categorises metacognitive knowledge into three types based on respective processes: declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge (Paris et al., Reference Paris, Cross and Lipson1984). Declarative knowledge refers to factual understanding about oneself (i.e., a sense of one’s skills, intellectual capacities, affective factors, and cognitive abilities). For instance, learners may possess declarative knowledge when they recognise their strengths and weaknesses in a certain subject area or discover their preferred learning styles. Procedural knowledge, on the other hand, calls for making decisions about task implementation by employing proper strategies (Paris et al., Reference Paris, Cross and Lipson1984). Let us consider learning to swim. At first, despite receiving directions from an instructor, a learner may struggle to swim until they have practiced a few times. Repetition leads to this task becoming implicit knowledge, which resides in the learner’s subconscious. Such knowledge is difficult to quantify; it arises from practice and experience. Conditional knowledge pertains to the decision-making process about when, where, and why specific strategies should be used to accomplish particular tasks (Schraw, Reference Schraw1998). This type of knowledge is crucial for applying suitable techniques and allocating resources efficiently. Conditional knowledge enables learners to act as guides in determining when and how strategies can be adopted to execute a task. For instance, a student may possess conditional knowledge when they recognise that using mnemonic devices is beneficial for memorising information and then identifies fitting contexts in which to deploy this approach.

According to Brown (Reference Brown, Weinert and Kluwe1987), metacognitive regulation differs from metacognitive skills, as it refers to how people detect distracting internal and external stimuli in order to sustain effort over time for executive functions. Schraw (Reference Schraw1998) elaborated on planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Planning involves one’s ability to use appropriate strategies and resources to complete tasks. It reflects the thoughtful consideration of steps required to accomplish a goal and the successful coordination of one’s approach. By engaging in careful planning, learners can optimise their efforts and increase their chances of success. Monitoring refers to one’s capacity to check their performance during tasks; it involves keeping an eye on one’s progress, identifying deviations or errors, and adjusting to stay on track. Effective monitoring allows learners to address issues as they arise, which helps learners stay engaged in the educational process. Evaluating calls for assessing one’s regulatory processes and learning outcomes, namely by thinking about the utility of chosen strategies, the quality of one’s work, and overall success in the learning experience. This metacognitive skill enables learners to analyse their own performance and make deliberate decisions for future improvements. Schraw and Dennison (Reference Schraw and Dennison1994) proposed two additional metacognitive strategies based on debugging and information management. Debugging strategies involve noting and rectifying lapses in comprehension and performance. Learners with this skill can acknowledge misconceptions, thus developing deeper understanding and more precise performance. Information management strategies pertain to processing, organising, elaborating, and summarising task-related information. These strategies aid learners in manipulating the information they encounter to promote comprehension and retention.

Anastasia Efklides has offered insight into metacognition as well. For example, Efklides (Reference Efklides, Chambers, Izaute and Marescaux2001) stated that learners’ metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive experiences are closely connected. These experiences correspond to learners’ feelings about their own knowledge, their opinions about their own understanding, their perceptions of task difficulty, and their assessments of confidence and correctness when performing tasks. Numerous factors can influence learners’ metacognitive experiences: task complexity; prior experiences; personal attributes (e.g., cognitive ability, personality, and self-concept); and, of course, metacognitive knowledge. Efklides (Reference Efklides2006) further described metacognition as a higher-order cognitive model that interacts with object-level cognition through monitoring and control functions. The meta level receives input from the object level through monitoring, which then informs the control function to adapt cognitive processes accordingly. Metacognitive experiences are seen as complex inferential processes that reflect one’s progress towards a goal; this feedback is delivered in either an affective or cognitive context. These experiences are critical in activating affective or cognitive regulatory loops, in turn guiding self-regulatory mechanisms. Efklides (Reference Efklides2008) expanded on metacognition by specifying it across three domains in line with Flavell (Reference Flavell1979): metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, and metacognitive strategies. In particular, metacognitive experiences encompass one’s conscious awareness and feelings during information processing (e.g., the feeling of knowing, the effort involved, solutions’ accuracy, perceived difficulties, familiarity with the content, and personal confidence). These experiences are crucial for individuals to assess task performance. Metacognitive knowledge and experiences contribute to the monitoring aspect of cognition, while metacognitive skills pertain to its control. In the learning process, one’s metacognitive experiences – shaped by subjective and affective responses – can greatly affect one’s general metacognitive framework. For example, feelings such as satisfaction or anxiety can influence a learner’s future strategy use and shape their metacognitive knowledge. Metacognitive experiences play a significant role in the classroom, where students display a range of emotions. Efklides (Reference Efklides2008) framed metacognition as a fully conscious endeavour, with people being entirely aware of their monitoring and control processes. She also argued that metacognition is individualised and that external factors minimally affect it; that is, metacognition represents a personal part of the learning process. The classification of metacognition’s sub-components is important. If this concept concerns both how one monitors and controls their own thinking, then it naturally covers a suite of phenomena (e.g., introspective and self-regulatory processes). It is accordingly necessary to identify distinguishable sub-components of metacognition. Certain facets – namely knowledge, strategies, and experiences – constitute a classic framework.

2.1.3 Key Theoretical Stances

The subject of metacognition has drawn substantial attention from researchers and educators in various disciplines given its relevance to learning, problem solving, reasoning, and conceptual understanding across learners, topics, domains, tasks, and contexts. However, the challenge of comprehending metacognition becomes apparent as different definitions, constructs, assumptions, processes, and mechanisms are proposed. Azevedo (Reference Azevedo2020) contended that, despite clear progress in this field, more theoretical work is needed to cohesively define metacognition and its constituent parts. Veenman, van Hout-Wolters, and Afflerbach (Reference Veenman, Van Hout-Wolters and Afflerbach2006) rightly stated that ‘while there is consistent acknowledgement of the importance of metacognition, inconsistency marks the conceptualisation of the construct’ (p. 4). Norman et al.’s (Reference Norman, Pfuhl and Saele2019) review identified major advancements in metacognition research and summarised the term’s definitions using three branches. The first branch revolves around the extent to which metacognition is a pre-conscious, pre-reflective, non-representational, or pre-verbal form of thinking. This line of enquiry explores the foundational aspects of metacognitive processes that occur before conscious awareness or introspection. The second branch shifts the focus from the mere existence of metacognitive thinking to understanding how people engage in metacognitive processes and proactively manage important tasks. This branch investigates the active regulation and control of cognitive processes through metacognition and explores how people monitor and alter their cognitive strategies to optimise learning and performance. The third branch concerns developmental aspects of metacognitive abilities across the lifespan, particularly whether these skills change with age. This research agenda considers how cognitive fluency and processing time may influence metacognitive functioning and whether metacognitive abilities decline in adulthood.

2.1.4 Reflection

Here, I have attempted to summarise metacognition based on themes and keywords from the literature. I hope this synthesis sheds light on the concept’s intricacies. First, metacognition is often described as ‘cognition about cognition’, meaning that metacognition involves thinking about personal cognitive processes. It goes beyond simply engaging in cognitive activities to being aware of and monitoring one’s thinking. Metacognition has also been deemed ‘information-based’, which suggests that various factors – including conscious and non-conscious ones – affect metacognitive processes. For example, the speed at which an answer comes to mind or a person’s familiarity with a task domain can shape metacognitive judgements. A dynamic interplay thus exists between conscious and non-conscious aspects of metacognition. Furthermore, metacognitive feelings are typically described as ‘experience-based’: these feelings refer to one’s subjective perceptions of their own cognitive processes and encompass elements such as the feeling of knowing, the effort involved in a task, solution accuracy, obstacles, content familiarity, and confidence. These experiences grant people valuable feedback on their cognitive performance. Metacognitive processes are conscious in both cases, as metacognition involves higher-order mental representations indicative of consciousness. People therefore need to be cognisant of their own thinking and to perform reflective processes that transcend automatic or non-conscious cognitive activities.

2.2 An Understanding of Metacognition in Language Teaching and Learning

2.2.1 Definition of Metacognition in Language Teaching and Learning

The field of language teaching has increasingly acknowledged the role of metacognitive awareness for learners. Metacognitive awareness is crucial in language teaching and learning, especially in foreign-language and L2 education. Educators who prioritise cognitive strategies and self-directed language learning know the significance of incorporating metacognitive awareness into curricula. Researchers have investigated the link between metacognition and successful language learners (Anderson, Reference Anderson and Griffiths2008). Common tenets of metacognitive instructional models include activating students’ prior knowledge, reflecting on their knowledge and learning goals, explaining and modelling strategies (i.e., by the teacher), and involving students in setting goals for monitoring the learning process. The teacher plays a critical part in explaining, modelling, and creating an environment conducive to reflective discussions. However, metacognition has not yet received the attention it deserves within language teaching and learning.

Wenden (Reference Wenden1987) may be the first to highlight the roles of metacognition in language learning and teaching; he played a pioneering role in this field. Building on Flavell’s work, Wenden identified three types of metacognitive knowledge: person knowledge, task knowledge, and strategy knowledge. His contributions to the realm of metacognition in language learning and teaching underlined these categories’ importance. Person knowledge refers to one’s understanding of their cognitive processes, strengths, and weaknesses in relation to language learning. It involves self-awareness and self-reflection, allowing individuals to recognise their preferred learning styles, language aptitude, and motivation levels. By developing person knowledge, learners become more attuned to their own educational needs and can make informed decisions about their language learning approaches. Task knowledge pertains to the purpose, demands, and requirements of specific language learning tasks. It involves being able to evaluate task objectives and to identify the resources required for completion. Task knowledge enables learners to approach language learning tasks with a clear sense of what is expected and how to achieve desired outcomes. Strategy knowledge encompasses the awareness and use of learning techniques for effective language acquisition (e.g., to enhance language learning efficiency); this type of knowledge equips learners with a repertoire of strategies, such as note taking, summarising, self-assessment, and goal setting, so they may choose which tactics to employ in different language learning contexts. Learners who nurture these forms of metacognitive knowledge can take more active, autonomous roles in their language learning.

2.2.2 Frameworks on Understanding Metacognition in Language Teaching and Learning

In Wenden’s (Reference Wenden1998) framework, metacognitive knowledge should be viewed as a prerequisite for SRL. Such knowledge guides planning (i.e., early in one’s learning process) and monitoring processes as one moves through learning tasks. It comprises self-observation, assessment of progress and challenges, and decisions about remediation. Furthermore, metacognitive knowledge serves as a criterion for appraising a finished learning task. However, metacognitive knowledge alone may be insufficient for certain aspects of planning: domain knowledge plays a complementary and essential role. Metacognitive knowledge serves two distinct functions. First, it is motivational in that it energises the self-regulation involved in learning. Second, it is cognitively oriented because it directly moulds those processes. Language educators should acknowledge the significance of incorporating knowledge about learning into tasks designed to help language learners build learning strategies. People with strong metacognitive awareness are better prepared to face the obstacles inherent to second language learning. They also tend to demonstrate a firm belief in their ability to succeed in language learning and take proactive measures to realise their educational pursuits (Wenden, Reference Wenden1998). Recognising the role of metacognition in second language learning can hold value for second language acquisition. Numerous attributes, such as age, language aptitude, and motivation, can influence one’s extent of person-based knowledge. Bringing metacognitive awareness into language teaching and learning enables students to grapple with challenges, trust in their language learning skills, and work towards attaining associated goals.

The process of gaining declarative knowledge is closely related to metalinguistic awareness. Metalinguistic awareness refers to one’s ability ‘to consider language not just as a means of expressing ideas or communicating with others but also as an object of inquiry’ (Gass & Selinker, Reference Gass and Selinker2008, p. 359). It involves introspection about the structure, rules, and components of language itself. Learners possessing metalinguistic awareness can develop language awareness, which then enhances their metalinguistic awareness. Language awareness encompasses explicit knowledge of language and involves conscious perception and sensitivity to the learning, teaching, and use of language (Svalberg, Reference Svalberg2007). It goes beyond deploying language as a communication tool; people with language awareness have a conscious understanding of, and desire to explore, language’s structures, functions, and conventions. Within the area of metacognition, explicit knowledge about language learning processes falls under declarative metacognitive knowledge. This knowledge involves being aware of the strategies and principles that facilitate language learning (e.g., knowledge of learning techniques, learning styles, and language acquisition approaches). Declarative metacognitive knowledge enables individuals to deliberately reflect on their learning processes, make educated decisions about their learning tactics, and adapt these approaches to suit their needs. Learners obtain explicit knowledge about language structures and functions through metalinguistic awareness and language awareness. This understanding supports their metacognition concerning language learning processes, and they can navigate their language learning journey more effectively. Learners with explicit knowledge can also actively track their progress, measure their language proficiency, and choose language learning strategies wisely.

2.2.3 Key Theoretical Stances

There are some key theoretical stances regarding metacognition in language teaching and learning. Anderson (Reference Anderson2002, Reference Anderson and Griffiths2008) outlined five components of metacognition about learning to be developed in the language classroom: (1) preparing and planning for learning (i.e., students reflect on their goals and identify strategies to achieve them); (2) allowing students to make conscious decisions about their learning strategies and processes; (3) monitoring strategy use and encouraging students to track the effectiveness of their chosen techniques; (4) orchestrating diverse approaches (i.e., teaching students to combine multiple strategies); and (5) evaluating strategy use and learning (i.e., cyclically asking questions about goals, techniques used, and possible alternatives). Anderson emphasised that these components work together to enhance language learners’ metacognitive skills.

Rose (Reference Rose2012) criticised the current measurement of language learning strategies, arguing that available practices are usually unreliable. He called for clearer definitions of strategic learning and the development of more accurate and qualitative instruments to assess this construct. Rose further contended that it is essential to examine strategic learning not only based on a student’s self-regulation during a learning task but also in terms of their cognitive and behavioural strategies. Research frameworks that include both self-regulation and strategy use need to be explored to fully illustrate strategic learning. Additionally, theories must remain flexible to encourage new models of strategic learning. The need for strategic learning highlights the importance of metacognitive awareness in language teaching.

Haukås (Reference Haukås, Haukås, Bjørke and Dypedahl2018) defined metacognition as ‘an awareness of and reflections about one’s knowledge, experiences, emotions and learning in the contexts of language learning and teaching’ (p. 13). Haukås also linked metacognitive awareness with language awareness. Metacognition refers to broad reflections on one’s knowledge, experiences, emotions, and learning across all domains, whereas language awareness pertains to reflections in a trio of sub-domains: language, language learning, and language teaching. These domains are interconnected, and metacognition in language teaching often involves simultaneous reflection in all three. Investigations into teachers’ and learners’ beliefs, the use of learning strategies, metalinguistic and multilingual awareness, intercultural awareness, and self-efficacy all represent aspects of metacognition. Such analyses shed light on how people perform metacognitive processes in language learning and teaching contexts. By examining their own beliefs, students and teachers can gain insights into their personal cognitive processes, attitudes, and motivations around language learning. Learning strategy use involves metacognitive decision making, where people consciously choose and deploy techniques to enhance their language learning outcomes (Oxford, Reference Oxford1990). Metalinguistic and multilingual awareness concern one’s ability to scrutinise the structure, applications, and relationships between languages. Intercultural awareness entails reflecting on the cultural dimensions of language and communication. Finally, self-efficacy relates to one’s belief in their ability to succeed in language learning tasks (F. Teng, 2024d).

L. Teng and Zhang (Reference Teng and Zhang2022) asserted that self-regulation principles and metacognitive awareness practices can enrich L2/foreign language learning and teaching. L. Teng (Reference Teng2022) bridged SRL with language learning strategies, stressing the learning process and students’ pivotal roles within it. ‘SRL’ and ‘language learning strategies’ are multifaceted terms that include cognitive, metacognitive, social-behavioural, and motivational components. This rich framework allows for the incorporation of control mechanisms related to cognition, behaviour, the environment, and motivation. Scholars can therefore inspect various dimensions of learners’ SRL development. For instance, L. Teng (Reference Teng2024) pointed out the importance of exploring motivational regulation and social behaviour in L2 writing settings. The process of L2 writing can be evaluated through a multidimensional lens, including determining how learners set goals and subsequently regulate their cognition, motivation, and behaviour during the writing process. This point of view acknowledges that these components are often influenced by learners’ goals and diverse contextual features. Scholars and educators can gain valuable insights into the metacognitive aspects of language learning by considering these interconnected factors. L. Teng’s ideas reinforce the significance of metacognition in language learning and teaching. By contemplating the interplay between SRL and language learning strategies, educators can promote learners’ autonomy, self-regulation, and strategic thinking. This understanding fosters instructional interventions that support learners in becoming proficient language users. Metacognitive practices also convey the need to empower learners to be active participants in their own learning (i.e., by setting goals, tracking their progress, and adjusting when necessary). As Zhang and Zhang (Reference Zhang, Zhang and Liontas2018) said, metacognition – described as one’s awareness of oneself, the task at hand, employed strategies, and personal readiness – is fundamental to students’ agency and independence.

F. Teng et al. (Reference Teng, Qin and Wang2022) assembled a model to demystify metacognition, delineating this construct as the monitoring and control of cognition (see Figure 1). This framework maintains that metacognition operates on two principal levels: the observational level, where one tracks and assesses their cognitive activities; and the managerial level, where one fine-tunes these activities. This dual functionality underscores metacognition’s role in fostering one’s conscious awareness and mastery over cognitive functions. F. Teng et al. (Reference Teng, Qin and Wang2022) further separated metacognition into three stages – acquisition, retention, and retrieval – that connect the observational and managerial dimensions. The model posits that metacognition is complex and has three interwoven domains: metacognitive knowledge (awareness of one’s cognitive processes); metacognitive experiences (one’s lived subjective experience of cognition); and metacognitive skills (one’s application of strategies such as planning, monitoring, and evaluation). Central to this triad is the act of reflection, which is crucial for the cyclical process of planning, monitoring, and evaluating. F. Teng (Reference Teng, Wen, Adriana, Mailce and Teng2023a) expanded the discourse on metacognition by emphasising its deeply personal nature. F. Teng (Reference Teng, Wen, Adriana, Mailce and Teng2023a) noted that metacognition is not merely a set of abstract cognitive processes but a reflection of a person’s evolving understanding and command over their own thinking and learning. This attribute is pivotal in educational settings, therapeutic contexts, and self-improvement; it dictates how one approaches new information and challenges. F. Teng (Reference Teng, Wen, Adriana, Mailce and Teng2023a) also elaborated on the symbiotic relationship between the pillars of metacognition (i.e., metacognitive knowledge, experiences, and skills). Metacognitive knowledge – one’s understanding of their cognitive strengths, weaknesses, and strategies – is the basis upon which metacognitive experiences are built. These real-time, conscious experiences of cognition inform ongoing learning. Metacognitive skills, including the capacities to plan, monitor, and appraise one’s cognitive strategies, are honed through applying knowledge and reflecting on one’s experiences. Moreover, F. Teng (Reference Teng, Wen, Adriana, Mailce and Teng2023a) argued that this tripartite framework is not static but rather develops with practice. Individuals become more adept at deploying metacognitive strategies as they perform complex tasks, leading to a more sophisticated understanding of their learning processes. This iterative reflection and adaptation make metacognition a powerful ally in language learning.

Figure 1 Multifaceted elements of metacognition

Another interesting aspect of metacognition is that it possesses trait-like and state-like elements (Sato, Reference Sato, Li, Hiver and Papi2022). This dichotomy is key for understanding how metacognitive abilities can vary between and within people over time. Metacognition, as a trait, refers to enduring qualities that define an individual’s usual approach to learning. Some learners naturally engage in metacognitive thinking more regularly than others. Numerous factors can contribute to this tendency, including prior educational experiences, personal dispositions towards reflection, and innate cognitive abilities. Trait-like metacognition is relatively stable across settings and tasks, shaping how a person typically interacts with new information and problem-solving situations. A trait-like metacognitive approach during language learning might manifest in the habitual use of specific techniques for planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s own language development. Certain learners might consistently self-assess their progress in vocabulary acquisition or regularly reflect on their reading comprehension strategies. Conversely, the state of metacognition is more variable and context-dependent. A learner might exhibit strong metacognitive skills under particular circumstances (e.g., during a structured writing task where they are actively planning and revising their work) but not others (e.g., an impromptu speaking exercise). State-like metacognition is dynamic and can be enhanced or suppressed by issues such as stress, motivation, or perceived task difficulty. Language teachers can foster state-like metacognitive engagement among students by designing activities that prompt metacognitive thinking and by creating a classroom environment that encourages introspection and self-regulation.

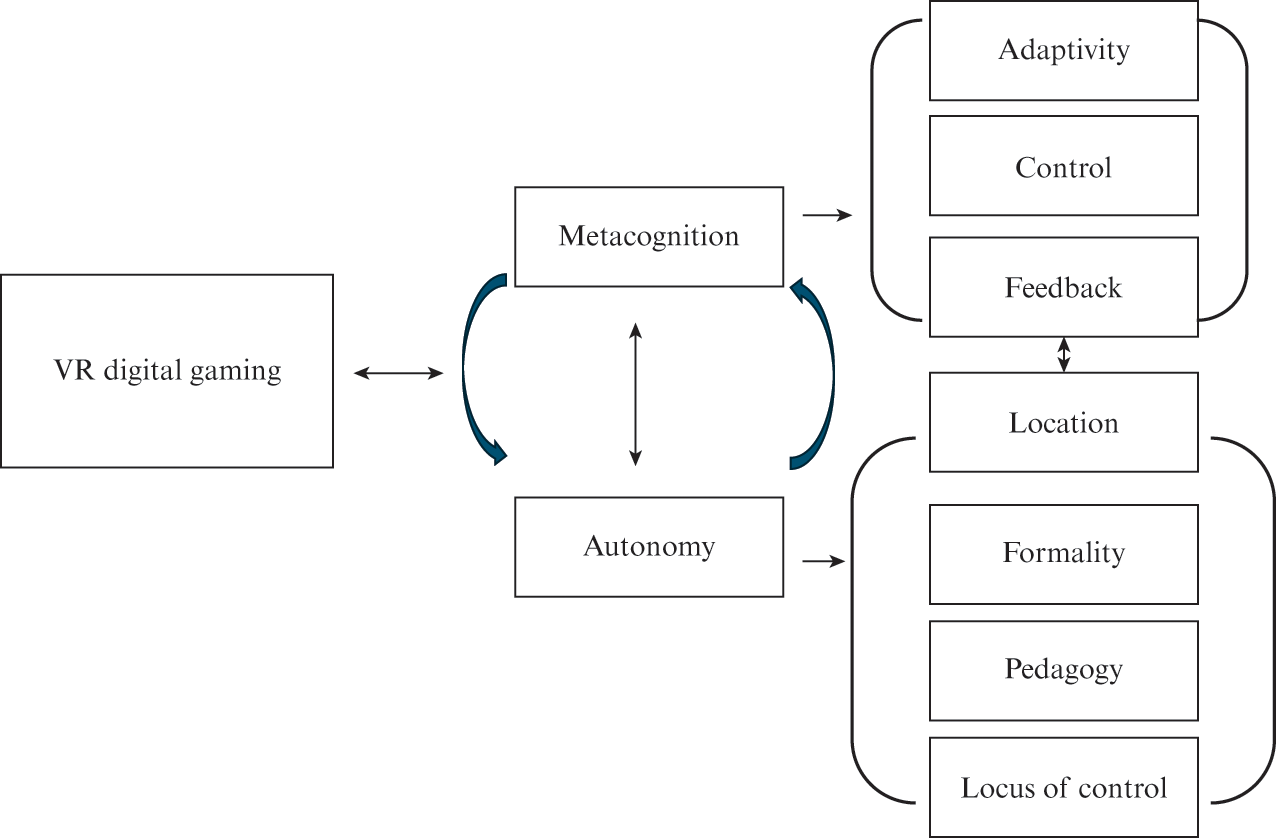

F. Teng (Reference Teng2024a) proposed a framework (Figure 2) that elucidates the operational dynamics of students participating in virtual reality digital gaming. Central to this framework is an emphasis on metacognitive awareness for fostering learners’ autonomy and vice versa. The reciprocal relationship between metacognition and autonomy highlights individuals’ capacity to self-regulate and navigate learning experiences within virtual reality digital gaming contexts.

Figure 2 Metacognition and autonomy in virtual reality digital gaming

2.2.4 Reflection

In my attempt to summarise and understand the intricate dynamics of metacognition, I have come to realise that it is not merely an abstract concept but a practical tool that can transform the educational landscape. The increasing acknowledgement of metacognitive awareness in the field of language teaching highlights its necessity for learners to effectively harness their resources, identify linguistic challenges, and set achievable goals. This understanding resonates with my experiences in language education, where fostering metacognitive skills has proven essential in guiding students towards autonomy and success. The ability for students to reflect on their cognitive processes is crucial in enabling them to take charge of their learning journeys.

As an educator, I have witnessed first hand the transformative power of incorporating metacognitive strategies into curricula. It has become evident that when students are encouraged to activate prior knowledge, reflect on their learning goals, and engage in goal-setting, they develop a deeper understanding of their learning processes. This approach not only enhances their academic achievements but also prepares them for lifelong learning. The theoretical frameworks and insights have further enriched my understanding of how metacognitive awareness can be cultivated in language classrooms. The frameworks underscore the importance of creating a language learning environment where reflective discussions are encouraged, and where students are guided in developing their metacognitive skills. However, despite its recognised importance, metacognition still lacks the attention it deserves within language teaching and learning. This reflection has reinforced my commitment to advocating for its integration into language teaching and learning practices.

2.3 An Understanding of Metacognition Based on My Teaching and Research Experiences

I currently teach at Macao Polytechnic University. Macao is a unique region whose residents enjoy numerous privileges, including priority access to educational institutions and job opportunities with high salaries. The term ‘job hunting’ may not be entirely appropriate here, as many positions are reserved for Macao residents. Consequently, students in Macao seldom face great stress in terms related to their schooling or employment. The most perplexing aspect of language teaching in Macao is student involvement – many learners lack interest, drive, and incentive, and no strong communities of practice exist to promote engagement. Both the imagined and practiced communities for these students come with a lack of pressure; activities such as watching Netflix, browsing YouTube, and sleeping are prevalent. This alignment between the imagined and practiced communities affords students a consistent identity and position. However, mainland students encounter a disparity: their imagined community is one of university life, whereas their practiced community resembles a primary-school environment. This discrepancy can easily lead to an identity crisis. I therefore propose a novel conceptualisation of metacognition in language teaching and learning. Metacognition in language learning is partly based on seeking awareness as an agent of one’s language learning, during which identity, position, and self-reflection are being promoted to enhance learning outcomes.

When I struggle to derive inspiration from teaching, I seek solace in research. However, the community in Macao does not seem to be research-oriented either. My imagined community would ideally offer ample feedback and support for conducting research. The reality is, for me, sadly different. Many of my colleagues show little interest in research and prefer instead to remain comfortable, as evidenced by comments like ‘I only like my comfort zone’, ‘Please help us publish everything so we can rest more’, ‘Don’t send me any academic posts – too much pressure’, and ‘Can I lay down like this for the rest of my life?’ Given this atmosphere, I have been compelled to seek alternative communities of practice. For instance, connecting with friends and work partners at the Kansai Methodology Research Forum grants me the intellectual stimulation I seek; there, I can converse with others who are genuinely committed to research and academic progress. Thus, in my eyes, metacognition in research involves an awareness that positions the researcher as a seeker of knowledge. This sense extends beyond one’s immediate surroundings. Interfacing with a broader academic community can enhance scholarship and personal growth.

2.4 Critical Issues

Several critical issues still stand to be explored upon perusing the literature on metacognition.

2.4.1 Metacognition and Age

The study of metacognition and its relationship to age has evolved over time. Early work in the 1970s mostly covered children’s metamemory and their understanding of person, task, and strategy variables. Scholars investigating theory of mind subsequently delved into children’s initial metacognitive knowledge, specifically the awareness of mental states such as desires and intentions. This exploration widened the scope of research to task-related cognitive processes meant to improve performance and track progress. Metacognition has been described as ‘knowledge about knowledge’, ‘thoughts about thoughts”, or “reflections about actions’, all of which typify its self-reflective nature (Weinert, Reference Weinert, Weinert and Kluwe1987, p. 8). Flavell (Reference Flavell1979) pointed out the interconnectedness between the three facets of metacognition, where metacognitive knowledge informs the selection and use of metacognitive skills for specific people and cognitive tasks.

Researchers have aimed to understand the critical period for the establishment of metacognitive awareness. Insights suggest that metacognitive thinking may begin as soon as infancy and continue to develop throughout early childhood (Brinck & Liljenfors, Reference Brinck and Liljenfors2013). Yet the matter of whether metacognitive abilities decline with age is up for debate. Interestingly, older adults have been found to outperform younger adults on some metacognitive tasks and can adapt and acquire metacognitive skills as needed (Pennequin et al., Reference Pennequin, Sorel and Mainguy2010). These patterns raise a question: are age-induced changes in metacognition primarily developmental or learning-related? Supplemental studies could clarify this issue (Hertzog, Reference Hertzog, Dunlosky and Tauber2016).

2.4.2 Metacognition and Cognition

Metacognition, which is often mistaken for cognition, is distinct among cognitive processes. It is the scientific study of one’s thinking about their own cognition, while cognition itself delves into aspects such as memory, attention, language comprehension, reasoning, learning, problem solving, and decision making. Metacognition’s multidimensionality enables people to acquire domain-related knowledge and regulatory skills, empowering them to control cognitive processes across multiple domains (Schraw, Reference Schraw and Hartman2001). In addition to its scientific definition, metacognition can be interpreted as one’s awareness of and reflection on their knowledge, experiences, emotions, and learning in all areas. This broad understanding emphasises the introspective character of metacognition and its potential impacts on self-regulation and self-directed learning. Flavell (Reference Flavell1979) distinguished between metacognitive and cognitive activities: the former category involves learners’ planning, reflecting, monitoring, and evaluation of their learning processes; the latter focuses on acquiring information, clarifying concepts, and engaging in complex mental tasks (e.g., planning and executing activities). This differentiation underlines the active, self-reflective nature of metacognition and its roles in refining learning strategies and metacognitive regulation.

One compelling argument for the importance of metacognition lies in teachability. Educators can employ numerous strategies to cultivate students’ metacognitive abilities. For instance, by using the ‘think-aloud’ method, instructors can guide students through problem solving while verbally expressing their thoughts and decision-making strategies. This technique allows learners to observe metacognitive processes in action and develop an understanding of productive problem solving. Modelling coping skills and resilience in the face of adversity is another powerful way to enhance metacognition. By demonstrating personal mistakes, perseverance, and adaptive strategies, educators provide students with insights into metacognitive regulation and the significance of metacognitive strategies. Engaging students in discussions about problem solving fosters metacognitive reflection. In being prompted to articulate their thought processes, students can better acknowledge their cognitive methods and refine those tactics accordingly. Concept mapping, reminder checklists, self-questioning, annotated drawings, and reciprocal teaching are additional ways to nurture metacognition. These techniques encourage students to actively deploy metacognitive processes, such as organising information, self-monitoring, and reflecting on personal learning strategies. However, cognition is not always easily taught.

2.4.3 Inconsistencies in Understanding Metacognition across Disciplines

Metacognition covers a range of areas that people control and monitor. Reasons for studying it vary by discipline. The field of early childhood studies stresses metacognitive activities related to managing human interaction and predicting the environmental conditions children are learning to navigate. This perspective recognises the importance of metacognition in social interaction and environmental adaptation during early development. Experimental cognitive psychology, in taking another tack, seeks to describe the information-processing antecedents underlying metacognitive feelings: researchers in this discipline strive to uncover the cognitive processes and mechanisms that give rise to metacognitive experiences and judgements (Koriat, Reference Koriat, Zelazo, Moscovich and Thompson2007). Cognitive neuropsychology assumes a different approach by investigating the brain regions involved in metacognitive processing. Through neuroscientific methods, scholars aim to identify the neural correlates and mechanisms behind metacognition (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Dolan and Frith2012). Personality psychology explores individual differences and their implications for metacognitive expression. Educational psychology emphasises metacognitive activities that facilitate effective learning and functioning in academic settings; this viewpoint strives to specify interventions that enhance learning outcomes and metacognitive regulation (Dimmitt & McCormick, Reference Dimmitt, McCormick, Harris, Graham and Urdan2012).

Metacognition also plays a crucial role in language teaching (Sato, Reference Sato, Li, Hiver and Papi2022; F. Teng, Reference Teng, Wen, Adriana, Mailce and Teng2023a; Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang, Zhang and Liontas2018). Language learners engage in metacognitive activities to monitor and regulate their language acquisition. These students are trained to be aware of their own language proficiency, set learning goals, plan study strategies, track their comprehension and production of language, and evaluate their progress. Metacognitive strategies in language learning involve reflecting on one’s language abilities, identifying areas of strength and weakness, and implementing appropriate techniques to improve one’s language skills. Relevant tactics may include self-questioning, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-regulation.

2.5 Summary

This section has discussed multiple perspectives on metacognition by transitioning from the wider field of educational psychology to the more narrow domain of language learning and teaching. I hope that this background on metacognition will inspire researchers, language teacher educators, teacher trainees, and practicing language instructors. I encourage all professionals in these roles to start or continue investigating metacognition in language learning and teaching. There is a pressing need to centre metacognition within language teacher education programmes. Experienced and prospective teachers alike should be genuinely committed to developing their own metacognitive skills and fostering metacognition in their students. However, these goals require shared knowledge among all stakeholders in language education. Only through collaboration can a robust foundation be established for metacognitive practices. By recognising the vital part that metacognition plays in language learning and teaching, educators can empower students to become more self-regulated and autonomous in their language learning journeys. Metacognition equips people with the tools to reflect on their cognitive processes, set goals, choose appropriate strategies, monitor their progress, and adjust as needed. These skills are invaluable for lifelong language learning and can greatly increase the effectiveness and efficiency of language instruction.

3 Metacognition in Reading

Significant attention has been directed towards reading, particularly in understanding how L2 readers utilise their metacognitive knowledge to extract meaning from texts. Recognising that students’ strategies represent conscious efforts to enhance their language skills and comprehension (Oxford, 1996; Rose, Reference Rose2012), it becomes evident that metacognition plays an essential role in reading. By acknowledging this, educators can identify and impart successful strategies to less proficient readers, thereby improving their reading skills. Metacognitive knowledge, such as how students apply strategies in their EFL reading development, is crucial for effective reading instruction. Importantly, societal variations in target-language exposure and literacy traditions can influence reading excellence. This section argues that contextualising learners’ metacognitive knowledge is vital for preparing them to apply this knowledge effectively, thereby enhancing their reading efficiency in real-life contexts.

3.1 Understanding the Role of Metacognition in Reading

Understanding the theoretical rationale of metacognition is fundamental to appreciating its role in reading. Metacognition involves awareness and regulation of one’s cognitive processes, which is crucial for effective reading comprehension. It enables readers to plan, monitor, and evaluate their understanding as they engage with a text. This self-awareness allows readers to adapt their strategies to better comprehend and retain information, making reading a more purposeful and dynamic process.

Pedagogical support is known to be useful for devising strategies for meaningful reading. Learners’ metacognitive knowledge about strategy use while learning to read appears critical for their reading efficiency and confidence building (Lehtonen, Reference Lehtonen2000). According to McLeod and McLaughlin (Reference McLeod and McLaughlin1986), reading is not a passive activity during which one simply extracts meaning from written text; it is instead ‘an active and interactive process where the reader uses their language knowledge to predict and construct meaning based on the text’ (p. 114). Readers who clearly perceive a reading task’s metacognitive aspects are more likely to employ diverse strategies to process the text compared with those who lack such awareness. This perspective provides a basis for grasping metacognition in reading.

If metacognition is conceived as the practice of reflecting on and regulating one’s learning, then in the reading context, it involves the student engaging in critical thinking about their own comprehension as they progress through a text. The reader becomes conscious of their cognitive experience and monitors their understanding. A core element of reading comprehension is achieving deep understanding, which goes beyond literal comprehension and factual knowledge to involve placing information in context. Individuals must connect this information to prior knowledge and then interpret, analyse, and compare it to their pre-existing understanding to potentially amend their understanding. This point also reflects the criticality of metacognition for reading. Related instruction focuses on mastering cognitive skills and developing automaticity in decoding, ultimately leading to reading fluency.

Previous work (Wen & Johnson, Reference Wen and Johnson1997) has shown that successful and unsuccessful EFL students’ learning strategies are distinct. Strategy use resides on a continuum, with variations being tied to learners’ language proficiency and skills. Strategy use ranges from ineffective to effective, and the perceived adoption of techniques may shift by task. Zhang (Reference Zhang2001) tracked EFL learners’ metacognitive awareness in reading via a semi-structured interview guide meant to elicit participants’ metacognitive knowledge of strategy use. The approach followed Flavell’s (Reference Flavell, Weinert and Kluwe1987) framework of metacognition. Participants’ metacognitive knowledge of EFL reading was classified into three groups: person, task, and strategy. The data were coded based on audio recordings from the semi-structured interviews. Findings revealed that EFL learners’ use of metacognitive reading strategies varied with proficiency levels: individuals with higher reading scores were more aware of reading strategies, whereas those with lower reading scores applied different reading strategies less proficiently. Among the evaluated techniques, comprehension monitoring was one of the most beneficial for readers. Zhang’s study provided evidence for the role of metacognition in reading comprehension. Metacognition encompasses both knowledge and regulatory skills that help control one’s cognitive processes. The results also suggest that aspects of metacognition, knowledge, and regulation are instrumental to reading; participants’ understanding of grammatical and discoursal relationships was a prerequisite for accurate text comprehension. EFL readers must possess metacognitive strategic knowledge. Recognising the importance of such knowledge can drive students to reflect on their EFL learning experiences and thus increase their metacognitive skills.

Research has consistently highlighted a robust relationship between metacognitive instruction and reading proficiency. Scholars have found that people with stronger reading skills tend to display stronger metacognitive skills. Targeted metacognitive instruction can also improve one’s reading ability. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Gu and Hu2008) focused on eighteen primary school students and shed further light on this correlation. The authors observed that learners could be guided to develop metacognitive strategies for reading comprehension. The young readers demonstrated a commendable ability to employ flexible, appropriate reading techniques. However, students’ choices were contingent on language proficiency: higher-proficiency learners at higher grade levels exhibited a wider repertoire of reading strategies. These proficient readers could activate prior knowledge, make connections with the text, identify text structures, pose questions about the content, determine contextual information, and summarise their readings. Notably, the students also reported their thoughts while reading. These findings present practical ways for teachers to help students understand main parts of the reading process. By making students aware of the requirements of learning to read, educators can empower them to self-regulate their own reading experiences. Students hence need to develop comprehension strategies that bolster their text-based understanding and prepare them to navigate reading tasks more fluidly.

The significance of metacognitive instruction in reading extends to Chinese young learners as well. Teng (Reference Teng2020a) examined how metacognitive reading strategy instruction among Hong Kong English language learners improved their reading comprehension. The study involved twenty-five fifth graders. Data were collected from the notes learners took while reading, learners’ post-reading reflection reports, teacher-facilitated group discussions, and two types of reading tests. The young students were taught a combination of strategies intended to gradually foster independent reading skills. The intervention unfolded in three stages: read and answer, reflect, and report and discuss. Participants identified twenty metacognitive knowledge factors that positively influenced their reading experiences. Furthermore, compared with students in the control group who did not receive metacognitive instruction, the intervention group attained higher scores on reading comprehension. These results provide support for the hypothesis that metacognitive knowledge enables learners to recognise when, why, and how to adapt their strategic choices. Students can then plan, monitor, and evaluate their reading processes more effectively.

Other studies, such as that by F. Teng and Zhang (Reference Teng and Zhang2021), have longitudinally investigated the role of metacognitive knowledge in reading and writing. These efforts have revealed that learners’ metacognitive knowledge (as well as their reading and writing proficiency) evolves throughout primary school. This developmental process is cumulative and features widening personal differences over time. Additionally, positive associations have been observed between one’s initial levels of metacognitive knowledge, reading proficiency, and writing performance and the subsequent growth rates of each. These results convey dynamic relationships between metacognitive knowledge, reading proficiency, and writing proficiency throughout primary school. Specifically, a direct correlation has emerged between metacognitive knowledge and reading comprehension: improvements in metacognitive knowledge correspond to improvements in reading comprehension and vice versa. Baker’s (Reference Baker and Mokhtari2017) assertion that successful reading comprehension involves building a coherent mental model of a text supports this relationship. Learners who struggle to construct such a mental model may encounter difficulties when evaluating their meaning-making process while reading – hence the reciprocal association between metacognitive knowledge and reading comprehension. F. Teng and Zhang’s (Reference Teng and Zhang2021) study is unique in that it produced tentative support for the cyclical development of metacognitive knowledge and reading comprehension. This pattern implies that as young learners’ metacognitive knowledge increases over time, their reading comprehension should increase as well. That tendency underscores the need to nurture students’ metacognitive awareness and knowledge; doing so can promote reading comprehension in the long term.

A review of literature on metacognition in reading reveals that reading comprehension is a complex process requiring students to develop an awareness of print. This understanding can be achieved by cultivating metacognitive knowledge, which enables students to monitor their understanding and engage in reflective thinking about the text. Available research suggests a causal relationship between metacognitive instruction and reading proficiency; that is, people with stronger reading skills usually possess stronger metacognitive skills. Targeted metacognitive instruction may also improve reading ability. Despite empirical evidence of this relationship, correlation does not equate to causation: research using rigorous experimental designs remains necessary to definitively link metacognitive instruction with reading proficiency. Furthermore, although scholars have described EFL learners’ varied use of metacognitive reading strategies based on language proficiency, more stands to be uncovered about these learners’ specific techniques. Insights into effective methods for teaching and cultivating metacognitive strategies would be invaluable in enhancing reading instruction for EFL learners.

A summary of information in the above-mentioned studies can be summarised in the following Table 1.

Table 1 Key understanding of metacognition in reading

| Aspect | Key understanding | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pedagogical support | Pedagogical support is essential for developing strategies that facilitate meaningful reading. It helps learners build metacognitive knowledge, which is crucial for reading efficiency and confidence. | Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2000) |

| Nature of reading | Reading is an active and interactive process where readers use their language knowledge to predict and construct meaning. Metacognitive awareness allows readers to employ diverse strategies for processing texts. | McLeod and McLaughlin (Reference McLeod and McLaughlin1986) |

| Longitudinal role of metacognition in reading | Metacognitive knowledge and reading proficiency evolve over time, showing a reciprocal relationship. Improvements in metacognitive knowledge lead to better reading comprehension. The study supports the cyclical development of these skills, emphasising the need to nurture metacognitive awareness for long-term reading comprehension improvement. | F. Teng and Zhang (Reference Teng and Zhang2021) |

| Strategy use and proficiency | Successful and unsuccessful EFL students use distinct strategies. Strategy use varies with language proficiency and task requirements. Higher proficiency learners are more aware of and use reading strategies more effectively. | Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Gu and Hu2008) |

| Classification of EFL learners’ metacognitive knowledge | Classification of EFL learners’ metacognitive knowledge into person, task, and strategy categories. Higher reading scores correlated with greater awareness of reading strategies, particularly comprehension monitoring. Metacognition encompasses knowledge and regulatory skills essential for reading comprehension. | Zhang (Reference Zhang2001) |

| Metacognition and reading proficiency | Metacognitive instruction improved reading comprehension in Hong Kong fifth graders. The study involved stages of reading, reflection, and discussion, leading to higher comprehension scores compared to a control group. Metacognitive knowledge helps learners adapt strategies effectively. | F. Teng (Reference Teng2020a) |

3.2 Critical Issues

3.2.1 How Can Metacognitive Instruction Facilitate Reading?

Metacognition plays a key part in reading and prompts particular questions: How do students’ monitoring and regulation processes influence their reading outcomes? More importantly, how can instruction support these reading processes? A major aspect of this field entails understanding who performs monitoring and regulation, when these processes occur, the environmental factors that stimulate them, and how they correlate to reading performance. Given the educational potential of metacognition, many studies have explored interventions designed to enhance reading skills – especially these treatments’ impacts on students’ reading abilities (e.g., Urban et al., Reference Urban, Urban and Nietfeld2023).

Metacognitive instruction, which can be broadly defined as pedagogical approaches aimed at improving domain-general, higher-order thinking processes in reading, seeks to develop in students self-regulatory strategies that foster engaged, strategic, and metacognitive comprehension. Yet teachers often face challenges to the scaffolded incorporation of reading strategies into daily classroom instruction. Planning is a critical stage preceding reading: strategic readers establish goals (e.g., remembering or comprehension), scan the text to gather information about it, activate prior knowledge, choose suitable strategies, allocate sufficient resources (e.g., reading time), and predict outcomes (Pressley & Gaskins, Reference Pressley and Gaskins2006). However, teachers in classroom settings are often ill equipped to impart such strategies to students. The goal of strategy instruction is to gradually transfer responsibility for selecting, applying, monitoring, and evaluating strategy use from teachers to students. Classroom teachers’ under-preparedness to fulfil this objective hampers metacognitive strategy implementation and undermines students’ potential to become independent, proficient readers.

3.2.2 When to Facilitate Metacognitive Instruction for Reading?

Metacognitive knowledge heavily contributes to the longitudinal development of young learners’ reading and writing skills (F. Teng & Zhang, Reference Teng and Zhang2021). While children rely on rehearsal strategies in the early stages of reading, by fourth grade, they become more capable of actively managing their reading and adopting complex cognitive strategies if given strategy instruction (Baker, Reference Baker, Israel, Block, Bauserman and Kinnucan-Welsch2015). F. Teng (Reference Teng2020a) lent support to these findings, documenting that young learners move from an initial reliance on reading and completing exercises to being aware of a wider repertoire of factors influencing their reading. F. Teng (Reference Teng2020a) particularly focused on fifth-grade learners in Hong Kong.

An important consideration in metacognitive instruction for reading is the age at which it should be introduced and how it should be implemented. Metacognitive accuracy may vary with age: younger adults tend to have higher metacognitive accuracy in assessing their cognitive capacity, whereas older adults excel in evaluating their ability to selectively remember information (Urban et al., Reference Urban, Urban and Nietfeld2023). This discrepancy suggests there may be separate metacognitive mechanisms which aging differentially affects.

Some people need to devote more cognitive effort to specific tasks as they age, and their cognitive resources may deplete more quickly while doing so. Older adults might then become more discerning when choosing tasks that warrant cognitive resources; this deliberation can be seen as an adaptive response to the reduced cognitive resources available for reading. To explore age-related differences in metacognitive processes, it is advisable to gather evidence on reading strategies’ efficacy among young and adult EFL learners by examining the techniques that these groups employ. Creative methods (e.g., reading and writing workshops, reflections, group discussions, and metacognitive strategy instruction) can also be compared.

3.2.3 How to Facilitate Metacognitive Instruction for Reading?

Another crucial aspect is how to facilitate metacognitive instruction for reading. Several factors need to be addressed, including the training sequencing and duration, task selection for teaching and training, instructional delivery (e.g., chosen models), and applicable transfer tasks and assessments (Azevedo, Reference Azevedo2020). The sequencing of training refers to the order in which metacognitive knowledge and skills for reading are taught. A sequence may begin with declarative knowledge (i.e., about strategies and processes), followed by procedural knowledge (i.e., about how to use strategies) and then conditional knowledge (i.e., about when and why to use them). This structure allows learners to develop a solid foundation of metacognitive awareness in reading. The length of training regimens is another consideration. Declarative knowledge typically develops more quickly than procedural or conditional knowledge; therefore, the time required to master each form of knowledge may vary.