This article offers a critical review of social protection research in Latin America. The region has pioneered institutional developments in social protection, including occupational insurance funds in the post-Second-World-War period, personal pensions in the last quarter of the last century and conditional income transfers in the 2000s. They are the main institutions in the social protection matrix in the countries in the region. Despite pioneering innovations, social protection shows large and persistent gaps as well as inequalities in access and provision. This article reviews the substantive body of research addressing this anomaly through an analysis of the design, evolution and outcomes associated with these institutions.

Social policy covers transfers in kind or services and income transfers or social protection. The discussion below will focus on social protection exclusively. This approach needs justification. Services, education and healthcare especially, are supremely important for economic and social development. However, they show a different dynamic to that of social protection, at least for Latin America. Comparative studies of education provision on a global scale indicate strong convergence, at least in terms of access though less so in terms of quality (Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Pagés, Szekely and Acevedo2024; Lee and Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2016). There is no evidence of similar global convergence in social protection.Footnote 1 Studies on social spending in Latin American countries generally find that trends applying to services are distinct from those applying to income transfers, leading them to suggest there are structural differences in their underlying politics (Avelino et al., Reference Avelino, Brown and Hunter2005; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Mustillo and Stephens2008; Kaufman and Segura-Ubiergo, Reference Kaufman and Segura-Ubiergo2001; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2015). Focussing on social protection alone is a limitation of this review, but this approach will offer a more revealing perspective on what is distinctive to the evolution of social policy in Latin America.Footnote 2

The article adopts a ‘ground up’ approach with a focus on endogenous explanations of the evolution and distinctive character of social protection in Latin America. Welfare state theory, the theory of social protection institutions in European early industrialisers,Footnote 3 has exerted a dominant influence on the study of social protection elsewhere. It offers a body of advanced conceptualisation and research tools of great value to researchers. However, in a global context, welfare states constitute a special case of social protection development.Footnote 4 The fact that European welfare states present an advanced form of social protection with impressive outcomes (Kammer et al., Reference Kammer, Niehues and Peichl2012) does not entail that Latin American countries are in transit to this destination. This article avoids the pitfalls of a linear development approach. The social protection institutions in Latin America are considered in their distinct evolution and as a response to domestic political realignments.

Research on social protection in Latin America has much to contribute to our understanding of the remarkable growth and innovation in social protection provision in low- and middle-income countries in the twenty-first century. It draws attention to the need for a ‘general’ theory of welfare institutions capable of explaining trends globally. The research reviewed in this article offers valuable pointers for constructing a ‘general’ theory.

The article organises the materials in five main sections and a conclusion. Section 1 takes stock of the social protection matrix in Latin America, offering a concise overview of the core social protection institutions and their reach. Section 2 discusses explanations of the source and evolution of social protection institutions in terms of domestic political realignments. The core institutions – occupational pensions, personal pensions and social assistance – emerged with the political realignments associated with industrialisation, neoliberalism and democratisation, respectively. Section 3 discusses outcomes of social protection institutions by focussing on their stratification effects. Section 4 focusses on the aggregate distributional effects of social protection, which are best assessed when considering taxes and transfers combined. Research for Latin America shows that taxes and transfers have disappointing effects on poverty and inequality. Section 5 identifies some pointers for a ‘general’ theory of welfare institutions arising from the discussion of social protection in Latin America. A final section concludes.

Taking stock of the social protection matrix

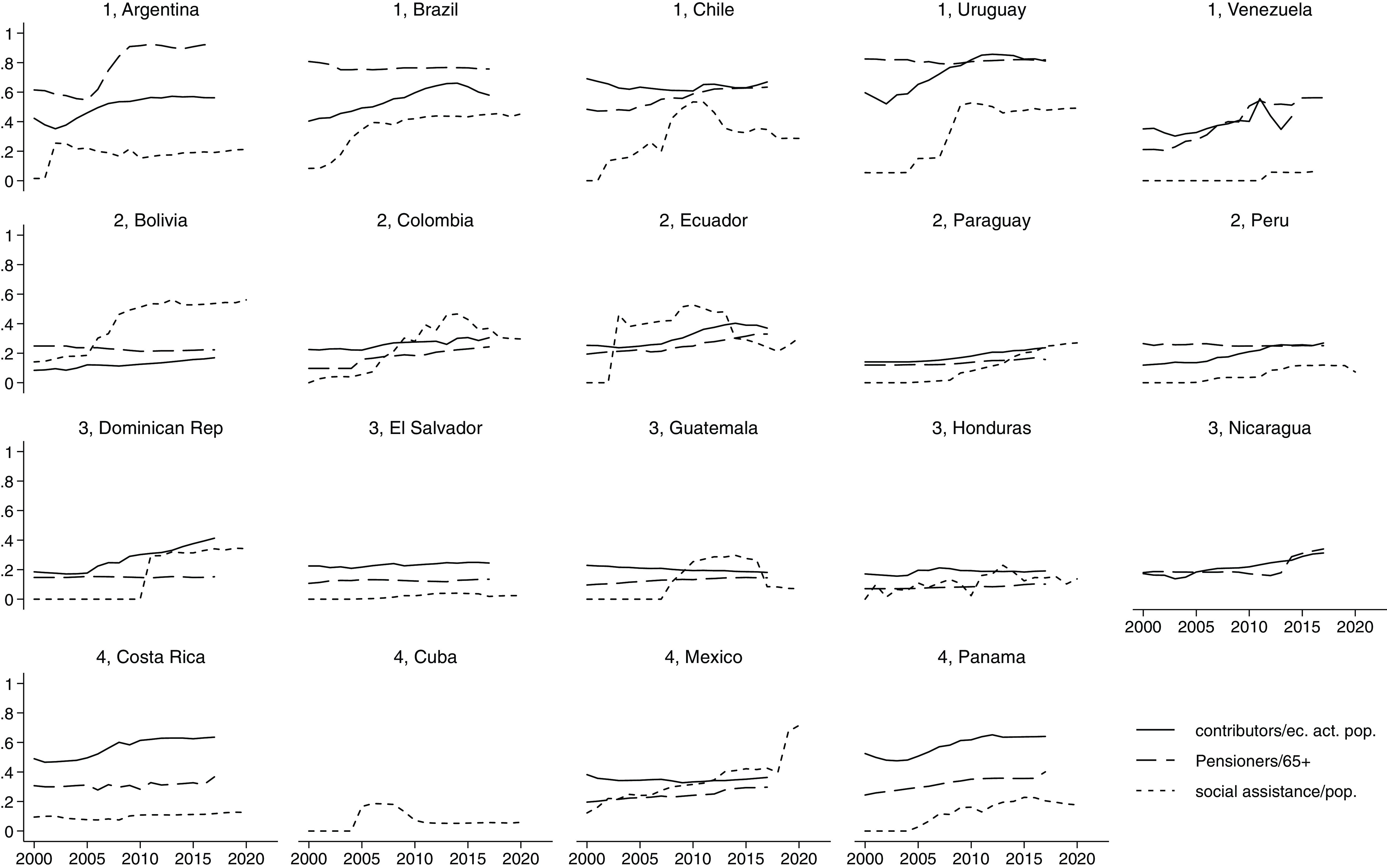

It is helpful to begin with a succinct overview of the social protection matrix in Latin America. Three main types of social protection institutions are at the core of social protection in the region: occupational insurance, personal pensions and social assistance.Footnote 5 Social assistance consists mainly of family transfers/conditional income transfers and old age transfers. Figure 1 shows their reach at a country level for the period 2000–2020.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Reach of social protection institutions in Latin America. The solid line shows active contributors to pension schemes as a share of the economically active population. The broken line shows pensioners as a share of the population aged 65 and older. The dotted line shows the share of the population in households receiving social assistance transfers. Numbers preceding countries indicate clusters: 1 Industrial; 2 Andean/extractive; 3 Central America/agro-exporting; 4 Unclassified. Sources: Contributors and Pensioners (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019); Social Assistance (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2018).

The share of the economically active population contributing to an occupational insurance fund or a personal pension is commonly used as a top-level indicator of the reach of social protection. It defines ‘formal’ or protected employment, with the remainder referred to as ‘informal’ or unprotected employment. In Latin America, around one-half of the labour force contribute to some form of pension provision (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2024; CAF, 2020; UNDP, 2021). However, this is an unreliable indicator of protection due to employment volatility and pension vesting rules. As a rough estimate, just around one-half of current contributors will access a pension benefit at retirement; the other half will miss out due to insufficient contributions (Altamirano Montoya et al., Reference Altamirano Montoya, Berstein, Bosch and García Huitrón2018; Apella and Zunino, Reference Apella and Zunino2023; de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Castiñeiras, Ardente, Montti, Zelko and Araya2019; Gualavisi and Oliveri, Reference Gualavisi and Oliveri2016). The associated arithmetic is straightforward. For the region taken as a whole, two in every four workers contribute to a pension fund, but only one in every two contributing workers will manage to access retirement benefits. The share of people aged 65 and older who are in receipt of a pension benefit is a more accurate indicator of the reach of occupational insurance or retirement savings plans (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019; Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Melguizo and Pages2013). The reach of social assistance is measured by the share of the population living in recipient households, as transfers are shared within them. Social assistance shows a remarkable expansion in the twenty-first century (Cecchini and Atuesta, Reference Cecchini and Atuesta2017).

In Figure 1, countries are arranged to highlight potential clusters.Footnote 7 The first row includes countries that experienced earlier and deeper industrialisation: Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Uruguay and Venezuela. Relatively high levels of pension receipt reflect a more extensive reach of their occupational insurance and personal pensions. The next row includes Andean countries with more limited share of active contributors in the labour force as well as a more limited share of pension recipients. This is explained by the extractive nature of their economies and their limited industrialisation. The third row includes Central American countries with low share of pension contributors and even lower shares of pension recipients. Their limited social protection provision is a consequence of their agro-export economic model. The last row includes countries harder to classify. Mexico experienced early industrialisation with the countries in the first group, but the reach of social protection institutions is significantly lower. Costa Rica and Panama have relatively high shares of pension contributors in the labour force, similar to the more industrialised countries in the first row. However, their share of pension recipients is closer to some of the Andean countries. Cuba’s socialist economy, with a dominant public sector, should have high contribution rates and high pension receipt rates, but data are scarce. The reach of social assistance has risen in all countries, except Nicaragua.

The discussion in the article will disregard supplementary programmes covering employment risks such as unemployment, maternity, sickness and work-related injuries. Supplementary programmes are not in place everywhere, are limited in scope and require participation in occupational insurance or personal pensions. Countries in the region have traditionally relied on severance pay regulation to protect jobs. The spread of personal pensions in the 1990s provided a model and infrastructure for the implementation of savings-based unemployment insurance (Ferrer and Riddell, Reference Ferrer and Riddell2011). Sehnbruch et al. (Reference Sehnbruch, Carranza and Contreras2020) studied Chile’s unemployment insurance programme and found that only 11.8 per cent of workers with open ended contracts were entitled to make a claim. Family policies, including maternity provision, are also highly selective and stratified (Rossel, Reference Rossel2013). Active labour market policies are at best embryonic (Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Kluve, López Mourelo and Pignatti2019). Focussing on the core institutions will provide an adequate perspective on the structure of social protection in the region.

Political realignments and the evolution of core institutions

What explains the emergence and evolution of social protection institutions in Latin America? Research suggests that the core institutions are associated with significant political realignments.Footnote 8 This section considers the linkages between social protection institutions and political realignments.

The growth of occupational insurance funds in Latin America in pioneer countries is explained by industrialisation. The first wave of industrialisation at the onset of the twentieth century did not lead to large-scale social protection institutions. Oligarchic political regimes excluded most of the population from political influence whilst an incipient urban labour movement was infused by socialist and anarchist ideas. Oligarchic rulers sought to manage emerging labour organisation and left parties by repression. These conditions encouraged self-protection through mutual aid and professional associations (Illanes, Reference Illanes2003).

The Great Crash and two world wars curtailed global demand for Latin American exports and encouraged measures to substitute imports. Import substitution policy responses cohered into a state-led-developmental model (Bértola and Ocampo, Reference Bértola and Ocampo2012).Footnote 9 Political support for these policies came from industrial interests and urban workers, leading to their political incorporation (Collier and Collier, Reference Collier and Collier1991; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago1978). Government recognition and support for occupational insurance funds accompanied top-down incorporation of selected groups of workers (Carnes, Reference Carnes2009; Malloy, Reference Malloy1979), commonly referred to as the ‘first incorporation’. This explains the selective and fragmented features of the funds and the exclusion of large segments of the labour force, agricultural workers and own-account workers in particular (Haggard and Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008).Footnote 10 In Andean countries, extractive economies further reduced the scope for occupational insurance. In Central American countries, the absence of industrialisation explains the absence of social protection institutions (Sánchez-Ancochea and Martínez Franzoni, Reference Sánchez-Ancochea and Martínez Franzoni2015; Segovia, Reference Segovia2022). Industrialisation patterns explain social protection inequalities within and between countries in the region.

The share of the labour force participating in occupational insurance funds peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the early industrialising countries (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago1978). The exhaustion of the state-led development model, punctuated by recurrent financial and fiscal crises, gave way to economic liberalisation and structural adjustment policies geared to an export-led economic model. Trade and labour market liberalisation lifted measures protecting hitherto favoured sectors of the economy and their workers.

Social protection reforms played an oversized role in structural adjustment policies. Replacing occupational insurance with personal pensions became the point of the spear (James, Reference James1996). Reform advocates argued that redistributive features within occupational insurance were responsible for introducing a wedge between workers contributions and their benefits, with deleterious effects on work incentives. Shifting the basis of protection entitlement to individual savings was intended to remove these disincentives, promote competition and enhance incentives in the labour market. The World Bank was a strong advocate of individual retirement plans (Gill et al., Reference Gill, Packard and Yermo2004). Transferring workers’ retirement savings to financial providers offered the additional benefit of strengthening financial markets whilst at the same time excluding labour organisation from any influence on social policy.

Resistance to the reforms was limited in countries where labour organisations and left parties had been weakened by authoritarian rule. The suspension of democratic institutions facilitated more radical reforms, as in Chile. In countries with democratic institutions in place, reforms were gradual and more tentative (Kay, Reference Kay1999; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2020; Mesa-Lago and Müller, Reference Mesa-Lago and Müller2002). As personal pensions have matured, opposition to them has strengthened. Chile, the exemplar of pension reform and the only country where a plurality of dependent workers contributes to a personal pension, has made repeated attempts to reform personal pensions. Opposition to reforming personal pensions has been orchestrated by private pension managers (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2002; Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019; Castiglioni, Reference Castiglioni2005; Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2021).

Neo-institutional theories of welfare state development stress the role of support constituencies and feedback mechanisms in sustaining institutional persistence (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1990; Bruch et al., Reference Bruch, Ferree and Soss2012; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993; Pierson, Reference Pierson2001). By contrast, social protection institutions in Latin America are subject to permanent change. Occupational insurance funds show considerable change since their inception in terms of their governance, financing, organisation and provision. Their stratification and limited reach are a significant source of weakness (Berens, Reference Berens2015; Holland, Reference Holland2018; Solís et al., Reference Solís, Chávez Molina and Cobos2019).

The return to democracy in the 1980s and 1990s and the ascendancy of left coalitions to power focussed attention on the groups excluded from social protection institutions (Feierherd et al., Reference Feierherd, Larroulet, Long and Lustig2023). Traditional political parties and labour organisations emerged from the neoliberal phase significantly weakened (Lupu, Reference Lupu2017; Pop-Eleches, Reference Pop-Eleches, Kapiszewski, Levitsky and Yashar2021; Roberts, Reference Roberts, Silva and Rossi2018; Niedzwiecki and Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2025), in contrast to social movements and civil society organisations, which emerged strengthened from the struggle against neoliberal policies (Kapiszewski et al., Reference Kapiszewski, Levitsky and Yashar2021; Silva and Rossi, Reference Silva and Rossi2017). Addressing the social consequences of structural adjustment gave salience and urgency to poverty reduction.

Left parties and labour organisations in Latin America traditionally favoured occupational insurance as the social protection institutions of choice. Yet, conditional income transfer programmes spread through the region.Footnote 11 Borges (Reference Borges2023) remarks that expanding social assistance was something left parties learned to do when in power.Footnote 12 In Brazil, programmes providing transfers to vulnerable families supporting children’s schooling emerged at the subnational level from the early 1990s (Rocha, Reference Rocha2013). Federal government scaled them up through Bolsa Escola in 2001. President Lula, elected in 2003 with a commitment to ‘Zero Hunger’, a multifaceted set of interventions, was eventually persuaded to focus on consolidating and scaling up conditional transfer programmes with the establishment of Bolsa Família in 2006 (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2013; Borges, Reference Borges2023). Mexico’s PROGRESA was designed as a rules-based family transfer programme addressing the social effects of agricultural liberalisation in Mexico, underlined by the Zapatista rebellion. Levy (Reference Levy2006) notes that its design was guided by the need to avoid clientelism, which had undermined earlier poverty programmes, and the need to combine income transfers with schooling and health. The expansion of social assistance reflects both a new political realignment and new thinking on poverty reduction.

A strand of political analysis of social assistance in Latin America has approached the new institutions as primarily electoral interventions. Past poverty reduction programmes had marked clientelisitic features (Díaz-Cayeros et al., Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). Ex-post analysis of attitudinal survey data shows an incumbent support effect associated with transfer recipients (Araújo, Reference Araújo2021; Baez et al., Reference Baez, Camacho, Conover and Zárate2012; De la O, Reference De la O2013; Díaz-Cayeros et al., Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Zucco, Reference Zucco2013; Zucco and Power, Reference Zucco and Power2013). There are critical issues with this approach. Key features of conditional income transfers contradict the electoral intervention explanation. Clientelistic rulers are likely to avoid regular, rules-based, household income transfers, with social investment objectives delivering results in the medium and longer term (Díaz-Cayeros et al., Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Stokes, Reference Stokes2004). Alternative explanations for the incumbent effect appear credible, that is, as a response to inclusive social protection policies from pro-poor coalitions (Hunter and Borges Sugiyama, Reference Hunter and Borges Sugiyama2014; Layton et al., Reference Layton, Donaghy and Rennó2017).

A strand of research hypothesises that the expansion of social assistance in the region involves a ‘second’ incorporation (Silva and Rossi, Reference Silva and Rossi2017). The expansion of social assistance reflected efforts to include hitherto excluded groups with ramifications for the political incorporation of these groups (Hunter and Borges Sugiyama, Reference Hunter and Borges Sugiyama2014). Conditional income transfers and old age transfers facilitated policy linkages to social movements and excluded groups, the ‘outsiders’ (Garay, Reference Garay2016; Garay, Reference Garay, Kapiszewski, Levitsky and Yashar2021; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2018; Niedzwiecki and Anria, Reference Niedzwiecki and Anria2019). Analysis of conditional income transfer evaluation data finds increased engagement in political activity amongst social assistance recipients in Colombia and Mexico (Baez et al., Reference Baez, Camacho, Conover and Zárate2012; De la O, Reference De la O2015). Analysis of attitudinal survey data finds that transfer recipients show stronger support for the political system than the average respondent in the population (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos, Kuhlmann and Nullmeier2022; Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2023; Schober, Reference Schober2019). Social protection inclusion encourages political inclusion.

In sum, the pattern and evolution of social protection institutions reflect significant political realignments: the emergence of an urban working class; neoliberal retrenchment; and a focus on inclusion with democratisation and the left turn.

Stratification outcomes

What are the main outcomes of the social protection matrix in Latin America? This section reviews the social stratification effects of social protection institutions. Social protection institutions support distinct groups of workers. Occupational insurance and personal pensions support better-paid workers in large firms and their families. Social assistance transfers support lower-paid workers and their families. The social protection matrix reinforces social stratification.

There is considerable diversity in occupational pension rules across schemes and countries (OECD/IDB/The World Bank, 2014), but three features are key to understanding provision in the region: replacement rates; vesting periods; and minimum pensions. Retirement benefit formulas include years of contribution and a measure of final salary. Pension rules favour workers with high density of contributions and penalise less advantaged workers with short and/or fragmented working lives (Altamirano Montoya et al., Reference Altamirano Montoya, Berstein, Bosch and García Huitrón2018). Vesting periods define minimum years of contributions to access retirement benefits, usually between 20 and 30 years (OECD/IDB/The World Bank, 2014). Minimum retirement benefits set a floor for workers meeting their vesting period. Latin American countries suffer from high employment turnover and informality (Gualavisi and Oliveri, Reference Gualavisi and Oliveri2016), with direct implications for the effectiveness of pension schemes. With variation across countries, occupational insurance in Latin America supports dependent workers in large workplaces who enjoy long tenure and rising salaries. For disadvantaged workers, participating in an occupational pension scheme is a risky bet on a minimum pension.

The implementation of neoliberal policies in the 1980s prioritised the liberalisation of labour markets and the economy. Structural and parametric reforms of occupational insurance reduced labour costs, liberalised employment practices and restricted the influence of labour organisations. (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos1998). Parametric reforms reduced the scope and generosity of occupational pensions (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019; IMF, 2018). Structural reforms introduced personal pensions as a substitute for occupational insurance funds.Footnote 13 The reforms mandated workers to save a fraction of their earnings in privately managed financial pension managers. On reaching retirement age, workers use the balance of their accounts to make pension arrangements. The original scheme intentionally excluded any redistributive, or indeed insurance, features.

Eleven countries in the region eventually implemented structural reforms (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2020). They included, in chronological order, Chile (1981), Peru (1993), Argentina and Colombia (1994), Uruguay (1996), Bolivia and Mexico (1997), El Salvador (1998), Costa Rica (2001), the Dominican Republic (2003) and Panama (2008). Retirement income provision in these countries is best described as in transition, with some modalities promoting a sharp transition as in Chile, and the rest envisaging a protracted period in which occupational insurance and individual retirement savings schemes coexist. Costa Rica and Uruguay introduced personal pensions as a complement to occupational pensions.

Personal pensions have not generated the outcomes claimed by their advocates. They were expected to reduce fiscal deficits, liberalise employment practices and boost financial markets and growth (Holzmann, Reference Holzmann1996; Holzmann and Hinz, Reference Holzmann and Hinz2004). These claims were contested at the time (Orszag and Stiglitz, Reference Orszag and Stiglitz1999). Participation in personal pensions is significant only in Chile, at around 65 per cent of the labour force (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019). The 2008 global financial crisis and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) demonstrated the vulnerabilities of protection instruments dependent on individual savings. The global financial crisis reduced balances substantially, and unexpectedly. COVID-19 encouraged demands from savers to access their funds, further reducing balances in retirement accounts (Kay and Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022). Growing demands for public support have persuaded governments in the region to reverse structural reforms and to expand old age transfers (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2020).Footnote 14 Argentina transitioned back to occupational insurance in 2008.

At the turn of the new millennium, Latin American countries introduced large-scale rules-based conditional income transfers and expanded old age transfers. This has been explained by a return to democracy in the 1990s, a ‘pink tide’ of left and centre-left governing coalitions and an unexpected rise in resource revenues from the commodity boom. They are underpinned by a new commitment to poverty reduction as state policy.Footnote 15 By 2015, social assistance transfers reached a third of the population in the region (Cecchini and Atuesta, Reference Cecchini and Atuesta2017; Cecchini and Martínez, Reference Cecchini and Martínez2011).

Conditional income transfers are the main innovation. They provide transfers to households facing poverty and vulnerability, supplementing household income for a guaranteed period, with the condition that household members access primary healthcare and children attend school. Transfers support improvements in consumption and facilitate human capital investment. Mexico’s PROGRESA and Brazil’s Bolsa Família pioneered this approach in the mid-1990s, and it was subsequently adopted by all other countries in the region except Nicaragua (Borges, Reference Borges2023; Borges Sugiyama, Reference Borges Sugiyama2011; Levy, Reference Levy2006). Old age and disability transfers have also expanded in three main modalities: transfers offered to all over a certain age as in Bolivia; transfers paid to older people without formal pensions as in Chile; or transfers paid to older people in poverty as in Guatemala (Rofman et al., Reference Rofman, Apella and Vezza2015). Old age transfers support basic minimum income security in later age (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2021).

A feature of social assistance transfers in Latin America is that they are decoupled from employment. Conditional transfer recipients are expected to work, as transfers are only around 20 per cent of household income. Rates of labour force participation amongst recipients are on average higher than for the adult population (Barrientos and Malerba, Reference Barrientos and Malerba2020). Old age transfer recipients are not required to exit employment. In practice, old age transfer recipients show some reduction in paid labour, but this is not a requirement of receipt (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Melguizo and Pages2013; Bosch and Guajardo, Reference Bosch and Guajardo2012; Bosch and Manacorda, Reference Bosch and Manacorda2012).

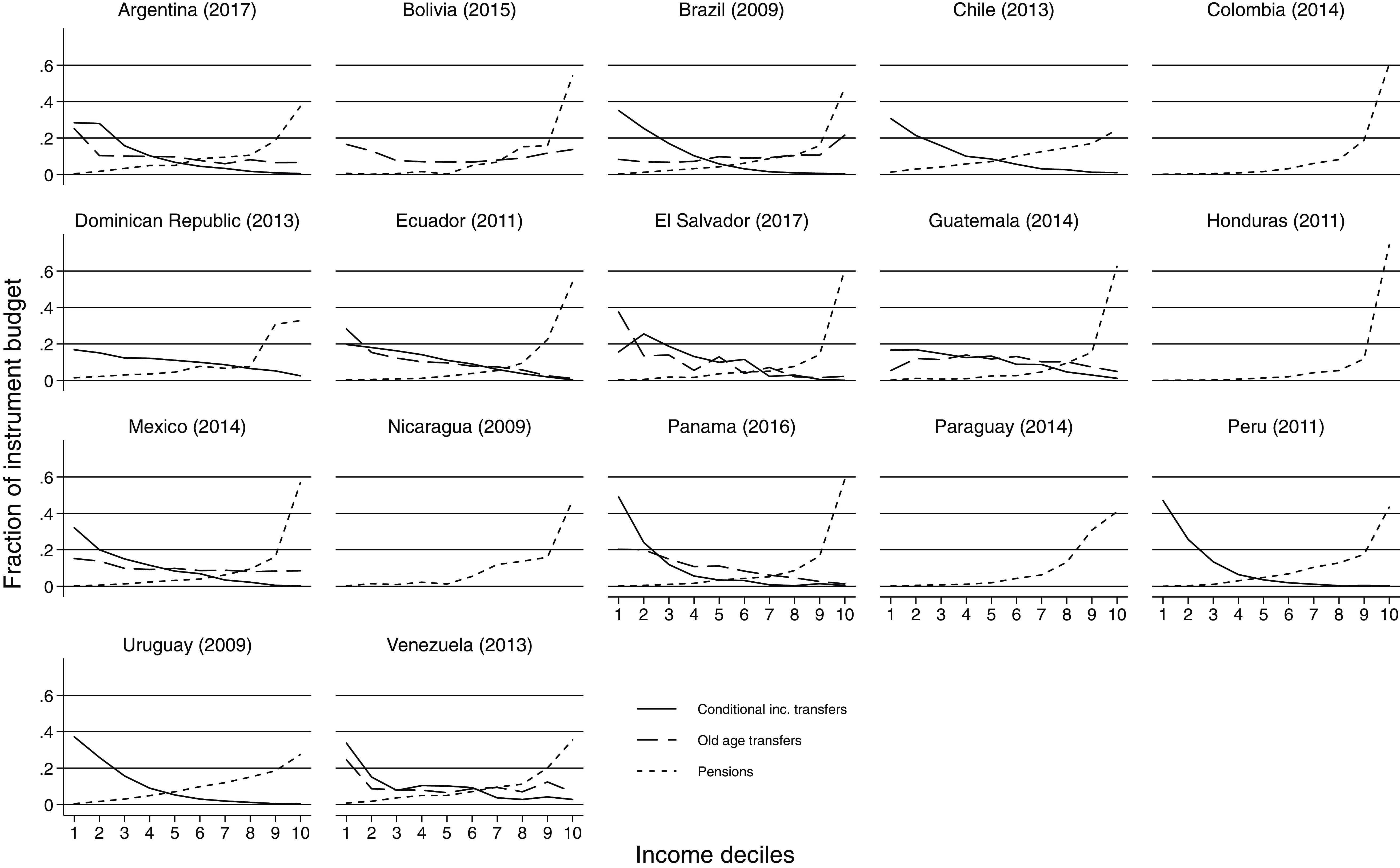

These core institutions, and their modalities, stratify workers and populations in the region (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2024). Figure 2 shows the distribution of transfer instrument budgets across income deciles. Social assistance transfers, conditional income transfers and old age transfers support lower-income households, as expected. Pension benefits, from occupational insurance and personal pensions, are captured by higher income groups. Note that Figure 2 shows the distribution of the transfer instrument budgets. Pension budgets are several times greater than social assistance budgets.

Figure 2. Distribution of transfer instrument budgets across income deciles. The solid line shows the distribution of conditional income transfer income across deciles of household income. The broken line shows the distribution of old age transfer income across deciles of household income. The dotted line shows the distribution of pension income across deciles of household income. Source: Commitment to Equity (CEQ) Standard Indicators v. 4.0 (2022) https://commitmentoequity.org/datacenter/. The source data combine household survey responses and aggregate economy data. Where household surveys did not identify transfers, data are missing, hence Costa Rica is not included. Nicaragua does not have social assistance transfers.

It is not surprising that the institutional matrix results in large inequalities in protection (Arza et al., Reference Arza, Castiglioni, Martínez Franzoni, Niedzwiecki, Pribble and Sánchez-Ancochea2022). Social protection in Latin America and its outcomes are structurally gendered.Footnote 16 Occupational insurance funds support skilled dependent workers in large firms and the public sector including military and police. Occupational insurance is fragmented, even where funds operate within a common governance (Bertranou et al., Reference Bertranou, Casalí and Cetràngolo2018; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2007). Personal pensions benefit mobile skilled workers in the private sector. In countries where savings plans complement occupational insurance, as in Costa Rica and Uruguay, they are restricted to high-wage workers keen on securing additional protection. Social assistance transfers support lower-skilled workers and their families.

Distributional effects of transfers and direct taxes

To what extent do social protection institutions contribute to the reduction of poverty and inequality? The distributional effects of the social protection institutional matrix are best assessed in combination with taxation. In Latin American countries, value-added tax (VAT), corporation tax and natural resource revenues are the main revenue sources (OECD/CIAT/IDB, 2023). Personal income taxes are only collected on high income units, roughly the top third. Tax collection is marginally progressive or distributionally neutral (Alvaredo et al., Reference Alvaredo, De Rosa, Flores and Morgan2022; Lustig, Reference Lustig2017). The distributional effects of the core social protection institutions move in opposite directions and tend to cancel each other out. Public subsidies to occupational insurance can be regressive. Personal pensions have few distributional effects by design. Social assistance transfers are strongly progressive but they redistribute a very small share of income, roughly less than 2 per cent of GDP. When combined, direct taxes and income transfers show limited effects on income inequality (de Rosa et al., Reference de Rosa, Flores and Morgan2022; Lustig, Reference Lustig2017; Skoufias et al., Reference Skoufias, Lindert and Shapiro2010).

Figure 3 shows the Gini index for market income and for disposable monetary income, that is, income after direct taxes and income transfers, for ten countries.Footnote 17 The good news coming from Figure 3 is the declining inequality trend shown for most countries except Costa Rica and Mexico. The bad news is that fiscal redistribution is minimal and can go in either direction. Where the Gini on disposable monetary, the broken line, is above the Gini of market income, the solid line, direct taxes and income transfers raise inequality. This outcome can be observed for Argentina and Brazil, for example. Overall, distributional effects from transfers and direct taxes are muted.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Fiscal redistribution in Latin America. The solid line shows the Gini index of market income before direct taxes and transfers. The broken line shows the Gini index of disposable monetary income, after direct taxes and transfers. Source: Alvaredo et al. (Reference Alvaredo, De Rosa, Flores and Morgan2022), https://distribuciones.info/descarga.html.

A ‘general’ theory of welfare institutions?

The review of research on social protection in Latin America in the previous sections is firmly grounded on a broadly shared approach situating welfare institutions within social, economic and political conditions. This approach is the basis of any general theory of welfare institutions. Research on the institutional matrix of social protection in Latin America suggests several pointers for the construction of a general theory. The discussion below singles them out, inviting further discussion and debate.

Researching social protection separately from services is revealing. Studying social protection offers a more direct and distinctive perspective on social policy. Basic services such as education and healthcare are, in principle, directed at the entire population. Schooling is commonly measured as the share of a particular age group in education. Social protection is instead directed at the share of the population whose livelihoods depend on employment. In Latin America, workers in non-dependent employment – including own-account, domestic and unwaged workers – make up a substantial share of the labour force.Footnote 19 The social protection institutional matrix in the region reinforces deep-seated inequalities in opportunity and welfare outcomes.

It is helpful to focus on intra-class differentiation, as opposed to inter-class differentials. Footnote 20 The distribution of income in Latin American countries has the shape of a ‘hockey stick’ resting on its long side, with income levels relatively flat through the distribution but rising fast in the top decile (de Rosa et al., Reference de Rosa, Flores and Morgan2022). There are few signs of a ‘middle class’ in countries’ income distribution. There is always a middle group in any distribution, but this is insufficient to establish the presence of a ‘middle class’ with meaningful implications for the study of social protection in the region.Footnote 21 Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2012) argue that class fragmentation is a factor explaining the absence of inclusive social protection provision in the region.Footnote 22

In a social policy context, classes play many roles, for example, as reference categories for population groups experiencing common risks and needs or having distinct preferences and interests. Sidestepping consideration of the relevance of these potential linkages in a Latin American context,Footnote 23 the suggestion implied in this article is that intra-class differentiation might offer an equivalent reference instrument for categorising population groups, perhaps with the additional advantage that it could better capture the fluidity of stratification and coalition-building resulting from the social protection institutional matrix (Solís et al., Reference Solís, Chávez Molina and Cobos2019). It makes sense to focus on those dependent on employment for their livelihoods, the object of social protection institutions, and to study the effects of social protection on them.

Social protection institutions contribute to worker stratification. In Latin America, occupational insurance funds support long-tenured workers in large firms. Their design redistributes retirement income from short-tenured workers with variable employment towards long-tenure workers (Altamirano Montoya et al., Reference Altamirano Montoya, Berstein, Bosch and García Huitrón2018; Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2024). In countries where personal pensions are mandated as the main social protection institution, they support skilled and mobile workers in dependent employment. Because personal pensions lack redistributive features, they translate wage differentials directly into retirement income differentials.

Social assistance transfers support low-income workers in dependent employment and those in non-dependent employment. Because they are guaranteed for extended periods, they help protect groups reliant on intermittent or irregular employment. Conditional income and old age transfers are not dependent on the employment status of recipient individuals and households. Research finds that participation in conditional income transfers does not adversely affect adult employment in the short term. Research on employment effects in the longer term find positive outcomes. Kugler and Rojas (Reference Kugler and Rojas2018) and Parker and Vogl (Reference Parker and Vogl2018) find that children with early participation in Mexico’s PROGRESA show higher rates of employment and earnings when adults than children who participated fewer years or did not qualify due to their age.

Social protection institutions help explain dualism in the region (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2009, Reference Barrientos2012, Reference Barrientos and Cruz-Martínez2019) as well as deeper stratification by occupation and skills within occupational insurance (Bertranou et al., Reference Bertranou, Casalí and Cetràngolo2018; Carnes and Mares, Reference Carnes and Mares2015).

Political realignments are crucial factors in the evolution of social protection institutions. In Latin America, attention to political realignments is essential to understanding the evolution of the social protection matrix. The discussion in the article focussed on three political realignments. They show considerable variation in timing and intensity at the country and subregional levels. The timing and intensity of political realignments was found to be key to understanding diverse paths across countries. A concept of political realignments is central to a general theory of social protection.

Social protection, capitalism and democracy. The evolution of social protection in Latin America has been associated with processes of political incorporation and disincorporation of workers. This has not been a linear process towards full incorporation. As an example, Argentina pioneered occupational insurance funds in the region. By the 1960s and under the populist leader Perón they had expanded to cover most of the labour force.Footnote 24 In 1994, under a Peronist government committed to neoliberal policies, personal pensions were adopted. A deep financial crisis in 2001 led to the expansion of social assistance and to efforts to include workers and pensioners left behind (the ‘moratoria’). In 2008 it reverted to occupational insurance. The current Milei administration is committed to a drastic reduction of pension deficits and a scaling back of social assistance. Since the mid-twentieth century, Argentina has experienced periods of populism, authoritarianism, democracy, and arguably, populism again. This zigzag trajectory is not unique in the region.Footnote 25

It is possible to postulate loose associations between political regimes and the emergence of social protection institutions – say, occupational insurance and populism; personal pensions and authoritarianism; and democratisation and social assistance. However, these associations are not generalisable for all countries in the region or over time. In fact, the core social protection institutions have survived in diverse configurations of political regimes in the countries in the region. The potential linkages existing between political regimes and social protection institutions need further study.Footnote 26 The discussion in the article noted the association between social protection institutions and the incorporation and disincorporation of workers, but this association does not appear to be characterised by a linear progression. Instead, it appears to be mediated by the dynamics of intra-class fractures and coalitions.

A general theory of social protection should pay close attention to causal inference methods. The implementation of quasi-experimental programme evaluations in the context of social protection institutions has improved our knowledge of the short-term effects of social assistance interventions. This is a positive development as far as it goes, but social protection institutions have broader effects on society, the economy and politics. There are considerable challenges in the application of experimental methods in the study of social protection institutions, but retaining a focus on causal inference can be hugely rewarding (Barrientos, Reference Barrientos2024). Recent improvements in data availability will facilitate the implementation of causal inference methods within a general theory of welfare institutions.

Conclusion

The article reviewed a body of research engaging with social protection institutions in Latin America and their rationale, evolution and outcomes. The social protection matrix in Latin America combines three core institutions: occupational insurance funds, personal pensions and social assistance. They emerged with political realignments associated with industrialisation, neoliberalism and democratisation, respectively. Their entitlements are underpinned by distinctive principles: membership of occupational insurance; savings capacity supporting personal pensions and other savings-based instruments; and citizenship-based solidarity supporting social assistance.

Despite considerable innovation and change, the social protection institutional matrix embeds large inequalities in access and provision for distinct groups of workers and their families. Gaps in social protection provision and institutional segmentation reinforce socio-economic stratification within countries and contribute to inequalities between countries. Social protection transfers and direct taxes have muted distributional effects.

Research on social protection in Latin America underlines the need for a general theory of welfare institutions with welfare states as a special case. Several pointers for the construction of a general theory emerge from the discussion in the article. Studying income transfers separately from services could offer a sharper perspective on what is distinctive about social policies in particular countries or regions. This approach facilitates attention to groups reliant on employment for their livelihoods. This in turn suggests an intra-class approach to fractures and coalitions. The association between social protection and political regimes is likely to be less well defined in low- and middle-income countries and further work is needed to offer useful generalisations. Finally, close attention to causal inference and political realignments will prove to be central to constructing a general theory of social protection.

Acknowledgements

I thank the editor and four reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved the paper. The remaining errors are all mine.

Competing interests

The author declares none.