6.1 Introduction

What is science, and what role should it play in the future mediation of our global society? Any discussion of the human right to science ought to begin by trying to answer those two foundational questions. As counterintuitive as it may seem in an age dominated by technology, consensus on how those questions might be answered has thus far proved elusive. More difficult still is elucidating the position of science within a framework of human rights.

It may seem strange at first to talk of science as mediation. Yet science pervades complex societal spaces in areas beyond innovation, technology, and access to their benefits. Science and culture intertwine and overlap, and contribute symbiotically to intellectual creativity and expression in complicated ways. These are best framed and analysed as mediations of complex, bidirectional relationships. This, we believe, offers more invaluable insights into the future role of science in our society.

6.2 Science As Global Knowledge and a Public Good

Several core themes must be appreciated before these questions can be addressed in the modern context, as global interconnectedness, human rights, and cultures have evolved in tandem with science and technology.

Science and culture are symbiotic. Freedom to engage in creativity is central to both and, perhaps more importantly, each informs and shapes the other in crucial ways. General Comment 25, published in April 2020, reinforces this view:

Cultural life is an “inclusive concept encompassing all manifestations of human existence.” Cultural life is therefore larger than science as it includes other aspects of human existence; it is however reasonable to include scientific activity in cultural life. Thus, the right of everyone to take part in cultural life includes the right of every person to take part in scientific progress and in decisions concerning its direction.Footnote 1

The indelible relationship between science and culture is also reflected in the intentions of the drafters of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR). There was, at the time of its drafting shortly after World War II, an intention to promote universal access to both science and culture. Lea Bishop, to whom scholarship in this area owes a great debt, has also suggested that, when the UDHR was being signed, the United Nations had come to envisage the sharing of scientific and cultural knowledge as something that could unite an international community.Footnote 2 It would be a “task in common” that would bring people together, uniting them with a common journey of discovery. This would, in turn, help “promote cross-cultural understandings” and “yield a more secure world.”Footnote 3 Understanding science as contributing to knowledge is holistic. Knowledge production is the intellectual and creative activity of engaging with the world around us, which necessitates translating the product of that activity into different forms, only one of which is what we traditionally see as science. Others include art, literature, philosophy, and the social sciences.

For this collaborative intent to truly succeed, knowledge must itself be seen as a public good, there to be shared across the world without exception.

It is not just a question of having access to what people produce, but to the whole process of creativity. It is the ability to fully explore the whole of one’s own potential in all its diverse aspects, to benefit from the creativity of others, and the protection of the moral and material interests that result – as the Covenant stipulates, those which emanate from any scientific, literary, or artistic production.

6.3 Participation in Science, Culture, and Rights Discourses

Human development is about participation, necessitating freedom to fully and actively contribute, and the right to science must also be interpreted from that perspective.Footnote 4 It cannot be just about access to the benefits, or the products, of scientific advances. Discourses about access to science are too often framed as exclusively concerning access to the end product, whether an idea or invention. Access also includes the participation of people affected by science, meaning everyone worldwide, as confirmed in General Comment 25.Footnote 5

Participation includes the freedom to experiment and fully explore one’s own creative potential, and informed engagement in the political decision-making processes concerning research prioritization. Participation in ethically significant and politically polarized areas and contexts, such as artificial intelligence and the modification of the human germline, raise several tensions and necessitate a reconceptualization of science’s role in modern society. That role cannot be understood outside a cultural context.

One way of conceptualizing the influence science has on rights is through the emerging technologies it has created, and more specifically through of the problem of meaningful consent. This allows us to understand the role science will play in global society in several linked ways. Firstly, in scientific research, consent is the ethical ground zero. This fundamental principle sheds light on two related tensions explored in this chapter. The first concerns the tensions between publicly and privately funded research. The second considers what makes consent meaningful and explores what that means beyond the research context, into the application of such research.

Facebook has conducted at least two now well-known experiments in social manipulation.Footnote 6 No consent was obtained from participants in advance. Public outrage seemed not to deter Facebook at all. The second study, published in a prestigious scientific journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), “manipulated the extent to which [689,003] people … were exposed to emotional expressions in their News Feed.”Footnote 7 Most interesting, however, was the debate between scientific professionals about the role of consent. On July 3, 2014, Inder M. Verma, the then PNAS editor-in-chief, published an “Editorial Note of Concern” responding to concerns “raised about the principles of informed consent and opportunity to opt out in connection with the research in this paper,” and defending publication.Footnote 8

A central issue in ethical discourses concerning emerging technology, and information and communication technology (ICT) in particular, regards Big Data: the collection, storage, and analyses of massive databases. The issue of consent is complex and extends beyond scientific research to use of the resulting products, for example in the Terms of Service offered to users of Internet platforms. Recent research demonstrates that reading all the agreements attached to the various applications we regularly use would take something in the order of weeks.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, we just click and go on. There is no interaction and certainly we are not informed in any meaningful way. There are few alternatives: in a recent US Supreme Court case, the view was expressed that foreclosing “access to social media altogether is to prevent the user from engaging in the legitimate exercise of [free speech] rights.”Footnote 10

The lack of genuine consent is of concern where platforms extract user data and then profile those users for marketing and manipulation.Footnote 11 They do so in a way that is opaque, not clearly understood, and unaccountable to a democratically elected body.Footnote 12 Users are simply not aware of how much data is being collected from their use of these technologies and to what use it has been or will be put. The long-term effects on the well-being of both individuals and communities is unknown to us, but is likely to be considerable. It will reshape cultures in an undemocratic way.

6.4 Data Neutrality

There are frameworks that address the way commercial entities should act in such circumstances: the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights,Footnote 13 for instance, or the Montréal Declaration on the Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence.Footnote 14 These are areas in which UN Special rapporteurs are particularly active, drafting instruments and advice for the governing of that surveillance in order to protect our rights to free speech and privacy.Footnote 15 However, governing these sprawling, global commercial entities is challenging not only because of the transnational nature of their use and influence, but also because many are US-based organizations.

There is particular emphasis in the US context on protecting free speech and the free market, sometimes at the expense of protecting individual and collective rights.Footnote 16 These technologies and their derivatives, that is, AI and Big Data algorithms, demonstrate that science is fundamentally intertwined with culture and directly impacts how culture evolves. This has significant implications for the right to science and its relationship with other rights.

From a privacy perspective, for example, seeking the deletion of such data is challenging. Europe has recently adopted a different approach to the USA under the GDPR.Footnote 17 However, there is little consensus among scholars as to whether GDPR will be effective.Footnote 18 We are faced with tools for our everyday lives that develop so rapidly that governance structures and legislative measures cannot hope to keep up. Fines imposed under regimes like GDPR are easily written off, for example as tax deductible expenses. To huge, wealthy platforms, such fines are merely another cost of doing business. This US emphasis on innovation highlights the tension between access to the benefits of science and its advancements, and intellectual property rights and innovation. There is a balance to be struck between these elements, but it must not be at the expense of other rights or natural justice.

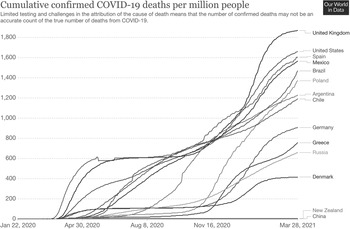

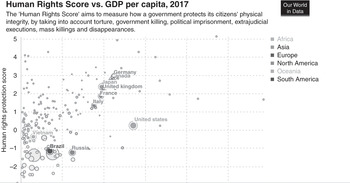

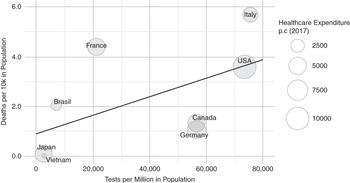

There’s a tendency to presume that data is neutral. It is not. Algorithms predict based on incomplete data in all kinds of areas, and their use will likely increase with time. There is wide consensus among scholars that this will exacerbate existing problems of discrimination.Footnote 19 This manifests in several ways. Firstly, those currently at the margins of society are also the furthest from access to such technology, exacerbating their inequality. Secondly, algorithms reflect the biases of their creators and training data: their use may further perpetuate societal biases in opaque ways. Further, exclusion leads to skewed or value-laden data.Footnote 20 For instance, if marginalized communities are excluded in some way or another from using various technologies, their data cannot be considered by the algorithms that otherwise govern them. People in authoritarian countries will experience this effect even more dramatically. Dissidents whose voices are violently silenced will have no place in this collected mega data, and it is voices like these, diverse and independent voices, whose data would reflect the true texture of the world we inhabit. Often it is in the margins where change begins, where debate and insight are catalysts for new awareness. There is, for instance, widely expressed concern regarding increased surveillance through smartphone technology as a consequence of the global emergency engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the state of that surveillance once the state of emergency has ended.Footnote 21

There is, we suggest, no such thing as neutral data just as there is no such thing as neutral research. When investigative research parameters are set out, and questions framed, there is often a way of thinking about assumptions that can combine inherent and often subconscious prejudices. Culture and ideology affects the conduct even of good science. It is worth recalling General Comment 25: the expression, “to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress” is “not restricted to the material benefits or products of scientific advancement, but includes the development of the critical mind.”Footnote 22

In 2012, during the process of researching the special rapporteur’s report for the UN on the right to science, the need of mobile phones for migrant women workers had become critical. For migrant workers to lose access to their phones – because they were taken from them by their employers – while alone and in unfamiliar parts of the world, in regions and cultures that might be alien to them, meant stripping them of access to any kind of support system. But now we see that telephones, in particular smart phones, also expose them to new kinds of risks – surveillance by private actors and by states, for different but no less potentially damaging reasons. There must always be a balance in terms of who has access to and use of such data, what it is ultimately used for, and what kind of informed consent has been obtained for those uses. Access must not be limited by income or background, and a realistic degree of privacy must always accompany access. When governments and organizations formulate policies and plans of data collection and use, we must acknowledge that it is potentially skewed in unpredictable ways and we must protect those who might be excluded or prejudiced as a consequence.

At a recent meeting on children’s rights in the digital world, as part of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s endeavor to draft a General Comment, it was noted that the young see no difference between their online and offline lives. To them, it is simply one life. The UN takes the view that all the rights enjoyed offline, in the physical world, should also be enjoyed online, in cyberspace. That, we know, is not currently the reality. How we move from simply saying it should be this way, to ensuring those rights can be enjoyed in cyberspace, is one of the core challenges facing human rights in the digital era.

This raises an interesting question. For the moment, we can set scientific knowledge to one side and simply ask, what do we mean when we say “knowledge”? We live in a world where many young people believe that the only valid source of information and knowledge is mediated by ICT. But not all information of value is to be found online. This framing raises a key question on the nature of knowledge itself: Who populates knowledge? In developed states in the Global North, it is easy to forget that not everyone worldwide has the same access to ICT. Even in the digital age, we all contribute to what we consider our vast reservoir of knowledge, but not everyone does so in the same way. What we consider to be “knowledge” is distorted by the gap between those who have access to ICT, to digital means of populating knowledge, and those who do not. This affects how we define who is able to participate in the production of knowledge. Language is another example of how the Global North biases this framing of what constitutes knowledge. It plays a substantial role in who can actually access, contribute to, and therefore participate in knowledge production. It doesn’t matter how advanced a community’s ICT technology is, if a community is unable to communicate in the right languages, very often English, it will not be able to access and participate in knowledge production, or share their own knowledge. In time, artificial intelligence may contribute solutions to this problem by offering translation affordances, but we must not allow participation in, access to, and production of knowledge to be delayed while we wait.

To take this one stage further, knowledge access, production, and participation cannot become monopolized as a consequence of information technology architecture. Regulation and governance structures to avoid the kind of monopolistic practices we are seeing with major Internet platforms and ICT companies must be explored. This inevitably involves an interdisciplinary approach, utilizing tools from other disciplines outside of international human rights law, such as antitrust and competition law. It means reconceptualizing governance structures and approaches that can react more quickly to changes in the landscape of the digital world than can international human rights law. It means, we believe, integrating the norms of international human rights law into governance and regulation structures that do not necessarily need to rely on courts to ensure compliance with States’ obligations and duties. Here again we see the inexorable convergence of science with culture, and of the right to science with cultural rights. This is the value of the initiation of the commons era of knowledge, of “open source,” where anyone can contribute and make access open to all kinds of knowledge production and participation.

6.5 The Tensions between Publicly Funded and Privately Funded Research

Part of this monopoly-based concern centers on scientific research, and research in general, in public institutions that is being increasingly driven by private sector funding. This channeling of scientific interrogation in certain directions is deeply instrumentalist. And as public funding is regularly reduced across the board, even in Europe and wealthy industrialized states, funding for pure research is decreasing.

There is a perception that research must be focused on a product, the need for something tangible at its conclusion, rather than simply the advancement of scholarship and knowledge. This is especially the case when such research is privately funded. Consequently there is little space for purely theoretical research. So much of our early scientific research, whether in the natural and physical sciences, or the social, economic, and political sciences and philosophy, focused on thinking theoretically about the world and the universe it inhabits. There was no demand for a product at the end of that process. Now, the market drives the areas into which research is able to go, and how it explores those areas. It leaves little room for serendipity and, we believe, stifles the very creativity it seeks to foster.

Scientists conducting research are concerned with negotiating patents for whatever it is that they have, before publishing and making their research available to others. The importance of these issues was highlighted in the two 2015 follow-up reports to the UN the right to science, on Patent policy and the right to science and culture,Footnote 23 and on Copyright policy and the right to science and cultureFootnote 24 and has taken on an even greater significance since. Access to the most prestigious scientific journals can be very difficult. Here, the digital age affords great potential for the sharing of knowledge, and for working with published scientific research. However, the essence of scientific work cannot be usurped by commercial incentives, or hindered by the need to copyright that work before sharing it and inviting its analysis. The core idea of science is that other researchers should be able to freely access, and thereby replicate, test and, if necessary, refute, the theories advanced. This is a process of thinking that requires onward momentum. We know that scientific hypotheses are not intended to be permanent, but should be continually tested. We must be able to communicate freely with each other to share new ideas. Intellectual property ideals cannot hinder that process. Framing the right to science in terms of cultural rights lends that notion added weight.

The other side of the public/private dynamic concerns work carried out in the public sector, but which is then transferred to the private sector. In this, we refer to public sector institutions receiving public funding for research that, on completion, leads to a product or outcome that profits the private sector.

The 2012 report to the UN on scientific progress and its applications and subsequent reports related to intellectual property lawsFootnote 25 were not received without comment, some of it strongly in opposition. The strongest opposition, unsurprisingly, came from highly developed countries and from country representatives in the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). There were expressions of genuine concern about the unrest the report had created.Footnote 26 This highlights a problem of background: the attendees at conferences and symposiums involving commercially or business oriented organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and WIPO have dramatically different perspectives to those attending similar events focused on human rights issues. Private sector companies are rarely seated at tables with human rights scholars and practitioners. The outcome of this division, which has been obvious for some time, is the perception, particularly among scientific practitioners and researchers, that the courts favor market-oriented resolutions rather than those predicated on human rights. There are rare exceptions, of course, where intellectual property rights take a back seat to human rights, both individually but also collectively. Often, however, it is only as a result of public pressure and media attention.Footnote 27

In the consultations and expert group meetings leading to the drafting of the Copyright and Patent reports, there was little in the way of engagement from the private sector. Only when the discussions concerned food-related rights was interest shown by a few private sector people engaged in the agricultural industry. It is hard to overstate the importance of such a diversity of expert opinion on an issue like food-related rights. The future of scientific research in this area is certainly dominated at present by genetically modified food chains. However, the same could be said of almost any area of emergent technology and scientific research: diversity of engagement is key.

In 2009, the then special rapporteur on the right to food identified the increasing application of intellectual property regimes to plant varieties and seeds as a significant threat to food security, particularly for the poor.Footnote 28 Intellectual property regimes focus exclusively on the commercial seed system, overlooking farmers’ informal systems. National rules frequently prohibit even small farmers and public institutions from sharing, replanting, and improving seeds covered by patents and plant varieties.Footnote 29 The “excessive protection of monopoly rights over genetic resources can stifle progress in the name of rewarding it.” Such an approach “undermines the livelihoods of small farmers, traditional and not-for-profit crop innovation systems, agro-biodiversity as a global public good and the planetary food system as a whole.”Footnote 30 The critical point to recognize is that (at least) two parallel agricultural systems exist, and should continue to exist together and in harmony: the commercial seed system and the farmers’ seeds (landraces) or informal systems.Footnote 31 This is where the biodiversity emerges from.

Farmers working for generations with particular grains, and experts working in food technology, have valuable insight to offer. Wild seeds need to be mixed in with other varieties, for example, and the result then steeped in the chaotic complexity of nature, in order to draw out higher yielding seeds. Intellectual property regimes cause tension in other ways. Some new commercial patented seeds specifically block reproduction so cannot be replanted unless farmers pay again for the technology to release the reproductive part of the seed. Yet, and perhaps ironically, GMO patented seeds could not have been developed without the very same landraces seeds they threaten. Still commercial enterprises bring legal actions against farmers who harvest plants that include their patented seeds even if it is the wind that has carried them to adjacent fields.

Similar experiences can be gleaned from the perspective of indigenous peoples and small, local communities. The Small Island Developing States, for example, particularly those in the Pacific region, who do not consider themselves “indigenous” in the way developed States have tended to label them, possess considerable traditional knowledge, but they hold it communally. In such communities, knowledge is considered a common good. There are no individualized rights of property. When we consider the concept of moral and material interests of the author, for example, they respond that they are the collective authors, and the collective holders, of that knowledge. They are also its stewards and, as such, it is passed down from generation to generation.

Clearly, intellectual property law clashes violently with this normative system because it rejects the notion that such knowledge could be owned by any one individual or corporate entity. However, where such indigenous knowledge has been retained, cultivated, and improved over many generations, and in a way that is directly influenced by and sympathetic to the particular conditions of the region, it often becomes valuable to Global North commercial entities. In a situation where such intellectual property rights are simply unknown to such communities, it is easy to appropriate that knowledge for commercial purposes without the kind of compensation or recognition that would attach to researchers from the developed world doing similar work. Such appropriation has become widespread and is known as biopiracy, or in terms that are less politically charged, bioprospecting.Footnote 32 The neem tree case,Footnote 33 which concluded a decade of litigation in 2005, provides a stark example of traditional knowledge becoming the subject of a prolonged patent battle and the tensions between different normative approaches in patent systems. It also offers a potential way forward to protect traditional knowledge. In the United States, prior knowledge or use which would deny a patent was recognized only if previously published in a printed publicationFootnote 34 – not, for example, if it had been passed down through generations of oral tradition. The European Patent Office (EPO), who had initially granted a patent to develop antifungal products to the US Department of Agriculture and multinational WR Grace in 1995, eventually agreed that the neem had actually been in use in India for a very long time.Footnote 35 Since that case, India has bought about the cancellation or withdrawal of numerous patent applications relating to traditionally known medicinal formulations. Its Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL), a database containing millions of pages of formatted information on more than two million medicinal formulations in multiple languages, “bridges the linguistic gap between traditional knowledge expressed in languages such as Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Urdu and Tamil, and those used by patent examiners of major IP offices.”Footnote 36

If unchecked, privately funded research and intellectual property law can act to encloseFootnote 37 the products of creativity and access to knowledge, whether that research arises out of traditional scientific practices or the exploitation of indigenous or traditional knowledge.Footnote 38 As General Comment 25 observes:

Local, traditional and indigenous knowledge, especially regarding nature, species (flora, fauna, seeds) and their properties, are precious and has an important role to play in the global scientific dialogue. States must take measures to protect such knowledge, through different means, including special regimes of intellectual property, and measures to secure the ownership and control of this traditional knowledge by local and traditional communities and indigenous peoples.Footnote 39

6.6 The Importance of Critical Thinking and Human Rights in Knowledge Production

This chapter began by asking what science actually is and what role it should play in mediating our global society. In its concluding paragraphs, we hope to draw the preceding threads together to begin answering those questions. What then is the added value of a human rights approach to this idea of science and its role? Equality is key. A diversity of input is essential. Decolonization of knowledge is fundamental. What science’s role in society should be cannot be answered without reference to who has control over it, who decides what is or is not “scientific” research, and how its best methodologies are determined.

We build an idea of the role science ought to play by drawing on international legal instruments such as General Comments, particularly the CESCR’s General Comment 25, and other UN documents, in particular the 2017 UNESCO Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers.Footnote 40 That idea focuses mainly on empirical science, that which can be tested and refuted, but also includes knowledge from diverse sources, including traditional knowledge. It requires that we apply to knowledge a degree of critical thinking. It requires the understanding that such knowledge may one day be proved wrong, or no longer apply, and that this, in itself, is deeply valuable. Even local communities, who have stewarded traditional knowledge from one generation to the next, may benefit from a university or similar institution doing further research. Their own knowledge is then tested and refuted or confirmed, but in either case it is built upon. Traditional knowledge may not be derived from the same rigorous principles as those that govern the practice of scientific research, but it has an important place in our reservoir of knowledge. Such communities may have explanations for phenomena that may at first seem rooted in superstition or ritual but often are based on invaluable lived experimentation. We must accept that the conceptualization of knowledge derives from different perspectives on the world – and that nevertheless each can contribute precious knowledge.

The progress of science and access to its benefits means different things to different groups, cultures, and societies. An understanding of science and what it should do, will be very different for the agricultural industry than it will be for the individual farmer, although they may share concerns about seeds and productivity. It will be more different still for younger people in the digital age, than for those of us who remember a time before information and communication technology, or before the Internet and social media.

We have highlighted the importance of participation in science, whether this relates to participation in research, or to access to the benefits of that research, be it through an end product or the furtherance of future research. But this also includes participation in decision-making about how science ought to contribute to society. Science has the capacity not just to contribute through end products and usages, but also through knowledge and education. It contributes a particular way of critical thinking which is valuable as a methodology for approaching all the vast and sometimes chaotic information we are confronted with in the digital age.Footnote 41 As the Committee puts it in General Comment 25: “doing science does not only concern scientific professionals but also includes ‘citizen science’ (ordinary people doing science) and the dissemination of scientific knowledge. State Parties should not only refrain from preventing citizen participation in scientific activities but should actively facilitate it.”

However, in the digital age, as technology progresses at an ever-accelerating pace, expertise has become even more indispensable. It is impossible for ordinary people to be even reasonably cognizant of all the technological advancements taking place at a given moment in their own society, much less be knowledgeable enough to make informed decisions about economic, political, social, and ethical considerations concerning those developments. By definition, there is a necessity, when considering what participation in science actually means, and therefore in the decision-making processes that govern how it mediates our individual and collective societies, to take into account the wide diversity of contributions that individuals in a society are capable of making. We suggest viewing participation as a continuum on which all contributions can be seen, analyzed, and made use of.Footnote 42 Public consultations can be valuable, and are made easier by ICT in the networked, digital age, but the extent to which even a well-educated public can valuably contribute to informed policy and decision-making processes is debatable.Footnote 43 Yet, to discount such participation would be undemocratic and undermine the political ideologies of most developed States.

6.7 Interdisciplinary Relationships Allow Diversity within Discourses

A further complication exists among even those who are experts in a given field: specialism. Few experts in technology fields are experts in the entirety of that field. Gone are the days when science commentators could usefully comment on the detail of a given scientific or technological discipline. An expert in particle physics may have something useful to say on the generality of artificial intelligence and the ethics of its various applications, but this is quite probably where their contribution would end. That same expert might have even less to say on the issues relating to biomedical research. So, how do we ensure the opportunity for participation from everyone in a meaningful way?

It begins with transparency, and progresses to valuable contributions through education – popular and life-long education about what emergent technologies actually involve and what the ethical debates surrounding their use really mean. Only a small cadre of experts in a given field understand its applications, but even they are not experts in how those applications might impact society in the short, medium, and long terms. It is not only human rights scholars and practitioners who express concern about those in the technology industries dictating how human rights will apply to the myriad applications of their technological innovations – many in the technology industries themselves accept they should not be making those kinds of decisions. One key example is content moderation by Internet platforms. The frameworks applied by the platforms to govern speech on their networks only approximates human rights norms, and very often, given the US-centric approach, is informed only by the First Amendment to the US Constitution, rather than by regional and international human rights instruments and jurisprudence.Footnote 44 A framework already exists, but it is not the framework platforms are using to regulate speech in the principal environment in which speech now takes place.Footnote 45 This conflict cannot continue and can only be resolved through interdisciplinary approaches that necessitate conversations and cooperation between specialists in disparate areas.

Commercial incentives driving innovation, and therefore the practice of scientific research, must not ignore fundamental human rights principles. The right to science necessarily influences and supports in a cross-cutting way the application of science and technology, and discussion of the ethics of both, to many other human rights. Experimentation in the behavioral and neurosciences, for example, where consultation and consent are in issue because a private entity conducts the research rather than one is that is publicly funded and therefore subject to different legal scrutiny, identifies a lacuna that is becoming more pervasive and dangerous. Potential harms ought to be identified and debated, and here again transparency is key. Trade secrets have, for too long, made the products of scientific research opaque and unaccountable. This problem, as we have already identified, is significant in the area of bias in algorithms. Related to this, in the criminal law context, algorithms currently assist law enforcement and courts in ways that are almost entirely opaque and therefore unknowable to the subjects of those investigations and court proceedings.Footnote 46 Independent oversight structured so as to protect trade secrets is possible, but technology innovators resist it. The balance towards commercial interests at the expense of human rights and notions of natural justice and due process has leaned too heavily the wrong way for too long. Commercial entities have greater resources and influence and have used that to unbalance the field in their favor. They are not accountable to the human rights system, nor do they sufficiently participate or engage with it.Footnote 47 In fact, they are beginning to claim false legitimacy from the language of human rights without being properly bound by its norms. This must change.

Another way in which the difficulties inherent in participation as a result of barriers imposed by specialist expertise may be addressed is through the formation of interdisciplinary groups and organizations whose debates and cooperation take advantage of diverse viewpoints and expertise. These can be both formal and informally constituted, but they must include stakeholders for a wide variety of interested, but appropriately qualified groups; from private industry as well as the public sphere. In all of the consultations and meetings preceding the Patent and Copyright reports to the UN in 2015, where anything relevant to intellectual property was to be discussed or that might conceivably have relevant implications, WIPO was present. Yet those representatives from WIPO who attended seemed to be isolated within the wider organization. While they themselves were responsive, their institution did not necessarily speak with a unified voice or a unified narrative. Private law and public law conversations must overlap, particularly those having human rights implications. Here again, culture intersects with science and cultural rights inform how the right to science, and participation in science in all the guises we have discussed, must be interpreted.

In the ICT arena, given the transnational nature of Internet platforms and networked communication and interaction, such interdisciplinary and international collaboration gains greater significance. We have identified a problematic divide between the way human rights have traditionally mediated the relationship between the individual and the State, but not between the individual and private entities. Yet private entities, even those with purely commercial incentives, can and should play an important role in facilitating this relationship. Such actors have changed the appearance of the rights landscape, and human rights thinking will need to adapt as a consequence. Human rights scholars and practitioners must find like-minded allies in the private arena. Until we actually come together in discussions on issues that impact law and policy, it doesn’t matter what guiding principles we may have for businesses. These are not binding instruments, so we must always be keen to have further conversations in order to actually make rights collaboration a reality on the ground. CESCR has said very clearly that the State where an individual is a citizen has responsibilities, duties, and obligations in respect of rights, but that in reality it doesn’t always work that way. Private entities, particularly influential nonstate actors like Internet platforms, actually have, we believe, a part to play in removing lacunae and ensuring compliance with rights.

6.8 Concluding Remarks

It remains to be seen what impact the CESCR’s General Comment 25 will have, but it seems clear it is a stepping stone to something else; the opening of a door to a more complex, nuanced debate and, perhaps, a renewed importance for the right to science, and an evolving role in the protection of other human rights. It highlights, we believe, the need for (1) a broader perspective on the right to science, and (2) concrete mechanisms for giving effect to its core principles outside of human rights law. One clear statement it makes is to emphasize the symbiotic relationship between the right to science and cultural rights. We repeat the following: “Cultural life is an ‘inclusive concept encompassing all manifestations of human existence’ … Thus, the right of everyone to take part in cultural life includes the right of every person to take part in scientific progress and in decisions concerning its direction.”

For the justiciability of the right to science to become a reality, we must recognize that the modern landscape of rights and technology is complex and nuanced, and raises many unknowns. A useful approach might be to pick perhaps one or two discrete areas of concern in order to determine what it is that can really be done and which would allow a certain balance to be achieved, rather than attempting to solve the whole problem at once. Collaboration, as envisaged by the drafters of the UDHR and as required now in the interdisciplinary contexts we believe are necessary, involves steep learning curves for all involved, and a willingness to step out of comfort zones and be vulnerable. All involved will be characterized by their own compulsions and obligations, whether they are representatives of a State’s executive organs and institutions, or human rights practitioners and scholars, or those with private commercial interests. We must attempt to understand each other’s interests and obligations, and see the discourse from the perspective of those on the opposite side.

Science can and should be common ground; a way of thinking and approaching the problems critically, but also a means by which knowledge production and serendipity can be optimized. Academics from different disciplines, who are steeped in those scientific ideals of testing and refuting, are one way in which that interactive discourse can be facilitated. Perhaps most importantly, in the digital age, is the need for technology professionals and technology industry representatives, particularly those with some influence within their organizations as well as independent experts, to be present and to engage fully and openly. And while it would be valuable to have some of these groups formally discussing these areas under the auspices of international organizations like the UN and UNESCO, through the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the principal treaty bodies, it is important given how swiftly technology moves, to have adaptable frameworks for discourse and informal policy advice that is truly interdisciplinary and diverse.

7.1 Introduction

The promotion of justice, the rule of law, and human rights as prerequisites for the consolidation of peace and security is common ground in the United Nations (UN) system. The uniqueness of the mandate of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) lies in the specificity of its pathway and its approach to peace. For UNESCO, the achievement of these goals is promoted through greater “collaboration among the nations through education, science and culture” (Article 1 UNESCO Constitution).Footnote 1 In addition to delineating the Organization’s playing field, this proclamation carries a double symbolic value. Firstly, it presages the inclusion of a science-related human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Secondly, it places emphasis on the significance of international cooperation and exchange if science is to fulfil its role in promoting human well-being. While education is a field where competition among UN agencies grew considerably over the years, the broad domains of science and culture are still mainly the prerogative of UNESCO.

By virtue of this mandate, UNESCO has adopted legal instruments and has developed programmes and activities in the field of science and human rights, most notably in the field of bioethics and the ethics of science. Its Member States have created several bodies to advise on issues and challenges relating to these topics: the Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (IGBC)Footnote 2 composed of representatives of Member States; the International Bioethics Committee (IBC)Footnote 3 composed of independent experts; and the World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST),Footnote 4 also composed of independent experts.

The articulation of human rights and science is interwoven with UNESCO’s efforts to implement new global frameworks such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the New Urban Agenda. It was also an important dimension of the Organization’s responses to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach builds on UNESCO’s lead role in the Scientific Advisory Board, the UN expert body that was established in 2013 to bring science to the core of the sustainable development agenda.

This contribution discusses how UNESCO has worked on human rights in relation to science, and on science in relation to human rights with emphasis on standard-setting. It attempts to foreground the core approaches underpinning these efforts; to highlight the evolution in the Organization’s thinking; and to show to what extent these are aligned with and promote the advancement of the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress as included in human rights instruments, in particular the dimensions of scientific freedom, protection against harm, benefit sharing, and international cooperation.

7.2 Foundations of UNESCO’s Action on Human Rights

7.2.1 Mandate

The vision of an inextricable link between peace and the realization of human rights is the foundation of UNESCO’s mandate and its work in this domain. The Organization’s constitutional commitment was immediately translated into action. UNESCO contributed to the reflection underpinning the elaboration of the UDHR. Through a committee especially created in 1947, UNESCO studied the philosophical foundations of human rights in order to foreground convergences between various cultures and schools of thought.Footnote 5 UNESCO was also the first UN entity that undertook to disseminate information about the UDHR through mass communication programs and teaching materials in schools, and to incorporate it in its programs.Footnote 6 In the following decades, drawing on its normative action, UNESCO contributed to the promotion of human rights in its fields of competence through research, capacity development, advocacy, and agenda-setting.

While UNESCO’s constitutional mandate is broad and covers the promotion of all human rights, its action focuses on the rights directly linked to its mandate. These include: the right to education; the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including the right to seek, receive, and impart information; the right to take part in cultural life and artistic freedom; the right to water and sanitation; and the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications.

UNESCO’s general commitment to human rights mainstreaming was reaffirmed in the early 2000s. The Organization’s 2003 Human Rights Strategy elevated the integration of a human rights-based approach (HRBA) in all its activities to a house-wide priority. This UN-wide approach, forged out of the momentum of the 1997 UN Reform, implies that the work of UN Agencies and Programmes, including that of UNESCO, is guided by human rights principles, as laid down in the UDHR and other international human rights instruments. These principles include: universality; indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights; equality and nondiscrimination; participation and inclusion; accountability; and the rule of law.Footnote 7 HRBA is a key programming principle in UNESCO’s Medium-Term Strategy for 2014–2021, reaffirmed in the draft Medium-Term Strategy for 2022-2029Footnote 8, and a cornerstone for the implementation of gender equality, one of the Organization’s two global priorities.Footnote 9

The right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications is included in Article 27 UDHR and in Article 15(1)(b) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). These instruments recognize that this right includes the right of individuals to enjoy the benefits of scientific advancement and the rights of scientists to freely conduct science and to have the results of their work protected. Another inherent component of the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications is the protection from possible harmful effects of science. A cross-cutting dimension of this right, and of the Covenant, is international cooperation.

UNESCO has actively supported the elaboration of this right. Most importantly, it drew the right from its oblivion by initiating a series of experts’ meetings that led to the adoption by a group of experts of the Venice Statement on the Right to Enjoy the Benefits of Scientific Progress and its Applications in July 2009.Footnote 10 This statement aimed to clarify the normative content of the right, as well as to generate discussion among all relevant stakeholders with a view to enhancing its implementation.

7.2.2 UN Global Frameworks

Being part of the UN family, UNESCO’s work fits within a broader context defined by human rights-driven global action frameworks, most notably the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs, and the New Urban Agenda. Agenda 2030 and the SDGs embody an unprecedented universal consensus on key prerequisites for sustainable human development that are anchored in human rights. Guided by the commitment of “leaving no one behind,” Agenda 2030 marks a paradigm shift towards an inclusive and transformative vision of human development that establishes clear imperatives for the UN system regarding respect for, protection of, and fulfilment of human rights. Moreover, acknowledging their close interconnection, Agenda 2030 endorses a holistic approach to the set of challenges at hand, significantly expanding the list prioritized by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and making the elimination of inequalities a transversal thread. Contrary to previous political commitments, Agenda 2030 constitutes – to paraphrase the preamble of the UDHR – “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations” towards which all efforts must converge. Interestingly, science is a cross-cutting thread of Agenda 2030. The preamble’s acknowledgement of science, technology and innovation (STI) as a key driver for sustainable development, is mirrored by the inclusion of as many as twenty-three STI-related SDG targets.

The New Urban AgendaFootnote 11 localizes the commitments of Agenda 2030 and the content of the SDGs by acknowledging that local authorities are also responsible for protecting, respecting, and fulfilling the human rights of the inhabitants at the city level, in line with central governments.

UNESCO has placed the implementation of Agenda 2030 at the core of its action. The Organization focuses on and contributes significantly to nine SDGs, namely: SDG 4 (Quality Education); SGD 5 (Gender Equality); SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation); SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure); SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities); SDG 13 (Climate Action); SDG 14 (Life below Water); SDG 15 (Life on Land), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).Footnote 12 In connection with these SDGs, UNESCO has the following key roles: internationally recognized global or shared leadership and coordination; monitoring and benchmarking; global advocacy to sustain political commitment; leading or co-leading global multi-stakeholder coalitions; normative mandate and provider of upstream policy support and capacity development. Furthermore, the Organization contributes to SDG 1 and 10, and is concerned with aspects of SDG 17.Footnote 13

Table 7.1 Science Technology and Innovation (STI) and Agenda 2030

| Areas explicitly mentioned in Agenda 2030 | SDGs making explicit references to STI | SDG targets making specific references to STI |

|---|---|---|

| Science | 4; 14 | 4.b ; 14.3 ; 14.4 ; 14.5 |

| Technology | 1; 2; 5; 6; 7; 9; 17 | 1.4 ; 2.a ; 5.b; 6.a ; 7.a; 7.b ; 9.4 ; 9.a ; 9.c; 17.7 ; 17.16 |

| Innovation | 8 | 8.2 ; 8.3 |

| STI | 9; 12; 14;17 | 9.5 ; 9.b; 12.a ; 14.a ; 17.6 ; 17.8 |

7.3 UNESCO’s Approach to Science and Human Rights

UNESCO’s work in the field of science and human rights, and in particular the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, has evolved significantly. The Organization has explicitly focused on promoting an ethical and rights-based approach to the advancement of science and technology, inter alia, by fostering the rights and freedoms of scientific researchers and an equitable sharing of the benefits of that research. It has also addressed the ethical challenges deriving from cutting-edge science, for instance in connection with bioengineering and biotechnology, and, more recently artificial intelligence, big data, and the Internet of Things. Its work has also supported a stronger interlinkage between scientific evidence and policy-making and it has fostered gender equality in sciences by strengthening the opportunities of women. A good example of the last is UNESCO’s program For Women in Science, which it has hosted since 1998 in cooperation with L’Oréal. The motto of this program is “the world needs science, science needs women.” It aims to reward excellent female scientists for their important contributions to the progress of science, either in life sciences or in the fields of physical sciences, mathematics, and computer science. In the last 20 years, more than 3100 scientists from 117 countries have been supported and more than 50 countries grant national and regional scholarships under the flag of this program.Footnote 14

7.3.1 Early Approaches: Do No Harm, Benefits Sharing, and International Cooperation

In the decades after the adoption of the ICESCR, States focused on three aspects of science. The first aspect was promoting “the optimum utilization of science and scientific methods for the benefit of mankind and for the preservation of peace and the reduction of international tensions.”Footnote 15 The second was to address “dangers which constitute a threat, especially in cases where the results of scientific research are used against mankind’s vital interests in order to prepare wars involving destruction on a massive scale or for purposes of the exploitation of one nation by another, and in any event give rise to complex ethical and legal problems.”Footnote 16 Finally, States aimed to promote international cooperation so that the full potential of scientific and technological knowledge could be promptly geared to the benefit of all peoples.Footnote 17

These dimensions were explicitly included in the Recommendation on the Status of Scientific Researchers, adopted by the Member States of UNESCO in 1974. The Recommendation calls upon States to foster an environment where scientific researchers can “contribute positively and constructively to the fabric of science, culture and education in their own country, as well as to the achievement of national goals, the enhancement of their fellow citizens’ well-being, and the furtherance of the international ideals and objectives of the United Nations.”Footnote 18 At the same time, the Recommendation allows States a considerable margin of appreciation. Deviations from the Recommendation are acceptable under the condition that the cases where these apply are specified “as explicitly and narrowly as possible.”Footnote 19

This three-pronged approach of States is also included the Recommendation concerning Education for International Understanding, Co-operation and Peace and Education relating to Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms adopted at the same time. Specifically, the Recommendation recognizes as an integral part of human rights education the duty to promote “the inadmissibility of using science and technology for warlike purposes and their use for the purposes of peace and progress.”Footnote 20 The Recommendation also underscores the role of education in harnessing the power of knowledge towards problem-solving and the critical role of international cooperation in this regard.Footnote 21

Another general feature of UNESCO’s approach is the importance allocated to culture. In a reply to a survey by the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1976, the Organization’s Director-General observed that science and technology “are merely the instruments for carving out decisions made elsewhere – what we find at the fountainhead of the long and complex chain of those decisions but the determining factor of culture?” Hence, “the use made of science and technology, like pure science itself, is a matter of culture.”Footnote 22 The role of culture is underscored later on in the context of reflection about ethical considerations in relation to scientific discoveries and the progress of technology. A valuable dialogue between cultures is seen as crucial for bioethics, in the same way as the breaking down of barriers between disciplines.Footnote 23

The approach and emphasis of the two Recommendations of 1974 actually underpin the several instruments related to science adopted around the same time in the broader context of the UN. Most of these concentrate on international cooperation in the field of science and on the possible harmful effects of science and technology with a focus on the duties of States and scientists to promote, conduct, and use science in a responsible way. For example, the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1974, recognizes a right of States – not of individuals – to benefit from scientific advancement and developments in science and technology. It also calls upon States to promote international scientific and technological cooperation and the transfer of technology to developing countries, as well as facilitate access of developing countries to the achievements of modern science and technology (Article 13).

Similarly, the Declaration on the Use of Scientific and Technological Progress in the Interests of Peace and for the Benefit of Mankind, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1975, concentrates on the possible abusive use of science contrary to human rights. Its preamble acknowledges that scientific and technological achievements could improve the conditions of peoples and nations and, at the same time, cause social problems or threaten human rights and fundamental freedoms. Other issues in this Declaration include non-discrimination and international cooperation to ensure that the results of science and technology are used in the interests of peace and security, and for the economic and social development of peoples. It is further laid down that States should prevent the use of scientific and technological development to limit the enjoyment of human rights and protect the population from possible harmful effects of the misuse of science and technology (Article 2).

7.3.2 Emphasis on Science and (Bio-)Ethics

About two decades later, UNESCO initiated the adoption of several international instruments relating to science in relation to ethics and bioethics. The Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights, adopted by UNESCO’s General Conference in 1997 and endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 1998, focuses on the potential abuse of science and research. In this sense, it echoes a series of General Conference resolutions that express concern and call upon UNESCO to take initiatives around such abuse of science, such as the development of sophisticated weaponry.Footnote 24 The Declaration states, for instance, that researchers have special responsibilities in carrying out their research, including meticulousness, caution, intellectual honesty, and integrity (Article 13). It also states that persons have the right to be informed about research on their genome and that such research should in principle not be carried out without a person’s consent. If such consent is not possible, research should be carried out only for the person’s health benefit or the health benefit of others (Article 5). The Declaration also urges States to promote international dissemination of knowledge, in particular between industrialized and developing countries (Article 18).

The idea of sharing the benefits of science is more clearly present in the International Declaration on Human Genetic Data, adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO in 2003. According to this Declaration, the benefits of science, including access to medical care, the provision of new diagnostics, facilities for new treatments or drugs deriving from research, and support for health services, should be shared with society as a whole and with the international community (Article 19).

An explicit reference to the sharing of benefits of science can be found in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, adopted by UNESCO’s General Conference in 2005. Article 15 includes that “[b]enefits resulting from any scientific research and its applications should be shared with society as a whole and within the international community, in particular with developing countries.” Part of such benefits could be access to scientific and technological knowledge (Article 15(1)e). This provision focuses more on the sharing of the results of science and less on the advancement of science or the freedom to conduct science. UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee (IBC) extensively elaborated on the concept of benefit sharing in a report issued in 2015.Footnote 25 It explicitly linked Article 15 of the Declaration to Article 27 UDHR and Article 15 ICESCR. It reaffirmed the importance of sharing the benefits of science with society as a whole, and with the international community, while also addressing the possible tradeoff with the protection of intellectual property and patents. The IBC further maintained that sharing should be seen as participation and not as top-down beneficence, emphasizing the importance of capacity building and science education, open access to information, and empowerment and participation in the production of knowledge.

7.3.3 Broadening the Scope: Science-Based Decision Making

7.3.3.1 UNESCO Declaration of Ethical Principles in Relation to Climate Change

In recent years, UNESCO’s work in the field of science and human rights was given a new impetus. Much influenced by the global discussions on sustainable development and climate change, Member States of UNESCO elaborated and adopted in 2017 the UNESCO Declaration of Ethical Principles in relation to Climate Change. This Declaration emphasizes the fundamental importance of science, technological innovation, relevant knowledge, and education for sustainable development in the response to climate change. Several of the human rights dimensions of science, such as prevention of harm and international cooperation, are reflected in the Declaration. The Declaration adds an important new dimension in relation to science and human rights, namely the promotion of decision-making based on science.

As regards the prevention of harm, the Declaration maintains in Article 2 that people should aim to “anticipate, avoid or minimize harm, wherever it might emerge, from climate change, as well as from climate mitigation and adaptation policies and actions.” Science is also relevant in relation to another dimension of possible harm, namely the precautionary principle. Article 3 states that: “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible harm, a lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to anticipate, prevent or minimize the causes of climate change and mitigate its adverse effects.”

International cooperation is included in several parts of the Declaration. For instance, Article 2 states that States should “seek and promote transnational cooperation before deploying new technologies that may have negative transnational impacts.” Article 7 includes that “scientific cooperation and capacity building should be strengthened in developing countries.”

Scientific freedom is less present in the Declaration, but it is included in Article 7(4) that States should “take measures which help protect and maintain the independence of science and the integrity of the scientific process.”

The Declaration adds explicit provisions on scientific knowledge and integrity in decision-making. Article 7(1) states that “decisions should be based on, and guided by, the best available knowledge from the natural and social sciences, including interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary science, and by taking into account, as appropriate, local, traditional and indigenous knowledge.” States should therefore “build effective mechanisms to strengthen the interface between science and policy to ensure a strong knowledge base in decision-making” (Article 7(4)d).

7.3.3.2 UNESCO Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers

One of the most crucial instruments by UNESCO that connects science and human rights is the Revised Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers, also adopted in 2017. This document supersedes the Recommendation on the Status of Scientific Researchers of 1974. As the Director-General noted in her report on the revision, the Recommendation reflects a “conceptual paradigm shift toward systematically addressing risks and responsibilities in science, while recognizing that the freedom of expression and conscience of researchers and their professionalism is its backbone.”Footnote 26 The idea driving the Recommendation was the establishment of closer links with the SDGs, and in particular Target 9.5 that aims to enhance scientific research. The Recommendation underscores the importance of another application of science, namely the use of scientific and technological knowledge in decision-making (paragraphs 5 (g), 7, 8, and 9).

The revised Recommendation sets out the operational standards for a contemporary and forward-looking vision for science. A main innovation of the Recommendation is the recognition that harnessing the transformative power of science requires a holistic approach, which is anchored unequivocally in human rights.

The Recommendation adopts a broad strategy, looking at the whole process of science as a departure point for determining the role of scientific researchers. In doing so, the Recommendation pays specific attention to new developments, such as the internationalization of science and mobility of scientists, the changing security and environmental concerns, the increased role of the private sector, the increased concern about the ethical aspects of the science enterprise, and the interdisciplinary nature of science, including social and human sciences. All these have led to an increased recognition that the responsibilities of scientists have widened and that a firm link with human rights is required.

Human rights is set as a cornerstone for building a sound science, technology, and innovation system indispensable for achieving sustainable development. In that spirit, the Recommendation incorporates human rights in multiple ways. By explicitly setting the human right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits (paragraph 21) as a reference point, the Recommendation broadly endorses its different elements, including the sharing of its benefits, academic freedom, protection from possible harm, and international cooperation. It also refers to the human rights of scientists, the rights of people to access knowledge produced by science, and the rights of people affected.

Among its many important principles, three deserve to be highlighted in this context. First of all, emphasis is placed on the responsibility of science towards UN ideals of human dignity, progress, justice, peace, welfare of humankind, and respect for the environment (paragraph 4) and the need to subject scientific conduct to universal human rights standards (paragraphs 18a,e, 20a,b,c, 21, 22, 42). As a result, science should be fully integrated into efforts to develop more humane, just, and inclusive societies. A second feature relates to the need for science to interact meaningfully with society and vice versa towards tackling global challenges (paragraphs 4, 5 c, 13d, 19, 20, 22). This calls for the active participation of society in science and research in a democratic and horizontal manner, through the identification of knowledge needs, the conduct of scientific research, and the use of results. Finally, the Recommendation promotes science as a common good (paragraphs 6, 13e, 16a–v, 18b,c,d, 21, 34e, 35, 36, 38). According to the text, this entails that public funding of research and development should be perceived as a form of public investment, the returns on which are long-term and serve the public interest. Likewise, States should facilitate and encourage open science, including the sharing of data, methods, results, and the knowledge derived from it, in view of its potential benefits. It also entails the removal of obstacles preventing women and other underrepresented groups from receiving, on an equal footing, basic education, training and, ultimately, access to employment in scientific fields.Footnote 27

7.3.3.3 UNESCO and the UN Scientific Advisory Board (2013–2016)

The work of UNESCO in the UN Scientific Board is also worth brief exploration. The need to bring science to the core of the sustainable development agenda was acknowledged by the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Global Sustainability in its report entitled “Resilient People, Resilient Planet: A Future Worth Choosing,” adopted in January 2012.Footnote 28 Beyond addressing global challenges, the Panel insisted on the importance of a strengthened science policy interface as a necessary complement to efforts on economic and social aspects, and factors such as inequalities. The Panel considered that this objective could be best achieved either by “naming a chief scientific adviser or establishing a scientific advisory board with diverse knowledge and experience” (Recommendation 51, page 75).

UNESCO played a decisive role in taking this Recommendation forward. It convened the Executive Heads of UN organizations with a science-related mandate and representatives of major scientific bodies into an ad hoc group mandated to provide advice to the SG and the UN system as a whole. Recognizing the strategic opportunity, the ad hoc group opted for the establishment of a representative body, the Scientific Advisory Board. This body came into being in September 2013. UNESCO hosted its secretariat and the UNESCO DG took the lead in establishing the body and taking up the function of its chair.Footnote 29

The Scientific Advisory Board was given an ambitious mandate. Its areas of focus included improving coordination among UN entities having a mandate in science, technology, engineering, and humanities; avoiding mission creep and overlap and curbing counter-productive competition; advising on 2030 Agenda science priorities; and providing insights on the promotion of democratic global governance for a responsible and ethical development of science that reinforces sustainability.Footnote 30

To fulfil its mandate, the Board was tasked to connect and mobilize all relevant scientific fields for the purpose of fostering coherence. And so it covered the basic sciences, engineering and technology, social science and humanities, ethics, health, economic, behavioral, environmental, and agricultural sciences.

Thus defined, the mandate given to the Scientific Advisory Board opened important avenues for connecting science with human rights considerations. The final report of the Scientific Advisory Board with its main findings and recommendations, submitted in September 2016, reveals that human rights-related considerations were on its radar. First of all, it explicitly recognized science as a public good, which deserves to be valued more highly, employed more widely, and used effectively by decision-makers at all levels.Footnote 31

A corollary to considering science a public good was the emphasis on a society-policy-science interface. The science process should thus involve a diversity of stakeholders, including government, civil society, indigenous peoples and local communities, businesses, academia, and research organizations, each with their own accountabilities. This way, the Board considered, the diverse perspectives and priorities could be synthesized in a manner aligned with the evidence and serve the long-term interests of society and the planet.Footnote 32

Another important aspect related to human rights is the advocacy for a holistic approach to science with emphasis placed both on knowledge production for innovation (basic research) and applied research, as well as on linking such factors as health, education, opportunity, incomes, social mobility, and nutrition. This reaffirmed the close interlinkages between the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and other human rights related to health, food, labor, and education.

Finally, the influence of human rights and the “leave no one behind” vision of Agenda 2030 is evident in its emphasis on inequalities. The report calls for co-designing and co-ownership by all as the basis for developing science, technology and innovation across the board. It stresses that the complexity of today’s world and its challenges require the mobilization of resources and assets in all parts of the world, developing and developed, as it passes imperatively through the elimination of gender disparities.Footnote 33

A full assessment of the work of the Scientific Advisory Board is outside the scope of this contribution. However, it is fair to say that the Board partially met the expectations surrounding its creation. Counted among its strengths and positive contributions are its call for a more central role for science in fostering sustainable development and also the emphasis on a holistic approach to science. Another is its echoing of fundamental principles of Agenda 2030, in particular transparency, participation, and inclusion, and the elimination of inequalities. It is probably no coincidence that these elements were key to the vision for science embodied in the 2017 Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers. Yet, the Board did not succeed in building the case for a holistic approach to human rights with the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications at its core, at least not using explicit terms. That was a missed opportunity. A strong recommendation towards such an orientation at the beginning of the SDG era could perhaps have helped integrate a human rights lens into the monitoring process of specific targets and indicators.

7.4 Concluding Remarks

The significant role of science in consolidating peace, fostering human well-being, and achieving sustainability cannot be overestimated. Hence, it is only natural that science, technology, and innovation were woven into the fabric of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, cutting across virtually all of the seventeen SDGs, including their targets and means of implementation.

This contribution shows that UNESCO, with its specific mandate in the field of science, has worked on human rights in relation to science, and on science in relation to human rights, in many different ways. Shifting over the years from a narrower to a more holistic approach, it has developed numerous instruments that connect the advancement of science to ethical and human rights standards and principles. These include academic freedom and protection of the rights of scientists, protection against harm, sharing benefits of scientific and technological advancements, including related knowledge and their applications, international cooperation and, more recently, science-based decision-making. In addition, UNESCO embarked since November 2019 on the elaboration of two new instruments: on ethics of artificial intelligenceFootnote 34 and on open science,Footnote 35 potentially enhancing the science-related normative arsenal. Standard-setting efforts have been reinforced by converging advocacy initiatives such as the Joint Appeal for Open Science, launched by the leadership of UNESCO, WHO and OHCHR in October 2020. The appeal acknowledged the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications as the cornerstone of efforts to promote open, inclusive and collaborative science. The idea of linking science to human rights has clearly underpinned UNESCO’s position and advice during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, it is a central tenet of the statements issued by the Organizations’ ethics bodies, COMEST and IBC on global ethical considerations and on global vaccines equity and solidarity.Footnote 36

It should be noted that all UNESCO science-related instruments – being declarations or recommendations and not treaties – are not legally binding upon States. Moreover, their monitoring is mostly State-drivenFootnote 37 and therefore not comparable to that relating to UN human rights treaties and their expert bodies.

Yet, these instruments demonstrate a large degree of consensus among States on the need to promote science as a public good accessible to all and to integrate human rights norms and principles into the advancement and promotion of science and technology and related policies. At the same time, it is important that the articulation of the link between science and human rights goes beyond the realm of aspirations.

The General Comment on science and economic, social and cultural rights,Footnote 38 adopted by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, is a milestone in removing some of the normative ambiguity. The General Comment reserves an important place for the work of UNESCO. Further to reiterating the definition of science developed by UNESCO, the General Comment recognizes particularly the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights and the Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers, as sources of inspiration for the elaboration of the relationship between science and human rights. The various dimensions of academic freedom,Footnote 39 protection against harm,Footnote 40 sharing benefits of scientific and technological advancements,Footnote 41 international cooperation,Footnote 42 and science-based decision-makingFootnote 43 – that the Committee considers part of the core obligations of States in the implementation of the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progressFootnote 44 – are prominent in those UNESCO instruments.