Introduction: Beyond the revolving door?

In a competitive market for lobbying talent, employers seek out and engage those individuals whose experiences best help them fulfil crucial advocacy tasks. For employers, the accumulated prior experiences of an individual provides a guide as to their likely future capability. But what precisely are the range of work experiences that make a lobbyist valuable? And, what prior roles actually differentiates a given lobbyist from their peers?

The lobbying literature focuses heavily on the ‘revolving door’, which emphasises the centrality of prior direct experience within government to the market value of would be lobbyists, and has a strong focus on the first moves of former legislators into the lobbying world (Belli & Bursens, Reference Belli and Bursens2021; Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016; LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017; McCrain, Reference McCrain2018; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Buhman‐Holmes and Egerod2021). This is despite a recognition that the lobbying profession requires a broader skill set than just insider knowledge of political processes: it is more than just ‘who you know’ (Holyoke et al, Reference Holyoke, Brown and LaPira2015). But what skill sets or experiences do lobbyists actually possess? Is direct political experience really the jump off point for most lobbyist's careers? What evidence is there of variation in these career trajectories? And do different types of employers – say contract lobbying firms versus corporations or interest groups – hire lobbyists with different backgrounds?

Evaluating the career experiences that lobbyists leverage in their role is consequential for political science. For one, it helps us evaluate our democratic systems against the normative expectations of pluralistic competition among interests. Scholars and society at large have long voiced a concern that individuals parlay their knowledge, skills and experiences accumulated in political office into post‐political careers in lobbying (Heinz et al., Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993; LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Buhman‐Holmes and Egerod2021). At issue is the worry that inside knowledge and, even more so, personal connections within government can be exploited by individuals who move into the influence industry, and in so doing jeopardise the public interest. Measured against the aim of ‘un‐biased’ competition among organised‐interests within our pluralistic democracies (see Lowery et al., Reference Lowery, Baumgartner, Berkhout, Berry, Halpin, Hojnacki, Klüver, Kohler‐Koch, Richardson and Schlozman2015; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge and Petracca1992), the inference is that those who can afford to hire individuals with prior government experience will gain an unfair representational advantage. High profile cases of former politicians working for big‐money clients, does little to allay these fears. Second, and relatedly, studies demonstrate a link between government experience and personal or policy outcomes. Some US work finds that former elected officials gain market premiums over their peers (Blanes i Vidal et al., Reference Blanes i Vidal, Mirko and Christian2012; McCrain, Reference McCrain2018), while others have reported that hiring so‐called ‘covered officials’ by organised interests is associated with positive outcomes in regulatory politics (Baumgartner et al, Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009, p. 208; Lazarus & McKay, Reference Lazarus and McKay2012). To address (or indeed confirm) these types of concerns, we need to know much more about the lobbyists themselves, their patterns of career employment and the centrality or otherwise of political experience in the journey into lobbying. While there is a burgeoning literature focused on how organisations lobby, influential scholars have lamented the absence of sustained research attention on who does the lobbying (Lowery & Marchetti, Reference Lowery and Marchetti2012).

Existing empirical work mapping lobbyist careers is sparse (but see Heinz et al., Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993). On the one hand, a range of mostly US contributions focus on whether an individual lobbyist has direct political experience (LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017), and find that former elected officials gain market premiums over their peers (Blanes i Vidal et al., Reference Blanes i Vidal, Mirko and Christian2012; McCrain, Reference McCrain2018). They look at the entire lobbying workforce, yet only record the presence (or absence) of this single facet of an individual's previous work experience. On the other hand, the few studies that have noted a far broader set of prior work experiences (extending to work in industry, think tanks and media), do so only for a small sliver of the lobbying workforce, namely corporate in‐house staff (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). Saliently, and in contrast to US work, this study suggests that there is a ‘sliding door’ in operation, whereby corporate lobbying staff in the European Union (EU) tend to either generate expertise rooted in a longstanding industry career or else gather political contacts originating in government service: there is a distinct private or public career path. This points to the importance of other career experiences beyond direct government work, but its generalisation beyond corporate in‐house staff leaves unanswered questions.

There is also work on the post‐legislative careers of politicians, which examines the ‘revolving door’ from the perspective of the vocations of former elected officials immediately upon leaving office (Claessen et al., Reference Claessen, Bailer and Turner‐Zwinkels2021; Weschle, Reference Weschle2021). Here US evidence shows that while many former legislators do seek work in the private sector as lobbyists, many also end up on corporate boards (Palmer & Schneer, Reference Palmer and Schneer2019). In this paper we take a related but different approach, looking at who ends up in lobbying roles and the career journey that got them there.

In this study we move the literature forward by (1) offering a new national case, namely Australia, (2) analysing individual lobbyists’ careers through observational data cataloguing a broad range of accumulated relevant work experiences and (3), in the one study, comparing the workforce across in‐house and contract lobbyists via the tool of sequence analysis. Based on a dataset including over 600 individual lobbyists active at the national level in Australia in 2018, we track their prior careers leading to their role as a lobbyist. Similar to Coen and Vannoni (Reference Coen and Vannoni2016), we catalogue their careers according to one of 12 possible roles, and from these data construct individual career sequences. Analysis of these career sequences, via a clustering approach used widely in the analysis of political careers in political science (see Jäckle & Kerby, Reference Jäckle, Kerby, Best and Higley2019), allows us to identify types of lobbying careers. We find that direct political experience is a central component of most lobbying careers. Yet, this is not what distinguishes types of lobbyists, nor explains whether one works as a contract or in‐house lobbyist. The ubiquitous place of political experience in the careers of almost half of lobbyists means that other politically adjacent roles and experiences are what drives most meaningful distinctions among types of lobbyists. When clustered into types of lobbying careers, these do not parse into a simple straightforward distinction between those with and without political experience. Instead, consistent with the range of functions that scholars argue are central to professional lobbying (Althaus, Reference Althaus2015; Holyoke et al, Reference Holyoke, Brown and LaPira2015), we find that professional backgrounds in communications, journalism, industry and associations are what distinguish among the diverse career trajectory of lobbyists. We find evidence of a revolving and sliding door working in combination in the Australian lobbying sector, with individuals combining policy experience with a deepening career in one or other politically adjacent sectors, that is, associative, corporate or communications. It is through this combination, we argue, that lobbyists develop both political contacts and substantive policy expertise and knowledge.

Lobbyists’ careers and accumulating work experiences

Exchange and access

Our shared understanding of routine political lobbying in contemporary democracies is that legislators or policymakers require information of different types (e.g., technical or political) and that the relative value of, or demand for, these types of information are set by the institutional context (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017). In Europe, for instance, it is generally assumed that the Commission is focused on technical knowledge, while the Parliament and MEPs seek political knowledge (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2020). By contrast, in the US Congressional setting, personal contacts are critical in shaping levels of access to legislators and their staff (LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017). In turn, we expect that lobbyists who are prima facie best equipped (by virtue of past work experiences) to gain access will be more sought after by employers: whether as in‐house staff within interest groups or corporations, or as staff for hire within commercial lobbying firms. In a market for lobbying talent, employers can be understood as strategic actors rationally seeking out those best equipped to do the job in the prevailing institutional setting.

Building on recent work on lobbying in the United States and Europe, we conceptualise the choice by an organization to hire a lobbyist – either as a permanent staff member or via a contract lobbying firm – as recognition that it requires particular capacities in order to effectively influence public policy (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016; LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017). This basic setup provides a foundation for considering how the choices of who to hire as a lobbyist shapes prospects for access, and, how this might change with the institutional context. Organised interests spend their finite financial resources on human capital, in the form of lobbying staff, with the basic goal of gaining access to policymakers in order to advocate. Assuming they have an adequate understanding of the demand for resources from policymakers, we would expect organised interests to hire lobbyists who are best equipped to generate these resources or access goods in the most efficient manner. This brings us directly to the issue of lobbyists’ experiences.

Variations in lobbyist experiences

Not all lobbyists are created equal. Some possess qualities that are more or less valuable to employers, clients (if working in contract lobbying), and policymakers (those they seek access to). The literature suggests the capacity of individual lobbyists to generate access goods flows from their prior career experiences. However, we still know remarkably little about the actual diversity of work experiences and careers of lobbyists. Almost half a century ago, Berry (Berry, Reference Berry1977, p. 92) called for scholars to ask employers what it is they look for when hiring lobbyists. Yet, with the exception of an early survey‐based study (Heinz et al., Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993), the literature has only just started to explore the career experiences of political lobbyists. Our work here is guided by three related basic propositions: (1) that political experience is decisive in lobbying careers, (2) that the salience of political experience within careers is divergent between in‐house and contract lobbyists or (3) that the experiences of all lobbyists are understandably very diverse (because the task requires many skill sets). We review each in turn.

The focus on revolving door politics has directed scholarly attention to the importance of political knowledge and contacts in securing work in the lobbying fieldFootnote 1. It is well accepted, for instance, that lobbyists with prior experience in politics – so‐called ‘revolvers’ – are sought after. Citing classic work in the field (Deakin, Reference Deakin1966), Heinz et al. (Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993; Herring, Reference Herring1929, p. 105) summarized the revolving door hypothesis as an expectation that ‘the ranks of lobbyists are filled by people who have moved to the private sector from positions in government’Footnote 2. A string of US studies confirms that many lobbyists in Washington have come from roles within politics. Classic work in the field reported up to 50 per cent of all lobbyists having held prior posts in government (Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1963, p. 68; see also Berry, Reference Berry1977). Recent studies have largely reconfirmed these findings. Lazarus et al. (Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016) find that a quarter of the US House of Representatives and a third of Senators between 1976 and 2012 became lobbyists. In their study, LaPira and Thomas (Reference LaPira and Thomas2014) find that half of the lobbyists in Washington have experience within federal government. Research often points to the salience such experiences have on policy outcomes. Studies have reported that hiring so‐called ‘covered officials’ by organised interests is associated with positive outcomes in regulatory politics (Baumgartner et al, Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009, p. 208; Lazarus & McKay, Reference Lazarus and McKay2012)Footnote 3.

Yet, precisely what vital skills or knowledge are generated from prior direct political experience is still debated. Studies from the United States show that lobbyists who specialise in a specific policy field gain greater access to relevant congressional committees of policy‐making institutions (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Bombardini and Trebbi2014; Cameron & de Figueiredo, Reference Cameron and de Figueiredo2013). This points to the value of lobbyists possessing substantive technical policy knowledge. Others point out that the income of former staffers‐turned‐lobbyists declines once their former boss in Congress retires or is defeated at an election (Blanes i Vidal et al., Reference Blanes i Vidal, Mirko and Christian2012), that lobbyists tend to follow members of Congress from committee to committee (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Bombardini and Trebbi2014), and that revolving door lobbyists with more ties to staffers will generate higher levels of revenue (McCrain, Reference McCrain2018). These findings point to political contacts and process knowledge as most valuable. Whether either or both are correct, the literature accepts that individual lobbyists vary in relation to the value they hold to clients and/or employers, and that this likely covaries with prior direct political experience.

This leads us to Proposition 1: ‘Decisive’ – Direct political experience is a dominant core in the careers of lobbyists.

It is possible, however, that direct political experience – and the skills or capacities it confers on individuals who have occupied those roles – are less crucial for some lobbying settings than in others. Previous work has found that revolving door lobbyists, most of whom have worked in Congress, are more often employed as contract or commercial lobbyists as opposed to in‐house lobbyists (LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2014, 17)Footnote 4. This makes intuitive sense when one considers that a contract lobbyist has multiple clients. We might expect they are less likely to possess deep and narrow subject matter competence, but instead offer their broad and diverse client base inside political connections and a working knowledge of governmental processes and institutions. If a contract lobbyist works for a company in the morning, an interest group after lunch and briefs an institutional client in the afternoon, their value add is most likely to be of a process nature. Direct governmental experience seems most likely to parlay into this kind of skill set. An alternative rationale for the association between political experience and contract lobbying work is that it is an artefact of the propensity for former elected officials to establish their own contract lobbying firms upon leaving office; a trend observed in the Congressional setting (Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016, p. 96; but see Palmer & Schneer, Reference Palmer and Schneer2019). The logic is that commercial lobbyists would find selling policy expertise by the hour more difficult than political contacts and networks. And, vice versa, that interest groups and corporations would likely fix their capital in human assets who bring policy expertiseFootnote 5.

Further support for the proposition that contract versus in‐house lobbyists are hired based on their possession of divergent skill‐sets comes from some recent non‐US work on the in‐house lobbying workforce within European corporations. Evidence shows remarkably little movement between EU or national government roles and corporate lobbying: prompting the claim that corporate lobbying in Europe is more of a ‘sliding door’ than a revolving one (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). That is, there is a separation between career pathways of those in government and in corporate affairs, and that once locked into one or other path, the opportunities to switch are constrained by the need to generate specialized expertise (which takes time). Importantly, this EU works suggests that the absence of government experience in the careers of corporate lobbyists reflects the institutional environment, where demand from policymakers is for policy expertise (thus employers seek this out in employees). This prompts the question, is the value of political experience divergent, in that it matters for contract lobbyists but less so for in‐house lobbyists? Or to frame it in the language of Coen and Vannoni (Reference Coen and Vannoni2016), is it a case of revolving doors for contract lobbyists and sliding doors for in‐house lobbyists?

This leads us to Proposition 2: ‘Divergent’ – Direct political experience is more central to the careers of contract lobbyists.

Both of these propositions still focus on the centrality of direct political experience in the career pathways of lobbyists. For some it is essential to all lobbyists, for others it is assumed to be less important for in‐house lobbyists (or in institutional settings where expertise is valued more than contacts). Yet, there is also an alternative perspective: that the core skills of a successful lobbyist go well beyond the knowledge and connections one gains from direct political experience, and that individuals will accumulate valuable skills from a broad set of roles throughout careers. There are reasons to expect this account to hold. Summarising a set of very early US lobbying studies, Heinz et al. (Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993, p. 116) conclude that ‘previous government employment is a common, but far from necessary, experience for lobbyists’. Further, as LaPira and Thomas (Reference LaPira and Thomas2014, p. 9) explain, few lobbyists can afford to only provide political connections: ‘A lobbyist who has access to those in power but who cannot grapple with policy details would not be useful to any organised interest. And vice versa, a policy expert who had the ear of nobody in power will have little direct influence on the policy process’. This leaves considerable room to explore how central direct experience really is to lobbyist careers, rather than its absence or presence. Specifically, it suggests that an effective lobbyist is likely to benefit from the connections and contacts available from service within government (a revolving‐door account) and from the expertise and knowledge one develops over sustained work in a particular corporate, associational or some other lobbying context (a sliding‐door account). The model lobbyist is likely to want to have it all, and so too would their prospective employers.

Helpfully, research into the professional development needs of lobbyists confirms a broad range of ‘key’ skill areas are valuable. These include policy process knowledge, but also communications skills and relationship management (Holyoke et al., Reference Holyoke, Brown and LaPira2015). In his analysis of the skills listed in advertisements for lobbying staff in Germany, Althaus (Reference Althaus2015, p. 89) finds that prior experience in the ‘political arena’ is mentioned by a third of adverts, but prior experience in ‘lobbying’ and ‘communications/media’ are a close second and third on the list. This general take on lobbying suggests that many will, in fact, have worked in a range of relevant roles well beyond direct government experience: incorporated into Coen and Vannoni's vernacular, we should witness lobbyists walking through ‘multiple’ doors, which eschews the binary opposition between ‘sliding’ or ‘revolving’ doors.

This leads us to Proposition 3: ‘Diverse’– Direct political experience is just one of many components of lobbyists careers

Research approach

Data

Conducting analysis of lobbyists’ careers, as compared to other political agents, faces hurdles. While there are clear boundaries as to who is, and is not, an elected official or legislator in a given jurisdiction, the boundaries for lobbyists are blurred. Scholars must choose a convenient proxy for this population. In the United States, where lobby regulations at the federal level require registration of all lobbyists, there is a ready source of data to explore this phenomenon. This is not the case in many national contexts, Australia included.

Our study distinguishes two types of lobbyists. We refer to either contract lobbyists – who work on a fee‐for‐service basis for and are mostly employed by lobbying and government relations firms – or in‐house lobbyists – who are on the permanent staff of organisations who seek to engage in public policy (including interest groups, companies and other organisations). In our study, we created an original dataset comprising of the professional backgrounds of 650 lobbyists – contract and in‐house – operating at the federal level of the Australian political system. To do so, we draw data from several different sources.

(a) Contract Lobbyist dataset: We extracted all the individuals who were listed in the 2018 version of the Australian Register of LobbyistsFootnote 6. The register requires individuals who are hired by a third party, and who contact senior public servants, members of parliament and members of government, to register. While these data are not very detailed, and have limits and shortcomings (Halpin & Warhurst, Reference Halpin and Warhurst2017), they do provide as accurate a picture as possible of those individuals who have declared to be actively lobbying, at the federal level in Australia, at a given moment in time.

Our list of contract lobbyists comprised of 535 individuals. The research team scrutinised all entries in order to collect detailed information on each lobbyist. In that process we excluded a number of cases. For instance, 28 were removed as they did not, on our definition, work as a contract lobbyist.

Our analytical interest is in who individual lobbyists are, as professionals, and their pathways into lobbying. However, the Australian Register of Lobbyists offers no such information and there is simply no publicly available data source that provides these details. In order to collect these data, the authors recorded demographic information, previous employment (against 12 possible roles), current employment status and their lobbying speciality. Our approach relies on data provided by lobbyists or their firms, often through websites or platforms like LinkedIn, and available in the public domain. This means that the depth and quality of that information varies. Nevertheless, we have the best available data for the population of individuals that are the subject of this analysis. We spent countless hours searching for all of the 535 individuals on our list. At the end of this process, we excluded 71 additional entries as data quality was just so poor. This is a problem shared by all previous studies of lobbying careers (see Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016, Reference Coen and Vannoni2020). Fortunately, analysis of these omitted entries shows that they are not systematically related to key variables, such as previous government roles, seniority nor to specific lobbying firms. This leaves us with 435 unique lobbyists in our dataset, belonging to 195 unique lobbying firms.

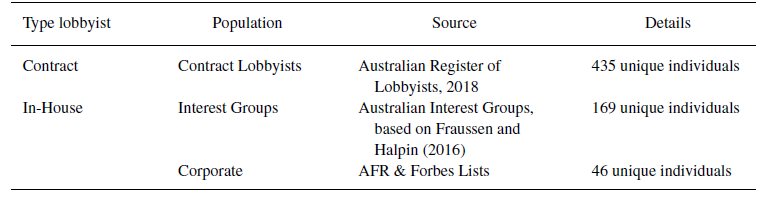

(b) In‐House Lobbyist dataset: Data on Australian in‐house lobbyists are harder to compile, as they are not required to register in the current federal system. Instead, we identified the most prominent interest organisations operating at the national level, based on previous work (see Fraussen & Halpin, Reference Fraussen and Halpin2016 for details)Footnote 7. We visited the website of each group and noted the staff who were designated as having a lobbying role or function. As with the commercial lobbying dataset, we searched group websites, professional profiles, and LinkedIn accounts, to compile the same biographical and work information for these individuals. We could not find details for 25 individuals, which left us with 169 in‐house lobbyists in our dataset. To these data we added details on the government relations manager for each of the top 50 Australian corporations. We combined the Forbes 2000 Global list (Forbes, 2019) to locate top Australian publicly traded companies and the Australian Financial Review Top 500 private companies (Australian Financial Review, 2019), ordered them from highest to lowest annual revenue. We selected the top 50 from the listFootnote 8. As with the other datasets, the most senior in‐house lobbyist working for these companies was then identified via their individual LinkedIn profile, or the company website. We could not find information for four of this sample, leaving us with 46 observations (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of data sources

Dependant variable

Our dependent variable is a binary measure which identifies if an individual currently works as an in‐house lobbyist or a contract lobbyist. As summarised above, those individuals employed by a contract lobbying or government relations firm, as registered within the Federal Lobby register, for 2018, are coded as contract lobbyists (0). All other lobbyists, in this case hired by Interest Groups or within Corporations, are coded as in‐house lobbyists (1).

Independent variable: Career experiences

Our independent variable of interest is career experience. Building on past work (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016), we coded the employment backgrounds according to 12 possible states: Academic, Corporation, Interest Groups, Journalist, Lobby Firm, Politics, PR Firm, Profession, Public Sector, Think Tank, Military and Other. We recorded multiple fields for individuals in our dataset, meaning that the same person may be counted under multiple items. In the analysis where we explore ‘political experience’, we combine having a past role in ‘Politics’ [Politics] and/or ‘Public Sector’ [PS] into a single dummy measure. For the sequence analysis, explained below, we utilise all 12 possible employment states. Separately, we also noted the specific kind of role that an individual lobbyist possessed that qualified them to be considered to have political experience.

A range of related controls are included in the multivariate analysis. We record the gender of the lobbyist (male = 0; female = 1) and the highest attained education level (secondary, post‐secondary, bachelor, law degree and post‐graduate). Descriptive statistics are in the Supporting Information Appendix, Table A.2.

Analysis approach: Descriptive, career sequences and multivariate approaches

A range of analytic approaches are adopted to empirically assess the three propositions. To address the differences between in‐house and contract lobbying sub‐groups on single categorical variables, we deploy basic cross tabulations, with chi‐square tests of association.

In order to explore the series of work experiences that our lobbyists accumulated across their careers, we use a combination of sequence and cluster analysis. As a method, sequence analysis has advantages over time‐series approaches, in that it accepts that individuals transition from one category of employment to another – the data are categorical – and that careers are measured across time in relative, not absolute, terms (Brzinsky‐Fay & Kohler, Reference Brzinsky‐Fay and Kohler2010; Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). This method is widely used in the study of political elites, in particular ministerial and legislative careers (see Jäckle, Reference Jäckle2016). There has been one single study using these tools in respect of lobbying (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). Here we further extend the use of this method in the analysis of lobbyists’ careers.

Sequence analysis starts by descriptively defining ‘states’ within careers sequences. We identify 12 possible states that an individual lobbyist may have held at a point in time. For each individual in our dataset, we code the state they held most recently, prior their current lobbying role [P1], and then each different role going back as far as we could find. Placed end to end, most recent role first, these series of progressions across states constitute the individual's career sequence. Using the TraMiner package in R (Gabadinho et al., Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Müller and Studer2011), we then calculate the distances across all our 650 individual sequences, assessing which lobbyists have accumulated most different or most similar series of career experiences. In our case, we utilize an ‘optimal matching’ (OM) approach to calculate this distance. Analysis of this kind operates by calculating the distances across pairs of sequences, where this distance is defined as the number of insertions and deletion of states within a sequence needed to transform one into another. We opt for OM given it is intuitive to understand, is the standard approach in the literature on elite careers, and is suitable for data with unequal sequence lengths, which we have (see Jäckle & Kerby, Reference Jäckle, Kerby, Best and Higley2019 for discussion). In a next step, we cluster these sequences in order to identify sets of career patterns that are most similar. Again, various clustering algorithms are available, but we use hierarchical clustering (using the Cluster package in R, Ward's method). This process simply aggregates those individual sequences that are least different together, until a defined number of groups is reached. As a last step, we change focus from the states within sequences to transitions between states. We look at which transitions between states are significantly associated with which clusters. This assists us in determining the relative importance of specific career roles in allocating a lobbyist to a given cluster.

In the final multivariate component of our analysis, and following similar approaches to ministerial careers (see Kerby & Snagovsky, Reference Kerby and Snagovsky2021), we deploy a binomial logistic regression model to estimate the effect of types of lobbying careers (identified in the sequence clustering process), on whether an individual is an in‐house or contract lobbyist (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien1988). This analysis helps us discern the extent to which one or other types of lobbying careers is associated with in‐house or contract lobbying roles.

Results

In this section we explore each proposition in turn.

Proposition 1 [Decisive?]: Direct political experience is the core experience among lobbyists?

The dominance of the revolving door thesis naturally encourages scholarly attention to direct political experience as a precursor to lobbying careers. But how common an experience is this?

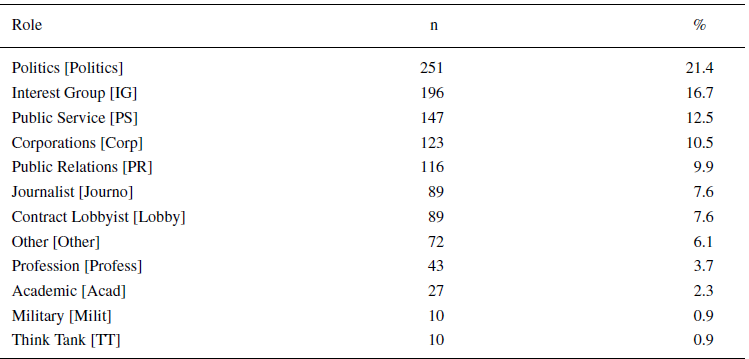

The frequency of all our different ‘states’ across the full careers of our 650 lobbyists is reported in Table 2. Some conclusions can be drawn simply on the basis of these data. First, Politics is the most frequent occupation ‘state’ across the dataset. In fact, 21 per cent (n = 220) of all roles in the dataset involved employment within Politics, with the figure being 12.5 per cent (n = 147) for Public Service. Journalism and Public Relations were well represented, with 7.6 per cent (n = 89) and 9.9 per cent (n = 116) of all roles being in these respective fields during their careers. By contrast, 16.7 per cent (n = 196) of the roles across all these careers were with an interest group and 7.6 per cent (n = 89) in a contract lobbying firm prior to their current roles.

Table 2. Roles within lobbyist careers, all

Note: Individuals can be counted in more than one role

State labels used in some diagrams and figures in [parentheses].

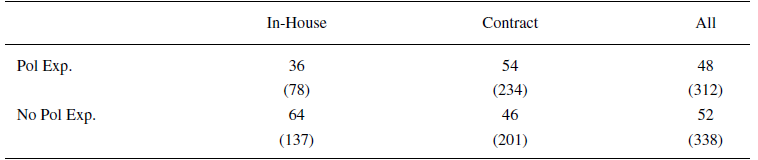

Consistent with the literature, we define ‘political experience’ as having been an elected MP, staffer or advisor to a MP, a party employee or having worked within the state or federal public service: this accords with combined PS and Politics ‘states’ in our data. We found that almost half of all lobbyists in our sample had such prior experience (Table 3, ‘All’ column). This is entirely consistent with the findings of previous US studies.

Table 3. Does political experience vary by lobbyist type?

Note: n = 650, individuals can only be included once in this table. Figures are column percentages with column frequencies in parenthesis.

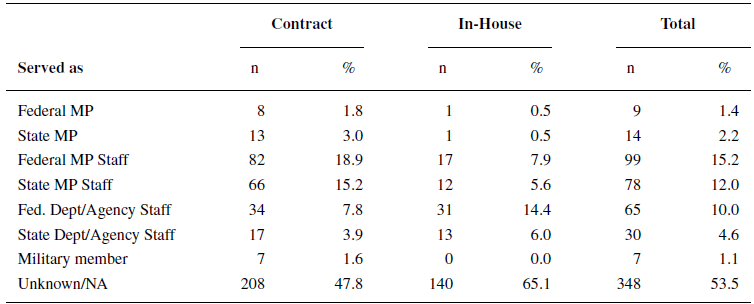

The precise prior role that an individual held when gaining direct political experience is salient. As recorded in Table 4 (‘Total’ column), we find that the largest proportion of those with political experience obtained this from roles as a staffer for elected politicians (in this case either federal or state members of parliament). A smaller, but still substantial proportion gained this experience from roles as a former state or federal public servant. This is notable simply because the journalistic take on the revolving door tends to pick cases of former legislators when generalising about the revolving door, however this is not the modal instance in our Australian data. In our population, a relatively small proportion were former federal or state MPs.

Table 4. Source of political experience, by current lobbying role

Note: If the individual held multiple government roles, we record the most recent role.

Proposition 2 [Divergent?]: Direct political experience is especially core in the careers of contract lobbyists?

While direct political experience is common among lobbyists, there is an expectation that this might be more so among contract lobbyists (LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017), while studies of in‐house lobbyists found few with political experience (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). Our data provide the chance to explore this proposition of divergence. We have 435 contract lobbyists and 215 in‐house lobbyists in our data. To get an initial sense of how crucial political experience is across these two groups, we refer back to frequencies in Table 3. It is apparent that many individuals across both sets of lobbyists do have political experience. Yet, there is variation between these two cohorts, with 36 per cent of in‐house lobbyists possessing political experience, compared to 54 per cent of contract lobbyists (x2(1, n = 650) = 16.99, p < 0.001).

As mentioned above, when we collected our data, we recorded the type of political role that those with political experience held (see Table 4). When we contrast in‐house and contract lobbyists, in general, we find that the former tended to gain experience from a role in the public service, while contract lobbyists tended to come via political staffing roles. Overall, only 3.6 per cent of all lobbyists had an elected political role. Yet, only two of these were in‐house lobbyists, the balance were contract lobbyists.

Proposition 3 [Diverse?]: Direct political experience is one of many core components of lobbyists’ careers.

What other experiences might be salient to employment as a lobbyist? To address this proposition, we turn to an analysis of lobbying career sequences. In our analysis, we (a) identify the full range of relevant career experiences that may lead to employment as a lobbyist, (b) determine if these ‘fall’ decisively into those with political experience or without (or if some other prior experience matters) and (c) identify if there is a clear difference between contract and in‐house lobbyists.

Exploring lobbying careers: Sequence analysis

The building blocks of lobbyist careers are sets of possible previous work roles. Each role which a lobbyist has held is referred to in sequence terms as a ‘state’. Building on past work on lobbyist backgrounds, we coded the employment backgrounds according to 12 possible states: Academic, Corporation, Interest Groups, Journalist, Lobby Firm, Politics, PR firm, Profession, Public Sector, Think Tank, Military and Other. Table 2 reported the frequencies across our full dataset.

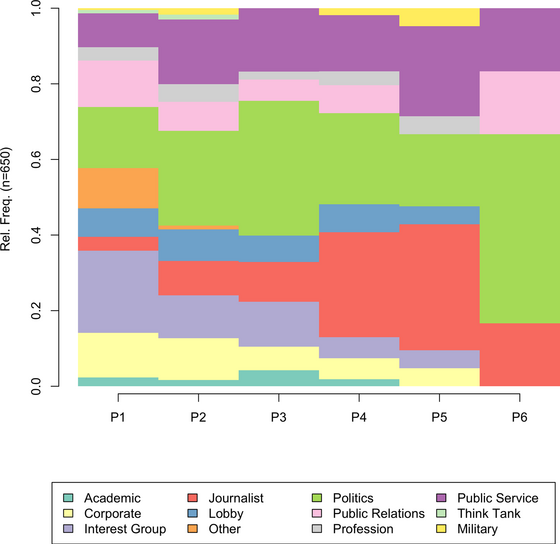

We now place these ‘states’ into career sequences. These sequences are ordered with P1 the most recent previous role held prior to their present employment (as of 2018, when the data was collected) and P7 the position they were in farthest in time for their present employment. Figure 1 reports the distribution of states that our commercial lobbyists held at each step in their careers: each step can be read as a stacked bar chart (see the Supporting Information Appendix Table A.1 for frequency of states underlying this figure).

Figure 1. State distribution plot, all lobbyists [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Compared to the analysis of European in‐house corporate lobbyists, where Coen and Vannoni (Reference Coen and Vannoni2016) found individuals predominantly recruited from within industry, we can see a lot of diversity in job experience across careers. The relative prominence of prior work within government – including Public Service and Politics in our code scheme – seems at face value to fit more closely with proposition 1, where analysis of revolving door lobbying notes the swift movement from government service to lobbying, and particularly contract or commercial lobbying (Lazarus et al, Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016; LaPira & Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017). However, there is also evidence consistent with proposition 3, given the descriptive finding that lobbyists in fact have varied and diverse careers, and accumulate potentially relevant experiences from a range of roles well beyond government work.

Types of careers

We proceed to explore variations between the sequences of individual lobbyists, to detect groups of most similar career patterns. To do so, we calculate the distance matrix across our 650 individual career sequences and identify representative career sequences through a clustering algorithm within the TraMiner package (see methods section). We settled on four ideal‐type lobbying career paths in our clustering analysis. A range of criteria can be applied to assess the internal validity of the optimal number of clusters (Milligan & Cooper, Reference Milligan and Cooper1985). Several such criteria suitable for categorical data, including average silhouette width (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, Reference Kaufman and Rousseeuw1990), and the G2 & G3 internal cluster quality indexes (Hubert & Arabie, Reference Hubert and Arabie1985), are somewhat ambiguous, and suggest between three and five clusters.Footnote 9 Yet, the four‐cluster solution provides a parsimonious interpretation of groupings, and is supported by a declining slope on all measures (except for Hubert's C where quality is denoted by rising score). The four‐cluster solution is therefore carried onwards for further analysis.

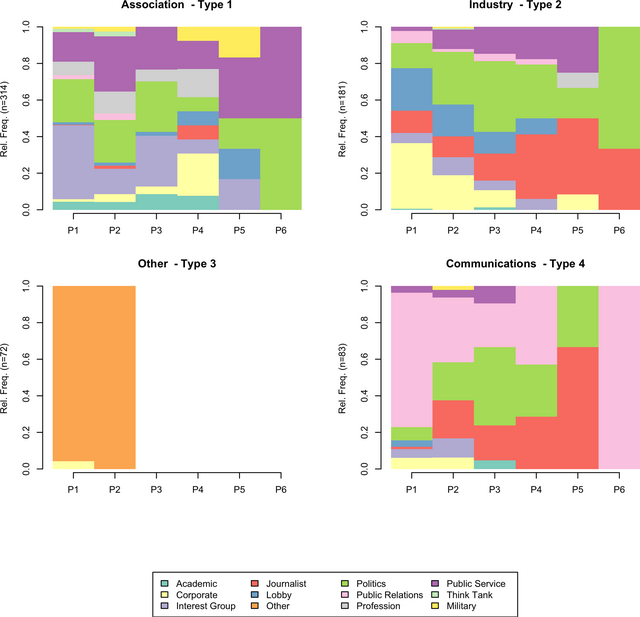

Recall, revolving‐door theory, based on the US literature, anticipates that we would find a clear dominant type with a decisive pathway forged by political experiences (states of ‘Politics’ or ‘Public Service’). By contrast, a divergent account – with a sliding door in operation – anticipates contract lobbyists dominated by political experience while in‐house lobbyists have careers drawing on commercial or associational experiences. Finally, the alternative view has it that lobbyists accumulate diverse skill sets, of which direct political experience is only a constituent part.

Our analysis in Figure 2 confirms aspects of each proposition. Type 1 (‘Association’), the largest single cluster (n = 314), consists of individuals who have experience in interest groups, in addition to the public service and politics. By contrast Type 2 (‘Industry’) are strongly influenced by previous work within the corporate sector, public relations firms or contract lobbying firms. Type 4 (‘Communications’) is interesting in that it is a cohort whose experience is strongly shaped by journalism and public relations roles, and the government experience is heavily shaped by political roles, but not those within the public sector. This makes a great deal of sense in that a lot of contract lobbying firms do engage in issues management and strategic communications. This is a different kind of lobbying than the direct lobbying through contacts with government officials. Type 3 is a pure outsider category, people who come into lobbying with no apparent experience.

Figure 2. State distribution plots, clusters [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Before continuing, it is important to note a few related points. First, direct political experience – which is how the literature determines whether an individual constitutes a revolver – is common across three of our ideal‐type career pathways (denoted by threads of ‘Politics’ or ‘Public Service’ states in career sequences). It is undeniable that almost half of lobbyists in our study have government experience. Second, it is apparent that there is no single type of lobbyist, but rather several broad groupings of lobbyists who bring a different skill set to the role. This underlines that ‘valuable’ knowledge can be accrued about policy and politics without necessarily being employed as a staffer, MP or even within a government agency or department.

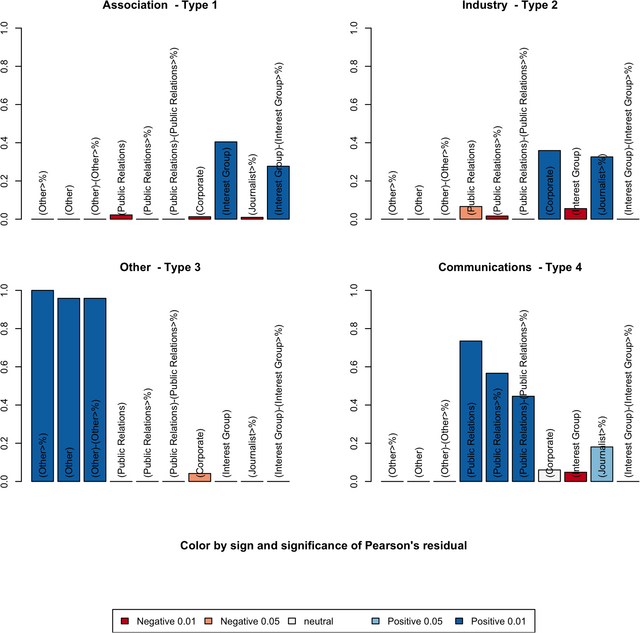

Further information to assist in interpreting this clustering can be gained by examining the transitions and states that are most discriminating between clusters. Figure 3 reports those 10 transitions (or states) that discriminate most strongly between each of our four clusters (see Studer, Reference Studer2013)Footnote 10. The labels within the plots refer to each state (see methods section)Footnote 11. What is immediately obvious is that the states Public Service and Politics which are associated with direct political experience are not on these plotsFootnote 12. Their presence and/or absence within each group/cluster does not readily discriminate between themFootnote 13. This evidence alone provides important clarification to proposition 1: namely, that in a market for lobbyists, political experience is not a key differentiator. As such, for those lobbyists who are not coming from a political background, they are likely to substitute that experience for those within corporations or within journalism or public relations. By contrast, political experience – whether within the Public Service or Politics – is typically combined with roles within Interest Groups among a large number of lobbyists within the ‘Association’ type. That ‘Industry’ (Type 2) lobbyists, have a strong association with corporate and contract lobbying roles, but a negative association with those states linked to political experience (Politics and PS) further supports European work which hypothesised that those who worked in corporate fields tended not to then have worked in government (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016). We can see that the Public Relations (‘PR’) state, and transitions from Public Relations and Journalism, are positively associated with ‘Communications’ (Type 4) lobbyists. Interestingly we see little role for political experience in this type of lobbyist, suggesting that those lobbyists with non‐political backgrounds are recruited from journalism and PR, for communications and issues‐management roles. Our ‘Other’ (Type 3), unsurprisingly have strong associations with all states and transitions connected to ‘Other’.

Figure 3. Discriminating transitions (top 10), by lobbyist type [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

If we now know that experiences that define types of lobbying careers are not demarcated by political experience, do we find that lobbying careers differ for those engaged in contract versus in‐house lobbying roles? Are they still two different worlds? Coen and Vannoni (Reference Coen and Vannoni2016) speculated that their finding on the infrequent revolving door among corporate in‐house lobbyists, promoted the image of a sliding door. And, LaPira and Thomas (Reference LaPira and Thomas2014) find that contract lobbyists are the most likely to be revolving door lobbyists. To answer this question, we move to a multivariate analysis, where we regress employment as in‐house or contract lobbyists, against these clusters as our key independent variable.

Is experience associated with contract versus in‐house roles?

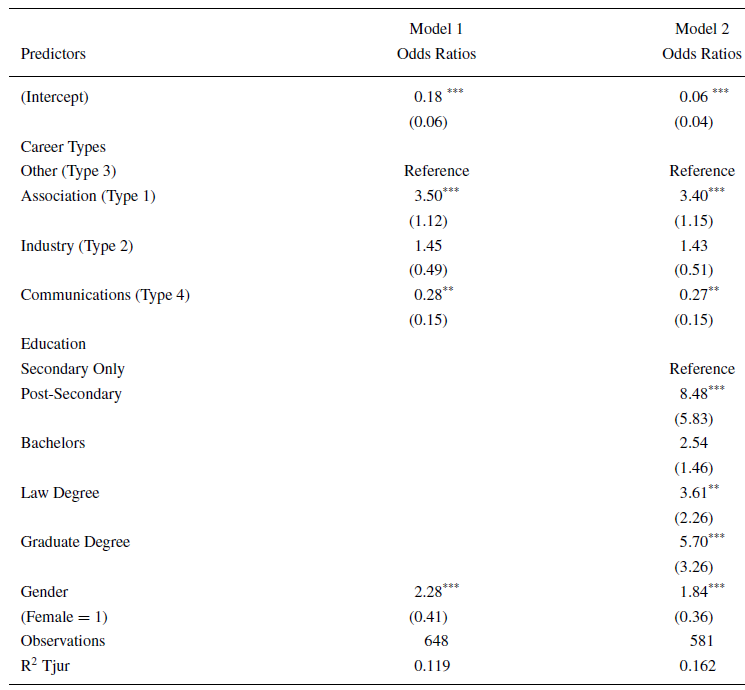

To probe differences amongst our two different types of lobbyists we deploy a binomial logistic regression, with contract versus in‐house lobbyist as our dichotomous dependent variable (see O'Brien, Reference O'Brien1988 for a discussion of its application to this kind of problem). We estimate two separate models given that we have some missing data for education (see Table 5).

Table 5. Logistic regression: Career types and lobbying employment (in‐house vs contract)

Note: Dependent variable is Contract lobbyist (0) In‐house lobbyist (1).

The results of our multivariate analysis show that some types of lobbyist careers are strongly and significantly associated with in‐house (Type 1) and others with contract roles (Type 4). This provides support for proposition 2: there are some types of lobbyists suited to one or other roles, and they differ in terms of experiences. Yet, our evidence suggests that this is not a simple or straightforward product of the role of government experience. It is the lobbyists with ‘Association’ type careers that are strongly and positively associated with in‐house roles. By contrast, those with ‘Communications’ type careers are significantly associated with contract lobbying roles. As our clustering analysis demonstrated, while many individuals in these two lobbyist types do possess political experience, this is one among many roles held, and is not considered to be significant in distinguishing their careers from other types. This finding confirms that the contract lobbying industry, at least in Australia (but we have little reason to expect it to vary wildly in other jurisdictions), values communications roles, as do their clients. Finally, we find evidence that lobbyists with what we call ‘Industry’ type careers have a positive association with working via in‐house roles, however we find this is not at significant levels.

While not a key focus of this paper, our model also provides evidence, outside of the US case, that in‐house lobbyists tend to be more highly educated, and a workforce with more women active, than contract lobbyists (see LaPira et al., Reference LaPira, Marchetti and Thomas2020, for similar findings in the US context).

Discussion/Conclusions

In their landmark study of Washington politics, Heinz et al. (Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993) interviewed over 800 lobbyists, the vast majority of whom cited working in government, developing knowledge of government processes and subject matter expertise as important. Undoubtedly, political experience matters for a would‐be lobbyist. Our study asked a related but somewhat different question: What roles across the full career span of lobbyists differentiates one from their peers? We tested three basic propositions in the literature: is political experience decisive in all lobbying careers? Is it more divergent, in that it is important for contract but not in‐house lobbyists’ careers? Or, is it simply that the careers of lobbyists are very diverse, and political experience is not actually the key differentiating role?

We found that while political experience was common to over half of all our lobbyists, across the four types of career sequences it was not one of the defining experiences differentiating one from the other. Other experiences turned out to be key differentiators. Experiences in journalism, public relations, interest groups and within corporate Australia, all helped parse out types of lobbying careers. While we do not have direct evidence that employers privilege these specific roles as important when hiring (see more below), the literature on professional development needs amongst lobbyists and the adverts they post suggests they are (Althaus, Reference Althaus2015). We do find differences in the skill sets of in‐house and contract lobbyists (our so‐called divergent proposition), but, again, this is not determined by different levels of political experience. In the terms set out in the literature, we find both a revolving and sliding door in operation. In terms of a revolving door, we see that most lobbyists do have some kind of political experience. We also see that distinct types of lobbyists emerge, with a sliding door working to sort individuals into career pathways, defined by a focus in corporate lobbying, associational contexts or in the political communications industry. The compatibility of these two mechanisms is simply a function of the ubiquity of political experience among Australian lobbyists. Like the US evidence, Australian lobbyists gain contacts and expertise from work within government, while like the EU evidence, they forge distinctive career pathways in specific fields. Our chief insight from the sequence analysis is that, unlike the EU evidence, Australian lobbyists do not find political experience a limit on subsequent work in other fields. As our multiple doors account suggests, lobbyists seem to develop both contacts and expertise from working both in government and out of government as part of career development. While we do not test it here, this is consistent with the Australian lobbying context – policymakers and employers of lobbyists – requiring both expertise and contacts in their advocacy workforce. Further, it supports the small but growing literature on the desired attributes of lobbyists (see Holyoke et al., Reference Holyoke, Brown and LaPira2015).

These findings have important implications for students of lobbying careers, and specifically the ever‐expanding literature on the revolving door. Most obviously, our work points out the limits of a singular focus on direct political experience as decisive in political careers. We agree with the literature that it is a very common feature in lobbying careers, yet it does not differentiate when we examine all relevant career experiences individuals accrue. This finding should encourage scholars to conceptualize the value that lobbyists bring to their employers in terms of lobbying careers through which they accrue a broad range of skills and experiences, and not in narrow terms of leveraging direct political experience. While tools like sequence analysis have their limits, as we come to in a moment, they are well placed to start to address the diversity of lobbying careers.

A key contribution of this paper is its empirical focus beyond the usual US case. This does, then, however, raise the issue of generalising from the Australian case. Certainly, comparative work will help to further refine the propositions tested here. We do not see any clear reason why these might not travel well beyond Australia, yet there are some specifics of the Australian political system which might create variations in the findings we report here. Adopting the pluralist and corporatist distinctions common in organised interest studies, we might simply argue that Australia's broadly pluralist system would mean these findings hold in other most similar systems, such as the United Kingdom and the United States. By contrast, we could speculate that corporatist systems, given their traditional focus on insider group intermediation, will feature fewer staff with public‐facing or outsider aligned capabilities – such as Public Relations and Journalism – and more insider aligned skills – such as from the Public Service and Interest Groups. Yet, the apparent rise of so‐called ‘lobbyism’ in these systems might point to different tendencies, suggesting that over time such systems should more closely approximate those we report here (and US colleagues report elsewhere) (Öberg et al, Reference Öberg, Svensson, Christiansen, Nørgaard and Rommetvedt2011). Relatedly, the Australian media system may play a role in explaining the place of journalism, communications and public relations experience in lobbying careers. Australia is a liberal media system like Canada and the United Kingdom (Hallin & Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004). Yet its level of media concentration is comparatively high, which may lead to a heightened degree of partisanship in gaining media attention (see Tiffen, Reference Tiffen2015). This may create stronger interlocks between media experience and partisan or political roles. Ultimately these are empirical questions that we hope scholars will take up in future comparative efforts.

Like all work, there are some limitations in what we present here, that future work might improve on, develop and elaborate. Like Coen and Vannoni (Reference Coen and Vannoni2016) we find that the sequence data we have assembled is important for scholars of political influence, lobbying and advocacy to embrace. Not least, because it provides a more accurate appreciation of the diverse, yet relevant, experiences that lobbyists accrue. Yet, we were not able to provide data that allowed us to address important dimensions of tenure and timing. That is, we cannot say with our data how long someone was in a particular role – their tenure – nor the objective timing of a switch from one role to another – timing. Yet, constructing data that can capture these is tough, especially given the reliance on data from self‐reported forums such as LinkedIn and corporate websites. To the extent that scholars can develop reliable time‐stamped data on careers of lobbyists, we can move forward to incorporate these important dimensions.

The issue of career success is again something we have not said anything about, but which future work could certainly take forward. While work on legislative and judicial careers, for instance, can justifiably assess a movement from a lower to higher court, or from the back bench to a senior cabinet position, as career progression, there is less clarity on what that might mean in the world of lobbying. Inspiration could come from work that has been attempted with European corporate lobbyists (see Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2020), where movement within a given firm is the benchmark for progression. However, how this might map on the diverse kinds of careers we have reported on here remains challenging.

Our theoretical approach assumes that employers of lobbyists appraise the experiences of would‐be lobbyists and hire accordingly. Thus, our finding that political experience is a quite common, but not a discriminating, component of lobbyists careers, suggests that employers value a broad skill set that can be acquired elsewhere, say from corporate work, communications roles and time spent in journalism. This is a novel finding, and one that prompts further questions. It will not, however, satisfy the reasonable question as to what precisely this variation in experiences provides for an employer? In common with the well‐established scholarship of career advancement among legislators, we simply do not know why they were selected (or de‐selected): we assume it pertains to the apparent value of the accumulated experiences of the individual (whether that be information, contacts or notoriety/reputation)Footnote 14.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank David Coen and Matiai Vannoni for fielding our multiple queries about their earlier work on which this paper develops. An earlier version of this paper benefited from the detailed comments of Keith Dowding and Herschel Thomas. The research reported here was supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant (DP: DP210101121) awarded to Keith Dowding, Darren Halpin, Matthew Kerby & Marija Taflaga. We appreciate the constructive comments of the EJPR reviewers and Editorial team on this manuscript.

Open access publishing facilitated by Australian National University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Australian National University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. State Frequency Table (for Figure 1)

Table A2. Summary Statistics, Model Variables

Table A3: Robustness Test for Seniority, Multivariate Model

Figure A1: Summary of alternative cut‐off rules (Ward's method)

Codebook for Variables