1. Introduction

Playing a central role in the emergence of the international human rights regime, the language of respect for “human dignity” has proven to have widespread appeal as a way of expressing the idea of the unconditional value of each human being and a sense of common humanity. Recent years have witnessed the increasing prevalence of various “dignity movements.” In turn, various leaders and organizations routinely invoke dignity as a core principle around which they are organized. We are, in short, living in an “age of dignity” (Dupré, Reference Dupré2016). Proponents of this trend contend that appeals to dignity will, in fact, work to generate greater public support for improving the rights and treatment of vulnerable or stigmatized groups.

Empirical research on the impact of appeals to human dignity is still in its infancy. Recent studies have shown that people care deeply about whether they are treated with dignity (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Naidu and Reich2022), and that their health and well-being decline if they perceive their dignity being ignored (Hojman and Miranda, Reference Hojman and Miranda2018; Andersson and Hitlin, Reference Andersson and Hitlin2022). Our focus, however, is whether appeals to the value of dignity effectively generate greater public support for the rights of others, particularly at-risk groups, as proponents assume.

The assumption that appeals to dignity will operate to challenge status hierarchies is not self-evident. Throughout most of Western history, dating back to the Romans, the idea of dignity was itself steeply hierarchical. Dignity was tied to particular ranks or offices or activities which were owed distinctive respect. This “aristocratic” conception of dignity has increasingly been challenged and displaced by a more universalistic conception grounded simply in our common humanity (Rosen, Reference Rosen2012; Waldron, Reference Waldron2012; Kateb, Reference Kateb2014). However, the literature on “deservingness” suggests there may be significant limits to this universalistic conception of dignity. When making political judgments, ordinary citizens focus not just on our common humanity, but on “who deserves what” (Gilens, Reference Gilens2009, 2), and view certain groups as deserving their disadvantage (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000) or needing to “earn” help from the government (van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Proponents of dignity appeals hope that priming ideas of common humanity can preempt potentially harsh judgments about the deservingness of various groups. Our research aims to test this assumption.

Consistent with preregistered hypotheses,Footnote 1 we find that appeals to dignity can be effective in an online environment, but we also find that the effects vary with perceptions of deservingness. While appeals to dignity increase public support for groups seen as deserving, they are less effective for those groups seen as undeserving and may indeed generate backlash. This suggests that human dignity does not operate in a stand-alone fashion, and that an effective politics of dignity may need to address wider issues about the plural sources of (dis)respect and (mis)recognition in modern societies (Lamont, Reference Lamont2023).

2. Research design

We tested the impact of promoting dignity claims for vulnerable groups by observing citizen reactions to such appeals in a natural online setting, conducting a field experiment in January of 2023 that randomly exposed individuals to different advertisements associated with particular stigmatized/vulnerable categories of persons on Facebook. In all ads, we prompted users with an opportunity to “like” the ad from their internet-connected device—which we interpret as a behavioral outcome indicating a desire to publicly recognize the featured group. While a “like” may not be financially costly, it is a nontrivial action since users are aware that their Facebook friends can view and comment on their support.

We used Facebook as a research site for our field experiment for two reasons. Facebook has tremendous reach, with over 7 in 10 American adults reporting ever using Facebook (Gramlich, Reference Gramlich2021). This provides a natural setting at scale to understand the value of dignity appeals. Evaluating the effectiveness of a dignity frame on Facebook engagement also establishes high mundane realism for our experiment, as our ad campaign closely resembles how organizations reach potential supporters. Facebook is an important source of advertising for organizations, and reacting to, commenting on, and sharing a post are important advertising strategies through electronic word-of-mouth (Jalilvand et al., Reference Jalilvand, Esfahani and Samiei2011), which studies have shown converts to spending and other salient off-line behaviors (Grahl et al., Reference Grahl, Hinz, Rothlauf, Abdel-Karim and Mihale-Wilson2023).

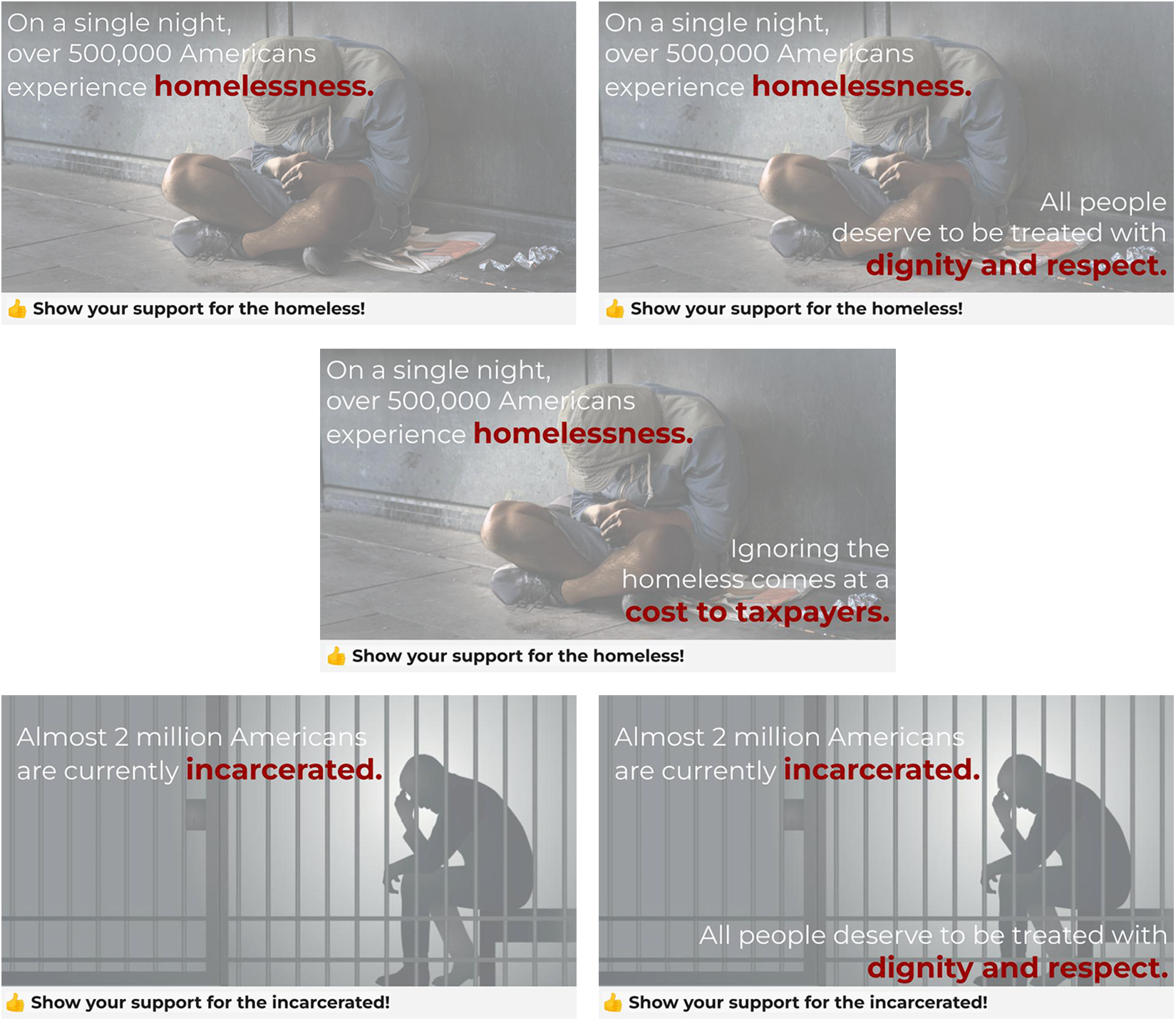

Using Facebook’s A/B test function, we ran an experiment in which we randomly assigned which of the five ads displayed in Figure 1 would be seen by individual users. We varied the stigmatized group featured in the ad—either people experiencing homelessness or those incarcerated. In pretesting, we found that a majority of respondents perceived those incarcerated to be blameworthy for their position; by contrast, beliefs regarding the blameworthiness of people experiencing homelessness were much more varied and typical of other vulnerable categories, such as the poor and immigrants.Footnote 2 Varying these groups allows us to test whether the effectiveness of dignity appeals varies according to how they might be perceived as blameworthy for their vulnerable condition. For all ads, images of a lone individual intentionally did not feature faces to avoid respondents’ reactions to race, gender, perceived attractiveness, friendliness, sense of despair, etc. All the ads included an informational statement about the magnitude of the problem.

Figure 1. Set of ad campaign treatments for vulnerable groups. In order it shows the homelessness:control, homelessness:dignity, homelessness:economic, incarcerated:control, and incarcerated:dignity ads.

Experimental treatments were presented in the form of overlaid text. Specifically, the dignity treatment added the text, “all people deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.” Only in the case of homelessness did we also assign a treatment condition that involved making an appeal to economic self-interest—“ignoring the homeless comes at a cost to taxpayers”—which provided an additional basis for estimating the effect of the dignity appeal.

To ensure that our sample was geographically diverse across the United States, we ran a separate campaign in each of the 48 contiguous United States. The platform randomly exposed over 90,000 American, adult users of Facebook to one of the five different ad types that appeared in their NewsFeed, interspersed with other sponsored posts and posts from their Facebook friends.Footnote 3 At the bottom of each advertisement, a text box invited viewers to “Like” the ad to show their support for people experiencing homelessness or those incarcerated. Viewers could express other reactions (including Love, Care, Haha, Wow, Sad, and Angry), comment on, or share the post. We focus on positive reactions (Like, Love, and Care) because our study’s motivation concerns how dignity appeals might lead to more supportive engagement. Moreover, negative reactions are more difficult to interpret. For example, an angry reaction could mean that the respondent is angry at the problem or at the message contained in the ad.

The Facebook platform automatically generated aggregate results from each campaign indicating engagement by treatment arm, including number of reactions (in total and by reaction type), the number of unique users who saw the ad (reach), and the number of views of the ad (impressions). We used these data to generate a dataset at the level of anonymous individual-level users for each outcome, recording which ad version an individual saw, their reaction, and the state associated with each user.

3. Results

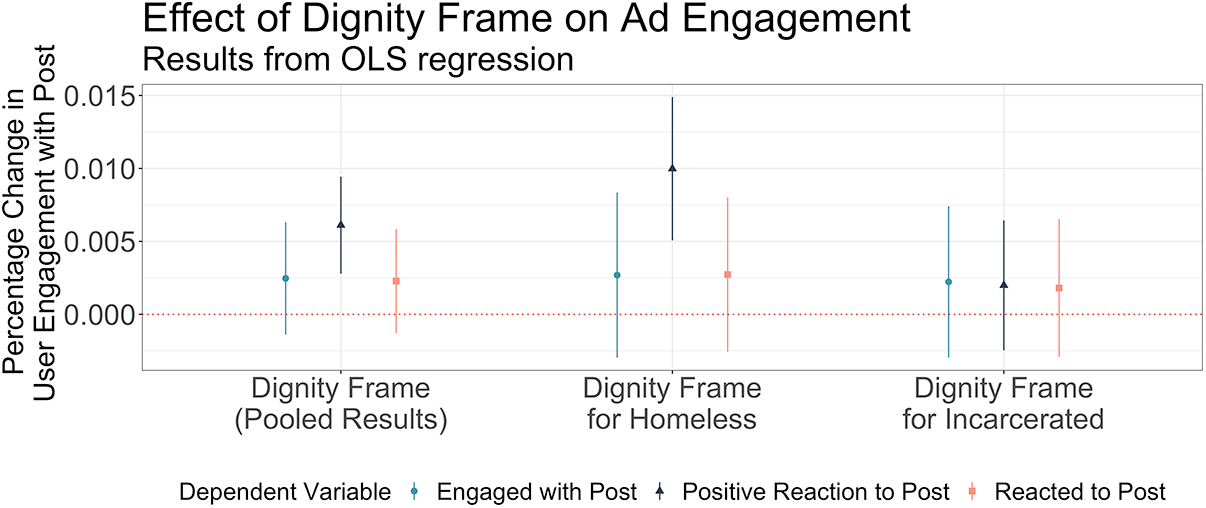

In our pooled analysis of the 48 campaigns, we find support for our key hypotheses. The results depicted in Figure 2 demonstrate that reminders of human dignity can increase support for at least some vulnerable groups.

We estimated the effects of dignity relative to control frames on online behaviors using an ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression that controlled for the vulnerable group mentioned in the ad. We explored the dignity frame’s effect on any engagement with the ad (reactions, shares, or comments), any reaction to the ad, and just positive reactions. We focus on these three outcomes because they allow us to test whether the dignity appeal increases all engagement or specifically positive engagement, an important theoretical distinction that our hypotheses address.Footnote 4

Analyses presented on the left of Figure 2 demonstrate that the dignity frame caused an increase in user responses, but only in terms of positive reactions. Overall, 6.5% of the sample had any reaction, and 5.5% had a positive reaction, with “likes” being the dominant reaction. The estimated 0.5 percentage point increase in positive reactions among those in the dignity treatment arm relative to the information-only treatment represents a marked increase in positive engagement. In substantive terms, this amounts to a 9% increase in positive reactions for the same ad spend due to minor changes in the message text. Other evaluations of online or text-based advertising find effect sizes of 0.2–0.3 percentage points (Linos et al., Reference Linos, Jakli and Carlson2021) or click rate effect sizes of 0.003 on priority outcomes (Adida et al., Reference Adida, Adeline, Prather and Williamson2021). Moreover, as detailed in Appendix A8, the effect of dignity remains positive and significant even when compared to an appeal on the economic cost of inaction, amplifying the conclusion that this specific appeal was consequential.

Figure 2. Results from an ordinary least squares regression that compares the effect of the dignity frame to the information frame on engagement with the post. The pooled results frame compares the effect of the dignity frame to that of the information frame while controlling for the vulnerable group. The remaining results compare the effect of the dignity frame to that of the information frame by vulnerable group. Engaging with the post means that the Facebook user reacted to, commented on, or shared the post. Reaction indicates that the user liked, loved, or responded with one of the other reaction options at the bottom of the post. A positive reaction indicates that the Facebook user liked, loved, or cared about the post. Effects also presented in Table A2.

Our second set of analyses sought to recover evidence concerning whether the effect of the dignity frame would be less powerful when used in the context of the incarcerated because of likely differences in perceived blameworthiness. We used an OLS regression specification that interacted the vulnerable group and the dignity frame treatment to assess this hypothesis and again excluded cases from those assigned to the economic appeal condition.

Figure 2 lends credibility to the hypothesis. We find that the dignity frame leads to a 1 percentage point increase in positive engagement when the ad features a homeless person, but an increase of only 0.2 percentage points (and not statistically significant at conventional levels) when the ad featured someone incarcerated. While a limitation of our research design is that we do not know the individual-level perceptions of blameworthiness on the part of our subjects, these findings suggest the moderating effect of such perceptions.Footnote 5

Although not preregistered, we further explored whether blameworthiness moderates the effect of dignity frames by harvesting 475 comments associated with the treatment and control ads (analysis presented in the appendix). We analyzed their content and tone, including whether the vulnerable group was described as “blameworthy” for their situation and whether the commenter had a positive or negative outlook toward the group.Footnote 6

These analyses are largely consistent with the abovementioned findings. As depicted in Table A5, we find that the dignity frame increases positive or respectful comments for the homeless but also increases the number of blameworthy and negative comments for the incarcerated. While only suggestive, this additional discursive evidence lends credence to the idea that dignity appeals vary in their effectiveness by the perceived blameworthiness of the vulnerable group in question and, moreover, can have a backlash effect for groups seen as blameworthy.

4. Conclusion

We have considered how the idea of human dignity might resonate beyond philosophical debates and into the ordinary human experience. Our empirical study in the mundane-but-ubiquitous online social media environment offered a powerful test of this proposition and ultimately found some limited support for its potential impact: dignity appeals lead citizens to pay greater attention to some of those who might otherwise be seen as unworthy or invisible, at least in terms of social media engagement. However, we also found substantial differences in terms of citizen reactions to dignity appeals by group, and moreover, descriptively documented its potential backlash effect for groups deemed more blameworthy.

These analyses suggest the need for future research exploring how dignity appeals work, including with respect to other vulnerable groups and in other countries. Can dignity appeals galvanize more costly (and potentially more impactful) private and/or political action including donations or activism? And, what mechanisms actually drive the effectiveness of dignity appeals as they relate to other common appeals, such as human rights? While there is much still to explore, our results suggest that dignity appeals may have an important role to play in struggles for a more inclusive society.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10022. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/U4JCHB.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments and feedback from participants in the Political Experiments Research Lab and the Global Diversity Lab at MIT; the Boundaries, Membership and Belonging program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), and to three anonymous reviewers and the editor of Political Science Research & Methods. Manasi Rao provided valuable research assistance.

Funding statement

This research was funded with a Catalyst Grant from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR).

Competing interests

None.