Introduction

Long-term studies of the symptomatic outcomes provide evidence that between one-third and one-half of patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) achieve symptomatic remission (Lally et al., Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Stubbs, Cullinane, Murphy, Gaughran and Murray2017; Peralta et al., Reference Peralta, García de Jalón, Moreno-Izco, Peralta, Janda and Sánchez-Torres2022), even considering patients from non-Western countries (Alem et al., Reference Alem, Kebede, Fekadu, Shibre, Fekadu, Beyero and Kullgren2009; Ran et al., Reference Ran, Weng, Chan, Chen, Tang, Lin and Xiang2015). Early intervention services (EIS) for patients with FEP produce better short- and medium-term outcomes than treatment as usual (TAU) (García de Jalón et al., Reference García de Jalón, Ariz, Aquerreta, Aranguren, Gutierrez, Corrales and Cuesta2023) and increase the likelihood of milder impairments and better functioning after 10 years of follow-up (Hegelstad et al., Reference Hegelstad, Larsen, Auestad, Evensen, Haahr, Joa and McGlashan2012). However, caution is required when interpreting these results given that the longest follow-up comparison study (20 years) to date reported no significant differences between patients with FEP after receiving 2 years of EIS or TAU (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Starzer, Nilsson, Hjorthøj, Albert and Nordentoft2023). One possible explanation for the differences across studies is the use of dissimilar definitions for clinical remission and recovery (Åsbø et al., Reference Åsbø, Ueland, Haatveit, Bjella, Flaaten, Wold and Simonsen2022).

There is strong evidence that the etiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD) involves numerous environmental and genetic factors as well as their interactions (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir and Fusar-Poli2018; Trubetskoy et al., Reference Trubetskoy, Pardiñas, Qi, Panagiotaropoulou, Awasthi and Bigdeli2022). Having first-degree relatives with a history of schizophrenia is one of the most significant risk factors for developing this disorder (Mortensen et al., Reference Mortensen, Pedersen, Westergaard, Wohlfahrt, Ewald, Mors and Melbye1999; Sullivan, Kendler, & Neale, Reference Sullivan, Kendler and Neale2003). Nevertheless, the low lifetime risk of SSD (<1%; Lichtenstein et al. (Reference Lichtenstein, Yip, Björk, Pawitan, Cannon, Sullivan and Hultman2009)) indicates that the vast majority of schizophrenia cases (>95%) can be considered sporadic because they lack an immediate family history of schizophrenia (FH-Sz) (Yang, Visscher, & Wray, Reference Yang, Visscher and Wray2010). A population-based study conducted in Denmark using health electronic records examined the extent to which the risk of schizophrenia was related to the mutual effects of the polygenic risk score (PRS), parental socioeconomic status, and a family history of psychiatric disorders in a sample of 866 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (Agerbo et al., Reference Agerbo, Sullivan, Vilhjálmsson, Pedersen, Mors, Børglum and Mortensen2015). They found that a FH-Sz has only a limited impact on the risk of schizophrenia among individuals with a low PRS, but the impact seems to increase rapidly as liability increases.

Numerous environmental factors have been associated with the development of schizophrenia, expanding their influence through a complex spatiotemporal matrix of competing factors (Brasso et al., Reference Brasso, Giordano, Badino, Bellino, Bozzatello, Montemagni and Rocca2021). The level of exposure to environmental factors can range from macro- to meso- and micro-levels (from general socioeconomic conditions to neighborhood and household conditions) (Pries et al., Reference Pries, Moore, Visoki, Sotelo, Barzilay and Guloksuz2022), and their potential intervention occurs at different times from illness onset (from distal and intermediate temporal factors to proximal ones) (Peralta et al., Reference Peralta, García de Jalón, Moreno-Izco, Peralta, Janda and Sánchez-Torres2022). An environmental risk score for schizophrenia (ERS-Sz) provides a better view of environmental vulnerability to schizophrenia. The ERS-Sz score was originally developed by Vassos et al. (Reference Vassos, Sham, Kempton, Trotta, Stilo, Gayer-Anderson and Morgan2020) by searching for the environmental risk factors with the largest effect size associated to schizophrenia. These risk factors were obtained from well-conducted meta-analysis of available evidence. As the effect sizes for risk factors were taken from separate meta-analyses, the calculation of the ESR-SZ was based on the assumption that the risk factors were uncorrelated (Pries, Erzin, Rutten, van Os, & Guloksuz, Reference Pries, Erzin, Rutten, van Os and Guloksuz2021; Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Sham, Kempton, Trotta, Stilo, Gayer-Anderson and Morgan2020), despite the fact that interdependence of exposures is the rule rather than the exception (Guloksuz et al., Reference Guloksuz, Rutten, Pries, Ten Have, de Graaf, van Dorsselaer and Ioannidis2018). Indeed, they assumed as a limitation of their ESR-SZ the problem of the intercorrelations between exposures (Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Sham, Kempton, Trotta, Stilo, Gayer-Anderson and Morgan2020). The ERS-Sz is a measure of the liability to illness in non-affected populations, though it also may influence the prognosis and outcomes of psychotic disorders (Erzin et al., Reference Erzin, Pries, van Os, Fusar-Poli, Delespaul, Kenis and Guloksuz2021, Reference Erzin, Pries, Dimitrakopoulos, Ralli, Xenaki, Soldatos and Stefanis2023).

Most of the studies conducted in patients with psychosis have used patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as the main health outcomes; physicians translate these PROMs to symptomatic remission based on standardized scales. However, patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) provide new insights into personal recovery and are increasingly being used in research, clinical care, and policymaking. In this regard, researchers have advocated using several domains instead of unidimensional measures to better capture the various outcomes of patients with FEP (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, O'Donoghue, Thompson, Gleeson, Bendall, Gonzalez-Blanch and McGorry2016; Cowan, Lundin, Moe, & Breitborde, Reference Cowan, Lundin, Moe and Breitborde2023; Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Sánchez-Torres, Moreno-Izco, García de Jalón, Gil-Berrozpe, Zarzuela and Zandio2022; Santesteban-Echarri et al., Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, González-Blanch, McGorry, Gleeson and Alvarez-Jimenez2017).

We aimed to ascertain the role of the individual effects of a FH-Sz, the ERS-Sz, and their joint effects over the 2-year course of non-affective first-episode psychosis (NAFEP). We hypothesize that FH-Sz and ERS-Sz interact to influence the 2-year outcomes on symptomatic remission, psychosocial functioning, and personal recovery.

Material and methods

The sample for this study was collected from the Programa de Primeros Episodios de Psicosis de Navarra (PEPsNa). This EIS for patients with NAFEP is based on adaptation of the NAVIGATE programme (https://navigateconsultants.org/index.html). Patients entering PEPsNa were drawn from an epidemiological catchment area comprising 660 000 inhabitants (Navarra, Spain).

The inclusion criteria were: (a) residence in the catchment area; (b) age between 15 and 55 years; (c) NAFEP diagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5) criteria (F20–F29) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2014); (d) no previous treatment with antipsychotic drugs; (e) provision of informed written consent to participate in PEPsNa; and (f) finished PEPsNa in December 2022. The exclusion criteria were: (a) psychosis exclusively related to illicit drugs, medications, or medical conditions; and (b) intelligence quotient (IQ) < 70.

The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) semi-structured interview (Andreasen, Flaum, & Arndt, Reference Andreasen, Flaum and Arndt1992) was used during the admission of the acute episode and follow-up of patients. The CASH enables clinicians to gather extensive data concerning current and past signs and symptoms, premorbid functioning, cognitive functioning, sociodemographic status, treatment, and course of an illness. It includes the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).

Outcome measures: symptomatic remission, functional recovery, and personal recovery

The three outcome measures were assessed at the time of discharge from PEPsNa (i.e. after 2 years of follow-up). Symptomatic remission was based on the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group (RSWG) definition (Andreasen et al., Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger2005; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chan, Chen, Hui, Wong, Chan and Chen2013). According to these criteria, all eight SAPS and SANS symptom global ratings must be categorized as having mild or less severe intensity (item score ⩽ 2), and the symptom severity level must be maintained for a minimum of 6 months.

Functional recovery was rated using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) (Goldman, Skodol, & Lave, Reference Goldman, Skodol and Lave1992) to minimize the influence of the severity of psychopathology. A sustained cut-off score of ⩾ 61 over the previous 6 months was selected.

Personal recovery was evaluated using the method described by the Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (Heinrichs, Hanlon, & Carpenter, Reference Heinrichs, Hanlon and Carpenter1984). The present study involved two modifications of the QLS. First, instead of using a self-assessment procedure, QLS items were scored according to the patient's answers to the rater. Second, a summary score of two of the four QLS subscales (Instrumental Role and Intrapsychic Foundations) that better reflect the recovery construct (Anthony, Reference Anthony1993; Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Kim, Addington, McGurk, Pratt and Addington2017) was used as a measure of personal recovery (QLSper) instead of the total score (García de Jalón et al., Reference García de Jalón, Ariz, Aquerreta, Aranguren, Gutierrez, Corrales and Cuesta2023). Personal recovery was defined as a cut-off score above the first quartile of the QLSper.

Family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders

A FH-Sz was assessed using the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (Andreasen, Endicott, Spitzer, & Winokur, Reference Andreasen, Endicott, Spitzer and Winokur1977) administered during the baseline and follow-up interviews. Information from the two interviews and all available sources – including the patient, close relatives, and computerized registers of the Navarra Health System – were used.

Environmental risk score

The Maudsley Environmental Risk Score (MERS) was used (Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Sham, Kempton, Trotta, Stilo, Gayer-Anderson and Morgan2020). The MERS was computed with small changes to the six original variables: paternal age at the patient's birth (< 40, 40–50, and > 50 years old); ethnic origin (Caucasian v. non-Caucasian); urbanicity at birth (rural populations and towns with < 10 000 inhabitants, medium towns and cities with < 100 000 inhabitants, and cities with > 100 000 inhabitants); obstetric complications (OCs) were evaluated with the Lewis–Murray scale (Lewis & Murray, Reference Lewis and Murray1987) and categorized into two groups (probable and definitive v. absent); cannabis use prior to FEP was evaluated with the European version of the Addiction Severity Index (Kokkevi & Hartgers, Reference Kokkevi and Hartgers1995; McLellan et al., Reference McLellan, Luborsky, Cacciola, Griffith, Evans, Barr and O'Brien1985) and categorized into two groups (little/moderate v. high exposure); and childhood adversity was evaluated with the Global Family Environment Scale (GFES) (Rey, Reference Rey1997), which can score the global quality of the environment with a GAF-analogue scale (Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF]) from 1 to 100. A cut-off score of ⩽ 60 indicated a poor childhood environment.

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation or absolute number and percentage) for the entire sample and by group according to the dichotomized outcomes at PEPsNa discharge (no/yes for symptomatic remission, poor/good for psychosocial functioning, and poor/good for personal functioning). A Venn diagram was plotted to visually assess the overlapping between these three outcomes. A FH-Sz was considered in patients with a first-degree relative with SSD. The ERS-Sz was categorized using the third quantile of the original continuous variable, with the highest quartile (> 75%) considered to be the exposure risk state. The proportion of patients with each outcome was estimated using sample proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Bivariate associations between each demographic and clinical factor and each outcome were assessed with the t test, the chi-square (χ2) test, or Fisher's exact test.

The recommendations of Knol & VanderWeele (Reference Knol and VanderWeele2012) were followed to test the joint effect of a FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz using the relative excess ratio of interaction (RERI) to examine the statistical interaction between dichotomized measures of patients with NAFEP on symptomatic remission, functional improvement, and personal recovery. The RERI is an accepted indicator of an interaction on the additive scale. The RERI indicates the relative excess risk due to interaction between two factors. A RERI coefficient > 0 suggests a positive deviation from additivity and it is considered statistically significant when the 95% CI does not contain zero. A RERI coefficient < 0 means a negative interaction or less than additivity. In addition, the models were adjusted by age and sex. The synergy (S) index is the ratio between a combined effect and individual effects of the two factors (Hosmer & Lemeshow, Reference Hosmer and Lemeshow1992). An S index of > 1 indicates a positive deviation from additivity and is considered significant when the 95% CI does not contain one (Hosmer & Lemeshow, Reference Hosmer and Lemeshow1992). Age and sex-adjusted logistic regression models were fitted to test the joint effect of a FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz. The RERI can go from negative infinity to positive infinity, and S index from zero to infinity. Age and sex-adjusted logistic regression models were fitted to test the joint effect of a FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz. The FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz were included additively and the RERI and S index were estimated using the epiR library, version R 4.1.3. Additionally, the importance of each variable was assessed using the caret library, which allows for an estimate of the importance of each predictor based on the ‘t’ value for the slope of each predictor (the higher it is, the greater the importance on the model). For comparative purposes, age and sex – adjusted logistic regression models including both FH-Sz and ERS-Sz factors without interaction were also fitted.

Results

We included consecutive patients admitted to PEPsNa between January 2018 and December 2020, who provided written informed consent. There were 283 patients (192 men and 91 women) with an age at onset of 31.5 ± 11.33 years (Table 1). Twenty-six patients (26/281, 9.85%) had a FH-Sz and 60 patients (60/250, 25%) had a positive ERS-Sz. The mean follow-up duration was 681.32 ± 258.94 days.

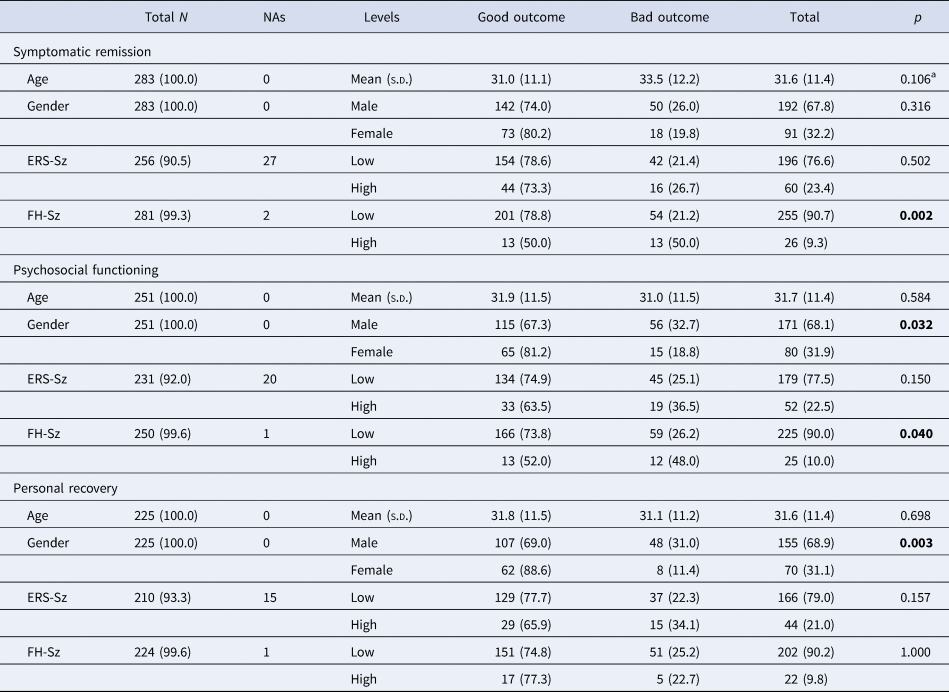

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample on the three dichotomized outcome variables at the 2-year follow-up (symptomatic remission, psychosocial functioning, and personal recovery)

ERS-Sz, environmental risk score for schizophrenia; FH-Sz, family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (first-degree relatives).

a All tests are χ2 test except for age, which is t test, and for the assessment of association of AF factor with cognitive functioning, which is the Fisher test. Bold value indicates p < 0.05.

At 2 years of follow-up, 68 patients (24.0%, 95% CI 19.3–29.5%) had not achieved symptomatic remission, 71 patients (28.3%, 95% CI 22.9–34.4%) had poor psychosocial functioning, and 56 patients (24.9%, 95% CI 19.5–31.1%) had poor personal recovery. Overlapping between these three outcomes can be seen in online Supplementary Fig. S1. About 10% of the total cohort had all three negative outcomes, whereas 18% had only one of them (5% only no remission, 6% only poor Psychosocial functioning and 7% only poor personal functioning). Univariate analyses showed that patients with NAFEP and a FH-Sz had poorer symptomatic remission (χ2 = 10.79, p = 0.002) and poorer psychosocial functioning (χ2 = 5.24, p = 0.040) than those without a FH-Sz, but there was not a significant difference in personal recovery (χ2 = 0.067, p > 0.05). In addition, having a high ERS-Sz increased the probability of a negative outcome by 11 or 12 percentage points for psychosocial functioning (from 25% to 36%) and personal functioning (from 22% to 34%), even though the associations were not significant (p = 0.15 for both) (Table 1). There was a remarkable significant association between being male and poor psychosocial and personal functioning: It almost doubled the rate of poor psychosocial functioning and almost tripled the rate of poor personal functioning (Table 1).

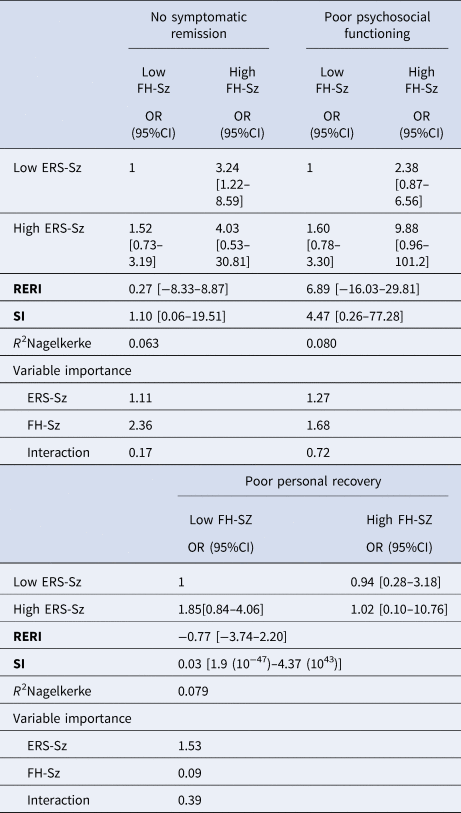

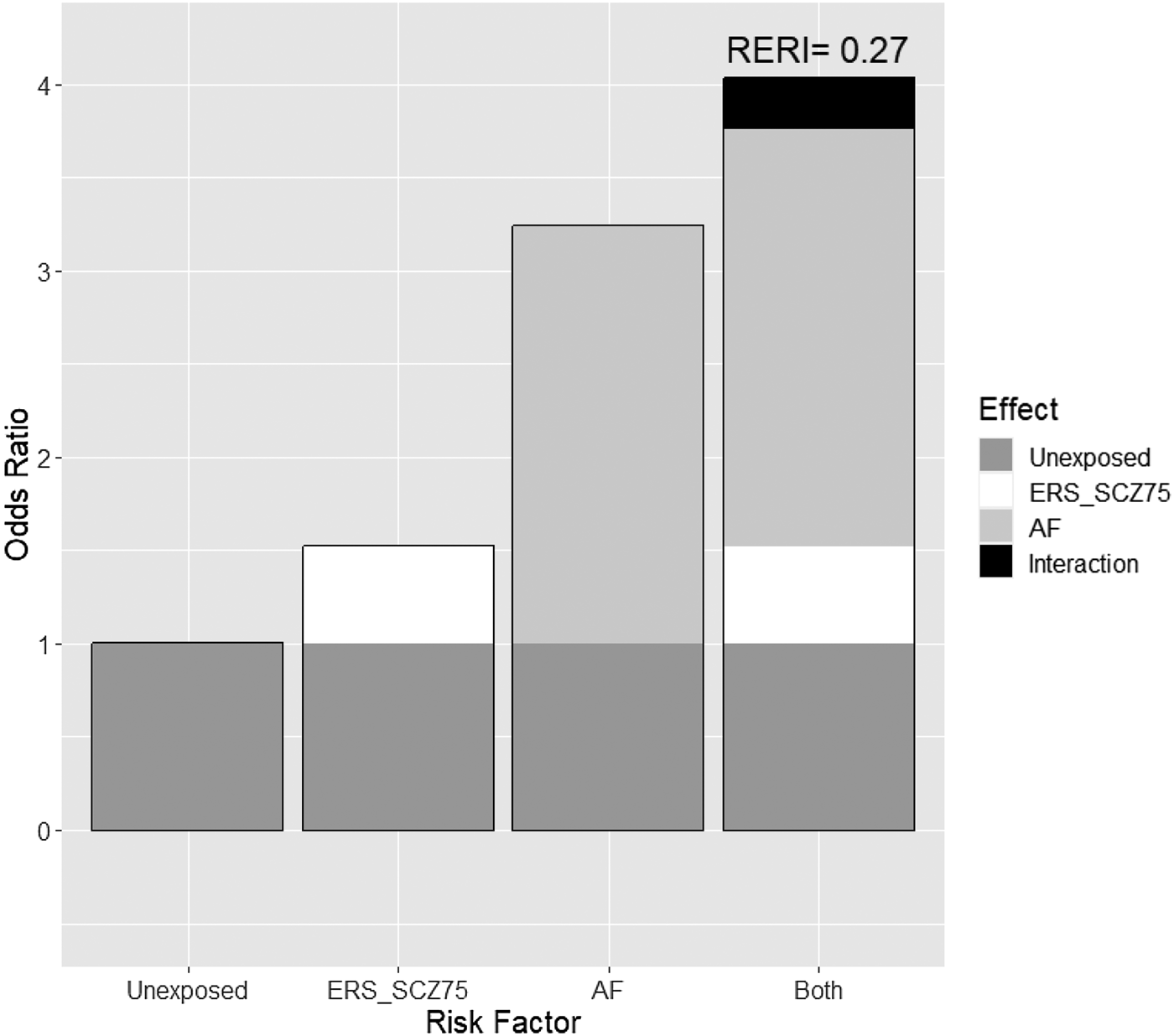

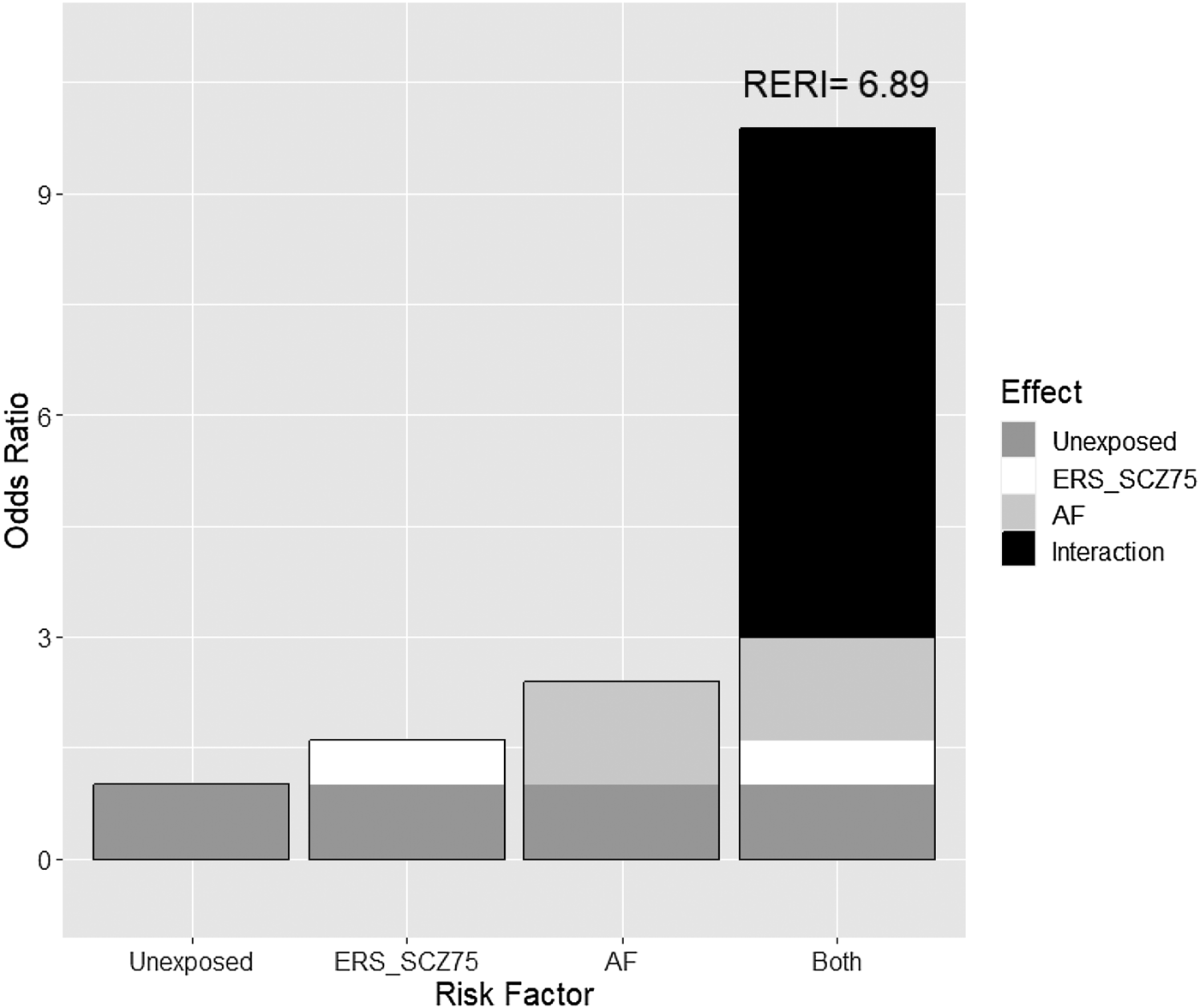

Table 2 shows the analysis of the effect and interaction between a FH-Sz and a high ERS-Sz on the three outcome measures at 2 years of follow-up. The RERI coefficients are displayed in Figs 1 and 2. Both a FH-Sz and a high ERS-Sz increased the risk of non-remission and poor psychosocial functioning, but the interactions between both risk factors on these outcome measures were not significant (symptomatic remission: RERI = 0.27, 95% CI −8.33 to 8.87; psychosocial functioning: RERI = 6.89, 95% CI −16.03 to 29.85). However, a FH-Sz doubled the risk of poor psychosocial functioning when there was a low ERS-Sz, and multiplied it by six when there was a high ERS-Sz (Table 2). The FH-Sz and ERS-Sz interaction did not increase the risk of poor personal recovery (RERI = −0.77, 95% CI −3.74 to 2.20; Table 2).

Table 2. Family load of schizophrenia and environmental risk score for schizophrenia interaction on poor the three outcomes’ measures (based on age and sex-adjusted logistic regression models)

CI, confidence interval; ERS-Sz, environmental risk score for schizophrenia; FH-Sz, family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (first-degree relatives).

RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction. Adjusted for sex and age. RERI = 0 means no interaction or exactly additivity; RERI > 0 means positive interaction or more than additivity; RERI < 0 means negative interaction or less than additivity. S < 1 means negative interaction or less than additivity. RERI and S ranges from zero to infinity.

Figure 1. Additive effect of environmental risk score for schizophrenia (ERS-Sz) with family load of schizophrenia (FH-Sz) on the risk of no symptomatic remission in patients with non-affective first episode of psychosis at 2 years of follow-up. RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction.

Figure 2. Additive effect of the environmental risk score (ERS-Sz) with family load of schizophrenia (FH-Sz) on the risk of poor psychological functioning in patients with non-affective first episode of psychosis at 2 years of follow-up. RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction.

In the age-gender adjusted logistic analysis without interaction terms, the FH-Sz was significantly associated with poor symptomatic remission (odds ratio [OR] 3.13, 95% CI 1.28–7.61, p ⩽ 0.012) and poor psychosocial functioning (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.12–6.98, p ⩽ 0.028), but had not any effect on personal recovery (online Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, the magnitude of the effects of the ERS-Sz on symptomatic remission (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.74–3.02), poor psychosocial functioning (OR 1.74, 95% CI 0.87–3.45), and poor personal recovery (OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.83–3.73) were not significant, although the OR for each outcome had a moderate magnitude (online Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

There are three main findings from this two-year prospective cohort study searching for outcome predictors for patients with NAFEP admitted to an EIS. First, a FH-Sz showed significant predictive power for poor symptomatic remission and psychosocial functioning, but not for poor personal recovery considering a sample of patients with NAFEP admitted to an EIS. Second, there were non-significant associations between the ERS-SZ and the three outcome measures. Third, there was not a significant interaction between a FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz in predicting poor outcomes, but the magnitude of the parameter that measures departure from additivity was high for psychosocial functioning (RERI = 6.89, 95% CI −16.03 to 29.81).

The rates of symptomatic remission (76%), good functioning (71.7%), and good personal recovery (75.1%) are in agreement with a recent systematic review (Lally et al., Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Stubbs, Cullinane, Murphy, Gaughran and Murray2017) and another study (Phahladira et al., Reference Phahladira, Luckhoff, Asmal, Kilian, Scheffler, Plessis and Emsley2020). The high predictive value of a FH-Sz (high family load for schizophrenia) for poor symptomatic remission and psychosocial functioning is in agreement with studies reporting that a FH-Sz is the best predictor of this diagnosis (Andreassen, Hindley, Frei, & Smeland, Reference Andreassen, Hindley, Frei and Smeland2023; Lichtenstein et al., Reference Lichtenstein, Yip, Björk, Pawitan, Cannon, Sullivan and Hultman2009). Moreover, a FH-Sz has been associated with poor occupational and global outcomes in patients with schizophrenia (Bromet, Naz, Fochtmann, Carlson, & Tanenberg-Karant, Reference Bromet, Naz, Fochtmann, Carlson and Tanenberg-Karant2005; Esterberg, Trotman, Holtzman, Compton, & Walker, Reference Esterberg, Trotman, Holtzman, Compton and Walker2010; Käkelä et al., Reference Käkelä, Panula, Oinas, Hirvonen, Jääskeläinen and Miettunen2014; Verdolini et al., Reference Verdolini, Amoretti, Mezquida, Cuesta, Pina-Camacho, García-Rizo and Bernardo2021) and in patients with more positive and emotional symptoms (Käkelä et al., Reference Käkelä, Marttila, Keskinen, Veijola, Isohanni, Koivumaa-Honkanen and Miettunen2017). A FH-Sz has also been related to greater psychopathological symptoms (Esterberg & Compton, Reference Esterberg and Compton2012) and more admissions at follow-up (Feldmann, Hornung, Buchkremer, & Arolt, Reference Feldmann, Hornung, Buchkremer and Arolt2001). Other illness-onset features have been associated with a FH-Sz, such as a younger age at onset and a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) (Esterberg & Compton, Reference Esterberg and Compton2012).

A family history and genetic risk of psychosis are overlapping domains and subjects with a family history of schizophrenia carry a higher genetic risk burden than those without a family history (Bigdeli et al., Reference Bigdeli, Ripke, Bacanu, Lee, Wray and Gejman2016). Moreover, genetic risk scores and a thorough family history explained 9% of the variation in schizophrenia liability; the accuracy of discrimination can be improved by combining these two factors (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Pouget, Andreassen, Djurovic, Esko, Hultman and Sullivan2018). This improvement may be related to the facilitator action of family dynamics and their interactions that confer genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia (Stapp, Mendelson, Merikangas, & Wilcox, Reference Stapp, Mendelson, Merikangas and Wilcox2020). However, while a FH-Sz and depression imply genetic liability, a negative family history provides little information about the genetic liabilities of the illness (Kendler & Cloninger, Reference Kendler and Cloninger1987).

We did not find significant associations between the ERS-Sz and the three outcome measures. Our results are different from two recent studies that revealed indices of cumulative environmental liability for schizophrenia are significantly associated with poor functioning in patients with FEP (Erzin et al., Reference Erzin, Pries, van Os, Fusar-Poli, Delespaul, Kenis and Guloksuz2021, Reference Erzin, Pries, Dimitrakopoulos, Ralli, Xenaki, Soldatos and Stefanis2023). These differences might be due to the type of sample (patients with FEP v. patients with NAFEP), the study design (cross-sectional or brief short-term longitudinal v. follow-up for years) and the setting (naturalistic v. patients in an EIS program). However, there was a trend toward a significant association between the ERS-SZ and poor outcomes in our study. In fact, a high ERS-Sz increased the probability of poor psychosocial functioning from 25% to 36% and poor personal functioning from 22% to 34% (p = 0.15 for each outcome measure; Table 1). Thus, the non-significant results may be related to a lack of statistical power rather than the absence of an association.

We used the RERI as the standard measure of the interaction on the additive scale in the case-control study involving two dichotomized risk factors. Four previous studies used the RERI approach with case–control designs (Mas et al., Reference Mas, Boloc, Rodríguez, Mezquida, Amoretti, Cuesta and Group2020; Pries et al., Reference Pries, Dal Ferro, van Os, Delespaul, Kenis, Lin and Guloksuz2020) to estimate individual exposures (Guloksuz et al., Reference Guloksuz, Pries, Delespaul, Kenis, Luykx, Lin and van Os2019) and to examine the association with long-term functioning of patients with FEP (Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Papiol, Ibañez, García de Jalón, Sánchez-Torres, Gil-Berrozpe and Peralta2023). Pries et al. (Reference Pries, Dal Ferro, van Os, Delespaul, Kenis, Lin and Guloksuz2020) reported evidence for an additive interaction between the PRS for schizophrenia (PRS-Sz) and the exposome score for schizophrenia (ES-Sz) to increase the odds of schizophrenia in a large data set of patients and siblings from two different projects. In a FEP cohort, Mas et al. (Reference Mas, Boloc, Rodríguez, Mezquida, Amoretti, Cuesta and Group2020) revealed a suggestive, but not statistically significant, additive interaction between the PRS-Sz and the ERS-Sz. Moreover, Sinan Guloksuz et al. (Reference Guloksuz, Pries, Delespaul, Kenis, Luykx, Lin and van Os2019) found evidence for an additive interaction of joint associations between a dichotomized PRS and individual environmental exposures, such as lifetime regular cannabis use and exposure to early-life adversities, but not with the presence of hearing impairment, birth during winter and exposure to physical abuse or neglect in childhood. They did not use an aggregate ES-Sz. In our previous study (Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Papiol, Ibañez, García de Jalón, Sánchez-Torres, Gil-Berrozpe and Peralta2023), we provided evidence for an additive model of familial antecedents of schizophrenia, environmental risk factors, and polygenic risk factors as contributors to a poor functional outcome in a naturalistic 21-year follow-up study of patients with FEP.

We found neither significant associations nor significant joint effects of a FH-Sz and the ERS-Sz on personal recovery. It is worth noting that patients with FEP show a heterogeneous pattern of recovery even when following EIS programs (Griffiths & Birchwood, Reference Griffiths and Birchwood2020; Griffiths, Lalousis, Wood, & Upthegrove, Reference Griffiths, Lalousis, Wood and Upthegrove2022; Lambert, Karow, Leucht, Schimmelmann, & Naber, Reference Lambert, Karow, Leucht, Schimmelmann and Naber2010). This factor adds complexity to the known discrepancy between self- and caregiver perceptions of recovery in FEP (Anthony, Reference Anthony1993; Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Lundin, Moe and Breitborde2023; Cuesta, Reference Cuesta2023; Van Eck et al., Reference Van Eck, van Velden, Vellinga, van der Krieke, Castelein, van Amelsvoort and Schirmbeck2023). In fact, symptomatic and personal recovery only partially overlap, although they may share some predictors, such as premorbid adjustment that seems to predict functional outcome and relapse, as well as poor recovery in FEP (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, O'Donoghue, Thompson, Gleeson, Bendall, Gonzalez-Blanch and McGorry2016; O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Hannigan, Doyle, Kinsella, Sheridan, Kelly and Clarke2019; Peralta et al., Reference Peralta, García de Jalón, Moreno-Izco, Peralta, Janda and Sánchez-Torres2022; Santesteban-Echarri et al., Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, González-Blanch, McGorry, Gleeson and Alvarez-Jimenez2017). Moreover, affective, but not positive and negative symptoms, seem to be related to personal recovery (Van Eck et al., Reference Van Eck, van Velden, Vellinga, van der Krieke, Castelein, van Amelsvoort and Schirmbeck2023), and affective symptoms are not included in the RSWG criteria for remission.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, there has been a great deal of research and clinical practice interest in the existence of a family history of psychiatric disorders. Family history density measurements may be preferred over simple dichotomous measures, although both methods are useful as prognostic measures of psychosis outcomes(Ali et al., Reference Ali, Sreeraj, Nadella, Holla, Mahadevan, Ithal and Jain2021). Second, we did not include a PRS as a measure of the individual genetic predisposition to develop psychosis. However, the extent to which a PRS may improve the prediction of individualized outcomes relative to information from a routine psychiatric assessment is still limited (Fusar-Poli, Rutten, van Os, Aguglia, & Guloksuz, Reference Fusar-Poli, Rutten, van Os, Aguglia and Guloksuz2022; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Kaji, Cotter, Van Vleck, Belbin, Preuss and Charney2021). Third, there have been several methods used to extract environmental risk factors – either individual or aggregate scores – to examine their associations with clinical and functional measures (Pries et al., Reference Pries, Erzin, Rutten, van Os and Guloksuz2021). Environmental aggregate scores are dependent on the exposure variables included, and it is likely that some variations in the results might be due to the different measurement methods or composition of aggregate scores among studies. Fourth, we did not find significant RERI estimates even though their magnitudes showed a trend for statistical significance. Thus, our sample size may have limited the strength of our results. Fifth, dichotomization of outcome variables may reduce statistical power but may facilitate fulfillment of model assumptions and also interpretability when interaction terms are assessed and is a common practice in medical and epidemiologic research. Moreover, the requirements of model diagnosis when continuous variables based on scales are considered as outcomes (normality of the error term, homoscedasticity, and no correlation, among other assumptions) are not easy to hold. Additionally, we chose to dichotomize outcomes because the interaction or additivity effects between variables by means of the RERI are better accounted for by metrics based on a relative risk scale (Richardson & Kaufman, Reference Richardson and Kaufman2009) and these interactions on the additive scale cannot be used for ordinal or continuous variables (VanderWeele, Chen, & Ahsan, Reference VanderWeele, Chen and Ahsan2011). Finally, the environmental risk paradigm in psychosis is dependent on the definition of psychiatric phenotypes and temporal features of the exposures on the patient. We hypothesize that the inclusion of dimensional and transdiagnostic phenotypes (Waszczuk et al., Reference Waszczuk, Jonas, Bornovalova, Breen, Bulik, Docherty and Waldman2023) may improve future gene-environment interaction studies.

Conclusions

A FH-Sz or a high ERS-Sz may guide clinicians to identify patients with NAFEP and potentially poor psychosocial outcomes during the first 2 years of follow-up. For patients with NAFEP, the presence of either a FH-Sz or a high ERS-Sz multiplies the risk of poor psychosocial functioning by 1.5–2 at 2 years of follow-up, and the presence of both multiplies the risk by 10 (95% CI 0.96–101.2). These results may stimulate future studies with larger samples aimed at verifying the interaction between familial antecedents and environmental risk factors by using the RERI approach.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000576

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Government of Navarra (grant 20/21) and by the Carlos III Health Institute (FEDER Funds) from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity (16/2148 and 19/1698).