Introduction

Lobbying is at the center of the trade politics literature and trade is at the center of the lobbying literature. This fruitful scholarly tradition contains, however, no large-scale empirical studies identifying the effect of interest groups’ lobbying for a particular trade policy on their receipt of that particular policy. As a result, while the literature mostly agrees that trade lobbying is impactful,Footnote 1 the scale and nature of that impact remain unclear. In particular, many opportunities remain to examine variation in the effectiveness of lobbying across lobbiers. We provide evidence on both of these points: trade lobbying effectiveness and its variation across lobbying firms.

The China trade war furnishes the opportunity to do so. Beginning in 2018, the Trump administration imposed new tariffs on nearly all imports from China. These tariffs were unpopular among many American companiesFootnote 2 and the United States Trade Representative (USTR) offered firms an opportunity to request that tariffs not be imposed, referred to as exclusion.Footnote 3 Firms (and industry associations) submitted many requests for exclusion to the USTR, which then decided whether to grant or deny each application. At the same time, a furious campaign of lobbying the USTR, as well as allies in the Congress and Executive branch, unfolded as firms sought assistance in securing exclusion from across the government. This campaign is visible in public lobbying disclosures.

We argue that lobbying for exclusion primarily represented a chance for firms to signal preference intensity: the tariffs were going to cause serious harms to their business and they showed it by taking time and money to let regulators know.Footnote 4 In turn, regulators used the information revealed by lobbying to resolve uncertainty about which firms would be seriously impacted by the tariffs as they navigated two goals: preserving the bulk of the Trump tariffs imposed on China, so as not to undercut the appearance of the administration’s trade policy reorientation, but also avoiding the worst effects of the tariffs on American businesses, workers, and the economy. Thus we expect that lobbying firms were more likely to receive exclusion than non-lobbying firms.

Building on this, we also expect differences in the responsiveness of the USTR depending on the requesting firm’s size. Larger firms play a larger role in the economy, contributing more to growth, jobs, and financial markets.Footnote 5 If regulators were concerned about reducing the damage from tariffs, while also limiting the number of exceptions, then larger firms that lobby are an optimal target for exclusion.Footnote 6 Thus we expect that larger firms’ lobbying will be more impactful. This argument also suggests an exception to the size-lobby effectiveness nexus: firms that own Chinese subsidiaries are not good targets for exclusion, since more of the economic benefits of exclusion would redound to Chinese workers or the Chinese economy.

To test these ideas, we gather data on requests for exclusion and on lobbying. Requests were made public by the USTR along with the USTR’s decision on whether or not to grant exclusion. We match exclusion requesting firms to a rich array of information: technical criteria provided on the exclusion request reports; campaign contributions, other lobbying expenditures, and political geography; firm-level characteristics like size and the ownership of foreign subsidiaries; and, industry-level features, particularly, exposure to trade. To measure lobbying, we carefully scour lobbying reports for evidence of lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs. We rely on a rich set of controls to partial out confounding factors and explore a variety of samples and measurement strategies.

Our models show that lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs had a highly robust, positive effect on the likelihood of earning exclusion. On average, firms that lobbied on the tariffs increased their chance of earning exclusion somewhere between 10% and 16%. Since only 13% of exclusion requests were approved, these are significant relative effects. But they also make clear that many lobbying firms did not ultimately earn exclusion. We show that this variation in lobbying success is strongly related to firm size and investment in China. Lobbying had little to no effect on earning exclusion for the smallest firms, but is increasingly impactful as firms get larger. The notable exception to this is that firms which own Chinese subsidiaries (who are often quite large) were significantly less likely to have their exclusion requests granted, regardless of whether they lobbied or not. The size premium and China penalty in lobbying effectiveness we identify are each remarkably large.

We make three contributions. First, we find large-N statistical evidence that lobbying for specific policy outcomes results in greater success in achieving those exact outcomes. This complements literature which shows in other ways that lobbying is important.Footnote 7 We also contribute new evidence on heterogeneity across firms in lobbying effectiveness. Second, the recent trade politics literature argues that larger firms are generally pro-trade and are more likely to lobby because of their financial and political resources, helping to explain the rise of globalization.Footnote 8 We complement these findings by showing that larger firms are also more successful when they lobby though their influence may be limited if they are multinationals (MNCs) invested in strategic competitors. Finally, we shed light on the motivations of policymakers, arguing that many regulators and policymakers are concerned with harm to the US economy: its firms, workers, financial markets, and development.Footnote 9 In particular, this concern is front-of-mind when balancing the demands of pro-trade corporate lobbyists and pro-tariff politicians. Tensions between dyed-in-the-wool protectionists and policymakers eager to minimize tariffs’ harms look set to recur in American trade policymaking.

Theory

Does trade lobbying work?

Are firms and other special interests that lobby for particular trade policy outcomes more likely to get those policies from the government? The trade lobbying literature is vast, so it may seem that this question has been answered, and serially. In fact, our review of the literature finds no large-N study which examines whether lobbying on specific trade policies is effective at securing those policies. Instead, it is more often shown that lobbying spending in the aggregate is linked to policy success; or, indirect tests are employed which imply that lobbying is important. This is no criticism of work which provides key insights and often has aims beyond our focus on lobbying effectiveness. Our only point is that there is a gap in the literature which ought to be filled by examining trade lobbying for limited and specific policy outcomes matched to outcomes on those exact policies. We review the literature to make this point.

Special interest lobbying has been at the center of the trade politics literature from its inception. Trade lobbying played a key role in the development of the main competing theories of lobbying which argue that lobbying is driven by: costly signaling of interest, where lobbying expenditures credibly convey preference intensity;Footnote 10 quid pro quos, where special interests make promises of support or threats of retaliation in exchange for policy;Footnote 11 consultation and information-sharing, where policymakers seek to effectively represent interest groups;Footnote 12 or the provisions of work products like political intelligence, policy research, or legislation to allied policymakers.Footnote 13

We are interested in the question of whether trade lobbying works. One approach has been to look for indirect empirical implications of lobbying’s effectiveness. As examples, Bombardini (Reference Bombardini2008) finds that firm size dispersion is linked to lower tariffs and that larger firms lobby more; Kim (Reference Kim2017) finds that product differentiation leads to both firm-level lobbying and lower tariffs; and Bearce and Roosevelt (Reference Bearce and Roosevelt2023) shows that firms lobby more in democracies (which have lower tariffs). All of these studies are consistent with an effective special interest lobbying channel.

Empirical tests of the Grossman and Helpman (Reference Grossman and Helpman1994) model are similarly suggestive that lobbying works.Footnote 14 Some of this work uses general lobbying expenditure data (Gawande and Bandyopadhyay, Reference Gawande and Bandyopadhyay2000), Foreign Agents Registration Act filings (Gawande et al., Reference Gawande, Krishna and Robbins2006), or counts of lobbyists (Stoyanov, Reference Stoyanov2009) to measure political organization. These studies find that organized import-competing industries secure higher tariffs than unorganized ones, indicating that lobbying played a role in securing those policy victories.

The literatures on lobbying and resource misallocation (Huneeus & Kim, Reference Huneeus and Song Kim2018) and lobbying and market performance (Borisov et al., Reference Borisov, Goldman and Gupta2016; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Parsley and Yang2015; Kim, Reference Kim2008) also imply that lobbying works. Some of this scholarship investigates trade lobbying specifically.Footnote 15 Both of these literatures use economic outcomes or firm-level financial performance as outcomes, not policy outcomes.

Nearer to our target are studies that show that lobbying intensity or expenditures generally, though not trade lobbying specifically, are linked to trade policy success.Footnote 16 For example, Lee and Baik (Reference Lee and Baik2010) shows that firms that lobby more in the aggregate received higher Byrd Amendment payouts on anti-dumping duties. Closer still are studies showing that trade lobbying—in general, and not on a specific issue—is associated with specific trade policy outcomes. For example, Drope and Hansen (Reference Drope and Hansen2004) shows that lobbying expenditures (and PAC contributions) are linked to favorable USITC anti-dumping rulings, while Ludema et al. (Reference Ludema, Maria Mayda and Mishra2018) shows that trade lobbying expenditures by import-competing firms reduce the likelihood that tariff suspensions are enacted.

Two strands of literature come the closest to our target of a large-N study on whether lobbying on specific trade policy outcomes contributes to success on those specific outcomes. First, a small-N literature has examined particular cases or policies and shown that lobbying was impactful in those instances (Eckhardt, Reference Eckhardt2011; Eckhardt, Reference Eckhardt2015; Rasch, Reference Rasch2018, e.g.,). Second, a number of studies have examined the policy effects of lobbying for specific policies in non-trade domains, for example, funding for universities (De Figueiredo and Silverman, Reference De Figueiredo and Silverman2006), federal energy legislation (Kang, Reference Kang2016), and various state-level policies (Grasse and Heidbreder, Reference Grasse and Heidbreder2011).

Overall, we see no existing large-N trade lobbying scholarship which examines the success rate of special interests’ lobbying on specific trade policies. Filling this gap is useful. First, it is valuable to know for certain that interests have actually lobbied on specific outcomes. This narrows the scope for alternative interpretations and raises the probability that lobbying achieved the political work.Footnote 17 It reduces noise in the explanatory variable, too. Second, studies which examine non-policy outcomes, like market value, or highly complex policies, like multilateral trade agreements, focus on important bottom line outcomes. But these complex and downstream outcomes are the result of many causes which raises the chances of confounding. Third, case studies are important and valuable. But it is useful to replicate their careful focus on particular acts of lobbying and specific outcomes in a large-N setting, where tests are more powerful and controlling for a larger number of confounding factors is feasible. Large-N tests also enable new research designs and sensitivity tests, and for the systematic evaluation of moderating factors, all points that we consider below.

Exclusion requests

Background on Section 301 tariffs and exclusion requesting We have highlighted the benefits of measuring lobbying and outcomes on a specific trade policy outcome, but what policy? Starting in July 2018, and extending to January 2020 when the Phase One Trade Agreement was signed, four rounds (“lists”) of punitive tariffs were unveiled on a large range of Chinese imports. The tariffs were authorized under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 in order to provide relief from China’s “unreasonable or discriminatory practices” relating to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation. The Section 301 tariffs aimed to counter China’s practices and compensate $50 billion in estimated harm to the US economy.Footnote 18 Ultimately, Section 301 tariffs were imposed on $375 billion worth of imports from China, ranging from 7.5% (list 4A; $125 billion) to 25% (lists 1–3; $250 billion). China retaliated with tariffs on US exports.

For each proposed list of tariffs, the USTR heard from numerous stakeholders through notice and comment and public hearings. Many expressed concerns about the use of Section 301 tariffs, which led the USTR to create a process whereby interested parties could request that a particular product be excluded from each round of tariffs. From 2018 to 2020, US stakeholders submitted nearly 53,000 exclusion requests to the USTR. Exclusion requests for lists 1 and 2 tariffs were accepted through Regulations.gov; the USTR developed a dedicated online portal for lists 3 and 4A. To submit a request, exclusion requesters had to identify the 10-digit HTSUS code for each product for which they sought exemption along with the name and description of the product, and answers to various other questions.

The USTR granted exclusion on about 12.9% (6,817) of the requests and denied 87.1% (45,929).Footnote 19 Notably, the Trade Act does not outline a formal process for tariff exclusions nor does it require the USTR to establish one. Thus, the USTR is known to have evaluated each exclusion request on a case-by-case basis but with consideration of several technical factors.Footnote 20 These included product availability outside of China, potential economic harms, and the strategic importance of the product to “Made in China 2025” or other Chinese industrial programs.

Useful features of exclusion requests for examining lobbying effectiveness The trade war tariffs, along with the lobbying process for tariff exclusion, have several favorable properties to examine the efficacy of lobbying. First, the trade war tariffs are a simple, straightforward policy change: either maintain an additional tariff on certain imports from China or suspend the tariff. This is a discrete, two-pronged choice that is either made or not. Using a specific issue where there is a clear indicator of a policy failure or success for the lobbying group improves the precision in our estimates of the effectiveness of lobbying.

Second, the tariff exclusion process required firms to formally request exclusion in a public document revealing their desire for the tariff to be removed. Thus we know firms’ position on the policy with clarity. Existing studies on lobbying generally do not know the position of lobbying interest groups on an issue in question.Footnote 21

Finally, the exclusion request process avoids some challenges with assessing lobbying effectiveness noted in the literature. Lobbying is often about preserving the status quo (Baumgartner, Reference Baumgartner2009) or incremental change (Lindblom, Reference Lindblom1959). The exclusion request process follows a moment of sudden and punctuated policy change where observing real variation in policy is possible. Likewise, Baumgartner (Reference Baumgartner2009) emphasizes how much lobbying runs aground on a lack of attention from politicians or bureaucrats. This is not a problem in our case, because a whole new apparatus was created within the USTR to decide on exclusion requests, and the question of applying a tariff or not is binary and simple. So some sort of policy response was guaranteed to result. More generally, policymakers and interest groups alike were aware that the large new tariffs constituted a significant policy change, and the salience of the issue was substantial.

Lobbying and exclusion requests success We hypothesize that firms that lobbied for exclusion were more likely to be granted their request than firms that did not lobby. In making this argument, we consider the four theories of lobbying mentioned above—costly signaling, quid pro quos, information, and work/subsidy—and argue that only the first and perhaps the second are plausible theories of the impact of lobbying in the case of exclusion requests.

One approach to lobbying is that it is a costly signal of interest in a particular policy outcome, since lobbying is expensive and time-consuming.Footnote 22 Under this approach, lobbying for exclusion signaled that the new tariffs were genuinely important to the lobbying company, over and above the time and money costs of the initial exclusion request. Lobbying the USTR directly could clearly serve such a function.Footnote 23 Lobbying the Congress serves a similar function, but has the added benefit that both the lobbyist and the member of Congress signal to the USTR that they care about the request. In fact, a majority of lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs was targeted at the Congress.Footnote 24 Either way, the regulator uses this information about preference intensity to optimally distribute policy concessions. Granting exclusion to all firms would undermine the administration’s policy goals. Collecting information on the firms that are most severely impacted by the tariffs allowed the administration to restrict exceptions to critical cases.

Another theory of lobbying is that it is a site where quid pro quos are hashed out. For the minority of lobbiers in our data that directly lobbied the USTR or Office of the President, the quid pro quo theory would argue that lobbying was a site to offer political support (or threaten non-support) for the president. The USTR, as an agent of the president, might then be more inclined to grant exclusion. However, a majority of Section 301 lobbiers lobbied the Congress. A quid pro quo might apply there in relation between the lobbying firm and the member of Congress, but lobbying a member of Congress to have their staff clarify a quid pro quo with the executive branch seems rather inefficient. Nor is it likely that members of Congress were offering quid pro quos to the USTR. So on theoretical and empirical grounds, we are left with some doubt about the overall importance of the quid pro quo theory. We follow up on this in our empirical analysis.

Lobbying has also been interpreted as a site where policymakers and interests groups that are allied work together. In this view, lobby meetings involve either non-strategic information transmission to policymakers uncertain about the interest group’s policy preferences or “legislative subsidy” where lobbyists help politicians to do their work (Hall and Deardorff, Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). We do not think a pure information transmission channel is important in the case of lobbying the USTR directly, since the exclusion request itself contains all the pertinent details. Lobbying a Congressional office may serve an informational purpose—to alert an ally in government about a policy interest—but again the member of Congress following up with the USTR does not seem to serve any informational function, since the USTR already knows the exclusion requesters’ request. For similar reasons, we also do not think that a legislative or regulatory policy “subsidy” story fits here, since the specific policy task of the USTR was straightforward and procedurally institutionalized.

Thus, either via a signaling mechanism or perhaps a quid pro quo mechanism, we expect lobbying by exclusion requesting firms to increase the likelihood of receiving exclusion:

Hypothesis 1: Trade lobbying works. Firms that lobbied on the Section 301 tariff exclusion process are more likely to earn an exclusion from the USTR.

For whom does trade lobbying work?

Firm size and lobbying effectiveness: While the exclusion process provides an ideal opportunity to explore the effectiveness of trade lobbying, we can go further. If trade lobbying is not perfectly effective—if some firms that lobby do not get their request granted—then we have a chance to investigate why lobbying works in some instances but not in others. As we shall see below, there is indeed considerable variation in the effectiveness of lobbying across exclusion requests.

Several approaches to variation in lobbying effectiveness have been offered in the literature. Scholars have examined properties of the lobbyist, primarily their political connections and accumulated policy expertise.Footnote 25 We do not focus on this. Scholars have also examined the variation in political institutions.Footnote 26 We do not investigate their effect here, and institutions are constant in our case anyway. Finally, some literature has examined properties of the lobbying client.Footnote 27 Building on this line of research, we explore a different hypothesis, that larger firms—firms with more revenue or employees, for example—are more effective at securing their interests through lobbying:

Hypothesis 2: The firm size premium in lobbying effectiveness. The positive effect of lobbying on securing desired policy outcomes is greater for bigger companies than for smaller ones.

Note that this hypothesis complements but is different from recent scholarship which argues that larger firms are more likely to lobby or otherwise politically mobilize.Footnote 28 We instead argue that larger firms are more likely to succeed when they do lobby.Footnote 29

Larger firms might be more successful lobbiers for several reasons. First, they have a greater footprint in the economy.Footnote 30 Politicians wish to design policy, at least in part, to see elements of the economy thrive and grow. This is so for reasons both virtuous (for the well-being of their district or the country) and venal (for reelection and power). Given a choice between handing a policy win to either a small company or large company, policymakers may prefer to give their favors to bigger companies. Larger companies have more connections with the economy and greater influence on economic growth. They employ more workers, and so have a bigger impact on workers and labor. Bigger companies also are more important in financial markets and so have a greater impact on owners of capital, including retail stock investors and savers.Footnote 31

In our case, this argument relies on an assumption that the USTR was operating as if it had a fixed quantity of exclusions as a constraint, not a fixed quantity of exempted imports from China. We think it is plausible that the USTR felt such a constraint. Granting exclusions en masse to a large percentage of small firms would have created the impression that the policy was being systematically undermined with an easily quantifiable metric: share of exclusions granted. Granting a small number of exclusions to the biggest firms would reduce this impression even if the net effects on trade with China were the same. In this sense, we view the USTR as strategically compromising the administration’s goal of reduced imports from China in order to minimize damage on the American economy, a plausibly important goal for USTR bureaucrats.

Of course, a firm size and lobbying effectiveness link, as in Hypothesis 2, might also arise via other mechanisms. Larger firms have greater political resources to give to politicians (Drope and Hansen, Reference Drope and Hansen2004). Bigger companies are much more involved in campaign giving, and can back up lobbying requests with credible quid pro quos. Their top officers and employees are greater in number, and can support the corporations’ political strategy. Bigger companies can also promise other forms of political support, including implicit endorsements, political work, and even votes at small margins. As noted above, we think the quid pro quo story is not a perfect fit for Section 301 lobbying since most firms did not lobby the USTR directly. But we are able to develop empirical proxies (using campaign contributions) for this mechanism to test it below.

The “exit and voice” framework argues that lobbying success is about credible threats of exit in policy bargaining with policymakers (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Golder and Golder2017; Zeng, Reference Zeng2021; Palan, Reference Palan2024). In our context, that would mean firms threatening to move operations overseas because of unfavorable trade policies. Larger firms have two advantages in this bargaining. Because they are larger, politicians are likely to view the lost output, jobs, and positive externalities generated by those companies leaving as significant (Kim and Milner, Reference Kim and Milner2021). Larger companies also have a more credible threat of exit because they are much more likely to have foreign branches or subsidiaries, or to be foreign.Footnote 32 While generally plausible, this argument is not a good fit for the exclusion request process. Threatening to move production overseas to China to export back to the United States wouldn’t make sense for a firm amidst the trade war. Threatening to move to a third country (without tariffs on Chinese inputs) might make more sense but would be risky in light of the Trump administration’s other tariffs and predilection for protectionism.Footnote 33 As with quid pro quos, we develop empirical proxies to test this mechanism below: if operative, this mechanism would imply that large firms with Chinese or other foreign subsidiaries should be more successful lobbiers than other large firms.

Two other mechanisms might make larger firms more successful, both related to behavioral patterns in lobbying. It could be that larger firms spend more per lobbying report. It could also be that larger firms can afford to make more requests for exclusion. If the USTR reacted to firms making multiple requests in a conciliatory fashion (“let’s grant them at least one request”) then it’s possible that larger firms would get more exclusions. We address these ideas empirically below.

US Multinationals in China We argued above that large firms might be more effective in their lobbying because of their larger contributions to the economy. This argument suggests an additional hypothesis, because one kind of big company makes fewer contributions to American workers, wages, and growth relative to their size: multinationals. Of particular interest in our setting are firms that own plants or subsidiaries in China, since the exclusion process unfolded in a context of heightened strategic competition with China. Granting exclusion to firms invested in China may have been viewed negatively by the USTR because more policy benefits would flow to Chinese workers, Chinese suppliers, and the Chinese economy. These arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The China penalty in lobbying effectiveness. The positive effect of lobbying on securing desired policy outcomes is lesser for companies that own subsidiaries in China.

Note that our argument is not narrowly about the good for which exclusion is requested. Firms sourcing a good from a Chinese manufacturer would be no more effective in their lobbying than firms sourcing from their own Chinese subsidiary because both modes of sourcing benefit Chinese workers and supply networks. Policymakers granting exclusion had no option but to create some positive externalities for China in respect to the specific good being sourced. Instead, our argument is broader, about the overall effects of granting policy favors to companies with production more or less focused within the United States. If a firms’ production facilities are mostly located inside the United States, then we expect that US workers and suppliers will gain significantly from a tariff exclusion that helps the firm to remain competitive. If more of a firms’ production facilities are located in China, then we expect that US workers and suppliers will gain less from an exclusion that helps the firm to remain competitive. We think it is plausible that policymakers might view the exclusion request process in these terms and would believe there are fewer US-internalized benefits from granting policy favors to multinationals and that there are undesirable positive externalities to rewarding firms with foreign affiliates in China.Footnote 34

The specific context of the trade war and the deteriorating United States-China relationship may have heightened concerns about US firms operating in China. The trade war itself was partly motivated by concerns about forced technological transfer and lost intellectual property. China’s focus on defense-related high-tech industrial development also raised concerns about US multinationals spreading sensitive technologies. And while supply chains based on either foreign affiliates or arm’s length imports would be vulnerable to curtailment in the event of conflict, foreign affiliates raise more concerns, about rigidly inflexible supply chains and the specter of lost industrial capital.

Finally, we acknowledge that a penalty applied to American multinationals with Chinese affiliates may arise from less rational calculations. First, Trump administration officials may not have appreciated similarities between arm’s length contracting and vertical FDI. Instead, they may have viewed the latter as inherently worse for the US economy (Margalit, Reference Margalit2011). Second, it may be that the public, media, or interest groups would have reacted negatively to granting exclusion to firms with Chinese subsidiaries and so the administration sought to avoid blowback. Finally, it could be that the Trump administration itself viewed American firms that close American factories to open offshore facilities as particularly perfidious, a view which has been regularly articulated by members of both parties including Trump himself.

Data and research design

Sample, outcome, and main explanatory variable: We examine requests for exclusion from the Section 301 tariffs imposed on US imports from China since 2018. The individual exclusion request is our unit of analysis, and our sample consists of the 52,746 exclusion requests submitted to the USTR from 2018 to 2020, falling across our lists of tariffs.Footnote

35

We use the letter

![]() $i$

to denote a given exclusion request and the letter

$i$

to denote a given exclusion request and the letter

![]() $f$

to denote firms in our data (e.g., for firm-level variables).

$f$

to denote firms in our data (e.g., for firm-level variables).

For our outcome variable, we examine whether the exclusion request was granted by the US government. We call this variable

![]() ${\rm{Exclusiongrante}}{{\rm{d}}_i}$

.Footnote

36

This variable is

${\rm{Exclusiongrante}}{{\rm{d}}_i}$

.Footnote

36

This variable is

![]() $1$

if the exclusion request was granted and

$1$

if the exclusion request was granted and

![]() $0$

if it was denied. In our data, 6817 exclusion requests were granted across the four lists, an overall rate of 12.9%. The rate of exclusion request granting goes down across the lists, with 33.8% and 37.9% granted on the first two lists (1 and 2), but only 4.9% and 6.5% granted on the second two lists (3 and 4A).

$0$

if it was denied. In our data, 6817 exclusion requests were granted across the four lists, an overall rate of 12.9%. The rate of exclusion request granting goes down across the lists, with 33.8% and 37.9% granted on the first two lists (1 and 2), but only 4.9% and 6.5% granted on the second two lists (3 and 4A).

For our main explanatory variable, we need to ascertain whether a requesting firm (or association) lobbied on the Section 301 tariffs. To do so, we proceeded in five steps. First, we downloaded and merged the bulk lobbying data supplied by OpenSecrets.org.Footnote 37 Second, we subsetted the data to only lobbying reports on the issue areas of “Trade” or “Tariffs” and covering only the years 2018–20. Third, we created two subsets of the data as a preliminary screen for lobbying on the Section 301 China tariffs. In a first “Section 301 tariffs” subset, we included any lobbying report with a clear or likely mention of the Section 301 tariffs within the specific issue section of the report, where lobbiers may provide detailed information about bills and policies on which they are lobbying.Footnote 38 This yielded 2147 reports that potentially included lobbying on Section 301 tariffs. In a second “China trade” subset, we included any report where “China” was mentioned in the specific issue section, yielding 3076 reports that potentially include lobbying on Section 301 tariffs (though we expected that many of these reports would not relate to the Section 301 tariffs since firms lobby on many China-related issues). Fourth, we did a thorough human-coder screen of each lobbying report in the two subsets, reading the specific issue section to see if there is clear evidence of lobbying on Section 301 tariffs.Footnote 39 We found that 1977 of 2147 of the “Section 301 tariffs” reports were in fact about the China trade war tariffs and 1724 of the 3076 “China trade” reports were about the Section 301 tariffs. Finally, we matched our lists of firms lobbying on Section 301 tariffs to the set of firms that filed exclusion requests.

We call our main variable Lobbied

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}_f}$

which is a dummy variable that equals 1 when a given firm requesting exclusion reported lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs. A primary concern with this variable is that some lobbiers do not fill in the specific issue section or do so tersely, and so may have lobbied on the Section 301 tariffs but did not record any evidence of that on their lobbying reports. We outline a strategy below to assess the sensitivity of our main findings to this potential undercounting problem, particularly if the undercounting is correlated with the success of exclusion requests. We show there that our main conclusions are robust to even the most pathological mismeasurement.

${{\rm{\;}}_f}$

which is a dummy variable that equals 1 when a given firm requesting exclusion reported lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs. A primary concern with this variable is that some lobbiers do not fill in the specific issue section or do so tersely, and so may have lobbied on the Section 301 tariffs but did not record any evidence of that on their lobbying reports. We outline a strategy below to assess the sensitivity of our main findings to this potential undercounting problem, particularly if the undercounting is correlated with the success of exclusion requests. We show there that our main conclusions are robust to even the most pathological mismeasurement.

Design and controls To ascertain the impact of lobbying on policy success, we examine the predicted relationship between lobbying on Section 301 tariffs and the granting of an exclusion request holding fixed as many possible confounding factors as possible with model-based regression controls. We employ a linear probability model for our regression model, rather than logistic or probit regression, to accommodate our fixed effects.Footnote 40 Our main statistical model is:

The vector

![]() ${{\bf{x}}_i}$

represents all request-level, firm-level, and industry-level controls including list and industry fixed effects (described below); the vector

${{\bf{x}}_i}$

represents all request-level, firm-level, and industry-level controls including list and industry fixed effects (described below); the vector

![]() $\alpha $

is the corresponding coefficients.

$\alpha $

is the corresponding coefficients.

As potential sets of controls, we consider many alternative explanations for exclusion request success. We group these into six tranches and estimate six models where the groups of covariates are introduced sequentially. The first group of covariates is included in all models (1 through 6); the second tranche in models 2 through 6; the third group in models 3 through 6; and so on. We identify which controls are included in which models at the bottom of each table.

First, the rate of exclusion request granting differs sharply across tariff lists. For this reason, we include in all statistical models a separate intercept for each list, i.e., a list fixed effects. In the tables, we refer to these intercepts as “List FEs.”Footnote 41

Second, exclusion request success may be a product of general political engagement whether through lobbying or campaign contributions. Therefore, it is important to measure firms’ non-Section 301-related trade lobbying expenditures and their campaign contributions to Republican party candidates and Democratic party candidates. The lobbying variable is measured as a dummy (in analogy with our main explanatory variable),Footnote 42 while the amount of campaign contributions are added to one and logged. In the tables, we refer to these variables as “Lobby/PAC controls.”

Third, exclusion request success may have depended on technical criteria requested by the USTR. The USTR asked requesters to report the HS code of the product they were requesting for exclusion. A very small minority of companies submitted requests for tariff codes that were not actually present on the list of covered products. We expect these requests to be denied, and so include a dummy variable which equals 1 if the requested exclusion code actually is a part of the relevant list. Requesters also supplied information on their relationship to the imported product (in categories of “importer,” “purchaser,” “US producer,” “trade association,” “other”); whether the imported product was a final product or an input (or “not sure”); and perhaps most importantly, whether the product was available for import from third markets or available within the United States (which also contain “not sure” responses). Although not stated explicitly in the exclusion request process, we expect that the availability of the imported product in the United States or third countries will negatively impact the likelihood of getting an exclusion request granted. In the tables, we refer to these variables as “Tech. criteria controls.”

Fourth, firm-level features may have influenced the likelihood of success. Larger firms may have been more likely to get requests granted, because of their political or economic heft, or less likely, if they are viewed less sympathetically than small businesses. We measure firm size with a four-part dummy variable—small, medium, large, and very large—provided by Orbis. This is the only measure of size available for private US firms (who account for a significant majority of exclusion requesters).Footnote 43 US businesses which are multinationals, especially ones that own subsidiaries in China, may particularly have been viewed less favorably, and foreign firms may also have been treated differently than US firms. So we control for dichotomous measures of US nationality, ownership of a Chinese subsidiary, and ownership of any non-China foreign subsidiary.Footnote 44 We also include in this tranche of controls a count of the number of exclusion requests that were filed for the tariff line mentioned in the exclusion request, since tariff exclusions could be requested by multiple firms. In the tables, we refer to these variables as “Firm-level controls.”

Fifth, a recent literature emphasizes the role of political geography arguing that firms located in swing states may have been given preferable treatment.Footnote 45 We measure this, and also whether firms in clearly Trump-supporting states received favorable treatment, using cutoffs of within 5% of even voting for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in 2016 as a proxy for “swing states,” and a cutoff of greater than 5% vote differential for Trump to measure “Trump states.” In the tables, we refer to these variables as “State political controls.”

Sixth, we also control for a set of characteristics which rely on the measurement of firms’ industries and trade flows.Footnote 46 Firms in heavily import-competing or exporting industries may have been treated differently, so we control for industry-level logged exports and imports. Due to greater economic distortions, firms producing products with large (absolute) import elasticities of substitution may have been more likely to be granted exclusion.Footnote 47 Therefore, we control for a measure of import elasticity of substitution from Fontagné et al. (Reference Fontagné, Guimbard and Orefice2022). We also include NAICS 3-digit industry fixed effects to account for remaining unmeasured industry-specific factors. Firm differences resulting from self-selection into the exclusion process might also affect our results. Of course, all the controls specified earlier for firm, request, and political features will help to hold constant factors that drive selection. But we also estimate the probability of seeking exclusion using a probit version of a model developed in Lee and Osgood (Reference Lee and Osgood2022). From this model, we calculate the inverse Mills ratio which we include as an additional control (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979). In the tables, we refer to these variables as “Trade and ind. controls/FEs.”

Trade lobbying works

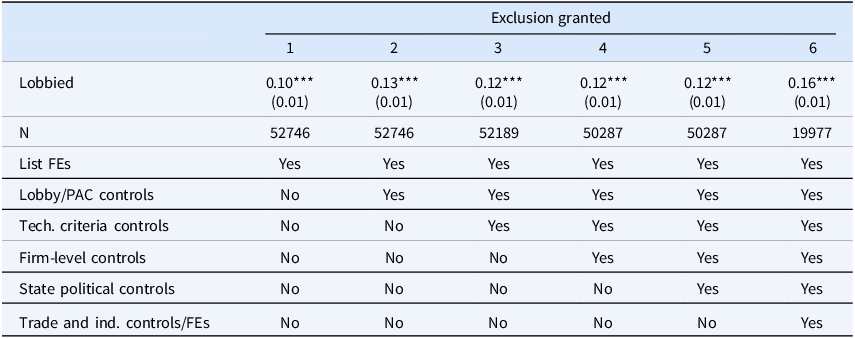

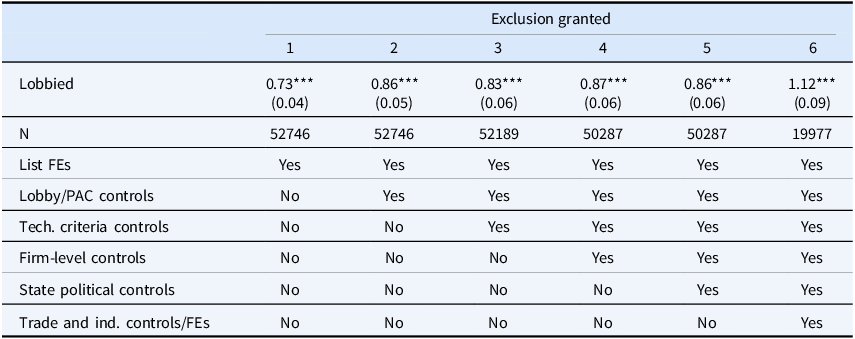

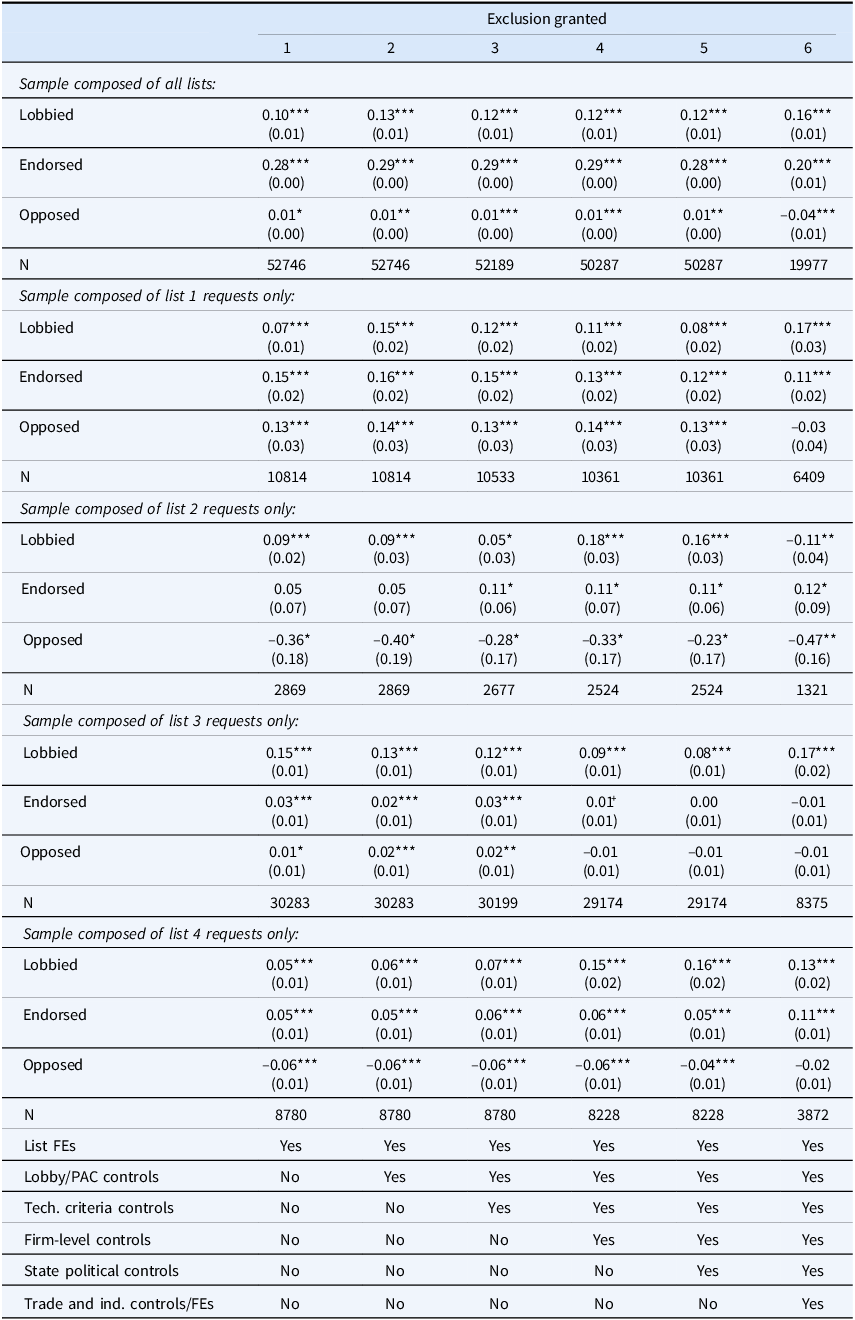

Is trade lobbying effective? We present the results of our main analysis on this question in Table 1.Footnote

48

To begin, the coefficient on the Lobbied variable with only the list intercepts included is

![]() $.10$

. Since we employ a linear probability model, this means that lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs is associated with a 10% higher percentage chance of receiving exclusion from the tariffs. Across the different sets of covariates which we sequentially introduce, the overall effect estimates are similar in scale, ranging from 10% to 16%.Footnote

49

$.10$

. Since we employ a linear probability model, this means that lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs is associated with a 10% higher percentage chance of receiving exclusion from the tariffs. Across the different sets of covariates which we sequentially introduce, the overall effect estimates are similar in scale, ranging from 10% to 16%.Footnote

49

Table 1. Main tests of whether lobbying works

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Given that only 12.9% of exclusion requests are granted in our data, these effect estimates are remarkably large in relative terms. Lobbying for exclusion is doubling or more than doubling the chance of earning exclusion for a given request. But of course, this is also an effect that is limited in absolute terms—lobbying for exclusion still grants a predicted effect of success in the range of 20–30%, much less than even odds. Lobbying works, but is not a guarantee of policy success.

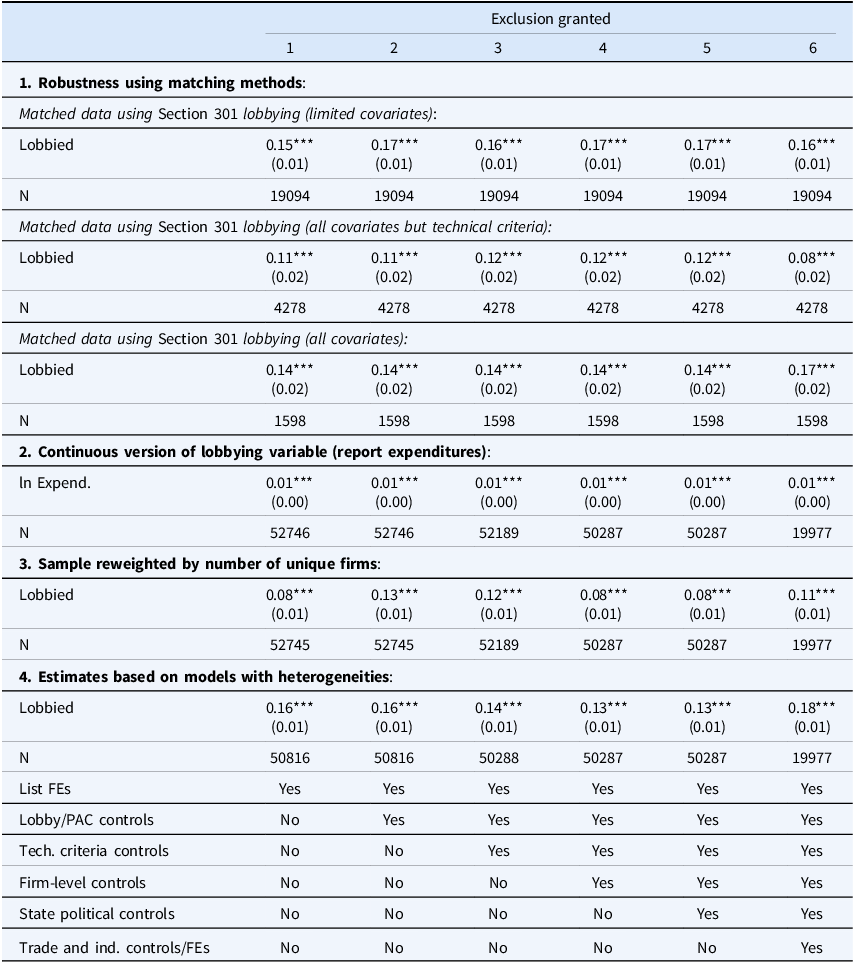

We examine the robustness of our main findings in five robustness checks in Tables 2 and 3. First, we examine our results in three matched datasets. Matching is valuable in providing additional non-parametric control for confounders that are included in our regression models as linear additive controls only. Matching can also ameliorate a lack of overlap in the covariate space between treated (lobbying) and control (non-lobbying) units. For these reasons, we match treated units with similar controls to prune and reweight our data. Since we have mainly dichotomous or categorical controls, but also a few continuous controls, we employ coarsened exact matching.Footnote

50

We use three different sets of variables to produce three matched datasets for analysis. One uses a limited covariates matched dataset where we exact match only the list, non-Section 301 trade lobbying, firm size, US nationality, and two-digit NAICS code. Another matched dataset uses all covariates but the technical criteria (these induce a 63% drop in the matched sample size and explain only very limited variance). A final matched dataset uses all of the covariates including the technical criteria. For each matched dataset, we also employ the exact same control variables as used in the regression models in Table 1. Within the matched datasets, we always find a positive and statistically significant effect of lobbying on receiving exclusion (see part 1 of Table 2). This effect is very similar to the estimate in the complete data, mostly ranging from

![]() $.11$

to

$.11$

to

![]() $.17$

.

$.17$

.

Table 2. Robustness checks for whether lobbying works

Notes: Models in groups 2 and 4 are OLS. Models in group 1 are weighted OLS employing the matching weights; models in group 3 are weighted OLS with observations reweighted so that each firm counts as one observation. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Table 3. Lobbying effectiveness across lists

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

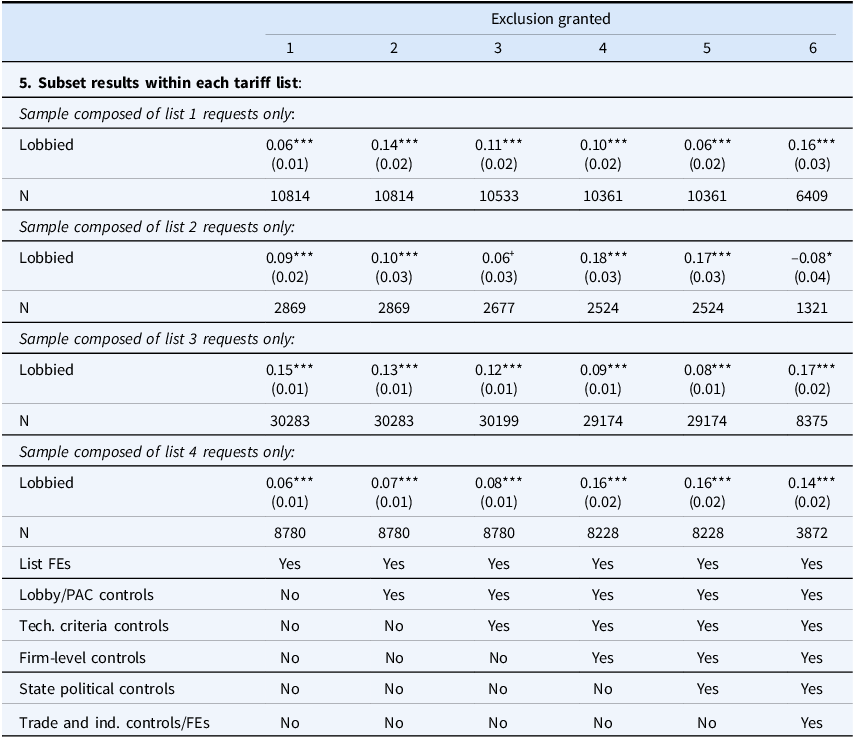

Second, using a continuous version of the lobbying variable which is the (logged) amount of expenditures on lobbying reports that mention Section 301, we find that greater lobbying amount is associated with a greater probability of earning exclusion. Third, we examine an alternative formulation of the data where we reweight the number of observations by the number of unique firms since some firms filed more than one exclusion request. The estimates are again consistently positive and statistically significant. Fourth, anticipating our modeling of heterogeneous effects of lobbying as a function of firm size and multinationality in the next section, we fit an interaction model and then estimate an average treatment effect using that model’s estimates. We see similar effect sizes ranging from

![]() $.13$

to

$.13$

to

![]() $.18$

. Finally, in Table 3 we examine our models within each of the four lists, since the nature of the industries covered and the rate of exclusion granting changed across the lists. Remarkably, we find that our main results are nearly identical across all of the specifications within each of the lists.Footnote

51

The sole exception occurs in model 6 for list 2 where the introduction of the industry and trade variables turns the lobbying effect negative. Since list 2 had by far the smallest amount of exclusion requests, and the industry-level covariates further reduced the size of the data, we view this as anomalous.

$.18$

. Finally, in Table 3 we examine our models within each of the four lists, since the nature of the industries covered and the rate of exclusion granting changed across the lists. Remarkably, we find that our main results are nearly identical across all of the specifications within each of the lists.Footnote

51

The sole exception occurs in model 6 for list 2 where the introduction of the industry and trade variables turns the lobbying effect negative. Since list 2 had by far the smallest amount of exclusion requests, and the industry-level covariates further reduced the size of the data, we view this as anomalous.

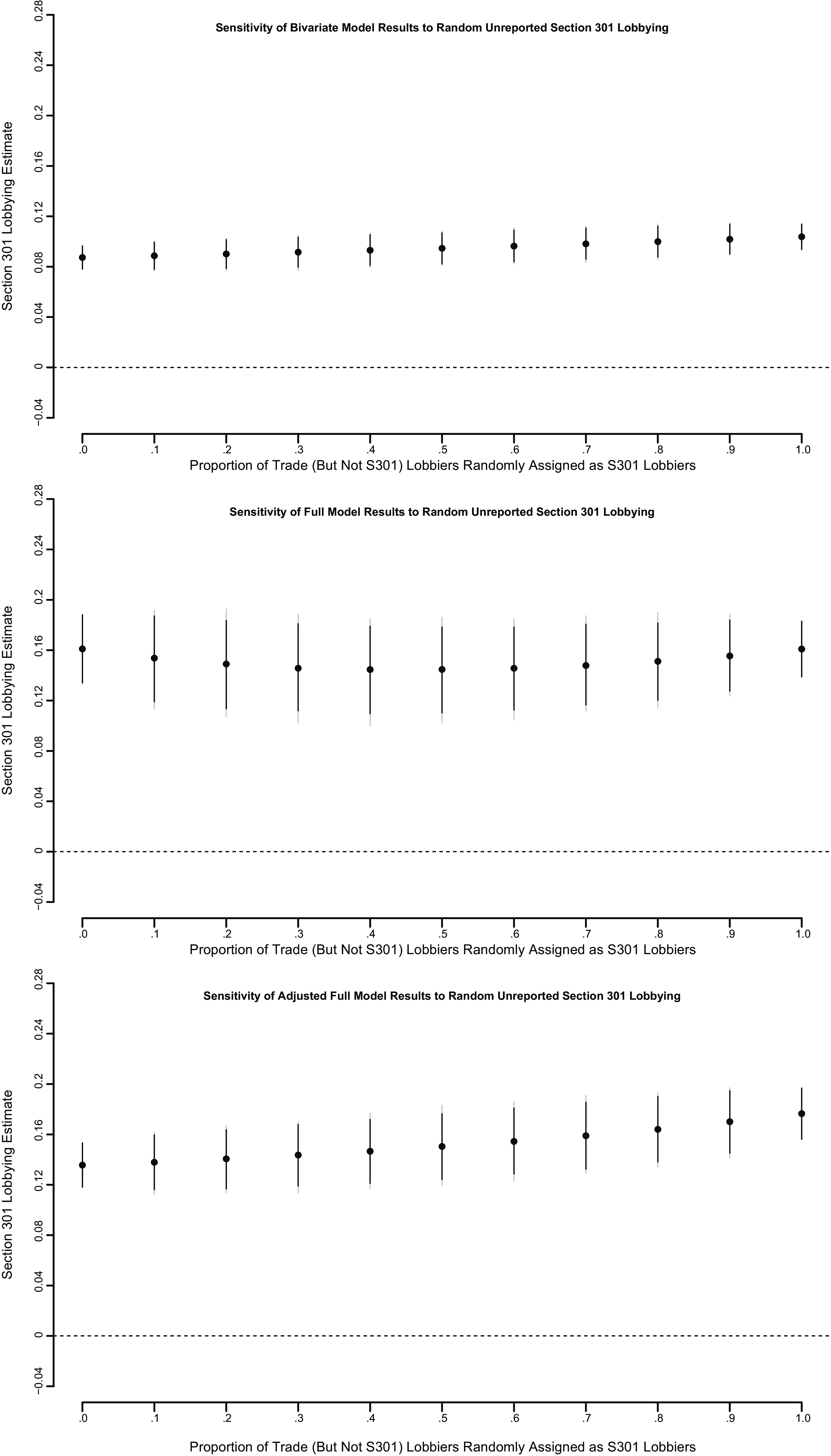

As mentioned earlier, one potential issue with our measure of lobbying is that it cannot capture lobbying on Section 301 which goes unmentioned in the “specific issue” fields of firms’ lobbying reports. To examine whether our findings might be vulnerable to undercounting, we conducted two simulation exercises. First, we examined whether our main findings might be sensitive to completely random unreported Section 301 lobbying. To do so, we randomly choose a share of firms that lobbied on trade (but not Section 301 per our measurement) and assigned them as being in fact Section 301 lobbiers. We simulated proportions from

![]() $.1$

all the way up to

$.1$

all the way up to

![]() $1$

. We conduced these simulations in our bivariate model, our full model (model 6), and an adjusted model 6 which drops our non-Section 301 trade lobbying measure (since that will be highly correlated with Section 301 lobbying as the proportion of undercounted Section 301 lobbying goes to

$1$

. We conduced these simulations in our bivariate model, our full model (model 6), and an adjusted model 6 which drops our non-Section 301 trade lobbying measure (since that will be highly correlated with Section 301 lobbying as the proportion of undercounted Section 301 lobbying goes to

![]() $1$

). Across these simulations, we find average results that are almost exactly aligned with our main findings.

$1$

). Across these simulations, we find average results that are almost exactly aligned with our main findings.

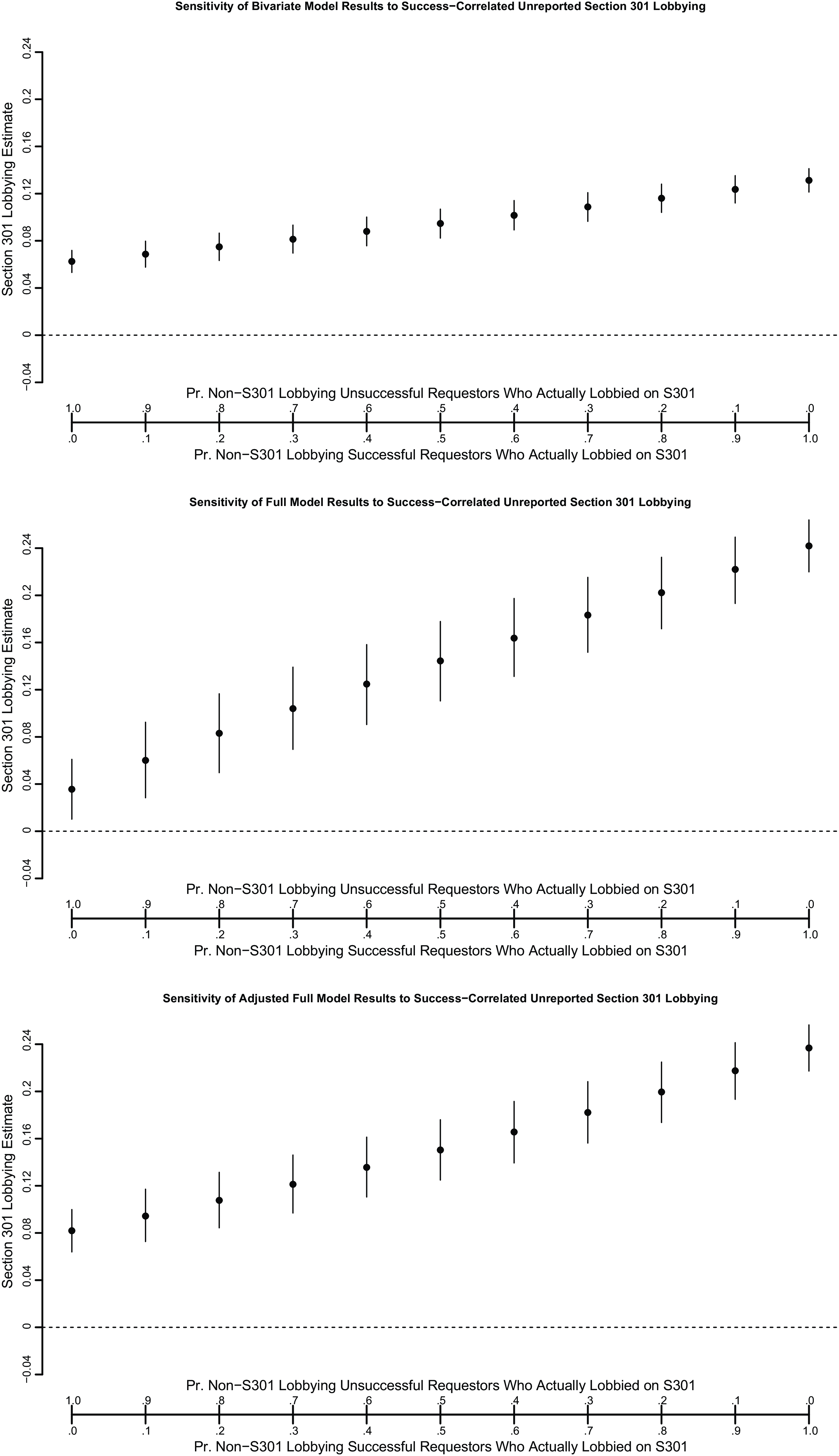

Second, we examined whether our main findings might be vulnerable to unreported Section 301 lobbying that is correlated with receiving exclusion. To this end, we simulated the following: imagine that

![]() $x$

proportion of unsuccessful requesters measured as non-lobbiers were in fact lobbiers; while

$x$

proportion of unsuccessful requesters measured as non-lobbiers were in fact lobbiers; while

![]() $1 - x$

proportion of successful requesters measured as non-lobbiers were in fact lobbiers. If

$1 - x$

proportion of successful requesters measured as non-lobbiers were in fact lobbiers. If

![]() $x$

is low, that would mean the findings in our paper should be biased downwards; if

$x$

is low, that would mean the findings in our paper should be biased downwards; if

![]() $x$

is high, our findings should be biased upwards. We consider values of

$x$

is high, our findings should be biased upwards. We consider values of

![]() $x$

from

$x$

from

![]() $0$

to

$0$

to

![]() $1$

and use the same three models as those described above. Remarkably, even with the most pathological forms of missing data—

$1$

and use the same three models as those described above. Remarkably, even with the most pathological forms of missing data—

![]() $x = 1$

, for example, which is highly, highly implausible—we still find a positive and significant effect of lobbying on receiving exclusion. And since that is a highly unlikely circumstance, we are confident that our main conclusions are totally robust to unreported Section 301 lobbying.

$x = 1$

, for example, which is highly, highly implausible—we still find a positive and significant effect of lobbying on receiving exclusion. And since that is a highly unlikely circumstance, we are confident that our main conclusions are totally robust to unreported Section 301 lobbying.

Overall, the findings exhibit remarkable consistency across various samples and approaches. Evidently, lobbying for relief from the Section 301 tariffs imposed on Chinese imports was effective in the sense of providing a consistently higher probability that relief would be granted by the USTR, though far from a guarantee. This setting therefore provides clear evidence that lobbying for specific trade policies leads to a greater chance of securing those policies. In this instance, trade lobbying works. Future scholarship should attempt to replicate this finding using other trade policies where both lobbying and lobbying success can be clearly defined and measured.

Trade lobbying works for big firms

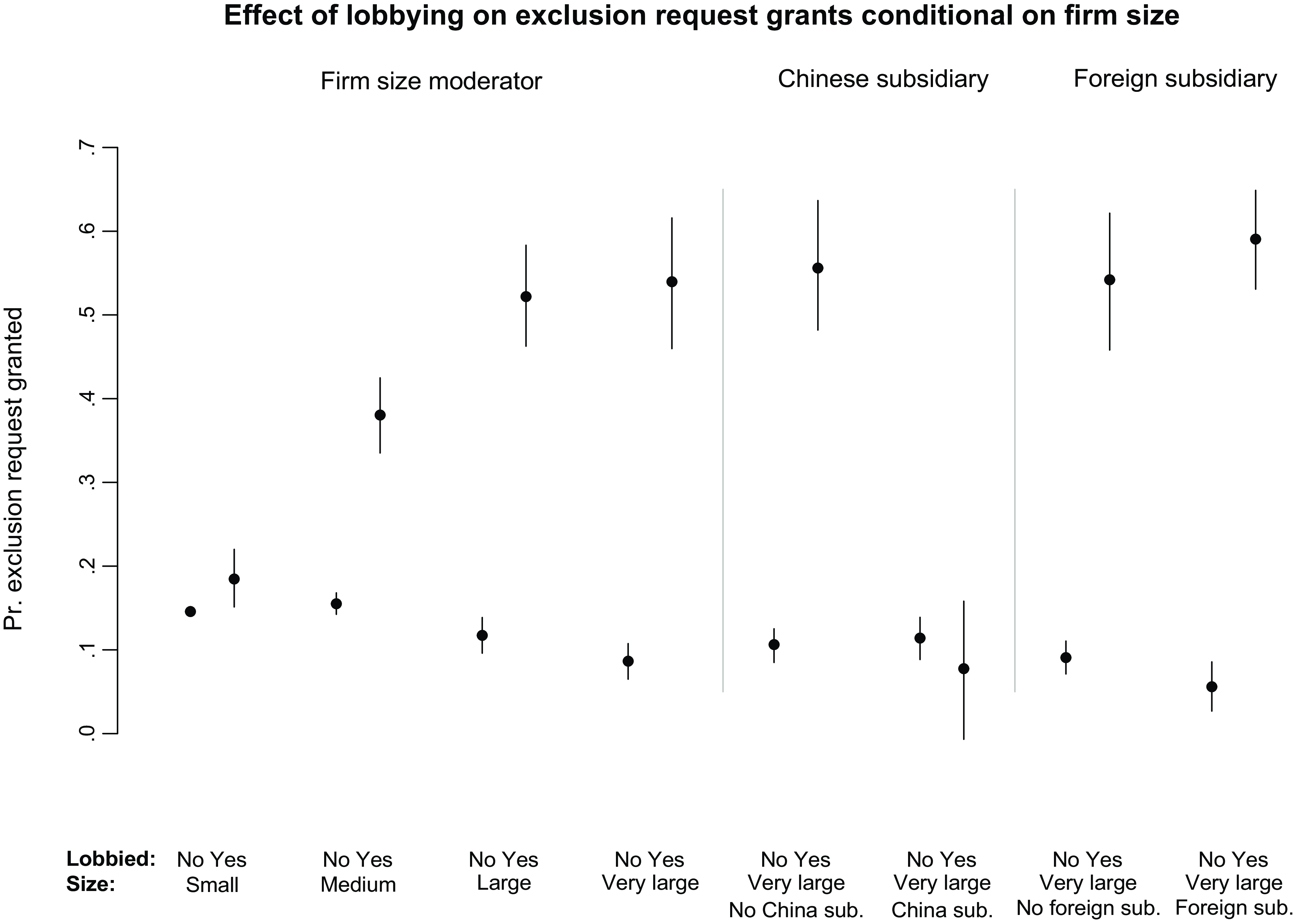

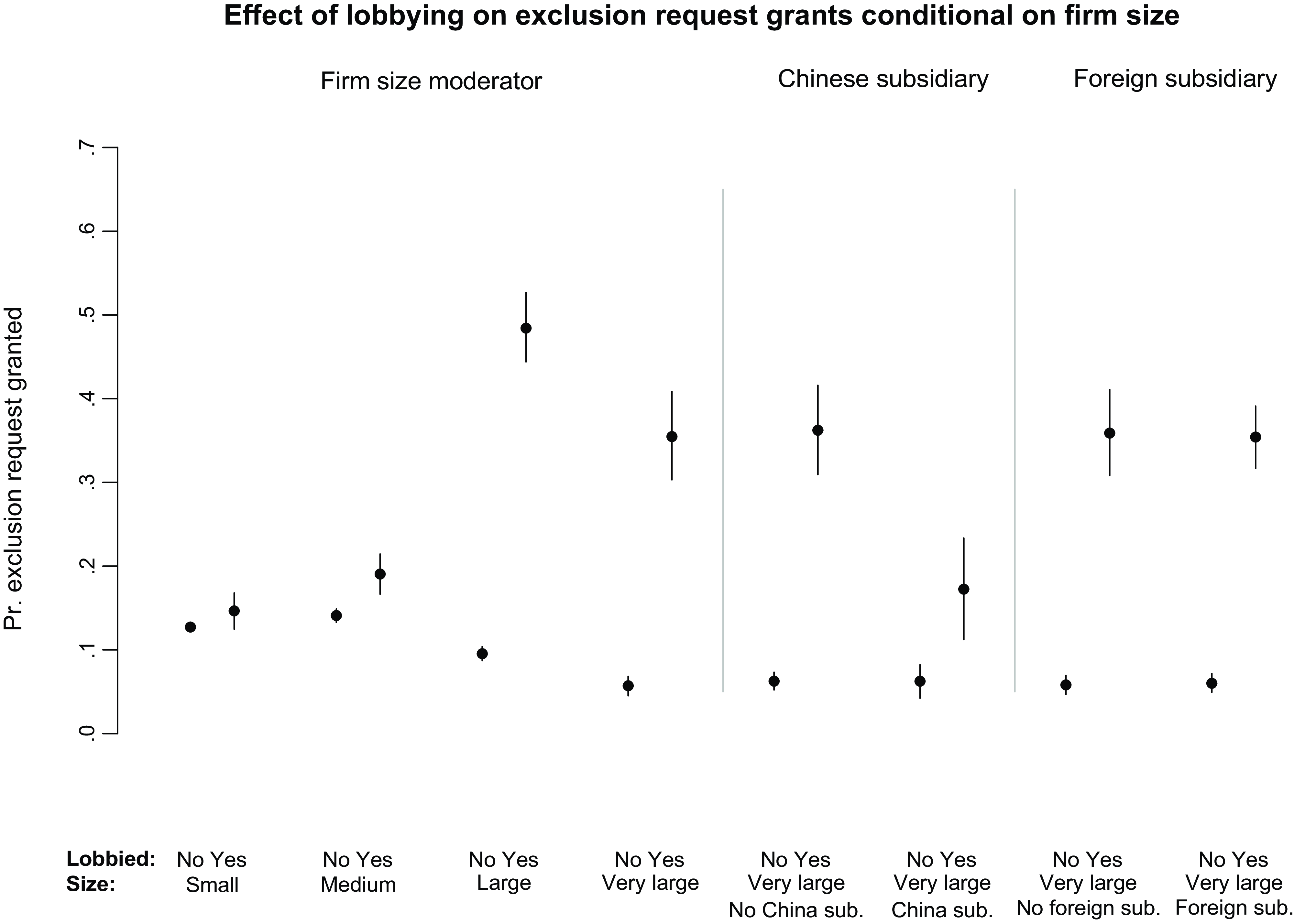

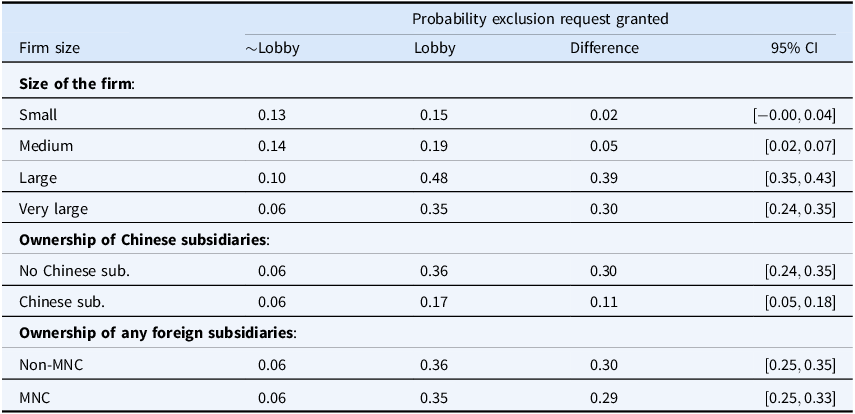

Firm size, Chinese subsidiaries, and the lobbying effect: We now turn to our second hypothesis, that trade lobbying should be particularly effective for larger firms, and our third hypothesis, that firms with Chinese subsidiaries will be disfavored even if they lobby. To do so, we fit a revised version of our most complete model which is specification 6 from Table 1:

Note that lower order terms for the size and subsidiary variables are already contained in

![]() ${{\bf{x}}_i}$

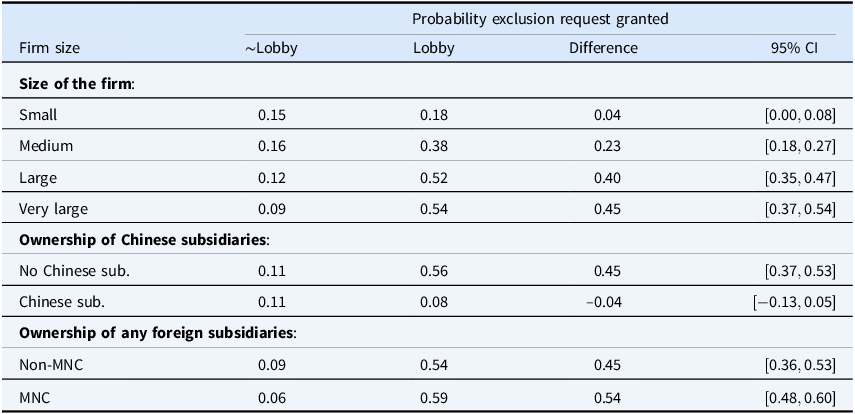

. We use this model to simulate the effect of lobbying on the probability of gaining exclusion, and we present our results visually in Figure 1 (to illustrate the size and nature of the effects) and in Table 4 (where formal statistical tests are reported).

${{\bf{x}}_i}$

. We use this model to simulate the effect of lobbying on the probability of gaining exclusion, and we present our results visually in Figure 1 (to illustrate the size and nature of the effects) and in Table 4 (where formal statistical tests are reported).

Figure 1. Heterogeneity of lobbying effects.

Table 4. Simulated effects of lobbying from interaction models

Notes: All expected outcomes and confidence intervals are created using medians, and 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles, respectively. The model is identical to model 6 in Table 1 but with

![]() $Lobbie{d_f}$

interacted with the three firm size dummies, and dummies for ownership of a Chinese subsidiary and of any subsidiary. ***

$Lobbie{d_f}$

interacted with the three firm size dummies, and dummies for ownership of a Chinese subsidiary and of any subsidiary. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

, **

$p \lt 0.001$

, **

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

, *

$p \lt 0.01$

, *

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

In line with Hypothesis 2, we find a large impact of firm size on lobbying effectiveness. Among small firms, lobbying leads to only a small increase in predicted success in gaining exclusion, about 4%. Among medium-sized firms the effect is notably larger, but the effect really jumps for large firms, for whom lobbying increases the percentage chance of success by a huge 40%. Among very large firms, lobbying increases the percentage chance of success by 45%. These are startlingly large estimated effects of lobbying efficacy for this subset of firms. We note two points on these findings. First, the positive effect of lobbying on exclusion success is statistically significant for medium, large, and very large firms (as seen in Table 4), but not for small firms. Second, the sample in these models includes only goods-producing firms since we include all trade and industry-related variables. When we omit these variables except for the fixed effects so that we can include services firms, we see the same pattern of statistical significance: lobbying has no positive effect for small firms, but a significant positive effect for medium, large, and very large firms. The effects for large and very large firms are

![]() $39{\rm{\% }}$

and

$39{\rm{\% }}$

and

![]() $30{\rm{\% }}$

, respectively [see Appendix A].Footnote

52

$30{\rm{\% }}$

, respectively [see Appendix A].Footnote

52

We investigate the moderating effect of ownership of Chinese subsidiaries in the lower half of Table 4 and the right hand side of Figure 1. Note that for purposes of simulating the expected outcomes, we assume that the firm is very large. We do this because within our sample ownership of Chinese subsidiaries is heavily concentrated within very large firms. 32% of Very large firms requesting exclusion own a subsidiary in China. Within the three other size groups, these figures are all much, much lower. For example, less than 2% of large firms own Chinese subsidiaries and virtually no small or medium-sized firms do.

A very large firm without a Chinese subsidiary that lobbied for exclusion increased its chances of earning exclusion by 50% in absolute terms, a huge margin. The effect of lobbying for firms with Chinese subsidiaries is essentially zero. We see similar findings—firms with Chinese subsidiaries are disfavored even if they lobby—in the larger sample omitting the trade and industry variables, though the lobbying effect sizes are less overwhelmingly large (

![]() $30{\rm{\% }}$

for firms without a Chinese subsidiary and

$30{\rm{\% }}$

for firms without a Chinese subsidiary and

![]() $11{\rm{\% }}$

for firms with a Chinese subsidiary). Although differing somewhat in the size and starkness of the effects, all of these estimates strongly support Hypothesis 3.

$11{\rm{\% }}$

for firms with a Chinese subsidiary). Although differing somewhat in the size and starkness of the effects, all of these estimates strongly support Hypothesis 3.

We summarize our findings as follows: the effectiveness of lobbying in securing exclusion requests is larger for medium, large, and very large firms than it is for small firms. The size of this differential effect seems to be increasing in firm size, at least up to the large category. And the largest firms’ lobbying is remarkably effective, tripling or even quadrupling the likelihood of earning exclusion. We refer to this finding as a “size premium” in lobbying effectiveness. We also see evidence that ownership of a Chinese subsidiary makes lobbying less impactful for firms, overwhelmingly so among goods-producing firms but also in a sample including all exclusion requesters. We call this exception to the size premium the “China penalty.”

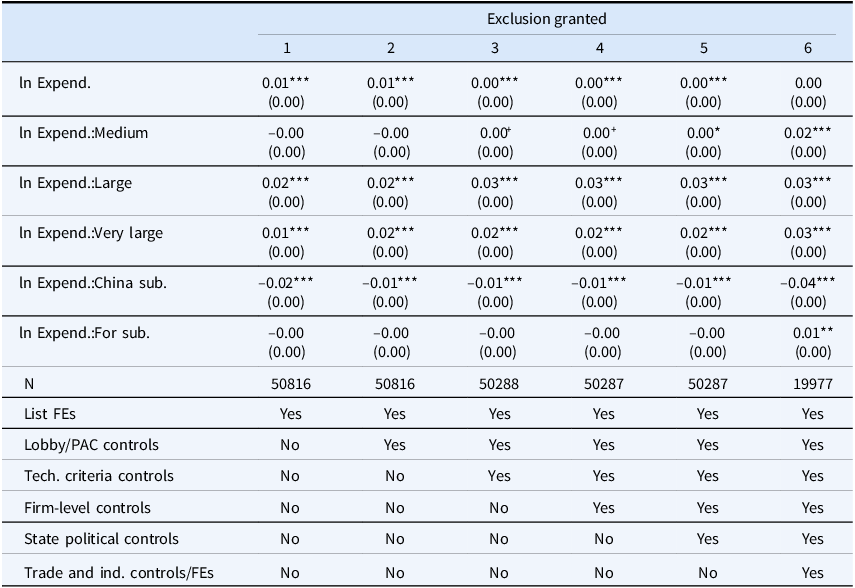

Exploration of mechanisms: Why do larger firms experience more success when they lobby? We explore several mechanisms developed above: on larger firms’ greater impact on the economy, ability to offer quid pro quos, exit options, and lobbying behaviors.

We first reemphasize a striking pattern in our findings: larger firms are more effective lobbiers than smaller firms, but firms with Chinese subsidiaries are a significant exception to that rule. Evidently, policymakers were singling out firms invested in China for worse treatment. These findings concord with a longstanding idea in the literature: large firms are more influential because of their greater footprint in the economy.Footnote 53 When considering the prospects for reelection, the executive branch is concerned with national growth and employment. Providing policy wins to larger corporations, especially those with a greater role in the US economy but not overseas, is a straightforward way to allocate limited policy concessions.

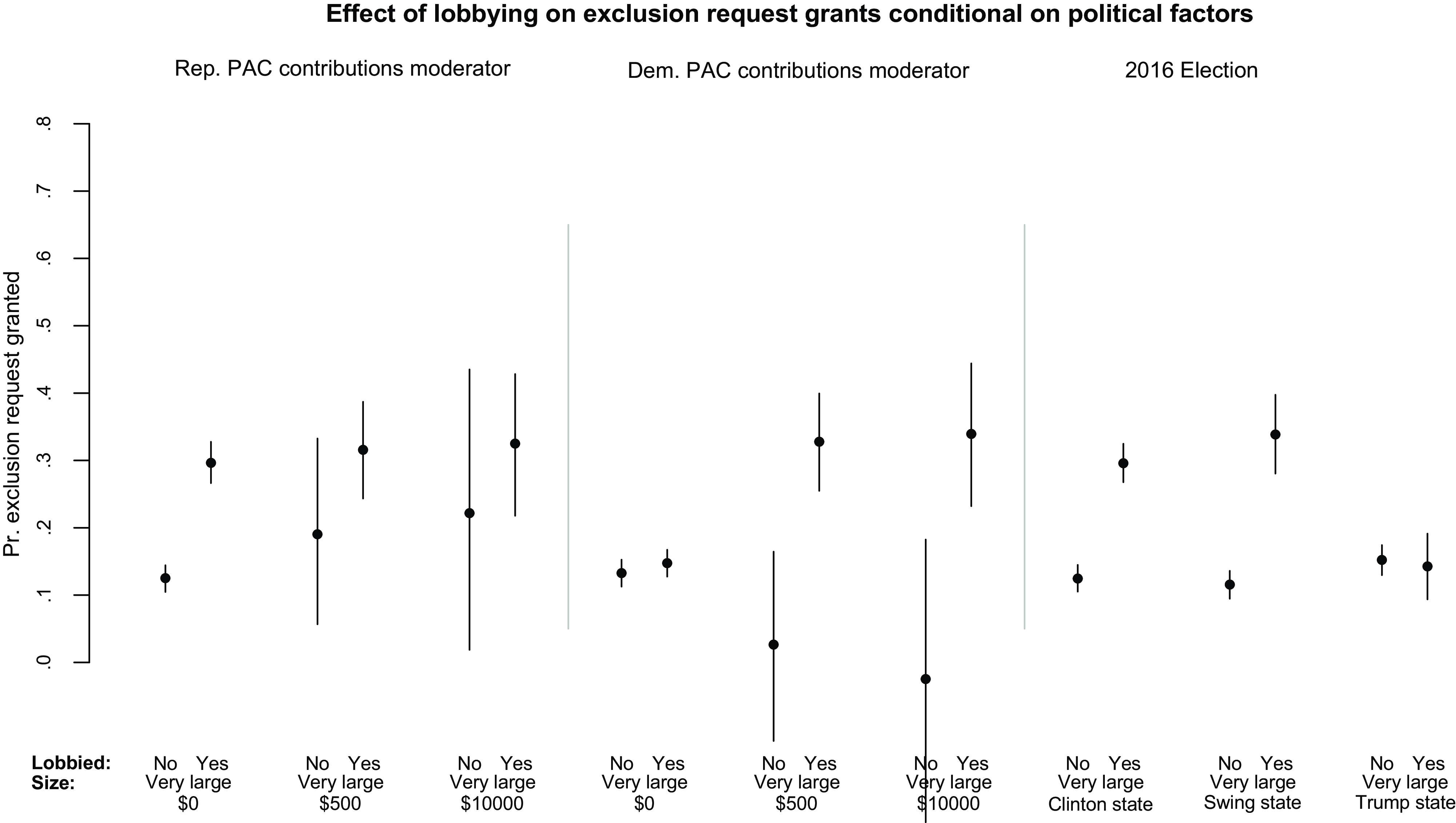

To investigate campaign contributions as quid pro quos, we examined a separate model where we interacted firm lobbying with measures of campaign contributions to Republicans and also to Democrats (See Appendix Figure A4.) Since a Republican held the executive branch during the period we examine, the most plausible form of political bias would manifest as preferential treatment toward firms that contribute a lot to Republican candidates. We do not observe any such bias. We also find no evidence that firm location—whether a Clinton state, swing state, or Trump state in 2016—strongly influences lobbying effectiveness. Firms from Trump states seem to be somewhat disfavored; firms from swing states are no more favored than firms from Clinton states.

Our focus in Figure 1 on the ownership of subsidiaries in China or elsewhere helps us to rule out another explanation, that firms with more exit options are able to extract better policy. We see no differential effect within our data that multinationals are more successful in obtaining preferred policy outcomes and firms with subsidiaries in China get substantially worse treatment. While it may be that large firms are more effective lobbiers in other situations owing to their exit options, that does not seem to be the case here.

We also do not find a strong pattern whereby larger firms lobby in a categorically different fashion in terms of expenditures or numbers of requests. Small, medium, and large firms that lobbied on Section 301 tariffs reported roughly the same amount of expenditures on the lobbying reports on average, while very large firms reported noticeably larger average expenditures. Since the effect of firm size is operative for medium and large firms we do not think the amount of reported expenditures is driving the size premium. Likewise, we do not find a consistent relationship between firm size and the number of exclusion requests. (Our results interacting firm size with lobbying expenditures from above confirm this.) Note also that an increased number of requests actually reduces the chances of exclusion on any given request, so regulators were apparently not rewarding firms that made more requests.

We are left with two consistent patterns in the data and three non-patterns. Larger firms’ lobbying tends to have a greater impact than that of smaller firms, however, an important exception is firms with Chinese subsidiaries, who are mostly very large, but are much less likely to receive exclusion requests even if they lobby. The effect of firm size on lobbying success does not seem to be driven by overtly political factors; by the credibility of threats to exit; or by different patterns in lobbying expenditures or the number of requests. Collectively, these patterns are most consistent with a theory that policymakers considered the broad impacts of firms on the American economy and workers when doling out exceptions to the Trump China tariffs.

Conclusion

We discuss our three core findings along with prospects for future research. First, trade lobbying works for firms, though imperfectly. Up to now, the trade lobbying literature lacked a clear demonstration that lobbying for specific and clearly defined policies succeeds in securing those policies.Footnote 54 Our application is requests for exclusion from trade war tariffs; scholars ought to track down other policies to further test this claim. Second, large firms benefit from a substantial size premium in their lobbying effectiveness. This is not because of their campaign contributions or outside options, but rather seems to be because of their larger contributions to the US economy.Footnote 55 Scholars ought to replicate our approach to see if size is beneficial in other settings. Third, US firms with Chinese subsidiaries face a substantial penalty in their lobbying effectiveness. This concords with our interpretation that the size-lobby effectiveness linkage is about firms’ contributions to domestic growth and employment. Exploration of competing mechanisms in other contexts would be beneficial.

We see three broader implications of our findings for the literatures on trade politics and lobbying. First, we complement existing trade politics literature which argues that big firms (who are generally more pro-trade) are better able to lobby because of their resources, advantages in collective action, and institutional privileges.Footnote 56 Our findings are different—because we show that big firms are more successful having overcome the hurdles of engaging in lobbying—but related—since they speak to the strong influence of big corporations. Our findings also differ in showing that multinationals, which may have advantages in lobbying ability, were disadvantaged in lobbying effectiveness in this context. Thus our findings add nuance to the literature’s conclusion that trade lobbying might have significant biases toward big companies’ interests.

Second, we provide suggestive evidence on the objectives of regulators and politicians. Our findings are consistent with an interpretation that regulators used lobbying as an informational cue.Footnote 57 However, lobbying alone was insufficient for firms to earn exclusion, since many smaller firms, or firms with Chinese subsidiaries, that lobbied had their requests rejected. US-based companies that were large and lobbied, however, earned exclusion at a high rate. Regulators, it seems, took seriously a mission to minimize harm to the broader US economy while protecting the China tariff policy. Tensions in the administration’s policy aims were thus exposed. These tensions between avowed protectionists and regulators, cabinet members, and members of Congress, who are loath to impose significant costs on US firms have only intensified since the episode we examine.

Finally, it is interesting to consider what our findings mean for resurgent trade protectionism. The past 10 years have witnessed a weakening of globalization: failing trade agreements, trade wars, moribund multilateralism, and incipient decoupling from China. The origins of these changes seem to lie mainly in resurgent anti-trade ideologies, nationalism, and security competition though some industries (US steel and EVs, for example) have significant interests in protection, too. These dramatic changes are setbacks for firms that benefit from globalization, who have resisted rising protectionism but faced some very significant defeats.Footnote 58 Amidst these setbacks, our paper illustrates both the wily abilities of big American firms to resist deliberalization but also the limits to their power. To resist protectionism, pro-trade American firms may need to align their interests with the American economy and American workers to the greatest extent possible.Footnote 59 In that way, their interests will become policymakers’ interests.

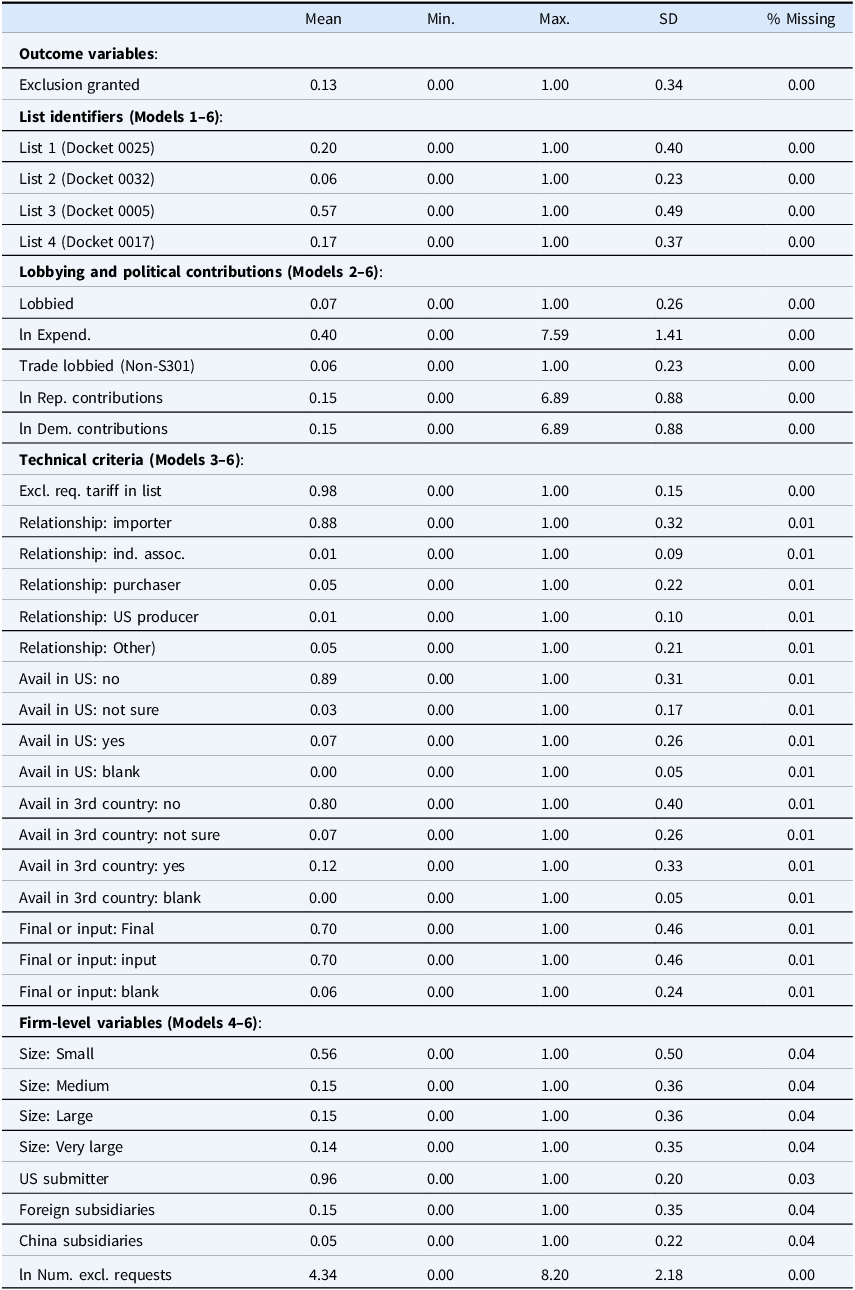

Appendix A Summary statistics

Table A1. Summary statistics (part I)

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

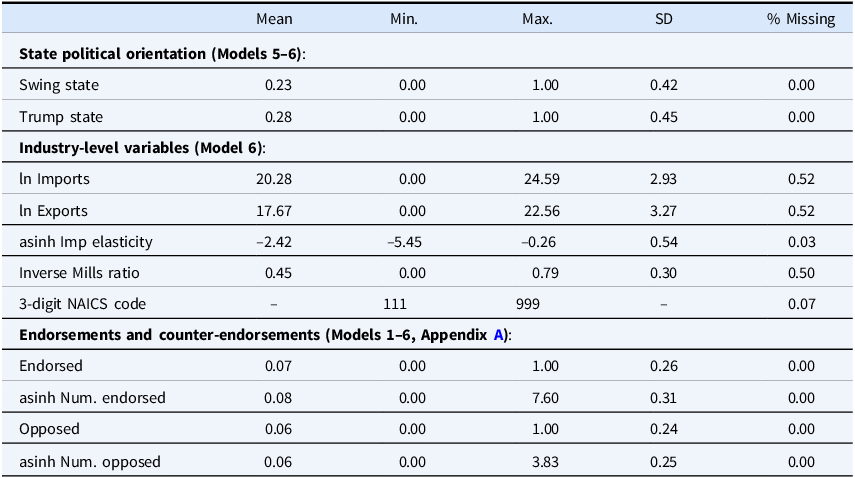

Table A2. Summary statistics (part II)

Notes: Industry-level trade variables are not available for firms outside of Agriculture (NAICS 11); Mining (NAICS 21) and Manufacturing (NAICS 31–33).

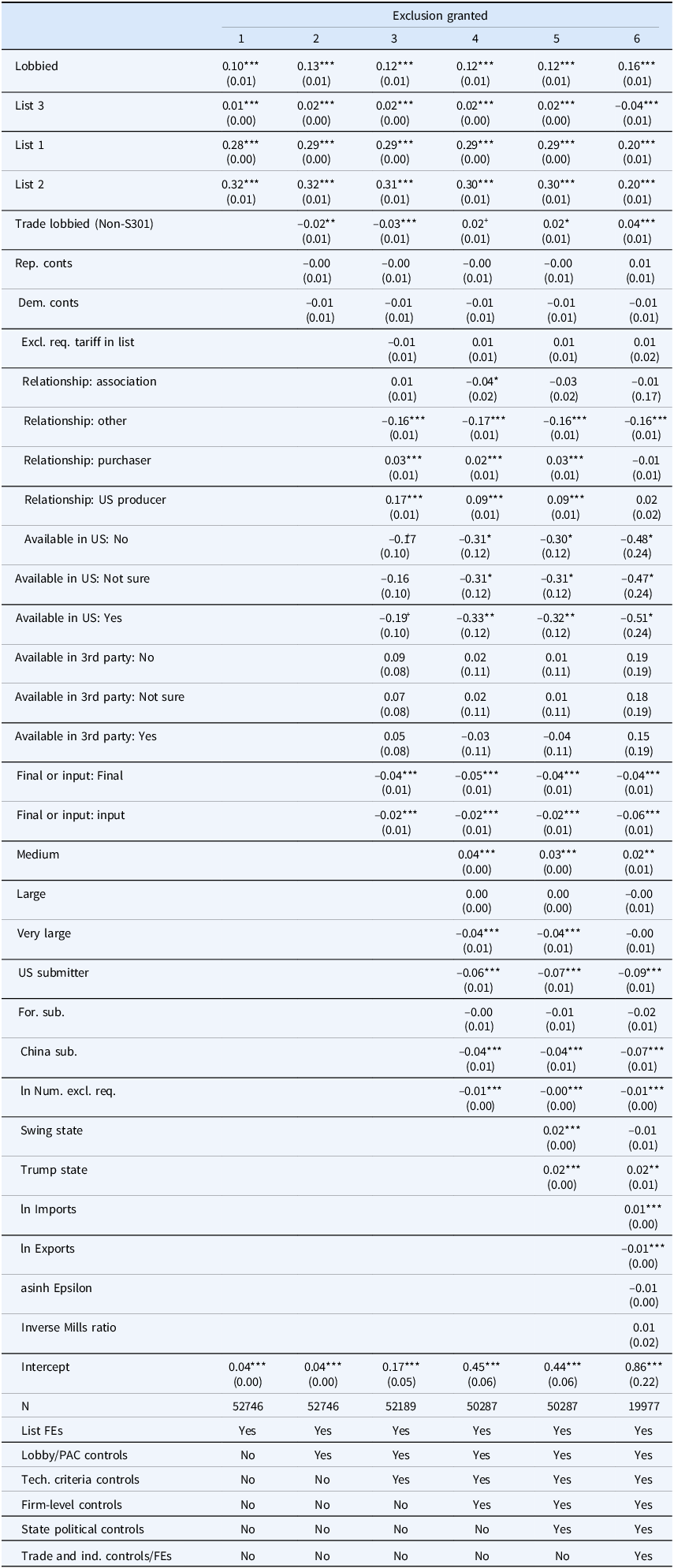

Table 1 with all covariates presented

In Table A3 we recreate Table 1 but showing the estimated coefficients for all variables but for the industry fixed effects in Model 6.

Table A3. Main tests of whether lobbying works (covariate estimates included)

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Main results using logistic regression

In Table A4 we recreate Table 1 but using a logistic regression model. We find that our main results are substantively very similar. The estimated coefficients are presented in the table. Translating from coefficients to expected outcomes, the predicted change in probabilities moving from not lobbying to lobbying in model 1 is

![]() $.082$

; for model 4 it is

$.082$

; for model 4 it is

![]() $.095$

; and for model 6 is

$.095$

; and for model 6 is

![]() $.157$

. These effects are very close to those estimated in our linear probability models.

$.157$

. These effects are very close to those estimated in our linear probability models.

Table A4. Table 1 reestimated with logistic regression models

Notes: All models are logistic regression. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

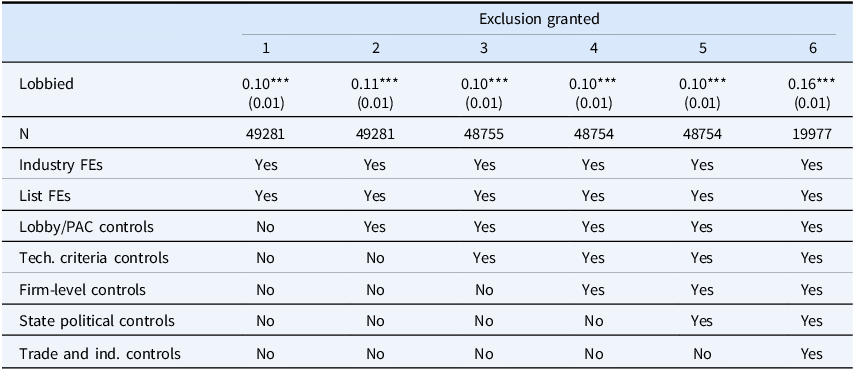

Results with industry fixed effects included in all models

In Table A5 we recreate Table 1 but included 3-digit NAICS industry fixed effects in all models. We find results that are similar in size and significant to those in the main text.

Table A5. Table 1 reestimated with industry fixed effects

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Illustration of sensitivity test results

In Figures A1 and A2 we provide the sensitivity test simulation results described in the main text. Figure A1 illustrates the impact of randomly assigning a given share (from

![]() $.1$

up to

$.1$

up to

![]() $1$

) of measured non-Section 301 lobbiers (but who lobbied on some trade issue) to Section 301 lobbiers. As noted in the main text, our measure of Section 301 lobbying is vulnerable to undercounting given that not all lobbyists fill out (or exhaustively fill out) the specific issue field of their lobbying report. This test focused on entirely random patterns of mismeasurement is focused on assessing the potential for attenuation bias.Footnote

60

In Figure A2, we examine more systematic (and so concerning) forms of mismeasurement, where unrecorded Section 301 lobbying is correlated with exclusion request success. Even with utterly implausible extreme levels of this form of bias, our main conclusion on the effectiveness of lobbying holds.

$1$

) of measured non-Section 301 lobbiers (but who lobbied on some trade issue) to Section 301 lobbiers. As noted in the main text, our measure of Section 301 lobbying is vulnerable to undercounting given that not all lobbyists fill out (or exhaustively fill out) the specific issue field of their lobbying report. This test focused on entirely random patterns of mismeasurement is focused on assessing the potential for attenuation bias.Footnote

60

In Figure A2, we examine more systematic (and so concerning) forms of mismeasurement, where unrecorded Section 301 lobbying is correlated with exclusion request success. Even with utterly implausible extreme levels of this form of bias, our main conclusion on the effectiveness of lobbying holds.

Figure A1. Sensitivity of main results to random unreported Section 301 Lobbying.

Figure A2. Sensitivity of main results to exclusion request outcome-correlated unreported Section 301 Lobbying.

Supporting endorsement and opposing counter-endorsements

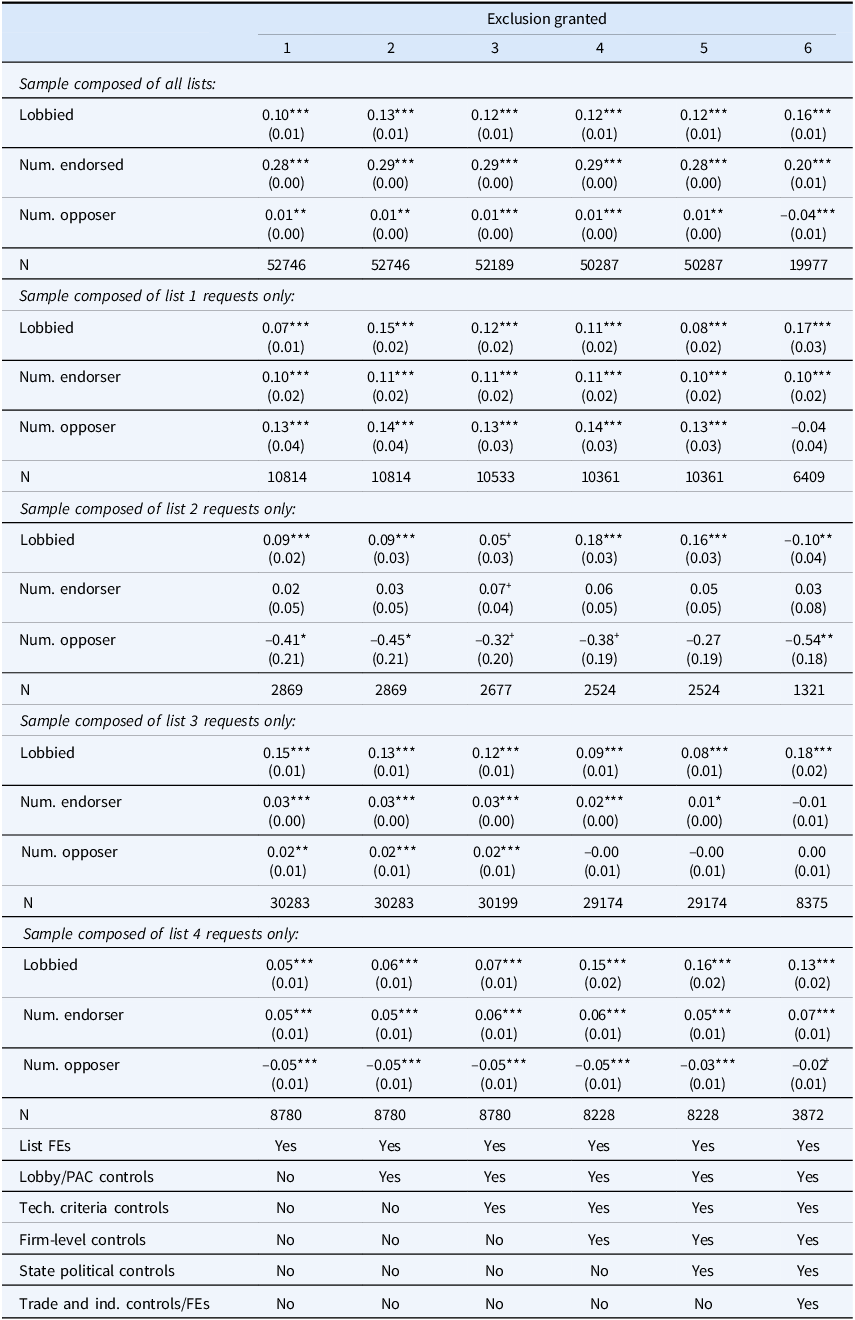

An interesting feature of the exclusion request process is that exclusion requests were made public, and stakeholders were permitted to file public comments either endorsing the request for exclusion or opposing it.Footnote 61 For example, firms sourcing similar products or trade associations could publicly post a comment supporting a company’s request for exclusion. Domestic producers or their associations also filed public comments opposing exclusions, as did some NGOs. (Members of Congress and state and local governmental officials also registered many comments, which we do not include in our analysis.)

We were able to collect these comments and include them as alternative explanations for success in the exclusion process. Using these comments, we calculated two additional control variables. First, if any comments publicly endorsed an exclusion request we code the variable Endorsed as a 1, otherwise it is coded as a zero. If any comments opposed the exclusion request, we code the variable Opposed as a 1. (These dichotomous variables capture the main variation in the data since an overwhelming share of requests had 0 or 1 endorsements and counter-endorsements. We look at a continuous variable below.) We introduce these variables as separate linearly additive controls in supplemental models in Table 10 to see how robust our findings of a positive lobbying effect are. We also present the coefficients on these variables for interested readers.

Table A6. Inclusion of supporting or opposing endorsements (dummy variable)

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

The results show two points. First, the positive effect of lobbying on exclusion granting is totally robust to the inclusion of these variables as controls across all models. Second, endorsement of the exclusion request is fairly consistently associated with a higher probability of earning exclusion. Opposition to the exclusion request is associated with a higher chance that exclusion is not granted in list 2 and 4 only. These results confirm the findings from Ludema et al. (Reference Ludema, Maria Mayda and Mishra2018) on the importance of stakeholder support and opposition to tariff suspensions.

In Table A7, we use a continuous version of the endorsement and counter-endorsement variables where we count number of supporting comments (Num. endorser) and opposing comments (Num.). Since the distribution of comments is highly skewed (containing mostly 0s or 1s but also some very large numbers in rare cases) we transform it with the inverse hyperbolic sine function. We find very similar results using this alternative approach.

Table A7. Inclusion of supporting or opposing endorsements (continuous)

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Heterogeneities in lobbying effectiveness due to size or multinationality using continuous measure of Section 301 lobbying

In Table A8 we examine heterogeneities using a continuous measure of lobbying expenditures as in the second robustness check in Table 2. The estimated interactions are strongly confirmatory of our results using the dichotomous measure of lobbying. Lobbying expenditures are significantly more impactful on earning exclusion for large and very large firms (in all models) and for medium firms (in models 3–6). The main exception is firms with Chinese subsidiaries who do not earn the same advantage in lobbying and are particularly disfavored in the model with all controls.

Table A8. Heterogeneities using continuous measure of Section 301 lobbying expenditures

Notes: All models are OLS. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Recreation of Figure 1 and Table 4 without industry variables

In this section, we recreate Figure 1 and Table 4 from the main text without the inclusion of the industry-level variables, which restrict the sample to goods-producing companies.

Figure A3. Heterogeneity of lobbying effects (Figure 1 without industry variables).

Table A9. Simulated effects of lobbying from interaction models (Table 4 without industry variables)

Notes: All expected outcomes and confidence intervals are created using medians, and 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles, respectively. The model is identical to model 6 in Table 1 but with

![]() $Lobbie{d_f}$

interacted with the three firm size dummies, and dummies for ownership of a Chinese subsidiary and of any subsidiary. ***

$Lobbie{d_f}$

interacted with the three firm size dummies, and dummies for ownership of a Chinese subsidiary and of any subsidiary. ***

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

,**

$p \lt 0.001$

,**

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

,*

$p \lt 0.01$

,*

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^ + }p \lt 0.1$

.

Heterogeneities in the treatment effects depending on patterns in campaign contributions

In Figure A4 we examine heterogeneous treatment effects based on firms’ campaign contributions to Democrats and Republicans, and on their headquarters location.

Figure A4. Heterogeneity of lobbying effects.