The study of American politics has long recognized the importance of the states as laboratories of democracy, yet the scholarly attention devoted to state politics has not always reflected this significance. For much of the twentieth century, the subfield was described as underdeveloped, fragmented, and in need of both theoretical grounding and stronger empirical foundations. Jewell’s (Reference Jewell1982) description of state politics as a “neglected world” captured a prevailing sense that the study of the states lagged behind other areas of political science in scope and influence.

Over the past four decades, however, the subfield of state politics has undergone a process of professionalization that has established clear boundaries between the study of comparative state politics and other areas of American politics. As part of this process, the subfield built enduring organizational structures through the APSA State Politics and Policy Section that sustain a vibrant community of scholars. The founding of the APSA Section in 1989, the launch of State Politics & Policy Quarterly (SPPQ) in 2001, and the establishment of the State Politics and Policy Conference (SPPC) the same year marked turning points in the process of differentiating the subfield of state politics from the rest of the discipline. Together, these developments provided a specialized outlet for research on state politics, a venue for scholars to network and receive feedback on their research, and a set of professional resources – including financial support for emerging scholars, like the Carsey Awards – that has helped to create a thriving academic community.

In this article, we use multiple sources of data – the publication of state politics articles in the discipline’s three leading generalist journals, the full corpus of SPPQ articles, and the programs of past SPPCs – to assess how the field has evolved over nearly seven decades. Our analysis highlights three central themes: the differentiation of state politics from the broader field of American politics, trends in the prominence of research topics that help to define the subfield’s boundaries, and the growing role of collaboration, both in the production of large datasets and the rise of coauthorship in the production of state politics research. Our analysis demonstrates how the subfield has both consolidated around enduring areas of inquiry and adapted to trends shaping the broader discipline of political science.

This article proceeds in three parts. First, we show how the emergence of SPPQ and SPPC facilitated the differentiation of state politics from the broader field of American politics. The number of state politics articles published in top general interest journals has remained relatively stable over time even as the share of state politics-related articles in those journals has dipped after SPPQ’s founding. Second, we examine the topics addressed by state politics scholarship over time, finding evidence of both stability in core research areas and diversification into new topics. Third, we document a significant rise in coauthorship, highlighting the collaborative nature of contemporary state politics scholarship and large data collection projects both across and within the states.

The development of the state politics and policy subfield

The differentiation of academic fields is a social process (Abbott Reference Abbott2001; Fuller Reference Fuller1991; Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Molnár2002). Scientists, for example, work to distinguish “science” from “non-science” (Gieryn Reference Gieryn1983) in many areas (perhaps most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic). Berkman and Plutzer (Reference Berkman and Plutzer2009), for example, show how the teaching of evolution in the public schools entailed a conflict between scientists, religious-based groups, and the public over who has the authority to say what should be taught in high school biology classrooms. Scientists make efforts in courtrooms and statehouses to exclude creationism and other ideas promoted by those outside science.

The way academic fields develop boundaries to differentiate themselves is a frequently studied topic across disciplines (e.g., Gieryn Reference Gieryn1983; Klein Reference Klein2021; Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Molnár2002). Political science, like other academic disciplines, is also divided into subfields, with four – American politics, comparative politics, international relations, and political theory – having achieved “totemic status” to allocate disciplinary rewards and structure understanding of the political world (Kaufman-Osborn Reference Kaufman-Osborn2006).Footnote 1 However, modern political science extends well beyond its four traditional subfields, encompassing a variety of specialized areas such as judicial politics, legislative studies, and gender and politics research. These domains have matured into well-recognized and highly organized fields in their own right, supported by formal structures like APSA’s organized sections and dedicated research outlets such as the Journal of Law and Courts, Legislative Studies Quarterly, and Politics and Gender. Through the creation of these domains, political scientists have built vibrant scholarly communities that not only advance specialized research but also demonstrate the increasing professionalization and diversification of the discipline.

This is all part of a general social process of boundary creation, where organizations, processes, and institutions generally become increasingly differentiated from their environment, granting authority to those within as opposed to those outside.Footnote 2 Our interest here is in the development of the state politics subfield and its increasing differentiation from the larger subfield of American politics. Our analyses trace this development, beginning with an examination of the state politics literature in the top three general interest journals – American Political Science Review (APSR), American Journal of Political Science (AJPS), and the Journal of Politics (JOP). We show how the founding of the APSA Section, followed by a dedicated journal, SPPQ, and an annual conference (SPPC) drew boundaries for state politics scholars within the larger field. As the study of state politics progressed from early studies of individual states to the use of large and complex datasets analyzed by multi-author teams, the field has increasingly established itself as one both connected to and differentiable from the broader American politics subfield of political science. Organizationally, the development of the State Politics and Policy Section within APSA, and then the creation of a dedicated conference and journal in 2001, created the social structures necessary to achieve and maintain these boundaries.

The publication of state politics scholarship in general interest journals

We begin our analysis of publication patterns in the subfield by examining the supply of state politics scholarship in top general interest journals in political science. To see how much and what kind of state politics scholarship was being published before SPPQ was founded and how that supply has changed after SPPQ entered the scene, we coded every article published in the APSR, AJPS, and JOP from 1960 through the second issue of 2025.Footnote 3 For each issue, we reviewed the titles, abstracts, and, when necessary, the text to identify which articles were “state politics” articles. Because any effort to classify articles in this way is necessarily subjective, we attempted to standardize the process by establishing a set of guidelines:

-

○ Following SPPQ’s editorial mandate, we included studies that develop and test general hypotheses of political behavior and policymaking, exploiting the unique advantages of the states.

-

○ Studies conducted within one particular state or region, comparing individuals or other units within the state counted as state politics articles.

-

○ We accounted for studies that included states (legislatures, bureaucracies, elections, etc.) as units of analysis along with other geographic settings (cities, etc.).

-

○ Studies of redistricting focused on state actions, means of redistricting, and impact on state legislatures were classified as state politics articles.

-

○ We did not include studies of local or urban politics, school district politics, and so forth, unless they specifically include the states as parts of the analysis (e.g., state aid and state funding).

In the sections that follow, we use these data to trace the publication of state politics research, examining patterns in the types of work published in leading venues over the past 65 years. Our aim is to identify common trends in how state politics scholarship has appeared in the discipline’s most prominent outlets and, in doing so, to assess the extent to which the subfield has differentiated itself from the broader discipline.

The early years: Single state studies with hints of what is to come

The first published effort to survey state politics as a field found it a “neglected world” in need of better theory and better data (Jewell Reference Jewell1982, 641). Specifically, Jewell laments the absence of truly comparative work across the states. Rather, he finds contextually rich single state studies that offer important efforts at describing the politics of individual states and efforts to generate unique theories, but he notes that many of these studies have limited generalizability. Only in research on the South did Jewell find a stream of theoretically compelling work emanating from V.O. Key’s pathbreaking comparison of states in Southern Politics in State and Nation (Reference Key1949).

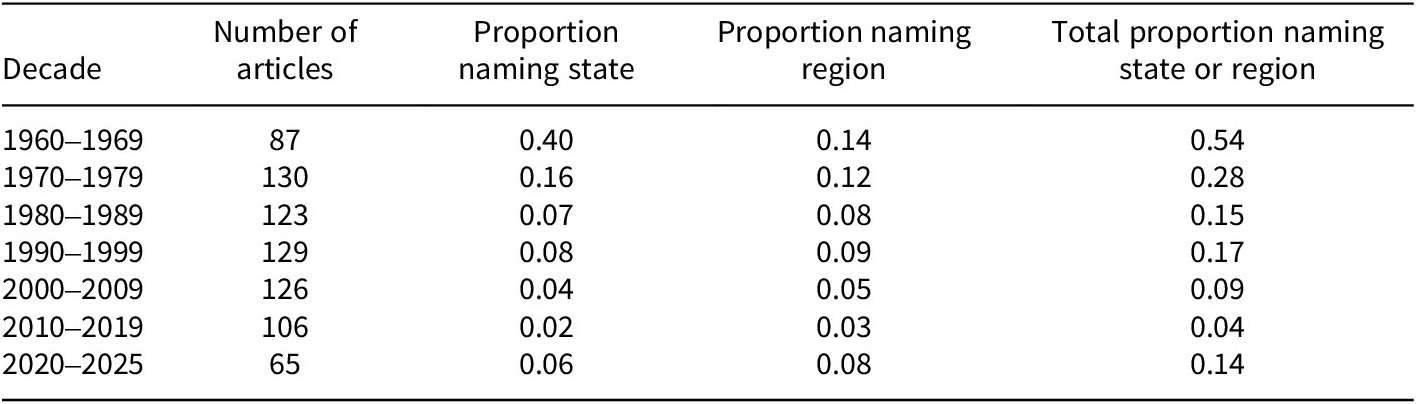

Our analysis of the top three journals confirms this early focus on individual states and regions in the years Jewell is surveying. But we also find theoretically important comparative work beyond that motivated by Key that would become foundational for the field. Table 1 shows this early focus on single state studies. We searched the titles and abstracts of articles published in the top three journals since the 1960s to code whether the focus of those articles is about a single state, a region, or something else (in nearly all cases, 50 state studies). The table documents a steady decline in the number of articles that concern either a specific state or specific region (in most cases, the South). While about 40% of state politics articles in the 1960s were about one state and another 14% about one region, this drops dramatically by the 1980s – to about one in six articles – as part of a gradual decrease over time. We note a slight uptick in the most recent years in our data, perhaps driven by an increased interest in causal identification that has led scholars to look for natural experiments or unique institutional variation in a single state.

Table 1. State politics articles in the top three journals that study one state or region

Note. AJPS articles in the 1960s and early 1970s are from the Midwest Journal of Political Science (which became the AJPS).

While journals were publishing highly state-specific articles like “Religious Influence on Wisconsin Voting, 1928” (Baggaley Reference Baggaley1962, APSR) or “Committee Stacking and Political Power in Florida” (Beth and Havard Reference Beth and Havard1961, JOP) during this time, we also see important early research using data across all 50 states. These early efforts at truly comparative state politics scholarship helped to establish now widely used research designs and theoretical orientations within the subfield. For example, the emphasis on public opinion that would drive so much of state politics research in subsequent years was noted in an AJPS article by Erikson, who uses data from the 1930s to show that “public opinion can exert a strong influence on state policy decisions” (Reference Erikson1976, 25).

In another important article, Hofferbert’s (Reference Hofferbert1966) “The Relation Between Public Policy and Some Structural and Environmental Variables in the American States” (APSR) employs the systems-theoretic framework inspired by David Easton (Reference Easton1965) to examine how inputs – such as socioeconomic conditions or political structures – shape policy outputs. This approach conceptualizes state governments as systems that respond to environmental stimuli. Crittenden’s (Reference Crittenden1967) “Dimensions of Modernization in the American States” (APSR) and Dawson and Robinson’s (Reference Dawson and Robinson1963) “Inter-Party Competition, Economic Variables, and Welfare Policies in the American States” (JOP) adopted this framework to empirically test theoretical propositions derived from broader theories of political and economic development generally.

Notably, rather than generating theory from within the American state context, these studies apply external models, often rooted in modernization theory or other approaches found in the study of nation-states, to explain variation in American state-level policy outcomes. Crittenden’s study, for example, begins, “Among the crucial facts of our time are the profound differences in ‘modernization’ or ‘development’ that characterize contemporary nation-state” (1967, 989). Dawson and Robinson explicitly test “the extent of inter-party competition and the presence of certain economic factors” by “using the American states as the units for investigation” (1963, 265).

In perhaps the best-known article about state politics during these early decades, Walker (Reference Walker1969) builds on this basic systems theory design by conceptualizing states as interconnected units within a broader policy network, where innovations adopted in one state serve as inputs for others. His findings also align with modernization theory, as early adopters tended to be more economically and institutionally developed, reinforcing the idea that modernization enhances a state’s capacity for innovation and responsiveness.

In short, much early state politics research consisted of studies of individual states or regions and tended to test theories developed in other areas of political science – mainly American politics or comparative politics – at the subnational level. At the same time, and especially for research on southern politics, the beginnings of a differentiated science of state politics and policy emerged as researchers began to look increasingly across the 50 states to find more generalizable answers to their research questions. While the state politics and policy subfield began to differentiate itself from the comparative and American politics through a distinct focus on the South, this process would not fully take shape until APSA created a formal state politics section, along with a dedicated conference and journal.

Drawing boundaries: SPPQ comes on the scene

In 1989, a group of researchers founded the State Politics and Policy Section of APSA, the 22nd organized section in the association. The creation of an organized section brought with it the standard trappings of boundary formation and maintenance, including a formal slate of officers, awards, endowments, and most importantly, dedicated panel allocations at the annual APSA meeting. The creation of the APSA section formally drew boundaries between the study of state politics and other areas of American and comparative political science by providing the foundation necessary to transform the field from a “neglected world” into an organized subfield encouraging more cross-state comparisons. Further, the section provided a focal point for interested scholars to connect at conferences to discuss their research and to form collaborations. The Section created its first slate of officers in 1990, established bylaws, and started to publish a newsletter in 1992. These changes are tangible evidence of a research group demarcating state politics as a unique and important area of study distinct from other parts of the discipline, like legislative studies.

By the late 1990s, the Section was laying the groundwork for two additional hallmarks of subfield development: a dedicated journal and an annual conference. SPPQ published its first issue in 2001. That same year, Texas A&M University hosted the inaugural SPPC.Footnote 4 Both the journal and the conference further institutionalized the subfield by creating regular venues for scholarly exchange. The dedicated graduate student poster section offered important networking opportunities and helped to maintain a steady stream of state politics scholars. Together, this signaled that state politics had become a distinct part of the discipline.

Brace and Jewett (Reference Brace and Jewett1995) review the state of the subfield during the early years of this period (1985–1995). They write that there has been “notable progress” in theory development and data during the 10-year period they reviewed. But they also note a “vexing blind spot” where too many studies ignore the “important role that states play in shaping political behavior and outcomes in the US” (1995, 646). In the process, Brace and Jewell review the publication of state politics-related research in top general interest journals.

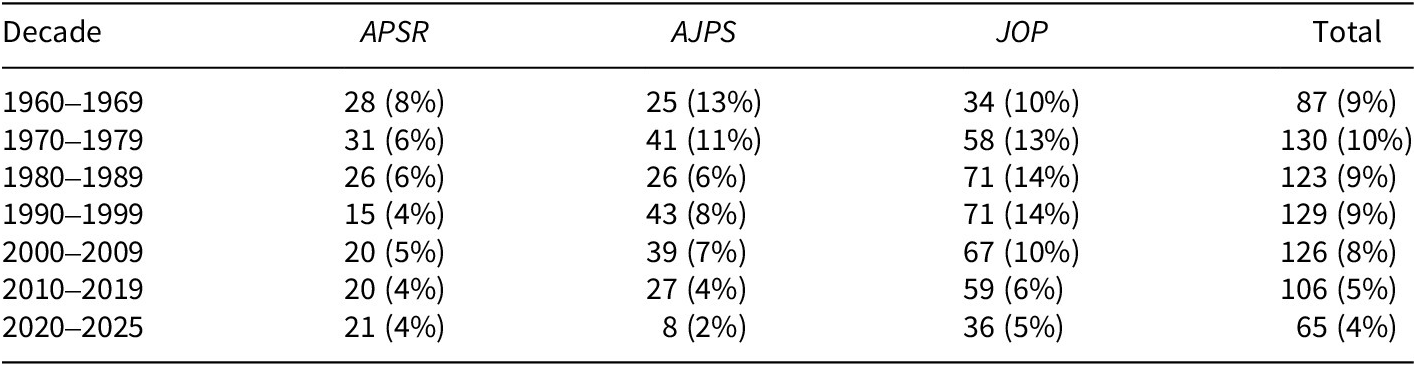

We do the same using articles from APSR, AJPS, and JOP. Table 2 displays the number of state politics articles published in these journals. Like Brace and Jewett, we find JOP consistently publishes more state politics research than AJPS or APSR both in volume and percentage of total articles in each journal.Footnote 5 However, since SPPQ came onto the scene in 2001, the JOP has also had the largest drop-off in state politics articles as a percentage of its total articles per decade as compared to the other two journals. This shift may be attributable to the journal’s changing focus from one centered on southern politics in its early era – where state politics scholarship had an advantage – to a full-service journal publishing work from across the entire discipline. Even with these changes, looking at the most recent decades, the JOP still consistently devotes the greatest count and percentage of its articles to state politics compared to the other two journals.

Table 2. State politics articles in the top three journals, by journal and decade

Note. The cell entries provide the number of state politics articles with the percentage of state politics articles in parentheses. AJPS articles in the 1960s and early 1970s are from the Midwest Journal of Political Science (which became the AJPS). For 2025, articles in each of the three journals were collected through the second issue.

Also notable is the relative stability in the number of state politics articles published in the APSR, AJPS, and JOP. The number of state politics articles APSR includes in its issues – and the proportion of space devoted to state politics articles across the decades – is especially consistent, though notably low, across the decades, ranging from 4% to 8% throughout the span of our data collection. The AJPS exhibits greater fluctuations in its publication of state politics research, but a more stable share of state politics articles as a proportion of its total articles. Still, the combined stability across the three journals – where, for five decades, state politics articles consistently made up between 8% and 10% of all publications – suggests the subfield’s durability and consistent visibility in the discipline’s leading outlets. Perhaps it was this increased attention to the states evident in these journals that provided justification, if not the impetus, for a state politics-centered journal. But once SPPQ appeared in 2001, the percentage of state politics articles in JOP and AJPS has consistently declined in each subsequent decade – even as this decline is modest.

This decline can be viewed in two different ways. On the one hand, all three of the “top” outlets in political science regularly publish articles related to state politics, and the quantity of state politics articles has remained essentially stable over time. On the other hand, the share of state politics articles in these journals has declined, particularly in the most recent decades, as SPPQ established itself as the flagship for research on state politics and policy. One explanation might be that the advent of the conference and the professionalization of the Section has spurred expanded scholarship on state politics, enough to continue to keep the number of general interest articles stable and fill the pages of SPPQ. But, other explanations are also possible. For example, as we note, over this period, the JOP became more of a general interest journal. The expanded publication of articles outside of American politics might have depressed the share of state politics articles in this journal. It is difficult to pinpoint any exact cause, but the two empirical trends seem clear: a relatively stable number of “top” state politics articles over time even as the percentage of total articles on state politics have dipped in recent years.

One reason for the stability of state politics research may be the increasing complexity in its scholarship as the subfield has evolved. This is evident in two separate, yet related points. First, scholars of state politics have persuasively used the 50 “laboratories of democracy” to regularly address broad topics of interest to scholars of American politics generally, rather than just state politics scholars. For example, we now see important state politics scholarship around questions of democratic backsliding (Grumbach Reference Grumbach2023; Nelson and Witko Reference Nelson and Witko2022); party polarization (Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002; Olson and Rogowski Reference Olson and Rogowski2020); institutional racism (Morris and Shoub Reference Morris and Shoub2024); and continued work on the long-standing question of democratic responsiveness (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and Hanson1998; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2009). Second, articles in the top three journals also often employ large and complex datasets as well as innovative research designs and methods. Consider, for example, some of the work in only the last five years:

-

• In Bucchianeri, Volden, and Wiseman’s (Reference Bucchianeri, Volden and Wiseman2025) “Legislative Effectiveness in the American States,” published in APSR, the authors develop State Legislative Effectiveness Scores (SLES) for state legislators across 97 legislative chambers from 1987 to 2018.

-

• Olson’s (Reference Olson2025) article in AJPS, “‘Restoration’ and Representation: Legislative Consequences of Black Disfranchisement in the American South, 1879–1916,” employs state legislative data on 19,400 unique roll call votes from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

-

• Lublin and Wright’s (Reference Lublin and Wright2023) “Diversity Matters: The Election of Asian Americans to U.S. State and Federal Legislatures,” available in APSR, collects data on all Asian American legislators elected from 2011 to 2020.

-

• Published in APSR, Cook and Fortunato’s (Reference Cook and Fortunato2023) “The Politics of Police Data: State Legislative Capacity and the Transparency of State and Substate Agencies” uses official data requests to trace the compliance of 19,095 state, county, and municipal police agencies over five decades.

-

• In Phillips’s (Reference Phillips2023) JOP article, “Intersectional Opportunities: Majority Minority Districts and the Descriptive Representation of Latinas and Latinos,” the author examines nearly 60,000 state legislative general elections from the mid-1990s to 2015.

-

• Kam, Kirshbaum, and Chojnacki’s (Reference Kam, Kirshbaum and Chojnacki2023) “Babies and Ballots: Timing of Childbirth and Voter Turnout,” published in JOP, merges administrative data on births and voter turnout in California.

-

• Gilardi, Shipan, and Wüest’s (Reference Gilardi, Shipan and Wüest2021) “Policy Diffusion: The Issue-Definition Stage,” published in AJPS, draws on over 52,000 paragraphs of newspaper data covering 49 states between 1996 and 2013.

These articles show considerable scope in both the research questions – including topics like police behavior and descriptive representation of minorities – and the construction of large datasets that, in many cases, shift the discipline from single-state case studies to data-intensive, multi-state analyses. This increasing complexity in state politics data reflects the progress of the subfield’s ability to differentiate itself, while still appealing to major disciplinary journals by producing state politics scholarship that speak to broader questions in national politics.

Indeed, a key mark of the field’s development over the past 25 years is the increasing integration of large, multi-user datasets, like Brace and Hall’s State Supreme Court Data Project (Brace and Butler Reference Brace and Butler2001) and, later, the Correlates of State Policy project (Grossmann, Jordan, and McCrain Reference Grossmann, Jordan and Joshua2021), Carl Klarner’s (Reference Klarner2018) data on election returns and party control of state government, Shor and McCarty’s (Reference Shor and Nolan2011) state legislative ideology scores, and Caughey and Warshaw’s (Reference Caughey and Christopher2018) estimates of state policy liberalism. By allowing multiple scholars to analyze the same dataset, these projects fueled the science of state politics by limiting the amount of time that different research teams need to spend collecting identical data to test their research questions.

This willingness to share data among members of the subfield is one of its most admirable qualities. It predated the replication revolution in political science, and early versions of the Section’s website had a data archive with freely available datasets researchers could use for their own projects. And, once replication began to become a concern in political science, SPPQ became one of the first journals, in conjunction with Tom Carsey and the Odum Institute at the University of North Carolina, to require scholars to post their data publicly and have it replicated by an analyst before publication. Further, SPPQ’s popular “The Practical Researcher” section assisted with the burgeoning data sharing movement in the discipline by providing researchers with data, methodological, and assessment resources to overcome common hurdles specific to the subfield. By requiring replication and creating norms of public data access, SPPQ was a leader among journals in political science in terms of data transparency in a way that built on the subfield’s internal norms about the value of collaboration and data sharing.

The content of state politics scholarship in top journals

To this point, our focus on trends in state politics scholarship in top journals has relied on an impressionistic sense of changes in publication alongside some data on the number of publications in each outlet over time. To provide a more granular accounting of trends in state politics scholarship, we conduct two additional analyses: an analysis of article topics hand coded from the titles and abstracts of articles and a textual analysis of article abstracts.

We begin by discussing hand-coded topics. Using each article’s title (and, where necessary, the abstract), we coded the topic of each article.Footnote 6 We identified a list of possible topics from a review of state politics undergraduate textbooks and graduate syllabi. The list of possible topics included:

-

• Intergovernmental Relations/Federalism

-

• Parties

-

• Elections

-

• Public Opinion

-

• Interest Groups

-

• Direct Democracy

-

• Legislative Politics

-

• Gubernatorial Politics

-

• Bureaucratic Politics

-

• Judicial Politics

-

• Criminal Justice Policy

-

• Economic and Fiscal Policy

-

• Health and Welfare Policy

-

• Education Policy

-

• Morality Policy

-

• Environmental Policy

-

• Policy (General/Multi-topic)

-

• Gender and Sexuality

-

• Race and Ethnic Politics

-

• Political Methodology

Topic coding was difficult. An article about vote choice in judicial elections may be seen by some as an article “just” about elections since the dependent variable in the article is voter behavior. For others, the fact that the article is about a judicial election (and therefore is probably more likely to be taught in a course on a day about courts than a day about voter behavior) means that the article is better categorized as a judicial politics article. The same is true about nearly every article about gender or race and ethnic politics: articles addressing these topics nearly always study these topics in relation to some other aspect of state politics (e.g., the fates of Black candidates in legislative elections or gender gaps in electoral behavior).

Further, some titles are more descriptive than others. For example, an article titled “Legislative Acceptance of Gubernatorial Budget Proposals” clearly relates to legislative politics, gubernatorial politics, and fiscal policy. Articles with more specific titles, like 2008’s “Southern Water Wars: Elazar Revisited” were more ambiguous. With this sort of ambiguity in mind, we acknowledge the presence of measurement error in our decisions even though each article’s topic coding was reviewed by multiple coders. To further mitigate some of these concerns, we assigned up to three topics to each article. Of articles in the top three journals, 40% of articles were assigned one code, 49% of articles were assigned two topics, and 11% of articles were given three codes.Footnote 7

Armed with these data, we look to Table 3, which displays the percentage of state politics articles, by topic, published in the top three journals in three periods: 1960–1985, 1986–2000 (the period including the founding of the APSA Section and leading up to the advent of the journal), and 2001–2025 (the post-SPPQ period). The right-hand column of the table provides the p-value from an ANOVA analysis.

Table 3. Percentage of state politics articles addressing each topic in top three journals, by period

Note. Note that each article could be assigned up to three topics, so the columns sum to a number greater than 100%.

Overall, we see several trends. Perhaps most notably, the percentage of articles about state legislative politics increased substantially from 17% in the early period to 27% after the founding of the journal. Conversely, the percentage of articles about political parties essentially halved, from 26% in the early period to 14% in the most recent period. This is due, in large part, to the decline in articles addressing southern politics specifically – a topic once a staple of the JOP’s table of contents. Also of note, the articles addressing general policy – articles using policy liberalism as the outcome variable, for example – have declined dramatically as a share of state politics articles published in top journals. This is due, in large part, to an uptick in articles dealing with specific policy areas, like criminal justice policy, education policy, environmental policy, and morality policy, all of which have become more common in recent years.

Areas where there is stasis also deserve comment. The share of articles relating to elections, gubernatorial politics, intergovernmental relations, and judicial politics have remained relatively stable over time. So too, perhaps surprisingly, has the percentage of state politics articles relating to race and ethnic politics remained constant (even as the percentage of articles relating to gender has increased fourfold across the three periods). Again, this is likely due to the subfield’s historical interest in southern politics where articles about party realignment often paid close attention to the voting patterns of Black Americans in that region – for example, Matthews and Prothro’s (Reference Matthews and Prothro1963) article, “Social and Economic Factors and Negro Voter Registration in the South.” Even as the percentage of articles related to legislative politics has increased dramatically and the share of articles about parties has severely declined, articles about legislative politics, elections, and parties are the most common topics in both the early and recent periods. The persistence of these core topics, even as other themes rise and fall, suggests the field has established durable boundaries.

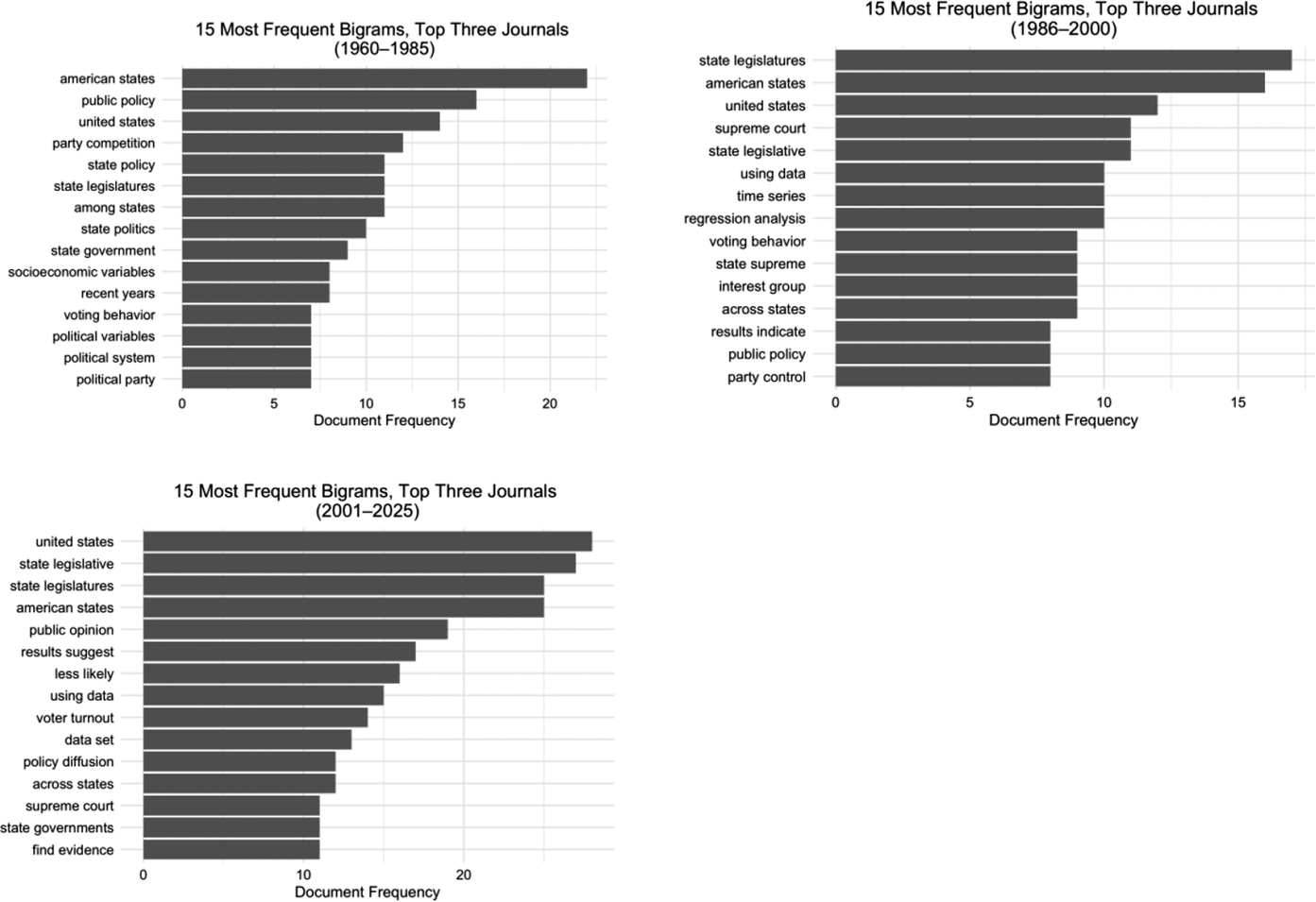

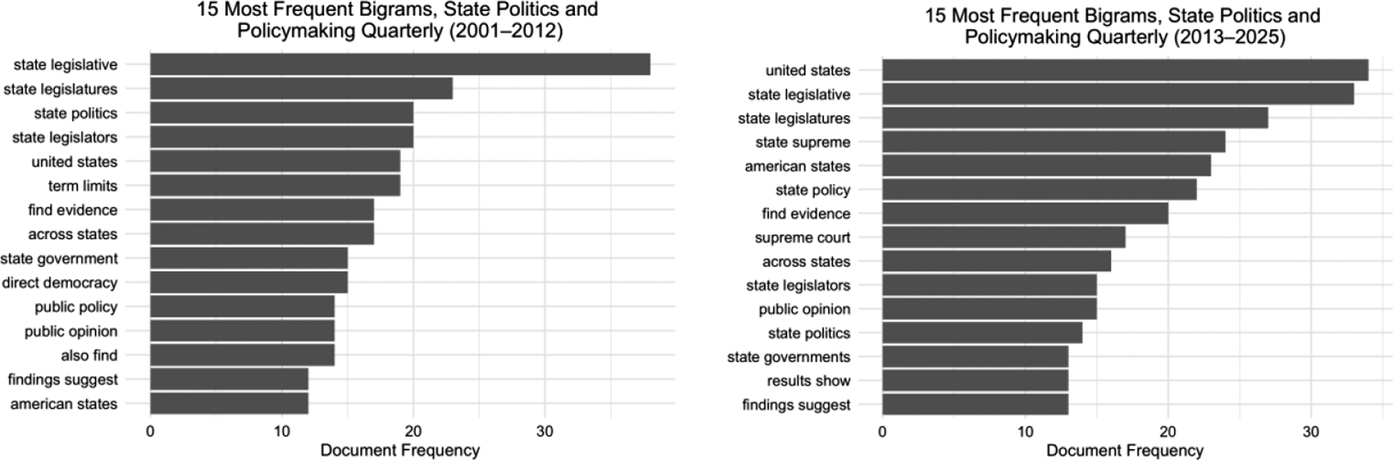

As we note, topic coding is a more subjective measure of article content. To further examine how themes in the top three journals have changed over time, we supplement our topic coding by looking at state politics article abstracts for the most frequently used phrases, focusing on two-word combinations (bigrams) in each abstract.Footnote 8 We compare word usage across the same three periods in Figure 1 and Table 3, examining how topics rise and fall in salience with the founding of SPPQ. We report four significant changes in the topics of state politics articles over the three periods under consideration – all these findings bolster our conclusions from Table 3.

Figure 1. Most frequent bigrams in state politics articles published in top journals, by period.

First, there is a substantial increase in the use of terms like “state legislative” and “state legislatures” across the three bar graphs. Between 1960 and 1985, only the term “state legislatures” appears frequently in article abstracts. By the second period (1986–2000), this has changed: “state legislatures” dominates as the most frequently used two-word phrase in state politics article abstracts and “state legislative” enters as a top five term. Between 2001 and 2025, “state legislatures” and “state legislative” both maintained top five positions in article abstracts. This trend is similar in Table 3, where we report a doubling of articles about legislative politics between the first and third periods in our analysis.

Second, abstracts with phrases related to parties decline steadily. Phrases like “party competition” and “political party” were frequently employed in abstracts during the first period (1960–1985) when over a quarter of articles were coded as “parties” literature. In the second period, the most frequent “parties” adjacent term is “party control,” and by the third period, we do not see any phrases related directly to parties frequently used in combination. This mirrors the decline we see in articles coded under the “parties” topic in Table 3.

Similarly, the term “public policy,” the second most frequently employed phrase in abstracts in the first period (1960–1985), moves to the bottom of the most frequently employed phrases in the two subsequent periods. This parallels the trend reported in Table 3, where articles coded under general policy dip considerably in the latter two periods, with the number of articles coded as general policy articles cut in half.

Finally, mentions of public opinion in state politics article abstracts increase – specifically in the most recent times. While public opinion is not a top term in either the 1960 to 1985 or 1986 to 2000 period, it is one of the five most frequently used two-word phrases in the 2001 to 2025 period. This is similar to the pattern observed in topic coding reported in Table 3, where the number of articles coded as public opinion doubled in the periods from 1960 to 1985 and 2001 to 2025.

Together, these patterns suggest that trends in phrase usage within state politics article abstracts broadly track the shifts in topic coding we report across the top three journals. Thus, the text patterns identified in our analysis of article abstracts reinforce the broader changes captured in topic coding. Substantively, these conclusions reinforce our findings about the changing positions of state legislative and parties-related scholarship, even as both of those topics remained more popular than other areas of state politics research throughout this entire period.

The content of SPPQ and SPPC scholarship

To this point, we have focused our analysis on the development of the state politics subfield on top general interest journals. The introduction of SPPQ and the SPPC have also played an essential role in this process. How have the topics of scholarship presented in the subfield’s most prominent outlets changed over time? And, how do they compare to the attention given to those topics in the major general interest journals?

To analyze trends in publications in SPPQ and at the SPPC, we collected near-complete data on articles published in the journal and scheduled for presentation at the conference.Footnote 9 For SPPQ articles, we were able to use the Cambridge University Press website for the journal through August 2025. Through contact with conference hosts, Section members, and conference websites, we were able to acquire the conference programs for nearly all of the previous SPPCs, including the canceled 2020 conference.Footnote 10 Together with research assistants, we coded each article published in SPPQ and every article listed on the main conference program (including articles presented in graduate student poster sessions). This was a total of 528 SPPQ articles and 1,781 SPPC articles.

Number of articles

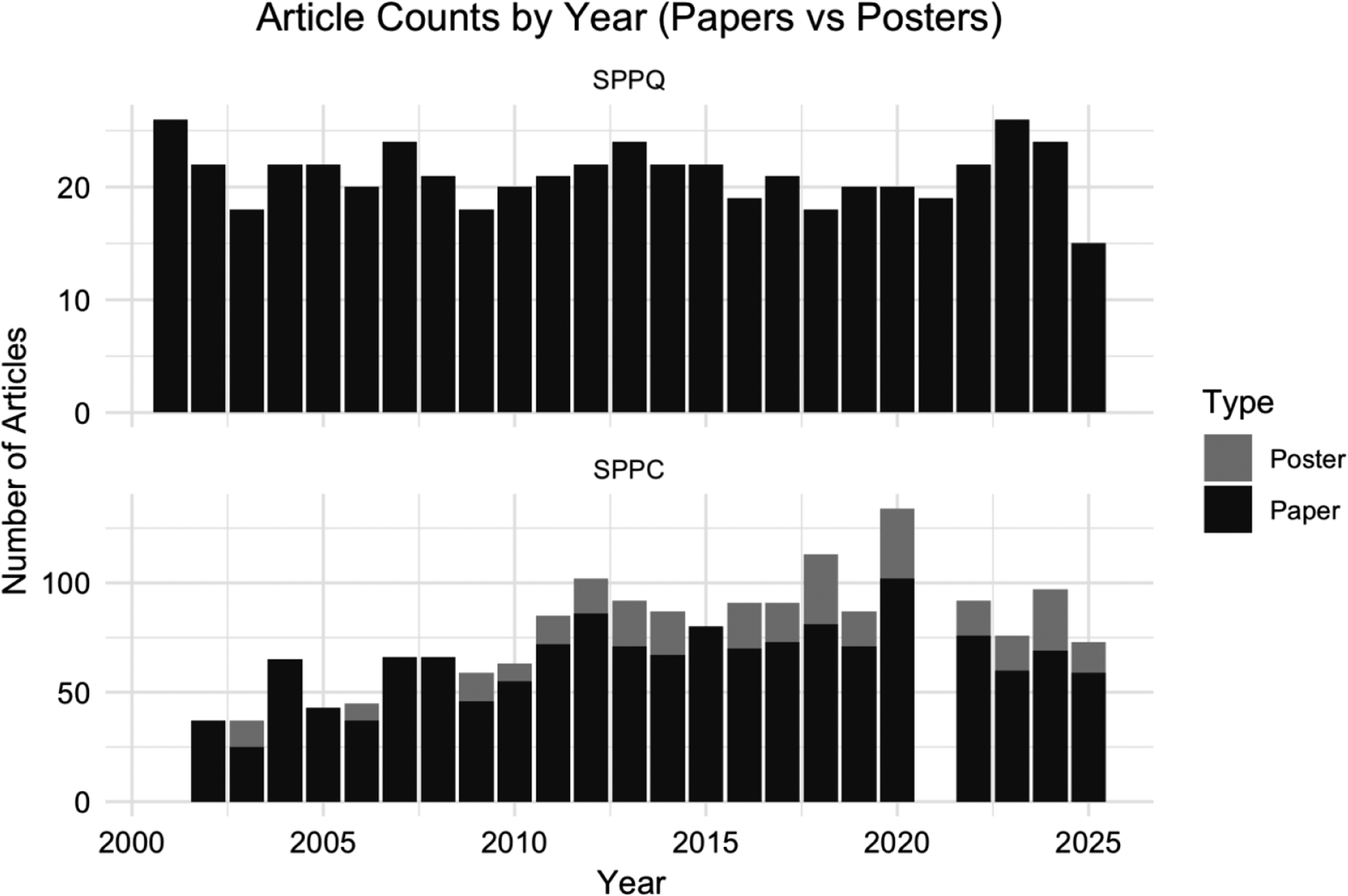

We begin, in Figure 2, by looking at trends in the number of articles at both SPPQ and SPPC over time. Starting with SPPQ in the top panel of the figure, we see that the number of articles published per year has hovered at 20 articles until recently. The slight uptick in articles over the past five years can be attributed to the introduction of short articles in the journal which allowed the editors to publish more articles while maintaining the size of the print journal.

Figure 2. Count of articles, papers, and posters, by year. Note that there we no SPPC held in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and data for SPPQ in 2025 contains only the first two issues.

Turning to SPPC, in the bottom panel of the figure, there is a gradual upward trend in the number of papers and posters over the first two decades of the conference, though the conference has tended to have between 85 and 100 of them since 2012. In other words, after some initial growth, participation in the conference has leveled out over the past decade.Footnote 11 Also relatively stable has been participation in the conference’s usual graduate student poster session.

Next, we turn our attention to the topics addressed by research presented at SPPC or published in SPPQ. Figure 3 plots the percentage of scholarship that addresses each topic in SPPQ and SPPC, and we also include a comparison to the top three journals. Recall that each research project could be assigned up to three topics, so the bars sum to a number greater than 100%.

Figure 3. Percentage of articles addressing each topic. Note that each research project could be assigned up to three topics, so the bars sum to a number greater than 100%.

Topics across outlets

From the figure, a few conclusions are immediately apparent. First, perhaps the most striking conclusion from the figure is the comparative overrepresentation in articles on elections and legislative politics. Over one-in-four articles presented at SPPCs or published in SPPQ were classified into one of these two topics. Articles on public policy topics – including education, health and welfare, and general policy – are also well-represented on conference programs and in the journal, with about 30% of conference articles, on average, addressing some area of public policy.

The “second tier” of topics is more crowded, with articles addressing parties, public opinion, and race and ethnic politics each comprising about 8%–12% of articles in both the journal and at the conference. In terms of public policy, economic policy has been the most addressed policy area, with about 10% of articles addressing the topic.

A second clear conclusion from the figure is how well the proportion of articles addressing each topic is similar in both the conference and the journal. For example, 27.7% of articles in SPPQ address some aspect of legislative politics; 27.8% of articles at the conference do the same. The two areas with the largest gap are articles concerning judicial politics and gender. The share of judicial politics articles published in SPPQ is higher than the share of articles on that topic presented at the conference, while the reverse is true for articles concerning gender. Conference programs contain about 5% more articles about gender and politics than the pages of SPPQ.

Finally, it is notable that while the topics addressed in SPPQ and SPPC are nearly equal (with a few exceptions highlighted above), there is a good amount of divergence between topics featured in the top three journals compared to SPPQ and SPPC. The top three journals feature nearly twice the number of articles on general policy compared to SPPQ and SPPC. Scholarship about political parties also deserves note: while parties-related articles are the third-most common topic in general interest journals, the share of parties-related articles in SPPQ is about 8% less. By contrast, the share of articles about state legislatures published in SPPQ is about 7% greater than the share of state legislative articles published in the top three journals. This is similar to trends in morality policy and public opinion compared to the subfield’s outlets – both of which are published less in the top three journals. Taken together, this suggests that the topics in the subfield’s outlets and the top three journals diverge in ways that may shape the visibility of these topics in the broader discipline and shows the increasing distinctiveness of state politics as a field, maintained in large part through its conference, journal, and formal section.

To determine how much these topics have varied in their attention over time in each of our three venues, Table 4 displays the difference, by venue, in the proportion of articles addressing a given topic for two time periods (dividing the post-SPPQ period in half): from 2001 to 2012 and 2013 to 2025.

Table 4. Difference in the proportion of paper, by topic, from 2001 to 2012 and 2013 to 2025

Note. Positive values of the difference mean that the topic was more popular in the recent period than the earlier period. Note that each paper could be assigned up to three topics.

The table leads to several conclusions. Notably, scholarship on direct democracy and gubernatorial politics has generally decreased over the past quarter century. At the same time, research on judicial politics has increased in SPPQ even as it has declined in the top three (though that difference is not statistically significant due to the small number of articles).

But, overall, there has been a relative stasis in the topics. For only four topics – direct democracy, gubernatorial politics, methods, and judicial politics – are there statistically significant differences between the two time periods in SPPQ. And, in the top three, there are only two topics – criminal justice policy and direct democracy – where we observe statistically significant differences.

To validate our topic coding, we again turn to frequently used two-word phrases in SPPQ abstracts, illustrated in Figure 4.Footnote 12 Legislative politics articles continue to dominate, with terms like “state legislative,” “state legislatures,” and “state legislators” appearing consistently across both periods of SPPQ. This aligns with the non-significant change reported for legislative politics in Table 4. Public opinion phrasing is also prominent in abstracts during both the early and later periods of SPPQ, just as Table 4 suggested. Most notably, however, is the emergence in phrases related to judicial politics, specifically “state supreme” and “supreme court.” While these phrases are less frequent (or absent altogether) in article abstracts in the early period of SPPQ, they appear frequently in the most recent period. This corresponds with the significant increase in SPPQ articles coded as judicial politics in Table 4.

Figure 4. Bigrams in SPPQ abstracts, 2001–2012 and 2013–2025.

Taken together, these patterns highlight the degree to which SPPQ and SPPC have both reflected and reinforced the boundaries of the state politics subfield. The consistency of topic coverage across the journal and conference underscores the maturation of a shared research agenda, while the divergences from the discipline’s top three journals reveal the subfield’s distinctive priorities. SPPQ and SPPC have helped consolidate boundaries that distinguish “insiders” from “outsiders” while also fostering a professional identity grounded in specialized venues of exchange. At the same time, the broad continuity of topics over two decades suggests that the subfield has achieved stability without becoming insular, remaining open to new policy areas and methodological innovations. These dynamics position the subfield’s major institutions as central engines of its continued development, providing the infrastructure necessary to sustain both continuity and innovation in the study of state politics.

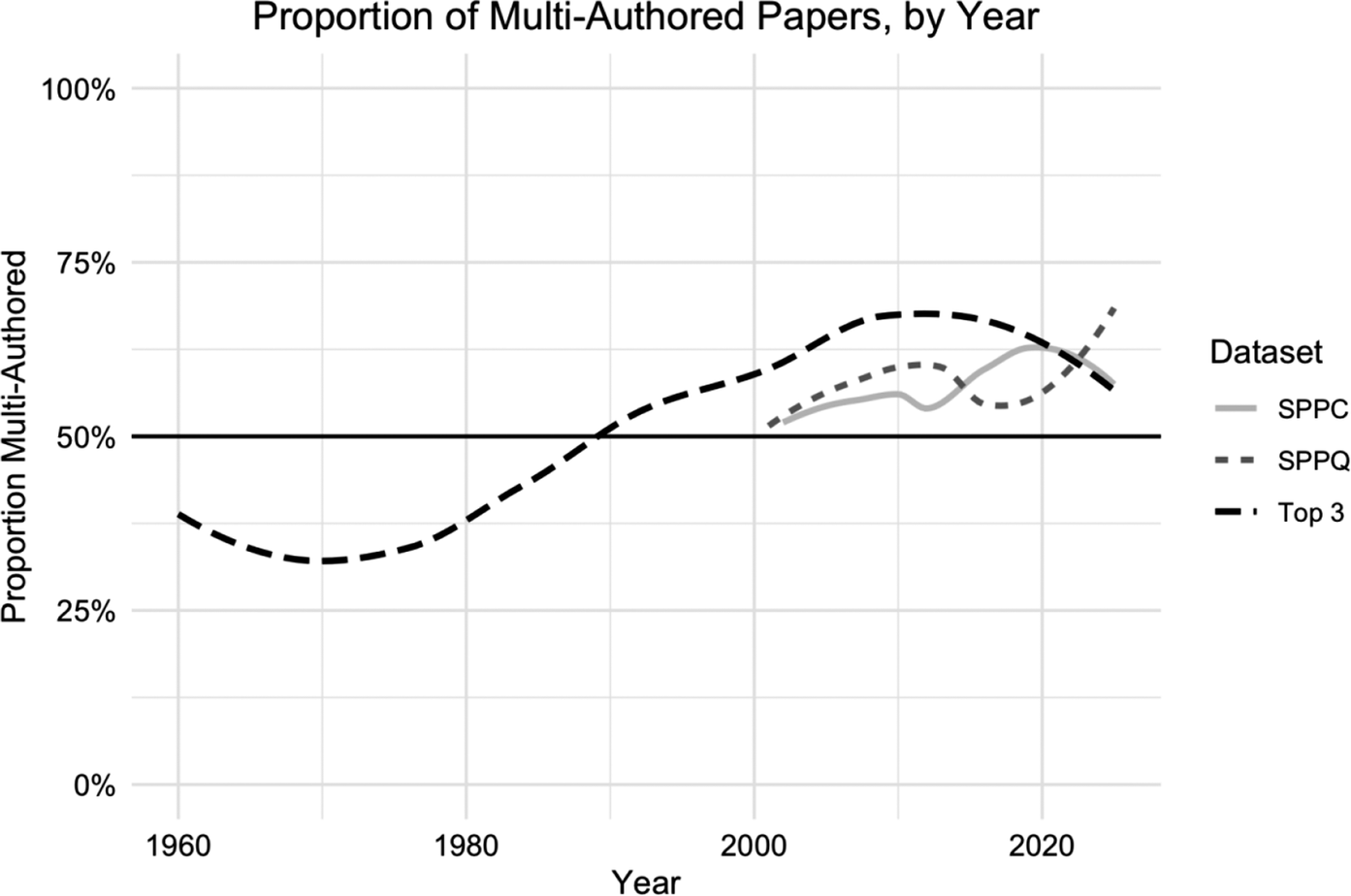

Coauthorship in the state politics subfield across the years

Finally, we turn to trends in coauthorship within state politics scholarship. Examining patterns of coauthorship is useful not only because it reflects the development of the subfield but also because it provides insight into the broader evolution of research practices in political science. Coauthorship patterns may additionally be of interest to tenure and promotion committees, which often weigh the prevalence of joint work when evaluating faculty contributions in different areas of the discipline.

Figure 5 presents a best-fitting line that captures the percentage of state politics articles that are coauthored across each of our three datasets. In the earliest years of our data, single-authored work dominated the subfield, reflecting both the disciplinary norms of the time and the relatively limited size of the state politics research community. Over time, however, this pattern shifted dramatically. Since the mid-1980s, coauthorship has become the norm rather than the exception, with the modal state politics article in the discipline’s leading generalist journals featuring two or more authors.

Figure 5. Trends in coauthorship over time. SPPC papers omit graduate student posters which are normally single-authored.

The same pattern is evident in the specialized institutions of the subfield itself: both the SPPC and SPPQ have, from their inception, been defined by a high level of coauthorship. The shift from single-authored case studies to multi-author, data-intensive collaborations exemplifies the idea of subfield boundaries: teams of authors now bring specialized methodological and substantive expertise that reflects a maturing disciplinary structure.

Discussion and conclusions

The trajectory of state politics scholarship over the past six decades illustrates the development of a once “neglected” area of political science into a robust, distinct, and well-defined subfield. We argue that the creation of the APSA State Politics and Policy Section, the launch of SPPQ, and the regular convening of the SPPC have provided the infrastructure necessary for scholars to coordinate research agendas, develop professional networks, and disseminate findings to a specialized audience – all indicators of a subfield that has evolved by establishing clear boundaries from the broader field of American politics. Our analysis provides evidence of this on three fronts.

First, the state politics subfield has differentiated itself from the broader field of American politics. The decline in highly state-specific articles, paired with a rise in research using the “laboratories of democracy” framework and large, complex datasets mark a shift from single-state case studies to data-intensive, multi-state analyses – an important marker of subfield’s substantive complexity as it evolved and drew its own boundaries in the American politics field.

Second, by analyzing the topics of state politics articles over time, we show a mix of continuity and change in in the prominence of research topics that help to define the subfield’s boundaries. Elections, legislatures, and political parties remain the backbone of state politics research, demonstrating a remarkable stability across decades. At the same time, the subfield has diversified, with greater attention to judicial politics, gender, and specific areas of public policy. This pattern reflects the dual pressures facing a maturing subfield: the need to build cumulative knowledge around enduring questions while also responding to new political realities, data sources, and theoretical frameworks.

Finally, we discuss the growing role of collaboration, both in the production of large datasets and addressing enduring research questions that define the subfield. The discipline’s norm of data transparency and sharing, championed by Tom Carsey, the Odum Institute, and “The Practical Researcher,” positioned the Section at the forefront of collaboration and data sharing research practices that propelled the subfield’s ability to differentiate itself from the broader discipline.

The rise of coauthorship underscores the collaborative and increasingly complex nature of contemporary state politics research. This shift aligns state politics with broader disciplinary trends toward teamwork and collective knowledge production. It also raises practical considerations for how tenure and promotion committees evaluate scholarly contributions, underscoring the importance of recognizing collaboration as a marker of institutional maturity rather than a departure from individual achievement.

Looking ahead, the next chapter in the subfield will be shaped by enhanced data access and new technologies. Scholars now have access to a broader range of evidence – administrative data, digital records, artificial intelligence, and geospatial tools – than ever before. These new data sources and tools open up new and exciting paths for our understanding of comparative state politics. At the same time, the political landscape itself is shifting. Democratic backsliding, partisan conflict, persistent social inequities, and the growing diversity among states all raise important opportunities for state politics scholars to generate and test theories applicable to scholars of American and comparative politics generally. The continued strength of SPPQ and SPPC will depend on how well the community weaves these new tools and topics into its work while staying welcoming to the next generation of scholars. If the past 25 years are any indication, the field is more than capable of doing that, and of remaining a central voice in the study of American politics.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/Y8W0L4 (Berkman, Herlihy, and Nelson Reference Berkman, Herlihy and Nelson2025).

Acknowledgements

Megan Kennedy, Savannah Morris, Nora McGinnis and Morgan Phillips provided helpful research assistance.

Funding statement

The authors thank the McCourtney Institute for Democracy and the Department of Political Science at Penn State for supporting this project.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author biographies

Michael B. Berkman is Professor of Political Science and Director of the McCourtney Institute for Democracy at Penn State.

Morrgan T. Herlihy is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science and Social Data Analytics at Penn State.

Michael J. Nelson is Professor of Political Science and Affiliate Law Faculty at Penn State.