INTRODUCTION

A perennial concern with political decentralization is that it enhances locally powerful elites’ ability to “capture” the state (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008; Bardhan and Mookherjee Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2000). Rather than fostering subaltern citizens’ inclusion in the exercise of political power, recent accounts suggest that decentralization can produce forms of governance where local executives are sidelined by unelected elites who control political institutions. Particularly in highly unequal contexts, local executives may thus not enjoy de facto political authority, or “the recognition and deference to [de jure] authority in practice” (Busch et al. Reference Busch, Heinzel, Kempken and Liese2022, 231); they may not partake in decision-making in the way their de jure role intends. The stakes are high: the strength of the local executive, versus the hold of special interests over political institutions, has deep developmental and distributive consequences (Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014; Bates Reference Bates1981; Martinez-Bravo, Mukherjee, and Stegmann Reference Martinez-Bravo, Mukherjee and Stegmann2017).

In recent years, direct elections have been proposed as an institutional remedy for captured local democracy and weak executive power. Direct elections (like presidential elections) allow the masses to decide who will represent them through directly voting for an executive, whereas indirect elections (like parliamentary elections) empower a smaller electorate (typically elected politicians) to decide, behind closed doors, the face of the executive. Wielded as a tool of democratic deepening, direct elections are thought to empower strong, autonomous executives by disrupting elites’ (and enhancing the people’s) hold on political institutions (Gaebler and Roesel Reference Gaebler and Roesel2019; Harvey Reference Harvey2022; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Zhang, Huang and Rozelle2007; McDonnell and Mazzoleni Reference McDonnell and Mazzoleni2014; Sweeting and Hambleton Reference Sweeting and Hambleton2020; Van Coppenolle Reference Van Coppenolle2022). They featured prominently in late twentieth century demands to bring democracy “closer to the people,” holding the potential to “radically reconfigure the dynamics of local politics” (Copus Reference Copus2004, 576). Indeed, we have observed a recent wave of transitions to direct elections on a global scale (Scarrow Reference Scarrow2001; Steyvers et al. Reference Steyvers, Bergström, Bäck, Boogers, De La Fuente and Schaap2008).

Little research, however, establishes the link between direct elections and democratic deepening in highly unequal, decentralized settings in the Global South. In local, weakly institutionalized settings, where “nonelectoral influences, particularly by the better organized elite, are a major concern,” wresting power from traditional elites to empower the local executive is nontrivial (Acemoglu, Robinson, and Torvik Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Torvik2013, 871). Yet, much experimentation with electoral design of decentralized government is occurring in Global South contexts. India, Panama, Malawi, Zambia, Thailand, and Indonesia have proposed or passed reforms in recent decades to directly elect local executives. Theorizing whether direct elections may indeed serve as an institutional remedy for captured decentralized democracy—or when and why this purported remedy may fall short—is thus particularly relevant for a large swath of the world’s citizens.

Drawing on over two years of theory-building fieldwork in rural India, I argue that direct elections can strengthen the de facto authority of the local executive not by rupturing elite coalitions, but by changing the way that elites capture democracy. Directly elected executives may enjoy heightened de facto authority not because they are less beholden to elite structures than their indirectly elected counterparts, but rather because they are members of the traditional elite themselves, and thus possess the social privilege, networks, and political knowhow necessary ex ante to command power. Direct elections can shift the mode of elite capture from informal to formal channels as entrenched elites face heightened institutional barriers to maintaining informal control. While indirect elections beget informal capture, where elites influence proxy politicians from the sidelines, direct elections prompt formal capture, where elites contest elections themselves and command political institutions from within. Electoral reform may alter the mode of capture—and thus the de facto authority of the local executive—but the durable fact of captured democracy persists.

I test this argument in an empirically and substantively unique context: village governments in Maharashtra, India. To overcome challenges of estimating impacts of typically endogenous electoral institutions (Boix Reference Boix1999; Przeworski Reference Przeworski2004; Rodden Reference Rodden, Lichbach and Zuckerman2009), I leverage a quasi-experiment that manipulated how local executives (village council presidents) were elected across the state. In 2017, the state changed the election of council presidents from indirect (selection via council members) to direct (election by the people) (Ghadyalpatil Reference Ghadyalpatil2017), and in 2020, the decision was reverted (Times of India 2020). This period of reform, plus the state’s impressively staggered village council electoral cycles, provides a plausibly quasi-experimental setup. Plus, elite factions are entrenched in rural Maharashtra (Deshpande and Palshikar Reference Deshpande, Palshikar, Nagaraj and Motiram2016). Studying electoral reform in this context sheds light on the hard limits of institutional engineering that seeks to bring democracy “closer to the people.”

I triangulate across qualitative case comparisons, original survey and administrative data, and a pre-registered survey experiment to test my argument.Footnote 1 First, to trace the processes by which direct elections shape elite capture and de facto authority, I draw on controlled comparisons between two village councils. Second, to test the main relationship between direct elections and de facto executive authority, I use novel survey data from 604 village councils with both behavioral and perception-based measures of de facto authority; I find that direct elections produce stronger local executives. Third, I present evidence of one potential mechanism: that direct elections shift the mode of elite capture to formal channels. Using the same survey data on Maharashtrian village councils and an original administrative census of political resignations in one district of over 1,300 village councils, I show that direct elections increase the demographic representation of traditional elites among council presidents (formal capture) and decrease external elite interference in village councils (informal capture). I also leverage a preregistered, out-of-sample survey experiment among 2,347 voters as a partial mechanism test, documenting that formal capture causes a de facto authority advantage.

This research implies that the way local executives access power has wide implications for their de facto authority once in office. Direct elections usher in remarkably stronger local executives, reinforcing the link between de jure and de facto authority. However, there is a catch: the way this link is strengthened is not via altering the fabric of unequal power relations at the local level. Rather, the microfoundations of elite capture are merely reconfigured. This suggests the possibility of varieties of what Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008) term “captured democracy,” which may differ as a function of institutions. Yet, while elites may change strategy based on electoral institutions, the distribution of political resources likely remains the same under both regimes. In many ways, this case presents an example of elite invariance: traditionally entrenched powerholders in communities find innovative ways to remain solidly at the helm of local decision-making, despite institutional “shocks.”

Is there a way out? Changing one electoral institution—here, election type—may not prove sufficient to rupture elite coalitions’ hold on local political institutions. However, in the conclusion of this article, I provide suggestive evidence that wresting power from traditional elites’ grip may be possible in the presence of additional, overlapping institutional constraints. Drawing on survey and qualitative evidence, I suggest that direct elections in tandem with sufficiently binding constraints on political selection (here, quotas for Scheduled Castes [SCs]), may allow members of nonelite groups not only to access the corridors of power, but also to enjoy the de facto authority that executive office, in theory, promises. However, such gains are not costless, since they threaten the standing political order. As a result, they may engender new strategies of elite backlash: for example, violence. This presents an important avenue for further research.

This article makes three main contributions. First, in leveraging a quasi-experiment in Indian village councils, I add new evidence to a large literature which argues that electoral institutions matter in shaping local government. Second, this article contributes to the study of electoral institutions and representation in decentralized democracy by focusing on an understudied institution in this context: election type. Particularly in Indian local democracy, scholarly focus has centered on gender and caste quotas (Bhavnani Reference Bhavnani2009; Brulé Reference Brulé2020; Chattopadhyay and Duflo Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004; Chauchard Reference Chauchard2017; Goyal Reference Goyal2025). My findings invite us to consider how another institution that varies in this context and globally—election type—shapes democratic representation. For many of the outcomes studied in this article, this study’s estimates of direct election’s effects rival or outweigh those of gender and caste quotas, canonical institutions that are crucial in shaping who accesses and exercises power at the local level in India.Footnote 2 Remarkably, direct elections are more predictive than gender quotas for all measures of informal capture (Appendix D of the Supplementary Material); this is important to note, given recent findings that Indian gender quotas may lead to forms of proxy governance (Amar, Bamezai, and Kumar Reference Amar, Bamezai and Kumar2025; Chauchard, Brulé, and Heinze Reference Chauchard, Brulé and Heinze2025; Heinze, Brulé, and Chauchard Reference Heinze, Brulé and Chauchard2025; Huidobro, Prillaman, and Singhania Reference Huidobro, Prillaman and Singhania2025; Karekurve-Ramachandra and Sood Reference Karekurve-Ramachandra and Sood2024). Finally, I advance the body of research that documents elite capture of democracy by demonstrating how institutional design shapes elite efforts to hold onto power (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008; Dupraz and Simson Reference Dupraz and Simson2024; Martinez-Bravo, Mukherjee, and Stegmann Reference Martinez-Bravo, Mukherjee and Stegmann2017). This article extends conceptually and documents empirically the idea of elite invariance via differing modes of capture: in the face of electoral reform, elites may invest in de facto power by adapting how they control political institutions. Understanding the microfoundations of elite capture can help us theorize what additional tools are necessary to disrupt elite dominance in decentralized democracy.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

The Problem: Elite Challenges to Executive Authority in Decentralized Democracy

De jure political authority refers to the power an officeholder enjoys via the legal recognition of her elected office. De facto political authority, on the other hand, is “the recognition and deference to this authority in practice” (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008; Busch et al. Reference Busch, Heinzel, Kempken and Liese2022, 231). It is important to distinguish between de jure and de facto political authority because of what we often see in the real world: despite holding formal office, some politicians do not enjoy recognition and deference in practice (Cruz and Tolentino Reference Cruz and Tolentino2019). This matters for their ability to govern and represent their constituents’ interests (Heinze, Brulé, and Chauchard Reference Heinze, Brulé and Chauchard2025; Purohit Reference Purohit2023).

In decentralized governments, elected executives may lack de facto authority because unelected elites command it (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008). Elite capture of democracy occurs when elites “hijack” political institutions “to suit their ends,” leading to “the lack of involvement of…marginalized groups in decision making” and “outcomes that are less aligned with their needs” (Mookherjee Reference Mookherjee2015, 236). Concerns about captured democracy are common in Maharashtra, India: Maharashtrian local politics has been called a “veneer of representative democracy, [where] minority local elites…capture majoritarian local institutions and run them in their own interests” (Anderson, Francois, and Kotwal Reference Anderson, Francois and Kotwal2015, 1781).

In this article, I note that a status quo form of captured local democracy is informal. Informal capture occurs when entrenched elites control political institutions through exerting influence from behind the scenes, often via pliable proxy candidates. Though it may produce principal-agent inefficiencies (Ross Reference Ross1973), exerting control informally via proxy is advantageous from the perspective of local elites in settings marked by enduring inequality and clientelism. Ruling from behind the scenes allows elites to skirt the legal and public scrutiny of formal office, perhaps increasing their ability to rent-seek with impunity. In addition, when elites place their proxy candidates in positions of political power, this can serve as a source of patronage that elites distribute to their followers, increasing followers’ reliance on and indebtedness to their local boss. While standard theories identify lack of information or expertise as reasons for delegation (Bendor and Meirowitz Reference Bendor and Meirowitz2004), the costs of formal responsibility and public scrutiny may outweigh the costs of delegating power to proxies. Research from a variety of contexts suggests that such “plausible deniability” proves a compelling reason for political actors to delegate (Fox and Jordan Reference Fox and Jordan2011; Strayhorn Reference Strayhorn2019; Williamson Reference Williamson2023).Footnote 3

Informally captured local democracy poses a fundamental challenge to democratic representation. If the local executive lacks de facto authority, and instead unelected elites rule from behind the scenes, voter-representative accountability linkages may be severed. In what follows, I discuss what has been considered a potential solution to informally captured democratic institutions: direct elections.

Direct Elections as a Potential Solution?

Direct elections featured prominently in late twentieth century demands to bring democracy “closer to the people,” seen as holding the potential to disrupt elite political dominance and strengthen the link between the people and political institutions (Copus Reference Copus2004; Freschi and Mete Reference Freschi and Mete2020; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2001; Steyvers et al. Reference Steyvers, Bergström, Bäck, Boogers, De La Fuente and Schaap2008; Wauters, Verlet, and Ackaert Reference Wauters, Verlet and Ackaert2012). Compared to indirect elections, where a small electorate selects the executive behind closed doors, direct elections invite the masses to choose the executive. While indirect elections are thought to produce pliable executives who lack de facto authority because they are beholden to elite interests, direct elections should usher in strong executives who possess de facto authority since their mandate derives from a broad electorate (Crook and Hibbing Reference Crook and Hibbing1997; Harvey Reference Harvey2022; Linz Reference Linz1990; Micozzi Reference Micozzi2013; Steyvers et al. Reference Steyvers, Bergström, Bäck, Boogers, De La Fuente and Schaap2008) and is autonomous from special interests and elite structures (Gendźwiłł and Swianiewicz Reference Gendźwiłł, Swianiewicz and Sweeney2017; McDonnell and Mazzoleni Reference McDonnell and Mazzoleni2014; Meloni Reference Meloni2015; Stepan and Skach Reference Stepan, Skach, Valenzuela and Linz1994).

As a testament to the transformative potential of direct elections, incumbent regimes have both resisted popular demands for them (McDonald Reference McDonald2021) and replaced direct elections with indirect ones (Minaeva, Rumiantseva, and Zavadskaya Reference Minaeva, Rumiantseva and Zavadskaya2023). Indeed, indirect elections have proven consistent with democratizing elites’ ambitions to maintain their grip on power (Nafziger Reference Nafziger2011; Wollmann Reference Wollmann2008). When the Pakistani military government introduced political decentralization in 2000, they chose indirect elections out of “fear that… if you had direct elections, then real politicians would come up and sort out Musharraf” (Faguet and Shami Reference Faguet and Shami2022). In rural India, local elites shared “an apprehension that if everything was left to the [direct] electoral process, its outcome may not always be desirable.” With indirect elections, they “avoid[ed] such an eventuality,” by “setting boundaries for competitors” (Ghosh and Kumar Reference Ghosh and Kumar2005, 43).

Popular mobilization, political research, and historical precedent lead us to expect direct elections to heighten the barriers elites face in informally capturing political institutions, and consequently, strengthen the executives elected to lead these institutions. Accounts from the Global North and higher levels of government show that direct elections can produce autonomous executives with a muted role for elite structures (Borraz and John Reference Borraz and John2004; Copus Reference Copus2004; Ghimire Reference Ghimire2022; McDonnell and Mazzoleni Reference McDonnell and Mazzoleni2014; Steyvers et al. Reference Steyvers, Bergström, Bäck, Boogers, De La Fuente and Schaap2008; Van Coppenolle Reference Van Coppenolle2022; Wollmann Reference Wollmann2004). In what follows, however, I adapt this logic to local contexts with entrenched elite dominance in the Global South: the places witnessing a shift to direct elections in recent years. In such contexts, I argue that elites may adapt to direct elections by formally capturing the executive, which can mechanically boost the local executive’s de facto authority.

Theory: How and Why Local Elites Adapt to Direct Elections

Direct elections may challenge elite attempts to capture power, but elites adapt to institutional change (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008; Labonne, Parsa, and Querubín Reference Labonne, Parsa and Querubín2021). Successful elite adaptation may be more likely in local contexts with high levels of inequality, low levels of voter awareness, and strong elite networks (Bardhan and Mookherjee Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2000). In such contexts, I argue that direct elections can shift the mode of capture from informal to formal channels, which in turn shapes the de facto authority of the local executive. In sum, formal capture is a rational response to the heightened uncertainty that direct elections create around elites’ ability to maintain informal control of political institutions.Footnote 4 In what follows, I describe the institutional features of indirect elections that promote status quo informal capture, and consequently detail how direct elections’ institutional design may push elites to pursue formal capture.

Three institutional features of indirect elections create favorable conditions for informal elite capture: small-scale elections to form the pool of candidates for the executive; opaque, behind-closed-doors selection procedures for the executive; and the credible divisibility of the executive prize. First, indirectly elected executives are selected from among representatives elected in small sub-constituencies, over which an individual elite typically reigns (Chakrabortty and Bhattacharyya Reference Chakrabortty and Bhattacharyya1993). It is relatively less costly for an elite to ensure by persuasion or coercion that a pliant candidate (his proxy) is elected from his sub-constituency to form the pool of potential executives. In an Indian village, this means a local elite can control his neighborhood of around 50 to 200 people, whom he monitors and interacts with daily. Second, indirectly elected local executives are decided by nomination or vote behind closed doors. This makes it easier for an institutionally external elite to step in and exert influence on the process to select the executive. This is aided by the fact that—in the previous step—each elite can vet and place his own proxy to form the pool of potential executives.Footnote 5

Third, the indirect executive prize is credibly divisible, meaning that multiple executives may reign within a term by dividing it (Arriola Reference Arriola2012; Asano and Patterson Reference Asano and Patterson2023; Firth Reference Firth1957). Dividing the executive prize is credible under indirect elections since an executive leaving office triggers only internal selection of the new executive (behind closed doors). Competing elite factions may coordinate pre-election to share the executive prize over time, reassured that they may control executive succession (Ong Reference Ong2022). To solve commitment problems when elites do not trust each other to uphold their end of the bargain to rotate power, it can be rational for each elite to vet and place a pliable candidate in power as his proxy, reinforcing the rule by pliable candidate logic. This increases each elite’s confidence that a socially subordinate, pliable proxy will rotate power due to a fear of coercion. Even if elite factions do not explicitly coordinate to divide the prize among themselves, the executive prize’s divisibility is useful as an additional tool for elites to retain informal control. In the case studied in this article, village elites at times ask local executives to resign part way into their tenure, as one local executive explained, “to prevent them from becoming too powerful.”Footnote 6

The institutional design of direct elections threatens elite informal control of the executive along these three dimensions. The two step sequence of small, sub-constituency elections to form the pool of executives and behind-closed-doors selection of the executive are collapsed into one step, with direct executives elected from among the masses in community-wide elections. Particularly in contexts characterized by elite factions, no single elite reigns over the entire community, which, in rural India, can mean several hundred to thousands of voters. Plus, the masses likely have different criteria in selecting who they want to represent them, which may not align with elite interests (Besley and Coate Reference Besley and Coate2003). This may heighten elites’ uncertainty about whether they can ensure their pliable candidate is elected as the executive, generating doubt about their ability to pull the strings behind the scenes.

The credible divisibility of the executive prize is also called into question under direct elections because an executive leaving office triggers another vote among the masses (Arriola Reference Arriola2012; Gandhi Reference Gandhi, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris2014; Ong Reference Ong2022). As a result, elites lose certainty that they may control executive succession, which can break down pre-election coordination among factions seeking to reach power-sharing bargains. Such “issue indivisibility” may spark elite conflict and competition (Fearon Reference Fearon1995, 382). Indivisibility also heightens the risk of principal-agent problems between elites and potential proxies. A reduced capacity to push proxy candidates prematurely out of power renders null any insurance against them becoming too powerful. If proxy agents become powerful, enforcing control is challenging for their principals. This becomes more likely if they enjoy an undivided executive prize.

Elites can adapt to the uncertainty brought about by the institutional design of direct elections by pursuing formal capture. When elites’ ability to exert control from behind the scenes becomes highly uncertain and the prize of the local executive meaningfully large, it is rational for elites to directly contest elections themselves.Footnote 7 In particular, when local elites cannot ensure their agents are elected, lose the predictability of controlling succession, and face heightened principal-agent issues, seeking to capture democracy formally can reduce elites’ uncertainty about their ability to maintain political control. In local contexts marked by political violence, clientelism, or more “quotidian forms of distributive politics,” the strongest elite faction—whether by persuasion, coercion, patronage, or even violence—will likely emerge victorious to formally command power (Auerbach et al. Reference Auerbach, Bussell, Chauchard, Jensenius, Nellis, Schneider and Sircar2021, 254).Footnote 8

When informal capture is replaced with formal capture, we should expect a mechanical boost in the executive’s de facto political authority. Relative to socially subordinate proxy candidates, members of the local elite often benefit from various sources of social privilege along ethnic, class, and gendered lines (Deshpande and Palshikar Reference Deshpande, Palshikar, Nagaraj and Motiram2016). These sources of social privilege—on the basis of enduring structural inequalities—can facilitate the political savviness, networks, and procedural knowledge necessary ex ante to command power (Auerbach, Singh, and Thachil Reference Auerbach, Singh and Thachil2024; Heinze, Brulé, and Chauchard Reference Heinze, Brulé and Chauchard2025). Plus, the fact that directly elected local executives face less informal meddling by external elites, and enjoy a large, undivided executive prize, may further strengthen their de facto authority.

This theory generates several expectations about the relationship between direct elections, elite capture, and executive authority. First, direct elections should boost the local executive’s de facto authority. Second, direct elections should reduce informal capture—where elites exert influence on proxy executives from behind the scenes—in favor of formal capture—where elites compete for office and dominate political institutions from within. In what follows, I detail the context in which I test these expectations.

THE CASE

Village Council Presidents in Elite-Dominated Maharashtra

This study is situated in the lowest level of the three-tiered rural Indian decentralized government, village councils, in the western state of Maharashtra.Footnote 9 Village councils provide many rural public goods (Chattopadhyay and Duflo Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004), act as a site to address citizens’ claims (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018), and administer social services (Puri Reference Puri2012). Village councils in Maharashtra comprise from 7 to 17 council members (depending on the population size of the council’s member villages). I focus on who is, de jure, the village council’s most important actor and primary decision-maker: the council president. She is expected to preside over all council meetings, implement resolutions passed by and monitor all bureaucratic functions of the council (Narayana Reference Narayana2005), lead village-wide events, and interface with higher-level bureaucrats (Purohit Reference Purohit2023). In Maharashtra, half of president and member seats are reserved for women, and caste reservations for SCs, Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) are allocated according to population proportions.

Local elites dominate the political and economic landscape of rural Maharashtra. Historically, the numerically dominant Maratha caste controlled Maharashtra’s rural political economy (Dahiwale Reference Dahiwale1995; Ghosh and Kumar Reference Ghosh and Kumar2005; Vora Reference Vora, Mohanty, Baum, Ma and Mathew2007), and communities that have accrued economic and political prestige have built their dominance over time (Sirsikar Reference Sirsikar1964). These elites comprise “the rich peasantry, lawyers with agricultural background, and…businessmen” (Sirsikar Reference Sirsikar1964, 939), but many derived their initial dominance through land. Typically, several sets of elites reside within a village council boundary, each reigning over its own sub-village or ward (Chakrabortty and Bhattacharyya Reference Chakrabortty and Bhattacharyya1993). Each faction often has a geographically concentrated bhauki (patrilineal kinship group) with one or two male bhauki leaders.Footnote 10

Across Maharashtra, elite factions control village politics via “temple politics” and the “chawri system”—quite literally where leaders from each faction or bhauki meet in the village temple or common square (chawri) to “decide everything about politics in advance: from who will be elected, to what they will do in office.” When decisions are made, “[the important villagers] come together, sit at the temple, and resolve the matter.” One village council president described: “In every village, there is a temple where the village deity resides… In this village, we have a temple devoted to Eknath, where the senior villagers who have political experience sit together on every Sunday and make decisions.”Footnote 11

(In)directly Electing the Village Council President

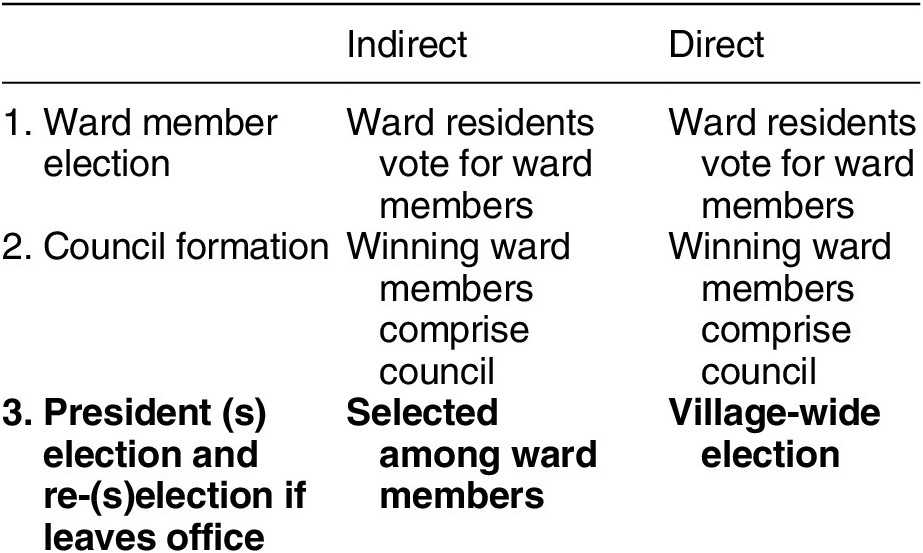

For most of the history of formal local government in Maharashtra, council presidents were elected indirectly. In indirect elections, ward-wise direct elections are first held to elect council ward members.Footnote 12 During the first meeting of the newly elected council, the members decide who will serve as president for the council’s five-year tenure. The indirect president position is easily divisible in this context: if a president resigns from her post, the body reconvenes to select the new president.Footnote 13 This is in contrast to directly elected presidents, whose resignation triggers a village-wide election to re-elect the president.Footnote 14 Table 1 summarizes the institutional features of (in)direct council president elections, with differences bolded.

Table 1. Direct versus Indirect Elections in Indian Village Councils

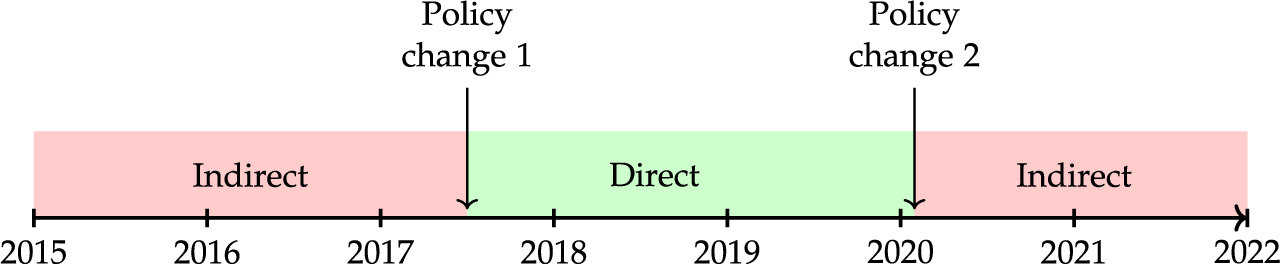

The indirect election of council presidents in Maharashtra came to an abrupt end in early July of 2017, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state government decided that village council presidents would be elected directly (Ghadyalpatil Reference Ghadyalpatil2017). However, direct election of the council president did not remain in place for long. With the election of a new, non-BJP-led state government in 2019, the policy was rolled back. In early 2020, the legislative assembly passed a bill to return to indirect election of council presidents (Times of India 2020). Figure 1 shows the timeline of these policy changes in the period studied in this article.

Figure 1. Timeline of the Electoral Reform in Maharashtra

Some cite development concerns as the reason for pushing direct elections. Direct elections “will enable a bona fide village resident to contest… This may bring in more talent and help the village body focus on development,” stated a rural development officer (Ghadyalpatil Reference Ghadyalpatil2017). Others reveal a political logic. The move to implement direct elections may reflect a political strategy by the state-level incumbent, just as the decision to decentralize governance more broadly reflected political considerations of national and state-level elites (Thomas Bohlken Reference Thomas Bohlken2016). In a state traditionally dominated by local elites at the grassroots level, civil society leaders described the BJP’s approach as an attempt to disrupt “temple politics.” In this sense, party and civil society leaders suggest that the BJP passed the reform precisely because of their limited reach in grassroots politics. As one party leader stated, the BJP sought to “change the face of rural politics” by ushering in a “new kind of local executive with centralized powers.” The actual impact of these reforms on the exercise of executive authority in village councils, however, remains unclear. In what follows, I discuss how the case provides a quasi-experimental set-up to investigate this question.Footnote 15

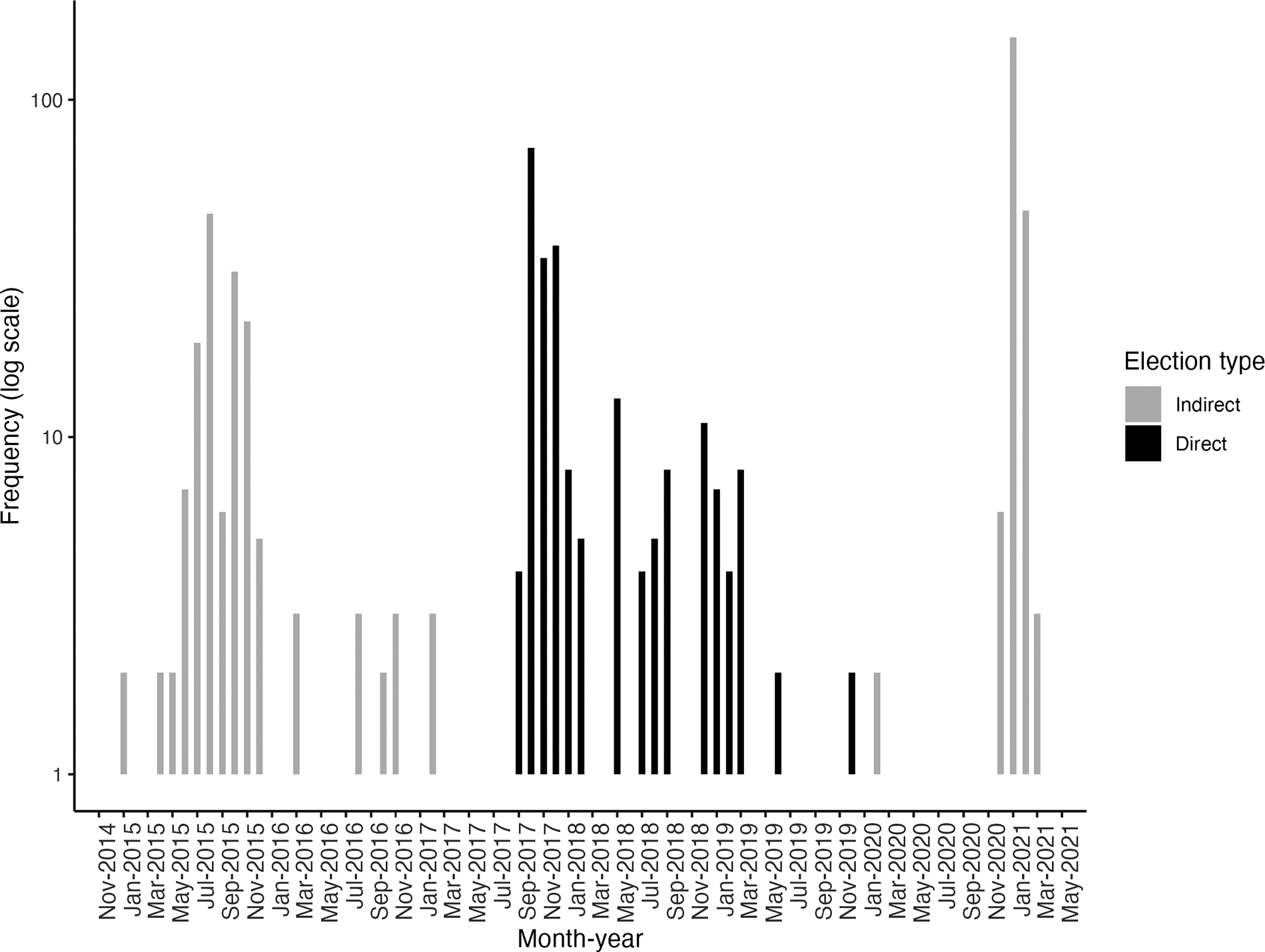

The Quasi-Experiment: Maharashtra’s Varying Electoral Cycles

I argue that whether a Maharashtrian village council’s election took place indirectly or directly is a quasi-experiment, where an “external factor…governs the allocation of treatment among units” in a way that is plausibly independent of processes that determine outcomes (Dunning Reference Dunning2012; Titiunik Reference Titiunik, Druckman and Green2021, 116). A council’s assignment to direct elections depends on where it fell in its electoral cycle during the period when the reform was in place. Councils with elections between July 2017 and January 2020 had direct elections. The rest had indirect elections. Figure 2 shows the distribution of elections from the survey sample used in this article. Historical, qualitative, and quantitative evidence is consistent with the idea that Maharashtrian village council electoral cycles—and thus direct and indirect elections—present a plausibly quasi-experimental setup.

Figure 2. Staggered Electoral Cycles in Maharashtra

Note: This figure represents the distribution of election dates across the survey sample of village councils in Maharashtra. The x-axis represents month-years, spaced every two months. The y-axis represents the log of the count of elections that take place in a given month-year.

Maharashtra’s electoral cycles were largely determined by processes temporally and politically distant from contemporary rural politics. Four historical facts of Maharashtra’s political decentralization lay the foundation for the state’s impressively staggered election schedule. First, village councils were established at different times. Maharashtra has a long history of village government, with some councils established as early as 1869 (in what was then British-ruled Bombay Presidency), with others coming into being at different times ever since (Thomas Reference Thomas2004). Second, the 1958 Bombay Village Panchayats Act required elections every four years, dictated by each individual council’s electoral cycle (Bhat Reference Bhat1974, 9).Footnote 16 Third, the 73rd Constitutional Amendment in 1992 changed election rules once more, now to be held every five years by State Election Commissions (SECs). Maharashtra formed its SEC in 1994 and held new elections in 1995 (Datye Reference Datye and Palanithurai2010). Fourth, and crucially, national reformers in 1992 recommended that states dissolve local bodies to hold synchronized elections, but Maharashtra deviated from this advice (Ghosh and Kumar Reference Ghosh and Kumar2005). At a moment of existential risk to the Congress party, state leaders decided to maintain asynchronous elections—dictated by each individual council’s electoral cycle—rather than to dissolve all councils and risk losing the support of local elites.Footnote 17 , Footnote 18

Interviews with the state’s top election officials suggest that irregular events and bureaucratic arbitrariness further pushed some councils off their historical “paths.” The SEC has ultimate discretion on when and where elections are held. Elections can be held months after or before the termination of an electoral cycle, given local-, state-, or national-level events, like: exam periods that run late or are shifted (teachers often conduct elections), droughts or periods of extreme heat, monsoon flooding, and the occurrence of other elections (because the election machinery is the same, multiple elections cannot be held simultaneously). Otherwise, bureaucratic arbitrariness and capacity issues can shift election timings. The SEC may delay some elections because they cannot conduct them all at the same time, or they may club councils together and hold elections early for efficiency. Importantly, the “assignment” of elections, and thus adjudication of whether such events should advance or postpone elections, is conducted by administrators in Mumbai without ties to faraway rural elites. Finally, evidence does not suggest that village councils could sort into direct or indirect elections. The policy changes were largely unexpected by bureaucrats and village actors—announced less than a month before their implementation—so last-minute sorting was temporally unviable and institutionally improbable.Footnote 19

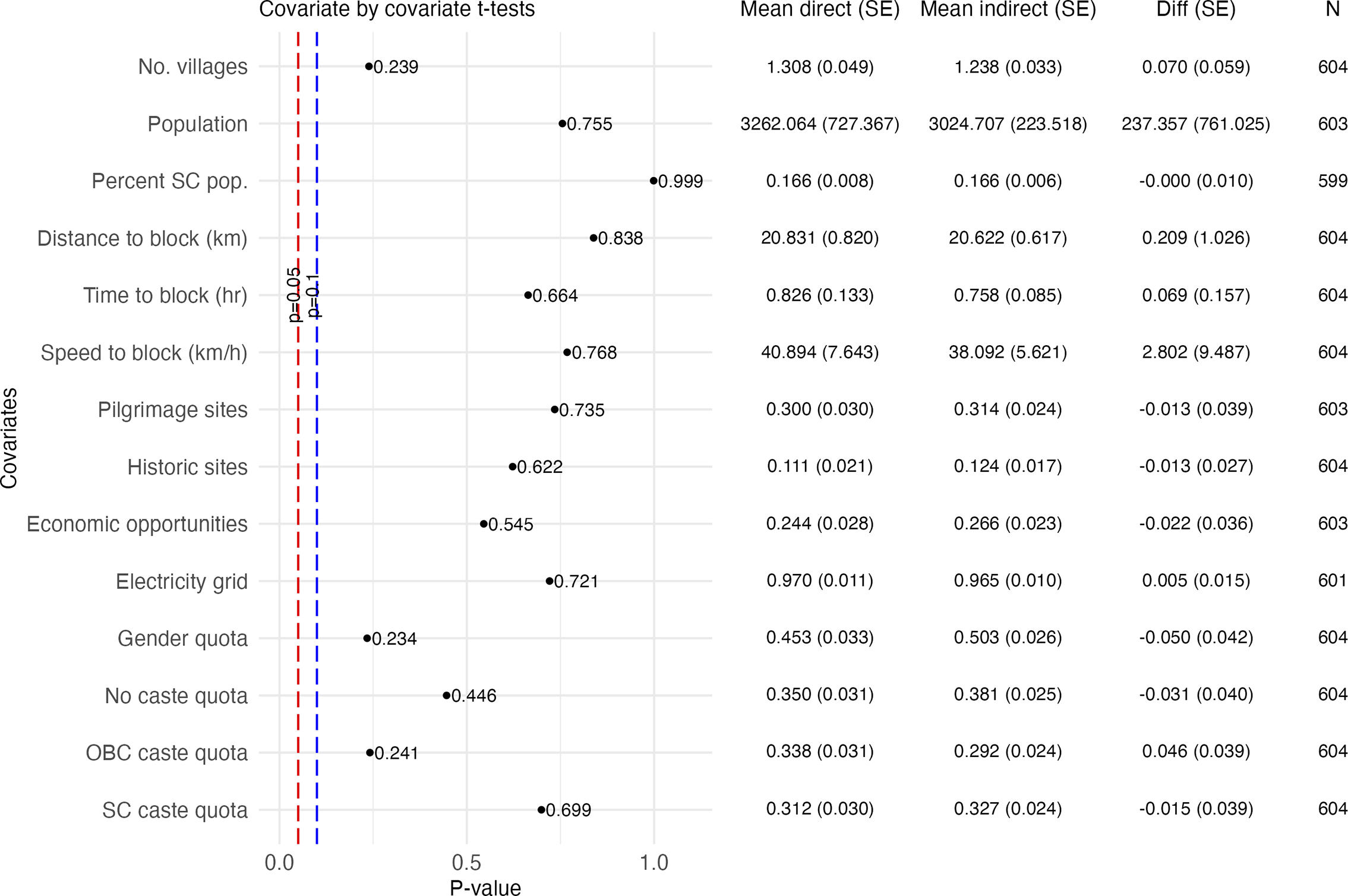

Quantitative diagnostics further support the quasi-experimental set-up. Direct and indirect village councils are comparable in terms of characteristics prognostic of outcomes (Figure 3). Structural variables that are important for theories of elite control—the size of the village, the percent of the village comprising SCs (nondominant castes), a proxy for how rural the village is (distance to the administrative block center), and a proxy for level of development (the speed to reach the block office in km/hr)—are all similar across direct and indirect villages. Variables at the president level that predict her political authority and are theoretically crucial in this context—whether or not the president seat is under a quota for women and lower castes, for example—are also balanced.Footnote 20 While it is impossible to completely rule out unobserved confounders, sensitivity analysis (Appendix D of the Supplementary Material) suggests that unobservables would have to be at least three times as strong as the gender quota variable—a theoretically and empirically crucial variable in predicting outcomes—for the results of this article to change significantly.

Figure 3. Direct and Indirect Villages Look Similar on Covariates

Note: p-values from t-tests comparing mean values across directly and indirectly elected village councils on the left panel. Means and differences in means with standard errors on the right panel.

Maharashtra’s plausibly quasi-experimental elections allow me to compare—with maximum control—direct and indirect villages qualitatively and estimate the impact of direct elections quantitatively. In what follows, I describe the data and designs I use to do so.

DATA AND MULTI-METHOD RESEARCH DESIGN

This article employs a three-pronged multi-method research design, triangulating across qualitative fieldwork, quasi-experimental observational analyses, and survey experimental evidence. Below, I summarize each component of the empirics.

Qualitative Evidence

I leverage three phases of qualitative research: two years of theory building (2018–2020), three months of initial theory testing (June–August 2022), and two months of follow-up theory testing (July-August 2024) fieldwork. This involved over 150 interviews with bureaucrats, presidents, local elites, citizens, and state-level politicians; observations in over 80 councils; and shadowing of 11 local election bureaucracies.Footnote 21 In the main paper, I present controlled comparisons of two councils—one indirectly and one directly elected—from the second round of theory testing fieldwork.Footnote 22 The quasi-experiment of Maharashtra’s elections enhance control in these comparisons. Presented first in the empirics, the controlled comparisons serve two purposes. First, they trace the contextually specific processes through which election type shapes elite capture and de facto executive authority in Maharashtra’s village councils. Second, they provide contextual justification for the measures of de facto authority and (in)formal capture used in the quantitative designs.

Quasi-Experimental Observational Study

To test the theory on a larger scale, I leverage the quasi-experiment, analyzing original survey and administrative data with novel measures of de facto political authority and elite capture. This design tests the main relationship—whether direct elections increase the president’s de facto authority—and probes the proposed pathway—whether direct elections shift elite capture from informal to formal channels.

The survey data were collected from 2020 to 2022 in 604 village councils across five geographically spread districts. These districts are large and populous, some the size of countries.Footnote 23 Using surveys of each village council’s president, village bureaucrat, a facilitated discussion between the president, vice president, and bureaucrat, and a gender and caste-balanced sample of six citizens, these data measure the council president’s de facto authority as well as indicators of informal and formal capture.Footnote 24 I also leverage a novel administrative dataset that required digitizing all paper records of president resignations in one district with over 1,300 villages. I describe the outcome measures from both of these data sources directly preceding their analysis. Leveraging the quasi-experiment, I estimate the impact of direct elections on outcomes by simple comparisons of means across direct and indirect councils.

Survey Vignette Experiment

I conducted a preregistered follow-up vignette experiment among 2,347 voters in out-of-sample North Maharashtra as a partial test of the proposed pathway.Footnote 25 By randomly varying a hypothetical president’s caste and gender, I probe whether formal capture causes presidents to enjoy increased perceptions of de facto authority. While the observational design tests if direct elections cause higher authority, lower informal capture, and higher formal capture, it cannot test whether direct elections cause increased authority through formal capture. This experiment probes the latter half of the proposed relationship: the causal link between formal capture and de facto authority. Design, analysis, and outcome details precede the presentation of experimental results.

THE CONTOURS OF CAPTURE AND EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY UNDER (IN)DIRECT ELECTIONS

To test the expectations of this article’s theory, I first present controlled comparisons of two village councils with similar structural characteristics that vary in their election type.Footnote 26 The first case demonstrates how indirect elections empower local bosses to capture political institutions informally, putting in place pliable proxy presidents who enjoy little de facto authority. The second case shows how direct elections challenge elite strategies of informal capture; instead, local elites contest and win president elections, ultimately leading to formal governance by local bosses who firmly command de facto authority.

Indirect Elections, Informal Capture, and Stymied Presidents

In Dahigaon village, it did not take long to learn the name Sadhu, one of the village’s “big people:” a Maratha landowner whose bungalow, adjoined shop, ornate personal temple, and sprawling rice fields were centrally located in the village.Footnote 27 During our interview, Sadhu was forthcoming in explaining his and other Maratha bhauki leaders’ outsized role in shaping the village’s indirect elections. “We call ourselves the father group,” he described, “and when the dates of the elections are declared, we meet in the temple to finalize our candidates. They all fill the [candidacy] form in front of us.” Another member of the “father group,” the leader of the neighboring bhauki, described how the bhauki leaders ensure ward elections are unopposed so their candidates win and ultimately become president. “We are the ones who ensure that the election remains unopposed,” he explained. For the current president, he continued, “We’re the ones who made him the president… we ensured that everyone who filed against him withdrew his form. In the end, only one other form was left. So, at 9:00 p.m., we called that person to the temple… and made him withdraw his form.” Through persuasion, coercion, or perhaps violence, Dahigaon’s “father group” ensured their proxies formed the pool of candidates for the local executive.

Dahigaon’s bhauki leaders agreed in the preelection temple meeting to divide the executive prize between their candidates. They coordinated the resignation of each president. One bhauki leader’s president would resign after one year, the next after three years, and the last year would go to the final bhauki leader’s president. The candidate of the most dominant elite faction, Sadhu’s bhauki, would preside for three years. When I asked Sadhu why he selected Rohit Mane—a relatively poor member of a nondominant caste group—as his candidate, he referenced Rohit’s lack of political experience and pliability: “I chose Rohit because he has never had a chance [to participate in politics]… He is my disciple only. He never disobeys my word.” He further underlined that Rohit expresses indebtedness to his patronage. He shared, “I mentioned that it would be nice to repaint my temple. Rohit responded by saying ‘You’ve done so much for me—I’ll definitely do that.’ Even being poor, he spent 35,000 rupees to repaint my temple. He did all this because I supported him [in becoming president] and he is grateful to me.”

I observed firsthand how Dahigaon’s elites exert informal influence over the local executive from the sidelines. When I returned to Dahigaon in search of Sadhu, his neighbors informed me that on Tuesdays, he attends the official meeting between council presidents, the Block Development Officer, and village bureaucrats. On another visit, I sought to meet Rohit Mane, the council president and Sadhu’s candidate, for a private interview. Shortly after Rohit entered the meeting place, so did Sadhu, who promptly sat next to us, I infer, to monitor the interview. In the interview, Rohit described how Sadhu influences council decision-making behind the scenes: for example, Sadhu recently decided that the drinking water tank should be set up next to his temple. Another bhauki leader admitted that coordinating president resignations prevents their candidates from accruing authority and facilitates elites’ informal control: “The president does not do the work. The people backing the president do… If a president serves for a short period before resigning, it takes almost two years just to learn. In such cases, the village leaders… step in because they know everything.” In another village with indirect elections, the president explained how elites benefit from this system: “If I ask someone to resign and install another as president, I get all the credit and I keep all the control. I build my image and power.”

Elite control of village politics is no secret to Dahigaon’s citizens. One farmer from a subordinate caste community stated that the bhauki system determined all village decisions: “My brother, my bhauki!” he yelled, puffing out his chest to imitate the dominant forces involved in Dahigaon’s elite factions. When I asked a DalitFootnote 28 woman why village elites install socially subordinate candidates only to then make them resign, she extended a clenched fist, stating, “to keep their hold.” One daycare worker described how citizens who oppose elite dominance face suppression in public forums and private interactions. If citizens speak in the village-wide meeting, she said, “[the elites] pressure them. They say: ‘what do you know? Sit back down.’” If citizens express discontent, she continued, “it creates trouble.” Citizens are excluded from temple meetings and electoral processes: “Decisions about who will be elected don’t reach us. We only learn who they declare will be president after the fact.”

Direct Elections, Formal Capture, and Empowered Presidents

Vishal Wagh, the directly elected president of Shelgaon Budruk village, stood in stark contrast to Rohit Mane, neighboring Dahigaon’s indirectly elected, softspoken president of modest means. In Marathi,Footnote 29 Wagh—the surname of a locally prominent subcommunity of the Maratha caste-group—means tiger. Vishal Wagh wore clunky gold jewelry—rings, a cuff, and a long chain—each piece adorned with tiger heads baring their teeth. A large tiger decal covered the rear window of his foreign car. Vishal Wagh, whose father was Shelgaon Budruk’s patil (roughly understood as a dominant, landholding patron) since its inception until he recently passed, led the village’s dominant bhauki.

Before direct elections were implemented, preelection coordination among temple elites governed village politics. Vishal explained, “for 25 years… elections used to be unopposed. Two to three people from each bhauki collectively decided among themselves who should contest the election. Then they informed the others.” Power was shared among the village’s elite factions through resignations: from 2007 to 2012, for example, there were three presidents—each a proxy for each bhauki’s leader.

Direct elections broke down this system. Unable to come to a preelection agreement, the bhauki leaders contested the president election against each other. Ajay Mali, defeated president candidate and rival bhauki leader, described preferring the old system: “[the] unopposed system system is a good one; it prevents conflict and avoids unsavory behavior.” When I asked what he meant by unsavory behavior, he responded, “money and all of that… now, money and muscle get prioritized over having the right people [as president].” In the temple meetings before, each elite group used to have a say: “When there used to be unopposed elections, all of us [leaders] used to speak,” Ajay continued. With direct elections, however, control has become centralized in the hands of the Wagh bhauki, who has, he explained, “become assertive and self-centered.”

Several citizens underlined how Vishal Wagh’s elite characteristics—muscle power, political resources, and wealth—contributed to his de facto authority as president. One citizen asked rhetorically, “Who can resist muscle power and intimidation?” Another citizen highlighted how, compared to the other bhauki leaders, “[Vishal] has the upper hand when it comes to having connections and muscle power.” One lower-caste citizen, in explaining why Vishal Wagh commanded authority as president, highlighted his relative affluence: “President has a four-wheeler car. What do we have?” Vishal Wagh’s local financial dominance was obvious to anyone who visited the village council office, where, adjacent to the front entrance, there stood a large sign for “Wagh Enterprises Construction Company.”

A neighboring village witnessed similar dynamics with the shift to direct elections. The village bureaucrat highlighted how “power and money,” allowed the current president and prominent landlord to win against another bhauki leader. For example, on election day, “the [current] president tore up the road leading to one of the [voting] centers, preventing people from going there… [and] a man related to the president parked a Toyota Fortuner in front… and sat there, acting aggressively. The idea was to stop people from coming to vote.” He further highlighted how the president’s de facto authority derives from his social privilege, stating that “the president’s family has wealth, land, and power.” This was obvious to me as well. As in the cases of Sadhu in Dahigaon and Vishal in Shelgaon Budruk, the president’s large bungalow, adjoining shop, and personal temple occupied the central village square. His iPhone, foreign car, and the five tractors parked outside of his home further underscored his consolidation of wealth and status. “There are better people than the current president’s family, but they are suppressed…” the bureaucrat lamented.

DIRECT ELECTIONS BOOST THE LOCAL EXECUTIVE’S AUTHORITY

To test the main expectation of this article’s theory—that direct elections increase the local executive’s de facto authority—I draw on survey data from the observational design. Results show that directly elected presidents enjoy a substantively and statistically significant de facto authority advantage compared to their indirect counterparts.

Measures. De facto political authority, while conceptually distinct, may be correlated with social privilege and fear, and thus hard to measure independently of these concepts. For this reason, rather than asking respondents “who is the most influential around here”—which may produce responses grounded in the president’s social status or ability to instill fear—I triangulate across three behavioral and two perception-based outcomes that measure the president’s authority via involvement in the activities that de jure, fall squarely within her domain.Footnote 30 Behaviors include the proportion of time the president speaks in a facilitated group discussion with the vice president and council bureaucrat (with values between 0 and 1); a binary variable denoting whether citizens nominate the president to represent the village in a meeting with a higher-level bureaucrat (the Block Development Officer); and a binary variable measuring whether citizens report that the president is the main leader of village-wide events (like inaugural events). Perceptions include a binary variable measuring whether a third-party observer perceived the president to be the most influential actor in the group discussion and a binary variable measuring whether the president perceives herself to be the main decision-maker in the monthly meeting of the council (masik sabha), where policy decisions are made. It is important to integrate both behaviors and perceptions in measuring de facto authority. This is because conceptually, de facto authority is not only observed in the behaviors of the executive, but is also more diffuse—something that local informants may judge based on their knowledge of their local communities and interactions with local government. De facto authority is both embodied by the executive and recognized by community members (Cruz and Tolentino Reference Cruz and Tolentino2019).

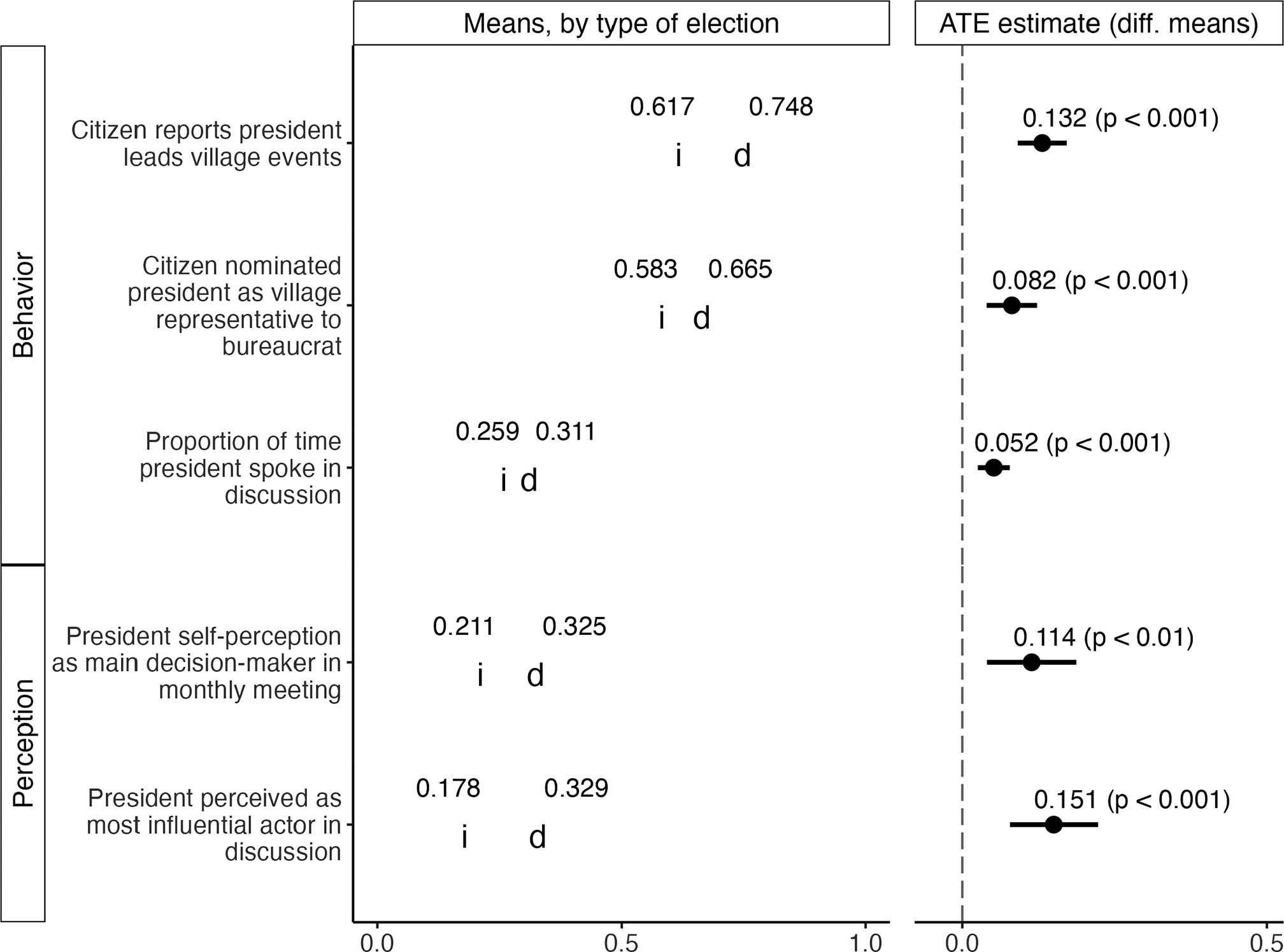

Results. Figure 4 shows that directly elected local executives enjoy more de facto authority than their indirectly elected counterparts. The left panel presents means for indirectly elected presidents (denoted i) and directly elected presidents (denoted d) for all de facto authority measures. The right panel displays estimates of the average treatment effect of direct elections via differences in means, as well as 95% confidence intervals and p-values in parentheses. Directly elected presidents score higher than indirectly elected presidents across all measures. All treatment effect estimates are statistically significant at conventional thresholds.Footnote 31

Figure 4. Directly Elected Presidents Enjoy More De Facto Political Authority

Note: Means for direct (d) and indirect (i) presidents on the left panel, and ATE estimates with 95% confidence intervals on the right panel (p-values in parentheses); citizen outcomes use clustered SEs at the village council level.

Directly elected presidents behave in ways that indicate higher de facto political authority than indirectly elected presidents. During a discussion with the other prominent members of the council, directly elected presidents spoke significantly more than their indirectly elected counterparts (+5.2 percentage points more often). Enumerators present in these facilitated discussions noticed these differences: directly elected presidents were nearly twice as likely to be perceived as the most influential actor in the discussion than indirectly elected presidents (+15.1 p.p.). Enumerators were unaware of hypotheses about direct elections’ impact.

Citizens recognized directly elected council presidents’ enhanced de facto authority. They were more likely to nominate the president as the village representative to speak to the bureaucratic head of development in the region—the Block Development Officer—if the president was directly elected (+8.2 p.p.). They were also more likely to report that the directly elected president is the leader of village-wide events, rather than other actors (+13.2 p.p.). Finally, presidents themselves self-reported to be the main decision-maker in the village council’s monthly meeting—the internal meeting where policy decisions are made and budgets are allocated—significantly more frequently when they were directly elected (+11.4 p.p.).Footnote 32

WHY DIRECT ELECTIONS BOOST THE LOCAL EXECUTIVE’S AUTHORITY

I propose that direct elections may increase the local executive’s de facto authority through shifting the elite capture of political institutions from informal to formal channels.

Direct Elections Shift Elite Capture to Formal Channels

I leverage the observational design to test if direct elections increase formal elite capture and decrease informal elite capture. Results are consistent with this explanation: directly elected presidents are more likely to exhibit local elite characteristics, while indirectly elected presidents are more likely to face indicators of local elite interference.

Measures. Formal capture occurs when elites command political institutions from within.Footnote 33 I operationalize formal elite capture as the demographic representation of elites among council presidents using six measures. In Maharashtra, rural elites often benefit from caste, class, and gender privilege (Deshpande and Palshikar Reference Deshpande, Palshikar, Nagaraj and Motiram2016). I measure caste privilege by (i) a binary measure for whether the president is Maratha and (ii) the average proportion of land held by their caste in the village. I measure class privilege by binary measures for whether the president owns (iii) land, (iv) a pacca (a concrete, rather than thatched or mud) house, and (v) a vehicle larger than a motorcycle or bicycle (a three- or four-wheeler). Gender privilege is measured by a binary variable denoting (vi) whether the president is a man.

Informal capture occurs when elites exert influence on political institutions from behind the scenes. I measure this concept via seven binary indicators. Explicit measures include whether (i) the president reports that a rich landowner who is not elected to the council influences council decisions, (ii) citizens report that the former council president or other unelected villagers lead village-wide events (like inaugurations), and (iii) citizens nominate the former president or other unelected villagers to represent the village to the Block Development Officer. Implicit measures include whether (iv) the president was elected unopposed and (v) the president reports resignations in their council tenure. Qualitative evidence suggests that village elites seek to ensure unopposed elections to control political selection, and that coordinated resignations are a key tactic to exert informal control—often to share power among themselves and/or to prevent presidents from becoming too powerful.Footnote 34 I validate president resignation self reports via (vi) citizens’ reports of resignations during the council tenure and (vii) actual resignations from an administrative census of one district.Footnote 35

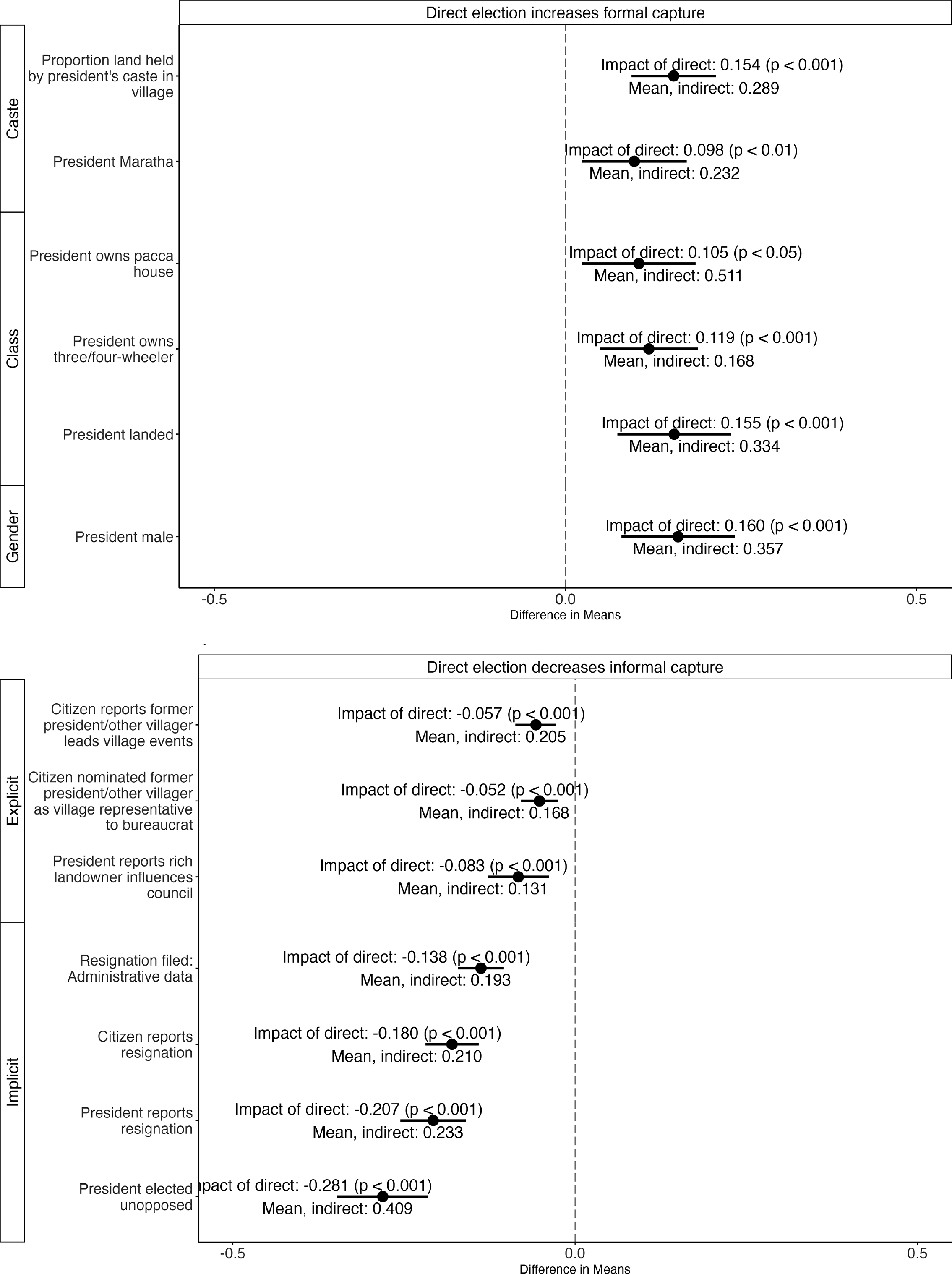

Results. Direct elections increase the formal capture of the president position. The top panel of Figure 5 presents estimates of the average treatment effect of direct elections on presidents’ characteristics. Whereas indirect presidents come from relatively less dominant caste, class, and gender backgrounds—evidence in line with the informal control via proxy hypothesis—directly elected presidents are strikingly more likely to share the demographic characteristics of the local elite, enjoying social privilege along caste, class, and gender lines. On average, they are more likely to: have a larger proportion of land belonging to their caste in the village (15.4 percentage points more land than indirect presidents); belong to Maharashtra’s dominant caste, the Marathas (+9.8 p.p.); own a pacca house (+10.5 p.p.); own a large vehicle (+11.9 p.p.); own land (+15.5 p.p.); and be a man (+16 p.p.). Here, caste and gender measure the self-reported caste and gender of the president, not the president seat’s reservation status, which is balanced across direct and indirect villages (Figure 3).Footnote 36

Figure 5. Direct Elections Replace Informal Capture with Formal Capture

Note: ATE estimates with 95% confidence intervals (p-values in parentheses); citizen outcomes use clustered SEs at the village council level.

At the same time, the bottom panel of Figure 5 shows that direct elections decrease instances of informal elite control of the executive position. In terms of explicit indicators, directly elected presidents are less likely to report that rich landowners influence the village council (−8.3 p.p.) and citizens are less likely to report that unelected interests lead village events (−5.7 p.p.) or should serve as the village representative to the Block Development Officer (−5.2 p.p.). Direct elections also decrease the likelihood of implicit indicators of informal elite influence. Directly elected presidents are far less likely to be elected unopposed (−28.1 p.p.).Footnote 37 They are also less likely to report resignations occurring in their tenure (−20.7 p.p.); citizens’ reports (−18 p.p.) and actual resignations filed (−13.8 p.p.) validate this finding. In addition to, or perhaps as a result of, enjoying significantly higher levels of demographic dominance, directly elected presidents face less informal meddling by external elites. Plus, the fact that directly elected presidents are less likely to have their tenure cut short may allow them to accrue further authority in enjoying the large executive prize.Footnote 38

Measuring how elites control institutions informally is challenging because they have incentives to do so in subtle ways. Implicit measures of informal capture are thus observationally equivalent to other phenomena that do not indicate elite influence: in particular, unopposed elections and resignations. My data do not allow me to test whether instances of unopposed elections are the result of elite manipulation. However, the fact that this measure moves together with more explicit measures of informal capture increases our confidence that it captures dimensions of the underlying concept.Footnote 39 To evaluate whether resignations are the result of elite coordination rather than illness, a loss of confidence, or other exogenous events, I conducted follow-up phone interviews with all presidents reporting resignation in the survey sample. 82% of those who responded (87 out of 92, a response rate of 95%) explicitly reported that elite interests in their village decided that they would resign. One president stated this plainly: “It is the bhauki-gavki (elite villagers) in the villages that forces…such systems of resignation. When I became president and started generating interest, I had to resign because I gave [them] my word.”Footnote 40

Formal Capture Causes a De Facto Authority Boost

The previous sections show that direct elections increase the executive’s de facto authority and decrease informal capture in favor of formal capture. But does formal capture cause increased de facto authority? I leverage a preregistered survey experiment to test this by varying the degree of demographic dominance (here, gender and caste) that presidents enjoy as a proxy for the formal capture of the local executive position by local elites.Footnote 41 Survey experiment results show that coming from more elite backgrounds causes a de facto authority boost among hypothetical council presidents.

Design and analysis. The experiment features a vignette of a hypothetical council president, where her gender and caste vary, with two possibilities each. Voters are assigned using simple randomization (equal probabilities of assignment to each condition) to one of four hypothetical presidents: dominant caste (Maratha) woman, dominant caste (Maratha) man, subordinate caste (Dalit) woman, or subordinate caste (Dalit) man. The gender of the president was manipulated using gender pronouns combined with an obviously female (Bharti) or male (Rohit) first name. Caste was manipulated using surnames with obvious caste connotations in this context: Marathe (Maratha, dominant) or Kamble (Dalit, subordinate). I hold constant three other dimensions: the age of the president (the mean age of the president sample from the previous study), the fact that the village is numerically dominated by Marathas, and the amount of time the president has been in office (1 year). The vignette was worded as follows (bracketed words varied with treatment condition).

Now, I’ll tell you about the president of a village council here in Maharashtra. I’m interested in your opinions about this president. [Bharti/Rohit] [Marathe/Kamble] is a 42-year old [female/male] president. [She/he] is a [Maratha/Dalit] president, in a village where more than half of people are Maratha. [She/he] has been the president of the village council for one year. Based on your experience and knowledge of the way village councils work in reality on the ground, what type of experience do you think [Bharti/Rohit] [Marathe/Kamble] will have?

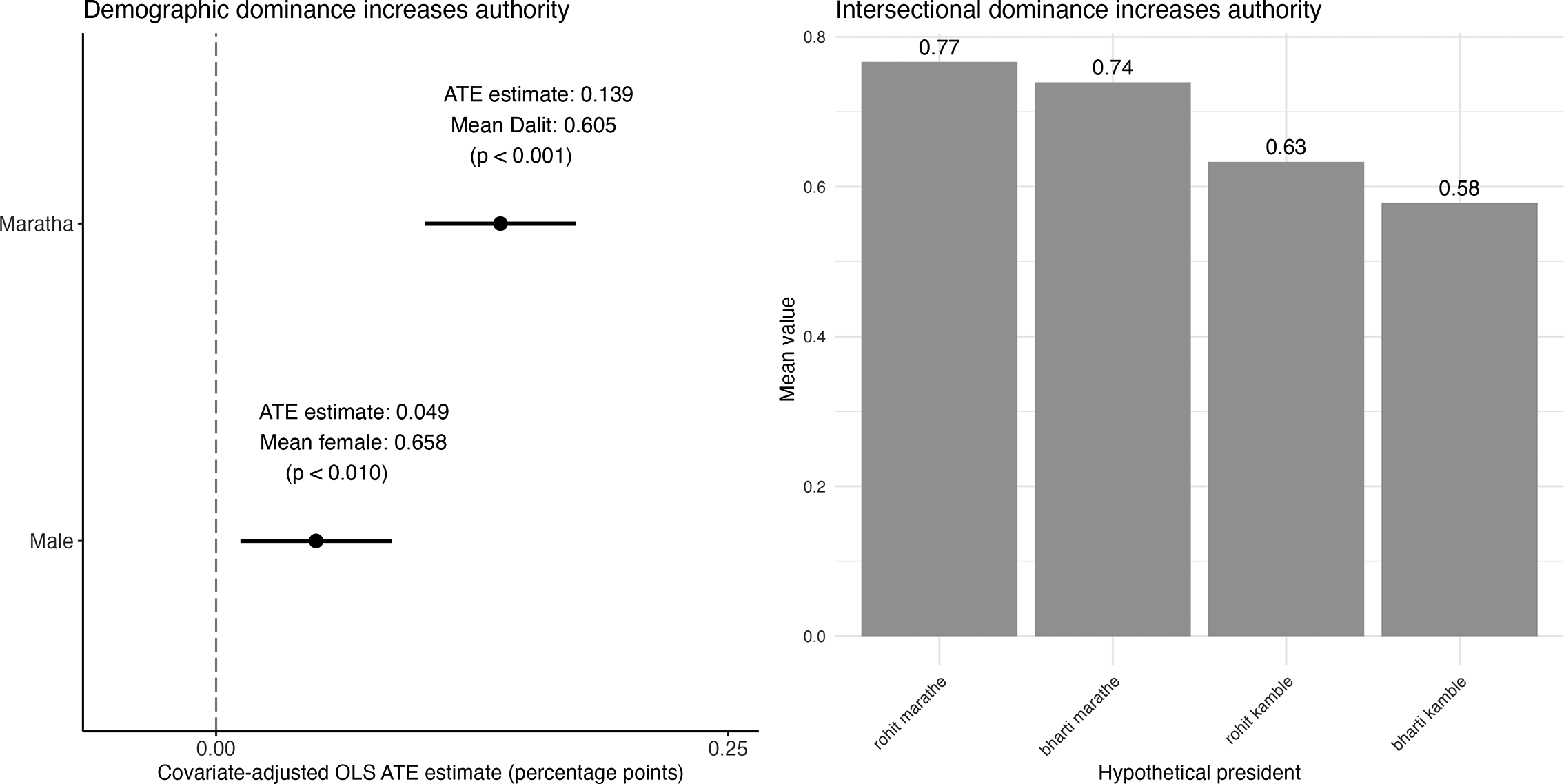

I measure the president’s de facto authority via voters’ responses to the question: “Imagine there are some important decisions to be made in the village. As you probably know, sometimes other people—influential people in the village, village elders, other council members, or family members—step in and take village decisions in the place of the president or are generally more active than the president. Sometimes however it is the case that the president is the most influential actor. In this village, do you think that a president like [Bharti/Rohit] [Marathe/Kamble] would be the one who is the most active in taking village decisions, or do you think it would be someone else?” The binary variable is coded as 1 if the respondent responded “the president” and 0 if they responded “someone else.” To estimate the average impact of caste and gender dominance on the president’s de facto authority, I run preregistered covariate-adjusted OLS regressions.Footnote 42 I also report a preregistered exploratory analysis of mean levels of de facto authority by each intersectional identity, to investigate how Maratha men may benefit differently than, say, Dalit women.Footnote 43

Results. The left panel of Figure 6 demonstrates that Maratha and male dominance cause voters to expect a hypothetical president to enjoy more de facto authority. Hypothetical Maratha (+13.9 p.p.) and male presidents (+4.9 p.p.) were more likely than their Dalit and female counterparts to be perceived as the ones who wield power in village decisions. Moreover, de facto authority seems to accrue with intersectional dominance. The right panel of Figure 6 shows that, descriptively and suggestively, Maratha men are at the top of the food chain (77% are predicted to be the de facto decision-makers). They are nearly 20 percentage points more likely to enjoy de facto authority than presidents who face both gender and caste disadvantage: Dalit women (58%). Together, these results suggest that when members of elite groups access power formally, this causes an increase in perceptions of the local executive’s de facto authority.

Figure 6. Demographic Dominance Boosts De Facto Authority

Note: Left panel reports two covariate-adjusted OLS regressions of the impact of president gender dominance and caste dominance on the authority measure. Right panel reports means of authority by experimental condition. Authority variable is binary: 1 if the respondent reports the president would be the most active in village decisions, 0 if others.

Interestingly, these results indicate that caste dominance is more pronounced than gender dominance in determining de facto authority. This may be a methodological artifact: in ensuring that respondents perceived the Maratha president as enjoying caste dominance, caste may have been primed more than gender in the vignette (the village was fixed to be numerically Maratha-dominated). However, it could also indicate that respondents believe caste dominance—perhaps through its association with wealth and networks—can outweigh gender inequalities within castes. In other words, Maratha women benefit from belonging to powerful bhaukis in village politics. Conversely, Dalit men’s gender advantage may be outweighed by coming from outside of entrenched elite circles. This provides fertile ground for future research.

A few caveats to interpretation are in order. Establishing “mechanisms” is a thorny endeavor. The design of this experiment cannot test whether direct elections cause a de facto authority boost through formal capture; rather, it establishes a link between formal capture and de facto authority—a partial test of the causal chain.Footnote 44 However, documenting a causal link between demographic dominance and de facto authority may increase our confidence in the idea that direct election can increase the local executive’s de facto authority through formal capture of the executive post.

DISCUSSION: BEYOND ELITE INVARIANCE?

In decentralized contexts with entrenched elite interests and durable social inequalities, this study theorizes and documents the hard limits of electoral reforms that aim to deepen democracy. As intended and expected,Footnote 45 direct elections can boost the de facto political authority of the local executive. However, this study documents an important caveat: directly elected local executives may be empowered merely because local elites adapt to electoral reform, formally capturing democracy. Rather than bringing democracy closer to the people, this case represents a form of elite invariance.

Both informal and formal elite capture pose a threat to democracy, albeit in different ways. In the short term, informal capture under indirect elections delegitimizes both state power and representative democracy, when historically marginalized groups are represented descriptively but lack power substantively as the locus of governance shifts to informal elite back-channels. Formal capture under direct elections, on the other hand, centralizes state power in the hands of the unrepresentative few, legitimizing elite domination. In the long term, it is unclear which mode of capture is more conducive to the stability of elite control. This is an important area of future research, particularly in crafting solutions to undo elite dominance.

Is there a way out? To conclude, I suggest that wresting power from traditional elites’ grip may be possible in the presence of additional, overlapping institutional constraints. A challenge with the idea that direct elections may empower a representative citizen to access office and govern effectively is that direct elections, by themselves, do nothing to prevent local elites from stepping in and capturing the executive office. However, direct elections in tandem with binding constraints on political selection may allow members of nonelite groups not only to access the corridors of power, but also to enjoy the de facto authority that executive office promises. I investigate whether reservations for members of India’s most historically oppressed caste group (SCs), when overlapping with direct elections, may prevent local elites from capturing power, all the while empowering marginalized citizens to enjoy the de facto authority boost that direct elections can offer.

When direct elections overlap with quotas for SCs, elite dominance may be credibly challenged. Appendix H of the Supplementary Material presents suggestive evidence that directly elected SC presidents are less likely to come from dominant caste backgrounds (by definition); are less likely to face informal meddling; and still enjoy the direct election de facto authority boost. Qualitative evidence supports the idea that binding constraints on political selection in tandem with direct elections may be a fruitful institutional innovation to undo elite domination and empower representative executives. One directly elected SC president underlined this possibility: “Four years ago, I would not have been able to speak so confidently in front of you.” She continued, “…it’s better to be a [president] elected from among the people… if a [president] is elected from among the people, she gets a different kind of power from a [president] who is elected from among the members!”Footnote 46

Upending the standing political order, however, is not costless. As and when elite dominance is undone, we may expect new strategies of elite backlash—for example, violence—to emerge. Survey experimental evidence shows that hypothetical SC presidents, when they become powerful, are perceived to be most likely to face threats and violence from elites (Appendix H of the Supplementary Material). One directly elected SC president who won awards for her contributions to her village’s development faced threats from a local boss, who told her, “resign… or I will eliminate your family overnight. I will kill you like in the Khairlanji massacre. I won’t even let the investigation happen.” Another directly elected SC president shared, “[the influential villagers] don’t like that I was elected directly through the people and the SC reservation.” A Maratha bhauki leader in her village underlined his distaste for the shift in power relations, stating, “Democracy has been undermined by Dalit dictatorship now.”Footnote 47

Whether overlapping reforms to deepen democracy can disrupt elite dominance and empower local executives in the long term remains an open question. However, as this study shows, local elites possess a remarkable ability to adapt to changing institutional constraints in order to maintain political dominance. When and how elite persistence can be durably substituted with a deepened form of representative local democracy—without the threat of violent elite retribution—is a crucial area of future research.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425101068.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QGH7P4.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Feyaad Allie, Leonardo Arriola, Kirk Bansak, Graeme Blair, Rachel Brulé, Jennifer Bussell, Simon Chauchard, Pradeep Chhibber, Amanda Clayton, Aditya Dasgupta, Thad Dunning, Erin Hartman, Nahomi Ichino, Andrew Little, Pratik Mahajan, Michaela Mattes, Soledad Artiz Prillaman, Johanna Reyes Ortega, Scott Straus, Martha Wilfahrt, Kamya Yadav, four anonymous reviewers, and participants in the UC Berkeley second year writing seminar, CPD working group and Africa workshop at UC Berkeley for their valuable comments on this article. Renuka Kshirsagar and Radha Kulkarni provided excellent research assistance.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the Center for Effective Global Action (UC Berkeley) and the Global Democracy Commons (UC Berkeley).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Boston University, University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard University, and certificate numbers are provided in the Supplementary Material. The author affirms that this article adheres to the principles concerning research with human participants laid out in APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research (2020).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.