Introduction

Given the prominence of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in terms of evidence-based practice, including the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative, several authors (Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015; Kennerley and Clohessy, Reference Kennerley, Clohessy, Mueller, Kennerley, McManus and Westbrook2010; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011b; Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2012) have noted a paucity of research about CBT supervision. Despite this relative lack in comparison with CBT at large, there have been several relevant studies more recently (including Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2016; Törnquist et al., Reference Törnquist, Rakovshik, Carlsson and Norberg2018; Weck et al., Reference Weck, Kaufmann and Witthöft2017), but few about supervision within training settings.

There are a number of useful definitions of supervision, including several specific to CBT supervision (Bernard and Goodyear, Reference Bernard and Goodyear2014; Lane and Corrie, Reference Lane and Corrie2006; Pretorius, Reference Pretorius2006). The definition of supervision most fitting with this piece of research is Milne’s (Reference Milne2007):

‘The formal provision, by approved supervisors, of a relationship-based education and training that is work-focused and which manages, supports, develops and evaluates the work of colleagues (supervisees). The main methods that supervisors use are corrective feedback on the supervisee’s performance, teaching, and collaborative goal setting. It therefore differs from related activities, such as mentoring and coaching, by incorporating an evaluative component.’ (p. 439 and 440)

In order to carry out effective CBT, clinical supervision is accorded importance by a number of national agencies, including the Department of Health (2004). IAPT and the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) require trainee and qualified cognitive behavioural (CB) therapists to receive regular supervision (Latham, Reference Latham2006; Turpin & Wheeler, Reference Turpin and Wheeler2011).

Studies suggest that supervision may have a positive impact on training, clinical practice and client outcomes. Mannix et al. (Reference Mannix, Blackburn, Garland, Gracie, Moorey, Reid and Scott2006), Heatley et al. (Reference Heatley, Ricketts and Forrest2005) and Shlomskas et al. (Reference Shlomskas, Syracuse-Siewert, Rounsaville, Ball, Nuro and Carroll2005) showed in their (time-limited) studies that supervision maintains training gains. Falender and Shafranske (Reference Falender and Shafranske2004) and Bambling et al. (Reference Bambling, King, Raue, Schweitzer and Lambert2006), among others, found that supervision improves patient outcomes as well as promoting safe practice, although it is difficult to measure the ongoing influence of clinical supervision upon client outcomes (Scaife, Reference Scaife2010) and a systematic review found that its impact on client outcomes was not convincing (Alfonsson et al., Reference Alfonsson, Parling, Spännargård, Andersson and Lundgren2018). Öst et al. (Reference Öst, Karlstedt and Widen2012) found that inexperienced trainee clinical psychologists carrying out CBT can achieve comparable client outcomes to experienced therapists, when supervised by the latter group. Their study was within a clinical psychology training programme in Sweden, and so results may not be generalizable to CBT-only training, but does lend weight to the suggested link between training and client outcomes.

As Milne (Reference Milne2016) highlights, the picture has started to improve since 2010 with the publication of several studies and research-focused books about CBT supervision, some considering which factors may be important. Milne et al. (Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011b) considered engagement with experiential learning and ratings of acceptability as one stage of developing a competency measure (SAGE). Recently the focus has been taken in other directions, such as within internet-based CBT training (Rakovshik et al., Reference Rakovshik, McManus, Vazquez-Montez, Muse and Ougrin2016). Supervision was positively linked with CBT competence after training, compared with trainees who had not received supervision.

Within the existing literature there are assertions that structure of supervision is important (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997; Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), but at present the evidence is not completely convincing. While Kljenak (Reference Kljenak2011) concluded in a literature review on CBT supervision that using a theoretical framework improves supervision, Milne and James (Reference Milne and James2000) found that fidelity to managing the structure of CBT supervision was very poor. They also noted that supervisors focused on certain aspects (such as reviewing formulations) to the detriment of others. Supervisee ratings of supervision have been considered on a small scale in a few cases (Johnston and Milne, Reference Johnston and Milne2012; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe, Breese, Boon, Raine and Scarratt2011a; Uys et al., Reference Uys, Minaar, Simpson and Reid2005; Vyskocilova and Prasco, Reference Vyskocilova and Prasco2013). They have varied in terms of generalisability to UK settings the extent to which focus was purely on CBT, the duration of training of participants and clinical background of supervisees. Alfonsson et al. (Reference Alfonsson, Parling, Spännargård, Andersson and Lundgren2018) found that supervision may positively impact novice CB therapists’ competence, but only three of the five studies reviewed were with trainee therapists and they were considering different criteria (impact on client outcomes and therapist competence). They were also of specific populations (medical doctors and clinical psychology students) that might be included within CBT training but are not fully representative of the CBT trainee population at large.

Combined supervisor and supervisee views about the effective elements of CBT supervision during BABCP-accredited postgraduate CBT training do not appear to have been obtained.

Relevant supervision approaches

Existing published guidelines (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2008) for CBT supervision build upon generic models of clinical supervision and published guidance specific to CBT. Notable amongst the former is the paper of Falender et al. (Reference Falender, Erickson Cornish, Goodyear, Hatcher, Kaslow, Leventhal and Shafranske2004) outlining psychology supervision competencies. Many of these appear highly relevant to CBT supervision, such as ‘Knowledge of models, theories, modalities and research on supervision’ (p. 778). Scaife (Reference Scaife2009) has published a list of guidelines for recommended practice in supervision. Also relevant in terms of the ‘larger picture’ of supervision are Scaife’s (Reference Scaife2010) conclusions that the supervisory alliance is paramount.

CBT specific models include the ‘reflexive model’ (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997; Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), whereby CBT supervision parallels CB treatment (including agenda setting, homework review and eliciting feedback). It has been asserted that this lacks empirical support (Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2012). Milne (Reference Milne2008), whilst valuing aspects of the reflexive approach, questions whether reflexivity is sufficient, advocating for a more specialised approach, such as the tandem model, developed by Milne and James (Reference Milne and James2005).

There are several other published CBT supervision models, such as the Newcastle conceptual framework for cognitive therapy supervision (Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006). Its authors describe how it integrates three main elements: Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1984) learning cycle; the focus and characteristics of each session; and the context (‘who brings what’). Corrie and Lane (Reference Corrie and Lane2015) have more recently published a model of supervision, entitled PURE (for preparing, undertaking, refining and enhancing).

The authors are not proposing to develop a new model but rather to draw upon existing published material to compare participants’ experiences and opinions about what they perceive constitutes effective CBT supervision with existing research on CBT supervision.

Research auestions and aim

-

(1) Which elements of CBT supervision do supervisors and supervisees in a training setting consider effective?

-

(2) To what extent does this fit with existing research and expert opinion on CBT supervision?

The aim with this small study was to use thematic analysis (TA) to discover which elements of CBT supervision are considered effective by participants within training settings, and then to consider to what extent it fits with the existing research via an adapted Delphi poll.

Method

Design: overview

Ethical approval was granted by the relevant University’s ethics committee. Informed consent was gained from participants, with the assurance that participation was voluntary, they could withdraw at any time with no consequences and that all information would be anonymised.

There were two ‘strands’ to this research, which then came together, with the design intending to:

-

Gain a sense of what the literature and experts note as important in CBT supervision generally (via the adapted Delphi poll) – first strand.

-

Offer an inductive analysis of the perceptions of trainees and trainee supervisors to identify what elements they thought made CBT supervision effective (via TA) – second strand.

The two sets of data were then compared, to see whether there was consensus. As TA is helpful to cast light upon individual responses and attempt to make sense of them in context (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun, Clarke and Cooper2012), and a Delphi poll facilitates consensus amongst a group of knowledgeable clinicians (Wallis et al., Reference Wallis, Burns and Capdevila2009), the combination of these two methodologies was intended to allow synthesis. This offers a more integrated perspective between individuals and ‘experts’.

Strand 1: adapted Delphi poll

Usually there are three components of a Delphi poll (Wallis et al., Reference Wallis, Burns and Capdevila2009), but this was adapted to two, to better fit with a mixed methodology. They were: (1) constructing a list of statements, based on important aspects of supervision identified in published sources, and (2) consulting an ‘expert’ panel to offer feedback on this list.

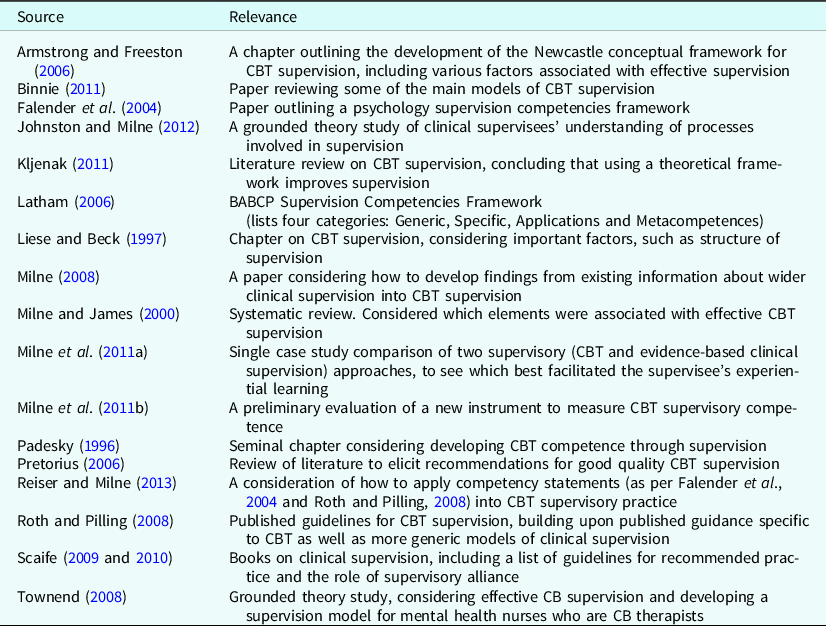

A search of the literature was carried out, using PsycINFO, CINAHL and SAGE. Other papers of interest were noted within the references of the primary sources and then checked. Searches took place over 3 months and were repeated to check for any subsequent developments. This included literature over the past 10 years, to ensure it was up to date. (More recent literature has been added to the Introduction before publication.) The initial terms searched were: Cognitive behaviour therapy, cognitive therapy OR CBT AND Clinical supervision, professional supervision, practicum supervision or supervision AND Competence .

Inclusion criteria were broad: related to CBT supervision; offering guidance about good supervisory practice or offering an overview of recognised CBT supervision practices; published in English and published within the previous 10 years. Where papers cited book chapters, these were checked and (where relevant and able to add something) included. Papers not relating to CBT supervision were excluded.

The most relevant papers suggesting elements leading to more effective supervision can be found in Table 1. Several specific CBT and relevant psychology supervision competencies and guidance were drawn from these published data, such as Falender et al. (Reference Falender, Erickson Cornish, Goodyear, Hatcher, Kaslow, Leventhal and Shafranske2004) and Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2008). The former’s work was itself based on a kind of Delphi poll of experienced clinicians and has been cited in many subsequent pieces of research on the topic of supervision, suggesting that it is viewed as a seminal paper. Its list of competency statements was thorough, drawn from an expert group and appeared relevant to CBT supervision practice. Thus, even though that paper did not focus specifically on CBT, it was the initial source of statements. The other sources were then consulted to check the relevance of particular elements, and to add to these, particularly to ensure that CBT supervision was the focus. This yielded a list of statements that appeared to be potentially important for effective supervision, such as ‘Ability to assess the learning needs and developmental level of the supervisee’ (from Falender et al., Reference Falender, Erickson Cornish, Goodyear, Hatcher, Kaslow, Leventhal and Shafranske2004; p. 778). Padesky’s (Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996) paper was included, despite being older than the inclusion criteria, as it was cited more than once and thus appeared to be a seminal paper.

Table 1. Literature consulted to obtain elements leading to effective CBT supervision (for the adapted Delphi poll)

Having gathered over 120 statements about important aspects of CBT supervision from the literature, those that expressed the same concepts were consolidated, and grouped into categories that represented similar qualities/emphases. This was discussed with the second author before consulting with the ‘expert’ panel.

The ‘expert’ panel was sought by emailing:

-

Nineteen experienced CBT supervisors (all having been CBT supervisors for between 4 and 12 years and CBT practitioners for between 5 and 15 years) – the ‘experts’.

-

Three recently graduated supervisees, (within the previous year) – to try to ensure supervisees’ perspectives were represented. In addition, the supervisors were asked to forward the request for feedback to any current or recently graduated supervisees that they thought may be able to offer feedback. The supervisors were asked to do the same with the recently qualified trainees they worked with.

-

Members of the BABCP Supervision Special Interest Group, who were all experienced supervisors (between 5 and 20 years).

No supervisees responded. In total, five colleagues and five supervisors, three of whom were part of the BABCP Special Interest Group, engaged with feedback and/or suggestions, thus making up the final panel.

The panel were consulted via email, requesting feedback on whether the elements were representative of attributes of effective CBT supervision during training. Those who responded (see under ‘Participants’) suggested clarifications and categories that could merge. Their feedback was used to finalise the list and reviewed. The first author’s supervisor and BABCP-accredited colleagues (therapists and lecturers) from the CBT training programme on which the author works also provided feedback. Several supervisors stated in person that they could not think of anything missing from the list. Ultimately, the final list consisted of 79 statements, grouped into six categories.

The 79 statements of important elements of CBT supervision were grouped into the following six categories:

-

(A) The nature of the supervisory process/relationship (including a milieu of trust, openness and respect, mutual honest feedback, self-awareness and management of different styles/problems).

-

(B) Ethical and legal factors (including managing the power imbalance, confidentiality, diversity, ethical issues and professional boundaries).

-

(C) The generic supervisory process (including aspects that might occur in any clinical modality, such as discussing individual clients, discussion of client safety, and developing integral counselling skills, such as core conditions).

-

(D) Mirroring the CBT approach (including learning specific CBT skills, supervision being structured with an agenda, and learning about and applying CBT conceptualisations).

-

(E) The supervisor’s skills/knowledge (including the supervisor being knowledgeable about CBT skills and techniques, having received supervisory training, and ability to assess learning needs of the supervisee).

-

(F) Challenge, difference and disagreement/improving practice (including working with supervisee to address deficits in practice and being able to reflect and see different perspectives).

Strand 2: thematic analysis

For the TA element, eight participants were recruited by email via purposeful random sampling (Mays and Pope, Reference Mays and Pope2000). Four supervisors and four trainee CB therapists who had graduated within the previous five months were included. They were independent of each other, rather than supervisor–supervisee pairs being interviewed. This number of participants was in keeping with the norms of TA, while acknowledging that there is little reliable guidance on the most desirable sample size. Suggestions range from six to over 400, depending on the type of data collection and size of the project (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Guest et al., Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006). Both groups were equally represented to seek parity.

While it is acknowledged that the scope of this research was modest, in a qualitative study, a small sample is not necessarily a negative factor. As Ritchie et al. (Reference Ritchie, Lewis, Elam, Ritchie and Lewis2003) suggest, one cannot assume a direct link between a larger sample size and additional evidence; the detailed information gathered in this type of approach can mean a more constrained sample size may be helpful for analysis purposes.

Basic demographic information was sought, via a brief questionnaire, to allow evaluation and critique of this research and to enable replication. This included time since qualification in CBT, previous professional orientation (such as counsellor or psychological wellbeing practitioner) and, for supervisors, amount of experience supervising CBT.

The mean total duration of clinical experience of supervisors was 18.25 years (including relevant clinical work prior to CBT training). The mean time as qualified CB therapists was 9.5 years. All supervisors were BABCP-accredited practitioners. Only one was a BABCP-accredited supervisor at the time, but all had undergone CBT supervision training.

In terms of the supervisees, mean clinical experience was 10.25 years. This was skewed by one participant who had been a social worker for 20 years previously. At the time of interviews, they had received their qualification from the university a mean of 4.25 months previously, but not yet been accredited by BABCP.

Basic demographic information is presented in Table 2 (includes all participants) and Table 3 (focuses solely on supervisors).

Table 2. Information about participants (thematic analysis)

Table 3. CBT related information about supervisor participants (thematic analysis)

For ease of access, course supervisors were consulted from the BABCP-accredited postgraduate training programme where the first author works. To eliminate any potential ethical conflict, supervisees were trainees who had recently completed the postgraduate training programme in CBT.

Semi-structured interviews with both supervisors and supervisees were undertaken to gain an in-depth picture of their views on CBT supervision. Equal significance was accorded to the perspectives of supervisors and supervisees.

Semi-structured interviews ensured that all participants had the opportunity to comment upon key basic elements – namely, what they considered to be effective and ineffective from their experiences of CBT supervision – and to be able to express their reasons for choosing the aspects they did. It was not known in advance whether participants would have equal experiences of effective and less effective supervision, or whether it might be skewed in one way or another.

Individual face-to-face interviews took place, lasting up to 60 minutes each, at the location of individual training or work sites, or via Skype (in two instances). The focus was primarily on understanding responses and, a secondary focus at this stage, potentially noting any themes or patterns that emerged. The participants were first asked to think about their overall experience (as a supervisor or supervisee during training) of CBT supervision. This was followed up with mostly open questions such as, ‘What are your reasons for giving these answers?’.

Interviews were all audio-recorded (with signed consent gained) and transcribed by the first author. All identifying details were removed and participant numbers assigned.

A six-phase approach to TA was followed (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The first author carried out the first three stages and the author’s supervisor was involved from stage 4 (see below):

-

(1) Transcribing the interviews.

-

(2) Systematically coding interesting features of the data (including condensing overlapping codes).

-

(3) Searching for themes – 12 or 13 were identified at this stage, captured on a large white board and thematic maps.

-

(4) Reviewing themes to ensure they were supported by the data. For the purpose of respondent validation (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998), the two randomly selected transcripts were kept back with the aim of coding them at this stage, to check ‘fit’ of the themes and subthemes and for independent checking by the second author. These showed a link between the participants’ statements and the themes/subthemes, as did re-reading all transcripts. Elements not sufficiently represented within the data, or not clearly distinct from other themes, did not become themes.

-

(5) Defining themes more precisely. This led to concluding upon seven themes, of which three were renamed to more fully represent what it seemed the participants were conveying. They appeared to fit within two larger groupings, and thus were reconceptualised as subthemes, fitting within two main over-arching themes.

-

(6) Writing up the research. The most important links between codes and themes were depicted on a thematic map with dotted lines to allow for clarity when writing up.

The author’s research supervisor carried out an independent audit, checking a sample of the transcripts (one of a supervisor and one of a supervisee). This enabled a shared understanding of the author’s coding before moving to formally identifying themes. The process was one of co-construction (Yardley, Reference Yardley and Smith2008), with several discussions during research supervision facilitating agreement about codes, subthemes and main themes. Another addition in terms of consistency of judgement among viewers (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998), reducing the likelihood of the author’s biases contaminating the information, was the consultation of an expert CBT supervisor to gain feedback on whether the themes made sense and inviting an alternative perspective.

Results

The thematic analysis of the interview transcripts resulted in two main themes and seven subthemes, presented in Table 4. These will be illustrated through the use of extracts (in italics) from interviews with the participants. Supervisees are referred to as S and supervisors as Sr.

Table 4. Distribution of themes and subthemes from thematic analysis

(A) Supervision as structured learning

This theme pertains to the format of supervision; how it works in a practical sense, attending to the individual learning needs and styles of supervisees, incorporating a range of methods to promote learning and mirroring CBT sessions in terms of structure.

(I) Managing student learning

All participants described the importance of supervision integrating existing skills:

‘With [supervisor] it was what I learned that it’s ok for me to be [name] and learn CBT. Because I was thinking that I have to come as a pure slate, blank slate, and that was reinforced by [another supervisor] saying you have experience; you’re not coming blank; you’re not coming new’ (S1, 10–12).

Equally important (and also mentioned by all eight respondents, was addressing gaps in knowledge and skills (teaching): ‘… if I can have those mini lectures or feel okay with sticking my paw in the air and saying, “Do you know what, I know we’ve only just had a lecture on this but… I still feel that I don’t get it”’ (S2, 256–258).

Making links between theory and practice was cited by over half of the participants: ‘Because I think when I see it working best is … we’re helping to kind of, um, unpick some of the theory sometimes and put it into practice … what’s the theory behind this, how does that get applied to practice…” (Sr2, 83–87).

All commented on the idea of supervisees’ learning needs changing throughout training. It was considered important for supervision to be tailored to accommodate these: ‘… you need different things at different times, even just within a year’ (S2, 105–106). This included addressing the variety of experience within a group: ‘… I think it’s really important to actually be able to notice the different levels… um … that the students are at … in group supervision’ (Sr3, 130–131).

Each participant, bar one, referred to how participant beliefs need to be identified and managed, including those of supervisees: ‘And I put pressure on myself saying, “Oh no, no, no, no, I have to get this right and if I don’t get this right…” my core belief of not being good enough was flagged up again and again…’ (S1, 35–37) and of supervisors: ‘… I sometimes get a feeling in my own head that perhaps she’d be thinking, you know, “He’s a chancer” [laugh]’ (Sr4: 126–127).

One other important factor in this subtheme was the process of shared learning and validation from the group. All interviewees spoke about this: ‘… sometimes group could be useful cos you are getting insight into… it can be several heads are better than one’ (S2, 234–235) and: ‘I think there’s something more powerful … coming from a peer than coming from a supervisor sometimes’ (Sr3, 488–489).

(II) Structure of supervision mirrors CBT session

All of the participants noted how the most effective CBT supervision sessions were those that mirrored CBT treatment sessions, and spoke about this a number of times in their interviews: ‘… but also for me the most successful supervision, or the most useful supervision was supervision that modelled CBT … I remember myself sitting there and just seeing one particular person and actually thinking, “Aw that’s good”’ (S2, 39–41).

Other important elements of CBT treatment were posited as important. These included being prepared/having ideas about what you wish to gain from a session, linked with an existing model of CBT supervision (Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996): ‘… in terms of like Christine Padesky’s kind of supervision road map and that kind of stuff, they usually haven’t done that … um, I think it would be better for their learning if they had, you know, cos they would’ve kind of worked through and identified the nub of the issue themselves and they’d probably feel a bit more empowered …” (Sr1, 376–379).

(III) Use of variety of methods within supervision

The third subtheme focused on the importance of including a combination of case discussion, audio clips and role play within supervision, in order to derive the most learning: ‘So if you’re recalling a session with somebody, you’ve got high insight bias … you’ve got your rose tinted spectacles on … you might miss something out. But the brutal honesty of a tape … you can’t hide anything … and actually that’s really good … that meant that I’d get better feedback, and better guidance’ (S3, 159–163) and: ‘… it’s around mixing up the strategies and not just sitting there and talking and doing one to one … You know, having tape, having role play, doing mini things on the board, drawing stuff up, you know, er, formulating with them in the session…’ (Sr2, 101–103).

(B) Supervisory relationship and process

This theme pertains to the supervisory relationship, including aspects of the supervisor’s characteristics, professional and ethical issues and how conflict/challenge is addressed.

(IV) Supervisory alliance: the role of the relationship

All participants referred to the importance of supervision being a safe space, in order for them to be able to express vulnerability: ‘… one of the supervisors had a really lovely interpersonal warm style, um which [pause] I think just helped me to feel very comfortable and felt … and so I felt if I could trust him then I could of sort of talk about maybe things that [I] wasn’t quite so happy about in … my practice’ (S4, 19–21).

Linked with this was the role of supervision to normalise anxiety: ‘… it was through supervision … that I made some sense and I was fine to understand that I am sane and I have to go through this deskilling to reskilling’ (S1, 6–8).

Part of the process of establishing a trusting alliance included the supervisor being honest about areas where he/she did not know: ‘… it is about being able to say, “You know what? I don’t have an answer to this” … and it was a permission for me to say, “Oh, I don’t know as well. And it’s ok not to know, it’s ok not to be competent in everything but to work towards”.’ (S1, 146–154).

As with a therapeutic alliance, the ‘fit’ between participants, linked closely with effective communication, was highlighted by over half of the respondents: ‘… most of the time you can rub along and … and get the job done. If you’re incredibly lucky, you’ll get somebody that you speak the same language … and you will be able to communicate as a supervisee what you need, clearly, to the supervisor…’ (S4, 476–478). Similarly important was the supervisor conveying that they are present through active listening and responding to what the supervisee brings: ‘… it’s just … actually listening to what it is they’re saying, rather than going in there and, you know, like we might do with clients, tell them … more stuff than they’re ready to hear…’ (Sr4, 518–519).

(V) Managing challenge and conflict within supervision

All but one of the participants spoke about how discomfort and challenge can lead to learning and development: ‘These past twelve months have rubbed me the wrong side. Which I … honestly needed’ (S1, 222) and: ‘And the most learning is going to take place from things that you would struggle with’ (Sr3, 405).

Six participants referred to the importance of managing difficulties or challenges within the supervision process, particularly within groups: ‘I think that supervisee that was a bit combative … um the other supervisees, perhaps trying to defend me, I felt … jumped on her from time to time, um, so it’s kind of weird … cos I thought they were actually kind of trying to rescue me cos they perceived she was doing something she shouldn’t have been doing, but I was having to stop them from [laughs]…’ (Sr1, 294–297).

(VI) Supervisor’s characteristics, including knowledge and passion

This was an interesting area, in that it was important to the supervisees – all of them referred to at least one of the three codes linked with this subtheme and two referred to three of them – but only two supervisors highlighted it. However, it was included as it appeared important and seemed to particularly link with creating a helpful environment for supervision. The key factors in this subtheme included the supervisor being knowledgeable: ‘… you need to trust their skills and trust their knowledge in CBT cos they’re passing that on to you … And for me that was quite important to know that what I was learning from them fits with the models and is evidence based and that sort of thing. So I think that was really important in building a relationship – with me anyway’ (S3, 217–221).

Another highlighted element was the supervisor’s enthusiasm for the CBT modality as well as for being a supervisor: ‘Basically as a supervisor what I look for personally is, do you believe in what you’re selling me?’ (S1, 40–41) and: ‘… just as somebody feeling passionate about CBT and delivering it … and somebody feeling passionate about nurturing tender little students, you know? And sort of bringing the best out of them, rather than maybe just sitting back and watching them sort of floundering.’ (S4, 500–502).

(VII) Ethical practice

This referred to participants (supervisors and supervisees) conducting themselves professionally within supervision. It was linked by several respondents to the supervisor’s ‘gatekeeping’ role, and five respondents spoke about it. One supervisor stated: ‘… you know, she would be rummaging in her handbag to find the bits of paper she’d written on, and I’d be saying, “Well … should you be carrying bits of paper?” There wasn’t much client detail … it culminated in the mid-point … you fill in for BABCP [clinical portfolio] and … the question was around, “Would you see this person as being credible?” and stuff, and then – of course, she wasn’t.’ (Sr4, 224–236).

Boundaries, including confidentiality within the group, also came under this subtheme: ‘I’d … feel the alliance between the supervisees would be really important to me, because you want to … feel confident and comfortable with the people … you’re laying yourself bare … And you want to feel that those people are being professional about it and not going to go away and go, “… [supervisee]’s done this, that and the other on the tape”.’ (S3, 203–207).

In addition, the process of ethically managing the power imbalance inherent in supervision was highlighted: ‘… I think it really helps to … to change that dynamic of feeling as though it’s one or the other, you know – a power relationship?’ (Sr2, 125–126) and: ‘And that is when I really saw who [supervisor] is … he did a small thing in that supervision: he used his library card and went and got some photocopies. And for me that’s very touching where he put his authority aside and he chose to engage on a [human level] … with us … and it was really, really good.’ (S1, 100–102).

There was agreement from all participants about both themes being important.

Results: comparison of thematic analysis and adapted Delphi poll (bringing together the two ‘strands’)

The six Delphi categories were considered one at a time, comparing constituent parts against TA codes. As noted with the approach employed for TA, a co-construction process (Yardley, Reference Yardley and Smith2008) was used to reach a negotiated settlement and see whether both authors were in agreement: the first author initially considered whether the TA codes and Delphi categories suggested similar themes; then the information was reviewed by the second author, followed by discussions about similarities or differences.

Some categories linked with more than one TA subtheme. For example, Delphi category A was about the supervisory process. It contained nine separate elements. Elements 1 (ability to address personal problems if interfering with therapy or supervision) and 4 (reflection and self-awareness) were in line with TA subtheme I (managing student learning). The remaining seven elements from Delphi category A fit with TA subthemes IV (supervisory alliance) and V (managing conflict within supervision). This meant there was a 78% match between Delphi category A and TA theme B (and a 22% match between the same Delphi category and TA theme A).

Most of the elements listed in the adapted Delphi poll were referred to within the TA codes/subthemes. The themes that came together from the coding process during TA were similar to the Delphi categories. To illustrate some links between Delphi categories and TA themes:

-

Delphi category D: Mirroring the CBT approach was a close match with TA theme A: Supervision as structured learning (relevant to all three subthemes)

-

Delphi category C: The generic supervisory process, whilst titled differently within the TA subthemes, contained individual elements that each matched well with codes fitting within theme A.

One distinct element identified from the TA did not appear to be present within the literature and thus did not seem to be linked with the adapted Delphi poll. This was ‘passion’ on the part of the supervisor – both for CBT as a modality, and for being a supervisor. This therefore appears to be distinct to the TA.

Two areas from the literature were not referred to within the interviews: discussion of therapist safety and acceptance of diversity. The first, while not explicitly raised, may have been implicit under one of the codes related to supervisees identifying needs and developing skills, as well as supervision being ‘a safe base’. It may also relate to them feeling contained in their roles as trainees, whereas the literature was referring primarily to qualified therapists. The second area, diversity, suggests that perhaps more consideration could have been given to demographic factors at recruitment. Participants were not asked about their ethnic background or other aspects related to diversity and, again, perhaps this would have been relevant. One participant did explicitly refer to being non-white, although as part of an analogy to illustrate differences in approach with a co-supervisee:

‘And [fellow supervisee] and I are very, very different in our ways. Mine is a very, very existential way of doing things. And … he’s very structured and yet very holding… And we are both … I’m brown, he is white, and honestly, that’s the difference in the practice we both practise.’ (S1, 436–442.)

This participant frequently used analogies in the interview, so this did not stand out as different in this context. The participant was also invited several times to raise any other relevant issues. However, it might have been valuable to ask specifically about whether diversity issues were pertinent.

Overall, it appears that the results of the thematic analysis are broadly in accordance with those from the adapted Delphi poll.

Discussion

The research questions of the project were:

-

(1) Which elements of CBT supervision are considered effective in a training setting?

-

(2) Does this differ from the existing research on CBT supervision?

Question 1 relates to the findings of the thematic analysis, and question 2 relates to the comparison of the results from the TA with the information captured by the adapted Delphi poll. This discussion lends itself to an integrated approach, so they will both be addressed together.

The results of the thematic analysis suggest that themes (A) Supervision as structured learning and (B) Supervisory relations and process are key elements of CBT supervision that, when present, facilitate effective CBT supervision during training.

Theme A consists of factors that enable a supervisee-in-training to learn and develop knowledge and skills relevant to CBT practice. This requires assessment of their existing strengths and learning needs and tailoring the supervision to these idiosyncratic areas. In practice, this may occur through teaching, role-play, feedback in response to role-play or recordings, reflective exploration or gaining alternative perspectives via case discussion. Taken together, these aspects were characterised as the supervisory session resembling the structure of a CBT session (or mirroring it). This was linked with effective learning, in accordance with existing literature, including Padesky (Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), Johnston and Milne (Reference Johnston and Milne2012), and Reiser and Milne (Reference Reiser and Milne2013). The latter in particular describe how this mirroring process can help manage supervisees’ anxiety.

Theme B relates to the supervisory relationship: how it is established as a safe, trusting, supportive space; the supervisor’s knowledge, preparation and passion for the modality and as a supervisor; modelling and management of ethical and professional practice and facilitative management of challenge/conflict within supervision. This is in keeping with existing recommendations on CBT supervision (e.g. Beinart, Reference Beinart, Fleming and Steen2004; Bernard and Goodyear, Reference Bernard and Goodyear2014; Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015; Falender and Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2004; Johnston and Milne, Reference Johnston and Milne2012.) Corrie and Lane (Reference Corrie and Lane2015) highlight the importance of the collaborative alliance, and comment that the recent trend towards focusing on outcomes and competence could mean process-related elements (including the alliance) could be overlooked. This is pertinent, given that the findings of this small study seem to link the alliance with structure (which may be within the realms of ‘competence’).

Both themes are well supported by the subthemes, which are in turn underpinned by several codes that the majority (sometimes all) of the interviewees cited.

With regard to theme A, Johnston and Milne’s (Reference Johnston and Milne2012) grounded theory study of clinical supervision suggests that the developmental needs of a supervisee are important and refers to scaffolding as a construct that facilitates tailoring supervision. The others are Socratic dialogue, reflection and the supervisory alliance, the latter of which relates to theme B. In the absence of a good alliance, interviewed supervisees were less likely to be open about areas of vulnerability.

Milne (Reference Milne2009) identifies a lack of empirical evidence supporting the supervisory alliance in terms of effectiveness. This is not to say that alliance is unimportant but might suggest caution against accepting that it constitutes effective supervision on its own. One might surmise that alliance was valued by participants as it could provide a more enjoyable, or comfortable, experience. However, the participants in this study also spoke about the need for experiencing discomfort to achieve learning. This is in line with other published research about discomfort positively influencing learning, such as Kruger and Dunning (Reference Kruger and Dunning1999). They suggest that people’s confidence drops, and discomfort increases, as they begin to learn more about a topic that they are not expert in, followed by an increase in confidence, coupled with competence, as learning progresses. Similarly, Mezirow’s theory (Mezirow, Reference Mezirow1990) about transformative learning posits that realising what one does not know (and the associated feeling of discomfort) can act as a catalyst for learning and change. It is notable that the supervisees in this study identified that they would not feel able to expose their vulnerability if they did not feel supported within a strong supervisory alliance. This may suggest that a degree of safety within the supervisory alliance may be a necessary underpinning for trainees to be able to embrace the challenge and discomfort inherent in learning/development – and that the latter is also important for optimal supervision.

The adapted Delphi poll listed a number of factors that are considered by experts in CBT supervision to make it effective. The categories and individual elements are not ranked in order of importance, and it is therefore not possible to conclude which aspects, if any, are more or less vital. One can only take them as suggestions of effective elements of CBT supervision. Most categories are well represented within the TA themes and subthemes. Thus, the suggestion is that the findings of the thematic analysis broadly accord with the existing research.

Where there are differences between the Delphi poll and the results of the TA, such as the title of category C (the generic supervisory process), this might suggest that the grouping of those elements could have been carried out differently, or that the TA process could have led to different themes being identified. Alternatively, it could relate to the decision to include literature that was not specific to CBT (generic supervision), such as that by Falender et al. (Reference Falender, Erickson Cornish, Goodyear, Hatcher, Kaslow, Leventhal and Shafranske2004). There was a clear rationale for doing so, and with the dearth of CBT-specific guidance, it seemed appropriate, but it would be interesting to repeat the Delphi poll with literature solely focused on CBT supervision and then repeat the comparison. This will require waiting until the body of literature specific to this subject has developed further.

The last category within the adapted Delphi poll, ‘Challenge, difference and disagreement: improving practice’ contains three statements, which is considerably fewer than the other categories have (see Table 5.) When comparing these with the codes from the TA, at least one of them may not be best placed there – 77. ‘Supervisor helps supervisee identify deficits in practice and address these (through role-play, discussion, audio, goal setting, etc.)’ – or it might be worded differently, emphasising how the supervisor responds to problems. In either case, this category does not seem comparatively substantial; suggesting further consideration of categories in future could be useful.

Table 5. Comparison between categories from the adapted Delphi poll and the TA themes that best fit with them

In Table 5, codes grouped within theme B (supervisory relations and process) seem to be somewhat more represented within the categories of the adapted Delphi poll, than those within theme A (supervision as structured learning). It may be related to the results of each approach having been drawn into groups using different methodologies. However, with the exception of ‘passion’, the same key elements of what makes CBT supervision for trainees effective are represented in the results of the adapted Delphi poll and the TA.

Agreement was found between the TA and adapted Delphi poll, as described above. Although this was a small sample, one might tentatively suggest that the group of CBT supervisors and supervisees appeared to understand the aspects important to CBT supervision. The supervisors had between 4 and 12 years of experience in that role and had all received supervisory training, so one might expect them to be familiar with theory about supervision. Watkins (Reference Watkins2012) posits that information about the best way to prepare clinicians to be competent supervisors is still emerging, and thus any conclusions about what is most effective in this regard can only be tentative. A practitioner’s understanding about supervision could develop from a range of sources, including training (which could consist of short workshops or longer training programmes) and reading relevant papers and resources. Information about prior experience of delivering supervision was not sought from supervisees; it would have been interesting to find out more about their level of understanding about the theory and practice of supervision. What is known about this group is that, at a minimum, they received a lecture early during their CBT training about CBT supervision, including relevant theory, as well as one year receiving CBT supervision at the BABCP recommended level. Their understanding about what constitutes effective CBT supervision is reassuring; it may suggest tutors and supervisors at the author’s institution teach and model central elements of CBT supervision. It is not possible to determine how far the supervisees’ understanding came from knowledge of theory and how much came from modelling during supervision and experiencing what is helpful for themselves. This could be important, as experience alone may not confer competence (Watkins, Reference Watkins1997).

Strengths and limitations

This is a small-scale study, with an exploratory approach. Its focus is on a novel area of research, and it can add to the emerging evidence about CBT supervision during training. As the participants were affiliated with one specific training provider, it is possible that the findings may not be representative of a wider UK perspective.

The research methods employed were well-suited to this study, blending flexibility in considering themes from newly gathered information with already existing knowledge and ideas.

There was a lack of diversity within the TA participant group, limiting the generalisability of the findings. The first author contacted many more than eight people, from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, as well as a range of ages and gender, but only eight responded. By virtue of teaching on the programme, the graduates knew the first author and this might have affected their responses, although all had completed their training and thus were not affected by the potential for any marking or supervisory bias. The sampling confound is acknowledged.

While this study does not claim to identify elements that increase effective supervision during CBT training – instead focusing on participants’ opinions on the matter – there is no clear way of identifying whether the supervision being described was actually effective, beyond the trainees each successfully completing their training. Considering client outcomes might be an approach to identify effective supervision, although Scaife (Reference Scaife2010) highlights the difficulty of this. Researchers such as Milne (Reference Milne2016), and Reiser and Milne (Reference Reiser and Milne2013), have been working to develop valid and recognised competency frameworks, which might facilitate a tangible perspective on how effective the identified elements might be.

Despite intending that the TA approach was inductive, it could be argued that it was in fact deductive, given that the adapted Delphi poll had been conducted first. One might posit that this could lead to bias. On the other hand, with an awareness that the majority of existing research was not carried out within training settings, it seemed plausible before the interviews that they would be different in content and/or focus to the information in the Delphi poll. Thus, the interviews and transcripts were consciously approached with curiosity and an open mind, allowing the interviewees’ perspectives to be captured. Notes in the first author’s reflective log, kept throughout, comment on a sense of genuinely not knowing what would come up as important elements during interviews, which was why an open question, rather than a more specific hypothesis, was the foundation of this work. Although perhaps one preconception was that there would be elements that influence how effective supervision is, their specific nature was unknown. Boyatzis (Reference Boyatzis1998) suggests that there are several means of increasing reliability, including ‘consistency among viewers’. This was sought by the supervisor looking at a sample of transcripts and the codes, leading to a two-way discussion.

Clinical implications

Conclusions cannot be reached about the implications of this study on client work. However, in terms of CBT supervision, particularly with trainees, it might tentatively be suggested that a supervisor might wish to employ structure within supervision (along the lines of what occurs during CBT). For example, by commencing a supervision session with a mutually agreed agenda and emphasising two-way feedback throughout, including mini summaries during, and major summaries at the beginning and end of supervision (as per recommendations for competent CBT by Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001). As one trainee expressed, observing a supervisor model CBT approaches (including structure) can be experienced as particularly valuable.

In addition, one could posit that a supervisor might focus on promoting a strong supervisory alliance. The supervisee will also play a role in this process and so discussing the relationship overtly could be helpful. All but one of the participants suggested that challenge/discomfort was helpful towards their learning. However, it was also noted that this first requires people to feel safe within a trusting and supportive relationship. Practically speaking, active listening and demonstrating warmth were two elements explicitly identified as beneficial and therefore could be helpful to emphasise. Lastly, supervisors could consider how they might tailor the supervision to each supervisee’s stage of learning to maximise the chance of it being a beneficial experience. It is suggested that this process, alongside all elements, be collaborative – another principle of competent CBT (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001).

Implications for future research

Following up this research with a larger sample size and more heterogeneous group of participants could be valuable. This would allow exploration of the extent to which these factors are significant to supervisors and supervisees in terms of CBT supervision during training. It could also be interesting to conduct a comparison of supervisors’ and supervisees’ views, to see how far they concur. Finally, repeating this study with a larger, more diverse sample size might allow for some generalisability of findings. Having an interviewer unknown to participants could further reduce the chance of responses being influenced by a pre-existing relationship.

Conclusions

This study suggests that structure within CBT supervision, mirroring that of a CBT session (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997; Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), alongside a safe, supportive supervisory alliance (Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015), is considered by participants to lead to effective supervision. The focus has been in the context of postgraduate CBT training.

Both the thematic analysis and expert feedback on the literature suggest that the structure of supervision mirroring CBT sessions and the therapeutic alliance are both important; if either was missing within the supervision, the participants would not have considered it effective. Other important variables included tailoring supervision to idiosyncratic learning needs and discomfort leading to learning – although the latter was described as being possible only within the security of a trusting supervisory relationship.

An interesting feature of the thematic analysis is that supervisees seem to value passion in their supervisors – both for CBT as a modality, and for being a supervisor.

Key practice points

-

1. CBT supervisors should assess trainees’ existing strengths and learning needs and tailor the supervision accordingly, perhaps via more teaching in earlier stages moving towards more reflective exploration as they gain experience. A poor fit with individual learning stage can be experienced by trainees as unhelpful and ineffectual towards learning.

-

2. Including a variety of methods is valuable to both supervisors and supervisees within supervision, such as role-play, feedback in response to role-play or clips of sessions, and case discussion.

-

3. Supervisees during CBT training value having a supervisor who demonstrates that they are prepared, knowledgeable and, for some, passionate about CBT.

-

4. All participants consider that trainees being prepared for supervision, arriving on time and engaging fully are essential. This could be appropriate to establish at the contracting stage and review regularly.

-

5. Without a safe, trusting environment, it is less likely that supervisees will feel able to expose areas of vulnerability; this is where there can be opportunities for learning and development, including via identifying trainees’ own beliefs as they relate to their clinical practice. Skill and knowledge about structure and likelihood of self-practice could be limited or even prevented without a trusting alliance to support them. This suggests the need to allow time for process aspects of supervision to be established and managed with supervision sessions.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted by the first author under the supervision of the second author in part fulfilment of the MSc in Psychological Therapies: CBT. We extend grateful thanks to members of the BABCP Supervision Special Interest Group and CBT supervisors for their feedback on the adapted Delphi poll. We would like to extend our appreciation to the students and supervisors who offered their insights during the interviews. Thanks also to Derek Milne for early encouragement with this study.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was granted by Canterbury Christ Church University’s Ethics Committee (Salomons Institute) (no reference number; dated 25/03/14).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, N.K. The data are not publicly available as, overall, they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, N.K. and A.H.; data curation, N.K.; formal analysis, N.K. and A.H.; investigation, N.K., methodology, N.K. and A.H..; project administration, N.K.; resources, N.K.; supervision A.H.; validation, A.H. and N.K.; writing—original draft, N.K. and A.H.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.