Introduction

Social connectedness is frequently tendered as the key to enabling older people to age ‘successfully’ and ‘in place’, as well as forming the backbone of ‘age-friendly societies’ (World Health Organization, 2007, 2015). Social connection has been associated with decreased rates of depression (Cruwys et al., Reference Cruwys, Dingle, Haslam, Haslam, Jetten and Morton2013), decreased risks of cognitive decline (Ertel, Reference Ertel, Glymour and Berkman2008) and mortality (Seeman et al., Reference Seeman, Kaplan, Knudsen, Cohen and Guralnik1987), and greater longevity (Umberson and Montez, Reference Umberson and Montez2010). Social connectedness is heralded as a positive alternative to the deficits model associated with loneliness and social isolation by re-centring older people's agency and resourcefulness to adapt to social circumstances and remain socially active in later life (Cornwell et al., Reference Cornwell, Laumann and Schumm2008; Register and Scharer, Reference Register and Scharer2010).

In this way, the social connectedness approach pushes against ageist assumptions, which are often internalised by older people themselves, that later life necessarily involves diminished social contact and increased levels of social isolation and loneliness (Cornwell et al., Reference Cornwell, Laumann and Schumm2008; Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Hank and Künemund2009). It does so by moving beyond individual psychological or physical characteristics to consider the nature of older people's wider social networks (Cornwell et al., Reference Cornwell, Laumann and Schumm2008; Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Allen, Palmer, Hayman, Keeling and Kerse2009; Yen, Reference Yen, Shim, Martinez and Baker2012) and engagement in the ‘social world in toto’ (Bellingham, Reference Bellingham, Cohen, Jones and Spaniol1989; Lee, Reference Lee, Draper and Lee2001; Register and Scharer, Reference Register and Scharer2010).

When operationalised social connectedness often suffers from definitional ambiguity, standing in for concepts such as collective self-esteem, social engagement, belongingness (Register and Herman, Reference Register and Herman2010), and social integration or social support (Cohen, Reference Cohen2004). For the purposes of this review, social connectedness is considered ‘an opposite of loneliness, a subjective evaluation of the extent to which one has meaningful, close, and constructive relationships with others (i.e., individuals, groups, and society)’ (O'Rourke and Sidani, Reference O'Rourke and Sidani2017).

Scholars have begun to highlight the way social connection is experienced differently across genders and cultures (Townsend and McWhirter, Reference Townsend and McWhirter2005). For example, a recent systematic review highlighted the way that cultural differences play a role in shaping older people's needs (Bruggencate et al., Reference Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018). The degree to which Asian adult children provide social support for their parents in contrast to their Western peers is a commonly cited cultural variant (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hicks and While2014), although recent research has begun to emphasise the independence of older Asians from their families, especially in contexts of migration (Shin, Reference Shin2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Morgan, Wiles and Gott2019). Other work highlights the importance of structural factors, such as access to public transport (Emlet and Moceri, Reference Emlet and Moceri2012; Gardner, Reference Gardner2014), access to financial resources (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Abolfathi Momtaz and Hamid2013) or features of the built and natural environment, which have the potential to support or create barriers to social connectedness (Scharf and de Jong Gierveld, Reference Scharf and de Jong Gierveld2008; Rantakokko et al., Reference Rantakokko, Iwarsson, Vahaluoto, Portegijs, Viljanen and Rantanen2014).

Scholars have also argued for the greater emphasis on the structural context in which older people attempt to make connections. The impact of poverty, inequality and exclusion, particularly on older individuals from minoritised backgrounds, has recently received attention in research and policy (Umberson and Montez, Reference Umberson and Montez2010; Weldrick and Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018). Nonetheless, interventions for promoting social connectedness continue to be focused on individual-level related factors such as increasing one-to-one personal contact and promoting group activities and objective measures of social isolation (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; O'Rourke and Sidani, Reference O'Rourke and Sidani2017). This means the the social and cultural nature of social isolation tends to be overlooked, as are the processes and structural factors that produce isolation and loneliness (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017; Weldrick and Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018).

In this research we worked with a diverse sample of older people living in Aotearoa, New Zealand to explore what they saw as the enablers and barriers to being socially connected in their everyday lives. We understand this project as offering a new lens to help contribute to the burgeoning field of research about older peoples’ experiences of loneliness and social isolation, including in the increasingly multi-cultural New Zealand setting (Jamieson et al., Reference Jamieson, Gibson, Abey-Nesbit, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Keeling and Schluter2017; Wright-St Clair and Nayar, Reference Wright-St Clair and Nayar2017).

The aims of our research were to establish:

(1) What do older people see as protective factors that enable or foster their social connectedness?

(2) What factors do older people identify as preventing or operating as barriers to their social connectedness?

Study design

This paper reports on individual and group interviews from the initial qualitative phase of a two-phase mixed-methods study on maintaining social connectedness in older age in New Zealand. The overall project centred on maintaining social connectedness in older age in an New Zealand context, and was conducted in partnership with Age Concern NZ, a well-established older people's advocacy organisation. We approached social connectedness from a social constructionist theoretical framework, inspired by the approach of Victor et al. (Reference Victor, Scambler and Bond2008) to studying social isolation and loneliness as existing ‘in the context of a mental framework or construct for thinking about it’ rather than as objective truths scientists can access unmediated (Crotty, Reference Crotty1998).

Recruitment: participants and settings

Semi-structured interviews with older adults were conducted in three sites across New Zealand, purposively selected to enhance the possibility for inclusion of people who are often left out of research, and specifically to reflect New Zealand's cultural diversity (we aimed for at least ten interviews from each of four broad cultural groups: Māori, Pacific, NZ European (NZE) and Asian). Inclusion criteria for participation included being a self-defined older person, self-identifying as wanting more company, and cognitively able to agree to and participate in an extended face-to-face interview. We translated all material into Mandarin and Korean to ensure successful recruitment. Ethics approval was gained from the University of Auckland's Human Participants Ethics Committee and additional health board-specific ethics approval was attained for recruitment of participants via Older People's Needs Assessment and Service Co-ordination (NASC) teams at two hospitals.

We employed a horizontal sampling strategy, which incorporates a mixture of strong and weak ties as ‘bridges’ into new social networks, thus allowing a number of entry-points to our population (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Parker and Scott2018). This was important because our population was both ethnically and culturally diverse (ruling out a one-size-fits-all recruitment strategy) and likely to be hard to reach given some participants’ social isolation. We recruited half of our sample through support of managers at three Age Concern centres who helped us to identify and contact people who are enrolled in the Accredited Friendly Visitor service, a befriending service which consists of a weekly volunteer visit to an older person who has expressed a desire for more company. The other half of our sample was recruited through organisers’ culturally specific community organisations such as the Chinese Positive Ageing Trust and Treasuring Older Adults Pacific, as well as two hospital-based NASC teams. All potential participants were offered a printed participant information sheet and letter of invitation by the person who recruited them. If they agreed they were interested in taking part in the study, a member of the research team called them to discuss the study further and to arrange a time and place to meet if they agreed to take part. Participants were offered the option of having a support person with them. Although our initial research design focused on one-on-one interviews, in several cases participants requested group discussions instead; in context, we interpreted these requests as being in line with cultural preferences around discussing sensitive topics and respected their preferences.

Data collection

All participants provided written consent to participate, with the exception of one group discussion where verbal consent was recorded due to the size of the group (N = 22; this took place in response to the audience's enthusiasm following a presentation to an Age Concern coffee group by the researcher, where participants had the opportunity to opt in to participate following the close of the coffee morning, after a group discussion about informed consent. We followed culturally appropriate protocols whereby our interviewers and interviewees were matched by ethnicity and language; eight researchers were involved in conducting the interviews. We used cultural customs of hospitality and reciprocity, including offering a koha (Māori word for donation or reciprocal gift) to all participants and kai (Māori word for food) to our Māori participants.

An interview guide was developed for the individual interviews. We began by asking what our participants saw as important to them and we then had a discussion to identify and describe their social connections. Where desired by participants, this involved co-producing a map using paper and pens about which people they had the most contact with and who felt the closest to them (denoted by their placement in relation to the participant who was in the centre of the sheet). Further questions explored experiences of loneliness and barriers and facilitators to social connectedness. The group interview guide was adapted from the interview guide to facilitate group discussion, exploring what participants perceive helped and hindered social connection but not including the personalised mapping of social connections.

Interviews took place in 2016. Of the 44 individual interviews, 40 participants chose to be interviewed at home, two in a café selected by the participant and two in the office of a community organisation. Ten participants had a support person with them who was either a family member (N = 5, four of whom were Pacific) or their visitor from Age Concern (N = 5). Each participant was interviewed once and interviews ranged from 16 to 93 minutes; most averaged one hour. The group discussions were held in community venues operated by Age Concern and the Chinese Positive Ageing Trust. The Korean group was held at the house of one of the participants. Group interviews lasted between one and one-and-a-half hours.

Preceding the interview, most participants received at least two phone calls to discuss the research and build rapport and a level of trust with the interviewer; further relationship building occurred in person prior to the actual interview, particularly for the Māori, Pacific and Asian participants. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Korean data were collected and translated by the same researcher, whereas Chinese data were collected and transcribed by two separate researchers.

Data analysis

We conducted both a thematic and narrative analysis of our participants’ talk in order to make comparisons across groups as well as examining how our participants constructed themselves and their circumstances to the interviewer and in relation to peers in the case of the group discussions (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Rosenberg and Kearns2005; Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The whole team together read transcripts to identify both latent and descriptive themes (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), looking for both similarities and differences across the transcripts as well as the coherence and context within each transcript (Maxwell and Chmiel, Reference Maxwell, Chmiel and Flick2014) and using NVivo 11 to support data analysis. The lead author (TM) worked with the lead researcher of each culturally specific data-set to code each transcript. To ensure the robustness and cultural-safety of our analysis, where researchers’ interpretations differed, the researcher leading the data-set was given priority. Data segments were then further reviewed by two researchers to produce the final themes. We also looked at the overall narrative of the interviews as well as particular stories told by participants, to understand cultural interpretations of connectedness. Interview participants are identified by their ethnicity (E: NZE, M: Māori, P: Pacific, A: Asian, O: Other), then gender (M: male, F: female) and the number within their group. Group interview participants are also identified by their ethnicity and gender as well as their group (KG: Korean group, CG: Chinese group, MxG: mixed ethnicity group).

Results

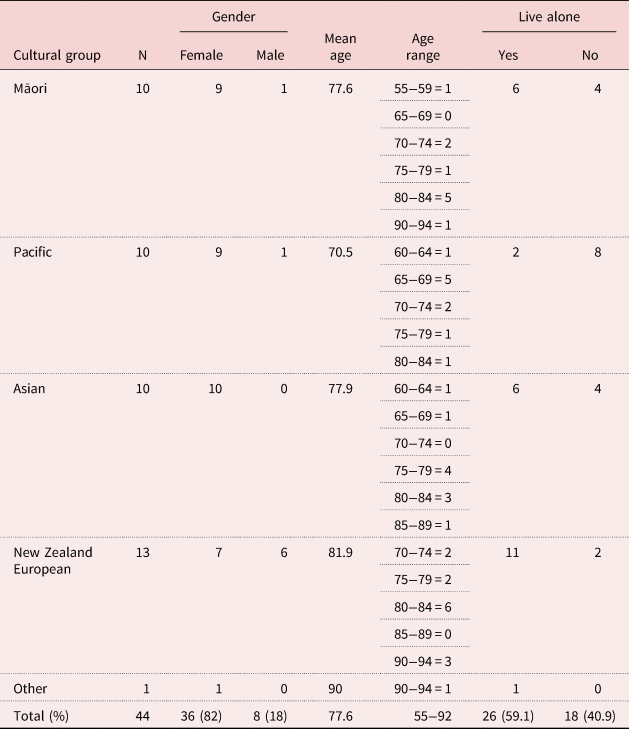

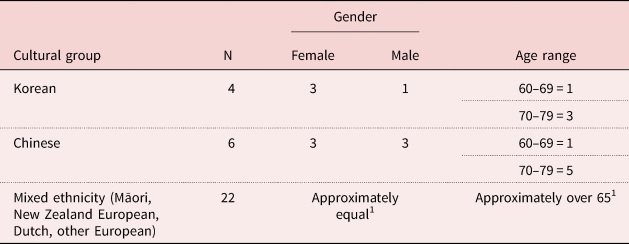

In total, 44 participants took part in individual in-depth interviews and 32 older adults took part across three group discussions (Tables 1 and 2). In-depth interview participants reported varying degrees of social contact and living arrangements. The majority of our sample were widowed or divorced and only six participants lived with their spouse (in two cases they were also living with their children). Twenty-six participants lived on their own, seven lived with their adult child, two with their grandchildren and two with borders (out of financial necessity). Almost half of participants in individual interviews said that they had the most social contact with one of their adult children (N = 18), in seven cases their son. A further six participants struggled to name a specific person with whom they had regular contact; one participant said she only had regular contact with nurses and one participant said she had regular contact with no one. Pacific participants tended to refer to their whole family as their contact rather than single out a family member. Pacific participants were also far more likely to live with another family member (eight of ten compared to two of 13 European participants) and have a family member present at the interview (four of ten). In our analysis we identify three themes about what enabled or prevented social connectedness: (a) getting out of the house, (b) the ability to connect, and (c) feelings of burden.

Table 1. Characteristics of individual interview participants

Table 2. Characteristics of group interview participants

Note: 1. Due to the size of the group, specific individual-level data were not collected for each member of the group. What is indicated above is the retrospective impression from the researcher who conducted the group interview.

Getting out of the house

Participants framed their feelings of social connectedness within wider contexts which either enabled or limited their physical ability to get to social situations and/or have the capacity to make meaningful connections. All participants discussed health decline, which they perceived as age-related, as both directly and indirectly impacting their ability to connect. Above all, decreased mobility that impacted participants’ ability to get out of the house or to drive was seen as a substantial restriction to being socially connected. This was apparent in one NZE man's vivid description of the exhausting and difficult work getting out of the house means for him:

…crawling into the car, getting in and out of the car … with my restricted ability to move around. Going to the garage and getting the car out, shutting the garage … then at the other end, getting out of the car again. I've then got to find parking and then walk a distance to go [where] I'm going to. To me, it was easy when I was a bit more mobile, but it's very restrictive now. And consequently [it has reduced] my interests in going out anywhere, reducing my ability [and] my willingness to do anything ’cos it was such a rigmarole. (EM09)

Many participants who wanted to travel independently shared the difficulties they experienced with public transport, which was described as deeply unreliable with buses rarely running to schedule. Some participants felt they could not rely on bus drivers to help them get on and off the bus, which meant they often stayed home rather than risk embarrassment. Chinese and Korean participants, particularly in the group conversations, strongly voiced their concern that drivers were racially discriminatory and would intentionally drive past them, which exacerbated their feelings of being left out of mainstream New Zealand society. A narrative example from the Chinese group, told in the course of a heated discussion about the wider prejudice older migrants experience, illustrates:

Y: Old men like us came to this place, it seemed we are taking the advantage of the government. This prejudice is added to our group. The society cannot have this kind of prejudice. After our children graduated from college, we agreed them to come to New Zealand. We spent a lot of time and energy to look after them until they grew up. We applied the visa and the government was willing to accept our applications. This is fair. People here cannot always think we are profit at other's expense. Speaking of loneliness, there may be some because we are not familiar with the social systems, but the mainstream's view about us make us feel even lonely. For example, they just talked about the bus, if it is local Kiwi waiting in that place, the bus would stop. If they see a Chinese person waiting in that place, the driver would not stop the bus. Sometimes when we got on the bus, and ring the bell, they still keep driving and stop at the next bus stop. It took us a long time to walk a long way back.

Z: This happens a lot, and sometimes we are making jokes with each other, saying ‘can you imagine how good their driving skill is?’ Obviously they see us standing here, but keep driving to another place to stop. We are 70 or 80 years old, but the bus drove past us and stopped ahead where it was more than ten metres away. I was joking about it: it's testing my ability to walk. Is the driving skill so bad? (Nodding from all members of the group) (Chinese men, CG)

Limitations to one's ability to get out of the house were especially important because ‘being out’ was seen as related to attaining social recognition and as well as maintaining a connection beyond their ‘four walls’. Group discussion participants and Māori participants in particular emphasised the importance of volunteering as a way of being engaged in the community themselves and the best way to help others. Offering the first response in the larger group discussion to a question about how older people can avoid loneliness, an older NZE participant explains the importance of connection:

As long as people are physically able of course, but I think one of the things to help really is to volunteer in the community if possible. And it gives people something to get out of bed and, you know, aim for. Something they're committed to and get into it, they get regimented. And then working with people and really getting to know people, instead of just sitting within four walls. (EM, MxG)

Losing one's mobility was by no means the end of social connections. However, it did increase the necessity for leveraging pre-existing social capital, which, as explained below, often led to feelings of burden.

The local neighbourhood was on the whole treated as an ambiguous site for social connectedness. Being able to speak to one's neighbours was seen as a way to get regular casual contact:

Interviewer: What about your neighbours here?

MF02: Oh yeah. Great connection with my neighbours.

Interviewer: And how many are you close to here?

MF02: Well, there's only one actually. Her and I are both Māori and, you know. She does her own thing, I do my own thing, but we do have a cup of tea.

Interviewer: Once a week, or twice a week, do you think?

MF02: Well, it depends what's on our agenda for the week. But we say hello, ’cos I've gotta go past her unit. And I go, ‘oh mōrena’ [morning]. And then she'll go, ‘mōrena’.

Nevertheless, a number of participants discussed how their neighbourhoods were changing which meant there were no longer opportunities for such casual interactions, and could even become a site for fear or feelings of abandonment when they did not meet their ideal of what a community should be:

…nobody's staying where they used to live for 20, 30 years. People are coming and going all the time, so nobody's actually reaching out into their neighbourhood. (EM09)

Other participants emphasised their desire to spend time around people in coffee shops or malls, which appeared to be more about being seen as social beings than necessarily having conversations with others. Nevertheless, participants also expressed concerns around finances as an additional limitation to socialising, especially for those reliant solely on their government pension for income, as a Korean group discussion participant succinctly put it: ‘[b]ecause we feel hesitant due to financial matters, we tend not to meet up as often’ (F, KG). Other community-based organisations such as the church and ethnically specific community groups and services were seen as good ways to connect, but enthusiasm for these groups was tempered around getting to these spaces as well as conquering nerves of going to a new group of people for the first time. Chinese and Korean participants discussed various community groups formed by older Chinese and Korean people themselves. One founded her own choir with someone she met through another Chinese-specific community group she attended. Lack of funding was seen as a barrier to this:

The government can pay attention to the elderly activity centre, organise some activities; these all need money. (AF01)

The desire to get out of the house was also influenced by their views on their current living situations. Some participants expressed a desire to socialise outside the home because it was too much energy to host people at their own space:

Interviewer: And do you meet your friends often?

AF07: Yes, I have many friends. In the past I played mah-jong twice a week at my home. Friends come to me to play mah-jong [which] could be very troublesome. Like some men need to use the toilet, they need to pass through my bedroom. After they left, I had to mop the floor, and I was really tired. Until in March this year I stopped playing it, not in my house anymore.

Many of our participants, either living with family members or council housing, felt they did not have space to host others which was a barrier to establishing or continuing connections:

But any friends I have, want to have, I can't, because I have to share and tell my kids I have somebody coming. And because they have to sort of clear their way and for me to have that space, like today. (PF04)

The ability to connect

Having the capacity to communicate with others was essential to enabling participants’ sense of connection. Participants drew on personal experience or what they had observed in others to indicate that the loss of eyesight and hearing resulted in uncomfortable social interactions and affected confidence for socialising. This played out in the mixed ethnicity group discussion where an initially jovial interaction ended on a more sober note:

Interviewer: Once you start losing your hearing or maybe your eyesight, does that lead to loneliness too?

FE02: Frustration, not loneliness, frustration.

MM03: Yes, yes it does.

Interviewer: Yes it does?

MM03: Like myself, I'm partly losing my sight. By that I can only see from one eye, and my children always say oh you're only one-eyed anyway, you know. (Laughter)

Interviewer: You're funny.

MM03: And you start losing your hearing, that is even worse because you can see them talking but you can't hear what they're saying. What are they talking about? Okay, you know, and you go up to them and say what have you been saying about me, and they all look ashamed and walk away. And that's what happens. (Quiet ‘hmms’ and long silence)

In general participants said they preferred community groups that were grounded in their own culture and language. For example, many Māori participants described how they enjoyed the kaumātua (Māori elder) day-programme because it was designed around shared customs such as karakia (prayer) and the sharing of food.

Participants who were late-life migrants (all Asian and most Pacific participants) highlighted just how exclusionary not being able to speak English proficiently was in their everyday life. Asian participants lamented the catch-22 that not being able to speak English made it even more difficult to figure out how to get lessons to learn English and their reliance on the pension made it difficult to pay for them. Not speaking English also left late-life migrants in particularly precarious situations when anything happened to their existing social support network:

When we first moved here, if there are Korean people we all became friends, then now, since we have been here long and since this [admission to hospital] happened to my husband [we] all disconnected. And besides, there is no single Korean person living around this neighbourhood. No one in this area, I am alone … there is no one I can talk to. It's very much, futile. Living is. It's only my sons, no one else I know. Even the neighbours, I can't talk to them, I can't talk [means she can't speak English]. (AF01)

These participants also tried to ameliorate their lack of social connection in their immediate surrounding by using telephone and/or social messaging platforms such as Skype, Weibo or Kakkako to connect with family and friends at home. This kind of technology was also used to sustain a connection to nationhood and a broader sense of community. European participants for the most part expressed an up-to-date knowledge of the news (either via the radio or newspaper) to communicate their connection to New Zealand society. As one participant put it ‘we're all in this together’ (EF03). By contrast, Korean group discussion participants expressed feelings of alarm when it arose through conversation that only one of them knew that the former New Zealand Prime Minister had recently resigned. All male participants in the in-depth interviews used email, and two used Facebook, to maintain their business contacts and/or connection with other organisations of men. Female (other than Asian participants) were more likely to emphasise the digital divide which was a barrier to others to connect. As one lamented:

I'm sure there are lots of lonely people like me. You know, I don't know how we meet them, you know. Somebody said go online, and I thought well that'd be fun, but I haven't got a computer. (EF11)

Participants also contextualised their ability to connect in relation to their own personality. For example, one participant who offered a detailed account of her wide social network described herself as a ‘person who loves people’ (OF01). By contrast, a few participants described themselves as always being ‘loners’, yet on closer inspection of their narratives this often seemed to be both complicated and to be temporary rather than a life-long persona. For example, one participant, who originally described himself as a ‘solitary fella’ (MM09), explained that after losing his wife with whom he used to do everything, he forced himself to join local organisations, meaning he now found himself feeling more socially connected in later life. Notably, however, he still regarded his late wife as his closest contact during the mapping exercise, revealing how intimate connection does not cease necessarily with the death of a loved one.

Feelings of burden

Underpinning discussions of what helped and hindered participants to connect was an emphatically expressed desire not to burden others. Participants strove to portray themselves as resourceful and agentic and often focused their narratives on outlining what they did happily on their own as much as what they did with others. European participants also seemingly emphasised their hobbies and awareness of current affairs to illustrate that they were interesting people worthy of company. Where participants described situations when they had encountered loneliness they always showed what they had done about it. The participant below highlights a typical example:

Interviewer: So that's when you know you're lonely, when you have this feeling of –

PF04: Of something like in your mind, you can feel not, that's not you. And that's why I reach out, I think I reach out to my bible, I pray at that time, in that moment, and read. And then after I read, I put it out and say my prayer, and this is my every day thing now. I know, it wasn't there before, now it's here.

Feelings of burden were closely associated with family narratives. While some participants felt especially ‘emotionally close’ (EF03) to some members of their family and enjoyed their company, the fundamental thing that made these interactions positive was whether they perceived a mutually reciprocated desire to spend time together. This is outlined in a 92-year-old female participant's account of her relationship with her son, which bolstered her enduring identity as a mother and a home-maker:

One son, the one that's not married, he comes every Wednesday night for dinner. So that keeps me cooking, you know? (EF02)

Nevertheless, there was a strong feeling of not wanting to bother family members, which often meant they limited the amount of support and degree of contact they had with their family:

My son is always available, my daughter-in-law and I've got a sister-in-law who's available. Yeah, but you know, a lot of times you don't feel like asking them because you know that they're busy with their lives. Yes, so I try to make do without having to depend on them. (MF04)

In other cases participants felt let down by their families and therefore turned their efforts to making friends based on mutual interests or circumstances, as captured in this group interaction:

…I left about 48 years ago now, and I've only just moved back two years. And I came back ’cos my family are here, and I wanted to get to know them again, and for my children to know them. And I've been to see them, but you know, they weren't coming to my place and I thought oh that's funny, so I go out of my way to see them. And I said ‘blow this, if they're not going to come and see me I can go elsewhere’. So then I started, and I said ‘there's swimming, aquarobics’ ’cos I started going to that just to get in with people, you know, make myself feel, put myself out there to communicate with other people, you know. And I think it works both ways, you've got to make the effort to get out there and do something eh. Not just stay at home, ’cos I was like that for about four days and I said ‘oh gee, this is boring, this is not me, I'm not one of these ones that just sits at home and just watches TV, I want to get out’. And then my family started coming home and they'd leave a note on the door, Aunty where are you? My sisters are ‘where are you? where are you roaming?’, so I had to put a note on the board and ‘say come back and see me after 3 o'clock when my mokopuna's [grandchild] home. This grandmother's got a life!’ (Other participants erupt in laughter) (MF, MxG)

Male participants spoke about friendships as a space to learn new things and women talked about the importance of having close friendships; as one female European participant termed it, ‘di dinky’ (true and reliable) friendships (EF03), which enabled you to share your emotions and health concerns. Friendships were also celebrated, even in their absence, for their ability to enable further social interaction and access to other social spaces:

I have no one. No intimate friends? If there are close friends, I can go out with them and have a cup of tea, do shopping, and chat (laughter), how happy that would be. (AF01)

Notably, friendships featured far less in Pacific participants’ narratives, which tended to be centred on the importance of close connection to their family with whom most lived. There was also mention of desire for new romantic companionship from participants who did not or no longer had a spouse (noting that 38 of the 44 participants were in this category). This aspiration was usually discreetly alluded to in private interviews rather than explicitly outlined. One participant discussed her routine of visiting her new ‘companion’.

Finally, pets provide yet another insight into the importance of mutuality. Seven of our participants had either a cat or a dog but they did not speak in any particular length about them. For our three participants who shared their pets with other members of their family, pets instrumentally enabled their feelings of social connectedness because it meant they were doing something useful for their family as well as ensuring regular contact between them. In the remainder of cases participants did not have pets; many said this was because they did not think they could look after them effectively or expressed some conflict about whether the feeling of connection they might attain from a pet would offset the burden involved with taking care of them.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to examine enablers and barriers to social connectedness from the perspective of older people themselves. Moreover, by including a culturally diverse set of participants and utilising a culturally comparative approach, we have been able to capture empirically how social connectedness is a culturally mediated and constantly negotiated phenomena, rather than a universal construct (Townsend and McWhirter, Reference Townsend and McWhirter2005). Our findings also highlight that social connectedness is understood by older people as a multi-levelled concept which encompasses the quality of relationships between individuals and families, as well as a sense of belongingness to one's neighbourhood, community and wider society (Register and Scharer, Reference Register and Scharer2010). Older people can feel socially connected on one of these levels, but at the same time lack a sense of social connection on others. Taken together, these novel insights help respond to key gaps in the literature and policy by providing culturally inclusive evidence upon which to base future interventions to promote social connectedness.

Overwhelmingly we found that, in line with previous studies, our participants sought to portray themselves as having agency and being resourceful, and wanted to be able to foster relationships on the basis of mutual respect whilst also bolstering their preferred social identities (Goll et al., Reference Goll, Charlesworth, Scior and Stott2015). Participants did not want to be viewed as a burden on others, especially their families, and many exerted considerable self-regulation (Register and Herman, Reference Register and Herman2010) to cultivate their interests and emotions in order to be viewed by others as socially desirable. This included emphasising the importance of friendships, which signalled freely formed relationships and potentially lessened their reliance on family (Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Hank and Künemund2009; Shin, Reference Shin2014). We also found that participants deployed personality archetypes such as that of being a ‘loner’ or a ‘people's person’ in order to control the interpretation of their situation, thus emphasising the need to not take these labels on face value when conducting health or social care assessments and when doing research (Cohen, Reference Cohen2004). This process of social positioning also highlights how participants drew on related, albeit separate, concepts such as loneliness and belongingness when trying to convey narratively their experiences of connectedness across different levels of interaction, such as family, neighbourhood and society. Future research could utilise non-representational theories of health that combine material, sensory and affective processes with conscious thought and agency in order to explore further how social connectedness is made, negotiated and narrated in everyday life (Andrews, Reference Andrews2018).

Participants’ desire for independence underpinned their strong emphasis on getting out of the house in order to feel connected with the outside world by participating in ‘third spaces’ such as coffee shops and malls (Gardner, Reference Gardner2014). Participants saw the main barriers to achieving connection at this meso-level as structural factors such as limited and unreliable public transport and staff who did not always treat them appropriately or with respect; for some participants, particularly from minoritised groups, this was exacerbated by overt racism towards them. This highlights the urgent need for more age-friendly city planning and age- and diversity-awareness of public transport staff (World Health Organization, 2007). Community organisations and policy makers also need to think about availability of transportation when planning their social interventions and reconsider whether home is always the best setting for interventions such as befriending services (Emlet and Moceri, Reference Emlet and Moceri2012).

However, our findings also support previous research which has identified the role that health-related factors such as mobility and diminished energy play in directly and indirectly supporting participants’ ability to connect socially (Heylen, Reference Heylen2010; Smith, Reference Smith2012). In line with Victor and Bowling (Reference Victor and Bowling2012), we see that support and/or treatment of people's chronic health problems would help to improve older people's opportunities for socially meaningful lives. In situations of poor health, we found that proximal environments, especially relationships with neighbours, became increasingly important for opportunities for daily experiences of connection (Yen et al., Reference Yen, Shim, Martinez and Baker2012; Michael and Yen, Reference Michael and Yen2014). Nevertheless, due to increasing rents and job-market precariousness, neighbourhoods (especially in our large metropolitan field site) were felt to be transitory and no longer offer the often-idealised form of social support, such as positive neighbouring, that our participants desired (Scharf and de Jong Gierveld, Reference Scharf and de Jong Gierveld2008; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Moyle, Ballantyne, Jaworski, Corlis, Oxlade, Stoll and Young2010; Bantry-White et al., Reference Bantry-White, O'Sullivan, Kenny and O'Connell2018). This, along with widespread concerns about broader structural factors such as the level of the pension and inability to afford accommodation acceptable for socialising, highlights how both micro- and macro-economic considerations inhibited participants’ ability to connect (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Abolfathi Momtaz and Hamid2013) and at worst exclude people from having a public life altogether (Weldrick and Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018). Governments need to take the lead by endorsing policies like rent caps that will support longer tenancy in neighbourhoods, especially in contexts of declining or low home-ownership rates among older people. Governments also need to adjust the pension to a liveable rate that ensures older people can afford to socialise, given the importance this on their health and wellbeing (New Zealand Treasury, 2018).

In addition to the substantial similarities across participants, we also found important differences. Most of our participants preferred to socialise with people from similar cultural backgrounds where they shared taken-for-granted social customs and knowledges. This played out in more abstract levels as well, e.g. NZE participants liked to stay abreast with mainstream national news in order to commune with their ‘imagined community’ of New Zealand society (Anderson, Reference Anderson1983; Register and Scharer, Reference Register and Scharer2010). This same media, however, was perceived by Asian participants as fuelling the racism they experienced in everyday life. When thinking about designing interventions for diverse populations, policy makers need to consider how enablers of social connectedness for some (especially the culturally hegemonic group) can result in social exclusion for others (Weldrick and Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018). Late-life migration also plays an important role in inhibiting social connection to the wider community, although a critical factor appears to be English proficiency rather than ethnicity per se (Park et al., Reference Park, Morgan, Wiles and Gott2019). Making English-language courses widely available and free would help improve this. Nevertheless, we observed differences within our Pacific and Asian late-life migrants. The former tended to overwhelmingly live with their families and feel connected to them (although they may feel cut off from having friends), while the latter chose not to live with family in order to not burden them (Park, Reference Park, Morgan, Wiles and Gott2019). Our findings thus help to provide additional insight into the findings of Jamieson et al. (Reference Jamieson, Gibson, Abey-Nesbit, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Keeling and Schluter2017) that Pacific and Asian elders can feel lonely even when living with family. With regard to gender, we found that men in our sample all used either email or other forms of social media regularly to maintain their professional, public identities, whereas women in general preferred individuated, emotionally nurturing and ‘dinky-di’ friendships, thus reflecting more traditionally gendered sociability (Hurd-Clarke and Bennett, Reference Hurd-Clarke and Bennett2013). Consequently, when planning policies at either national or local level to support social connectedness in older age, it is critical to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and/or making assumptions about what a particular cultural group would benefit from, which may exacerbate barriers to connectedness particularly for the most minoritised groups, and focus rather on giving older people options.

In line with previous research, we also found that feelings of social connection could improve in later life (Cornwell et al., Reference Cornwell, Laumann and Schumm2008; Victor et al., Reference Victor and Bowling2012). While this might be explained in the context of ‘coming to terms’ with one's new situation (Victor and Bowling, Reference Victor and Bowling2012), we also found that it was an outcome of some participants expanding their social connections in the community (Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Hank and Künemund2009). This was sometimes as a result of a ‘push’ factor such as the death of a spouse, however, this connection was also enabled by the availability of community resources. For example, some participants became more socially connected by joining and/or volunteering for organisations so as to give back to the community (Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Breheny and Mansvelt2015), something especially important for Māori participants whose cultural values reflected relationships strengthened by the practice of maanakitanga (reciprocal caring) and for Pacific participants who privileged their spiritual communities. Asian participants explicitly requested more public resources to help them initiate new community groups, which Wright St-Clair and Nayar (Reference Wright-St Clair and Nayar2017) have aptly highlighted as an effective strategy of cultural enfranchisement. Providing clear avenues for older people to volunteer for existing organisations (which may include transport for them to get there) as well as providing support for older people to start their own groups (by offering community spaces at no charge or providing starter funds) are practical steps government and third-sector groups can take to promote social connectedness (Emlet and Moceri, Reference Emlet and Moceri2012).

Strengths and limitations

Using the mapping tool to begin individual conversations about people's social connectedness proved a useful way to begin to discuss social contacts without restricting the talk to their specific social networks. This process also made it very clear who did not have many (or any) close connections. Participants in this situation took the mapping exercise as a platform to explain and illustrate their current social situation, often bringing their narratives back to their agency and resourcefulness; however, we understood this strategy to be inappropriate for some cultural groups and should not be imposed on participants. Another strength of our cross-culturally designed project is that we had recruiters and interviewers who were culturally and linguistically matched which helped immensely with data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, as our research participants came from four very broad and uniquely New Zealand groupings we could not capture the diversity of each of the cultural groups. Given the sensitive nature of this research, there was a need to build rapport with participants; a potential limitation of the study is that we did not conduct multiple in-depth interviews with participants. However, we went to significant lengths to ensure participants were familiar with interviewers before the interview. The small numbers of men willing to participate in the Māori, Pacific and Asian groups meant we are unable to provide an in-depth comparative gendered analysis.

Conclusion

This paper reflects a diverse group of Pacific, Māori, Asian and NZE older adults’ views on what enables and/or impedes social connectedness. We identified three themes that underpinned their experiences of being socially connected: getting out of the house, the ability to connect and feelings of burden. Our analysis demonstrates that older people conceptualise social connectedness as a multi-levelled concept that reflected relationships of affinity on the interpersonal level (family, friends), the meso-level of neighbourhood and community, and at the level of culture and society. Our participants highlighted that it was possible to be connected on some levels and not others. Moreover, because social connectedness was a gendered and culturally navigated experience, what enabled social connectedness for some groups could be a barrier to others. Our participants’ reflections demonstrate that racism, poverty and inequalities clearly exacerbate social isolation and loneliness, particularly for groups that are minoritised. Conversely, a variety of underpinning structural conditions, such as stable neighbourhoods serviced with accessible public transport, liveable pensions and availability of community organisations, and inclusivity, are all fundamentally conducive to social connectedness.

Acknowledgements

We would like thank our participants for their generosity of their time and insights. Thank you to Anne Koh, Emma Moselen and Jinglin Lin who helped with interviews and Jing Xu who helped with translation. We thank Louise Rees, Judith Davey and Robyn Dixon for their wider support of the project. We thank the various organisations which supported this research, including: Age Concern, Salvation Army, Treasuring Older Adults Inc., Waitemata and Counties Manukau Older People's Needs Assessment and Service Co-ordination teams. We thank the Te Arai Palliative and End of Life Care Advisory Roopu for their guidance and active support.

Author contributions

All authors helped with the conceptualisation of the project, the analysis of the data and editing of the manuscript. TM, LW, SB, TM-M, OD and H-JP were involved in data collection. TM, JW and MG were involved in the drafting of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment National Science Challenge under the Ageing Well fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was gained from the University of Auckland's Human Participants Ethics Committee in April 2016 (016593). Additional health board-specific ethics approval was attained for recruitment of participants via Older People's Needs Assessment and Service Co-ordination teams at two hospitals: Counties Manukau Research Office (2291) and Waitemata DHB (RM13321).