Introduction

Former German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, was once a staunch advocate of nuclear energy, until March 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear disaster occurred. Following the disaster, Merkel underwent a dramatic policy U‐turn: after her government decided to extend the lifetime of the nuclear power plants for an additional 14 years, Merkel became a vocal proponent of a phase‐out plan, citing the risks associated with nuclear energy and the Fukushima accident.Footnote 1 Ten years later, in March 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron made a sudden reversal in policy regarding the AstraZeneca vaccine against Covid‐19. Initially limiting its use to individuals under 65 because it was ‘almost ineffective’ for older people, Macron later expanded the vaccine's use to those over 65 following new scientific evidence from the European Medicines Agency.Footnote 2 Examples of politicians making overt policy reversals following major crises or expert advice are countless. Surprisingly, however, we know very little about how voters evaluate parties and politicians in such circumstances.

Our study contributes to answering the following research question: How do voters evaluate abrupt policy U‐turns? This question is highly relevant for the effectiveness of democratic representation and political accountability (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Stokes, Reference Stokes1999). On the one hand, if citizens generally punish politicians for changing course, they would be encouraged to stay put even if the circumstances change, putting the effectiveness of public policy in jeopardy. If people condone U‐turns, on the other hand, politicians will have no motivation to tell the truth as long as they can renege on their pledges at no cost in the future (Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012).

To advance academic debates on this question, we seek to connect the causes and consequences of policy U‐turns, a synergy overlooked in the literature. We blend the empirical literature on political repositioning and theoretical literature on political representation (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell1994; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Stokes, Reference Stokes1999) and suggest that voters should evaluate policy change based on their perceptions of why the change happened in the first place. Because repositioning can potentially convey ambiguous signals about political actors (e.g., Nasr, Reference Nasr2023; Riker, Reference Riker1990), voters must rely on simple decision rules to determine whether party actions are credible or opportunistic (Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019). On the one hand, shifts in position can be interpreted as a manifestation of negative political qualities, such as inconsistency or political opportunism. For instance, political parties may emphasize alignment with voters' desires, only to subsequently implement policies that might be detrimental to the well‐being of those very same voters (Stokes, Reference Stokes1999). On the other hand, positional shifts can signify open‐mindedness, flexibility and a willingness to adapt to evolving circumstances (Sigelman & Sigelman, Reference Sigelman and Sigelman1986; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). The question then arises: how do voters differentiate between these two types of change: the principled and the opportunistic?

In the current study, we seek to explore a previously uncharted factor, namely the motivation behind the policy change. We contend that voter perceptions of the motivation why the party changed should play a major role. A change made in response to external events, such as addressing a crisis or aligning with scientific evidence or expert advice, is less likely to be seen as opportunistic compared to changes made for political reasons, such as seeking a cabinet position or following the ascent of a new leader. Although past literature finds that voters generally dislike positional changes (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Nasr, Reference Nasr2023; Robison, Reference Robison2017; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012), they should exhibit less scepticism towards changes motivated by external factors, as such adjustments may become necessary for the party or government to adapt its policies to evolving circumstances. In contrast, changes motivated by political considerations are more likely to be perceived as less credible and therefore discounted or punished (see also Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2020).

To test voter reactions against this yardstick, we distinguish between two classes of policy U‐turns. The first, which we call principled U‐turns, is undertaken in response to external events or exogenous, mainly apolitical, stimuli. Examples include the changes committed because of new scientific evidence or expert advice suggesting that the initial position of the party was wrong, or because of a large‐scale crisis that requires urgent response. The second, what we call strategic U‐turns, refers to policy reversals motivated by political considerations. Examples of such policy changes are numerous, but we focus on two examples of somewhat different nature: changes undertaken for office‐seeking motivations, for instance, when the party adjusts its position to participate in a newly forming government or a change brought about by a new party leadership. Since voters are generally risk‐averse and allergic to uncertainty (Alvarez, Reference Alvarez1998; Glasgow & Alvarez, Reference Glasgow and Alvarez2000; Shepsle, Reference Shepsle1972), we maintain that they will typically hold a negative view of policy reversals driven by strategic motives. Second, in contrast, we argue that principled policy U‐turns are generally desirable and, therefore, should be subject to less negative perceptions and evaluations.

Our study speaks to the literature on the causes and consequences of position change. Previous research has extensively investigated the causes and motivations for repositioning (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009b; Budge, Reference Budge1994; Harmel & Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994; Harmel et al., Reference Harmel, Heo, Tan and Janda1995; Janda et al., Reference Janda, Harmel, Edens and Goff1995; Pereira, Reference Pereira2020; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013), but – strikingly – the repercussions of such changes have received far less attention (Adams, Reference Adams2012). Existing research overall suggests that voters dislike candidates and parties who change course (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Nasr, Reference Nasr2023; Robison, Reference Robison2017; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). However, change might become necessary in some situations, for example, in the event of a large‐scale crisis that threatens the society at large or with the arrival of new policy‐relevant information, expert advice or scientific evidence. Yet, to date, we do not know how voters react to what we refer to as ‘principled’ U‐turns, implying that voters may care about the specific motivations for sudden policy changes.

Based on a pre‐registered survey experiment fielded in Germany (n = 3127),Footnote 3 our results are surprising. We find that voters tend to penalize political parties when they backtrack on their positions, irrespective of the underlying motivation, even when external circumstances necessitate a change. However, our online supplementary analysis uncovers intriguing patterns. Firstly, the degree of similarity plays a significant role, as the negative consequences of policy reversals are overturned when the party ultimately aligns with the voter's stance. Secondly, trust also emerges as a critical factor, as individuals with higher levels of political trust exhibit a greater willingness to tolerate repositioning, even when they are subjected to the strategic office‐seeking treatments. Considering that external circumstances such as crises or new evidence may render a reevaluation of a party's prior position imperative, these findings have direct implications for democratic governance.

Rewarding versus punishing policy U‐turns

We adopt a dynamic analytical lens and study the case where the party signals its policy views at two‐time points:

![]() $\tau _{1}$ and

$\tau _{1}$ and

![]() $\tau _{2}$. Furthermore, we are interested in a scenario where the party changed its policy orientation between these two‐time points. It is worth noting that our approach to policy U‐turns primarily focuses on reversals in the substantive issue positions (e.g., Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021) rather than the importance parties assign to particular issues or the manner in which they frame them (e.g., Bisgaard & Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018). By doing so, we also focus on party repositioning on salient issues – in line with past work on repositioning (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Robison, Reference Robison2017; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012) – rather than on incremental ideological moderation or radicalization (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009a; Downs, Reference Downs1957).

$\tau _{2}$. Furthermore, we are interested in a scenario where the party changed its policy orientation between these two‐time points. It is worth noting that our approach to policy U‐turns primarily focuses on reversals in the substantive issue positions (e.g., Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021) rather than the importance parties assign to particular issues or the manner in which they frame them (e.g., Bisgaard & Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018). By doing so, we also focus on party repositioning on salient issues – in line with past work on repositioning (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Robison, Reference Robison2017; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012) – rather than on incremental ideological moderation or radicalization (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009a; Downs, Reference Downs1957).

We begin with the premise that the credibility of elite promises is essential for a well‐functioning representative democracy. Furthermore, we posit that temporal stability and consistency are important sources of credibility. Early research on social psychology revealed that voters tend to disregard candidates who express different views at different points in time – what they call ‘the waffling phenomenon’ (Allgeier et al., Reference Allgeier, Byrne, Brooks and Revnes1979; Carlson & Dolan, Reference Carlson and Dolan1985; Hoffman & Carver, Reference Hoffman and Carver1984; McCaul et al., Reference McCaul, Ployhart, Hinsz and McCaul1995). In line with this phenomenon, recent empirical research on public opinion demonstrates that voters, indeed, punish political parties or candidates who undertake significant positional reversals (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Nasr, Reference Nasr2023; Robison, Reference Robison2017, Reference Robison2022; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). In international relations, research indicates that leaders often experience a decline in popularity after they back down on their initial promises and positions during international crises (Fearon, Reference Fearon1994; Levendusky & Horowitz, Reference Levendusky and Horowitz2012; Sigelman & Sigelman, Reference Sigelman and Sigelman1986; Sorek et al., Reference Sorek, Haglin and Geva2018).

This research generally suggests that voters dislike positional inconsistency for two interrelated reasons. First, parties that change positions too frequently or explicitly might raise voters' uncertainty. Since voters are generally risk‐averse and allergic to uncertainty (Alvarez, Reference Alvarez1998; Glasgow & Alvarez, Reference Glasgow and Alvarez2000; Morgenstern & Zechmeister, Reference Morgenstern and Zechmeister2001; Shepsle, Reference Shepsle1972; Weber, Reference Weber1999), they will shun parties that change positions. Second, radical changes can damage the party's public (or so‐called valence) image by portraying it as overly opportunistic, incompetent or untrustworthy (Andreottola, Reference Andreottola2021; Hummel, Reference Hummel2010; Nasr, Reference Nasr2023; Sigelman & Sigelman, Reference Sigelman and Sigelman1986; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). In the words of Riker (Reference Riker1990, p. 56), ‘A politician's move from an extreme right to an extreme left seems too opportunistic that voters infer that he believes nothing. They reciprocate by believing nothing he says’. Thus, in line with past research, our baseline hypothesis anticipates that our respondents will evaluate a party that commits a policy reversal more negatively than if it remains steadfast.

General hypothesis (H1): Generally, voters will punish policy U‐turns, all else being equal.

Although policy U‐turns can often create a negative impression of a political party, consistency may not necessarily have to come across positively. In some situations, such as when the circumstances change significantly, dogmatism could endanger the efficiency of public policy, and a change in perspective might become necessary. Therefore, we contend that policy U‐turns should be evaluated based on voters' understanding of what motivated it in the first place. From a normative perspective, although voters are unlikely to tolerate policy U‐turns, they should be less critical when such changes are made in response to (new) scientific evidence or to address a large‐scale crisis that poses a significant threat to the well‐being of the society at large. Therefore, rather than considering the type of policy (Tavits, Reference Tavits2007) or the party involved (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004), we break new ground in the empirical literature by connecting the consequences to the causes of policy U‐turns. In doing so, we investigate if voters will tolerate principled policy reversals.

We formulate several, pre‐registered hypotheses which we build on ‘mental models’ – a notion we borrow from cognitive psychology (Gigerenzer et al., Reference Gigerenzer, Hoffrage and Kleinbölting1991; Johnson‐Laird, Reference Johnson‐Laird2001). Simply put, mental models describe the mental processes that allow one to draw probabilistic predictions about the future that are consistent with current premises (Johnson‐Laird, Reference Johnson‐Laird2012, p. 116). We expect that voters will prospectively evaluate party behaviour in the future based on their current behaviour. If they perceive that a party has shifted its positions out of self‐interest or for strategic reasons, they will likely form a negative evaluation, as they may expect the party to prioritize its self‐interests in the future as well. In contrast, this negative feedback is less likely to apply to policy reversals made for principled reasons.

To test if voters indeed exhibit this behaviour, our experiment differentiates between two types of policy U‐turns. The first is the one necessitated by new scientific evidence or expert advice indicating that the initial party stance may have been wrong or sub‐optimal, or by a crisis demanding an urgent response. In these situations, a change is not only preferable but may also be necessary to maximize the efficiency of public policy and prevent adverse consequences for society. In this context, we contend that respondents are more likely to tolerate such principled policy reversals because they are likely to perceive them as credible.

Principled U‐turns (H2): Voters will tolerate policy U‐turns backed by scientific evidence or induced by a large‐scale crisis.

The second type of policy reversals is committed for strategic or political motives. In many European democracies, this may occur during post‐election negotiations with potential coalition partners in order to secure representation in the cabinet. This change reflects the party's behaviour driven by the pursuit of political office (office‐seeking). In addition, politically motivated changes can also happen as a result of organizational change within the party, such as when a new party leader is selected (Fernandez‐Vazquez & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Somer‐Topcu2019; Harmel & Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994; Janda et al., Reference Janda, Harmel, Edens and Goff1995; Meyer, Reference Meyer2013). It is worth noting that the role of leadership change may engender some debates. Somer‐Topcu (Reference Somer‐Topcu2017) contends that although a change in party leadership may project an image of credibility, it also provides adversaries with an opportunity to criticize the party's new policy orientation, denigrate it and expose its policy reversals to the public as opportunistic and inconsistent. Furthermore, we also perceive policy revisions following leadership change as less pressing compared to external factors. Bille (Reference Bille1997) indicates the absence of a direct relationship between new leaders and party positional changes in Denmark during the period of 1960–1995. Similarly, cross‐country analysis conducted by Meyer (Reference Meyer2013) fails to provide support for the hypothesis that new leadership incites shifts in policy or ideological positions. These findings suggest that a correlation between leadership turnover and party change is not the prevailing pattern in liberal democracies. Fernandez‐Vazquez and Somer‐Topcu (Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Somer‐Topcu2019) further reinforce the notion that the absence of change despite the emergence of new leadership is ‘more common than generally thought’ (p. 978). Due to limited information available to voters about the internal processes within the party that drive such changes, we expect there can be a tendency for the voters to perceive them negatively. Consequently, this can augment scepticism and confusion among the electorate. Hence, our third hypothesis anticipates the following:

Strategic U‐turns (H3): Voters will punish policy U‐turns motivated by political reasons, such as to access the government or as a result of new leaders.

Last but not least, we investigate voters' evaluation of positional consistency despite new scientific evidence inviting a change. Although previous research suggests that voters value consistency, we suspect that voters may not value consistency in the arrival of new policy‐relevant information suggesting that the party has to adjust its policies. This leads to our fourth hypothesis:

Consistency hypothesis (H4): Voters will punish parties that stand still despite new scientific evidence, suggesting they are wrong or a crisis that requires policy adjustments.

Data and methods

We conducted a pre‐registered survey experiment in Germany to test our hypotheses. The survey was conducted online by Bilendi in October–November 2022. We opted for a representative sample of the German population amounting to 3127 respondents.Footnote 4

The experiment featured two policy issues: the vaccination of children against Covid‐19 and the nuclear phase‐out plan. The selection of these policy issues was motivated by several reasons. Firstly, at the time of the study, these two issues were highly salient in Germany. The ongoing Covid‐19 crisis and the associated debates on vaccination against the virus were at the forefront of public discourse. Similarly, the debate surrounding the nuclear phase‐out plan gained widespread attention, driven by the energy crisis following the conflict in Ukraine. Secondly, these policy issues are particularly relevant for examining both strategic and evidence‐based changes. The pressure placed on political parties and their leaders in both situations, coupled with the mounting scientific evidence regarding the plausibility of the phase‐out plan and the necessity of vaccinating children, made policy U‐turns a plausible outcome for both strategic and principled reasons.

Experimental design

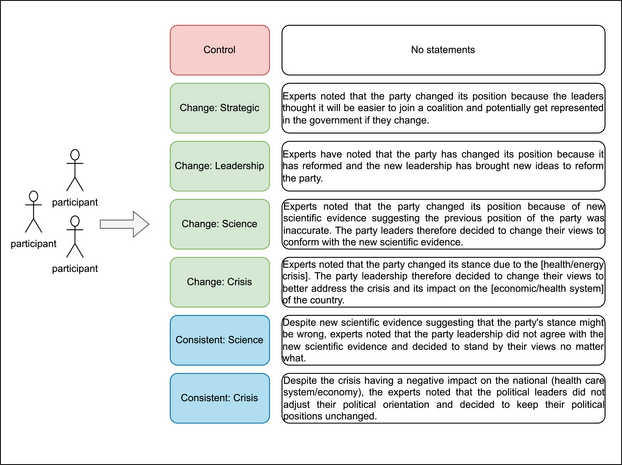

Our experiment begins by asking respondents to report their preferences on two policy issues: vaccinating children against Covid‐19 and the nuclear phase‐out plan. Respondents were instructed to place themselves on a 1–7 scale, where 1 means strongly against and 7 strongly in favour. Next, they were randomly assigned to one of seven experimental groups as shown in Figure 1. Before delving into the experimental conditions, it is important to note that our experiment employs a between‐subject design for the aforementioned two policy issues. In addition, we randomized the presentation order of the policy issues within each experimental group to minimize any potential order effects. Furthermore, our experimental procedure also ensured that treatments for each policy issue were not randomized independently from one another, meaning that each respondent remained in the same treatment group for both policy issues. This choice was made to ensure that each respondent was exposed to only one treatment and to prevent any potential priming effects resulting from exposure to multiple treatments.

Figure 1. Experimental conditions.

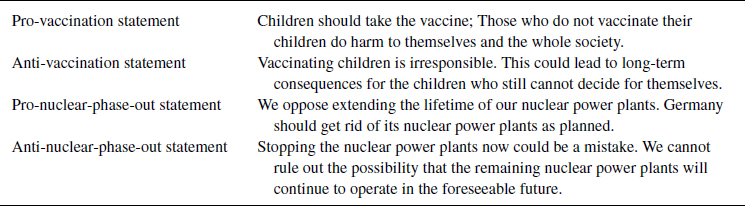

Respondents in the control group were asked to read a statement from a hypothetical party on each issue separately, with the position of the party randomized so that each respondent had an equal chance of reading a statement from the party in favour or against the Covid vaccination and the nuclear phase‐out plan. Therefore, the control group represents a consistent party with one policy position, represented by one of the policy statements included in Table 1.

Table 1. Policy statements

The subsequent four experimental groups (those in green in Figure 1) presented respondents with two statements from a political party committing a policy U‐turn, representing its previous and current positions, respectively. Most importantly, the respondents also read an introductory statement that referred to experts explaining why the party reversed its policy position over time. The explanations presented in Figure 1, including the policy statements found in Table 1, represent the main treatments of interest.Footnote 5

To test H2 and H3, four scenarios for policy U‐turns were included. The first two represented political reasons, aimed at either (1) joining a newly forming ruling coalition or (2) occurring as a result of new party leadership seeking to reform the party. The third and fourth scenarios were U‐turns inspired by principled reasons, namely either (3) undertaken to align with new scientific evidence or (4) to address a large‐scale crisis.

Lastly, the last two experimental groups (those in blue in Figure 1) aim to test our consistency hypothesis (H4). To do so, respondents read a statement from political experts explaining that the party refused to adjust its policy position despite (1) new scientific evidence (fifth group) or (2) an ongoing crisis (sixth group).

It is also worth noting that the experiment employs hypothetical parties, aligning with previous experimental studies (e.g., Johns & Kölln, Reference Johns and Kölln2020; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). The utilization of hypothetical parties helps mitigate the challenges associated with subjects potentially having been exposed to real‐world treatments before participating in the experiment, thereby addressing concerns related to pre‐exposure or pre‐treatment bias (Slothuus, Reference Slothuus2016). Furthermore, it enables us to disentangle reactions to policy changes from potential confounding factors, such as party identification. However, it is essential to acknowledge that this approach sacrifices some degree of mundane realism. Additionally, real‐world voter decisions may rely on various other factors, which could potentially lead to an overestimation of our treatment effects. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with these considerations in mind.

Our main interest is respondents' vote intentions, measured by the following question: ‘If there was an election tomorrow, how likely is it that you will vote for this party?’ They were asked to answer this item on a scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). A list of additional outcome variables and their measurements can be found in the questionnaire included in the online Appendix.

Results

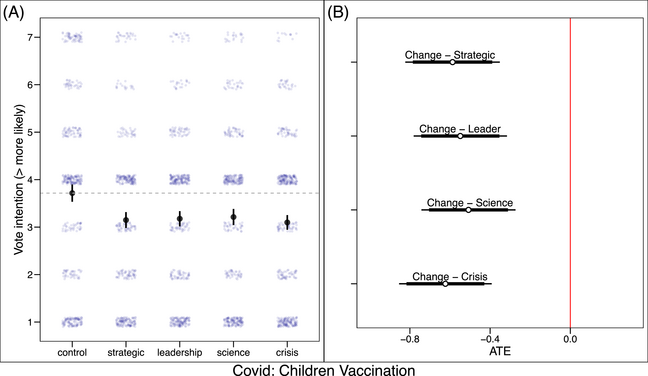

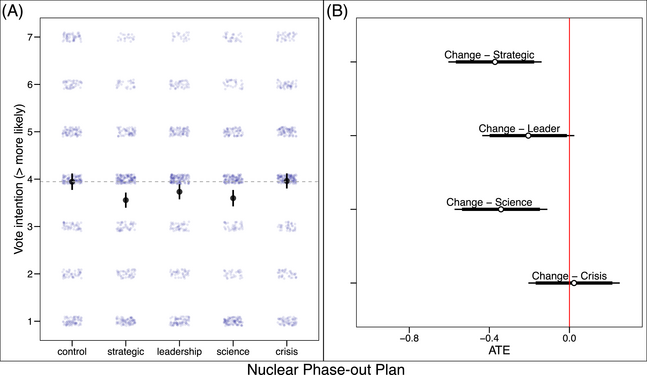

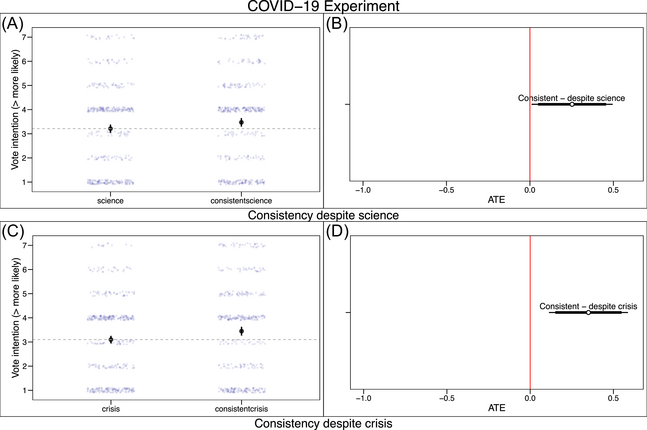

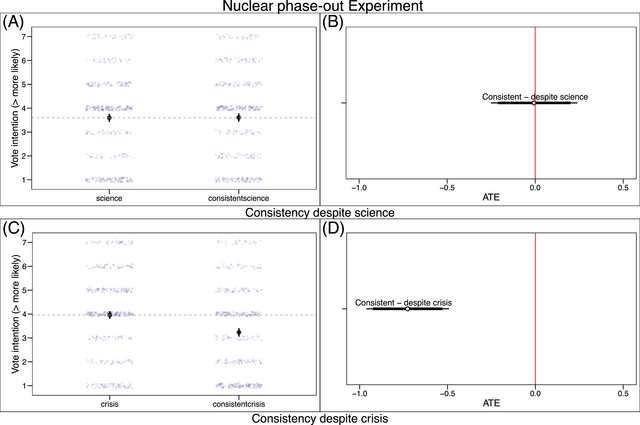

Consistent with our pre‐registration, we present separate analyses for the two policy issues examined in this study: vaccinating children against Covid‐19 and the nuclear phase‐out plan. To test Hypotheses 1–3, we compare the average vote intention of each of the four experimental groups featuring a policy U‐turn to the control group. We present the results for the vaccination issue in Figure 2 and for the nuclear phase‐out plan in Figure 3. In both figures, we display the average vote intention on the full 1–7 scale for each treatment group on the left‐hand side, and the difference‐in‐group‐means on the right‐hand side, which indicates the effect size (the average treatment effect, or ATE for short) and statistical significance of the treatment compared to the control group.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Main findings: Covid.

Figure 3. Main findings: Nuclear phase‐out.

Our first hypothesis, H1, predicted that policy reversals would generally be unwelcomed by the electorate, and our findings indeed confirm this expectation, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Respondents rated the party reversing its policy on our two issues less favourably than the control group. Moreover, in line with our third hypothesis, H3, we find that voters are particularly displeased with policy U‐turns motivated by strategic reasons. Interestingly, however, we do not find robust evidence to support H2, which suggested that policy U‐turns motivated by principled reasons would be viewed more favourably by voters. In fact, respondents in most of our scenarios were similarly disinclined to support parties that reversed their position. Specifically, respondents were about 0.5 scale points less likely to vote for a party that reversed its policy position, regardless of the reasons behind the U‐turn (p

![]() $<$ 0.001).

$<$ 0.001).

The aforementioned conclusion applies in particular to Covid‐19, whereas the findings for the nuclear phase‐out are somewhat different. In particular, we do observe a diverging trend in the case of a policy U‐turn motivated by a crisis in the nuclear phase‐out plan scenario. Respondents appeared to rate this U‐turn similarly to how they rated the control group (consistency), providing an intriguing insight into the nuances of electoral attitudes towards policy reversals. This finding suggests that voters might, indeed, tolerate a policy reversal motivated by a large‐scale crisis, providing partial support for H2.

Next, we examine whether respondents penalize a party that fails to adapt its position despite new scientific evidence or a crisis, as predicted by H4. It should be noted that our analysis for H4 deviates slightly from our pre‐registered plan, as we compare consistency despite evidence with the change treatment group corresponding to each scenario, rather than the control group. Specifically, we compare consistency despite crisis to change because of crisis and consistency despite science to change because of science. By doing so, we compare the consistency scenarios to the relevant counterfactual. Our results for the Covid experiment are presented in Figure 4. Contrary to our expectations, our respondents valued positional consistency despite scientific evidence and a crisis. More specifically, respondents were about 0.25 scale point more likely to vote for the party if it stayed consistent (p

![]() $<$ 0.001).

$<$ 0.001).

Figure 4. Consistency despite evidence: Covid.

Finally, Figure 5 shows the results of our consistency hypothesis in the case of the nuclear phase‐out experiment. As the figure shows, we find support for H4 only in the crisis scenario, where the party maintains its previous position despite the ongoing energy crisis. In this case, respondents are less likely to vote for the party that stays consistent, compared to the scenario where the party decided to change. However, we do not find a similar effect when the party maintains its position despite new scientific evidence, as demonstrated in the upper half of the same figure.

Figure 5. Consistency despite evidence: Nuclear phase‐out.

In line with our pre‐analysis plan, we conducted a robustness check by employing our manipulation check question. Following the treatments, our respondents were asked a factual question about the treatments they received to indicate whether they comprehended the substance of our experimental treatments. To check if the results are robust, we re‐estimate our treatment effects by focusing only on respondents who passed the manipulation check. A full report of this analysis can be found in the online Appendix. Although it is bad practice to exclude subjects who failed the manipulation check (Aronow et al., Reference Aronow, Baron and Pinson2019; Varaine, Reference Varaine2022), it is still useful to see if our results stand robust by focusing only on a subset of our respondents who paid close attention to the treatments. The findings indicate that our results remain the same with only minor changes which we highlight.

Alternative explanations

The findings so far have shown that our respondents reacted by and large similarly to all types of policy U‐turns: they almost generally punish political parties that commit policy reversals, and they seem to not care much about why the change happened in the first place. What other factors could potentially explain the respondents' behaviour, if they are not taking into account the reasons behind the party's change in course? To further understand the behaviour of our respondents, we explore two possible explanations.

Proximity

First, it is possible that respondents primarily evaluated the behaviour of the party based on their own issue preferences, rewarding the party when it moves towards their position and punishing it otherwise, regardless of the reason for the change. Indeed, past work suggested that the ‘direction of change’ matters a great deal for voter evaluations (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Fernandez‐Vazquez & Theodoridis, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Theodoridis2020; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). This behaviour indicates a type of ‘issue‐motivated reasoning’ (Mullinix, Reference Mullinix2016) whereby voters interpret party actions in terms of existing policy preferences (see also Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Lodge & Taber, Reference Lodge and Taber2013). But would the same conclusion hold under the assumption that voters observe the motivation for change?

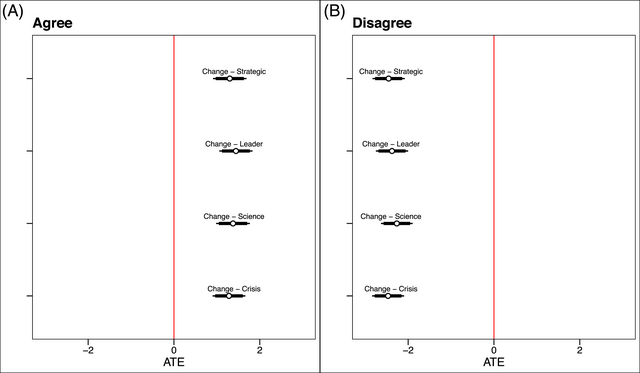

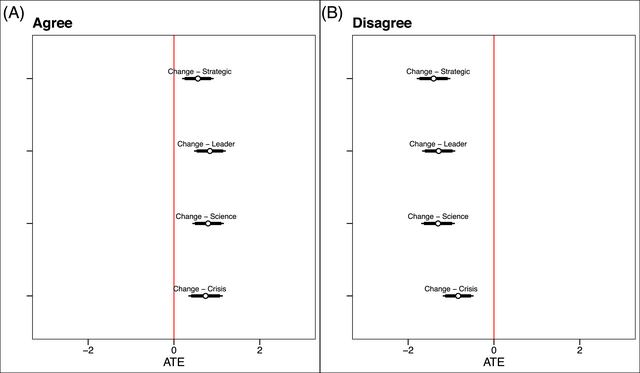

To answer this question, we present Figures 6 and 7, which show the overall effect when the party changes to agree or disagree with the voter in its new position, departing from its previous position. The figures show that policy changes were evaluated positively compared to the control group when the party moved towards a position congruent with that of the respondent. Conversely, the political party was punished when it moved to a position contradicting the respondent's. This pattern suggests that voters evaluate party behaviour egoistically, based on their own issue preferences rather than the rationale behind the party's behaviour. Notably, this pattern holds for all treatment conditions, demonstrating that voters prioritize positional proximity over the reasoning behind policy U‐turns.

Figure 6. The impact of proximity: Covid.

Figure 7. The impact of proximity: Nukes.

The role of trust

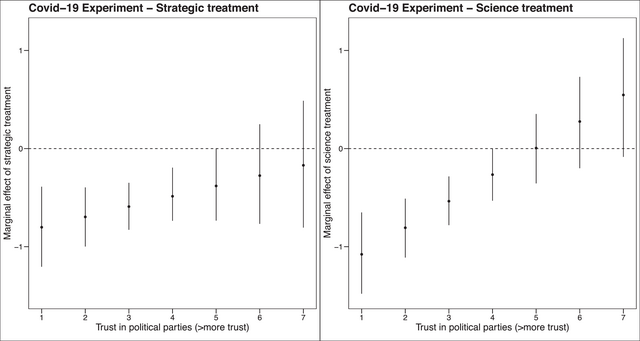

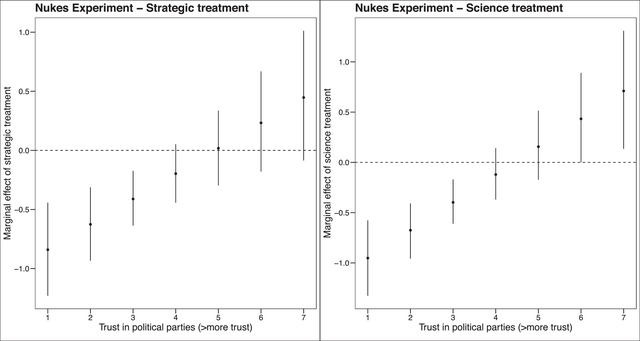

As a second explanation, we explore the role of political trust. Given the increasing scepticism of voters towards politicians (Citrin & Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018), they may regard all types of policy change as opportunistic. Past research demonstrated that political trust is consequential for a broad range of outcomes, such as abiding by laws and regulations (Krupenkin, Reference Krupenkin2021; Marien & Hooghe, Reference Marien and Hooghe2011). Nevertheless, it is still unknown how levels of trust affect voter evaluations of repositioning. We hypothesize that evaluations of the party would correlate with levels of political trust. To evaluate this assumption, Figures 8 and 9 present the marginal effect of strategic and principled policy U‐turns on the Y‐axis across levels of political trust on the X‐axis. The figures indicate a strong moderating effect regarding respondents' self‐reported levels of political trust: While policy reversals at lower levels of trust resulted in negative evaluations, this negative tendency gradually disappears with higher levels of political trust. Eventually, position switching is completely tolerated at the highest levels of trust. Surprisingly, the effect of repositioning becomes positive even when respondents are primed with strategic office‐seeking behaviour as shown in Figure 9. This trend suggests the importance of political trust in understanding voter evaluations of positional shifts and party behaviour more generally.

Figure 8. The moderating effect of political trust: Covid.

Figure 9. The moderating effect of political trust: Nukes.

Discussion and conclusion

The current study investigated the question of how voters evaluate policy U‐turns. To do so, we connected the causes of change to their consequences and investigated whether voters evaluate party behaviour differently based on the motivations for policy change. We proposed two classes of policy U‐turns: principled and strategic and anticipated our respondents to tolerate the former compared to the latter. Nonetheless, our findings were surprising, revealing that voters generally punish all types of policy switching, regardless of whether it is motivated by strategic or principled considerations. These surprising results indicate that voters have a low tolerance for inconsistency and expect parties to uphold their campaign promises and ideological commitments. They also highlight a paradox in representative democracies. Given that circumstances change, such as due to crises or expert advice, politicians have to be careful while communicating their behaviour to the public.

In addition, we explored the role of political trust and proximity in voter evaluations and found that voters tend to evaluate parties based on whether they agree or disagree with their preferences. More importantly, our analysis demonstrated strong evidence that political trust can alleviate the negative consequences of policy switching. These findings indicate that voters' negative reactions to position switching might be an epiphenomenon of larger issues, such as the lack of trust in political parties and politicians. Lastly, this paper opens new avenues for future research: beyond trust and proximity, it is worthwhile to investigate when will voters tolerate evidence‐backed party behaviour, potentially incorporating the role of partisanship which our study did not cover.

Why is self‐interested behaviour by a party dangerous for voters? Downs (Reference Downs1957) argues that parties' self‐interest urges them to follow public opinion, as indicated by the median voter theorem. Nonetheless, we contend that parties' self‐interest is dangerous for voters since it entails other forms that might harm the public good, such as shirking (Przeworski et al., Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999), obfuscation (Downs, Reference Downs1957) or bait‐and‐switch (Stokes, Reference Stokes1999). Similarly, why can strategic, political policy reversals engender more uncertainty relative to the principled reversals? Strategic reversals are more likely to prioritize short‐term political goals over long‐term policy stability. This focus on immediate political gains can result in frequent shifts in policy direction, which may not align with the long‐term needs and preferences of the electorate. Voters may feel uncertain about the government's ability to provide stable and consistent governance if the long‐term challenges are neglected, and decision‐making is more focused on collecting short‐term dividends.

Our study is by no means flawless. It is worth mentioning that our work relies on two assumptions, which might not be achieved under all circumstances. First, our hypotheses assume that voters observe party rhetoric, an assumption that still engenders debates in the literature (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2011; Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2014). Second, we assume that voters are aware of the background of party change and understand why the change came about. Although parties, in reality, will obviously refrain from explaining their behaviour in strategic or opportunistic terms, past research shows that such perceptions could reach the voter in a variety of ways, such as message distortion or counter‐explanations from other competitors (Robison, Reference Robison2022; Somer‐Topcu & Tavits, Reference Somer‐Topcu and Tavits2023), the media or unelected political groups (Gooch, Reference Gooch2022) or from criticism and political attacks, known as negative campaigning (Nai & Walter, Reference Nai and Walter2015), among other sources that could have a significant influence on voters' perceptions and evaluations. For example, Levendusky and Horowitz (Reference Levendusky and Horowitz2012) show that the reactions of political elites (such as congressmen) to the president's flip‐flop affect the extent to which voters will punish the president's behaviour. Other research shows similar effects of counter‐explanations when it comes from non‐elected groups, such as the media, voters, etc. (Robison, Reference Robison2022)

Another limitation in our experimental design relates to the counterfactual scenarios for the two ‘political’ sources of U‐turns: the strategic and leadership‐motivated changes. While we tested the effect of consistency despite evidence or crisis, we did not test for consistency despite office‐seeking motives or leadership turnover. Nonetheless, the main reason why we did not include these two scenarios, in line with the evidence‐based changes, is that we sought to evaluate how voters evaluate consistency despite pressing and exogenous changes in the environment urging a change. Our expectation regarding the other two factors would remain that consistency will be valued compared to changes. Second, our reliance on hypothetical parties, in addition to its pros and cons which we discussed earlier, also hindered studying important mechanisms related to partisanship and motivated reasoning. It would be worthwhile for future research to investigate if the motivations we hypothesize matter differently when they come from real parties the respondents may identify with.

Furthermore, it is possible that contextual factors, such as federalism and corresponding political veto players, interact with voter evaluations of policy reversals. Although such institutional characteristics are expected to play a more significant role with regard to the actual consequences of policy reversals, it is still possible that the highly sophisticated voters take such institutional factors in mind while evaluating the possible consequences of policy reversals. This question, namely how constitutional structure and voter reactions interact, is still unaddressed, and, therefore, could be a possible interesting avenue for future research.

Lastly, while our analysis failed to find significant differences based on the motives for the change, this trend could likely emerge in cases when voters fail to observe the motivations behind the change or when they do not perceive the strategic and principled motivations as such. In our experiments, this could arise, for example, if the treatments failed to treat respondents as they were intended. Nonetheless, the fact that our robustness check, which only utilizes manipulation check passers, uncovers very similar results suggests that it is unlikely to be the case. Another factor that might interact with our findings is that the abrupt full U‐turn that we prime our respondents with might have affected their responses relative to the motive for change. While we remain agnostic as to how our results might change if the U‐turn was partial or gradual, we would expect similar findings, yet possibly less pronounced in terms of effect magnitude. Doherty et al. (Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016) show that the passage of time makes the effect of repositioning less negative. One might expect similar differences in terms of the distance between positions at time

![]() $\tau _1$ and

$\tau _1$ and

![]() $\tau _2$.

$\tau _2$.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the winter retreat participants of the European Politics Group, attendees of the Castasegna Workshop, and three anonymous reviewers for excellent comments on earlier versions of this paper. We acknowledge financial support from the Center for Comparative and International Studies (CIS funding).

Conflict of interests statement

There are no conflict of interests to declare.

Ethics approval statement

This study has been approved by the ETH Ethics Committee (EK‐2022‐N‐183).

Funding information

We acknowledge financial support from the Center for Comparative and International Studies (CIS funding).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure A1: Main variables: Ideological positions

Figure A2: The Distribution of demographic variables

Table A1: Balance test

Figure A3: Balance test

Table A2: Findings for manipulation check: switching treatments

Figure A4: ATE for manipulation passers and all respondents

Table A3: Findings for manipulation check: consistency treatments

Figure A5: ATE for manipulation passers and all respondents

Figure A6: Political sophistication/interest

Figure A7: Political sophistication/interest

Figure A8: Political sophistication/interest

Figure A9: Reported policy‐specific knowledge: Covid

Figure A10: Reported policy‐specific knowledge: Nukes

Figure A11: Treatment effect: Covid vax

Figure A12: Treatment effect: Phaseout plan

Figure A13: Perceived competence: Covid

Figure A14: Perceived competence: Nukes

Figure A15: Perceived predictability: Covid

Figure A16: Perceived predictability: Nukes

Figure A17: Perceived self‐interest: Covid

Figure A18: Perceived self‐interest: Nukes