With increasing life expectancy, more people are living with advanced cancer. Clinical depression in this group has a pooled prevalence of 16.5%.Reference Mitchell, Chan, Bhatti, Halton, Grassi and Johansen1 Depression, which is distinct from adjustment disorder, is associated with a negative impact on quality of life and, untreated, is a predictor of early death.Reference Lloyd-Williams, Shiels, Taylor and Dennis2 The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that people with advanced cancer are routinely screened and treated for depression.3 Antidepressants may be helpful, but they may worsen cancer symptoms or interact with chemotherapyReference Pitman, Suleman, Hyde and Hodgkiss4 and, given that people with advanced cancer face particular challenges, including life-threatening illness, symptom burden, and personal, family and practical problems, psychological interventions may be preferred. Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely evidenced psychological interventions for depression.Reference Price and Hotopf5 However, evidence of its effectiveness for treating depression in advanced cancer is limited and previous research has focused on those affected by specific tumour groups.Reference Mustafa, Carson-Stevens, Gillespie and Edwards6 The CanTalk study (trial registration number ISRCTN07622709) was a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of CBT delivered through NHS England's Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme compared with treatment as usual for reducing depressive symptoms in people with advanced cancer. The CBT was manual-based and context-specific for advanced cancer. The research, reported in detail in the full National Institute for Health Research report,Reference Serfaty, King, Nazareth, Moorey, Aspden and Tookman7 formed part of the UK's National Cancer Research Network (NCRN) clinical trials portfolio, registration number 10255. This paper reports on whether manualised IAPT-delivered CBT was more effective than treatment as usual in treating depressive symptoms in people with advanced cancer.

Method

Design

The CanTalk study was a multi-centre parallel-group single-(researcher)-blind RCT undertaken between 5 March 2012 and 30 November 2016. A summary of methods from the protocolReference Serfaty, King, Nazareth, Tookman, Wood and Gola8 is provided in this section.

Ethics and consent

We assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the London–Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee, reference 11/LO/0376. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient involvement

Cancer and mental health patients helped with: formulating the research, trial design, preparing materials, ethics, trial meetings, optimising recruitment, interpreting results and deciding how to distribute results.

Eligibility and screening

People with a diagnosis of cancer not amenable to curative treatment were screened for depression using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2).Reference Kroenke and Spitzer9 Participants were recruited from general practices, a hospice, and oncology departments in England; if positive (≥3 on the PHQ-2), they were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Diagnosis of advanced cancer; DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI);Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller10 sufficient understanding of English; eligible for treatment in an IAPT centre.

Exclusion criteria

Clinician-estimated survival <4 months; high suicide risk; receipt in past 2 months of a psychological intervention for depression recommended by NICE; alcohol dependence (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, AUDITReference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente and Grant11). We avoided recruiting in areas where oncology care included routine referral to CBT.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to CBT plus treatment as usual (TAU) or TAU alone, with a 1:1 ratio. The random allocation sequence was generated by PRIMENT, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) registered clinical trials unit, using a web-based system. Randomisation used permuted blocks with sizes of 4 or 6, stratified for antidepressant prescription (yes/no).

The intervention

TAU involved routine assessment and treatment, including care from general practitioners (GPs), clinical nurse specialists, oncologists and palliative care clinicians.

In CBT (plus TAU), IAPT therapists were trained to adapt their existing skills and use context-specific CBT according to the CanTalk study intervention manual. They provided up to 12 sessions of individual CBT delivered, usually weekly and within 3 months, either face to face or by telephone.

Context-specific CBT manual and training

A treatment manual informed by previous work (available from the corresponding author) was developed for the trial by members of the research team.Reference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente and Grant11 CBT therapists attended a 1-day course on how to use the manual and adapt their standard CBT work for people with advanced cancer. This included adapting techniques within the constraints of physical illness, working with realistic negative thoughts, dealing with fears about death and dying, and including carers in sessions where appropriate.

Delivery of CBT

Since 2008 a stepped-care approach for people with depression and anxiety disorders has been available in some areas of England through NHS England's IAPT programme, delivered through IAPT/well-being centres12 located in the community or in GP practices. Our study used only high-level (level 3) ‘high-intensity therapists’ with at least 2 years postgraduate diploma experience in CBT. IAPT therapists offer face-to-face evidence-based therapy for people with complex problems using an adaptation of CBT developed by Beck et al.Reference Beck13 High-intensity therapists are required to have at least a proficient level of delivery of therapy, judged by the Cognitive Therapy Scale-RevisedReference Blackburn, James, Milne and Baker14 (CTS-R).

Supervision

In our study, regular supervision, usually monthly, was provided by IAPT supervisors, reflecting routine IAPT practice. In addition, the therapists were offered the opportunity to contact members of the trial team (M.S., S.M. and K.M.) for specialist advice in CBT applied to cancer.

Study measures

Potential participants were screened by University College London (UCL) researchers, National Cancer Research Network support staff and GP practice nurses and followed up by UCL researchers and/or National Cancer Research Network support staff.

Screening measures

Before study entry, initial screening used the PHQ-2 (the first two questions of the PHQ-9Reference Kroenke and Spitzer9), a validated depression screening measure.

After assessment for eligibility, second screening used the MINI,Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller10 a short structured diagnostic interview, widely used in people with cancer.

Demographic and related information (baseline)

We recorded gender, date of birth, marital status, ethnicity, employment status, education, history of depression and cancer diagnosis.

Outcome measures

(a) Primary outcome (baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 weeks):

(i) the Beck Depression Inventory-IIReference Beck, Steer and Brown15 (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report measure, used previously in advanced cancer.Reference Laidlaw, Bennett, Dwivedi, Naito and Gruzelier16

(b) Secondary outcomes (baseline, 12 and 24 weeks):

(i) the Patient Health QuestionnaireReference Kroenke and Spitzer9 (PHQ-9), a validated nine-item screening tool measuring severity of depression;Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams17

(ii) EuroQol's EQ-5D,Reference Brooks18 a generic utility measure of quality of life across five domains;

(iii) Satisfaction with Care: we assessed overall care, continuity of care, supportive care, information needs and quality of communication (scored 0–10 towards higher satisfaction);Reference King, Jones, Richardson, Murad, Irving and Aslett19

(iv) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance StatusReference Oken, Creech, Tormey, Horton, Davis and McFadden20 (ECOG-PS), an observer-rated scale assessing physical functioning in people with cancer: 0, asymptomatic; 1, symptomatic, fully ambulatory; 2, symptomatic, in bed less than 50% of time; 3, symptomatic, in bed more than 50% of time; 4, 100% restricted to bed; 5, dead.

Measures of potential bias

(a) Antidepressant use (baseline, 12 and 24 weeks): we recorded any prescribed antidepressants.Reference Bollini, Pampallona, Tibaldi, Kupelnick and Munizza21

(b) Other psychological therapies (baseline, 12 and 24 weeks): we noted any psychological intervention reported by participants.

(c) Expectations of therapy (baseline): participants were asked to predict the degree to which they thought their mood would improve during the trial using a 10-point Likert scale (‘not at all’ to ‘completely’).

(d) Treatment preference (baseline): patients indicated their group preferences (CBT, TAU, no preference).

(e) Attrition (6, 12, 18 and 24 weeks): we recorded reasons for missing follow-up assessments.

Therapy-related measures

(a) Non-attendance for CBT: we recorded reasons for not attending therapy sessions.

(b) Competence and adherence to treatment:

(i) competence: an accredited member of the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies independently rated recordings of therapy using the Cognitive Therapy Scale-RevisedReference Blackburn, James, Milne and Baker14 (CTS-R); the recordings were a randomly selected sample of 1 in 10 therapy sessions, stratified by phase (early: sessions 1–4; mid: sessions 5–8; or late: sessions 9–12).

(ii) adherence to the CBT manual: therapists recorded the components of therapy they delivered using a Therapy Components Checklist (TCC; available from the corresponding author); the independent rater also completed this checklist.

Statistical considerations

We agreed an analysis plan before locking the database for analysis.

Power and sample size

The study was powered to detect the overall effect of treatment on depression as measured on the BDI-II over the 24-week follow-up period, assuming a difference between the TAU and CBT groups of three points when measured at 6 weeks, rising further to six points after 12 weeks and sustained at that level thereafter (i.e. at 18 and 24 weeks). We assumed a standard deviation of 12 for each individual BDI-II measurement, based on the BDI-II manual.Reference Beck, Steer and Brown15 We assumed a 70% follow-up rate after 6 weeks, decreasing to 65% at 12 weeks and 60% at 24 weeks.

The correlation between two successive BDI-II measures taken 6 weeks apart is obtained from the BDI-II manual, which reports a correlation of 0.93 for sessions 1 week apart.Reference Beck, Steer and Brown15 If we assume an autoregressive decay of order 1, our best estimate of the correlation between BDI-II measures at 6 weeks is 0.936 = 0.65.

Assuming the attrition rates and correlation reported above, then the sample size required to detect an overall difference between the groups, at 90% power and 5% significance, is 109 patients per arm (using a multilevel model adjusting for baseline BDI-II). To account for clustering by therapist, the sample size needs to be inflated by a factor of 1.10. (1 + (average cluster size − 1) × intraclass correlation coefficient). This is based on an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.02Reference Kessler, Lewis, Kaur, Wiles, King and Weich22 and an average of 6 patients per therapist post-intervention. We therefore intended to recruit 120 patients per arm.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis, conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, tested for an overall treatment effect on the BDI-II over the four follow-up points, using multilevel modelling allowing for repeated measurements with equal weighting for each time point. The model comprised three levels: (a) repeated measures; (b) individuals; and (c) therapists. Baseline BDI-II score and antidepressant prescribing (yes/no) were included as fixed effects. The model was fitted using a linear mixed-effects model assuming Gaussian error distribution. Normality assumptions were checked.

Supportive analyses repeated the primary analysis with modifications: (a) using clustering by IAPT service; (b) without clustering; (c) including baseline history of depression, EQ-5D score, duration of current depression and duration from primary diagnosis to baseline as fixed effects; and (d) conducting separate analyses for each follow-up.

The original analysisReference Serfaty, King, Nazareth, Tookman, Wood and Gola8 was modified to include a complier-average intention-to-treat (CAITT) analysis,Reference Sussman and Hayward23 which adjusts for adherence by generating a ‘per-session’ treatment effect. Clustering by therapist was ignored in the CAITT model, as there was no evidence of such a clustering effect in the main analysis and so the simpler model is more robust here.

To test for bias, we compared baseline scores between the groups on: (a) non-pharmacological treatment for depression; (b) group preference; and (c) expectations of improvement with CBT. To compare antidepressant doses, these were converted into equivalent fluoxetine doses.Reference Hayasaka, Purgato, Magni, Ogawa, Takeshima and Cipriani24

We included exploratory analysis of the interaction of treatment with (a) time, (b) marital status and (c) education.Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Shelton, Hollon, Amsterdam and Gallop25 This was done by adding the relevant interaction term into the primary analysis model.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Analysis of PHQ-9 and Satisfaction with Care scores mirrored the primary analysis. For the ECOG-PS a non-parametric comparison of change from baseline at each time point was made between groups.

A detailed analysis plan is available from the corresponding author on request.

Data sharing

The study's data-set is available from the corresponding author on request.

Results

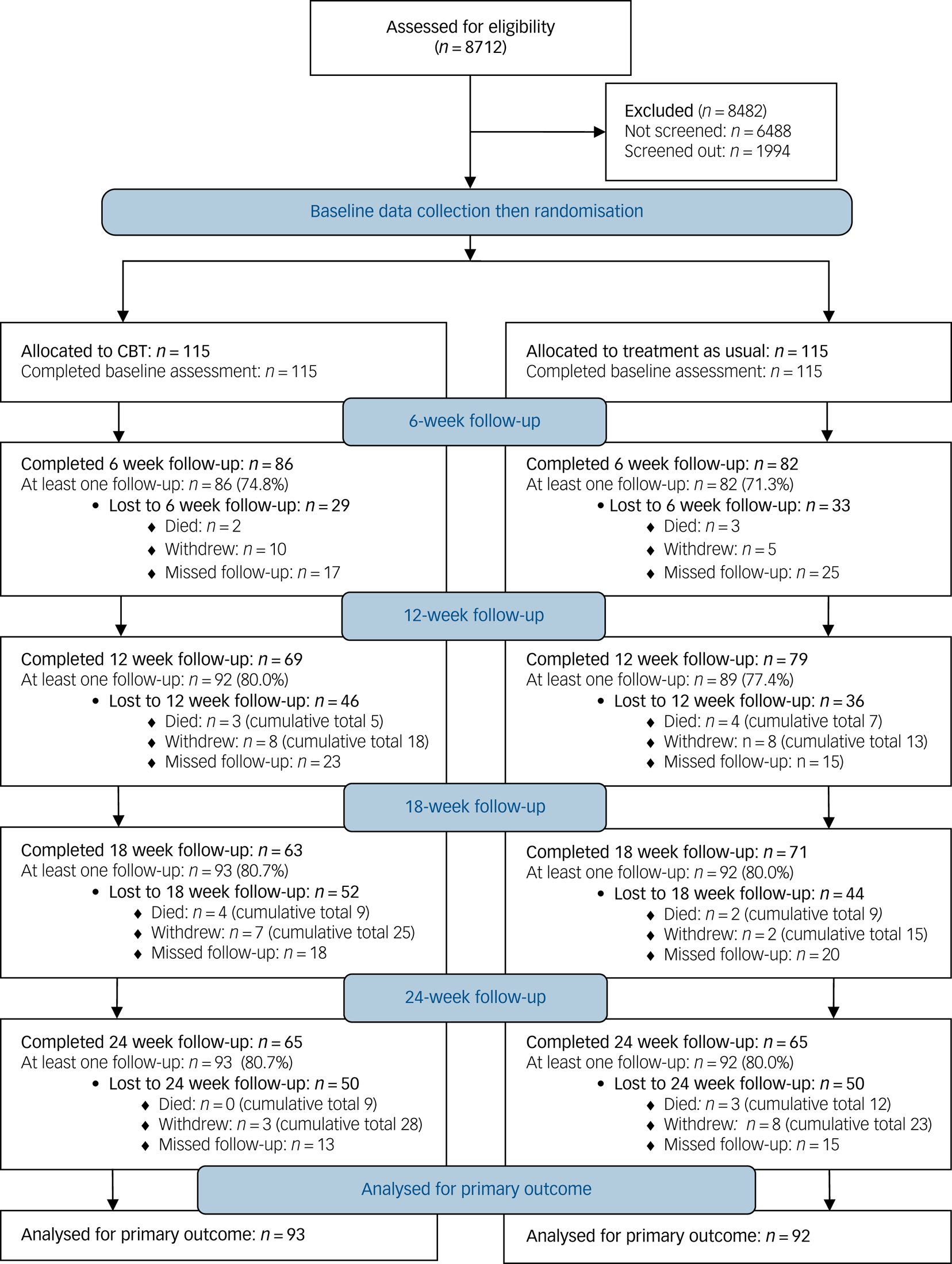

Of 8712 patients considered, 6488 were excluded (Fig. 1) for the following reasons (note that some had more than one reason for exclusion). In the pre-screening phase: IAPT unavailable, n = 2614; no advanced cancer, n = 1668; not screened (other reason), n = 1250; declined to participate, n = 1021. Post-screening: declined to participate, n = 1241; PHQ-2 score ≤3, n = 532; other reason, n = 221.

Fig. 1 CONSORT flow diagram for the trial.

Two hundred and thirty participants were randomised. At least one follow-up was available for 80% of participants; some were missed because of fluctuations in health (Fig. 1). Fifty-one reasons for withdrawing from the study were recorded; 18 (35.3%) were for ill health, and the remainder mixed, with no reason given for 11 (21.6%). Of the 71 reasons given for missed follow-ups in the CBT groups, 21 (29.2%) were due to physical health, 19 (26.4%) participants could not be contacted, and the remainder were mixed, with no reason given for 17 (23.6%).

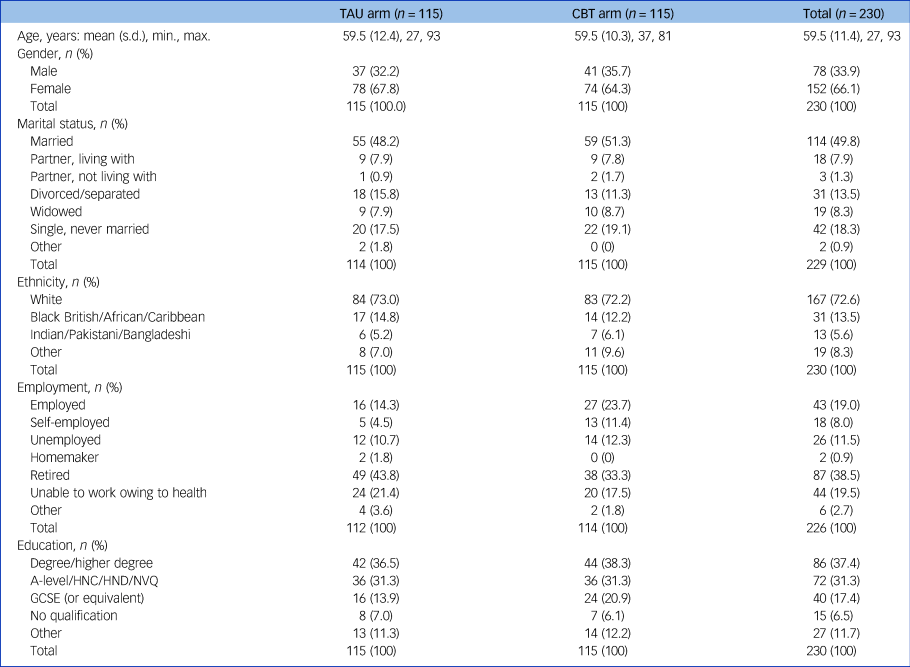

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics were similar across trial arms (Table 1). Recruitment sources were as follows: oncology departments (n = 196), hospices (n = 28) and GPs (n = 6). The cancer types were as follows: breast 31.3% (n = 72), haematological 18.6% (n = 43, comprising myeloma (n = 10), lymphoma (n = 17) and leukaemia (n = 5)), colon 12.6% (n = 29), lung 11.7% (n = 27), prostate 5.2% (n = 12), other 20.4% (n = 47).

Table 1 Baseline demographic characteristics by randomisation group

TAU, treatment as usual; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; HNC, Higher National Certificate; HND, Higher National Diploma; NVQ, National Vocational Qualification; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education.

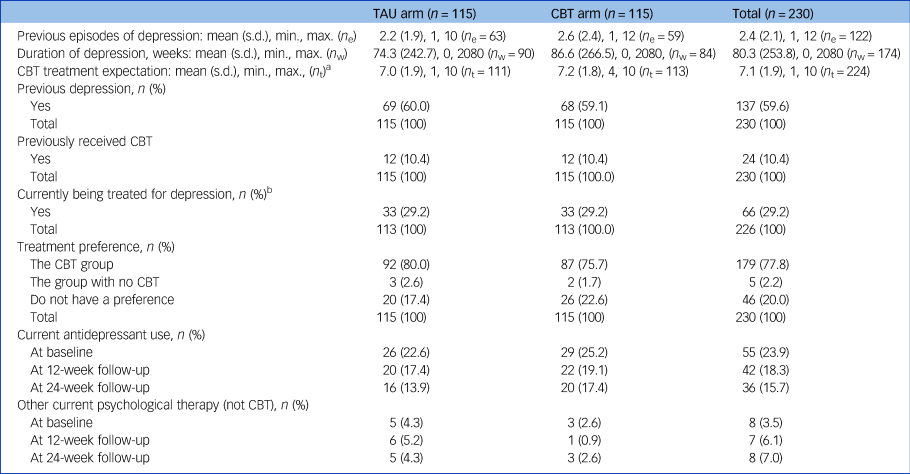

Diagnosis of depression, psychiatric history and treatment

The duration of current depression was skewed, with a median of 12 weeks; two people had been depressed for 40 years. The number of previous episodes of depression, the duration of the current depressive episode and antidepressant use were all similar between groups (Table 2).

Table 2 History, sources of bias and treatment of depression

TAU, treatment as usual; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; n e, number of participants reporting previous episodes; n w, number of participants reporting weeks of depression; n t, number of participants reporting treatment expectation.

a. Treatment expectation estimated improvement from ‘not at all’ (scored 0) to ‘very much improved’ (scored 10).

b. Includes prescribed medications, over-the-counter remedies and complementary therapies/self-help books to treat depression.

Delivery and receipt of CBT

Mean time from referral to first appointment was 29.4 days (s.d. = 26.7). Of a potential 1380 CBT sessions, 543 (39.3%) were taken up by 74/115 (64%) participants randomised to CBT. Mean number of sessions received was 4.7 (s.d. = 4.9); 41 people (35.6%) had no sessions. Thirty-two sessions (5.9%) were delivered by telephone. We rated for quality 55 sessions (28% of recorded sessions), 1 in 10 of sessions delivered. Mean CTS-R score was 47.6 (s.d. = 13.8), which was at the upper end of the ‘proficient’ range. Cognitive techniques were used in 57% of assessed sessions, behavioural techniques in 37% and topics specific to cancer in 70%.

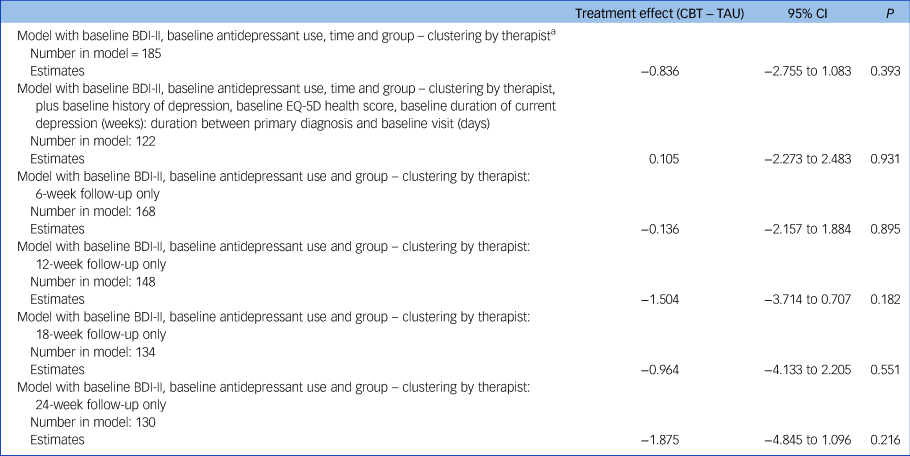

Main outcome

BDI-II scores at baseline and follow-up are provided in supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.207. The primary analysis of CBT (n = 93) v. TAU (n = 92) indicated that there was no benefit from CBT with time, adjusted for therapist clustering, antidepressant use or educational level (Table 3).

Table 3 BDI-II treatment effect adjusted for potential predictors of outcome

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; TAU, treatment as usual.

a. The pre-determined primary analysis for the trial.

Additional analyses found no evidence of clustering (at therapist or IAPT level) on the primary outcome and so these results are not given.

CAITT analysis

A total of 153 individuals were included in the CAITT model (those with relevant data (for the control and intervention groups) and with number of CBT sessions available (for the intervention group)). Assuming a linear relationship between number of sessions and change in outcome, the estimated per-session effect on the BDI-II was −0.295 (95% CI −0.760 to 0.170; P = 0.213). Thus, every CBT session would be expected to decrease the total BDI-II score by 0.3 points.

Exploratory analysis

There was an improvement in BDI-II of around five points for both groups at 6 months. People who were widowed, separated or divorced and who did not receive CBT continued with depressive symptoms (treatment effect −7.21, 95% CI −11.15 to −3.28; P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4 BDI-II Total scores by time point, marital status and level of education

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; TAU, treatment as usual.

Secondary outcomes

Baseline scores for secondary outcomes were similar in both trial arms (supplementary Table 2). There were no significant between-group differences at 12 and 24 weeks. The ECOG-PS suggested that, at baseline, 19.6% of participants (n = 45) were fully active, 42.2% (n = 97) had restricted movement, 27.4% (n = 63) were ambulatory, 10.9% (n = 25) had limited movement and 0% (n = 0) were disabled. Both groups were similar on the ECOG-PS at baseline. Non-parametric analysis of the change in ECOG-PS scores found no significant difference between groups at 12 or 24 weeks.

Discussion

In this trial, we compared CBT (plus TAU) delivered by IAPT therapists for the treatment of depression in people with advanced cancer with TAU alone. No benefit of CBT was found, and the per-session effect of CBT was too small to scale up to a clinically significant change even if the full 12 sessions were delivered. CAITT analysis found a non-significant change in BDI-II depression scores with CBT of 0.3 points per therapy session, which would equate to a 3.6-point change over 12 sessions. This is well below the 6-point change generally regarded as the minimum clinically important change on this scale. An exploratory analysis suggested that CBT for people widowed, separated or divorced was helpful. There were no significant between-group differences for secondary outcomes. The benefits of CBT for people with advanced cancer had been previously unclear because of underpowered trials, poor diagnosis and measurement of depression, lack of detail about interventions and concerns about generalisability.

Integrative collaborative-care approaches have previously been demonstrated to be effective in treating depression in poor-prognosis cancer.Reference Walker, Hansen, Martin, Symeonides, Gourley and Wall26 Such integrative approaches, in which cancer nurses and psychiatrists collaborate with primary care physicians, may be more appropriate for treating depression in this population than referral to IAPT services.

Clinical effectiveness and trial power

Our achieved power was sufficient to detect a 3-point change on the BDI-II. Even if our treatment effect of 0.84 change on the BDI-II were statistically significant, it is not clinically important. Although a recent study found a statistically significant benefit for psychotherapy,Reference Rodin, Lo, Rydall, Shnall, Malfitano and Chiu27 the change of 1.29 points on the PHQ-9 is of questionable clinical significance given accepted standards.Reference Kroenke28 Indeed, the beneficial effects of CBT for depression may be overestimatedReference Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer and Dobson29 and the benefit of psychosocial therapies,Reference Mustafa, Carson-Stevens, Gillespie and Edwards6 including CBT,Reference Savard, Simard, Giguère, Ivers, Morin and Maunsell30 for depression in advanced breast cancer is questionable. Our trial does not support CBT for depression in a wide range of cancers.

Diagnosing and measuring depression in advanced cancer

The MINI has been widely used to diagnose depression in cancer. However, in people with life-limiting physical illnesses it may be difficult to distinguish depressive disorder from an adjustment disorder with a prolonged depressive reaction (ICD-10 code F43.21). As the mean duration of depression was 1.4 years and no one had symptoms lasting less than 4 weeks, it is unlikely that our findings were accounted for by adjustment disorder. The BDI-II is widely used for measuring depression in advanced cancer.Reference Laidlaw, Bennett, Dwivedi, Naito and Gruzelier16,Reference Savard, Simard, Giguère, Ivers, Morin and Maunsell30,Reference Moorey, Cort, Kapari, Monroe, Hansford and Mannix31 Its cognitive components mitigate the problem of mislabelling physical symptoms that can occur with somato-affective components.

CBT as an intervention

A recent meta-analysisReference Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer and Dobson29 suggested that physical illness does not affect the outcomes of psychological treatments, but these data were not specific to a population with advanced cancer. With the exception of one underpowered study,Reference Savard, Simard, Giguère, Ivers, Morin and Maunsell30 previous work in a palliative care populationReference Moorey, Cort, Kapari, Monroe, Hansford and Mannix31 and a population with metastatic breast cancerReference Mustafa, Carson-Stevens, Gillespie and Edwards6 does not support the use of CBT for depression in advanced cancer. Our clinical experience was that physically ill people had difficulty in managing the demands of CBT.Reference Hassan, Bennett and Serfaty32

Delivery of CBT

Time from referral to receiving therapy (mean 29.4 days) was shorter than in typical IAPT services, where 75% of referrals are seen within 42 days.33 Our qualitative interviews confirmed that a small number were delayed because of physical problems.Reference Hassan, Bennett and Serfaty32 Our trial aimed to test effectiveness, rather than efficacy of CBT. Sixty-four per cent (74/115) took up at least one CBT session. The mean number of sessions was 4.7. This is similar to therapy uptake for general IAPT practice (70%) and some improvement is observed after two therapy sessions.Reference Glover, Webb and Evison34 Our CTS-R ratings suggest delivery of good-quality CBT, adherence to the manual, and a balance of cognitive and behavioural techniques and cancer-related issues.

Therapists in the present study described the experience of working with this population as positive, although they perceived the rigidity of IAPT policies as problematic when treating this population.Reference Hassan, Bennett and Serfaty32 Therapists also emphasised the need for specialist supervision when delivering therapy to people with advanced cancer.Reference Hassan, Bennett and Serfaty32

Effect of bias

The BDI-II is self-report and this should minimise researcher bias. Differential attrition may bias outcome; however, retention of participants was similar between the trial arms.

Limitations

A large number of patients (8712) had to be considered to recruit 230 into this trial. Although many were excluded because they did not have advanced cancer or depression, others were excluded owing to lack of access to participating IAPT centres, and a substantial number also declined to participate in the study. The majority (two-thirds) of participants were female, which may raise concerns about generalisability of the findings, as men are more likely to develop and die from cancer. However, depression is more common in women, suggesting that our sample is representative of depression in the population with a range of advanced cancers. Uptake of therapy was limited, with only 64% of those randomised to the CBT group receiving treatment, and the mean number of sessions taken was 4.7 (out of a possible 12). Although this may have reduced the overall treatment effect, the CAITT analyses indicated that the per-session effect was insufficient to provide a clinically meaningful change, even if all 12 sessions were taken up. TAU could not be standardised and we could not preclude it including a psychosocial intervention. However, very few participants in the TAU group reported receiving any psychological intervention and none reported receiving CBT. Lastly, diagnosing depression can be problematic in people with cancer, where symptoms of the disease and treatment can overlap with symptoms of depression; although this cannot be fully mitigated, we chose the BDI-II as the primary outcome measure, as it has been validated and widely used in trials involving people with cancer.

Implications of findings

CBT in advanced cancer may be delivered in three ways: CBT specialists may be trained to apply existing skills to cancer-specific problems; cancer specialists may be trained in CBT skills; specialist CBT therapists may be imbedded in a cancer service. IAPT is expanding to treat long-term medical conditions. This research suggests that delivering CBT in this context for advanced/incurable cancer, rather than early curable disease, is not effective. Training clinical nurse specialists in a palliative care service to use CBT techniques is not effective for depressive symptoms.Reference Moorey, Cort, Kapari, Monroe, Hansford and Mannix31 Embedding CBT therapists within cancer and palliative care teams requires evaluation. Integrated collaborative care, which includes elements of CBT, has been shown to be beneficial for depression in lung cancer.Reference Walker, Hansen, Martin, Symeonides, Gourley and Wall26 Testing this approach in other tumour groups may offer greater promise than embedding a CBT therapist in a palliative care team. Although under a quarter of people in this trial were prescribed an antidepressant, evidence for their use for depression in people with cancer remains to be evaluated.Reference Ostuzzi, Matcham, Dauchy, Barbui and Hotopf35 The long duration of depression observed in this trial (mean 80 weeks) suggests that in people with advanced cancer, depression may either be missed (71% of participants in this trial were not receiving treatment for depression) or be unresponsive to treatment (in the 29% receiving treatment).

This trial was not powered to examine the observed benefit of CBT for depressive symptoms in participants who were widowed, separated or divorced. However, these are known moderators of response to CBT in adults.Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Shelton, Hollon, Amsterdam and Gallop25 We postulate that isolated, bereaved or separated participants may have benefited from the non-specific components of CBT (e.g. having someone friendly to talk to).

Summary

A meta-analysisReference Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer and Dobson29 suggested that the effectiveness of CBT for depression in general may be overestimated, possibly owing to publication bias, small sample size and a lack of suitable control groups. Although IAPT practitioners can be trained to deliver CBT to people with advanced cancer, our results suggest that resources for a relatively costly therapy such as IAPT-delivered CBT should not be considered as a first-line treatment for depression in advanced cancer. Indeed, these findings raise important questions about the need to further evaluate the use of IAPT for people with comorbid severe illness.

Funding

This work was supported by the UK's National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme (grant number 09/33/02, awarded to M.S.). This report presents independent research commissioned by the NIHR. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR HTA programme.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who kindly took part in the study; the principle investigators in all participating IAPT centres and oncology clinics, the therapists who treated participants as part of the trial, and all oncology and hospice staff who helped to screen and recruit participants for the study; Janet St John-Austen, a patient representative who contributed towards planning of the project, preparing patient materials and the interpretation of the results; the members of the Trial Steering Committee – Mathew Hotopf (Chair), David Ekers, Sarah Purdy, Janet St John-Austen, Sarah White, Louise Jones, Marc Serfaty and Vari Drennan; the members of the Trial Data Monitoring Committee – John Norrie (Chair), Nicola Wiles, Galina Velikova and Paddy Stone; the researchers who collected data for the trial – Brendan Hore, Nicola White, Georgina Forden, Deborah Haworth, Cate Barlow, Kirsty Bennett, Suzan Hassan, Ekaterina Cooper and Andrea Beetison; Terrie Fiawoo, who helped to coordinate the trial; Steve Pilling for helping with IAPT service involvement; Baptiste Laurent, who helped with the statistical design; Marc Griffin for conducting the statistical analysis; Faye Gishen for overseeing the trial and recruitment of patients in the Marie Curie Hospice Hampstead; and Liz Court for the supervision and support of trial researchers.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.207.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.