Introduction

Participation in elections has been consistently falling in several countries around the world (Kostelka, Reference Kostelka2017). While much attention has been devoted to trying to understand the sources of falling turnout rates, one clear observation is that young people are particularly less likely to vote (e.g., Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004; Gallego, Reference Gallego2009; Holbein & Hillygus, Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020), and generational replacement has been an important component of falling turnout rates (Kostelka & Blais, Reference Kostelka and Blais2021). The big question is why are young citizens abstaining more from electoral participation?

This paper argues that an important part of the answer lies in the perennial state of under‐representation of young people in politics. Be it due to formal minimal age requirements for holding elected office, electoral institutions favouring incumbents, or nomination practices by parties prioritizing tenure and experience, people below 35 are under‐represented by a factor of 3 in parliaments around the world (Sundström & Stockemer, Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021). This is larger than, for example, the under‐representation of women, who are 50 per cent of the population but comprise around a quarter of members of parliament globally (Sundström & Stockemer, Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021).

Research has historically highlighted the role of descriptive representation, meaning having representatives who ‘look like’ the represented (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967), for political attitudes and behaviour (Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp2004). While most studies have focused on gender (e.g., Carreras, Reference Carreras2017; Stokes‐Brown & Dolan, Reference Stokes‐Brown and Dolan2010; Wolak, Reference Wolak2020), ethnicity (e.g. Keele & White, Reference Keele and White2019; Martin, Reference Martin2016; Philpot & Walton, Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010) and more recently people with disabilities (Reher, Reference Reher2020), researchers have now also turned their attention towards how age may factor into a multidimensional model of representation and participation (Sundström & Stockemer, Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021; Stockemer & Sundström, Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018). It is natural to expect that, as young people look at politics and do not see themselves represented, they might tune off from parties and electoral politics (Blais & Rubenson, Reference Blais and Rubenson2013; Cammaerts et al., Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014), rather preferring non‐electoral forms of political participation (Henn & Foard, Reference Henn and Foard2012).

I test this argument with data from all modules of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES, 2024), spanning 223 national election surveys from 1996 to 2021 in 58 countries, with a final total of 308,630 participants in the analysis. These elections accounted for a total of 980 unique party leaders or presidential candidates. In all surveys, respondents are asked to rate all relevant parties on a like–dislike scale. In this paper, I focus on the party each respondent identified as the one they like the most and look at the age of the party leader/presidential candidate at the election time. The main hypothesis is that younger respondents are significantly more likely to vote if their favourite party has a younger leader or candidate than an older one.

Results confirm this expectation: in general, people below 30 are around 2 percentage points more likely to turn out if their preferred party has a 39‐year‐old as leader instead of a 70‐year‐old. This gap is also increasing over time and reaches over 4 percentage points in 2021. Further analyses also show that the mechanism driving the results appears to be that younger leaders increase democratic satisfaction and political efficacy among young citizens, both of which are well‐known correlates of turnout. These results have implications for understanding an emerging cleavage based on generational conflict and to better understand how parties can mobilize their young sympathizers.

Youth representation and participation

Young people have less political representation than their share of the population in virtually every country. According to Sundström and Stockemer (Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021), the political presence of citizens below 35 is on average one‐third of their proportion in the population across several countries. For those below 40, it is one in two – which is about the same as the under‐representation of women in politics around the world (Sundström & Stockemer, Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021). Different factors may lead to this scenario. First, several countries have minimum age requirements for citizens to run for office, which are higher than the minimum age requirements to vote. In several presidential democracies in the Americas, the president cannot be younger than 35 while members of parliament often have to be at least 21 or 25 – even though minimum voting ages generally range from 16 to 18. These limits, however, are not the only reason for the mismatch between young people's share in the population and their political representation. The selection process within parties also plays a role whereby party members and elites tend to prefer experience and tenure when selecting candidates (Magni‐Berton & Panel, Reference Magni‐Berton and Panel2021; Rehmert, Reference Rehmert2022), while institutional factors such as the electoral system may also contribute to keep younger politicians away from office for longer (Stockemer & Sundström, Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018).

This is partially puzzling because voters do not seem to prefer older candidates. In a meta‐analysis of conjoint experiments with fictitious candidates that included age as an attribute, Eshima and Smith (Reference Eshima and Smith2022) find that older hypothetical candidates are consistently less favoured by respondents. Roberts and Wolak (Reference Roberts and Wolak2023), in their turn, find that American voters rate younger members of Congress more favourably than older ones. Belschner (Reference Belschner2023) finds that younger candidates are also viewed more favourably in Ireland, though for young female candidates this positive effect is cancelled out by voters' negative evaluations of women. Citizens consistently appear to prefer younger politicians, even though older ones keep getting elected and re‐elected. This is similar to the fact that, in conjoint experiments across countries, voters express a higher preference for female candidates (Schwarz & Coppock, Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022; Wäckerle, Reference Wäckerle2023), but men are still over‐represented in actual parliaments – in large part because of being more likely to run in the first place (Ammassari et al., Reference Ammassari, McDonnell and Valbruzzi2023; Thomsen & King, Reference Thomsen and King2020).

Since the under‐representation does not come from the electorate's preference for older politicians, it may be expected that it affects people's perceptions of the political system and its functioning. Young people who do not see themselves represented in politics have lower political efficacy due to a justified perception that the political system does not integrate their voices (Cammaerts et al., Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014). For this reason, they abstain more often from electoral politics (Blais & Rubenson, Reference Blais and Rubenson2013), given efficacy's role as one of the main drivers of voting (Norris, Reference Norris2004). This does not necessarily mean less interest in politics, however, but rather that young people prefer other types of political participation, more effective and in tune with their preferences and priorities, explaining the widespread low youth turnout (Binder et al., Reference Binder, Heiss, Matthes and Sander2021; Cammaerts et al., Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014).

Research into other under‐represented groups, such as women, and ethnic and sexual minorities, highlights the importance of role models in promoting efficacy and participation among citizens of those groups. Visible female politicians serve as role models to women and young girls, who become more interested and active in politics (Campbell & Wolbrecht, Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Wolbrecht & Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007) and report more political efficacy (Costa & Wallace, Reference Costa and Wallace2021). This effect is particularly pronounced when women have higher visibility in politics, by being part of the cabinet (Liu & Banaszak, Reference Liu and Banaszak2017) or holding highly salient legislative or executive positions (Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Marshall and Mathews‐Schultz2015), with similar findings extending to minorities' participation (Everitt & Tremblay, Reference Everitt, Tremblay and Thompson2020; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010; Stokes‐Brown & Dolan, Reference Stokes‐Brown and Dolan2010).

It may sound controversial at first to put age‐based under‐representation at a similar theoretical status to that based on ethnicity or gender. There are good reasons, however, to do so. Recent research has found that younger citizens today do have ‘cohort consciousness' (Munger, Reference Munger2022; Ross & Rouse, Reference Ross and Rouse2022), meaning people identify as belonging to the same social group with a shared fate with others in their generation. The emergence of the Fridays for Future movement highlights how young people today voice their concerns about not being heard in politics as young people. Moreover, while belonging to other under‐represented groups might seem a more clear, ‘binary’ thing than age, the fact is that social group membership is often fuzzy for gender and ethnicity as well (e.g., Davenport, Reference Davenport2020).

There is a nascent literature on age‐based representation, and it points in a similar direction as that of other groups with regard to the mobilization potential of younger politicians and candidates. Pomante and Schraufnagel (Reference Pomante and Schraufnagel2015) first use an experiment to show that younger candidates make it more likely that younger voters turnout in the United States and then explore observational data from state‐level American elections to find that youth mobilization is higher where the gap in age between contestants is higher – that is, where there are younger candidates running. Looking at mobilization potential within parties, Webster and Pierce (Reference Webster and Pierce2019) find that people prefer to vote for members of their party who are closer to themselves in age, which is confirmed by Sevi (Reference Sevi2021) looking at CSES data from 51 countries, and finding that respondents do have more favourable ratings of party leaders who are closer to their own age (the opposite is found in Tunisia by Dobbs, Reference Dobbs2020, suggesting this age heuristic varies across contexts). Finally, Ferreira da Silva et al. (Reference Ferreira da Silva, Garzia and De Angelis2021) show that individual leaders’ characteristics have been getting more relevant for voters' turnout decisions in recent years, which confirms the relevance of looking at party leaders when trying to understand political behaviour.

Moreover, as Reher (Reference Reher2014) finds, non‐partisan voters are more likely to turn out if their policy priorities are reflected in the campaign, meaning when there is congruence between issues they find important and what is covered by those running. A large share of research has documented that young and older voters have different preferences and priorities, which is reflected by politicians. For example, older citizens favour investments in pensions at the expense of education (Brunner & Balsdon, Reference Brunner and Balsdon2004; Hess et al., Reference Hess, Nauman and Steinkopf2017), and older members of the US Congress are more likely to introduce legislation dealing with senior issues (Curry & Haydon, Reference Curry and Haydon2018). Across countries, young people are more supportive of immigration and multiculturalism (Abramson & Inglehart, Reference Abramson and Inglehart2009; Ross & Rouse, Reference Ross and Rouse2015) as well as feminism and LGBTQI+ rights (Ayoub & Garretson, Reference Ayoub and Garretson2017; Hansen & Dolan, Reference Hansen and Dolan2023; McEvoy, Reference McEvoy2016) than older citizens. A younger party leader, therefore, could also serve as a heuristic that the party is closer to younger respondents' priorities, increasing their likelihood of participation.

We should expect, therefore, that younger candidates are able to mobilize more young voters to turn out when they are aligned ideologically. More specifically, if a party has as their leader or leading candidate a younger politician instead of an older one, we may expect higher turnout by their young sympathizers, following the expectation of role models' effects on youth's political efficacy and voting intentions. This is the first hypothesis tested in this paper:

-

H1. Young citizens are more likely to turn out the younger the leading candidate is of their favourite party.

Regarding the last point made above, on policy congruence, it must be noted that the main difference in attitudes across age groups is likely on views about climate change, which have become defining features of younger generations' political identities (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Rouse and Mobley2019; Ross & Rouse, Reference Ross and Rouse2022). Being one of the greatest existential challenges of our times, whose worst effects are expected to come in the next decades, it is natural that young people are particularly attentive to this topic and blame older citizens for the policies that led to the current climate crisis (Munger, Reference Munger2022). These attitudes are further influenced by the emergence of the Fridays for Future movement, which is carried by young people demanding immediate measures to tackle climate change (Parth et al., Reference Parth, Weiss, Firat and Eberhardt2020).

These developments suggest that age‐based representation may be more important now than a few decades ago. Munger (Reference Munger2022) argues that younger cohorts (millennials and Generation Z) are more likely than people of other generations to consider their generational attachment as a political identity. The fact that some of the most important political issues for young people today are also topics in which there are large gaps in attitudes across age groups suggests that the mobilizing effect of younger politicians may be increasing in recent years as the age‐based cue may be more important for a young electorate who considers age‐based representation more relevant. Such an effect has been identified by Ferreira da Silva et al. (Reference Ferreira da Silva, Garzia and De Angelis2021) in a study of turnout decisions in 13 West European countries: the authors find that the age of leading candidates is related to turnout decisions by voters and that this relationship has been getting stronger in recent elections. Therefore, the second hypothesis tested in this paper is

-

H2. The mobilizing effect of leaders' age on turnout has been growing stronger over time.

Exploring mechanisms

A question that merits attention is what are the specific mechanisms connecting leaders' age to young respondents' turnout decisions. As mentioned earlier, prior research into under‐represented groups highlights the potential of descriptive representation impacting two known correlates of turnout: political efficacy and democratic satisfaction (e.g., Hadjar & Beck, Reference Hadjar and Beck2010). Political efficacy is often broken down into two components, internal and external (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Niemi and Silver1990). External efficacy refers to the extent someone believes that the political system is responsive to them and that they have an influence on the political process (Craig, Reference Craig1979; Craig et al., Reference Craig, Niemi and Silver1990).

Visible role models can increase minorities' perceptions that they can have a voice in politics. Reported levels of political efficacy are higher among minorities when there are more visible role models in power positions (Costa & Wallace, Reference Costa and Wallace2021; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Marshall and Mathews‐Schultz2015). For example, Ostfeld and Mutz (Reference Ostfeld and Mutz2021) find that, after the election of Barack Obama as president and the nomination of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, African‐Americans and Latinos became more likely to agree that the government is responsive to their interests, using questions on whether parties and elections make the government pay attention to what people think.

Low levels of external efficacy have been linked to lower youth political participation in different countries. Using different sources of data from various European countries, Cammaerts et al. (Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014) find that young people are not less interested in politics than older cohorts (the same is observed by Holbein & Hillygus, Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020), but they do report beliefs that mainstream parties and politics are not attentive or responsive to their voice, which is linked to their lower likelihood of voting. In a very different context, where young people make up a much larger portion of the population, Resnick and Casale (Reference Resnick and Casale2014) show that perceptions of the electoral system and efficacy influence lower youth turnout in 19 African countries, while Sperber et al. (Reference Sperber, Kaaba and McClendon2022) find experimentally that a message to increase efficacy among young people in Zambia has a larger impact on leading to higher turnout probability than messages of an obligation.

If the logic from other under‐represented groups applies, then visible descriptive representation with young prominent candidates and party leaders is expected to increase young citizens' sense of external efficacy, namely that their voice can be heard in politics and that their vote makes a difference. This would be one way through which leaders' age is related to youth turnout and gives the third hypothesis in this paper:

-

H3. Young citizens have higher feelings of external efficacy the younger the leading candidate is of their favourite party.

Finally, a closely related concept to external efficacy is satisfaction with the way democracy is working (Daoust & Nadeau, Reference Daoust and Nadeau2021; Magalhães, Reference Magalhães2016). Citizens who believe the government to be more responsive to their concerns would also be more satisfied with democracy in their country. Not only responsiveness beliefs but also actual congruence in priorities between citizens and elites have been found to increase democratic satisfaction (Reher, Reference Reher2015). Once again, drawing from research into women's representation, Schwindt‐Bayer (Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2010) finds that women have higher levels of democratic satisfaction when there are higher levels of women's political representation in Latin America. The final hypothesis, therefore, is

-

H4. Young citizens have higher satisfaction with democracy the younger the leading candidate is of their favourite party.

Data and measurement

To test the four hypotheses, I use data from all five modules of the CSES, spanning 223 national election surveys from 1996 to 2021 in 58 countries, with a total of 308,630 respondents.Footnote 1 The surveys are nationally representative and take place after the main national election in each country (parliamentary or presidential). The main dependent variable is turnout, a binary on whether the respondent reports to have cast a ballot in the recent national elections.Footnote 2

The main variable of interest for this study is the age of the leader of respondents' preferred parties. To start building it, I gather the list of party leaders or candidates for all parties in the study. In cases where the main election was presidential – for example, in presidential countries like the United States or Brazil, and in some semi‐presidential such as France – the leader is considered as the presidential candidate, who is most often the best known politician in each party. In parliamentary systems, the leader is the party leader who would become prime minister in case of an electoral victory.Footnote 3 In modules 1, 2, 4, and 5, the CSES itself provides the leaders' names, compiled by the teams of national experts. In some cases, parties have two leaders. There, the one picked is the one which would become PM, which is oftentimes indicated in the CSES data itself.Footnote 4 For election studies in module 3, where the dataset itself does not give the leaders' or candidates' names, those were collected manually from Wikipedia and Wikidata. Next, I collected the year of birth of all unique 980 party leaders and candidates for all parties mentioned in each election and calculated the leaders' ages at election time.

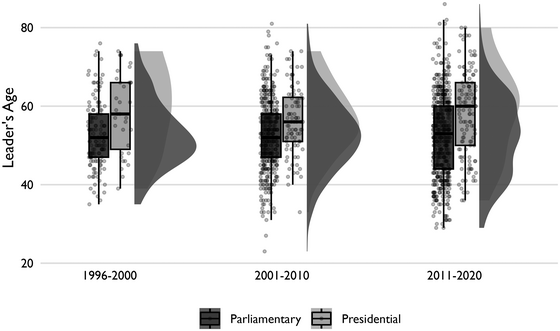

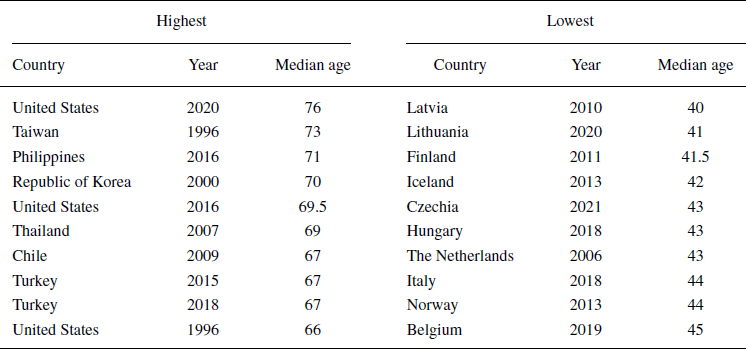

Figure 1 shows the distributions of leaders' ages for all elections, by decade and election type. It is clear that presidential candidates are consistently older than party leaders in parliamentary democracies. The median age of presidential candidates in the entire sample is 58, against the median party leader in parliamentary elections who is 52. Indeed, Table 1 shows the 10 elections with the highest median age among candidates and the 10 with the lowest. Among the lowest, all are parliamentary elections. Among the highest, seven are presidential. Top of the list is the 2020 American election between Donald J. Trump (74) and Joe Biden (78). The difference across periods, however, is not significant, indicating that, on average, leaders' age has not changed much in the last 25 years.

Figure 1. Party leaders' age over time by election type.

Table 1. Elections with the highest and lowest median age of leaders/candidates

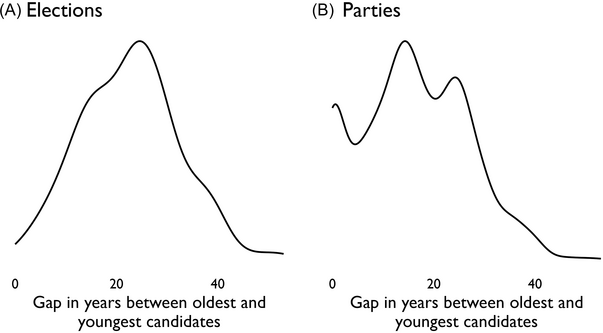

Figure 2 shows the distribution in the gap between the ages of the youngest and oldest candidates in each election (panel a) and within each party that is present in the dataset at least twice (panel b). The medians are 23 and 15, respectively, indicating that there are substantive amounts of disparity in the ages of both candidates within each election and parties over the years.

Figure 2. Distributions of age difference between youngest and oldest candidates within each election and party.

After collecting the data on age, I used the questions on how much does the respondent like each one of the parties in that election and picked the highest value across all to identify the party the respondent likes the most.Footnote 5 That is used to create the Leader's age variable, namely how old is the party leader of each respondent's favourite party. A total of 6199 respondents (1.5 per cent of the total) disliked all parties – meaning, they gave a rating of 0 to all options. Those were removed from the analysis. Further, in several presidential countries parties have pre‐electoral coalitions. If a respondent's favourite party is a junior partner in a pre‐electoral coalition, I treat the leader for them as the leading candidate in that coalition.

This operationalization makes it possible to test the mobilization effect of leaders for those who sympathize with them and would be more likely to vote for their parties. This variable has several advantages over potential alternatives. First, one could think of using the question that asks respondents directly how much they like/dislike each leader. However, this was not asked in Module 3, which means losing 20 per cent of observations and a gap of almost a decade right in the middle of the study period. A second alternative would be the party ID question, but a large number of respondents do not report feeling close to any party. Of those who do, they are much more likely to be interested in politics and therefore to vote, which means less variation in turnout.

The other main independent variable in this analysis is age. It is measured in years, as respondents' age when the election took place and transformed into four categories: respondents up to 29, between 30 and 44, between 45 and 59 and older than 60. The Online Appendix includes models with different operationalizations, and they do not change the substantive results. Third, to test whether effects change over time, the year of the election is also included. It is present in all models also to capture secular trends in turnout.

Finally, the mechanism linking leaders' age to youth turnout is tested with two other questions present in all modules of the CSES. Democratic satisfaction is captured by the question worded as ‘On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in [COUNTRY]?’. This has been recoded to range from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), with ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’ as 3.Footnote 6 Political efficacy is captured with the question of whether ‘Who people vote for won't make any difference’ at 1 to ‘Who people vote for can make a big difference’ at 5.Footnote 7

Further variables that typically affect turnout are included as controls. At the respondents' level, there are their gender, educationFootnote 8 and whether the respondent is currently unemployed. Another covariate is included from the party‐leader level, which is leaders' gender. This is then interacted with respondents' gender, since there may be higher mobilization potential for parties with female leaders among women. Moreover, women do not become party leaders at random, but rather in difficult times (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2015), which may impact turnout among sympathizers. At the country‐election level, there are three institutional variables that influence turnout (e.g., Elgie & Fauvelle‐Aymar, Reference Elgie and Fauvelle‐Aymar2012; Kuenzi & Lambright, Reference Kuenzi and Lambright2007): whether the election was presidential, if there was mandatory voting, and average district magnitude, calculated by the CSES national teams and standing as a proxy for the proportionality of the electoral system, which has been found to increase minorities and youth turnout (Karp & Banducci, Reference Karp and Banducci2008; Stockemer & Sundström, Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018). I do not use the categorical variable on the electoral system type from the CSES because, in a model also including mandatory voting, a presidential dummy and country fixed effects, it leads to multicollinearity issues. The hypotheses are tested with generalized linear models with a logistic link function, robust standard errors and all have country and party family fixed effects. Missing data are treated with listwise deletion, meaning that respondents who did not answer (or gave a ‘do not know’ answer) to any question used in the models are dropped from all models – leading to a final sample size of 308,630.

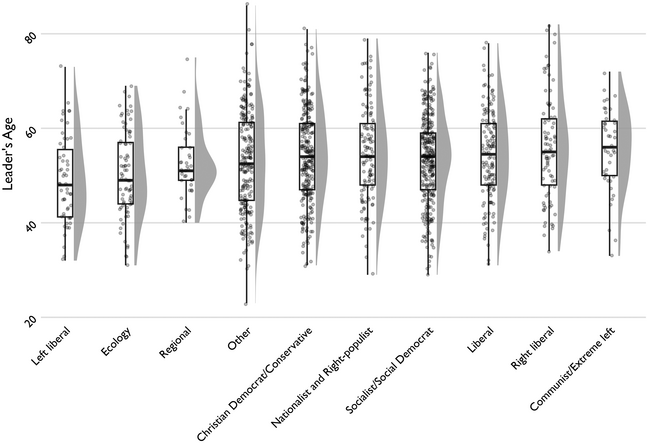

The party families are of the party the respondent indicates to like the most and are drawn from the CSES classification.Footnote 9 Figure 3 shows the distribution of leaders' ages across the party families in this study. We see that parties with the youngest leaders tend to be characterized as left‐liberal and greens, which makes sense given how greens are often associated with young voters and politicians. Parties with the oldest leaders tend to be on the extreme left, showing a clear division to the new type of ecological and post‐material left.

Figure 3. Party leaders' age by party family.

Results

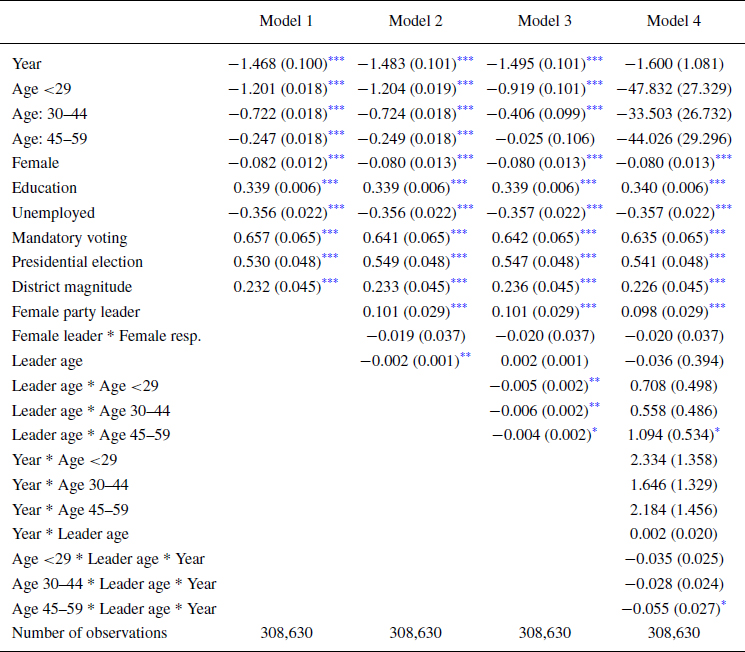

Table 2 presents the main results of the analysis. Model 1 includes only traditional predictors of turnout. We see that they behave as expected. Younger cohorts, women, and unemployed respondents are less likely to vote, while those with higher educational attainment are more likely. The ‘year’ variable has a significant negative effect, capturing the much discussed secular downward trend in turnout rates. Regarding institutional factors, we observe the expected relationships: presidential elections, higher district magnitude for legislative elections and mandatory voting all have positive effects on turnout.

Table 2. Predictors of turnout

Note: All models include country and party family fixed effects and robust standard errors.

![]() $^{***}p<0.001$;

$^{***}p<0.001$;

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$;

$^{**}p<0.01$;

![]() $^{*}p<0.05$.

$^{*}p<0.05$.

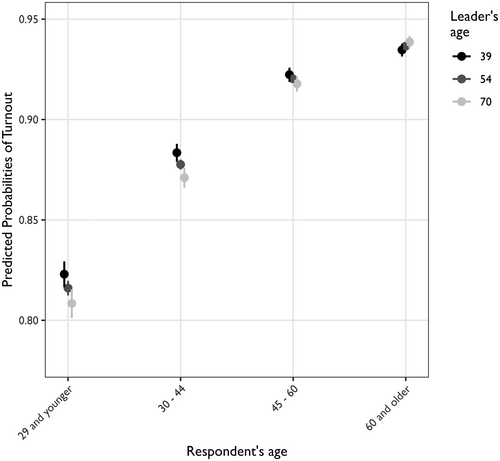

Model 2 includes party leaders' age and gender. Leaders' age has a negative effect, in line with previous research that citizens across the board like younger politicians better. It appears that younger politicians do have better mobilization potential. Model 3 adds an interaction between leaders' and respondents' age, significant for all cohorts in relation to those above 65, with stronger effects for those below 45. This is evidence in favour of H1, namely that younger citizens are more likely to turn out if their favourite party has a younger leader. These effects are visualized in Figure 4. We see that the probability that a respondent older than 45 would turn out is unrelated to the age of their preferred party's leader. However, respondents younger than 30 are about 2 percentage points more likely to vote if their favourite party has a leader closer to their age group instead of an elderly one.

Figure 4. Interaction effect between respondent's and leader's age on probability of voting.

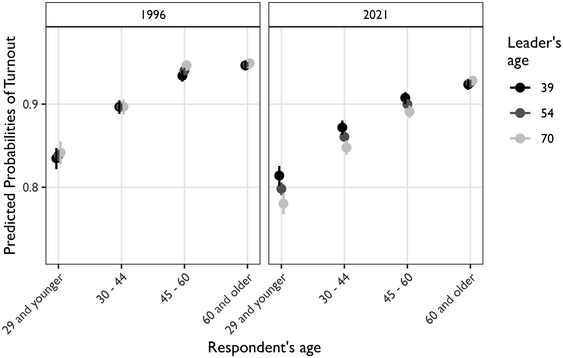

Model 4 moves to test Hypothesis 2, interacting with the effects of respondents' age, leaders' age and year. The effects are visualized in Figure 5. We see that in 1996, turnout was mostly a matter of respondents' age, and there was little impact of leader's age on their decision, regardless of age group. The picture is completely different in 2020. For respondents under 30, their probability of voting is around 4 percentage points higher if their favourite party has a 39 year‐old leader as opposed to a 70 year old. The difference in turnout is a bit smaller but also still there and significant for those aged 30‐44 and shrinks further among the older groups. This shows a clear general trend of preference for younger candidates in 2020, which did not exist in 1996 but also that this trend is particularly strong among those voters who are most under‐represented in partisan politics – first and foremost those 29 and younger, and second those between 30 and 45.Footnote 10 It is important to notice that leaders' ages selected for the figures are not outliers with no support in the data: as seen earlier in Figure 2, a 30‐year gap is higher than average within each election or party, but by no means an extreme case.

Figure 5. Interaction effect between age, year and leader's age on the probability of voting.

Mechanisms: Democratic satisfaction and efficacy

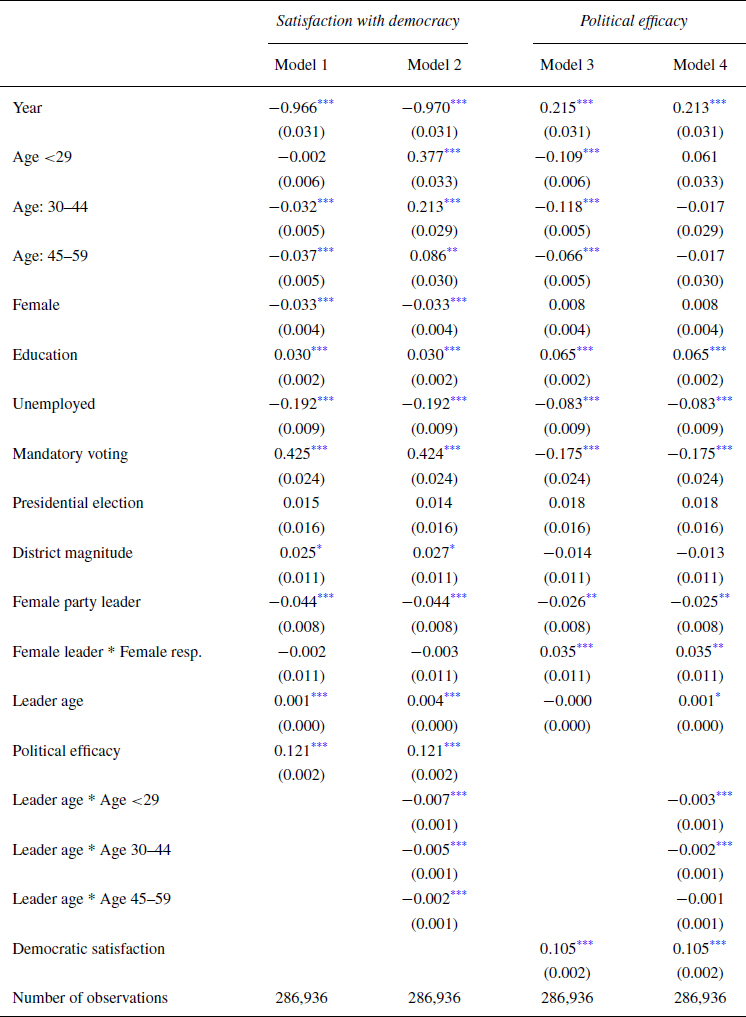

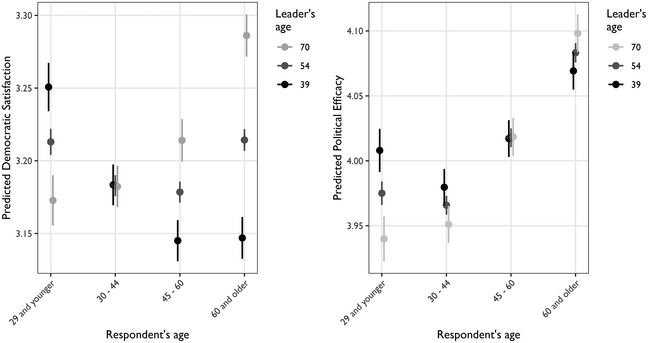

Now we turn to the potential explanations for the mobilizational effects of young leaders among young citizens, namely through increased youth political efficacy and higher satisfaction with the way democracy works. Models 1 and 2 in Table 3 have satisfaction with democracy as the dependent variable, while models 3 and 4 have efficacy, measured as the agreement that ‘who people vote for can make a big difference to what happens’. Both models 2 and 4 include interactions between respondents' and leaders' age.

Table 3. Predictors of satisfaction with democracy and efficacy

All models include country and party family fixed effects, and robust standard errors.

![]() $^{***}p<0.001$;

$^{***}p<0.001$;

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$;

$^{**}p<0.01$;

![]() $^{*}p<0.05$.

$^{*}p<0.05$.

Results are visualized in Figure 6, and they could not be more clear. Young people who sympathize with a party that has a younger leader have significantly higher levels of political efficacy and satisfaction with democracy. Conversely, this time we do not observe the overall trend of preferring young politicians. Those above 60 have higher satisfaction and efficacy if their favourite party has an older leader rather than a younger one. These results give strong support to the argument that younger leaders are more capable of mobilizing young citizens by increasing their satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy. Seeing someone ‘like you’ at a prestigious position within a party you like leads to a higher sense that voting can make a difference and that democracy is working as it should, driving more young people to the ballot box. When it comes to efficacy, we notice in Models 3 and 4 of Table 3 that female party leaders have the same effects for women. Regarding the individual‐level controls, they have the expected effects. People with more education have higher efficacy and are more satisfied with democracy, while unemployment has a negative effect on both, as seen in Marx and Nguyen (Reference Marx and Nguyen2016).

Figure 6. Interaction effect between respondents' and leaders' age on satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy.

The Online Appendix presents a series of robustness tests and alternative specifications: first, instead of using the party the respondent likes best, I calculate which party is closest to the respondent on the left‐right scale, based on their own self‐placement and on the CSES national teams' placement of each party. This variable isolates more the effect of leaders' age, since likeability is more likely influenced by party leaders than ideological self‐placement, but the large share of missing data means thousands of observations have to be removed. Still, results remain substantively the same. Second, models are fit with other operationalizations of age, showing that indeed this is not driven by the cutpoints selected for creating the age groups. Third, there are alternative modelling specifications: one adds a quadratic term to leaders' age since it may be that it has a curvilinear effect on how it impacts youth turnout. Indeed, the quadratic effect is significant and indicates an even larger gap in preferences for young versus older candidates among young respondents. Another specification includes satisfaction with democracy and efficacy as predictors of turnout in the models. As expected based on the existing literature, they are very strong predictors of turnout. In those cases, the effect of the interactions between leaders' and respondents' ages become smaller and non‐significant, which is in line with a fully mediated relationship.Footnote 11

Conclusion

With youth turnout low all around the world, researchers have given much attention to different factors that may affect young citizens' decisions to participate in politics (e.g., Holbein & Hillygus, Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020). Drawing from theories on women's and minorities' representation, this paper argues that the under‐representation of young people is a core factor keeping young voters from getting more involved in electoral politics, due to a lower sense of political efficacy and satisfaction with democracy. Testing these hypotheses with a comprehensive dataset from 58 countries in a 25‐year time period, I find strong evidence that younger candidates have great mobilization potential in attracting younger voters to their parties.

These results are meaningful in several accounts. First, they provide a piece of the puzzle explaining why young citizens, who are not particularly uninterested in politics, still vote less than their older counterparts. The effects identified, of over 4 per cent difference in turnout for young respondents whose party has a 39‐year‐old leader as opposed to a 70‐year‐old one are substantively large and, in times of party system fragmentation and ever smaller margins of victory, can make a difference in electoral results. This is particularly important given that while older candidates fail to mobilize young citizens, younger candidates are not punished by members of older age groups, who still turn out at very high rates. Nevertheless, older voters do seem to have lower democratic satisfaction and political efficacy with younger candidates, even if that still does not stop them from voting. This is a caveat that must also be taken into account when considering the advantages or disadvantages of different candidate profiles.

Moreover, demographic changes across the world mean that societies are growing older. In that context, young citizens are bound to become an ever smaller minority, which may increase age's standing as a social identity. The bias in politics towards older cohorts' preferences, identified by Munger (Reference Munger2022), may in that context be reinforced as younger voters not only become fewer but also if, in the absence of representation, they turn out even less. Given these findings highlighting the importance of age‐based representation, ageing societies may expect to see the strengthening of cleavages along age lines.

Another important implication of these findings is if we connect them to the well‐known fact of voting being habit forming (Coppock & Green, Reference Coppock and Green2016; Dinas, Reference Dinas2012). Turnout decisions throughout one's life highly depend upon their first few elections: people who vote in the first elections in which they are allowed to are more likely to vote for the rest of their lives (Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002). This makes it particularly important for parties to attract youth turnout as a failure to do so can have long‐lasting effects of depressing turnout as generations of citizens do not develop the habit of voting in those fundamental early years. The findings presented here show that, currently, parties nominating younger candidates may have implications for turnout levels for decades to come.

This is because an important finding is that the mobilization effect of age‐based representation has been getting stronger over the years. The literature on age‐based representation has debated whether age is a meaningful social and political group for descriptive representation, the same way that gender or ethnicity are. The argument against it is that age is by definition temporary: people change their age throughout their lives, while ethnicity and gender are much more stable.Footnote 12 However, notwithstanding arguments related to the cohort consciousness (e.g. Munger, Reference Munger2022; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Rouse and Mobley2019), political and social group identities are malleable and can emerge if there is a sense of ‘linked fate’, meaning a perception among members of that group that their personal future is connected to that of the other members (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995). With the emergence of climate change into mainstream political debates and the clear polarization of attitudes around it across age groups, it is understandable that young people today may have stronger feelings about wanting to have their voices heard as young people than their counterparts in previous generations did. These findings point to age as a relevant demographic in which citizens, in particular under‐represented young ones, are more demanding of descriptive representation.

Naturally, this research has its own limitations. First and foremost, given the nature of the data used, it is not possible to causally identify the effects of leaders' age on turnout or efficacy and satisfaction. The regression models presented, while controlling for a host of different factors which may influence those outcomes, are still only capable of providing correlational evidence. Nonetheless, even the correlational aspect is interesting, since it does show the development over the last years of a strong connection between leaders' and voters' age, which is indicative of an increased salience of age‐based descriptive representation. Future studies could use experiments to test whether not only respondents give more favourable ratings to younger candidates, such as in the conjoints analysed by Eshima and Smith (Reference Eshima and Smith2022), but also whether those favourable ratings translate to higher reported turnout. A second limitation is that the study does not incorporate information on why parties may select younger candidates. It may be that ideological changes, or poor electoral results, may drive parties to try younger leaders, much like O'Brien (Reference O'Brien2015) finds for how parties select women as leaders. With these many elections and countries, it is beyond the scope of this paper to study what types of parties are more likely to pick younger leaders, and that is an excellent avenue for future researchers to engage with.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sven‐Oliver Proksch, Jens Wäckerle, Jasmin Rath, Hauke Licht, Paula Hoffmeyer‐Zlotnik, Lennart Schürmann, Matthew Gabel and participants of the Political Behavior and Institutions Workshop at the University of Cologne for excellent comments and suggestions, and Sara Birkner for excellent research assistance. All remaining mistakes are my own.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1: Dependent variable: Turnout

Table B.1: Logistic regression models predicting turnout.

Figure B.1: Interaction effect between respondent's and leader's age on probability of voting

Table B.2: Predictors of Satisfaction with Democracy and Efficacy

Figure B.2: Interaction effect between age, year, and leader's age on probability of voting

Figure B.3: Interaction effect between respondents' and leaders' age on satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy.

Table C.1: Logistic regression models predicting turnout

Figure C.1: Interaction effect between respondent's and leader's age on probability of voting

Table C.2: Predictors of Satisfaction with Democracy and Efficacy

Figure C.2: Interaction effect between age, year, and leader's age on probability of voting

Figure C.3: Interaction effect between respondents' and leaders' age on satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy.

Table C.3: Logistic regression models predicting turnout ‐ age as a continuous predictor

Figure C.4: Interaction effect between respondent's and leader's age on probability of voting

Table C.4: Predictors of Satisfaction with Democracy and Efficacy ‐ Age as a continuous predictor

Figure C.5: Interaction effect between age, year, and leader's age on probability of voting

Figure C.6: Interaction effect between respondents' and leaders' age on satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy.

Table D.1: Alternative model specifications for Models 3 and 4 in Table 2 of the manuscript

Data S1