When the COVID-19 pandemic started in Finland in March 2020, due to the uncertainty about how the pandemic would unfold, my family decided it was better to move from Helsinki to the countryside in South Karelia. Living in the countryside during the worst period of the pandemic proved to be a wise move that gave me ample time and opportunity to walk in the forest. During this time, forests replaced my human contacts, as I took long daily walks from our rental house to the natural forests behind the more pervasive plantation-style forests. These walks were a respite and delight and were the genesis of new kind of relation to the forest. I became much more sensitive to the importance of forests in so many ways. Within these forests alone, with family, or sometimes with friends we often talked about the old forest ways in Finland, what forests are, what it feels like to be in them, and how one should live in a reciprocal, caring relationship with forests. However, unbeknownst to us at the time, these forests would soon be clearcut, as part of the approximately 100,000 hectares of clearcuts done annually in Finland (Sulkava, Reference Sulkava2023). When these forests that I had spent so much time in were clearcut it felt like a part of myself was taken away, and with the loss came feelings of sadness, deprivation, anger, and inability to affect the situation. These situations and feelings are very common in Finland’s current clearcutting hegemony.

Introduction

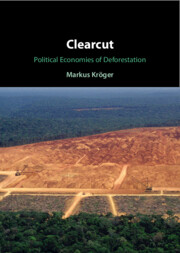

Clearcutting and its effects became a dominant theme in my post-2020 forest walks (see Figure 8.1). First COVID-19, then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, dramatically increased the demand for and price of wood. For example, the export prices of cut spruce (Norway spruce, Picea abies L.) and pine (Scots pine, Pinus sylvestris) rose from the pre-COVID level of less than 200 eur/meters cubed (m3) to almost 400 eur/m3 in later 2021. It went down again in early 2022 to about 270 eur/m3 but rose again to over 350 eur/m3 in mid-2022 due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Maaseudun tulevaisuus, 2024). After these upheavals the export prices have come down, and as of July 2024 they were hovering at around 240 eur/m3. This example shows how epochal moments, such as pandemics and wars, create massive volatility and unpredictability in prices and markets, which has a negative effect on forests because it leads to rushed decisions to cut wood when the prices are high. South Karelia, which is Finland’s most overlogged region due to a heavy pulp and paper industry presence, was especially affected by the Russian border closing and the subsequent drop in wood availability, coupled with higher demand and prices. Since 2021, South Karelian forests have been a carbon emission source, due to overlogging, which was the first time this has happened in all of Finland’s net carbon impacts from land use (Statistics Finland, 2022). Finnish forestry and the forest industry are dominated by pulp, paper, and energywood production, with the production of sawn wood decreasing constantly. Even if this last type of wood was still highly in demand, there is not enough, due to the clearcutting of old forests and overlogging of sturdy trunks. When the Russian border closed, wood had to be procured in Finland, and even the last remaining old, natural growth forests were targeted, even those directly next to people’s houses. Over the last five or so years, I have witnessed the continuous advance of the clearcutting frontier over all the remaining old-growth stands. Almost nothing is left. These old forests could have been protected by their owners, who are our fellow citizens, neighbors, and friends (see Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.1 Map showing the most significant places in Finland discussed in this book.

Figure 8.1Long description

A map of Finland highlighting significant. Key areas include Northern Finland, Varrio National Park, Aalisunturi forests, New Pulp Mill Kemi, Northern Ostrobothnia, Kainuu, New Pulp Mill Ånekoski, Western Finland, Tampere, Southern Finland, Turku, Helsinki, South Karelia, and Lappeenranta. The map also indicates the Arctic Circle, Sápmi Territory, national parks, regions, and cities.

Figure 8.2 An example in South Karelia that shows all the areas that have been clearcut within the last five years (not all clearcuts in the area are shown on this satellite image).

Figure 8.2Long description

Satellite image of South Karelia highlighting clear-cut areas within the last five years. The image shows various patches of deforested land, indicating recent clear-cutting activities. Roads and other land features are visible in the background.

The topic of these clearcuts has not been widely discussed, as it is practically a taboo subject. When it is brought up in discussion, the actions taken are rationalized and justified by irrational claims, typically that otherwise bark beetles would have eaten all the forests. There is a certain sense of impossibility around being able to voice one’s opinion about what neighbors and others in the community are doing to their forests, as these are in fact private forests. In the Finnish context, especially in the countryside, there is a historical precedent of being able to have the right to earn a living, which includes being free to decide how to use one’s own forests, including clearcutting them completely if that is the will of the owner (see Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 A clearcut of what was once was a large, old, natural forest covered with moss in South Karelia, Finland. May 22, 2022.

Figure 8.3Long description

An image capturing a scene of extensive deforestation. Numerous tree stumps are scattered across the ground. Many of these stumps have visible rings. The ground is covered with discarded branches, twigs, and other woody debris, suggesting the remnants of the logging operation. A lone, tall deciduous tree, devoid of leaves, stands prominently in the midground. In the background, a dense forest line stands intact, providing a stark contrast to the cleared land.

Meanwhile, at the same time, a new generation of radical forest activists became active in Finland. These new activists draw on tactics common to Extinction Rebellion (XR), such as occupying company headquarters. This new forest movement built on the work of prior generations of activists doing work in the 1980s and 1990s, for example Luontoliitto (Nature Association) and Greenpeace. These organizations were also involved in radical forest acts and have shared their knowledge and skills with the new wave of activists, according to the members I have interviewed. The rise of the post-2020 forest movement came after a long pause in direct-action activism and seemed spurred into action after logging levels started to increase. I do not think that these are separate events, as many young people found that others were also feeling desperate, angry, and frustrated with seeing the continued destruction of even the last few remaining spots for engaging in forest life. This forest life includes, besides the worlds of all the other-than-humans, human activities of gathering berries, mushrooms, hunting, walking, or simply enjoying the beauty of the forests.

I watched in horror at how quickly new logging roads and bridges were built, to allow for the dragging down of entire moss-covered beautiful forests, transforming them into unrecognizable muddy clearcuts as the earth was turned over by heavy machinery and new trenches were dug so deep and wide one could hardly jump over them (see Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 Example of the deep trenches that are excavated in the clearcut areas. South Karelia, from the same clearcut area as the prior photo (Figure 8.3) taken two years earlier, showing how clearcut areas stay desolate and deforested for many years. April 16, 2024.

Previously, these moss-covered old forests felt like places for forest spirits or other-than-humans, and indeed they were full of animal tracks during winter when skiing through them. Now, with all the old and natural forests gone that were within walking distance from where we stayed, only the plantations and seminatural forests remain. These areas are more difficult to walk through and do not have as many wild berries or mushrooms. With the destruction of these old-growth forests, I see very little reason to continue to stay in the countryside. It would be important – no, essential, for numerous reasons – to live next to raw nature and forests. However, in Finland it is currently easier to live next to a forest in the city than in the countryside, given the lack of conservation areas or security for forest cover. The worst thing is that people can no longer even dare to form emotional ties to the forests they enjoy, since those forests can be taken away from them at any time for any reason at the whim of the landowner. In cities there is at least some measure of democracy and some ability to affect municipal decision-making in relation to the forest management. In the countryside, there is none, as the private property ownership on forest estates expands. It is truly hard to fathom a situation where rural-dwellers could – without being ostracized – challenge or even voice discontent over the choices individual forest owners make.

In this setting, I spoke to seasoned forest professionals turned activists about the rise of the new generation forest movement with their contentious tactics. The consensus was that these new tactics are a good thing as they might possibly change the status quo as they could potentially shake people out of their indifferent stupor and make them begin to realize what is going on. We need to be asking questions like, what are we doing with our forests and what affect does this action have on forest beings? Who is making these decisions and why? What is driving this rise in clearcutting, even amidst the existential crises caused by climate change and biodiversity loss? In this chapter, I seek to provide systemic answers to these questions, based on global and national histories and extractivist systems’ power. I also explore how recent resistance is challenging the power of the clearcutting RDPE in Finland.

The Global Pulp Boom in Finland

The story of Finland’s new post-2015 pulp boom starts much earlier and involves places far outside of Finland. Since the 1970s, and especially since mid-2000s, a wave of new eucalyptus-based mega pulp mills have been built in the Global South, especially in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, Malaysia, and Indonesia (Kröger, Reference Kröger2014). These mills have flooded the market with cheap hardwood pulp, which is used in tissue, paper, and cardboard production. However, to increase the quality for specific wood products such as paper packaging, pine and spruce softwood pulp is also required. This first large eucalyptus hardwood pulp boom in the Global South is causing major impacts in the Global North, especially in Finland, driving a new softwood pulp boom. The impacts of the northern boreal forest softwood pulp boom in Finland are most visible through the construction of new mega pulp mills in Äänekoski and Kemi. These mills were constructed by Metsä-Botnia (called Metsä Fibre since 2019), which left Uruguay after there were intense major protests against its Fray Bentos pulp mill by Argentineans across the border river (Kröger, Reference Kröger2007). The contested mill was then sold to UPM, which is a Finnish paper company that is one of the top three global paper companies by size. Stora Enso, another company, headquartered in Helsinki, is also in the global top three. However, even though these two companies are run from Finnish headquarters, over 60 percent of both are owned by foreigners and foreign institutions. Several activists explained to me in May 2024 that it is the presence of so many powerful forestry companies that pushes the continuation of clearcutting. I asked these activists how they thought individuals could influence clearcutting decisions. I was especially interested to hear which actions they thought could discontinue clearcutting, to which an expert linked to the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation (Suomen luonnonsuojeluliitto, SLL) replied:

It is hard to see that this could have been done with any human resources, especially as the activity [of clearcutting] is so wide-spread, and as there are so many forestry companies here, so that even if you would be able to have an effect on one, another comes and logs away anyway that forest, if somebody wants to sell.

However, another activist from the new, more radical Metsäliike (Forest Movement) group, Minka Virtanen (interview May 12, 2024), explained, based on her experiences, how they have managed to nevertheless stall some clearcuttings on state lands. I will return to these actions later. Besides the presence of these powerful national companies, foreign funds continue to play an even larger role in the purchase of Finnish forestlands, as forests are increasingly seen and treated by investment circles as an alternative commodity. This neoliberal global financialization of forests changes the way people treat forestland. It should be noted here that forest is a term that is not always clearly defined. Often, what these companies call a forest is increasingly viewed by locals and researchers as some form of tree plantation and not as an actual forest.

Finland has a long history as a core country in the global pulpwood expansion. First, it was a key player in the development of mega-plans to impose large pulp investment models on the Global South and in Finland itself, designed largely by Finnish forest industry engineers and consultants, such as Pöyry (merged in 2019 with a Swedish company into a new company called AFRY). In addition, Finnish innovation and machines are deeply important as over 70 percent of the world’s pulp flows through machines made in Finland in the Metso and ANDRITZ factories, while Ponsse is the world’s leading producer for forest harvesters. In addition, there are Finnish corporations involved deeply in the chemical industry, which is a crucial player in pulp- and papermaking. These companies have recently internationalized their ownership, but still retain key operations in Finland, where the physical forests are just a tiny fraction of the true global reach of the Finnish forest industry.

A peculiar feature of Finnish forestry in the global setting is the high number of family-held forest estates. This is due to a history of forest ownership being fragmented and divided due to a general parceling out of land at the end of the nineteenth century, followed by successive pro-poor land reforms that further divided forest ownership between 1920s and 1950s. Some key milestones in this socially just transition – from large estate and a tenant farmer system – were the 1930s agrarian reform laws named after President Kyösti Kallio, and the implementation of laws in the 1940s–1950s, which distributed land to approximately half a million Karelian War refugees after their lands were ceded to the Soviet Union in the Second World War (WWII) (Kröger & Raitio, Reference Kröger and Raitio2017). This has created a particular character and structure in which forestry capitalism operates in Finland. The key impact of this structure has been the need to turn industrial forestry into a national project by major social maneuvers, that have coerced, but mostly hegemonically allured, forest-owning and nonforest-owning citizens to support the goals of the forest industry as if these were the only right, righteous, and most beneficial developmental options. This rhetoric goes so deep that it paints industrial forestry as the basis of survival for the whole nation. These measures are important to secure wood from the hundreds of thousands of different small plot owners. Therefore, nascent attempts to conserve and protect more forests have been heavily criticized by the pulp and plantation forestry sectors. Meanwhile, criticism of the forest industry has been silenced, especially the critique of clearcutting.

Critiques of Clearcutting

The pulp industry is not only dominant but also hegemonic in Finland and especially in South Karelia. A researcher who requested to stay anonymous described the situation as follows:

When the forest industry says that they consider nature, then people believe [it], since they output quite good greenwashing regarding this. Decisionmakers are taken to some shows, where they take care of forests with skill, and ensure that all is fine.

The same researcher indicated that this greenwashing is happening a lot, “They have the resources to communicate as they wish about these things.” I also interviewed another source who requested anonymity, who is a member of the XR and the new more radical Metsäliike forest movement. Metsäliike mounts protests by physically occupying pulp mill entrances and headquarters using sit-ins and roadblocks. These techniques have a history in Finland dating back to the late 1970s; however, in those early protests it was more common to just bar loggings in forest areas. I asked this activist about whether the pulp industry has dominance and hegemony, and he saw that this is a “kind of truism, [or] obvious” in the Finnish forest politics and society. The activist saw that some entities form this kind of hegemonic grouping, including the big pulp companies, the forest owner associations linked to them like the Central Union of Agricultural Producers and Forest Owners (MTK), some parts of the state like the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MMM), and the economic part of Metsähallitus (a state-owned entity that oversees forest management). The activist elaborated that, “at least by us among the activists this is the assumption.”

There has always been some level of resistance to the clearcutting, even in the 1940s and 1950s. According to the same activist there were lot of local people resisting “the extension of this modern industrial power usage and land usage to even those areas,” referring to North Karelia’s very old forests, which was done in a top-down manner, “without asking much.” The activist indicated that in these regions there is still “collective trauma due to the way the industrial land use was milled through particularly this kind of areas.” Previously these areas, including Kainuu, Northern Finland, and Sápmi, had remained “relatively long out of the reach of intensive land use.” The process of industrial forestry coming to these areas is detailed by Ilmo Massa, an environmental historian, in his book Conquest of Northern Nature (Massa, Reference Massa1994). This process was also explored by Ritva Kovalainen, with some emotionally strong film footage of the North Karelians who had grown up walking the ancient and magnificent forests of Ilomantsi by the border with Russia, which were devastated by clearcutting. In the footage these people walk on the clearcut area, remembering the tall trees and what was lost when the area was taken by force (Kovalainen & Seppo, Reference Kovalainen and Seppo2018). The activist reflected on how it must have been when this landscape changed. He said, when it “started to be steamrolled, it must have been quite a stunning” experience as “people did not have the feeling” that this could be resisted as the clearcuts were linked to “national interest and wellbeing narratives … that it is about everyone’s interests, when [they are actually] talking about the interests of the industry.” This activist-scholar also indicated that it would be interesting to study the environmental history of ideas in relation to the Centre Party, which is the most pro-clearcutting party in Finland. In particular, he thought that it is important to develop a deeper understanding of how the Centre Party land use thought models “became so dominant especially in rural societies,” and of the explanatory factors behind this dominance.

What does deforestation and clearcutting mean in this context? Forest removal, or deforestation, as terms, should also be inclusive of areas where clearcutting completely transforms the character and web of life in a given area, even if the area is being planted with trees, left to regrow in a semicontrolled manner, or ultimately become a tree-covered area again in the future. While there are legal requirements in place that forest owners must plant new seedlings on logged forest land within five years of harvesting, the seedlings are not able to directly replace what was lost. In essence, the continued clearcutting of natural, seminatural, old-growth, and other forests that are more than 60 years of age results in forest removals even if new seedlings are subsequently planted. These forest removals are hard if not impossible to replace within a human lifetime and have devastating effects both ecologically and biologically. By clearcutting these last remaining natural or old forest areas, entire habitats, species, and webs of life are becoming extinct or further endangered by the resulting fragmentation and degradation. This is especially true in the areas immediately south of the large national parks in the northern parts of Finland. It is notable that most of the large national parks are located on the Sámi homeland, where Indigenous people’s rights have thus far been effectively mobilized by the Sámi, although intensive industrial loggings have ravaged large areas in Inari municipality and in the territory of the Lapland reindeer-grazing association, which both belong to the Sámi homeland. While many Sámi homeland areas have been extracted by industrial forestry and gold mining, much more natural forest is left in the Sámi homeland than in the Finnish part south of it. According to my informants, this is due to the mostly successful prevention of state logging in Sápmi, through the resistance efforts of the Sámi and reindeer herders. Besides national parks, there are also vast wilderness parks, which are mostly low producing in terms of cubic meters of wood and where clearcutting-based forestry would not be profitable. It takes a millennium in the far North to reach the point where you could even talk about primary or virgin forest area and already there are extremely limited areas of this kind of forest in Finland, namely the Värriö Strict Nature Reserve in Northern Finland and some other scattered plots (Kovalainen & Seppo, Reference Kovalainen and Seppo2023). To reach this point the forest needs to have several complete lifecycles (about 70–80 years) without the dramatic interruption of the lifecycle by clearcutting.

Origins of Clearcutting

The current emphasis on clearcutting was primarily enabled by post-WWII state actions, which were pushed by a consolidated paper and pulp industry that has now become dominant, and pulled by international demand for cheap, good-quality pulp and paper products that could be consistently and reliably delivered. Before WWII, clearcutting was called forest raping in Finland, but during the war Finland needed wood and foreign currency. This need led to the adoption of warlike attitudes and methods, which quickly turned vast areas of forest into money via clearcutting. Clearcutting was a rare exception before WWII and a special permit was required to even be able to clearcut. The word that was earlier used for clearcut, ravaged forests (raiskio) in Finnish was used later in its verb form (raiskata) to refer to sexual violence against humans. Considering the evolution of this term, one gets the idea that the first clearcuts must have been truly traumatic events for the people experiencing the loss of their old-growth forests, as they were forced to cede them. There was much violence and coercion involved in the initial clearcuts and throughout the process of slowly making people accept clearcuts as part of the scenery.

Clearcutting was a story of economic growth and served to quickly strengthen national welfare in a battle of survival among nations. After the war, Finland needed to rebuild its economy and it had to pay the Soviet Union compensation for its losses in the war. In this atmosphere, the forest industry was seen as a national-interest sector and an easily accessible way to increase revenues. Thus, the prior practice of selective loggings was banned in 1947 and clearcutting turned into the only way to practice forestry in Finland. It also became obligatory to belong to a regional forest stewardship association (metsänhoitoyhdistys), which in practice dictated to forest owners how to treat their forests. This was a top-down model which ended up severing the old ties Finns had to forests, which included taking care more personally of the heritage woods and trees. Historically, the forests, while used for resources, were not regarded with an extractivist and productivist attitude, but more with a more holistic and reciprocal attitude.

I asked expert informants what causes clearcutting in Finland. Jyri Mikkola, a forestry engineer and nature surveyor, mentioned to me in an interview on March 23, 2024, that it was, first, the “German, Central-European forestry tradition, which brought them [clearcuts] here.” This import of clearcutting had happened already in the first half of the twentieth century but clearcutting only started in earnest after WWII, due to the war reparations. In his view, the mentality of the postwar period “is still affecting here,” but he called the mentality a “great Finnish forest economy fable,” which claims that “everything is the best of the world in here [Finland] and everything has been done correctly and in best possible way in here.” This fable, myth, is a problem, as “particular generations in forestry have been taught into [believing] this.” The people trained under this mentality in the 1960s–1980s are still in power in Finnish forestry and they do not accept criticism of their ways of doing and knowing. “It was hammered hard onto their heads that clearcutting would supposedly mimic natural processes, and whatever,” so this story has been “created for practical political purposes,” to which those within the RDPE influence have “sticked onto, hanged on.” Mikkola mentioned that Nils Arthur Osara, who lent his name to the largest clearcut areas in Europe that were completed in the 1950s, known as Osaran aukot (the Clearcuts of Osara) in Pudasjärvi in Northern Finland, was a “servant executing and getting blamed for” these clearcuts, which Osara himself thought were a “great mistake” by the early 1960s. The clearcut area was about 18,000 hectares (Enbuske, Reference Enbuske2010: 261).

Second, a big part of the problem is that clearcutting became institutionalized and protected by a certain organization. This organization, with all its political influence, became a form of “machinery that adopted” clearcutting “as the only choice,” and consequently this story “has been maintained.” As time passed, the main motif of this pro-clearcutting organization became “to protect the organization, its actions, itself.” This attitude is still visible, especially in the Forest Management Associations (Metsänhoitoyhdistykset, MHYs), who get the most profit from mediating wood sales contracts between forest owners and companies, “earning a higher provision sum at a single time if more wood is taken at one time.” It is this system that drives clearcutting and had a role in “affecting [the] counseling advice” given to forest owners. “After clearcutting, forest is planted … and the same association provides the seedlings … and sells the services for sapling stand forestry.” The association earns “manyfold [more profit]” if they suggest clearcutting in comparison to what they would get with other types of forestry: “This is one reason, why so many clearcuttings are still done here, also much in such places where that would not be wise for the forest owner.” A forest carbon researcher wanting to remain anonymous out of fear of losing their job told me in May 2024 that “typically the metsänhoitoyhdistykset do not offer” these alternatives, but “have just this one way [clearcutting], by which forests are treated.” Yet, Mikkola told me that while clearcutting as the best and only choice is an “austere myth” and only a “business model,” it still must be faced because as a practice on the ground it is still “very real.”

The moral economy has been heavily molded to support clearcutting. “An idea that this is the only right way, only way to do more efficiently, has been inculcated in the forest owners and others,” which also explains the conundrum where clearcutting is continued at such a great scale. Approximately 70 percent of Finns do not support clearcutting (Juntti & Ruohonen, Reference Juntti and Ruohonen2023), thus, in this sense the hegemony in Finland might be based to great degree on fear, silence, passivity, and a dearth of contentious agency.

Post-2020 Forest Conflicts

Forest conflicts have been on the rise again recently (since the last wave of direct-action activism between 1980s and 2000s, see Greenpeace Suomi [Finland], 2009; Kauppinen, Reference Kauppinen2021; Raitio, Reference Raitio2008; Suomen luonnonsuojeluliiton Kainuun piiri ry [Kainuu district of the Finnish Nature Conservation Union], 2008), with most Finns demanding less clearcutting and more conservation of forests, but this intention is not often reflected in practice. Therefore, a new movement, called Metsäliike, has recently held forest protests; for example, in early 2023 this new generation of activists repeatedly blocked the logging of the Aalistunturi forests in western Lapland (Suutari, Reference Suutari2024). The activists in Metsäliike originally came from movements and organizations like XR, Greenpeace, and Luontoliitto. However, Metsäliike has since grown into its own independent movement that focuses on direct action. The activists have been met by police, armed with rubber bullets, ready to repeatedly drive them out of the logging sites, jail them, and issue tens of thousands of euros worth of fines for the damages the activists allegedly caused the loggers. The forests where they are protesting logging are owned by the state of Finland and administrated by the Finnish Forest Service or the “Forest Government,” which is the literal English translation of its name, Metsähallitus. Its subcompany, Metsätalous Oy, is the business firm responsible for logging on state forestry lands and pays rent to the state for using these lands. Thus, these forests are owned by Finnish citizens, yet the citizenry has very little control over how the forests are used. In the Aalistunturi case, locals proposed the creation of a new national park in the area, as there are too few continuous larger forest areas in that region, or in Finland overall. However, Ida Korhonen told me that the state forest company started to log despite these plans, which is why the Aalistunturi campaign called for the state to give more value to the wishes of locals. However, the MMM has traditionally favored increasing logging and has forbidden making changes to logging plans even on areas that have advanced to the assessment phase in other Ministries to be turned into natural parks, such as Evo, according to Jyri Mikkola.

There has been a rise in the documentation and voicing of the hidden sadness of the common Finn on the painful loss of the forests of their youth. These feelings of sadness and anger are not welcomed in the moral economy of clearcutting. Kovalainen and Seppo (Reference Kovalainen and Seppo2014) have documented the relationships some Finns have with specific trees; for example, holy trees, family trees, trees as friends, trees to talk to and communicate with, trees you do not cut. These trees carry much more meaning than the anthropocentric and productivist view of the forest offered by the dominant system through its language of cubic meters and the monetary valuation of all aspects of nature. Kovalainen and Seppo’s work has also included a collection on the forestry practices that have rendered places unrecognizable, especially by vast clearcuttings and the accompanying dredging of forests, which make them hard to pass through or walk in and pollutes lakes, rivers, and the Baltic Sea with silt and other debris. Approximately 1.4 million kilometers of forest trenches have been dug in Finland (Juntti & Ruohonen, Reference Juntti and Ruohonen2023).

As a response to these moves in the moral economy, rising voices from the pro-productivist camp have issued statements on social media emphasizing that ownership is holy and the landowner has the right to do whatever they want with (forest) land. The entities most strongly emphasizing the property and control rights of forest owners – for example MTK, MHYs (which are part of MTK), and the MMM – are interestingly those that earlier forced forest owners to clearcut against their will. This suggests that the issue is not actually about safeguarding forest owners’ rights to do what they will with their forests, but to ensure the continuation of clearcutting and the flow of cheap pulpwood. While there is much talk by the above entities’ spokespersons currently emphasizing that ownership should be holy or that a forest owner can do what they want to their own forests, these entities are, however, against increasing funding for voluntary conservation (possibly apart from MTK, which, according to Jyri Mikkola, has repeatedly taken a stand on increasing the funding of voluntary conservation). However, this kind of conservation option would increase the range of freedom of forest owners, allowing for the option to conserve instead of logging. Currently this option is very limited and depends on governmental decisions and the monies allocated to conservation, which have been low for several reasons. According to my informants, these reasons include lobbying by the industry, but also the ideological support among many political parties for forest economy and the support by the Ministry of Finance for decisions that do not increase the state budget.

In the moral economy, clearcuts are also at odds with the deeply rooted practice of “everyone’s rights” (jokaisenoikeudet) in Finland, which refers to the freedom to roam throughout the whole country, to collect mushrooms or berries, irrespective of who owns the forests. It is legal for the forest owner to clearcut irrespective of these established customs, but this does create conflicts between different forest users. Recently there have been growing demands to revise everyone’s rights, especially by vocal forest owners defending clearcutting, but in practice this has already happened due to the lessening of natural forest areas. Now too many forest areas are very hard or unpleasant to pass through due to the heavy logging, the spread of monoculture tree plantations that are too thick to run through, and the continuous tree thinning, which leaves the cut branches on the forest floor. In addition, these measures lead to the fragmentation of the forest. Kovalainen and Seppo (Reference Kovalainen and Seppo2014) calculated the amount of time it takes for one to walk across a forest patch in Southern Finland, which in most cases was only a few minutes, with journeys that took over half an hour a rarity (Kovalainen & Seppo, Reference Kovalainen and Seppo2009).

The scenarios that are drawn up for future forestry do not typically include the impacts of the disturbed global climate with its regional and global tipping points, pests, and other novel damages. Boreal forest removals constitute a regional climate tipping point, meaning that the overharvesting and climate-change-induced losses can result in irreversible losses of boreal forest cover and carbon sinks and storage, which now hold about one third of terrestrial carbon stocks (Planet Snapshots, 2023). Warming threatens to surpass ecological tipping points for many trees, which are not able to sequester carbon in the same way they could before (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Davi and Magney2023). Entire forest ecosystems, especially on southern edges of the boreal forests, can collapse, as an overly warm climate does not allow the trees to continue to photosynthesize to the same capacity. These processes flip forests from being carbon sinks to sources of carbon emissions and should be avoided at all costs. The best remedy for attaining more robust, climate resilient forest area is to avoid this type of flip, in addition to lowering carbon emissions and retaining natural forest cover by avoiding logging and plantation expansion (Law & Moomaw, Reference Law and Moomaw2024).

Reasons for Recent Clearcutting Expansion

I have felt these changes in Finland. I have personally seen the dramatic expansion of the clearcutting frontier over last remaining old and natural forests, especially in the southeastern parts of Finland, where there is the smallest amount of natural forest and the heaviest pressure for wood by the regionally concentrated forest industry plants. According to the Natural Resource Institute Finland (Luke), the overlogging, which routinely surpasses sustainable logging levels, was highest in the southeastern part of Finland between 2015 and 2018. It is important to note that the sustainable logging levels referred to by Luke do not refer to the actual, natural level of sustainable harvests (which are much lower), but to the ability to maintain the economic-technical aspects of yearly logging so that the amount logged in one year would not mean the decrease of logging volumes in the subsequent year. If Luke considered a sustainability which would include the needs of nature (this is seldom done), the level of sustainable loggings would be much lower. In May 2024, Ida Korhonen from Metsäliike told me that sustainability from a nature perspective is surpassed by the current logging in most of Finland’s provinces, possibly in all of them.

As the Russian imports have ceased, more wood is logged in Finland, especially in South Karelia, where the pulp and paper industries are dominant. About 4,000 people’s work was needed directly in the forest sector in South Karelia in 2020 according to Luke, with the figure expected to drop to 3,200 by 2040 (Kärkkäinen et al., Reference Kärkkäinen, Eyvindson and Haakana2024). The sector’s share of those employed was 7.7 percent and the value-added to the regional economy was 18.9 percent (approximately 750 million euros) in 2020. This is well above the numbers for the whole of Finland where the added value of the forest sector is just 4.5 percent and the share of employees is just 2.7 percent. According to Yrjö Haverinen (interview, April 24, 2024), a retired forestry professional who is currently active in the South Karelia SLL branch, more forests “have been logged than there has been growth” in South Karelia, meaning that “that capital has been eaten,” especially due to cessation of Russian wood imports. These imports from Russia were substantial, still approximately 9.3 million cubic meters (MCM) in 2021, which is about 10 percent of all wood usage by forest industry in Finland (Puukila, Reference Puukila2023). The South Karelian factories use around 12 MCM per year, but yearly growth is just about 3 MCM, meaning that not all 3 MCM could be cut sustainably. Haverinen stated that “This has caused an enormous pressure on these nearby forests.” For these reasons, no national park has been established in South Karelia, although the local “people would want” one. Haverinen was concerned because the average forest age is “fiercely young,” and “this is worrying as they [trees] are felled like as child, but if they would be left to grow to timber tree and even older, we could get more carbon stored from the atmosphere.” A local politician, a municipal councilor who wanted to remain anonymous due to fear of repercussions, commented on the situation in an interview in May 2024: “This has been like hitting the head on the wall … I have been a counselor for long,” including being a part of the decision-making bodies whose decisions affect the management of municipal forests in practice. “At times the municipality does give us a message that we need to please them [the forest industry] in the handling of our own forests [public forests], that we are their raw material producer, and we need to secure their continuity. This is not voiced officially,” but brought out “in discussions regularly,” which means that a lot of courage would be needed to “start to do something” for protection, “let alone conservation areas.” They had been involved in these politics for over two decades and, during this time, “only two conservation areas” were created, “these being the only victories” for forest conservation. “It has been really half-hearted, and it is really feared that what would for example UPM say” if more areas were protected.

The state and some cities have also their own internal yearly profit target from loggings. For Lappeenranta city this is around 400,000 euros: It is “not visible anywhere” and therefore it “cannot be governed by even decisionmakers.” The profit demand drives clearcutting decisions by the chief foresters, who, according to this informant in Lappeenranta, considered themselves to be “an objective party in all this.” However, in practice, these chiefs “have really a lot of power, and if they do not want something, it does not happen.” The key decision-making around forests in Finland is still very hierarchical and although most people would like to protect forests, the key foresters still hold pro-clearcutting views. The politician said that even though the foresters are basically in charge of what happens to the forest, “they have no expertise” to observe the ecological state of forests.

Pulping Hegemony in the Moral Economy

This reflects the hegemonic situation that persists in Finland, although the role and importance of forest industry has declined in society and economy. Even though forestry is losing ground as an industry it still looms large and important in the culture and mindset of the Finnish populace. “At times it has felt that possibly the forest companies would take care of these things better for nature in the city,” than the municipality, reflected the politician. This is telling of the lingering hegemony and dominance, which are systemic and overarching in the social, physical, and symbolic spaces in most parts of Finland, and not so much tied anymore to specific companies but functioning more systematically and structurally as an RDPE. There are some exceptions, such as the city of Turku, the Tampere region (Juntti & Ruohonen, Reference Juntti and Ruohonen2023), and in Helsinki and Vantaa, where, according to Jyri Mikkola, economic profit requirements from forestry were removed a long time ago. Barring these few exceptions, the pulping RDPE extends across Finland.

An anonymous activist from Metsäliike shared with me in May 2024 that there is an assumption that “all people living in Finland’s periphery would be somehow some real friends of intensive forestry, which is not true, and has never been.” This is because there has been “strong socialization to a certain kind of mentality” after decades of embeddedness with local forestry associations. For example, there might be powerful members or at least “dominant voices” in local communities who have bought quite deeply into the hegemony. In comparison to Brazil there seems to be a stronger hegemony in Finland supporting the deforesting actors, as, in Brazil, whole forest communities or most local people have resisted deforestations, even when faced with death threats and open violence. In fact, the need to use deeper violence is a sign of a weaker hegemony in the Gramscian sense. In Finland, most people have owned forests and been part of the system in some way, especially in the countryside. However, the activist elaborated, “I do not mean to say that only as victims of propaganda, but it has long been that certain social actors have communicated and taught to them to use their forests in a certain way.” As a result of this decades-long propaganda and spreading of just one truth clearcutting, has become the only “right” way of logging. This has created “a kind of culture in that relation to forest and forest use, which is not the whole truth as there are also others, but this is quite dominant.” For example, Finland has the world record of bog trenching; however, at best most of this drainage digging is futile and at worst it is heavily polluting and badly done because over time it actually causes increased eutrophication and greenhouse gas emissions (Riipinen, Reference Riipinen1993). Views on the futility or usefulness of bog trenching vary, and forest economy research has shown that a large part of the trenching did provide wood growth, but critics such as Metsäliike activists claim that Finland should not rely so heavily on the wood-using industry and therefore there should be no need to dig bogs to increase wood production.

When I asked about the hegemony, this activist expert reflected that the ability to organize on such mass scale, enabling landscape-changing efforts across the whole nation, is one sign of how strong the dominance was and continues to be. The efforts to raise wood cubic meter production “were organized in practice not only in a top-down” manner, which meant that local associations and networks were used to “mobilize the countryside and peripheries” to bring them in line with “the work party mentality” of these national projects. They continued to elaborate on this idea, “I feel that that has been how these dominant forest use forms, bad for nature, climate and many people, have been perpetuated for so long in Finland.” This has taken place by “networks extending between the whole state and the local level,” wherein “the interests of large pulp companies are emphasized, and served nationally, and which is wanted to be aided in national politics.” As over 60 percent of forests are still owned by private households in Finland, “forest companies have had to place a lot of efforts to social relation type of issues.” To get social acceptability has thus possibly been even more important in Finland than in many other places (such as South America, where the Finnish, Chilean, and Brazilian pulp companies own most of their lands, or control them by strict leasing, outsourcing, or lending contracts – or are able to perpetuate their illegal and violent land grabs by retaining de facto control over lands they do not have documents for; see Kröger, Reference Kröger2013a; Kröger & Margutti, Reference Kröger and Margutti2024). To get their raw materials these companies in Finland are “dependent … on a scattered group of citizens that happen to own forests,” which has made it essential to have “cultural influencing” by actors such as “MHYs and their counselling services.” In the Finnish context, this activist thinks that to “create a particular mentality and identity has likely been quite central to secure the industrial production and raw material supply, and export revenues, which then go to [benefit] some people mostly.”

This intense effort to build moral economic support, which in turn retains the hegemony for the paper and pulp corporations’ short-term interests, becomes more understandable when one looks at how much the paper and pulp sector extracts from the Finnish society and economy in comparison to how much it offers. The sector represents about 3 percent of Finnish GDP and employs about 1 percent of work force; yet it consumes half of all the energy used by industry in Finland and a fifth of the overall energy use (Majava, Reference Majava2018). In addition, it uses massive amounts of fossil fuels, causes carbon emissions, and pollutes waters (although less than before the 1980s and the introduction of less-polluting pulping technology, see Sonnenfeld, Reference Sonnenfeld1999). Despite these detrimental effects to the environment, the sector continues to receive massive state support; for example, it receives more energy subsidies than any other sector in Finland (Majava, Reference Majava2018). The paper and pulp industry hegemony relies on framing logging and pulp production as a nationalist project, in what could be considered a type of forestry fundamentalism (Rytteri, Reference Rytteri2000). This forestry fundamentalism is an ideology where it is assumed to be obvious that the interests of the large paper corporations and the nation are identical (Raumolin, Reference Raumolin1987, in Pakkasvirta, Reference Pakkasvirta2008). This moral economic support relies on retaining the symbolic alignment that the forest industry has for Finns, for example guaranteeing jobs, maintaining sovereignty, staying successful internationally, and overcoming economic hardships (Donner-Amnell, Reference Donner-Amnell1991; Reference Donner-Amnell2000).

By the 1970s–1980s, the closely knit paper and pulp industry leveraged its state alliance to create a worldwide hegemony in paper and pulp technology, machinery, and consulting services. During this period, the consulting and engineering firm Pöyry became the leading planner of new mills and pursed financiers to fund these enterprises (Kauppi & Kettunen, Reference Kauppi and Kettunen2022). As Pöyry was Finnish, it helped to recommend and export the world-class Finnish technology and plants, leading to the current situation where over 70 percent of world’s pulp is produced by Finnish machinery (mostly made by Metso). However, the post-2008 setting of declining paper demand has meant the rapid downsizing of paper production capacity, and thus the role of the paper sector in the Finnish economy began to contract. In 2016, in a bid to main their role and power, the sector, in collaboration with the Sipilä government, launched a plan to try to grow a “bioeconomy” of trees and wood (Kröger, Reference Kröger2016).

The bioeconomy hype and boom have failed to lower carbon emissions or increase the added value of the forest economy; yet, they have still led to significantly increased clearcutting and short-sighted mega investments such as new large pulp mills that are framed as bioproduct mills, which in practice promote clearcutting to produce pulp that is not strictly needed or sustainable. According to the Finnish Innovation Fund (SITRA), what are especially problematic are the increased tax exemptions and investment subsidies given to entities engaging in biomass burning, which is allowed due to the assumed carbon neutrality of a wood-based bioeconomy (Landström et al., Reference Landström, Kohl, Puroila, Sihvonen and Tamminen2021: 56). This has rapidly increased the number of wood-burning heating and electricity facilities in Finland, which serves as a driving force for the lock-in of clearcutting practices.

The Race for the Remaining Wood

RDPEs often become visible in times of war, when commodity demand and prices increase and more attention is paid to war making than forest protection. When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 21, 2022, most commodity prices began to rapidly increase, especially those related to energy and the war effort. The price of forest biomass at heating plants in Finland has increased exponentially since then, from about 23 eur/megawatt hours (MWh) to over 35 eur/MWh in March 2024. Currently, there is so much demand for energywood that wood is burned that could be used for pulping (Maaseudun tulevaisuus, 2024a). “The pulp industry does not get nearly all the wood it could use” explained Jyri Mikkola (interview, March 2024). There is competition for wood between the pulping and energywood plants, with even the price of thorn trees jumping from a steady price of about 5 eur/m3 until mid-2022 to over 22 eur/m3 in March 2024 (Maaseudun tulevaisuus, 2024b). Mikkola continued, “Chip wood is being paid at times as much [as pulpwood] … the prices have risen awfully,” and chip wood plants pay for wood at times “really a lot.” This situation leads to even more sturdy trunks being burned. According to experts, like Jakob Donner-Amnell, this battle for wood is going to get even more intense in Finland in the near future if this situation continues. In neighboring Sweden, the competition for wood is already much fiercer and Finland will probably follow in the same direction, which means possible cuts in production levels, paying more, and more pressure on forests (Donner-Amnell, Reference Donner-Amnell2024a). I have also observed moves back to coal or turning municipal chip wood plants into direct electric heating, and then investing in alternatives like biogas, due to the doubled costs of wood heating. Meanwhile an increasingly smaller number of key forest owners are making decisions over the carbon stocks of forests and whether they are burned, pulped, or retained.

While there are approximately 600,000–700,000 private forest owners in Finland (which represents approximately 13 percent of citizens), the ownership is strongly concentrated in the highest income groups. Private forest owners are in control of about half of the Finnish forest land. However, a recent report (Juvonen et al., Reference Juvonen, Alhola and Laasonen2024) revealed that half of the carbon stock of these private forests is owned by just 1 percent of the private owners. This is a clear example of the rapid concentration and hierarchization of carbon stock and forest ownership in Finland. Only two thirds of forest owners have more than 1 hectare and only one third owns more than 10 hectares. The high number of forest owners hides these concentrated forest estates, which are owned especially by older men who live in the countryside. Over half of the forest estates over 50 hectares are owned by the highest-earning 10 percent of the forest owners (Häyrynen, Reference Häyrynen2024), which makes journalist Mikko Häyrynen from Metsälehti question the assumption that Finnish forest ownership is an example of “people’s capitalism.” The general forestland concentration (including private and institutional owners) has been driven by the financialization of forest land markets, the entrance of international institutional investors, and neoliberalization of the forest sector, among other causes. The concentration of carbon stocks is telling of two aspects of the increasingly lopsided political economy of forests. First, the bulk of forest owners have sold their old-growth forests, thus, they no longer have this income or capital available to safeguard against bad times (through end-harvesting sales that produce the most income because they include heavy logs). Second, it is likely that the 1 percent who own half of the carbon stock control the bulk of the older-growth, natural forests and they will most likely sell these forests for industry, as the profile of this 1 percent is more often the professional, capitalist investor, who looks primarily for yields. This suggests that the bulk of forest carbon stocks are threatened because there are very few decision-makers. Furthermore, 43 percent of forest owners are retirees, which also drives clearcutting, as forests are sold due to the need to pay the high costs of elderly care and inheritance tax. In addition, retirees have typically been shown to have more pro-clearcutting views than younger generations.

The remaining forests could be protected, but the increasingly concentrated owners do not want to protect the forests for mainly ideological reasons, including a desire to directly resist conservation, among others. These other reasons include, for example, the particularities of the forest conservation policy of the Metso program, where the previous three years’ average prices are used as a basis for compensation if the forest is offered for conservation. During a time when prices are peaking, this means considerably less revenue for the owner than the half-year average that is routinely used by the forest industry when it makes offers to buy wood. There are also not enough state funds allocated to the Metso program, as there are more willing forest owners who want to protect forests and too many important sites to be covered by the funds. This situation has worsened since 2023 with the rise of a far-right government and subsequent cuts to the funds. Many people who live in the countryside are struggling to make ends meet, as they have already cut the most lucrative, old-growth forests, which means they do not have the same forest frontier to turn to for resources when they need money. The voices of those who are called forest professionals in the rural media have also been central in framing forest conservation as being against forest owner and national interests, which has turned many against conservation measures.

Other reasons for not protecting forests is the feeling of losing control over the forests and particularly the sentiment that land ownership should be retained within the family for the descendants. Interestingly, many if not most of these descendants would be more interested in having these forests protected, but the current generation controlling the forests want to either retain them as is or turn them into so-called economic forests. I have also witnessed cases where people are clearcutting their forests before their death to avoid their forests being turned into conserved forests. In one such case, a large landowner clearcut all his forests in Eastern Finland before dying. As he had no direct heirs, in his will he bequeathed all his property to the Centre Party, which has traditionally been the most pro-clearcutting and pro-pulp industry party in Finland.Footnote 1 This political party plays a central role in explaining the dominance of the pulp and paper industry, as it controls most of Finland due to its rural area coverage. Additionally, because it is politically in the center, it manages to be part of most governments, which ensures that the interests of pulp industry are maintained regardless of which party is currently in power. However, it should be noted that the Centre Party is not the only political party that is under the power of the dominant system and perpetuating practices that emphasize pulpwood and clearcutting. This can happen in different ways, for example by approving permits and extensive financing for major new pulp mills, such as the Kemi pulp mill – approved by all parties – which has significantly increased wood demand, especially in Northern Finland.

The Rotation Forest Management–Continuous Cover Silviculture Debate

Only 2–3 percent of the forests in Southern Finland are natural forests (Viitala, Reference Viitala2020), which reflects the cumulative impacts of the post-1950 continued clearcuttings. The bulk of forests are less than 60 years old. Approximately 96 percent of harvesting is based on the even-aged rotation forest management (RFM) (which ends in clearcutting and plantation) and only 3.7 percent on continuous cover silviculture (CCF) (Viitala, Reference Viitala2020). Implementing the clearcutting–plantation nexus, periodical clearcut harvesting, which is also called RFM, is therefore a very novel method, which still has many unknowns in relation to its impacts on ecosystems as it has been in place only for the duration of one forest cycle (about 70–80 years) (Pukkala, Reference Pukkala2016). RFM is based on an even-aged plantation, which is thinned at intervals for energy and pulpwood, and then at the age of 50–70 years clearcut completely of all wood and replaced by a new plantation. CCF avoids clearcutting and retains forest stands permanently, as there are trees at different ages and structures, but this method has big differences and applications depending on the forest context (Pommerening & Murphy, Reference Pommerening and Murphy2004). The thinking about the productivity between CCF and RFM is based on short-term consideration and data, not taking into consideration that there should also be older and larger trees within a forest, for example older than 100 years. It is essential to look at clearcutting as a cumulative, longer-term issue, instead of comparing the yearly clearcut areas to the overall forest area, as the clearcutting-proponents (MTK, pulp companies, and forestry newspapers) often do in the media, which is a tactic to try to downplay the role and impacts of this type of forest removal in Finland (Maa- ja metsätaloustuottajain Keskusliitto MTK ry, 2018). In contrast to RFM, CCF mimics the natural forest cycles and disturbances, as there is some tree removal every 15–20 years and natural regeneration of an uneven-aged forest (Kuuluvainen et al., Reference Kuuluvainen, Tahvonen and Aakala2012). This could help in the current situation where most forest ecosystems in Finland are threatened (Juntti & Ruohonen, Reference Juntti and Ruohonen2023).

Recently, forestry practices have been diversified and made less obligatory by law, although it is interesting that most logging still takes place using clearcutting. This approach is not recommended by researchers, who recommend a maximum of 25 percent of forests should be clearcut. Leaving trees in place is beneficial for the forest ecology (Eyvindson et al., Reference Eyvindson, Duflot and Triviño2021) and it is also beneficial for forest owners who often earn more from continuous cover forestry (CCF) than from the clearcutting model (see Pihlajaniemi, Reference Pihlajaniemi2018). Norokorpi and Pukkala (Reference Norokorpi and Pukkala2018) estimate that CCF is even up to 15–20 percent more profitable than clearcutting. According to Olli Tahvonen, Professor of Forest Economics at the University of Helsinki, the current Finnish forest policy is not based on economic profits, but rather maximizing the cubic meters of fiber wood produced (Jokiranta et al., Reference Jokiranta, Juntti, Ruohonen and Räinä2019: 221). Notably, CCF produces more cubic meters in total, based on long-term field experiments, while clearcutting produces more fiber cubic meters, which are used in pulp making. Yrjö Haverinen, a forestry professional (interview April 24, 2024) explained that it is in the interests of the pulp industry, partially due to the large machines they use, “to get a lot done at one time by clearcutting.” This means that the end harvest will have a lot of pulpwood, “but even before reaching this end harvest age,” the RFM model, using thinning techniques, has yielded a lot of “rod usable very well in pulp industry as raw material,” which is also produced by CCF “but less at a time.”

On a global level CCF has been returning, having had a long history, was although it had been sidelined in past decades by the dominant RFM (Peura et al., Reference Peura, Burgas, Eyvindson, Repo and Mönkkönen2018). There is an overall global and European trend of diversifying forestry to move away from clearcutting; for example, in the draft of its new forest strategy the EU Commission outlined that clearcutting should be avoided (Eskonen, Reference Eskonen2021). Researchers have argued that turning CCF into the dominant forestry model in boreal forests would help to solve many of the supposed conflicts between industrial, recreational, biodiversity, and the other needs of the forests and their users (Mönkkönen et al., Reference Mönkkönen, Burgas, Eyvindson, Perera, Peterson, Pastur and Iverson2018). The versatility, multiple-use-allowing forest base requires turning CCF into the dominant model; however, clearcutting will still retain its place in some landscapes (Eyvindson et al., Reference Eyvindson, Duflot and Triviño2021). Yet, for example, Sini Eräjää from Greenpeace argued that the discussion in Finland has lacked the critical question of who benefits from clearcutting. Eräjää pointed the finger at the paper and pulp industry interests, which have caused forestry in Finland to remain “stuck” in its “own world,” while elsewhere the forest economy has evolved (Eskonen, Reference Eskonen2021). Kunttu (Reference Kunttu2017), the leading forest expert at the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) demands the “renewal and diversification of forestry counseling” away from the clearcutting–plantation model as the “state of forest nature is very worrying.” This is clearly illustrated by the dramatic increase in logging post-2010, which led to forests that had previously been left in peace being targeted. This includes forests that run alongside rivers, very young stands, and small islands of old forests. This increase in logging was caused primarily by the global, East Asian-driven demand for softwood pulp, especially for packing board production. Simultaneously, the Sipilä government made the decision to frame and support forest “bioeconomy” as if it was the new Nokia; yet, in practice this just means building new mega pulp mills (Kröger, Reference Kröger2016). A climate expert at the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation, Hanna Aho, argues that in the current setting of increased climatic-ecological crises, having greater biodiversity, including mixed tree species and unevenly aged trees, functions as insurance, which actually benefits forest owners (Jokiranta et al., Reference Jokiranta, Juntti, Ruohonen and Räinä2019). Adopting this strategy would also help to align Finnish forest policy with the Global Convention on Biological Diversity, which demands reversing biodiversity loss and attaining a net gain in biodiversity.

The Finnish Pulp and Paper Industry amid EU and International Forest Decision-Making

The lobbying power of the paper and pulp industry is extremely strong and has been consolidated over a long time, reaching all the way to the top-level powers of the Finnish state (Siltala, Reference Siltala2018), which means it also extends into EU decision-making. The lobbyists that Finnish members of parliament have met most are from the forest industry and environmental organizations (Helin & Toivonen, Reference Helin and Toivonen2021), which shows how the struggles around continuing clearcutting have moved all the way to the EU level. The paper and pulp industry engages in aggressive lobbying and uses large sums of money to try to control public image and affect decision-makers. However, this comes at the cost of trying to develop truly sustainable and functioning alternatives to climatically and ecologically costly forest products and forestry (Majava, Reference Majava2018). According to Majava (Reference Majava2018), the Finnish forest industry has a key role in ensuring that wood usage is considered to be carbon neutral in international climate agreements. Yet, based on information from the European Environmental Agency Scientific Committee this supposed neutrality is a dangerous fallacy (European Environmental Agency, 2011). This aggressive lobbying forbids making crucial global decisions to curb the climate crisis (Majava, Reference Majava2018) and in turn jeopardizes the future of the Finnish forest industry.

The EU has been trying to place stricter environmental protections to avoid biodiversity loss and combat climate change, for example through the 2023 revised EU Regulation on Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF). This regulation establishes binding national net removal targets for the LULUCF sector based on past greenhouse gases, and it aims for land-based net carbon removals to reach the EU’s climate goals by 2030 (European Commission, n.d.). These LULUCF (European Commission, n.d.) requirements were watered down during the process of lawmaking by an international lobbying campaign initiated by the Finnish and Swedish forest industry, which garnered enough support that the accepted version of LULUCF allowed Finland to increase logging in such a way that it was not even calculated as emissions (Hartikainen, Reference Hartikainen2017). If the original LULUCF requirements had been approved, it is likely that the massive new pulp mills would not had been built in Finland, as the increased logging would have required the country to pay compensation by buying pollution rights or by decreasing the emissions of other sectors. According to Hartikainen (Reference Hartikainen2017), getting this version of LULUCF approved required a particularly strong campaign where the government, members of the EU parliament, bureaucrats, and paper industry lobbyists worked together behind the scenes to steer the EU lawmakers.

Fiber Wood or Sturdy Logs?

The more I have studied the Finnish forestry setting, the more it seems that the system has been built over decades in innumerable ways to benefit the pulp and paper industry’s short-term interests. It would not be in the interest of the pulp and paper companies if the currently plentiful offer of cheap fiber wood decreased. Besides getting less fiber wood, they would then need to pay more for the sturdy trunks, whose production would increase under a CCF system. However, when one considers the whole forest-based economy, having more mature trees would be beneficial, as it would steer the focus away from the misplaced attention given to paper, pulp, and cardboard, which have negative climate and ecological impacts that are far greater than the impacts of other product lines. The half-life of these products is just 2 years, which means half of the carbon captured in the paper and pulp line products is returned to atmosphere in 2 years, whereas for wood buildings and logs the half-life is 25–35 years. Paper demand has also dramatically declined, warranting a change in the currently pulp-focused forestry practices. The increased logging in young forests is detrimental to biodiversity, recreational use, carbon capture and – paradoxically – for wood production, as this logging decreases the growth and the long-term availability of wood for the industry (Pukkala, Reference Pukkala2017a).

Clearcutting produces a lot of fiber wood, which garners a lower price than forest owners get paid for sturdy logs used in sawmills, construction, and carpentry. This is especially true over a longer timeframe, as trees that grow fast and serve well for pulp making and energywood are not dense enough to be used to make things like window frames or furniture. Now Finnish carpenters need to import wood from other countries like Germany. In 2018 at a forest gala (these are organized by Meidän Metsämme [Our Forests], another new forest movement) in Finland (Meidän Metsämme, 2021), Hannes Aleksi Hyvönen, a log builder, argued that mechanical wood processing has a deep quality crisis due to many decades of focusing on pulpwood production, which leaves no good-quality wood for carpenters, carving plants, and small sawmills, which are marginalized and struggle with enormous problems. The clearcutting–plantation origins of the current economic forests mean that one can get less and lower-quality sturdy logs from them than can be obtained from natural forests in Finland (Jokiranta et al., Reference Jokiranta, Juntti, Ruohonen and Räinä2019). The increased growth of wood mass, ensured by “fertilization, seed gene improvement, and plantations,” is of lower quality, producing “soft and sparse fiber wood” that “breaks easily” and has wide growth rings (Jokiranta et al., Reference Jokiranta, Juntti, Ruohonen and Räinä2019: 90–91).

Clearcutting ensures that forest lands, or what used to be forests, are increasingly turned into fiber wood reserves that serve the industry, in a feedback loop. Many areas next to clearcuts are de facto turned clearcuts, as increasing storms, snow cover, droughts, extreme weather conditions, and European spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus L.) and other pest outbreaks lay waste to the remaining, weakened trees.

The Climate Crisis and the Bark Beetle Debacle

Climate warming is advancing several times faster in Finland than elsewhere due to the country’s northern location and other factors. However, most planted forests, which is the state of most of the forests in Finland, have a lot of spruce and pine. Of the deciduous trees, there is too much birch (Betula) and there should be more aspen (Populus tremula) and other deciduous trees for forests to be more mixed. The current monoculture-type forestlands have a higher potential for sudden collapses, ecologically and in the log values for the forest owners. These almost monocultural forests run the risk of being adversely and severely affected by the bark beetles, other pests, diseases, and the impacts climate change. If this happens, the pulp and energywood industries may lose substantially, if for example the pests or fungus that have caused great havoc on pine and birch in other parts of the world spread to Finland. Currently, just 2 percent of Finnish natural forest loss is due to bark beetle, the biggest current causes being snow, storms, moose, and other causes (Tiede lehti, 2024). This fact highlights how the RDPE is using bark beetle as an excuse to execute these loggings, clearcutting huge areas. For example, it is claimed that bark beetle would expand to conserved areas and if a forest owner can show this is the case, they are allowed compensation. However, studies show that bark beetle spread from clearcuts to nearby mature heath-type spruce forests (Pulgarin Diaz et al., Reference Pulgarin Diaz, Melin and Ylioja2024); but, absurdly, one cannot get compensation for this (Ketola, Reference Ketola2024a). I have seen numerous cases where an old spruce forest was severely hit by bark beetle after a clearcut next to it. Therefore, clearcutting close to the few remaining old spruce forests should be forbidden, to avoid spreading the pest and the subsequent loss of these natural forests. According to studies, the best way to retain forest and increase resilience against pest outbreaks is to retain biodiverse, multispecies forest cover with different age trees (Tiede lehti, 2024) – not to clearcut and establish plantations. Currently the bark beetle is one of the main scapegoats for lucrative salvage harvests in Finland, which drives the possibility of bringing more land under the pulping RDPE fiber plantation umbrella.

The bark beetle debacle is worth attention, as it is becoming increasingly a key driver of fast clearcuttings in conservation-worthy old spruce forests, but also in many other forests, especially in Southern Finland. Jyri Mikkola, a conservation expert at the SLL, explained to me in an interview on April 23, 2024, that if there is too much drought, then the trees cannot produce enough resin to drown the forthcoming bark beetle population, which would stop the spread. When there has been two to three consecutive years of severe drought during the growth season (as has already happened) the bark beetle populations can grow practically unchecked. As recent research shows, large forest areas have already died due to the beetles and extreme heat in Southern and Eastern Finland (Junttila et al., Reference Junttila, Blomqvist and Laukkanen2024). According to Mikkola, once the mycorrhiza of the trees get damaged by the drought, it takes about five years for trees to recover. A tree cannot suck enough water from the ground if it is severely damaged by Heterobasidion root-rot. The climatic risk is not limited only to spruce attacked by bark beetle, but also other trees are likely to suffer from climatic extremes, as each species has its own pests and problems. Between 2017 and 2023, in a large area studied in South Karelia, the number of trees dying increased tenfold in just six years. This dramatic increase in tree mortality shows that the climate warming is not good news for the forestry industry. However, to date, the sector has portrayed climate change positively, saying trees will grow faster and further north in Finland. Most worrisome is the speed of increase in number of tree deaths, which is made possible as there is a very high number of clearcut areas (32 percent of the 1,200 hectares studied in Junttila et al. [Reference Junttila, Blomqvist and Laukkanen2024] are recent clearcuts). Once an area has been clearcut, the nearby forests are at the mercy of sunlight and other disturbances. In addition, these forests are often even-aged and weak, mostly monocultural spruce forests, which leaves them vulnerable to pests and disease. It could be said that the problem would not exist in this dimension without the continued and increasing clearcutting, as the aerial images show that a large part of the dead trees are next to clearcut areas.

The tactic of using the argument of salvage harvesting to increase logging is likely to grow in Finland, as this has already happened in other places such as British Columbia (Simard, Reference Simard2021). The currently planted spruce trees are unlikely to reach their maturity. There is little planning for future climatic-ecological conditions in Finnish forestry practice, despite the country having invested very heavily in forestry and forestry research. It is not widely understood that overlogging will not solve the climate crisis but will cause it to worsen. It takes at least 40 years for the areas that are logged to start significantly storing the carbon that is lost in current loggings, as the current logging adds directly to greenhouse gas emissions. I argue that the reason for this continued clearcutting against all logic relies on the fiber wood industry having become regionally dominant, both in the political and moral economy of those who make key decisions about forest use and regulation. I will next analyze more in detail how this sector was made dominant, in Chapter 9, and after, in Chapter 10, discuss the new contentious forest politics in the context of the “bioeconomy” and EU legislation.

In Finland, the post-WWII establishment of a strong paper and pulp industry is the pivotal cause for clearcutting and decreasing the forest biodiversity (Mönkkönen, Reference Mönkkönen, Aakala and Blattert2022). This sector relies on transforming forests into resource reserves primarily for the pulp and paper industry and energywood. The production of fiber mass and the accompanying energy it produces are the key in delineating how forests are used, what kind of trees are grown, where, for how long, and based on what logic. In the fast-growth forests trees compete to reach heights faster, which means they are not producing as good material for wood construction as is found in natural forest trees. Undergrowth is also periodically removed, which harms biodiversity. As this process is very extensive and touches most Finnish forests, it is apt to speak of a regionally dominant sector that changes land areas to mirror its own long-term interests. The fiber and pulpwood interests lock in the use of lands for short-rotation pulp and energywood production by extending tree plantations over natural forests. This happens at the expense of bigger logs and lumber, such as floor and round timber and sawlogs, resulting in less old-growth timber forests. This type of technological lock-in that affects the land use is a very deep kind of power in politics and economy.