I Introduction

A central debate in economic history is whether the ‘Australian Settlement’ has been ‘either too powerful or not powerful enough’.Footnote 1 The outsized role Australian colonial governments had in their economies compared with the Home jurisdiction and the United States is a core predicate of that debate. Colonial Australian governments built major capital assets, operated them for profit, exploited international bond markets for project-finance, were mass employers, labour market-regulators and provided the most generous social insurance in the Anglosphere. In turn, the populace cultivated an investor mentality and aspired to affluence, rather than utopian equality or re-distribution. That curious blend of state-direction within the market-system has long been labelled ‘colonial socialism’,Footnote 2 and was originally called ‘socialism without doctrine’ due to its highly pragmatic and anti-theoretical tone.Footnote 3 It created ‘a regime of economy and society in which state-established institutions … directly regulated or publicly influenced the labour and finance markets’.Footnote 4 Enduring puzzles were left for both ‘market liberals and state socialists’Footnote 5: did state dominance retard or boost economic growthFootnote 6; why did the market paradigm survive once workers could vote themselves wages and pensionsFootnote 7; and was the colonial period really ‘socialist’ if it was racist, affluent and chauvinistic?Footnote 8

The relevance of debates about Australia’s colonial socialism should be obvious to constitutional thinkers. If the colonial Australian economy was uniquely ‘statist’, compared to its juristic ancestors, then the nature of the ‘constitutional state’ in Australia immediately before Federation meaningfully diverged from ‘Washminster’ precedents.Footnote 9 Influential English jurists understood that split with classical liberalism. Dicey wrote that ‘socialistic legislation and experiment have been carried to a greater length in Australia than in England’Footnote 10 and described (locally unremarkable) aspects of colonial government as types of ‘evil’.Footnote 11 The same aversion to state involvement in economic conditions was dominant in US legal circles in 1900. Long after employee-safety legislation was normalised in the Australian colonies, the US Supreme Court (notoriously) invalidated 10-hour work-day legislation in reliance on constitutionalised ideas of contractual freedom from government intervention: ‘the freedom of master and employee to contract with each other in relation to their employment, and in defining the same, cannot be prohibited or interfered with, without violating the Federal Constitution’.Footnote 12 The notions of laissez-faire that underpinned those foundational accounts of early 20th century British and American constitutionalism relied on a severance of economic activity and state power that was alien to the Australian experience at Federation.Footnote 13 Thus, we have reason to revisit the idea that ‘both the Thames and the Potomac flow into Lake Burley Griffin’Footnote 14 and think deeply about a third powerfully distinctive Australian idea of constitutionalism entrenched at Federation. This paper engages in that process of thought.

Part 1 describes three core legal and constitutional features of colonial socialism, guided by empirical findings of Australian economic history. First, from the 1860s, colonial governments owned and operated vast public-capital which required innovative constitutional arrangements including executive bodies which stepped outside orthodox ideas of public office grown in the Westminster tradition with potent powers to transact, hunt for yield and regulate the employment relationship. Secondly, colonial governments funded their public works and employment via their collective (‘pooled’) access to debt capital and foreign investment which they attracted using investor protections given by colonial legislatures which largely neutralised sovereign risk in the heavily indebted colonies. Finally, colonial governments provided universal public insurance programs, initially to public-sector workers and then universally through old-age pensions which required all arms of government to become welfare-distributing bodies: legislatures would set the terms for universal economic dignity, executive bodies superintended those programs and judiciaries resolved eligibility disputes. The model of constitutional statehood that emerged from the colonial phase was one of ‘egalitarian state potency’ which implied a vastly different balance of public and private authority to the constitutions administered in Washington or Westminster in 1900.

Part 2 explores how the distinctive constitutional model developed during the colonial period was entrenched in the Constitution’s text and structure, then by the High Court in its resolution of the Surplus Revenue Case and finally by the electors via the 1910 Referendum. Substantive power to implement colonial socialist techniques at a federal level was unambiguous. The Commonwealth’s explicit power to ‘acquire’, ‘construct’ and ‘extend’ railways, to legislate for ‘lighthouses, lightships, beacons and buoys’ and provide ‘[p]ostal, telegraphic, telephonic, and other like services’ provided proof positive that the system of vast public capital, and regulation of labour markets, of the colonial phase could be nationalised.Footnote 15 Financial power to fund the colonial socialist model was less clear. The Commonwealth could ‘borrow money’, tax and spend,Footnote 16 but the compromises necessary to complete the drafting process, particularly concerning ‘surplus revenue’, left doubts about the Commonwealth’s ability to replicate the financial model that funded the expansive public-sectors of the pre-Federation colonies. Ultimately, the High Court’s intervention was required in the Surplus Revenue Case to ensure the Commonwealth could own and operate large capital assets and provide social insurance. The case concerned two staples of the colonial socialist heritage (maritime infrastructure and universal pensions), and the Commonwealth’s arguments invoked the legal and constitutional novelties of pre-Federal Australian governments. Confirmed by both the High Court and the populace through referendum, the Commonwealth ended the first decade of Federation faced by no major constitutional barriers to implementing the state-dominant economic model developed in the colonial phase.

Part 3 concludes by sketching the radical difference in constitutional perspectives on the balance of state and economy in Australia (on the one hand) and the UK and US (on the other) and indicating future research streams. Both Anglophone ancestors of the Australian Constitution faced severe constitutional crises between 1900 and 1940 which arose from attempts to implement public investment and welfarist policies which were uncontroversial in Australia. The development of a social insurance system in the ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909 caused an inter-cameral showdown that resulted in the Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo V c 13) stripping the House of Lords of its legislative power over public sector finances. That extreme institutional resistance to state-involvement in the economy was predicted (and encouraged) by Dicey as a constitutional battle of ‘liberalism’ against ‘collectivism’ in a world of ‘parliamentary sovereignty’: a constitutional perspective which had no clear analogue within the Australian experience of state-interventionist economic techniques at Federation. A similar pattern is identifiable in the constitutional controversies of Roosevelt’s New Deal, in which judicial hostility to legislative roll-backs of laissez-faire provoked a ‘re-founding’ of the American constitutional settlement. Compared to the popular and technical consensus of Federation-era Australia regarding social insurance and public works, both the type and intensity of the North Atlantic constitutional conflict are alien. The paper closes by mooting potential avenues of future inquiry within constitutional law and theory which may be aided (or not) by the proposed model of Australian egalitarian state potency.

The paper’s analysis generates a number of intellectual yields.

Firstly, it sheds new light on the essential character of the Australian Constitution. Read through the lens of Australia’s economic history, the text and structure entrench a model of constitutionalism within which the state is a potent, transacting, commercial entity (which creates and intervenes in markets) with a strong welfarist capacity (operating generous social insurance programs). Secondly, it makes sense of that vast jumble of constitutional provisions that appear to be simply ‘machinery’ or ‘transitional’, such as the transferral of railways, lighthouses, departments and funds between the new Commonwealth and States. True, they are machinery, but they are not trivial: they nationalised the system of regionalised colonial socialism and have no parallel in other written Anglophone constitutions, because no other early-20th century nation had to federate a socio-economic structure of such state dominance. Thirdly, the paper poses a solution to a long-standing doctrinal puzzle, the Surplus Revenue Case: why did the High Court sterilise the surplus revenue system and thereby entrench the Commonwealth’s fiscal dominance over the States.Footnote 17 Rational justifications for that outcome appear in light of the colonial socialist heritage, particularly a need to cure the mismatch between the Commonwealth’s legislative powers over public capital and social-insurance and its weakness in sovereign debt markets. Although the High Court’s decision may have been partisan, it served a broader purpose of facilitating the transmission of the potent egalitarian model of constitutional statehood from the colonial era onto the national stage.

In each case, something unique emerges: a distinctively Australian constitutionalism, which is neither Washington nor Westminster. While Sawer was right to say that the Constitution ‘is a blend of federalism derived from the U.S.A. and responsible government derived from Great Britain’,Footnote 18 it also entrenches an innovative Australian model of constitutional statehood built around state potency and socio-economic egalitarianism.

Before moving to that analysis, some brief words on the scope of the paper’s literatures and methods. The historical treatment draws on economic works which fall into various ‘schools’ of Australian economic history, which have been divided into ‘analytical’, ‘orthodox’ and ‘radical’, and is more concerned with their common empirical insights regarding the structure of colonial economies, rather than their points of analytic or normative difference.Footnote 19 The methodological approach taken to the casual line of law and the economy is only mildly ‘functionalist’Footnote 20; the paper’s engagement with the High Court’s reasons in the Surplus Revenue Case takes the role of judicial-interpretative choice seriously in structuring economic relationships.Footnote 21 No claim is made that the constitutional balance of state and economy fixed in 1901 is ‘good, all things considered’, but rather that such balance is distinct when compared to American and British national constitutional developments: a juridically significant split in political traditions. Finally, the paper seeks to contribute to the literatures concerning the role of constitutions in economic equality, the financial aspects of Federation and the emerging body of work concerning the Australian Constitution’s distinctiveness in the Anglophone world.Footnote 22

A Part I: The Constitutional State under Colonial Socialism

Describing Australia’s pre-Federation economy as ‘colonial socialism’ was not an idiosyncratic label adopted post hoc. Scholars and political commentators, both domestic and foreign, writing around 1900 characterised the outsized role of the Australian governments in economic and social life as a type of ‘colonial’ or ‘state’ socialism.Footnote 23 Economic historians writing in the subsequent 120 years have followed that usage, relying on the outsized role played by the state in capital formation, credit acquisition and social insurance. Those learnings have not yet been linked to an analysis of legal structures and institutions to reveal the distinctive Australian model of statehood which emerged at Federation. This part undertakes that activity to explore the unique Australian model of constitutionalism which grew in the latter-19th century.

British settlement did not, of course, create Australia’s first economic system. To the contrary, the British invasion of 1788 destroyed the pre-existing ‘Aboriginal economy’: ‘a stably ordered system of decision-making that amply satisfied the wants of the people’.Footnote 24 The ‘destruction of the Aboriginal economy and the decimation of its participants’ resulted in a ‘transfer of resources from losers to gainers’ that should ‘properly be seen as a takeover’, rather than an acquisition, which was effected by violence and gross indifference to suffering.Footnote 25 Britain’s destruction of the indigenous Australian economy did not, however, yield overwhelming economic successFootnote 26; early attempts to implement military-controlled economies and then to replicate British models of public-private franchises failed to build a sustainably growing domestic economy.Footnote 27

A prolonged period of growth was not achieved until the 1860s under conditions of vast government involvement in economic activities that historians term Australia’s ‘colonial socialist’ phase. Let us explore three of its major features. The first feature was public-capital dominance: colonial Australian governments owned and operated the most valuable assets (particularly mass transport assets such as railways, ports, lighthouses and telegraphs) and were the largest single employers. The second feature was public-credit pooling: colonial governments funded their public works and employment via their collective (‘pooled’) access to debt capital and foreign investment which they obtained under preferential market-conditions achieved through sovereign guarantees. The third feature was social insurance: colonial governments provided public insurance programs via pension schemes, initially to public-sector workers and then universally through old-age and invalid pensions. The combination of those features was strikingly distinct to Australia’s constitutional forebears.Footnote 28 In the Home jurisdiction and the US, the balance of economic power was reversed: the largest capital assets were privately held, the people who built and operated them were privately employed, funding for large infrastructure was mostly privately provided, public treasuries largely sold debt to finance defence spending not public works and universal pensions were non-existent.

The unique economic features of colonial socialism entailed innovative constitutional arrangements. Public-capital dominance required executive bodies which stepped outside orthodox ideas of public office and Departments of State which had grown in the Westminster tradition. Colonial parliaments created boards, commissions and agencies with potent powers to transact, hunt for yield and regulate the employment relationship. Public-credit pooling required financial innovation on the part of colonial legislatures and public liability rules which neutralised sovereign risk for foreign investors. Social insurance systems required all arms of government to become welfare distributing bodies: legislatures would set the terms for universal economic dignity; executive bodies superintended those programs and judiciaries resolved eligibility disputes. As with the underlying economic structure, those constitutional arrangements were outliers in the Anglophone world of the latter-19th century. The Australian model of a constitutional state that emerged from the colonial phase was one of ‘egalitarian state potency’ which implied a vastly different balance of public and private authority to the constitutions administered in Washington or Westminster in 1900.

B Public-Capital Dominance

A chief plank of the colonial socialist project was the government’s dominant role in the ownership and operation of major capital assets. The most valuable types were transport networks: overland (railways) and maritime (ports, harbours, lighthouses) infrastructure.Footnote 29 Operated as ongoing enterprises, those high-yielding public works generated a vast public-employed workforce that enjoyed high-wages and secure jobs. Novel legal arrangements, with constitutional ramifications, were made to accommodate that combination of public capital and public employment.

Railway construction initially occurred on a generous public-franchise model: a group of investors would form a ‘company’ incorporated by statute to build railways, the members of that company would wholly own the assets and future revenues, while legislation would set safety and public interest standards for the resulting infrastructure.Footnote 30 By the latter-1850s, that model had morphed into one of absolute state-ownership and operation: the property of the private company was purchased by the colonial executive, vested by statute in a non-departmental public body which operated the railways, enforcing safety and efficiency rules while extracting profit.Footnote 31 Those ‘independent statutory bodies’ would become prominent and pervasive in Australian public administration.Footnote 32

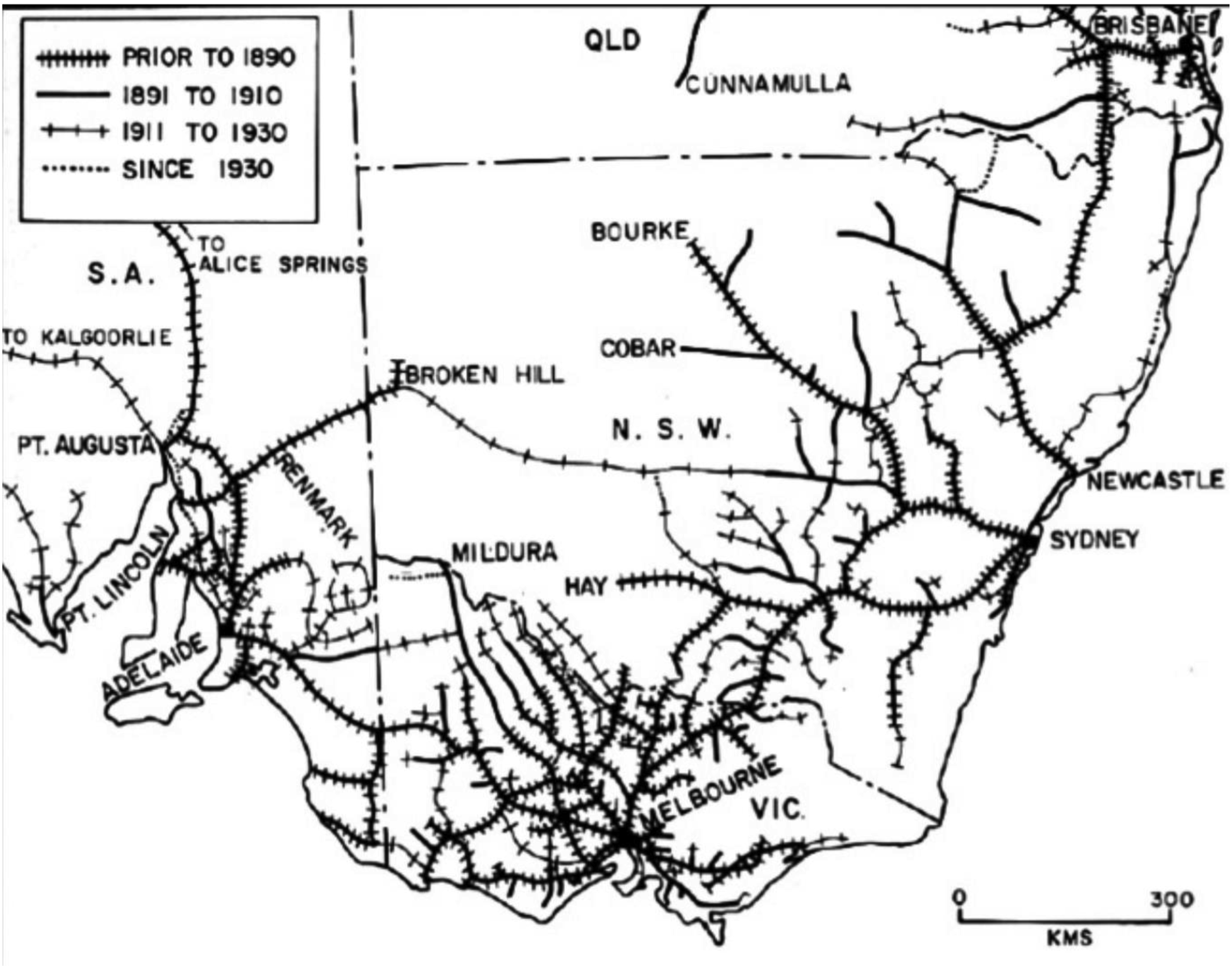

The extent of public funds necessary to purchase, expand and operate railways was enormous: between 1860 and 1900, public investment in capital stock stood at 7.6 per cent of GDP, 43 per cent of which was devoted to railway construction.Footnote 33 Railways were highly profitable assets in the UK and US,Footnote 34 but in both jurisdictions their construction throughout the latter-19th century was privately funded and operated (Figure 1).Footnote 35

Figure 1. Australian overland infrastructure (regional railways and years of construction).Footnote 36

Maritime transport assets were also highly profitable which ‘[i]n contrast with Britain’ were publicly owned and operated.Footnote 37 In 19th century England,Footnote 38 lighthouses were private assets which operated on a type of syndicated insurance model: mariners paid fees to owner-operators of lighthouses to defray the cost of navigating in dangerous seas. In colonial Australia, lighthouses remained highly profitable but were owned and operated by colonial governments and fees were paid under statutory order.Footnote 39 Wharves were initially privately owned, but promptly overtaken by colonial governments which could access cheaper capital (as explained below) to service ongoing maintenance costs.Footnote 40 Alike railways, non-traditional government bodies were created by statute to administer the growing stock of maritime transport assets, legally distinct to the departments of the colonial executive government but ultimately subject to their control, endowed with broad transacting powers, wide discretions, some criminal jurisdiction and charged with fee-collection which was returnable to the colonial treasury.Footnote 41

The massive public capital owned and operated by colonial governments had hefty impacts on the colonial labour market. Between 1850 and 1890, the share of government employment in the labour market rose from 5 per cent to 12 per cent.Footnote 42 Workers running transport and communications infrastructure enjoyed high-wages which have been described as ‘institutionalised rent-seeking’ under conditions of a ‘strong labour’ movement.Footnote 43 Compared to private businesses, public enterprises were vastly larger employers,Footnote 44 allowing governments to influence ‘labour markets by taking responsibility for labour bureaus, by providing public works to support employment when times were slack, and by enacting factory legislation. The effect was to maintain a high floor to real wages and to keep labour markets tight in almost every year from 1860 to 1891’.Footnote 45 To be sure, progressive labour-regulation of the pre-Federation era was multi-causal,Footnote 46 but public employment in the government enterprises of the socialist public capital dominance was a powerful driver.

(i) Public-Credit Pooling

None of the colonial socialist infrastructure and its support for public employment could have been achieved without the use of colonial treasuries as intermediaries for foreign investors hunting for yield in the Australian colonies. So much was obvious to contemporaneous observersFootnote 47:

…the State took up the work of providing transport, and of borrowing great sums to build railways, road and bridges…Government with a partial grip of the soil and a complete grip of the land-transport, held a position too commanding for any private capitalist to challenge. It could borrow money much cheaper in London than any colonial financiers – which is mainly why it undertook the public works.

Economic historians have since agreed that offshore debt capital imported via colonial treasuries drove the colonies’ outsized public capital formation. Maddock explains that the [t]he London market...became the natural source of capital for Australian government borrowers’.Footnote 48 Colonial governments sometimes borrowed directly from the Bank of England (then still a dividend-paying private bank) but also floated their debt on the wholly private markets.Footnote 49 By the end of the 19th century, investment in Australia ‘absorbed a high proportion, of the order of a third to a half, of total net British lending overseas’.Footnote 50 By 1890, the colonial governments were acting in concert as a debtors’ union, all using the same investment bank ‘Nivison & Co.’ which, by 1890, ‘came to act as agent for all Australian governments, eliminating contention and the need for external underwriting’.Footnote 51 This ‘superior ability of the [colonial] government[s] to raise capital, particularly in London… prompted the original transfer’ of major infrastructure to public ownership in the latter-19th century.Footnote 52

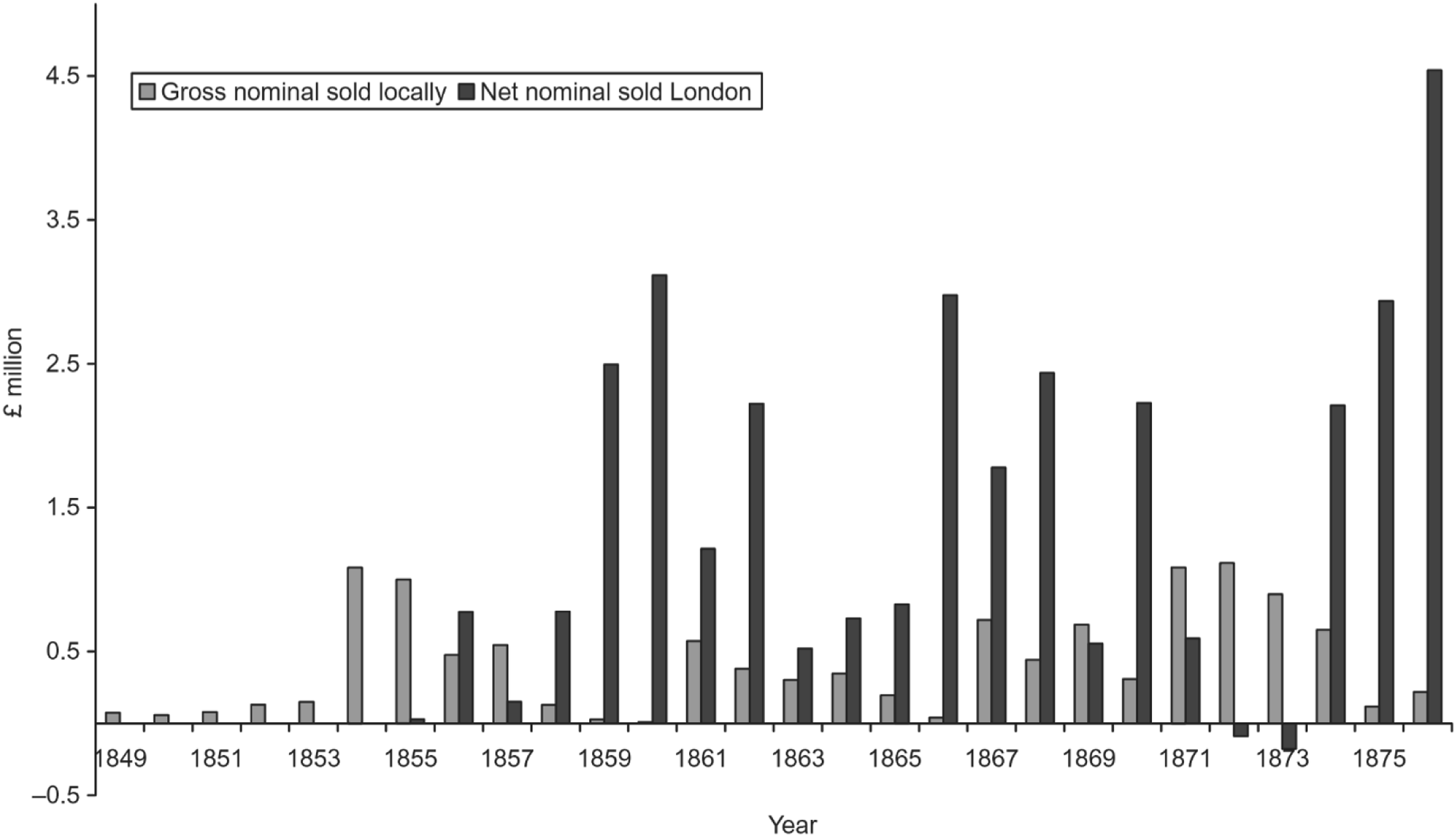

Borrowing on the London capital market vastly overshadowed local debt issues Figure 2Footnote 53:

Figure 2. Nominal values of colonial government debentures sold in Australia and London, 1849-76(£m).

London investors were hungry for colonial yields for two (related) reasons: high rewards and low risks. Rewards were high because railways, ports and lighthouses were highly profitable, irrespective of public ownership.Footnote 54 More importantly, North Atlantic investors saw the Australian colonies as low riskFootnote 55: risk premia between 1870 and 1913 averaged 0.56 per cent on Australian colonial debt compared to 0.83 per cent in South Africa, 1.73 per cent in Argentina and 1.94 per cent in Japan.Footnote 56 Structural features of colonial governments significantly reduced their credit-risk. Public treasury scoping of infrastructure projects provided ‘[l]ong-term planning of government capital formation’ and parliamentary processes of supply and appropriation provided ‘long-term authorisation of expenditures’.Footnote 57 ‘Governments themselves invested’ in public accounts and audit institutions which supplied investors with ‘systematic information gathering and publication’ of government-run assets.Footnote 58 British Governors oversaw public works with a ‘watchful eye’.Footnote 59 Each of these structural feature neutralised the (otherwise hefty) default risk premium, given that ‘[b]y 1890 the Australian colonists had accumulated more public debt per capita than residents of any other country or colony in the world’.Footnote 60

In terms of constitutional structure, there were two major elements of investor protection that off-set the crushingly large debt burden. The first was risk pooling through statutory borrowing: ‘bundling claims against a broad range of assets’ leading to ‘economies of scale and scope’Footnote 61 which thrilled London’s investor community.Footnote 62 One type of credit pooling was directly imported from the UK. The colonial constitutions of the 1850s followed the British precedent of consolidating fiscal revenues as security for loans of private financiers.Footnote 63 Under that system, colonial customs and excise receipts flowed into ‘consolidated funds’ which were collateral pools for offshore debtholdersFootnote 64: thus the local reliance on indirect taxes (customs/excise) supported inward debt-capital investment.

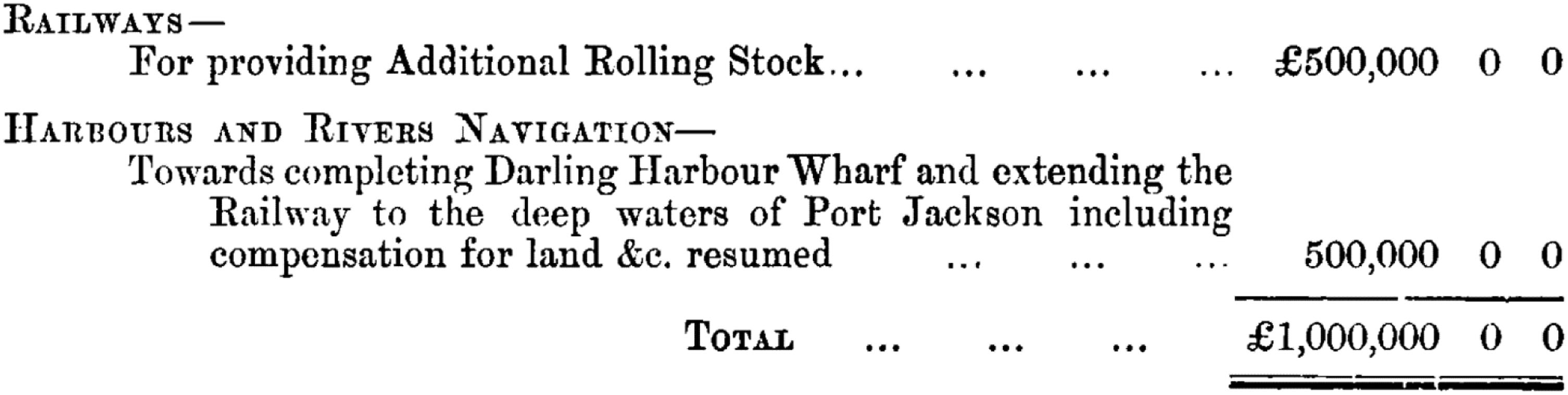

Another type of colonial credit pooling was novel and focused explicitly on pooling capital assets, rather than fiscal receipts. Colonial parliaments enacted separate Loan Acts to raise project-finance for capital works which linked specific bond-lines to specific public assets. A representative example is the Public Works Loan Act 1881 (NSW) 45 Vict, c 22 which authorised ‘the Government to borrow’ £1million ‘for the following several purposes’Footnote 65:

The statute tailored the securities tendered to offshore investors, providing for the sale of ‘debentures…in the form of funded stock in…London’ and transfer of the debentures to be recorded ‘in accordance with regulations made or approved by the Committee of the [London] Stock Exchange or adopted by the Bank of England’.Footnote 66 Funds received from bond sales were ‘to be placed to a separate credit to be called ‘The General Loan Account’ and withdrawals could only occur with permission of the Governor (appointed by and responsible to, London).Footnote 67

The second element of foreign-investor protection was a highly innovative system of public liability rules which largely neutralised sovereign risk for foreign investors in colonial public capital. At common law,Footnote 68 the Crown was immune from suit subject to a discretionary action (‘the petition of right’) which guaranteed a disappointed counter-party no financial redress.Footnote 69 Applying this system to the ‘Crown’ which had dispossessed the landmass of Australia presented an obvious block to foreign investment: lending the colonial Crown funds for project-finance risked giving money to an entity which could neither be sued for failing to construct and operate the public asset or sued for default of the debt.Footnote 70

The solution to that problem of investor-risk in the colonial socialist project was to create a public-liability system that ensured colonial governments would be liable for non-performance of commercial obligations though the ordinary judicial process, supervised by British authorities. From the 1860s, ‘claims against the government’ legislation was enacted which applied standard property law concepts to colonial governments.Footnote 71 South Australia and NSW passed the first of such legislation in the 1850s,Footnote 72 which empowered the Governor to approve actions against the ‘Colonial Government’Footnote 73: sidestepping unresolved questions of the ‘Crown’s’ legal personality and amenability to suit.Footnote 74 Both South Australian and New South Wales Claims Against the Government Acts also ensured that judgment debts against colonial government could be easily paid,Footnote 75 another unclear matter under British law.Footnote 76 Additionally, colonial governments could reassure investors that ‘claims against them could be pursued through to the Privy Council’Footnote 77: reserving ultimate decisions on sovereign-risk for political and legal authorities in London.Footnote 78

(ii) Public-Social Insurance

The public capital dominance and public-credit pooling of the colonial socialist period were not driven by utopian social policy, but capital efficiency. Social insurance, in the form of universal old-age pensions, represented a divergence from that model. Even the sceptical and doctrinaire Métin described the first Australian old-age pension as ‘really tending towards socialism’.Footnote 79 Alongside private pension arrangements,Footnote 80 the UK government had paid pensions for centuries to holders of aristocratic/venal offices,Footnote 81 while the US government had expanded pension coverage to soldiers and their families. Latter-19th century proposals within the British Empire for old-age pensions were largely based on contributory-models were which really forms of government mandated ‘thrift’, requiring minimum working years and ‘good character’ standards before ‘deserving poor’ could access retirement benefits, often mostly below subsistence levels.Footnote 82 The first step away from that parsimonious attitude to life-cycle dependence insurance was taken in New Zealand via Old-age Pensions Act 1898 (NZ) which created a scheme for universal non-contributory old-age pensions.Footnote 83 That relatively generous scheme formed the basis of Australian development of universal invalid and old-age pensions.Footnote 84

By 1900, two types of pensions could be drawn in Australia, both associated with colonial socialist conditions: pensions related to public sector employment and universal old-age pensions. Public sector employment itself provided a type of pension, simply on account of the wages and retirement benefits payable to the bulk of public sector works. Such programs are notable in size from the 1890s. An example appears in the Victorian Railways Commissioners Act 1883 (Vic) which required that ‘every officer and employee holding office in the Railway Department at the time of the passing of this Act shall be entitled to compensation or retiring allowance’.Footnote 85 Public employment also served as a proxy for unemployment insuranceFootnote 86:

New South Wales, like every other Australian Colony, is annually troubled and burthened by an ‘unemployed’ difficulty. Every winter the Government is under the unsatisfactory necessity to provide, or rather to create, more or less useless occupations for large numbers of men, as an excuse for the payment of money to keep them and their families from starvation.

In addition to manipulating the government’s labour-wage bargain, a universal, non-contributory, old-age pension was proposed in NSW on explicitly humanitarian grounds. The parliamentary report which recommended the legislation stated the basic position: ‘pension should be granted as a right, not as charity, and it should not be seen as in any way humiliating to those who receive it’.Footnote 87 It rejected British contributory models (which penalised the poor and women) and drew on Continental European practice for inspiration.Footnote 88 Writing in 1902, Reeves describes the broad acceptance of those principles in the parliamentary debate on Australia’s first universal pension legislation. In the Lower House, ‘[r]ightly or wrongly, national thrift was not a word to conjure with in Sydney…Of direct opposition there was almost none. The Upper House, if not enthusiastic, was benevolent. Seldom, indeed, has a striking, novel, and expensive social reform been adopted with so little hesitation and amid so harmonious a chorus of blessings and good wishes’.Footnote 89 Funding for the scheme was recommended via mining royalties and profits from agricultural use of Crown Lands ‘with the State, instead of private individuals, as a progressive landlord’.Footnote 90

The NSW pension was vastly expensive and generous relative to its period. It contained racist exclusions (‘asiatics’ and ‘indigenous natives’) but otherwise male and female residents of NSW for 25 years were eligible by default once they turned 65.Footnote 91 Early-life criminal offences were not disqualifications, nor was persistent unemployment.Footnote 92 The base quantum of £26 would have covered average annual spending on food, beverages, dwelling, fuel/light, entertainment and medical attendance.Footnote 93 People receiving private pensions were ineligible for pension and the base quantum was reduced by other income sources, as well as large property holdings.Footnote 94 Payments under the Act were protected from the vicissitudes of the political process by standing appropriation.Footnote 95 Victoria quickly followed with its own Claims for Old-Age Pensions Act 1900 (Vic), which largely mimicked the NSW legislation.Footnote 96 The absence of institutional resistance to those universal pension programs was striking, given that attempts to implement far less generous programs in the UK caused the constitutional crises which fundamentally remodelled the UK Parliament through the Parliament Act 1911,Footnote 97 as is discussed below in Part III.

(iii) Egalitarian State Potency

The Australian model of the constitutional state which emerges from the colonial socialist period is distinct in the Anglophone world. Executive governments were large business-operating entities which used their size and scale to acquire bulk-financing on international debt-capital markets, while providing vast public employment and generous social insurance. Legislatures innovated to support the potent executive with novel forms of public office, smoothed disputes in the public labour markets with conciliative industrial institutions and backstopped investor confidence by enacting innovative public liability regimes. Judiciaries applied the traditional common law, but accepted parliamentary innovations, and were the outpost of an Imperial system of investor protection which ensured executives’ access to cheap foreign credit despite large deficits.

Those features of the colonial constitutional state supported a political economy that rotated around a dominant public sector with strong compassionate tendencies: compared to the UK and US, they were markedly more ‘egalitarian’.Footnote 98 Importantly, however, colonial socialism was not driven by class struggle or ideas of common humanity. Indeed, European socialists commented that ‘Australasia has contributed little to social philosophy but she has gone further than any other land whatever along the road of social experiment’.Footnote 99

'On both sides equally, the poverty of theoretical notions is astonishing to anyone accustomed to European polemics. One hears from the employers simply affirmations of inflexible resistance to change, based on the defence of their profits. There is no argument whatsoever, only declarations of war….On the other side theoretical arguments are no better, or rather, they simply do not exist: people ignore or run away from them. The word ‘socialist’, pleasing to many European reformers because of its philosophical and general connotations, displeases and perturbs Australasian workers by its very amplitude. One of them whom I asked to sum up his programme for me replied: ‘My programme! Ten bob a day!’ I dare not affirm that this answer is typical, but it reflects an attitude of mind very common among Antipodean workers: they see their own interests so clearly and pursue them so persistently that they fear anything which might make their aims even seem less clear-cut.Footnote 100

The world of political ideas remained stapled to British concepts and theories, despite their infelicity.Footnote 101 This accounts for invocations of concepts like ‘liberalism’ during the Conventional Debates to describe social insurance projects which grated against contemporaneous understanding of constitutional liberalism.Footnote 102 Emerton quotes a neat illustration of that phenomenon in Barton’s interjections at the Melbourne Convention in 1898: ‘the want of foundation of accusations against this [draft Constitution] Bill on account of its alleged illiberal character’ is evidenced by such ‘very important further powers’ as ‘the power to legislate with reference to invalid and old-age pensions … [and] for the appointment of courts of conciliation and arbitration in industrial disputes which extend beyond the limits of one state’.Footnote 103 As explained in Part III below, universal old-age pensions and a state-governed wage system were both antithetical to orthodox constitutional accounts of liberalism, particularly in Britain and the US, in 1900.

Differences of opinion with European socialists were not simply rhetorical. Colonial Australians did not appear to seek radical re-distribution, but aimed for material comfort and had an investor mentality. Compared with working classes in Europe, ‘…the Australia worker…is a free spender. He does not agonize over the cost of an article or a pleasure he wants: he does not grudge any treats to his family, and so what is left over from his living expenses over goes on pleasure or on luxury goods’.Footnote 104 Additionally, surplus earnings were not solely devoted to consumption but were invested: ‘There is no evidence to support [the belief that protective legislation tends to make the worker improvident]: on the contrary savings bank deposits and payments to mutual benefit societies continue to increase every year’.Footnote 105 Thus, the potent egalitarian colonial state model produced citizens who aimed for the acquisition of property rights and the institutional foundations, particularly strong judiciaries, for their security. Nor did the colonial phase see an eradication of private entrepreneurship: to the contrary, private capital formation was enabled and boosted by the vast subsidies provided by publicly funded and owned ‘business enterprises’ which ‘[i]n terms of capitalisation and labour force…towered over private enterprise’.Footnote 106

Finally, perhaps most significantly, the colonial socialist model was not premised on ideas of human solidarity and equality. Commitment to the British Empire, its military model and its racist policies was widespread. Métin recorded an example of the contradictions this createdFootnote 107:

It is true that several labour organisations have protested recently against colonial expansion, or rather against one of its results: they complained that the financial supporters of conquest were at the same time the greatest exploiters of black labour and therefore enemies of the European worker. Even in this form the motions of protest were passed only with difficulty and were by no means unanimous.

Métin was confused by that fusion of institutional traditionalism and innovation, noting that ‘…the worker…would not like parliament to be elected on a property qualification as in Great Britain, but he manifests utterly unequivocal attachment to the monarchy and the most profound reverence for the sovereign and the royal family’.Footnote 108 Those anecdata need to be qualified by recent historical scholarship explaining the distinctiveness of pre-Federation Australian politics and constitutionalism.Footnote 109 Partlett has explained how ‘the federation movement was heavily influenced by radical Chartist ideas of a constitution that limited parliamentary power on certain fundamental principles’.Footnote 110 Those ideas led to radically different conceptions of egalitarian democratic government in Australia, compared to the Home jurisdiction: the ‘distinctive Australian tradition combined trust of parliament with a constitutional guarantee that the people could control the parliament through the vote’.Footnote 111 Blayden explains how many of those civil and political innovations were ‘institutional and regulatory in character’ and bolstered the development of a ‘political culture…. [that] can be seen as not only “majoritarian” but also “bureaucratic”’.Footnote 112 In combination with the socio-economic features of colonial socialism, those electoral and regulatory institutions ‘enabled a form of progressive or social liberalism to take a firm hold in the decades prior to Federation’.Footnote 113 While the political thought of pre-Federation Australia is still being explored, it is clear that the major break from imperial fidelity did not occur until well into the 20th century: confirming the unique ‘zero-doctrine’ character of Australian colonial socialism.

C Part II: Nationalising Colonial Socialism

The Constitution achieved economies of scale not just by creating a ‘single market’ (eradicating inter-state economic competition), but also by ‘nationalising’ the unique legal features of the colonial socialist state. Legislative power was explicitly conferred on the Commonwealth to engage in the development of overland and maritime public transport assets, and to provide invalid and old-age pensions. Exactly how those substantive projects could be funded was unsettled. General fiscal power (to tax, spend and borrow) was given to the Commonwealth but its capacity to invest profits from public capital for infrastructure and social insurance programs was unclear due to compromises made during drafting negotiations. Matters came to a head in the Surplus Revenue Case where the High Court confirmed the Commonwealth’s arguments that it should have the same financial capacity as the colonial socialist governments, a conclusion accepted by the constituent power through a subsequent referendum.Footnote 114 Thereby, the colonial socialist model of egalitarian state potency was federalised.

(i) Scale-Effects of Federation

Capacity to own and operate the vast public capital built by the colonies was explicitly given to the Commonwealth. Ownership of the most valuable public assets (railways) was not transferred outright, but the Commonwealth was given power to acquire those assets for fair value with the ‘consent’ of their State-government owners.Footnote 115 Few States chose divestment, but the framers’ choice to provide that bespoke legislative power shows that the national government was built with capacity to own and operate the vast overland transport networks built by the colonial governments. More importantly, the Commonwealth was given explicit legislative power to ‘construct’ and ‘extend’ railways on the Australian landmassFootnote 116: providing textual proof-positive that the federal government was designed to carry on the public-capital dominance of the colonial states.

Profitable maritime and communications assets were simply ‘transferred’ outright to the Commonwealth. State ‘departments’ responsible for ‘[p]osts, telegraphs, and telephones’ and ‘lighthouses, lightships, beacons, and buoys’ were transferred to the Commonwealth.Footnote 117 Following that departmental shift, ‘[a]ll property of the State of any kind, used exclusively in connexion with the department, shall become vested in the Commonwealth’ and any property used for a mixed purpose could be compulsorily acquired for a value fixed by the federal parliament.Footnote 118 The Commonwealth was also given explicit power to fix conditions in markets in which public capital dominated. Special provisions were inserted to clarify that Commonwealth legislative power over ‘trade and commerce’ encompassed public-sector operated overland and maritime transport infrastructure.Footnote 119 Power over those assets can be understood through the lens of ‘trade and commerce’ not simply because they facilitated private trade but also because they were yield-generating for their government owners.Footnote 120

Notoriously, the Commonwealth obtained power to regulate labour markets, and the first serious disputes regarding the conciliation and arbitration power concerned government employees operating capital assets owned by State governments.Footnote 121 Finally, the Commonwealth was empowered to provide public-social insurance on a national level. Authority to legislate for ‘[i]nvalid and old-age pensions’ was an anomalous provision within the national constitutions of the Anglophone world in 1900.Footnote 122 It permitted the new federal polity to provide public insurance against life-cycle dependency events to an entire nation.Footnote 123

In each of those cases, substantive legal power was given to the Commonwealth to continue the colonial socialist modes of statehood operated by the defunct colonies, but the financial plumbing to support the Commonwealth’s action as an owner-operator of public capital and social insurance provider was far less clear.

(ii) Nation-wide Credit-Pooling

Although financial pundits emphasised the beneficial scale-effects of Federation on Commonwealth bond prices,Footnote 124 foreign inward investment costs for the Commonwealth would be presumptively higher than the colonies unless the new federal polity could re-create the structural features of the colonial socialist phase that neutralised risk-premia for offshore investors. Explicit legislative power was conferred to ‘borrow money on the public credit of the Commonwealth’,Footnote 125 but the Constitution provided no clear machinery to empower the new federal polity to achieve the same public-credit status as the colonial treasuries. Importantly, while a ‘consolidated revenue fund’ was created by s 81, it was not automatically charged with debt-servicing costs: a major divergence from the investor-protecting practice of the colonial constitutions,Footnote 126 the British North America Act 1867 and the original UK legislation which stapled debt-servicing costs to national tax revenue.Footnote 127

Basic elements of investor protection were, however, entrenched. Power was conferred to make ‘laws conferring rights to proceed against the Commonwealth’Footnote 128 which was exercised through the Claims Against the Commonwealth Act 1902 (Cth) which copied the innovative colonial models and required that judgment be given ‘as in an ordinary case between subject and subject’.Footnote 129 That temporary legislation was required to ensure that Commonwealth operators of communications infrastructure could be sued and expired upon the enactment of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).Footnote 130 Foreign investors’ offshore rights, in the capital markets that mattered, remained protected by the Privy Council’s oversight of the Australian judiciary.Footnote 131 The controversial qualifications to Australia’s judicial sovereignty to ensure that (limited exception aside) ‘this Constitution shall not impair any right which the Queen may be pleased to exercise by virtue of Her Royal prerogative to grant special leave of appeal from the High Court to Her Majesty in Council’ were (notoriously) inserted against the wishes of local Australian framers, due to extensive ‘lobbying’Footnote 132 in Australia and London by business groups wishing to avoid a devaluation of their colonial assets.Footnote 133

Notwithstanding those investor protections, two major ambiguities remained in the Commonwealth’s financial potency.

First, the terms on which the Commonwealth could finance its owner-operator responsibilities were radically uncertain due to the nebulous legal resolution of ‘the financial question’.Footnote 134 As a customs union, Federation would make the colonies’ populations richer through fiscal harmonisation and tariff liberalisationFootnote 135: hence the transferral of customs and excise taxes to the Commonwealth and prohibitions on differential taxation in the Constitution.Footnote 136 That model caused an acute problem for colonies which relied on indirect taxes to protect their domestic industry, as cash-pools for daily expenditure and collateral pools for creditors.Footnote 137 Federation required politicians to make inter-temporally rational decisions: in the short-run State governments would lose their financial advantages; but, in the long-run, their inhabitants would become richer. Solving that risk/reward calculation nearly destroyed the federal project but the insertion of a complex set of revenue-sharing provisions allowed the drafting process to conclude. They functioned in stages.Footnote 138 First, the Commonwealth was clearly obliged to pay 75 per cent of its ‘net revenue’ from customs and excise taxes to the States until 1910.Footnote 139 Secondly, from 1901-1905, the Commonwealth was required to create a federal balance sheet which credited States with all revenues collected inside that State and debited States for the Commonwealth’s costs in operating transferred colonial departments and the ‘State’s per capita share of other Commonwealth expenditure’: the ‘balance’ was to be paid to each State.Footnote 140 Thirdly, and most problematically, from 1906-onwards, the Constitution provided that ‘the Parliament may provide, on such basis as it deems fair, for the monthly payment to the several State of all surplus revenue of the Commonwealth’.Footnote 141 None of the relevant terms (‘may provide’, ‘deems fair’, ‘surplus revenue’) were clearly defined in the Constitution or the Convention Debates. In that way, the ‘surplus revenue’ provision provided no fixed guidance for any government in the Federation regarding how the fiscal revenue could lawfully be distributed. Exactly how and why the Commonwealth would operate valuable public assets and social insurance programs if it was required to remit all operating profits to the States was unclear.Footnote 142

The second financial ambiguity concerned access to sovereign debt. The new Commonwealth would be a competitor against the States in London’s capital markets and it would have a far-weaker bargaining position due to its smaller collateral base (even with transferral of maritime and communications infrastructure) and limited fiscal power. Additionally, as a new and national government it would not enjoy the reflexively low-risk premium given to dependant-colonies,Footnote 143 and had no established machinery for sovereign debt management. Those weaknesses in the federal polity’s borrowing capacity can be seen in the Commonwealth’s first major sovereign debt experiment: the Naval Loan Act 1909 (Cth). This odd piece of legislation followed part of the colonial precedents by expressly authorising flotation in London and specifically appropriating the loan proceeds to ‘the initial cost of a Fleet Unit for the purpose of the Naval Defence of the Commonwealth’.Footnote 144 The Act diverged from the colonial practice in other ways which revealed the Commonwealth’s weakness as a sovereign borrower, most visibly in its (bizarrely strict) offshore-investor payment clause.Footnote 145 To further convince investors of its credit, the Act created a sinking fund to be credited annually with 5 per cent of outstanding debt until the loan matured, with proceeds paid personally to officers of the House of Representatives, the Senate and the Executive to be held on trust.Footnote 146 The most revealing concession to the Commonwealth’s shaky credit was the debt’s interest rate: set by the Act at 3.5 per cent, which was 0.5 per cent higher than NSW bonds. One reason for the Commonwealth’s worse credit was explained by the Treasurer on the Bill’s reading: compared to the former-colonies, the Commonwealth had not yet built up a portfolio of yield-generating assets to collateralise its debt.Footnote 147

The Commonwealth’s uncertain balance-sheet position created obvious conflicts with the recognition, elsewhere in the text, of the potent egalitarian state model. The High Court resolved the first major conflict resoundingly in favour of financial empowerment in the Surplus Revenue Case Footnote 148 thereby setting the course for the nationalisation of the colonial socialist heritage.

(iii) Judicial Power and Socialism without Doctrine

The Surplus Revenue Case has largely been analysed as a simple dispute between the Commonwealth and the States. On that account, the Commonwealth sought to hide its surplus revenue from the States by squirreling it away in trust accounts,Footnote 149 and the High Court, without strong reasons, endorsed that behaviour, setting the ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’ in train.Footnote 150 While the case certainly did empower the Commonwealth at the expense of the States, it has a significance beyond internecine federal conflict. The Surplus Revenue Case resolved critical problems with translating colonial socialist technique to the new federal polity, the role of the judiciary in solving those problems and confirmed, via the referendum which confirmed its result, support from the constituent power for the nationalisation of the potent egalitarian state model developed pre-Federation.

The Surplus Revenue Case was triggered by the legislative creation of a system of public investment funds for public capital works and social insurance.Footnote 151 A set of ‘Trust Accounts’ was created by the Audit Act 1906 (Cth) for the purposes of building defence infrastructure, paying pensions and facilitating the Commonwealth’s domestic and international payments. Trust accounts could be credited with money voted by parliament, but also with revenue generated by assets built using the trust funds. Money in trust accounts could only be spent on the listed purpose and the Treasurer could invest any positive balances in fixed income securities or bank accounts. Those trust funds were national investment accounts for infrastructure and social insurance: they contained accumulations of fiscal receipts for future investment projects.

Eighteen-months later, the Commonwealth parliament enacted the world’s first national universal (non-contributory) invalid and old-age pension legislationFootnote 152: replicating the progressive NSW model by providing public social insurance to people over 65 years or ‘permanently incapacitated for work by reason of accident…or by being an invalid’.Footnote 153 Payment of pensions would occur out of money ‘appropriated by Parliament for the purpose’.Footnote 154 On the same day, legislation authorised payment of £750,000 out of consolidated revenue, and appropriation, for the purpose of the ‘Trust Account…known as the Invalid and Old-age Pension Fund…for Invalid and Old-age Pensions’.Footnote 155 Later that day, a further Act authorised payment and appropriation of £250,000 ‘for the purposes of the Trust Account known as the Harbor and Coastal Defence (Naval) Account…for Harbor and Coastal Defence (Naval) purposes’.Footnote 156 Three days later, the Surplus Revenue Act 1908 (Cth) entered into force, providing that credits in those pension and infrastructure trust ‘shall be deemed to be [Commonwealth] expenditure’Footnote 157 and their underlying appropriation ‘shall not lapse nor be deemed to have lapsed at the close of the financial year for the service of which it was made’.Footnote 158 That legislation was designed to exploit the textual ambiguity in s 94 (‘the Parliament may provide, on such basis as it deems fair, for the monthly payment to the several State of all surplus revenue of the Commonwealth.’) by ‘providing’ that fiscal receipts held in trust were ‘debited’ from the amount of annual ‘revenue’ for calculation of a ‘surplus’.

NSW sued the Commonwealth, contending that the Constitution prevented the federal government from accumulating fiscal receipts for future public capital formation and social insurance projects. Formally, the case turned on whether public money paid from the Treasury under a statutory appropriation into a statutory trust account had been ‘expended’Footnote 159 and could be excluded from any ‘surplus revenue’.Footnote 160 NSW argued, by analogy with private sector accounting practices,Footnote 161 that money which remained inside the public sector at the end of a financial reporting cycle had, definitionally, not been ‘expended’ and was ‘surplus’. The State also invoked supposed constitutive intentions, alleging that ‘[t]he States did not intend that large spending powers should be given to the Commonwealth’ and that ‘[n]o power to accumulate revenue for several years was intended to be given’.Footnote 162

The Commonwealth countered that it was given unique powers by the Constitution which ‘cannot be effectively executed unless there is also a power to set aside large sums of money for future expenditure’: offering as examples ‘bounties, borrowing, defence, State banking, and immigration’.Footnote 163 More importantly, the Commonwealth argued that ‘before Federation’ colonial governments created statutory ‘trust accounts’ for investment projects treated funds in statutory trusts ‘as expenditure’.Footnote 164 The Commonwealth used that colonial socialist heritage as the foundation for their preferred interpretation of s 94 (money is ‘expended’ when ‘appropriated’): ‘that is a natural meaning of the word “ expenditure” in connection with Government accounts and the establishment of a system of constitutional government’.Footnote 165 The Commonwealth argued that ‘the Parliament is invested with the same powers of appropriation for specific purposes as are the State Parliaments in respect of their revenue’Footnote 166: thus making a claim to having inherited the same state model, at least regarding financial potency, from the colonial governments. Ultimately, the Commonwealth argued that accumulation of fiscal receipts were necessary to develop, operate and own large capital assets and social insurance schemes.

It was clear during oral argument that the States’ private-sector accounting argument faced strong headwinds. Justice O’Connor immediately raised the quandary they posed for the federal government’s capacity to develop a public capital base: ‘In your view, if the Parliament desires to spend £2,000,000 on warships and not to pay for them out of one year’s revenue, it could not before purchasing set aside a yearly sum out of revenue until the amount was made up, but would have to borrow the money?’Footnote 167 Plaintiff’s counsel’s response indicated the farcical consequences of its argument ‘[e]ither that or pay in instalments’.Footnote 168

The High Court’s unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the system of national investment established through the ‘trust account’ legislation. The case is often cited for simple propositions that once ‘appropriated’ by legislation, Commonwealth money stood outside the concept of ‘surplus’.Footnote 169 While a technically correct summary of the case, none of the judges rested their reasoning on that abstract propositionFootnote 170: all judges reinforced their reasoning by reference, expressly or implied, to the features of the colonial socialist state.

Central to Griffith CJ’s reasons (the most austere of the Court) was his understanding that government’s core functions include long-term enterprises involving extensive financial obligations: ‘the operations of government are continuous and extend over long periods…the word ‘surplus’, used in such a connection, must therefore be read in a sense which recognizes this condition and gives effect to it’.Footnote 171 Justice O’Connor more explicitly linked the need for an expansive meaning of ‘surplus’, and ‘expenditure’, to a model of constitutional government which was (both) a major actor in the financial system and involved in public investment. In rejecting the State’s argument, he saidFootnote 172:

The impossibility of carrying on the operations of government under such a system are too obvious to need further comment, and the interpretation which would lead to that result must be rejected… it is only by adopting the wider meaning … [which is] natural and appropriate in adjusting financial relations between Commonwealth and States under a system of parliamentary government, that full effect can be given to the Constitution…the Commonwealth is entitled in accordance with well recognized methods of public finance to accumulate revenue to be paid out later in the execution of some Commonwealth power.

The ‘well recognized methods of public finance’ and the ‘system of parliamentary government’ must be references to the colonial legislation concerning public works and social insurance legislation raised by the Commonwealth’s counsel in argument.Footnote 173

Other judges relied explicitly invoked the need to effectuate the Commonwealth’s substantive legislative powers, particularly concerning infrastructure development and debt finance. Justice Higgins explicitly invoked the impossibility of constructing major public capital if the ‘trust account’ system were invalidated: ‘If this claim is right, the Commonwealth Parliament has no power to provide out of its revenue in fat months for expenditure which it foresees in the near future say for naval defence, or for financial assistance to a State (under s 96 of the Constitution); and the power of the Commonwealth Treasurer in making financial arrangements must be grievously crippled’.Footnote 174 The latter reference to the Treasurer’s power to make ‘financial arrangements’ would have included the power to acquire debt capital, raised in argument by the Commonwealth.Footnote 175 That imposing a strict operational-cost limitation on the Commonwealth would ‘grievously cripple’ such a power, again, only makes sense when one recalls the enormous role of foreign investor credit arrangements in building the version of Australian statehood that emerged from the colonial phase. Justice Barton adverted to the same consideration when reasoning that the ‘the construction contended for is plainly unreasonable…it would have the effect of dislocating the whole financial system… Are the hands of the Commonwealth to be tied thus against the interests of all concerned’.Footnote 176

Justice Isaacs’ reasons brought each of those features together. From the outset of his reasons, Isaacs J emphasised the link between maintaining a rational system of investment funds and the Commonwealth’s role as a developer of public capital:

[s]urplus revenue means free revenue, that is, not marked out by Parliament as required by the Commonwealth for carrying out purposes lawfully resolved upon. In this instance Parliament, having thought it necessary that Harbor and Coastal Naval Defences should be undertaken for which £250,000 would or might be required, a perfectly lawful purpose.Footnote 177

He then relied heavily on an expansive understanding of constitutional statehood to reject the State’s argument explaining that it would undercut the ‘creation and maintenance of the Commonwealth’ as a ‘scheme of government…proceeding for the effectuation of its purposes on traditional lines of parliamentary and responsible government’ which included those hallmarks of colonial socialism: public-credit pooling (acquiring ‘debt’ and paying ‘a judgment’) and public social insurance (‘an Act conferring bounties or old-age pensions’).Footnote 178

Ultimately, Isaacs J rested his decision on a view of the Constitution that permitted the Commonwealth the same economic capacity as recently transformed colonial governmentsFootnote 179:

Undertakings decided upon by the Commonwealth may from their nature require deliberation as to final form, and if, before actual commitment to details, time for consideration is taken, can it reasonably be said, that although the cost is fixed, and the required money expressly appropriated to the purpose, that money is still in the eye of the law ‘surplus revenue’ distributable perforce among the States? This would leave the Commonwealth with its purpose bare and barren, and incapable of fulfilment until fresh means were sought. It is no answer to say other moneys would probably reach the Treasury, because they may be needed for other purposes. The argument, if acceded to, would probably either drive the Commonwealth to hasty and ill-considered action so as to actually disburse its revenue, in satisfaction of its purposes, or else compel it to find fresh ways and means, possibly burdensome.

With perfect hindsight the Surplus Revenue Case certainly facilitated the growth of Commonwealth government power over the States.Footnote 180 Viewed in its period, it performed an equally momentous but less partisan function: it confirmed that the new federal polity would have the same financial capacities which were integral to pre-Federation colonial socialist models. What Saunders has described as the ‘emergent link between borrowing and revenue distribution’ was patent in the dual proposals for constitutional alteration presented to electors in the 1910 referendum.Footnote 181 Two amendments were proposed: the first to permit the Commonwealth to assume State Debts (incurred post-Federation); and the second to un-wind the Court’s decision in the Surplus Revenue Case. The first proposal passed and the second was rejected, securing the Commonwealth with the full panoply of financial powers necessary to implement the potent egalitarian constitutional model developed in the colonial phase.

D Part III: Australian Constitutionalism and Egalitarian State Potency

From the conclusion of the surplus revenue referendum, it was clear that the model of egalitarian state potency built during the colonial phase could be implemented on a national level. The degree to which that model differed from Australia’s North Atlantic constitutional ancestors, the UK and USA, was revealed over the next two decades. Attempts to implement policies and institutions that fitted comfortably within the Australian traditions provoked enormous political conflicts and led to constitutional transformations in Westminster and Washington. Between 1911 and 1935, the House of Lords was stripped of its legislative power over public finance and the US constitutional tradition was significantly ‘re-founded’ in the face of social insurance and public works programs. On both sides of the North Atlantic, similar doctrinal arguments and institutional techniques were in play: all of which were alien to the contemporaneous Australian experience. This concluding part presents a provisional sketch of that divergence of Washminster and Australian constitutional lineages and flags a set of topics for future academic inquiry.

(i) The People’s Budget and Westminster Constitutionalism

The British constitution was transformed in the 20th century’s first decade by the violent parliamentary dispute that arose from legislation designed to fund social insurance (old-age pensions) and public capital (naval infrastructure). Between 1908 and 1910, British Cabinets formulated plans to provide universal old-age pensions and win a growing arms race, to be funded by significant increases in taxation in the form of land-value taxes.Footnote 182 Compared to the generosity of contemporaneous Australian public sector expansions, the proposals contained in the ‘People’s Budget’ were modest, but they were vetoed by business and aristocratic elites in the House of Lords on the basis of conflict with liberal values of private property protection.Footnote 183

The inter-cameral conflict was resolved by the Cabinet inviting the King to re-constitute the Lords with more progressive members until the upper house passed the gridlocked social insurance and public works legislation. Rather than being inundated with progressive members,Footnote 184 the Lords agreeing to enact the Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo 5 c 13). The preamble of that Act recited that ‘whereas it is intended to substitute for the House of Lords as it at present exists a Second Chamber constituted on a popular instead of hereditary basis, but such substitution cannot be immediately brought into operation’. The first operative provision of the Act striped the un-elected Lords of their legislative power over money bills:

(1) If a Money Bill, having been passed by the House of Commons, and sent up to the House of Lords at least one month before the end of the session, is not passed by the…Lords without amendment within one month after it is so sent up to that House, the Bill shall, unless the House of Commons direct to the contrary, be presented to His majesty and become an Act of Parliament on the Royal Assent being signified notwithstanding that the House of Lords have not consented to the Bill.Footnote 185

Thereafter, the centuries old Westminster Parliament was reduced, when it mattered, to a unicameral body.

The vociferous institutional reactions to the People’s Budget appear inexplicable, until one reviews the orthodox constitutional ideology of the period. Dicey, the unrivalled constitutional theorist of British laissez faire,Footnote 186 viewed later-19th century political claims for an economically interventionist and re-distributive government as the end-point on a constitutional journey from liberalism to ‘collectivism’ or ‘socialism’. He did not argue that such a development was desirable, preferring to depict progressive taxation,Footnote 187 trade-unionism and old-age pensions as types of ‘evil’Footnote 188: the latter being a particularly odious type of society-wide institutionalised corruption.Footnote 189 Those ‘definite socialistic formulas’Footnote 190 were objectionable on classic liberal grounds:

The beneficial effect of State intervention, especially in the form of legislation, is direct, immediate, and, so to speak, visible, whilst its evil effects are gradual and indirect, and lie out of sight….State inspectors may be incompetent, careless, or even occasionally corrupt, and that public confidence in inspection, which must be imperfect, tends to make the very class of persons whom it is meant to protect negligent in taking due measures for their own protection; few are those who realise the undeniable truth that State help kills self-help.Footnote 191

Those views describe an entirely alien landscape from the vantage point of Australian constitutionalism in 1911, in which it was accepted by constitutional text, judicial authority and referendum that all levels of the federal government were empowered to own and operate public assets for profit and provide progressive social insurance. Yet, Dicey is still treated as a starting point for Australian constitutional analyses and understood as expressing ‘prototypical’ views about the ‘essence’ of Australian constitutional principles.Footnote 192 Let us not forget that Dicey himself was aware of the gulf between British and Australian practice and remarked that ‘socialistic legislation and experiment have been carried to a greater length in Australia than in England’.Footnote 193 This awareness of the large gap between British and Australian constitutional practice is also evidenced, in more neutral terms, in the work of Dicey’s intellectual counter-point, FW Maitland.Footnote 194 No constitutional re-ordering was required to implement social-insurance or public capital growth programs in Australia because the constitutional model had been built to accommodate those types of state directed economic activity. What Australia achieved by consensus constitutional formulation, could only be achieved in Diceyan Britain through extreme constitutional conflict.

(ii) New Deal Re-Founding Washington Constitutionalism

A similar gulf appears between the models of US and Australian constitutionalism of the early 20th century. Again, a defining constitutional conflict (‘moment’)Footnote 195 arose from welfarist policies twinned with vast public works programs: the Supreme Court’s opposition and then capitulation to Roosevelt’s New Deal policies.

Reflecting the vastly different scale and size of economic and social disorder in 1930s America, New Deal policies were rolled-out on multiple fronts: first monetary and financial, then public works programs and finally universal social insurance.Footnote 196 At each step, constitutional obstacles appeared. The Supreme Court decision which upheld the validity of legislation suspending the Gold Standard (required to increase deficit spending to a major financing vehicle of New Deal programs, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation)Footnote 197 was a single-judge majority resolved on the basis of exigent circumstances, rather than principle.Footnote 198 The New Deal’s flagship economic regulatory legislation, the National Industrial Recovery Act,Footnote 199 was twice found invalid for impermissible delegation of legislation authority to the executive branch.Footnote 200 Alongside these staples of federal socio-economic reform, the Supreme Court also invalidated State labour protection laws and (provocatively) Roosevelt’s termination of economic officials on constitutional grounds.Footnote 201

Faced with those constitutional obstacles, Roosevelt relied on a similar institutional strategy to the British cabinet in 1911Footnote 202: he threatened to increase the number of judges on the Supreme Court until it accommodated his vision for a more economically interventionist state.Footnote 203 While academics debate whether the eponymous ‘switch in time that saved nine’ was a direct result of Roosevelt’s high-stakes threat,Footnote 204 the Court’s timely shift to an accommodative posture led to major victories for ‘second’ New Deal legislation: including, germane to the comparison with Australia, the financial framework of universal social security.Footnote 205

In comparative perspective, a striking feature of American constitutionalism in the 1930s was the immense constitutional conflict and re-structuring required to implement state-economic interventions. In addition to the political and social dimensions of New Deal conflicts, constitutional ideas were invoked as conclusive arguments against the roll-out of social insurance, public capital development and public employment. Unlike the UK, the principal constitutional impediment was not parliamentary; judicial doctrine entrenched laissez-faire conceptions of non-state intervention in economic relationships. Remodelling that doctrine required the threat of fundamental institutional transformation, creating a ‘new economic order’,Footnote 206 and, in the hindsight of latter legal scholars, effected a ‘re-founding’ of basic constitutional norms.Footnote 207

Compare those ructions with the Australian experience. A constitutional model of a potent egalitarian state accreted during the colonial phase which was then drafted into the federal constitution. The first major judicial conflict concerning that model turned on which government (federal or State) had the financial capacity to carry out long-run investment projects, not whether such projects were in toto unconstitutional. The judiciary facilitated the nationalisation of social insurance and public capital development and the electors approved that outcome through referendum. In comparison with the USA, early 20th century Australian constitutionalism was not a viable field of battle to contest the balance of states and markets because a process of popular and technical consensus approved that balance in favour of an interventionist and compassionate state with an outsized role in a market economy. That conclusion does not imply a total absence of constitutional dispute over government intervention in commercial behaviour. The early High Court did strike down federal anti-trust legislation on constitutional grounds and three referenda failed to insert explicit legislative power to regulate monopolies and oligopolies into the Constitution.Footnote 208 Even then, the Australian judiciary did not create the same absolute prohibitions as the US Supreme Court: the federal limitations in Huddart Parker left the States free to create their own anti-trust law, while the Lochner-era doctrine prohibited all arms of government from impeding on private law contracts.

(iii) Potent Egalitarian Statehood in Retrospect

If accepted as a useful analytical device, greater scholarly work would be required to understand how the model of potent egalitarian statehood developed after the Surplus Revenue Case. That exercise would require a discrete analysis of individual heads of legislative power and their limitations, in light of the features of the colonial socialist state. At a doctrinal level, it would involve the complex question of the interaction of discrete constitutional provisions with broader constitutional ideas, a process Australian lawyers understand as involving ‘implications’.Footnote 209 Hard questions arise which cannot be answered in the general case: for example, whether the meaning of ‘property’, ‘acquire’ or ‘just terms’ s 51(xxxi) is expanded or narrowed by references elsewhere in the text and structure to the Commonwealth’s power to own and operate valuable assets for public benefit?

In a more socio-legal mode, historical work would be required to examine whether and how ideas of constitutional statehood developed during the colonial socialist phase maintained their normative pull on judges and electors throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Wary of the labour-intensiveness of that process, some preliminary observations are offered on some higher-profile cases. Attorney-General (Vic) ex rel Dale v Commonwealth (the ‘Pharmaceutical Benefits Case’)Footnote 210 provides a complex case-study in authorising the Commonwealth to fund social insurance, while preventing it from regulating the commercial relationship between end-users and providers of medical service providers. Tentatively, this could be understood as consistent with the colonial socialist heritage insofar as the government was empowered to fund the provision of welfare, but prevented from substituting the market-based system. The same observation applies to Bank of New South Wales v Commonwealth (the ‘Bank Nationalisation Case’).Footnote 211 The potent egalitarian state that emerged from the colonial period relied heavily on the existence of private financial markets, and enticed them with public protections, rather than co-opting them through legislative fiat. The 1947 bank-nationalisation legislation sought to disrupt a prime mover of the colonial socialist economy: institutional debt markets. In that sense, the High Court’s constitutionalised antipathy to Chifley’s scheme was not a sharp break from the pre-Federation political economy.Footnote 212 Victoria v the Commonwealth and Hayden (the ‘AAP Case’) is also, prima facie, consistent with the potent egalitarian model insofar as it facilitates public-social insurance and public capital creation and avoids erecting judicial obstacles to those functions.Footnote 213 The hardest series of cases to fit within the model of constitutionalism that emerges from the colonial socialist phase are also the most distant in time: the Combet, Pape and Williams line of authority.Footnote 214 Those decisions draw heavily on Diceyan ideas of statehood which appear to sever them from the distinctively Australian model of statehood entrenched in the Constitution. They envision a Commonwealth executive kept ‘controlled’ by a robust Parliament, citing pre-Federation British arrangements in support and appear largely unaware of the sizeable gulf that had grown between Australia and the Home jurisdiction by the time of the Convention Debates. Although the durability of that line of doctrine is unclear,Footnote 215 its existence illustrates that future questions of Australian constitutionalism cannot be answered by simple invocation to the model of the potent egalitarian state entrenched at Federation.