Introduction

The idea that parties should fulfil their election promises, also called pledges, after an election, especially whenever they win a majority and form the government, is well established in the democratic theory and party representation literature. This principle ensures that the voters who elected this party get what they voted for and that parties can be held accountable for their promises, thus not becoming free agents without a binding contract (Schedler, Reference Schedler1998). There has been limited research into whether voters agree with this idea and attach any specific importance to promise keeping (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020; Werner, Reference Werner2019a, Reference Werner2019b). Yet, this literature has not taken into account the lessons from the voter literature making claims about important differences between various types of voters. Specifically, it is well established that voters show varying perceptions of democratic legitimacy depending on their status as government versus opposition supporters, which would suggest that this factor might shape the expectations of parties and thus affect pledge fulfilment. Bringing these literatures together means that there is a possibility that the fundamentally democratic idea of pledge fulfilment is valued or devalued by voters in predictable ways. To investigate this problem, our paper raises the following research question: Does the government or opposition status of their party affect how much citizens want governments to keep their pledges?

The rational voter perspective suggests that voters of government parties expect the latter to honour their pre‐election promises as these constituted the very basis on which these voters made their decisions. For such voters, their rationally constituted preferences coincide with a common normative expectation that promises are to be kept. Good faith and the idea of ‘pacta sunt servanda’ are fundamental normative and legal concepts shaping Western polities and dating back to Roman law. Thus, we may assume that there exists a general normative bias in favour of promise keeping. Nonetheless, this poses a dilemma for voters of the opposition, whose political preferences were very different and who might prefer the opposite outcome. Rationally speaking, they should oppose policy pledges from parties they did not support. Thus, the normative imperative of pledge fulfilment and the rational imperative of maximizing political utility are potentially in conflict. How do voters resolve this conundrum? As a result, there should be a significant difference between how voters of the government party and the opposition respond to pledge fulfilment. In this case, the central democratic mechanism of elections – that those elected should enact the pledges for which they were elected, becomes a conditional quality. This not only fails to accord with common normative democratic assumptions but also questions key ideas in democratic and party representation theories that pledge fulfilment is a universal good that is (or should be) valued by all voters in equal measure (e.g., Pierce, Reference Pierce and Miller1999; Schedler, Reference Schedler1998).

This brings us to the question about voters who have no rational expectation of their own policy preferences to be implemented. Among the voters of opposition parties, there are those who opt for parties that have never managed to gain public office and, based on public polling, are clearly not expected to enter government soon (at least not at the national level). We term these, ‘permanent opposition voters’ to distinguish them from those citizens who support parties that are only temporarily out of government. What expectations about pledge fulfilment do voters of those parties have that are unlikely ever to act on their promises? In our theory section, we put forth two contrasting arguments to explain potential differences between opposition voter types. Accordingly, permanent opposition voters may either follow rational reasoning and thus be significantly more opposed to government pledge fulfilment, or alternatively, fall back from a utilitarian to a normative stance in support of the common good.

In order to test our theory, we had the opportunity to devise a survey experiment that we conducted in Austria and Australia, two established democracies that differ fundamentally in their political institutions, party systems and culture. In our surveys, respondents, following exposure to experimental information, had to decide whether a hypothetical government in their country should act on a policy promise. Instead of investigating respondents’ reactions to a specific policy pledge, the experiment does not contain policy content but allows us to investigate the respondents’ reactions to the dilemma of deciding between the value of a pledge per se versus their opposition to the pledge‐making party. Arguing that common empirical patterns may indicate generalizable mechanisms, the experiment yielded information about whether these respondents’ decisions were influenced by the party in government, their preferred party as well as public opinion and/or the common good as identified by policy experts.

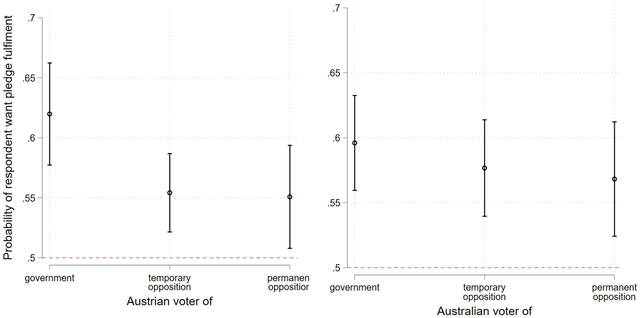

In our analysis, we find, indeed, that voters behave with respect to pledge fulfilment partially as we predicted. In both countries, respondents chose pledge fulfilment over pledge breaking with about 60 per cent probability, which shows a preference albeit not an overwhelmingly strong one. Austrian government party and opposition voters fit the rational voter explanation and thus differ in how much they value pledge fulfilment. While the opinion of experts and the public does affect this relationship, it does not significantly change it. Australian respondents, on the other hand, do not show any of these rational patterns. Further, we find no difference between temporary and permanent opposition voters in either country.

Our paper proceeds as follows: we first present our theoretical argument, which results in a set of empirical expectations that provide the specification for our survey experiment. We then introduce our two cases. Subsequently, we present in detail the experimental setup, which is followed by the analysis, the report of our findings, and our conclusions.

Theoretical discussion

Within the general theories of representative democracy, pledge fulfilment – meaning that parties enact the policies that they promise in the election campaign once they are in power – is a cornerstone of a working representative relationship between voters and parties. For voters evaluating whether parties fulfil their pledges – or worded differently: keep their election promises – it is central to holding parties accountable (Schedler, Reference Schedler1998, p. 197). This idea is also fundamental to promissory democratic representation (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003) and models of party government (e.g., Pierce, Reference Pierce and Miller1999). Empirical research into parties’ pledge fulfilment indeed show that, overall, parties in Western democracies tend to keep their promises (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017) and that voters are aware of how much their governing parties fulfil their electoral programs (Duval & Pétry, Reference Duval and Pétry2020; Thomson & Brandenburg, Reference Thomson and Brandenburg2019). Furthermore, a small but growing number of studies has shown that voters react to pledge fulfilment in experimental situations (Born et al., Reference Born, van Eck and Johannesson2018) and in country‐time specific settings (Elinder et al., Reference Elinder, Jordahl and Poutvaara2015), and that government parties can prevent losing votes by fulfilling their pledges (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020). Thus, even though pledge fulfilment might not necessarily be the most important aspect of party behaviour in the eyes of voters (Werner, Reference Werner2019a), they are generally aware and seem to care.

However, as there have only been few studies on this subject, we know little about whether this awareness and reaction of pledge fulfilment is equally distributed across all voter groups. Thomson (Reference Thomson2011) in an Irish study, and Belchior (Reference Belchior2019) in a Portuguese study, found that the party ID of voters influences their perception of pledge fulfilment. In a Swedish experiment, Naurin et al. (Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019) show that when voters decide to punish a government for broken promises, it does matter whether they agreed with the policy in question. As a result, these studies suggest that there may be an interest‐driven dynamic as to how voters interact with what is considered the normative ideal that, in a democracy, parties keep their election promises.

Departing from the focus on how parties perceive specific pledges, our contribution is to take a step back and ask whether voters agree with the normative democratic principle that pledge fulfilment is universally important – no matter who made the promise – or whether this is connected with rational voting behaviour. Thus, we draw a clear contrast between a democratic and strategic logic when testing the two central ideas about democracy and voters against each other. On the one hand, voters may apply a normative perspective to the party‐voter relationship by regarding a policy promise by a party as a normatively or morally constituted contract with voters (Nordin, Reference Nordin2014; Pierce, Reference Pierce and Miller1999; Schedler, Reference Schedler1998; Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1942). Making a policy pledge is asking a voter to place good faith in a party's stated intention in exchange for a vote. As a result, the party accepts a moral obligation which is to be honoured if and when the party is in a position to do so. As with other moral obligations, these are not necessarily subject to instrumental rationality but judged normatively. In short, pledge fulfilment may be regarded as obligatory and intrinsically preferable on moral grounds (APSA, 1950; Schedler, Reference Schedler1998; Thomassen & Schmitt, Reference Thomassen and Schmitt1997). Differently stated, democracy as a normatively constituted system requires parties to honour their promises otherwise the idea of paring parties with policy agendas and selecting between them on that basis becomes meaningless. We call voters who agree with this idea ‘normatively guided voters’ because for them (implicitly or explicitly), democracy requires good faith behaviour on the part of political actors central to which is to keep election promises.

On the other hand, the traditional view about voters is that they are rational in the sense of voting for a party which represents their interests or whose agenda they prefer. While supporting a party does not automatically mean agreement with every policy position that the party proposes, voter theories assume a general alignment of policy principles. In short, voters are assumed to be policy‐driven based on self‐interest – we call this the ‘rational voter perspective’ (Cox, Reference Cox1987; Downs, Reference Downs1957; Duverger, Reference Duverger1963; Greenberg & Shepsle, Reference Greenberg and Shepsle1987; Riker & Ordeshook, Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968; but see Edlin et al., Reference Edlin, Gelman and Kaplan2007). As long as a voter supports the party in government, this policy‐driven logic goes hand‐in‐hand with the normative principles that parties should fulfil their pledges because the promise of policy implementation constitutes the principal raison d'etre for supporting the party in the first place – so far so good.

This leads to the question of what voters prefer to happen with promises made by a party that they do not support. If these voters follow the normative democratic principle of pledge fulfilment, their non‐support of the governing party should not matter as the democratic principle is a higher good. However, from a rational policy‐driven perspective, such a voter should have a preference in the opposite direction, namely that this government party does not implement a policy that it promised because it was previously evaluated and rejected by that voter. While this rationale might matter less for valence issues, where parties’ competence is of greater importance (Green, Reference Green2007), a large part of party appeals and ideology is based on party positions that voters might support or oppose. Generally, we may assume that parties seek to distinguish themselves from their competitors by adopting either a position, or framing of a position, that is unique to them and designed to appeal to specific preferences. Rational voters that are interest‐driven and, thus, acting on policy preferences should ceteris paribus not want policies to be implemented that they as voters had opposed. Thus, their self‐interest should dictate a preference for not keeping policy promises. Empirically speaking, opposition voters are expected to show less support for the government party to keep its promise than government voters do. Here, we should clarify that policy pledges can be both positive and negative in the sense that parties may promise to do something or not to do something, such as, not sign a trade agreement or not accept refugees. One of the best‐known and consequential negative policy pledges was candidate Herbert Walker Bush's promise ‘read my lips, no new taxes’ at the 1988 Republican National Convention.Footnote 1

In any case, voters’ support for pledge fulfilment may be mitigated by additional cues, such as information provided by public opinion and the views expressed by experts (see Althaus, Reference Althaus1998, Reference Althaus2003; Bartels, Reference Bartels1996; Delli Carpini & Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Gilens, Reference Gilens2001). We focus on these two particular potential external influences on voters’ attitudes toward government promises because expert opinion and public opinion are practical implementations of the crucial democratic principles of responsiveness and responsibility (e.g., Mair, Reference Mair and Mair2014; Werner, Reference Werner2019a). There are other potential sources for external sources of information, like external shocks, yet they are not directly connected to democratic principles. In particular, we can think of a post‐election scenario in which either public opinion polls clearly indicate that implementing a promised policy would be met by widespread unpopularity or where experts strongly warn against implementation. Werner (Reference Werner2019a) presented evidence that the general idea of governmental promises has a relatively lower importance for Australians compared to the principles of responsiveness and responsibility and Werner (Reference Werner2019b) has also shown this to be unaffected by partisanship among Australian voters. In this article, we not only expand the empirical data but take this argument two steps further in that we (a) focus on the specific acts of keeping versus breaking promises as our novel independent variable and (b) take public and expert opinions as additional sources of information for voters who evaluate whether they want a pledge to be fulfilled or not.

Regarding this additional source of information, we should find specific shifts in support for promise keeping toward public opinion or expert opinion when voters allow their basic self‐interest to be influenced by such information.Footnote 2 Specifically, following the logic of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957; Aronson et al., Reference Aronson, Fried and Stone1991; Besley & Joslyn, Reference Besley and Joslyn2001), we hypothesize that rational opposition voters are likely to seek further confirmation that the government's promise is false. If they find such support in the form of public or expert opinion, their views are likely to become entrenched and their opposition to fulfilling the promise will grow stronger. Conversely, if public opinion or expert advice goes the other way, cognitive dissonance is unlikely to dissuade rational opposition voters from their objections to promise fulfilment, as they will instead choose to ignore this external information.

For rational government voters, the relationship is just the opposite. They would be even more supportive of fulfilling campaign promises if the external information turns out to be favourable, but would likely ignore contrary signals. Normatively oriented government and opposition voters would not be influenced by external signals at all, for two reasons. First, they are likely to value commitments in principle and prefer them to any other information. Second, they are more likely to evaluate both responsiveness and accountability on the basis of democratic conviction.

If we assume that citizens’ expectation about pledge fulfilment varies, the crucial next question asks which type of voters is the most likely to fall into the respective extreme category of being either normatively guided or rationally driven. Here, we turn to the group of voters that is least likely to expect to see their preferences realized because they vote for parties that are not expected to be in government. We call these citizens permanent opposition voters because they support parties that have never been in public office at the national level and are not expected to be in a position to enter government in the near future. While these voters’ support for a party's policy pledges may be rationally based, they cannot have a rational expectation of these policies to be actually implemented. In short, the rationality of their policy preference is in conflict with the rationally expected outcome of their choice. In this case, we wonder what the consequence of this conflict is. Do voters resort to a normative democratic resolution or, rather, double down on their ideologically bounded rationality? Thus, in one scenario, such voters might have a normative understanding of democracy, which favours all parties to fulfil their respective pledges even if these voters voted against them. In this case, the normative consideration strongly outweighs strategic or utilitarian preferences. As they are willing to ‘waste their vote’ and have no hope of policy influence, these voters might behave differently and should be conceptually distinguished from both government voters and voters whose party has held government office before, and whom we label ‘temporary opposition voters’. They have good reason to expect that their policy preferences will eventually be implemented.

In the other scenario, we postulate that there is an equally plausible contrasting mechanism suggesting that permanent opposition voters are a rational extension of opposition voters. Based on the same argument explaining the behaviour of opposition voters above, we would assume that permanent opposition voters are essentially willing to support non‐establishment and niche groups. Opposition voters drawn to positions out of the mainstream should thus be more willing to endorse promise breaking than those who are in temporary opposition because their own preferences are by definition extremely opposed to those represented by any possible government party.

The seemingly uncompromising stance of permanent opposition voters could therefore indicate either significant disaffection toward the political establishment or be an indication of principledness and a strongly normative orientation toward democracy and party behaviour. While there are clearly many reasons for why individuals support parties in quasi‐permanent opposition, we want to test whether there is a significantly large group that matches one of the two behavioural patterns.

If we summarize the argument and its empirical implications thus far, we expect that government and opposition voters are guided by rational decision making based on their self‐interest and thus diverge measurably on endorsing pledge fulfilment. However, we also expect to see variation among the opposition voters. This is because they may differ based on how much importance they attach to contextual clues with respect to the common good as reflected in the opinion of the public and/or experts. We also assume there to be a significant measurable difference between voters of temporary opposition parties and those respondents whose parties are permanently in opposition. We expect that the latter either are guided more by normative beliefs and thus exhibit greater support for the normative goal of pledge fulfilment (Hypothesis 3a) or they are rational extensions of temporary opposition voters and have even a lower preference for government promise keeping than that latter group (H3b). Summing up, our hypotheses may be stated as follows:

Rational and normative voter hypotheses

H1 : Government voters are more likely than opposition voters to expect pledge fulfilment from a government party.

H2 : The preferences on pledge fulfilment of rational government and opposition voters but not of normatively motivated voters are affected by public opinion and expert views.

H2a : The preference for pledge fulfilment of rational government voters is likely to strengthen if experts or the public endorse the policy pledged by the government, but remains unaffected by experts or the public rejecting the pledge.

H2b : The preference for pledge fulfilment of rational opposition voters is likely to weaken if experts or the public reject the policy pledged by the government, but remains unaffected by experts or the public endorsing the pledge.

H2c : Normatively oriented government and opposition voters will not change their preference for pledge fulfilment on the basis of expert or public opinions.

Permanent opposition hypotheses

H3a : Permanent opposition voters are more likely to endorse government party pledge fulfilment than do temporary opposition voters.

H3b : Permanent opposition voters are less likely to endorse government party pledge fulfilment than do temporary opposition voters.

Research design: A survey experiment

The empirical part of this study tests our hypotheses regarding what voters want from parties following elections. This means investigating whether voters of government parties and opposition parties sharply diverge on endorsing promise keeping. Then the analysis examines systematic variations in the behaviour of opposition voters. To fulfil these tasks, we designed and executed a purpose‐made survey experiment among Australian and Austrian voters.

Comparing Austria and Australia

Previous research on voters’ preferences, especially towards the representative behaviour of MPs, focused mainly on the United States or single countries in Western Europe (e.g., Bengtsson & Wass, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2010, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2011; Campbell & Lovenduski, Reference Campbell and Lovenduski2015; Carman Reference Carman2006). To overcome the single‐country limitation and investigate the extent to which patterns of attitudes to party representation styles are generalizable, we opt for a comparison of two countries that in our expertise differ in a range of relevant aspects but are fundamentally similar enough to allow for inferences about specific mechanisms. Australia and Austria are both established Western democracies with relatively stable party systems. They also share institutional features that are unlikely to be related to the research question of this article. Specifically, they are both federal systems without important linguistic or (sub)national distinctions.

However, the two countries show important differences that will allow us to draw inferences as to the extent to which the patterns found in earlier studies (Werner, Reference Werner2019a; Werner, Reference Werner2019b) are stable. First, while Austria has a more standard 5‐year election cycle and voluntary voting, Australia is characterized by a rather short election cycle of 3 years and compulsory voting. This means all Australian citizens with voting rights are forced to engage with electoral and party politics on a relatively frequent basis while Austrians, like many other Western European citizens, have more leeway in deciding on their political engagement as they are asked to do so less frequently.

Second, while Austria has a proportional electoral system that leads to coalition governments, Australia's electoral system to the government‐forming lower house is majoritarian, which means that one of two parties always forms the government. Thus, Australian respondents’ experience with single‐party governments allows them to evaluate pledge fulfilment and attribute accountability directly to one specific party while Austrian respondents are used to the complex considerations of coalitions and coalition agreements.

Moreover, the longer election cycles in Austria also mean that temporary opposition voters there have to endure longer waiting periods for their party to return to public office and, thus, put up longer with pledge fulfilment by parties for which they did not vote. Therefore, if we do not find a noticeable difference in the effect for the same types of voters in Australia, we can conclude with some confidence that the effect is due to the type of voter and not to the institutional characteristics of the system in question. Finally, the centre‐left Australian Labour Party and the conservative Coalition dominate the Australian party system. The Coalition is a stable party alliance of the Liberal Party, the National Party of Australia and two regional conservative parties. Since the Australian system is a two‐party system with regard to government formation, the vast majority of Australian voters has experienced their party running the government.

In comparison to Australia where the major centrist parties have largely retained their strength, the Austrian party system is marked by a significant decline in support for the major parties in the centre and growing party political diversity. It now consists of three mid‐size parties and a varying group of smaller parties. This indicates greater ideological heterogeneity ranging from the populist radical right to the green alternative left. Of the three mid‐size parties, two—the centre‐left Social Democratic Party (SPÖ), the centre‐right People's Party (ÖVP) – were traditionally the electorally dominant political forces but have lost about half of their voters over the past 30 years, a majority of whom have since switched to the Greens and the populist radical right Freedom Party (FPÖ). The latter of these two parties, has periodically functioned as a radical antisystem party seeking to rally disaffected citizens and is seen as an indicator of growing political polarization. The traditional pattern of centrist coalitions and cooperation among the major parties has, in recent times, given way to government formations with a clearer ideological profile.

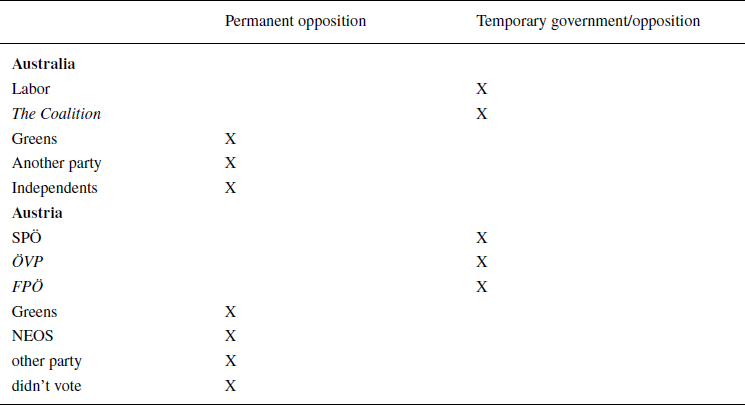

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of all the political parties in the analysis and also shows which parties were actually in government when the survey was in the field. As we explained in our theoretic section, further analysis requires distinguishing between the voters of parties that have been in and out of government (temporary opposition voters) and those of the permanent opposition. In Table 1, we identify the respective parties for each of the two countries.

Table 1. Categorization of parties for the purpose of the experiment

Note: Coalition voters are those with a past vote for the Liberals, the Liberal National Party, the Country Party and the National Party. Excluded are those voters who cannot recall their past vote. Australia has compulsory voting, thus no ‘didn't vote’ option. Real government parties at survey time in italics. N = 3882.

The surveys

In order to ensure the comparability of our empirical data, we ran the same survey and used the same survey methodology in both countries. Both surveys were executed as online surveys, using reputable national survey companies (Omnipol in Australia and Market Institute in Austria).Footnote 3 These companies have access to respondent panels in their respective countries, which comprise the contact information of several hundred thousand adults that volunteered to partake in surveys. A random sample of individuals in these panels were invited to take part in our survey, which makes our samples the typical convenience samples that we can gather from online surveys. To ensure that our respondent samples are as closely representative to the general voting population in their countries as possible, the sample collection included quotas for gender, age and region of residence. This means that these demographic questions were asked first and only respondents falling into categories where the quota was not filled were then allowed to move to the survey. The resulting samples include 1,131 Australian and 1,268 Austrian respondents. Inevitable sampling biases are mitigated by using population weights in all analyses. We ran the Australian survey on 13–18 October 2016 and the Austrian survey on 12–14 February 2019, which were periods of political stability and outside imminent electoral campaigns in both countries.

Here we want to point to another important and innovative aspect in our approach in that we fielded policy pledges to survey respondents as an abstract idea. This means we did not ask about a specific policy associated with a particular party or election. Naturally, this runs the risk of yielding low effects because voters may be more agitated by concrete issues about which they feel passionate. However, such an approach would have left us guessing as to whether our results were driven by our theoretical argument about promise keeping or rather by the policy issue involved. Moreover, comparing two countries in terms of general voter reactions to pledge fulfilment would have been impossible if the effects had been based on concrete policies given the differences in contexts and actors. Lastly, this approach also had the advantage that voters were unlikely to guess at a seemingly expected answer, which is the case when a specific policy issue is attached to a question. While we may have sacrificed effect size, we are more confident this way about the validity of the relationship measured.

A survey experiment

In the experimental setup, survey respondents were asked to decide whether a hypothetical government in their country should implement a policy. Before making this decision, the respondents were presented with a limited number of randomly assigned pieces of information. The experiment had multiple steps, which will be laid out in detail below and is equivalent for both countries’ surveys.

First, respondents were introduced to the experiment with an introductory statement foreshadowing a hypothetical political situation: ‘The next few questions are about a hypothetical situation in Australian/Austrian politics ….’ Respondents were then told which party would be in government in this situation. In Australia, this could have been the Coalition or Labour in government, while in Austria this could have been the SPÖ, ÖVP or FPÖ: ‘Imagine a few years from now, the [Party—respondents received party name according to experimental allocation] is (returned to government/in government) after the next federal election’. This information not only varies the party in government but also makes it clear that all following information and decisions are given in regard to a specific party in government. The allocation of respondents to one party in the experimental government is the first aspect of the survey that is experimentally controlled. In the Australian case half the respondents were faced with a Coalition and the other half with a Labour government, while in the Austrian survey, the sample was split evenly into thirds, facing the SPÖ, ÖVP or FPÖ in government. The assignment was randomized using a random number generator in the survey software, and built‐in quotas ensured that the experimental groups were evenly populated.

We then introduced the idea that this government faces the decision whether to introduce a policy or not. Afterwards, we provided additional information to the respondent about this policy by confronting them with a specific policy situation. As shown in Figure 1, each policy situation included three factors that stood for or against a policy: (1) whether the party in government had promised to implement this policy or not to implement it; (2) whether the public approved of this policy or was against it; and (3) whether an expert panel deemed the policy beneficial for the general Australian/Austrian good or not.

Figure 1. An exemplary experimental scenario. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The party promise was, thus, directly addressed in the set‐up. Public opinion is operationalized by referring to polls because these are the measure of public opinion with which respondents are most likely familiar. The experts’ opinion is operationalized by referring to an expert panel and extensive deliberation as this indicates that different perspectives and strands of knowledge were included in the discussion and integrated into the solution. All three principles have a positive and a negative but no neutral option, which prevents a bias in favour of the status quo when comparing a promise to do something versus not to do something. Furthermore, it offers respondents two ways to express their preference for promise keeping: endorse a policy that was promised to be implemented AND not endorse a policy that was promised not to be implemented. We exploit these possibilities in our analysis, as explained below.Footnote 4

When respondents were faced with a scenario, they experienced a short temporal delay with no options for activities, increasing the chance that the scenarios were read thoroughly and understood. Respondents were then asked to judge whether the government should ‘definitely’, ‘probably’, ‘probably not’ or ‘definitely not’ introduce this policy. After making their first decision, respondents were asked the same question for one of the remaining seven scenarios.Footnote 5

In order to focus the decision on promise keeping and its alternatives, no further information was given about the policy. Any introduction of policy content – for example, a specific infrastructure, welfare, or environmental policy – would likely lead to a measurement of policy preferences. Similarly, placing the policy into a specific context of time and space might trigger respondents to second‐guess whether the policy would have an impact on them personally, and thus alter their decision. Furthermore, there is no information about the salience of the policy, the predictable media reaction, individual politicians involved or other factors that might potentially influence voters’ responses in a real‐life decision. On the one hand, it needs to be acknowledged that real‐life political decision‐making is much more complex than it is possible to reproduce in a survey experiment. On the other hand, introducing such complexity would substantially decrease the validity of the measure that aims at distinguishing voters’ preferences for parties keeping their promises on a general level.

The dependent variable in all our analyses is, thus, the likelihood that the respondent wants the experimental government to keep its promise. In other words, respondents were asked whether or not they thought the government should implement its previously stated policy intent based on the information presented to them. If a respondent endorses the policy promised by the party or opposes the policy promised not to be implemented by the party, both combinations are counted as the respondent's preference that the party keep its promise. Alternatively, respondents want the party to break its promise if they endorse a policy that the party promised not to implement or reject a policy that the party promised to implement. Promise breaking is coded as ‘0’ and promise keeping as ‘1’.

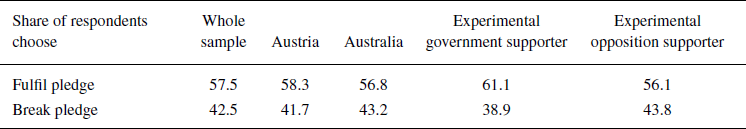

Finally, in order to test for the effect of supporting the (experimental) party in government, the direct challenger, or a permanent opposition party, we used the vote recall question to measure respondents’ party support. While there are no non‐voters in our Australian data because of the compulsory voting system, those Austrian respondents who did not vote were classified into the permanent opposition group. Based on the ‘vote recall question’, we divide voters into two groups: voters whose party is in the experimental government and all other voters whose party is in the experimental opposition. Table 2 shows the relative frequencies of our dependent variable for the whole sample, the two countries and the respondents supporting the experimental party or the opposition. It shows differences between the latter two groups, suggesting we might find some support for our hypothesis.

Table 2. Preference for pledge fulfilment or breaking

In the final step to prepare our analysis, we create a categorical variable assigning the respondents to three groups: first, respondents preferring the party defined as experimental government party; second, respondents preferring the parties that are temporarily in opposition but have the potential to win the government in real life;Footnote 6 and, third, respondents preferring a party that is neither the experimental government party nor a temporary opposition party but what we dub a permanent opposition party. This variable is based on the information presented in Table 1.

Control variables

Previous studies have found that a range of standard demographic factors do or do not have an impact on public attitudes toward decision making by democratic representatives. We include those factors that were found to affect these attitudes in at least one previous study, to avoid both the omitted variable bias but also not to fall into the trap of the kitchen sink approach. These factors are (1) age and gender (Bengtsson & Wass, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2010, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2011; Campbell & Lovenduski, Reference Campbell and Lovenduski2015; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017), (2) respondents’ income as a control for their general socio‐economic status, (3) rural or urban residence (Bengtsson & Wass, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2011; Carman, Reference Carman2006), and (4) whether respondents have first‐hand experience with local party organizations (Werner, Reference Werner2019a). In addition, education levels should influence people's preferences, as it affects an individual's understanding of the political process in general (Carman, Reference Carman2006; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017).

Analysis

In our analysis, we proceed by first establishing whether there are systematic differences between different groups of voters, whether the variables we identified in our theoretical discussion have indeed the effect we assume, and whether these patterns are similar or different in Austria and Australia. Specifically, we need to test whether opposition voters follow the same behavioural logic of government voters, which would manifest itself in a significant divergence in support for a governing party keeping its policy promises. As the voters were also randomly shown the opinions expressed on the policy by the public and experts, we then investigate whether this additional information changes the effect of government/opposition status on the respondents’ preferences for pledge fulfilment.

Subsequently, we hone in more closely on the variation exhibited among opposition voters and their motives.

All of the following analyses control for socio‐demographic factors, which do not substantially affect the results except when particularly noted. For conciseness, we present only the hypothesized effects here and show the full results with all controls in the Supporting Information Appendix (Table A3a). These tables show that only gender and the age category of 18–24 year olds significantly affect individuals’ choices. In the Supporting Information Appendix (Table A3b), we also show that the effects we present here are stable when excluding the control variables.

Do opposition voters generally differ from government party voters?

First, we turn to the question of whether government and opposition voters followed the same rationale when making their evaluations of policy promises. As stated before, a rational evaluation based on self‐interest would imply that citizens would sharply diverge on endorsing pledge fulfilment. While rational government party voters would favour this, rational voters in the opposition would largely not.

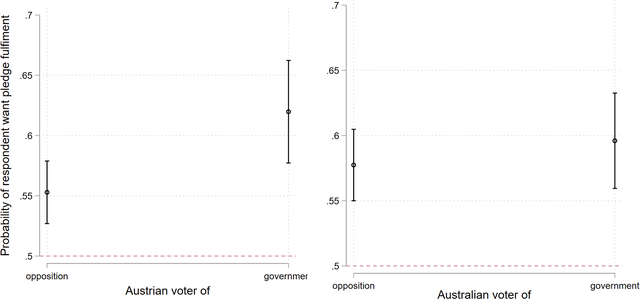

Indeed, the main finding from this first analysis is that there is a difference in how government party supporters and opposition supporters respond in Austria but not in Australia. Yet, first, we find that in both countries both types of voters are broadly in favour of keeping pledges and thus in favour of the principle that governments should stick to what they promised before the election. We infer this from the fact that in Figure 2, the probability that a respondent wants pledge fulfilment is in all cases greater than 50 per cent. However, the preference for pledge fulfilling over pledge breaking is not as clear as a strong normative reading might suggest. While there is no obvious numerical threshold, we would nonetheless expect a population with a strong normative preference for fulfilment over breaking to make decisions that show a higher rate than is indicated by a ratio of 3:2. While we might not expect that 100 per cent of the decisions are congruent with pledge fulfilment, values around 60 per cent do not seem to convey an overwhelmingly strong preference.

Figure 2. Preference for pledge fulfilment in government and opposition voters in Austria and Australia. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

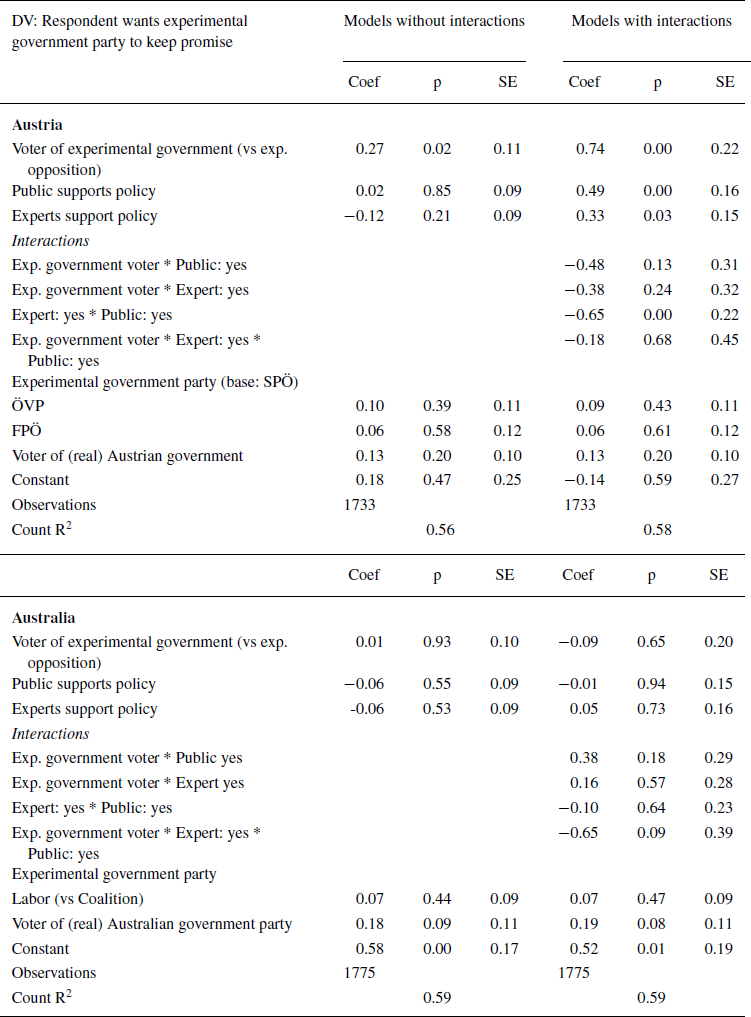

Furthermore, the results in Table 3 show that respondents in Australia do not follow the hypothesized rational logic as we find no significant differences between experimental government and opposition voters. Australians, who have a very high likelihood to support one of the two parties that are frequently in government, seem to have a normatively driven relationship to pledge fulfilment. In contrast, respondents in Austria tend to behave in a way that is broadly consistent with our argument. Austrian respondents, who operate in a broad multiparty system of considerable ideological range and can choose between three ideologically distinct parties of size and with government experience, along with two smaller parties, do exhibit significant differences in their expectations toward pledge fulfilment. For Austrian opposition voters, ideology and political preference matters relatively more than does the principle of promise keeping when compared with government voters. The latter, as predicted by our hypothesis, are significantly more committed to pledge fulfilment. These effects hold across the political spectrum as we see no significant differences across different groups of partisans.

Table 3. Analysis of voter group effects on the likelihood of respondent wanting the experimental government party to fulfil their pledges

Note: Logistic regression using svy command in Stata to account for survey character of the data. Control variables excluded here for presentation but reported in the Supporting Information Appendix (Table A2a).

We also included a measure to capture the preferences of actual government voters (as opposed to experimental government voters) and found no effect. Again, this is not surprising, as actual voters would likely care more about actual policies, the substantive and specific nature of which might overshadow any political principle. As we are interested in general democratic principles that are not policy‐bound and in comparability across political systems, we focused our argument on voters and experimental governments.

Turning to the interaction effects specified in hypotheses H2a, b and c, depicted in Figure 3, we focus on the Austrian case. As Table 3 and Figure A3a in the Supporting Information Appendix show, Australian respondents do not strongly react to the different types of information about the pledge, following the logic of H2c about normatively driven voters. In contrast, we find partial confirmation of the hypothesized effects in H2a and H2b as well as some unexpected results among the Austrian respondents. In all effect combinations, Austrian opposition voters remain dismissive of the endorsement of both experts and the public, which is in line with H2b. In fact, when experts endorse the policy, support among opposition voters declines even further. In the case of Austrian government voters, however, we find an interesting split in the results. While we find no reinforcing effect of expert endorsements on government voters' expectations of promise fulfilment, experts seem to have at least a confirmatory effect. Austrian government voters retain their significantly greater support for pledge fulfilment compared to opposition voters. More importantly, we see a noticeable drop in support for pledge fulfilment in government supporters if the public thinks the policy is good, as the predicted probabilities in the upper row of Figure 3 are higher than in the lower row. This result is certainly puzzling and does not conform to our predictions. It could be explained if government voters think that public opinion is dominated by the opposition or is somehow tainted, which may reflect the greater polarization in the Austrian political system.

Figure 3. Preference for pledge fulfilment in Austrian government and opposition voters when confronted with expert opinion and public opinion on the pledged policy. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Disaggregating the opposition voters – are permanent opposition voters different?

Initially, we wondered which type of voters would be most in favour of promise keeping regardless of their own partisan preference. We surmised that if voters had a rational expectation of seeing their policy preferences enacted, their behaviour would likely follow the rational voter calculus. On the other hand, we hypothesized that voters who have no rational expectation of seeing their preferred program enacted – as they vote for permanent opposition parties or do not vote at all – might follow one of two competing logics. They might have a very strong preference for the democratic ideal of promise keeping, focusing on the legitimacy of the system if they cannot have their preferred policy gains (H3a). Alternatively, they might be so ideologically convinced of their party's policies, that they are even more likely to reject the promises by the opposing government than temporary opposition parties (H3b).

To test whether permanent opposition voters indeed behave differently than temporary opposition voters, we assigned all voters of parties never having been in government to the category labelled ‘permanent opposition’ and ran the same analysis as in Table 3. Table A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix shows the results, where the two groups of opposition voters (temporary because they support the main opposition party or permanent because they support parties without government‐participation opportunities) are contrasted with each other and with the voters of the respective experimental government party. Figure 4 presents the main findings regarding these group differences.

Figure 4. Preference for promise keeping among three different voter groups. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4 does not show, as expected, any difference between temporary and permanent opposition party voters and leads us to accept the null‐hypothesis of both H3a and H3b as there is no difference between permanent opposition voters’ likelihood to endorse government party promise keeping compared to temporary opposition voters. Even though permanent opposition voters can have no expectation (or hope) that their preferred party has the opportunity to fulfil (or break) its pledges, they largely neither accept nor reject the idea that government parties’ pledges are important. Thus, our assumption that voters' relationship to the system of government – beyond the individual party or parties in power – is critical to assessing democratic responsibility and accountability in terms of promise fulfilment, has not been borne out. To the extent that such rational considerations come into play at all, the immediate question of who is in power at any given time seems more important.

To corroborate this finding, we further analyzed each opposition group individually. We show the results in Table A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix and find that the only significant effect is among the Australian temporary opposition voters, who support promise keeping by the experimental party significantly more when their preferred party is in the real Australian government. This speaks to our earlier interpretation that Australian voters, who are faced with a minimal fragmented party system, view the importance of party pledges on a more normative, systemic level.

Conclusions

In this paper, our inquiry focuses on the conflict between two of the most fundamental assumptions we have about voters. Accountability (Schedler, Reference Schedler1998, p. 197) and promissory democratic representation (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003) are key to democratic government and broadly desirable, both normatively, but also when measured empirically. However, the assumption about rational voters following their interests is also key to understanding voting behaviour and a staple of the political science literature since Downs (Reference Downs1957) and Duverger (Reference Duverger1963). Why, then, would rational voters want a government for which they did not vote and whose promised policies they clearly do not support to implement that promise? Assuming that it is simply because of morality, why would morality take precedence over self‐interest and rationality in this particular case, while the assumptions of rational voters prevail in other cases? In a nutshell, our results clearly point to this dilemma faced by opposition voters, and indeed the majority favour the moral outcome. Rationality comes into play in the more fractionalized Austrian case, where the political system spans a much larger space, suggesting a potentially larger ideological gap between government and opposition voters.

Further, we argued that this question might be affected by additional information such as public opinion and expert views. We also wondered about which group of opposition voters was most likely to respond favourably to promise keeping regardless of partisan self‐interest. Here, we suggested that voters supporting parties with little chance of entering government, and thus acting on their policy promises, might do so because these citizens are impelled to a significantly greater extent by the normative principle that a promise always implies a moral obligation or, conversely, they might reject all promises as worthless.

We devised a survey experiment that we conducted in two rather different political systems to test our hypotheses. This experiment targeted the general theoretical conflict between the normative value of a party pledge and the partisan relationship of the respondent to the pledging party. Thus, we did not include any policy content. Our findings show a mix of normative and rational aspects. First, in both countries, the likelihood of respondents choosing promise keeping over promise breaking was always larger than 50 per cent. Thus, large numbers of voters were indeed persuaded not to follow their rational preferences but, instead, supported the normative principle of pledge fulfilment by choosing promise keeping in governments other than their own. Viewed strictly from a rational voter perspective, it may come as a surprise that so many citizens, although they did not constitute a majority, were motivated in their decision by normative expectations about good faith and promise. One possible part of the explanation might be that our respondents could have considered valence issues when approaching the experiment, in which case the rationality mechanism would be weakened. There have also been several overarching political developments, the global economic crisis and refugee crisis in Europe comes to mind, that exerted convergence pressures on parties in terms of positioning. Neither country, however, is known to have a system in which valence issues play a role to the extent that they do in the United Kingdom (for example see Green, Reference Green2007). While some valence issues are strong, the Australian two‐party system tends to lead to contrasting positions on issues. The Austrian political system has also become highly differentiated, which would also be reflected in corresponding position taking. Thus, we argue that our findings provide further evidence that in elections, the relationship between voters and parties is mediated by normative expectations about democracy and the normative principles underlying its constitution. These findings hold up even when we control for the effect of expert opinion and the popularity of the policy among the general public. The fact that this finding is consistent in two very different democratic systems indicates a level of generalizability as high as is possible in a two‐case study.

However, there is also a normatively troubling detail to this finding – also consistent in both countries – in that the likelihood of respondents choosing promise keeping over promise breaking was usually around 60 per cent. Of course, there is no numerically obvious threshold above which this likelihood would fit the normative importance of pledge fulfilment in the democratic process of responsiveness and accountability. Yet, a result indicating that respondents choose promise breaking in at least one‐third of situations shows that the normative principle does not reign supreme and other considerations come into play.

Further, we find no differences among different types of opposition voters, in either country. We assumed that those who are permanently excluded from government would either have higher normative expectations or not hold any. Our findings suggest that it does not matter whether respondents can expect their party to be in government or whether they know that this will likely never happen. The lack of a difference between temporary and permanent opposition voters is a refutation of our hypothesis regarding the difference in opposition status, but also evidence that the different types of opposition voters think in similar ways about the promises of the governing party. This is interesting because it indicates that minor party voters do not have different expectations than major party supporters, or more generally, that the long‐term relationship to the government does not influence the expectations towards the democratic system.

However, we also notice important variation between our cases. In Australia, we do not find a difference on promise keeping among opposition and government voters suggesting partisan rationality does not play a role. In Austria, on the other hand, we find the assumed rational difference in that respondents who opposed the promise party were significantly less likely to favour keeping promises. While our study does not allow us to empirically pinpoint the cause of this outcome, factors like the difference between coalition and single‐party governments might play a role. In particular, we assume Austrians have considerably more incentives to reject the pledges of opposing parties than Australians because of the higher fractionalization and polarization of the party system.

Our case selection focused on two countries that are very different in terms of institutions, party competition, and political culture, thus setting up our approach as an analysis least likely to find common patterns. The fact that we found several such common patterns is indicative of a high level of generalizability, which will need to be tested systematically in further studies with more cases. Broadening the empirical base should shed more light on the causes of the differences we found. Ganghof and Bräuninger (Reference Ganghof and Bräuninger2006), for example, have shown that different types of parliaments, and whether opposition parties can influence governmental decision‐making, affect how accommodating parties are in the legislative arena. It is conceivable that such party behaviour influences voters’ expectations and evaluation of parties’ pledges.

We purposefully restricted our experiment by not confronting our respondents with a specific policy issue but the vague idea of a party pledge. We did this so as not to elicit approval of, or aversion to, a particular policy but rather an abstract idea. The use of more specific policies would render experiments more realistic, but at the cost of making it difficult to isolate the effect of a policy being a pledge. Future research that wishes to focus on more concrete policy promises may replicate the experiment by varying the respective societal salience and polarization, while measuring the individual respondents’ attitudes toward that policy. Although such an analysis would undoubtedly be valuable in allowing a distinction to be made between party support and political approval, it would be extraordinarily difficult to design such a study as a cross‐national comparison. Despite the restrictions we imposed and the relatively abstract nature of the underlying concept, we were able to identify clear behavioural patterns that speak to fundamental questions in democratic attitudes and voting behaviour

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their constructive and productive work on this article. They also thank numerous colleagues who have commented on this project at various conferences and through many drafts.

Open access publishing facilitated by the Australian National University as part of the Wiley ‐ ANU agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Funding Information

Funding was provided by the European Union´s Horizon 2020 project ‘PaCE’ (Grant agreement No 8223370) and by Griffith University (New Researcher Grant 47404).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A3a: Table 3 with controls.

Table A3b: Replicating results for Table 3, excluding control variables

Table A3c: Replication of Table 3 using only first decision of each respondent

Table A3d: Replication of Table 3 using only second decision of each respondent

Figure A3: Preference for pledge fulfilment in Australian government and opposition voters when confronted with expert opinion and public opinion on the pledged policy

Table A4: Contrasting permanent and temporary opposition voters

Table A5: Individual analyses of permanent and temporary opposition voters