Introduction

Since the onset in late 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc across the globe. For years, hundreds of millions of people globally have contracted SARS-CoV-2, resulting in millions of deaths tied to the novel coronavirus (World Health Organization, 2023). Yet the negative impact of the pandemic is not limited to the public health domain; the corresponding economic turmoil has also been devastating. Particularly, measures employed to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus – such as social distancing and lockdowns – severely restricted workers’ labour market participation that caused extreme financial distress to households. South Korea’s unemployment rate during the pandemic, for example, hit the highest level since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (Kim, Reference Kim2021). Citizens worldwide found it very difficult to cope with such tremendous economic risk individually, so the pandemic has brought attention to the role of the state in society and the economy (van Apeldoorn & de Graaff, Reference van Apeldoorn and de Graaff2022), especially highlighting the imperative function of the state as a social protection provider.

In response to the pandemic-driven economic disruptions, governments worldwide promptly intervened to protect their citizens with various policy measures ranging from generous unemployment benefits to direct cash transfers to individuals or households (International Monetary Fund, 2022). In terms of both policy variety and the amounts of money spent, the government interventions during COVID-19 were even more robust than those attempted during the Great Recession, another crisis that demanded an active government role (O’Donoghue et al., Reference O’Donoghue, Sologon and Kyzyma2022). In effect, the pandemic has strengthened the role of the welfare state, and the pandemic-driven changes in social welfare systems are expected to persist even after the crisis fully passes (The Economist, 2021). Still, some researchers and citizens view such government efforts as insufficient for dealing with the ‘new social risks’ induced by the pandemic, stressing the need for much more expansive welfare programmes (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Kühner and Shi2022). Correspondingly, in many countries, the pandemic even ignited policy debates over universal basic income (UBI) (Nast, Reference Nast2020; Nettle et al., Reference Nettle, Johnson, Johnson and Saxe2021). Before the pandemic, UBI had been considered one of the most radical policy ideas due to its universal and unconditional benefits (Lee, Reference Lee2020; Roosma & van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020). However, since the pandemic, UBI has been discussed as an actual possibility in places such as Spain and the United Kingdom (Ng, Reference Ng2020; Pickard, Reference Pickard2020). Similarly, in South Korea, Lee Jae-myung, the 2022 presidential candidate of the then-ruling party, pledged to introduce UBI and categorical basic incomes for youth and rural residents (You & Choi, Reference You and Choi2022).

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has seemingly created favourable political circumstances for politicians and governments to attempt rapid welfare expansion. Yet in a democracy, securing strong public support is crucial in pursuing and steadily sustaining an expansive welfare state (Brooks & Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2006; Cutright, Reference Cutright1965; Pierson, Reference Pierson1996; Skocpol, Reference Skocpol1992). Significant institutional changes (e.g., welfare reform) take time, so if public support is not sufficiently strong or enduring, the heightened political attention to social protection expansion spurred by the pandemic could easily vanish as governments and citizens grow accustomed to the crisis. Thus, in contemplating the future of the welfare state in the post-pandemic era, ascertaining whether and how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced public attitudes towards social protection is imperative.

Drawing on findings from panel data collected in South Korea in the early and middle phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, I argue that the impact of pandemic-driven economic risk – specifically, unemploymentFootnote 1 – is too limited to spur strong public support for social protection. Unemployment induced by the pandemic is conducive to higher degrees of individual support for social protection measures, but the impact disappears in about a year. Further analyses show that, once individuals are re-employed and as the time spent in economic difficulties becomes more distant, personal unemployment experiences are no longer positively associated with support for social protection. This result implies that pandemic-driven economic risk will increasingly become less influential as economic recovery continues. Finally, pandemic-induced unemployment experiences have a lasting impact primarily on young adults.

The remaining parts of this paper proceed as follows. In the next section, I review and explain the theoretical frameworks of this study by building on existing literature on the association between economic risk and public attitudes towards social protection. Next, I briefly describe the data used in the empirical analyses and the research design. The results of the empirical analyses follow, and the discussion on the implications of those findings concludes the paper.

Theoretical review

Economic risk and public attitudes towards social protection

Economic risk has been at the core of welfare politics since the genesis of modern welfare states. Among the driving forces that promoted the development of welfare states are troubling economic situations and corresponding social problems that the poor experienced in the Industrial Revolution era. Existing poverty laws coined in the context of agrarian society were ineffective in coping with the socioeconomic turmoil induced by new technological changes, so the state began more actively intervening as a social protection provider (van Kersbergen & Vis, Reference van Kersbergen and Vis2013). As economic development and industrialisation advanced further, economically disadvantaged individuals inevitably encountered associated socioeconomic problems, such as unemployment and poverty, calling for further interventions of welfare states. Consequently, welfare states have persisted as functional government responses to these issues (Cutright, Reference Cutright1965; Wilensky, Reference Wilensky1974).

Yet such functionalist approach alone may not fully explain states’ expanded role in responding to economic risk and providing social protection. According to Cutright (Reference Cutright1965), the popular will of constituencies secures the connection between economic risk and states’ provision of social protection. States do not introduce or expand social welfare programmes in a vacuum; rather, states do so because the public demands the welfare benefits. By successfully satisfying such demands, welfare states can continue enjoying a high level of public support, resulting in a virtuous cycle where a welfare state creates its own upholders through transforming welfare beneficiaries into strong supporters of the welfare state (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996; Skocpol, Reference Skocpol1992). In fact, evidence shows that strong public support for the welfare state was a major source of the tenacity of welfare states in advanced economies in the face of neoliberal retrenchment threats (Brooks & Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2006).

Investigations examining how economic risk relates to the welfare state through building strong public support come with the underlying assumptions that individuals are risk-averse and self-interested and that their social policy preferences are malleable rather than fixed. Under such assumptions, individuals are expected to promptly grow supportive of social protection in response to economic hardship, hoping to enhance their own economic security. Accordingly, the strongest support for social welfare programmes is expected to be found among those who are economically vulnerable and, therefore, highly likely to benefit from the programmes (Hasenfeld & Rafferty, Reference Hasenfeld and Rafferty1989).

Unemployment experienceFootnote 2 is an important indicator of economic risk. Most people in a capitalist economy sustain their lives by earning most of the resources needed through labour market participation, and unemployment can be a fatal shock to people’s economic security, which can consequently spur demands for social protection. Using panel data from Sweden collected between 1985 and 2010, Martén (Reference Martén2019) found that individuals who experience unemployment become significantly more supportive of redistribution. Similarly, Blekesaune (Reference Blekesaune2007) provided cross-national evidence by using data from thirty-nine countries. In that study, the unemployed show stronger support for redistribution than the employed, calling for a greater level of responsibility from the state than from individuals in terms of economic provisions.

Economic risks such as unemployment can be particularly heightened under certain circumstances. In times of crisis, for example, a greater number of citizens across society become economically insecure than in normal times due to losing jobs or being reduced to part-time work, which can result in an increased need for overarching government intervention. Indeed, crises ranging from economic crises to wars and natural disasters have been critical moments for welfare states across the globe to emerge and expand (see e.g., Castles, Reference Castles2010; Dauber, Reference Dauber2013; Hornung & Bandelow, Reference Hornung and Bandelow2022; Kwon, Reference Kwon2005; Song, Reference Song2003). Economic crisis trends have unsurprisingly been found to be associated with shifts in public attitudes towards social protection systems (Popic & Burlacu, Reference Popic and Burlacu2022). Accordingly, many studies have focused on periods of economic crisis as a relevant condition for investigating how personal experiences with significant economic hardship are associated with popular support for social protection. The Great Recession, the most recent global financial crisis prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has received ample scholarly attention for this purpose. Hacker et al. (Reference Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger2013), for example, found that the economic risk induced by the recession is positively associated with economic concerns and demand for a more active government role in providing social protection. Based on findings from panel data collected both before and after the financial crisis, several other studies have also demonstrated the causal relationship between personal experiences with recession-induced economic hardship (e.g. unemployment and income loss) and preferences for social protection remedies, including redistribution and unemployment benefits (Margalit, Reference Margalit2013; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Buss and Bähr2016; Owens & Pedulla, Reference Owens and Pedulla2014). Blekesaune (Reference Blekesaune2013) also demonstrated how the times when economic risk is heightened across society can be crucial moments for spurring public support for social protection. The results of the study show that individuals living in countries where economic strain is more widespread show stronger support for redistribution than those in better economic circumstances.

Although previous studies have heavily focused on traditional welfare and redistributive policies, increasing empirical evidence has recently become available on how economic risk experiences can spur individuals to demand even more radical policy solutions, such as UBI. Using data from European countries, Lee (Reference Lee2018) identified a positive relationship between country-level economic insecurity and aggregate-level UBI support. Roosma and van Oorschot (Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020) relied on the same data to find that the same tendency exists at the individual level as well; people in a more economically vulnerable position are more supportive of UBI.

COVID-19 and public attitudes towards social protection

Building on previous work emphasising the role of economic risk as a self-interest motive that underlies welfare attitudes, economic risk driven by the COVID-19 pandemic can reasonably be expected to fuel popular support for social protection. Yet some early studies have yielded mixed evidence using aggregate data. For example, using panel data collected in Germany before and after the onset of the pandemic, Ebbinghaus et al. (Reference Ebbinghaus, Lehner and Naumann2022) detected increased levels of support for social protection measures such as pension, unemployment protection, family policy, and healthcare. Some studies similarly found that many countries have seen increased popular support for UBI since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Nettle et al., Reference Nettle, Johnson, Johnson and Saxe2021; Van Hootegem & Laenen, Reference Van Hootegem and Laenen2023; Weisstanner, Reference Weisstanner2022). In contrast, with no evidence of significant shifts in aggregate-level public opinion on social protection policies, several other studies have cast doubt on the impact of the pandemic (Ares et al., Reference Ares, Bürgisser and Häusermann2021; Blumenau et al., Reference Blumenau, Hicks, Jacobs, Matthews and O’Grady2021; Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2023). However, such early scholarly debates rely only on simple distributions and shifts of aggregate-level data, so the evidence cannot sufficiently confirm whether and how pandemic-driven economic risk spurs people to demand greater government responsibility in providing social protection. Thus, more research using individual-level data is needed to further examine the impact of the pandemic.

Identifying the mere association between economic risk and public support for social protection, however, may not be sufficient. Even when found to be significantly associated with public attitudes, economic risk has been controversial regarding the persistence of its effect (Margalit, Reference Margalit2019). How long economic risk remains effective is important because this can determine economic risk’s capacity to foster substantial changes in the welfare state. If the impact of economic risk on public welfare attitudes does not last for a sufficiently lengthy period, the consequential issue salience regarding welfare expansion would disappear even before reaching the policymaking arena, falling short of fuelling significant institutional changes.

Early studies that identified a positive association between pandemic-driven economic risk and public support for social protection diverge regarding the persistence of the association over the crisis period. For instance, Nettle et al. (Reference Nettle, Johnson, Johnson and Saxe2021) argued that the impact of the pandemic has persisted during the pandemic period. Yet Ebbinghaus et al. (Reference Ebbinghaus, Lehner and Naumann2022) showed that the once-increased public support for social protection measures in Germany returned to pre-pandemic levels within a year. Van Hootegem and Laenen (Reference Van Hootegem and Laenen2023) also found that the increased support for UBI in Belgium was short-lived and not necessarily attributable to the impact of the pandemic.

Collectively, the mixed evidence from the early studies suggests potential conditioning effects from certain factors that differentiate the duration of the association between pandemic-driven economic risk and public welfare attitudes. One such factor is the changes in individuals’ economic status over the course of economic crisis. At the onset of economic crisis, many people encounter economic hardships such as unemployment or income loss, which can mobilise a self-interest motive of social protection support. Those same people, however, gradually get re-employed and become economically better off as economic recovery proceeds. If self-interest is a key factor that makes people supportive of social protection during economic crisis, the improved economic circumstances will likely be reflected quickly in people’s attitudes in the form of reduced support for social protection. This outcome is plausible because, from the perspective of self-interest, social protection can be seen as less beneficial by those who no longer suffer from economic difficulties.

Indeed, previous studies provide evidence that supports such a conjecture. For example, by examining Americans’ experiences of the Great Recession, Margalit (Reference Margalit2013) showed that the impact of unemployment in increasing support for welfare spending dissipates as individuals’ employment status improves. Similarly, in Martén’s (Reference Martén2019) work, the once-unemployed who had grown supportive of redistribution in response to job loss returned to their initial attitudes as economic prospects improved. The dynamics of the long-span economic turmoil induced by the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that a similar pattern may be observed in this pandemic as well. In other words, even those who grew supportive of social protection when first hard hit by the pandemic-driven economic risk can possibly become less positive towards social protection over time after their own economic difficulties get resolved.

Furthermore, people’s ages at the onset of crisis may also play a role in differentiating the duration of the impact of pandemic-driven economic risk on public support for social protection. Age has been suggested as influential in the association between economic risk and public welfare attitudes (Margalit, Reference Margalit2019; Neundorf & Soroka, Reference Neundorf and Soroka2018). According to the socialisation theory, large parts of people’s core beliefs and values are constructed during youth and early adulthood and remain stable for life (Krishnarajan et al., Reference Krishnarajan, Doucette and Andersen2023; Mendelberg et al., Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017; Tyler & Iyengar, Reference Tyler and Iyengar2023). Accordingly, after experiencing economic risk when young, people are likely to view the impact as serious and maintain the beliefs and values built following the risk experience until later in life. Deep-rooted beliefs and values lasting since earlier in life, however, often lead to older individuals being likely to resist the impact of economic risk with resilient policy attitudes.

Previous studies have buttressed the socialisation perspective with empirical evidence. For instance, in O’Grady’s (Reference O’Grady2019) study, while changes in income barely affected aggregate attitudes towards social spending, strong discernible effects were found only on the policy attitudes of the young. Pahontu et al. (Reference Pahontu, Hooijer and Rueda2021) suggested that such economic risk experiences early in life can have long-term influences on individual political behaviours and attitudes. In a study using data on the 1944–45 Dutch Famine, the researchers found that exposure to economic shock can spur voting for left-wing parties even after more than fifty years have passed. These previous findings suggest that even the same or similar kinds of economic risk experiences during the pandemic may hit younger individuals harder and longer than older individuals.

Data

The empirical analyses of this study aim to demonstrate (1) whether economic risk driven by the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increases public support for social protection; (2) how persistent the association remains over time; and (3) what factors differentiate the duration of the association. I use the first and second waves of the panel data from the Public Perceptions on COVID-19 Survey,Footnote 3 , Footnote 4 which interviewed South Koreans aged 18 or older twice during the pandemic. The Wave 1 data were collected between 24 June 2020, and 1 July 2020, just a few months after the onset of the pandemic (N = 2,544). The respondents were recontacted and invited to take the Wave 2 survey (N = 1,832, attrition rate = 28%) between 17 March 2021, and 23 March 2021, the point at which a year had passed since the declaration of the pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Thus, the data reflect the perceptions of the respondents in both the early and middle phases of the pandemic. The surveys were conducted online using the opt-in panel of Macromill Embrain with proportional quotas set to match the compositions of the entire Korean population in terms of gender, age, and region of residence.

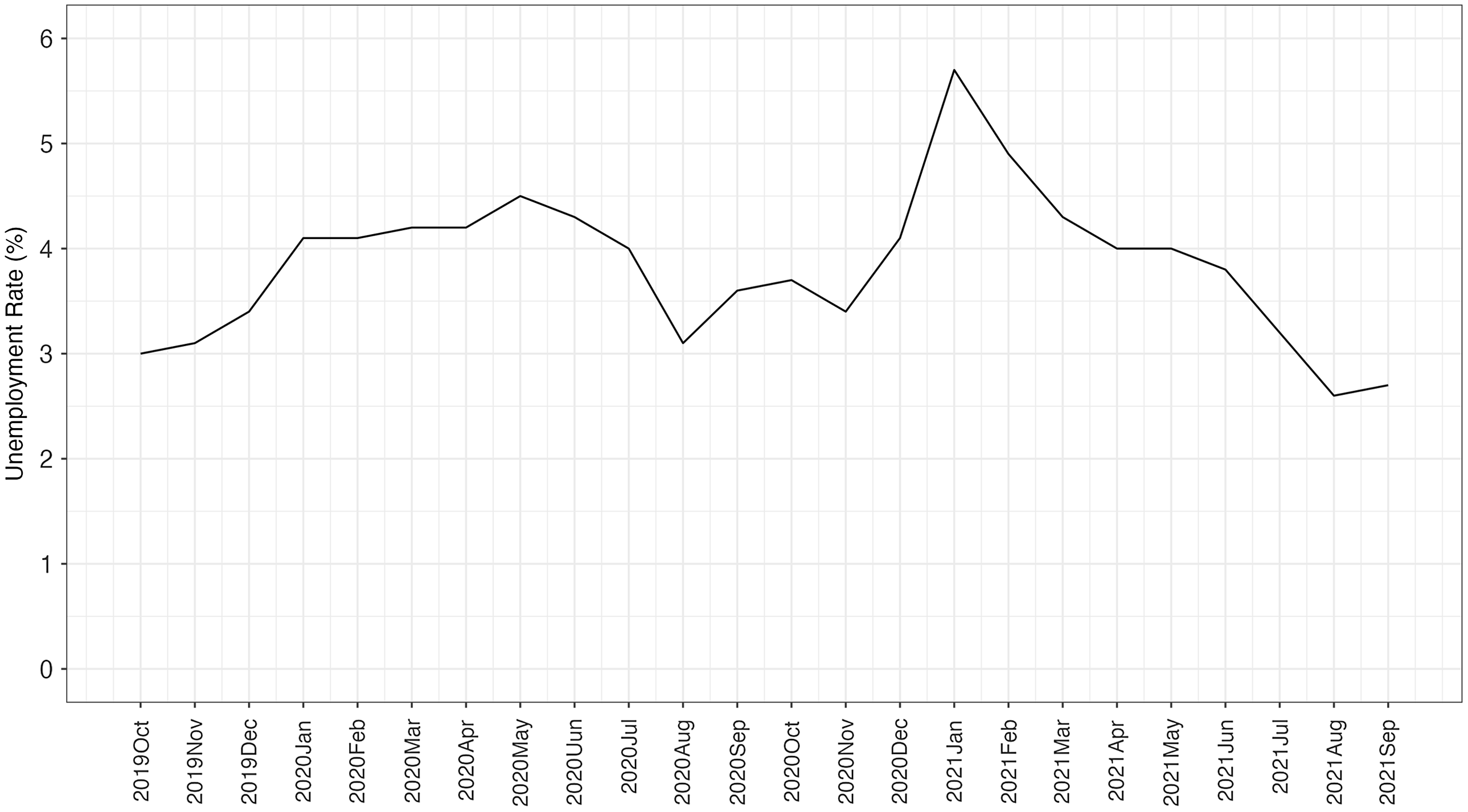

Since South Korea’s first COVID-19 case was confirmed in January 2020, strict social distancing measures were introduced nationwide to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. Such measures for public health inevitably restricted economic activities and people’s labour market participation, resulting in severe economic turmoil. As shown in Figure 1, South Korea’s unemployment rate jumped by about 1% right after the onset of COVID-19 and peaked in January 2021 at 5.7%, the highest level since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (Kim, Reference Kim2021). Indeed, according to the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (2021), 28.5% of Korean workers experienced unemployment, furlough, a reduced work schedule, or business closure due to the pandemic, resulting in an average 40.5% drop in the workers’ labour income as of April 2020. In response to economic disruptions, the Korean government distributed the Emergency Disaster Relief Funds to all citizens from May to August 2020, with additional benefits selectively offered to those facing economic hardships. These active government interventions highlight the significant economic risks experienced by Koreans during the pandemic.

Figure 1. Trends in South Korea’s unemployment rate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Statistics Korea.

I focus on unemployment experience to capture pandemic-induced economic risk because unemployment can immediately reduce household income. In both waves of the survey, respondents were asked whether they had ever lost their jobs during a given period prior to the interview. Specifically, the Wave 1 data reflect the unemployment experiences that occurred in the early phase of the pandemic, starting with its onset in January 2020. The Wave 2 data also contain information about the unemployment experiences that occurred in the period between the first and second interviews. This period includes January 2021 when South Korea’s unemployment rate peaked during the pandemic. Respondents were coded as Yes if they had ever lost their jobs during a given period and No otherwise. In the analyses using the Wave 2 data, unemployment experiences reported in Wave 1 were categorised as remote unemployment experience (Unemployment Experience t-1 ), and those reported in Wave 2 as proximate unemployment experience (Unemployment Experience).

As dependent variables expected to be influenced by pandemic-induced unemployment experience, I examine respondents’ attitudes towards three social protection measures. First, to measure attitudes towards welfare benefits, respondents were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following statement: The government should increase welfare benefits. Second, the following statement was also presented regarding preferences for redistribution: The government should reduce the inequality between high- and low-income groups. Finally, to investigate broad ranges of social protection, I include attitudes towards UBI, a relatively newer and more radical policy alternative compared to traditional welfare and redistributive policies. Therefore, the responses to the following statement are used: To guarantee a minimum standard of living, the government should implement universal basic income that provides monthly monetary subsidies to all citizens. While the original responses to the three statements were recorded using an ordinal measure that ranges from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 4 (Strongly Disagree), I reversed the values of the responses for a more intuitive interpretation so that a low (high) number corresponds to a weak (strong) policy support.

As potential factors that can determine the duration of the association between independent and dependent variables, respondents’ employment status change and age are included. First, in operationalising employment status change, I considered two aspects: whether respondents had a remote (Unemployment Experience t-1 ) or proximate (Unemployment Experience) unemployment experience, and if either was true, their current employment status (Re-employed or Unemployed). If respondents did not have pandemic-driven unemployment experiences, they were categorised into one of the following groups: Always Employed, Always Unemployed, or Other Footnote 5 (reference level). Second, to measure the effect of age, I categorised respondents’ ages into four groups: 18–25, 26–45, 46–65, and 66+ (reference level). Each group respectively represents young adults who have just entered the labour market; younger workers; older workers; and elderly individualsFootnote 6 .

In addition to the key variables, I add a set of control variables. First, material self-interest has long been argued as an important determinant of individual welfare attitudes (Meltzer & Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981, Reference Meltzer and Richard1983). Thus, to account for potential influences from material self-interest, I use two measures: respondents’ yearly disposable household income adjusted for household sizeFootnote 7 (unit: 10,000 Korean Won, approximately £6) and household assets measured on a scale of 1 (Less Than 50 Million Korean Won, approximately £30,000) to 11 (More Than 900 Million Korean Won, approximately £543,000).

Second, respondents’ political orientations can also be influential in shaping policy and political attitudes. According to the power resources theory (Korpi, Reference Korpi2006), politically progressive people are more likely to support the welfare state than their conservative counterparts. I therefore include a measure of self-evaluated political ideology ranging from 1 (Progressive) to 10 (Conservative). Relatedly, party identification (Incumbent, Opposition, Other, and None – reference level)Footnote 8 is also considered. To reflect the strong influence of regionalism in Korean politics (K. Kwon, Reference Kwon2004), a categorical variable for respondents’ region of residence (Honam, Youngnam, and Other – reference level) is included as well.

Finally, the last set of the control variables aims to control for potential influences from some demographic characteristics: gender (Female and Male/Other – reference level)Footnote 9 , age (continuous variable), marital status (Married and Not Married – reference level), and education level measured on a scale of 1 (No Formal Education) to 14 (Some Graduate School or Higher). Table A1 in the Supplementary Material reports the distributions of the variables described in this section.

Results

Figure 2 displays how individual attitudes towards social protection are distributed across policy options and how those attitudes have changed over the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, aggregate-level support for social protection has been high in both the early and middle phases of the pandemic.Footnote 10 Among the three policy options, respondents show the strongest support for redistribution between high- and low-income groups and the weakest support for UBI. Still, in both Wave 1 and Wave 2, nearly 60% of the respondents agree or strongly agree with the government’s responsibility in implementing UBI for guaranteeing a minimum standard of living. At a glance, the distributions of the respondents’ policy attitudes in Figure 2 look very similar across the two waves of the survey, which might imply the stability of individual policy attitudes throughout the pandemic. However, the plots in Column CFootnote 11 show that a large number of the respondents altered their attitudes between the two waves of the survey. Specifically, more than one-third of the respondents – 35.9% for Welfare, 33.8% for Redistribution, and 43.5% for UBI – had either positive or negative attitudinal changes between the two time points. The results suggest a caveat: researchers should not rely solely on simple aggregate-level attitudinal changes but should also carefully examine detailed changes in each answering option when determining attitudinal stability or change with survey data.

Figure 2. Attitudes towards social protection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: N = 2,544 for Column A, and N = 1,832 for Columns B and C.

Turning to main analyses, I show how economic risk induced by the COVID-19 pandemic – specifically unemployment – has affected support for social protection over the course of the pandemic. The dependent variables were measured on a four-point ordinal scale, so a series of ordinal logit models were estimated using the variables described in the previous section. Figure 3 reports the estimates with the Wave 1 data based on the following model:

Figure 3. Impact of unemployment experience on support for social protection – Wave 1.

Note: N = 1,832. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

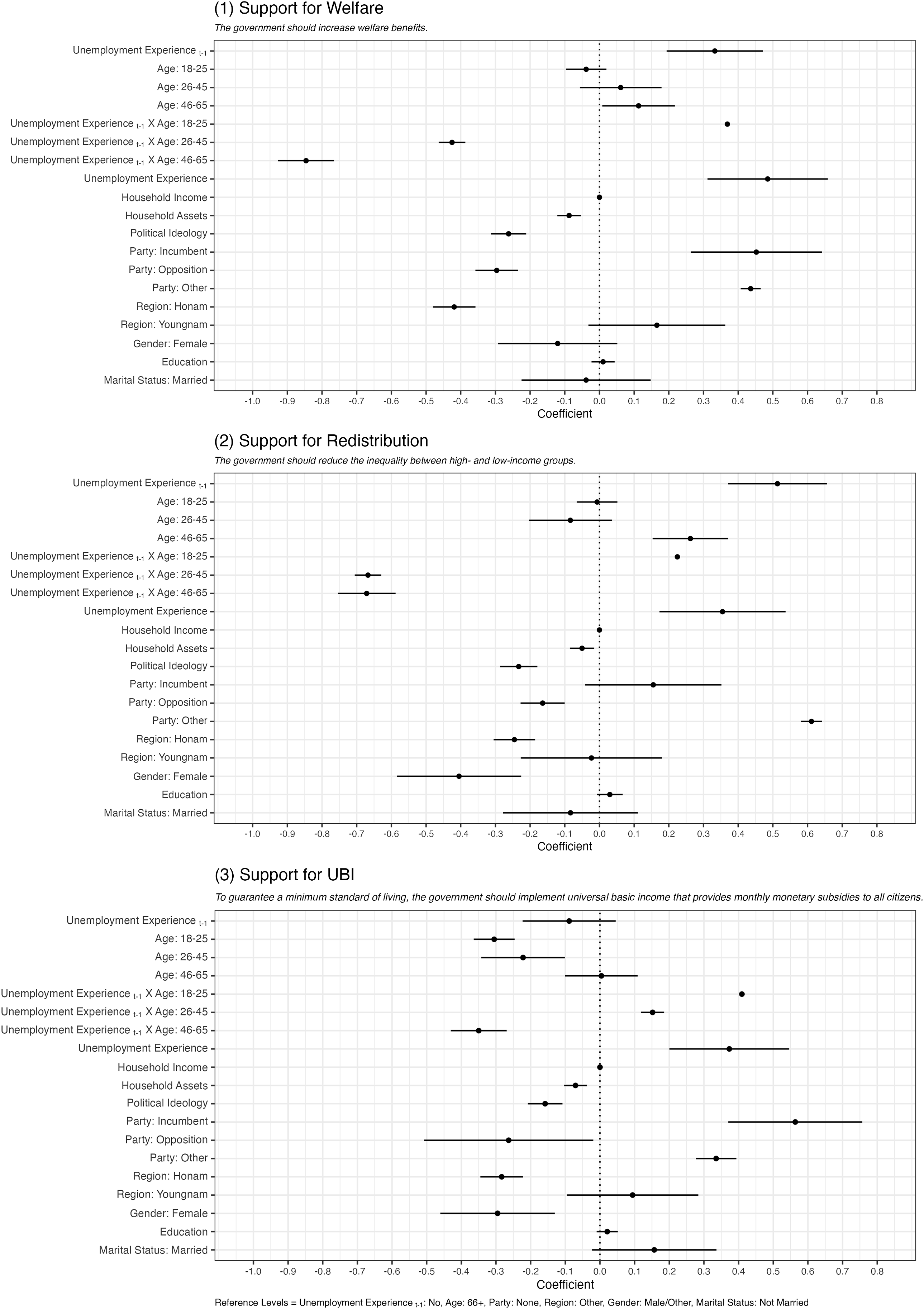

And the results in Figure 4 were estimated with the Wave 2 data employing the following model:

Figure 4. Impact of unemployment experience on support for social protection – Wave 2.

Note: N = 1,832. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Tables that contain the ordinal logit estimates and corresponding predicted probabilities can be found in the Supplementary Material. For a clear comparison of the results, in Figure 3, I only show the estimates from the respondents who answered both waves of the survey. However, as shown in Table A3, the results remain robust regardless of whether all or only partial observations are used.

The results in Figure 3 provide evidence suggesting that a positive association between economic risk and social protection support existed in the early phase of the pandemic. In responses to the Wave 1 survey fielded in June 2020, individuals who reported unemployment experiences during the first few months of the pandemic are more likely to support welfare benefits, redistribution, and UBI. As shown in Table A4, experiencing unemployment increases the predicted probabilities for respondents to express the highest level of support (Strongly Agree) for welfare benefits, redistribution, and UBI by 3.9%, 6.3%, and 1.6% respectively. Hence, as the self-interest-based explanation of welfare attitudes suggests, and as was the case in previous economic crises (e.g., the Great Recession), the heightened economic risk early in the COVID-19 pandemic period appears to have fuelled public support for social protection.

However, estimates in Figure 4 using the Wave 2 data provide somewhat mixed evidence. The models in Figure 4 have the same specifications as those used for estimating the models in Figure 3, except that the models in Figure 4 consider unemployment experiences reported in both the Wave 1 (Unemployment Experience t-1 ) and Wave 2 (Unemployment Experience) surveys. Unemployment Experience t-1 denotes unemployment that occurred in the early phase of the pandemic. Therefore, this unemployment experience represents a relatively remote economic risk experience as up to fourteen months had passed since the occurrence of unemployment when respondents answered the Wave 2 survey. In contrast, Unemployment Experience indicates a more proximate economic hardship that individuals experienced between the two waves of the survey from July 2020 to March 2021. In Figure 4, the remote and proximate unemployment experiences appear to have divergent effects on individuals’ attitudes towards social protection. Similar to the findings in Figure 3, proximate unemployment experiences that newly occurred between the two waves of the survey (Unemployment Experience) significantly increase the likelihood of supporting social protection across all three policy measures. As shown in Table A6, holding all other variables constant, Unemployment Experience is associated with 4% to 7% increases in the predicted probabilities of strongly agreeing with welfare benefits, redistribution, and UBI. Thus, echoing the trend observed in the earlier phase of the pandemic, COVID-19-induced economic risk continued to spur individual support for social protection during the pandemic’s middle phase as well.

Yet the persistence of the impact of economic risk remains in question. With about a year having passed, an unemployment experience reported in the Wave 1 survey (Unemployment Experience t-1 ), a more remote risk experience, no longer increased individual support for social protection measures. In answering the Wave 2 survey, individuals who had lost their jobs very early in the pandemic either showed no discernible attitudes towards social protection (Model 2) or took even more negative positions (Models 1 and 3) than those without such a remote unemployment experience. These results are somewhat surprising given that the same variable – Unemployment Experience in Figure 3 – is positively associated with attitudes towards social protection when considered as a proximate economic risk. In other words, the positive impact of unemployment experience on individual attitudes towards social protection had disappeared in only about a year. The results imply that, although economic risk driven by the COVID-19 pandemic promptly fuelled public support for social protection, the effect lasted only briefly.

The only brief effect of pandemic-driven economic risk is bewildering because the dire pandemic situation was still unfolding when the Wave 2 survey was fielded in 2021. Considering the arguments from previous studies that re-employment and improved economic circumstances can make the once-unemployed return to pre-crisis policy attitudes (e.g., Margalit, Reference Margalit2013, Reference Margalit2019; Martén, Reference Martén2019), the labour market recovery underway in 2021 might influence the impact of pandemic-driven unemployment on individual support for social protection. Indeed, as shown in Figure 1 in the previous section, South Korea’s unemployment rate kept decreasing for months after peaking in January 2021. Many individuals who had lost their jobs early in the pandemic increasingly became re-employed, which could lead them to perceive social protection benefits as less attractive compared to periods when they had been facing personal economic difficulties.

Figure 5 shows how the association between economic risk and attitudes towards social protection can be conditioned by the changes in individuals’ employment status over the COVID-19 pandemic period. The estimates presented in the figure were obtained using the following model:

Figure 5. Conditioning effect of employment status change.

Note: N = 1,832. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

And Figure 6 reports the corresponding predicted probabilities of expressing the strongest support for social protection measures. The most interesting results are found in the divergence between the re-employed who experienced unemployment in the early (Unemployment Experience t-1 ) and middle (Unemployment Experience) phases of the pandemic. Compared to those who are not in the labour market (Other) or those in the most secure employment status (Always Employed), individuals who were re-employed after experiencing unemployment early in the pandemic (Unemployment Experience t-1 ) do not exhibit more positive attitudes towards social protection. However, for the individuals who were re-employed after experiencing unemployment relatively more recently (Unemployment Experience), the impact of the unemployment experience remains significant, increasing the predicted probabilities of expressing the strongest support for social protection measures by about 7%–9%, respectively. In contrast, those remaining unemployed after losing a job due to the pandemic are significantly more supportive of social protection than those without unemployment experiences regardless of the timing of unemployment.

Figure 6. Conditioning effect of employment status change (predicted probabilities).

To summarise, the results in Figures 5 and 6 show how economic recovery can loosen the association between economic risk and public support for social protection. Once individuals are re-employed and as the time spent in economic difficulties becomes more distant, personal unemployment experiences are no longer positively associated with support for social protection. Thus, as economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic gains momentum with an increasing number of people experiencing improved economic well-being, the impact of economic risk induced by the pandemic will gradually diminish. This finding gives an explanation why the impact of pandemic-driven economic risk can be only short-lived and, therefore, insufficient for promoting a significant expansion of the welfare state.

While the influence of pandemic-driven economic risk on social policy support does not last long on average, it may persist longer for certain subgroups of people than for others. Especially, considering the findings from previous studies about the conditioning effect of age in the association between economic risk and welfare attitudes (e.g., Margalit, Reference Margalit2019; Neundorf & Soroka, Reference Neundorf and Soroka2018; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019; Pahontu et al., Reference Pahontu, Hooijer and Rueda2021), the unemployment experiences during the pandemic may have a lasting effect primarily on young adults. The results in Figures 7 and 8 show how the persistence of the effect of a remote unemployment experience (Unemployment Experience t-1 ) on attitudes towards social protection can vary depending on respondents’ ages. The following model was used to obtain the results:

$$\eqalign{Policy{\rm{\ }}Attitudes ={\hskip 1pt } & \alpha + {\beta _1}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experienc{e_{t {\hbox -} 1}} {\ }+\cr & {\beta _2}Age + {\beta _3}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experienc{e_{t {\hbox -} 1}} \times Age \ +\cr & {{\rm B}_4}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experience + \gamma Controls + \varepsilon}$$

$$\eqalign{Policy{\rm{\ }}Attitudes ={\hskip 1pt } & \alpha + {\beta _1}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experienc{e_{t {\hbox -} 1}} {\ }+\cr & {\beta _2}Age + {\beta _3}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experienc{e_{t {\hbox -} 1}} \times Age \ +\cr & {{\rm B}_4}Unemployment{\rm{\ }}Experience + \gamma Controls + \varepsilon}$$

Figure 7. Conditioning effect of age.

Note: N = 1,832. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 8. Conditioning effect of age (predicted probabilities).

A year after the occurrence, the unemployment experience in the early phase of the pandemic remained positively associated with social protection support consistently across all three policy measures only among young adults aged between 18 and 25, compared to their older counterparts. If young adults had reported an unemployment experience in the Wave 1 survey, they were still more likely to support social protection in the Wave 2 survey than those without such a remote unemployment experience. Specifically, young adults’ remote unemployment experience increases the predicted probabilities of expressing the strongest support for welfare benefits and redistribution by 10.5% and 15.2%, respectively. The effect on attitudes towards UBI is relatively modest (3.2%). Still, remote unemployment experience remained influential in increasing support for the radical policy alternative only among young adults, even after about a year had passed. These findings demonstrate that, about a year after experiencing pandemic-induced unemployment, young adults still carried the economic risk’s impact in their policy attitudes, while older people were already insulated from the impact.

Admittedly, the results should be interpreted with caveats in two points. First, the time gap between the Wave 1 and Wave 2 surveys is approximately one year, which may be insufficient for drawing definitive conclusions based on the socialisation theory. Second, as shown in Table A12, the numbers of observations for each subgroup are relatively small, although the lengths of 95% confidence intervals in Figure 7 demonstrate that sample size does not affect the precision of the estimates. Nonetheless, the current findings suggest that the unemployment experiences induced by the pandemic may have a lasting impact, especially on young adults, influencing their attitudes towards social protection for an extended period.

Discussion

In sum, despite seemingly creating favourable political circumstances for welfare expansion, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a limited impact on securing the strong public support necessary for significant institutional changes in the welfare state. Individuals promptly responded to pandemic-driven economic risk by growing more supportive of the government responsibility for employing social protection measures that can buffer that risk. Yet the impact of the pandemic-driven economic risk vanished in only about a year even though the troubling pandemic situation remained underway. Additional analyses demonstrate that re-employment can loosen the association between unemployment experience and support for social protection, especially when the unemployment period is relatively remote. Considering the continuing economic recovery from the pandemic (Kaufman & Srinivasan, Reference Kaufman and Srinivasan2022), the impact of pandemic-driven economic risk will continue to gradually diminish over time as economic conditions improve for a larger number of people. Finally, the impact of the pandemic-induced economic risk has primarily lingered around young adults for a relatively lengthy period. This finding could hold promise for long-term efforts to expand welfare, considering that young adults will continue to exert influence as voters in future politics for the coming decades. Still, as young adults comprise a smaller proportion of the population compared to older generations, their political influence is likely to remain limited and insufficient to create substantial policy changes.

The findings of this study are not without limitations. First, all survey data used in this study were collected during the pandemic, so no information is available about pre- or post-pandemic situations. Relatedly, the approximate one-year interval between the two surveys suggests a caveat in interpreting the results. By the time of the Wave 2 survey, a maximum of fourteen months had elapsed since the initial occurrence of unemployment early in the pandemic, but that time gap may be insufficient to be considered long-term. Future studies would be able to use additional data that cover the long-term post-pandemic period to provide more comprehensive information about the pandemic’s longitudinal effect on social protection systems.

Second, this study exclusively examines South Korea. While South Korea was significantly affected by the pandemic, the negative impact there was relatively less severe than in many other countries. For example, South Korea did not implement a nationwide lockdown during the pandemic. Such a specific context might be influential in shaping respondents’ attitudes. Future research can conduct cross-national comparative studies to investigate the generalisability of this study’s results. Yet to the best of my knowledge, no such longitudinal comparative data for the COVID-19 pandemic are currently available.

Third, this study uses only three policy options – welfare benefits, redistribution, and UBI, which individuals might perceive as too remote to effectively address the urgent risks posed by COVID-19. Additionally, since these policies were already politicised before the pandemic, there might be a potential bias in responses. While the three policy options provide a high level of comparability with existing literature, future studies can consider employing a wider range of policy options.

Nevertheless, this study contributes to the decades of scholarly efforts by political economists to identify the determinants of public attitudes towards the welfare state by considering the unusual crisis period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The evidence demonstrates that even the significant economic risk posed by the pandemic alone cannot fuel persistent public support for social protection. Hence, significant institutional changes in the welfare state are hard to achieve by solely relying on the impact of economic risk, and influences from other factors may be needed.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727942400014X

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented under the title: ‘COVID-19 and Public Attitudes toward Universal Basic Income’. The paper was presented at the 2021 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, the 2021 Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference, the Korean Association of Electoral Studies—Sogang Institute of Political Studies Joint Conference, and the Korean Welfare State Research Group Monthly Seminar. I am grateful to the participants and discussants at these events for their meaningful comments and suggestions. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their very valuable comments. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A3A2A02090384).

Competing interests

The author declares none.