Introduction

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are important actors in democratic states as they facilitate political representation and contribute to democratic policymaking (Alarie and Green, Reference Alarie and Green2010; Bryden, Reference Bryden1987; Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022; Hein, Reference Hein, Howe and Russell2000: 224). CSO participation in legislative and judicial processes ensures that decision-makers are exposed to a plurality of viewpoints, which otherwise may be overlooked in the development of law and public policy (Alarie and Green, Reference Alarie and Green2010; Borovoy, Reference Borovoy, Morton and Snow2018: 267; Bryden, Reference Bryden1987: 491; Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022; Pal, Reference Pal and Leslie Seidle1993). In Canada, one of the more influential CSOs is the Women's Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF). LEAF was officially formed in 1985, to mobilize around the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms (henceforth, Charter) to enhance the substantive equality of women and girls (Razack, Reference Razack1991: 46). In recent years, LEAF has extended its mandate to advocate for transgender and nonbinary people, as well. LEAF has an impressive track record of engaging in forms of legal mobilization—having participated in over 100 court cases to date. Considering LEAF's frequent participation in court, the organization has unsurprisingly received significant scholarly attention, particularly within the field of political science (for examples, Hausegger, Reference Hausegger1999; Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004; Morton and Allen, Reference Morton and Allen2001; Morton and Knopff, Reference Morton and Knopff2000). This body of scholarship has unanimously described LEAF as among the most successful actors involved in legal mobilization in the post-Charter era.

Although LEAF has been a dominant force within Canadian courts, participation in the courts is only one of the organization's three pillars of advocacy. LEAF also pursues its mission and goals through law reform (that is, participation in the legislative process) and public education. The literature on LEAF, however, has been judicial-centric, focusing almost exclusively on the organization's legal interventions at the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) level. As a result, we know very little about LEAF's advocacy efforts in the lower courts, nor about their activities or successes outside of the judicial arena. Similarly, despite the organization's evolving mandate, as well as broader changes to the political environment in which civil society operates, and the simple reality that the Charter is no longer new, nothing substantive has been published on LEAF in over twenty years.Footnote 1

This study seeks to respond to these important gaps in our understanding of LEAF by providing an empirical, descriptive account of all the advocacy-related activities (n = 213 unique actions), political and legal, undertaken by the organization between 1985 and 2022. Our longitudinal analysis illustrates that beginning approximately in 2006, LEAF diversified its “collective action repertoire” (Traugott, Reference Traugott1995) to engage more extensively in forms of political mobilization. Further, our study shows that over time, the matters which LEAF mobilizes around have evolved, with greater emphasis placed on issues such as Indigenous rights and law, hate speech and online hate, and gender-based violence. As LEAF has been a recurring focus of past political science scholarship, updating the empirical record about LEAF in its contemporary form, on its own, makes an important contribution to both the Canadian law and politics and civil society literatures. Perhaps more significantly, by looking at LEAF as a case study, this work enhances our understanding of how CSOs are dynamic and strategic actors who engage in multiple arenas of advocacy and evolve their tactics and mandates over time. Our study ultimately challenges the judicial-centric approach adopted in previous studies of LEAF and underscores the importance of studying advocacy through a longitudinal lens and with methodological and theoretical approaches that account for the dynamism of civil society.

Context and Literature Review

Canadian CSOs engage in multifaceted and diverse strategies of advocacy to influence public policy. As such, they are active participants in state institutions, including legislatures and courts (Sobeck, Reference Sobeck2003: 350–51). In the wake of the Charter, legal mobilization—the strategic participation in court cases to pursue one's policy goals, became a central part of the “collective action repertoires” of many Canadian CSOs (McNabb, Reference McNabb2023: 716). CSOs also participate in more traditional, political arenas—lobbying different levels of government and participating in legislative proceedings (Seidle, Reference Seidle1993). In legislative processes, groups can inform public policy decisions in several ways, such as through shaping public opinion, issue framing and “crafting regulatory language” (Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022: 2; Fry, Reference Fry2022; Sabatier, Reference Sabatier1988; Sabatier and Whiteman, Reference Sabatier and Whiteman1985). CSOs serve an important role in democratic policymaking by promoting and advocating on behalf of the diversity of interests that exist across Canadian society and the groups they represent (Alarie and Green, Reference Alarie and Green2010; Borovoy, Reference Borovoy, Morton and Snow2018: 267; Bryden, Reference Bryden1987: 491; Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022; Pal, Reference Pal and Leslie Seidle1993). Through advocacy, organizations ultimately seek to advance the policy interests of the specific groups they represent (Olson, Reference Olson1982). This understanding of CSOs in the policymaking process relies on the underlying assumption that individuals in these groups are “boundedly rational”—meaning that their behaviour is motivated by the goal of achieving desirable policy outcomes (Jenkins-Smith et al., Reference Jenkins-Smith Hank, Nohrstedt, Weible, Ingold, Weible and Sabatier2018: 140; Sabatier and Pelkey, Reference Sabatier and Pelkey1987: 238).

Importantly, however, the ability of CSOs to influence the development of law and public policy is not equal across the sector (Smith, Reference Smith1990, Reference Smith2002; Voth, Reference Voth2016) and can shift alongside broader sociopolitical change. Access to institutions is often dependent on the resources available to groups at a given time, and their capacity to secure relationships with policymakers and policymaking institutions (McCormick, Reference McCormick1993; Smith, Reference Smith1990: 304). Further, the size and influence of a group will impact the likelihood that its position will be considered and successful when lobbying decision-makers (Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022: 3). Considering these constraints, CSOs must be adaptive to changing political contexts and behave strategically by securing and maintaining funding, collaborating with other like-minded actors and “venue shopping” to best advance their organization's policy goals (Dwidar, Reference Dwidar2022; Jenkins-Smith et al., Reference Jenkins-Smith Hank, Nohrstedt, Weible, Ingold, Weible and Sabatier2018; Olson, Reference Olson1982; Voth, Reference Voth2016).

LEAF, a prominent CSO in the area of women's substantive equality, was founded in 1985 to mobilize around the Charter. A board of directors oversees and defines LEAF's broader strategic mandate, while a legal committee makes decisions on the specific cases and causes in which the organization becomes involved (LEAF, 2021; LEAF, n.d.; Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004: 13). LEAF immediately began participating in SCC cases in 1985, when Section 15 of the Charter, the equality provision, came into effect after being delayed for a three-year “grace period” (Epp, Reference Epp1998: 193; Razack, Reference Razack1991: 47–8). While it primarily formed as a group focused on legal mobilization in the courts, public education and participation in law reform processes also constitute parts of LEAF's mandate and approach to advocacy (LEAF, n.d.). The organization's involvement in the legislative process is closely tied to its legal mobilization activities—frequently participating in parliamentary proceedings when the government is responding to court cases that the organization intervened in at the SCC (Seidle, Reference Seidle1993:199–200). Historically, however, LEAF limited its participation in legislative proceedings in light of the advocacy work already being done in this arena by other women's organizations, such as the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (Seidle, Reference Seidle1993: 199).

For the first twenty years of LEAF's existence, its primary arena of advocacy was the SCC. As a result, much of what we empirically know about LEAF involves the organization's experience with legal mobilization in Canada's highest court. LEAF's participation in the SCC was primarily through intervention: a mechanism which allows governments, organizations and individuals to apply to the court to make brief written and/or oral arguments in cases in which they are not directly involved (McNabb, Reference McNabb2023). The SCC accepts approximately 90 per cent of all applications to intervene (Alarie and Green, Reference Alarie and Green2010), and while interveners are not allowed to raise new issues or expand the record, interveners can provide the court with additional, important perspectives that otherwise may not be raised.Footnote 2

Between 1985 and 1999, the SCC accepted all of LEAF's applications to intervene (Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004: 15). LEAF was considered a key “repeat player” (Galanter, Reference Galanter1974) in the SCC during this time; with the organization intervening in more cases than any other nongovernmental actor (Hausegger et al., Reference Hausegger, Hennigar and Riddell2015: 228; Morton and Allen, Reference Morton and Allen2001: 79). The scholarship on LEAF has collectively found the organization to be “highly successful” in its interventions—having a measurable impact on both judicial decision-making and case outcomes. Most commonly, studies arrived at this conclusion based upon the high rate at which the majority of the SCC decided cases in the same manner proposed by LEAF in their written arguments (for example, a dismissal where LEAF argues for a dismissal) (Hausegger, Reference Hausegger1999; Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004; Morton and Allen, Reference Morton and Allen2001). LEAF has found most of its success in constitutional cases that deal with section 15 of the Charter, and in family law and criminal law cases (Hausegger, Reference Hausegger1999; Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004; Morton and Knopff, Reference Morton and Knopff2000). Additionally, Manfredi (Reference Manfredi2004) found that between 1988 and 2000, the SCC referred 108 times to extralegal materials provided to the court by LEAF, suggesting that the organization has shaped how the court understands the relevant issues in the cases it participates in (Reference Manfredi2004: 150). Similarly, Manfredi reports that LEAF's interventions in the legal arena have produced broader societal change, tracing, for example, an increase in the sexual assault reporting rate following LEAF's interventions in cases like Seaboyer (1991) and O'Connor (1995), and an increase in the rate of abortion following LEAF's participation in Morgentaler (1988). In a similar vein, Hausegger (Reference Hausegger1999) and Morton and Allen (Reference Morton and Allen2001) also describe LEAF to be highly successful in that governments typically respond to the legal cases LEAF intervenes in, with policies that are favourable to women and feminist conceptions of substantive equality.

When LEAF was first created, it was afforded significant state funding, and as a result, the organization retained a strong organizational and professional structure (Brodie, Reference Brodie2001). However, the broader scholarship on Canadian CSOs suggests that the sector as a whole has been subjected to various measures of austerity since the mid-1990s (Dobrowolsky, Reference Dobrowolsky2009; Laforest, Reference Laforest2011). Perhaps the most notable development was the elimination of the Court Challenges Program (CCP) between 1992–1994 and then again in 2006. Reinstated in 2017, Footnote 3 the CCP is a federal program that financially supports organizations and individuals who seek to participate in constitutional litigation in the courts (Brodie Reference Brodie2001: 365–66). LEAF's success in SCC advocacy has been attributed by some to the high degree of financial support it has historically received through the CCP (Brodie, Reference Brodie2001: 373; Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004: 33; Roach, Reference Roach and Leslie Seidle1993: 171). Therefore, past cancellations of the CCP raise questions about whether LEAF's capacity to engage in legal mobilization was undermined by these changes.

Although the extant literature on LEAF has helped to illuminate the important role played by the organization in the development of law and policy in the post-Charter era, and in advancing women's substantive equality in Canada, the literature has ultimately been judicial-centric. Less attention has been given to the organization's broader mandate of advocacy, or the ways in which LEAF's legal mobilization fits within or relates to its other arms of advocacy. Likewise, as mentioned, there has been nothing substantive published on the organization in the past two decades. These gaps in the literature particularly matter because recent work on legal mobilization at the SCC suggests that LEAF is no longer among the top “repeat player” interveners in cases involving the Charter (McNabb, Reference McNabb2023). CSOs such as the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, just to name a few, have greatly outpaced the interventions of LEAF (McNabb, Reference McNabb2023: 721). In fact, between 2013 and 2021, LEAF only intervened in four Charter cases at the SCC, all of which involved section 15 (right to equality) (McNabb, Reference McNabb2023: 722). If LEAF is no longer a frequent participant in SCC Charter cases, what is the nature of their advocacy? Which arenas does LEAF participate in most frequently? This note aims to respond to these important questions, and in doing so, significantly updates the research in this area. Ultimately, by looking at LEAF through a longitudinal lens, and with attention paid to both their legal and political mobilization efforts, we can better understand the dynamism of CSOs, including the ways in which equity-deserving organizations adapt their approaches to advocacy over time.

Methodology and Sources of Data

This study explores the nature and evolution of LEAF's approach to advocacy through an empirical analysis of the organization's advocacy-related activities undertaken between 1985 and 2022. The unit of analysis is each individual act of advocacy completed by the organization. LEAF maintains a publicly available database that chronicles the organization's participation in legal cases, law reform initiatives and general efforts of advocacy since its inception.Footnote 4 A typical entry in the database includes the specific action taken by LEAF (for example, intervention in a legal case, open letter to government, witness in a parliamentary committee hearing and so forth); the year in which they undertook that action; the forum or arena they participated in (that is, legal case, legislative body, commission or inquiry); and the names of any other organizations or actors that LEAF collaborated with. To construct our original dataset, we systematically extracted this information and categorized each individual act of advocacy as primarily a form of legal or political mobilization. If an entry was classified as “legal,” LEAF formally participated in a legal proceeding within a court or quasi-judicial body.Footnote 5 In these instances, we additionally recorded the level of court involved, and the specific form of legal mobilization taken (intervention, litigation as an added party, sponsorship). In contrast, if an entry was coded as “political,” LEAF's advocacy was targeted at or occurred within, a legislative or other political institution or process. Here, we recorded the institution involved (House of Commons, Senate, provincial legislative body and so forth), and the specific activity undertaken by LEAF (that is, committee witness submission, open letter and so forth).Footnote 6 The primary goal of this stage of the analysis was to identify what LEAF's “collective action repertoire” looks like, and whether and how the organization's tactics have transformed over time. While our categorizing approach-- labelling activities as constituting a form of “political mobilization” or “legal mobilization” is admittedly an artificial simplification of the organization's collective action repertoire, we use these categories as a heuristic: allowing us to neatly, empirically document how LEAF's tactics and venues of advocacy have subtly shifted over time. Nonetheless, future research should build from this work to further explore the diversity of tactics within the broad, umbrella categories adopted here.

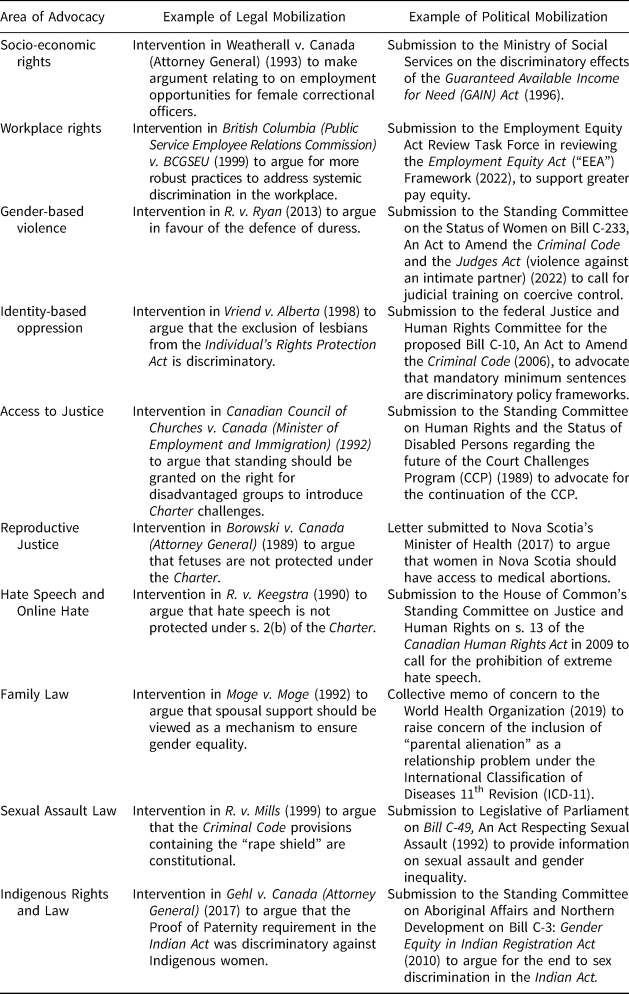

As mentioned previously, in 2015, the organization amended its mandate to include the representation of transgender women, and again in 2022, to include nonbinary people. In light of the organization's changed mandate, we wanted to evaluate whether LEAF's advocacy focus has correspondingly changed, in terms of the issues on which the organization advocates. For each entry in LEAF's database, the organization “tags” its activities with one or more of the labels shown in Table 1 below, which identifies the issue areas. We systematically recorded this information to evaluate whether there has been a change in the specific issues LEAF focuses its advocacy on.

Table 1. LEAF's Tags of Advocacy

Findings

Between 1985 and 2022, LEAF participated in 213 discrete acts of advocacy.Footnote 7 The majority (63.4 per cent) of LEAF's advocacy involved forms of legal mobilization—participation in a legal proceeding within a court or other judicial body. The remaining 36.6 per cent of LEAF's activities were categorized as acts of political mobilization—where the organization's target and/or venue of advocacy was a legislative or other political institution or process.Footnote 8

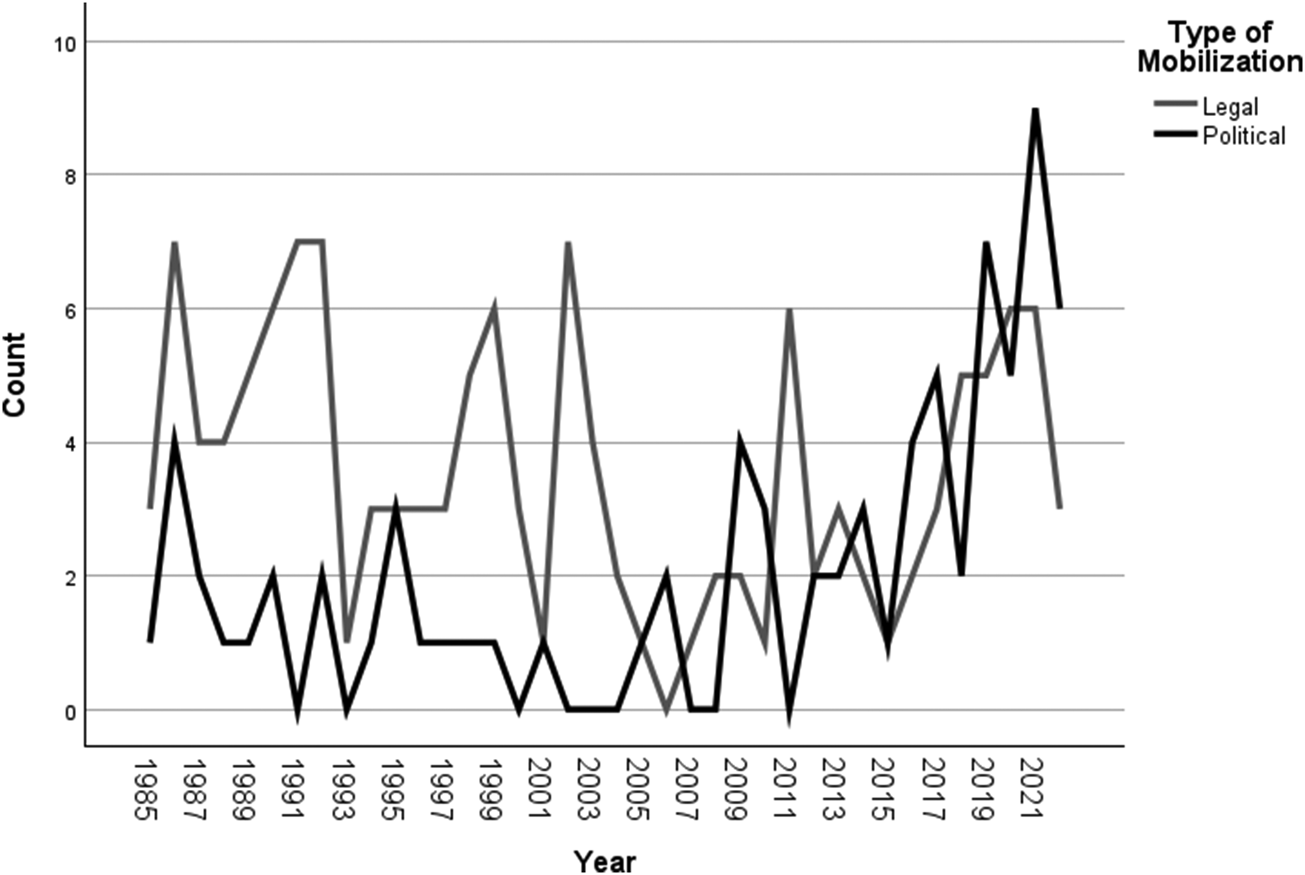

As seen in Figure 1, LEAF's strategy has significantly changed over time. During the first two decades of LEAF's existence, the organization heavily focused its advocacy efforts on the courts—keeping their interventions in legislative and other political processes to a minimum. Up until 2006, there is no individual year in which LEAF does not engage in some form of legal mobilization. In fact, in some of LEAF's most productive early years, the organization was involved in up to seven acts of legal mobilization within a given year period. In contrast, in the 1980s and 1990s, there were several year-long periods in which LEAF did not participate in any form of political mobilization, with some multiyear gaps during the early 2000s.

Figure 1. LEAF's Advocacy Activities, 1985–2022 (n = 213).

Our findings point to 2006 as an approximate turning point in LEAF's approach to advocacy. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 1, there is an identifiable shift in the distribution of LEAF's activities, where the organization's political mobilization begins to match, and in certain years outpace, the organization's activity in court. Notably, 2006 is the only year in LEAF's history in which they did not participate in any court cases,Footnote 9 and their activity in the courts was limited in the 16 years that followed (when compared to the 1980s and 1990s). In contrast, there has been steady growth in LEAF's political mobilization activities since approximately 2006, with 2021 marking a record high of nine acts of political mobilization. Although there are some exceptional recent year periods in which LEAF primarily engaged in legal mobilization, such as in 2011, where the organization engaged in zero acts of political mobilization but intervened in six court cases, five of which were at the SCC.

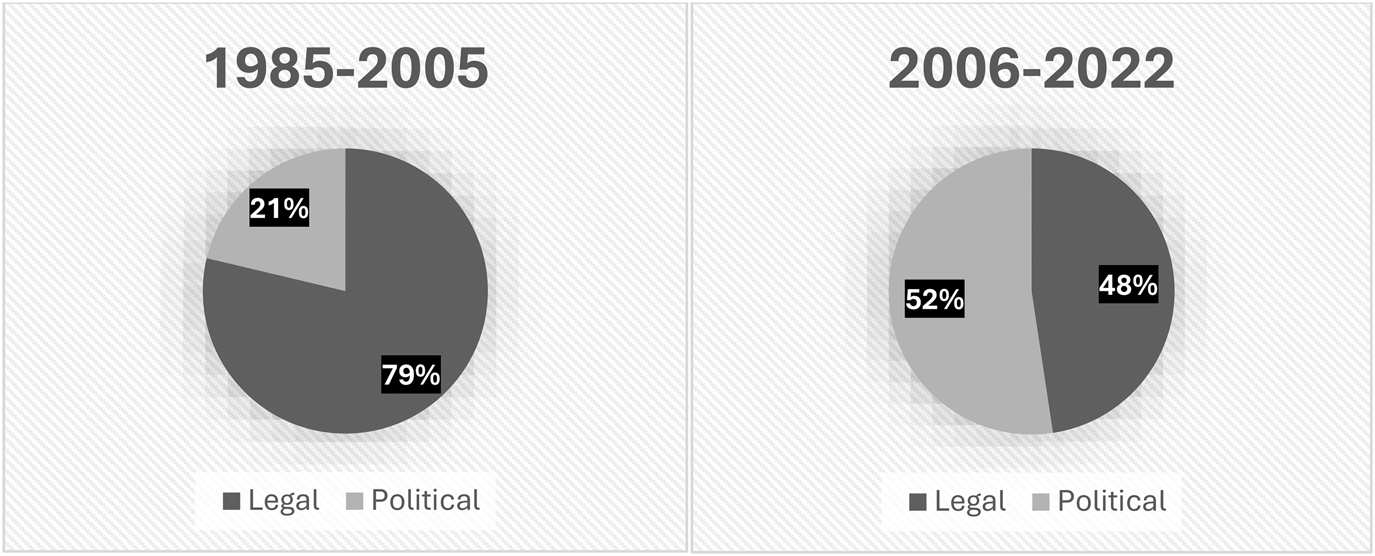

Figure 2 lends additional support to the contention that LEAF's collective action repertoire since approximately 2006 is distinct from its approach in the 1980s and 1990s, which as described earlier, is the period the extant literature on LEAF addresses. From 1985 to 2005, nearly 80 per cent of the organization's advocacy-related activity entailed legal mobilization. In this respect, LEAF's early involvement in political mobilization, such as participation in legislative proceedings, was more of an ad-hoc and sporadic strategy, rather than central to the organization's routine advocacy. In contrast, in the most recent period, LEAF is significantly more engaged in political mobilization. Notably, in the 2006 to 2022 period, the distribution of LEAF's involvement in political and legal forms of advocacy is nearly equal. Despite LEAF being most known for its success in litigation, it is noteworthy that the organization's involvement in political mobilization now outpaces its participation in court, albeit slightly.

Figure 2. LEAF's Distribution of Mobilization, 1985–2005 (n = 108) compared to 2006–2022 (n = 105).

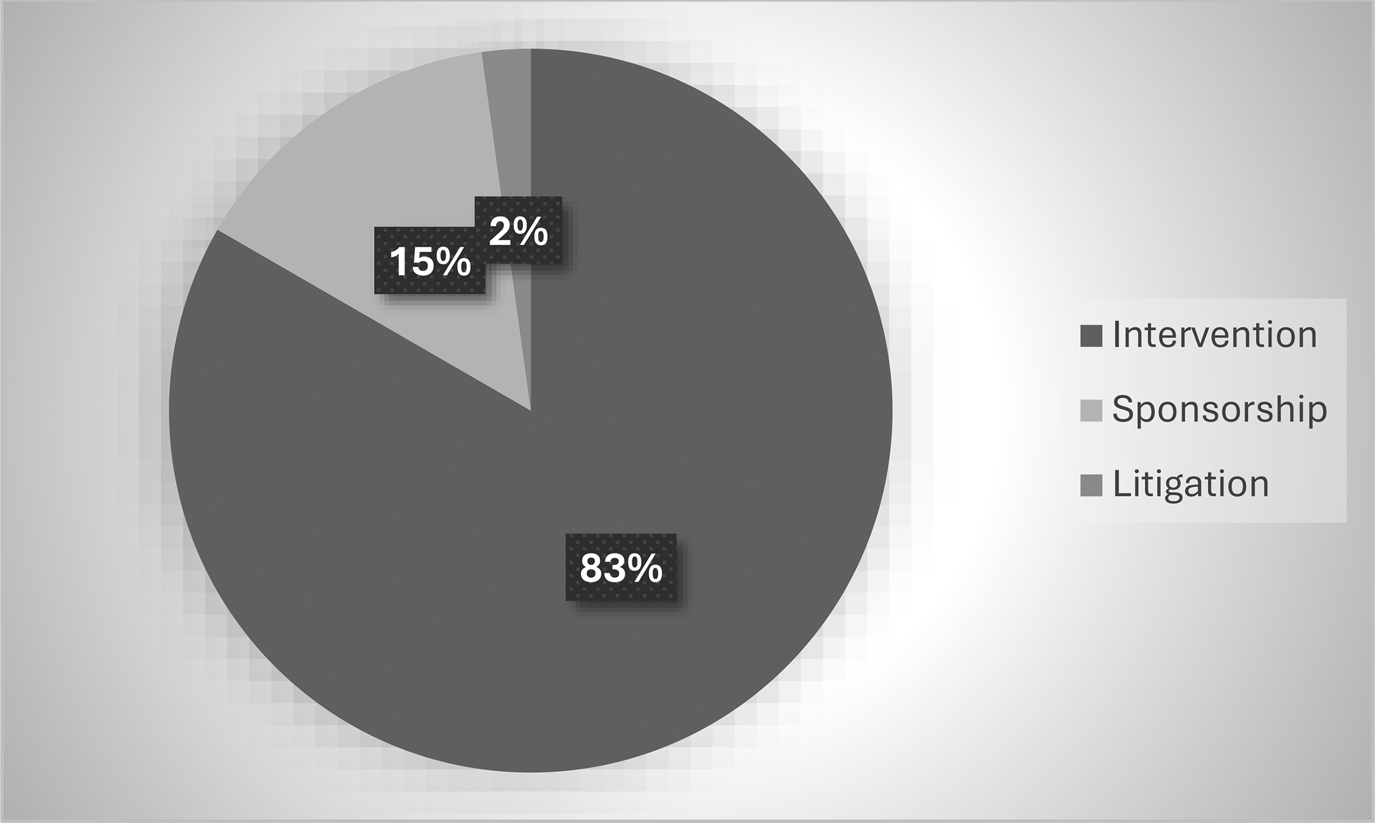

Looking specifically at LEAF's involvement in legal mobilization, slightly more than half (51.85%) of the organization's advocacy has been focused on the SCC (n = 70), although LEAF frequently participates in lower court cases as well (n = 65). For many of the cases the organization became involved in at the SCC level, LEAF also participated in the case in the courts below. In the first decade of LEAF's existence, it sponsored several cases—meaning the organization provided financial support and/or legal representation for external parties to bring cases to court (Hausegger et al., Reference Hausegger, Hennigar and Riddell2015: 221).Footnote 10 The group even undertook litigation itself as a direct, added party to certain cases. This was expected since LEAF was originally created to “assist women with important test cases and to ensure that equality rights litigation is undertaken in a planned, responsible, and expert manner” (Hausegger et al., Reference Hausegger, Hennigar and Riddell2015: 221, quoting Fudge, Reference Fudge1987: 487). However, we find that since 1999, LEAF has not participated in litigation (as an added party), and there has only been one instance of case sponsorship in 2016. Most commonly, LEAF participates in legal cases as an intervener—which makes up 98 per cent of the organization's legal mobilization activity since 2006. As demonstrated in Figure 3, 83 per cent of all its legal mobilization over the entire 37-year period has involved intervening in court cases.

Figure 3. Forms of Legal Mobilization adopted by LEAF, 1985–2022 (n = 135).

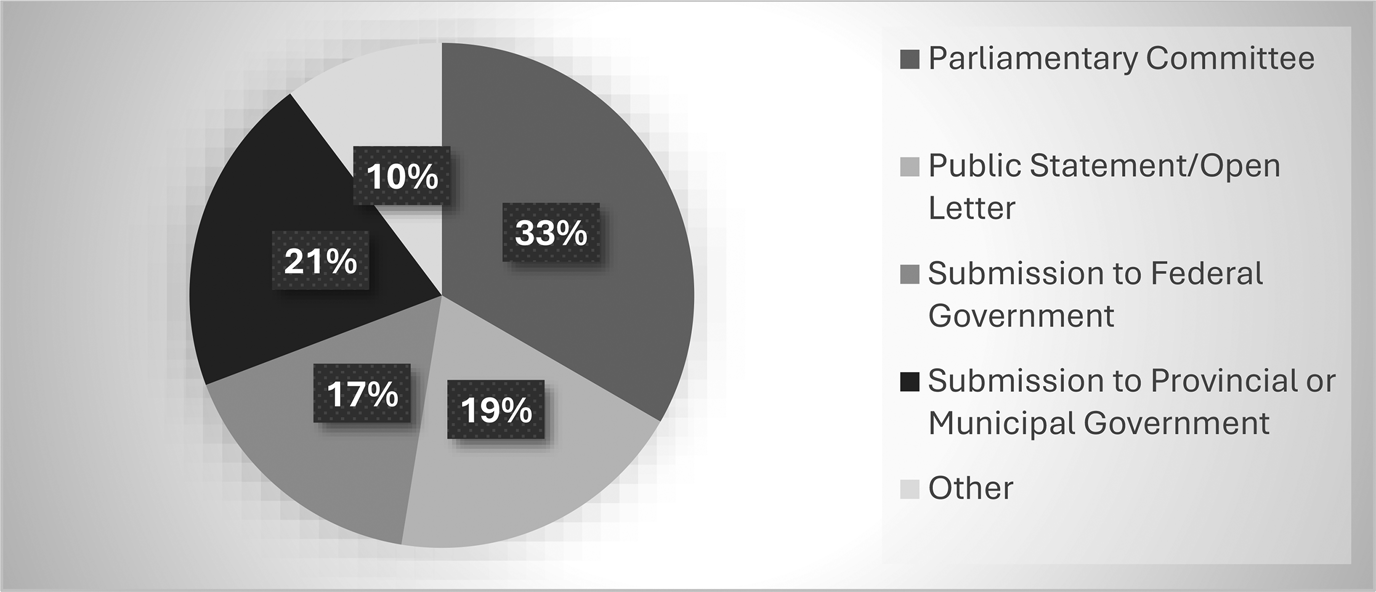

In terms of LEAF's political mobilization activities, Figure 4 illustrates that the organization is engaged in a wide variety of arenas and strategies. Most commonly, LEAF participates as a witness in parliamentary committee hearings, both in the House of Commons and the Senate. Interestingly, and perhaps in light of the federal structure of Canada, LEAF is also an active participant in provincial legislatures and municipal chambers, which makes up 21 per cent of its political mobilization activities. Outside of making direct submissions to legislative bodies, LEAF also publishes open letters and public statements with relative frequency. Notably, we find that much of this participation in traditional forms of political mobilization did not become a routine part of LEAF's collective action repertoire until the 2010s. In fact, 62.82 per cent of LEAF's political mobilization occurred in the most recent decade, with only a handful of appearances in legislative and other political processes throughout the organization's first three decades.

Figure 4. Forms of Political Mobilization adopted by LEAF, 1985–2022 (n = 78).

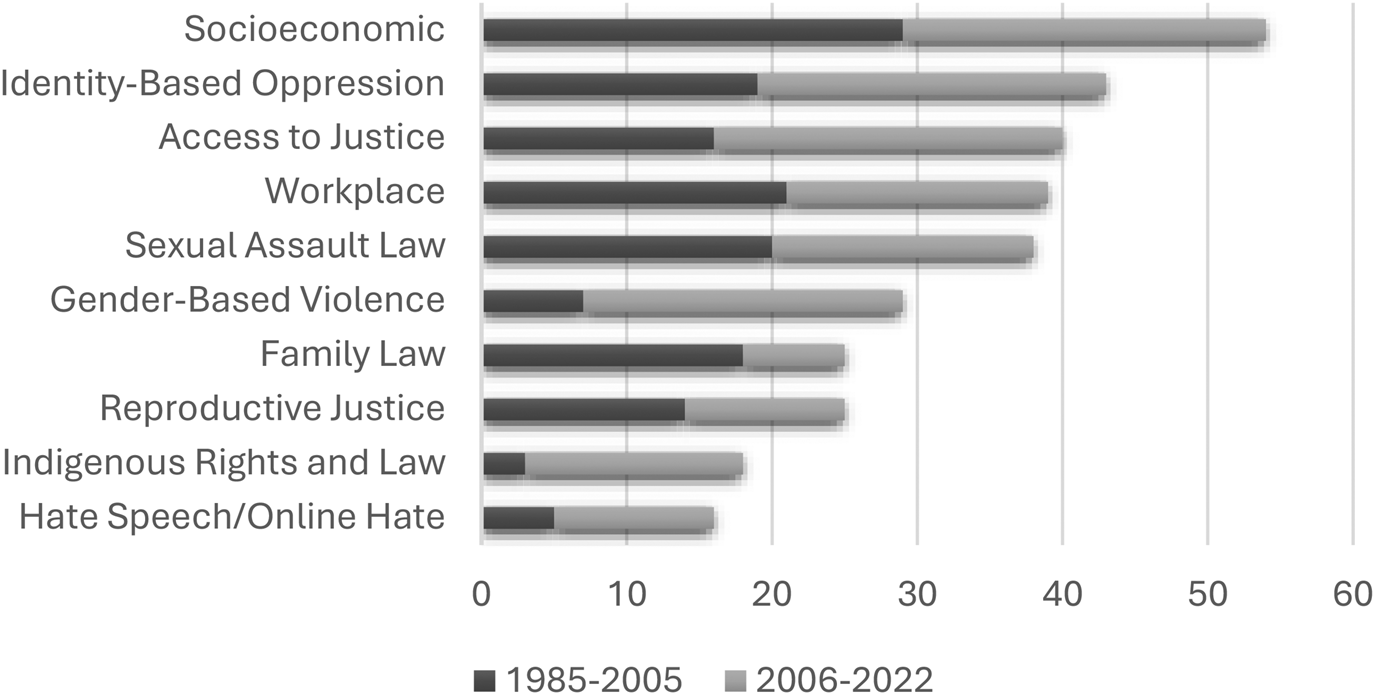

We can see from Figure 5 that not only has the organization's strategy of advocacy evolved, but so too have the areas in which the organization focuses these efforts. Between 1985 and 2005, LEAF's advocacy primarily addressed women's socioeconomic rights, women's equality in the workplace and the law of sexual assault and consent. But we can see that over time, LEAF's advocacy has de-emphasized certain issue areas, while expanding into others. Compared to LEAF's first two decades of advocacy, the organization is less involved in issues surrounding family law and reproductive justice.Footnote 11 In contrast, the greatest growth in LEAF's advocacy focus has been in Indigenous rights and law, predominantly on the issues of violence against Indigenous women (including the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls crisis) and sex discrimination in the Indian Act.

Figure 5. LEAF's Focus of Advocacy 1985–2005, 2006–2022i.

iThe total of this table equals 327 (rather than 213 activities) because these tags of advocacy are not mutually exclusive; many activities were tagged with more than one issue area.

The findings here suggest that prior to 2006, Indigenous rights and law, as well as hate speech/online hate, and gender-based violence, which is defined by LEAF as “acts of violence committed against women, transgender and gender diverse people on basis of their gender, gender expression or perceived gender” (LEAF, n.d.), were all marginal issues for LEAF's advocacy. Whereas other issues like sexual assault law and sex and gender-based discrimination remain central to LEAF's advocacy across both periods.

Finally, even with LEAF's diversified tactics and focus, the organization's collaboration with other civil society actors has remained relatively consistent over time. Indeed, the average rate of collaboration is similar across both periods, with nearly 40 per cent of all advocacy-related activities undertaken with at least one other organization. LEAF's most frequent collaborators are other feminist organizations, including West Coast LEAF, the DisAbled Women's Network (DAWN), the Barbara Schlifer Commemorative Clinic, and the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC). However, there is modest evidence to suggest that LEAF's engagement with collaborative advocacy may be increasing, as the organization reached its highest levels of collaboration in 2017 and 2020, respectively.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Since its founding in 1985, the Women's Legal Education and Action Fund has been a key player in Canadian courts. Our findings reveal, however, that over time, LEAF has diversified its collective action repertoire to engage more extensively with forms of political mobilization. Contrary to scholarly accounts that implicitly frame LEAF as an organization which predominantly, if not exclusively, pursues change through the courtroom (Manfredi, Reference Manfredi2004; Morton and Allen, Reference Morton and Allen2001; Morton and Knopff, Reference Morton and Knopff2000), our study shows that LEAF, in its contemporary form, undertakes forms of legal and political mobilization at similar rates. Likewise, the organization's focus has evolved, with greater attention given to issue areas such as Indigenous rights and law, hate speech/online hate, and gender-based violence. This study makes clear that LEAF, and perhaps CSOs more generally, are rational, strategic and dynamic organizations, who adapt their behaviour and activities over time. While future research is warranted to disentangle the specific causal factors that explain LEAF's evolution in advocacy, it is worth briefly speculating on these potential causes to contextualize the organization's strategic and dynamic decision-making.

We identified 2006 as a loose turning point, where LEAF begins to routinely diversify its advocacy—engaging more extensively in political mobilization. While it is possible that LEAF's shift in advocacy post-2006 could partially result from changes to the funding context—namely the cuts to the CCP program, the fact that the program's first shutdown in 1992 did not appear to decrease the organization's legal mobilization activities, nor prompt significant growth in political mobilization, weakens this possibility. Instead, LEAF's evolution in advocacy may be better explained by the organization's professionalization. With nearly twenty years of experience at this point, LEAF's diversification of tactics might reflect the organization's growth and developed expertise. As LEAF was originally founded to primarily undertake litigation, it is unsurprising that the organization was minimally engaged in forms of political mobilization during its first two decades of existence. However, as LEAF began to occasionally participate in legislative proceedings and other forms of political mobilization, the organization was inevitably building its capacity and knowledge of how best to pursue advocacy outside of the courtroom, and in the process, fostering an appreciation for how a multifaceted approach to advocacy can be beneficial in pursuing one's goals. Thus, the organization's increased involvement in legislative and other political processes over time is perhaps a manifestation of LEAF's developed expertise and motivation to participate in political mobilization.

Related to LEAF's professionalization, the organization and equity-deserving CSOs more generally, may have come to realize the limits of seeking change through the courts alone. Compared to the 1980s and 1990s, the SCC has seen record-high numbers of interveners participate in its cases (Alarie and Green, Reference Alarie and Green2010). At the same time, the court has made efforts to rein in intervener participation, such as in 2017 when the court reduced the time allotted for intervener oral arguments from ten minutes to five. Within this context, and considering the finite resources of CSOs, LEAF may be less inclined to intervene (than it once was), based on the perception that their time and resources could have a greater impact using alternative forms of mobilization. There has also been a dearth of section 15 cases at the SCC in the past decade, limiting the available opportunities for LEAF to intervene.Footnote 12 More critically, however, while LEAF secured several important victories in expanding and defining section 15 jurisprudence in the early days of the Charter, courts control neither the “sword nor purse,” meaning that organizations are limited in what can be achieved through litigation alone. Gerald Rosenberg (Reference Rosenberg1991) famously described the courts as a “hollow hope” for groups seeking to enact social change through legal mobilization. As he explained, “courts are not all-powerful institutions. They were designed with severe limitations and placed in a political system of divided powers. To ask them to produce significant social reform is to forget their history and ignore their constraints” (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1991: 429). In essence, the impact of court decisions is constrained by the reality that courts lack mechanisms to independently enforce their decisions. There is a great deal of scholarship that empirically demonstrates this phenomenon in Canada, including works by Riddell (Reference Riddell2004) and Chouinard (Reference Chouinard and Macfarlane2018), which document how court decisions (in the area of official minority-language education) have, at times, been undermined by governments’ lack of implementation. With this in mind, LEAF's increase in political mobilization may signify a greater awareness of the limits of legal mobilization, where the organization has consciously decided to undertake more advocacy that directly targets the decision-makers who have power over implementation.

Not only is LEAF's dynamic approach to advocacy expressed through its change in tactics, but similarly through its expanded focus of advocacy over time. LEAF re-orienting its mandate to focus on issues such as Indigenous rights and law, hate speech and online hate and gender-based violence likely represent a strategic response to exogenous political factors such as the evolving policy priorities of governments. For instance, the federal government did not begin to robustly legislate in the area of gender-based violence until the 2010s. In 2014, the federal government under Harper introduced the Action Plan to Address Violence and Violent Crimes Against Aboriginal Women and Girls, and in 2017, under Trudeau, implemented the federal Gender-Based Violence Strategy, which articulated that the government would focus more policy attention on issues relating to gender-based violence. Thus, LEAF's greater involvement in gender-based violence advocacy post-2006 could be conceived of as a deliberate response to the agenda-setting of governments and other state actors. In the same vein, as the federal government focused more attention on Indigenous issues in the years leading up to, during, and following the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, LEAF's advocacy around Indigenous rights and law issues correspondingly increased during this period of time.

Additionally, LEAF's evolving focus of advocacy can be situated within the organization's deliberate attempts to become more inclusive of diversity and responsive to the expectations of its membership. As mentioned earlier, LEAF recently updated its mandate to include transgender women and nonbinary people. In the past, LEAF has been subjected to significant criticism for not tending to diversity between women. For instance, Razack argued that in its early advocacy, LEAF only regarded issues of racial discrimination in an additive way (1991: 57). This is to say that the organization has not typically presented arguments around the specific experiences of racialized women, focusing instead on universalizing arguments about women as a broad, monolithic category. In 2019, the organization undertook its Feminist Strategic Litigation (FSL) project, which focused on systematically modifying its approach to litigation to be intersectional and responsive to the “social, economic, and legal realities” of the twenty-first century. In their plan, LEAF committed to prioritizing “reconciliation and to amplify and affirm Indigenous voices and systems” (LEAF FSL Report, 2022). In this way, LEAF's shifting agenda of advocacy is perhaps one manifestation of the organization's goal to become more inclusive and responsive to the specific needs of women from equity-deserving communities, particularly Indigenous women. Ultimately, in broadening the scope of its mandate and taking steps to collaborate with organizations that represent marginalized communities, LEAF may be better equipped to respond to the unique challenges and issues racialized and Indigenous women face, among other categories of women previously overlooked in the organization's advocacy.

Although future research is needed to validate the underlying causes of LEAF's evolution, we can conclude from these findings that LEAF is clearly a dynamic and strategic CSO. The significant change in LEAF's approach to advocacy identified in this study matters significantly, as it reflects the importance of studying advocacy through a longitudinal lens, and with methodological and theoretical approaches that account for the diversity of tactics within organizations’ distinct collective action repertoires. Previous political science scholarship has made clear the important contributions LEAF has made towards advancing women's substantive equality through legal mobilization. However, the literature's narrow focus on LEAF's participation in the courts has made hidden the organization's engagement in political mobilization, and as such, has limited our understanding of the complete nature and impact of LEAF's advocacy efforts. Likewise, as nothing substantive has been published on LEAF in twenty years, our understanding of LEAF has been significantly time-bound. Earlier studies are based solely on LEAF's experience in the immediate post-Charter era, a highly distinct period of time. As LEAF continues to be frequently referred to in studies of mobilization and taught in Canadian law and politics courses, tracing LEAF's advocacy longitudinally has provided an important update to our understanding of how the organization has evolved and what its collective action repertoire looks like today. Ultimately, the empirical record provided contributes significantly to both the Canadian law and politics and civil society literatures, by offering a comprehensive picture of LEAF's legal and political advocacy since its inception. While legal mobilization remains an important arm of LEAF's approach to advocacy, future studies of LEAF ought to move beyond the judicial-centric approach. LEAF's political mobilization now outpaces its activity in the courtroom—and the scholarship needs to account for this substantive change.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the CJPS editors and anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. We also wish to thank Emmett Macfarlane for providing constructive comments on an earlier draft of this article, and Andrea Lawlor for providing advice and support.