Land, Class, Kinship and the Future: Facing Downward Mobility in the ‘New Kenya’

Bookending this work, Mwaura’s story captures its intertwined topics: the expropriation of patrilineal land on the outskirts of an expanding city; the concomitant production of land-poor and landless youth through this process of land sale by senior men; and the hollowing-out of the moral economy of patrilineal kinship. Kimani’s sale of his ancestral land throws into relief the intertwined nature of kinship, land, and class in central Kenya – where access to land is mediated by the family, and where its loss is pushing younger kin further towards reliance upon cash, heightening their exposure to economic uncertainty. Land sale thus accelerates a longer-term, slower process that has been afoot in the region’s political economy since the colonial period: increasing pressure on dwindling plots of land, and the exposure of younger generations to the insecurity of land poverty and landlessness outright. This slow-burn process of proletarianisation shapes the struggles of Kiambu families, especially their young sons, to dwell in the future, to achieve middle-class status, to ‘make it’, in colloquial terms, to the ‘stability’ associated with it.

At an empirical level, the ethnographic observations of this book affirm the conclusion of Orvis (Reference Orvis1993), who suggested that, over time, Kenya’s ‘middle peasantry’ would transform through population pressure into ‘worker-peasants’ no longer capable of commercial agriculture but practising ‘straddling’ livelihoods across town and country (see also Fibæk Reference Fibæk2021). ‘A new process of class formation is underway’, he wrote, ‘but one that is more complex and slower than the proponents of the proletarianisation thesis suggest’ (Orvis Reference Orvis1993: 45). Orvis recommended looking within households and studying their economic trajectories over time to understand the process of class formation. My book has attempted to do precisely this, exploring inter-generational economic lives shaped by land and inheritance.

As we have seen, on the edges of an expanding Nairobi, the process of de-peasantisation is met by a peculiar opportunity: for landowners to sell for windfall amounts of money. The question is, who benefits? Senior men within their patrilines who possess their land in freehold are essentially the winners of history – holding their land at the vital moment where its size is negligible but its value high. The consequence of freehold, however, is the capacity to exclude – to sever family ties and hoard the wealth of land sale. Of course, there are also other ways for a peasantry to make good on the frontier – to construct housing and ‘assetise’ their land. Orvis was right to say that class formation is complex and slow. There are clear winners, such as Mama Nyambura, and unfortunate losers, like Mwaura. For younger men, the proletarianisation thesis of Apollo Njonjo (Reference Njonjo1981) holds increasing weight, especially when we look at the figures of younger generations who are forced to generate ‘off-farm income’ (Kitching Reference Kitching1980: 3) to construct houses and access adult life – to marry, to have children, to live a middle-class life. As in Kitching’s (Reference Kitching1980) thesis, off-farm income takes different forms in different households. For some, it enables accumulation. For young men, it staves-off poverty and offers a glimmer of future hope – that one might slowly save enough money, even to the extent it requires ‘sacrifice’ (Chapter 7).

In this regard, the book provokes further reflections on the topic of ‘class’ in Kenya and Africa more generally. When I began my fieldwork in Ituura in 2017, the hopes Mwaura’s family had for his future reflected then recent shifts in mainstream political commentary about the African continent, specifically the prospect of a middle-income, middle-class Africa. The now famous cover of The Economist magazine ‘The hopeful continent’, transformed from the ‘hopeless one’ of a decade earlier, encapsulated these transformations. After the end of Daniel arap Moi’s de facto one-party rule in 2002, the nation’s ‘second liberation’ under Mwai Kibaki promised a ‘new’ Kenya defined by political and economic liberalisation. New infrastructure projects and the opening of Kenya’s economy to foreign capital created growth, raising expectations for better lives. By the time it came to power in 2013, Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party government made much of its intention to make Kenya a middle-income country.

By 2022, this narrative had given way to a renewed pessimism. A cost-of-living crisis had been brewing since 2018, when the slow-down of the economy after the 2017 elections failed to pick up. Rising VAT on goods created crises in the budgets of Kenyans on low incomes (Kahura Reference Kahura2018). For many of my interlocutors in Kiambu, the years since 2018 have been a time of growing economic struggle as these post-election woes quickly morphed into a full-blown crisis during the Covid-19 pandemic, when government curfews put informal sector work into a state of suspended animation. In Mwaura’s case, these wider events overlapped with those playing out within his family. While his fortunes were shaped by his family circumstances, his fate over the course of this book – his transformation from hopeful student to destitute graduate – captures what I think of as the end of an era of heightened aspiration in Kenya and the beginning of a new one, of heightened anxiety about the elusive nature of middle-class security. By 2022, many of my interlocutors in Ituura were expressing their desire to leave Kenya to find work in the Middle East and beyond. Across Kiambu and Nairobi, they articulated a loss of faith in Kenya’s future and the possibility of living a good life there. ‘If I could, I would leave’, Gathu told me over WhatsApp that year.

This simmering reaction to declining living standards and bleaker prospects for future social mobility turned the 2022 elections into an opportunity for a protest vote against the ruling Jubilee government. It had been in power for two terms. Voters from across central Kenya had grown frustrated with the promises of economic growth made by Uhuru Kenyatta. They felt doubly entitled to hold him to account given that he was himself a Kikuyu from Kiambu. Uhuru had not promised direct distribution, but voters who had lost their jobs during the pandemic and found the cost of basic foodstuffs rising blamed the president who had promised a vision of a middle-income Kenya and jobs for youth. While Uhuru had thrown his weight behind the campaign of former prime minister, Raila Odinga, it was his deputy, William Ruto, who won a major victory, taking central Kenya in a landslide, by promising a ‘Hustler Nation’, a government run in the interests of the working poor (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023b). Several of my interlocutors attached their hopes to Ruto’s campaign. Others simply decided to give his promises a ‘try’, as they described it.

Ruto’s promises of a reduced cost of living through firing-up the farming sector were never fulfilled. Instead, his attempt to address Kenya’s national debt by forcing through tax raises led to mass demonstrations in Nairobi by the ‘Zillennials’, a conglomeration of young Kenyans who have known little in their adult lives but economic precarity (Kahura Reference Kahura2024). My interlocutors from the Star Boyz team went to Nairobi to join these protests. Armed with knowledge about government budgets, they criticised Ruto’s attempt to put further strain on households rather than cut government budgets.

These changing circumstances throw into relief the challenges of achieving the economic ‘stability’ that have been widely discussed in the scholarship when it comes to the so-called African ‘middle class’. To the extent that an African middle class can even be defined, Claire Mercer and Charlotte Lemanski have emphasised its fundamental precarity – that it has hardly been spared from the transformative effects of structural adjustment policies that have shrunk state employment, forcing a reliance on informal sector work (Reference Mercer and Lemanski2020: 434). Lena Kroeker (Reference Kroeker, Kroeker, O’Kane and Scharrer2018) has argued that these precarious middle classes therefore need to guard carefully against downward social mobility through cutting social ties and conserving budgets, a theme we have seen throughout this book (see also Lockwood 2024b). Ruth Prince (Reference Prince2023) has written of the ‘cruel optimism’ (Berlant Reference Berlant2011) that characterises the ever-unfinished quest for economic stability that characterises middle-class life projects in Kenya, especially when best-laid plans are easily curtailed by contingent crisis in a country that lacks meaningful welfare provision. Surveying this landscape of economic turbulence and the difficulty of defining a middle class, Henning Melber (Reference Melber2016, Reference Melber2022) has questioned whether one exists in Africa at all. Working at an even broader level of global commentary, Hadas Weiss (Reference Weiss2019) has framed middle-class status as an inherently elusive category, an endless search for economic security.

Instead of hard-and-fast ‘classes’ in the conventional use of the term, this book has emphasised class as a process of differentiation – the upward and downward pathways lives take towards and away from economic security (Peters Reference Peters2004), a meaning of the term closer to Jane Guyer’s (Reference Guyer2004: 149) notion of a ‘social gradient’. I have retained the use of the term ‘class’ to illustrate a historical process of economic differentiation that is today defined by the emergence of winners and losers at the edge of the city.

More than the process of class differentiation alone, the book, and Mwaura’s story within it, also highlights something missing from these accounts of African middle classes. This is the significance of property – not just any sort of property, but inherited land in particular – in an economy where well-paid work is elusive. Literature on the middle class in Africa has tended to focus on well-off demographics of civil servants and other salaried workers, and paid work in general, as a means to social mobility. Of course, Kenya barely differs from many other contexts under capitalism where property’s value outstrips that of wages or capitalist production and profit (Piketty 2014). Yet, under these conditions, this book has observed the integral role property plays in middle-class projects of seeking economic security and stability. As we have seen, Kiambu residents are certainly not middle class in the way existing scholarship paints it. They are ‘somewhere’, as Mwaura once put, and Ituura is neighbourhood of mixed fortunes. Regardless of this differentiation, inherited, ‘ancestral’ land gave them the possibility of accessing a better life, a critical driver of upward and downward mobility. On the one hand, the capacity to turn it into an asset capable of generating rent promised new futures of economic security – of becoming a landlord by constructing rental ‘plots’. On the other, the loss of land to sale is shown to be a personal disaster for young men, pushing them closer to outright proletarianisation, and closer to pauperisation.

Viewing class formation as a process of differentiation – one that is unfolding in real time – illuminates the economic proximity of demographics otherwise separated by conventions in the academic literature. Anthropologists of Africa have written much about the lives of ‘surplus people’ – they have done so in a range of styles and through a range of rubrics from ‘waithood’ (Honwana 2013) to being ‘stuck’ (Sommers Reference Sommers2012) in the compound (Hansen Reference Hansen2005), to states of ‘boredom’ (Masquelier Reference Masquelier2013) and the choice not to take manual work for the ‘shame’ it engenders (Mains Reference Mains2012). Scholars have described lives in the informal economy in terms of the constant ‘hustling’ (Thieme, Ference, and van Stapele Reference van Stapele2021) required to make ends meet, and the ‘pressure’ to meet obligations (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2024), even to the extent these constitute modes of resilience and hope (di Nunzio Reference di Nunzio2019; Guma et al. Reference Guma, Mwaura, Njagi and Akallah2023).

Mwaura’s fate was to enter this economic terrain, to experience a loss of upward mobility, and to end up in the category of those living ‘wageless lives’ (Denning Reference Denning2010). His life, and the stories of others recounted in this book, show how processes of displacement and alienation afoot in the encounter between urban frontier and rural political economy produce these ‘surplus people’ (Li Reference Li2010) in Africa’s urban informal economies. Those who appear ‘middle class’ and those who ‘hustle’ may thus be separated by very little in economic terms, other than often meagre patches of land. Kiambu families are vulnerable to economic shocks – to school fees, hospital bills (Prince Reference Prince2023) – that have the capacity to push them deeper into destitution. In this regard, a propertied and rentier ‘middle class’ making their land into assetised housing (Chapter 6) and the lives of youth living in ‘waithood’ (Chapters 2, 4, and 7) are demographics that emerge from the differentiated life chances specific to a stratified setting undergoing even further stratification through the approach of the city. This book has provided a portrait of a differentiated economic terrain in which all are struggling for proximity to the future, to ‘belong to the future’, in Constance Smith’s terms (Reference Smith2019), by accessing the type of middle-class lifestyles to which practically all in central Kenya aspire.

Beyond this broader economic context, however, a critical aim of this book – through its focus on land especially – has been to show how entanglement within family dynamics shapes these same struggles to belong to the future. Such a focus warrants a renewed anthropological focus on the intertwined nature of kinship, class, and capital across contexts.

Kinship, Class, and Capital

‘Why is so little attention paid to inheritance in both empirical studies and theories of family and kinship in modern capitalist society?’, asks Sylvia Yanagisako (Reference Yanagisako2015: 489). In the wake of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-first Century (Reference Piketty2017), she suggests that anthropologists have neglected the topic. Yanagisako’s words echo those of Adam Kuper (Reference Kuper2018) in his appraisal of ‘the new kinship studies’ and its effect in social anthropology. In a trend embodied by Sahlins’ (Reference Sahlins2011) ‘What Kinship Is’, the new kinship studies marked a turn towards the symbolic discourse through which kinship is made and the phenomenological experiences through which it is felt, the ‘mutuality of being’. According to Kuper, it marked the abandonment of ‘formal’ kinship relations in the style of Jack Goody, Meyer Fortes, and Edmund Leach, their emphasis on kinship relations as material constellations, including the study of inheritance (Hann Reference Hann2008). In Kuper’s view, the shift from studying material kinship relations towards the symbolic and practical construction of ‘relatedness’ came at the cost of understanding the intertwined nature of family, business, and politics in the twenty-first century. Kuper reprises Leach’s (Reference Leach1961: 305–6) famous argument that kinship ‘systems’ had no independence from land and property relations, and could not be isolated from them as an object of study.

Kuper’s retrospective recalls earlier work by Susan McKinnon and Fenella Cannell (Reference McKinnon and Cannell2013: 16–18) that had made a similar critique of the separation of kinship and economics. Yanagisako’s research on family firms in Italy had already contributed to this renewed focus on this realm of inquiry at the time. This work is now joined by that of a number of scholars interested in inheritance and social mobility amongst middle classes in the Global North (Weiss Reference Weiss2019; Zaloom Reference Zaloom2019). Alongside this renewed ethnographic impetus to study kinship, the Gens Manifesto (Bear et al. Reference Bear, Ho, Tsing and Yanagisako2015) has set the tone for this revitalised area of inquiry, identifying ‘the centrality of kinship to capital accumulation and class relations’. At the same time, consciousness of the immense power of inherited wealth is crystallising in Euro-America’s public debate surrounding downward social mobility and the ‘myth of meritocracy’ (Sandel Reference Sandel2020).

In eastern Africa, and Africa more generally, such themes have never gone away. Studies of kinship and inheritance have remained central to understanding dynamics of change in rural Africa (see, e.g., Berry Reference Berry1985; Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1989; Peters Reference Peters2002, Reference Peters2004, Reference Peters, Grinker, Lubkemann, Steiner and Gonçalves2019; Amanor Reference Amanor2010; Droz Reference Droz, Jindra and Noret2011; Cooper Reference Cooper2012; Boone Reference Boone2014). The importance of these insights into the ‘land question’ in rural Africa looks set to grow as the approach of cities into rural contexts intensifies the commodification of land.

While refusing to romanticise African modes of kinship and relationality, this book has maintained the importance of understanding land dynamics through notions of moral economy – through the hollowing-out of patrilineal kinship’s principles of inheritance in the face of land’s commodification. If at a broader scale we can see the way the commodification of land turns kin into strangers, moving them into separate classes, the question for anthropologists is how people understand this breakdown, and what it means for the future of kinship’s moral economy of landholding and inheritance. I have described a crisis of faith in the form of patrilineal kinship envisioned by mainstream discourse, oriented around the figure of the male breadwinner, returning wealth to the homestead and the family. To young men at the sharp end of economic insecurity, such a world seems nigh impossible. We have seen some men actively consider ‘giving up’ and ‘wasting themselves’ instead of holding on to such futures because these are seen as materially untenable. The most egregious effects of this loss of hope came in the form of land sale, as senior men ‘cashed out’ of the patriline and the effort required to sustain it, becoming personally rich instead. But as we have seen, a pervasive feeling amounts that everyone is trying to ‘escape’ rural poverty, compounding feelings of abjection for those left behind on the homesteads. Mwaura looked at his sister as someone who could survive peri-urban poverty better than he could if she married out of the neighbourhood. More generally, male anxieties about women’s intentions further undermined belief in the possibility of a harmonious patrilineal household.

Chris Hann (Reference Hann and Hann1998: 33) has wondered if discontinuity and disembedding arguments in anthropology have been given ‘sufficient consideration’. ‘Public and “moral” aspects of property relations’, he writes, ‘atrophy, and considerations of short-term gain overwhelm long-term values’. But how can social anthropologists make visible and, indeed, understand the moral economy’s ‘atrophy’?

Nancy Munn (Reference Munn1986) has put forward one of the most promising theories of the way economic transactions undermine and shift moral principles, bringing forth new, individualist notions of morality and personhood. Her fieldwork amongst the Gawa demonstrated how social practice oriented towards social reproduction was carried out in the constant knowledge that it could be subverted by ‘witches’ – figures who decided to consume resources rather than purpose it towards the future. Munn’s work provides a theory of the vulnerability of collective projects to individual orientations towards private accumulation.

Munn’s groundbreaking work finds resonance in an essay by Andrew Walsh (Reference Walsh, Browne and Milgram2009) where he examines ‘the inherent fragility of all systems of moral and economic exchange in which reciprocity and confidence play key roles’ (Reference Walsh, Browne and Milgram2009: 59). In the context of a diamond rush, residents in a Malagasy town are shown to get ‘burned’ when exchanges ‘go wrong’, for instance, when buyers of precious stones fail to pay. Walsh’s question is what keeps exchange relationships going, in spite of the knowledge that they can be disrupted or halted. ‘One of the things that compels people to act in ways that keep such systems going’, Walsh writes, ‘is confidence, and more specifically, their confidence in the integrity of these systems’ (Reference Walsh, Browne and Milgram2009: 63). Moral economies, James Carrier has written, congeal over time through repetitive interactions that shape a sense of obligation, corresponding with Polanyi’s notion of ‘embeddedness’ (Carrier Reference Carrier2018: 28). If Carrier’s approach holds, and I believe that it does, the reverse must be possible – that moral economies can be undermined, in real time, through acts of what Marshall Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1972) called ‘negative reciprocity’, the avoidance of obligation and the prioritisation of individual interests at the expense of others.

As Walsh (Reference Walsh, Browne and Milgram2009: 64) writes, ‘we can know that people’s confidence in the integrity of systems of social and economic exchange exists because we can observe it being shaken’. Kiambu marks a setting where patrilineal kinship’s moral horizon is being undermined by an accumulation of tangible acts of ‘cashing out’. Anxieties that kin, even siblings, will betray one’s interests have become pervasive because of knowledge about other cases in which this holds. This marks a setting on the cusp of change, not simply the approach of an urban frontier into a post-agrarian landscape, but the increasing tenuousness kinship obligations in the face of commodification.

Insofar as we are dealing with perceptions of moral rupture at the heart of kinship, they prompt a reprisal of E. P. Thompson’s (Reference Thompson1971) notion of ‘moral economy’, a term widely used and applied in anthropology to describe the types of mutuality produced in embedded economies. As Marc Edelman (Reference Edelman and Fassin2012) has noted, Thompson’s use of the term ‘moral’ was to evoke not only notions of waning custom but also moral critique – the impassioned response to moral transgressions, the voice that appealed to reason and justice (Gluckman Reference Gluckman1965) just at the moment that old paternalisms were on the wane. In the context of land sale, Kiambu ‘moral economy’ of patrilineal kinship is shown to possess an increasingly empty quality, operating a language of claim-making and criticism that stands apart from actual practice. In short, it has no ‘normative’ policing capacity. Mwaura criticised the hypocrisy of his father, though he had limited recourse to find justice for his predicament. He too considered selling land. And insofar as he critiqued his father, his critique was muted. Such social dramas are kettled within the family, and they are sources of individual privation and senses of shame. On Nairobi’s urban frontier, tensions between historical experience, customary practice, and moral expectations take place neither on the factory floor nor in riots against the mill but rather privately, within the family.

Mwaura’s personal realisation was that patrilineal moral discourse about retaining ancestral land was just that – a narrative. His realisations dovetailed with my own shifting analytical frame. In 2018, as a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, I was presenting early versions of this book’s Chapter 3 that emphasised Kimani’s dogged determination to go against the grain of land sale. I had embellished his own account of himself in a first-person virtue ethics. Unfolding events shifted my perspective, making me recognise the hollowness of those discourses, their failure to bind. I began to see them as something closer to a ‘lament’, in the terms of Robert Blunt (Reference Blunt2019), especially when ideas about the immorality of sale are used by young men like Mwaura as critiques rather than the men who sought to vaunt their determination to retain land. Distinct from anthropological theorisations of hope – which often explore the way beliefs in future prosperity are eroded through economic conditions – what I have described here is lost belief in a moral system, in a moral economy of patrilineal kinship as a set of obligations possessed by senior male heads of household towards younger kin. As Walsh writes, ‘moral transgressions do more than just upset people, they can quite easily ruin them’ (Reference Walsh, Browne and Milgram2009: 64). The loss of land accelerated Mwaura’s entry into the informal economy, his thorough proletarianisation. This brings me to a subsequent question I wish to conclude. How effective is faith in the labour theory of success in light of this dawning pauperisation?

Labour Theory Revisited

‘Proletarianisation’ evokes a long-term historical process of severance from land and reliance upon wages, but the predicament of pauperisation suggests utter destitution: landlessness and jobless combined. This book has set out to explore its subjective experience: the way land poverty and a lack of available jobs consign young Kiambu men to lives of stagnation and alcoholism. Where the narrow space of the homestead becomes a site of boredom and idleness, what wages can be gleaned hardly support the type of middle-class life one is expected to lead. In Kiambu, this manifests in what Mario Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2024) has called the ‘pressure’ experienced by young men to become breadwinners, to meet expectations of becoming a successful accumulator and provider. But if pressure can be coped with to some degree, pauperisation evokes the sense in which hopes for better futures are exhausted, giving rise to the demoralised states of being that provoke the abandonment of the future itself, the onset of depression, heavy drinking, and suicide.

This is not the ‘waithood’ described by Adeline Masquelier (Reference Masquelier2013) and Daniel Mains (Reference Mains2012), whose interlocutors were predominantly graduates hoping for white-collar jobs and who were able to retain a degree of optimism and agency regarding their futures. This is a peri-urban poverty defined by heavy alcohol consumption and low life expectancies. The consequences of de-peasantisation are therefore closer to Ferguson’s (Reference Ferguson1999) narrative of ‘abjection’ that he identified on the Zambian Copperbelt in the aftermath of the privatisation of the mines in the wake of International Monetary Fund–imposed structural adjustment. As with the Zambian Copperbelt, Kiambu’s poor embody the contradictions of capitalism’s capacity to grow in uneven ways, giving rise to certain spaces and populations disconnected from its wealth and ‘growth’. Across Africa, a lack of manufacturing has created a growing number of ‘surplus people’ whose labour is more than capitalism’s requirements (Iliffe Reference Iliffe1987; Li Reference Li2010). The lives of Kiambu’s youth are a testament to these vicissitudes – that capitalism can create an impoverished hinterland on the border of a city growing through property speculation. Rather than ‘destructive exploitation’ (Meillassoux Reference Meillassoux1981), capitalism’s calling card in rural Africa is a form of destructive exclusion. The moral experience of class formation in Kiambu was of a deeply unsettled masculinity, of patrilineal futures untethered from land and of a deepening struggle to create and maintain households.

In this context, this book has asked: how the peri-urban poor maintain their hopes for a better future, if at all? To frame the answer to this question, I have drawn upon Bourdieu’s writing in Pascalian Meditations (Reference Bourdieu2000: 222) on the experience of time without work where work and labour are inextricably connected with self under capitalism. I have sought to explore how a tangible recognition of diminished life chances provokes a destructive short-termism. I maintain that such an interpretation of these experiences is not to indulge in miserablism, but a study of how diminished material possibilities for living a good life turn young men towards living in the short-term, towards forms of ‘impatient accumulation’ and ‘immediate consumption’ (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2020b). This is no automatic movement. Men understand the terms of the economy, remarking upon their limited possibilities for thriving within it – that ‘we don’t have much longer’. Such words speak to the narrowing material terms upon which moral agency can be exercised, a crisis of knowing ‘demoralisation’ (Rajković Reference Rajković2018).

This book has studied the moral and moralising arguments being had about how to live on the cusp of full proletarianisation, the challenges of holding on to a labour theory of success and virtue, of believing that work can ‘push’ one where one wants to go. These are debates in which men struggle to mobilise the last vestiges of belief in the future. I have shown how Kiambu youth with grand ideas accepted the need to ‘start from the bottom’ in concerted contrast to others who apparently waited in hope for a ‘connection’ or windfall money that would immediately transform their lives. Their confrontation with their pending pauperisation was defined by this self-conscious humility, an acknowledgement of the necessity of scrimping and saving one’s way to success. But gone from this younger generation was the pride and self-valorisation of Kiambu’s senior men who had claimed virtue through retaining landed assets and becoming judicious economic managers. Kiambu’s young men faced a distinct problem: one of ‘hanging on’ (Weiss Reference Weiss2022) to aspirations for homesteads and lives like their fathers. As we have seen in Chapter 3, working-aged men who had already met the material limits of this struggle evinced a cynicism towards obligations to kin, a conscious turning away from its vision, and an embrace of consumption. Young men like Roy looked on at their ‘wasted’ elder brothers and remained determined not to meet the same fate. I have described this challenge as an ethics of endurance, a personal terrain of moral endeavour in which the will to keep going and avoid ‘giving up’ is a constant concern.

To highlight the predicament of Kiambu’s young paupers is to shed light upon the critical work of women sustaining futures for their young adult sons. Representations of Kiambu women as ‘selfish’ or ‘greedy’ speaks to male anxieties about their inability to live up to expectations (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2024) while obscuring their own work reproducing the household. The work of Sibel Kusimba (Reference Kusimba2021) has stressed women’s central role, in neighbourhoods and extended family networks, in generating funds for schooling, medical costs, and everyday household needs. Prince (Reference Prince2023) has written recently of the way middle-class women diversify their savings and investment strategies, lacking sufficient wages to be able to avoid undertaking such de-risking activity. The cause of this in Kiambu has been the failure of male livelihoods, rendering women breadwinners not always by entering the market, but through drawing upon limited resources of relation-making, ‘stratagems of civility’ (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023c) that see them draw close to a range of potential patrons. The search for relations of ‘dependence’, as Prince (Reference Prince2013) has also observed, is a fraught and uncertain practice in a context where access to cash is mediated by those few neighbourhood figures who have well-paying jobs (see also Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023b).

Under the pressing conditions that this book has described, it is hard to ignore the collapse of belief that work can allow one to create a good life. At the sharp end of economic privation, moral narratives that confer virtue upon struggle in the informal economy have reached their limit, giving way to forms of self-destructive consumption, the ‘giving up’ on the future that characterised the lives of men like Stevoh, Ikinya, and eventually even Mwaura. His loss of his dreams of social mobility and his own descent into alcoholism provides a desperate instance of this – that destitution can hardly be avoided, that work options rarely offer opportunities for accumulation consonant with the degree of aspirations. The sense that middle-class lifestyles are beyond these men foments this loss of hope, the production of ‘wasted men’, and a struggle to cling on amidst the economic margins of peri-urbanising Kiambu.

‘A self-confused house’

What might the future hold for patrilineal families living on this urban frontier? One way to answer this question is to return to local reflection upon its approach. On one of the few occasions Mwaura and I attended the local Anglican Church of Kenya, we were happy to discover that ‘stand-up comedy’, as he called it, was well within the acceptable boundaries of sermonising. We watched from the pews as the priest, in his fifties and wearing his vestments, expounded the importance of one’s ‘point of view’, of not giving in to jealousy of others, especially family members. His example was the construction boom, and the grand new apartment buildings it brought – that even those living in them, possessing middle-class lifestyles, were not capable of seeing ‘clearly’.

You know those apartments that have a view. ‘Chungwa Town View.’ You look there and you feel everything! And you know at times that view is not the best. At times that view is bad. But nevertheless, you live in those apartments called Mountain View Estate. But the view may not be everything.

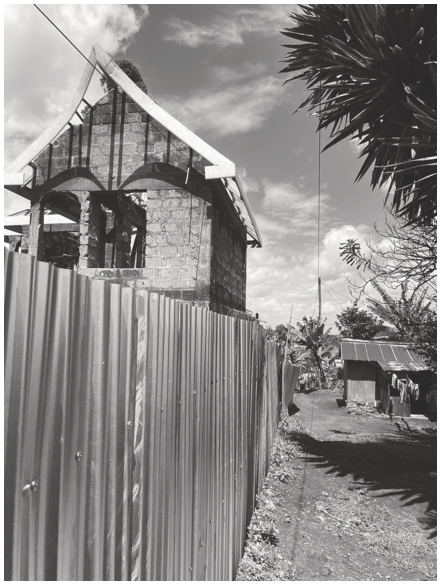

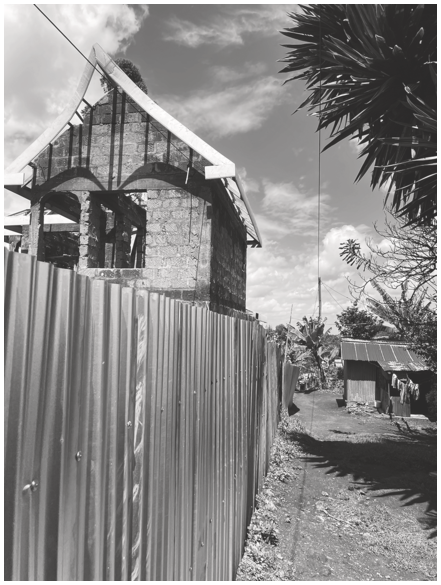

The priest contrasted the view of Nairobi’s nouveaux riches with the ‘view’ of those living ‘downstairs’, the smallholders confined to their homesteads now surrounded by a growing sprawl of new buildings, painting a picture of their neighbourhoods overtaken by a construction boom (see Figure C.1).

You know some people happen to have got a piece of land in 1960 and they were only portioned half that once. In 1980 a neighbour came and built a substandard house bigger than theirs. In the year 1995 somebody got the next plot here and today we are starting to see where their house is because hii [this one], the other 15 floors, this one has 7 floors, and the next one here went for 6 floors, and the one behind was shameless. It went up! [Ilienda juu kabisa!] So I live down this line. I live in between those palatial homes. That’s where I live. And their view is clouded. Their view is clogged by other things. Seeing beyond your view!

Figure C.1 Those who build and those who stay, 2024

Figure C.1Long description

A corrugated iron fence runs through the photo. To its left, the shell of an unfinished two-storey middle-class home towers, connected by power lines. On the right, the red earth leads to banana plants and distant gardens. In the foreground, a corrugated iron home has garments drying on a clothesline in front of it.

The priest encouraged the congregation not to be disheartened by the wealth possessed by neighbours in these ‘palatial’ homes:

Today you might be looking at yourself, poor and broke, shameless and single. You will be looking at yourself living in a small house compared to your friend’s house who is the last born in your family and … you are the first born and you’re still living in a self-confused house. And you’re wondering, where did my brother get the money? Where is the money seeping in? You know those self-confused houses that we live in. They’re called what? Self-contained. Uko kwa mtaa. [You’re in the ghetto, i.e., a single-room ‘bedsitter’] One-stop-shop, you can pick a towel, pick a toothbrush, pick bread, close the bathroom door and you’re asleep in one breath.

Next to me, Mwaura was in stitches at the priest’s tone and the idea that a small, corrugated iron bedsitter could constitute a ‘self-confused house’. The priest went on.

So stop complaining! By the way stop complaining because of the bad things your parents have done for you! So stop complaining your parents are nothing and embrace them! Look for the positive thing in them because they will never change.

The priest exhorted Kiambu’s poor to redouble their efforts, to avoid seeking assistance from others, and to strike out on their own in search of economic prosperity. At the end of the sermon, everyone was asked to give money for the church’s building costs. Mwaura was reluctant, but we gave money anyway. ‘I feel like we just got hustled’, I told him. ‘Me too’, Mwaura agreed. Nonetheless, he was in good spirits. ‘I feel good going to church’, he said. ‘I mean, it was like stand-up comedy.’ We went home to find some breakfast.

Ranging and exaggerated, the priest’s sermon painted an intriguing portrait of the nature of urban change in Ituura – not only of a new landscape of bedsitters, high-rises, and lingering homesteads, but also a feeling of being left behind amongst Kiambu’s peri-urban poor, of being excluded from this new urban future. He evoked an emerging landscape of envy between smallholder kin, struggling to compete with one another for wealth and status. Yet the sermon also described the frustration of the young towards their poorer elders deemed to have done all too little to advance their children’s futures. The priest’s words speak to the experiences of Kiambu smallholders living in close proximity to Nairobi’s approach, the topic with which this book has been concerned. While urban expansion offers tantalising glimpses of high-rise skylines and urban living, it has also animated new anxieties that centre on the possibility of exclusion. To belong to it – to transform one’s homestead into a ‘palatial home’ or constructing plots – marked one’s inclusion in the future of a changing Kiambu, becoming ‘more of Nairobi’, as Mwaura had once put it. Such concerns recall longstanding themes in the anthropology of Africa about desires in Africa to feel connected to a global and globalising world (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999, Reference Ferguson2006), to ‘belong to the future’ (Smith Reference Smith2019) through accessing the types of lifestyles associated with more prosperous parts of the globe. In Kiambu, it was kinship and its inherited wealth that defined these struggles to ‘progress’ to the imagined ‘stability’ of middle-class urbanity. In this respect, changing neighbourhoods like Ituura are microcosms of the contradictions of capitalism across the African continent.

As the city expands and incorporates its hinterlands, these frontiers of commodification and expropriation are shaped in turn by contingencies of land and kinship, of neighbourhood rivalries and deeper colonial histories, the uneven geographies of socio-economic stratification now giving rise to even newer divisions of rich and poor, landlords and paupers. As the value of land outstrips wages to even greater degrees and Kiambu landowners contemplate their own precarious budgets, sales will continue, and tensions of land and kinship will surely only intensify. So too will a persistent feeling, especially for those who find themselves excluded from the windfall money of rural land sales, that the ‘old’ moral economy of patrilineal kinship is no more.