1. Introduction

By the first half of the eighteenth century, the respondentia (or correspondencia a riesgo de mar, as it was known in Manila) had ostensibly become the primary instrument for trade finance in the Spanish Philippines, acting as the contractual linchpin that ultimately connected the silver mines of colonial Mexico to Chinese markets via Manila. During the 250 years of the Manila galleons (1571–1826), the Spanish entrepôt was at the crossroads of exchange between Spanish America and the Greater Indian Ocean World, through routes linking it to an array of ports across China, India, and maritime Southeast Asia. Historians of the Philippines and the Spanish Pacific have tangentially dealt with respondentia contracts as supporting evidence of select financial and commercial transactions, as part of arguments on commercial and interpersonal connections (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007; Gasch-Tomás, Reference Gasch-Tomás2015; Mesquida, Reference Mesquida2018). But the institutional nature of the instrument itself, as a formal mechanism for economic cooperation, has remained unexamined, mainly because there has been no large-scale analysis of extant respondentia contracts.

This article presents the first systematic study of surviving notarial protocols to date, offering a pioneering exploration of the silver-denominated capital markets in Manila during the eighteenth century.Footnote 1 This analysis reveals a “contract monoculture,” where in contrast to elsewhere in the Spanish world, the correspondencia is the only financial or partnership contract that appears in the Manila notarial record. Catering for a trade built on the physical shipment and exchange of silver specie across the ocean, Manila did not have a money market comparable to that which developed in Europe during the Early Modern period, and thus lacked the state-sanctioned institutional infrastructure that often accompanied it, such as giro or public banks. As alternative frameworks emerged based on the need to regulate commercial cash flows, the Manila correspondencia evolved into the institutional underpinnings that bridged transoceanic demand and supply in Manila’s long-distance silver trade and the subsidiary intra-Asian and trans-Pacific commerce. Legacy funds under the management of religious corporations (obras pías) co-evolved in tandem with this institution as an organizational adaptation unique to the Manila context, reducing the costs of pooling capital, monitoring, and enforcement.

Delineating the incentive and enforcement mechanisms of the Manila correspondencia, as a private-order mechanism formalized by public deed, along with its differences to similar contracts in the Spanish Atlantic and elsewhere, is a first step to understanding why it became the instrument of choice for Manila merchants, especially in the context of other formal and informal mechanisms that enabled long-distance, cross-cultural trade in the pre-modern world (Curtin, Reference Curtin1984; Greif, Reference Greif1989, Reference Greif2006; Aslanian, Reference Aslanian2006, Reference Aslanian2014; Trivellato, Reference Trivellato2009, Reference Trivellato, Bentley, Subrahmanyam and Wiesner-Hanks2015). Respondentias presented various similarities to other sea loans (Hoover, Reference Hoover1926; De Roover, Reference De Roover, Postan, Rich and Miller1963); however, under a respondentia contract, an investor would provide a certain amount of cash to a merchant for the purchase of trade goods, which would then be sent to an agreed-upon destination on an agreed-upon vessel for resale. Upon the successful return of the vessel carrying the investment and realized profits, the merchant would repay the investor the principal of the respondentia plus a pre-arranged premium, always denominated as a percentage over the principal. This was conditional on the safe return of the cargo. Thus, the investor agreed to bear the risk of loss at sea, while the merchant bore the market risk.

While following the same template for organizing capital investment, the Manila correspondencia presented important differences, both in its contractual terms and the range of participants in the market for trade finance. These included the role of guarantors as surety, rather than the collateralization of goods, highlighting the importance of informal networks for the enforcement of contractual obligations, as well as the explicit way in which premia payable were specified in the contract. These differences, in turn, outline the specific commercial and social context in which correspondencias were used and evolved in contrast to the Atlantic trade.

This analysis of the Manila correspondencia is built on 540 extant contracts from the notarial protocols of Manila for the years between 1736 and 1800, all denominated in silver pesos. This includes correspondencias recorded in the protocols as issuances, cancellations, or guarantors’ titles (cartas de lasto). While this unprecedented wealth of data, allows for a systematic analysis of the instrument and its use, a robust estimation or quantitative analysis of the full universe of correspondencias is hampered by the fragmentary nature of the record, where only 33 notarial volumes survive. However, the chronological span of the hundreds of surviving documents provides important insight into the participants in the Manila capital market, which can be contrasted against other primary sources, such as the account books of institutional lenders like the Dominican Third Order.

This wealth of sources contextualizes the elements of the contract against the range of Manila’s trade operations and heterogeneous participants, as well as allowing us to reconstruct the premium rates throughout the eighteenth century. In turn, this allows us to identify periods of contraction and expansion in commerce, in order to reach a clearer understanding of the instrument in practice and the reason behind its popularity. In contrast to the collation of financial data, verifying and cross-referencing the personal identities of thousands of inconsistently named contractual parties remains an ongoing and ambitious prosopographic project, as does the reconstruction of borrowing coalitions and dynamic networks that extend over decades (likely generations). The volume years and specific contracts presented herein are thus selected as illustrative of trends that emerge from the fragmentary data. A more systematic case analysis is precluded by the lacunae in the Manila notarial archive, specifically the critical period between 1740 and 1770 (wherein only 8 years are extant).

This work argues that correspondencias were the foremost (and only) instrument to finance the Pacific trade and its intra-Asian legs, as they offered working capital on favorable terms to takers in a rationed commerce that kept profit margins artificially high and reduced market volatility. Crucially, it provided investors with a share of the profit while eliminating information asymmetries, and it incentivized a wide array of individuals and commercial interests from Europe and Asia to tap into Manila’s abundant silver supply to settle their own intra-Asian retail chains. The contract, therefore, represented a public order institution which enhanced agreements and monitoring within private networks, facilitating the pooling of resources and mitigating the principal-agent problem.Footnote 2 This was a locally differentiated solution to what Greif (Reference Greif2000) has called the Fundamental Problem of Exchange (POE) in pre-modern, long-distance trade, sustaining cooperation between a yet more heterogeneous, cross-cultural cast of economic agents than in the Spanish Atlantic: ranging from Spaniards (Iberian, American, and Asian-born), to South Fujianese junk merchants, Armenians, South Asians, and all manner of European interlopers (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007; Bhattacharya, Reference Bhattacharya2008; Gill, Reference Gill2011; Fang, Reference Fang2012; Baena Zapatero and Lamikiz, Reference Baena Zapatero and Lamikiz2014, Reference Baena Zapatero, Lamikiz and Sorroche Cuerva2024; Tremml-Werner, Reference Tremml-Werner2015, Reference Tremml-Werner2017)

This article explores the Manila correspondencia on three fronts. First, it analyses Manila’s evolution into a commercial and financial hub for the trans-Pacific and intra-Asian trades by the second half of the eighteenth century, linking the use of the instrument to the high liquidity of the city and relatively stable profit margins of its trade (Section 2). It then examines how the Manila instrument diverged from the Atlantic forms of the respondentia, with premia reflective of the potential returns for specific ventures, rather than a measure of individual or maritime risk, and argues that the correspondencia resembled more a type of partnership contract rather than a credit instrument (Section 3). This is followed by an examination of participation in the port’s capital market, a standout in this volume for its heterogeneity of actors from different cultural and social backgrounds (Section 4). In the context of cross-cultural exchange, non-Spanish residents who produced Spanish guarantors faced the same terms and premia as Spanish principals. Their participation in the city’s financial market and their capacity to integrate into Manila’s society evidence the allure of Manila’s liquidity for foreign traders, and their ability to fashion—through the correspondencia—private order arrangements capable of providing sufficient ex-ante guarantees to keep investment and trade flowing. A final section is reserved for conclusions.

2. Manila: commercial and financial hub of the Indo-Pacific

The conquest of Manila in 1571 and the development of direct trade between Asia and Spanish America, based on the shipment of large quantities of silver specie for Asian commodities and manufactures—primarily textiles—heralded the dawn of a truly global system of commerce (Flynn and Giráldez, Reference Flynn and Giráldez1995). While the volume of Spanish trade via the Philippines fluctuated during the route’s 250 years of operation, historians estimate that 2–4 million pesos (approx. 50–100 tons of silver) crossed the Pacific each year on average (Chuan, Reference Chuan, O’Flynn and Giráldez1997, p. 283; Ng, Reference Ng1983, p. 85; Bonialian, Reference Bonialian2012, pp. 45–48). This is roughly comparable to the estimated 160 tons of silver reaching Asia from Europe via the Cape of Good Hope each year between 1725 and 1800 (de Vries, Reference de Vries2010). But in terms of global players, Spain’s trans-Pacific exports were the largest of the Early Modern period, far surpassing the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which sent an annual average of 29 tons of silver from Europe to Asia between 1602 and 1795 (Gaastra, Reference Gaastra and Richards1983, p. 451), and the English East India Company’s (EIC) average of 40 annual tons between 1660 and 1820 (calculated from Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri1968, Reference Chaudhuri1978; Bowen, Reference Bowen2010).

The motivation behind these large movements of specie across the Pacific and within Asia was the profit margins that could be realized from arbitrage of the purchasing power differentials of silver specie between Asia, where it was scarcest, and Spanish America, where it was most abundant. In this regard, Manila’s commerce was but the most direct branch of a global Early Modern silver trade that involved different routes and various intermediaries across Europe, Africa, the Levant and the Indian Ocean, and that transported large volumes of silver specie from America to Asia, and especially China (Barrett, Reference Barrett and Tracy1990; Irigoin, Reference Irigoin, Battilossi, Cassis and Yago2020).

Estimates of profit margins are scant and often contradictory, as reflected in the literature. Bonialian (Reference Bonialian2012) references price differentials of 1,400% to 1,600% across the Pacific, resulting in net profits of 400–600%, although he provides no details of how these net profits are estimated. According to Gasch-Tomás (Reference Gasch-Tomás2015, p. 34), during the first half of the sixteenth century, profits fluctuated between 50% and 200% after discounting the premium of correspondencias, while Schurz (Reference Schurz1939) estimated a 200% return across the full period between 1571 and 1815. These estimates, however, refer to the Pacific crossing. Estimating similar information for the Asian leg of Manila’s trade is challenging (Ruiz-Stovel, Reference Ruiz-Stovel2019, pp. 110–112). Profits would have fluctuated across the centuries of the Manila silver trade, but the mere consistency of silver shipments annually and the continued demand for specie in Asia indicate that the profits to be realized from the Pacific silver trade were generous enough to beckon Manileños to risk their lives in the longest sea crossing in the world.

As with the English and Dutch East India Companies, Spain’s trans-Pacific trade was a royally sanctioned monopoly. However, rather than being granted to a single, consolidated, chartered company, monopoly privileges were awarded collectively to Manila’s Spanish official residents (vecinos), excluding the merchants of colonial Mexico and other parts of the empire. The formal institutions guiding the operation of a state-funded “galleon system,” as outlined in a succession of reglamentos, were not designed to facilitate or maximize the flow of goods and capital, but rather to ration subsidized cargo space (Alva Rodriguez, Reference Alva Rodriguez1997, pp. 80–84, Alonso Álvarez Reference Alonso Álvarez, Bernabeu Albert and Martinez Shaw2013, pp. 62–63). For most of the route’s history, lading space was publicly distributed by an ad hoc committee of residents (junta de repartimento) that assembled annually to issue lading certificates (boletas) (Schurz, Reference Schurz1939; Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007). While a secondary market for boletas was outlawed, in practice, less wealthy vecinos “ceded” their lading space to a concentrated group of galleon traders (Le Gentil, Reference Le Gentil and Fischer[1781] 1964, p. 156). The limit on outbound cargo from Manila (the permiso) was initially set at 250,000 pesos in 1593 and would progressively increase to 750,000 pesos by 1769. In turn, the inbound silver cargo from Acapulco was capped at twice the value of the permiso. In theory, these dual caps engineered a maximum profit rate and ration profits among the citizenry of Manila, but in practice, it only led to the underdeclaration of cargo. The nature and scope of this commercial regulation—especially in aspects pertaining to the Pacific silver trade—has been widely debated. For some, it represents an overarching imperial plan to structure commercial exchange (Yuste López Reference Yuste López2007; Bonialian, Reference Bonialian2012). Others have emphasized the lack of enforcement, and therefore the inconsequential impact of this abundant legislation (Schurz, Reference Schurz1939). The reality may have been more nuanced than either possibility, and a proper exploration of the topic would require a dedicated study, but the literature has not noticed the distinction between commercial and financial legislation with regard to the Spanish Philippines.

As a privilege of the citizenry of Manila, the Pacific trade was regulated through its own legal corpus embodied in the reglamentos, although the extent of enforcement of this legislation was not strict. Thus, commercial legislation, primarily referring to the American leg of Manila’s trade, was abundant and a never-ending source of litigation and diatribes, often arising from commercial disputes between cities.Footnote 3 In this context, the lack of top-down financial regulation and the absence of centralized institutions that could organize capital markets is striking. The literature has so far not addressed the contradiction between commercial overregulation (however ad hoc or unenforced) and the absence of formal financial institutional mechanisms. Our systematic analysis of the Manila notarial record and the accounting of legacy funds suggests that, in practice, the correspondencia filled this vacuum by offering a bottom-up framework through which merchants, organized as networks, could structure their investments.

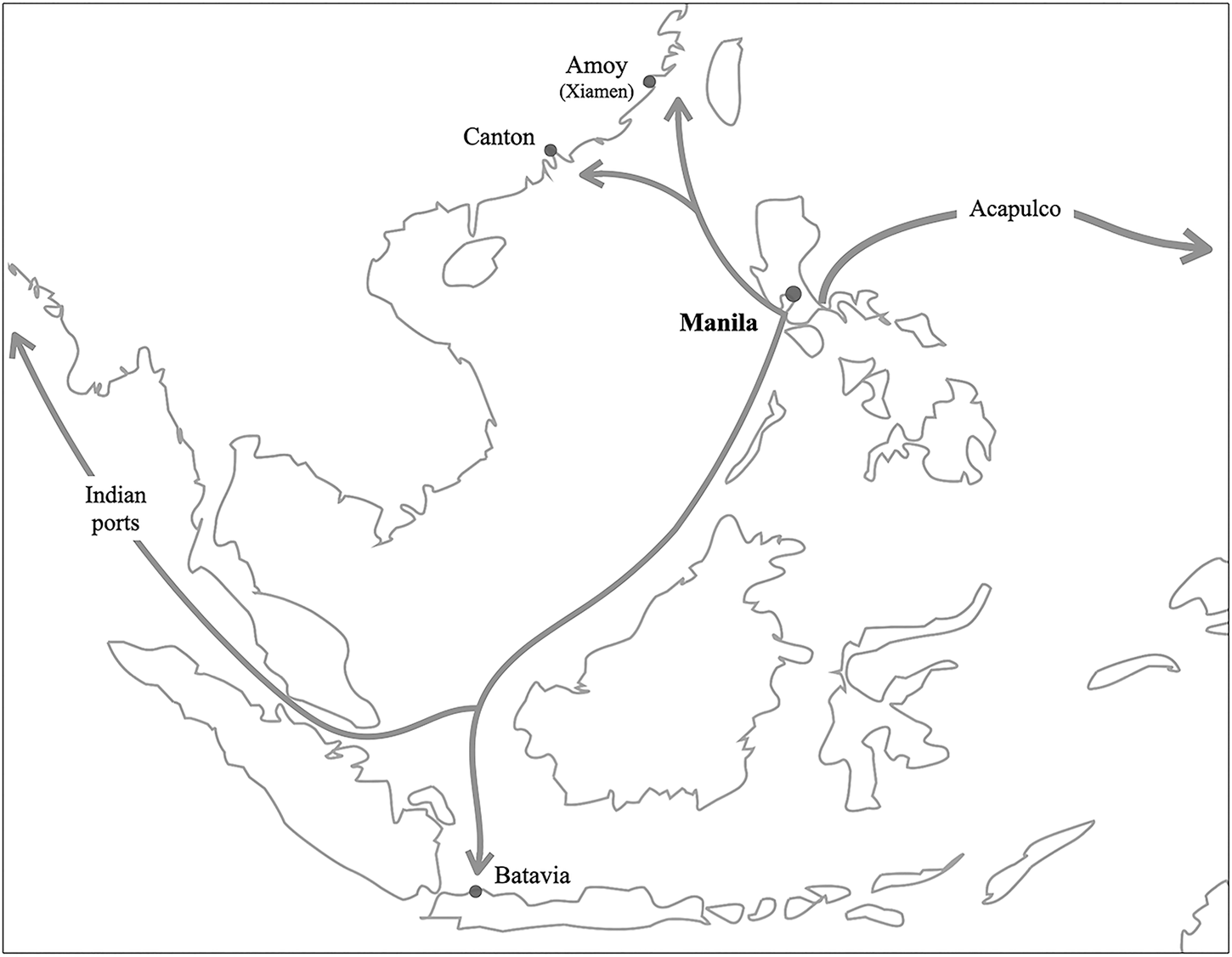

The trans-Pacific and intra-Asian routes of Manila’s Indo-Pacific trade circuit came to be fully integrated by the second half of the eighteenth century as a dynamic, long-term process. This integration was the product of both the spatial distribution and historical evolution of the competing and complementary commercial networks that connected Manila to other hubs in the Indian Ocean (map in Figure 1). The shipping network that radiated from China’s southern Fujian province to destinations across the South China Sea had a presence in Manila predating the arrival of the Spanish.Footnote 4 The network was thus primed to tap into this new trans-Pacific supply of silver to feed the mounting monetary demand of the expanding Chinese market (Von Glahn, Reference Von Glahn1996; Frank, Reference Frank1998).

Figure 1. Silver exports via Manila, ca. 1750.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Spanish Manila and Dutch Batavia were the major nodes in this sprawling Chinese network, with some 15 junks sailing annually from the South Fujianese entrepôt of Amoy (Xiamen) to each of these outposts in a typical trading season.Footnote 5 Also by mid-century, Manila Spaniards were funding an average of two voyages per year on the competing China route to Canton-Macao, a corridor previously plied primarily by Portuguese ships before the eighteenth century (Souza, Reference Souza2004). As relative latecomers, they were able to break into the Canton trade by partnering with a multi-ethnic cast of Manila-based foreigners on shipping, tapping the burgeoning Manila credit market to pay the Cantonese merchants in cash rather than on credit, as was done by the East India companies (Van Dyke, Reference Van Dyke2005). Manileño ships also ventured directly to Amoy, which was off-limits to European traders under the Canton System (1757–1842).Footnote 6 These China routes contrast with the long-haul, trans-Pacific voyage (as many as 5 months to Acapulco, 3 months return). On the other hand, the short-haul journey from Amoy to Manila could take as little as 2 weeks.

Manila was also connected to Dutch Batavia and European outposts in India. Unlike the connection with Amoy, shipping to Batavia was mainly in the hands of the same Spanish and foreign associates who plied the Canton route. This commerce with the VOC differed from the trade with India and China, as it supplied Manila with strategic goods, such as European iron for shipbuilding and saltpetre to produce gunpowder. Similarly, the VOC’s prized cinnamon monopoly relied on purchases for the Manila galleons (Flannery and Ruiz-Stovel, Reference Flannery and Ruiz-Stovel2020). Similarly, from the early eighteenth century on, a “regular country trade” on behalf of EIC agents connected the Coromandel coast and Bengal to Manila (Quiason, Reference Quiason1966), carried by Armenians, South Indians, and Catholic Europeans who often operated as figurehead captains and frontmen concealing investments from country traders and EIC employees. As the eighteenth century progressed, Indian cotton goods became an increasingly important part of the Galleons’ Acapulco-bound loads (Cosano Moyano, Reference Cosano Moyano1986, pp. 288–289).

Manila’s trade, in sum, was large, consistent, and profitable, and served to transfer voluminous quantities of silver specie to Asia. This trade, which involved merchants from multiple countries and diverse cultural backgrounds, required financing, and this was precisely Manila’s primary role as an intermediary between the Pacific and Asia. Manila functioned not only as a hub for the exchange of goods for silver, but also as a source of the working capital for the Pacific exchange—and partly for the intra-Asian trade. Since the beginning of the Pacific silver trade, correspondencias were used to finance the exchange. Initially, individuals financed the trade, while institutions like the Brotherhood of the Misericordia of Manila or the religious orders held investments in the land through censos, a debt instrument similar to English leases (see Ena Sanjuan, Reference Ena Sanjuán2021; von Wobeser, Reference von Wobeser1989, regarding the censo).Footnote 7 However, by the mid-seventeenth century, fund managers switched their investments from land to maritime commerce through legacy funds created for the purpose of originating correspondencias (de Uriarte, Reference de Uriarte1728; Mesquida, Reference Mesquida, Terpstra, Prosperi and Pastore2012; on the investment switch, see Mesquida, Reference Mesquida2018). The legacy funds, known as obras pías, were established with a donation of cash and a testamentary will that outlined how the cash was to be invested. The cash was left to the management of various institutions in Manila, including Misericordia, the lay orders and brotherhoods attached to the religious orders, hospitals, convents, the archbishopric of the city, and even the town council (AMN, 552). These funds were therefore under the direct administration of these institutions’ governing bodies, the so-called mesas (lit. “boards”), which were elected annually amongst the members of the brotherhoods.

According to the surviving records, the first correspondencia fund was opened in the Misericordia in 1668 (Díaz-Trechuelo, Reference Díaz-Trechuelo2001). It took some time for funds to take off, with only eight funds being established under the Misericordia between 1668 and 1700, but the first half of the century saw a boom in new funds founded across different managing institutions. Archival evidence reveals that 264 correspondencia funds under over two dozen institutions were active between 1668 and 1833, while suggesting that many more existed alongside these.Footnote 8 The four largest managers in Manila—the Misericordia, the Third Orders of Saint Francis and Saint Dominic (VOTs), and the Jesuit Order—accounted for the majority of funds, and they operated uninterrupted throughout the eighteenth century, with ever expanding portfolios. This continuous increase in capital made institutional investors the largest source of correspondencias in Manila. Because any individual could open legacy funds—as long as the foundational endowment was paid in cash—the principals of the funds varied widely. The Misericordia, for example, managed a handful of obras pías established with endowments of 50,000 pesos (AMN, 552). On the other hand, some of the funds based in the Third Order of Saint Dominic were relatively modest, such as the obra pía of Paula González, established in 1778 with an endowment of 300 pesos (APSR, Tomo 232). While there was a great variance, the endowment of most funds ranged between 1,000 to 8,000 pesos (see footnote 8 for sources).

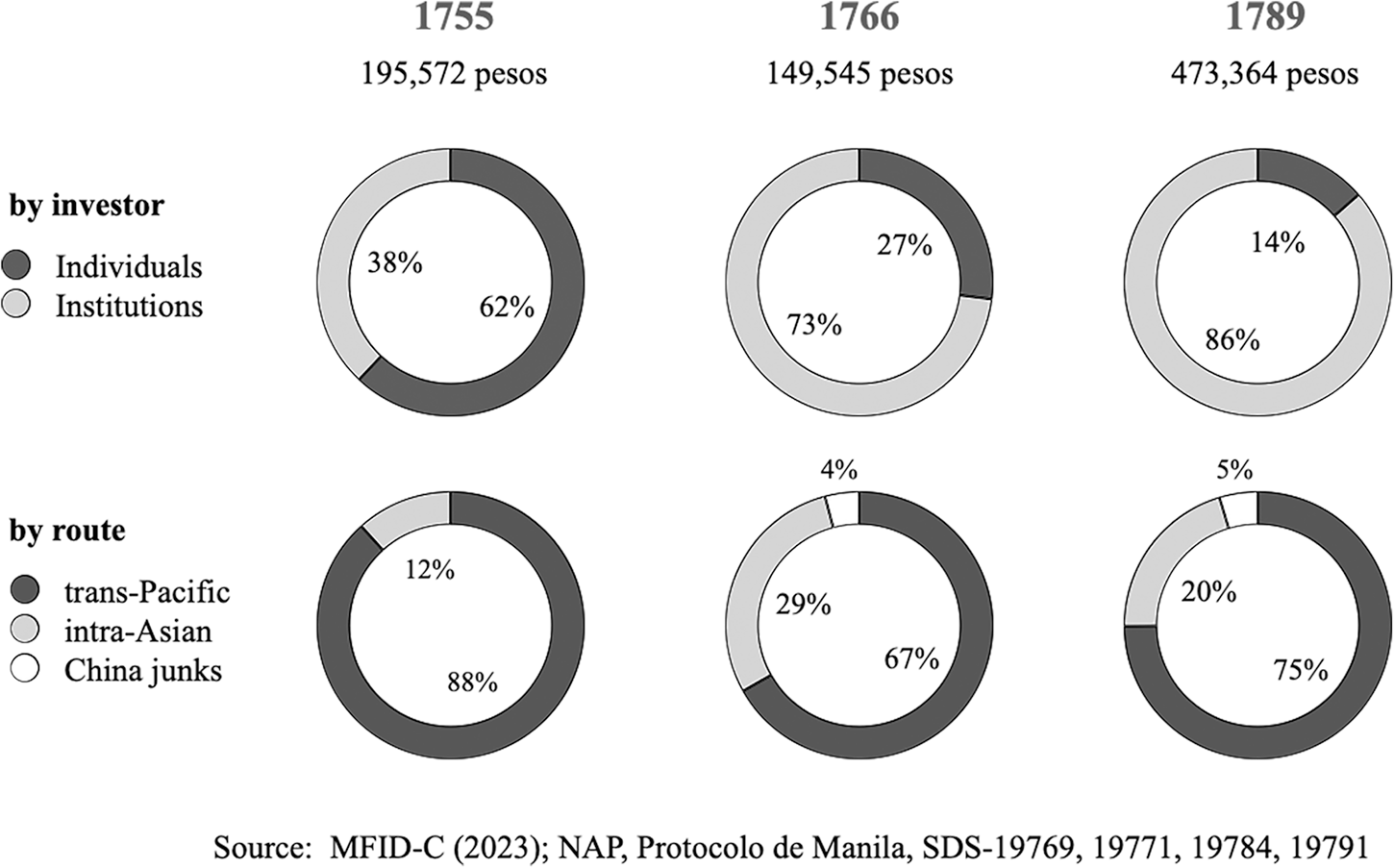

The series or graphs in Figure 2 show the distribution of pesos issued in correspondencias for the years of 1755, 1766, and 1789, according to the kind of investor and route. These years are chosen as a sampled reference due to the survival of a relatively large number of contracts (30, 50, and 89, respectively), arguably capturing a higher share of the universe of yearly contracts, evidencing trends that years with more meagre notarial volumes otherwise obscure or misrepresent. The evidence of a growing volume of pesos originated in correspondencias (indicated in the figure below each year) is in line with the decades of extant accounting records from major institutional investors, as is the growing share of institutional investment. This is the best possible measurement of the overall growth of institutional investors, given the state of the sources.

Figure 2. Extant notarial protocols: shares of total originated value, sample years. Source: MFID-C (2023); NAP, Protocolo de Manila, SDS-19769, 19771, 19784, 19791

The upper row represents the share of values in pesos issued each year by type of lender, whether they were institutional (referring to issuers standing in the contract as a corporate institution, mostly the obras pías of Manila) or private individuals. The lower row represents the destination of correspondencias, with capital divided between the Pacific trade (Acapulco) and the intra-Asian trade on European-style ships (to or from China, India, and even Southeast Asia). Existing contracts for Chinese junks from Fujian survive for only a handful of years, with implications discussed in Section 4. The sample illustrates how the increasing share of capital issuance by institutional investors contributed to a growing share of capital issuance in the city during the eighteenth century, with a particular expansion of trade and investment in its closing decades. This also reflects the continuous endowment of new obras pías under fund managers, and the persistent accumulation of returns over time, despite some eventual losses. While private investors never disappeared and some of them remained very important financiers, the obras pías progressively became the most important originators of working capital for trade.

The growth of obras pías and their investments dramatically increased liquidity in the market. This is visible in the holdings of the Misericordia, the largest manager of legacy funds in Manila. While in 1707, the Misericordia managed only 12 funds with assets worth 81,587 pesos (AGI, Filipinas, 193), by 1755, these had increased to 49 funds with 577,738 pesos; by 1783, the number had risen to 53 funds and 1,037,449 pesos (AGI, Filipinas, 595). The actual size of the capital market is difficult to ascertain with the fragmentary evidence available. However, Tomás de Comyn estimated that, in 1809, four years after the return of the last Galleon from Acapulco, the investment of legacy funds totaled 3 million pesos, while that of private individuals accounted for another 2.5 million, for a combined total of 5.5 million pesos, approximately 137 tons of silver (de Comyn, Reference de Comyn1810). The sheer volume of silver shipments, combined with the capacity of obras pías to direct individual savings toward trade and reinvest the proceeds, inevitably resulted in high liquidity.

Correspondencias long predated the obras pías and were the paramount instruments for trade finance virtually since the start of Spanish settlement. The emergence of these institutional investors, however, led to a symbiotic relationship with the correspondencia as an instrument that deserves analysis. The capacity of legacy funds as vehicles to pool savings and originate working capital augmented the long-run liquidity that characterized the Pacific silver trade and that enhanced the role of correspondencias as instruments that relied on the exchange of cash. On the other hand, correspondencias—as explored in the next section—facilitated the involvement of obras pías thanks to their flexibility, which allowed investors and merchants to apportion risks and returns while capturing a measure of the profits of the trade.

3. The Manila correspondencia: elements and practice

The investment generated through correspondencias was ultimately buttressed by the notary public. The Hispanic world had developed a highly notarial culture that facilitated contracting amongst individuals (Cortes Alonso, Reference Cortes Alonso1984; Álvarez-Coca González, Reference Álvarez-Coca González1987) and allowed for information to be accessible to parties and authorities. All contracts had to be recorded in notarial deeds accessible through the archive of the notary public, and stamped by his office, as was the case in the Atlantic (Bernal, Reference Bernal1992). This provided correspondencias with legal status and created a bottom-up framework through which investments in the trade could be structured. There was no institution akin to the Seville Casa de la Contratación operating in Manila—until the belated creation of the local Consulado in 1769. But the office of the notary guaranteed an institutional scaffolding that granted legal formality to informal networks and partnerships. By the 1740s, which marks the beginning of the extant notarial record, the Manila iteration of the correspondencia had evolved into a standardized contract with a boiler-plate text. Some elements had precedents in their Mediterranean and Atlantic use, while others were institutional adaptations to the structure of trade in the Pacific and maritime Asia. This section reviews the formal elements of the contract in contrast with the Atlantic préstamo marítimo and the mechanisms by which the correspondencia was used to channel silver flows across the Pacific and Asian waters. In contrast to the Atlantic iteration of the correspondencia, which functioned as a credit instrument (Herrero Gil, Reference Herrero Gil2005; Lamikiz, Reference Lamikiz2022), the Manila correspondencia performed akin to a partnership contract or an advanced-sales contract, as Manila residents, Juan de Paz and Pedro Murillo Velarde argued contemporaneously in their legal observations (Paz, Reference de Paz[1687] 1745: 1745, BNE, Porcones 972, 1747). It was this mechanism that contributed to the mobilization of working capital and solved information asymmetries between contracting parties.

Issuing a correspondencia involved a main principal (otorgante, in the notarial deeds) and his co-principals (identified as guarantors or fiadores) requesting investment for a certain amount of money from an investor, either an individual or a fund manager. There are no surviving records of how the contracts were negotiated between individuals, but when it involved institutional investors, the procedure was for the principal and guarantors to apply for a certain amount of money to be invested in a specific destination to the mesa, which then decided whether to issue the correspondencia or not at the amount to be invested. A positive decision would then be recorded in the Minutes book of the board and would create a corresponding actuarial entry in the account books of the funds (MFID-C, 2023 in dataset list; see APSR section in source list). The contract was originated through a notarized public deed (escritura) and the exchange of physical cash. Therefore, correspondencias were authenticated by a notary (escribano público) authorized by the highest court of the land and signed before three additional witnesses, as well as an official translator of Tagalog or Chinese when needed.

In terms of the formal element of the contract, Manila correspondencias were very similar to the Spanish préstamos marítimos, as described by Bernal (Reference Bernal1992) and Ravina Martín (Reference Ravina Martín1980), but the evolution of key variations brought these instruments more in line with partnership contracts with guarantees for investors, rather than other credit instruments. These differences appear principally in the terms and conditions of repayment and the premium. Unlike in the Atlantic version of the contract, where the rate of return was implied or omitted, Manila correspondencias explicitly set premia in percentage points within the text of the contract, representing the expected returns to capital (Irigoin, Reference Irigoin2022). Concerning the terms of repayment, correspondencias do not appear to have required collateral to guarantee the transaction, nor was any penalty or interest incurred for late repayment, unlike the case with Atlantic préstamos marítimos. The contract’s lack of formal time elements, other than the usual duration of voyages necessary for trade (such as penalties for arrears and interest for payment delays), suggests that the opportunity cost of money—the fundamental factor in pricing a credit asset—did not determine the premium of correspondencias in Manila.

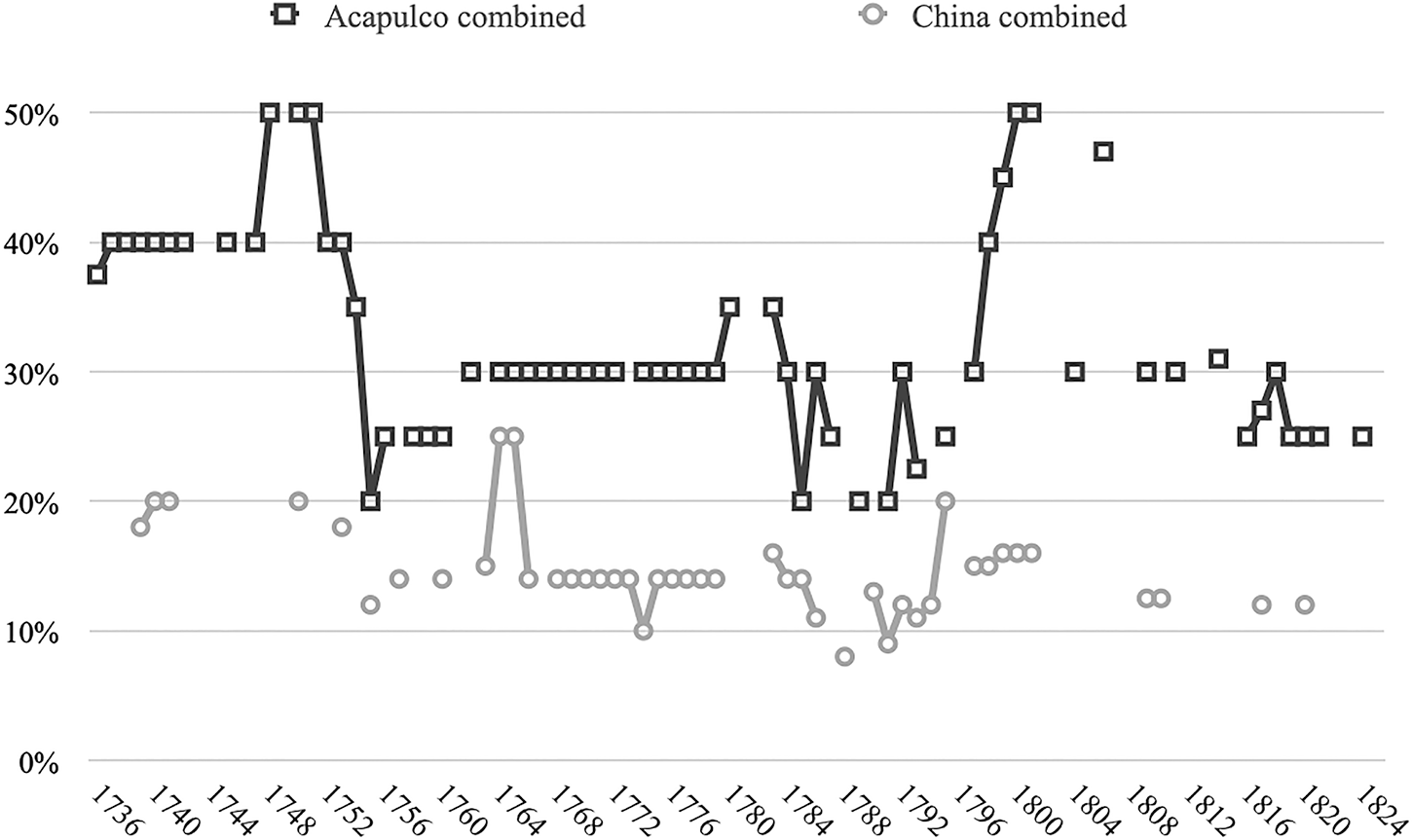

The premia of correspondencias fluctuated in response to the influx of silver specie into the city. Figure 3 plots the evolution of premia to Acapulco between 1725 and 1825. The graph reveals two important trends. The first was that, for a given year and destination, premia barely diverged between issuers. The mesas of each institutional investor met independently to individually set the destination rates for their own funds, but in reality, institutional and individual investors simply pegged their rates to those published by the largest fund managers: the Misericordia and the VOT of Saint Francis. Only after 1779, do we see a divergence in the annual spread of rates for a same destination, though this variation was never substantial. Pegging premia to the Misericordia rate remained the standard.Footnote 9 The second trend illustrated by the graph was the long-term decline in premia across destinations. For the Pacific, the rate went from 50% at the beginning of the century to 25% by 1825. Yet it had troughs as low as 20%, and the median for the whole period was only 30%. Premia for Asia also had a declining trend, but it was less pronounced. When we compare these rates to the enormous profit margins proposed by the literature (200–400%, as discussed in Section 2), correspondencias clearly offered a relatively cheap way of financing commercial enterprises that had a very high yield potential.

Figure 3. Premia of correspondencias issued in Manila, by route.

This secular decline in premia across destinations can be explained by focusing on how investors actually set these rates, a calculus which we argue differs from traditional explanations. The usual interpretation in the literature on the Spanish Pacific is that the correspondencia was a credit cum insurance instrument, according to which the premium and principal only had to be repaid upon the successful completion of a trip, allowing creditors to charge higher interest rates (Gasch-Tomás, Reference Gasch-Tomás2015; Yuste López Reference Yuste López2015). According to this interpretation, the premium rate would rise in response to an increased risk of loss, such as the outbreak of war. Yet the premium of Manila correspondencias was not substantially correlated with periods of warfare. For example, the premium for Acapulco during the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–1747) remained at the pre-war level of 40%, before jumping to 50% in 1748 with the advent of peace.Footnote 10 Similarly, after the peace of Amiens in 1801, rates in Manila were at 50%, yet in 1804, once war resumed, rates had paradoxically fallen to 30%. More strikingly, in the aftermath of the Occupation of Manila (1762–1764), premium rates only increased from 25% in 1760 to 30%, despite depletion of the capital stock by English looting of the obras pías. Premia did not respond to the newfound peace in the aftermath of the Seven Years War, remaining stationary at 30% for the rest of the decade. If premia did not respond to war and peace, which affected the chances of loss at sea in the hands of privateers, the proposition that rates largely embodied an insurance element becomes less tenable.

This article contends that correspondencias were a type of partnership—since the fixed payable premium, as a percentage of the principal, disqualifies the instrument as a kind of equity contract—in which the premium represented a share of the expected profit margins of the venture that the contract financed. This conceptualization of the correspondencia is in line with the characterization of the instrument by contemporary legal experts such as Juan de Paz (1687:1745, pp. 99–100) and Pedro Murillo Velarde (BNE Porcones 972, 1747) as type of company contract, and is supported by the difference between the rates of correspondencias for Asian destinations and those across the Pacific, which often were double the amount, presumably representing differences in costs and profits. In such a case, the decline would represent a long-term decline of the profits from arbitrage of silver specie across the Pacific, the leading enterprise of Manila. This cannot be corroborated with certainty, but the scarce evidence available for the latter half of the eighteenth century suggests that profit margins were still far wider than the decline between premium rates across the century (Cheong, Reference Cheong1971 presents data evidencing that markups across the Pacific remained in the range of 100–300% across the Pacific by the 1790s). The trend could also be explained, as Yuste López (Reference Yuste López2007) argued, by the eventual liberalization of trade in Manila and in Mexico during the final quarter of the eighteenth century, leading to an increased volume of transactions. However, the secular decline started in the 1740s, long before the opening of Manila’s harbor in 1789 or the chartering of the Real Compañía de Filipinas in 1785. Similarly, it is dubious that existing legislation really prevented trade in the harbor of Manila. The work of Quiason (Reference Quiason1966) has been instrumental in revealing how banned parties used subterfuge to trade in the Philippines; therefore, it is difficult to determine in what ways the Manila trade changed before and after the official opening of the harbor in 1789.

Another explanation is that this decline represented changes in the supply of capital, that is, excessive demand that was not met by an equal expansion of investment options. This is a far more likely explanation, given the boom in new correspondencia funds established between 1710 and 1740, coinciding with the decline of premium rates and the steady pace of new creations, which resumed again between 1780 and 1790, concurrent with further drops in the premia to Acapulco. It also explains why the drop in the Pacific trade, confined to one Galleon for reasons related to the market structure of the silver trade in Acapulco (Rivas Moreno, Reference Rivas Moreno2024), was much more pronounced than that for intra-Asian destinations, which always involved a larger number of vessels in which to invest. It also explains some of the peaks and troughs of the series, like the fall of premia to Acapulco from 40% in 1753 to 20% in 1755, after Governor Ovando halved the cargo space available in the Galleons for 1754 and 1755, essentially reducing demand for capital (AGI, Filipinas, 268). The evolution of correspondencia’s premia suggests that their rates represented a negotiation between the potential returns of the enterprises they financed and the price of capital in Manila.

Unlike credit contracts, Pacific correspondencias had no specified term of maturity. Instead, they were to be repaid upon the successful return of the vessel in which the investment travelled—that is, upon completion of the financed venture—within a period of 15 days. Thus, the contract did not have a timed duration other than the usual length of the commercial voyage, which varied according to destination as shown in Section 2. When the spillover of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1792 forced the Galleon in Acapulco to delay its return to Manila, correspondencias issued that year were not repaid until 1795, without accruing penalties or accumulating interest (NAP, SDS-19789). The premia of correspondencias certainly created an obligation on the part of the taker to repay principal and premium to the investor, and this obligation was legally binding. When takers of correspondencias absconded of this commitment, guarantors could be asked to repay, and in some cases, litigation was brought to the courts, but only a few cases of this have survived. According to the account books of the VOT of Saint Dominic, most cases of non-performing contracts resulted in a write-off and formal exclusion from the capital of the obras pías for the defaulters (MFID-C, 2023 in dataset list; APSR section in source lis).

The fact that the premium was established as a percentage of the principal and was repayable upon completion of the venture meant that correspondencias were not equity contracts, in which both investors and merchants share equally in profits and losses. Two key points to consider are that establishing the premium as a percentage of the principal, rather than a share of net profits, was a sensible choice in long-distance trade finance contracts, where the investor remained on land, while the merchant travelled across vast distances. This separation resulted in an asymmetry of information, since only the travelling partner truly knew the prices for which the goods had sold at destination (Börner, Reference Börner2007), and thus, could choose to withhold this information. Percentual premia simply did away with this kind of asymmetry without the need for expensive monitoring arrangements. The second factor is that the absence of a specified maturity and the obligation to repay principal and premium after the successful winding up of the commercial venture, coupled with the premia representing a calculation of the expected returns and the price of capital in the city, signal that correspondencias functioned more as an instrument for venture capital than a credit or equity instrument. This is especially evident when considering the differences in the use of the instrument between the Pacific and Asian legs of the Manila trade. In both cases, the instrument provided financing in the form of silver pesos, but in the junk trade with China, this entailed shipping the specie to Asia for purchases of goods which were then discounted from the correspondencia at the time of repayment, working more akin to an advanced sales contract embedded within a venture capital transaction (Ruiz-Stovel, Reference Ruiz-Stovel2019, p. 98).Footnote 11

The formal element of the contract suggests that the correspondencia functioned more as a partnership that mobilized savings from individuals and funds and transformed it into working capital for trade. This is apparent in the changes in the premium rates by destination. The proliferation of obras pías that issued correspondencias led to a situation in which the supply of capital expanded faster than its demand, resulting in a declining trend of premia, which made correspondencias cheap for takers. Its elements, similarly, reduced information asymmetries between financiers and merchants, and were flexible enough to function as both an advanced sales contract and working capital for intra-Asian trade. In short, the correspondencia was an ideal instrument for Manila’s silver trade, offering returns and guarantees to investors while remaining cheap for takers and facilitating the flows of specie from America to Asia.

4. The Manila credit market: diversity of actors and cross-cultural trade

The capital market of Manila was seemingly open to individuals of all classes who came either to invest or to raise capital for trade ventures, either as principals or guarantors of someone else. The section shows how the figure of the guarantor in the correspondencia facilitated contracting as a kind of co-principal, often working as an intermediary between a non-Spanish merchant seeking capital and a Manila-based investor. This complemented the guarantees offered to investors and the cheap price of capital in Manila discussed in Section 3 to make Manila an attractive market in which foreigners could contract for operational capital and occasional outsiders could invest. This qualifies the literature on the Fundamental Problem of Exchange: Manila’s liquidity was key in attracting merchants to tap into the city’s financial market, while the correspondencia played a crucial role in diminishing the uncertainties of the exchange and offering enough ex-ante guarantees to all parties involved. The discussion in this section focuses on these qualities, which help to understand the extension and persistence of its use.

As the Asian terminal of the Pacific silver trade, Manila always had a very heterogeneous population. By 1778, Manila’s fortified core (Intramuros) had reached a population of 6,345 inhabitants. Of its 1,637 Spanish residents, 91% were Philippine-born, with the remainder from Iberia (6%) and New Spain (3%) (AMN, 384). Among these Spaniards, only 40–60 established male merchants, along with the occasional wealthy widow (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007, p. 87), would have participated directly as registrants in the annual trans-Pacific galleon.Footnote 12 The population of Manila’s suburban villages (Extramuros) outnumbered the Spanish walled town, with several thousand residents comprised mainly of indigenous tagalog speakers (indios), Chinese settlers (sangleyes), and their mixed-race descendants (mestizos de sangley). During the trading season between April and August, Extramuros also absorbed a floating population, predominantly of Asians and some Europeans, from across the Indian Ocean. Between 1737 and 1756, the period for which we have a reliable series of data, approximately 1,600 merchants and crewmen sojourned in Manila each year on average, of which 80% were South Fujianese associated with the junk trade (MIAT, 2021; AGI, Escribanía, 431A, 434A, 436D).Footnote 13

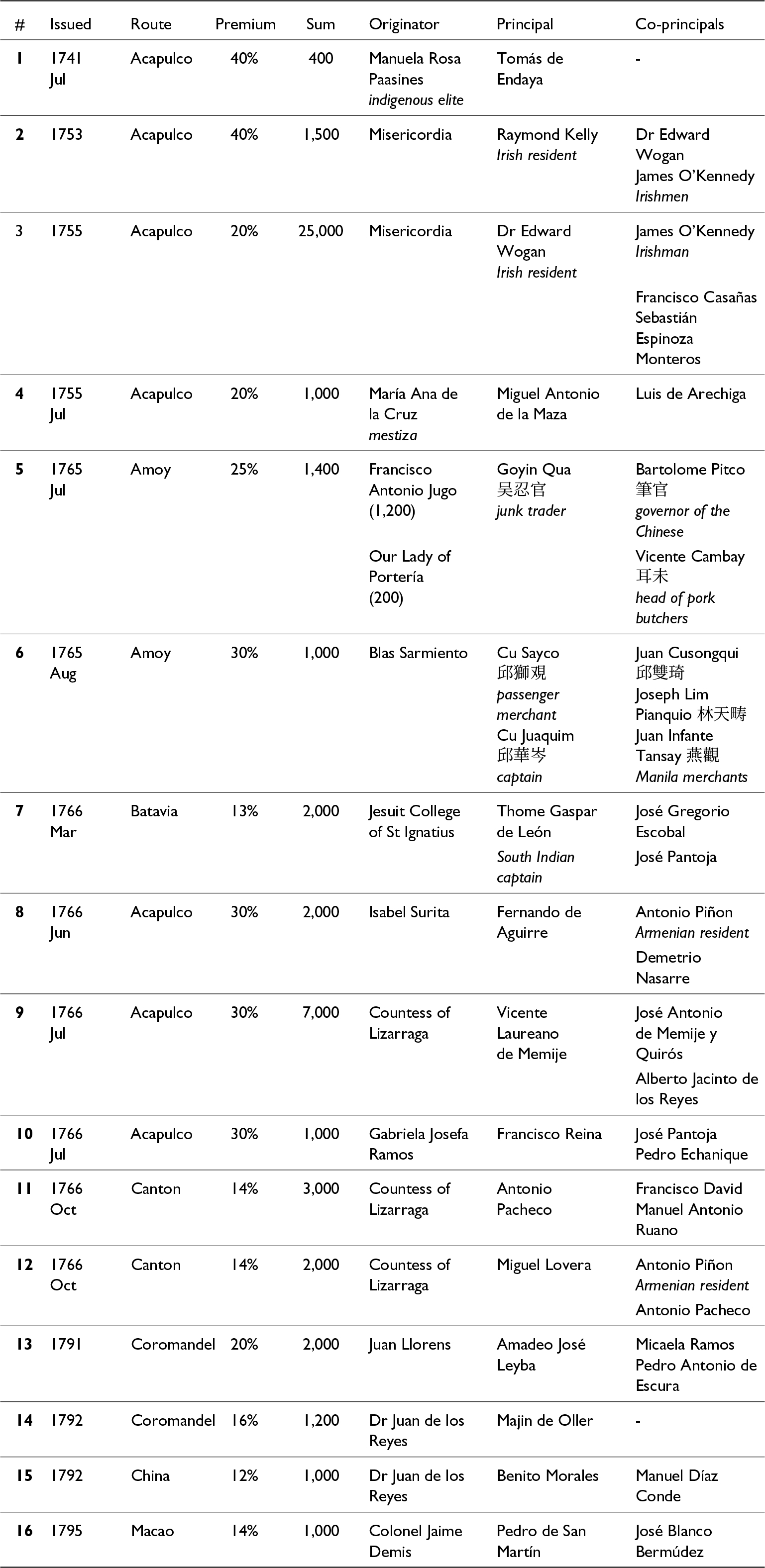

Joseph Lim Pianquio 林天畴

Regarding the social status of participants in Manila’s correspondencia market, variety was equally broad. Some of the wealthy Spanish merchants who imported and exported goods as registrants on the galleon, such as members of the Bermúdez and, Memije merchant dynasties, appear in the notarial record as bsoth beneficiaries and suppliers of correspondencias (see Contracts 9 and 16 in Table 1).Footnote 14 But other wealthy Spanish residents instead set themselves up as individual financiers, providing capital to veteran traders. This was the case of the countess of Lizárraga. In 1766 alone, originated 16,000 pesos (432 kg of silver) in four correspondencias to some of the most influential merchants of Manila, including Francisco David and Vicente Laureano de Memije (Contracts 9–12). Occasional investors also included professionals, such as military officers or doctors. Example contracts show artillery colonel Jaime Demis investing in the Macao route in 1795 (Contract 16, 1000p), while Dr Juan de los Reyes, a surgeon in Manila’s Royal Hospital, invested in both the China and India routes in 1792 (Contracts 14–15, 2200p combined). Women were also relatively common amongst these occasional participants. The table includes correspondencias for Acapulco issued to established galleon merchants by 2 Spanish women in 1766: Isabel Surita (Contract 8, 2000p) and Gabriela Josefa Ramos (Contract 10, 1000p). Such sums paled in comparison to the investments made in that same year by the Countess of Lizarraga as a female financier. Women, however, seem to be absent as beneficiaries of these contracts. The role of Micaela Ramos as a co-principal in a correspondencia to Coromandel in 1791 is a rare exception (Contract 13, 2000p). These participants were outsiders to the trade of Manila, occasional involvement in the capital market suggests that they did so to complement their property but not on a regular basis. The fact that they could issue correspondencias illustrates the availability of liquidity in the city and the ease with which outsiders could invest.

Table 1. Actor heterogeneity in the capital market: select contracts

Note: Non-Spanish actors labeled in italics.

Source: MFID-C (2023); NAP, Protocolo de Manila; AGI, Contaduría, 1282.

De jure, ethnicity was a barrier to participation in the direct trade with America because the non-Spanish residents of Manila were barred from becoming registrants on the galleon. An exception is the case of Antonio Tuason (a wealthy mestizo de sangley), who was rewarded for his military service with lading privileges on the galleon beginning in 1784 (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007, p. 223). Equally interesting is the case of María Rosa Paasines, a member of the indigenous elite (principalía) of the Manila suburb of Ermita, who in 1741 received 400 pesos from the wealthy galleon merchant Tomás de Endaya without requiring a guarantor (Contract 1). Undoubtedly, María Rosa would not have registered these 400 pesos in her own name in the Galleon, and most likely relied on a consignor to act on her behalf, but this case represents proof that legal boundaries could occasionally be crossed. These barriers did not preclude financing the American trade. Among the occasional investors, we find Philippine-born actors (indigenous and mestizo), who happened to not only be non-Spanish, but also women. In 1755, a mestiza de sangley by the name of María Ana de la Cruz originated a correspondencia to the treasurer of that year’s Acapulco galleon, Miguel Antonio de la Maza, (Contract 4, 1000p), a seasoned trader. The allure of trade profits and the cheapness of contracting and issuing correspondencias attracted many participants to the capital markets, regardless of the rules, which proved to be permeable.

Foreigners mostly appear as takers of correspondencias, coming to Manila to receive capital. This included the shipping network of Manila Spaniards and non-Chinese foreigners (mostly Armenians and Europeans) that came to dominate the routes to Canton-Macao and Batavia by the mid-eighteenth century (Flannery, Reference Flannery2021; Tremml-Werner, Reference Tremml-Werner2017). The central figure of this shipping network, the Lusophone South Indian Christian Thomé Gaspar de León (Flannery and Ruiz-Stovel, Reference Flannery and Ruiz-Stovel2020), appears in the notarial record with a correspondencia originated by the Jesuit College of St Ignatius for a voyage to Batavia aboard his ship, the Espíritu Santo, in 1766 (Contract 7, 2000p). The requisite mercantile trust behind this transaction had been cultivated by De León through two decades of Manila-based trading and services to the crown, allowing him to produce two Spanish galleon merchants as co-principals and gain approval from the fund manager (a member of Manila’s Bermúdez merchant dynasty). Two other members of this multi-ethnic shipping network, the Italian Placido Pigolotte and the Irishman Richard Bagg appear in correspondencia cancellations from 1752 and 1755, respectively, also in exclusive association with Spanish guarantors.

Foreign residents appear only exceptionally as fiadores, even on behalf of Spanish principals. This was the case of the long-term Armenian resident known by the Spanish name Antonio Piñón. While Piñon does not appear in the record as either issuer or principal, between 1765 and 1766, he went on to co-sign six contracts worth over 24,000 pesos as guarantor to Spanish principals (for both Acapulco and China). These include the previously discussed correspondencias originated by the Countess of Lizarraga and Ms Surita (Contracts 8 and 12), all of which were jointly signed by additional Spanish fiadores. In fact, Piñón blended so successfully into Manila’s Spanish merchant community, that he has been glossed over by the literature as just another Spanish galleon trader, even serving as master of silver on the galleon to Acapulco in 1766 (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007, pp. 352, 446). Manila had a small yet important Armenian merchant presence (Bhattacharya, Reference Bhattacharya2008; Baena Zapatero and Lamikiz, Reference Baena Zapatero and Lamikiz2014, Reference Baena Zapatero, Lamikiz and Sorroche Cuerva2024), and depositions from Manila’s Armenian community in 1779 confirm that Piñón was in fact its leader (AHN, Consejos, 21017, P7). However, there are unfortunately no trace of contracts demonstrating how Piñon may have deployed his position as a cross-cultural broker (Curtin, Reference Curtin1984) to facilitate access to Manila’s capital market for fellow Armenian residents or seasonal traders. Other foreign networks also came to Manila to finance their commercial ventures. An example is the Manila-based Irish physician Dr Edward Wogan, acted as a guarantor in a correspondencia for 1,500 pesos for an Irish principal in 1753, and he himself received 25,000 pesos from the Misericordia in 1754. As European Catholics, the Irish not only had access to Manila markets but to commercial circuits throughout the Spanish Empire that were closed to other foreigners, which they often did as brokers (or figureheads) for the English. Both Piñon and Wogan could use their position within Manila and the figure of the guarantor in correspondencias to ease the flow of capital.

These cases reveal a sizeable cross-cultural cooperation within the Manila capital market that was not defined by a static binary between absolute trust and distrust as described by Greif (Reference Greif2000). It suggests that mercantile trust was both relative and could be built over time. This is more evident in the contracts to Chinese seasonal traders, which make up about 10% of the total correspondencia dataset (55 contracts) but are spread unevenly across the extant record: with the largest cluster of contracts in 1765–66 (29), followed by 1740–41 (17), and an additional 9 contracts scattered between 1783 and 1795. Across the board, South Fujianese principals paid twice the premium (25–30%) as Spaniards active on the China route in the same year, a rate comparable to correspondencias for Acapulco. Yet, unlike other non-Spanish foreigners, Chinese shipmasters and passenger-merchants (huoke 貨客) were not long-term Manila residents, and none produced a Spanish fiador. In these contracts, we see a break with standard practice, where the Fujian-based principals usually come in pairs (rather than the single principal in other contracts) and produced as many as six co-principals, all of whom were Manila-based Christian Chinese. This was the cross-cultural broker class that Manila’s Spanish establishment trusted, and that grew especially powerful as local agents for the junk trade between 1755–1769, when non-Christian Chinese were banned from remaining in Manila outside of the trade season. The 1760s contracts further suggest that having a co-principal from this class with a track record in the Spanish-sanctioned governance of the city’s Chinese Quarter was certainly encouraged, perhaps even required.

No evidence survives that the obras pías invested directly in the junk trade with China. In fact, there are only four extant contracts involving a Chinese institutional investor. In each of these, a Spanish merchant appears as the primary investor, with a legacy fund serving as a secondary investor, contributing a few hundred pesos. Three of these unusual mixed investments originated in 1765 by Juan Antonio Jugo, who, in the example provided (Contract 5), advanced 1,400 pesos at 25% premium to a junk captain, with none other than the current head of the Manila Chinese community as one of two guarantors. This created an opportunity for individuals more familiar with the junk trade, who were likely less averse to the risks and costs of monitoring Chinese beneficiaries. The prime example was Blas Sarmiento, a former galleon trader and career official. Of the 55 extant Chinese correspondencias, 17 were issued by Sarmiento, totalling an investment of 27,200 pesos with an average premium of 30%. Within the same 1765–66 notarial sample, Sarmiento charged this same premium in a 500-peso correspondencia to Spanish merchants for Acapulco, but only 15% for a 3000-peso correspondencia for Spaniards headed to Macao. This brings the total capital originated by Sarmiento to 28,200 pesos across 19 contracts. The combination of small-scale investments in the junk trade made Sarmiento the most prolific issuer in the surviving record for 1765–66.

Given the survival bias of the notarial record, the extent to which Chinese junk traders relied on Spanish financing through correspondencias remains an open question. Chinese language sources on the South Fujianese junk trade, which are even more fragmentary, neither confirm the use of Spanish correspondencias, nor do they provide systematic data on alternative forms of financing on the China side. That a financial infrastructure analogous to that of the Canton hang (Van Dyke, Reference Van Dyke2005, Reference Van Dyke2011) existed in Amoy to finance its extensive junk trade with Southeast Asia, coastal China and Taiwan appears self-evident, but the actual function served by the port’s licensed “oceangoing” and “commercial firms” (yanghang 洋行 and shanghang 商行), outside of customs collection, remains unclear (Zhou, Reference Zhou1839, j.5; Chen, Reference Chen2006, p. 369; Ruiz-Stovel, Reference Ruiz-Stovel2019, pp. 201–255). Additional sources of Chinese investment, such as corporate lineages in Fujianese home villages or the wealthy among Chinese residents of Manila, must also be considered as part of the portfolio of financing options for traders on the Manila route.

Regardless of how central or marginal Manila’s capital provision may have been for the Fujianese trade network, the question that connects all foreigners to Manila is why they would come to the city not only to sell their goods for silver, but also to acquire working capital. The different cases of foreigners coming to Manila and contracting either as settled residents or through the intermediation of established intermediaries acting as guarantors suggest two main takeaways. Firstly, the correspondencia offered the elements to provide enough ex-ante guarantees to investors through the figure of the guarantor, which could act as a cross-cultural broker (Trivellato, Reference Trivellato, Bentley, Subrahmanyam and Wiesner-Hanks2015). Secondly, the capital market in Manila was open to foreign merchants, allowing them to access capital with relative ease.

Manila’s position as the Asian terminus of the Pacific silver trade would have made it an enticing location to acquire specie, not only as revenues for sales, but also as capital investment or advanced sales. The evidence suggests that foreigners could indeed participate in the capital market if they cultivated the local social connections to secure the requisite guarantors. The participation of merchants from both sides of the Indo-Pacific trade illustrates that Manila offered favorable conditions for financing operations, reinforcing the idea that high liquidity made the terms of contracting for correspondencias attractive to traders seeking working capital, as argued in Sections 2 and 3. Conversely, Manileños did not tap other Asian capital markets to finance their operations, further evidence that conditions were better in Manila than in neighboring ports. On the other hand, the full scale of clandestine investment by Mexican merchants in the Maniila trade via silver shipments outside the permiso has been a point of deserved speculation (Yuste López, Reference Yuste López2007), but remains difficult to quantify with the available sources to study in parallel to the correspondencia market fully.

Openness to trade and high liquidity were related. In principle, a financial market afflicted by a lack of suitable options to place all its investable capital would have in theory been in no position to reject new applicants, as suggested by correspondencias issued by local occasional investors outside the merchant class, such as women and professionals. That widows and doctors could finance commercial ventures to complement their incomes is indicative of the low barriers of entry for outsiders to the trade, which in turn augmented capital supply. Similarly, the surviving contracts issued to foreign merchants, although relatively limited and dependent on Manila residents as co-principals and cross-cultural brokers, also extended the liquidity and openness inherent in the Manila capital market.

5. Conclusion

Like the respondentias of the Spanish Atlantic, the Pacific correspondencia evolved from the same type of sea loan contract dating back to Greco-Roman Antiquity, but in responding to the specific incentives and constraints of the trans-Pacific silver trade with Asia, it diverged from its Atlantic counterpart, while retaining many of its core characteristics. In the absence of a unified institutional structure to organize intercontinental financial exchanges via Manila, correspondencias evolved to fill this vacuum and provided a contractual framework allowing networks of merchants to mobilize vast quantities of traded silver across the Pacific and maritime Asia. Correspondencias were a securitized partnership where fixed returns—the premia—were calculated and agreed upon as a percentage of the initial investment based on the estimated profit margins on a given route. The arrangement mitigated information asymmetries between investors and the operating merchants, offering guarantees to investors while enabling them to partake in the profits of commercial ventures. The proliferation of the obras pías as institutional investors and the consequent expansion of liquidity in the city reached its zenith by the last decades of the eighteenth century, with a resulting long-term decline in the premia of correspondencias, spurring growing investments at increasingly cheaper rates. Silver flowed not only as proceeds of the trade, but also as working capital destined to finance commercial operations in a continent characterized by its demand for hard cash to settle transactions.

The literature on Spanish colonial trade has placed much attention on the progressive abandonment of sea loans during the last decades of the eighteenth century (Baskes, Reference Baskes2013). In contrast, Manila’s correspondencias surged during the 1780s and 1790s. Over 80% of the surviving contracts in the Manila notarial record belong to this era, which is consistent with the concurrent expansion of the capital holdings of the Misericordia, the main institutional investor (reviewed in Section 2). Correspondencias remained for as long as the Pacific silver trade lasted. In fact, the use of correspondencia contracts in the Spanish Philippines persisted until 1838, when the Misericordia petitioned the authorities to change its charter and become a modern maritime insurance company (AMN, 700). This link suggests that the value of the instrument went beyond its characteristics as an investment contract and was linked to the macroeconomic environment in which it existed. Crucially, as Irigoin (Reference Irigoin2022) has argued for respondentias across maritime Asia, respondentia contracts established shared legal obligations between parties and apportioned risks between takers and issuers. This enabled individuals from multiple geographic and cultural backgrounds to stake claims over the proceeds of long-distance trade in terms that were time-invariant, facilitating the flows of silver. While an abundance of silver incentivized a diverse array of actors to contract in Manila, it was the correspondencia that offered a bottom-up, private-order mechanism to tackle the Fundamental Problem of Exchange.

Acknowledgements

We thank the organizers and members of the panel “The Great Intermediation” in the XIX World Economic History Congress in Paris which served as the basis for this article. We would further like to thank the organizers of this special issue and the referees for their suggestions and constructive criticism. Part of this research has been made possible by the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO, Agreement 12ZU521N).

Sources and official publications

Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla (AGI)

Contaduría, 1254–1280B, 1282, 1289

Escribanía, 405C, 428A, 431A, 434A, 436D

Filipinas, 193, 229, 268, 595, 858–870, 940, 941, 1034

Ultramar, 657

Archivo Histórico Nacional, Madrid (AHN)

Consejos, 21017

Archivo del Museo Naval, Madrid (AMN)

384, 552, 555, 700

Archivo de la Provincia del Santísimo Rosario, Avila (APSR)

Tomos 194, 223, 224, 226, 228, 229, 230, 232, 233, 235, 236, 237, 247, 262,

263, 274, 275, 276, 281, 282, 284, 289, 304

Archivo de la Universidad de Santo Tomás (AUST)

Libros, Tomo 20

National Archives of the Philippines, Manila (NAP)

Protocolo de Manila, SDS 19765–19789 (1740–1795)Footnote 15

Baltasar Sánchez de Cuenca leg. 2, SDS-19765 (1740–41)

leg. 3, SDS-19766 (1752)

Domingo Cortés de Arquiza leg. 5, SDS-19768 (1755)

Martín Domínguez Zamudio leg. 7, SDS-19770 (1765)

leg. 8, SDS-19771 (1766)

leg. 9, SDS-19772 (1770)

Vicente González de Tagle leg. 13, SDS-19776 (1783)

Manuel del Castillo leg. 27, SDS-19791 (1789)

Miguel José Flores leg. 21, SDS-19784 (1789)

leg. 24, SDS-19787 (1792)

leg. 26, SDS-19789 (1795)

Aduana de Manila

SDS-6207–6209, 6213–6220

Newberry Library

Ayer Vault, MS 1349

Datasets

Rivas Moreno, J.J. (2023) Manila Financial Instruments Database – Correspondencias, 1736–1800 (MFID-C) [v1.0, restricted access]. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10277780.

Blussé, L. and Universiteit Leiden (1983) South China Sea trade, 1681–1792 [open access], DANS, http://dx.doi.org/10.17026/dans-x39-5xed.

Ruiz-Stovel, G. (2021) Manila Intra-Asian Trade database, 1680–1840 (MIAT) [v1.0, restricted access], Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4836052.