Introduction

Depression and anxiety are both prevalent mental illnesses that commonly coexist and are linked to an increased hazard of mortality, as well as an elevated risk of disability, poorer quality of life, and greater financial burden (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016; Druss, Rosenheck, & Sledge, Reference Druss, Rosenheck and Sledge2000; Machado et al., Reference Machado, Veronese, Sanches, Stubbs, Koyanagi, Thompson, Tzoulaki and Carvalho2018). According to the World Health Organization reports, 280 and 301 million people were affected by depression and anxiety worldwide in 2019, and the number of individuals suffering from depression and anxiety is rising significantly (World Health Organization, 2017). Given the increased prevalence and the accompanying adverse outcomes of depression and anxiety, identifying and understanding risk factors, particularly the modifiable ones, has significant implications for mitigating the disease burden.

Previous studies have revealed that metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are individually related to depression (Bautovich, Katz, Smith, Loo, & Harvey, Reference Bautovich, Katz, Smith, Loo and Harvey2014; Kim, Wolf, & Kim, Reference Kim, Wolf and Kim2023; Małyszczak & Rymaszewska, Reference Małyszczak and Rymaszewska2016; Semenkovich, Brown, Svrakic, & Lustman, Reference Semenkovich, Brown, Svrakic and Lustman2015; Ziegelstein, Reference Ziegelstein2001). The existing evidence on the associations of these individual diseases with anxiety is limited and mixed (Cen et al., Reference Cen, Song, Fu, Gao, Zuo and Wu2024; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wee, Low, Koong, Htay, Fan and Seng2021; Małyszczak & Rymaszewska, Reference Małyszczak and Rymaszewska2016). Epidemiological research indicated that metabolic, cardiovascular, and renal diseases often coexist, and growing evidence supported the pathophysiological interactions between these diseases (Grundy, Hansen, Smith, Cleeman, & Kahn, Reference Grundy, Hansen, Smith, Cleeman and Kahn2004; Marassi & Fadini, Reference Marassi and Fadini2023; Rangaswami et al., Reference Rangaswami, Bhalla, Blair, Chang, Costa and Lentine2019). Recently, the term of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome has been introduced by the American Heart Association (AHA), which stressed the significance of holistic management of these diseases to prevent the possible adverse consequences (Ndumele et al., Reference Ndumele, Rangaswami, Chow, Neeland, Tuttle and Khan2023). CKM syndrome was classified into five stages to indicate the risk spectrum (Ndumele et al., Reference Ndumele, Rangaswami, Chow, Neeland, Tuttle and Khan2023). However, the associations of CKM syndrome with depression and anxiety remain unclear.

Social isolation and loneliness are significant social determinants representing specific facets of social connection (World Health Organization, 2021a). Social isolation is an objective assessment of social contacts and interactions, while loneliness refers to the personal perception of being socially isolated (Donovan & Blazer, Reference Donovan and Blazer2020; World Health Organization, 2021b). Existing studies have shown social isolation and loneliness are related to a greater risk of depression and anxiety (Curran, Rosato, Cooper, Mc Garrigle, & Leavey, Reference Curran, Rosato, Cooper, Mc Garrigle and Leavey2019; Domènech-Abella, Mundó, Haro, & Rubio-Valera, Reference Domènech-Abella, Mundó, Haro and Rubio-Valera2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kuang, Xin, Fang, Song, Yang and Wang2023). However, the interaction and joint effects of CKM health and social isolation or loneliness on depression and anxiety remain unknown. Understanding the interaction of CKM health with social connection could help clinicians identify vulnerable populations and develop comprehensive preventive strategies for depression and anxiety.

Therefore, this study sought to explore the prospective association of CKM health with the risk of depression and anxiety. We further examined the multiplicative and additive interactions of CKM health with social isolation or loneliness in relation to the risk of depression and anxiety.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The UK Biobank is a large-scale open-access database with about 0.5 million individuals aged 40–69 years throughout the UK (Palmer, Reference Palmer2007; Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh and Collins2015). Baseline socio-demographic, clinical, behavioral factors, biological samples, and other health-related data were collected between 2006 and 2010 (Palmer, Reference Palmer2007; Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh and Collins2015). The UK Biobank's ethical approval was granted by the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent. Participants who lacked data on obesity (n = 2790) and metabolic risk factors (n = 71 542) were excluded. Participants who had common mental disorders (n = 52 084) at baseline, only had CVD at baseline (n = 1681), or with missing data for covariates (n = 29 358) were excluded. Finally, this study included 344 956 participants in current analyses (online Supplementary Fig. 1). Our study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (von Elm et al., Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007).

Definition of CKM syndrome

According to the AHA's definition, CKM syndrome was defined as a medical condition caused by connections between obesity, diabetes, CKD, and CVD, and it was categorized into five stages (Ndumele et al., Reference Ndumele, Rangaswami, Chow, Neeland, Tuttle and Khan2023). In our study, stage 0 was defined as normal body mass index and waist circumference, normal glucose, normal blood pressure, normal lipid status, and no evidence of CKD or CVD. Stage 1 was characterized by the existence of equal to or more than one of the following: (1) body mass index ⩾25 kg/m2; (2) waist circumference ⩾88/102 cm in women/men; (3) fasting blood glucose ⩾100–124 mg/dL or HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%; and without other metabolic risk factors, CKD, or CVD. Because of the lack of data on subclinical CVD in the UK Biobank, we cannot discriminate stage 3 from stage 2 and therefore combined the two stages as stage 2–3, which was defined by the presence of hypertriglyceridemia (⩾135 mg/dL), hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or CKD. Stage 4 was defined as CVD (heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, stroke, or peripheral artery disease) overlapping with stages 1–3. Details of the definition of these risk factors or diseases are provided in online Supplementary Table 1.

Definition of social isolation and loneliness

The determination of social isolation status was based on the responses to three questions of whether living alone (yes, no), social contact frequency (⩾once a month, <once a month), and leisure or social activity participation (yes, no) (online Supplementary Table 1) (Elovainio et al., Reference Elovainio, Komulainen, Sipilä, Pulkki-Råback, Cachón Alonso, Pentti and Kivimäki2023; Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Jokela, Kivimäki and Elovainio2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Li, Heianza, Fonseca and Qi2023). Each question obtained one point, and the overall score varied from 0 to 3, with an increased score representing a greater degree of social isolation. Those who obtained ⩾2 points were classified into the social isolation group. Loneliness was assessed by the question of whether or not they often feel lonely (yes, no) and the frequency of being able to confide to someone (⩾once a month, <once a month) (Elovainio et al., Reference Elovainio, Komulainen, Sipilä, Pulkki-Råback, Cachón Alonso, Pentti and Kivimäki2023; Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Jokela, Kivimäki and Elovainio2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Li, Heianza, Fonseca and Qi2023). The total loneliness score ranged from 0 to 2 points, and participants who obtained 2 points were classified into the loneliness group (online Supplementary Table 1).

Covariates

We have considered these characteristics as the potential covariates: age, sex (women, men), ethnicity (white, others), Townsend Deprivation Index, education level (degree or above, others), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol consumption status (never, previous, current), and moderate to vigorous physical activity (no, yes). Townsend Deprivation Index is a composite measure derived from four dimensions (unemployment, non-car ownership, non-home ownership, and household overcrowding), calculated using census information linked to residents’ postcodes, with a higher score indicating a higher degree of deprivation (Townsend, Phillimore, & Beattie, Reference Townsend, Phillimore and Beattie1988). Detailed descriptions of these covariates are presented in online Supplementary Table 1.

Assessment of outcomes

Incident cases of depression and anxiety were determined through linkage from hospital admission, self-reported data, and death records. Details of the linkage information are provided in Supplementary Method. The follow-up time for each incident case was coded from recruitment to the first diagnosis of depression or anxiety, death date, or last date of follow-up (31 December 2021), whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

Differences in participants’ characteristics between stages of CKM syndrome were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or χ2 test. Cumulative incidences of outcomes were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox proportional hazard models were fitted to investigate the association of CKM health with incident depression and anxiety. In the base model, we did not adjust for any covariates. In model 2, we adjusted for socio-demographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, and education level) and lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption, smoking status, and physical activity). Then, we further adjusted for social isolation and loneliness.

We also conducted joint analyses to assess the risk of depression and anxiety among participants with varying degrees of social isolation or loneliness and stages of CKM syndrome, with participants who were in stage 0 and were not isolated (or did not feel lonely) as the reference. Possible multiplicative interactions of social isolation or loneliness on the association of CKM health with depression or anxiety were tested by adding a product term of social isolation or loneliness and CKM heath in the models. We used the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) and the attributable proportion (AP) to quantify the additive interaction (Li & Chambless, Reference Li and Chambless2007).

Additionally, some sensitivity analyses were also carried out to assess the robustness of the findings. First, family history of severe depression and annual household income were further adjusted in the multivariate models. Second, we used social isolation and loneliness scores as continuous variables in the models. Third, we included the components of social isolation and loneliness in the adjusted models. Fourth, we conducted Fine–Gray analyses in consideration of death as a competing event (Austin, Lee, & Fine, Reference Austin, Lee and Fine2016). We adjusted for socio-demographic factors and lifestyle factors in the model, and we further adjusted for social isolation and loneliness. Fifth, we excluded incident depression or anxiety cases within the first 2 years of follow-up. Sixth, for covariates with the selection of ‘do not know’ or ‘prefer not to answer’, a separate category was created. Subgroup analyses were also performed to test the possible modification effects of age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, and education level.

A two-sided p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Results

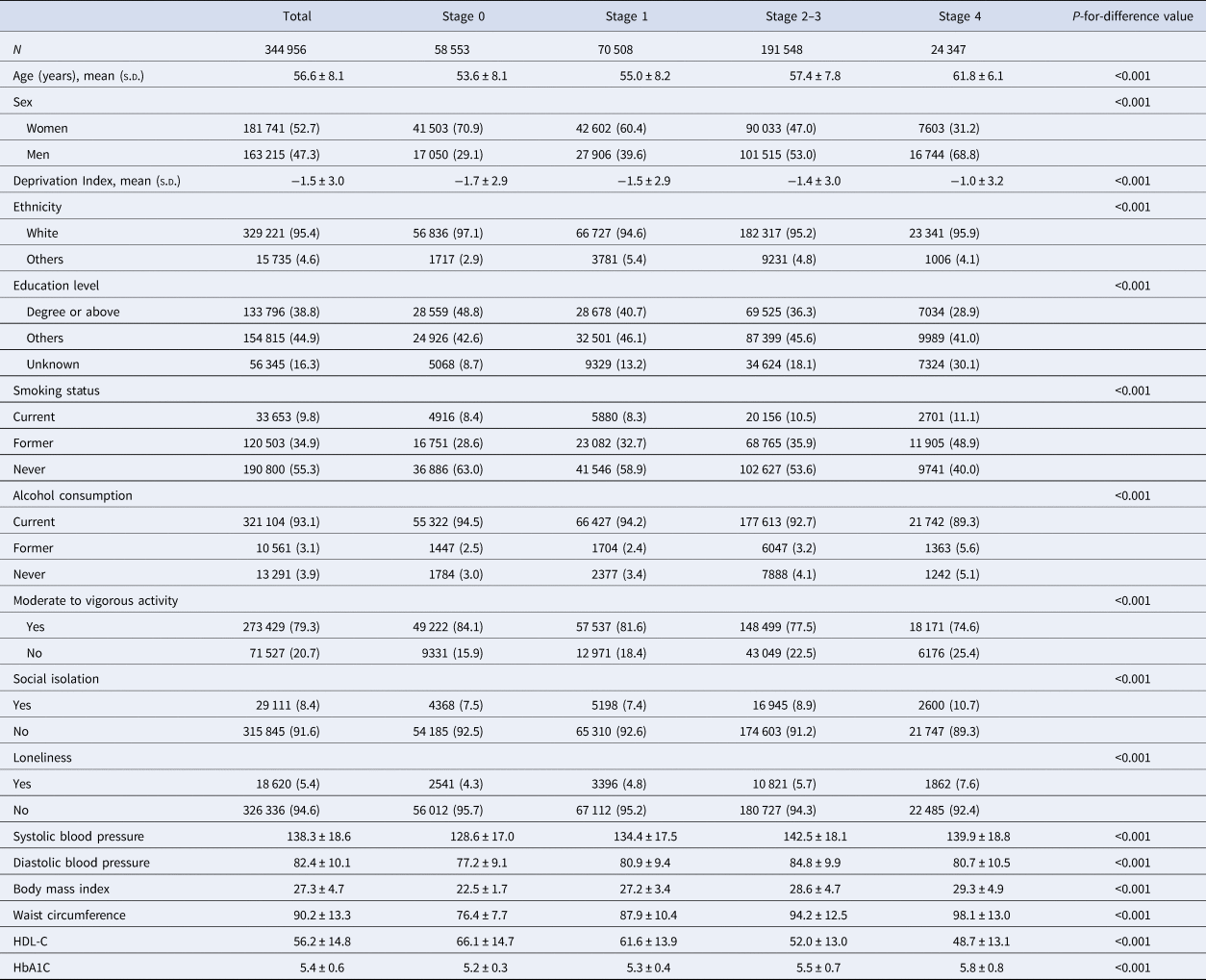

Overall, 344 956 participants were involved in this study (online Supplementary Fig. 1). The mean age of participants was 56.6 ± 8.1 years, and 52.7% were women. At baseline, 58 553 (17.0%), 70 508 (20.4%), 191 548 (55.5%), and 24 347 (7.1%) participants were in stage 0, 1, 2–3, and 4 of CKM syndrome, respectively. Table 1 illustrates the distribution of participants’ characteristics according to stages of CKM syndrome. Participants in later stages were older, having a higher proportion of men, lower levels of education, and more health risk factors (smoking and insufficient physical activity), and were more likely to experience social isolation and loneliness (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants according to stage of CKM syndrome

HDL-C, High density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Note: ANOVA and χ2 test were used to test the differences among categories for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Associations of CKM health with incident depression and anxiety

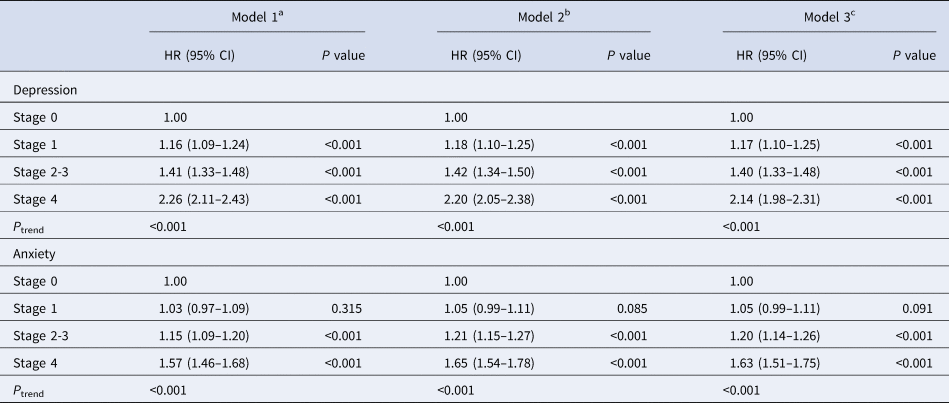

Over a median follow-up of 12.8 years (IQR 12.0–13.5 years), we identified 12 582 (3.7%) and 14 267 (4.1%) incident cases of depression and anxiety, respectively. The cumulative incidence of outcomes was highest in stage 4 (log-rank P < 0.001) compared with earlier stages (online Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 2). The associations of CKM stages with depression and anxiety displayed dose–gradient relationships (both P trend < 0.001) (Table 2). After adjustment for socio-demographic factors and lifestyle factors, compared with participants in stage 0, the HRs for depression were 1.18 (95% CI 1.10–1.25, P < 0.001), 1.42 (95% CI 1.34–1.50, P < 0.001), and 2.20 (95% CI 2.05–2.38, P < 0.001) for participants in stage 1, 2–3, and 4, respectively. Similarly, participants in stage 2–3 (HR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.27, P < 0.001) and stage 4 (HR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.54–1.78, P < 0.001) had a greater risk of incident anxiety when adjusting for socio-demographic and lifestyle factors. The associations did not alter after including social isolation and loneliness in the models (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of stages of CKM syndrome with risk of depression and anxiety

CI, confidence interval; CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; HR, hazard ratio.

a Model 1 was not adjusted for covariates.

b Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity.

c Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, social isolation, and loneliness.

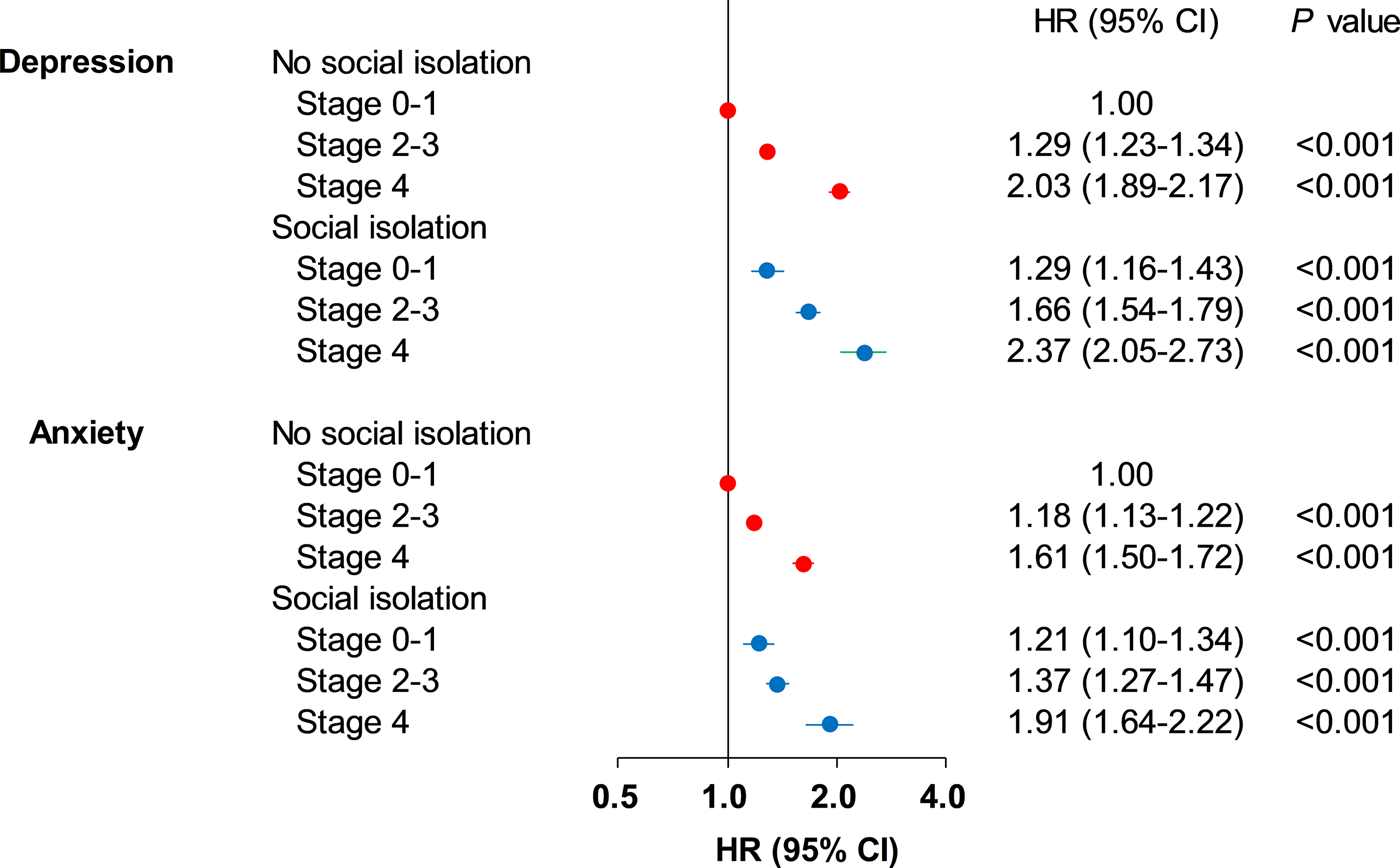

Joint associations of social isolation or loneliness and CKM health with incident depression and anxiety

In Fig. 1, the joint associations of social isolation and the stage of CKM syndrome with the risk of depression and anxiety have been shown. Compared with the reference group, individuals with social isolation and in stage 4 had an adjusted HR of 2.37 (95% CI 2.05–2.73, P < 0.001) and an adjusted HR of 1.91 (95% CI 1.64–2.22, P < 0.001) for incident depression and anxiety, respectively (Fig. 1). Participants reported being lonely and in stage 4 had a 344% greater risk of depression (HR = 4.44, 95% CI 3.89–5.07, P < 0.001) and 158% higher risk of anxiety (HR = 2.58, 95% CI 2.21–3.01, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). An additive interaction was observed between social isolation and the stage of CKM syndrome on the risk of depression (RERI = 0.11, 95% CI 0.04–0.17; AP = 0.06, 95% CI 0.04–0.09, P = 0.003) (online Supplementary Table 3). We also found additive interactions between loneliness and CKM health on the risk of depression (RERI = 0.42, 95% CI 0.34–0.50; AP = 0.14, 95% CI 0.10–0.17, P < 0.001) and anxiety (RERI = 0.17, 95% CI 0.09–0.25; AP = 0.10, 95% CI 0.08–0.13, P < 0.001) (online Supplementary Table 4). We did not observe a significant multiplicative interaction between social isolation or loneliness and the stage of CKM syndrome on incident depression and anxiety (online Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Figure 1. Joint associations of social isolation and the stage of CKM syndrome with incident depression and anxiety. HRs were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 2. Joint associations of loneliness and the stage of CKM syndrome with incident depression and anxiety. HRs were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Deprivation Index, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

After adjustment for family history of severe depression or annual household income, the association of CKM health with depression and anxiety remained consistent (online Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). When treating social isolation score and loneliness score as continuous variables, consistent results have been found (online Supplementary Table 9). When adjusting components of social isolation and loneliness in the models, the results remained similar (online Supplementary Table 10). Consistent results have been yielded when considering the competing risk of death (online Supplementary Table 11). The HRs did not substantially alter when excluding incident depression or anxiety cases during the initial 2 years of follow-up (online Supplementary Table 12). When defining ‘do not know/ prefer not to answer’ in a separate category for some covariates, no substantial change in the association has been observed (online Supplementary Table 13). We did not find the modification effects of most covariates on the association of CKM heath with depression and anxiety, except ethnicity (online Supplementary Tables 14 and 15).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of 344 956 participants from the UK Biobank, we observed dose–response associations between stages of CKM syndrome with depression and anxiety. Compared with participants in stage 0, those in later stages had greater risks of incident depression and anxiety. Significant additive interactions between CKM health and loneliness in relation to depression and anxiety have been observed. A significant additive interaction between CKM health and social isolation on the risk of depression has also been detected. From a public health perspective, these findings suggested that improving CKM health could potentially serve as an effective strategy for preventing depression and anxiety, underlining the importance of assessing CKM health and identifying individuals in later CKM stages, as they had an increased likelihood of developing depression and anxiety. Our findings also implied the necessity of a comprehensive and targeted approach to promote CKM health and social connection simultaneously to improve mental health.

Our study is the first demonstration of the significant association of CKM health with depression and anxiety. The existing studies have shown the association of individual diseases (including diabetes, coronary heart disease, and CKD) with an increased risk of depression (Bautovich et al., Reference Bautovich, Katz, Smith, Loo and Harvey2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Wolf and Kim2023; Małyszczak & Rymaszewska, Reference Małyszczak and Rymaszewska2016; Semenkovich et al., Reference Semenkovich, Brown, Svrakic and Lustman2015; Ziegelstein, Reference Ziegelstein2001). Some previous studies also reported the relationship between cardiometabolic disease and greater risks of depression (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Ma, He, Lin, Zhang, Cheng and Bai2022; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Luo, Han, Wang, Yao, Su and Xu2022; Ronaldson et al., Reference Ronaldson, Arias de la Torre, Prina, Armstrong, Das-Munshi, Hatch and Dregan2021). A cross-sectional study suggested a cumulative dose-dependent connection between the number of cardiometabolic diseases and depression; participants with more than three conditions of cardiometabolic disease had a 113% greater risk of depression (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Ma, He, Lin, Zhang, Cheng and Bai2022). The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study suggested the increasing number of cardiometabolic diseases was related to depressive symptoms (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Luo, Han, Wang, Yao, Su and Xu2022). Conclusions on the impact of individual diseases on anxiety are inconsistent. For example, some previous investigations did not show a correlation between diabetes and incident anxiety over more than 10 years of follow-up (Engum, Reference Engum2007; Marrie et al., Reference Marrie, Patten, Greenfield, Svenson, Jette, Tremlett and Svenson2016); however, another study observed diabetes was related to 2.6 times increased risk of anxiety disorder among Australian women (Hasan, Clavarino, Dingle, Mamun, & Kairuz, Reference Hasan, Clavarino, Dingle, Mamun and Kairuz2015). Several studies showed that metabolic syndrome was not related to a greater risk of anxiety (Skilton, Moulin, Terra, & Bonnet, Reference Skilton, Moulin, Terra and Bonnet2007; Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Nakao, Nomura, Inoue, Tsurugano, Shinozaki and Yano2009), whereas some other studies reported a significant association of metabolic syndrome with anxiety (Cen et al., Reference Cen, Song, Fu, Gao, Zuo and Wu2024; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Chen, Zhou, Cao, Li, Ding and Tang2023). In our study, compared with participants without CKM risk factors (stage 0), those with metabolic risk factors (stage 1), with metabolic risk factors plus CKD (stage 2–3), and with concomitant metabolic disease, CKD, and CVD (stage 4) had 17, 40, and 114% greater risk of depression. We also observed that participants in stage 2–3 and 4 of CKM syndrome had greater risks of anxiety compared with those in stage 0. These findings reveal that it might be feasible to focus on implementing stage-specific strategies to halt or delay the development of CKM syndrome, especially to prevent CVD, to decrease the likelihood of developing depression and anxiety.

Accumulating evidence indicates that the pathophysiological mechanisms of metabolic disease, CVD, and CKD are interrelated. For instance, metabolic syndrome is correlated to the development of nearly all CVD subcategories (Wilson, D'Agostino, Parise, Sullivan, & Meigs, Reference Wilson, D'Agostino, Parise, Sullivan and Meigs2005); type 2 diabetes has the potential to result in renal and vascular damage (Burrows, Koyama, & Pavkov, Reference Burrows, Koyama and Pavkov2022); and CKD plays a significant role in amplifying cardiovascular risk (Go, Chertow, Fan, McCulloch, & Hsu, Reference Go, Chertow, Fan, McCulloch and Hsu2004; van der Velde et al., Reference van der Velde, Matsushita, Coresh, Astor, Woodward, Levey and Manley2011). Currently, an AHA presidential advisory put forward the concept of CKM syndrome and emphasized the efforts to enhance CKM care (Ndumele et al., Reference Ndumele, Rangaswami, Chow, Neeland, Tuttle and Khan2023). Several potential mechanisms have been proposed for the relationship between CKM syndrome and depression and anxiety. CKM syndrome could be related to a greater risk of symptom burden, frailty, chronic pain, and decreased quality of life, which could result in increased emotional burden (Katon, Lin, & Kroenke, Reference Katon, Lin and Kroenke2007; Makovski, Schmitz, Zeegers, Stranges, & van den Akker, Reference Makovski, Schmitz, Zeegers, Stranges and van den Akker2019; Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, McDonald, Correia, Raue, Meade, Nicholas and Arean2017; Soysal et al., Reference Soysal, Veronese, Thompson, Kahl, Fernandes, Prina and Stubbs2017; Vetrano et al., Reference Vetrano, Palmer, Marengoni, Marzetti, Lattanzio and Roller-Wirnsberger2019). Additionally, inflammation has been recognized as a major pathological factor behind depression and anxiety, and most chronic physical diseases are marked by a significant inflammatory burden (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Hao, Wang, Zhang and Liu2023; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Lin, Jiang, Tian, Xu, Wang and Zhuo2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Li, Chen, Xiao, Liu, Li and Cheng2021). Besides, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may contribute to the development of depression among individuals with CKM syndrome (Belvederi Murri et al., Reference Belvederi Murri, Pariante, Mondelli, Masotti, Atti, Mellacqua and Amore2014). Given the complexity of the interrelation between cardiovascular, metabolic, and kidney diseases, comprehensive management approaches to these diseases should be undertaken to reduce the disease burden of mental disorders. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the pathways involved in the association of CKM health with depression and anxiety.

The current study observed a substantial additive interaction, which has more public health significance than multiplicative interaction, between CKM health and social isolation in relation to depression. We also found that the combination of poor CKM health and loneliness might act synergistically to increase the risk of depression and anxiety. With growing public health concerns about social isolation and loneliness, the World Health Organization has launched the Commission on Social Connection (2024–2026) to tackle the urgent global health threats (World Health Organization, 2023). Strong evidence has shown that the lack of social connection enhances the hazard of physical and mental problems, such as depression and anxiety (World Health Organization, 2023). However, this is the first attempt to examine the interaction and joint effect of social connection and CKM health on depression and anxiety. Specifically, the concurrence of stage 4 of CKM syndrome and loneliness could lead to an additional 14% and 10% of cases of depression and anxiety, respectively. Our findings underscore the significance of public health countermeasures to promote CKM health, especially among those with loneliness or social isolation. Additionally, more collaborative action should be taken to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of social isolation and loneliness.

Strengths and limitations

This study has some major strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the association of CKM heath with depression and anxiety. We evaluated both multiplicative and additive interactions between CKM health and social connection in relation to depression and anxiety. Our findings could provide valuable information for clinicians to identify vulnerable populations at an increased risk of depression and anxiety. The large sample size and long follow-up period of the UK Biobank allowed us to perform the stratified analyses with sufficient statistical power, and we observed consistent results in most subpopulations.

Nevertheless, it is important to interpret our findings with caution due to some limitations. First, the nature of observational study poses challenges in establishing the causal relationship, even if the results in sensitivity analysis were consistent when excluding incident cases during the initial 2 years of follow-up. Second, although this study has adjusted for various potential confounders, there could be unmeasured or residual confounding. Third, because there is insufficient data on subclinical CVD in the UK Biobank, we are unable to separate participants with subclinical CVD in CKM syndrome (defined as stage 3 of CKM syndrome by the AHA) (Ndumele et al., Reference Ndumele, Rangaswami, Chow, Neeland, Tuttle and Khan2023); therefore, we combined stage 3 with stage 2 as stage 2–3 in our study. Fourth, social isolation and loneliness were defined by some simple questions. Nevertheless, the questions used in our study have been modified from validated scales and applied in other research (Elovainio et al., Reference Elovainio, Komulainen, Sipilä, Pulkki-Råback, Cachón Alonso, Pentti and Kivimäki2023; Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Jokela, Kivimäki and Elovainio2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Li, Heianza, Fonseca and Qi2023). Fifth, the study participants in the UK Biobank were recruited from a community context, which may introduce participation bias, as this population is likely to be more affluent and healthier than the general UK population. Consequently, the effect sizes reported in this study may represent conservative estimates. Last, the majority of individuals in this study were of European descent, and the generalizability of our study results to other ethnic groups could be limited.

Conclusion

Our study suggested that poor CKM health was independently associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety. Besides, we found significant additive interactions between loneliness or social isolation and the stage of CKM syndrome. These findings support the importance of comprehensive interventions to simultaneously promote CKM health and social connection in improving mental health.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724002381.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to UK Biobank participants. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 90492.

Funding statement

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Fanfan Zheng, grant number 82373665 and Wuxiang Xie, grant number 81974490), the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Fanfan Zheng, grant number 2021-RC330-001), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Xinghe Huang, grant number 3332023084).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The UK Biobank has obtained ethical consent from the North West Multi-center Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.