Introduction

The world population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and peak at approximately 10.4 billion people in 2086 (Ritchie et al. Reference Ritchie, Rodés-Guirao and Roser2024). This prospect creates unprecedented demands for more efficient and sustainable agriculture. Consequently, minimizing yield losses is a crucial step to achieving optimal crop productivity. Weed management is a major challenge for agricultural systems worldwide, and substantial yield losses are expected if weeds are left uncontrolled. Oerke (Reference Oerke2006) identified weed competition as the biggest threat to the major crops cultivated worldwide, with an average of 34% potential yield loss. In the United States and Canada, researchers estimated 50% and 52% potential yield loss of corn (Zea mays L.) and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], respectively, if weeds are left uncontrolled (Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Dille, Burke, Everman, VanGessel, Davis and Sikkema2016, Reference Soltani, Dille, Burke, Everman, VanGessel, Davis and Sikkema2017).

Chemical weed management is the most adopted and cost-effective weed control method in the United States (Owen Reference Owen2016); however, the rapid evolution of herbicide resistance threatens the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Tranel, Hager, Schutte, Wu, Chatham and Davis2016). Currently, 533 unique cases of herbicide resistance have been documented worldwide across 273 species (Heap Reference Heap2024). Italian ryegrass is a winter annual weed species notorious for evolving resistance to herbicides with 75 unique cases of herbicide resistance across eight distinct sites of action (SOAs) reported worldwide (Heap Reference Heap2024). In the United States, this weed has evolved resistance to seven herbicide SOAs, including groups 1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 15, and 22 (as categorized by the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee [HRAC] and the Weed Science Society of America [WSSA]) (Heap Reference Heap2024; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Hulting and Mallory-Smith2014).

Italian ryegrass has ranked as the most troublesome weed in small grains and among the top 20 most troublesome weeds in corn (Webster and Nichols Reference Webster and Nichols2012). Previous studies have shown significant yield losses of wheat (Triticum aestivum L. 'Stephens’) and corn if Italian ryegrass is left uncontrolled, with up to 92% and 60% yield loss, respectively (Hashem et al. Reference Hashem, Radosevich and Dick2000; Nandula Reference Nandula2014). Moreover, Italian ryegrass has vigorous growth, with greater leaf production rates and root surface area than wheat (Ball et al. Reference Ball, Klepper and Rydrych1995; Cralle et al. Reference Cralle, Fojtasek, Carson, Chandler, Miller, Senseman, Bovey and Stone2003). Bararpour et al. (Reference Bararpour, Norsworthy, Burgos, Korres and Gbur2017), while investigating morphological characteristics of Lolium ssp. accessions from Arkansas, reported that Italian ryegrass produced more tillers, more spikes per plant, and more spikelets per spike than rigid (L. rigidum Gaudin), perennial (L. perenne L.), and poison (L. temulentum L.) ryegrass, which resulted in Italian ryegrass producing 3.2 to 10.4 times more seeds per plant than any of the other Lolium species and as much as 45,000 seeds plant–1.

In North Carolina, Italian ryegrass has been a problem in wheat and other crops since the late 1970s (Liebl and Worsham Reference Liebl and Worsham1987). A state-wide herbicide investigation of Italian ryegrass accessions revealed widespread resistance to herbicides in groups 1 and 2 (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Taylor and Everman2021). Recently, a biotype resistant to nicosulfuron, clethodim, glyphosate, and paraquat (groups 1, 2, 9, and 22, respectively) was identified in the southern Piedmont region of North Carolina (De Sanctis et al. Reference de Sanctis, Cahoon, Everman, Gannon and Taylor2023), an important wheat production region of the state (USDA-NASS 2023). However, due to limited postemergence herbicide options labeled for use on small grains, growers have continued to rely on herbicides that inhibit acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) (Group 1) and acetolactate synthase (ALS) (Group 2) to manage Italian ryegrass (Carleo and Everman Reference Carleo and Everman2020), thereby increasing the selection for herbicide-resistant biotypes.

To mitigate the evolution and spread of herbicide resistance biotypes, alternative control tactics must be implemented to successfully manage multiple herbicide–resistant weed biotypes (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos, Witt and Barrett2012). Among alternative control tactics, tillage, fall-applied residual herbicides, and cover crops have been studied for managing herbicide-resistant winter annual weeds across different U.S. agronomic systems (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Eubank, Bond, Golden and Edwards2014, Reference Bond, Allen, Seale and Edwards2022; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Kruger, Young and Johnson2010; Maity et al. Reference Maity, Young, Schwartz-Lazaro, Korres, Walsh, Norsworthy and Bagavathiannan2022; Pittman et al. Reference Pittman, Barney and Flessner2019; Sherman et al. Reference Sherman, Haramoto and Green2020; Trusler et al. Reference Trusler, Peeper and Stone2007). Tillage can be an effective practice for managing troublesome weeds when used in conjunction with a sound herbicide program (Farmer et al. Reference Farmer, Bradley, Young, Steckel, Johnson, Norsworthy, Davis and Loux2017). However, due to its topography and soil characteristics, the southern Piedmont region of North Carolina has an elevated risk of soil erosion, which may limit tillage in this area (Daniels Reference Daniels1987; Trimble Reference Trimble1975). Furthermore, many North Carolina farmers are enrolled in government soil conservation programs that may restrict tillage practices (USDA-NRCS 2024; NCDACS 2024). Cover crops planted after a cash crop harvest are a promising weed control tactic that may suppress Italian ryegrass germination and growth during the late fall to early spring (Reeves Reference Reeves2022), and may help reduce the risk of erosion and improve soil health (Dabney et al. Reference Dabney, Delgado and Reeves2001). However, Italian ryegrass may germinate before or simultaneously to cover crops (Mohler et al. Reference Mohler, Teasdale and DiTommaso2021), which can reduce cover crop’s establishment and competitiveness. In addition, previous research reports winter weed suppression to be driven by early-season cover crop establishment and growth (Baraibar et al. Reference Baraibar, Hunter, Schipanski, Hamilton and Mortensen2018; Dorn et al. Reference Dorn, Jossi and Van Der Heijden2015). Fall-applied residual herbicides have proven to be an effective tool to control Italian ryegrass during the late fall and early winter months; however, Italian ryegrass control is expected to diminish over time, allowing it to repopulate the area as residual herbicides lose their activity (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Eubank, Bond, Golden and Edwards2014). It is hypothesized that combining fall-applied residual herbicides and cover crops residual herbicides will limit early-season Italian ryegrass interference with cover crops. Once established, the cover crops will be crucial for late-winter and early-spring Italian ryegrass suppression, and by that time, residual herbicides would have lost their activity. However, few studies have investigated fall-planted cover crop tolerance to preemergence herbicides applied at planting, while many studies have investigated the potential for residual herbicides to carry over from their use in a cash crop to a fall-planted cover crop (Cornelius and Bradley Reference Cornelius and Bradley2017a; Palhano et al. Reference Palhano, Norsworthy and Barber2018; Rector et al. Reference Rector, Pittman, Beam, Bamber, Cahoon, Frame and Flessner2020). Therefore, the objectives of this study were to evaluate Italian ryegrass control and seed production as affected by cover crops and fall-applied residual herbicides and investigate cereal rye (Secale cereale L.) and crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum L.) tolerance to different residual herbicides applied at planting.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

Experiments were conducted at the Piedmont Research Station near Salisbury, NC, during the fall/winter of 2021–22 and at the Central Crops Research Station near Clayton, NC, during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 fall/winter seasons. Soils included a Lloyd clay loam (fine-loamy, mixed, active, thermic typic hapludalfs), 5.4 pH, with 0.4% humic matter at Salisbury, and a Wagram loamy sand (coarse-loamy, siliceous, active, acid, thermic cumulic humaquepts), 5.6 pH, with 0.8% humic matter at Clayton. Following the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services soil test report recommendations at Salisbury, 336 kg ha–1 of 10-20-20 fertilizer plus 2,500 kg ha–1 of lime was applied to optimize cover crop growth. Experiments were conducted in a no-till system with cover crops planted on October 20, 2021, at the Salisbury location. At the Clayton location, cover crops were planted on October 19, 2021, and October 19, 2022, into soil prepared with conventional tillage. Paraquat at 840 g ai ha–1 was used just before cover crop planting to ensure fields were weed-free at planting. Cover crops were drilled into 19-cm rows with cereal rye and crimson clover seeded at 80 and 18 kg ha–1, respectively. All research sites were naturally infested with Italian ryegrass.

Experimental Design and Treatments

The experiment was conducted as a split-plot design with four replications. The main plots consisted of three cover crop treatments organized in a randomized complete block design. Subplots consisted of five fall-applied residual herbicide treatments. The three cover crop treatments consisted of no cover crop (fallow), cereal rye, and crimson clover; whereas the fall-applied residual herbicides included no residual herbicides (No-PRE), and flumioxazin, metribuzin, pyroxasulfone, and S-metolachlor applied preemergence (Table 1). From hereinafter, the fallow treatment without residual herbicides will be referred to as nontreated. Residual herbicides were applied immediately after planting with a handheld CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer calibrated to deliver 140 L ha–1 equipped with six AIXR11002 flat-fan nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL) spaced 45 cm apart. Subplot dimensions were 4 m × 12 m.

Table 1. List of herbicide products, rates, manufacturers, and WSSA herbicide group numbers used in field experiments conducted in 2021–22 and 2022–23 seasons. a

a Abbreviation: WSSA, Weed Science Society of America.

Data Collection

Data collection consisted of biweekly visual estimations of cover crop injury and Italian ryegrass control, with 0% representing no control or injury and 100% representing complete control or plant death. Italian ryegrass density was recorded 8 wk after planting (WAP), while Italian ryegrass and cover crop biomass were collected at 24 WAP. Italian ryegrass seeds were collected once most plants reached maturity, occurring in early June during both years.

Density, aboveground biomass, and seeds were collected using two 0.25-m2 quadrants randomly placed within the corresponding subplot. Data from each quadrant were averaged and transformed to 1 m2 basis. Cover crop and Italian ryegrass fresh biomass were placed in separate paper bags, dried in an oven at 55 C for 14 d until constant mass, and then weighed. Italian ryegrass seed samples were placed in paper bags and allowed to dry at 25 C for 21 d. Samples were manually threshed, cleaned using a series of standard laboratory sieves, and then weighted. Seed production was determined by weighing 50 seed subsamples to calculate 100 weights of cleaned seed.

Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to ANOVA to test for significance of fixed and random effects and means separated using the R base package (R Core Team 2019) and Agricolae package (Mendiburu Reference Mendiburu2019). Because only one year of data was collected from Salisbury, separate analyses were conducted for each location. For Salisbury, replications were treated as a random effect, while cover crop and residual herbicide as fixed effects. For data from Clayton, year was included as a fixed effect. Moreover, for cover crop injury, fallow treatments and cover crops without herbicides were excluded from the analyses; for cover crop biomass, only fallow treatments were removed. In Italian ryegrass visual estimates of control at 8 and 24 WAP, fallow with no-PRE treatment was considered the nontreated check and it was removed from the analysis. Fisher’s least significant difference was used to separate means at α = 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Cover Crop Injury and Biomass Production

At the Clayton location, there was a significant year-by-cover crop-by-residual herbicide interaction for visual estimates of injury at 8 and 24 WAP and cover crop biomass. Therefore, to better interpret results, data were analyzed separately between 2021–22 and 2022–23. At the Salisbury location, the cover crop-by-residual herbicide interaction was significant for all variables at the α = 0.05 level.

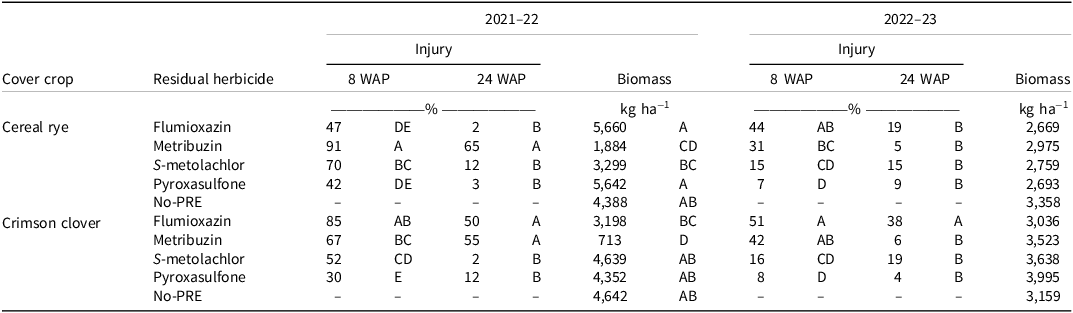

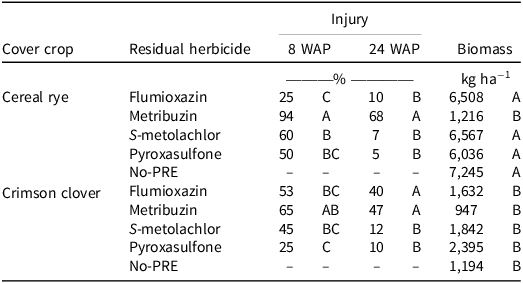

During 2021–22 in Clayton, all residual herbicides injured cereal rye and crimson clover at 8 WAP (Table 2). However, at 24 WAP, metribuzin (65%) was the only injurious treatment to cereal rye. Crimson clover was injured by flumioxazin and metribuzin, resulting in 55% and 50% injury, respectively. Injury from all other residual herbicides was transient and resulted in ≤12% crimson clover and cereal rye injury. Similarly, Wallace et al. (Reference Wallace, Curran, Mirsky and Ryan2017) reported minimal to no injury from pyroxasulfone and S-metolachlor applied preemergence in red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) with biomass similar to the nontreated check. Surprisingly, in 2022–23, metribuzin injury to cereal rye and crimson clover was 5% and 6%, respectively. Studies investigating metribuzin movement in the soil report the herbicide is readily leached in coarse soils with low organic matter (Kim and Feagley Reference Kim and Feagley1998; Shaner Reference Shaner2014). At the Clayton site in 2022–23, 56 mm of rain fell 10 d after planting (Figure 1), which could have caused metribuzin to leach beyond the cover crop root zone. This may explain why cover crop injury by metribuzin was reduced in 2022–23. At the same time, flumioxazin (38%) was the most injurious herbicide to crimson clover. The response of the cover crop to residual herbicides at the Salisbury location was similar to that of Clayton in 2021–22. All residuals were injurious at 8 WAP. At 24 WAP, metribuzin injured cereal rye by 68%, whereas metribuzin and flumioxazin injured crimson clover by 47% and 40%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2. Cereal rye and crimson clover visible estimates of injury at 8 and 24 wk after planting and biomass production as influenced by residual herbicide treatments in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 seasons at the Central Crops Research Station, located near Clayton, NC.a,b

a Abbreviations: PRE, preemergence; WAP, weeks after planting.

b Means presented within the same column and with no common letters are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference test at α = 0.05 level.

Figure 1. Cumulative rainfall at the Piedmont Research Station near Salisbury, NC, during the fall/winter of 2021–22 (orange) and at the Central Crops Research Station near Clayton, NC, during 2021–22 (blue) and 2022–23 (green) fall/winter seasons.

Table 3. Cereal rye and crimson clover visible estimates of injury at 8 and 24 wk after planting and biomass production as influenced by cover crop and residual herbicide treatments in the 2021–22 season at the Piedmont Research Station, located near Salisbury, NC.a,b

a Abbreviations: PRE, preemergence; WAP, weeks after planting.

b Means presented within the same column and with no common letters are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference test at α = 0.05 level.

Previous research reports that 5,000 kg ha−1 of cover crop biomass is necessary to achieve satisfactory weed suppression (Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, Martinez-Feria, Weisberger, Carlson, Basso and Basche2020). In 2021–22 at the Clayton location, only cereal rye plus flumioxazin (5,660 kg ha−1) or pyroxasulfone (5,642 kg ha−1) reached that threshold and yielded significantly higher biomass than cereal rye plus metribuzin (1,884 kg ha−1). Within crimson clover treatments, all residual herbicides, except metribuzin (713 kg ha−1), resulted in comparable biomass ranging from 3,198 to 4,642 kg ha−1. However, no biomass differences were observed between cover crop species or preemergence herbicide treatments from the Clayton location in 2022–23. Overall, less cover crop biomass was produced at this location and no treatments reached the 5,000 kg ha−1 biomass threshold (2,669 to 3,995 kg ha−1). Cereal rye plots produced the greatest biomass at Salisbury, ranging from 6,036 to 7,245 kg ha−1, except for metribuzin, which resulted in 1,216 kg ha−1. Despite differences in residual herbicide injury, all crimson clover plots yielded comparable biomass (947 to 2,395 kg ha−1). Ribeiro et al. (Reference Ribeiro, Oliveira, Smith, Santos and Werle2021), while investigating cereal rye sensitivity to different preemergence herbicides under greenhouse conditions, reported 70% biomass reduction from metribuzin. The same researchers also reported that planting cereal rye 32 to 38 d after metribuzin was applied still decreased cereal rye biomass by 35% compared to nontreated plants. In the same study, flumioxazin, pyroxasulfone, and S-metolachlor reduced cereal rye biomass at 30 d after planting by 60%, 48%, and 61%, respectively. Cornelius and Bradley (Reference Cornelius and Bradley2017a), while investigating the risks of herbicide carryover to several cover crops, reported that metribuzin and S-metolachlor applied 3 mo before cover crop plating reduced crimson clover biomass by 29%. Furthermore, those researchers concluded that crimson clover was the most sensitive cover crop to herbicide carryover among eight cover crop species including Australian winter pea (Pisum sativum L); cereal rye, hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth), Italian ryegrass, oat (Avena sativa L.), soybean, and wheat. In this research, flumioxazin, due to significant injury across both sites and years, was considered injurious to crimson clover. Although environmental conditions likely reduced metribuzin injury at Clayton in 2022–23, this herbicide still poses a risk to cereal rye and crimson clover; therefore, metribuzin was considered an injurious herbicide for both cover crops.

Italian Ryegrass Control, Biomass, and Seed Production

At Clayton, the year-by-cover crop-by-residual herbicide interaction was significant for Italian ryegrass visible control estimates at 8 and 24 WAP, biomass, and seed production. Therefore, data for Clayton in 2021–22 and 2022–23 were analyzed separately. At Salisbury, the cover crop-by-residual herbicide interaction was significant for all variables at the α = 0.05 level.

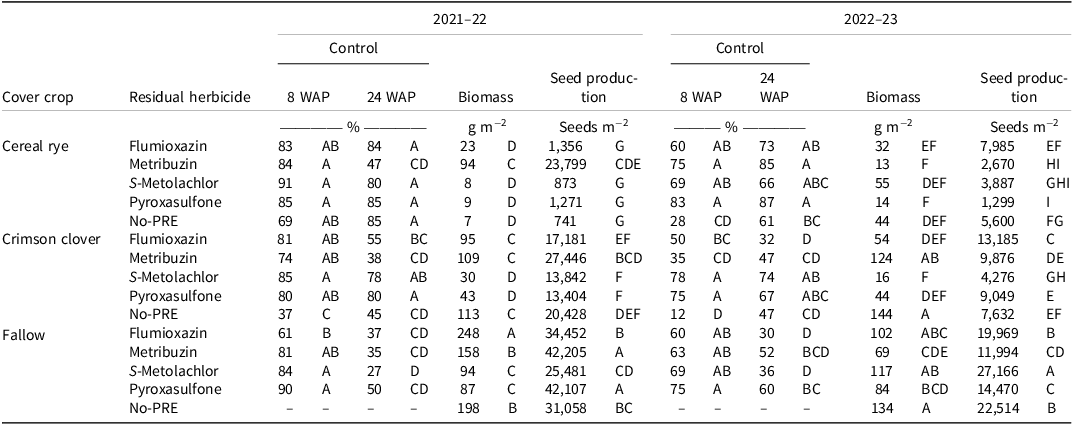

At Clayton in 2021–22, Italian ryegrass control 8 WAP in plots receiving both a cover crop and residual herbicides were similar. In plots planted with cereal rye, residual herbicides controlled Italian ryegrass by 83% to 92%, whereas herbicides used with crimson clover controlled the weed by 74% to 81% 8 WAP (Table 4). By 24 WAP, Italian ryegrass control in cereal rye without herbicides (85%) was similar to cereal rye plus herbicides (80% to 85%), except for metribuzin, which resulted in 47% control due to cereal rye injury. Moreover, Italian ryegrass control in fallow reduced over time regardless of residual herbicide use; for instance, S-metolachlor used without a cover crop controlled Italian ryegrass by 84% at 8 WAP and, by 24 WAP, control was reduced to 27%. At Clayton in 2022–23, all cereal rye plus residual herbicide treatments resulted in similar Italian ryegrass control at 8 WAP (60% to 83%) and were more effective than cereal rye without a residual herbicide (28%). In the fallow system, all residual herbicides used resulted in comparable Italian ryegrass control (60% to 75%). At 24 WAP, Italian ryegrass control in cereal rye plots differed from the previous season. Cereal rye plus pyroxasulfone (88%) or metribuzin (85%) resulted in greater Italian ryegrass control than cereal rye plots without a residual herbicide (61%). Additionally, flumioxazin (73%) and S-metolachlor (66%) applied to cereal rye controlled Italian ryegrass to an extent that was similar to cereal rye without a residual herbicide.

Table 4. Italian ryegrass visible estimates of control, biomass, and seed production as influenced by cover crop and residual herbicide treatments in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 seasons at the Central Crops Research Station, located in Clayton, NC.a,b

a Abbreviations: PRE, preemergence; WAP, weeks after planting.

b Means presented within the same column and with no common letters are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference test at α = 0.05 level.

In Salisbury, Italian ryegrass control at 8 WAP with pyroxasulfone was similar across all cover crop treatments, ranging from 86% to 96%. Furthermore, cereal rye plus metribuzin (93%) or pyroxasulfone (96%) resulted in greater Italian ryegrass control than cereal rye without herbicides (68%). A similar trend was observed in crimson clover, in which the presence of metribuzin (70%) or pyroxasulfone (86%) resulted in greater control than crimson clover without herbicides (55%). At 24 WAP Italian ryegrass control in cereal rye no-PRE herbicide was 82% and was comparable to cereal rye plus pyroxasulfone (83%), S-metolachlor (83%), and flumioxazin (75%; Table 5). However, when metribuzin was used, Italian ryegrass control was reduced to 37%. In 2021–22 at both locations, metribuzin injury to cereal rye reduced cover crop competitiveness; consequently, Italian ryegrass was able to repopulate the plot once residual activity of the herbicide diminished.

Table 5. Italian ryegrass visible estimates of control, biomass, and seed production as influenced by cover crop and residual herbicide treatments in the 2021–22 season at the Piedmont Research Station, located in Salisbury, NC.a,b

a Abbreviations: PRE, preemergence; WAP, weeks after planting.

b Means presented within the same column and with no common letters are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference test at α = 0.05 level.

Limited information exists on the combined activity of cover crops plus residual herbicides for controlling Italian ryegrass; however, fall-applied residual herbicides have been studied for Italian ryegrass management. Bond et al. (Reference Bond, Eubank, Bond, Golden and Edwards2014) reported that pyroxasulfone (165 g ai ha–1) and S-metolachlor (1,420 g ai ha–1) controlled Italian ryegrass by 61% and 52% 24 WAP, which equated to 79% and 82% reductions in biomass, respectively. The researchers also observed that Italian ryegrass control reduced over time. For example, pyroxasulfone applied at 50 g ai ha–1 controlled Italian ryegrass by 84% 14 WAP but control decreased to 55% at 24 WAP. Similarly, Burrell (2024) reported that fall-applied pyroxasulfone controlled Italian ryegrass by 63% at 18 WAP, whereas S-metolachlor applied at the same time resulted in 74%. From a cover crop standpoint, cereal rye and crimson clover may suppress other troublesome winter annual weeds. Pittman et al. (Reference Pittman, Barney and Flessner2019) reported ≥88% horseweed density reduction in cereal rye or crimson clover cover crops when compared to the fallow. In contrast, Cornelius and Bradley (Reference Cornelius and Bradley2017b) reported that cereal rye and crimson clover reduced winter annual weed density by 68% and 25%, respectively. Therefore, under ideal conditions, cover crops alone may provide excellent winter annual weed suppression. However, cover crop productivity is affected by many factors, such as species selection, seeding rates, water availability, soil fertility, planting date, and tolerance to herbicides (Balkcom et al. Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018; Brennan and Boyd Reference Brennan and Boyd2012; Cornelius and Bradley Reference Cornelius and Bradley2017b; Florence et al. Reference Florence, Higley, Drijber, Francis and Lindquist2019; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Lyon, Hergert, Higgins and Holman2015). These adverse conditions can reduce cover crop competitiveness, and, under these circumstances, the presence of a non-injurious fall-applied residual herbicide might be necessary to maintain satisfactory weed control levels.

In general, Italian ryegrass biomass reflected visual estimates of control. For example, at the Clayton location in 2021–22, among cereal rye plots, metribuzin resulted in the highest Italian ryegrass biomass at 94 g m–2, compared with ≤23 g m–2 for all other cereal rye treatments including the No-PRE herbicide treatment (Table 4). At the same location, within crimson clover treatments, pyroxasulfone and S-metolachlor resulted in the lowest Italian ryegrass biomass with 43 g m–2 and 30 g m–2, respectively. Furthermore, throughout the entire study, Italian ryegrass biomass in cereal rye without a herbicide was comparable to that of cereal rye plus pyroxasulfone, S-metolachlor, and flumioxazin. In Salisbury, cereal rye without a herbicide resulted in 13 g m−2 Italian ryegrass, whereas biomass when pyroxasulfone, S-metolachlor, or flumioxazin were used preemergence was 15, 11, and 33 g m−2, respectively, and cereal rye plus metribuzin resulted in 203 g m–2. In 2021-22 at the Clayton site, pyroxasulfone (70 g m–2) or S-metolachlor (78 g m–2) use resulted in the lowest Italian ryegrass biomass among crimson clover plots. Cechin et al. (Reference Cechin, Schmitz, Hencks, Vargas, Agostinetto and Vargas2021) observed that in the first year of cover crop implementation, the planting of cereal rye reduced Italian ryegrass biomass by 65% compared with leaving it nontreated during fallow. By the third year of cereal rye use, the cover crop reduced Italian ryegrass by 97%. The researchers also reported significantly greater Italian ryegrass suppression was obtained by cover crops that produced more than 8,000 kg ha ha–1 of biomass. In a different study, the presence of a cereal rye cover crop reduced Italian ryegrass density by 95% compared with nontreated plots at soybean planting (Reeves Reference Reeves2022).

Italian ryegrass seed production at the Clayton site in 2021–22 was the lowest when grown with cereal rye alone or without an injurious herbicide (741 to 1,356 seeds m–2); up to 98% reduction in Italian ryegrass seed production was achieved by these treatments compared with nontreated plots (31,058 seeds m–2). Similarly, Cechin et al. (Reference Cechin, Schmitz, Hencks, Vargas, Agostinetto and Vargas2021) reported up to 90% reduction in the Italian ryegrass soil seedbank when cereal rye was used as a cover crop. Italian ryegrass seed production when crimson clover had been planted was higher than what was observed in aforementioned cereal rye treatments; however, the number of weed seeds produced within a crimson clover planting without a herbicide (20,428 seeds m–2) was comparable to the number of weed seeds from all crimson clover plus herbicide treatments (13,404 to 27,446 seeds m–2). At Clayton in 2022–23, Italian ryegrass seed production in cereal rye was lower when either metribuzin or pyroxasulfone were used preemergence (2,670 and 1,299 seeds m–2, respectively) when compared with cereal rye without a herbicide (5,600 seeds m–2). These differences were attributed to lower cover crop injury by metribuzin and reduced cereal rye biomass in 2022–23. This highlights the importance of integrated weed management and the need to hedge against unfavorable cover crop growing conditions with a residual herbicide applied at or after cover crop planting. Moreover, even though Italian ryegrass was more prolific at the Salisbury location, with 100,743 seeds m–2 in the nontreated plots, lower seed production was observed from cereal rye plots. Cereal rye without a herbicide reduced Italian ryegrass seed production by 99% (1,396 seeds m–2) and seed production was comparable to that of cereal rye plus pyroxasulfone (4,389 seeds m–2), S-metolachlor (2,053 seeds m–2), and flumioxazin (1,830 seeds m–2). Similarly, within crimson clover plots, Italian ryegrass seed production was lower in the absence of an injurious residual herbicide, which consisted of pyroxasulfone, S-metolachlor, or No-PRE herbicide, ranging from 24,529 to 27,123 seeds m–2. These results highlight the importance of selecting a residual herbicide that effectively controls Italian ryegrass without reducing the cover crop biomass. Safe residual herbicides, if activated, will control Italian ryegrass and enhance early-season cover crop growth, which will maximize late-season cover crop competition with the weed.

Practical Implications

The widespread distribution of multiple herbicide–resistant Italian ryegrass biotypes in North Carolina is alarming (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Taylor and Everman2021). Additionally, the presence of a biotype that is resistant to herbicides in groups 1, 2, 9, and 22 limits postemergence herbicide options. Integrated weed management is crucial to mitigating the evolution and spread of herbicide-resistant weed biotypes. Results from this study highlight the importance of using a diversified approach for Italian ryegrass management by combining fall-applied residual herbicides and cover crops. At both locations in 2021–22, greater control of Italian ryegrass, as well as lower biomass and seed production, were observed where cereal rye was used as a cover crop. Additionally, cereal rye without residual herbicides was as effective in suppressing Italian ryegrass as cereal rye plus a non-injurious herbicide, with up to 5,660 and 7,245 kg ha–1 of biomass produced at the Clayton and Salisbury locations, respectively. However, at Clayton in 2022–23, cereal rye biomass was not as prolific with an average of 2,890 kg ha–1, far below the 5,000 kg ha–1 threshold for ideal weed suppression (Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, Martinez-Feria, Weisberger, Carlson, Basso and Basche2020). Facing less cover crop biomass, the presence of a non-injurious residual herbicide was crucial to maximize Italian ryegrass suppression. Similarly, crimson clover biomass was ≤4,642 kg ha–1 across locations, and greater Italian ryegrass control at 24 WAP was observed when pyroxasulfone or S-metolachlor was applied preemergence to crimson clover. In general, fall-applied residual herbicides alone resulted in adequate Italian ryegrass control at 8 WAP. However, as time progressed, residual herbicide efficacy diminished, and by 24 WAP, Italian ryegrass control was ≤60% by all herbicides. In conclusion, we observed that a diversified weed management approach that uses both a cover crop and a residual herbicide, may reduce Italian ryegrass seed production by as much as 98%. Furthermore, previous research reports that Italian ryegrass seed viability is reduced by ≥95% following 18 mo of burial (Cechin et al. Reference Cechin, Schmitz, Hencks, Vargas, Agostinetto and Vargas2021; Narwal et al. Reference Narwal, Sindel and Jessop2008). The ability of cover crops plus residual herbicides to reduce Italian ryegrass seed production employed over multiple seasons, coupled with the weed’s lack of seed viability after extended burial, may better position growers for managing this troublesome weed in the long term.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided in part by Cotton Incorporated, the North Carolina Cotton Producers Association, the Corn Growers Association of North Carolina, and Syngenta Crop Protection.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.