Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterised by a disturbed body image, the intense fear of gaining weight and an increase in physical activity and decrease in food intake resulting in weight loss. Reference Bozzola, Barni, Marchili, Hellmann, Giudice and De Luca1–Reference Moskowitz and Weiselberg9 The DSM-5 criteria describes two types of anorexia nervosa: the purging type and the restricting type. Reference Harrington, Jimerson, Haxton and Jimerson3 Anorexia nervosa is one of the most frequent forms of eating disorders in young adults, together with bulimia and binge eating disorders. Reference Bozzola, Barni, Marchili, Hellmann, Giudice and De Luca1,Reference Harrington, Jimerson, Haxton and Jimerson3–Reference Silén and Keski-Rahkonen5 According to Belgian studies, 18% of adolescent girls show signs of a disrupted eating pattern and 7% of adolescent boys. Reference Silén and Keski-Rahkonen5,Reference Vanderlinden, Schoevaerts, Simons, Van Den Eede, Bruffaerts and Serra6 Risk factors to develop anorexia nervosa are a family history of eating disorders, a personal history of psychiatric illness or autoimmune disease and a history of functional symptoms. Reference Bozzola, Barni, Marchili, Hellmann, Giudice and De Luca1 A new diagnosis in the DSM-5 and listed under ‘Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders’ is atypical anorexia nervosa. Reference Harrington, Jimerson, Haxton and Jimerson3 ‘All of the criteria for anorexia nervosa are met, except that despite significant weight-loss, the individual’s weight is within or above the normal range.’ 4 Those patients often start as overweight or obese and remain with weight within a healthy range after a trajectory of significant weight loss and a restrictive eating pattern. Reference Walsh, Hagan and Lockwood8–Reference Jhe, Lin, Freizinger and Richmond11 The medical complications in patients with atypical anorexia nervosa are as severe or even more severe than in typical anorexia nervosa. Reference Vo and Golden10,Reference Garber, Cheng, Accurso, Adams, Buckelew and Kapphahn12,Reference Sawyer, Whitelaw, Le Grange, Yeo and Hughes13 Patients with atypical anorexia nervosa are commonly missed or underdiagnosed due to a normal body mass index (BMI). Reference Vo and Golden10,Reference Garber, Cheng, Accurso, Adams, Buckelew and Kapphahn12 According to Garber et al the percentage and rate of weight loss is a significant predictor for risk of complications, rather than weight at admission. Reference Garber, Cheng, Accurso, Adams, Buckelew and Kapphahn12 Sawyer et al reported that patients with atypical anorexia nervosa have a more severe psychopathology on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. Reference Sawyer, Whitelaw, Le Grange, Yeo and Hughes13 Complications of eating disorders are related to the catabolic state of starvation. Tissue breaks down to supply energy and it affects every body system. Reference Sachs, Harnke, Mehler and Krantz14–Reference Stheneur, Bergeron and Lapeyraque18 Myocardial atrophy results in reduced cardial mass, reduced cardiac chamber volumes, mitral valve prolapse and myocardial fibrosis which leads to reduced cardiac output and lower blood pressure. Symptoms occur when the patient is below 80% of their ideal body weight. Patients may experience chest pain or palpitations and reduced exercise capacity. Pericardial effusion may appear in patients with anorexia nervosa but it is mostly asymptomatic without clinical murmur or cardiac tamponade. Reference Garber, Cheng, Accurso, Adams, Buckelew and Kapphahn12,Reference Sachs, Harnke, Mehler and Krantz14,Reference Mehler, Yager and Solomon15

GLP-1-receptor agonists

Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. GLP-1 is an incretin hormone secreted after intake of carbohydrates and fats. It binds to receptors on the pancreatic beta cell membrane to stimulate exocytosis of insulin granules and inhibits secretion of glucagon. Reference Sorli, Harashima, Tsoukas, Unger, Karsbøl and Hansen19–Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24 It improves the glycaemic control with a low risk of hypoglycaemia. Reference Sorli, Harashima, Tsoukas, Unger, Karsbøl and Hansen19–Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24 An additional effect of the GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) is reduction of appetite and energy intake with a reduction in body weight. GLP-1 crosses the blood brain barrier to bind to receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) in the medulla. Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24 The NST projects neurons to food-regulating areas in the brain and it communicates with intestinal vagal neurons. The vagal nerve induces gastroparesis and it delays gastric emptying which leads to feelings of nausea and satiation. Reference Sorli, Harashima, Tsoukas, Unger, Karsbøl and Hansen19–Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24 Semaglutide is indicated for patients with diabetes type 2 who are obese or overweight or patients with the metabolic syndrome. Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24 The European Medicines Agency has approved the use of ‘semaglutide (Wegovy®) in adolescents as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for weight management in adolescents aged 12 years and above with a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for their age and gender and body weight above 60 kg’. 25 Studies show a promising role of GLP-1 RA in the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents with similar safety and efficacy as in adults. Reference Kavarian, Mosher and Abu El Haija24

Case presentation

The consent of the patient and her mother were verbally obtained and written down in her medical file. Institutional ethics approval was not necessary given the descriptive character of the case report.

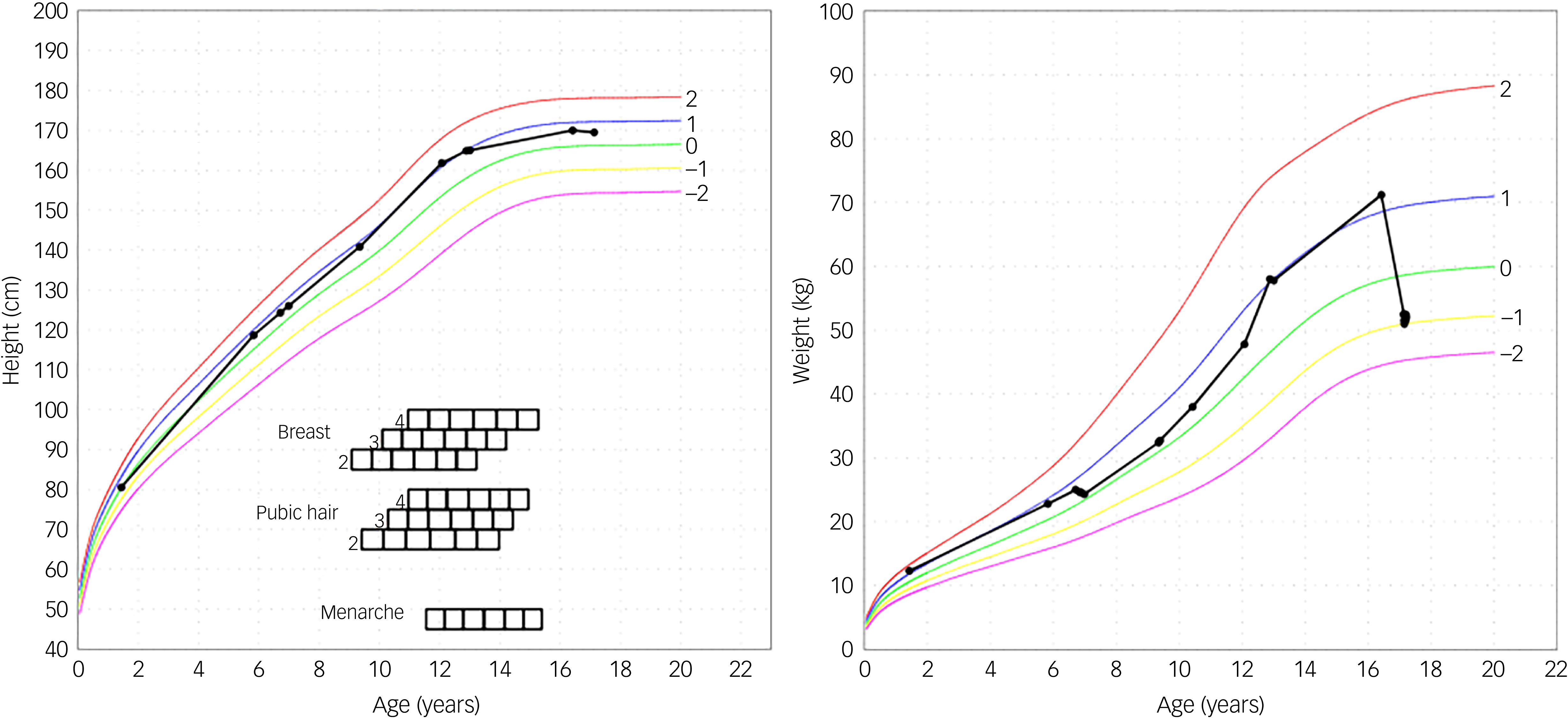

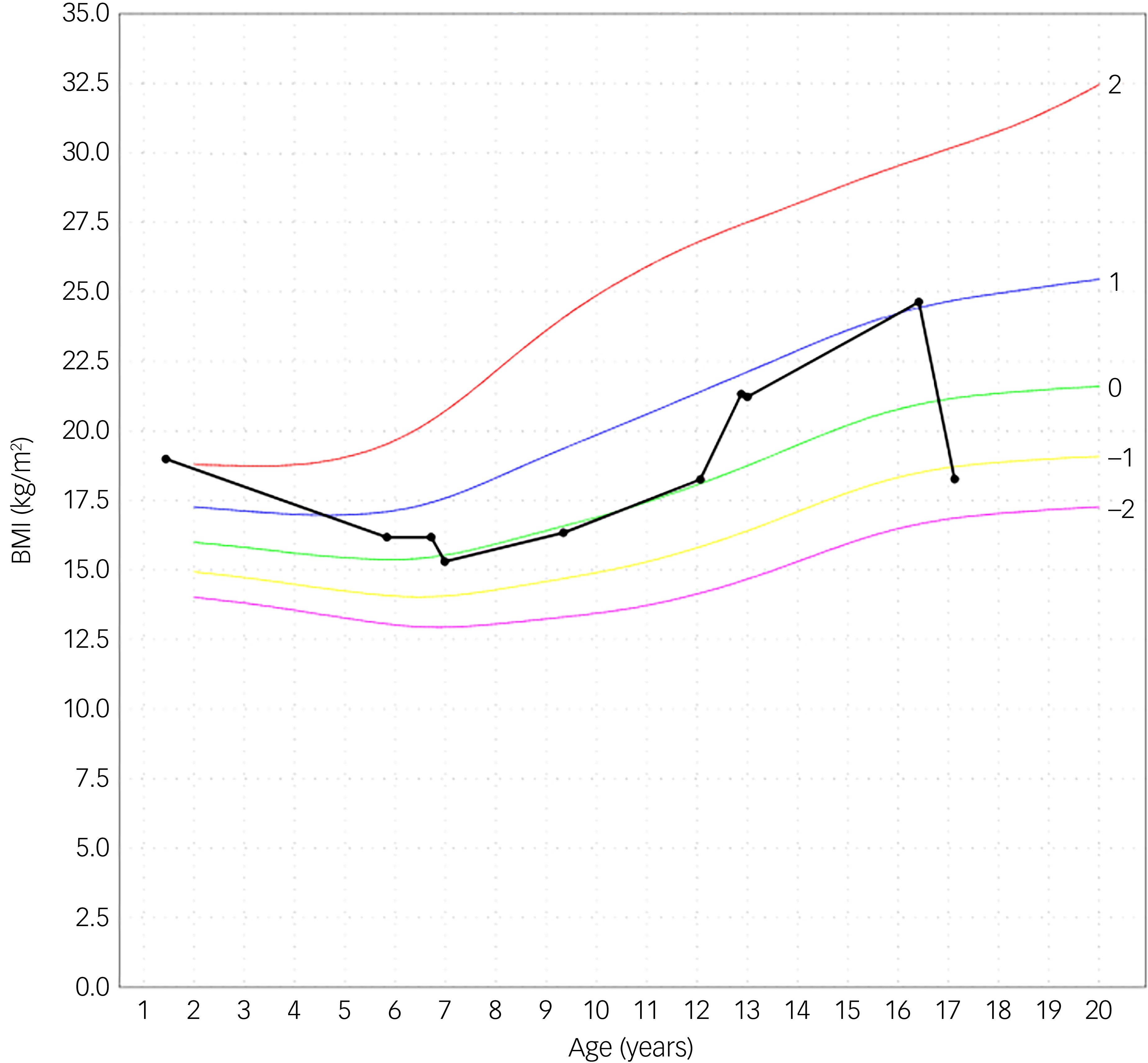

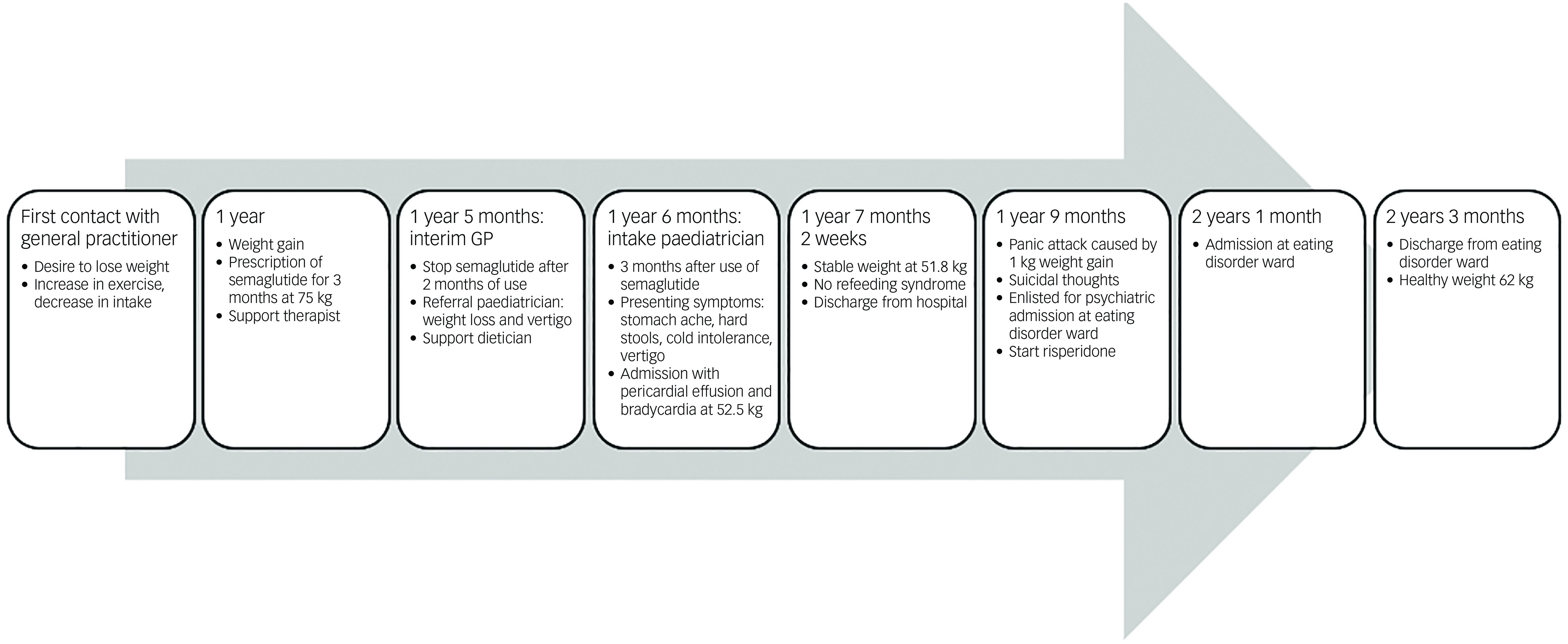

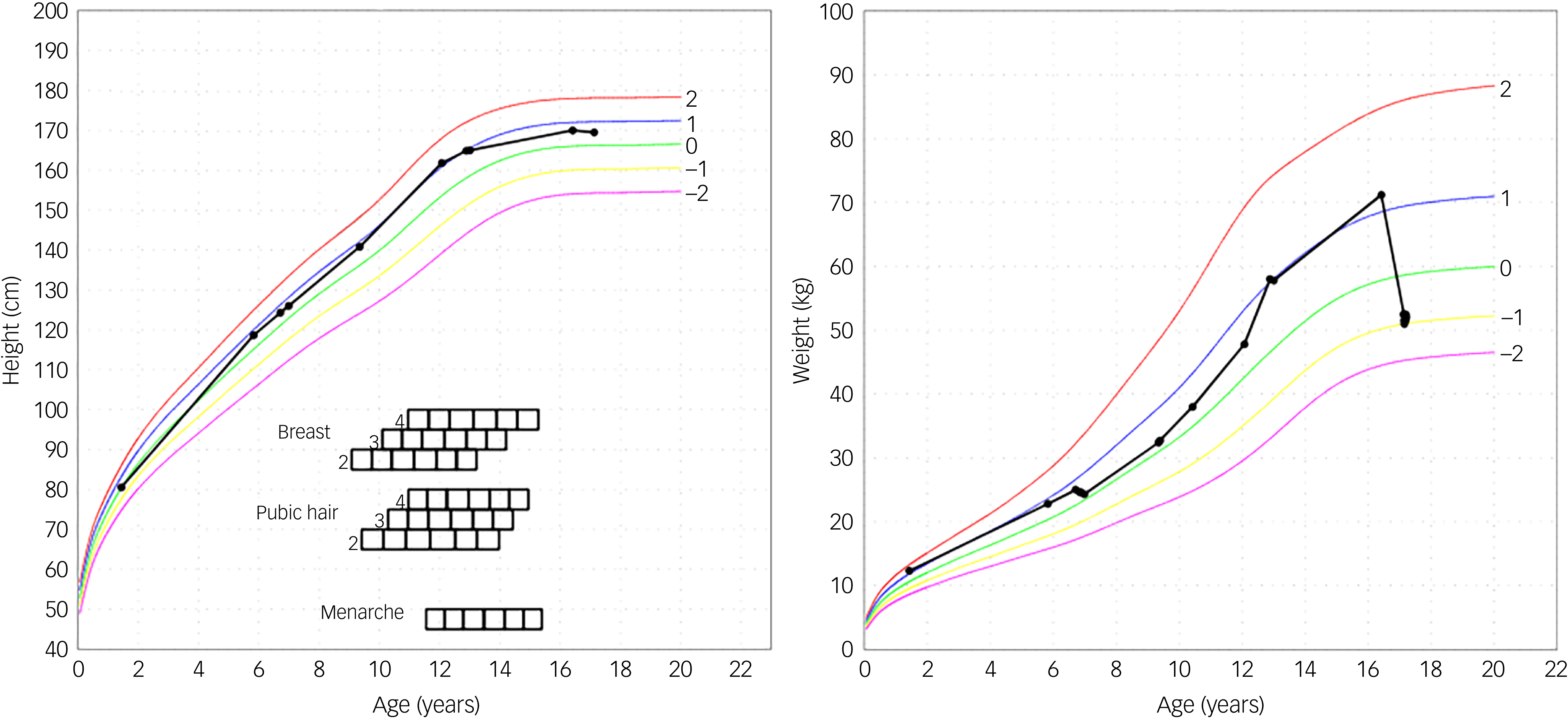

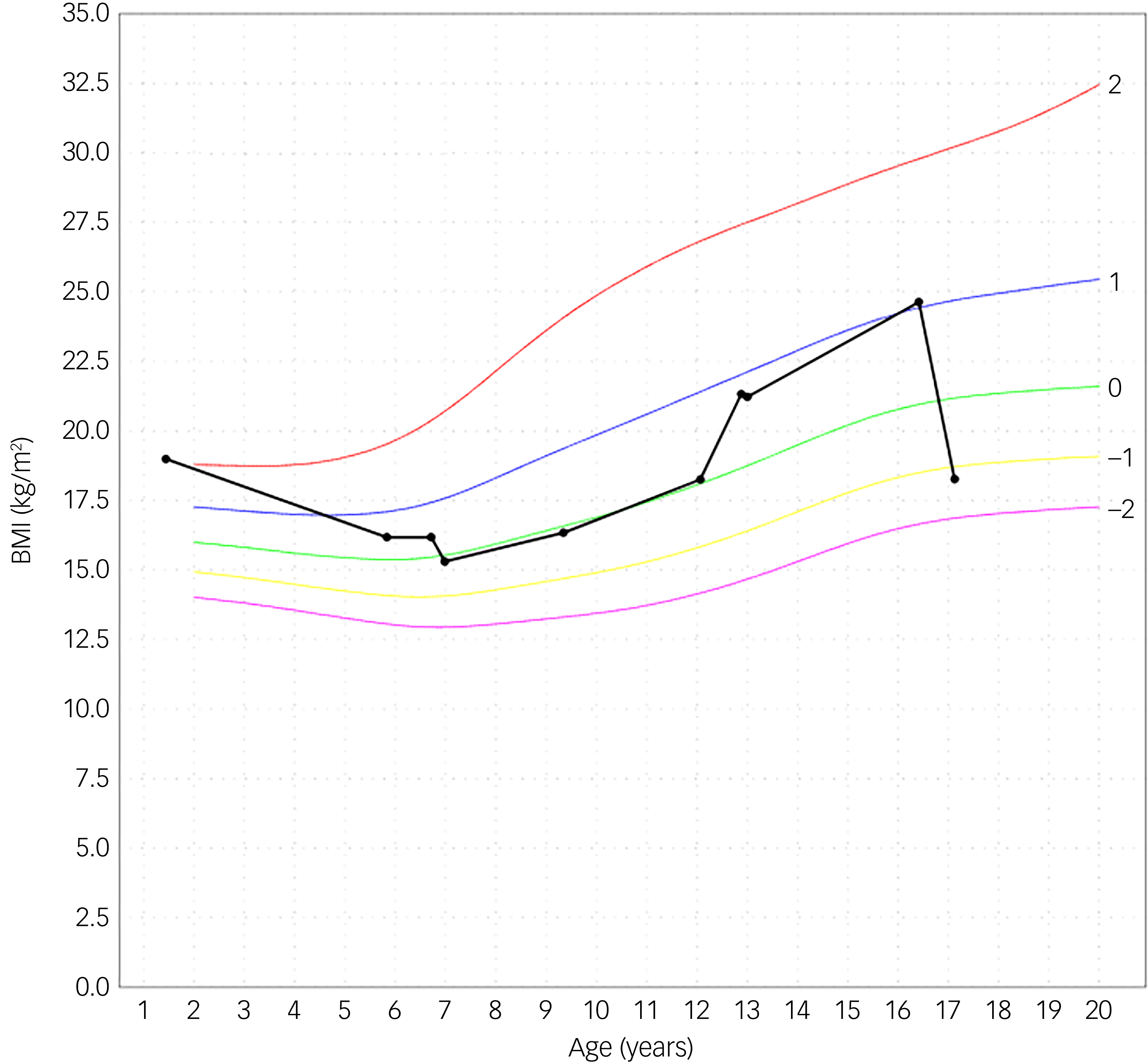

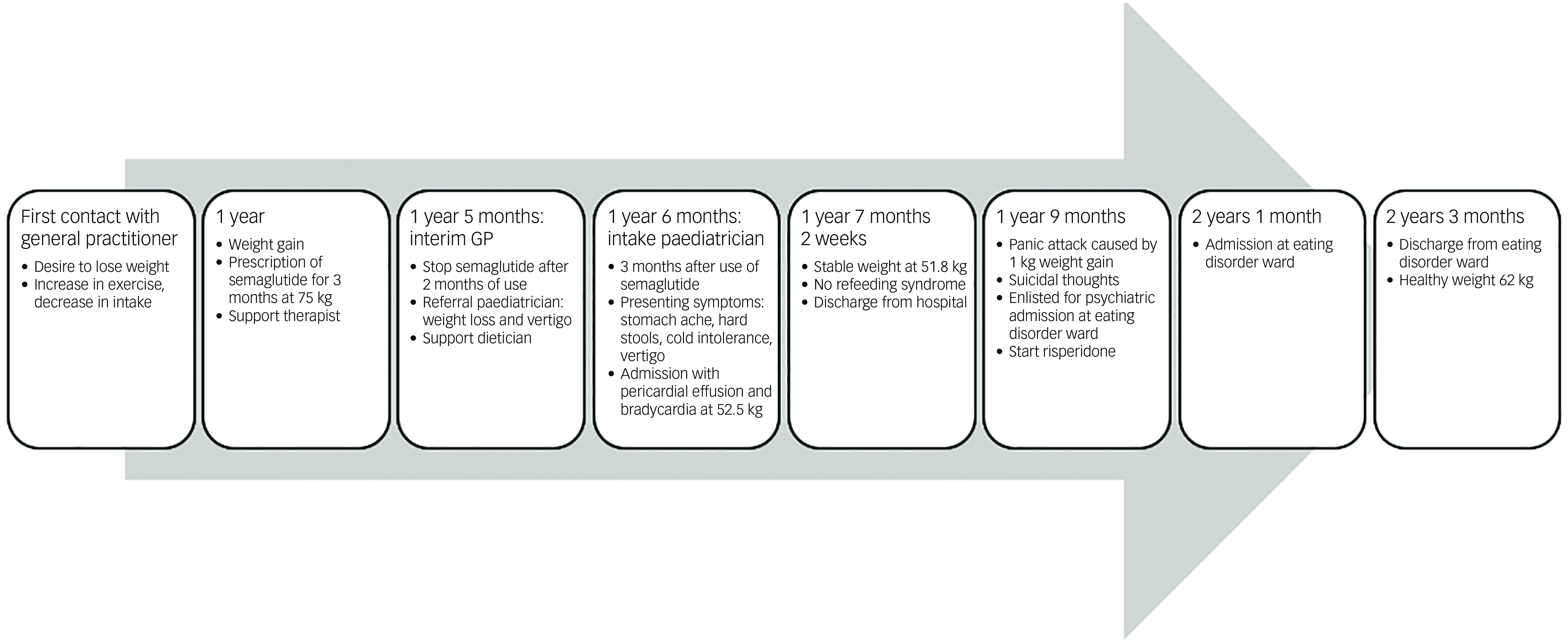

An adolescent girl presented with a history of increase in exercise and decrease in food intake for the past 18 months. She wanted to lose weight, had a distorted self-image and struggled to eat. The adolescent denied having binge eating or purging episodes. Presenting symptoms were stomach ache, hard stools and bowel movement difficulties. She suffered cold intolerance and experienced frequent episodes of vertigo without syncope or thoracic pain. Support was already provided by a therapist and dietician. The adolescent girl was previously in follow-up with her general practitioner (GP), who was now on maternity leave. After 2 months the interim referred her to the paediatrician by reason of weight loss and vertigo. An ultrasound of the heart showed pericardial effusion with bradycardia until 38 bpm which led to hospital admission. During her hospital stay she admitted she had used semaglutide. In a period of 3 months, she injected herself with 0.25 mg semaglutide prescribed by her GP after weight gain until 75 kg. Her weight start point was 72 kg with a BMI of 24.6 kg/m2. She lost approximately 20 kg over a period of 6 months. At her intake consultation she weighed 52.5 kg for a body length of 169.5 cm, as shown in Fig. 1. Her BMI was calculated at 18.2 kg/m2; this index was on the high end of underweight, as shown in Fig. 2. Her lab results at admission were normal. The mental problems, disturbed body image and her fear of gaining weight led to the diagnosis of atypical anorexia nervosa. During her hospital stay, a nutrition plan with increasing caloric intake was devised by the dietician. Her weight and blood results were monitored every 2 days with follow-up of the electrolytes to avoid refeeding syndrome. At day 3 of her hospital stay her lab results showed low potassium, calcium and bicarbonate without clinical symptoms. During admission the patient was supported by the psychologists of our team. She struggled with the hospital stay, as she had no insight into her illness because she said she did feel well. She was psychiatrically stable. When she was discharged, her weight stabilised at around 51.8 kg. The course of disease progression is depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 1 Height and weight curve. The black curved line is the personal growth data from the patient. The other curves are from reference data. Reference Roelants, Hauspie and Hoppenbrouwers26

Fig. 2 Body mass index (BMI). The black curved line is the personal growth data from the patient. The other curves are from reference data. Reference Roelants, Hauspie and Hoppenbrouwers26

Fig. 3 Timeline.

Outcome and follow-up

After discharge the girl had follow up appointments with the paediatrician. Exercise was reintegrated into her daily life and she went back to school.

After a hospital stay of 6 weeks she gained 1 kg, which caused a panic attack. She ran away from home. Later, she presented at the emergency department with suicidal thoughts. Risperidone was prescribed by the psychiatrist to counter her anxiety. Support from the crisis team was activated. The adolescent signed up to the waiting list for a psychiatric admission at an eating disorder ward. Four months after her panic attack, she was admitted for 8 weeks where she was counselled and supported by a specialised team of physicians, psychiatrists, therapists and dieticians. She is currently back to a healthy weight. To our knowledge, this was her first episode of a psychiatric crisis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this may be the first case report of semaglutide misuse in an adolescent girl. Guerdjikova et al published a scientific report of an adult woman with a history of atypical anorexia nervosa and multiple psychiatric disorders who misused semaglutide. Reference Guerdjikova, Ward, Ontiveros and McElroy27 Another case report was published concerning misuse of topiramate by an adolescent girl. Reference Kakunje, Mithur, Shihabuddeen, Puthran and Shetty28 The use of semaglutide was recently promoted by influencers and celebrities as an easy and safe way to lose weight, even without the diagnosis of diabetes or obesity. This led to a worldwide shortage of the drug for patients with diabetes type 2. Semaglutide has a possible impact on mental health, triggering depression and suicidal thoughts in patients who are prone to mental disorders. Reference Chiappini, Vickers-Smith, Harris, Papanti Pelletier, Corkery and Guirguis29,Reference Arillotta, Floresta, Guirguis, Corkery, Catalani and Martinotti30 Chen et al Reference Chen, Cai, Zou and Fu31 conducted an observational pharmacovigilance study; an association and a correlation between GLP-1 receptor agonists and psychiatric adverse effects were found. A proposed explanation for the association might be a pre-existing psychiatric disorder or a prone personality. Reference Chen, Cai, Zou and Fu31 However the exact mechanism remains unclear. Reference Chen, Cai, Zou and Fu31 According to Griffiths et al, Reference Griffiths, Harris, Whitehead, Angelopoulos, Stone and Grey32 social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram might exacerbate eating disorder symptoms by showing personalised content about diet, exercise and toxic eating habits.

Other complications related to atypical anorexia nervosa are impaired renal function, skin manifestations and abdominal complaints. Skin manifestations include xerosis, telogen effluvium, lanugo hair, nail fragility and acrocyanosis. Thrombocytopenia leads to purpura and bruising. Reference Mehler, Yager and Solomon15,Reference Gibson, Workman and Mehler16 Gastroparesis results in bloating, abdominal discomfort, nausea and constipation. Reference Garber, Cheng, Accurso, Adams, Buckelew and Kapphahn12,Reference Mehler, Yager and Solomon15–Reference Norris, Harrison, Isserlin, Robinson, Feder and Sampson17 Hypoelectrolytic disorder with hypokalaemia, hyponatraemia, hypomagnesaemia and hypophosphataemia caused by dehydration or vomiting can lead to nephropathy and renal failure. Reference Mehler, Yager and Solomon15,Reference Gibson, Workman and Mehler16,Reference Stheneur, Bergeron and Lapeyraque18 Other complications include osteoporosis, amenorrhoea and delayed wound healing. Reference Mehler, Yager and Solomon15,Reference Gibson, Workman and Mehler16

Our patient lost approximately 20 kg in 6 months, similar to the patient of Guerdjikova et al, Reference Guerdjikova, Ward, Ontiveros and McElroy27 which was more weight than the average weight loss reported in clinical trials of semaglutide. Reference Sorli, Harashima, Tsoukas, Unger, Karsbøl and Hansen19–25 This may be attributed to the combined pharmacological and psychopathological effect of semaglutide and anorexia nervosa, respectively. The girl had the psychogenic traits for anorexia nervosa and semaglutide facilitated the weight loss, even after ceasing the medication. For her self-proclaimed weight problems and disturbed body image our patient frequently visited her GP. The GP prescribed her the medication and treated her for being overweight. After 3 months the girl stopped using semaglutide; however, she kept losing weight caused by an increase in exercise and decrease in caloric intake. After several months, the girl was referred by an interim GP to the paediatrician due to her physical complaints.

According to the 2023 guidelines update of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP), there are no clear pharmacological recommendations for children and adolescents with eating disorders. Because of the lack of pharmacological studies of eating disorders in adolescents, and in atypical anorexia nervosa in particular, the WFSBP didn’t cover this topic. Reference Himmerich, Lewis, Conti, Mutwalli, Karwautz and Sjögren33

Atypical anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder similar to anorexia nervosa, except the patient has a BMI within normal limits. The risk of serious complications is related to the amount of weight loss, not to the absolute weight.

Semaglutide is a drug for patients with diabetes type 2 and obesity. It improves glycaemic control and it induces weight loss. The drug can affect mental health in patients who are prone to mental disorders.

Vigilance in prescribing GLP-1 receptor agonists is warranted. Semaglutide can be beneficial in patients with obesity and diabetes with strict medical and psychological follow-up, especially in adolescents.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

The original manuscript was written by L.L. and reviewed and edited by K.K. and E.F.E. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.