Durante el período Clásico Tardío (600–900 d.C.), los monumentos pétreos del Occidente de las Tierras Bajas mayas registraron individuos con el apelativo sajal de forma recurrente, cargo asociado con líderes de grupos corporativos que fungieron como gobernadores de sitios secundarios y supervisaron actividades relacionadas con la guerra, así como la producción y distribución de bienes. El aumento de registros, así como la elaboración de monumentos por parte de este sector con narrativas diferentes y que compiten con las de los gobernantes, se ha ligado con uno de los factores que produjo la crisis del sistema político regional y que culminaría en el abandono de las capitales en el siglo IX d.C. De esta manera, el presente artículo tiene como objetivo analizar los monumentos de las esferas políticas de Yaxchilán, Piedras Negras y Palenque para identificar las estrategias discursivas utilizadas por los sajales para mostrar y fortalecer su jerarquía política. Para lograr esto, analizaré el discurso en relación con la intermedialidad de los monumentos para examinar cómo rivalizaban con los gobernantes de estas capitales. Además, exploraré la correlación entre los discursos y las transformaciones sociopolíticas que precedieron al colapso regional.

In the eighth century, political instability and conflict were prevalent in several states in the central Maya Lowlands. Hieroglyphic records from this period indicate a rise in references to the roles and titles held by secondary nobles, also referred to as intermediate elites (Elson and Covey Reference Elson and Alan Covey2006; Walden et al. Reference Walden, Ebert, Hoggarth, Montgomery and Awe2019). These references reflect the involvement of multiple actors who were intermediaries between rulers and commoners, fulfilling a wide range of responsibilities, including those of a priestly, administrative, artistic, and political nature (Beliaev Reference Beliaev, Graña-Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagner2004; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Arlen1992; Coe Reference Coe1997; Foias Reference Foias2013; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008; Martin Reference Martin2020; Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004; Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Camacho, Valenzuela, Kotegawa and Olguín2015; Zender Reference Zender2004). According to some experts, the growth of these elites and their competition with rulers led to changes in political structure, which may have caused the political system to fragment and collapse a few decades later (Aimers Reference Aimers2007:331; Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992:47–48; Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Rice, Rice, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004:3; Fash et al. Reference Fash, Wyllys Andrews, Kam Manahan, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004:285; Golden Reference Golden2010:373; Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2013b:416; Liendo Stuardo Reference Liendo Stuardo and Stuardo2011:78; Martin Reference Martin2020:318; Schele Reference Schele and Patrick Culbert1991:78; Schele and Mathews Reference Schele, Mathews and Patrick Culbert1991:250–251; Scherer and Golden Reference Scherer, Golden and Iannone2014:220; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Eeckhout and Le Fort2005:37).

One of the most frequent titles in stone monuments related to intermediate elites is sajal, particularly at sites such as Palenque, Pomona, Tonina, Piedras Negras, and Yaxchilan in the Western Maya Lowlands (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Stuart Reference Stuart2013). The sajals were corporate group leaders who resided in capitals and surrounding areas. They sometimes served as governors of secondary sites and supervised activities related to warfare, as well as the manufacturing and distribution of goods (Foias Reference Foias2013:117, 127; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Schroder, Vella, Recinos, Masson, Freidel, Demarest, Chase and Chase2020; Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009:175; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001:61; Jackson Reference Jackson2013:12; Martin Reference Martin2020:88; Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2021:99–100; Schele Reference Schele and Patrick Culbert1991:7; Schroder et al. Reference Schroder, Golden, Scherer, Álvarez, Dobereiner and Cab2017; Stuart Reference Stuart2013). Their monuments, with similar and contrasting narratives to those of the k'uhul ajaw, reflect their political context and intentions, making them valuable in understanding sociopolitical changes in the area during the Late Classic period (a.d. 600–900).

This article aims to analyze the monuments of the political spheres of Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque to identify the discursive strategies used by sajals to showcase and strengthen their hierarchical and political positions. To accomplish this, I will analyze the discourse of the sajals' monuments to examine how they rivaled the rulers of these cities. Additionally, I will explore the correlation between these discourses and the sociopolitical transformations that preceded the regional collapse in the ninth century.

Exploring Maya monuments as a political discourse

Discourse is a product of a complex communicative system that incorporates culturally meaningful symbolic expressions. These expressions are shaped by individuals' or groups' ideologies, context, and interests that control their production and circulation (Haidar Reference Haidar2006:73–74; Pardo Abril and Hernández Vargas Reference Abril and Graciela2006:24; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:467). Discourse can be political in nature depending on how it is expressed and what its purpose is. This happens when the primary objective of a message is to establish and expose the power of an individual or a group to provide legitimacy, unite society, convey a political ideology, create identity, and, in the case of text-based discourse, share ideas in a permanent way (Fuentes Reference Fuentes Rodríguez and Rodríguez2016:20; Silverstein and Urban Reference Silverstein, Urban, Silverstein and Urban1996:2; Swartz et al. Reference Swartz, Turner and Tuden1966:6; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk, Caldas-Coulthard and Coulthard2003, Reference Van Dijk2008).

According to Teun A. Van Dijk (Reference Van Dijk2008:9, Reference Van Dijk, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:469), political discourse plays a crucial role in social control. Specifically, when a particular group controls a discourse, it dictates what is communicated, by whom, how, when, and where. Ultimately, this practice influences the ideology and behavior of others in a targeted manner (Chiriac Reference Chiriac2019:56; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk2008:9, Reference Van Dijk, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:466). To maintain their existing privileges and governance, those in power manipulate language (both verbal and nonverbal), timing, and rhythm to convey their preferred ideas (Hanks Reference Hanks1996:230; Küküçali Reference Küküçali2015:58; Wilson Reference Wilson, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:777).

To better understand discourse, we can analyze its three stages: production, circulation, and reception. The production stage examines discourse producers, their institutions, and the circumstances of discourse production. During the circulation phase, we can discuss the communicative channels used to issue the discourse, such as materiality, spatial location, and the content of the message. Finally, the reception stage shows how the audience perceives information and the social actions generated by it (Haidar Reference Haidar2006; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015).

There are several approaches to discourse analysis that are closely linked to the stages mentioned above. One such approach is to examine the cognitive dimension of the agents involved in the production and reception phases to understand how they encode messages. A sociocultural perspective can help one understand the social and political context in which discourse circulates. In addition, a linguistic dimension can be explored, which encompasses the structure, content, morphology, syntax, and semantics of the message (Pardo Abril and Hernández Vargas Reference Abril and Graciela2006:27). Discourse analysis offers numerous possibilities, and its methodology can be tailored to suit a particular case study. By acknowledging that discourse reflects and constructs reality simultaneously, discursive analysis can provide an understanding of social and political groups within their societal contexts (Gee Reference Gee1999:82; Haidar Reference Haidar2006:79; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:467).

Ancient Maya elites produced multiple discourses through verbal and paralinguistic communication forms in architecture, painting, hieroglyphic texts, images, sculpture, and more. Among these, stone monuments were instruments for delivering discourses with different purposes, functioning as devices of collective memory that produced and reproduced sociocultural changes. Monuments had numerous formats, such as steps, stelae, lintels, altars, and benches; each constituted a discursive unit. Combined in the same space with other units, they create discursive complexes that convey messages at various levels and serve multiple purposes (Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2022:62).

Maya stone monuments present three characteristics that must be contemplated during discourse analysis. The first is “multimodality,” which refers to applying multiple communication channels to transmit messages verbally with words and signs or nonverbally through sounds, smells, images, and colors (Bannerman Reference Bannerman2014:67; Key Reference Key1975:23). Although it does not occur in all cases, most Maya monuments include hieroglyphic texts and images. Both elements interact with and complement each other to generate a more specific message; this quality is called “intermediality” (Berlo Reference Berlo and Berlo1983:10; Leeuwen Reference Leeuwen2015:481; Salazar Reference Salazar Lama2019:24). The intermediality between text and image is relative, given that both can function independently but generally work together to help diverse audiences understand the intended meaning (Berlo Reference Berlo and Berlo1983:11; Burdick Reference Burdick2010:66; Marcus Reference Marcus, Chase and Chase1992:228; Salazar and Valencia Reference Salazar Lama and Rivera2017:95).

The third characteristic is “intertextuality,” which refers to the monuments' interactions with the surrounding landscape. Maya discursive units are not isolated; instead, they are connected to nearby buildings, other monuments, and landscape elements (Kupprat Reference Kupprat, Kettunen, Helmke, Saurwein and Schwaben2015:37). The placement and intertextuality of monuments significantly affect their ability to communicate messages. For instance, a monument is considered public when it is in an open area with accessibility for many individuals, so it contains messages that the majority can easily understand. Conversely, a monument is considered private if stairs and narrow entrances restrict access or if it is located inside a building, which can limit the message to only a few people who, due to their status or specialization, can decipher the specific content (O'Neil Reference O'Neil2012; Parmington Reference Parmington2011:20, 33). By considering the intertextuality of monuments and analyzing them as part of discursive complexes, we can potentially uncover more intricate meanings; this could help scholars understand the producers’ intentions and the viewers’ possible experiences, even if only hypothetically.

In this article, I will use the data obtained in a more extensive previous study for which I analyzed 151 monuments from the Late Classic political spheres of Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque (Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2022). The selected monuments reflect the roles of intermediate elites and their interactions with rulers. This approach aims to compare discourses from various political segments and understand their relationships within the context of monument production.

The analysis considered multimodality, intertextuality, and intermediality of the discursive complexes of these sites (when the data allowed it) and examined the composition and content of the messages. Composition refers to the study of elemental features of discourse, such as the format and dimensions of monuments; the intertextuality from which the accessibility, visualization, and interaction of the monument with its surroundings are analyzed; and temporality and iconographic composition. Regarding content, I reviewed the narrative structure of discourses, the actions and agents involved, rhetorical figures, titles, and the meanings of messages in texts and images, mainly from a sociocultural perspective. The details of the analysis and the complete epigraphic readings can be consulted in the appendixes of that investigation (Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2022).

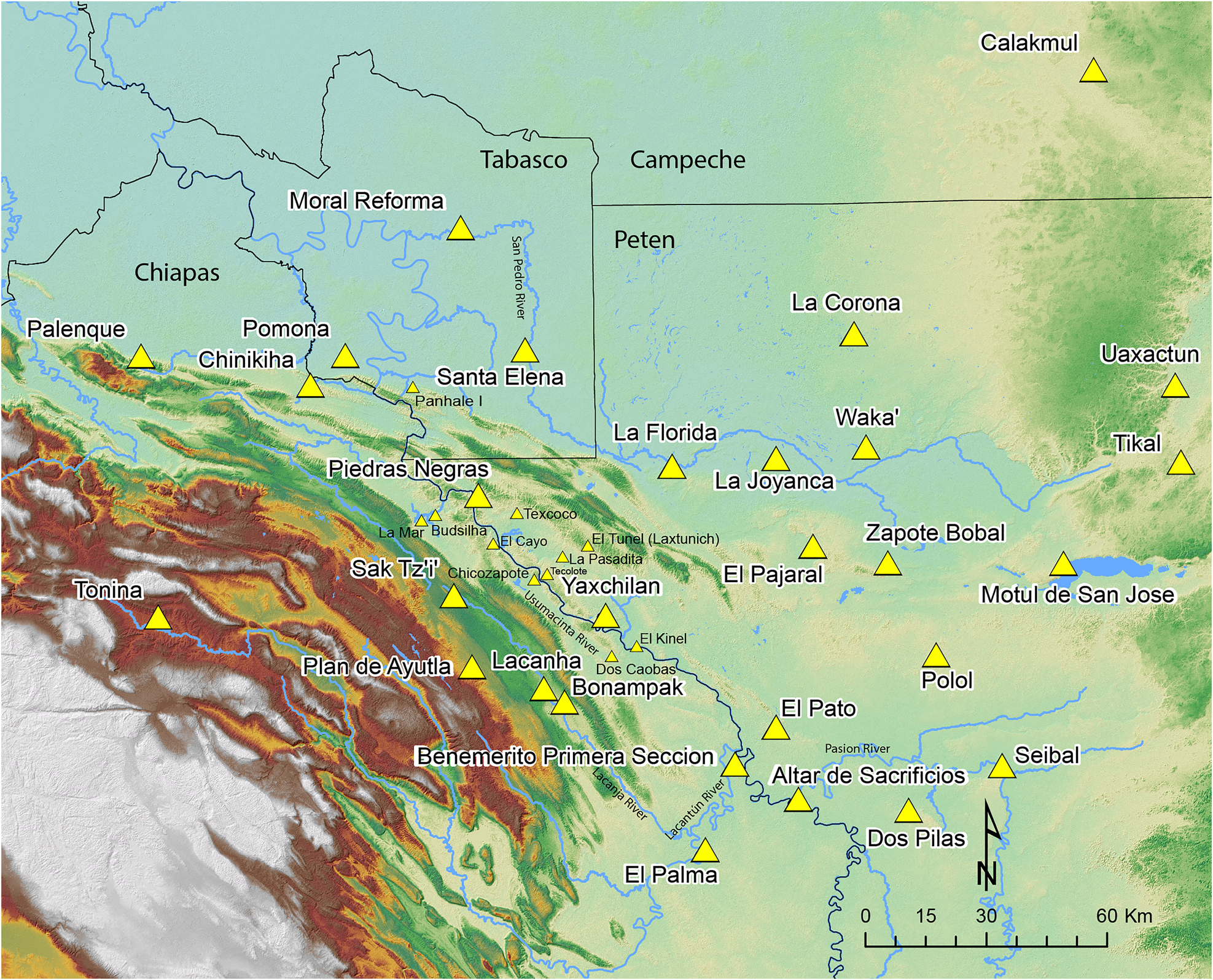

This article will only focus on discourses of sajals in Palenque, Piedras Negras, and Yaxchilan, as well as peripherical sites, such as Dos Caobas, Site R, La Pasadita, Laxtunich, El Cayo, La Mar, and Miraflores (Figure 1). I consider various aspects of my previous analysis (see Anonymous), including iconographic compositions and the content of hieroglyphic texts from the production and circulation stages of discourses. It is essential to mention that the reception stage is not included here, given that many of the monuments of these officials were extracted from their original contexts, making it challenging to complete the analysis at the intertextuality level due to limited information. However, it should be noted that most of the monuments consist of lintels, which were placed in the access openings of the buildings. As a result, the content of these discursive units is private and specialized, intended for a more limited audience. I use sajals' data for comparison with the discourses issued by the k'uhul ajaw. This enables me to detect changes and continuities in discursive messages and their relationships with the sociopolitical context.

Figure 1. Map of the western Maya Lowlands, with the locations of Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Palenque, and their surrounding sites. Courtesy of Charles Golden.

Discursive salience: The k'uhul ajaw and his hierarchy

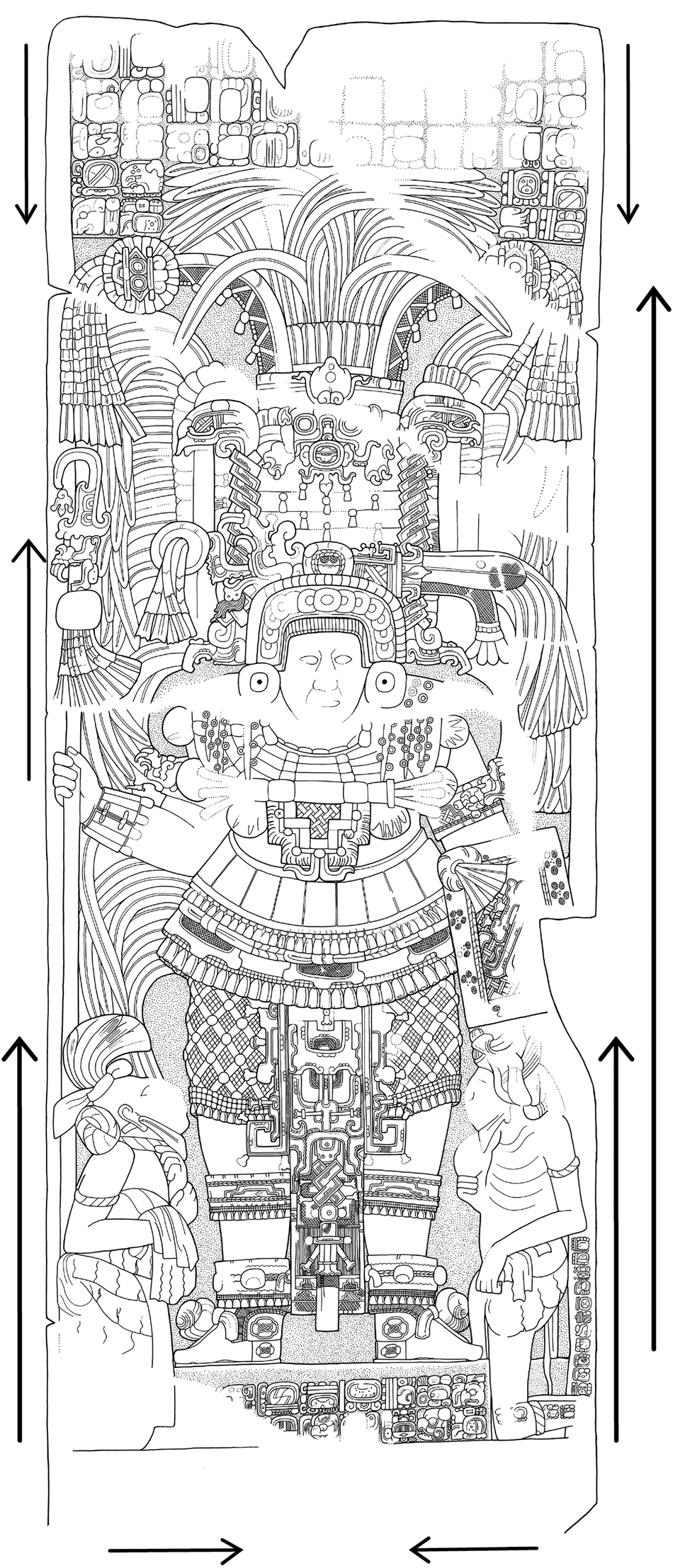

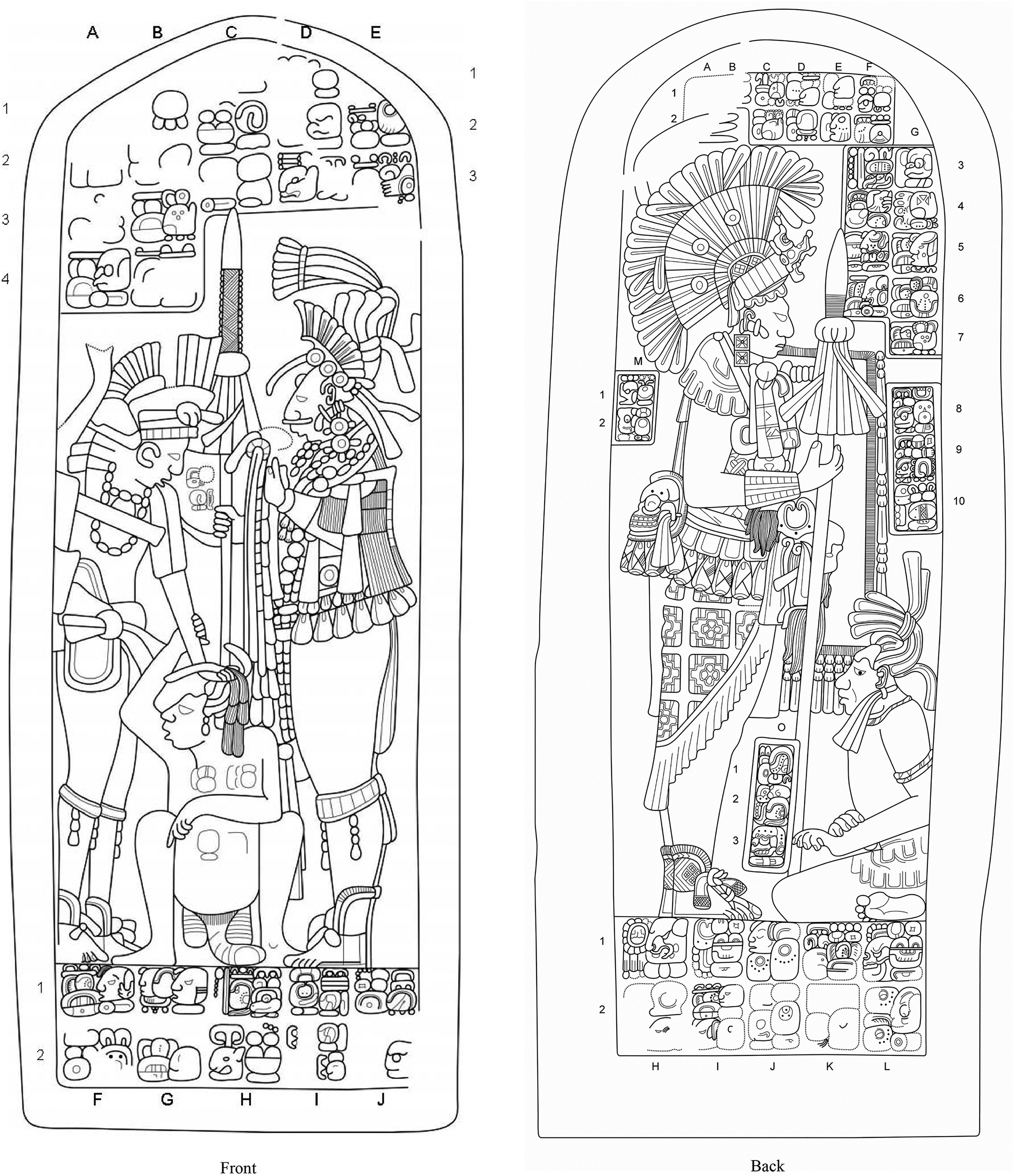

Over time, artists developed standardized structures and styles in Maya monuments, resulting in discursive conventions during the production stage. Some of these patterns are related to relevant elements of discourse, which received special treatment to facilitate their identification by the audience; this is referred to as salience or discursive focus. At the iconographic level, the compositions present organized elements whose structural and rhythmic relationship establishes visual hierarchies (Salazar Lama Reference Salazar Lama2019:82). Maya artists used various techniques to create visual hierarchy, such as representing characters individually; depicting figures in oversized proportions; positioning elements vertically, frontally, and centrally in the composition; placing motifs on the right side of the pictorial space; using relief; and employing tension vectors to emphasize particular objects over others (Arnheim Reference Arnheim1982:2; Joyce Reference Joyce2000:71; Palka Reference Palka2002:421, 428; Parmington Reference Parmington2003:51; Salazar Lama Reference Salazar Lama2019:95–96) (Figure 2). The tension vectors help guide the viewer's gaze, allowing the artist to place the most important elements within that space. These vectors can be eccentric (directed outward) or concentric (leading toward the center of the composition). It is important to consider that vectors organize the analysis of monuments and are in accordance with Maya discursive conventions.

Figure 2. Tension vectors show the visual hierarchy in the K'ihnich Yo'nal Ahk II figure at Stela 8, Piedras Negras. Front: drawing by David Stuart © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.19.23.

Maya iconographic compositions during the Classic period emphasized the presence of the k'uhul ajaw, who was given specific attributes to enhance his hierarchy―visual and political―and distinguish him from other elite members (Marcus Reference Marcus, Elson and Alan Covey2006:217; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García2009:261–262). Hieroglyphic texts frequently mentioned the k'uhul ajaw through biographical data or actions such as rituals, wars, and prisoner captures. Several times within the texts, the ruler's name was recorded to assign importance through larger hieroglyphic cartouches that reinforced his hierarchy in discourse. This hierarchy is associated with registering various titles related to his sacred power, lineage, and religious and warlike aspects.

The titles of rulers vary depending on regional styles and sociopolitical context, and they are used to strengthen specific aspects of their power. For example, the Late Classic–period rulers of Yaxchilan used long lists of titles, unlike Piedras Negras and Palenque kings. All three sites use the same titles related to the ruling lineages (emblem glyphs), the count of katuns, and honorific ones such as ch'aho'm, baahkab, and kalo'mte' (Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2022:145–146, 209–211, 281–284).

The conventions highlighting rulers as a discursive focus remained consistent throughout the Classic period. However, in the seventh century, sajals began using conventions previously reserved for the k'uhul ajaw in order to display their position in the political hierarchy in discourse. I will explain how these changes reflect sociopolitical transformations at the discursive level during the Late Classic period, when the competition between rulers and sajals may have increased.

The discourse of sajals

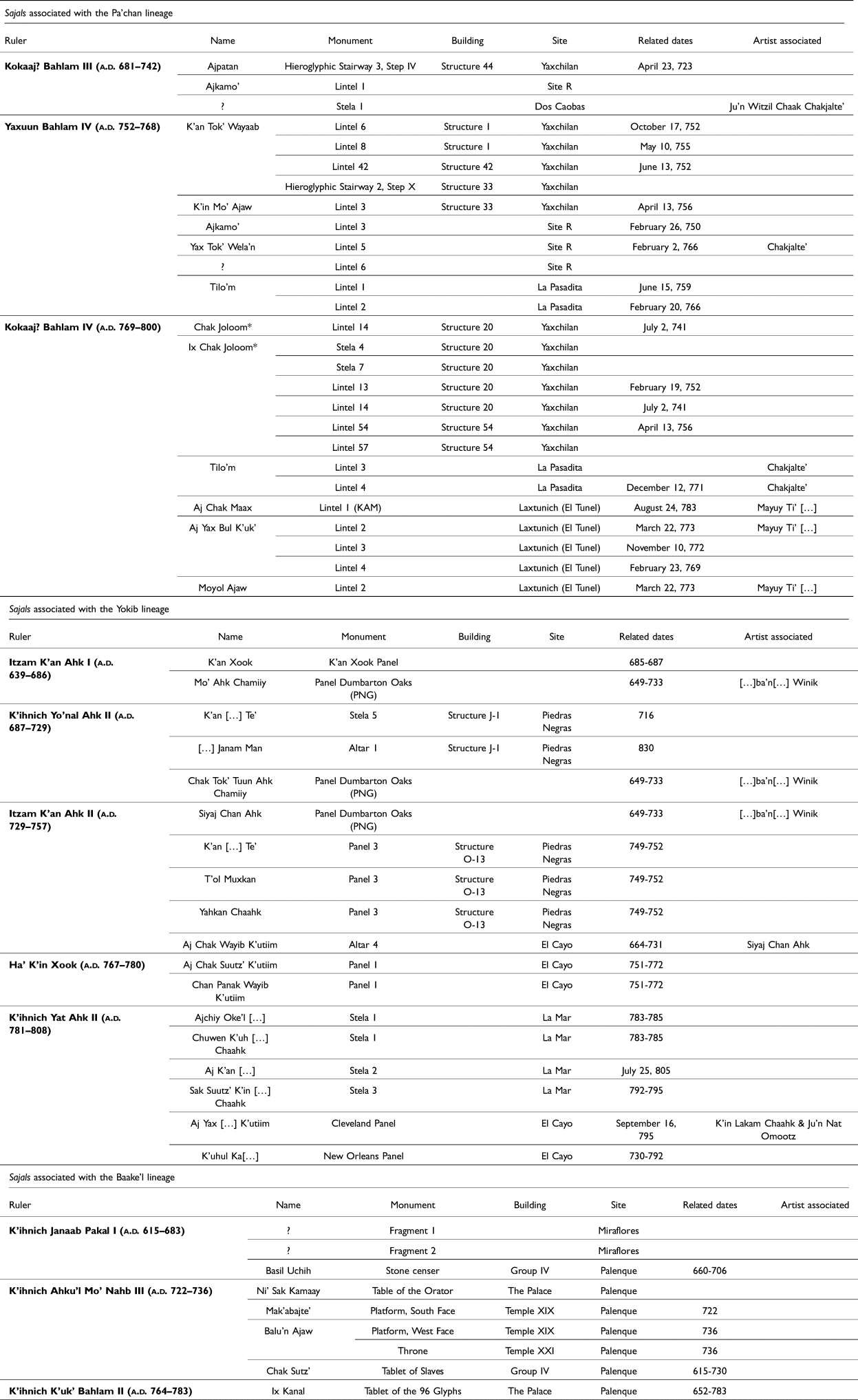

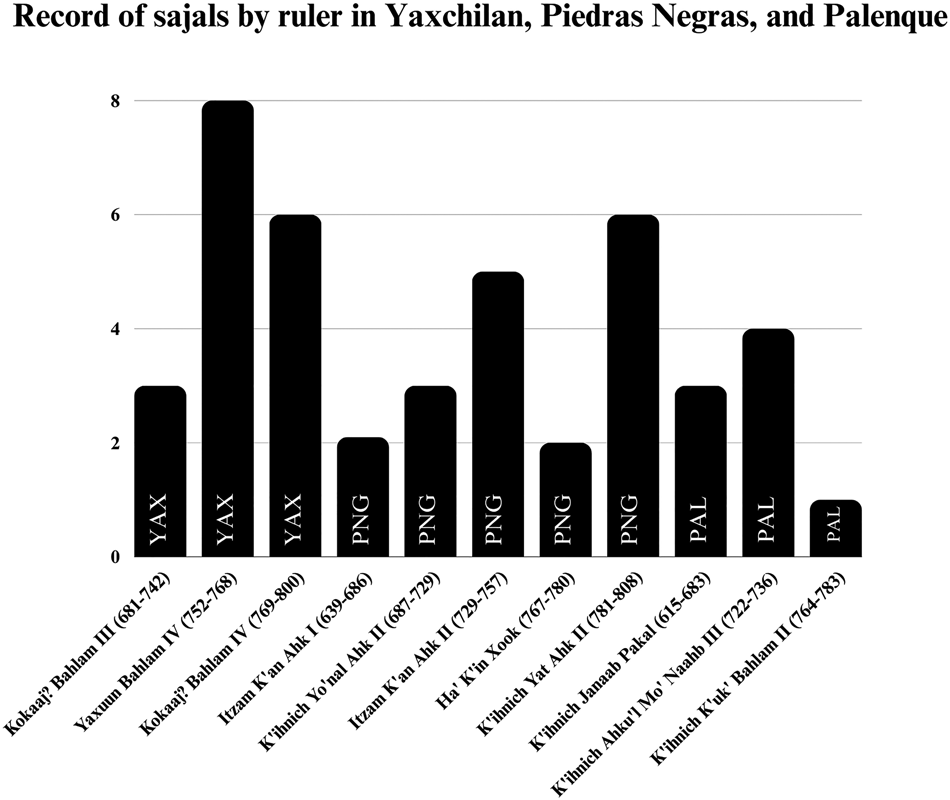

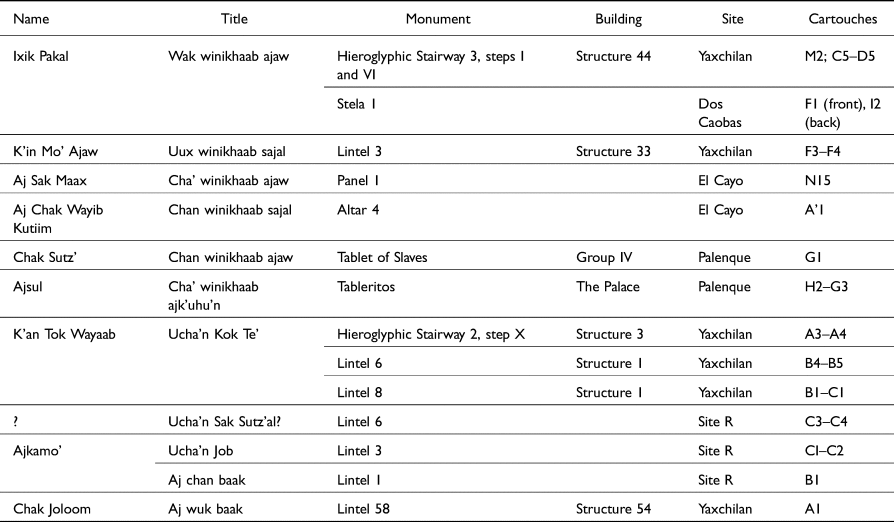

According to Sarah Jackson (Reference Jackson2013), the earliest known records of sajals on stone monuments in the western Maya Lowlands are from Palenque during the reign of K'ihnich Janaab Pakal (a.d. 615–683). Still, most examples are from the eighth century in the Yaxchilan area (Table 1 and Figure 3). Initially, sajals were only referenced in the texts on rulers' monuments; subsequently, they were included in iconography, often depicted alongside kings. Their incorporation favored deploying new strategies to allude to multiple political agents within the discourse. One of the most significant changes was the elaboration of monuments by these officers, whose discourse aimed to reaffirm their positions in local political hierarchies and replicate elements used simultaneously by the k'uhul ajaw.

Table 1. Sajals in the texts of the analyzed monuments of Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque.

* Chak Joloom and Ix Chak Joloom were also sajals during the government of Yaxuun Bahlam IV, so they are also considered in his record.

Figure 3. Record in hieroglyphic texts of sajals by each ruler in Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque during the Late Classic period.

Let us delve into the case of Yaxchilan and examine how the rulers integrated sajals into their monuments. A common theme on lintels and stelae during the reign of Kokaaj? Bahlam III (a.d. 681–742) was warfare and the capturing of prisoners. The predominant style consists of recording the capture date and the prisoner's name in hieroglyphic texts, whereas iconography shows the captive subdued and tied in front of the ruler. This intermediality between text and image creates a metonymy that alters the timeline of the narrative (Velázquez García Reference Velásquez García2017:375–376), given that it omits the exact moment of capture and displaces it to the exhibition of the prisoner before the k'uhul ajaw without revealing the identity of the captor. In addition, the passive-voiced verb chuhkaj (”was captured”) reinforces metonymy by omitting the agent or subject who made the capture, thereby giving relevance to the patient or object of the action—the prisoner.

This narrative style highlights the significance of the prisoner of war and his origin, suggesting that the rulers of Yaxchilan aimed to showcase their geographical-political dominance. As Charles Golden and Andrew Scherer (Reference Golden, Scherer, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020:235) propose, by registering the imprisonment of individuals from places such as Buktuun, Lacanha', Namaan, Sak Tz'i', Hix Witz, Motul de San José, and Lakamtuun, the leaders of Yaxchilan were showing their political jurisdiction and, therefore, the authority to exercise power over trade routes and circulation in the regional landscape constantly disputed with Piedras Negras.

Variations of this style occur when referring to the captor in iconography. Sometimes, the ruler is depicted as the captor, but in monuments outside the capital, sajals are shown instead. One of the first monuments on which sajals capture prisoners is Stela 1 of Dos Caobas (Figure 4) and the Drum Altar of the Fundación La Ruta Maya, whose origin is unknown (perhaps from somewhere on the Guatemalan side of the Usumacinta) (see Grube and Luin Reference Grube and Luín2014). In both cases, actors likely representing sajals imprison or present the captives to the ruler.

Figure 4. A possible sajal holding a prisoner in front of Kokaaj? Bahlam III. Stela 1, Dos Caobas. Drawing by the author.

In Yaxchilan, K'an Tok' Wayaab―the principal sajal―and Yaxuun Bahlam IV (a.d. 752–768) share a scene depicting a capture in Lintel 8 (see Figure 7). Another example is the presentation of captives to Kokaaj? Bahlam IV (a.d. 769–800) by Aj Chak Maax in Laxtunich Lintel 1 of the Kimbell Art Museum (KAM) (see Houston Reference Houston, Scherer, Taube and Houston2021). The same scenes are also featured in Panel 4, Panel 15, and Stela 12 of Piedras Negras (see Stuart and Graham Reference Stuart and Graham2003).

Parallel hierarchies

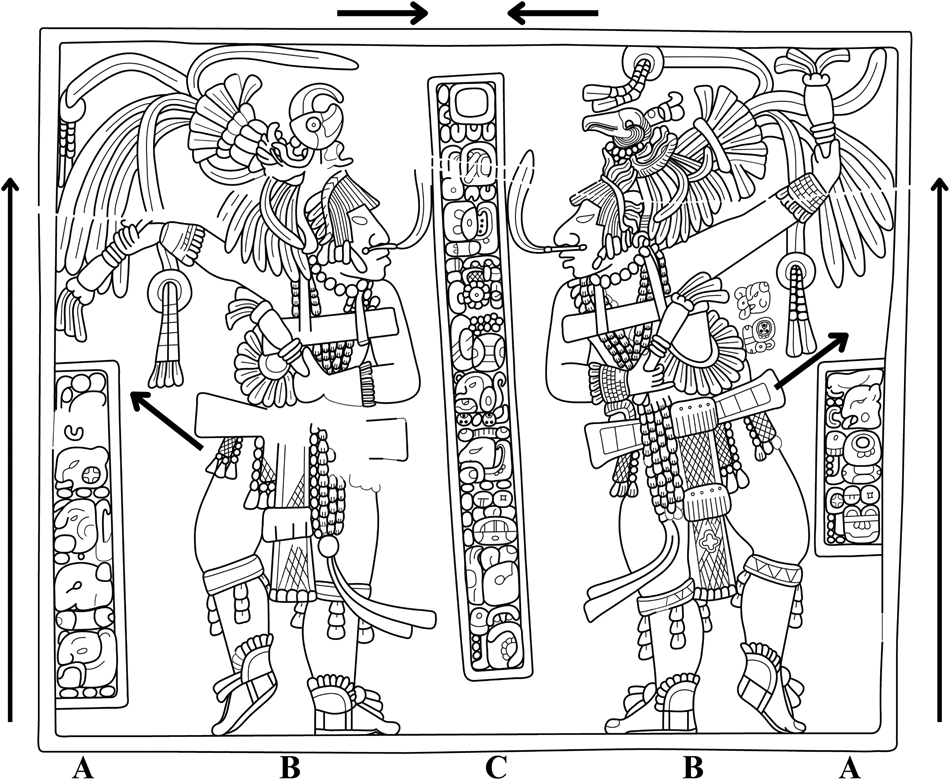

The sajals' inclusion in the discourse prompted artists to reinforce the established visual hierarchy, with the k'uhul ajaw as the primary focus. This aspect is entirely fulfilled in monuments such as Lintels 3, 12, and 42 of Yaxchilan; Lintels 3 and 4 of Site R; Lintel 1 of La Pasadita; Stela 2 of Dos Caobas; and Stelae 5 and 12 of Piedras Negras, among others, where the rulers possess the qualities of discursive salience that have been previously discussed. However, some compositions show an equalization of sociopolitical status between sajals and rulers, either through dress (see Parmington Reference Parmington2003), similar tension vectors, or through bilateral symmetry and chiasmus—a rhetorical figure that occurs when an element or phrase of a passage passes inverted to a second passage, generating the AB-BA structure (Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins Reference Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins2018:173; Christenson Reference Christenson, Hull and Carrasco2012:311).

Parallel hierarchies in discourse are a feature present mainly in monuments outside the capitals as a strategy for the sajals to increase their status in their areas of influence. Monuments of sites affiliated with the political sphere of Yaxchilan, such as La Pasadita and Site R, provide examples. Lintel 2 at La Pasadita registers a scattering ritual performed by Yaxuun Bahlam IV with sajal Tilo'm in a.d. 766, who appears to have a close relationship with the ruler.

The lintels of Site R tell the story of Ajkamo' and Yax Tok Wela'n―the local sajals―and their quest for political power within Pa'chan, the ruling lineage of Yaxchilan. Lintel 1 shows the tension vectors that emphasize verticality in the ruler (right). However, this feature is also present in the Ajkamo' representation (left), combined with the frontal view of both individuals' bodies, a convention that in Yaxchilan only concerned the k'uhul ajaw (Figure 5). The same happens in Lintels 2, 4, 5, and 6 of this settlement, in which the representations resemble the hierarchies between Yaxuun Bahlam IV and sajals (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Example of equalization of hierarchies between Kokaaj? Bahlam III and sajal Ajkamo’ in Lintel 1, Site R. Drawing by Peter Mathews (Jackson Reference Jackson2013:Figure 15).

Figure 6. Example of chiasmus and equalization of hierarchies between Yaxuun Bahlam IV and sajal Yax Tok Wela'n in Lintel 5, Site R (after Looper Reference Looper2009:Figure 1.18). Drawing by the author.

Figure 7. Chiasmus at Lintel 8, Yaxchilan. Underside: drawing by Ian Graham © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.5.8.

As mentioned earlier, the chiasmus is a rhetorical figure that sculptors use to create a crossed parallelism. Allen J. Christenson (Reference Christenson, Hull and Carrasco2012) has analyzed the presence of chiasmus in colonial texts such as the Popol Wuj, the Rabinal Achí, and the Title of Tononicapan (among others), detecting that it occurs more frequently during dialogues. Therefore, the idea of its iconographic use to equalize the elements of the discourse would make sense, as would happen during a conversation.

Chiasmus appears on Yaxchilan's Lintel 8 (Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins Reference Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins2018:173). On the right is Yaxuun Bahlam IV apprehending “Jeweled Skull,” a politically significant individual whose capture—along with the capture of another prisoner named Ajuk—was incorporated into the titles of Yaxuun Bahlam IV. On the opposite side, the sajal K'an Tok' Wayaab holds Lord Kok Te', whose capture was similarly incorporated into the sajal's titles. Despite both capturing similarities in the scene, the text only records the imprisonment of “Jeweled Skull” at the hands of Yaxuun Bahlam IV, perhaps as a way of giving discursive salience to the k'uhul ajaw.

The rhetorical figure in question is also applied in Lintels 5 and 6 of Site R. In Lintel 5, two individuals dance while wearing identical attire except for their headdresses (see Figure 6). The dancer on the right wears a headdress with a vulture head in front, and the one on the left wears a headdress with a macaw head. A hieroglyphic text divides and balances the representation in the scene's center by directing tension vectors outward and toward the center again, as indicated by the reading order of the texts. The vectors on the sides of the monument promote verticality in dancers without indicating hierarchy or discursive salience. The assumption is that the ruler is on the right side, but a complete identification can only be made by referencing the text that contains his name. The lintel mentions that on February 2, 766, Yax Tok Wela'n ―a young sajal of Yaxuun Bahlam IV― danced wearing Utmo'hu'n, the name of the macaw headdress.

Like Lintel 2 of Site R, the representation of the two dancers is similar because it aims to equalize their sociopolitical hierarchies. It should also be noted that the name of the dance is associated with the headdress of the sajal rather than the attire of the ruler. Consequently, both in image and text, we observe that the sajal becomes a discursive focus—a characteristic absent in other monuments—and that it will be a more recurrent element in discourses of the secondary sites of Yaxchilan during the latter half of the eighth century. Lintel 6 of Site R has a scene similar to Lintel 5 but without any dance references. Yaxuun Bahlam IV stands on the right, wearing clothes similar to the accompanying sajal, distinguished by his headdress and front-knotted pectoral. The two individuals hold spears and banners, but the ruler's spear divides the scene along with the hieroglyphic text; the composition produces the chiasmus.

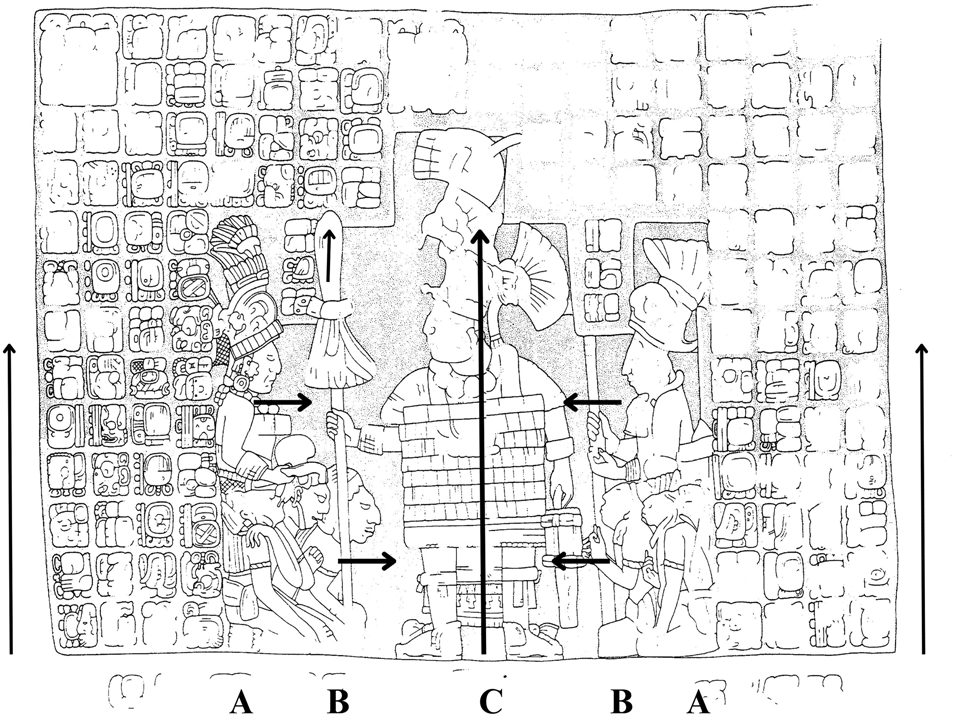

Chiasmus also manifests itself in the political sphere of Piedras Negras, particularly in Panel 15 (dating to ca. a.d. 707), whose composition produces the structure AB-C-BA (Figure 8). The main element―the C―corresponds to the figure of ruler Itzam K'an Ahk I (a.d. 639–686), who is represented with all the conventions to mark his hierarchical significance. The k'uhul ajaw directs a tension vector toward element A, a possible sajal or official in profile; he presents three prisoners―naked and kneeling―who constitute the B motif of the scene. On the other side, element B represents two captives with the same disposition as the previous ones, whereas element A shows another possible sajal that presents the prisoners to the ruler.

Figure 8. Chiasmus at Panel 15, Piedras Negras. Drawing by Stephen Houston (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Escobedo, Child, Golden, Terry and Webster2000:Figure 5).

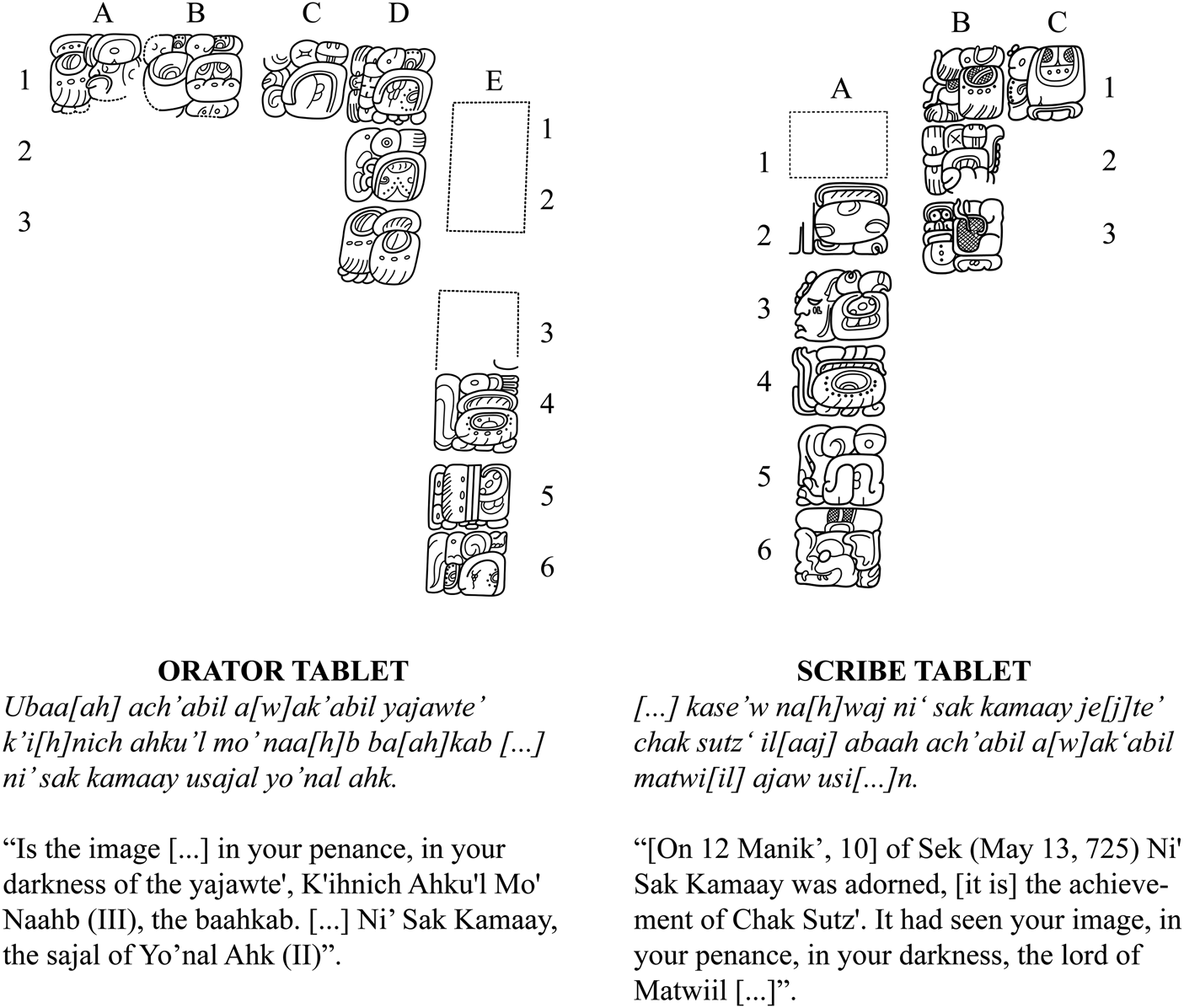

Palenque's Tablets of the Orator and the Scribe use chiasmus in their short texts (Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins Reference Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins2018:170). The Orator Tablet features a diphrasism in section A: “Is the image […] in your penance, in your darkness.” This is followed by section B that corresponds to the subject: “The yajawte' K'ihnich Ahku'l Mo' Naahb III, the baahkab […].” For its part, the Scribe Tablet begins with section B, composed of the verb and the subject: “Ni' Sak Kamaay was adorned, [it is] the achievement of Chak Sutz': And then section A: “It had seen your image, in your penance, in your darkness” (Figure 9). In this way, the chiasmus would have the purpose of generating a parallel between the k'uhul ajaw K'ihnich Ahku'l Mo' Naahb III (a.d. 722–736) and the sajal Chak Sutz'.

Figure 9. Chiasmus in the texts of Orator and Scribe Tablets, Palenque (after Schele and Mathews Reference Schele and Mathews1979:Figures 141 and 142). Transcription, translation, and drawing by the author.

Titles associated with counting katuns and capturing prisoners of war were also used by sajals and other members of the intermediate elite to imitate the sociopolitical status of the k'uhul ajaw. For the counting katuns, we have some examples: Ixik Pakal, who uses the title “lady of the seven katuns”; K'in Mo' Ajaw, “sajal of three katuns”; Aj Sak Maax, “lord of two katuns”; Aj Chak Wayib Kutiim, “sajal of four katuns”; Chak Sutz', “lord of four katuns”; and Ajsul, “ajk'uhu'n of two katuns.” Regarding war titles, the sajals did not only tally the number of prisoners held in the same style as rulers; they also recorded the names of the most important captives in the titles, but this was only done in the Yaxchilan region. This is the case of K'an Tok Wayaab, who used “the possessor of Kok Te'”; Ajkamo', “the possessor of Job” and “one of the four captives”; the sajal with the title “the possessor of Sak Sutz'al?”; and Chak Joloom, “one of the seven captives” (Table 2).

Table 2. Sajals’ titles associated with counting katuns and capturing prisoners of war.

Narrative imitation

The sajals adopted some narrative structures of cities' monuments into their discourses; for instance, the narrative style of funeral monuments honoring a k'uhul ajaw, which records the individual's life, including birth and death dates, office ascension, lineage, and funeral ritual (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Rivera and Le Fort2006). In Piedras Negras, evidence of ancestor veneration style can be found in tombs, monuments such as Stela 40, and panels honoring distinguished ancestors, such as Panels 4, 12, and 15 (Hammond Reference Hammond1981; Scherer Reference Scherer2015). As a biography, this narrative style was used by sajals of the El Cayo area to honor their ancestors and lineages, thereby validating their local status and differentiating themselves hierarchically from other members of the intermediate elite.

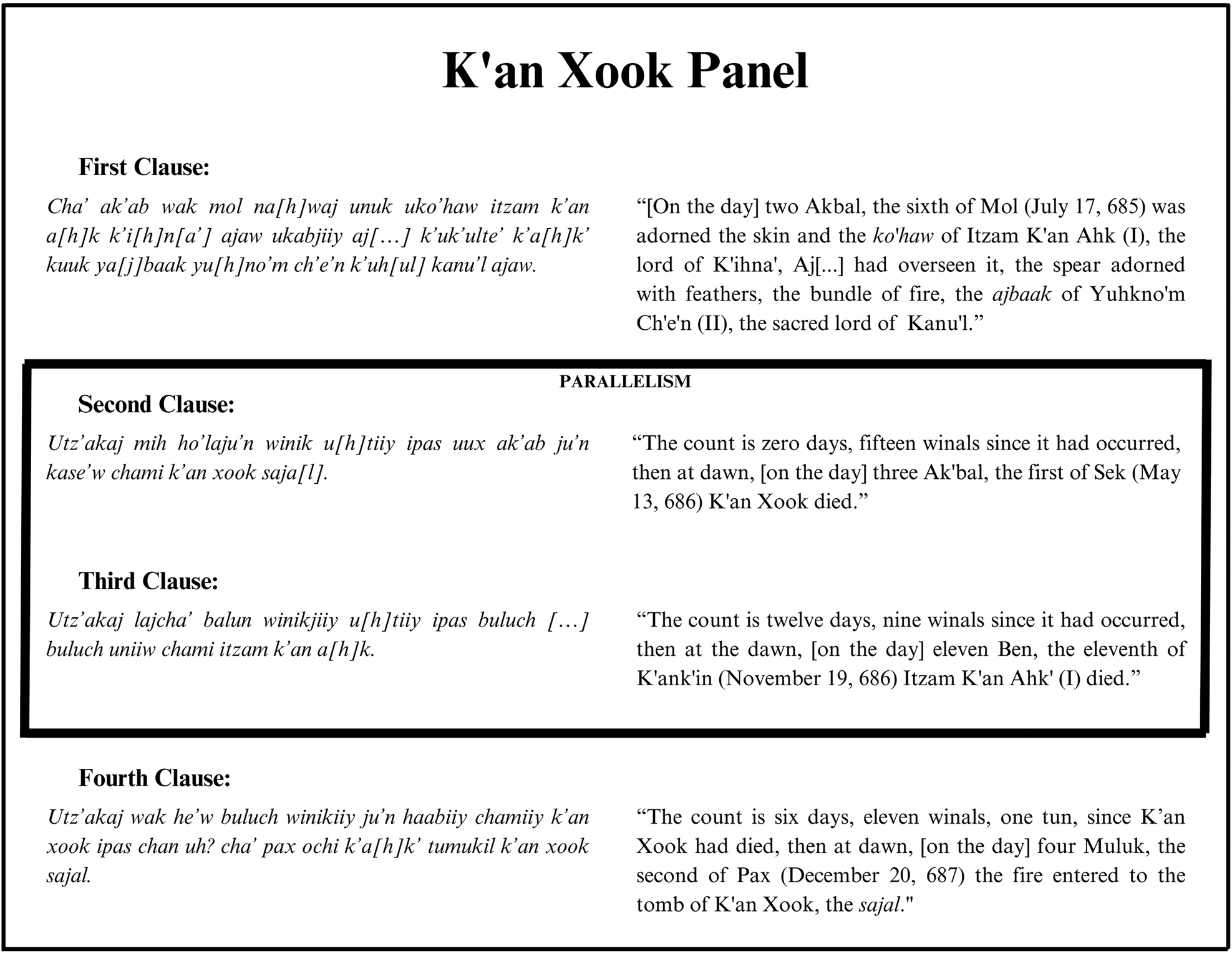

The K'an Xook Panel is an excellent example of this practice; it is the only one from the time of Itzam K'an Ahk I, created by a sajal named K'an Xook. The hieroglyphic text contains four clauses (Figure 10). The first clause describes the adornment of Itzam K'an Ahk I on July 17, 685. He was embellished with different warrior insignias, including clothing, the ko'haw (war helmet covered in jade plaques), a spear with feathers, and a bundle. This action, referred to in a passive voice verb―nahwaj―to omit the person who embellished the ruler, was supervised by the ajbaak of Yuhkno'm Ch'e'n II, the k'uhul ajaw of Kanu'l (Calakmul). The second clause corresponds to the death of K'an Xook on May 13, 686, followed by the third clause that records the death of Itzam K'an Ahk I just six months later. Perhaps both deaths constitute a parallelism that aims to equate both individuals. Finally, the fourth clause closes with the funeral ceremony at the tomb of K'an Xook on December 20, 687.

Figure 10. K'an Xook Panel structure indicating the parallelism between the deaths of the sajal and the ruler.

The Dumbarton Oaks Panel also documents the posthumous biography of sajal Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy. The text imitates Panel 15 of Piedras Negras, so the discourse opens with the date of birth of Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy on April 28, 649, followed by the names of his parents, Ixik Ahk […]oxo'm and the sajal Mo' Ahk Chamiiy. The panel also registered when Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy became sajal, like the recording of Itzam K'an Ahk I's enthronement in Panel 15.

K'ihnich Yo'nal Ahk II (a.d. 687–729) oversaw the accession to the sajal office referred to as johyaj ti sajalil, similar to the expression johyaj ti ajawlel, used by rulers to indicate their debut in lordship. The purpose was to show a political structure like the ajawlel, but on a smaller scale, to imitate the act of enthronement. The son of Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy―Siyaj Chan Ahk―used this exact phrase to mention his ascension to office, now under the supervision of Itzam K'an Ahk II (a.d. 729–767). Based on the expression johyaj ti sajalil, the political ritual to take office could involve a procession, as Alejandro Sheseña Hernández (Reference Leeuwen2015:18) has pointed out, similar to that performed by the k'uhul ajaw but different in that it was the ruler who supervised the sajal, recognized him in office, and gave him greater status (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Rivera and Le Fort2006:10). Finally, the discourse closes with the funeral ritual at the burial of Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy, as in Panels 4 and 15, K'an Xook, and New Orleans.

For the first time, as Sarah Jackson (Reference Jackson2013) has previously highlighted, the Dumbarton Oaks Panel allows us to reconstruct the genealogy of a sajal and determine that, in this case, the office was inherited and belonged to hierarchical corporate groups connected through lineage (see Figure 11). The reference to the parents of the sajal―Ixik Ahk […]oxo'm and Mo' Ahk Chamiiy―occurs after the introductory clause that refers to his birth, exactly as it does in Panel 15 of Piedras Negras. It is important to remember that both panels are biographies created after the deaths of the leaders; therefore, the sajal Siyaj Chan Ahk could also perform the mortuary ritual to honor Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy and establish his family's legitimacy and identity.

Figure 11. Genealogy of sajals from the Ahk Chamiiy and K'utiim lineages.

Despite the prominence that Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy has in the Dumbarton Oaks Panel, he was never mentioned in the monuments of the k'uhul ajaw K'ihnich Yo'nal Ahk II, unlike the sajal K'an […] Te', who stands next to the ruler on Stela 5 of Piedras Negras. Consequently, two discourses are co-occurring, one belonging to the sajals of the Dumbarton Oaks Panel, who seek to legitimize themselves within their political sphere without being, apparently, so close to the ruler.

In addition, like the Dumbarton Oaks Panel, the Supports of Altar 4 from El Cayo include a posthumous biography. In this monument, the sajal Aj Chak Wayib K'utiim referred to his parents―Xaakil Ochnal K'utiim and Lady Hiib―and his birth on September 5, 664. The Dumbarton Oaks Panel and Altar 4 are from the same period and contain sajals that record information about their lineage and political and religious development within their communities. However, the Aj Chak Wayib K'utiim monument does not mention any ruler of Yokib, the name of the Piedras Negras lineage (Figure 11).

The posthumous biography style is also present in the Palenque area, although in a different format from that of Piedras Negras. The first case is in a stone censer from Group IV that mentions members of the Ajsik'ab lineage, who served as ti' sakhu'n, yajaw k'ahk', and sajals during the reigns of K'ihnich Janaab Pakal (a.d. 615–683), K'ihnich Kan Bahlam II (a.d. 684–702), and K'ihnich K'an Joy Chitam II (a.d. 702–720). Another example is the K'an Tok Tablet, which lists the taking office of “banded bird” priests from the K'an Tok' Wawe'el lineage, who may have lived in Temple XVI (for the title “banded bird,” see Bernal Romero and Venegas Durán Reference Bernal Romero and Durán2005:10; Biró et al. Reference Biró, MacLeod and Grofe2020:133–136; Izquierdo and Bernal Romero Reference de la Cueva, Luisa, Romero, Izquierdo and de la Cueva2011:164; Jackson Reference Jackson2013:15; Polyukhovych et al. Reference Polyukhovych, Gamboa and Garcíain press:746; Stuart Reference Stuart2005:113). Although no information indicates they were sajals, the record of this lineage is akin to the abovementioned examples and relevant to understanding how the intermediate elites were structured in Palenque.

The sajals and their separate representation

So far, the discourse of the sajals from the Western Maya Lowlands shares features with and emulates the k'uhul ajaw monuments. In one way or another, most sajals are associated with rulers to legitimize their political power. However, the discourse changed significantly as sajals gradually stopped alluding to rulers, indicating individual hierarchical positions. This phenomenon is critical because it could show the loss of cohesion of some political segments, whose independent action could have destabilized the regional system headed by the k'uhul ajaw. I will return to this discussion later.

The sajals gained discursive salience in iconography through bodily frontality, dressing like rulers (Parmington Reference Parmington2003), and being depicted on the right side of monuments where only the k'uhul ajaw had previously been shown. This pattern is visible in Lintel 2 of La Pasadita, Lintels 2 and 3 of Site R, and Lintel 6 of Yaxchilan, where Yaxuun Bahlam IV appears on the left side. The new composition suggests that these officials were being recognized at a higher level and playing a more prominent role in local politics.

Monuments featuring individual representations of sajals were prevalent in the Piedras Negras region during the eighth century. Nevertheless, the earlier examples come from the Palenque area, as is the case of the sajal and yajaw k'ahk' of the Miraflores Tablets—whose name is unknown—and Ajsul in the Stone Censer of Group IV. In the Usumacinta area, all the examples were elaborated in the peripheries of the cities, such as Aj Chak Wayib Kutiim at Altar 4 of El Cayo (a.d. 731); Chak Tok' Tuun Ahk Chamiiy in Dumbarton Oaks Panel (a.d. 733); Tilo'm in Lintel 4 of La Pasadita (a.d. 771); K'uhul Ka[…], represented in Panel 2 of El Cayo (a.d. 792); and Lady Hoob in the Cleveland Panel (a.d. 795) (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Individual representations of intermediate elites in the western Maya Lowlands.

It is worth noting that this phenomenon appears to follow a circulation pattern originating from the northwestern region and moving toward the Usumacinta. Earlier examples of individual representations of intermediate elites in Tonina predate those of Palenque. In Monument 173, the ajk'uhu'n Aj Mih K'inich appears individually in a.d. 612, whereas in Monument 181, dedicated in a.d. 633, it is Juun Tzihnaj Hix Tuun who is represented independently and who narrates his investiture as ti'hu'n (Sánchez Gamboa et al. Reference Gamboa, Ángel, Sheseña, Krempel and Angulo2019:450–452). Both individuals wear a band with the “jester god” on the forehead, which is believed to be an exclusive insignia to the k'uhul ajaw (Fields Reference Fields, Robertson and Fields1991:3), but which is also worn by the baah sajal K'an Tok Wayaab in Lintel 42 of Yaxchilan. These examples show a trend of nonruling officers depicted individually on monuments, with symbols of power previously exclusive to the k'uhul ajaw.

The artists

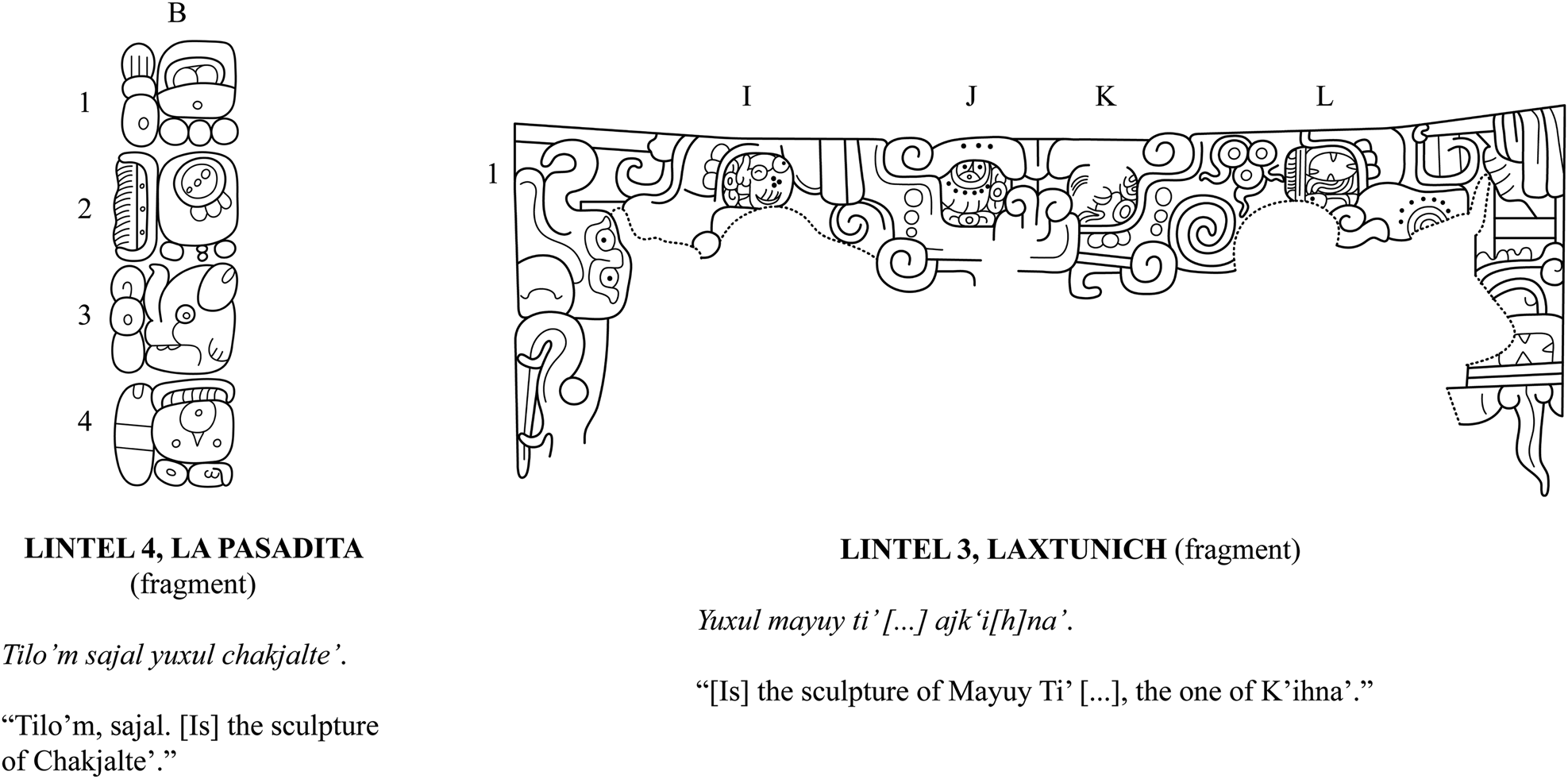

The individual representations of sajals in the monuments and their implications at the discursive and political levels are linked to artists as agents of this change in the stage of discourse production (see Table 1). Recall that several sculptors elaborated stone monuments, although only the most experienced left evidence of their authorship through their signatures (Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016). The expression that predominates is “yuxul [name of the artist] [Title],” “It is the sculpture of Mayuy Ti' […], aj k'ihna'.” Signatures were often added to monuments in the late seventh century and were typically positioned at the periphery of the sculpture, in small areas, and away from discursive foci (Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016:413; Montgomery Reference Montgomery1995:27). In other words, artists’ signatures were placed outside the central area of the sculptural space or the representation of the ruler, and their hieroglyphic cartouches were smaller and incised, which meant that the viewer had to approach the sculpture to read them (Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016:413).

The increase in sculptors' signatures during the Late Classic period was probably related to demographic growth and sociopolitical changes, particularly those involving sajals. Over time, as agents of discursive transformations, artists made their presence known by increasing the size of their signatures and incorporating them in important places within the pictorial spaces of monuments. Like the individual representation of sajals, this modification could reflect a more complex and fragmented elite in competition for power with other leaders. This is clear in Panel 2 from El Cayo and the Cleveland Panel, where artist signatures are incorporated into the background of the scenes, often near the principal figures. The same phenomenon is in the Dumbarton Oaks Panel, but the cartouches are now sized similarly to the main text and are situated on the right side of the depiction, a location that constitutes a discursive focus.

At Bench 1 at the Palace of Palenque, Ajen Sak Ik' added his signature to the main text, similar to Lintels 3 and 4 of La Pasadita with the sculptor Chakjalte'. In Lintel 3, the signature appears next to the name of Yaxchilan's ruler Kokaaj? Bahlam IV, whereas in Lintel 4, the size of the cartouches is the same as the clause that includes the name of the sajal Tilo'm, implying equal status (Figure 13). In Laxtunich Lintel 1 (KAM), although with small cartouches, the signature of Mayuy Ti' is in the center of the captive-presenting scene. In Lintel 3 of the same site, the artist incorporated his signature in the body of the Starry Deer Crocodile and the eyes of a Witz representation (mountain)—the central element of the entire composition (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Signatures of Chakjalte’ and Mayuy Ti’ (after Teufel Reference Teufel2004 and Houston Reference Houston, Scherer, Taube and Houston2021). Drawings by the author.

Mayuy Ti' is an exceptional case. He is an artist from the Piedras Negras area―the enemy capital of Yaxchilan―who produced two of four high-quality lintels for Kokaaj? Bahlam IV. He used the standard hierarchical-palatial style of Piedras Negras and the surrounding area, featuring depictions inside the palace where the individuals represented generate tension vectors to mark different visual and sociopolitical hierarchies. The style is not typical in Yaxchilan, nor is the use of blue backgrounds (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Scherer, Taube and Houston2021:73; Zender Reference Zender and Stone2002:172–173).

Mayuy Ti's lintels refer to the ruler of Pa'chan as Chelew Chan K'inich, the name of his youth, instead of his official name (Kokaaj? Bahlam). Stephen Houston, Andrew Scherer, and Karl Taube (2021:75) detect variations in the paleographic writing of certain words―such as k'inich―compared to the Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan corpus, which could be an indication of the inventiveness of this artist. Based on the inferior quality of the monuments in Yaxchilan during this period and the extensive skill demonstrated in the monuments of Mayuy Ti' in Laxtunich, it is possible to speculate that local sajals―Aj Chak Maax (Lintel 1 KAM) and Aj Yax Bul K'uk' (Lintel 3)―provided the sponsorship for the lintels rather than a k'uhul ajaw of Yaxchilan.

It also has been suggested that Mayuy Ti' was either a traitor or an artist who was captured by Yaxchilan and forced to create monuments at the capital's periphery (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Scherer, Taube and Houston2021:42; Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2021:514; Safronov Reference Safronov, Eeckhout and Font2005:50). However, other aspects suggest an alternate possibility: that Mayuy Ti' had the freedom to move around during a period of political decentralization in the Usumacinta region. As part of this discussion, it is essential to mention that the two monuments signed by Mayuy Ti'—in addition to manifesting the hierarchical-palatial style absent in Yaxchilan—are related to other discursive units manufactured in the periphery, such as Stela 2 of La Mar.

Lintel 3 of Laxtunich and Stela 2 of La Mar seem to reproduce small cosmograms in which the ruler is the axis mundi. Nevertheless, the central part of Laxtunich Lintel 3 is occupied by Chelew Chan K'inich and the sajal Aj Yax Bul K'uk', with two sajals serving as symbolic supports (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Scherer, Taube and Houston2021:100). This suggests that both political agents share status and are cosmic axes, sustaining their power in a shared way from the sacred realm. In contrast, the iconography of Lintel 2 of Laxtunich resembles Lintel 3 of El Chicozapote, so I could suggest that the artists of these sites shared their styles—absent in the capitals—and transited more frequently between peripheral sites during this moment compared to previous years.

In addition, the stylistic particularities of Mayuy Ti' show that the intermediate elites may have had more agency and influence in the late eighth century. This would explain the significant changes in the representation of political hierarchy in the discourse, where sajals were depicted individually, with symbols of high honor, and even sharing cosmic positions with the k'uhul ajaw, as in the examples above. In Piedras Negras and Palenque, no contemporary examples match the technical prowess of Laxtunich; this proposes that sajals may have gained prestige and political influence that could have challenged the power of the regional k'uhul ajaw.

Discussion

Previous case studies show that the most significant discursive changes in the western Maya Lowlands occurred in the second half of the eighth century and were closely linked to the intermediate elites—primarily sajals. The observed transformations are related to recording the political hierarchy of sajals. These exhibit not only the rivalry and competition with the k'uhul ajaw but also the various stages that the regional political structure experienced during phases that oscillated between stability and crisis until its decline in the ninth century.

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the states ruled by the Pa'chan (Yaxchilan), Yokib (Piedras Negras), and Baake'l (Palenque) lineages enjoyed periods of stability and growth. The rulers strengthened their power by reinforcing traditional values that connected them with the divine and by controlling resources to exercise power, including the distribution of goods, formation of alliances with other political groups, use of coercion, and enforcement of ideological control (Earle Reference Earle1997, Reference Earle and Haas2001; Mann Reference Mann2005). At this time, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque were experiencing population growth, expanding their surrounding areas, and undergoing urban expansion (Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2011:74, Reference Golden and Scherer2013a:166; Liendo Stuardo Reference Liendo Stuardo and Stuardo2011:78, Reference Liendo Stuardo2014:72; Schele Reference Schele and Patrick Culbert1991:78; Schele and Mathews Reference Schele, Mathews and Patrick Culbert1991:250–251; Scherer and Golden Reference Scherer, Golden and Iannone2014:220).

The sociopolitical complexity caused by population growth became a trigger that destabilized the political system, given that the presence of more officials (such as sajals) caused political competition with rulers. The k'uhul ajaw found a solution by implementing strategies, such as dominating nearby sites through war, organizing rituals, and forming alliances with sajals to negotiate power (García Barrios and Valencia Rivera Reference García Barrios and Rivera2007:33; Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2013b:412; Regueiro Suárez Reference Regueiro Suárez2021:120–121). They also assigned hierarchical titles to this sector to confer political power within their spheres of dominion. Likewise, stone monuments were significant devices for transmitting political ideology and hierarchies. The discourses inscribed in them regulated political tensions and left testimony to the process of decentralization that occurred as sajals recorded diverse and independent narratives over time.

The k'uhul ajaw employed strategies to make the political system more flexible amid new political actors' struggle for power and recognition. By examining the sajals' discourse, we can understand how they adjusted to changing circumstances by creating monuments intended to increase their political influence in a manner previously unavailable to actors other than the rulers. Therefore, they have been observed to dress similarly to the k'uhul ajaw, wear power insignia, and refer to their lineage to legitimize their groups. Additionally, they had artists at their service, and their discourses complemented or diverged from those of the rulers, transgressed and imitated the conventions of hierarchy, and recorded their alliances and wars.

The increased independence of sajals is evident not just in monumental discourse but also through the circulation of goods, as demonstrated by archaeological evidence in the Usumacinta area. For example, an obsidian blade workshop was discovered in Budsilha, and a 5 kg jade fragment was found in Flores Magon, which is located 20 km northwest of Budsilha (Schroder et al. Reference Schroder, Golden, Scherer, Álvarez, Dobereiner and Cab2017:5). These findings have resulted in a proposal by Schroder and colleagues (Reference Schroder, Golden, Scherer, Álvarez, Dobereiner and Cab2017:5; see Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Schroder, Vella, Recinos, Masson, Freidel, Demarest, Chase and Chase2020) that during the Late Classic period, the rulers of smaller centers had more influence and were able to acquire and distribute luxury items among local elites. This excluded larger capitals such as Piedras Negras, which had limited access to materials such as jade and obsidian (Golden and Scherer Reference Golden, Scherer, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020:230; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, René Muñoz and Hruby2012:15; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Schroder, Vella, Recinos, Masson, Freidel, Demarest, Chase and Chase2020:411; Schroder et al. Reference Schroder, Golden, Scherer, Álvarez, Dobereiner and Cab2017:5).

Conclusion

Monuments sponsored by the sajals had political messages that aimed to show their higher status in comparison to other political groups by imitating conventions previously reserved for the k'uhul ajaw. These messages were conveyed through panels and lintels, usually located inside or on top of buildings, suggesting that they were only accessible to a select few. Therefore, these discourses were likely intended for specific audiences, indicating that they were produced and circulated among the elites for political purposes. By analyzing the discourses of the k'uhul ajaw and sajals' monuments, we can detect changes in the political system and the implementation of cooperative and competitive strategies. These changes resulted from a shifting landscape where sajals gained political relevance and prestige in Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Palenque. When looking at the sajals’ monuments, we notice that they initially followed traditional patterns to highlight the authority of rulers. However, toward the end of the eighth century, these conventions were gradually discarded to emphasize sajals' political hierarchy and lineage, resulting in the exclusion of the k'uhul ajaw from monuments. This leads me to suggest the existence of political competition between the two sectors and greater independence on the part of sajals.

Archaeological evidence and stone monuments suggest that the causes of the crisis in the late eighth and early ninth centuries may have been linked to the intermediate elites—especially the sajals—and political fragmentation. As political networks became more decentralized, elites became more involved in the distribution of goods and exchanges of ideas in peripheral sites. This gradual process became more noticeable in the ninth century throughout other cities of the Maya Lowlands, as demonstrated by late monuments in which a “cosmopolitan” style is presented, resulting from increased ideological contact with different areas of Mesoamerica (Halperin and Martin Reference Halperin and Martin2020; Lacadena Reference Lacadena, Vail and Hernández2010).

Some monuments in Ceibal, Altar de Sacrificios, Ucanal, and Calakmul contain foreign iconographic elements and square-framed calendrical glyphs from Central Mexico (Halperin and Martin Reference Halperin and Martin2020:820; Lacadena Reference Lacadena, Vail and Hernández2010:385). An example can be seen in Stela 2 of Jimbal, dating to a.d. 889. The style employed in the monument is a mixture of different elements, with a change in the usual reading order, usage of square-framed signs, and different versions of logograms. This could indicate the involvement of foreign artists, possibly due to increased mobility and political decentralization in the Late Classic period.

During the process of power fragmentation, the ruler gradually lost authority, and the distribution of goods and labor was no longer controlled to guarantee the proper functioning of the political system and stable food resources for the community (Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2011:74; Scherer and Golden Reference Scherer, Golden and Iannone2014:226). Changes in the production and distribution of goods are evident in the ceramics industry. The quantity and quality of polychrome pottery used by the elite significantly decreased, whereas utilitarian ceramics remained the same. Therefore, it is clear that different groups were in charge of producing these materials, with elite ceramics suffering the most significant cultural decline (Forsyth Reference Forsyth, López Varela and Foias2005:10). Although sajals had access to power resources and enjoyed prestige in their areas of influence, they lacked the authority or legitimacy to replace the rulers. This is because their recognition was local, not regional. During this period of crisis, the k'uhul ajaw institution was the first to disintegrate due to its inability to unite various political segments. The elite residential areas were later abandoned, possibly due to civil wars and poor living conditions.

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincerest gratitude to Charles Golden, Felix Kupprat, Alejandro Sheseña, Rodrigo Liendo, Sarah Jackson, Ana Luisa Izquierdo, Daniel Salazar, Ileana Echauri, Janeth Lagunes, Ángel Sánchez, Yuriy Polyukhovych, Martha Cuevas, Jason Nesbitt, and Jordan Kobylt for offering me their invaluable comments, their reviews, and materials to conduct this research. Finally, I would like to thank the Middle American Research Institute, The Stone Center for Latin American Studies at Tulane University, the Proyecto Arqueológico Busiljá-Chocoljá, and the three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Competing interests

The author declares none.