Introduction

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 Study ranked major depressive disorder (MDD) as the 2nd leading cause of years lived with disability in the world (exceeded only by low back pain) and the 1st–4th leading cause (out of nearly 300 considered) in each region of the world (Vos et al. Reference Vos, Flaxman, Naghavi, Lozano, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla and Aboyans2012). These high estimates are due to MDD having both high prevalence (estimated by the GBD 2010 investigators to be the 19th most common disease in the world) and high severity (indicated by higher ranking of MDD as a cause of disability than prevalent disease). However, MDD severity is highly variable (Birnbaum et al. Reference Birnbaum, Kessler, Kelley, Ben-Hamadi, Joish and Greenberg2010; Li et al. Reference Li, Aggen, Shi, Gao, Tao, Zhang, Wang, Gao, Yang, Liu, Li, Shi, Wang, Liu, Zhang, Du, Jiang, Shen, Zhang, Liang, Sun, Hu, Liu, Miao, Meng, Hu, Huang, Li, Ha, Deng, Mei, Zhong, Gao, Sang, Zhang, Fang, Yu, Yang, Chen, Hong, Wu, Chen, Cai, Song, Pan, Dong, Pan, Zhang, Shen, Liu, Gu, Liu, Zhang, Flint and Kendler2014). Indeed, severity is the most consistent discriminating characteristic in empirical studies of MDD symptom subtypes (van Loo et al. Reference van Loo, de Jonge, Romeijn, Kessler and Schoevers2012).

One of the strongest predictors of MDD severity is comorbid anxiety disorder (Mineka & Vrshek-Schallhorn, Reference Mineka, Vrshek-Schallhorn, Gotlib and Hammen2008; Wu & Fang, Reference Wu and Fang2014). Epidemiological studies show consistently that MDD is highly comorbid with numerous anxiety disorders (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Caraveo-Anduaga, Berglund, Bijl, Dragomericka, Kohn, Keller, Kessler, Kawakami, Kilic, Ustun, Vicente and Wittchen2003; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Petukhova and Zaslavsky2011b ; Lamers et al. Reference Lamers, van Oppen, Comijs, Smit, Spinhoven, van Balkom, Nolen, Zitman, Beekman and Penninx2011) and more severe and persistent when accompanied by comorbid anxiety disorders (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, VonKorff, Ustun, Pini, Korten and Oldehinkel1994; Roy-Byrne et al. Reference Roy-Byrne, Stang, Wittchen, Ustun, Walters and Kessler2000; McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, Khandker, Kruzikas and Tummala2006; Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Fischer and Kohlboeck2010). People with anxious MDD are also significantly more likely to seek treatment (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Keller and Wittchen2001; Jacobi et al. Reference Jacobi, Wittchen, Holting, Hofler, Pfister, Muller and Lieb2004) but significantly less likely to respond to treatment (Jakubovski & Bloch, Reference Jakubovski and Bloch2014; Saveanu et al. Reference Saveanu, Etkin, Duchemin, Goldstein-Piekarski, Gyurak, Debattista, Schatzberg, Sood, Day, Palmer, Rekshan, Gordon, Rush and Williams2014) than those with non-anxious MDD. Comorbid anxiety disorders have been found consistently to have earlier age-of-onset (AOO) than MDD both in cross-sectional surveys that assess AOO retrospectively (Kessler, Reference Kessler, Tsuang and Zahner1995; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Ormel, Petukhova, McLaughlin, Green, Russo, Stein, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Haro, Hu, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Matchsinger, Mihaescu-Pintia, Posada-Villa, Sagar and Ustun2011a ) and prospective studies that examine unfolding of comorbidity over time (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Olivier, Sobol, Monson and Leighton1986; Bittner et al. Reference Bittner, Goodwin, Wittchen, Beesdo, Hofler and Lieb2004; Copeland et al. Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Costello and Angold2009; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Glenn, Kosty, Seeley, Rohde and Lewinsohn2013).

Two noteworthy limitations of existing research on comorbid anxiety in MDD are that a narrow definition of comorbid anxiety is often used that either focuses on current (but not lifetime) comorbidity or examines only one anxiety disorder (typically generalised anxiety disorder or panic disorder) and that these studies are typically, although not always (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Wang, Lin, Chen and Huang2014), carried out in high-income Western countries. We address both limitations here by presenting cross-national epidemiological data on comorbidities of DSM-IV anxiety disorders and MDD using a composite measure that includes a wide range of anxiety disorders in a coordinated series of 27 community epidemiological surveys carried out in 24 countries throughout the world. We estimate the proportions of survey respondents with lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV MDD who also met criteria for one or more lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV anxiety disorders. We examine cross-national consistencies in AOO priorities between comorbid anxiety disorders and MDD, whether anxious MDD is more severe and persistent than non-anxious MDD, and whether people with anxious MDD are more likely than those with non-anxious MDD to obtain professional treatment for MDD. We also examine cross-national consistency in basic socio-demographic correlates of anxious and non-anxious MDD.

Methods

Sample

Data come from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys, a series of community epidemiological surveys administered in ten countries classified by the World Bank (World Bank, 2009) as low or middle-income (Brazil, Bulgaria, Colombia, Iraq, Lebanon, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Peoples Republic of China (PRC) and Romania) and 14 high income (Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Spain and the USA). The majority of surveys (five in low/middle-income countries, 13 in high-income countries) were based on nationally representative household samples. Two were representative of all urban areas in their countries (Colombia, Mexico). Two were representative of selected regions in their countries (Japan, Nigeria). And a final five were representative of selected Metropolitan Areas in their countries (Sao Paulo in Brazil; Medellin in Colombia; Murcia in Spain; Beijing–Shanghai and Shenzhen in PRC).

Standardised interviewer training and quality control procedures were used in each survey (Pennell et al. Reference Pennell, Mneimneh, Bowers, Chardoul, Wells, Viana, Dinkelmann, Gebler, Florescu, He, Huang, Tomov, Vilagut, Kessler and Ustun2008). Informed consent was obtained before administering interviews. The institutional review boards of the organisations coordinating the surveys approved and monitored compliance with procedures for informed consent and protecting human subjects. Interviews were administered face-to-face by trained lay interviewers in respondents' homes. A total of 138 602 adults (age 18+) completed interviews. The weighted (by sample size) average response rate was 68.7%. To reduce respondent burden, the interview was divided into two parts. Part I, which assessed core mental disorders, was administered to all respondents. Part II, which assessed additional disorders and correlates, was administered to all Part I respondents who met criteria for any Part I disorder plus a probability subsample of other Part I respondents. Part II interviews (n = 74 045), the focus of the current report, were weighted by the inverse of their probabilities of selection into Part II and additionally weighted to adjust samples to match population distributions on the cross-classification of key socio-demographic and geographic variables. Further details about WMH sampling and weighting are available elsewhere (Heeringa et al. Reference Heeringa, Wells, Hubbard, Mneimneh, Chiu, Sampson, Kessler and Üstün2008).

Measures

Mental disorders

Mental disorders were assessed with the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 3.0, (Kessler & Üstün, Reference Kessler and Üstün2004), a fully structured lay-administered interview generating lifetime and 12-month prevalence estimates of 20 mood (major depressive, dysthymic, bipolar I–II and sub-threshold bipolar), anxiety (generalised anxiety, panic, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, post-traumatic stress, and separation anxiety), behaviour (attention-deficit/ hyperactivity, oppositional-defiant, conduct, intermittent explosive) and substance (alcohol and drug abuse, alcohol and drug dependence with abuse) disorders. The WMH interview translation, back-translation and harmonisation protocol required culturally competent bilingual clinicians to review, modify, and approve key phrases describing symptoms (Harkness et al. Reference Harkness, Pennell, Villar, Gebler, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Bilgen, Kessler and Üstün2008). However, no attempt was made to go beyond DSM-IV criteria to assess depression-equivalents that might be unique to the specific countries. The latter expansion might have led to a change in results, although previous research has shown that the latent structure of major depression is quite consistent across countries (Simon et al. Reference Simon, Goldberg, Von Korff and Ustun2002; Bernert et al. Reference Bernert, Matschinger, Alonso, Haro, Brugha and Angermeyer2009; Schrier et al. Reference Schrier, de Wit, Rijmen, Tuinebreijer, Verhoeff, Kupka, Dekker and Beekman2010). Blinded clinical reappraisal interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002) were carried out in four WMH countries. Good concordance was found with diagnoses based on the CIDI (Haro et al. Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, de Girolamo, Guyer, Jin, Lepine, Mazzi, Reneses, Vilagut, Sampson and Kessler2006). AOO was assessed using a special probing sequence shown experimentally to yield more plausible distributions than conventional AOO questions (Knäuper et al. Reference Knäuper, Cannell, Schwarz, Bruce and Kessler1999).

MDD was defined as meeting lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for major depressive episode (MDE) and not meeting lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for broadly defined bipolar disorder (bipolar I–II or sub-threshold). As detailed elsewhere (Merikangas et al. Reference Merikangas, Jin, He, Kessler, Lee, Sampson, Viana, Andrade, Hu, Karam, Ladea, Medina-Mora, Ono, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Wells and Zarkov2011), our definition of sub-threshold bipolar disorder includes both hypomania without history of MDE and sub-threshold hypomania with history of MDE. Anxious MDD is defined as MDD in conjunction with any of the anxiety disorders assessed in the surveys. Comorbid anxiety is considered temporally primary if at least one lifetime anxiety disorder had an AOO earlier than that of MDD. MDD is considered temporally primary if MDD AOO is earlier than that of all lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders. A third category consists of respondents who reported that MDD AOO was the same as anxiety disorder AOO.

Impairment in role functioning

Severe role impairment in the 12 months before interview was assessed with a modified version of the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS; Leon et al. Reference Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber and Sheehan1997) that asked respondents with 12-month MDD to think of the 1 month in the year when their depression was most severe and rate how much their depression interfered with their functioning in each of four role domains (home management, ability to work, social life and close relationships) during that month using a 0–10 response scale with labels of None (0), Mild (1–3), Moderate (4–6), Severe (7–9) and Very Severe (10) interference. Severe role impairment was defined as having any SDS score of 7–10. The SDS has excellent internal consistency reliability (Leon et al. Reference Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber and Sheehan1997) and good concordance with objective measures of role functioning (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Bromet, Burger, Demyttenaere, de Girolamo, Haro, Hwang, Karam, Kawakami, Lepine, Medina-Mora, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Scott, Ustun, Von Korff, Williams, Zhang and Kessler2008). Suicide ideation was assessed with a single question that asked respondents whether there was ever a time in the 12 months before interview when they ‘seriously thought about committing suicide’.

Socio-demographics

We examined associations of MDD with respondent age (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65+), gender, current marital status (married, never married, previously married (combining separated, divorced and widowed)), current income (low, low-average, high-average and high based on country-specific quartiles of gross household income per family member) and education (none, some primary, completed primary, some secondary, completed secondary, some college or other post-secondary and completed college).

Treatment

Respondents with lifetime MDD were asked if they ever obtained professional treatment for their depression and, if so, if they did so in the past 12 months. Those with 12-month treatment were asked if they saw a mental health specialty treatment provider (psychiatrist, psychologist, other mental health professional in any setting, social worker or counsellor in a mental health specialty treatment setting, used a mental health hotline) general medical treatment provider (primary care doctor, other general medical doctor, any other health care profession seen in a general medical setting) or nonmedical treatment provider (religious or spiritual advisor, social worker or counsellor, any other type of healer) for a mental health problem. A more detailed description of WMH 12-month treatment measures is presented elsewhere (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Kessler, Kovess, Lane, Lee, Levinson, Ono, Petukhova, Posada-Villa, Seedat and Wells2007).

Statistical analyses

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI MDD prevalence, the proportions of lifetime and 12-month cases with comorbid DSM-IV anxiety disorders, the proportions of lifetime comorbid cases with anxiety disorder or MDD temporally primary AOO, 12-month prevalence of severe role impairment and suicide ideation related to comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with 12-month MDD, and 12-month MDD treatment as a function of comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with 12-month MDD. Person-level logistic regression was used to examine multivariate associations of socio-demographic variables with lifetime and 12-month MDD in the total sample, lifetime anxious MDD among respondents with lifetime MDD, and 12-month anxious MDD among respondents with 12-month MDD. Time-varying socio-demographics (i.e., marital status, income and education) were defined as of the time of interview (rather than at time of disorder onset). Standard errors were estimated using the Taylor series linearisation method (Wolter, Reference Wolter1985) implemented in the SUDAAN software system (Research Triangle Institute, 2002) to adjust weighting and clustering. Multivariate significance of predictor sets was evaluated using Wald χ 2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance–covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided 0.05-level tests.

Results

Prevalence

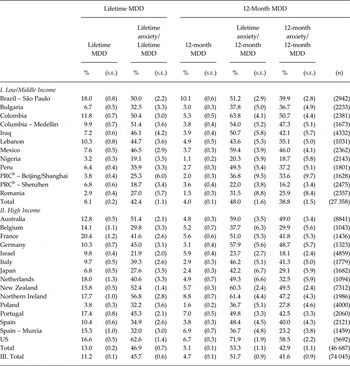

Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI MDD averaged 11.2% across surveys, 8.1% in low/middle-income countries, and 13.0% in high-income countries. (Table 1) The inter-quartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentiles) of lifetime prevalence estimates was 6.8–15.3%. The 45.7% of respondents with lifetime MDD (42.4% in low/middle-income countries, 46.9% in high-income countries, 32.0–46.5% IQR) also had one of more lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI anxiety disorders. A comparison of the ratios of (75th percentile – 25th percentile)/mean shows that lifetime prevalence varied much more across surveys than did the proportion of lifetime cases with lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders (0.75 v. 0.32).

Table 1. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI MDD along with the proportions of respondents with lifetime and 12-month MDD who have comorbid DSM-IV/CIDI anxiety disordersa in the WHO WMH Surveys

aAnxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

bPeople's Republic of China.

Twelve-month MDD prevalence averaged 4.7% across surveys (4.0% in low/middle-income countries, 5.1% in high-income countries, 3.0–5.6 IQR), while 51.7% of respondents with 12-month MDD (48.0% in low/middle-income countries, 53.3% in high-income countries, 37.8–54.0% IQR) also had one or more lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI anxiety disorders. Only slightly lower proportions of respondents with 12-month MDD had 12-month comorbid anxiety disorders (41.6% in the total sample, 38.8% in low/middle-income countries, 42.9% in high-income countries, 29.9–47.2% IQR). As with lifetime prevalence, a comparison of the ratios of (75th percentile – 25th percentile)/mean shows that 12-month prevalence varied more across surveys than did the proportion of 12-month cases with 12-month comorbid anxiety disorders (0.55 v. 0.42).

AOO priorities

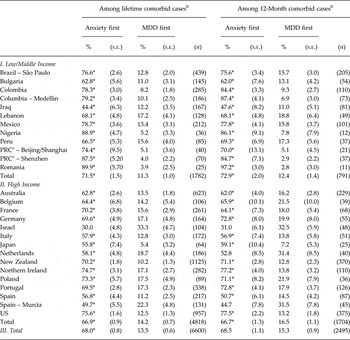

Two-thirds (68.0%) of respondents with lifetime anxious MDD reported first onset of anxiety disorders at earlier ages than MDD (71.5% in low/middle-income countries, 66.9% in high-income countries, 69.6–74.7% IQR), (Table 2) while 13.5% reported earlier AOO of MDD than anxiety disorder (11.3% in low/middle-income countries, 14.2% in high-income countries, 10.2–15.6% IQR) and the remaining 18.5% (17.2% in low/middle-income countries, 18.9% in high-income countries, 10.6–23.7% IQR) reported the same AOO of anxiety disorders and MDD. The dominant temporal priority of anxiety disorders before MDD occurred in all surveys other than in Israel, where the proportions with temporally primary anxiety (30.0%) and MDD (33.3%) were virtually the same (χ 2 1 = 0.2, p = 0.62).

Table 2. Temporal priority in AOO distributions of lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI MDD and anxiety disorders a among respondents with lifetime and 12-month comorbid MDD and anxiety disorders in the WHO WMH Surveys

*Significant difference between the proportion of cases with anxiety temporally primary v. MDD temporally primary at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

aAnxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

bPercentages with MDD first and anxiety first sum to less than 100% because some respondents reported that their MDD and anxiety disorders started at the same age. In cases where respondents had multiple anxiety disorders, earliest AOO was used.

cPeople's Republic of China.

Comparable proportions of respondents reporting temporally primary anxiety disorders were found for 12-month comorbid cases (68.5% in the total sample, 72.9% in low/middle-income countries, 66.7% in high-income countries, 62.0–72.8% IQR), again with the exception of Israel in addition to Murcia in Spain. It is noteworthy that rates of comorbid anxiety disorder among respondents with MDD (reported Table 1) were comparatively low in both Israel and Murcia (21.9–32.0% compared with IQR 32.0–46.5%).

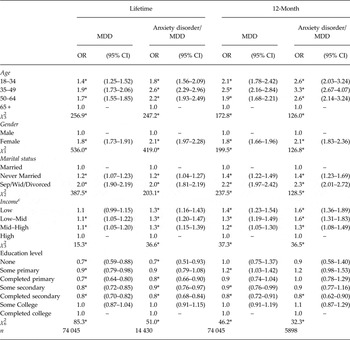

Socio-demographic correlates

Significantly higher rates of lifetime MDD were found among respondents in middle age (ages 35–64) compared with ages 65+ (OR = 1.7–1.9), women compared with men (OR = 1.8), the previously-married compared with currently-married (OR = 2.0), and those with less than high incomes compared with those with high incomes (OR = 1.1). (Table 3) Slightly lower lifetime prevalence of MDD was found among respondents with less than some college education compared with those with at least some college education (OR = 0.7–0.9). Country-specific analyses (available online) showed that the most consistent of these associations were being female (significant in 23 surveys, OR IQR 1.6–2.2) and previously married (significant in 24 surveys, OR IQR 1.8–2.4). The elevated ORs associated with being middle-aged were significant in 13 surveys (OR IQR 1.7–2.9). The associations of income and education with lifetime MDD were inconsistent across surveys.

Table 3. Socio-demographic correlates of lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI MDD and of comorbid anxiety disorders a given MDD in the WHO WMH Surveys b

*Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

aAnxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

bBased on person-level logistic regression models pooled across surveys. Time-varying socio-demographic variables were coded as of time of interview rather than as of AOO.

cIncome was coded within country. Low = less than 50% of the median value of the ratio of before-tax income to number of family members; Low-average = 50–100% of the median value of the ratio of before-tax income to number of family members; High-average = more than 100% to 300% of the median value of the ratio of before-tax income to number of family members; High = more than 300% of the median value of the ratio of before-tax income to number of family members.

Significant associations of these same socio-demographic variables were found with comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with lifetime MDD, but the ORs for age, sex and income were higher than in predicting lifetime MDD: OR = 1.8–2.7 for ages 18–44 compared with 65 + ; OR = 2.1 for women compared with men; and OR = 1.3 for low compared with high income. ORs associated with marital status and education were virtually identical to those predicting lifetime MDD. Country-specific analyses (results available online) showed that the most consistently elevated ORs predicting comorbid anxiety among people with MDD were being female (significant in 22 surveys, OR IQR 1.7–2.7) and previously married (significant in 15 surveys, OR IQR 1.5–2.1). The elevated ORs associated with being middle-aged were significant in 15 surveys (OR IQR 2.1–4.2), while the associations of income and education with lifetime anxious v. non-anxious MDD were inconsistent across surveys.

Socio-demographics were also significantly associated with 12-month MDD. The positive ORs of young age, not being married, low to high-average income, and less than college education were consistently somewhat larger than those of the same predictors with lifetime MDD. The OR associated with female gender, in comparison, was identical in predicting lifetime and 12-month MDD (OR = 1.8), indicating that women did not differ significantly from men in 12-month prevalence among lifetime cases. Broadly similar patterns were also found in predicting 12-month anxious MDD v. non-anxious MDD in that the ORs were all significant as a set (albeit with some ORs for specific education categories not significant even though education was significant overall [χ 2 6 = 32.3, p < 0.001]) and either equal or higher in magnitude than those associated with MDD in the total sample. This means that these socio-demographics were all more strongly associated with persistence of anxious MDD than persistence of non-anxious MDD. The results of more detailed within-country analyses were unstable due to small numbers of cases (results available online).

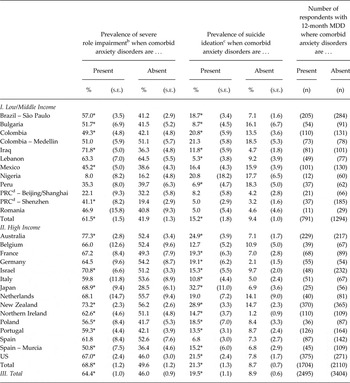

Severity of anxious v. non-anxious MDD

The proportion of respondents with 12-month MDD who reported severe role impairment was significantly higher in the presence (64.4%) than absence (46.0%) of 12-month anxiety disorders (χ 2 1 = 187.0, p < 0.001). (Table 4) Very similar overall patterns were found in low/middle-income countries (61.5% v. 41.9%; χ 2 1 = 97.5, p < 0.001) and high-income countries (68.8% v. 49.6%; χ 2 1 = 128.0, p < 0.001) although the pattern was less consistent in low/middle-income countries (7 of 12 surveys, 6 statistically significant) than high-income countries (all 15 surveys, 10 significant).

Table 4. Two indicators of severity (proportion of cases reporting severe role impairment due to depression and proportion of cases reporting suicide ideation) among respondents with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI MDD depending on presence or absence of comorbid anxiety disorders a in the WHO WMH Surveys

*Significant difference depending on whether comorbid anxiety disorders are present v. absent at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

aAnxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

bRatings of severe or very severe on one or more SDS dimensions in the 1 month in the 12 before interview when the respondent's MDD was most severe.

cAt any time in the 12 months before interview.

dPeople's Republic of China.

The proportion of respondents with 12-month MDD who reported suicide ideation was also significantly higher in the presence (19.5%) than absence (8.9%) of 12-month anxiety disorders (χ 2 1 = 71.6, p < 0.001). Very similar patterns were found in low/middle-income countries (15.2% v. 9.4%; χ 2 1 = 7.9, p = 0.005) and high-income countries (21.3 v. 8.7%; χ 2 1 = 72.8, p < 0.001) overall, although consistency of the pattern was again somewhat lower in low/middle-income countries (9 of 12 surveys, 3 statistically significant) than high-income countries (14 of 15 surveys, 13 significant).

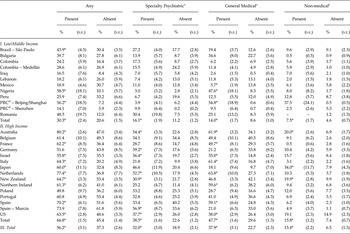

Treatment

Twelve-month treatment of MDD was significantly more common in the presence than absence of 12-month anxiety disorders (56.2% v. 37.3%; χ 2 1 = 21.8, p < 0.001). (Table 5) Very similar relative treatment rates were found in low/middle income (30.3% v. 20.6%; χ 2 1 = 11.7, p < 0.001) and high income (66.8% v. 45.4%; χ 2 1 = 108.8, p < 0.001) countries (i.e., respondents with anxious MDD were roughly 50% more likely to receive treatment than those with non-anxious MDD). However, the absolute difference in treatment rates was much higher in high-income (a 23.4% higher treatment rate of anxious than non-anxious MDD [68.8–45.4%]) than low/middle-income (a 9.7% higher treatment rate of anxious than non-anxious MDD [30.3–20.6%]) countries due to the overall treatment rate being much higher in high income than low/middle-income countries. The pattern of higher treatment of anxious than non-anxious MDD was also more consistent in high-income (all 15 surveys, 10 significant) than low/middle-income (9 of 12 surveys, 3 significant) countries. Similarly significant patterns were found in separate treatment sectors other than the nonmedical sector in low/middle-income countries (χ 2 1 = 4.7–7.5; p = 0.030–0.006) and in all sectors in high-income countries (χ 2 1 = 36.6–77.1; p < 0.001).

Table 5. Treatment of 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI MDD in the presence v. absence of comorbid anxiety disordersa in the WHO WMH Surveysb

*Significant difference depending on whether comorbid anxiety disorders are present v. absent at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

aAnxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

bSee Table 3 for denominator sample sizes.

cSee the text for definitions of specialty, general medical and non-medical treatments.

dPeople's Republic of China.

Discussion

The above results are limited by between-survey differences in response rates and sample frames (most notably, underrepresentation of rural areas in developing countries), diagnoses being based on fully structured lay interviews rather than semi-structured clinician-administered interviews (although available evidence documents good concordance between the two types of diagnoses in WMH; Haro et al. Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, de Girolamo, Guyer, Jin, Lepine, Mazzi, Reneses, Vilagut, Sampson and Kessler2006), the fact that we examined only a summary measure of any DSM-IV anxiety disorder rather than disaggregated disorder-specific measures, and the fact that the WMH surveys were cross-sectional. The latter limitation meant that both lifetime prevalence and AOO were assessed retrospectively. Previous methodological studies (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010; Hamdi & Iacono, Reference Hamdi and Iacono2014; Takayanagi et al. Reference Takayanagi, Spira, Roth, Gallo, Eaton and Mojtabai2014) suggest that use of retrospective recall probably led to underestimation of lifetime prevalence and overestimation of persistence. Long-term prospective studies are needed to resolve this problem.

Within the context of these limitations, we found a relatively narrow IQR across surveys (32.0–46.5%) in estimated rates of lifetime anxiety disorders among people with lifetime MDD, somewhat higher rates but an equally narrow IQR (37.8–54.0%) of lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with 12-month MDD, and only slightly lower rates with a similarly narrow IQR (29.9–47.2%) of 12-month comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with 12-month MDD. The fact that lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders were more prevalent among respondents with 12-month than lifetime MDD suggests that lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders predict MDD persistence, while the fact that 12-month comorbid anxiety disorders were only slightly less prevalent than lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders among respondents with 12-month MDD suggests that anxiety disorder persistence is positively associated with MDD persistence. These patterns are broadly consistent with previous epidemiological studies (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Caraveo-Anduaga, Berglund, Bijl, Dragomericka, Kohn, Keller, Kessler, Kawakami, Kilic, Ustun, Vicente and Wittchen2003; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Petukhova and Zaslavsky2011b ; Lamers et al. Reference Lamers, van Oppen, Comijs, Smit, Spinhoven, van Balkom, Nolen, Zitman, Beekman and Penninx2011). We are unaware, although, of previous studies that examined either the differences we did in the magnitudes of lifetime comorbidity, 12-month comorbidity or comorbidity between lifetime anxiety disorders and 12-month MDD. Our results also go beyond previous studies in documenting considerable cross-national consistency in comorbidity between anxiety disorders and MDD.

The socio-demographic associations documented here are broadly consistent with previous studies in finding higher rates of both anxiety disorders and MDD among women (Parker & Brotchie, Reference Parker and Brotchie2010; Altemus et al. Reference Altemus, Sarvaiya and Neill Epperson2014) and the previously married (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Wells, Angermeyer, Brugha, Bromet, Demyttenaere, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Jin, Karam, Kovess, Lara, Levinson, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Takeshima, Zhang and Kessler2010; Leach et al. Reference Leach, Butterworth, Olesen and Mackinnon2013) along with less consistent inverse associations with age (de Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, ten Have, Tuithof and van Dorsselaer2013; McDowell et al. Reference McDowell, Ryan, Bunting, O'Neill, Alonso, Bruffaerts, de Graaf, Florescu, Vilagut, de Almeida, de Girolamo, Haro, Hinkov, Kovess-Masfety, Matschinger and Tomov2014). However, we are unaware of prior systematic efforts to examine nested associations in the way we did here. It is noteworthy, although, that we did not examine disaggregated associations (e.g., the extent to which socio-demographics predict onset of secondary MDD among people with a history of temporally primary anxiety disorders). The strength and consistency of the associations we documented across nested outcomes suggest that more detailed studies of these specifications might be useful.

Our finding of higher role impairment and suicidality in anxious than non-anxious MDD is broadly consistent with previous findings (Roy-Byrne et al. Reference Roy-Byrne, Stang, Wittchen, Ustun, Walters and Kessler2000; McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, Khandker, Kruzikas and Tummala2006; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Bromet, Burger, Demyttenaere, de Girolamo, Haro, Hwang, Karam, Kawakami, Lepine, Medina-Mora, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Scott, Ustun, Von Korff, Williams, Zhang and Kessler2008), although we showed that this pattern generalises to many more countries than in previous research. We found stronger and more consistent associations of comorbid anxiety disorders with elevated MDD treatment rates in high-income than low/middle-income countries. Previous studies of this pattern, which were limited to high-income Western countries (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Keller and Wittchen2001; Jacobi et al. Reference Jacobi, Wittchen, Holting, Hofler, Pfister, Muller and Lieb2004), found similar associations with those in the high-income WMH Surveys. The overrepresentation of anxious MDD in treatment populations is important because comorbid anxiety disorders predict both low MDD treatment persistence (Shippee et al. Reference Shippee, Rosen, Angstman, Fuentes, DeJesus, Bruce and Williams2014) and low MDD treatment response (Stiles-Shields et al. Reference Stiles-Shields, Kwasny, Cai and Mohr2014).

Our finding that the vast majority of WMH respondents with anxious MDD reported earlier AOO of anxiety disorders than MDD is consistent with previous research in both cross-sectional/retrospective (Kessler, Reference Kessler, Tsuang and Zahner1995; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Ormel, Petukhova, McLaughlin, Green, Russo, Stein, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Haro, Hu, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Matchsinger, Mihaescu-Pintia, Posada-Villa, Sagar and Ustun2011a ) and prospective (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Olivier, Sobol, Monson and Leighton1986; Bittner et al. Reference Bittner, Goodwin, Wittchen, Beesdo, Hofler and Lieb2004; Copeland et al. Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Costello and Angold2009; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Glenn, Kosty, Seeley, Rohde and Lewinsohn2013) samples. The narrow IQR of the proportion of respondents who reported earlier AOO of anxiety disorders than MDD (69.6–74.7%) is especially noteworthy. It is also striking, although, that these proportions are not higher among respondents with 12-month than lifetime comorbidity, as we might expect the latter rates to be higher if temporally primary comorbid anxiety was more important than temporally secondary comorbid anxiety in predicting MDD persistence. We are unaware of any previous research on this distinction. The finding that comorbid anxiety disorder is related to MDD persistence equally whether or not the anxiety is temporally primary might reflect influences of common underlying causes accounting for the lifetime comorbidities of MDD with anxiety disorders, although another possibility consistent with this pattern is that the causal processes accounting for the effects of anxiety disorders on MDD onset differ from the causal processes accounting for the effects of anxiety disorders on MDD persistence. We have no way to adjudicate between these competing possibilities with the WMH data.

If temporally primary anxiety disorders are causal risk factors for MDD, interventions to treat pure anxiety disorders would be expected to reduce subsequent onset of MDD. However, no well-controlled long-term treatment studies have evaluated this possibility despite calls to do so (Flannery-Schroeder, Reference Flannery-Schroeder2006; Garber & Weersing, Reference Garber and Weersing2010). Consistent with this possibility, although, two observational studies based on community epidemiological surveys found that individuals who received treatment for temporally primary panic disorder (Goodwin & Olfson, Reference Goodwin and Olfson2001) and generalised anxiety disorder (Goodwin & Gorman, Reference Goodwin and Gorman2002) were significantly less likely than others with these disorders to go on to develop temporally secondary MDD. Although selection bias into treatment is a possible explanation for these patterns, the most plausible type of selection bias (i.e., selection into treatment based on severity) would be expected to lead to the opposite association with subsequent MDD, arguing indirectly for the possibility that treatment of anxiety disorders might lead to a reduction in risk of subsequent MDD. Other results consistent with this possibility include those from controlled studies of focused psychotherapy for anxiety disorders that showed these treatments reduced concurrent symptoms of MDD (reviewed in Hofmann & Smits, Reference Hofmann and Smits2008; Cuijpers et al. Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Huibers, Berking and Andersson2014), although this result is not entirely consistent (McLean et al. Reference McLean, Woody, Taylor and Koch1998; Woody et al. Reference Woody, McLean, Taylor and Koch1999). In addition, one small controlled study of CBT for social phobia among adolescent girls found that treatment reduced relapse of MDD among patients with a history of comorbid MDD over the subsequent year (Hayward et al. Reference Hayward, Varady, Albano, Thienemann, Henderson and Schatzberg2000).

Despite the suggestive evidence in the above studies, more definitive long-term controlled efficacy trials are needed to evaluate the impact of interventions to treat temporally primary anxiety disorders on the subsequent onset and persistence of MDD. An intriguing observation related to the need for this kind of definitive long-term controlled treatment study is that several epidemiological studies have found distinct risk factors for anxiety disorders that are not risk factors for MDD (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, Milne, Melchior, Goldberg and Poulton2007; Beesdo et al. Reference Beesdo, Pine, Lieb and Wittchen2010; Mathew et al. Reference Mathew, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Roberts2011; Asselmann et al. Reference Asselmann, Wittchen, Lieb, Hofler and Beesdo-Baum2015). For example, an extensive literature shows that stressful life events associated with danger predict anxiety but not depression (Finlay-Jones & Brown, Reference Finlay-Jones and Brown1981; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner and Prescott2003; Asselmann et al. Reference Asselmann, Wittchen, Lieb, Hofler and Beesdo-Baum2015). This specificity should not exist if anxiety disorders caused MDD, as the latter causal process would lead to attenuated associations of the risk factors with MDD. To find that this is not the case suggests that something more complex is at work linking anxiety disorders with MDD and that common causes are involved in the comorbidity of anxiety disorders with MDD.

The existence of common causes would impose an upper bound on how much secondary MDD could be prevented by successful treatment of temporally primary anxiety disorders. Common causes might also help account for the fact that concurrent comorbidity is associated with poor treatment response for both anxiety disorders (Rapee et al. Reference Rapee, Lyneham, Hudson, Kangas, Wuthrich and Schniering2013; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Jakubovski and Bloch2014) and MDD (Jakubovski & Bloch, Reference Jakubovski and Bloch2014; Saveanu et al. Reference Saveanu, Etkin, Duchemin, Goldstein-Piekarski, Gyurak, Debattista, Schatzberg, Sood, Day, Palmer, Rekshan, Gordon, Rush and Williams2014). Less is known, although, about the associations of lifetime comorbidity with treatment response among patients who do not have concurrent comorbid symptoms. An examination of this specification would be useful in helping distinguish differential treatment response associated with the amelioration of life stressors surrounding particular anxious-MDD episodes and risk factors associated with more fundamental causes of lifetime anxious-MDD.

The latter suggestion highlights the fact that little research has attempting to distinguish the determinants of first onsets from the determinants of the subsequent course of either anxiety disorders or MDD. Virtually all the research cited above on the association between treating anxiety disorders and subsequent change in depression as well as on the associations of comorbidity with differential treatment response implicitly focused on the course of depression, as only a small minority of MDD cases in clinical studies are first-onset cases. As noted above, it is quite possible that different processes are at work in bringing about lifetime comorbidity and episode comorbidity. Research is needed to investigate such differences explicitly.

It is noteworthy in this regard that epidemiological research assuming the existence of common causes has shown that the coefficients describing the cross-lagged prospective associations of temporally primary lifetime anxiety with subsequent first lifetime onset of MDD and vice versa can be parsimoniously described by assuming a latent intervening predisposition to all internalising disorders (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Ormel, Petukhova, McLaughlin, Green, Russo, Stein, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Haro, Hu, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Matchsinger, Mihaescu-Pintia, Posada-Villa, Sagar and Ustun2011a , Reference Kessler, Petukhova and Zaslavsky b ). Although some hypotheses have been advanced for asymmetries in these associations (Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Caporino and Kendall2014), available evidence suggests that these asymmetries are weak. If this model is accurate, then temporally primary lifetime anxiety disorders might be risk markers rather than causal risk factors for the subsequent first onset of lifetime MDD even though anxiety disorders might have causal effects on the subsequent persistence of MDD. If this is the case, then successful intervention to treat early-onset primary anxiety disorders might not prevent the subsequent first onset of MDD even though it would reduce MDD persistence. A more consistent distinction between lifetime and concurrent comorbidity needs to be made in future observational and clinical studies of anxious MDD to shed light on these possibilities. As part of this increased focus, any attempt to carry out long-term controlled treatment studies to evaluate the effects of treating temporally primary anxiety on subsequent MDD should be designed to have a sufficiently large sample size and a sufficient duration of follow-up to examine effects on both MDD onset and MDD persistence and to include an assessment of plausible biomarkers. Our understanding of the causal determinants of the high comorbidity of MDD with anxiety disorders will remain at its current relatively primitive level until studies of this sort are carried out.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the helpful contributions to WMH of Herbert Matschinger, PhD.

Financial Support

The WMH surveys were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Shire. The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by the State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3. The Bulgarian Epidemiological Study of common mental disorders EPIBUL is supported by the Ministry of Health and the National Center for Public Health Protection. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. The Shenzhen Mental Health Survey is supported by the Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The WMHI was funded by WHO (India) and helped by Dr R Chandrasekaran, JIPMER. Implementation of the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS) and data entry were carried out by the staff of the Iraqi MOH and MOP with direct support from the Iraqi IMHS team with funding from both the Japanese and European Funds through United Nations Development Group Iraq Trust Fund (UNDG ITF). The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), Fogarty International, Act for Lebanon, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council and the Health Research Council. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The Romania WMH study projects ‘Policies in Mental Health Area’ and ‘National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use’ were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC. Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The EZOP – Poland (Epidemiology of Mental Disorders and Access to Care) survey was supported by the grant from the EAA/Norwegian Financial Mechanisms as well as by the Polish Ministry of Health). The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Statement of Interest

In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sonofi-Aventis Groupe. Dr Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and U.S. Preventive Medicine. Dr Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc. Dr Wilcox is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supplementary materials and methods

The supplementary materials referred to in this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015000189