Introduction

How do people encounter misinformation through storytelling in their everyday lives during a pandemic? This chapter focuses on the dynamics of storytelling in misinformation as a problematic aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic in three cases of misinformation storytelling. Storytelling offers a framework for researching collective experiences of information as a process that is inherently based in communities, with knowledge commons that are instantiated by the telling and retelling of stories, temporarily or permanently. To understand how difficult information is to govern in story form and through storytelling dynamics, this chapter uses new storytelling theory to explore three recent cases of COVID-19 misinformation related to drug misuse, exploiting vaccine hesitancy, and community wisdom in resisting medical racism. Understanding what goes wrong with these stories may be key to public health communications that engage effectively with communities’ everyday misinformation challenges.

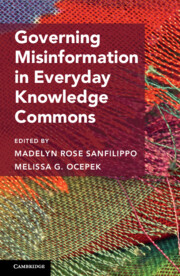

Figure 2.1 Visual themes from storytelling and/as misinformation: storytelling dynamics and narrative structures for three cases of COVID-19 viral misinformation.

Introduction as Story

Another way of introducing this chapter is to compare two historical stories of community experiences related to health and medicine. The first story comes from my family. My mother heard a story from her grandmother about being a young mother herself during the 1918 influenza epidemic, when the whole household came down with the flu. Her parents (my great-great-grandparents) left food on the porch and visited through an open window, using much the same “social distancing” practices in Wetumpka, Alabama in 1918 as in the COVID-19 pandemic today. The wisdom of these practices left an impression, and she recognized them immediately when they were called into use globally once again in spring of 2020. Continuity of stories in families can provide a kind of storytelling wisdom that accompanies the stories we inherit (McDowell Reference McDowell2021).

Also in Alabama, fourteen years later and 51 miles away in Tuskegee, the US Public Health Service launched the Tuskegee Syphillis study in 1932. The history of this study involves racism, torture, and genocidal practices against Black men who were unknowingly subjects of untreated syphilis infections. For human subjects researchers, this history is repeated at every basic Institutional Review Board (IRB) training, and this unethical study is one of the main reasons for the 1974 National Research Act, which requires “voluntary informed consent” from all human research subjects (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021). Families who experienced the pain, suffering, and in many cases the death of their loved ones later learned that they had gone untreated because of deception, as a “scientific” experiment. Here as well, information was inherited in the form of storytelling wisdom and mistrust of federal medical programs.

Communities that have been subjected to this and other kinds of systemic persecution are reasonably skeptical of new health interventions. When medicine enacts genocide, it does terrible damage at the level of the commons, with impacts for generations to come, and this is only one story in a larger history of federally supported medical racism. The resistance of communities impacted should be seen not as an information problem, but as historical and storytelling-informed wisdom. After histories like these, people react “not with defensiveness, but with comprehension” (Howell Reference Howell and Duffin2005, 221). The routine misunderstandings of medical professionals deepen the harm. When current medical programs ignore or dismiss the wisdom of community survival, they commit an act of epistemcide, defined as the “killing, silencing, annihilation, or devaluing of a knowledge system” (Patin et al. Reference Patin, Sebastian, Yeon, Bertolini and Grimm2021b).

In cases like these and many more, storytelling can yield theoretical insights into commons governance of shared knowledge and the tragedy of misinformation, information, and shared wisdom. Storytelling is an informal and yet ubiquitous means of information circulation. This chapter focuses on the case of storytelling and retelling of misinformation as a problematic aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic through an infodemics lens. Misinformation is false, inaccurate, misleading, or decontextualized so that it misinforms audiences, with strong similarities to disinformation which is designed to misinform or mislead, and malinformation which is intended to cause harm (Wardle and Derakhshan Reference Wardle and Derakhshan2017). Infodemiology is the study of surges of information (including misinformation) that lead to confusion and risk during public health crises (Mavragani Reference Mavragani2020). Put another way, “an infodemic is an overflow of information of varying quality that surges across digital and physical environments during an acute public health event. It leads to confusion, risk-taking, and behaviors that can harm health and lead to erosion of trust in health authorities and public health responses” (Calleja et al. Reference Calleja, AbdAllah and Anoko2021, 2). Infodemic issues related to COVID-19 are the focus here, but nonetheless they serve as just one kind of theorizing storytelling as an everyday means of information circulation. Understanding both the dynamics of storytelling and how they produce stories can help to identify what has gone wrong in infodemic contexts.

Efforts to address complex social issues require understandings of storytelling and retelling as a fundamental process of everyday information circulation. This chapter uses two storytelling theory frameworks to analyze three cases: medicine misuse, exploiting vaccine hesitancy, and aftermath of medical racism. Understanding what goes wrong with these stories may be key to public health communications that engage effectively with communities’ everyday misinformation challenges.

Literature Review

Storytelling

Story is a fundamental information form that has been overlooked in the information sciences (IS), although it has a rich history of over 130 years of practice in library and information science (LIS) in youth services and librarianship (Agosto Reference Agosto2016; Bishop and Kimball Reference Bishop and Kimball2006; Colón-Aguirre Reference Colón-Aguirre2015; Del Negro Reference Del Negro2017; Hearne Reference Hearne1999; Sturm and Nelson Reference Sturm and Nelson2016). Storytelling is central to understanding social, collective, and community meaning-making because it intertwines informational and emotional elements. It is also a strong vantage point from which to engage everyday information epistemology and knowledge commons. IS as a field tends to swing like a pendulum between the implicit positivism of the computational and the social constructionism of humanistic approaches, but storytelling (as well as everyday information and knowledge commons) requires an epistemology that bridges these divides. Storytelling dynamics produce stories that inform while being deeply contextually relevant. “In story, wisdom often means discovering a way beyond the ways that seem obvious” (McDowell Reference McDowell and Miller2021). Of course, other human cultural and wisdom traditions are interwoven with storytelling practices that have lasted much longer, and both fields have “neglected to treat people as epistemic agents who are embedded in cultures, social relations, and identities” (Patin et al. Reference Patin, Oliphant and Lar‐Son2021a)

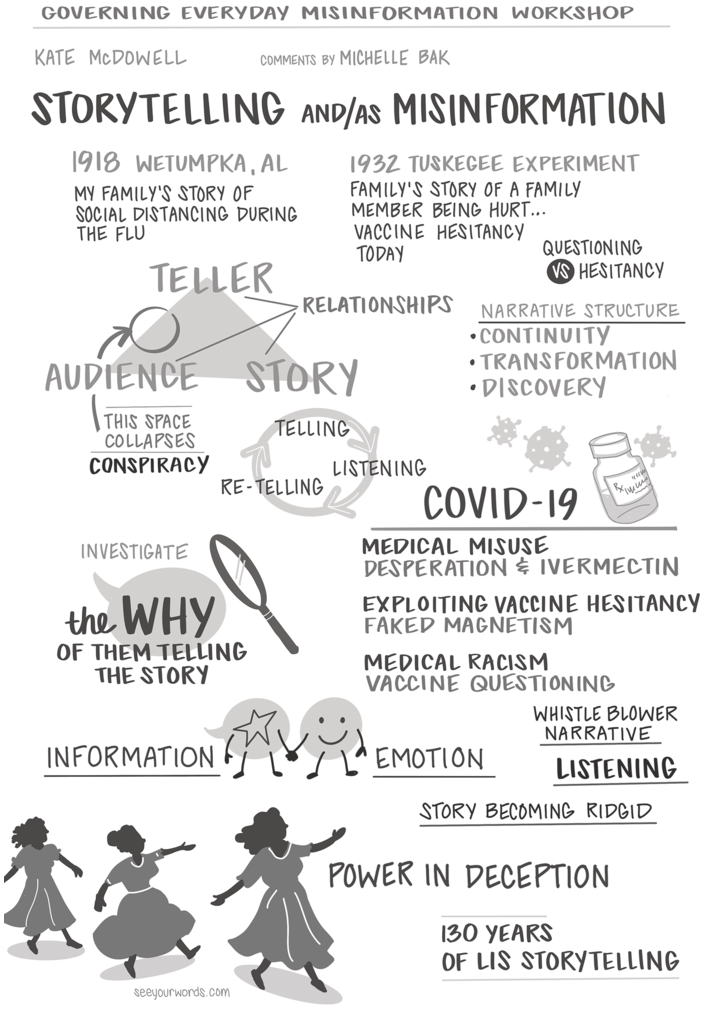

Storytelling is here defined as telling a story within the dynamic triangle of the story, the teller, and the audience. Whether permanent familial relationships or temporary relationships among strangers at a shared event, the story emerges in the connection between the teller and the audience. Storytelling roles in a culture include who may tell as story as well as who is not permitted to tell or hear a story, as in cases of indigenous cultures encountering folklorists who are allowed to study a tradition but asked to destroy recorded stories (Toelken Reference Toelken1998).

Storytelling may be necessary to bridge divides between indigenous epistemologies and science, as Kimmerer demonstrates in her use of standard scientific paper headings to tell the story of a doctoral student who demonstrated that, contrary to most of her committee’s beliefs, harvesting does not have to damage sweetgrass; indigenous knowledge of symbiotic harvesting stimulated more vigorous growth (Kimmerer Reference Kimmerer2013). The stories of indigenous lives in the Americas have been difficult to tell because of these and other limiting academic beliefs. In her article establishing the “importance of felt experiences as community knowledges,” Million writes:

The mainstream white society read Native stories through thick pathology narratives. Yet the same stories collectively witnessed the social violence that was and is colonialism’s heart. Individually or collectively, these stories were hard to “tell.” They were neither emotionally easy nor communally acceptable. Women (and men) who organized against family violence and politically sanctioned sex discrimination in their communities balanced the necessity to change things and constraints to “silence” their pain and experience. To “tell” called for a reevaluation of reservation and reserve beliefs about what was appropriate to say about your own family, your community.

All academic disciplines and endeavors have been formed around, absorbed, continued, and reified these storytelling inequities. As have science and political science, “LIS has undermined knowledge systems falling outside of Western traditions” (Patin et al. Reference Patin, Oliphant and Lar‐Son2021a).

And yet the LIS tradition of storytelling as a dynamic relationship and process holds within it the possibility of a different kind of listening. In the storytelling triangle, the audience’s relationship to the teller hinges in part on how they understand the teller’s own relationship to the story as well as which story the teller chooses to tell that audience (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 The storytelling triangle. Courtesy of Hilary Pope, artcoopshop.com.

For storytelling to occur, some trust must exist between the teller and the audience. This trust is contextual and depends on demonstrating that the teller wants this audience to know this story. Whether a story is received as worthy of believing and retelling depends in part upon this trust. Second, the teller has a relationship to the story, whether as creator or reteller. The storyteller (and audience) cannot be neutral as they inevitably inhabit a worldview. Third, the audience has a relationship to the story, primarily through their interpretation. That relationship is informed by everything the teller says (gestures, performs, writes, records, etc.) in the course of telling the story and much more. The audience’s interpretation can influence the meaning of the story for the teller as well, through listening to collective responses. Audiences interpret stories as groups, creating socially constructed meanings in the moment and sustaining cultural meanings over long spans of time. Retellings demonstrate how a story can be told so that others also recall and retell, and the story persists and moves on.

Storytelling has been studied extensively in other contexts, including organizations, with a strong emphasis on its role in creating and sustaining organizational cultures (Boje Reference Boje2008; Denning Reference Denning2011; Marek Reference Marek2011). It has also been mobilized in counter-narrative contexts, as an important part of the process of hearing silenced voices and diversifying LIS (Cooke Reference Cooke2016). However, it is important to consider that storytelling is also a powerful noninstitutional information conduit. It is ubiquitous, flexible, and difficult to track. Folklore studies offer some insights into why this is. When considering the dynamics of folklore, retellings or reiterations of folk traditions are always simultaneously governed by cultural norms and inventive. “We may say that folklore itself is characterized by (1) certain cultural rules that determine strongly what gets articulated and how and when, and (2) by a looseness, an informality, an inclination toward rephrasing and change” (Toelken Reference Toelken1979, 31).

Storytelling and Commons

Storytelling relates to ideas of knowledge commons as resources. Stories are circulated through telling and retelling, carrying implicit cultural knowledge, and yet the specific form that a story takes depends on the teller, the audience, and the relationships between them. The cultural rules of a folk community swapping stories relate to the concept of knowledge commons, which “refers to an approach (commons) to governing the management or production of a particular type of resource (knowledge).” Commons is the institutional arrangement of resources in relation to a community, and knowledge means “cultural, intellectual, scientific, and social resources (and resource systems) that we inherit, use, experience, interact with, change, and pass on to future generations” (Frishmann et al. Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014). Storytelling offers a framework for researching collective experiences of information as a process that is inherently based in communities. However, stories circulate in ways that may make it challenging to clearly identify the commons, readily crossing boundaries implied by institutional arrangements. While stories do not require specific locations to circulate, their circulation relates to the concept of “inherently public property” (Rose Reference Rose1986). Stories that have been retold again and again – from urban legends to cautionary tales to jokes – with no identifiable origin (or endpoint) may seem to belong to everyone who repeats them and no one at the same time. Storytelling, as defined in the library tradition, is cooperation that operates in a cultural context of public service.

Storytelling is also fundamental to the coproduction of community and of commons themselves. Communities build around stories of who we are, of what we share, and stories are ways of building, determining, and discerning who belongs within a particular commons. Storytelling is present in “remember when” recollections or “that’s not how it happened” arguments among community members. Negotiating, repeating, celebrating, or bickering over stories and the realities they represent occur routinely, in both formal and informal ways, in a community that shares a commons. In some sense a community’s stories are not just a part of its commons, they are simultaneously the signs of its borders and the production and property of its participants.

There is a productive contrast to be made between LIS storytelling and stand-up comedy. Some aspects are similar to storytelling, including the need for the audience: “a joke is only as good as its ability to make audiences laugh, which can only be gauged through public performance” (Bolles Reference Bolles2011, 241–242). However, LIS storytelling is predicated on retelling adaptations of folktales that are in the public domain (with multiple print versions) and are shared as original and spontaneous (transformative) adaptations in educational settings, and so rely on fair use. By contrast, as recent cases of “joke theft” have shown, stand-up comedy jokes and routines can be protected as intellectual property, such that “two entertainers can tell the same joke, but neither entertainer can use the other’s combination of words” (239).

Folklorist and acclaimed librarian storyteller Betsy Hearne lauded the aesthetics of folkloric stories, with their “fast-moving, highly structured elemental plots” and “clearly delineated archetypal characters,” for allowing each listener “to glean different emotional, socio-cultural, intellectual, spiritual, and physical connections with a tale” (Hearne Reference Hearne2011, 214). In the LIS storytelling tradition, staying true to the story means capturing its essence while telling it anew, emphasizing spontaneous expression in service of the audience. Early children’s librarians underwent rigorous training for storytelling, practicing in front of mirrors (Shedlock Reference Shedlock1915, 144), to learn their stories aurally, or through imagery, but not to memorize the words. Augusta Baker, the first to hold the position of Storytelling Specialist at the New York Public Library, directed new storytellers to emphasize “the story rather than upon the storyteller, who is, for the time being, simply a vehicle through which the beauty and wisdom and humor of the story comes to the listeners” (Baker and Greene, Reference Baker and Greene1977, 58).

In LIS storytelling and other areas, knowledge commons can be enriched by use rather than depleted, as each retelling creates an original adaptation in the moment. Similar enrichment of commons is found in much longer cultural traditions. For example, in describing indigenous knowledge, Joranson proposes looking “inside the commons” to see that there is an understanding of knowledge “that does not become depleted through use.” “As we continue to develop language to describe the knowledge commons, it is important to explore language that does not keep these resources in opposition or as separate, but makes their mutuality visible” (Joranson Reference Joranson2008, 70–71). In the same way, stories are not depleted by LIS storytelling, but instead may grow richer with retelling over time. When tales are consensually swapped (and not stolen from one culture by another), there may in fact be continual renewal and replenishment of the commons.

There are more reasons to be interested in story and storytelling as simultaneously informational and emotional processes based on recent research from other fields. For example, recent neurological research finds that neural story processing involves “mirroring process of embodied subjectivity” or experiences of “narrative emotions” predicated upon story’s “ability to intertwine our experience of time” (Armstrong Reference Armstrong2020). Specialized “mirror neurons” in the brain contribute to experiencing empathy through story (Rizzolatti Reference Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia2008), and contextual empathy cues increase the potential for empathetic experience through story (Roshanaei et al. Reference Roshanaei, Tran, Morelli, Caragea and Zheleva2019).

Storytelling as Methodology and Metaphor

Epistemologically and methodologically, storytelling is a fruitful metaphor for the commons in our time. In our physical, virtual, and hybrid worlds, an exchange of story can take place anywhere, and the retelling of a story may change (enhance or degrade) its content; there is no shortage of story created by the use or reuse of story. Baker emphasized that “storytelling at its best is mutual creation.” (Baker and Greene Reference Baker and Greene1977, xii). This focus on relationships is key to understanding storytelling dynamics. Because stories are constituted through narrative experience, and audiences are partly constitutive of the stories told to and with them, storytelling offers a framework for researching collective experiences of information as a process. To understand infodemics, for example, we need nuanced competencies to unpack and understand misinformation. The following section define storytelling dynamics and narrative structures that are key to understanding misinformation storytelling.

Engaging storytelling can help to reveal “how individuals really interact with information on a fundamental level,” by prodding us to “look to the relationship individuals have with information.” Part of that relationship entails when an individual is part of an audience, when they are listening to a storyteller, and how each story emerges as an aspect of that relationship. In considering everyday life information behavior Ocepek (Reference Ocepek2018) urges scholars to look to “narrative, lived experience, and other non-traditional forms of information as valuable resources and means for understanding everyday life” (404–405). Storytelling dynamics are critical to making sense of how people use and experience information, but they are not the only important aspect. Equally important is a fundamental understanding of story as information in narrative structures.

Storytelling Narrative Structures

Narrative structures are story patterns, and their recurrence across eons of time and multiple human cultures signal their robustness for simultaneously conveying information and emotion in story form. Their persistence demonstrates what has worked with audiences previously. Based on a broad overview of narratology and related narrative theories, three simple and relatively intuitive structures were developed and refined over eight years of workshops and teaching, with input from audiences through discussion and interviews (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Narrative structures

| Narrative structure | Emotional impact | Originating theory |

|---|---|---|

| Continuity | Stability and resilience despite challenges, reassurance of continuity | Tsvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic, and the story “The Stonecutter” by Andrew Lang, attributed as Japanese but actually Dutch in origin |

| Transformation | Awe at transformation, joy of watching a hero triumph | Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces |

| Discovery | Mystery, suspense, intrigue, and satisfaction of coming to understanding | Roland Barthes’ hermeneutic or enigma code, one of five semiotic codes in S/Z |

The continuity narrative structure is about cycles, journeys from stability to disruption and on to a new stability. The emotional impact of the equilibrium structure is resilience or stability despite challenge. This structure is often useful for stories about rebuilding and reorganizing in order to sustain continuity. For example, when antivax rhetoric surges in an infodemic, stories about the history, invention, and successes of vaccines and vaccination campaigns communicate that, despite challenges and change, the practice of vaccination evolves and endures (Lang Reference Lang1903, 192–197; Sturm Reference Sturm2008; Todorov Reference Todorov2004).

In the transformation structure, based on the hero’s journey, a protagonist encounters obstacles and is transformed b the process of overcoming them (Campbell Reference Campbell1949). This structure conveys a feeling of awe at the hero’s triumph over obstacles, but it is not a universal structure and should be used with caution, because self-aggrandizing stories can backfire and risk losing the audience’s interest or trust. In an infodemic context, this structure characterizes the global transformation from the pandemic of COVID-19 to the availability of effective vaccines.

The discovery narrative structure comes from the hermeneutic or enigma code, which is one of five codes defined by Roland Barthes that define ways that meaning drives a narrative (Barthes Reference Barthes1970). The discovery narrative structure is a recurring cycle of suspense and discovery, intrigue and information, curiosity and satisfaction. Emotionally, it is like a mystery story, where the audience follows the investigation of a detective-as-narrator in coming to understand what happened, why, and how things could be different. The story of Alexander Fleming’s discovery of a mold that killed bacteria to the development of penicillin is a classic discovery narrative.

Although story plots often communicate causality, they also elide strict definitions of causality, and in fact the plot of a story may range from true causation to loose correlations in story sequence. In an aspect of confabulation, events that do not constitute fully causal explanations can seem to be associated in a story plot. Because narrative structures are flexible, any of these structures can be used to make compelling stories, whether true or confabulated or someplace in between.

Where Storytelling Goes Wrong: COVID-19 Misinformation

Some of the most complex issues related to social justice, civil rights, racism, and more have been understood as relating to storytelling and narrative (Bell Reference Bell2010; Polletta Reference Polletta2006). Victims of misinformation may lack resources to fact-check the stories they hear. Even if they can fact-check, they may not be able to describe the emotional effects of an infodemic, which may be, as Million says, “hard to ‘tell’.” Many people – from the most vulnerable populations to the most accomplished social scientists – have needed time to understand the social media disinformation strategies at play in confusing and disorienting audiences to create even more vulnerability.

We know very well in these times that stories that are retold and believed by millions of people are not always true. People want to understand the world around them, and that desire is so strong that, when things don’t fit, human brains confabulate, finding and making stories out of whatever is available. Some psychological experiments have revealed that confabulation can be reinforced, so that participants develop false memories (Zaragoza et al. Reference McDowell2021). Storytelling dynamics may, in some cases, increase the propensity to share misinformation. The COVID-19 infodemic has brought new ways of understanding misinformation and its harms (Hansson et al. Reference Hansson, Orru and Pigrée2021). Further research is needed.

The present analysis focuses on understanding how storytelling dynamics (relationships between teller, audience, story) and narrative structures (continuity, transformation, discovery) play out in three example cases of misinformation. While each of these three examples – medicine misuse, exploiting vaccine hesitancy, and aftermath of medical racism – could be studied (and in some cases, have been) with a focus on social media, taking a storytelling approach offers some fresh insights about what goes wrong. The predominance of methods using metric analysis of shares (likes, retweets, etc.) has a tendency to obscure the ways that individuals frequently share misinformation as storytellers, adding their own comments, captions, messages, and more. In this sense, as storytellers, they repeat misinformation from their own point of view and tailor misinformation to their audiences. Sometimes the false or wrong information is amplified in content or in emotional urgency through these processes. While understanding the metric magnitude of viral misinformation is important, so too is understanding the qualitative aspects that speak to how and why specific tellers and audiences engage in listening to and retelling misinforming stories. Some misinformation may not be in strict narrative form, but it is part of a narrative experience – whether accurately explanatory or confabulatory – which is how storytelling operates in everyday life, and it evokes and invites story making. The same dynamics of surprise or outrage that lead to shares or retweets operate around the (now perhaps fabled) workplace watercooler, with the “you’ll never believe this” stories. And audiences may lack the resources – time, access to peer-reviewed literature, knowledge, and more – to fully investigate whether something is true themselves, which may compound the spread and harms of misinformation.

In considering storytelling dynamics and narrative structures, it is important to establish a way of accounting for storytelling and/as information. This refinement of the previously published S-DIKW framework provides a tool for this analysis. Storytelling is here conceptualized as a set of abilities that relate to various levels of the DIKW hierarchy. Rather than each level being a descriptor, in the S-DIKW framework each level relates to human abilities to derive stories from data, to interpret data with context as information stories, to take action based on those information stories, and to enact wisdom in the selection of stories. (McDowell Reference McDowell and Miller2021)

S-Data Basis of information in story

S-Information Data interpretation with context as story

S-Knowledge Actionable information in story

S-Wisdom Which story to tell when, how, to whom, and more

It is important to distinguish between the broader definition of knowledge as a defining element of knowledge commons and s-knowledge as used here, which is derived from the narrower definition in the DIKW framework of actionable information (Rowley Reference Rowley2007). In relation to S-Wisdom, this definition is likely only partial, but provides a launching point for information fields to more actively and deliberately grapple with wisdom as a concept.

Storytelling analysis, then, can shed light on misinformation examples by (1) analyzing the relationships between teller, audience, and story, and (2) exploring what narrative structures are used to shape the meaning of the story. In the three examples that follow, a combination of these approaches helps to unpack how storytelling went wrong in three viral stories that exemplify various aspects of the COVID-19 infodemic.

Medicine Misuse: Desperation and Ivermectin

In fall of 2021, more than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, stories about Ivermectin as a possible treatment circulated rapidly. This occurred at a point when it was still too early to tell whether it would be an effective COVID treatment, a speculation which clinical trials later disproved. Ivermectin was readily available at stores that sold veterinary supplies, since it is commonly used to treat parasites such as heartworms in dogs and worms and other parasites in livestock. Unfortunately, this misuse of medicine, particularly in horse-sized doses, led to both human illnesses and a temporary shortage of this previously common veterinary medication.

Unlike other drugs that are difficult to obtain without prescription, Ivermectin was commonly available and well known to veterinarians and animal caretakers who work with horses. Storytellers who retold, shared, tweeted, and otherwise spread this misinformation were, at best, helpless and willing to try anything available due to widespread panic. At worst, they were exploiting this panic to sell a “treatment” that was worthless or harmful or to boost their metrics on social media. In many cases, this story was retold as part of conspiracy theories. Tellers falsely claimed that they were engaged in righteous revelation of “the truth” from those “in power” who were hiding it. This “what they’re not telling you” rhetoric is a recognizable aspect of populist rhetoric, which uses digital media to “stage intense dramas of dark forces and brave rebels fighting against them, led by charismatic rhetoricians revealing secrets and telling truths” (Finlayson Reference Finlayson, Kock and Villadsen2022, 82). For audiences, this rhetoric further heightens reactivity, enlists them as “truth-tellers” who are actually spreading misinformation, and contributes to the rapid circulation of fake stories online.

From a narrative structure perspective, this kind of story engages both transformation and discovery. As a transformation story, the teller is promoting themselves as a truth-telling “hero,” overcoming purported obstacles of “them” who don’t want “you/us” to know – albeit one who gives no evidence of who the mysterious “them” might be that are trying to hide the truth. Audiences are readily swept up in the sense of drama, which might connect to their own senses of isolation or victimization, hoping that a populist hero will save them. Information literacy approaches might consider adding to the usual questions about authority and authoritativeness something more specific about teller–audience dynamics, such that audiences are encouraged to look for these rhetorical heroics as a cue to be skeptical of the associated information.

This rhetoric also amplifies fear that audiences are excluded from knowing that a disease treatment has been discovered. Purporting to be a discovery narrative, this trope of revealing something everyday with unexpected and hidden uses is familiar online, where household tips abound for the use of everyday substances for other purposes. Unfortunately, some of these “tips” are toxic. For example, in May 2022, viral TikTok videos promoted a “tip” storing avocados in water to make them last longer, which prompted the United States Food and Drug Administration to issue a warning against the practice (Fowler Reference Fowler2022). More broadly, the discovery narrative is familiar from so many stories of scientific advancement, from the discovery of penicillin to trips to the moon. From an information storytelling perspective, we might ask why are these stories of a cure – right in front of our noses but simultaneously hidden – so compelling? This may be related to brands which market themselves as “exclusive” or with “secret ingredients,” and why behind-the-scenes stories are so compelling in marketing and fundraising (McDowell and Miller Reference McDowell and Miller2021). When considering knowledge commons, it is important to consider what might defuse the intensity associated with this aura of mystery.

Exploiting Vaccine Hesitancy: Faked Magnetism

In summer of 2021, a number of stories went viral about another purported mystery, a claim of causality between magnetism and vaccination. Specifically, rumors abounded that vaccines contained metals, microchips, or other substances that caused the human body to become magnetic at the site of the vaccination injection. Some people even produced video “evidence” that vaccinations caused bodily magnetism. These videos were bogus and scientifically laughable, and yet they tapped directly into audiences’ fears of negative vaccine side-effects.

Deceptive YouTubers bumped up their metrics with likes, shares, and follows with video theatrics showing metal “sticking” to their skin where they were vaccinated. Audiences already primed by fears of a global pandemic and the complex conglomeration of safety concerns that it brought were especially vulnerable to these manipulations. At best, such videos were confabulation or delusion from antivaccination (antivax) perspectives; extensions of conspiracy theories about vaccination. At worst, they were performances that deliberately shocked audiences with false information and magic tricks of simple visual deception. Audiences in this context operate as social media currency, meant to spread this story because of its shock value. At the same time, the potential negative impact of this deception took on greater weight with the rapid spread of COVID and clear evidence that vaccines save lives.

Conspiracy theories present an intriguing set of dynamics from a storytelling perspective. First, tellers and audiences quickly become locked into an ever-increasing set of interrelated stories with an ever-narrowing window for contrary evidence. If audiences trust the source and are shocked or otherwise emotionally activated by the story, they are more likely to retell it. Over time, the tight connection between teller and audience inside this trust widens into a gap between insider audiences who share beliefs and anyone else as outsiders. Conspiracy theories become a system of stories through which tellers and audiences focus on a limited set of information, confirming each other’s perspectives to the complete exclusion of any contrary evidence or interpretation.

From a narrative structure standpoint, this is most like a continuity story, in that the underlying message is to focus on maintaining the status quo despite disruption, in the COVID-19 case from a global pandemic. The implied argument is to rely on “natural immunity” rather than vaccination, to resist public health and governmental guidelines and treat them as part of the problem rather than part of the solution. At the same time, oversimplified public health rhetoric has tended to elide the complexities of vaccination. Yes, there were (and are) side effects of vaccination, and with a new vaccine not all side effects are immediately known (or knowable). When so much is unknown, storytellers readily confabulate, and those confabulations become stories that feed into conspiracy theories and faked performances.

Aftermath of Medical Racism: Vaccine Questioning

Many studies have now shown that COVID-19 vaccines were met by significant hesitancy even by those who are not generally opposed to vaccination, and that disproportionately, communities of people of color were more likely to pause before seeking vaccination. For example, as documented in a fall 2021 report, “in most states where data is available, Black people are receiving a smaller percentage of vaccines relative to their overall population, despite them accounting for a much larger share of COVID-19 deaths” (Dodson et al. Reference McDowell2021). This pervasive mistrust has been termed “vaccine hesitancy,” but the term hesitancy is incomplete at best and misleading at worst. Like so many terms, it is decontextualized from the broader history of the United States.

It is vital to consider, from a storytelling perspective, what inherited information resulting from traumatic medical racism might mean for everyday information behavior. If two storytellers present contradictory stories, the factor of trust between teller and audience can tip the balance one way or the other. For the survivors of the victims of the Tuskegee atrocities, for example, the federal government and public health authorities that are the direct successors to the authorities that killed and tortured their relatives might not be trustworthy, to put it mildly. For their families, relatives who survived these atrocities would likely be more trustworthy than public health officials. BIPOCFootnote 1 family stories of Japanese “internment” camps to “Indian schools” reveal precisely how and when systemic racism was enacted, while white families are routinely taught to elide, overlook, or forget these atrocities (Ali-Khan Reference Ali-Khan2022). These are just three examples among hundreds in US history. Why would a person whose family was decimated by a government medical program within living memory (the Tuskegee Study ended only in 1972) be enthusiastic to comply with new government medical directives? Why would scientists and public health officials expect otherwise? Only a profound disconnect between (predominately white) public health storytellers and BIPOC audiences could lead to disdain for “vaccine hesitancy” instead of respect for vaccine questioning.

Narrative structures operating in this context may also be at odds. On the one hand, the transformation structure turns those who survived despite terrible obstacles into heroes, with lessons learned that include caution about new government medical programs. On the other hand, public health officials hope to tell a discovery narrative about the invention and value of vaccines against COVID-19, in the urgent context of pandemic. They expect to be trusted as experts and believe that more information is the answer. This attitude fails because they are outsiders to communities who have previously suffered because of such experts. If transformative survival has required caution while a discovery story demands immediate action, some audiences would understandably require time to consider those narrative contradictions.

This relates to the complexities of disconnects between knowledge commons, particularly when information travels through family stories. Families are frequent sources of information. This information is both explicit and implicit, instructional and cultural, and informs all aspects of life including which knowledge commons are available to, unavailable to, or even systematically obscured from particular individuals.

Unfortunately, there is evidence that white audiences cannot always hear the stories that BIPOC people tell. In a series of storytelling for social justice workshops, facilitators developed guidelines and a “pausing” practice to combat unconscious racism in the moment after a BIPOC individual tells their story of “discovering the degree to which racial advantage and disadvantage are constructed”:

Before she can finish, a white participant interrupts and asserts that she too has experienced disadvantage and that the problem is really class not race. One can feel the entire room hold its collective breath. Clearly this is a crucial moment. Will we move on with the discussion, as often happens, smoothing over tension and disagreement? Instead, one of the facilitators quietly asks the white participant to repeat what she heard her African American colleague say. When she cannot do so, it becomes clear that she had tuned out the first speaker.

Any knowledge commons is constructed without attention to the complex ways that white audiences routinely fail to listen to BIPOC storytellers may perpetuate systemic racism. In the case of COVID-19 vaccination, the statistics have shifted over time as more people receive at least some vaccination, but disparities remain in vaccination availability, job-related viral exposure, and the health effects of systemic racism that increase risk of poor health outcomes from COVID-19 infection, even as much remains unknown (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Storytelling insights

| Cases | Insights from triangle | Insights from narrative structure |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine misuse: desperation and Ivermectin | Teller allies with audience against “them” and “what they’re not telling you” “Secret” revealed to audience, aura of mystery | Transformation story, teller as “hero” revealing “truth” discovery narrative, revealing something everyday with hidden uses |

| Exploiting vaccine hesitancy: faked magnetism | Teller uses shock based on trickery to activate audience emotionally to resist If audience trusts teller, then likelihood of retelling increases | Continuity story, in that the underlying message is to focus on maintaining the status quo despite disruption |

| Aftermath of medical racism: vaccine questioning | Inherited information: teller and audience are insiders together as families who survived governmental medical officials expect trust because of expertise and believe that more information is the answer | Transformation structure makes those survived despite terrible obstacles heroes Public health officials hope to tell a discovery narrative about the invention and value of vaccines |

Storytelling Abilities and Misinformation

Understanding the storytelling abilities required to spread misinformation may help us to specifically examine where in a storytelling process does information become inaccurate. In the context of the COVID-19 infodemic, the S-DIKW framework can be adapted to provide a structure for understanding when storytelling goes wrong, through examining how each of these levels of human storytelling abilities relates to creating or spreading misinformation as story. This can in turn help to explore and explain where and how misinformation amplifies social justice and civil rights or perpetuates racism.

With many compelling forms of misinformation circulating, coupled with the disappointing research discovery that fake news circulates faster than real news (Vosoughi et al. Reference Vosoughi, Roy and Aral2018), how can storytelling help to combat these issues? For example, how can public health leaders serve as storytellers to propagate accurate information stories while also acknowledging the historical injustices committed by public health work? For examples like misused Ivermectin or faked vaccine magnetism, it would be good to have a more rigorous understanding of how audiences come to adapt and retell these stories as their own, further misinforming communities.

One approach is to consider the S-DIKW framework from the perspective of misinformation, by asking: How has the story gone wrong? It might be false from the start (bad s-data); misunderstood (bad s-information); or wrongly put into action (bad s-knowledge); or wisdom, containing stories of important community knowledge but limited, misapplied, or risky (bad s-wisdom). The four-part framework below revises the S-DIKW framework for understanding the storytelling abilities necessary for misinformation storytelling.

Misinformation S-DIKW

Bad S-Data: Evoking cultural cues that imply factuality for data that is false

Bad S-Information: False data with context that misinforms in story

Bad S-Knowledge: Stories based on false information that lead to ineffective or harmful actions

Bad S-Wisdom: Reactivity that leads to retelling misinformation as story without checking sources in ways that amplify harm

Like the DIKW hierarchy, these levels typically build on one another. Bad S-Data, for example, frequently appears on platforms like Twitter in the use of manipulated or patently false (and unsourced) graphs or charts that look like data visualizations. A common example is faked data showing grossly exaggerated negative effects of vaccination. Bad S-Information would connect such a faked visualization with a caption addressing audiences and often encouraging further sharing. Bad S-Knowledge would be stories from people who use bad S-Data and bad S-Information as justification for harmful or negligent actions, such as refusing to be vaccinated despite public health and doctors’ advice. Bad S-Wisdom is at least (and there might be more to consider here as well) telling a bad story at a time that will cause or reinforce harm to human health outcomes.

The three cases above each provide an interesting lens for considering the Misinformation S-DIKW framework. For the first case, Ivermectin was briefly considered a potentially useful antiviral drug, so at a particular moment prior to clinical trials, there was real (albeit partial and inconclusive) s-data about its potential. However, once that was disproven, then the lingering interest in Ivermectin was based on bad s-data that attempted to revive a theory that had been shown to be false. The way that time – for example, the process and outcome of clinical trials – factors into medical discoveries and the scientific process in general is not easy to tell as a story. The urgency of pandemic threats make this more difficult and complicated.

In the second case, faked magnetism was based on bad s-data that was produced as falsehood from the outset. Bad s-data became bad s-information by spreading false fears about vaccination, bad s-knowledge by discouraging vaccination, and bad s-wisdom through retelling. In essence, this is thoroughly bad S-DIKW.

The third case, however, is again more complex. The histories of medical racism injustices are real. In other words, they are based on good s-data and s-information, because the harm caused was real. In considering what to do, the s-knowledge to act cautiously and skeptically based on prior abuses is reasonable. The problem occurs at the level of s-wisdom. It is bad s-wisdom to avoid vaccination in a situation where vaccination can save lives and reduce harm. But it is also bad s-wisdom for medical and public health professionals to expect there to be no lasting consequences of governmentally sponsored medical abuse.

Ultimately, by looking at what goes wrong, a storytelling analysis may reveal more about the design strategies used by disinformation sources as they craft stories intended to go viral.

Where Is the Wisdom?

Knowing how to tell the truth is easy with accurate data. Knowing how to tell what information is accurate is also relatively easy. However, telling a story that persuades audiences to act by conveying knowledge is more difficult, and conveying wisdom is more difficult still. As T. S. Elliot wrote: “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” (Eliot Reference Eliot1934). For example, debunking false information can be tricky, because reiterating the fake message in order to correct it may serve to reinforce it through repetition.

What part might wisdom have in discerning whether to retell such a story? Recent storytelling theory defines wisdom in two ways: (1) knowing which story to tell when and to whom, and (2) seeing a way beyond the ways that are obvious (McDowell Reference McDowell and Miller2021). Knowing which story to tell involves understanding what audiences will find enticing, convincing, and repeatable. From a public health knowledge commons perspective, it will mean making true stories as interesting as they are accurate.

One kind of trouble comes in the combination of false transformation narratives and conspiracy dynamics between tellers and audiences. Let’s imagine a storyteller who, skeptical of COVID-19 news, speculates about the urgency of vaccination. That storyteller connects with audience members who share their stories expressing fears in falsehoods that the government is adding chips or tracking devices to people through vaccines. Together, reacting with fear and righteous indignation rooted in emotional responses linked to victimization, these stories escalate, moving quickly across the internet and amplifying from skeptical speculations to claims of conspiracy. Once a conspiracy theory is activated, the door may have already closed, dividing believers who form an increasingly tight-knit circle from anyone else who might hold contrary evidence or opinion (Hansson et al. Reference Hansson, Orru and Pigrée2021).

In thinking about a way beyond the ways that seem obvious, it is currently easier to imagine banding together to create misinformation than to stop it. Recent internet memes about “camping” as a ruse for traveling to access abortion are an example, in that groups rapidly made up and spread a cover story for people whose reproductive rights had been stripped by the Supreme Court. In a much older example, from a Haitian folktale, the girl Tipingee’s stepmother tries to give her away as a servant to a stranger. The stepmother dresses her in red to mark her for the taking, but Tipingee overhears and shares the plan with all of the village girls. The next day, when the stranger comes to steal Tipingee away, they are all wearing red, hiding her in plain sight, and repeating the (infectious) chorus of “I’m Tipingee, she’s Tipingee, we’re Tipingee too.” In the ending, justice prevails, and the stranger takes the stepmother instead (Ragan Reference Ragan1998).

Folktales may have an important place in considering the commons. Stories handed down through generations in a culture contain the wisdom of that way of living. And many Indigenous perspectives focus on knowledge as a shared resource. From the perspectives of “overstudied others,” “Western knowledge and knowledge production is perceived as supporting and reproducing settler colonialism and the reification of knowledge as a commodity. This is directly opposed to Indigenous perceptions of knowledge as a shared community resource” (Tuck and Yang Reference Tuck and Yang2014, cited in Oliphant Reference Oliphant2021, 960).

Of course, as the Toelken example mentioned earlier shows, the wisdom of a commons might involve hiding information as well as informing. Since it is patently unethical to manipulate, injure, and withhold treatment from humans in scientific experiments, stories like Tipingee beg the question: When is it ethical and perhaps even necessary to deceive in order to do the right thing? Communities which have been subject to settler colonialists have sometimes wisely hidden their knowledge in order to survive state-sponsored genocide.

Everyday misinformation and knowledge commons alike need to engage actively and rigorously with the concept of wisdom, particularly in considering how to forge a way beyond the ways that seem obvious. One aspect of wisdom should be a broad consideration of how challenging everyday circumstances can be for information sharing and knowledge commons. Sharing accurate information is difficult when the information is changing quickly, as with the emergence of a novel coronavirus that sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific advances continue on a monthly if not weekly basis, as do announcements of new variants discovered, and so it is difficult even for adept scientifically literate audiences to keep up. Even though the teams that invented vaccines moved incredibly quickly in a story that will become one of the scientific triumphs of our era, the rapid movement of information and misinformation remains complex and challenging.

Conclusion

Storytelling wisdom may be a key tool for engaging deep or complex social problems. Some of the most complex issues related to social justice, civil rights, racism, and more have been understood as relating to storytelling and narrative (Bell Reference Bell2010; Polletta Reference Polletta2006). Survival in a pandemic can be supported by inherited family stories like the one my great-grandmother told to my mother about safely visiting through an open window. Survival against medical racism can be supported by family stories that tell of the horrors of Tuskegee and the questioning of governmental medical programs. Recently, scholars have begun to name some of the information harms of racism and its connection to epistemicide, or the “killing, silencing, annihilation, or devaluing of a knowledge system” (Patin et al. Reference Patin, Sebastian, Yeon, Bertolini and Grimm2021b). As much damage as misinformation storytelling can cause, equally damaging are the forces that silence voices and still stories that could support survival if only they could be known.

Cultivating storytelling wisdom in the face of an infodemic requires great care in thinking about the ways that a particular version of a story emerges between a teller and an audience. Understanding how storytelling dynamics can spread misinformation stories may be key to public health communications that engage effectively with communities’ everyday misinformation challenges. Storytelling offers a framework for researching collective experiences of information as a process that is inherently based in communities, with knowledge commons that are instantiated by the telling and retelling of stories, temporarily or permanently.

In other areas of misinformation research, similar approaches may be helpful in revealing what is happening and how to intervene to support accurate information sharing. In any field involving a commons orientation – public health, law, sociology, and many more – these frameworks could be productive for analyzing the interplay and layers of narrative dynamics and the narrative structures in order to more systematically understand how storytelling is contributing to misinformation. This may be especially important when competing contradictory narratives are at play between those governing and those governed, even within the same community. At the same time, there is no one form of analysis of information that will solve all of the social information problems today. Storytelling is one among many ways of analyzing information, but it has been an overlooked one until recently, and it deserves to be included in discussions about everyday misinformation and knowledge commons.

With its person-to-person form of circulation and retelling as recreation, it may be that storytelling is one of the most ungovernable aspects of knowledge commons, but it should be considered. It is worth analyzing complexities of exchanges among tellers and audiences and the stories that emerge and evolve between them. Misinformation moves at great speed, and understanding storytelling may help us to understand part of what creates that speed.