Mental health problems cause a significant burden of disease in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet the documented ‘mental health treatment gap’ is up to 90%.Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess and Lepine1–Reference Thornicroft3 The need for mental health services is much greater in populations affected by humanitarian crises. More than 135 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance owing to ongoing humanitarian crises and conflicts globally.4 A systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health outcomes in populations affected by conflict and displacements showed that mood and anxiety disorders were common, with rates of 17.3% for depression and 15.4% for post-traumatic stress disorder.Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and Van Ommeren5 Epidemiological studies from areas affected by humanitarian crises in Pakistan found high rates of psychological distress in these populations. One study reported rates as high as 38–65% for psychological distress in women.Reference Roberts and Browne6,Reference Tol, Barbui and Van Ommeren7 The majority of people have no access to mental health services in such settings.Reference Roberts and Browne6 Over the past decade, significant progress has been made in terms of availability of evidence-based mental health intervention packages for populations affected by humanitarian crises.Reference Bangpan, Lambert, Chiumento and Dickson8 However, sustainability and scalability of such psychological interventions remain a challenge in populations affected by humanitarian crises in low-resource settings globally.Reference Allden, Jones, Weissbecker, Wessells, Bolton and Betancourt9

We developed and tested a brief, multicomponent behavioural intervention, Problem Management Plus (PM+), delivered by lay health workers for common mental disorders in conflict-affected settings. The intervention was effective for treating the symptoms of common mental disorders in a post-conflict setting in Pakistan. The trial protocol and results of pilot and definitive clinical trials have been published.Reference Rahman, Riaz, Dawson, Usman Hamdani, Chiumento and Sijbrandij10–Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson and Khan12

In the present study, we conduct an economic evaluation alongside the randomised controlled trial to assess the cost-effectiveness of this intervention in order to inform policy and implementation in routine clinical practice.

Method

Study site and participants

Participants were 346 primary care attendees with high levels of psychological distress (score >2 on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)Reference Minhas and Mubbashar13) and functional impairment (score >16 on the 12-item version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0)Reference Üstün, Kostanjsek, Chatterji and Rehm14). The participants were individually randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention arm, i.e. PM+ along with enhanced usual care (EUC) (n = 172) or the control arm, i.e. EUC only (n = 174). The study was approved locally by the Institutional Review and Ethics Board of the Postgraduate Medical Institute, Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar, and by the WHO Research Ethics Review Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

The intervention

Participants in the intervention arm received a brief multicomponent intervention called Problem Management Plus (PM+) in addition to EUC.Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman and Schafer15 PM+ is transdiagnostic as it applies the same underlying principles across mental disorders, without tailoring the protocol to specific diagnoses.Reference McEvoy, Nathan and Norton16 PM+ is based on well-established principles of problem-solving and behavioural techniques. It is designed to be used with adults experiencing common mental health problems (e.g. anxiety, stress, depression and grief) only. It is not suitable for the treatment of severe mental health problems (including psychosis or risk of suicide). Both an individual and a group version of the intervention exists. The current study involves the individual version.

PM+ consists of 5 weekly face-to-face sessions of 90 min each, delivered by trained lay health workers. The intervention is composed of four core strategies (stress management; managing problems; ‘get going, keep doing’ (behavioural activation); and strengthening social support), introduced sequentially in the intervention sessions. In the last session, all the strategies are reviewed with an emphasis on using these strategies for self-management in the future and to prevent relapse.

Training and supervision followed a cascade model. An international trainer trained local trainers during a 6-day training workshop. Training consisted of intervention delivery, training and supervision skills. Local trainers cascaded the training to lay health workers (with 12–16 years of education) in an 8-day training. Lay health workers were provided weekly supervision by local trainers/supervisors (hereafter, local supervisor), who were in turn supervised monthly by the international trainer/supervisor (hereafter, international supervisor) via video conference for 2–3 h. PM+ is available in Urdu and English on the WHO website.17 Further details of the intervention are described elsewhere.Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman and Schafer15

Enhanced usual care

The participants in both the intervention arm and the control arm received enhanced usual care (EUC). The care was enhanced as the primary healthcare physicians in the participating primary healthcare centres received a 5-day training in the management of common mental disorders in primary healthcare settings. The training was reinforced through a 1-day refresher course for the physicians. The study participants in both arms were able to seek other healthcare services from their primary healthcare physicians.

Data collection

Health outcomes

The outcomes were measured at baseline and 3 months post-intervention. The cost-effectiveness analysis was performed as incremental costs per unit change in anxiety, depression and functioning scores. The primary outcome was change in symptoms of anxiety and depression measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).Reference Zigmond and Snaith18,Reference Mumford, Tareen, Bajwa, Bhatti and Karim19 Severity of symptoms was measured using the HADS anxiety subscale (7 items; possible score range, 0–21) and depression subscale (7 items; possible score range, 0–21). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety and/or depression. Secondary outcomes were functional impairment and presence of depressive disorders. The 12-item WHODAS 20 was used to assess functional impairment. The polytomous scoring algorithm was used to transform the functional impairment scores on a scale of 1–100.Reference Üstün, Kostanjsek, Chatterji and Rehm14 Presence of depressive disorder was measured using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams20 Other secondary outcome measures included the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5),Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr21 results of which appear in the supplementary material, available at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.138.

Health resource use profiling

The data on health resource use were collected using the Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI),Reference Chisholm, Knapp, Knudsen, Amaddeo, Gaite and Van Wijngaarden22 which records patients’ contact with out-patient services (i.e. mental health specialists, general physicians, traditional healers, community health workers, etc.), in-patient (hospital admissions) services and out-of-pocket costs associated with travel, medications and tests/investigations during the preceding recall period. A section on seeking religious help and retreats was added to adapt the tool for use in the local population. Study participants self-reported their healthcare utilisation, medication use and out-of-pocket expenditures on the CSRIReference Chisholm, Knapp, Knudsen, Amaddeo, Gaite and Van Wijngaarden22 at baseline and 3 months post-intervention.

Cost measurement and analysis

Economic analysis was conducted primarily from a health system perspective, consisting of (a) costs incurred over the trial period in the delivery of the intervention itself, (b) use of other healthcare and related services by study participants, including religious help and retreats, and (c) patient and family costs (such as number of days with reduced working hours, informal caregiving time by relatives or friends, as well as travel costs and time spent travelling to or waiting for consultations). No discounting of costs was applied, since the study was performed within 1 year.

Intervention costs included: costs for the intervention adaptation workshops; translations of the PM+ manual and training materials; printing of adapted training manuals; and staff recruitment, training and supervision. Supervision costs included time spent by the master trainer, supervisors, transport costs for fieldwork supervision and costs of all other resources used.

To estimate the cost of intervention delivery, we evaluated unit cost per minute of healthcare providers’ time, including the international trainer/supervisor, local supervisors, lay health workers and physicians. To calculate the total cost of intervention delivery, the unit cost per minute was multiplied by the total estimated time spent by each healthcare provider with the participants. We calculated the cost of intervention delivery by the international trainer/supervisor and modelled the cost for a local supervisor as a potentially more sustainable way to support task-shifting in low-resource settings. Costs of the intervention were calculated by multiplying the total contact time (number of minutes) a participant in the intervention arm had with a lay health worker by the per-minute cost of the lay health workers’ time and the costs spent on travelling by lay health workers (unit cost calculations are provided in the supplementary material).

Calculation of these intervention costs as well, as the cost of contacts with a range of formal healthcare providers, was facilitated by the use of a simplified costing template for unit cost calculations reported in health economic evaluation of mental health services.Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar and Chatterjee23 Unit cost templates accounted for the costs of salaries of staff employed in the provision of intervention delivery (including trainer, supervisors, lay health workers and primary healthcare staff), facility operating costs where the service was provided, overhead costs relating to the provision of service (personnel, finance, etc.) and the capital costs of the facility where the intervention was provided (land, buildings, etc.). Sources of data for these variables included public health system financial records and the project's financial records. All costs were calculated in Pakistani rupees (PKR) and are reported in Pakistani rupees and US dollars for the year 2016, when the study was implemented (at an exchange rate of US$1 = PKR 104; www.ceicdata.com/en). No adjustment was made for purchasing power parity (PPP), since the focus of interest was the actual resource costs incurred in the study country (rather than a comparison with other countries, whereby differences in the relative price of goods and services would need to be taken into account).

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation for the total cost were calculated using a generalised linear regression model with gamma distribution after adjustment for baseline total cost. The group difference and its 95% confidence interval was also calculated.Reference McCrone, Knapp, Proudfoot, Ryden, Cavanagh and Shapiro24 The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the additional costs of the intervention divided by the change in HADS anxiety, HADS depression, HADS total, PHQ-9 and 12-item WHODAS 20 scores related to the intervention. The confidence intervals for the ICER were estimated by non-parametric bootstrapping. The bootstrap technique sampled with replacement from the original observed pairs of costs and effects, maintaining the correlation structure between costs and benefits, to create a new data-set with 1000 observations. For each bootstrap resample, an estimate of differential total mean costs and the expected mean effectiveness was calculated.Reference Khan25 The 95% confidence intervals for the differential estimates were derived from the calculated 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. We plotted cost-effectiveness acceptability curvesReference Baltussen, Hutubessy, Evans and Murray26 to evaluate the probability of the PM+ intervention being cost-effective at increasing monetary values, representing willingness-to-pay thresholds for the intervention from policy makers’ perspective.Reference Fenwick, Marshall, Levy and Nichol27 For the effectiveness data, we used linear mixed models to study treatment effects as indicated in our main trial report,Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson and Khan12 which allowed the number of observations to vary at random between participants and effectively handles missing data.Reference Little and Rubin28 At 3-month follow-up, 14% of cost data was missing for medicines, complementary medicines, seeking retreats and religious help, and out-patient services. Summary statistics for each specific cost were presented without imputation but the total costs were calculated assuming missing data as 0 in a conservative way.Reference Khan25

Results

As reported in the clinical effectiveness evaluation,Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson and Khan12 mean combined depression and anxiety symptom scores on the HADS were significantly lower at 3 months post-intervention (adjusted mean difference −5.75; 95% CI −7.21 to −4.29). Similarly, functional impairment significantly improved (adjusted mean difference −4.17; 95% CI −5.84 to −2.51) on the 12-item WHODAS in the intervention arm compared with the EUC arm. At baseline, the depression rate was 94.2% in the intervention arm and 89.4% in the EUC arm. At the end of the 3-month follow-up period, the intervention arm had significantly lower rates of depression (26.9%) compared with the EUC arm (58.9%) (risk difference −31.98; 95% CI −41.03 to −22.94).

Costs

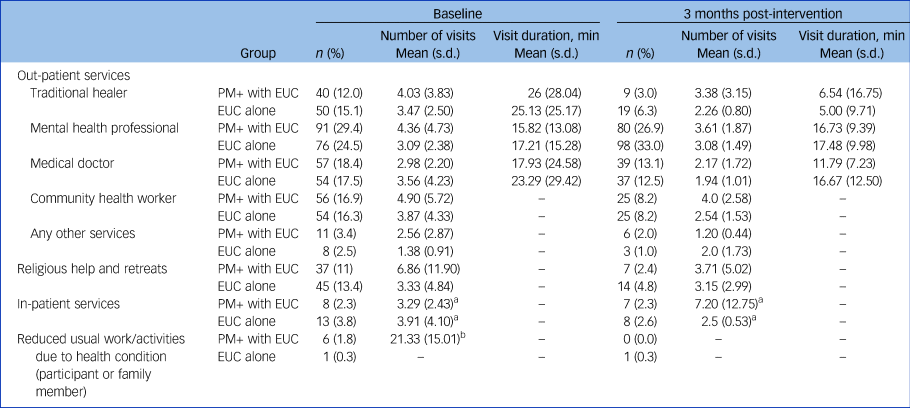

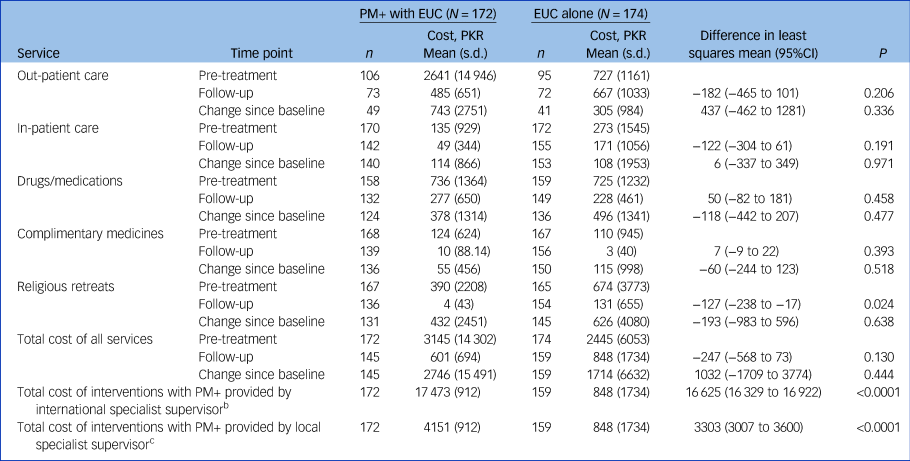

No significant difference in the cost of other healthcare services accessed by study participants was observed between treatment and control groups, with the exception of religious help and retreats. The mental health condition of the majority of trial participants did not result in reduction in their or their family members’ or friends’ usual work/activities (Table 1). Table 2 presents summary statistics and cost results from the mixed-model analysis.

Table 1 Health services utilisation (including religious help and retreats, in-patient services and reduced usual work/activities due to health condition) across the two trial arms at baseline and at 3 months post-intervention

min, minutes; PM+, Problem Management Plus; EUC, enhanced usual care.

a. Nights spent in hospital, for in-patient services only.

b. Mean number of days of reduced usual work/activities due to health condition (for participant or family member).

Table 2 Cost of health services accessed by participants (out-patient, in-patient, drugs/medication, and complimentary medicines and religious retreats) by trial arma

PM+, Problem Management Plus; EUC, enhanced usual care.

a. The data were collected using the Client Services Receipt Inventory at baseline and at the 3-month post-intervention follow-up assessment. Costs are shown in Pakistan rupees (PKR); the 2016 exchange rate was 1US$ = 104 PKR.

b. Intervention costs plus cost of services. The cost of the PM+ intervention using an international supervisor is PKR 16 967.

c. Intervention costs plus cost of services. The cost of the PM+ intervention using a local supervisor is PKR 3645.

With an international trainer/supervisor, the total cost of delivering PM+ per participant was PKR 16 967 (US$163.14). The total intervention arm costs (PM+ costs plus cost of services accessed by the intervention arm as part of EUC) were PKR17 473 (s.d. = 912) or US$168. The cost of EUC (treatment as usual plus cost of services accessed by control arm participants) was PKR 848 (s.d. = 1734) or US$8.15 (Table 2).

Substituting the cost of an international trainer/supervisor with that of a local trainer would substantially decrease intervention costs. The total cost of delivering PM+ using a local trainer/supervisor was estimated to be PKR 3645 (US$35.04). This would be PKR 729 (US$7.00) per session. The total cost of delivering the intervention (with a local trainer/supervisor) plus EUC in the intervention arm would be PKR 4151 (s.d. = 912) or US$40.

Cost-effectiveness

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) indicate that the intervention was both more effective and costlier than EUC for all the health outcomes studied (Table 3). Analysis was conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the PM+ intervention in two scenarios: (a) PM+ delivery by lay health workers supervised by an international trainer/supervisor (as observed in the trial) and (b) PM+ delivery by lay health workers supervised by a local supervisor. The second scenario will be the case for scale-up of the intervention package in real-world settings. The additional costs associated with the intervention led to a relative improvement in outcomes. For example, the mean cost per unit score improvement in anxiety and depression on the HADS was PKR 2957 (95% CI 2262–4029) or US$28 with an international trainer/supervisor. This would be PKR 588 (95% CI 434–820) or US$6 with a local trainer/supervisor; with an international supervisor, each 1-point improvement on the WHODAS cost PKR 4097 (95% CI 2978–6046) or US$40, whereas with a local supervisor it was estimated to cost PKR 815 (95% CI 576–1225) or US$8. We plotted 1000 resampled estimates of costs and outcomes on a cost-effectiveness plane for the primary and secondary outcomes. The results show that all the resampled estimates fall in the upper-right quadrant, i.e. PM+ is ‘more effective but costlier’ in all of the resampled estimates.

Table 3 Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs)a for the PM+ intervention at 3 months post-intervention for international versus local supervisors

PM+ intervention, Problem Management Plus with enhanced usual care; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (subscale score range: 0–21; higher scores indicate elevated anxiety or depression, respectively); WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (12-item version, total score range: 0–48; higher scores indicate more severe impairment); depression caseness, defined as a Patient Health Questionnaire score ≥10.

a. Costs are shown in Pakistan rupees (PKR); the 2016 exchange rate was 1US$ = 104 PKR. Costs were estimated after adjusting several baseline variables (baseline total cost, age, gender, occupation, marital status).

b. Confidence intervals were estimated using non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 resamples.

The mean ICER to successfully treat a case of depression (PHQ-9 cut-off ≥10) using an international supervisor was PKR 53 770 (95% CI 39 394–77 399) (US$517), compared with PKR 10 705 (95% CI 7731–15 627) (US$102.93) using a local supervisor. ICERs for other outcome measures are compared in Table 3.

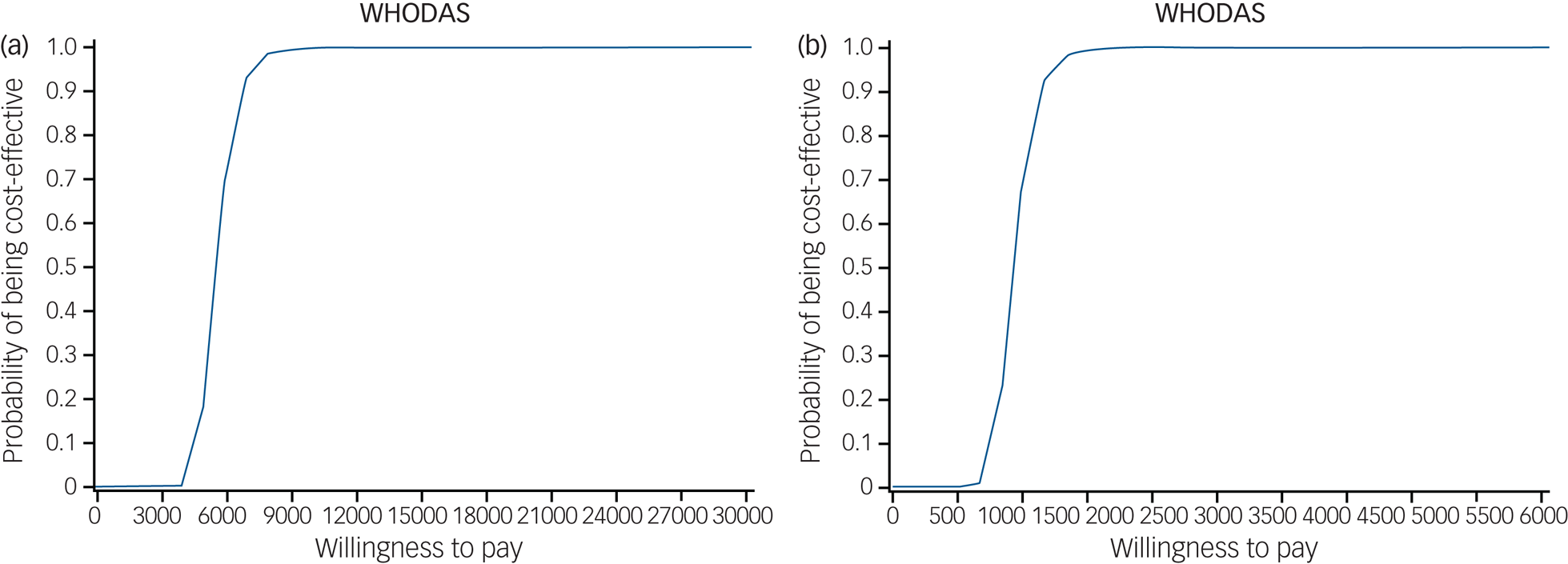

The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the PM+ intervention in relation to outcomes on the HADS (total score) and 12-item WHODAS with an international specialist supervisor are shown in Figs 1(a) and 2(a). The intervention has more than 90% probability of being cost-effective compared with EUC above a willingness-to-pay threshold of PKR 7000 (US$67) for a one-point improvement in depression and anxiety (HADS total score) (Fig. 1(a)) and PKR 6000 (US$57) for a one-point improvement in functioning (WHODAS) using international supervisors (Fig. 2(a)). These thresholds would be reduced by 80% using local supervisors (Figs 1(b) and 2(b)).

Fig. 1 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for Problem Management Plus (PM+) in relation to improvement in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) total score at 3-month follow-up (end-point). (a) PM+ using an international supervisor. (b) PM+ using a local supervisor. Costs are shown in Pakistan rupees (PKR); the 2016 exchange rate was 1US$ = 104 PKR.

Fig. 2 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for Problem Management Plus (PM+) in relation to improvement in score on the 12-item version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 20) at 3-month follow-up (end-point). (a) PM+ using an international supervisor. (b) PM+ using a local supervisor. Costs are shown in Pakistan rupees (PKR); the 2016 exchange rate was 1US$ = 104 PKR.

Discussion

Main findings

Our results show that the PM+ intervention (PM+ together with enhanced usual care, EUC) is more effective and more costly than EUC alone in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. Although there is inevitable uncertainty regarding point estimates, our analysis has shown that even at very modest levels of willingness to pay for a one-point improvement in symptoms or functioning outcomes there is at least a 90% probability of this intervention being a cost-effective use of resources compared with EUC. We concluded that the value is ‘modest’ because that amount is equivalent to, for example, less than 10% of the minimum monthly wage in Pakistan in 2017.29 These findings are consistent with evidence from LMICs on the cost-effectiveness of a task-shifting approach to delivering psychological interventions for the treatment of common mental disorders compared with EUC delivered by primary healthcare physicians.Reference Buttorff, Hock, Weiss, Naik, Araya and Kirkwood30,Reference Weobong, Weiss, McDaid, Singla, Hollon and Nadkarni31 With the current model of training and supervision by an international trainer/supervisor, the intervention was five times more costly for treating one person with depression, compared with modelled costs of training and supervision by local trainers. This emphasises the need to build the capacity of a local mental health workforce.Reference Murray, Dorsey, Bolton, Jordans, Rahman and Bass32

Comparison with the literature

The resources, capacity and infrastructure for mental health services research, including health economic evaluations alongside randomised controlled trials, are limited in the humanitarian settings of LMICs.Reference Levin, Chisholm, Patel, Chisholm, Dua, Laxminarayan and Medina-Mora33 This is one of the very few studies to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a psychological intervention in a humanitarian setting. There are only a few published studies on the cost-effectiveness of task-shifting interventions in global mental health. Araya et al (2006) evaluated the incremental cost-effectiveness of a stepped-care multicomponent programme for the treatment of women with depression in primary care in Chile. The stepped-care programme was more effective and costlier than usual care (an extra US$0.75 per depression-free day).Reference Araya, Flynn, Rojas, Fritsch and Simon34 Buttorff et al (2012) conducted an economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care settings in India. They concluded that the use of lay health workers in the treatment of common mental disorders in public primary care facilities was not only cost-effective but also cost-saving. The mean health system cost per person recovered at the end of follow-up was US$128 (95% CI 105–157) in the intervention arm and US$149 (95% CI 131–169) in the control arm.Reference Buttorff, Hock, Weiss, Naik, Araya and Kirkwood30 Other similar studies of psychological interventions delivered by lay health counsellors in IndiaReference Weobong, Weiss, McDaid, Singla, Hollon and Nadkarni31 have replicated the findings of cost-effectiveness of task-shifting interventions for treating depression and alcohol problems in primary care settings. Sikander et al (2019) evaluated the cost-effectiveness of a peer-volunteer-delivered cognitive–behavioural intervention for post-natal depression compared with EUC in community settings of rural Pakistan. The intervention was costlier than EUC but was effective in reducing the severity of post-natal depression (the cost per unit improvement in PHQ-9 score was US$15.50 (95% CI 9.59–21.61) for the whole study period). The intervention had a 98% probability of being cost-effective above a willingness-to-pay threshold of US$60 per unit of improvement on PHQ-9 score compared with EUC.Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen and Weiss35 Although it is difficult to compare the results of cost-effectiveness evaluations across studies (owing to differences in analytical approaches, treatment conditions and different outcome measures), the results of these studies demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of brief psychological interventions using a task-shifting approach.

During humanitarian crises, healthcare systems tend to be overwhelmed, human resources are overstretched and access to specialists for referral and support is limited. It is therefore important to determine how interventions with proven efficacy can be scaled up in a cost-effective way.Reference Ventevogel, van Ommeren, Schilperoord and Saxena36 Our study and evidence from the literature support the effectiveness of implementation strategies such as task-shifting and transdiagnostic approaches to bridge the treatment gap for mental health problems in low-resource settings. With the increased availability of evidence-based psychological intervention packages, further health economic evaluations are needed to inform the resource needs to scale up evidence-based care for mental illness.

Limitations

A limitation of the cost-effectiveness approach used in our study is that the results are limited to direct healthcare costs and health-related outcomes of the PM+ intervention, and do not extend to the wider economic or social value of investing in mental health, which may be quite significant in a humanitarian context. Future health economic evaluations of global mental health will benefit by integrating the opportunity and time cost of lay health workers and non-specialists. The added value that results from such task-sharing implementation strategies in terms of empowerment, opportunities and career growth for the non-specialist healthcare workforce as well as the increase in treatment coverage for priority mental health conditions will also need to be accounted for in future studies. We did not make any adjustment for purchasing power parity (PPP), since the focus of this study was the actual resource costs incurred in the study country. However, for the purpose of international comparison, the PPP adjusted total intervention costs of PM+ were I$546 per participant. Estimated costs of delivering PM+ using a local trainer in Pakistan would be I$114 per participant. Another limitation of our study is that we estimated costs per point reduction in symptoms of anxiety and depression and cost per person recovered from depression, which limits the ability to compare results with other interventional studies on the basis of cost-utility measures (quality-adjusted life years, QALYs). Future studies may use change in health outcomes that are easily interpretable and meaningful enough for policy makers to make decisions, and should also collect data on population-based health-state preference scores that would enable the calculation of QALYs.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.138.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors on request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the project staff in the Department of Psychiatry, Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar, and the Human Development Research Foundation (HDRF), Islamabad, Pakistan, for their contributions; the primary healthcare staff and physicians for their support in the conduct of the study; and the participants and their families for their voluntary participation. We would like to specially thank Dr Victoria Baranov (senior lecturer in economics, University of Melbourne, Australia) for sharing her insights in revising the manuscript for resubmission.

Author contributions

S.U.H., Z.e.H., T.C. and D.W. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: S.U.H., A.R., S.F., D.C., M.v.O.; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: S.U.H., Z.e.H., D.W., S.F., M.v.O., D.C.; drafting of the manuscript: S.U.H., Z.e.H., A.R., M.v.O., D.C., S.F.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: S.U.H., Z.e.H., A.R., S.F., D.C., T.C., D.W., M.v.O.; statistical analysis: S.U.H., Z.e.H., D.C., T.C., D.W.; obtained funding: M.v.O., A.R., S.U.H.; administrative, technical, or material support: S.U.H., Z.e.H., A.R., S.F., M.v.O.; study supervision: S.U.H., A.R., S.F., M.v.O.

Funding

This work was supported by the Enhanced Learning and Research for Humanitarian Assistance (Elhra) Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises (R2HC) initiative, funded by the UK Department for International Development and the Wellcome Trust. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interest

M.v.O. and D.C. are staff members of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the World Health Organization.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.138.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.