1. IntroductionFootnote 1

This paper examines mirative uses of should and would in patterns within the postmodal domain, contributing to the debate on characterising modal auxiliaries as constructions or as grammaticalised forms. While mirative extensions arise in similar contexts, their grammaticalisation depends on the modals’ original semantics, which are not identical.

The study redefines the ‘complementation meaning’ of should and would – described by van der Auwera and Plungian (Reference Auwera and Plungian1998: 93) as postmodal, deriving from epistemic possibility or epistemic necessity and uses it to explain mirative extensions across patterns. A multilayered approach to modality shows how the complementation position can generate mirative readings. Corpus data further demonstrate that illocutionary force can induce similar effects.

Section 2 compares the mirative extensions of why-would and why-should questions, linking them to the complementation meaning. Section 3 argues that TWBX reflects a postmodal shift, encoding the assumed unexpectedness of the predicative complement. The operationalisation of postmodality enables a unified illocutionary analysis of previously scattered constructions. The semantic profile of would supports its postmodal development into the ‘That would be X’ construction, whereas should cannot undergo such a constructionalisation. Moreover, the postmodal domain is not homogeneous: variation arises depending on information structure, and expectation sensitivity (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmathforthcoming) provides a functional motivation for new postmodal constructions.

2. Mirative Extensions of Should and Would in Content Clauses

2.1. Layers of modality in should and would

Should and would in content clauses may take on different meanings. In this study, I focus on the meaning that is variously labelled as ‘emotive’ (Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), ‘meditative-polemic’ (Behre Reference Behre1950; Behre Reference Behre1955), ‘putative’ (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985) or ‘theoretical’ (Leech Reference Leech2004). These labels are generally applied to should. Some studies, however, have emphasised that would has a similar use in content clauses. For instance, Jacobsson (Reference Jacobsson1988) notes that British English favours should (1), whereas American English prefers would in comparable contexts (2). The following dialectal variants may be considered similar in terms of usageFootnote 2:

In (1) and (2), it’s only natural in the matrix clause introduces an evaluation of the extraposed subject content clause. This evaluative judgement is foregrounded and intended to be accepted as any assertive statement. It is the interplay between the lexical element in the matrix clause and the modal verb in the content clause that is taken as the starting point of this study. The meaning produced by this combination will be analysed as a mirative extension of the original modal meaning.

Mirativity is generally defined as a semantic category that encodes unexpectedness and novelty (DeLancey Reference DeLancey1997, Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2012). My conception of mirativity, however, is closer to Zeisler’s (Reference Zeisler2017) and Guentchéva’s (Reference Guentchéva2017) definitions of admirativity. Following these authors, I associate mirativity with the marking of an addressee-oriented attitude rather than the encoding of new information. As will be shown in this paper, this attitude, which consists in indicating that some state of affairs deviates from what was or is to be expected, has strong repercussions on the speaker’s commitment, which explains why it is highly sensitive to speech acts.

Before addressing the impact of the main predicate on modality in embedded clauses, a characterisation of the primary meanings of should and would in independent clauses is in order. While modals denote abstract meaning, their modal force may be modified by the pragmatic context. This intrinsic tension has consequences on meaning change. The theoretical issues raised by the use of modals in factual contexts will be addressed once a semantically-based characterisation of should and would has been laid out. I start by outlining the semantic properties of should and would, focusing on their difference with respect to past time reference, as this will be deemed crucial to understand their respective postmodal behaviour.

Conceptually, modality denotes a semantic domain that involves necessity and possibility (van der Auwera & Plungian Reference Auwera and Plungian1998). At the same time, modality is inherently concerned with the speaker’s attitude to the factuality or actualisation of a situation (Palmer Reference Palmer1990: 2, Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 173, Narrog Reference Narrog2005). In this respect, should and would are not symmetrical. A well-known difference between the two modals comes from the role of their preterite morphology. While would may refer to the past, i.e., to actualised situations in the past, should never does (Bybee Reference Bybee, Bybee and Fleischman1995: 504; 514). Because should conveys a present perspective on a situation, it is classified as a ‘modal for the present’ by Condoravdi (Reference Condoravdi, Beaver, Clark, Kaufmann and Martnez2002), along with may, must, might, and ought to. The preterite form contributes modal remoteness, which has consequences on the modal meaning. As Arigne (Reference Arigne2007) notes, the modal use of the preterite superimposes an idea of possibility on the primarily deontic meaning of the modal:

While root necessity denotes what seems right to the speaker, the possibility meaning implies that ‘other desires are possible’, potentially leading to a different course of events. Similarly, in the case of epistemic necessity, it has been pointed out that necessity is ‘noncommitted’ (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 227), or that ‘the speaker has doubts about the soundness of his /her conclusion’ (Leech Reference Leech2004: 101):

A continuation with ‘but they are not at home’ is perfectly acceptable. The speaker’s inference is tentative as it does not exclude something going wrong. The existence of alternative possibilities has consequences on the nature of the inferred situation. As shown by Rivière (Reference Rivière1981), should is not compatible with certainty contexts. It can work from an asserted cause to an inferred consequence, in which case the consequence is uncertain:

But it cannot work from a consequence to a cause, in which case the inferred proposition has a higher level of certainty:

Furthermore, as pointed out by Rivière, should may be used when the time of the inferred proposition is posterior to the time of utterance, i.e., when the level of certainty is weakened by future orientation (5). As stated by Rivière (Reference Rivière1981: 186), ‘[S]hould is used when the inference is most risky, that is to say when the inferred proposition is the consequence and posterior to the time of speaking’.

When should is followed by perfect have, a temporal ambiguity arises: two temporal readings are possible. They are associated with different types of modality, as shown by Condoravdi (Reference Condoravdi, Beaver, Clark, Kaufmann and Martnez2002) in her analysis of non-root modals. Should have tends to convey metaphysical modality, which is concerned with ‘how the world may turn out, or might have turned out, to be’ (Condoravdi Reference Condoravdi, Beaver, Clark, Kaufmann and Martnez2002: 61):

In that case, the perfect has scope over the modal and a past perspective is conveyed, indicating a past necessity. The epistemic necessity for the subject to pass the exam easily extends to some undefined posterior point located in the past. The implication is that this past necessity was eventually not fulfilled. To put it differently, the reading is counterfactual. However, as noted by Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 235), the counterfactual implication is not systematic:

In contrast to (7), a present perspective on a past situation is here adopted, the modal scoping over the perfect. This perspective shift is associated with a change in the modality type (Condoravdi Reference Condoravdi, Beaver, Clark, Kaufmann and Martnez2002). The modal conveys epistemic necessity about a past situation, i.e., it has to do with the speaker’s knowledge state about a past situation at the time of speaking. The modal taking scope over the perfect makes the counterfactual reading impossible.

The epistemic reading is here facilitated by the question-answer pair. The polar question seeks information about Maria to confirm the speaker’s expectation that she was to start her job. By conveying the speaker’s ignorance as to whether their expectations were fulfilled or not, the question blocks the counterfactual implication. Although should have generally favours a counterfactual reading, the context is essential to determine the speaker’s knowledge state. If the context indicates the speaker’s ignorance as to some real-world outcome, the counterfactual implication is cancelled, which may give rise to the epistemic reading.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, the epistemic reading needs to be supported by contextual elements. Without the preceding question that suspends the speaker’s outcome knowledge in (8), the counterfactual reading would obtain, as in (7). It seems, then, that the epistemic reading is not semantically entrenched as the counterfactual reading is. This suggests that should imposes its own preferences that only a relevant uncertainty context can disconfirm.

Would patterns differently with tense.Footnote 4 In its non-epistemic uses, would shifts the perspective to the past based on the speaker’s a posteriori knowledge. In the following examples, actualised past events are being referred to, involving either dynamic modality or posteriority. The reading is factual:

Would conveys some necessity that arises from an internal propensity of the subject in (9) or from the internal (non-)volition of the subject in (10). In (11), the future event is posterior to a past situation that serves as reference point. In retrospect, this event is framed as fatal necessity. However, more often than not, the preterite form of would introduces modal remoteness, i.e., a distance between the situation referred to and the time of utterance. As suggested by Larreya (Reference Larreya, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003), the modal preterite presupposes the unreality of a situation. In the following example, the use of would presupposes that there is no available proof in reality:

The implicit condition is that if some proof were provided now or in the future, it would help to believe the story that is being recounted. The status of epistemic would is less clear. As a result of modal remoteness, the epistemic use is generally deemed tentative (Palmer Reference Palmer1990) and considered to be a weaker, ‘less confident’ variant of epistemic will:

Yet, it has been claimed that would does not necessarily imply uncertainty. Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Birner, Kaplan, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003) and Ward (Reference Ward, Galeano, Görgülü and Presnyakova2012) rightly argue that the use of would is perfectly compatible with the speaker’s high level of certainty in a specific equative construction that they label the ‘That Would Be X construction’:

Ward et al. take this modalised assertion to express the speaker’s high level of confidence and to concern the present. They further argue that if the demonstrative subject is anaphoric to a past event, would have is required to mark past reference:

To sum up, unlike should, would may have a past perspective in non-epistemic uses. However, would is generally a modal preterite that denotes a hypothetical situation. Nonetheless, it seems that in the TWBX construction, the speaker’s claim is based on verifiable objective evidence. The judgement encoded by would in (14) and would have in (15) stands in stark contrast to the epistemic judgement marked by should in (4) and should have in (8). In (4) and (8), the epistemic judgement is associated with the speaker’s high level of uncertainty, whereas the speaker has evidence for the truth of the propositions in (14) and (15). This meaning is puzzling as it contradicts the ‘negative truth-commitment’ generally attached to a modal preterite form (Leech Reference Leech2004: 120). In this paper, I use the label ‘negative bias’ to refer to this negative truth-commitment. I will consider the modal status of would in the TWBX construction to be questionable. I will argue in Section 4 that this meaning can be characterised in a unified way if it is related to the postmodal domain rather than the modal domain. At this point, suffice it to say that in independent clauses, should and would differ as to their factual meaning.

2.2. Modality under the scope of an evaluative factive predicate

We can now examine the impact of evaluative factive predicates on modality in content clauses. I will argue that the interaction of modality with clause phenomena leads to mirative extensions. Crucial in this process is the shift from a priori modality to a posteriori modalisation and from counterfactual to evaluative modalisation (Larreya Reference Larreya, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003, Reference Larreya, Salkie, Busuttil and van der Auwera2009). Drawing upon the Kantian distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge, Larreya (Reference Larreya, Salkie, Busuttil and van der Auwera2009: 24–25) argues that English modals may be used in two ways. In their a priori uses, they indicate that the speaker does not know the truth-value of the modalised proposition, whereas in their a posteriori uses, s/he knows that truth-value. Larreya (Reference Larreya, Salkie, Busuttil and van der Auwera2009: 24) points to a difference in the way modality is used, but not in the nature of modality or the inherent meaning of the modals. He also highlights the fact that in this use of modality, both the speaker’s knowledge and the hearer’s assumed knowledge are taken into account. We will see that the way modality is used may, in fact, lead to meaning change.

Evaluative predicates introduce an additional external layer that specifies the speaker’s stance on the embedded content. My focus is on factive predicates, which communicate the speaker’s knowledge as to the outcome of the situation denoted in the embedded clause. The matrix predicate may enter into conflict with the meaning of the embedded modal:

The impact of the matrix predicate on the meaning of the embedded modal can be made clear by reordering the clause structure. If each clause is changed into an independent clause, syntactic independence is reflected at the modal level and the preterite or the past perfect will be used in a factual assertive statement (16a). In that case, should have is not felicitous (16b):

Recall that should have presupposes that a past necessity was not carried out (see (7)). However, in (16), given the speaker’s knowledge of the outcome, it is already established that the words were inscribed a long time ago, which makes the counterfactual reading unavailable. Should have is not indexed to the speaker’s here and now. The evaluative judgement conveyed in the matrix clause overrides the negative presupposition of should have in the content clause. The meaning of should have is affected by the factive predicate because the speaker’s present state of knowledge precludes a past perspective.

In the case of should, it is the future orientation of the modal that is blocked by the speaker’s information state:

Compare with should used without a posteriori knowledge:

In (18), as in (4) and (5), should conveys uncommitted epistemic necessity, i.e., the speaker cannot rule out the possibility of her voice not being steady in the future. Should is indexed to the speaker’s here and now. By contrast, in (17), the speaker’s emotive and cognitive state follows from her a posteriori knowledge that her voice is steady, which cancels the possibility of an alternative future development.

There is no consensus in the literature on the meaning of should (have) in such content clauses. Criticising the concept of low-degree modality proposed by Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), Salkie (Reference Salkie, Salkie, Busuttil and Van Der Auwera2009: 97–98) argues that the use of should under the scope of factive predicates is ‘near-vacuous’ as a result of semantic bleaching. I agree that the difference between should have in (7) and (16) and should in (17) and (18) is not a matter of degree. Due to a posteriori knowledge, should loses its ability to convey a judgement on the likelihood of a future situation. Likewise, should have loses its ability to convey unfulfilled past necessity. What, then, is the meaning of should (have)?

For information structural reasons, the content clause is backgrounded and modality is not tied to the speaker’s here and now. The extraposed content clause conveys discourse-old information, while the evaluative judgement in the matrix clause is foregrounded. This judgement takes precedence, either communicating the subject referent’s emotive state (17) or highlighting an odd phenomenon (16). In embedded position, the modal has a sense of counterexpectation, which I take as a mirative extension of should (have). This derives from the negative bias of preterite modals. In (16), should have signals that the situation contradicts the normal course of events: the words would be expected on the Liberty Bell after the Fourth of July, not long before. Similarly, in (17), the situation conflicts with the speaker’s expectations. The postmodal domain overlaps with evaluative modality, which does not assess the likelihood of a proposition. Should (have) modalises an eventuality arising from a ‘fatal necessity’ (Behre Reference Behre1950) against the speaker’s (17) or anyone’s (16) expectations, highlighting the conflict between events and expected outcomes.

Surprisingly, should is more frequent when matrix adjectives indicate that the embedded proposition aligns with the speaker’s expectations (e.g., natural). At first glance, this seems to challenge the claim that should has mirative extensions in content clauses. However, as Celle (Reference Celle and Guentchéva2018) shows, these adjectives are either negated (not surprising) or appear with adverbs (perfectly/only natural) indicating a conflict with prior counterexpectations. The evaluative judgement signals that the content accords with expectations after considering prior counterexpectations:

The postmodal use of the auxiliary keeps track of prior counterexpectations. The mirative extension operates at the discursive level, which Arigne (Reference Arigne2017) classifies as ‘discursive mirativity’. Removing should neutralises the polemic aspect:

The extraposed infinitival clause may be purely potential, whereas the modal in (19) encodes the reasoning that led to accepting the idea.

Arigne (Reference Arigne2007) argues that this shift from mental resistance to mental acceptance characterises ‘multistratal modality’, reflecting grammaticalisation. Based on Behre, she shows that should after negative evaluative predicates (sorrow, displeasure) predates its more ‘intellectual’ argumentative uses, which derive semantically from emotive factive embedding. Celle (Reference Celle and Guentchéva2018: 39) corroborates this: in the BNC and COCA, should is more frequent under natural than under strange. After non-negated emotive adjectives, the frequency drops, with present and past tenses preferred in unmodalised clauses:

Changing subordination to coordination clarifies that these situations are factual, independent of the evaluative judgement:

This change alters information structure but not the modal status of the situation targeted by the evaluative judgement. Therefore, this situation is factual, unlike in (16), where modality depends on the matrix clause.

To recapitulate, the situation modalised by should is abstracted from a reference frame. A factive predicate presupposes the subordinate clause’s truth, but the modal encodes a counterexpectational representation rather than actualisation. Even in factual contexts, should does not describe the situation as such. Mirative extensions of should, first attested after emotive predicates, may arise in argumentative contexts, tracking preexisting counterexpectations.

We can now compare should with would to see if they have similar mirative extensions. Jacobsson (Reference Jacobsson1988: 81) notes that would and should appear in the same syntactic environment, with should being more frequent in British English and would in American English. After ‘it was inevitable’, would alternates with should in both varieties.

Though not factive, the adjective inevitable used in a preterite matrix clause (it was inevitable) signals that the embedded situation occurred out of necessity, with the past tense conveying a posteriori knowledge. Should is mirative and dependent on the matrix evaluative judgement:

Should signals that having debts results from a fatal necessity inherent to poets. Though generally undesirable, it is a necessary condition to qualify as an artist. At the discourse level, accepting this necessity explains the bills’ presence, marking a cause-consequence relation via modal reasoning.

In contrast, would differs from should due to its temporal profile and may appear in an independent clause:

Non-epistemic would in subordinate clauses retains its dynamic reference to predictable past situations. The matrix factive predicate can be removed because it does not conflict with the factual content.

Nonetheless, would is more ambiguous than should: it may also have mirative uses, where the preterite conveys modal remoteness, especially under predicates expressing surprise. Mirative extensions arise in two ways. The content may be counterexpectational:

Here, suicide is a plausible cause, but not assumed by the matrix subject. The evaluation signals counterexpectation.

Or the mirative extension may be evidence-based, when contextual evidence contradicts expectations:

In (26) and (27), the embedded situations are factual. The role of the preterite would is unclear. One might suggest that the preterite is due to backshifting. However, such an explanation does not hold for would embedded under a present predicate:

Present tense in the matrix clause in (28) and the verbless sentence in (29) indicate that the evaluative judgement concerns the present. The modal conveys a present perspective. Conceptually, however, it is difficult to classify this use in terms of modality. It resists paraphrase with the epistemic adverb probably. This recent use, first attested in American English, is not documented in reference grammars. Coates (Reference Coates1983: 208) only acknowledges epistemic would when a judgement is formed about a past situation:

Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 200) regard preterite would as tentative (see (13a)), but as noted in Section 1.1, would also appears in factual contexts with full speaker confidence, corroborating Ward (Reference Ward, Galeano, Görgülü and Presnyakova2012) that would has a new use. Spears (Reference Spears1973: 637) and Jacobsson (Reference Jacobsson1988) already noted ‘factive would complements’.

Factual would presupposes the truth of the complement proposition, usually based on context. In (26)–(29), the speaker’s judgement relies on objective evidence that is available to any participant in the speech situation. This evidence may be an event (Salem snoring, only one priest being present, the subject referent’s presence) or a previous speech act as in (29). In each case, this objective evidence is found to be surprising, which is conveyed by the matrix predicate. Would in the embedded clause signals conflict between the experiencer’s expections and reality. This mirative extension indicates how the experiencer updates their information state. Here, evidence forces a claim on a state of affairs contradicting expectations. The modal does not signal weakened confidence in the truth of the content, but indicates discordance, hence difficulty in assimilating information that is not fully in the Common Ground. The ‘vague element of tentativeness, diffidence, extra politeness’ postulated by Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 200) applies at the discourse level.

In sum, there are two meanings of would in content clauses. First, non-epistemic past would refers to predictable past situations; its factual nature aligns with the matrix factive predicate. Second, mirative would marks modal remoteness. The modal may indicate the counterexpectational character of a content the experiencer does not fully commit to. If objective evidence is available, the judgement of incongruity marks the speaker’s tentative attitude regarding the discursive integration of unexpected information. The boundary between these meanings may blur under a factive matrix predicate. In (26), for instance, the matrix evaluation generalises from a specific situation. Using he instead of someone allows a different reading:

Direct reference to a specific referent shifts the evaluation to the subject’s ‘perverse’ disposition,Footnote 5 possibly independent of the matrix clause. The ability of would to refer to past or present and convey predictability or mirativity explains overlap between (26) and (26a).

Finally, in the grammaticalisation of modality, dynamic modality precedes epistemic modality and postmodality (Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994, van der Auwera & Plungian Reference Auwera and Plungian1998). Gisborne (Reference Gisborne2007: 55) further notes that as a subtype of dynamic meaning, the propensity sense of modal will is an intermediate stage. Dynamic meaning is ‘attenuated by virtue of the generic interpretation’. The predictability sense of would allows a semantic shift from dynamic to epistemic modality and postmodality, exploiting its ambiguity in factuality. Originally, dynamic would refers to factual past events, whereas epistemic would is non-factual. A factive matrix predicate foregrounds factual evaluation, weakening the force of epistemic would and overriding its unreality presupposition.

To conclude this section, factive predicates presuppose that the embedded content denotes a factual state of affairs. This presupposition does not conflict with predictability would, which retains its meaning under a factive predicate. The situation differs with should and epistemic would. The factive presupposition conveyed by the evaluative predicate overrides the unreality implication of these modals, weakening their force. The residue of this negative bias results in a mirative extension in the postmodal domain. Importantly, the mirative extension preserves features of each modal’s original semantics. With should, fatal necessity is recycled at the discourse level to mark contradiction between propositions, encoding processing of backgrounded information from mental resistance to mental acceptance (Arigne Reference Arigne2017).

With would, a judgement of incongruity arises from conflict with prior expectations or contextual evidence. The mirative extension of would coexists with its propensity meaning. The rich semantic profile of would – i.e., its ability to refer to past and present, to reason forward from cause to consequence and backward from consequence to cause – may explain why it has spread into syntactic positions traditionally reserved for should (Jacobsson Reference Jacobsson1988: 84). I argue that pragmatic factors also drive this evolution.Footnote 6 Evaluative factive predicates cancel the unreality implication of should and epistemic would, weakening their modal force. The resulting negative bias gave rise to mirative extensions now routinely associated with content clauses. Grammaticalisation theory supports this, proposing that ‘inference or the conventionalization of implicature’ drives meaning change (Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994: 25).

Specifically, it is not just the meanings of would and should that grammaticalised, but their meanings in content clauses. Under a factive predicate, should implies contradiction. Once associated with content clauses, mirative meanings may become independent of a matrix predicate (Arigne Reference Arigne2017).Footnote 7 In contrast, would, with its temporal ambiguity, does not necessarily encode a specific mirative meaning.

Mirative extensions of should and would are also possible in other contexts, allowing similar inferences. I have identified two such contexts that promote semantic change by precluding the unreality implication of would and should: open questions and their answers in the form of TWBX. Corpus data can now help investigate how these mirative extensions are entrenched in pragmatically constrained patterns.

3. Why-Should and Why-Would Questions

This section discusses the mirative extensions of would and should in why-interrogatives. Both modals show comparable uses in content clauses and open interrogatives. Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 188) note that ‘emotive should is also found in main-clause interrogatives with the force of rhetorical questions’. Jacobsson (Reference Jacobsson1988: 80; 82) similarly argues that rhetorical should (e.g., Why should he resign?) developed into the meditative-polemic should in content clauses, and that factual would derives from hypothetical would in why-interrogatives. On this view, the complementation meaning represents the final stage of grammaticalisation into the postmodal domain.

My aim, however, is not diachronic. Rather, I explain why the mirative extensions of would and should arise in certain contexts and why these extensions are not as likely as in complementation position. So far, we have seen that should is always mirative under evaluative factive predicates, whereas would is ambiguous between predictable and mirative readings. Both modals appear sensitive to speech act contexts: questions, like factive predicates, may block the unreality implications of should and non-dynamic would. Open interrogatives may therefore provide conditions similar to factive predicates when they presuppose the actualisation of an event.Footnote 8

A corpus study was conducted to determine the frequency and context of mirative should and would in why-interrogatives. A random sample of 200 why-should and 200 why-would interrogatives was extracted from the English Web 2021 corpus (enTenTen21)Footnote 9 using Sketch Engine. The meanings of would and should were coded so as to capture functional similarities across contexts that induce variation in why-questions.Footnote 10

Should was coded as deontic (31) or as epistemic necessity (32) when modality is presupposed:

Should was coded as discordant when modality is challenged:

In the mirative use, modality is also challenged, but the context is factual:

Would was coded as directive in negative questions introducing an invitation to act:

It was coded as discordant when the logical character of a content is challenged:

It was coded as mirative when the question contradicts the speaker’s expectations in a factual setting:

3.1 Quantitative results

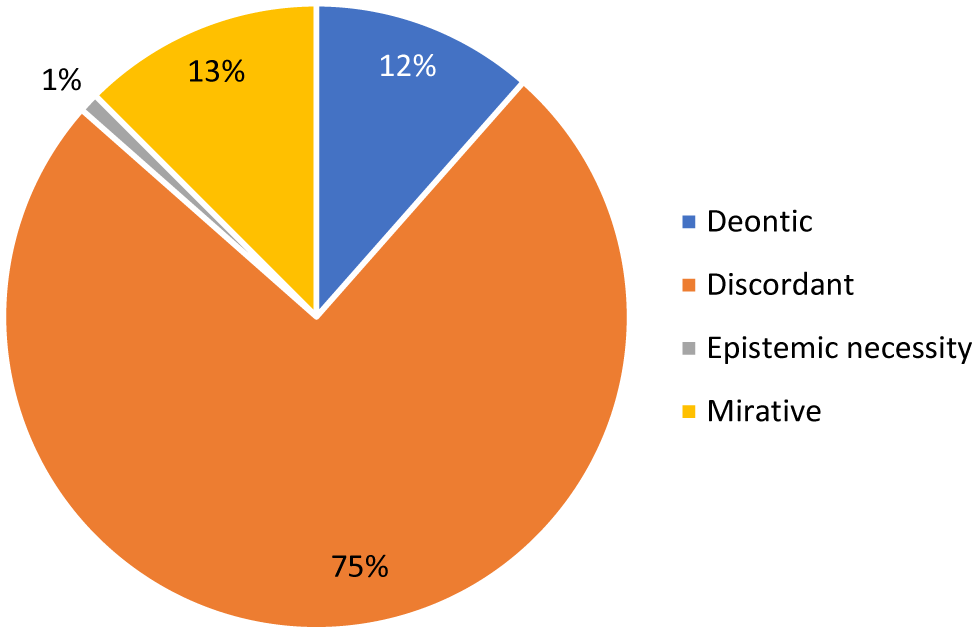

Why-should questions show four meanings (see Figure 1). The primary meanings are relatively infrequent: deontic should accounts for 12% and epistemic should for 1%. The most common meaning is discordance. The mirative extension represents 13%.

Figure 1. Meaning distribution of why-should interrogatives.

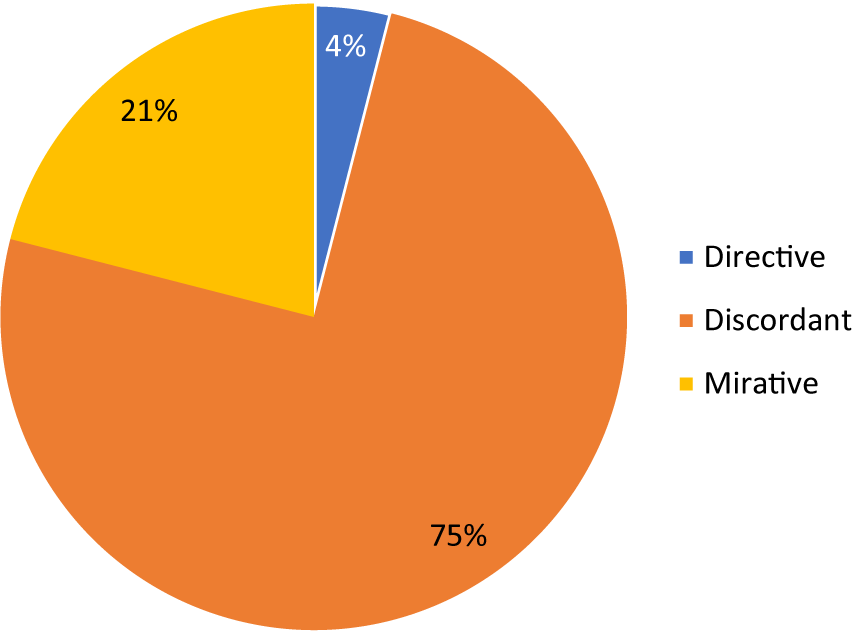

As illustrated in Figure 2, why-would questions show a mirative extension in 21% of cases – higher than for should. Discordant uses dominate (75%), and 4% of negative why-would questions are directive.

Figure 2. Meaning distribution of why-would interrogatives.

3.2. Qualitative analysis

3.2.1. Primary meanings of should and would

Overall, should retains its primary meaning more often than would in why-questions, although these uses are in the minority. The mirative meaning is more frequent with would. Primary uses require pragmatic conditions in which necessity or volition is presupposed as part of the speaker’s a priori knowledge, as in (31)–(32). The primary meanings of should typically arise in non-interactional instructional settings, where an informative answer is expected to be provided by the speaker:

Here, necessity (moral or epistemic) is presupposed, and the question requests its justification. Although compositionally transparent, these questions are non-canonicalFootnote 11 because the speaker is knowledgeableFootnote 12; the necessity is not at issue, only its grounds. By uncovering these grounds, the speaker aims to convince the addressee of the presupposed necessity.

Negative why-would questions with directive reading, e.g., (35), do not ask for reasons but issue invitations to act:

An unrealised event is tentatively suggested as desirable: why would you not p means you should p. Arguably, the volitional meaning of would plays a role in the emergence of this meaning. However, the conventionalisation into a directive speech act is accompanied by a subjectification process of the dynamic meaning. While the modal is syntactically linked to the subject, the volitional behaviour is semantically transferred to the speaker.Footnote 13 Overall, the primary dynamic meaning arises when the content is discourse-new, while mirative extensions arise when the content is discourse-old.

This indicates that information structure and context determine question type and modal meaning. Under a constructionist approach, such questions would be viewed as constructions. As a test for constructional meaning, Hilpert (Reference Hilpert2019) puts forward four criteria: deviation from canonical patterns, noncompositional meaning, idiosyncratic constraints and collocational preferences. However, these criteria might be evidence of meaning change, which does not necessarily entail constructional status. I would suggest that there is a continuum from meaning variation and change to constructions. Why-questions with primary modal meanings are non-canonical questions. However, the meaning of should in these questions is compositionally transparent, which does not seem to be compatible with a constructional status.

3.2.2. Discordant uses of should and would

Most why-should and why-would questions (75%) convey a sense of discordance: modality scopes over a discourse-old content and the combination of modality with a why-interrogative cancels the normal question-answer presupposition. As Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 900) put it: ‘the question is used without the presupposition that characteristically accompanies a question’. The question challenges the necessity of p:

By questioning the necessary character of the view that the multicultural literature approach reduces literature to sociology, the why-question implies that there is no reason for that necessity. What follows is not an answer to the question, but a counterargument to the view challenged by the reason question.

Should generally conveys root necessity, as in (38). Necessity is attributed to some source other than the speaker, and the why-question challenges the justification for that necessity. Epistemic necessity is less frequent, the why-question implying the unlikelihood of a content:

Would, as in (36), has a similar effect on the illocutionary force of why-questions. Semantically, however, the modality type and the verbs attracted by each modal are related to the primary meaning of each modal. Be collocates with the predicative adjective different after should (why should it be any different?) and with comparative adjectives (why should World 6 be harder than World 7?). Conversely, after would, be collocates with adjectives that denote a disposition of the subject (why would he be interested, inclined, involved, able to…). Similarly, verbs that denote a disposition of the subject (bother to, want, need) co-occur with would, while verbs that denote a mental or moral attitude (expect, believe, trust) or that express obligation tend to co-occur with should (have to, be allowed, be + past participle in the passive voiceFootnote 14). Modal-verb collocations are in harmony with the modals’ primary semantics. In order to challenge the dispositions of a subject, would will be preferred to should:

These dispositions – here a need or volition – are hypothetically attributed to a subject referent and at the same time discarded by the why-question. The question implies that in reality, there is no reason to want to live somewhere where it snows (40), and no need for computer assistance (41).

In sum, discordant questions hypothetically attribute modality only to deny it: not(modality) p is implied and the why-question attempts to instantiate a variable that cannot be instantiated. These questions are conventionalised rhetorical questions that cancel the question-answer presupposition. However, even in such non-canonical questions, collocation patterns are in modal harmony with the original semantics of each modal, which suggests that the primary meanings of the modals persist within context-induced conventionalised patterns.

3.2.3. Mirative extensions in factual contexts

Mirative should and would occur in factual contexts where p is already established. This is much more frequent with would (21%) than with should (13%). Like discordant uses, these questions refer to discourse-old information, but p is factual. The modal conveys an emotive, counterexpectational meaning:

In (34), it is clear from the preceding statement that the gold interest rate is higher than that of the dollar. This knowledge is shared by speaker and addressee. The question seeks to elucidate the reason for that counterexpectational state of affairs. The answer resolves the conflict and permits belief revision.

In (42), should have refers to the past and communicates that the choice of Fate contradicts the speaker’s expectations. The factual context makes the counterfactual reading impossible, as in content clauses embedded under a factive predicate:

The modal encodes epistemic biasFootnote 15 by conveying counterexpectation. The answer to the question resolves the conflict and p can ultimately make its way into the Common Ground in (34) and (42). However, the sense of contradiction is often supported by other elements than should, such as when-clauses that denote contrary evidence. If contrary evidence conflicts with p, the question implies that there is no reason for p:

In light of conflicting evidence, the question is evidentially biased toward a null answer, implying that there is no reason for Kashmir to lag behind. The question-answer presupposition is cancelled, as in the discordant use. The information update requires removing p from the Common Ground.

In factual contexts, why-should questions are thus biased questions that are compatible with either an information-seeking reading or a rhetorical reading, depending on bias type. If questions exhibit a conflict with prior expectations, i.e., if they are epistemically biased, they seek to instantiate the value of the wh-variable. If, on the other hand, they exhibit a conflict with contrary evidence, i.e., if they are evidentially biased, they are skewed toward a rhetorical reading, implying that there is no reason for p. In this respect, why-should questions differ from why-would questions, which are not compatible with contrary evidence on the mirative construal:

In (43a), as in (36), the why-would question can only be construed as a rhetorical question, stressing the discordance between a hypothetical situation and the real world. In other words, the inferential process is sensitive to evidence, and contrary evidence renders the situation unreal. In factual contexts, the mirative extension of would may only result from a conflict between a fact and prior expectations, as in (44) and (45):

In (44), the why-question refers back to the previous statement (the lab said). It asks for the reason for the content of the quotation. The statement that follows the question indicates that evidence is sought to ratify that past claim. In (45), the questions are anaphoric to the admission that fencing was installed around a rescue camp. The questions seek the reason for that fact, which contradicts the belief that a rescue camp is open to refugees. The answer provides an explanation that allows resolving that apparent contradiction by recomputing the definition of a rescue camp. The expectation that fencing is not needed may be revised if a rescue camp is redefined as a prison. In both (44) and (45), the responses to the questions resolve the epistemic contradiction, allowing p to become part of the Common Ground.

The contrast between the mirative extensions of would and should stems from their distinct modal profiles: would is fundamentally factual, whereas should is putative. In factual contexts, a why-should question distances p from its reference frame to assess its relevance in the discourse. Rather than encoding a fact, should conveys the speaker’s representation of a fact by indicating that the necessity of p is being evaluated. Would, by contrast, extends miratively from an established fact judged to be counterexpectational. As a result, why-would questions place such a fact under scrutiny not to challenge its factual status, but to address the issue it raises; they aim to instantiate the wh-variable and cannot be interpreted rhetorically.

In factual settings, both modals yield mirative readings when expectations clash with actual circumstances, but they do so in different ways. With should, mirativity arises from a conflict between necessity and prior expectations, prompting a why-should question to examine the relevance of p. With would, mirativity arises from a discrepancy between a fact and the speaker’s expectations, leading the question to seek the rationale for that unexpected fact. This distinction likely accounts for the high frequency of would in why-questions involving purely epistemic reasoning, where the communicative goal is to revise expectations in light of a surprising event.

4. ‘That Would Be X’: A Mirative Extension as a New Postmodal Meaning

We can now turn to the use of would in equative constructions. Adopting a postmodal perspective, my analysis diverges from Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Birner, Kaplan, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003), Birner et al. (Reference Birner, Kaplan and Ward2007) and Ward (Reference Ward, Galeano, Görgülü and Presnyakova2012). I argue that this use represents a mirative extension of epistemic would. Consider (27) and (27a)-(27b), to compare the paradigm of mirative extensions:

Under Ward et al.’s (Reference Ward, Birner, Kaplan, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003) account, would is epistemic in (27b) and this meaning is said to occur only in independent copular clauses of the form That would be X. They propose three conditions (2003: 76): a salient open proposition, instantiation of its variable with a discrete member of a salient set, and a conventional implicature that the resulting proposition is conclusively supported by objective evidence.

However, this postmodal meaning is not restricted to copular sentences, as shown in earlier sections. The requirement of a salient open proposition therefore does not hold for all uses, though it certainly facilitates mirativity in independent declaratives. I agree, however, that objective evidence supporting a factual reading is needed.

To determine the frequency and conditions of use of the TWBX construction, I searched the TenTen corpus for the string following question marks. From a random sample of 200 examples, I manually removed one that contained a that relative clause and coded would using three labels:

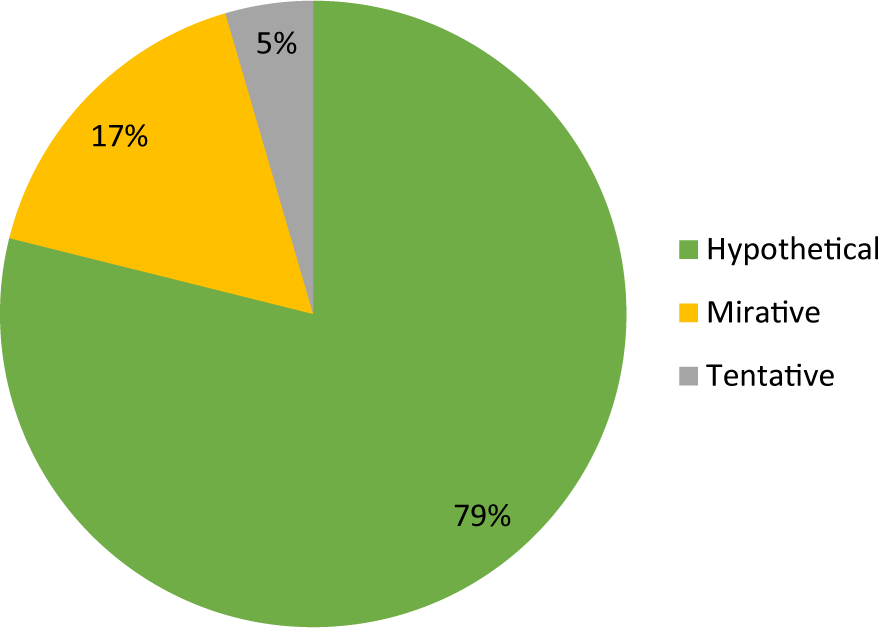

The results are shown in Figure 3. Hypothetical readings constitute 79% of all occurrences of that would be X after a question mark. Tentative uses account for 4%, and mirative uses for 17%. This indicates that the mirative reading is productive – more frequent than in why-should questions and less than in why-would questions. Although this rate is not significantly different from mirative would in why-would questions or from mirative should in why-should questions, the categorical availability of only would provides evidence that the mirative reading of would is becoming conventionally associated with the TWBX construction.

Figure 3. Meaning distribution of TWBX.

I first explain why this construction can be treated as a mirative extension of epistemic would, then examine some conventionalised patterns that reinforce this interpretation.

In (48), the speaker expresses strong confidence in the proposition, supported by ‘objective evidence’. In such uses, Ward (Reference Ward, Galeano, Görgülü and Presnyakova2012) argues that ‘the speaker is making a commitment to the truth of the proposition expressed’. In Ward’s experimental data, participants associated unmodalised equatives (that’s John) with lower certainty than modalised ones (that would be John). This contrast requires explanation.

The TWBX construction occurs in contexts that presuppose the truth of the modalised proposition. Preceding questions typically create such contexts. Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Birner, Kaplan, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003) note that TWBX usually answers a wh-question presupposing that its variable can be instantiated, as in (48). It may also respond to a rising declarative biased toward a positive answer, as in (49):

Or it may answer a directive presupposing the existence of an entity whose identification is delayed:

In all these cases, an expectation is assumed on the part of the addressee. Would marks that the answer is counterexpectational. In (48), Santorini is presented as unexpected new information. In (49), the speaker acknowledges that her being the new doctor is perhaps unexpected. In (50), the speaker anticipates the addressee’s surprise. The conflict between the speaker’s certainty and the assumed unexpectedness of the information disclosed to the addressee heightens the salience of that certainty, which may explain why modalised equatives received higher certainty ratings in Ward’s (Reference Ward, Galeano, Görgülü and Presnyakova2012) study.

While the truth of the proposition is in no doubt, the speaker’s stance may still be considered tentative (see Section 2.2) insofar as the modal signals uncertainty about how counterexpectational information will be integrated into the Common Ground. Would acknowledges that successful assertion requires the addressee’s uptake; the utterance therefore functions as a proposal to update the Common Ground.

In my data, the strings most frequently interpreted as TWBX are those with the complement pronoun me or a number as the postcopular constituent. That would be me has become conventionalised as a response indicating both certainty about self-identification and awareness that this information may run counter to the addressee’s expectations, often yielding a humorous or provocative effect.

This conventionalisation follows from inferential judgement based on readily available evidence: in that would be me, the inference rests on self-knowledge; with numbers, it results from objectively verifiable calculation, as in (51) and (52):

The mirative extension reflects the speaker’s recognition of the addressee’s expectations. It arises from the tension between contextual evidence and the anticipation that the information shared cannot simply be taken for granted. Conventionalisation is driven by the inferential process, which becomes part of the construction’s meaning. The more objectively verifiable the evidence, the more conventionalised the mirative reading. That would be me may thus function as a formulaic phrase incorporating contextual inference (Bybee Reference Bybee2010: 52). Stored as a phrase, it can be used whenever the speaker’s assertion is both self-evident to the speaker and assumed to be counterexpectational to the addressee. This development aligns with the pragmatic strengthening described by Traugott (Reference Traugott1989: 50–51) as characteristic of epistemic modal auxiliaries. Mirative extensions concern what Traugott terms ‘the strategic negotiation of speaker-hearer interaction’, and meaning construction can thus be understood as arising from this interactive process.

5. Discussion

The postmodal uses of should and would point to meaning variation and change. I have distinguished between the grammaticalisation of units in backgrounded contexts and the constructionalisation of units in focal contexts.

The development of mirative extensions under factive predicates corresponds to a well-known crosslinguistic phenomenon. Heine (Reference Heine1993: 31; 40) identifies a set of cognitive event schemas that constitute sources for the grammaticalisation of modal auxiliaries. One of these is the evaluative schema: ‘it is X (that Y)’.Footnote 16 Under such predicates, the modals are the grammaticalised outcomes of an evaluative pattern. I argue that the outcome is a mirative extension if the predicate is factive. However, the nature of this outcome is language-specific. According to Narrog (Reference Narrog2005: 167), such patterns raise the issue of the boundary between modality and mood. In some languages, such as French or Spanish, the subjunctive is used in embedded position to mark ‘notions that are, at least traditionally, not identified with modality, such as states-of-affairs that the speaker/writer assumes are already known by the hearer/reader’ (my emphasis). In Narrog’s example Me alegra que sepas la verdad ‘I am glad that you know the truth’, the subjunctive encodes a reality presupposition. In English, the use of modals in embedded position in factual contexts may support Narrog’s idea that modality and modal forms are not systematically co-extensive. However, postmodality may provide a better frame to handle such grammaticalised uses in a unified way.

Factual contexts override the unreality implication of should and non-dynamic would. This is typically the case in content clauses embedded under factive predicates. In such contexts, the modal force of deontic and epistemic necessity weakens and mirative extensions emerge through inference as residues of negative bias. These extensions encode counterexpectation, an epistemic notion. As Plungian (Reference Plungian, Gabriele and Elena2010: 47) notes, mirativity is ‘undisputedly modal, since it reflects one of the various kinds of epistemic evaluation, namely a contradiction to the expectation of the speakers, or, in other words, the fact that the speakers were not prepared to cognitively process the situation they observed’. At the same time, mirative readings also result from contextual evidence that induces inference. Jacobsen’s (Reference Jacobsen1964: 630) description of a Washo suffix illustrates this: ‘the speaker knows of the action described by the verb, not from having observed it occur, but only inferentially from observing its effects. It thus commonly conveys an emotion of surprise’. This abductive reasoning – from effect to cause – is available only with would. Should cannot support backward inference from present evidence, and this semantic difference shapes their postmodal behaviour. With would, contextual evidence enters the context set and prompts expectation revision. In mirative why-would questions, the speaker searches for grounds that justify p. In the TWBX construction, the speaker makes a proposal while signalling that its acceptance depends on the addressee’s willingness to revise their prior expectations.

This semantic difference also explains why only would appears in the TWBX construction. Postmodal should in independent declaratives is rare, and its mirative extension differs from that of would:

The meaning of should could easily be glossed in the following way:

As discussed in Section 2.2, should contributes to discourse cohesion by suggesting that a prior contradiction has been resolved so that p can now be accepted. In (53), so he should be presents the information as discourse-old and unsurprising, allowing easy integration into the Common Ground. Modality is not tied to the speaker’s here and now.

Consider now a scenario where a speaker identifies someone in a picture:

In (53b), the TWBX construction conveys discourse-new, foregrounded information. Because the addressee fails to recognise the person in the picture, the speaker anticipates surprise or reluctance to accept the assertion that’s me after three weeks’ holiday. This modalisation is forward-looking: the speaker anticipates that the addressee will need to revise their beliefs. Would thus signals that speaker commitment alone cannot guarantee the success of the assertion. As many authors point out (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg2012: 94; AnderBois Reference AnderBois2018), assertions propose information updates that require the addressee’s acceptance. Would marks the speaker’s awareness that such acceptance is not assured. An implicit if-clause restricts not the truth of the proposition but the success of the speech act – which, roughly, can be paraphrased with if you are willing to add this to your belief set. Footnote 17 Although non-volitional, this use draws on the primary meaning of would, metonymically recycled at the speech act level to yield a construction-specific function.

The TWBX construction shows a categorical restriction: would is permitted, while should is not. The new meaning of would in this construction is innovative in two ways. First, past modals generally evolve toward uncertainty (Ziegeler Reference Ziegeler2000: 28), but this construction does not express uncertainty, owing to would’s primary factual potential. Evidence-based judgement is central instead. Second, this construction qualifies the assimilation of discourse-new information in focal position, unlike postmodal forms in complement position, where information is backgrounded. This supports Bybee’s (Reference Bybee, Bybee and Noonan2002: 2; 12) view that main clauses foster innovation while subordinate clauses preserve older meanings. Postmodal forms in complement position show precisely such conservatism, often retaining redundant modality for ‘modal cohesion’ (Peltola Reference Peltola, Hilpert, Cappelle and Depraetere2021). By contrast, the TWBX construction is rooted in the speaker’s here and now and communicates that belief revision is needed to integrate new information.

The meaning of would here also shows that the postmodal domain is not merely the endpoint of grammaticalisation through semantic bleaching. It can produce new meanings not predicted by van der Auwera and Plungian’s (Reference Auwera and Plungian1998) semantic map, or by grammaticalisation theory more generally. Boye (Reference Boye2023: 289) defines grammaticalisation as ‘the conventionalization of discursively secondary status’ and most of the mirative extensions discussed fit this definition – except TWBX. Boye (Reference Boye2023: 174; 175; 178; 188) repeatedly notes that metalinguistic contexts override conventions, and thus fall outside his definition; these contexts are precisely the ones that drive constructionalisation. Would has developed a new postmodal function as a hedging device, restricted to the illocutionary level rather than the propositional level. This construction can be taken as a ‘new connection’ of a form and a meaning, following Diewald et al.’s (Reference Diewald, Dekalo, Czicza, Hilpert, Cappelle and Depraetere2021: 89–90) definition of constructionalisation.

The postmodal uses of should and would show that mirativity may arise from different modal domains. This aligns with Peltola’s (Reference Peltola, Hilpert, Cappelle and Depraetere2021) comparative findings for French pouvoir ‘can’ and Finnish pitää ‘should’ in subordinate position. As she notes (Reference Peltola, Hilpert, Cappelle and Depraetere2021: 175), unexpectedness can be profiled in various ways regardless of ‘the modal background of the postmodal auxiliary’ and of the ‘semantic variation in the (epistemic or axiological) lexical items of the matrix’, because ‘the postmodal auxiliary crystallizes the semantic link between these units’. The auxiliary recalls conflict and contradiction, contributing to discourse cohesion. Crucially, it appears when syntax or speech act structure limits speaker commitment: in backgrounded position, where information has low communicative value, in why-questions, which ask for an explanation for a counterexpectational situation, and in the TWBX construction, where the speaker anticipates the addressee’s difficulty in accepting the assertion. All these uses encode the speaker’s stance regarding the problematic acceptance of p. This supports the idea that expectation sensitivity (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmathforthcoming) drives the evolution of postmodal forms. Counterexpectation may be recalled under a factive predicate, made explicit in a question, or anticipated. In content clauses, a prior conflict is already resolved; in questions, belief revision is sought; in TWBX, would encodes the anticipation that counterexpectation will hinder the context set update. The resulting procedural meaning guides the addressee through the update process, supporting the view that mirativity encodes an illocutionary update rather than a propositional content (AnderBois Reference AnderBois, Todd, Sarah and Mia2014). It concerns the metacommunicative acceptance of counterexpectational information: in and of itself, that would be me does not convey surprising content, but signals the speaker’s awareness that the assertion requires uptake. This suggests that the rise of procedural meaning in a construction goes hand in hand with metacommunication.

6. Conclusion

This paper has examined the reanalysis of would and should as postmodal markers of unexpectedness. Mirativity was treated as a residue of negative bias in factual contexts that induce the cancellation of non-factive presuppositions. Mirative extensions may originate from different modal domains, yet they all involve illocutionary updating and speaker positioning.

In the postmodal domain, new meanings arise through interactions between discourse levels and a posteriori uses of modals. Postmodality emerges through both the primary semantics of modals and recurrent inference in specific pragmatic contexts. Primary meanings persist and shape new developments.

The postmodal domain includes grammaticalised patterns with weakened modal meaning in backgrounded contexts and constructions with new discourse functions in focal contexts. Should is confined to the former: because it is insensitive to evidence and incompatible with factuality, it is discourse-linked and cannot support speaker-anchored, here-and-now postmodal functions. Would, by contrast, can form evidence-based judgements and refer to past facts, enabling the innovative TWBX use. In this use, postmodal would indexes the speaker’s perspective and encodes an illocutionary update proposal. The grammaticalisation of the modal across pragmatically sensitive contexts paved the way for this constructionalisation.

Constructionalisation and the emergence of postmodal meaning proceed together, driven by pragmatic pressures to mark what interlocutors do not expect. New postmodal meanings do not emerge ex nihilo. They build on the primary semantics of the modals. This study thus supports the ‘meaning first hypothesis’ – the idea that ‘the main motivation underlying grammaticalization is to communicate successfully’ (Heine Reference Heine, Heiko and Bernd2018) and illustrates Haspelmath’s (Reference Haspelmathforthcoming) claim that ‘grammars code most what comprehenders expect least’.