1. Introduction

Grammarians and teachers would admit that modality is one of the most difficult areas to deal with in English grammar, and it is particularly difficult for learners of English to master this area of grammar. Modality can be achieved by different means (see, for example, Huddleston & Pullum, Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002; Lyons, Reference Lyons1977; Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985). The following examples illustrate modality by the use of words of various categories:

(1) Maybe you are right.

(2) You may be right.

(3) I think you are right.

(4) I am certain you are right.

Modality is a semantic category expressing possibilities, obligations, predictions, etc. Example (1) expresses possibility with the adverb maybe, Example (2) with the modal auxiliary verb may, Example (3) with the lexical verb think and Example (4) with the adjective certain. While Examples (1, 3, 4) are straightforward and learners of English understand them without much effort, Example (2), which involves the modal auxiliary verb, is quite tricky for them. Traditional accounts typically identify the various meanings of the modal auxiliary verb and assign them to major categories such as root/deontic/intrinsic, epistemic/extrinsic and/or dynamic modalities. Often, a modal auxiliary verb may show different uses and thus may belong to more than one category.

(5) You can go after you finish your assignment. (deontic modality)

(6) It can't be John at the door. (epistemic modality)

(7) I am sure you can finish the whole bottle of Scotch. (dynamic modality)

This poses a problem for learners of English as they will have to work out the meanings of the modal auxiliary used in the sentence in a certain context. This is also an issue that descriptive grammarians of English will have to deal with. Another related problem for grammarians is that some modal auxiliaries cannot be neatly classified into a category available. For instance, the modal auxiliary would expressing a past habit may not fall nicely into either deontic or epistemic modality according to its meaning.

(8) I would drink in that pub with my friends every weekend.

The modal would is also eccentric in the use of expressing a hypothetical condition, which makes it difficult to be classified into the major categories.

(9) If there were a mistake, we would be responsible.

The above discussion demonstrates the difficulties in the classification of modal auxiliaries into some theoretical categories, often termed the lexical approach or verb-centred approach, which has recently been criticized. A recent example of such criticisms can be found in Torres–Martínez (Reference Torres–Martínez2019) (henceforth TM).

This article can be regarded as my reaction to Torres–Martínez's approach to English modals and it argues for a lexical-constructional approach to English modal auxiliaries. Meanwhile, we propose that this model will be more useful to learners of English in that it avoids both over-generalization and under-generalization that a purely constructional model may tend to make.

2. The approach taken by Torres–Martínez (Reference Torres–Martínez2019)

For the last 30 years or so, the linguistic theory of Construction Grammar (for example, Fillmore, Kay & O'Connor, Reference Fillmore, Kay and O'Connor1988; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006; Hoffman & Trousdale, Reference Hoffman and Trousdale2013) has been influential not only in linguistic theorizing but also in applications to areas such as second language learning (e.g. De Knop & Gilquin, Reference De Knop and Gilquin2016). As such, TM advocates a model of English modals in a Construction Grammar framework arguing that ‘Construction Grammar can successfully account for underlying modality patterns’ (TM, Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 50). As noted, Construction Grammar produced fruitful results in linguistic descriptions of language and theoretical advances and it has paid particular emphasis on such areas of grammar as the verb meaning and argument structure constructions. With this in mind, TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 51) proposes an ‘embodied cognition’ model for English modals as they enter into the argument structure construction.

The thesis of embodied cognition is an important one in the cognitive linguistic enterprise and hence in Construction Grammar. While there may not be consensus among philosophers, psychologists and linguists about what the content of the hypothesis is, Evans (Reference Evans2007: 66) conveniently summaries it as the thesis that ‘the human mind and conceptual organization are a function of the way in which our species-specific bodies interact with the environment we inhabit’, which is similar to the quote from Yu and Ballard (Reference Yu, Ballard, Mix, Smith and Gasser2010) to which TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 51) refers. With this in mind, TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 53) argues for ‘the existence of modal ASCs’ (argument structure constructions) by giving Examples (3–10), all of which contain a modal auxiliary, for instance, TM's Example (8) Root Transitive (ability) (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 53), repeated as (10) below:

(10) . . . That poor little robot, and he couldn't find his dad (. . .).

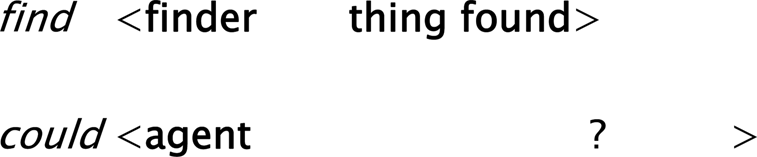

Embodied cognition, as TM argues, also interacts with the concept of agency, ‘a causal capacity, say, flexibly wielding means toward ends’ (Kockelman, Reference Kockelman2012: 1, cited in TM, Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 54). In other words, the agent has some control over the behavior and accounts for it. Couching in this concept TM also introduces the notion of Force as in Force dynamics (Talmy, Reference Talmy1988) . It is said that the agent or the subject of the modal sentence exerts some kind of force on the process or action designated by the main verb, which is illustrated in the diagram of TM's Figure 1 (TM, Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 54).

Figure 1. Argument structure of verbs

3. Concerns about TM's proposal

TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 50) argues for the Construction Grammar approach to accounting for the ‘underlying modality patterns’, which ‘can lead to distinct gains for both linguistics and second language acquisition research’. In this section we will see how fruitful his approach is towards these goals.

3.1 Verb meaning and argument structure constructions

It is legitimate to speak of the argument structure of the lexical verb such as find in (10) with the agent and theme (or undergoer) roles perhaps but what does it really mean if we assign the argument structure to the modal auxiliary?

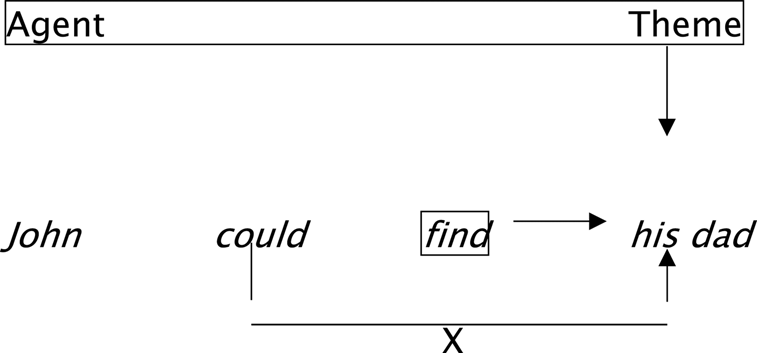

Figure 1 is a simplified way to represent the verbs’ participant roles. One can argue that perhaps the ability modal could assign the agent role to the subject assuming that he is in control of power. Yet, it does not make much sense to say that the modal assigns the participant role to the object in (10) because obviously, the role of the object is assigned by the main verb. Then, the participant roles are fused with the argument roles of the construction, which is governed by the Semantic Coherence Principle and the Correspondence Principle (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995: 50; 2006: 39–40). The former allows roles that are semantically compatible to be fused, and the latter allows a lexically profiled or expressed participant role to be fused with a profiled argument role of the construction. Thus, the question is whether the modal ASC can assign the argument role to the object of the main verb, while the main verb assigns the participant role to the object as in the following Figure 2:

Figure 2. The interaction between participant and argument roles

This diagram attempts to show that the participant role of the main verb find is assigned to the object and then it is fused with the argument role of the FIND-construction, while the modal could does not assign a participant role to the object of the main verb. Thus, the attempt to postulate modal ASCs will have to account for the semantics of the constructions.

What is, then, the meaning of modal ASCs? Should they have a single meaning or polysemous? It is not clear what TM would have said about this as this is a legitimate and theoretical question about a newly proposed construction.

3.2 Syntactic issues

The related problem is that the modal sentence contains a modal (with other optional auxiliaries) and a main verb and thus arguably, each verb can have their own argument structures. The syntactic issue is whether the sentence containing a modal auxiliary should be regarded as a ‘simple sentence’, which has been debated since the early days of transformational grammar (see, for example, Huddleston, Reference Huddleston1974; Palmer, Reference Palmer1974). The modal auxiliary must occupy the first position of the ‘complex’ verb phrase – Modal (Auxiliaries) Main Verb. This problem has some bearing on the postulation of modal ASCs.

Construction Grammar concerns itself with the argument structure of simple sentences (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006), and it advocates the scene-encoding hypothesis based upon simple sentences:

Simple clause constructions are associated directly with semantic structures which reflect scenes basic to human experience. (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995: 5)

Thus, in Example (10) there is a finding event, activated by the meaning of the verb find. Would we want to say that there is an ability (or a lack of ability) event with the modal auxiliary could? The syntactic status of the sentence enters into the issues of postulating modal ASCs. To take another example from TM, (5) Epistemic Intransitive motion (possibility), whose meaning, according to TM, is X may need to move to Z.

(11) . . . and you may need to get to Laramie in a hurry.

The motion meaning is conveyed by the verb get, not may or need, and should not be as a part of the modal ASC. Furthermore, what is Intransitive here is the verb get rather than the modal, which can actually be said to be Transitive as it takes or licenses a non-finite verb complement. Other examples of modal ASCs raise a similar issue. The modal ASC of (4) is called Epistemic Caused-motion (possibility), while the meaning of Caused-motion is expressed by the main verb.

(12) He must have taken her away from her home…

Similarly, the Root Intransitive motion (past habit) of (6) indicates the motion by the main verb go, as in (. . .) so we will go to my cousin's…

There is a further implication for the modal sentence to be a ‘complex sentence’ or ‘clausal sentence’ (Huddleston & Pullum, Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), that is, the modal auxiliary, arguably, takes a proposition conveyed by the main verb as its argument.

(13) will Semantics <agent proposition>

Syntax subject complement

If modal ASCs are postulated, they will have to deal with this situation, where a proposition is an argument, which will resemble cases such as those of think and say.

(14) John says/thinks [that he is the most knowledgeable man on earth].

This issue touches upon the fundamental principle of Construction Grammar as it readily deals with simple sentences rather than ‘complex’ ones. The formalization of Construction Grammar, for instance, using box diagrams indicating syntax and semantics, will also have to be revised or modified so as to accommodate the structural properties of modal ASCs.

3.3 Agency and force

In the schema for a modal clause (TM's Figure 1), TM (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik2019: 54) proposes there are ‘force-modal-full verb-scope indexical relations’, but these lexical relations do not seem to characterize the meaning of the construction per se. Assuming a force in the modal sentence seems to run into the risk of over-generalization about the meanings of the construction. It would make sense to suggest that deontic modality typically involves an agent or a force.

(15) You must wash hands before eating.

However, it may not accommodate the situation involving epistemic modality.

(16) That must be John at the door.

It makes no sense to say that there is a force involved in the situation of (16). The assumption of force also under-generates the meanings of particular modal constructions.

(17) You should have trusted me to finish the job. (TM's Example 13)

The modal should indicates ‘unfulfilled obligation’ with have + past-participial verb, which is not predicted in the overall meaning of the modal ASC. Comparing it with other modals with the same construction, we will notice the semantic difference.

(18) John may have come home last night.

In (18) the have + past-participial verb conveys the past time of the action (last night), while the modal may occupy the finite position and indicates the epistemic modality of possibility. It would be legitimate to assign descriptive labels to individual modal constructions such as the SHOULD-or MAY-construction, and yet it is a very different matter to postulate a construct as the modal ASC to achieve theoretical significance.

Furthermore, reference to the agency and accountability should be cautious. The concept ‘stative agency’ seems to be an example of an oxymoron. In TM's Example (14) (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 55), repeated here as (19), the agency or force is said to occur, according to TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 56), because ‘[t]he reader/hearer interprets the speaker's statement to be epistemically plausible (which entails that the speaker has control, composition, and subprehension of his/her evaluation)’.

(19) . . . even though Hammond must now be . . . what? Seventy-five? Seventy-six? …

However, what is debatable is what is meant by the statement that ‘the speaker has control . . . of his/her evaluation’. The understanding of control here appears to be so broad that it would be able to include all situations of affairs. The fact that the speaker has control of his/her evaluation is very different from the agent subject of the sentence or proposition to have control over the action or process denoted by the sentence. Whether the speaker can actually control his/her evaluation of the situation, and thus assuming his/her accountability, is also a philosophical question. What seems to be clear in (19) is that Hammond, the subject of the clause, has not control over the predication ‘must now be . . . what?’, let alone his/her age!

3.4 Embodied cognition

As noted above, embodied cognition involves the environment in which human activities take place and the conceptualization of such activities. It makes sense to ask what kind of embodied cognition is activated or motivated by modal ASCs. Since we have pointed out that identifying a particular semantics for modal ASCs is difficult, it follows that it is equally, if not more, difficult to identify the kind of embodied cognition a modal auxiliary or a modal ASC can activate.

TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 51) provides Example (2) with the verb give to suggest that ‘ACSs reflect some sort of embodied cognitive substrate that interfaces mental processes with our physical experience with the world’ (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 52). It is true that the giving event activates the semantic frame of give with the three participants in the event, namely, a giver, something given, a recipient. It is also this main verb that is directly connected with the argument structure of the construction, which enters into the relation with embodied cognition. However, with the modal auxiliary in the sentence, what embodied cognition will be contributed by the modal auxiliary? TM further claims that ‘modal auxiliaries are, too, analyzable against the backdrop of the ASCs in which they are used’ (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 52). To do this, TM shows his Examples (3–10), ‘regardless of the modal meaning involved’, and says that ‘the syntactic construction contributes its specific meaning to render the clause understandable’ (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 52). While we agree that the construction specifies the meaning of the clause, it is the sentence with the modal auxiliary that is at issue here. Otherwise, what is the difference between a sentence with a modal auxiliary and the one without? After all, it is the aim of TM to propose the modal ASC.

Furthermore, would our understanding of the world be very different with or without the modal?

(20) He didn't find his dad.

(21) He couldn't find his dad.

Would the embodied cognition of the sentences (20) and (21) be different?

3.5 Second language acquisition

While the syntactic form of the modal sentence is not difficult to learn, it is the meanings of the modals that learners of English find it difficult to master. In terms of second language learning, would learners of English have different embodied experience with the world when they learn the uses of modal auxiliaries? To give an example, Chinese learners of English could use the following sentence to refer to either (20) or (21) conveniently:

(22) Ta zhao bu dao ta de fuqin.

he find not arrive he of father

‘He didn't find his dad.’

‘He couldn't find his dad.’

Would embodied cognition, as it is understood here, facilitate the learning of modal ASCs in English by Chinese students? This issue also touches upon the hypothesis of linguistic relativity, if one considers the application of the theory to learning English as a foreign language.

However, TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 52) is cautious to suggest that ‘both modal-and full-verb semantics can be generalized as a result of their combined meanings’. Thus, the so-called ‘modal ASCs’ are basically units combining the modal auxiliary and the main verb, constituting predictable semantics. If learners of English first learn the meanings or uses of the individual modal as in the verb-centred approach, would they not be able to deduce the meanings of the entire sentence by knowing the meanings of the components? If we understand the meaning or use of the modal could and the meaning of find in the (21), would we not be able to understand their compositional semantics?

Yet, following the principle of Construction Grammar (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006), TM (Reference Torres–Martínez2019: 56) also maintains that ‘some modal ASCs make up fully predictable patterns that are frequent enough to be stored in and retrieved from the construction’. Certainly, the modal auxiliary frequently occurs in daily discourse, but would learners of English be better off knowing the semantics of individual modal auxiliaries before they could recognize such a construction as the modal ASC? In other words, the traditional lexical approach still plays an important role in learning the meanings and uses of English modal auxiliaries.

Another difficulty for learners of English, as mentioned above, lies in the assumption that there is an (albeit abstract) agency or force governing the evaluation of the situation in epistemic modality. It is not easy for learners of English, whose cultural backgrounds are diverse, to understand that in the epistemic uses of the modal auxiliaries the speaker/hearer will be an agent or force, when there is no physical connection involved. This seems to create an extra level of burden for learners when they already need to deal with the semantics of modal auxiliaries. This may seem to be an over-generalization for learners to understand the meanings of modal auxiliaries.

4. Conclusion – we need lexical-constructional information

The above discussion, in relation to TM's approach to English modals, is meant to provide a meaningful and fruitful exchange. As a theory of knowledge of language, Construction Grammar has been proven useful in linguistic theorizing and descriptions, as well as language teaching and learning (see, for example, De Knop & Gilquin, Reference De Knop and Gilquin2016; Hoffman & Trousdale, Reference Hoffman and Trousdale2013). Applying such a model to the area of English modals is legitimate and interesting, and yet, the following issues should be taken into account if such a model is to be successful.

While recognizing the construction as a theoretical entity helps us in analyzing many aspects of language, lexical information is vital in the full understanding of the entire construction or discourse or things like Jabberwocky may occur. The merits of the traditional lexical or verb-centred approach (e.g. Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999; Huddleston & Pullum, Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002; Palmer, Reference Palmer1990; Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985) include the meaningful classifications of modal auxiliaries into categories, which attempt to make sense of the different meanings and uses of the modal auxiliaries. These categories are semantically based, with sometimes fine-grained divisions into groups such as possibility, permission and volition. This approach assumes that each modal auxiliary denotes some kind of meanings, albeit less concrete, and it is consistent with Frege's Principle of semantic composition. Speakers of English of course have knowledge of the meanings or uses of modal auxiliaries and often they use the modal alone knowing what it means, given the appropriate context. In (23) the modal should obviously indicate obligation upon the subject. It is this meaning of ‘obligation’ that characterize the main use of should. Or in (23) the epistemic use of should can also be said to be meaningful (‘prediction, evaluation’, etc).

(23) A: I didn't write to dad.

B: You should.

(24) That should be John at the door.

In other words, there is a lot to be gained in the verb-centred approach to English modals, and it is particular noticeable when learners of English try to master the uses of modals. Simply presenting them with a seemingly theoretical overarching modal ASC may not help them understand the uses of the individual modal. Furthermore, it would not be necessary to assume that all sentences containing a modal auxiliary carry some sort of agent or force. The concern of agency and accountability is made clear to learners when they work out the content of the sentence. As in (24) learners would not need to assume that there is an agent or force in order to understand the sentence.

Nevertheless, the idea in Construction Grammar that learning a language should be learning linguistic chunks will be appropriate for learners to master modal expressions such as (24) when they can remember the chunk That should be . . . to typically indicate the speaker's prediction or evaluation of the situation. Then, learners can also make the generalization that any other modals that can occupy the same position in this chunk could convey the different degrees of the speaker's confidence in the truth of the proposition. Furthermore, the non-human subject should reinforce the idea that it is a prediction of the speaker and not somebody actually doing something. This is to say, again, that it may not be felicitous to assume the agent or force in this type of construction. Nonetheless, knowing the chunk of (24) is knowing the form-meaning pairing of that particular ‘SHOULD-construction’.

A related field of lexical semantic study is Frame Semantics (Fillmore, Reference Fillmore1982), which could offer us a way of looking at the meanings of modal auxiliaries in conjunction with Construction Grammar. One could treat the sense of the modal auxiliary to be realized in a semantic frame or ‘schemas’ activated in the mind of the speaker/learner. And the meanings of the modal auxiliary can be defined in terms of distinct frames or idealized cognitive models (Lakoff, Reference Lakoff1987). What seems to be beneficial in this approach is that meanings of modal auxiliaries are tied with our encyclopedic knowledge, and thus in (24) one will not be able to deduce any personal obligation from the subject That or even John!

A theory of English modals should allow one to understand and explain the individual meanings and uses of modals and how they interact with the sentence or construction as a whole. Learning of the uses of English modals must entail that learners master both lexical and constructional information of English modals. As in Construction Grammar, speakers possess the knowledge of language with constructions – form-meaning pairings. Thus, modal auxiliaries are word-level constructions while sentences containing them are phrase-level constructions, both of which contribute to the understanding of the uses of modal auxiliaries. Over-emphasis on either the word level or the phrase level of constructions would seem to miss generalizations that we could make. This is witnessed by such items as should have + past participial verb where one needs to know the meaning of the modal auxiliary and also the meaning of this specific construction. To sum up, understanding English modals entails the understanding of the modal meanings and the meanings of the constructions in which they occur. With the insights of Construction Grammar, a better approach to English modal auxiliaries is on the horizon.

RONALD FONG is Assistant Professor of English Linguistics at the University of Macau, who is interested in syntax-semantics interface, Construction Grammar and English as a Foreign Language. He has published articles in these fields and a recent monograph on the Chinese Resultative Construction.

RONALD FONG is Assistant Professor of English Linguistics at the University of Macau, who is interested in syntax-semantics interface, Construction Grammar and English as a Foreign Language. He has published articles in these fields and a recent monograph on the Chinese Resultative Construction.