We are living through a watershed era... The issue at the heart of this is whether power is allowed to prevail over the law. Whether we permit Putin to turn back the clock to the nineteenth century and the age of the great powers.

—Olaf Scholz, 2022Footnote 1History will measure [Germany’s] retribution [toward France]... by the intensity of the crime of reviving, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the policy of conquest!

—Karl Marx, 1870Footnote 2For many observers, we stand now at a crossroads in history. A crucial pillar of the post-World War II order, the territorial integrity principle (the prohibition of territorial conquest) is at risk. Russia is engaged in a bloody war of conquest against Ukraine, while the US president has threatened to take over Canada, Gaza, Greenland, and the Panama Canal.Footnote 3 It appears that what supporters of the current international order do next, whether it includes military support for Ukraine, international legal innovations, or other policies, will affect whether or not that principle can be maintained much longer. Failing to respond appropriately might encourage China to invade Taiwan, or Russia to “grab northern Kazakhstan” or “formally annex Belarus.”Footnote 4

These considerations rely on particular ideas of how the territorial integrity principle developed historically. Often, as in the statement from former German Chancellor Olaf Scholz quoted above, the postwar era of territorial integrity is contrasted with a nineteenth-century era of relative violence and international anarchy, or, as Angela Merkel put it after the Russian annexation of Crimea, “the law of the jungle.”Footnote 5 Scholz’s historical narrative, which helped enact a “180-degree course correction” toward remilitarizing German policy, has been echoed in different ways by scholars.Footnote 6 Before the twentieth century, Hathaway and Shapiro argue, the “Old World Order” was based on the principle of “might makes right.”Footnote 7 For Hathaway, Donald Trump and his supporters are trying to hasten the return of a world in which “states could use force free of modern constraints.”Footnote 8 Fazal describes the war in Ukraine as “anachronistic” and “reminiscent of a more violent era,” warning that “the norm against territorial conquest” could end up as “another casualty of this war.”Footnote 9

Contrary to the assumptions of Scholz and many others, I argue that in the nineteenth century, power did not simply prevail over law. Instead, conquest was restrained by international law and order, though not in the same way as it is today. While European empires subjugated non-European peoples with brutal violence, they observed an “etiquette of thieves” among themselves, conquering no colonial territory from each other between 1815 and 1914. This etiquette derived initially from the Concert of Europe, based on a largely shared recognition of certain powers as charged with status and responsibility for upholding order. Within Europe, national liberation movements were one of the major reasons conquest remained an important feature of international politics; but in the colonies, Europeans lacked such systematic justifications for redrawing intercolonial boundaries by force. Then, over the course of the century, ideologies of civilization and free trade increasingly informed Europeans’ largely agreed notions of who had status and authority, and for what purpose, contributing to intercolonial cooperation despite the resurgence of imperial rivalries. The idea of “civilization” deeply structured social, legal, and political relations in the colonies, producing a double standard: law and order between Europeans on the one hand, and European domination of non-Europeans on the other. For these reasons, the nineteenth century differed from the eighteenth: war did not start in the colonies and spread to Europe. In 1914, war started in Europe and, despite the best efforts of many imperial officials, spread to the colonies.

In this essay I contribute to the territorial integrity literature, first by revising the scholarly “consensus,” as Goertz, Diehl, and Balas put it, that the territorial integrity norm “did not exist prior to World War I.”Footnote 10 This literature deals with the period before the norm in limited and varied ways, as it is mainly concerned with the norm’s effects, rather than its causes, but its tendency is to deny any effective constraints on conquest before World War I.Footnote 11 But this essay also expands discussions of the historical trajectory of constraints on conquest beyond certain limitations imposed by conceiving of them in terms of a “norm” rather than, for example, in terms of institutions or concepts.Footnote 12 Norms, according to Finnemore and Sikkink, are “single standards of behavior” and clearly distinct from institutions, which “emphasize the way in which behavioral rules are structured together and interrelate.”Footnote 13 Defined this way, a norm is more stable and more amenable to clear definition than an institution, which develops in complex ways historically. Zacher is clear and consistent that the “territorial integrity norm” means precisely “the proscription that force should not be used to alter interstate boundaries.”Footnote 14 Others allow more nuance but maintain a core norm prohibiting annexation by conquest, distinguishing this core from a periphery of debatable offences.Footnote 15

But this narrow focus on annexation by conquest risks leaving the picture very much incomplete. To begin with, it sits uneasily with international law, according to which territorial integrity “requires more than protection against permanent changes to borders, but demands protection against all sorts of interventions into a state’s territory from the outside.”Footnote 16 Abstracting the rule against annexation by conquest from the broader legal context has strong political implications; doing so was central to the US’s strategy for legitimating its conquest (but not annexation) of Iraq in 2003.Footnote 17

Moreover, it can lead to an oversimplified, binary view of change over time. Focusing on a universal “norm” against annexation by conquest, it does appear that conquest was far more limited after 1945. Many now fear that trend may soon be reversed. But if we abstract that rule from its broader context, we may lose sight of the fact that this is only one of many dimensions along which international orders vary historically with regard to the relation between force and law. As I will show, the difference between the nineteenth century and the post-1945 order is not that the latter was law-governed while the former was ordered by mere force. In the former, law and force were ordered through a racialized conception of “civilization,” which gave some stability to inter-imperial boundaries. By 1945, this was replaced with an absolute, universal prohibition of conquest between states, while at the same time, as Fazal has argued, this has encouraged states such as the US to engage in regime change.Footnote 18

From this perspective, the question scholars should ask is not whether the principle of territorial integrity will give way to a purely lawless world, but how recent events might lead to changes in the way the prohibition of conquest is understood and applied. This is not to say that Russia’s war of conquest, or the international response to it, will not change the global order. The point is that to understand how it might change the global order, scholars need to distinguish between the specific, absolute prohibition of annexation by conquest and prohibitions of conquest more generally.

Observing an Absence of Conquest

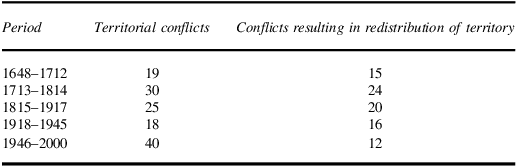

Between 1815 and 1914, European states never conquered territory from each other’s formally established colonies.Footnote 19 In the appendix I show in detail that a wide range of data sets and historical accounts confirm this claim. This absence of intercolonial conquest from 1815 to 1914 contrasts with a significant frequency of conquest within Europe during that period. In fact, the literature on the territorial integrity norm typically cites observations of conquest regularly occurring at least until World War I.Footnote 20 For example, Zacher’s data (Table 1) show conflicts that redistributed territory as a consistent feature of international politics from 1648 to 1945. Similarly, in Holsti’s reckoning, the eighteen intra-European wars of 1815 to 1914 contrast with zero European inter-imperial wars (Table 2). The Correlates of War Interstate Wars data show the same contrast.Footnote 21

Table 1. Zacher’s (2001, 218) Data on Interstate Territorial Wars

Table 2. Holsti’s (1991) Data on Wars and Major Armed Conflicts

The absence of nineteenth-century inter-imperial conquest also contrasts with the frequent wars over colonial territory in previous centuries. Holsti’s data exclude eighteenth-century intercolonial conflicts viewed as not fully linked to the European system, but they show a clear drop in intra-European “colonial competition” wars, from 14 percent of wars between European entities (in 1715–1814) to none (in 1815–1914).Footnote 22 In the next section I explain this absence of inter-imperial conquest.

Origins of the Etiquette of Thieves

The argument of this essay is that the normative and legal institutions that legitimated the territorial claims of European empires in the nineteenth century, taken together, are the main factor explaining the absence of inter-imperial conquest. Some of these institutions belonged to the European state system in general: a generic anti-conquest principle, a practice of fixed linear boundaries, and a principle of territorial inviolability. At the same time, within Europe itself, there were countervailing principles that legitimated compromises to these rules, particularly national irredentism. But because national irredentism was not a factor in the colonial sphere, the anti-conquest institutions of the European states system were at their most effective in the colonies. There were also institutions specific to colonialism because the main purposes of colonialism, namely commerce and civilization, were ideologically conceived such that there were good reasons to assume that war on and conquest of Europeans would be self-defeating.

The Concert of Europe

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars there emerged a club of great powers recognizing each other as having a collective right and responsibility to uphold a legitimate monarchical order.Footnote 23 No such mutual recognition of status had existed before.Footnote 24 Despite this, scholars of the territorial integrity norm have argued that “a norm permitting territorial acquisition through conquest was in place for much of history prior to” World War I.Footnote 25 In doing so, they tend to rely on the work of Sharon Korman. Yet Korman’s text on the right of conquest provides a good overview of the extent to which conquest was prohibited in European international law then.

First, as Korman shows, the European Concert system, “(or the ‘public law of Europe’ as it was also known) raised a strong presumption against unilateral changes in the status quo.”Footnote 26 This generic anti-conquest attitude has a long history, with roots in the Just War tradition, but it became institutionalized in the Concert system.Footnote 27 And even after the formal institutions of the Concert collapsed, great-power congresses continued to regulate territorial changes multilaterally, at Paris in 1856 and Berlin in 1878—the latter of which changed and superseded a bilateral Russian–Ottoman peace.Footnote 28 Unlike the eighteenth century, when the great powers had met the partitions of Poland with resignation, they protested Prussia’s conquests in 1864 and 1871.Footnote 29 And such protests mattered: in 1871, Bismarck annexed Alsace-Lorraine only after arranging for France to invade Prussia first, with the effect that “in the opinion of the day, France, for purposes of conquest, had entered on an unjustified war of offense.”Footnote 30 Even if some believed that states had an absolute right to initiate war without justification, states typically acted as if justification was necessary.Footnote 31

Second, states had a legal right of territorial inviolability, which prohibits any hostile activity inside a foreign state’s boundaries, including conquest.Footnote 32 International lawyers saw the 1842 Caroline case as the key moment at which territorial inviolability was recognized as an already established principle of customary law, when the US and Britain agreed that “respect for the inviolable character of the territory of independent nations is the most essential foundation of civilization.”Footnote 33 Linear boundaries also became widespread practice in Europe after 1815, and were globalized by the late nineteenth century.Footnote 34 Once a boundary is bilaterally agreed, revising it unilaterally is a breach of pacta sunt servanda, the fundamental principle that agreements are to be honored.Footnote 35 Lord Curzon, a prominent imperial expansionist, believed that the ongoing worldwide transformation of vague frontiers into precise boundaries was “undoubtedly a preventive of misunderstanding, a check to territorial cupidity, and an agency of peace.”Footnote 36

What, then, of the right of conquest? Many legal authorities denied its existence outright, at least as early as Pufendorf.Footnote 37 McMahon’s survey of jurists shows that while Anglo–American jurists agreed on the existence of the right of conquest, continental jurists were divided evenly, and—despite state practice in several nineteenth-century wars—South American jurists almost unanimously rejected its existence.Footnote 38 Moreover, the right of conquest has often been substantially misunderstood in hindsight. It was not a blanket right to initiate conquest, as it has often been portrayed,Footnote 39 but only a right to authority over a territory deriving from having already conquered it, whether legally or illegally.Footnote 40 For example, according to Phillimore in 1854, “great jurists of all countries have passed sentence upon the partitions of Poland,” which had become a classic case of illegal conquest.Footnote 41

Restrictions on Inter-European Conquest More Effective in the Colonial Domain

In spite of these legal and moral ideals, however, many conquests took place in the nineteenth century.Footnote 42 Here Korman and the territorial-integrity-norm literature agree, characterizing the nineteenth century overall this way because neither examines inter-colonial relations between Europeans in their own right. Instead, Korman concludes that colonialism demonstrates the continued relevance of the right of conquest in the nineteenth century.Footnote 43

Colonialism of course involved the conquest of colonized peoples and the denial of their sovereignty. But to explain their usurpation of sovereignty from peoples they colonized, Europeans claimed non-Europeans were “barbarous” and Europeans “civilized.” “Civilization” was a kind of status that built on the earlier forms of status that entitled the great powers to manage Europe as a Concert, but extending it to global dimensions, with an increased emphasis on cultural, religious, and racial affinity.Footnote 44 Throughout the century, Europeans identified the international legal community with the community of civilized nations. This was expressed most clearly in the 1899 First Hague Convention, which built on “the principles of international law, as have resulted from the customs established between civilised nations,” a formulation paralleled in many treaties of the era.Footnote 45 John Stuart Mill believed that one could never “characterize any conduct whatever towards a barbarous people as a violation of the law of nations.”Footnote 46 Relations among Europeans, then, would be based on a different standard of appropriate behavior than relations between Europeans and non-Europeans.Footnote 47 Acting on this double standard, Europeans, despite national antagonisms, exhibited what might be called an “etiquette of thieves,” cooperating with rival Europeans while imposing their rule by force on non-Europeans.

The idea of the civilizing mission, entailing an improvement of colonial living conditions through law and order, technology, Christianity, and so on, came to provide the most systematic legitimization strategy for nineteenth-century colonialism.Footnote 48 For example, the British spent extensive resources on extremely precise triangulation surveys in India that had no clear purpose other than to demonstrate scientific capabilities, and thus legitimize colonial rule.Footnote 49 One reason this was crucial was that, particularly early in the century, liberal-minded Europeans often worried about the legitimacy of conquering new colonies, even while ultimately supporting it.Footnote 50 Alexis de Tocqueville, for example, condemned the brutality of many non-French colonial regimes, while supporting his own nation’s conquest of Algeria. Small European populations attempting to rule peoples they considered radically different from themselves were conscious of their need for local legitimacy, but they also needed support from audiences at home. “Only by claiming that he was ‘civilizing’ Morocco” could French colonial general Hubert Lyautey, for instance, “sell colonial expansion to a French public skeptical of its value.”Footnote 51

In Britain, and to some extent the other colonial powers, the economic counterpart of “civilization” was the liberalization of trade. The rise of free-trade ideology, and the decline of mercantilism, implied that in countries providing security and commercial freedom, influence could be more easily gained through economic means and informal empire than through conquest and direct administration.Footnote 52 This is what George Canning meant when he said, as England’s foreign secretary in 1824, that Latin America, now independent from Spain, is “free, and if we do not mismanage our affairs sadly she is English.”Footnote 53 New patterns of informal imperialism, for example, in the Ottoman Empire and Siam, were less territorially exclusive, making territory per se less an object of struggle, especially before 1880, when formal empires began to claim larger territories.Footnote 54 Informal imperialism could develop antagonisms, sometimes leading to one power taking more exclusive control, as Britain did in Egypt and France in Morocco, but this did not involve violation of intercolonial boundaries.

The colonial domain was often thought particularly appropriate for new kinds of ambitious, civilized legal order, as in the Caisse de la Dette Publique in Egypt and the Shanghai International Settlement.Footnote 55 The clearest effort to establish a legal territorial order was at the Berlin Conference of 1884–85.Footnote 56 Lawyers, such as Émile de Laveleye, who were prominent in the effort to codify international law, worried that Europeans would bring to the Congo “their frontiers, their forts, their cannons, their soldiers, their rivalries and perhaps, one day, their hostilities.”Footnote 57 This situation already lamentably existed in Europe, but “must we reproduce this deplorable situation in the middle of Africa, and give the Negroes, whom we claim to civilize, the sad picture of our antagonisms and our quarrels?” The Berlin General Act, written under the influence of such lawyers, responded by committing signatories to the neutrality of territorial waters in the Congo Basin in the event of European war, and providing an option for powers to keep territories in much of Africa neutral. This was meant, as the General Act stated, “to give a new guarantee of security to trade and industry, and to encourage, by the maintenance of peace, the development of civilization.”Footnote 58

The extent of legal force possessed by that neutralization is best demonstrated by the effort of colonial officials and settlers, including Germans, Belgians, British, and Afrikaners, to stop World War II from spreading to Africa.Footnote 59 In 1914, “in conformity with the general principles of the Berlin Act of 1885, the two main ports” of German East Africa “had no coast defences.”Footnote 60 The governor “hated the idea of war and of the disruption of his work for the development of the Colony.” Belgium, while being invaded by Germany in Europe, ordered its colonial forces not to attack the surrounding German colonies, in an attempt to carry out the neutrality provision.Footnote 61 Similarly, the East African Standard, British Kenya’s only daily newspaper, responded to the news of war by calling for African neutrality, arguing that “whatever the national sentiments may be, the settlers of British East Africa and German East Africa must, during the crisis, continue to carry the white man’s burden.” For tiny European populations, war could incite colonial rebellion, and after both German and British East Africa had seen uprisings in 1905 they were conscious of their mutual interest in maintaining a racialized order. Colonial African neutrality failed, primarily because of opposition from London. But it demonstrates the extent of, and reasoning behind, not only the legal force of the Berlin Act, but more fundamentally a racist solidarity among European colonial officials and settlers, oriented toward a common civilizing mission.

If Europeans placed such a high value on “civilization,” however, why was the absence of conquest it produced limited to the colonized world? The most important single reason was that, within Europe, “civilization” turned out to mean “the achievement of nationhood.”Footnote 62 Nationalism provided not only a vision of progress for each nation but also, in some versions, a “brotherhood of nations” that could cooperate in their collective self-determination.Footnote 63 But where political boundaries did not coincide with national populations, this conflicted with the post-Napoleonic peace imposed by the Concert of Europe, and provided a powerful way to justify changing boundaries through war if necessary. For example, every time a new territory was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy, by force or otherwise, a plebiscite was held and considered essential to Italy’s title to the territory.Footnote 64 The nation-state was not the only motivation for war, but it did contribute to virtually every war in Europe.Footnote 65

Europeans did not claim that this correspondence of national and political boundaries should extend to their colonial domains, let alone raise the possibility that most non-Europeans could form nation-states. They did develop emotional attachments to some of their colonies, but these attachments differed because colonies could never be a full part of the nation. Even the incorporation of Algeria into metropolitan France was a legal fiction and did not succeed in assimilating large numbers of Algerians into French society.Footnote 66 Settler colonists were liable to be depicted as having become uncivilized through their exposure to non-European cultures. British General Herbert Kitchener dismissed Boers, for example, as “uncivilized Afrikander savages with a thin white veneer.”Footnote 67 One of the main justifications for war in Europe, then, did not apply outside Europe because of the perception that the rest of the world was in general composed not of nations but of semi-civilized and uncivilized peoples.

Finally, no European states with colonial rivalries fought wars during the nineteenth century, even for reasons unrelated to their colonial rivalries. This is a crucial permissive factor, and without it, it is unlikely that there would have been a complete absence of intercolonial conquest. But it is not sufficient on its own to explain why colonial rivalries did not trigger any wars between Europeans, as I will explain in a separate section.

One illustration of the fact that intercolonial cooperation was based on mutual recognition of “civilized” status can be seen in the exclusion of the Ottoman Empire. Despite being an imperial power with its capital city on the European continent, it was not considered a participant in European civilization, largely because of its Muslim identity.Footnote 68 It was widely recognized as crucial to the European balance of power, having played a key role in the Napoleonic Wars, and with the great powers formally committing to the “territorial integrity” of the Ottoman Empire in 1856.Footnote 69 Yet Ottoman possessions in Africa and Europe were repeatedly taken by force by Europeans over the course of the nineteenth century. Those who were most in favor of preserving Ottoman territorial integrity recognized that this could happen only if the Ottoman Empire “civilized” itself along European lines.Footnote 70 As it became clear it would never satisfy Europeans with reforms, proponents of the European balance of power, such as Otto von Bismarck, favored dividing it up rather than forming balancing coalitions with it as in the Crimean War.Footnote 71 Liberal outrage at Ottoman atrocities against Christians made it difficult for Britain to intervene when Russian forces invaded in 1877, nearing Istanbul.Footnote 72 The revival of the European Congress system in 1878 in Berlin then showed clearly the lack of recognition of Ottoman status, with the aftermath of the war largely being negotiated without Ottoman participation.Footnote 73

“Territorial integrity,” then, in the nineteenth century, was not a right held in virtue of sovereign status but typically a policy of instrumentalizing “semi-civilized” polities toward preserving the balance of power, without recognizing them as active participants in it, and it was also applied to China in the Open Door Policy.Footnote 74 Through the 1932 Stimson Doctrine of non-recognition of conquered territory—originally intended as an attempt to enforce the Open Door Policy—and the League of Nations Covenant, it was the US, not Europe, that was largely responsible for the emergence of today’s universal principle of territorial integrity.Footnote 75

Territorial Inviolability in Practice: Two Near-Misses

How can it be demonstrated that this is the right explanation? Because there are no clear examples of inter-imperial conquest, the best way to demonstrate it is to examine the most important near misses, where war was a significant possibility, and the legal-normative framework was at its weakest. So I examine the confrontations between Britain and Russia over Afghanistan in 1885, and between Britain and France in the Upper Nile in 1898. (In an appendix, I consider a third case, between Britain and France in West Africa in the 1890s.Footnote 76 )

In each case, I ask three questions to determine whether the process of dispute resolution is better characterized as one of pure coercion or one of respect for basic rules of “civilized” diplomacy, including territorial inviolability. First, did claims and counterclaims over territory suggest acknowledgement of a right of conquest, or recognition of existing agreements? If conquest was an accepted method of acquiring territory, there would be little reason to disguise conquest as respect for existing agreements. We might even see the subjugation of enemy forces firmly asserted as evidence of legal title—as Britain did in taking the Sudan from Mahdist forces based on the right of conquest—rather than hidden or explained away.Footnote 77

Second, were explicitly cooperative or technical practices used in determining boundaries? Or did they instead follow lines of occupation established through a competitive process? Territories could be exchanged, in the latter case, but coincidences of interest would provide a better explanation for which territories were exchanged, and when, than arguments based on legal rights or technical expertise.

Third, was the violation of boundaries strongly linked to war? In the absence of a right of territorial inviolability, maintaining ambiguous frontiers without precise definition could be a viable strategy for avoiding conflict, particularly in remote locations where geographical knowledge is limited and detecting boundary violations is difficult. So there might be powerful resistance to officially defining a boundary beyond which war would be inevitable. On all three counts, in both cases, the colonial powers demonstrated faith in the basic rule of territorial inviolability rather than conquest.

Case 1: Britain and Russia over Panjdeh (Afghanistan)

Conflicting claims and actions confirm agreement on the principle of territorial inviolability

In the late 1800s, Russia’s expansion into Central Asia began to approach British India.Footnote 78 The point of the highest likelihood of this causing a direct war was in 1885, when Russia attacked and defeated an Afghan force at Pul-i-Khishti, near Panjdeh. While Afghanistan was not formally part of the British Empire, Afghanistan’s foreign relations were controlled by Britain, and Britain had committed to the defense of Afghanistan against foreign invasion. In 1873 Russia had agreed not to interfere in Afghanistan, but only a very vague definition of Afghan territory was agreed on.Footnote 79 Russia, then, claimed that its 1885 action at Panjdeh did not violate Afghan territory. Most likely the incursion at Panjdeh was an unauthorized action initiated by local Russian officers. There are many reports that the Russian military had been ordered not to advance any further in Central Asia. This would also resemble several earlier similar incidents of officers advancing without approval.Footnote 80 Russia did not seriously intend to take territory from Britain in Central Asia, and it was not territory but prestige that was primarily at stake.Footnote 81

If, as seems likely, the Panjdeh incursion was not state directed, this would be sufficient evidence that no breach of territorial inviolability took place, and would be consistent with the notion that Russia had every intention of respecting the British protectorate in Afghanistan.

Evidence of faith in shared, impartial dispute-resolution practices

In the year before the Panjdeh incident, a Russo–Afghan boundary commission had already begun working.Footnote 82 Perhaps the most telling evidence that both sides retained faith in a bilateral solution is that the commission continued despite the two powers’ approaching the brink of war. Although British primary accounts of the boundary commission acknowledge the difficulties of compromise, they also stress the cordiality of relations between Russian and British agents on the ground.Footnote 83

The proceedings of the commission reveal an underlying assumption that territory should not change hands, including through any right of conquest, and that prior rights should merely be clarified unless the two powers agreed otherwise. According to the lead commissioner, the correspondence leading to the 1873 agreement showed that the overall intention of both governments was merely to define more clearly the already existing territorial rights, and the same intention was the basis of the agreement of 1885.Footnote 84 Russia could have insisted on existing military lines of occupation as a starting point for negotiations, or tried to use Panjdeh as a bargaining chip, based on a right of conquest, or effective occupation, to achieve other aims. Instead, Russia bargained away another portion of territory, which was not previously disputed, to keep Panjdeh.Footnote 85

Resolution of the dispute relied significantly on technical geographical and surveying practices. An agreement that both sides would conduct surveys resolved one of the most difficult deadlocks in the negotiations.Footnote 86 While it was mainly Russian initiative that had generated the delimitation, Britain had responded enthusiastically, sending a party of two or three thousand, including military escort and supply.Footnote 87 In May 1885 the Russian boundary commissioner attended a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society in London, where the initial report on the commission was read. For Alexander Morrison, this is a good illustration of “the relatively free exchange of information between Russian and British scholar-administrators, and the shared intellectual assumptions and culture which lay behind it.”Footnote 88

Violation of boundaries strongly linked to war

British Prime Minister William Gladstone had considered Russia’s promise not to interfere in Afghanistan a “very solemn covenant,” and saw the clash at Panjdeh in starkly moralistic terms: “The Afghans suffered in life, in spirit, and in repute... A blow was struck at the credit and the authority of a Sovereign—our ally—our protected ally—who had committed no offence.”Footnote 89 Gladstone promised to “have right done in the matter,” and brought Britain to the brink of war with Russia.

In British public debates it was not immediately taken for granted that the notion of drawing a clear boundary which could identify a violation of territory—a notion presupposed by territorial inviolability—made sense in a remote, mountainous area such as Central Asia. Some maintained that a mere “paper frontier,” marked by pillars in the sand, could never hold back the Russian advance. But the chief commissioner for the boundary delimitation argued that having a clear boundary was important because it would allow greater state control over war and peace: rather than “the peace of the world” being “at the mercy of any ambitious frontier officer,” now “Russia will not violate the frontier until she is willing and ready to enter into war.”Footnote 90 Moreover, having a defined frontier would allow both empires to pursue their common civilizing mission in harmony. Even the die-hard imperialist Lord Curzon, who was critical of this “artificial” frontier, had to admit in 1889 that the boundary had so far been effective, and that if Russia violated the boundary it would at least clarify to the world that Russia was the aggressor.Footnote 91

For Russia, the events of the 1880s reinforced the principle of confining the legitimate operation of military force to one side of a boundary.Footnote 92 The Russian advance through Central Asia had been famously plagued by the problem of local officers acting independently (a problem seen also on the British side). For example, the foreign minister was informed of the decision to annex Kokand in 1876 only after it was taken.Footnote 93 The Russian War Ministry keenly opposed the boundary delimitation and obstructed it as much as possible because it would limit the independence of the military. The completion of the boundary, then, marked the “end of the long period of military dominance over the empire’s Central Asian policies” and the establishment of diplomatic control over boundaries.Footnote 94 It signified the end of the continuous expansion that Russian Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov had, in 1864, famously attributed to the lack of a boundary with a “civilized” neighbor.Footnote 95

Case 2: Britain and France over Fashoda (Sudan)

Conflicting claims and actions confirm agreement on the principle of territorial inviolability

The closest Britain and France came to war over colonies was in 1898, when both claimed title to Fashoda, on the Nile in the Bar el-Ghazal region of Sudan. Britain claimed that region based on a right of conquest from the “Mahdist” Sudanese state that had briefly controlled it. France, meanwhile, launched an expedition, the Marchand mission, which reached Fashoda before Anglo–Egyptian forces did, and claimed the territory based on effective occupation. In this case, boundaries were particularly unclear even by contemporary standards, with no prior Anglo–French agreements to refer to. In 1895, British Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Sir Edward Grey had stated that any French expedition in the Nile Valley would be “an unfriendly act,” but refused to give “a special definition of territory.”Footnote 96 France had duly made it known that it contested these claims.

But despite the absence of agreements or boundaries that could be violated, each side attempted to prove, in an extensive, public legal debate and using many different parallel lines of legal argument, that it had not violated the other’s territory, suggesting a keen interest on both sides in avoiding any breach of international law. Britain, for example, argued for possession based on right of conquest arising from the defeat of the Mahdists, but Lord Salisbury also arranged for Egypt to issue a statement that its claims in Sudan had never been abandoned during the war with the Mahdists.Footnote 97 France, meanwhile, argued both that the Marchand mission constituted effective occupation at the time of the crisis and that the territory had long been French.Footnote 98 And even though France rejected Grey’s 1895 statement, it tried to show compliance with it anyway, by insisting that the Marchand mission was part of a larger mission which had begun before 1895.Footnote 99

Because, unlike in the Afghanistan case, there were no territorial agreements to refer to, it is not possible to ask whether existing boundaries were respected. But the legal debate surrounding the incident, as well as the nature of the Marchand mission, confirm that both sides placed a high importance on maintaining the legality of their claims, and each considered taking territory from the other to be illegitimate.

Evidence of faith in shared, impartial dispute-resolution practices

The Marchand mission presupposed a faith in international law: it was a small contingent not intended to be able to resist Anglo–Egyptian forces but only to mark an official presence.Footnote 100 Officially, France claimed that the mission gave them effective occupation, and therefore territorial rights, but clearly the occupation was effective only in a legal sense, not literally. Marchand believed that in response Britain would convene a European conference to settle the more general issue of control over Egypt, during which it would allow the French to stay at Fashoda.Footnote 101 A major narrative in the French press, across the very polarized political spectrum, was that France was reasonable and lawful, while Britain depended only on its superior military power: “strength was on Britain’s side, but honour was on France’s.”Footnote 102 Marchand was held up during the divisive Dreyfus Affair as a martyr-hero who could unite France in admiration of his persistence against militarily superior but morally inferior Britain.Footnote 103 French writers contrasted Marchand the “pacific conqueror” with Kitchener’s slaughter of the Mahdists. So the stakes of the moral and legal arguments were high for France.

Because of the popularity of a hard-line stance in Britain, combined with Britain’s overwhelming military superiority locally and in general, the government refused to engage in negotiations until the Marchand mission withdrew. But both governments sought a compromise, and most likely would have found one if not for public opinion in both countries. Privately, Salisbury tried to be conciliatory, noting in an unofficial memo that French help would be needed to clarify the geographical problem.Footnote 104 He also suggested a boundary that would give some concessions to the French, including some areas in the Nile Basin which had previously been subject to Egyptian rule.Footnote 105 France, meanwhile, focused on trying for a negotiated solution, repeatedly signaling conciliation and willingness to make concessions.Footnote 106

Unlike in Afghanistan, cooperative boundary-drawing practices failed to begin until after the crisis was over; instead, it was resolved by France’s simply withdrawing the Marchand mission. And there was sufficient appetite for war both in government and from the wider public.Footnote 107 But there are other forms of evidence of interaction during the crisis that show that adherence to a civilized international order was important to those involved. Accounts of the events record a politeness and cordiality between British and French agents that appear to perform a shared civilization. Herbert Kitchener, leading Anglo–Egyptian forces, found Marchand and his men to be “the pink of politeness.”Footnote 108 Marchand did not object to raising an Egyptian flag at the southern end of Fashoda. After discussing their positions, Kitchener suggested they both take a whiskey and soda. These polite interactions meant that Kitchener did not treat Marchand, as Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé had feared, as a “pirate.”Footnote 109 Delcassé, similarly, signaled his good intentions when requesting a report from Marchand instead of recalling the mission, by making this request “in the clear,” and Salisbury agreed to allow this delay.Footnote 110 When Marchand withdrew, he did so without setting foot on British territory.Footnote 111 These cordialities on the ground kept the peace, making it possible for the boundary to be negotiated in Europe rather than fought over on the ground.

Violation of boundaries strongly linked to war

Britain was certainly ready to go to war over the French violation of supposedly Anglo–Egyptian territory. France had to leave Fashoda before any negotiations could take place, Salisbury insisted. Among British media voices pushing for war it was a pervasive theme that France was an “intruder.” The Evening News, for example, wrote: “If a householder finds a man in his back garden, he does not go to arbitration about the matter... He simply orders the trespasser out, and, if he will not go out of his own accord, he has to go in another fashion.”Footnote 112

At the same time, unlike in Afghanistan, in the case of Fashoda there was not even a vaguely agreed boundary that could have been violated, only recent, unilateral claims on both sides, so the question does not apply directly. So while France’s unwillingness to go to war was clearly the result of being unprepared to face Britain, this is not evidence that France was willing to overlook the norm of territorial inviolability. While many viewed Fashoda as belonging to France by right, the legal case was less than watertight. Not long before the crisis, “the opinion even of the most eminent French jurists, men like Despagnet and Bonfils, was that the Egyptian claims stood, and that the Sudan was neither res nullius nor res derelicta.”Footnote 113 Where there was outrage in the French press it was often about the British lack of compensation for Fashoda.Footnote 114 So while the British violation of supposedly French territory was not something France could go to war over, it was still considered grossly unjust.

Alternative Explanation: “The Long Peace”

It might seem that the absence of inter-imperial conquest is more simply explained by subsuming it within a larger “long peace” among European states between 1815 and 1914, during which there were no wars involving all the great powers, and no wars between European states having active colonial rivalries. This peace, then, may have been more a result of intra-European than of colonial dynamics.

As acknowledged earlier, the absence of war between states with colonial rivalries provides an important permissive condition. But it cannot explain the clear divergence between this complete absence of intercolonial conquest between 1815 and 1914, on the one hand, and the presence of war and conquest elsewhere in time and space on the other. To begin with, the European nineteenth century was not very peaceful, as we saw in Tables 1 and 2. Colonial powers fought each other in three wars: France versus Spain in 1822–1823; France versus the Netherlands in 1830–1833; and the Crimean War in 1853–1856. If there was a “long peace,” it certainly ended before major colonial rivalries resurfaced; between 1850 and 1875 alone there were four great-power wars in Europe.Footnote 115 By contrast, there is not one clear example of European intercolonial conquest. The idea of a “long peace” on its own cannot explain that stark divergence.

Perhaps what is important, then, is not so much a coherent, sustained European peace as much as that for some reason, or even by coincidence, European states happened never to have gone to war at the particular times they had active colonial rivalries, despite war elsewhere in Europe. Somehow, Russia and Britain were only at war (in 1853–1856) before they were within reach of each other in Central Asia, and France and Prussia only went to war (in 1870–1871) before Germans revived their overseas colonial ambitions. But then, what explains the difference between Europeans’ success in subordinating colonial rivalries to the European peace, and their failure to subordinate a host of other war motivations, from national liberation and unification to France’s attempt to recover its national honor by attacking Prussia in 1870?Footnote 116

One possible answer might be that Europeans prioritized their homelands over far-away colonial questions. But this is not self-evident because they clearly did not always prioritize issues in this way before 1815. Colonial competition was central, not peripheral, to the eighteenth-century Anglo–French rivalry, and this was reflected in the mercantilist ideas of the time.Footnote 117 As Paul Schroeder notes, “the 18th century was filled with wars in North America, the West Indies, India, and on the high seas, which spilled over into Europe, and vice versa.”Footnote 118 So even if the absence of war between colonial rivals had been mainly a product of European rather than colonial considerations, this would not explain why colonial issues stopped being one of the important issues contributing to war after 1815.

Perhaps all this colonial war occurred before 1815 not because colonial issues were pressing but because the containment of war depended on a system of great-power management of international order which did not yet exist? But the argument of this essay is also based on a system of great-power management emerging in 1815. So this would be clearly an alternative explanation only if it can be shown that this system of great-power management did not depend on the way European societies defined themselves in terms of a common “civilization,” in opposition to “barbaric” societies that needed to be colonized. It would be especially difficult to sustain such an argument in the latter half of the century, when the major issues being managed by the great powers related to affairs in Africa and Asia.

One way in which this can be demonstrated is by asking why some powers were included in European intercolonial cooperation, and some (particularly the Ottoman Empire) were not. Such an explanation is difficult to produce without understanding the double standard that divided appropriate relations between Europeans, based on law and mutual recognition, from relations with non-Europeans, based on domination. By the end of the nineteenth century, most European powers, acting within this double standard, viewed Ottoman territory as fair game for conquest, despite their 1856 commitment to maintain its territorial integrity.Footnote 119 Italy, for example, conquered Tripolitania in 1911. This was because the Ottoman Empire was not a full participant in the European order. Why was it not? “Objective” measures of power cannot explain this, as colonies of small European powers such as Belgium were fully respected. Nor can separateness from the European balance of power, given that the expansion of Russian power in the Balkan territories threatened Austria.Footnote 120 Rather, the Ottoman Empire was not a full participant in the European order because, as we have seen, it was not identified as a “civilized” power.Footnote 121

Conclusion: Further Shifts in the Meaning of Territorial Integrity

This essay has shown that restrictions on conquest have a deep history, going back at least to the Concert of Europe. This matters in the context of claims that because of Russian conquests in Ukraine, and the possibility that they may become widely recognized through a peace-for-territory deal, an Old World Order of “might makes right” threatens to return.Footnote 122 The twentieth-century universal and absolute rule against annexation by conquest did not replace a nineteenth-century “law of the jungle.” It replaced a different kind of order, which was reflected in a different set of values and principles. Thus it seems unlikely that all restraints on conquest are at risk of disappearing entirely.

One response to this argument might be that the Old World Order simply existed in the eighteenth century, or earlier, not the nineteenth. There is some merit to this: territories in both Europe and the colonies frequently changed hands by force then. But the problem is not just the particular century identified. “Might makes right,” while a useful heuristic in some ways, is likely to be an incomplete description of any real political system.

In eighteenth-century Europe, for example, the institution of dynastic monarchy was a moral and legal principle that functioned as a script for international politics. Frederick the Great’s 1740 conquest of Silesia, based on a bogus succession claim, might seem to show that monarchy was a thin disguise laid over a purely anarchical system. But Frederick was merely bending the rules.Footnote 123 The French Revolution and Napoleon, by contrast, flipped the board over, upending the accepted rules, and by demonstrating the power of the democratic levée en masse, revealed how much of a limiting force the legitimacy of monarchy had always been.Footnote 124 And the further back in European history we go, the more relevant the Just War tradition becomes, in which war was illegitimate when it was simply a means of conquest.Footnote 125

This basic insight, that the absence of rules and institutions never comes in pure form, is not unrecognized. Hathaway and Shapiro, for example, note that Hugo Grotius, who systematized the legal institutions of early modern Europe, accepted the Just War tradition, and believed that outside of “formal” interstate wars it was possible to distinguish just from unjust belligerents.Footnote 126 From this perspective, the question scholars should ask is not whether the principle of territorial integrity will give way to “might makes right,”Footnote 127 but how recent events might alter understandings of how war and conquest can be limited.

But while such a perspective on the history of law and morality is not unknown in theory, it is rarely applied in discussions of the present and future of conquest. Instead, it is typically assumed that a prohibition of conquest could only be meaningful in its post-1945 form: an absolute prohibition of annexation by conquest. Hathaway and Shapiro, for example, are explicit that “there are a limited set of legal systems to choose from”: war and conquest are either legal or illegal, and any third possibility can only be a worst-of-both-worlds mixture of the two.Footnote 128 The Old World Order which we risk “reverting to,” they believe, was the “polar opposite” of the New World Order.

What would it mean, then, to acknowledge that the binary vision of an absolute rule of territorial integrity versus “might makes right” may not be adequate to the emerging world order? One possibility, with some proponents among Chinese scholars, is that territorial integrity could become one important principle among others.Footnote 129 Such a view remains marginal in international law: while self-determination is often considered a competing principle, it has successfully helped annexation-by-conquest become widely legitimate only in a few cases where colonial enclaves were conquered by newly independent states—and even in these cases, the legitimacy achieved was largely extralegal.Footnote 130 What makes Russia’s actions in Ukraine different from anti-colonial conquests, such as India’s 1961 taking of Goa from Portugal, is their greater potential to act as a precedent for future conquests. Although there are still remnants of overseas colonialism, such as Greenland, they were reduced to limited and fairly clearly delimited parts of the world soon after 1961. Self-determination more generally, which is one part of a large and nebulous body of justifications used by Russia in Ukraine, is much easier to see as useful to would-be conquerors in the future.

Yet even if such a view of territorial integrity as relative were to become more mainstream—and a peace-for-territory deal in Ukraine would not automatically lead to that—this would not mean that all limits to legitimate conquest would suddenly be removed. The legitimacy of conquest would continue to be limited not only by the distribution of military capabilities but also by the extent of those other principles. A Russian invasion on the basis of self-determination, under this rubric, would be hard to justify in Mongolia, where there are few Russians. China, likewise, may be able to instrumentalize the relativization of territorial integrity to justify a conquest of Taiwan on the basis of enforcing state sovereignty, but it would be harder for it to make such claims against territory that is part of a widely recognized sovereign state, which Taiwan is not.

This speaks to concerns raised by Brunk and Hakimi that the Russian position has no “limiting principle” which could prevent it from being used as a precedent for the use of force wherever “people continue to harbor historical grievances about the internationally recognized borders that they have inherited.”Footnote 131 For these authors, Russia’s conquests in Ukraine mark a decisive break in history because while Western countries may have often violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter in the past, they always provided such a limiting principle. But Brunk and Hakimi do not seriously engage with Russia’s arguments, particularly those of Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, which are more specifically intended for an international audience than those of Vladimir Putin.Footnote 132 These arguments refer to widely held ideals such as self-determination, which cannot justify just any conquest that is militarily feasible, nor do they imply that all national irredentist conquests are justified. Russia’s justifications are deeply flawed—and Brunk and Hakimi do not claim that this is what makes Russia’s actions unprecedented—but ignoring its arguments and dismissing their potential to persuade risks underestimating Russia’s influence outside the West. No doubt there are reasons to worry about the precedent that a Ukraine peace deal might set, but it is not the case that it would involve no limiting principles at all. It would strain credulity, for example, to imagine the US using the Ukraine precedent to justify conquering Greenland.Footnote 133

This relativization of territorial integrity is reflected in the responses of many Global South states to the Russo–Ukrainian War. They show, on the whole, not a desire to critique or dismantle the principle of territorial integrity but a struggle to find meaningful positions that will uphold both territorial integrity and some competing principles.Footnote 134 Some have emphasized their status as “bystanders” or subject to “collateral damage” from anti-Russian sanctions, suggesting that a right of neutrality should protect them from being forced to take sides.Footnote 135 Some also argue that NATO expansion is to blame for the war, suggesting that the principle of legitimate self-defense remains important.Footnote 136 Regardless of the particular reasoning, the principle of territorial integrity is not an object of direct critique. Almost all states, including Russia and Iran, continue routinely to voice support for it as long as it is properly contextualized among states’ other rights and responsibilities.Footnote 137

Brunk and Hakimi, of course, recognize that states that have “stayed on the sidelines” of the conflict are not in “full retreat” from the prohibition. But still they refrain from characterizing the positions of those states as being guided by any general principles, instead seeing territorial integrity here as a casualty in a broader contest largely about the global dominance of the US and NATO. It may be that these states fail to support territorial integrity in the absolute way that it has mostly been upheld since 1945, but it is misleading to suggest that their actions and rhetoric do not “reflect a concerted effort to uphold it” in any way.Footnote 138 Their continuing to struggle to maintain territorial integrity along with competing principles may be the best possible outcome for territorial integrity in this context.

The only major state which is presently notable for its failure to refer to territorial integrity as a general principle is the US under Donald Trump. For Trump, “territorial integrity” is first and foremost the right of the US to be protected against terrorists and immigrants, rather than a prohibition of state conquest in general.Footnote 139 But what is important here is that Trump’s rhetorical abandonment of the territorial integrity principle has not yet been matched by a global shift. Most states continue to see value in territorial integrity as a general principle, even if they are reconsidering its rank in their list of priorities.

The central implication of this essay for the fate of territorial integrity today, then, is that it depends on what we mean by territorial integrity. If the phrase refers to the absolute and universal prohibition of interstate annexation by conquest, then there are indeed reasons for suspecting a certain erosion of it. Such a suspicion would be most clearly vindicated if conquered territory in Ukraine becomes widely recognized as Russian. But supporters of the post-1945 order should not confuse that order with all order in general. If “territorial integrity” encompasses constraints on conquest more broadly, then it is certainly more durable than is sometimes feared. If a great-power war—whether or not it is initially over territory—were to break out, of course, territorial integrity would be of little help. But it should not be forgotten that in the past conquest has been meaningfully limited without an absolute prohibition. Acknowledging that territorial integrity still has value when relativized among other important goods—including but not limited to peace—may someday be the best way to save it.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325101124>.

Acknowledgments

I thank Tanisha Fazal, Alvina Hoffmann, Joseph O’Mahoney, the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Reading, and the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and productive criticisms. I would also like to thank my father, Paul Goettlich, for suggesting the title, “Etiquette of Thieves.”