In recent decades, deliberative practices have increasingly been used around the world by local, regional, and national institutions (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2018; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Reference Gherghina, Soare and Jacquet2020; Michels Reference Michels2011). In Romania, most examples of deliberative practices revolve around local-level practices, including participatory budgeting and citizen councils, and focus on how they function and influence the communities (Gherghina and Tap Reference Gherghina and Tap2021; Schiffbeck Reference Schiffbeck2019).

The use of deliberation at the local level in Romania is very limited and consists mainly of participatory budgeting. In the cities which use participatory budgeting, the main organizers were the mayor’s office along with the local councils. Only one deliberative attempt has occurred at the national level—a forum seeking to make constitutional reforms but its functioning was problematic and produced no concrete results due to a lack of support from political parties (Gherghina and Miscoiu Reference Gherghina and Miscoiu2016). The first citizens’ assembly in Romania was organized between February and April 2024 in Ramnicu Valcea, a city of roughly 100,000 inhabitants, on the topic of local transportation. A citizens’ assembly is a broadly representative group of members of the public who are selected by lottery to discuss and make recommendations on specific policy questions. The Ramnicu Valcea assembly followed all the recognized phases of a mini-public (Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018): the selection of citizens, regular meetings between the selected participants, and the proposal of solutions. However, similarly to what happened with the deliberative practice at the national level, the political parties did not engage with this local citizens’ assembly. Their behavior is somewhat counter-intuitive in a country characterized by politicization (Stan and Vancea Reference Stan and Vancea2024), as the involvement could have brought the parties electoral benefits such as higher visibility and support in the local elections in June 2024.

This article explores this situation and aims to explain why political parties did not engage in this citizens’ assembly. Beyond this empirical puzzle, the article also addresses a gap in the literature. Extensive research has focused on identifying several interaction scenarios between political parties and deliberative practices in the form of initiation, co-optation, or cooperation with civil society organizations (Borge and Santamarina Reference Borge and Santamarina2016; Gherghina Reference Gherghina2024; Junius et al. Reference Junius, Caluwaerts, Matthieu and Erzeel2021). However, limited attention has been paid so far to the reasons why political parties ignore the deliberative practices that are organized in their proximity. The analysis uses inductive thematic analysis to identify the reasons why the parties did not engage with the citizens’ assembly in this instance. It draws on eight semistructured interviews with local politicians holding decision-making power in the four political parties that were represented in Ramnicu Valcea’s local council at the time of the assembly: National Liberal Party (PNL), Romanian Ecologist Party (PER), Save Romania Union (USR), and the Social Democratic Party (PSD). The interviews were conducted in August and September 2024.

The next section briefly describes the party system in Romania and the prominent political parties at the local level in Ramnicu Valcea and at the national level and gives an overview of the citizens’ assembly. The third section includes the analysis of the semistructured interviews conducted with the local politicians. The conclusions wrap up the discussion and suggest some avenues for further research.

Political Parties and the Citizens’ Assembly: An Overview

The multiparty system in postcommunist Romania has witnessed many entries and exits on the political scene as a result of mergers or absorptions. After the 2020 legislative elections, five parties passed the electoral threshold to gain parliamentary seats: the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR), PNL, PSD, and USR. The AUR is a radical-right party that emerged in 2019. The UDMR is an ethnic party representing the Hungarian minority that has joined many coalition governments. The PNL is a liberal party with its roots in the nineteenth century, which was banned during communism but reestablished in 1990 after the regime change. The PSD is a successor communist party that is the largest political party in the country after winning all but one popular vote at the national level. Since 2021, PSD and PNL have governed together using a rotation system in which they take turns in appointing the prime minister for half a term in office. The USR is a pro-European political party with an anticorruption agenda.

In Ramnicu Valcea, three of these parties gained representation after the local elections in September 2020, two months before the national legislative elections: PNL, PSD, and USR. These were joined by PER, which is a green party with limited appeal at the national level, which has had no presence in parliament for more than two decades. The mayor, who is elected directly by citizens, belonged to this party but changed his political affiliation to PSD before the June 2024 elections.

The citizens’ assembly organized in Ramnicu Valcea in 2024 included 20 citizens who had been selected in a three-step process: (1) sending out letters to 2,000 citizens residents of the city, (2) the citizens who received the letters had to respond expressing their willingness to be involved in the assembly, and (3) the selection of the citizens that should participate. The entire process took almost a year, culminating in an open letter addressed to the mayor of the city which included several recommendations. Apart from the selected citizens that took part in the assembly, a couple of local and international institutions were involved through representatives, such as councilor of the mayor, an expert from DG Regio, two experts from the OECD, the head of service from the General Secretariat of the Government of Romania, and the project implementation team (Iliescu Reference Iliescu2024).

Analysis

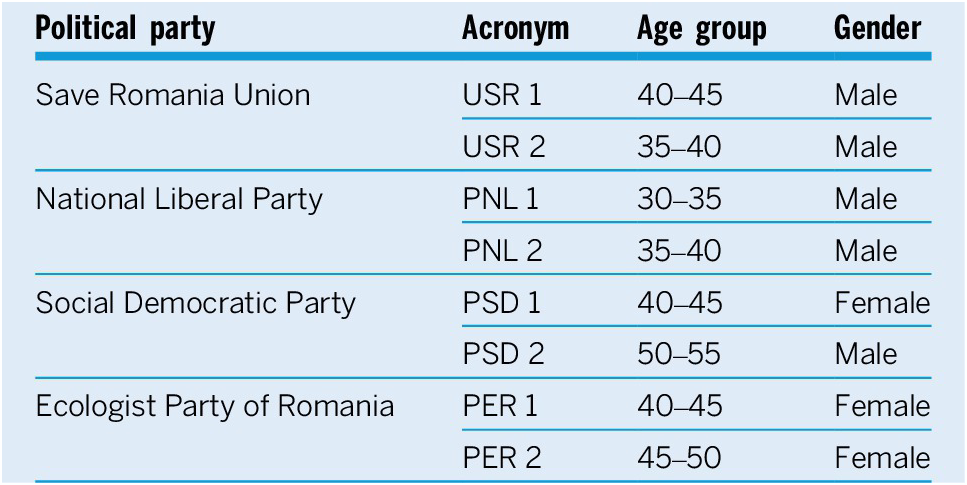

To identify the reasons why the political parties that were part of the local council between 2020 and 2024 did not get actively involved in the process, I conducted eight semistructured interviews with politicians with decision-making power in the parties represented in the local council (table 1), two respondents per party (PER, PNL, PSD, and USR). The interview guide included an open question about why the party was not involved in the citizens’ assembly, accompanied by follow-up questions asking specifically about the degree of information about the assembly, the potential for visibility saliency, and the credibility of the deliberative practice (see Appendix). The questions were inspired by the literature on party strategies for societal engagement and on previous observations about their interactions with deliberative practices (Bolleyer Reference Bolleyer2024; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Reference Gherghina, Soare and Jacquet2020). The respondents were recruited using the contact details that were available on the website of the local council, on the Facebook pages of the local parties, or by calling the local party headquarters. The selection was designed to promote diversity in terms of gender, age, and position in the party. All the interviews were conducted by phone in Romanian and recorded for transcription after receiving explicit consent.

Table 1 Respondents’ Profiles

The politicians argued that most of the issues that were identified at the local level should be solved first by the local institutions (i.e., the mayor and the local council), then by county or national institutions, thereby referring to a bottom-up approach to the transmission of pressing matters that need to be addressed; for example, “The main one would be the local and county public authority, which must get involved, based on long-term strategies, on the basis of projects” (USR1). Even though the politicians talked about several institutions that should be involved in solving the issues that were identified by citizens, they did not explain why their political parties are trying to change things or how they could point out the severity of those issues, making it clear that at least at the local level, the presence of a public body is necessary to manage all the areas in need of improvement.

The opinions regarding the involvement of political parties in the process varied widely from party to party. One of the expressed opinions revolved around the idea that the entire proposal of a citizens’ assembly had been hijacked when it came to the actual implementation of the procedure by leaving out the political party that had originally suggested that the citizens of the city should be consulted on the topic of local transportation:

I initiated that project, I signed it together with the community foundation, I insisted that that the project will be done, including my party as well, I took it to a certain area so to speak, after which reaching the political part and of interest to the mayor we were removed. I wasn’t allowed to take care of that project anymore, but it’s one that I cared about very much because I wanted people to be involved in the decision-making process. (USR1)

In other cases, the arguments for the lack of involvement from other parties revolved around ideas of miscommunication, lack of transparency, and genuine lack of knowledge about the citizens’ assembly. One of the reasons that led to miscommunication and lack of transparency seemed to be the positionality of the political party of which the interviewees were members. More specifically, the respondents said that they might not have been involved in the organization of the assembly because at that time the party was in opposition to the party of which the mayor was a member:

First of all, this meeting was organized by the city hall, which, compared to the party I belong to, is in opposition, or we are in opposition to them. I can bet that most of my colleagues did not even know about this meeting. At least, we were not officially informed of this meeting. They went strictly through administrative channels, those from the mayor’s office, meeting with citizens, but citizens, so to speak, are also our party members and our sympathizers. Much better public communication could have been achieved, but it probably wasn’t wanted. (PNL1)

Based on the information presented by the respondents, even though most of the information was public, knowledge about the process was still lacking, mainly because of the approach adopted by the mayor’s office and the minimal promotion of the process: “I don’t continuously follow social networks, or I haven’t been informed, I don’t know about this citizens’ assembly” (PSD1). Another comment was that

most of the time, when the city hall organized activities in which citizens were involved or present, in order to preserve the possibility of communicating only what they wanted, they avoided involving the opposition, not only the PNL, the party I represent, but also those from USR, who were also half in opposition, half of them with the leadership. So, it’s a custom in Romania, when you’re in power and you have a meeting with the citizens, you want to communicate to them only what preserves your power and what helps you from a media point of view, so to speak, and this meant that you don’t need the opposition there to challenge your arguments or decisions. (PNL2)

The lack of competent personnel that could have taken part in the citizens’ assembly was not a cause of the parties’ nonengagement. The interviewees mentioned that they have several members in their parties that could be involved in a similar process in the future if it is generally decided to organize them: “Certainly, at this moment I don’t know if I’m 100% capable, but I’m preparing to be one of those capable of participating in such gatherings, and I am currently well enough anchored in politics and situations at the local level to participate at such gatherings” (USR 2).

The interviews revealed a consensus regarding the benefits of party involvement in the organization of the citizens’ assembly, which could have generated more visibility outside the periods of electoral campaigns among voters. The same idea also applies regarding the topic of the importance of citizens’ involvement in the decision-making process at the local level. All the interviewees said that citizens should be at the center of political decisions and that their opinions should be taken into account every time: “The involvement of citizens is extremely important. But there is also a very big lack of interest among citizens; maybe they, I don’t know in the past, they tried, they struggled and noticed they had no success. But this does not mean that all people are the same” (PER 1). There was some reluctance when it came to acknowledging the results that the citizens’ assemblies produced because there had been no prior use of deliberative practices in the country, not just at the local level:

From what I’ve seen here, most of the time, unfortunately, it’s more about image than an impact that offers change. They were seen most of the time by local authorities and mayors simply from an electoral point of view to show people that they still want to listen to them, but unfortunately that’s about it. There are many topics on which public consultations can be made; there are many things that can come from citizens, many projects that can be implemented. The problem is that we have to offer them a system, a program, a project, something through which they can do these things, through which they can be consulted frequently, not just once every four years. (USR 1)

Even though the process ended with an open letter addressed to the mayor of the city, the deliberative practices and the inclusion of citizens in the decision-making process were considered important by all the political parties that formed the local council between 2020 and 2024.

Conclusions

The present analysis of the citizens’ assembly in Ramnicu Valcea highlights several causes that can explain the noninvolvement of political parties in the deliberative process. One prominent cause was the poor communication between the assembly organizers and the political parties. Without a clear understanding of precisely how they could contribute, many political actors chose to remain on the sidelines rather than actively participate in discussions that could shape local governance. A second cause was that the political parties did not find a place in the process. The assembly’s bottom-up approach to local governance emphasized grassroots participation and empowering citizens to voice their concerns and preferences directly. Although this is a commendable strategy to foster democratic engagement, the political parties felt marginalized because they considered that their traditional roles of aggregating and expressing citizens’ interests were being undermined. The parties viewed their involvement in the assembly as futile. A third cause was the tendency among the political parties to prioritize their own interests over genuine citizen engagement. In many cases, party agendas and electoral strategies took precedence over the collaborative spirit that the citizens’ assembly promoted. This self-serving approach not only alienated the parties but also diminished the overall effectiveness of the assembly; the parties were not oriented toward collective problem solving, instead focusing more on partisan maneuvering.

The present analysis of the citizens’ assembly in Ramnicu Valcea highlights several causes that can explain the noninvolvement of political parties in the deliberative process.

This case study of Ramnicu Valcea brings relevant contributions to the broader field of study. It underscores the potential benefits of integrating political parties into deliberative processes. By actively involving political entities in these assemblies, an opportunity arises to enhance visibility and legitimacy, which can encourage broader citizen participation. When political parties are seen as stakeholders in the deliberative process, they can help to bridge the gap between citizens and local governance, fostering a more inclusive environment in which diverse voices can be heard and considered. Furthermore, the integration of political parties can lead to more informed decision making, as these entities often possess valuable insights and resources that can enrich discussions. Their participation can also help to ensure that the outcomes of the citizens’ assembly are not only reflective of public sentiment but also feasible and aligned with existing political frameworks. Ultimately, fostering a collaborative relationship between citizens and political parties can enhance the quality of local governance, promote accountability, and strengthen democratic practices within the community.

This article contributes to the literature that focuses on the involvement of political parties in deliberative practices by revealing the challenges that prevent greater engagement. Although previous research has identified several possible reasons why parties could decide to use deliberation (Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2022; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Reference Gherghina, Soare and Jacquet2020), this study illustrates the existence of multiple endogenous and exogenous obstacles

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is based upon work from the COST Action CA22149 Research Network for Interdisciplinary Studies of Transhistorical Deliberative Democracy (CHANGECODE), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Funding

Research for this article was supported by a project funded by the Romanian Executive Agency for Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation Funding (UEFISCDI) with the number PN-IV-P1-PCE-2023-0070.

APPENDIX: INTERVIEW GUIDE

-

1. What do you think about the possibilities that citizens have to get involved in the decision-making process in Romania?

-

2. What do you think are the main problems facing your community?

-

3. Who do you think should be in charge of solving these problems?

-

4. Which of these problems are addressed by your party?

-

a) How does it do this?

-

-

5. In 2024, a citizens’ assembly was organized in which some community issues were discussed. In this context, the citizens’ assembly involved the meeting of various citizens and decision-makers to dialogue, listen to points of view and identify solutions to those problems. Why do you think your party did not get involved in these discussions?

-

a) To what extent did your party have access to this assembly?

-

-

6. To what extent did your party have information about this citizens’ assembly?

-

7. In your opinion, would the party’s involvement in this citizens’ assembly have increased the party’s visibility among voters?

-

8. In the event that the party would like to get involved in similar events in the future, would there be people from the party who would participate in them?

-

a) Is the active human resource a problem for activities of this kind?

-

-

9. How important is the involvement of citizens in decision making at the community level for your party?

-

10. Referring now to the citizens’ assembly, how much confidence can be had in this process?

-

a) What do you think about how such gatherings are completed?

-

b) How does your party relate to citizens’ assemblies in general?

-