Introduction

Governing parties tend to become increasingly unpopular among voters over time. This phenomenon is referred to as the cost of ruling and is considered one of the most well‐established and universal findings in political science (Cuzan, Reference Cuzan2019; Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002). The cost of ruling has attracted considerable scholarly attention because it helps account for government support, voters’ behaviour and election outcomes across political systems (J. Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2017; Thesen et al., Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2019; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017).

This article demonstrates that the cost of ruling has broader implications for democratic politics as it imposes constraints on governing parties’ capacity to pass legislation. We build a theory proposing that the electoral cost of ruling that voters impose on incumbent parties incentivizes individual incumbent legislators to vote against the party line to distance themselves from the deteriorating party brand. This highlights a paradoxical, and arguably dysfunctional, pattern in democratic politics: After voters give a legislator's party a mandate to take office and pass its policies, they gradually withdraw their support for this party, making it increasingly unattractive for the legislator to vote in favour of party policy. The electoral cost of ruling can thus translate into a legislative cost of ruling with adverse implications for party governance.

We test and substantiate several observable implications of our theory using a unique dataset with the voting behaviour of all members of parliament (MPs) elected for the British parliament between 1992 and 2015, coupled with MP‐level election results and monthly opinion poll data on party popularity. Estimating fixed effects models, we obtain high internal validity by controlling for a host of individual‐ and time‐invariant factors while maintaining the high external validity of the data. Finally, we show that our findings are robust to several alternative model specifications.

Our study has three central implications. First, we demonstrate that the cost of ruling phenomenon has important downstream consequences for party governance. Rather than establishing the phenomenon itself and its implications for election outcomes and government formation (the focus in existing research), we establish that it fuels legislators’ inclinations to disrupt party discipline and dissent from the party line in the legislative process following the election.

Second, th ese findings have important democratic consequences. Party dissent and low discipline make it difficult for citizens to know what parties stand for and whom to hold accountable for policies. Dissent can also lead to government inefficiency or, at the extreme, shutdown, meaning that the political system cannot deliver services to citizens (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell, Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Müller and Strøm2000, pp. 584−587). While the cost of ruling has often been considered a boon for democracy because it facilitates continuous change in government (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002), we show that it also complicates the task of governing.

Third, our findings add new insights to the literature on legislative behaviour. Building on existing work on incumbent legislator dissent (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019; Faas, Reference Faas2003; Kam, Reference Kam2009; Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018), we show that the cost of ruling presents incumbent party legislators with opposing pressures from their party to toe the party line and from voters to signal independence from an increasingly unpopular political party. Given that voters punish governing parties across widely different political systems (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Palmer & Whitten, Reference Palmer, Whitten, Dorussen and Taylor2002), we expect that the legislative cost of ruling may help account for some of the general difficulties parties face in governing effectively across otherwise diverse democratic countries.

The cost of ruling: Concept and downstream consequences

The cost of ruling refers to a simple cause‐effect relationship: When a political party takes on government responsibility, it tends to lose support among the electorate (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Palmer & Whitten, Reference Palmer, Whitten, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017). Cost of ruling is thus the electoral cost associated with taking responsibility for government decisions – even on unpopular, unexpected, or divisive issues. Scholars have proposed several explanations for this phenomenon, one being that voters’ negativity bias leads them to put more emphasis on government failures than successes (e.g., J. Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2017; Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002).Footnote 1 Cross‐national studies estimate that this cost, on average, amounts to about 2.25 per cent of the votes (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002) and that it tends to increase linearly the longer a party has been in office (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017). As with most social phenomena, the cost of ruling does not imply a deterministic relationship. Political parties can win votes while in office, but in the long run, on average, they lose support (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Palmer & Whitten, Reference Palmer, Whitten, Dorussen and Taylor2002). This finding has been established and replicated extensively across numerous countries. As Nannestad and Paldam (Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002, p. 19) note, the literature has produced ‘remarkable results, when considering the differences between the countries in size, in election systems, party systems, etc. Clearly, we are dealing with very basic facts’. In short, the cost of ruling phenomenon ‘holds generally across countries and periods of time’ (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017, p. 712; see also Cuzan, Reference Cuzan2019).

While the cost of ruling is well established across highly diverse democratic countries, its broader political implications remain surprisingly unexplored. Below, we integrate the cost of ruling concept into the literature on legislative behaviour and lay out a theory of why and when it induces incumbent party legislator dissent.

The spill‐over effect of cost of ruling: Consequences for legislative behaviour

Legislators’ votes in parliament are shaped by multiple considerations. They vote according to their personal convictions, often rooted in their demographic background, personality traits or ideological dispositions (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Debus and Muller2015; Bøggild et al., Reference Bøggild, Campbell, Nielsen, Pedersen and vanHeerde‐Hudson2021), and they vote according to the party line to maintain or advance their position within the party (Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Faas, Reference Faas2003; Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018; Strøm, Reference Strøm2012). Political parties hold control mechanisms, including campaign finances, candidate selection and the power to assign committee and cabinet positions, to enforce discipline among its members (Bøggild & Pedersen, Reference Bøggild and Pedersen2018; Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Kam, Reference Kam2009; Martin, Reference Martin2014b). Legislators may therefore vote in line with their political party, even when party policy is at odds with their personal convictions (Kam, Reference Kam2009).

Even though party unity is ‘the name of the game’ in most Western democracies, legislator dissent from the party line does occur. This phenomenon has attracted extensive scholarly attention as it can lead to government inefficiency or, in extreme situations, shutdown and dissolution (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell, Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Müller and Strøm2000, pp. 584−587). An extensive literature has analysed why legislators may sometimes need to distance themselves from the party to appeal to voters and secure re‐election, that is, to cultivate a ‘personal vote’ (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Carey, Reference Carey2007; Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995).Footnote 2 This literature has paid much attention to the role of institutions (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Faas, Reference Faas2003). For example, legislator party dissent is typically high in open‐list, multi‐member district systems where candidates compete against other candidates within their own party and when the party has little or no power to (re‐)nominate candidates for election (Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Crisp et al, Reference Crisp, Olivella, Malecki and Sher2013; Heitshusen et al., Reference Heitshusen, Young and Wood2005; Rehmert, Reference Rehmert2020; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2006; Zittel & Nyhuis, Reference Zittel and Nyhuis2019). This research agenda has generated important insights into how and why legislator dissent varies across political systems and the institutions that serve to minimize it.

At the same time, institutions do not provide the full picture. A quick glance at the empirics makes this immediately clear: Legislator party dissent occurs even in countries where institutions generally should discourage it. This is the case for the highly party‐centred, closed‐list Portuguese system (Leston‐Bandeira, Reference Leston‐Bandeira2009) and for single‐member district systems such as Britain or Canada, where candidates only compete for votes against challengers from opposing parties (Malloy, Reference Malloy2003; Norton, Reference Norton1980). In these cases, existing research suggests that failures of party leaders to reward loyalty among backbenchers, intra‐party ideological disagreement and district representation help explain legislative dissent (Benedetto & Hix, Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Malloy, Reference Malloy2003; Kam, Reference Kam2006, Reference Kam2009; Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018).

Contributing to this line of research, this article considers the cost of ruling phenomenon as a potential catalyst of legislator party dissent and develops a theory that links electoral costs of ruling to legislative costs in the form of decreasing party unity in legislative votes. The cost of ruling that a governing party experiences when entering office is a cost to the overall party reputation or image among the electorate; however, we expect that this may also introduce a cost for the individual legislator being associated with this image. Observational and experimental evidence from the literature on voter heuristics supports that constituents often evaluate local representatives according to their perceptions of the representative's party (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019, pp. 111–113 ). In other words, legislators affiliated with the governing party may experience a spill‐over effect as the deteriorating party image rubs off on their personal reputation among constituents (see also Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993).Footnote 3

Individual MPs have very little control over the overall party image, but they do have some control over their personal image or reputation (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987, p. 182). Therefore, the cost of ruling presents incumbent party legislators with an incentive to signal independence from the party image to constituents because this is the electoral component they can influence as individual MPs trying to minimize the electoral cost associated with their party holding office.

From this theoretical spill‐over argument, we derive three expectations about the occurrence of legislator party dissent. The first and most straightforward expectation is that legislators whose party enters office should become more inclined to signal independence from the deteriorating party image by dissenting against the political line of the party. Preliminary evidence that incumbent party legislator dissent can pay off already exists. Kam (Reference Kam2009) found that incumbent MPs who speak out against their party attract more media coverage and receive higher job approval ratings than those who act in lockstep with the party line (see also Carson et al., Reference Carson, Koger, Lebo and Young2010). Experimental work further suggests that such dissent can appeal to voters of the legislator's own party as well as outpartisans and the median voter (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019) and hereby constitute a possible strategy for winning personal votes despite decreasing party support. Consequently, parties in office should lose some of their control over or loyalty from their MPs who become more likely to dissent on bills they disagree with or that hurt constituency interests. As such, increasing dissent within governing parties will likely not be evenly dispersed across bills but concentrated on contentious and unpopular bills that become difficult to pass. From a governance perspective, this implies a somewhat paradoxical relationship: It is when a legislator's party enters office and obtains a position to pass policy that dissent from the party line will be most frequent. We believe this to be the case even though parties in government typically have additional control mechanisms at their disposal to uphold party discipline, including a nomination for cabinet positions etc. (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Martin, Reference Martin2014b; Zittel & Nyhuis, Reference Zittel and Nyhuis2019; but see Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2006).Footnote 4 Ensuring enough votes to obtain re‐election is often considered a more fundamental need for legislators as it is a precondition for obtaining higher‐order needs such as intra‐party career advancements and cabinet positions (Strøm, Reference Strøm2012).

H1: The likelihood of legislators voting against the party line increases when their party is in government.

Although H1 is consistent with our cost of ruling argument, it is not in itself definitive evidence. Indeed, legislators could have other motivations for dissenting more when their party enters government such as ideological positioning among extreme legislators or protests against the party for being asked to compromise more or being overlooked for cabinet positions during the election term (e.g., Benedetto & Hix, Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Kirkland & Slapin, Reference Kirkland and Slapin2018). Below, we derive additional observable implications to test if incumbent party legislators, in part, dissent due to concerns with losing re‐election as voter dissatisfaction with their party grows. Specifically, we move closer to the proposed theoretical mechanism by leveraging variation across legislators (i.e., the safety of their seat in terms of winning re‐election) and over time (i.e., the gradual accumulation of the cost of ruling).

Our cost of ruling argument implies that the relationship expressed in H1 will vary across legislators. Although the need to obtain re‐election is fundamental, it is also typically a lower‐order need. As Heitshusen et al. (Reference Heitshusen, Young and Wood2005, pp. 33–38) note, re‐election is not a goal in itself but a necessary means to realize other, higher‐order goals such as cabinet and committee positions or financial benefits. The goal for legislators is therefore not necessarily to garner as many votes as possible but to garner enough votes to pass the given threshold to obtain re‐election without upsetting the party leadership and, in turn, sacrificing higher‐order goals (Strøm, Reference Strøm2012). This leads us to expect that the effect of a legislator's party being in office on the likelihood of dissent from the party line is heterogeneous across legislators.

Some legislators hold safe seats with a substantial majority of votes over the challenging candidate(s). Such legislators have a significant electoral ‘buffer’, meaning they can endure some of the electoral cost associated with their party being in office without losing re‐election. The increased tendency to dissent as the party enters government should thus be weaker for legislators in safe seats because their electoral majority implies they can ‘afford’ the electoral cost of toeing the incumbent party line to please the party leadership and prioritize higher‐order goals. Conversely, legislators in marginal seats winning only with a small majority over challenging candidates will be more vulnerable to the electoral cost associated with their party being in government, and, in turn, more inclined to dissent as the party enters office.

H2: The tendency for legislators to vote against the party line when their party is in government increases as seat safety decreases.

Moreover, the cost of ruling phenomenon has an important time component and, accordingly, we expect that time is also relevant for understanding legislator dissent. As mentioned, the cost a party incurs while being in office builds up steadily over time in office (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Thesen et al, Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2019). Observational and experimental research demonstrates that MPs pay significant attention to their party's popularity among voters through, for example, opinion polls and become more inclined to change their communication and political stances when their party loses support (Geer, Reference Geer1996; Schumacher & Öhberg, Reference Schumacher and Öhberg2020). Schumacher and Öhberg (Reference Schumacher and Öhberg2020) also provide evidence that MPs who experience decreasing party popularity are less satisfied with their party's performance and more inclined to demand changes to party policy. Similarly, we expect that incumbent party MPs will respond to unfavourable opinion polls with higher levels of dissent against the party line in parliament. Following our cost of ruling argument, we should expect that the need to disassociate from the party image and signal independence to voters would intensify as incumbent party legislators gradually see the popularity of their party drop in opinion polls. Accordingly, we expect that dissent among incumbent party legislators will increase the longer the party has been in office.Footnote 5

Still, incumbent party legislator dissent could increase with time for other reasons than deteriorating party popularity. In particular, an alternative explanation could be that party dissent is ‘cyclical’ (Lindstädt et al., Reference Lindstädt, Slapin and Wielen2011). This may stem from the logic of the legislative process, where governing parties introduce policies from their manifestos early in the election term (which should enjoy high levels of support from MPs) and postpone difficult legislation with intra‐party disagreement until later in the election term. Hence, we need to show that the effect of the party's time in office on legislator dissent occurs because the electoral cost of ruling increases with time in office. In other words, a party's time in office should induce electoral dissatisfaction, which, in turn, should increase legislator dissent. As Kam (Reference Kam2009, p. 55) also notes: ‘[t]oeing the party line in these circumstances is potentially costly, heightening the MP's incentive to distance herself from the party and making dissent more likely’.Footnote 6 The party's electoral loss while in office should be the theoretical mechanism or mediating variable creating the pathway between the party's time in office and legislator dissent. We are hesitant to make strong theoretical claims about mediating variables, as these are difficult to establish empirically (see, e.g., D. P. Green et al., Reference Green, Ha and Bullock2010). At the same time, we believe that probing theoretical mechanisms is important and that mediation analysis with longitudinal data can be useful when interpreted with the appropriate reservations in mind. As such, we aim to test the full causal chain of our argument: A party's time in office should decrease electoral support for the party, which, in turn, should increase legislator dissent.

H3: The likelihood of government party legislators voting against the party line increases with time in office, and this effect should be mediated by electoral support for the governing party.

Research design

Case selection

As our case, we focus on the House of Commons in the United Kingdom which constitutes a rich empirical case because floor votes are recorded and published over a long period of time and regular polling data are collected and published for the same period. This allows us to estimate models controlling for time‐specific and MP‐specific factors and hereby increase the internal validity of our conclusions.

Four institutional characteristics of the UK political system are relevant to discuss in relation to our theory and tests. First, as explained above, the single member districts offer few opportunities to escape the party image (Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995). The United Kingdom should thus provide a less likely case for detecting the expected patterns compared to multi‐member districts with open lists, where candidates compete within party lists and may benefit from distancing themselves from the party (Crisp et al., Reference Crisp, Olivella, Malecki and Sher2013; Zittel & Nyhuis, Reference Zittel and Nyhuis2019). On the other hand, voters in single member districts are argued to be more likely to reward party dissent (e.g., Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Lancaster, Reference Lancaster1986); yet, comparative work shows that voters also reward dissent outside single‐member district systems because it is perceived as a signal of integrity and commitment to principles over party (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Vivyan and Glinitzer2020). Second, British parties have several control mechanisms at their disposal for maintaining party unity, including campaign financing, assignment to committees and cabinet positions, comparatively centralized candidate selection procedures and, at the extreme, temporary or permanent exclusion (Benedetto & Hix, Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Bille, Reference Bille2001, p. 366; Bøggild & Pedersen, Reference Bøggild and Pedersen2018; Rahat, Reference Rahat2007). Third, the British party system – throughout most of the period studied – featured a sizeable third party (LibDem), which increased the ‘winning party bonus’ of the incumbent party in plurality elections (Hobolt & Klemmensen, Reference Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005). Because the combination of three parties and plurality elections increases the disproportionality between casted votes and seats won, the incumbent party can endure a relatively high cost of ruling without losing seats or office, which should cushion electoral incentives to dissent. Fourth, due to the commonly formed single party majority governments, party responsibility for government decisions is clear in the United Kingdom compared to many other parliamentary systems governed by (minority) coalition governments (Powell, Reference Powell2000). This clarity of responsibility increases the likelihood that the governing party suffers an electoral cost of ruling initiating the hypothesized legislative cost of ruling. Given these four institutional characteristics – election in single member districts, strong party control, electoral disproportionality and single party majority governments – incumbent UK MPs should experience electoral cost of ruling but also face a situation where incentives are not disproportionately strong for acting on these costs compared to MPs in other parliamentary systems.

Data sources

We collected data from three sources. First, to obtain data for our dependent variable (legislator dissent), we collected data on the voting behaviour of all MPs in the UK House of Commons. Specifically, we measured the number of times each legislator dissented from the party line across months and across election terms between 1992 and 2015. We obtained data on floor votes from Slapin (Reference Slapin2017). These data were gathered from http://www.theyworkforyou.com and from the Hansard Archive,Footnote 7 excluding abstention and free votes where no party line is defined (Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018). Our data include 1416 MPs. We operationalize the party line as the position a majority of MPs take on the given bill (Slapin, Reference Slapin2017). We only observe votes cast for proposals that have been put on the parliamentary agenda. This implies that we do not observe all relevant dissent since the majority whip may choose not to put proposals with high levels of intra‐party disagreement on the agenda (Cowley & Stuart, Reference Cowley and Stuart2005). This may imply that the estimate of party legislator dissent we observe as a party enters government is downward biased.

Second, to obtain data for the independent variables related to H1–H3, we collected additional data on the legislator level (seat safety) and party‐level data (parties’ status as governing or opposition party) across election terms between 1992 and 2015. Electoral results of individual MPs were collected from the House of Commons Library.Footnote 8 Parties were categorized as governing or opposition based on the prime minister party except for the period 2010–2015 where Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives formed a coalition government, and both parties were coded as governing parties.

Third, electoral support for the incumbent party was measured using opinion polls. We collected these data from Ipsos MORIFootnote 9 for 1992–2005 and Mark Pack's PollBaseFootnote 10 for 2005–2015. The polls measure voting intentions by asking which party respondents would vote for if a general election were held the next day. Both databases include multiple polls conducted by various polling agencies and collected on different days in the month. We construct a dataset based on the multiple polls including monthly averages of the share of voters intending to vote for the governing party. These running polls are the best estimate MPs have available for evaluating the electoral costs of ruling their party endures.

Operationalization

We measure our variables at two different levels of aggregation. First, to analyse H1–H2, we break down the data to the election term level because the parties holding office vary between (and not within) election terms. Second, for H3, we disaggregate the data further to the monthly level. The extensive and detailed data from opinion polls and MPs’ voting behaviour allow us to track whether incumbent party legislator dissent varies according to the number of months the party has spent in office and monthly changes in electoral support for the incumbent party. Below, we outline measures and model specifications for each approach.

Measures by election term: Testing H1 and H2

The dependent variable is a simple count of the number of times each legislator votes against the party line within each election period. Each observation is an MP in a specific election term. This amounts to 3328 observations in total. On average, an MP dissents 13.55 times in an election term.

We operationalize the two independent variables related to H1 and H2 as follows. First, to test H1, we coded whether legislators belonged to the governing party (coded 1) or an opposition party (coded 0) in the given election term. Second, to measure seat safety and test H2, we collected information on the percentage of votes each legislator obtained over the closest challenging district candidate in the election leading up to the election term (i.e., the size of their electoral margin to the first loser in the district measured in percentage). On average, MPs won their seats with a margin of 21.48 per cent. Importantly, the independent variables are determined causally prior to our dependent variable (dissent during the election term).

Measures by month: Testing H3

The dependent variable is a simple count of the number of times each incumbent party legislator votes against the party line for each month between the 1992 and 2015 elections. Since H3 only relates to incumbent party legislators, our total number of observations is 89,219. Each observation is an incumbent party MP in a specific month. An incumbent party MP on average dissents 0.33 times per month.

We operationalize time spent in government – the independent variable introduced in H3 – by coding the number of months since the MP's party initially formed its government for each observation. Hence, if a party wins re‐election, the number of months in office keep counting rather than return to zero. For example, incumbent party MPs in May 2003 had belonged to a government party for 72 months because Labour had stayed in office for six consecutive years (since May 1997). We drop observations of MPs in the month each election was held. Very few bills are put to the floor in the same month (in our data, below three on average), and these bills relate to procedural matters such as statements to European affairs, loyal addresses, or the planning of bills. These few observations thus stand out from normal policy‐oriented legislation and do not speak to the theoretically relevant tension between following the party line or appealing to voters.

We operationalize electoral support for the incumbent party as the percentage of respondents in the opinion poll data intending to vote for the incumbent MP's party in the given month. We lag this variable by one month for two reasons. First, in many instances, MPs will not be able to respond to a poll by adjusting their vote on bills that are presented on the floor in the same month as the poll is published. Polls will often be published in the middle or end of a month, after which an MP has already cast most of the votes in the given month. Moreover, even when polls are released early, it may be difficult to respond to it instantly because votes are often discussed and coordinated within the party some days before the formal votes are cast (Cowley & Stuart, Reference Cowley and Stuart2005). Second, we want to ensure that our independent variable is determined causally prior to the dependent variable.

Model specification

The panel structure of the data allows us to estimate fixed‐effects models. Specifically, we compare different MPs within the same time period, hereby taking economic growth rates, international events and other relevant time‐specific factors into account while simultaneously comparing the behaviour of the same individual MP across time periods, taking gender, personality, values and other relevant individual‐specific factors into account. In the models analysing how dissent builds over time as the cost of ruling intensifies, we do not include time fixed effects but, instead, control for potential time‐variant confounds in terms of unemployment, economic growth and NHS spending, which could correlate with legislator dissent.

The panel data also allow us to deal with potential issues with reverse causality. Indeed, it is possible that legislator dissent leads to decreasing party popularity among voters rather than vice versa, which could introduce upward bias in our estimates (Clark, Reference Clark2009; Greene & Haber, Reference Greene and Haber2016). We conduct three types of robustness tests. First, we use a lagged‐dependent variable approach that effectively controls out potential feedback on the independent variable (Dinesen et al., Reference Dinesen, Sønderskov, Solhberg and Esaiasson2022; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2018). Although some controversy remains on the use of lagged dependent variables (for a review, see Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2018), the main concern seems to be that it biases against detecting causal effects (Achen, Reference Achen2000) and, if so, this approach should lead to a conservative estimate of the effects. Second, we add a lead on the estimated effect of our independent variables (i.e., adding versions of our independent variables measured at t 1). This allows for a test of whether a change in legislator dissent from t−1 to t 0 correlates with a change in these independent variables from t 0 to t 1. Absent such a correlation, we can be confident that a change in our independent variables is not a function of prior levels of legislator dissent (for applications, see Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Box, Rasmussen, Lindholt and Petersen2022). Third, in the two‐way fixed effects models, we add unit‐specific linear time trends, which capture smooth changes in unobserved confounders. In practice, this corresponds to adding a third set of fixed effects for the interaction between the individual‐ and time variables, which ensures that potentially time‐varying confounding is controlled out (for applications in political science, see, e.g., Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Box, Rasmussen, Lindholt and Petersen2022). While some controversy remains over whether to include unit trends, the concern is that it may constitute a conservative test by biasing coefficients towards zero (Goodman‐Bacon, Reference Goodman‐Bacon2021).

There are outliers of strongly rebellious MPs such as John McDonnell (Labour) in the 2005–2010 election term and Philip Hollobone (Conservative) in the 2010–2015 election term. We include all outliers in the analyses reported in the main text to maintain external validity, but in the Online Appendix, we replicate our findings with one‐limit Tobit regression models in which we restrict the analyses to observations within two standard deviations above the mean to rule out biased estimates from outliers. This is important because legislators exhibiting extreme levels of dissent could potentially hold different motives for dissent and inflate our estimates (Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018). However, all Tobit regression models leaving out such outliers replicate the findings presented below.

Since the dependent variable is essentially a count measure, we rely on Poisson regression to illustrate how dissent rates differ across groups of MPs and over time. We replicate all reported findings using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression in the Online Appendix. We cluster the standard errors at the legislator level to account for potential issues with autocorrelation.

Results

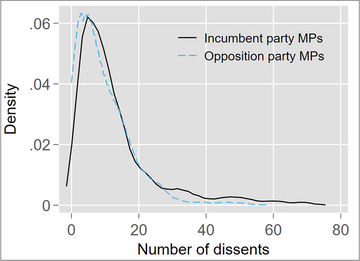

Does the likelihood of legislators voting against the party line increase when their party is in government (H1)? As an initial illustration, Figure 1 plots the distribution of the number of dissents by legislators from all election periods across MPs belonging to the incumbent and opposition parties. Based on the raw data, Figure 1 shows that dissent is generally low. In line with existing institutional explanations of legislative behaviour, this indicates that party cohesion in Britain is comparatively high (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2006, p. 161). Still, even in this context, dissent does occur and is, as hypothesized, more pronounced among legislators of parties in government (M = 16 dissents) relative to opposition parties (M = 10 dissents). The difference amounts to an additional 5.5 dissents from the party line, suggesting incumbent party MPs dissent 55 per cent more compared to opposition party MPs (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Distribution of observations by number of dissents in election period across incumbent and opposition party MPs. Epanechnikov kernel density plot. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

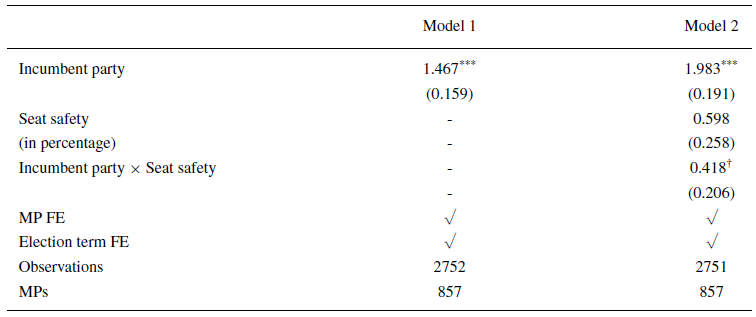

The formal test of H1 is reported in Model 1 (Table 1) and reveals a very similar pattern. The reported incidence rate ratio shows the difference in dissent rates when a legislator's party is in office relative to in opposition with individual and election term fixed effects. This coefficient shows the change in dissent among legislators when their party enters government compared to the change in dissent among legislators in the same period whose party does not enter government. In line with Figure 1, legislators dissent more as their party enters government as their dissent rate increases by 46.7 per cent (p < 0.001). This supports H1 and our general argument that the cost of ruling for governing parties serves as a catalyst of legislator party dissent: Legislators become more inclined to vote against the party line when their party enters government.Footnote 11 Analyses reported in the Online Appendix corroborate these results using OLS regression (see Online Appendix A) and one‐limit Tobit regression excluding outliers (see Online Appendix B). Finally, we consistently find that party incumbency affects dissent rates rather than vice versa using lagged models, lead models and models controlling for unit‐specific linear time trends (see Online Appendix C).

Table 1. Effects of incumbent party and 1 seat safety and interaction between these variables on legislator dissent (H1–H2).

Note: Incidence rate ratios from fixed effects Poisson regression models with MP‐level clustered standard errors in parentheses. √ indicates that models are run with MP and Election term fixed effects. †p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. All tests are two‐sided.

Abbreviations: FE, fixed effects: MP, member of parliament.

Still, the tendency for legislators to dissent when their party is in office could reflect other motivations than a need to distance oneself from an unpopular incumbent party, such as ideological positioning among extreme legislators, constituency representation or protests for being overlooked for cabinet positions (e.g., Benedetto & Hix, Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Tavits, Reference Tavits2009; Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018). Below, we test the remaining hypotheses to further substantiate that incumbent party legislator dissent does, in part, reflect motivations to appeal to voters and obtain re‐election as their party incurs a cost of ruling among the electorate.

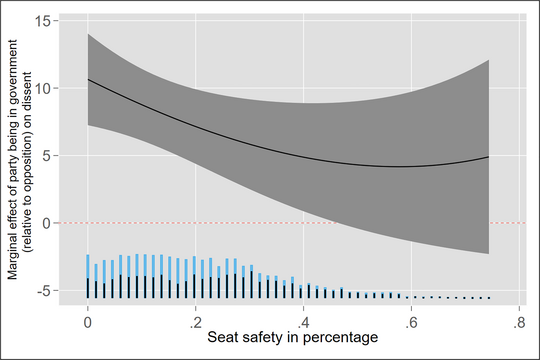

Does the tendency for legislators to vote against the party line when their party is in government increase as seat safety decreases (H2)? As outlined above, this test is important because it brings us closer to the proposed theoretical mechanism behind H1 and serves as an additional observable implication of our argument that incumbent legislators distance themselves from their unpopular governing party as a strategic means to secure the necessary votes to obtain re‐election. To test this, we include the seat safety variable and interact it with the incumbent party variable including individual and election term fixed effects. The results are presented in Model 2 (Table 1). As expected, the incidence rate ratio for the interaction term is below 1, meaning that the tendency for legislators to dissent more as their party enters government – relative to being in opposition – is strongest among those in unsafe seats and becomes gradually weaker as the percentage of votes obtained over the challenger increases. However, this interaction effect is only marginally significant (p = 0.077). Figure 2 illustrates why: As depicted, the interaction is best described as a non‐linear relationship rather than the linear relationship proposed in H2 and tested in Model 2, Table 1. MPs’ tendency to dissent more as their party enters government does indeed decrease as their seat safety increases but only up to a certain level (about 50 per cent votes more than the first challenger) after which the difference no longer decreases and becomes statistically insignificant. As a post hoc reflection, this makes sense theoretically since MPs may become so electorally safe that additional safety does not change their legislative behaviour. In other words, we observe a threshold at which seat safety no longer affects how MPs respond to the electoral cost of ruling associated with government. In line with the non‐linear account, we observe that the interaction is statistically significant (p = 0.046) when restricting the analysis to MPs with a seat safety below 50 per cent (i.e., 95.6 per cent of MPs).Footnote 12 The data thus provide partial support for H2 with the important qualification that seat safety only attenuates MPs’ tendency to dissent more when in government up to a certain point. Again, these results replicate using OLS regression (Online Appendix A) and when excluding outliers using one‐limit Tobit regression (Online Appendix B). The results substantiate our general cost of ruling argument that legislators dissent more from the party line once the party enters office and loses popularity as a strategic means to appeal to voters and obtain re‐election.

Figure 2. Does the marginal effect of party incumbency on dissent (y‐axis) decrease with legislators’ seat safety (x‐axis)? The cumulative bars at the bottom of the figure show the distribution of legislators across the seat safety variable among incumbent (black bars) and non‐incumbent (blue bars) party legislators, respectively. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Does the likelihood of incumbent party legislators voting against the party line increase the longer the party has been in government, and is this effect mediated by electoral support for the incumbent party (H3)? To test this hypothesis, we zoom in on legislators whose party is in office and observe monthly changes in dissent rates for each incumbent MP over time as the number of months in office increases (i.e., within‐legislator variation). By disaggregating the data to the monthly level, we obtain more fine‐grained measures with monthly data points over the 23‐year period. Naturally, there is no variation across legislators in the number of months passed since the party took office when holding time constant (i.e., between‐legislator variation). Thus, in contrast to the results reported above, we estimate individual‐level fixed effects models without holding time constant but, instead, add controls for unemployment, GDP and NHS spending.

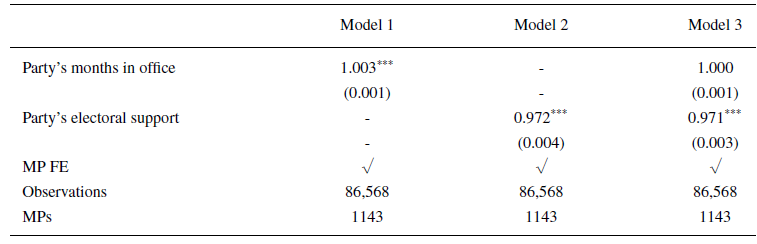

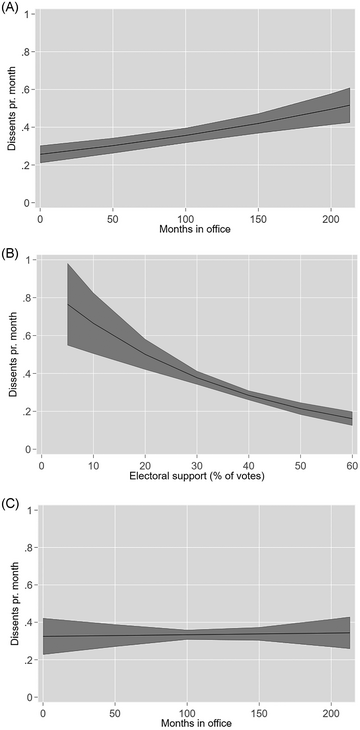

We test H3 in three steps. First, the dissent rate among MPs of the office‐holding party should increase with the number of months their party has spent in office. The results in Model 1, Table 2 show that an incumbent party legislator's dissent rate on average increases by 0.3 per cent from one month to the next. The effect is illustrated in Panel a of Figure 3. The panel depicts that the predicted number of dissents increases by 0.056 from the first month after the party takes office (0.257 dissents) to 60 months after the election (0.313 dissents) (a typical election term) and increases by 0.26 after 213 consecutive months in office, the largest value in our dataset. At first glance, this may seem like a trivial effect size. However, the effect adds up when considering the number of MPs who engage in such behaviour. For instance, the second Major ministry (1992–1997) held office for 60 months. The government majority was slim with Conservatives winning only 336 seats in the 1992 General Election. According to our model, a government like the Major government would, on average, face an additional 18.82 (0.056 × 336) dissents from incumbent party MPs in the last month of the election term compared to the first month. Given the limited size of the government's majority, this is a significant increase and threat to the legislative capacity of a government. The reported results hold up in additional robustness tests using OLS and one‐limit Tobit regression. Additional analyses (see Online Appendix D) reveal that the reported relationship is in fact linear. Dissent builds steadily over time (like the cost of ruling) and does not intensify exponentially when an election approaches (whether measured as 3, 6, or 12 months prior to an election). Moreover, dissent continues to rise steadily after a party obtains re‐election and enters its second term of government. These findings are important because they indicate that increasing dissent over time cannot be explained by dissent being ‘cyclical’. If this were the case, dissent should rise exponentially over time and fall after governments win re‐election, but our data clearly show that it builds steadily. These results are consistent with our main argument that incumbent party legislators face growing incentives to dissent from the party line as the electoral cost of ruling for the party builds up over time (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad, Paldam, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017). Still, in principle, legislator dissent could increase with the number of months the party holds office for reasons other than gradual declining support for the party among the electorate. To further substantiate our argument, we turn to analyses of the mediating role of electoral support for the incumbent party.

Table 2. Effects of the party's number of months in office and electoral support on legislator dissent (H3).

Note: Incidence rate ratios from fixed effects Poisson regression models with MP‐level clustered standard errors in parentheses. √ indicates that MP fixed effects are included. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. All tests are two‐sided.

Abbreviations: FE, fixed effects; MP, member of parliament.

Figure 3. Is monthly incumbent party legislator dissent (y‐axis) affected by the party's number of months in office and electoral support (x‐axis)?

As a second step in testing H3, we test whether incumbent party MPs dissent more when their party loses electoral support. Paralleling the analysis above, we estimate individual‐level fixed effects models and observe how dissent of each legislator varies across months according to variation in electoral support for the party of the legislator. The results are reported in Model 2, Table 2. As we should expect, the reported incidence rate ratio is below 1, meaning that incumbent party legislator dissent increases as the percentage of the electorate supporting the incumbent party decreases (and vice versa). The 0.972 coefficient implies that when electoral support for the incumbent party drops by one percentage point from one month to the next, each incumbent MP dissents 2.8 per cent more in the following month. This effect is illustrated in panel b of Figure 3. Moving from half a standard deviation below to half a standard deviation above the mean (i.e., a 10.357 percentage point change) results in an additional 0.095 dissents for incumbent MPs per month. While governing parties rarely lose 10 percentage points support in one month, such a change is likely over several months as losses accumulate. Again, these numbers add up to significant legislative behaviour: A governing party with a minimal majority (326 MPs) will, on average, face an additional 30.97 dissents as a result of the one standard deviation drop in electoral support (0.095 × 326). The relationship is illustrated graphically in panel b of Figure 3. As shown, incumbent MPs whose party receives support from only five per cent of the electorate (the smallest value we observe in our data) dissent 0.74 times a month.Footnote 13 In contrast, when an incumbent MP's party enjoys the support of 61 per cent of the electorate (the highest value we observe), the MP dissents only 0.16 times in a month. The results remain robust when we use OLS and one‐limit Tobit regression and when running lagged and lead models to accommodate potential reverse causality (see the Online Appendix). These results further support our argument that incumbent party legislator dissent intensifies along with the electoral cost of ruling.

As the third and final step, we test if the established effect of a party's number of months in office on legislator dissent can be ascribed to the gradual loss of support among the electorate. A simple test of this argument is presented in Model 3 (Table 2), in which the party's time in office and its electoral support are included in the model simultaneously. In line with H3, we see that the significant effect of the party's months in office on legislator dissent established in Model 1 disappears and becomes statistically insignificant in Model 3 (p = 0.933). Hence, when controlling for the party's electoral support, the incidence rate ratio changes from 1.003 to 1.000. This latter coefficient implies that the dissent rate is identical across months after electoral support is accounted for. This is illustrated graphically in panel c of Figure 3, which depicts no relationship between months in office and legislator dissent. Comparing panel a and panel c suggests that the relationship between the party's months in office and legislator dissent is driven or accounted for by the party's electoral support. Again, these results fully replicate with OLS and one‐limit Tobit regression (see the Online Appendix).

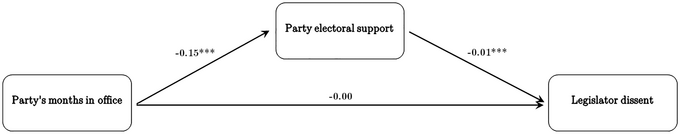

The formal test of this argument based on structural equation modelling with MP fixed effects is presented in Figure 4. The figure shows the exact causal relationship hypothesized in H3. As the number of months an incumbent MP's party in office increases, the party's electoral support diminishes (as demonstrated in the existing cost of ruling literature). In turn, this drop in electoral support increases incumbent party legislator dissent. Finally, we test whether this pattern is stronger for backbenchers compared to frontbenchers. Following our theory, backbenchers should be at higher risks of losing their seat when the electoral support of their party declines and, in turn, dissent more to maximize their chances of staying in office compared to frontbenchers (i.e., ministers) who may be more insulated from changes in the party image (Martin, Reference Martin2014a).Footnote 14 As expected, backbenchers are substantially and significantly more inclined to respond with higher dissent rates as their party's popularity decreases over time (see Online Appendix E for full results).

Figure 4. Is the effect of the party's months in office on legislator dissent mediated by electoral support for the party? Structural equation model with MP fixed effects.

Overall, these results support our proposed theoretical mechanism and further rule out other alternative explanations such as dissent being cyclical. Mounting dissatisfaction with governing parties among voters over time accounts, at least in part, for incumbent party legislator dissent from the party line. The electoral cost of ruling can thus translate into a legislative cost of ruling with important downstream consequences for party unity and discipline in parliamentary voting.

Discussion

It is well established that governing parties incur an electoral cost of ruling. In this article, we demonstrate that such electoral costs have broader implications as they translate into legislative costs in the form of dissent from the party line among individual MPs. Specifically, we argue that the electoral cost of ruling for governing parties serves as a catalyst for legislator party dissent. We develop several expectations based on this argument and establish empirical support for them with panel data on the voting behaviour of all MPs in the UK Parliament between 1992 and 2015, combined with MP‐level election results and monthly opinion polls.

On the one hand, this finding indicates a challenge to party democracy at large. The cost of ruling spill‐over into the legislative work of the party makes party governance more difficult and potentially less efficient. The cost of ruling not only forces parties out of office but may also lead to inefficient policymaking or even unduly government termination. The findings also point to strategic challenges facing political parties. Due to the cost of ruling, political parties face a dilemma between taking on the responsibility of governing and maintaining electoral support and intra‐party unity. This may help explain why some parties are averse to entering government or leave government coalitions between elections.

On the other hand, the finding may also bode well for electoral accountability. After all, our results suggest that legislator party dissent reflects a motivation to please voters, and that dissent and inefficient governance is mainly imposed on a party when it loses support among the electorate. Incumbent party legislator dissent may thus constitute a democratic adjustment mechanism constraining the governing capacity of parties that have lost their electoral mandate. In this sense, the cost of ruling phenomenon may be perceived as a boon for democracy. From this perspective, dissenting legislators correct issues with unresponsive party elite governance and promote democratic rule. Just as the electoral consequences, these legislative consequences stemming from the cost of ruling may be perceived as a risk as well as a possibility for making party democracy work.

Three potential limitations warrant mentioning. First, we propose vote‐seeking motivations for legislators to dissent in response to the cost of ruling from the electorate. While our empirical results align with this idea, our data do not allow us to determine if legislators in fact consciously use dissent as a signal to voters. Alternative mechanisms such as loosening party control or increasing intra‐party frustration from decreasing electoral support may also account for the relationship, especially given that such control and frustration are more relevant for marginal MPs. However, the main result still stands; electoral costs translate into legislative costs of ruling, and experimental and observational studies demonstrate that MPs may indeed benefit electorally by dissenting from their party (Bøggild & Pedersen, Reference Bøggild and Pedersen2020; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019). Second, it is possible that MPs strategically choose to dissent at times when the governing party has a large enough majority to pass its legislation (Ceron, Reference Ceron2015) thus reducing the legislative cost of ruling. Still, governing parties sometimes do fail to muster support for important bills and abstain from putting bills to the floor due to anticipated lack of support (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Cowley & Stuart, Reference Cowley and Stuart2005; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Müller and Strøm2000, pp. 584−587). This likely reflects that dissent most often occurs when government bills are unpopular and on conflictual rather than valence issues. This suggests that dissent resulting from decreasing electoral support can indeed endanger effective party governance, especially on some contentious issues where legislators have additional motives for disrupting party policy. Third, while our focus has been to understand dissent within government parties (since they, by definition, incur the electoral cost of ruling), more research is needed for understanding motivations for dissent within opposition parties. It is likely that opposition MPs also respond to changes in their party's popularity and, in turn, that the opposition may become more unified when the electoral cost of ruling tears on governing parties.

We have tested our theory using rich and detailed data on the British case. The British case is, as any other case, unique in some respects. We expect that our theory is widely applicable due to the consistent cost of ruling phenomenon across countries and the institutional circumstances in Britain, that make the stated mechanisms relevant but not most likely as they would be in highly candidate‐centred systems such as the United States (Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2013) or strongly intra‐party competitive systems such as Poland (André et al., Reference André, Freire, Papp, Deschouwer and Depauw2014). Indeed, the cost of ruling does vary somewhat in degree across institutional settings (e.g., clarity of responsibility) and government performance (e.g., Palmer & Whitten, Reference Palmer, Whitten, Dorussen and Taylor2002) and our findings may thus be subject to contextual moderators and scope conditions. We hope that future work will extend our model by addressing how political context may moderate our findings.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the paper were presented at APSA 2021 in the panel on Strategic Choices in Changing Environment, at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research, and in the research section on Political Behaviour and Institutions at Aarhus University. We thank participants for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. We thank the Independent Research Fund Denmark (project number 4182‐00065B) for supporting the research and three anonymous reviewers for providing insightful reviews and assisting us in improving the research.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A: OLS Regression Analyses

Appendix B: Tobit Regression Analyses Excluding Outliers

Appendix C: Analyses testing for reverse causality

Appendix D: Non‐parametric estimation of relationship between party's months in office and legislator party dissent

Appendix E: Heterogeneous effects across front‐ and backbenchers

Supporting information