Introduction

In the summer of 2022, two women named Funda and Gönül squared off across an elaborate tablescape on the popular Turkish reality TV show Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz (We’re at the Table with Zuhal Topal). Wine glasses remained empty or were filled with cola — images of alcohol have been blurred on Turkey’s televisions since 2013. Because elegance and hospitality factor into the points that five contestants award each other during the program’s week of competition, however, most hosts offer fancy stemware on their day to cook in their home. Throughout this episode, tank top-clad Funda, sporting a neck tattoo and a bleached top-knot, had argued vociferously with several competitors, including a male contestant who criticized her “sloppy” hairstyle (episode 209). Funda then turned to Gönül, a veiled woman who previously shared she sewed her modest clothing herself but had stayed quiet during this exchange. When Funda demanded to know why Gönül hadn’t spoken, the latter replied: “you don’t give me the chance to talk.” Throughout the week, Funda spoke up stridently while Gönül largely remained demure. In the week’s final episode, headscarf-wearing Gönül won the competition and received a cash prize. Midriff-baring Funda came in last place and received a wave of vitriol via YouTube comments.

What can this brief scene from a cooking competition show tell us about women’s roles in contemporary Turkey and beyond? What leverage can we gain on the politics of gender and other forms of identity by focusing on everyday entertainment forms like television? Scholars of culture and communication argue that despite the proliferation of social media platforms, television programing is “one of the best means to study national politics” as it remains the “dominant media form” in many parts of the world (Osman Reference Osman2020, 13). Examining the content of television, the context in which it is produced, and the conversations around it can serve to map the contours of political debates. As political scientists argue in drawing on such insights in their research, television shows and other popular culture genres can provide useful empirical windows onto identity dynamics at societal and state levels (Hintz Reference Hintz2018; Moïsi Reference Moïsi2016; Pratt Reference Pratt2020).

Beyond merely reflecting existing identity discourse, television as a content distribution platform can also serve to shape that discourse (Sellnow and Endres Reference Sellnow and Endres2024; Van Zoonen Reference Van Zoonen2005). Studying television thus enables researchers to illuminate the literal channels through which actors seek to disseminate their particular understanding of national, ethnic, gender, and other forms of identity. Television content can impart values, behavioral norms, and other identity components as defined by political elites to audiences in ways similar to nation-building institutions such as education systems (Ansell and Lindvall Reference Ansell and Lindvall2013; Bereketeab Reference Bereketeab2020; Lomsky-Feder Reference Lomsky-Feder2011; Paglayan Reference Paglayan2022) and militaries (Beattie Reference Beattie2001; Koonings and Kruijt Reference Koonings and Kruijt2002; Posen Reference Posen1993), but in a more efficient and engaging manner. On gender specifically, anthropologists such as Lila Abu-Lughod (Reference Abu-Lughod2008) and Purnima Mankekar (Reference Mankekar2000) usefully detail the moral frameworks in drama serials that are designed to convey a specific understanding of women’s place in the nation in engaging ways. Notably, both these scholars highlight women viewers’ reactions — and in some cases objections — to the dramatic rendering of regime-led projects such as Egypt’s “feminist developmentalism” (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2008, 108). The authors nevertheless agree that governing officials approach television as a cultural engineering tool for molding societal beliefs about appropriate attributes and behavior for women. Considering the facts that 95% of Turkish citizens own a TV, that average viewing for adults was more than three hours per day in 2023 (Dierks Reference Dierks2024), and that the ruling party has exercised influence over 90%–95% of mainstream media channels for at least five years (Country Profile: Turkey 2019), television provides a platform extremely well-suited for mass-mediated gender construction in Turkey.

In this article I tackle this case, unpacking the ways in which popular cooking shows disseminate government-defined roles for women in authoritarian regimes. Whereas the traditionally gendered tasks of at-home meal preparation, home maintenance, and hospitality that comprise most of the subject matter in cooking shows on the airwaves in democratic regimes as well, the political economy of authoritarian media ecosystems provides ruling actors with substantial influence over televised content even on private channels. Surprisingly, although cooking shows’ gendered subject matter and audience demographics would suggest they are a particularly attractive platform for autocrats’ gender agendas, my review of political science journals found no articles on cooking shows. I fill this gap by developing the concept of conservative gender edutainment. Footnote 1 Specifically, I argue that two distinct but complementary gender pedagogies embodied in food television programming — modeling and othering — make cooking shows especially apt for conveying instructional messages to women on particular behaviors and attributes as part of wider processes of constructing gender roles.

I explore these conservative gender edutainment dynamics in “New Turkey,” a socio-political vision promulgated over the last decade by the ruling AKP. Contemporary Turkey’s competitive authoritarian regime serves as a particularly useful case with which to connect regimes’ normative identity projects and instrumental durability motivations to mass-mediated entertainment. In addition to the AKP’s highly consolidated formal institutional control, the widespread institutional capture of the Turkish media landscape by the government also offers propitious conditions for analytically linking regimes’ identity politics to televised gender construction on private media channels (Akser and Baybars-Hawks Reference Akser and Baybars-Hawks2024; Yesil Reference Yesil2016). Further, while Turkey’s so-called “headscarf ban” is an oft-cited example of women and women’s bodies as battleground, the country has many deep historical and contemporary connections between gender roles and nation-building (Gökarıksel Reference Gökarıksel2012). Recent work on the gendered nature of Ottoman-infused Islamic populism under the AKP (Fisher-Onar Reference Fisher-Onar, Raudvere and Onur2023, 10), for example, illustrates how practices and policies targeting women such as pro-natalist legislation were fundamental in replacing what I term a prevailing Western-oriented, secular “Republican Nationalist” identity with that of a pious Muslim who celebrates Turkey’s imperial legacies (Hintz Reference Hintz2018).

In advancing my argument, I first briefly review the literature on how television can serve authoritarian regimes’ identity projects, with a focus on women’s roles. Next, I discuss the institutional and political economy dynamics that shape mass-mediated gender construction in the New Turkey context and specify the AKP’s vision of the “ideal female citizen.” Third, I introduce modeling and othering as complementary conservative gender edutainment pedagogies, and then detail the mixed-methods approach I use to study them in cooking shows. Fourth, I present my analysis of how these shows disseminate regime-adherent gender content and marginalize regime-deviant qualities and behaviors in enjoyable and thus innocuously persuasive ways. I conclude with suggestions for future study of gender, television, and authoritarianism.

Politics of Identity On/Through TV

Political science forays into the realm of television are thus far largely in the domain of International Relations (IR). As IR scholars acknowledge, pop culture content such as TV programming serves as a channel through which “power, ideology, and identity are constituted, produced, and/or materialized” to shape hostile beliefs that include interstate rivalries and other forms of conflict (Grayson, Davies, and Philpott Reference Grayson, Davies and Philpott2009, 156). Scholars of popular geopolitics illustrate that regimes often wage highly conflictual power struggles in competition over the production, organization, and inscription of political meaning onto space through cultural products (Saunders Reference Saunders2019; Tuathail and Toal Reference Tuathail and Toal1996). Yet comparativists can also find much to study in television’s role in constructing Us and Them dichotomies in the domestic sphere. Media studies scholars, sociologists, and anthropologists point to the role of drama series, news programs, and other TV genres in defining and disseminating specific understandings of national identity (Armbrust Reference Armbrust2000; Mankekar Reference Mankekar2000).

Ostensibly an entertainment platform, everyday television programming can serve as a seemingly innocuous extension of public sphere forms of regulation into the private (Kocamaner Reference Kocamaner2017; Ouellette and Hay Reference Ouellette and Hay2007; Pratt Reference Pratt2021). Viewers are supplied with “techniques to govern their own conduct” in ways that “normaliz[e] hegemonic discourses” while being entertained in the comfort of their own homes or via the convenience of their portable screens (Sayan-Cengiz Reference Sayan-Cengiz2020, 230). While television can contribute to the construction and dissemination of particular identities in all types of regimes, much of the nation-building-on-TV literature points to television as a media tool that is especially attractive for authoritarian regimes — what two of the few political scientists studying television term “soft propaganda” (Mattingly and Yao Reference Mattingly and Yao2022). Studies demonstrating that entertainment television can spark debates among viewers about the types of identities represented onscreen suggest that authoritarians’ patrolling of this content is crucial in controlling competing narratives (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2008; Kraidy Reference Kraidy2009; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1991). Indeed, comparative study demonstrates that, along with news media, authoritarians regulate the production and dissemination of programming from drama series to cartoons to reality competition shows (Bai and Song Reference Bai and Song2014; Qu Reference Qu2019; Ribke Reference Ribke2011). Intertwined with the normative motive of advancing authoritarians’ nation-building projects, the policing of television and other popular culture forms can also evince regime motives familiar to comparativists but not often studied by them.Footnote 2 Studies outside political science examine, for example, strategies of bolstering regime durability by censoring content that threatens legitimacy and producing content that supports it (Bajoghli Reference Bajoghli2019; Li Reference Li2019; Tan Reference Tan2016; Van Zoonen Reference Van Zoonen2005).

By definition, authoritarians come well-equipped with the tools for engaging in such regulation. Political economy and institutional factors provide nation-building autocrats with greater access to and control over media outlets to encourage such normalization than their democratic counterparts. Although news production and journalism–state relations are more traditional objects of focus for comparative studies of media and regime type (Repnikova Reference Repnikova2017), in authoritarian regimes, clientelism frequently combines with formal censorship via state institutions to provide autocrats with outsize regulatory and productive power in the culture industry as well. Factors such as ownership of media outlets by actors with close ties to the government, interventions by state regulatory agencies, and anticipatory compliance by producers seeking the regime’s favor enable the policing of televised content that offends, contravenes, or threatens a leader’s vision for the nation, while also supporting the production of content in line with it (Anderson and Chakars Reference Anderson and Chakars2015; Nötzold Reference Nötzold2009; Yesil Reference Yesil2016).

Turning the spotlight on gender, women’s roles are central in televised nation-building projects and thus are heavily policed in authoritarian regimes as studies of drama serials, talk shows, and reality programs illustrate. Feminist scholars illustrate how women’s bodies and behaviors often serve as the “ultimate marker” of the nation, entailing that “every aspect of women who appear on screen is scrutinized for appropriateness” (Osman Reference Osman2020, 156). Work by scholars such as Lila Abu-Lughod (Reference Abu-Lughod2008) and Purnima Mankekar show how women are both the subject of and audience for regime messaging on patriotic ideals of developmentalism and of a particularly “Indian Womanhood” as a complement to militaristic nationalism, respectively (Mankekar Reference Mankekar2000, 40–1). Importantly, media scholars working on gender emphasize that it is not just government officials delivering these messages policing women’s actions and appearances, but also show characters, contestants, and even viewers. This takes on an added dimension in the reality TV genre, where women who participate as contestants face the prospect of becoming “icons of their nation” for better and worse, attaining the national spotlight but having their every move onscreen and off scrutinized in the media (Kraidy Reference Kraidy2009, 196). Also drawing on reality TV but in a democratic context of the United Kingdom, Angela McRobbie highlights the role of “wounding comments” in class-based policing and body-shaming by show hosts that the author finds reminiscent of boarding school “bitchiness” (2004, 102).Footnote 3 That bitchiness is not reserved for English schoolchildren, as the derogatory comments made toward Funda in our opening vignette and in YouTube responses briefly discussed below make clear.

On the Menu: (New) Turkey

Here I identify the institutional, political economy, and discursive connective tissues that tie media content to gender construction projects in authoritarian regimes using the context of “New Turkey.” The term can be defined as “the social and political order under the party’s rule [that] is maintained by a new set of norms and values” (Korkut and Eslen-Ziya Reference Korkut and Eslen-Ziya2016, 13). Ruling party members began using the term to articulate a vision for a stronger and more conservative Turkey between the AKP’s third electoral victory in 2011 and Erdoğan’s first presidential run in 2014. The combination of crony capitalist-fueled power consolidation and identity polarization that have transpired in the New Turkey era make the case particularly well-suited for studying the politics of mass-mediated gender construction.

Beginning with political institutions, Turkey’s ruling AKP has been in power for over 22 years at the time of writing. The party governed with a parliamentary majority in its first four terms and then via a highly consolidated executive presidency with Erdoğan at the helm (Esen and Gümüşçü Reference Esen and Gümüşçü2017). The duration of the party’s rule and the amount of political power the AKP has amassed are manifest in its significant control over the institutions implicated in the politics of defining Us and Them, including the military, the judiciary, and the education system (Hintz Reference Hintz2018). In the media sphere, this political control extends to institutions such as the state-run Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), which broadcasts over a dozen channels in multiple languages at home and abroad, as well as to the state’s regulatory body in charge of media licensing and supervision, the Supreme Board of Radio and Television (RTÜK). Although RTÜK’s nine-member leadership structure entails that members are selected by parliament and that opposition parties are included, actual representation reflects party quotas, giving the AKP and its nationalist electoral alliance partner heavily weighted influence over decision-making (Interview with RTÜK board member 9 August 2022). This influence translates into media regulation that mimics political power patterns. Regulation includes frequent fines and broadcast bans on opposition-owned Halk TV, as well as the conservative policing of content themes such as morality, family values, and religion. In addition to RTÜK’s formal punitive power, Turkey’s Tax Ministry engages in selective punishment of private media outlets deemed by the government to be airing unacceptable or politically unflattering content (Yesil Reference Yesil2016). Gökhan Bacık demonstrates how RTÜK actions such as broadcast bans on a channel showing same-sex kissing scenes and blurring of references to alcohol contributes to “informal Islamization” (Reference Bacık2022). Notable for this paper’s focus on women’s roles, a highly popular TV drama serial with strong women protagonists became the target of a RTÜK broadcasting ban in the months leading up to the May 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections. The ban against Kızılcık Şerbeti (Cranberry Sorbet) purportedly was issued for a scene containing violence against women — head-scarved Nursema is assaulted and pushed out of a window by the conservative man she was forced to marry. The fact that on April 14, network executives were pressured into airing a documentary about Islamophobia that RTÜK had sent to Show TV instead of Episode 23 supports claims that government officials were sanctioning critical portrayals of conservative societal sectors rather than violence against women (Altınordu Reference Altınordu2023; Show TV’den Kızılcık Şerbeti açıklaması 2023); Nursema became a feminist icon for pious and secular opposition members alike (KAFA on Instagram 2023).Footnote 4

Turning to political economy factors, the clientelism that undergirds the party’s rule facilitates significant governmental influence over media content. Massive holding conglomerates such as Demirören, Doğuş, Kalyon, and Ciner possess assets that include media outlets, but locate their most profitable enterprises in the construction, mining, banking, and other sectors. These holding groups, many of which have ownership structures with personal and even familial ties to the AKP, regularly seek government favors such as low-interest loans, limited government oversight on development projects, and privileged tenders. Such groups thus have incentives to use their (sometimes even debt-incurring) media outlets to broadcast coverage of which the government approves (Esen and Gumuscu Reference Esen and Gumuscu2018; Tunç Reference Tunç2018; Yesil Reference Yesil2016). In turn, the government can reward conglomerates with regime-friendly media outlets such as Show, Star, aTV, and Kanal D by auctioning off the assets of other media companies seized due to (often politically induced) financial trouble at highly reduced rates and by purchasing advertising space (Tunç Reference Tunç2018; Yanatma Reference Yanatma2021).

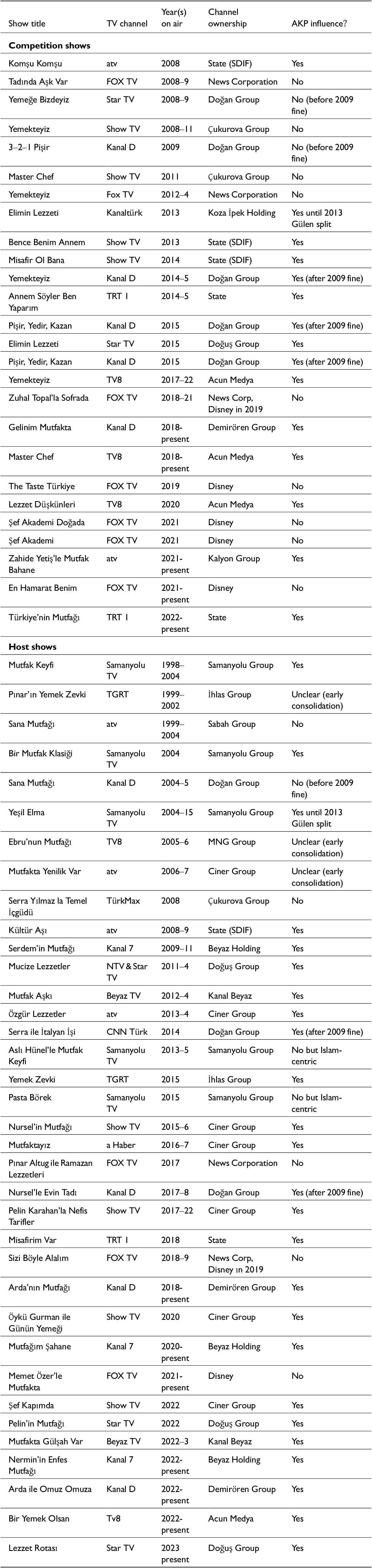

The expansion of this crony capitalism had significant effects on the increasing alignment of entertainment TV programming with the AKP’s vision (Algan and Kaptan Reference Algan and Kaptan2023; Bulut and İleri Reference Bulut and İleri2019; Çevik Reference Çevik2020). In the cooking genre, of the 62 host and competition shows that aired during the AKP’s tenure from 2002 to 2022, 39 were aired on channels owned by pro-AKP holding companies or the state (including the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund, the institution that took over failing assets); in the post-Gezi era after 2013, 34 of 44 of these types of cooking shows were in regime-friendly hands (see Appendix 1). Providing the important link between TV content viewing and regime-driven “cultural engineering” (Algan and Kaptan Reference Algan and Kaptan2023), interdisciplinary research on the Turkish case compellingly documents the intense involvement of regime actors in the production, oversight, and censorship of entertainment television as well as news media (Bulut and İleri Reference Bulut and İleri2019; Çevik Reference Çevik2020; Emre Cetin Reference Emre Cetin2014). Whereas Kocamaner offers evidence of how Islamic conservatives in Turkey’s TV industry create content that supports the AKP’s “strengthening the family” narrative (Reference Esen and Gümüşçü2017), for example, Algan demonstrates how even “non-believers” among industry executives and production teams have adopted tactics to avoid censure (and remain profitably employed) by carefully managing programming content in response to, and in anticipation of, government demands (Reference Algan2020). These tactics by industry professionals producing content for private TV channels reflect a vast network of crony capitalism that further positions Turkey as a fruitful case for inquiry.

Finally, to draw the explicit link between the content of the identities portrayed favorably and unfavorably on the airwaves to regime politics (Bulut and İleri Reference Bulut and İleri2019; Çevik Reference Çevik2020), I present a brief overview of the AKP’s articulation of its vision of the ideal women. Whereas the party’s discourse on gender more broadly contains multiple dimensions that intersect with media — including hypermasculine prescriptions for men as protectors of the nation, embodied in Valley of the Wolves character Polat Alemdar’s “paramilitary hero” (Çetin Reference Çetin2015; Yanık Reference Yanık2009); and virulent proscription of LGBTQ+ identities, particularly following the AKP’s 2023 election victory and an AKP-adjacent conservative family platform’s campaign to brand queer identities in TV and film as “socio-cultural terrorism” (Sanatta Dayatma ve Sosyokültürel Teröre “DUR” diyoruz! | Büyük Aile Platformu 2023) — I limit my scope here to the party’s discourse on women.

As De Cillia, Reisigl, and Wodak demonstrate (Reference De Cillia, Reisigl and Wodak1999), discourse can serve as a key governance tool for defining and disseminating national identity. Regarding gender as a component of that identity, analysis of AKP pro-natalist statements demonstrates how “discursive governance” enables political leaders to govern even “without introducing major policy changes” (Korkut and Eslen-Ziya Reference Korkut and Eslen-Ziya2016, 555). Whereas institutional moves such as cash transfers for new mothers and government support for reproductive technology (Kocamaner Reference Kocamaner2019) serve as formal enactments of the AKP gendered biopolitical agenda (Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti2016; Ongur Reference Ongur2015), leaders’ statements and politically curated media content also serve as discursive tools in defining and governing Us and Them. Synthesizing insights from work on identity politics and authoritarian populism under the AKP, we see that the discursively defined Us, or the part of the population acceptable to the rulers as “the people,” is comprised of pious Sunni Muslims who revere Ottoman legacies, respect patriarchal order, and welcome the firmly governing hand of Erdoğan himself (Fisher-Onar Reference Fisher-Onar, Raudvere and Onur2023; Hintz Reference Hintz2018). AKP rhetoric makes clear that the women within that Us are modest, motherhood-oriented women who uphold the “heteropatriarchal ideals” Erdoğan sought to promulgate (Yabancı and Sağlam Reference Yabancı and Sağlam2023). Indeed, motherhood constitutes a biopolitical prerequisite for the “pious generation” that AKP cofounder, prime minister, and now President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has repeatedly stated he seeks to raise (Dindar nesil yetiştireceğiz 2016).

Turning to “Them,” in defining Erdoğan as the “man of the people/nation” (milletin adamı), AKP sloganeering sounds inclusive and representative but in good populist fashion presupposes a “Them” against whom the people are defined and protected (Aslan Reference Aslan2021). The identity of “Them” in the ruling party’s rhetoric has varied over time due to an intricate and mutually constitutive constellation of shifting threat perceptions and political opportunities. As a key inflection point in these developments, the 2013 Gezi Park protests provide useful insight into the role of gendered discourse in the AKP’s counter-mobilization tactics. As the initially pro-environment demonstrations began to spread into anti-government protests nation-wide, Erdoğan dismissed peaceful demonstrators as “a few hooligans” (Subasi94 2013) but later used more blatantly vilifying terms such as “terrorist” and foreign-sponsored “lobby” saboteur (Hintz Reference Hintz2016). Returning to the subject of Gezi protesters in a party speech in parliament in 2022, Erdoğan repeated a long-debunked claim that “these terrorists and bandits” trashed a mosque with beer cans (Erdoğan ‘camiye Içkiyle Girdiler’ Iddiasını Tekrarladı 2013), stating “They’re like this. They’re rotten. They’re sluts” (#ÖZGÜRÜZ 2022).

That last epithet provides insight into how the AKP’s Us versus Them discourse connects to the gender politics this paper investigates. In the regime’s characterization, women who protest against the government are sexually and therefore morally corrupt. In effect, those who are politically disloyal are also bad people. “They” embody precisely the qualities and behaviors the regime has proscribed, such as alcohol consumption and promiscuity. Another invented example of the AKP’s vilification of Gezi protesters similar to the beer-drinking-and-trashing-a-mosque claim further underscores this point with an explicitly gendered component. According to a narrative circulated in pro-government media, a large group of bare-chested, balaclava-clad men coming from Gezi Park attacked a young, head-scarved wife of an AKP local official waiting for a ferry with a baby carriage. For years after the supposed incident, Erdoğan claimed in multiple speeches that the attackers slapped the woman, beat her to the ground, swore at her, and urinated on her. As though scripting the actions of the ultimate villain against the consummate protagonist for a captive AKP audience, the alleged assault on a young pious mother married to a ruling party official seemed too heinous to be real. Indeed, just as the mosque story was a fabrication, that was the case here as camera footage proved (Sabah, “İşte 52 saniyede Kabataş tacizi” dedi, photoshoplu görsel yayımladı! 2015). These hero versus villain scenes played out in the seemingly innocuous forum of Turkey’s cooking shows, as the week-long face-off between headscarf-wearing, gracious winner Gönül and midriff-baring, sore loser Funda in the summer of 2022 exemplifies, and came infused with prescriptive and proscriptive gender lessons.

Indeed, the full version of the scene outlined above contained in condensed but lively form numerous critiques about women contestants’ appearance, speech, behavior, and life choices that mirror debates in everyday Turkish political discourse. As a reality show contestant, the producer-curated presentation of Funda personifies the type of woman government officials routinely condemn. Members of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) have, for example, publicly chastised women for laughing out loud, challenging authority, dressing immodestly, and even crossing their legs (Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti2016; Korkut and Eslen-Ziya Reference Korkut and Eslen-Ziya2016). Erdoğan’s reference to women anti-government protesters as “sluts” fits neatly here, equating public demonstration of opposition to authority with sexual and moral impropriety (Criminal Complaints Against Erdoğan for Calling Gezi Protesters “Sluts” 2022). Funda’s skin-baring clothing and outspoken behavior map neatly onto the attributes of numerous women whom the ruling party has admonished with the phrase “know your place” (Erdoğan’dan gazeteciye ağır sözler: “Haddini bil edepsiz kadın” 2014). In stark contrast, the behavioral, discursive, and sartorial elements of Gönül uncannily reflect those that AKP members and supporters prescribe for women in speeches extolling Muslim piety, modesty in speech and dress, and homemaker skills (Çavdar and Yaşar Reference Çavdar and Yaşar2019; Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti2016; Korkut and Eslen-Ziya Reference Korkut and Eslen-Ziya2016). The overlap between AKP rhetoric and the Funda–Gönül juxtaposition here is striking. Not every competition episode contains such Manichean dimensions, but I selected this episode from my observation of over 600 hours of cooking shows as illustrative of the wider dynamics of gender politics analyzed in this paper.

Cooking Shows as Gender Edutainment: Concepts and Methods

Having outlined the politics of televised gender construction and the AKP’s vision of its ideal woman above, here I present tools for conceptualizing how the two elements link up onscreen in non-obvious ways via discussions ostensibly about cooking. From the regional provenance of a dish to the national or religious holidays on which specific dishes should be served and fasts should be broken, food and hospitality cultures are packed with norms of appropriate behavior. These norms surrounding who produces which dishes and how, when, and by whom they are consumed are embedded with symbolic meanings that can be politicized and polarized (Aksakal Reference Aksakal2015; Karaosmanoglu Reference Karaosmanoglu2020) and are often highly gendered (Prieto Piastro Reference Prieto Piastro2021). Questions of origin and tradition often overlap with discussions of women’s role in serving the nation as well as serving the family, and thus carry prescriptions for women’s behavior (Mankekar Reference Mankekar2000; Shepherd Reference Laura2012).

I argue the concept of conservative gender edutainment helps us understand how seemingly apolitical dialogue — like a TV host’s tips to moms for keeping their kids entertained while preparing a fast-breaking Ramadan meal, or reality show contestants throwing shade on a fellow competitor for using canned chickpeas in the stew she served them — connects to regime politics. Scholars traditionally conceive of edutainment as fun and engaging cultural products that provide instruction in academic or civic subjects to “players,” as much of the early literature on the concept focused on language and video games (Dondlinger Reference Dondlinger2007; Squire Reference Squire2005). Edutainment materials achieve their goal of imparting lessons by keeping the user engaged, entertained, and thus more open to the materials’ messaging for longer periods of time with a higher degree of focus. Applying concept of edutainment to television, we understand how information presented by lively hosts on relatable topics in a visually stimulating environment can keep viewers watching.

Importantly for this study on regime-led gender construction, producers and content-creators believe televised content can help audiences “absorb” the messages provided (Kocamaner Reference Kocamaner2017, 689). Unlike explicitly didactic shows seeking to provide religious education (Özçetin Reference Özçetin2019), humor-filled daytime talk shows (Burul and Eslen-Ziya Reference Burul and Eslen-Ziya2018) and drama-creating competition shows (Sayan-Cengiz Reference Sayan-Cengiz2020) can impart lessons that are more permanent as well as more easily and favorably recalled (Aksakal Reference Aksakal2015). In addition to memorizable facts, edutainment materials can also be effective in shaping feelings and attitudes toward the subject of focus (Argan, Sever, and Argan Reference Argan, Sever and Argan2009). In the food television context, these could range from strong feelings about adding cheese to a seafood dish to normative guidelines for raising children. Finally, as celebrity chef scholar Signe Rousseau demonstrates, media consumers increasingly rely on celebrity figures as sources of knowledge on a range of subjects, particularly given “limitless access to information” and a “bewildering ubiquity of choices” on offer in the digital age (Rousseau Reference Rousseau2013, 139). By virtue of their high-profile as public figures, and well as their (at least purported) culinary expertise, food celebrities serve as ready-made, appealingly packaged epistemic authorities from whom viewers can take pointers, for better or worse (Rousseau Reference Rousseau2013, xxix), on issues in the kitchen and beyond.Footnote 5

In examining how conservative gender edutainment functions in practice, I identify two pedagogies central to the format of two popular types of cooking shows: modeling in host shows and othering in competition shows. Footnote 6 Modeling — defined here as the prescription of particular beliefs, values, qualities, and behaviors deemed appropriate by the regime — is embodied in the format of host shows, a subgenre of food television in which an engaging host in a studio designed to look like a home kitchen provides lively commentary while walking step-by-step through recipe preparation. These hosts’ conversational mode of conveying lifestyle tips through personal anecdotes normalizes as natural gendered behaviors and qualities that are in fact highly contested. In contrast, othering — defined here as the ostracization and vilification of those who display regime-proscribed qualities and behaviors — lies at the heart of competition shows. These types of programs concomitantly present antagonists who deviate from the regime’s idealized woman and clash with protagonists. Producer-curated scenes that juxtapose “villains” with “heroes” allow for comparisons of right and wrong by audiences, particularly when villains meet with unhappy endings like losing a competition. In the somewhat crude form of a televised morality play, the villains receive the comeuppance the audience desires, while viewers receive edification for their own behavior in an entertaining manner.

To unpack the prescriptive and proscriptive gender content of these two types of shows, I apply a mixed-methods approach that includes quantitative content analysis, intertextual analysis of symbols and discourse, and interviews. I first use quantitative analysis to contrast levels of conservative gender norm content across three high-ranked host shows and three competition shows. This analysis serves to test the argument that host shows instruct by modeling behavior for “Us,” whereas competition shows instruct via othering — by vaunting “Us” and vilifying “Them.” I then apply intertextual analysis, which allows researchers to extract various internally coherent themes that emerge across a large body of texts from multiple actors (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992), to a separate set of 15 randomly selected episodes from three of the most popular host shows, all starring food personality Nursel Ergin. This form of critical discourse analysis is particularly suited to studying how multimodal forms of discourse, such as audiovisual content, speak to each other by specifying common modes, methods, symbols, and themes across a wide corpus (Hart Reference Hart2017). Intertextual analysis also aids in identifying whether, when, and how these communicative factors transform — such as a TV host’s appearance, as discussed below (Henke Reference Henke2024). Using this method, I extract norms of behavior for the “ideal female citizen” that coalesce thematically, enabling me to identify how themes present in mass media content map onto discourse used by political elites. Interviews with 22 experts and practitioners in media and culinary industries serve to undergird the claims made about the politicization of media made here, while my viewing of over 600 hours of Turkish cooking show content between 2012 and 2024 provides support that the themes I extracted from randomly selected episodes represent broader content trends. My positionality as a scholar who previously trained as a pastry chef and worked in the restaurant industry for more than a decade created common ground that facilitated these interviews. My work in the food industry also led me to be an avid viewer of cooking shows produced in numerous international settings. Decades of viewing this type of content serve to tune me in not only to variations in ingredients and cooking methods, but also to performative techniques used to enhance audience appeal when discussing food’s meanings, preparation methods, and forms of service and hospitality.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that this paper’s examination of media-based tools of gender construction does not extend to testing the effects of these tools. Media anthropologists and sociologists such as Abu-Lughod and Hall rightly note that television’s messages are framed, inflected, and decoded in diverse ways by audiences based on multi-level factors that confound any “hypodermic needle” transmission effects and thus complicate assessments of how messages “land” (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2008; Hall Reference Hall2007). However, as ethnographic research on the production of Islamic-themed TV talk shows in Turkey demonstrates, creative teams on set often act as if their content were indeed being directly transmitted to, and “normalized” by, viewers (Kocamaner Reference Kocamaner2017, 689). This paper places focus on that content and on its mechanisms of delivery — here, pedagogies, to capture their instructional aesthetic — rather than on its receipt. As a first cut at 1) conceptualizing conservative gender edutainment and 2) identifying the regime-aligned gender construction properties of cooking shows as a well-suited genre, this paper thus delimits its scope to “how possible” rather than “to what extent” questions. An important next step in conservative gender edutainment research could be to test for any links between exposure to cooking shows and regime-aligned attitudinal and behavioral changes among viewers — using audience reception approaches, for example, and data from focus groups, participant observation, or survey experiments (Briandana and Azmawati Reference Briandana and Azmawati2020; Mattingly and Yao Reference Mattingly and Yao2022; Morley Reference Morley2013).

Constructing the Ideal Woman in New Turkey: Two Pedagogies

Assessing Contrasts in Content Dissemination Mechanisms Across Show Types

Identifying symbolic and discursive variation in the content of individuals’ TV appearances can provide useful insight into which types of women’s behavior are deemed worthy of viewer praise and financial reward. Using quantitative content analysis helps provide further insight into this variation, while also demonstrating how the instructional mechanisms of gender edutainment function differently across show format. In this section, studying variation in references to conservative gender norms across host and competition shows underscores the two different pedagogies by which studio and competition shows engage in gender edutainment. As a cultivation platform for modeling behavioral lessons to audiences through conversationally presented tips and recommendations, I expected host shows to have higher levels of conservative gender norm content than competition shows. In the latter type of show, the range of characteristics and behaviors on display for viewers to laud and lambast means that a smaller share of the discursive content will embody the gender norms prescribed by the AKP.

To analyze these contrasts, t-tests were used to evaluate the presence of conservative gender-norm signifiers across three shows of each type with a total of 24 episodes aired between 2020 and 2022.Footnote 7 As no lexicon of conservative gender-norm signifiers in Turkish existed to my knowledge, I created a codebook based on previous viewing of Turkish cooking programs that included over 50 hours of daytime programming in 2022 and a personal history of watching such shows beginning with fieldwork in Ankara in 2012. I selected terms for the codebook in consultation with native Turkish-speaking research assistants, and discussed the contextual and general meanings of identified Turkish words and phrases as signifiers. This was a reflective and iterative process and also helped ensure a high level of intercoder reliability. Python was then used to map the use of signifiers in transcripts generated from YouTube videos. The variation in use of gender norm signifiers across the two types of shows is statistically significant (T(22) value = 7.3785, p value < 0.0001), providing supportive evidence for my investigation into two contrasting gender pedagogies in Turkish cooking programs.

In line with the AKP’s behavioral prescription for women discussed above, the conservative gender-norm signifiers in the codebook include religious references. Breaking down the variation of some of these terms, we see that “dua” (prayer) appears 19 times (presented here as “19x”) in the host shows examined versus 5x in the competition shows studied; “ayet” (Quran verse) appears 10x versus 2x; and “iftar” (fast-breaking Ramadan meal) appears 44x versus 3x. In addition to more frequent reference to specific Islamic practices, the dialogue of host shows’ participants also contains more frequent conversational expressions incorporating the word “allah” (God), such as “vallahi” (I swear, 377x versus 198x) and “inşallah” (God willing, 246x versus 63x). Notably, whereas many of these terms are used causally in the Turkish language by non-pious people — inşallah often stands in roughly for “let’s hope,” for example — their much higher frequency in host shows suggests at least that a difference between participants’ language usage exists across the two types of shows. Perhaps more tellingly, the less causally-used phrase “Bismillah” (in the name of God), which one of Nursel Ergin’s guests instructs viewers to utter before beginning any cooking task (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 42), appears 24x in host shows and 5x in competition shows.

Importantly, variation in conservative gender-norm signifiers is not confined to religious references, as a second t-test separating out gender and religious references in the same set of shows confirmed. The phrase “çocuk annesi” (mother) appears 60x in host shows versus 10x in competition shows; “ev hanımı” (housewife) appears 24x versus 2x; and “kız” (girl, which refers to a female child, but also functions diminutively as a patriarchal reference connoting women in need of protection) appears 209x versus 89x. This markedly higher frequency of content referencing women in the roles of mother, wife, and protected object in host shows versus competition shows suggests that the former instruct viewers by disseminating content for Us. This role prescription is supported by the intertextual analysis presented below. In contrast, competition shows’ more diverse casting and their zero-sum, deliberately contentious format instructs not only by providing positive examples for viewers to praise but by encouraging viewers to judge and otherize contestants who do not conform to regime-articulated gender norms.

Host Shows: Modeling

Host shows have a regular TV personality who serves as instructor and take place either in a guest’s actual home kitchen or on a stage designed to look like a kitchen in someone’s home. The host is typically an engaging and relatable female home cook — male TV hosts are generally acclaimed professional chefs (Interview 18 August 2022) — whose conversational discourse models conservative behavioral norms viewers can absorb and replicate in their daily lives. Host shows have day-time slots and programming content, which implies that their viewers are largely women who do not work outside of the home. The content of advertising aired during these programs also suggests a gendered audience. Ads center around products for cooking, childcare, and housekeeping, and their frequent back-to-back repetition suggests a viewer who may have the television on in the background while engaging in housework.Footnote 8

Host shows’ behavioral prescriptions come in the form of lifestyle tips that hosts sprinkle into their conversation, often using personal anecdotes. These tips serve as a “storytelling” technique that enables the host to appear relatable to viewers and keep them engaged while a dish is cooking (Matwick and Matwick Reference Keri and Kelsi2014). In the AKP’s New Turkey context, gendered tips extend from wife and mother roles to women’s observation of Islam in family life. Pious Muslim cookbook author and TV host Emine Beder, for example, recommended in her show Kitchen Love (Mutfak Aşkı) that viewers consume halal food, replace wine with apple cider vinegar in their recipes, and use rose or basil syrup to ease discomfort experienced following a fast-breaking meal during Ramadan (Emre Cetin Reference Emre Cetin2017). Beder’s conservative clothing and Islamic head-covering, the references to the Quran that pepper her cookery lessons, and her frequent focus on Ottoman cuisine served as instructional conduits. Her show was broadcast on Beyaz TV, a conservative channel owned by the son of a former AKP mayor of Ankara.

Beder’s identity as a veiled TV host made her exceptional when her show aired between 2012 and 2014 (Emre Cetin Reference Emre Cetin2017, 466). In subsequent years as the AKP consolidated its hold over the media, televised media representations of head-scarved women have increased, spreading to more mainstream channels (e.g., Nermin Gül in Misafirim Var, I Have a Guest, 2018). At the same time, the lifestyle lessons she modeled have become increasingly part of the programming content of shows hosted by non-veiled women. Conversational recommendations for conservative gender norms prescribed in AKP discourse now dominate the content of mainstream daytime programming and are offered by women whose appearance and personal histories do not “fit the government-promoted image” (Burul and Eslen-Ziya Reference Burul and Eslen-Ziya2018, 190; Nüfusçu and Yilmaz Reference Nüfusçu and Yilmaz2012). Yet the great majority of these shows with “non-traditional” hosts air on channels owned by holding companies with political and financial ties to the AKP that allow the government to exercise control over content (see data on 78 shows in Appendix 1); each of the shows headed by the popular TV personality studied below, Nursel Ergin, fits this mold. See Figure 1 below.

The host shows I examine using intertextual analysis provide insight into how this seeming contradiction between appearance and instructional messaging functions.Footnote 9 In examining content from 15 episodes of three different TV cooking programs aired between 2012 and 2019, it is readily apparent that divorced host Ergin does not cover her hair with an Islamic headscarf or wear modest clothing; to the contrary, she often wears slim-fitting, tea-length dresses that occasionally expose her shoulders. However, whereas in earlier programs, Ergin resembles American food TV celebrity Rachael Ray, with a “girl-next-door look” and down-to-earth personality similar to those with which Ray branded herself (Rousseau Reference Rousseau2013, xiii), she later adopted a more coiffed, beautified appearance that aligns with anthropologist Claudia Liebelt’s insight that “investments in feminine beauty are closely linked with imaginations of proper womanhood” in Turkey (Reference Liebelt2023, 110). Although not all aspects of her life and lifestyle adhere to the traditional AKP family norms — Ergin announced her second divorce in June 2023 (Nursel Ergin’den boşanma açıklaması 2023) — or more modest styles of dress and veiling displayed by the wives of leading AKP figures, the tips she provides and the subject matter she discusses with her guests do.

From data collected across 15 randomly selected episodes from three different Ergin-hosted programs, chosen for these shows’ high viewer ratings, I found prescribed gender norm content coalescing around five main themes: motherhood, marital/in-law relations, religious practices, kitchen and household duties, and physical appearance and dress. Through her conversational tips and “life-hacks” as host, Ergin provides viewers with advice on how wives can keep their husbands happy and familial relations amicable by asking cantankerous mothers-in-law for their favorite recipes (Nursel’le Evin Tadı, episode 116), and how Muslims can find the direction to pray toward Mecca (kıble) when visiting a friend’s house by figuring out which direction the sea is, rather than admitting they do not know (Nursel’le Evin Tadı, episode 6). She praises meticulously clean kitchens as those “of a woman’s dreams” (Mutfağım, episode 63), admires women who sew their own clothes (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 21), casts aspersions on the use of pre-prepared foods as time-savers (Mutfağım, episode 3), and advises women to learn to make multiple dishes quickly in case guests arrive unexpectedly (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 5).

It should be noted that the emphasis on cooking as a woman’s responsibility as a singular prescriptive norm is not at all new in “New” Turkey. Patriarchal norms prescribing traditional gendered tasks for women like household duties had persisted in many spaces before the AKP came to power. Founding father and first president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk famously declared “any nation that sets women back will fall behind” in emphasizing the importance of women’s legal enfranchisement and education in economic modernization (Kandiyoti and Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti and Kandiyoti1987). However, the state feminism over which he presided — modeling the ideal woman, for example, through Türkiye Güzeli (“Beauty of Turkey”) competitions run by the national newspaper Cumhuriyet beginning in 1929 (Özdemir Reference Özdemir2016; Shissler Reference Shissler2004) — was limited to the secular elite and did not substantially transform societal expectations for women in terms of family responsibilities. As suggested in the introduction, cooking shows provide a useful empirical window onto these expectations. In a special episode on National Sovereignty and Children’s Day, Turkish drama actress and cooking show host Gülriz Sururi asks two young guests: “As girls, are you interested in what goes on in the kitchen? You can’t escape it, you’ll learn this” (Gülriz Sururi’nin Yemek Programında - 23 Nisan 1993 2021). The content that differs strikingly relates to the increased presence of discussions of Islam and Ottoman history in contemporary shows and the absence of any discussion of alcohol — all of which would have seemed markedly out of place in 1993.

In turning to the fifth theme of appearance, Ergin discursively links questions and comments about clothing and personal upkeep to women’s ability to excel in behavioral prescriptions for other themes as well. She asks a female guest who receives a mini-makeover who she will be beautiful for if she does not marry again; later in the episode she shows the same guest a dress and declares: “wear this, become a woman, then we’ll find you a boyfriend” (Nursel’le Evin Tadı, episode 4, emphasis added). The logic goes that appearing feminine and well-groomed (bakımlı) will allow an individual to realize her womanhood, attract a husband, keep him happy in the marriage, and help to produce children. This logic aligns with Liebelt’s findings from her ethnography of the politics of beauty in AKP-era Turkey that efforts toward achieving “feminine beauty are seen as a prerequisite to married life and marriage itself” (2023, 33). Further exemplifying these links, Ergin compliments guests who dress up after cooking to serve a meal to her family (Mutfağım, episode 32). The dialogue echoes prescriptions and proscriptions from a male business community leader interviewed by Liebelt who stated a woman “should dress up nicely, brush her hair, maybe put on some light make-up … it’s not nice if she opens the door to you in her apron, smelling of kitchen … It’s a women’s destiny (kısmet) to look nice!” (cited in Liebelt Reference Liebelt2023, 109). Further linking our themes, Ergin asks each female guest across three shows how many children they have and if they are married, encouraging single mothers to remarry (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 44). She speaks positively of women who work outside the home but emphasizes that she loves women who have multiple talents that cover family as well as household roles (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 21).

Recommendations for conservative, family-oriented behavior in line with Sunni Islam from an engagingly friendly young woman with a glossy ponytail and a swishy dress can help to smooth the government element of the messaging and make those behaviors more digestible to a wider audience. When Ergin calls herself a “persistent student” and smilingly agrees with the instructions of female Sufism expert and repeat guest Cemalnur Sargut on subjects such as how “we” should observe the Muslim Feast of Sacrifice (Kurban Bayramı), her endorsement adds a relatability factor that enables host shows to normalize particular forms of public piety (Nursel’le Evin Tadı, episode 16). When Ergin reacts to a lack of audience questions on the proposed topic of mothers-in-law by saying: “A lot of people wrote us questions about the [2019 municipal] election. Well, I don’t know anything about that. May it all be for the best … May no one fight … May our years pass in peace,” her circumvention deftly guides the discussion away from elections — in which the opposition made stunning gains — and back to women’s familial and household responsibilities that are deeply if not explicitly political (Nursel’in Konukları, episode 21).

Competition Shows: Othering

In contrast to the soothing, cheerful recommendations of host shows, competition shows impart lessons in a much more contentious, indeed combative, format whose drama thrives on vilification. As a Turkish media scholar noted in an interview, reality competition shows in recent years are full of “fighting, debates, and polarization” that can be seen as reflecting wider political struggles in Turkey (Interview 30 June 2022). Because competition shows are less scripted and less explicitly instructional than host shows, they may seem an odd choice for analyzing regimes’ gender edutainment platforms. I include them in this study for three reasons. First, although the dialogue and action in competition shows is more spontaneous, content is still heavily curated and outcomes are largely determined in consultation with production teams that are accountable to ownership structures. This curation means that the decision of which contestants win and/or are portrayed favorably may reflect efforts to appeal to audiences, as well as efforts to portray compliance with prescribed behavioral norms as prizeworthy — or at least praiseworthy. Second, and relatedly, competition shows still contain a strong didactic component despite having a host as a “moderating” (in reality, drama-stoking) figure rather than one who is explicitly instructional.Footnote 10 Particular behaviors are rewarded in the form of compliments and cash prizes for contestants who adhere to regime-friendly norms, while those who do not are otherized via “wounding comments” on-air and online: criticism, insults, and slights that simultaneously create ratings-enhancing drama and reinforce the inappropriateness of deviant behavior (McRobbie Reference McRobbie2004, 106). Finally, including competition shows allows me to examine how two genres of cooking programming function differently as edutainment platforms.

Competition show episodes involve contestants preparing food either simultaneously in a studio staged with multiple cooking stations, or on a rotating basis of hosting other contestants in their own homes. Their casts contain a motley mélange of characters displaying a variety of characteristics such as family status, forms of dress, and word choice that can signify adherence to or deviation from regime-prescribed norms. Thus, from a representation standpoint, competition show casts are more diverse than those of host shows. However, the format of competition shows, which is designed to create drama that draws viewers and thus advertising revenue, pits cast members against each other in scenes that — with substantial producer involvement and even encouragement — produce debates surrounding “proper” characteristics for women such as household skills and respect for/deference to mothers-in-law (Baş and Çebi̇ Reference Baş and Çebi̇2021). Drawing on Butler’s concept of framing moments, (Butler Reference Butler2009) Akınerdem’s study of marriage-themed competition programs notes that such debates, or “normative negotiations” are situated within frames that circumscribe propriety for both contestants and viewers. (Reference Akınerdem2019, 110) Indeed, although ostensibly vying to win a prize for their cooking, much of the dialogue in competition cooking shows (and in viewer comments) centers on evaluating contestants’ gendered comportment. Thus, despite the potential positive social effects of greater diversity in representation, the zero-sum nature of the competition to win a cash prize, along with reality shows’ well-documented penchant for attracting viewers who “love to hate” (Hill Reference Hill2014), combine to create dynamics in which producer-stoked conflict is rife, heroes and villains become evident, and viewers tune in to watch heroes win and villains get their comeuppance. Reality shows are thus ripe for the production and reproduction of stereotypes of various “Others,” as Karniel and Lavie-Dinur illustrate in their study of Palestinian representation in Israeli reality TV shows (Reference Karniel and Lavie-Dinur2011). Discourse among and about idealized Us-type heroes and stereotyped Them-type villains in turn produces teaching moments in which viewers are offered lessons in which characteristics are appropriate for women to embody and display which are not.

From a teaching perspective, sharp — even caricaturized — otherizing contrasts can serve as unambiguous, simplifying behavioral examples for viewers to model or mock (Barthes Reference Barthes1972, 25). Even from the brief introductory vignette with Gönül and Funda, for example, we quickly get a sense not only of the gendered issues at stake but also of who the “good” and “bad” woman is. Our evaluation emerges not only from how these women behave — a woman with a punk aesthetic who vociferously stands her ground could be hailed as a protagonist in a different setting — but, importantly, from the treatment they receive by other contestants and the production team that curates the storyline. As media studies scholars demonstrate, cultural products such as TV series contain communicative elements that serve to define the “good” citizen and the “bad” (Ouellette and Hay 2008) and thus can shape political attitudes (Johnson and Faill Reference Johnson and Faill2015). Entertainment media content offers attitudinal and behavioral blueprints for performing “Us” and evaluating “Them” through their depiction of characters — and in the case of reality TV programming, casts and contestants (Skeggs and Wood Reference Skeggs and Wood2010) — who negotiate ordinary, familiar situations and with whom viewers identify positively or negatively based on characters’ speech, actions, and aesthetics.

Onscreen action in our opening scene from Yemekteyiz offered two Turkish women with strikingly different forms of dress, speech, and behavior. I specifically choose to unpack these women’s interactions as illustrative of reality TV’s polarized tropes and of similar (if not always as neatly binary) dynamics I observed in Turkish competition shows.Footnote 11 On the final day of competition, Gönul’s clothing included a pink headscarf and handmade loose tunic in a pastel flower print, choices traditionally symbolic of piety and domestic femininity, while Funda wore a sleeveless and midriff-baring gold metallic top and had crimped her two-tone dyed hair, displaying a rocker vibe. When Gönül is announced as winner and accepts her prize by stating “God willing I’ll spend it well,” Funda is shown withholding applause (Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz, episode 210). This unsporting and ungenerous behavior recalls the relatively low points she gave to others throughout the week, interpreted by some contestants as evidence of her scheming and self-centered nature. In the end, not only does Funda not win, but she comes in last place.

Audience comments posted on YouTube celebrated Gönül’s win as “the one who deserved it won,” but even more comments reveled in Funda’s loss by pointing to her comportment rather than her food (Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz comments, episode 210).Footnote 12 Of 728 viewer comments posted under the YouTube video of the week’s final episode in which Gönül wins, less than 10 discussed the food. The overwhelming majority were “wounding comments” critiquing Funda’s character, describing her as “horrible,” “unjust,” “cheap,” “toxic,” and “shameful” (Ibid). Those that mentioned Gönül, in stark contrast, praised her for her “noble/well-bred” bearing (Ibid). The amplification of wounding comments by viewers indicates that the show’s onscreen contestation engages audiences, inspiring many viewers to post online content that supports their preferred contestant winner and critiques those they dislike.Footnote 13 Gönül is unanimously praised with language echoing one viewer’s characterization of the victor as a “true lady,” while Funda is unequivocally vilified as, in another viewer’s words, “ugly and sloppy in every way from her appearance to her heart” (Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz comments, episode 210).

Plot twist. Funda was a Yemekteyiz winner in 2021, appearing in the scenes analyzed above as part of a 2022 Yemekteyiz champions’ week. Noteworthy for this paper’s edutainment argument, there is a marked difference in her appearance and comportment across the 2021 and 2022 competitions. In 2021, Funda dressed more elegantly, occasionally baring her shoulders but in pearl-lined dresses with puffy sleeves that conveyed a much more feminine aesthetic in line with the AKP’s vision. She smiled much more, had a more modest demeanor, and became vulnerable by tearing up while telling a family story — all of which were reflected in more positive viewer comments (Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz comments, episode 64). Competition-based reality TV shows are particularly well-suited to both disseminating behaviors of which regimes approve and otherizing those that are regime-deviant. Gönül, whose pious dress and modest speech align perfectly with the AKP’s articulated vision of the ideal woman, comes across clearly as the protagonist, while Funda, whose brash demeanor and revealing clothing in 2022 embody the party’s gendered vision of Them, appears as the villain commentators loved to hate: “if people like Funda participate I’m not watching again” (Zuhal Topal’la Yemekteyiz comments, episode 210). Funda’s appearance and behavior in her 2021 victory, in contrast, could be characterized as regime-compliant, if not ideal.

Final Course, Closing Scene

This paper analyzed two edutainment mechanisms by which cooking shows serve as vernacular yet highly political platforms of gender construction, entertaining viewers while instructing them in behavioral norms prescribed by authoritarian regimes. The multi-method approach used here allows us to extract the gendered content of cooking shows, demonstrate how this content maps onto norms the AKP prescribes for women in New Turkey, and parse out the contrasting ways studio and competition shows disseminate these norms via modeling and othering, respectively.

Although the cultural content is specific to the case of contemporary Turkey, the political function of television programming in engagingly communicating regimes’ gendered Us versus Them rhetoric to viewers is not. The present study can thus serve as a springboard for scholars to examine the identity politics of cooking shows in other cultural and political contexts. Comparative studies of cooking shows could examine questions such as how the political economy of mass media in democratic regimes creates different opportunity structures. In the United States, for example, the popular host show The Pioneer Woman exemplifies very similar content themes, with Islam switched out for Christianity; host Ree Drummond publicly describes herself as: “Wife of cowboy. Mother of five! Lover of butter” (The Pioneer Woman – Recipes, Country Life and Style, Entertainment n.d.). Shows with conservative gender themes like Drummond’s may be on the rise in the US given the second election of Donald Trump. A proliferation of #tradwife (“traditional wife) content TikTok users with millions of followers like Nara Smith, an impeccably coiffed model-turned-housewife-and-mother who cooks meals from scratch while wearing Chanel, suggests (at least the spectacle of) conservative gender content is increasingly popular (Nara Smith (@naraazizasmith) Official | TikTok n.d.).

From a methods perspective, treating cooking shows as a data source opens up a number of fruitful research paths for political scientists. Longitudinal studies could trace shifts in regimes’ identity politics over time using cooking shows as an empirical window, as with the US example. Based on my observation of over 1,000 hours of Turkish cooking shows between 2011 and 2023, there has been a significant increase in the number of head-scarved women, Islamic expert guests, and religious speech references of the type I coded for this project. The lack of access to YouTube-generated transcripts for these shows prior to 2020 complicates quantitative analysis of this shift, but randomizing and hand-coding episodes, in addition to tracing shifts in channel ownership as I do in the Appendix, would prove useful in documenting this trend. Of the 12 MasterChef Türkiye female contestants in 2011, for example, none were head-scarved; of the 11 women who competed in the 2023–24 season, four wore a headscarf. Esra, a head-scarved, well-coiffed mother whose elderly father lives with her, won the competition (MasterChef Esra Tokelli evli mi, kaç çocuğu var? 2024). Here it is important to note that my argument is not that every New Turkey-era participant wearing a headscarf wins or is soft-spoken like Gönül, nor that all women who show their hair lose their competition and are vilified like Funda. Rather, I use that Yemekteyiz vignette as usefully illustrative of a broader trend I observed in which women demonstrating significant adherence to the five conservative gender norms I identified through qualitative analysis are 1) rewarded with praise and, occasionally, prizes; and 2) used as foils for critiquing non-conforming women. Future research could further tease out nuance here.

Moving to the effects of such shows, audience reception studies using focus groups and survey experiments can investigate the extent to which exposure to food television shapes public opinion and political behavior. These methods can also further develop the insights drawn through this paper’s brief analysis of YouTube comments about the emotion-laden phenomenon of viewers loving to “hate on” villains, and the extent to which viewing competition shows contributes to political polarization. Through interviews, scholars of authoritarianism may examine media dynamics of preference falsification (Kuran Reference Kuran1991) — that is, hosts and guests’ onstage “performance” of regime-prescribed behavior that conceals true beliefs, and hidden transcripts (Scott Reference Scott1990) — that is, offstage subversive behavior participants engage in once cameras stop rolling (or once regime-friendly producers are out of earshot). Moving away from traditional television programming, combining digital ethnography of user-generated content by home cooks with interviews can help identify the extent to which platforms such as YouTube offer vloggers any different incentives for curating their performances (Bagdogan Reference Bagdogan2023). Extending Yabancı and Sağlam’s concepts of negotiated conformism (2023), future research can also identify spaces in which cooking show participants exercise agency and subjectivity by creatively using their airtime to insert content in conflict with regime prescriptions to varying degrees (Hintz Reference Hintz2021). The case of host Nursel Ergin’s encouragement that women work outside the home to establish independence — a position likely shaped by her personal experiences as a young single mother, but one that creates tensions with the AKP’s pro-natalist policies — provides a useful place to start (Mutfağım, episode 56; Mutfağım, episode 48).

Acknowledgments

For outstanding research assistance, I am grateful to Ronay Bakan, Sefa Seçen, and Fulya Felicity Türkmen. For extremely valuable feedback, I thank the journal editors and anonymous reviewers, as well as Ateş Altınordu, Senem Aslan, Alexandra Blackman, Alexandra Budabin, Ergin Bulut, Feyda Sayan-Cengiz, Olivia Glombitza, Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Richard Nielsen, Sibel Oktay, Sarah Parkinson, Ertuğrul Polat, Nicola Pratt, and Jenny White. Special thank you to Gamze Çavdar, Yuree Noh, Marwa Shalaby, and other members of the Gender in MENA Politics online workshop, and to Senem Aydın Düzgit and Sabancı University’s Istanbul Policy Center. Finally, I am grateful to all members of my post-earthquake Zoom Writing Group.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1: Dataset of Turkish Cooking Shows Aired 2002–22