2.1 Three Ages of Humanitarianism

Relief efforts during the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, the famine that ravaged Soviet Russia in 1921–3, and the devastating famine in Ethiopia in the mid-1980s are characterised by widely different societal and international circumstances. They represent three distinct phases of humanitarian engagement: the ad hoc humanitarianism of elitist nineteenth-century laissez-faire liberalism, the organised humanitarianism associated with Taylorism and mass society (c. 1900–70), and the expressive humanitarianism brought forth by a mix of post-material values and neo-liberal public–private entrepreneurship that is characteristic of the half century from 1968 to the present.Footnote 1 The years surrounding 1900 and 1970 were incubators of the second and third industrial revolutions; they saw the first and second wave of women’s liberation; and they have been identified as two phases of the twentieth century’s pronounced internationalisation that contributed to the rapid dissemination of new models and practices.Footnote 2

Our cultural and socio-economical approach goes along with the call for a new history of humanitarianism, with greater consideration of economic developments.Footnote 3 It challenges the dominant paradigm of humanitarian studies that selects historical turning points from geopolitical landmarks. We do not claim that all emergency relief follows a dominant pattern of traditional, bureaucratic, or charismatic agency. Ad hoc, organised, and expressive elements of humanitarianism coexist and interact with each other at all times. While not mutually exclusive, time-bound humanitarian models set standards and exert pressure on the sector as a whole.

The characterisation of our first two periods as ad hoc humanitarianism and organised humanitarianism is derived from Merle Curti’s classic study American Philanthropy Abroad, although Curti did not give these names to the eras he described.Footnote 4 The term organised humanitarianism also reflects the proliferation of ‘organisation’ as a dominant principle in the early twentieth century. This surfaces in contemporary social democratic theorist Rudolf Hilferding’s notion of ‘organised capitalism’ and in the aspirations of the internationalist movement of the time.Footnote 5 The concept of ‘expressive humanitarianism’ that we propose pertains to post-material self-expressiveness and to an increasing fusion of relief with advocacy strategies and the notion of rights, media-driven spectacle, commercial branding, popular involvement and populism, ‘projectification’, and the aggressive pursuit of humanitarian intervention. These tendencies emerge from what leading sociologists, economic analysts, and contemporary historians have identified as a caesura around 1970 that was formative for the society of our time.Footnote 6 In contrast to the beginning of the twentieth century, when ‘organisation’ was a prominent term in humanitarian discourse, the terms ‘ad hoc’ and ‘expressive’ are solely analytical rather than being directly derived from our sources.

Our outline of humanitarianism seeks to address levels of transatlantic history that are deeper than such eventful years as 1918, 1945, and 1989, on which contemporary observers have tended to focus. We also deviate from such geopolitically determined perspectives as that of Michael Barnett’s Empire of Humanity, the most comprehensive historical synthesis to date of humanitarian action. Barnett’s study, while representing a mature judgement, is characterised by a US bias and lacks historical perspective.Footnote 7 Moreover, it utilises a highly problematic periodisation and several terminological idiosyncrasies (development becomes ‘alchemy’, for example). In our view, the epoch Barnett describes as ‘imperial humanitarianism’ is an inadequate catch-all characterisation of the field prior to decolonisation in 1945. His subsequent ‘neo-humanitarianism’ is an offshoot of neocolonialism with a tautological ring, and ‘liberal humanitarianism’ conveys a misleading picture of developments after the Cold War.Footnote 8 Barnett’s three categories further imply a progressive trajectory of voluntary action, when in fact many practitioners and observers oppose the increasing exploitation and manipulation of humanitarian efforts by governments and quasi-imperial coalitions. Moreover, the author’s belief that only after the Cold War could humanitarianism overcome a ‘quaintly and stubbornly pre-modern’ condition in favour of a bureaucratised and professionalised approach underestimates the rationalisation of this sector in the first half of the twentieth century, the dysfunctional tendencies of current media- and donor-driven efforts, and the enduring parochialism of US agency in world affairs.Footnote 9

Silvia Salvatici’s recently published A History of Humanitarianism is a valuable overview. She does not attempt to identify an ‘age of origins’, adopting instead what she calls an archaeological approach to investigate the evolution of humanitarianism from the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 until the mid-ninteeeth century. This is followed by a war-related period that lasts for a hundred years, 1854–1951. However, her Third World–oriented period from the 1950s to 1989 was also a time of war and blends official development aid and emergency relief. An epilogue describing the complex emergencies and growth of the humanitarian sector after 1989 follows the dominant political science narrative without adding insights from empirical research.Footnote 10

Chronology of Humanitarianism

Charity is part of a global heritage that acquired a new quality following the social, religious, and economic transformations in Britain during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A crucial factor in this reshaping was the Protestant revival with its activism and incorporation of benevolent traditions like those of the Quakers.Footnote 11 Domestic charity, advocacy and reform of prisons and the slave trade, and aid to foreign countries were closely intertwined.Footnote 12 All this was preconditioned by the rise of capitalism and was shaped, in Thomas L. Haskell’s analysis, by ‘the power of market discipline to inculcate altered perceptions of causation in human affairs’, which yielded a new scope of agency upon others.Footnote 13 Distant charity likewise emerged from the bonds forged alongside European colonial expansion. While local efforts dominated disaster relief in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Atlantic world, religious groups in particular would sometimes raise money for distressed coreligionists abroad. By the second half of the eighteenth century, voluntary overseas aid began to play an increasing role in disaster recovery in the Anglo-Atlantic space. This development was facilitated by the introduction of private subscriptions as fundraising instruments. Rather than relying on government approval or religious edict, these depended on the work of an engaged committee, a media-oriented campaign, and public meetings in coffeehouses and taverns.Footnote 14 Although imperial direction shaped humanitarian efforts, the claim that eighteenth-century donors of transnational relief generally ‘sought to further hegemonic aims’ and that ‘they offered aid paternalistically in order to strengthen their grip on a devastated region and its people’ overlooks the great variety of motivations and anticipated returns.Footnote 15

The US declaration of independence from Britain unsettled prevailing charitable practices, but it also contributed to expanding the imperial horizon of relief efforts.Footnote 16 By the beginning of the nineteenth century, relief campaigns in support of foreign lands in distress became more common. Driven by well-integrated immigrant groups and the evangelical circles that were also engaged in the struggle against the slave trade, Britain during the Napoleonic wars conducted a non-military aid campaign that benefitted various German and Austrian lands as well as Sweden. The fundraising was in response to reports of distress caused by the war and word of an anticipated or actual famine. Suffering populations in enemy states as well as allies were aided.Footnote 17

A striking feature of nineteenth-century humanitarian relief was the ad hoc nature of its organisation and perspective. While relief committees responded to specific crises in accordance with established patterns, the same committees dissolved when they considered their work done, but sometimes reconvened when a similar crisis arose.Footnote 18 Relief consisted of taking emergency measures on top of those by local donors and governments, rather than creating structural interventions that would improve the long-term resilience of beneficiaries. Foreign countries were seen as responsible for the maintenance of their own charitable institutions and economic development, while transnational relief was reserved for the selective alleviation of extraordinary disasters. This led to tension between donors calling for an immediate appropriation of funds and recipient committees abroad who wanted to preside over long-term charitable investments.Footnote 19 However, early transitional groups laid the foundation for more enduring organisations such as the Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP) in the 1840s and the Red Cross in the 1860s.Footnote 20

The 1890s have been identified as a ‘fruitful time for the development of humanitarian practices’.Footnote 21 It was the beginning of a decades-long transformation in an era described as ‘progressive’ in US history, and it involved physicians, social workers, engineers, and later public relations specialists and accountants, all of whom promoted scientific and technological innovations, new media, and modern business practices. An expansive humanitarian vigour surfaced for what may have been the first time in the merging of Protestant missionary zeal and liberal civilisational aspirations during the Russian Famine of 1890–1, when a reluctant US government agreed to lend logistical support to relief efforts. In the USA, the last decade of the nineteenth century is widely seen as a period of transition from a ‘non-interventionist tradition’ to ‘missionary humanitarianism’.Footnote 22

Curti’s periodisation emphasises the correlation of voluntary and government action and the institutionalisation of relief, both of which became manifest in the run-up to the Spanish–American War of 1898. According to Curti, the bureaucratic-rational and semi-official approach of the American Red Cross (ARC) marginalised earlier voluntary relief efforts. The advancement of organisational structures, mass appeals, and government intervention revolutionised humanitarian action.Footnote 23 Over the following decade, the ARC was transformed into the professional operation it is today.Footnote 24

Ian Tyrrell calls attention to the networked culture of humanitarianism that emerged ‘through the historical experience of organized giving’ in response to the remote calamities of the 1890s. He also points to the gradual displacement of idiosyncratic human interest endeavours by the more systematic work of foundations, which contributed greatly to the emergence of philanthropy as a coherent epistemic field and community in the decade after 1900.Footnote 25 For British India, Georgina Brewis has traced the transition from religious philanthropy to organised social service in famine relief efforts during the closing years of the nineteenth century.Footnote 26 Pre-war imperialism, as a recent study concludes, had a profound impact on British humanitarianism after the First World War. It affected the entire humanitarian sector, from the ‘ethics of relief’ to aid practice and staffing. Administrators and relief workers with experience from colonial institutions, missionary groups, or the Society of Friends remained an essential part of the ‘mixed economy’ of voluntary and official aid during the interwar years. Thus, newly established organisations like the Save the Children Fund (SCF) or the American Relief Administration (ARA) ‘utilized the expert knowledge and techniques of famine relief first elaborated by the liberal imperialism of the late nineteenth century’.Footnote 27

Such developments coincided with the first wave of women’s liberation, leading to the ‘feminisation of relief work’ in the first two decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 28 However, despite this new feminised public image of aid work (such as in Red Cross advertisements), and despite the emergence of ‘feminine’ organisations like the SCF and the prominent role of female fieldworkers in Quaker relief, men still dominated the humanitarian arena, and in some cases denied access to women and disputed their capability of conducting humanitarian field work.Footnote 29 At the same time, as victims, women continued to benefit from idealised notions of motherhood or paternalistic chivalry towards the ‘fair sex’. While we know about the contributions of women in the early ad hoc campaigns (including the anti-slavery movement and philhellenism), much remains to be learned about female leadership, mobilisation, activism,Footnote 30 and negative and positive discrimination in humanitarian efforts.

Photographs came into wider use in the fundraising campaigns for India (1896–7) and the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and onwards, creating an enhanced sense of the authenticity of aid causes in an unholy alliance ‘with the sensationalistic mass culture that intensified after the turn of the century’.Footnote 31 While children had played a special role in philanthropic campaigns since the Enlightenment, the twentieth century placed increased emphasis on the suffering of children.Footnote 32 As a group, children required extensive relief administration because self-help programmes were inappropriate for them. Since the South African War of 1899–1902, sympathy towards enemy children has also served as a way to oppose war.Footnote 33 The First World War and the period of political and economic instability that followed, with its collapsing empires, civil and border hostilities, expulsions, and waves of refugees, created a vast humanitarian crisis. The war became a node for organised humanitarianism that displaced ad hoc charity efforts.Footnote 34 However, the rise of international and humanitarian organisations after 1918 only resumed an ongoing trend that the war had interrupted.Footnote 35

The present study concurs with Johannes Paulmann’s claim that the Second World War was not the watershed in the history of humanitarian action that it is proclaimed to be by Curti, Barnett, and many others, since the ideas and procedures that marked this period drew strongly on previous developments.Footnote 36 Paulmann proposes the late 1960s and early 1970s as a turning point, and some academics agree.Footnote 37 At that time, decolonisation had decoupled ‘caring’ from direct forms of ‘ruling’,Footnote 38 and modern identity politics, including the second generation of feminists, had its breakthrough. The international relief effort for Biafra (1967–70) is widely recognised as a rupture in the history of humanitarianism. It effected a split in the Red Cross movement with the formation of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), moulded a generation of relief workers, and brought civil society organisations to centre stage as mediators between Western audiences and the ‘Third World’.Footnote 39

The truism that the end of the Cold War transformed the world has led many to assume that a new period of humanitarianism began after 1989. Researchers do not conceive the new global order as a consequence of previous developments in Western society with which the Soviet bloc was unable to compete. However, there is little evidence of a major shift in the culture of humanitarianism that parallels the geopolitical change. Paulmann does not answer the question of whether we have witnessed ‘a new departure’, or merely an emphasis on emergency aid in places where sovereignty has broken down and aid has been implemented to contain conflicts at low cost. With reference to our time, Paulmann cites satellite transmissions and the BBC report on famine in Ethiopia that resulted in the Live Aid benefit concert in 1985 – events predating the end of the Cold War.Footnote 40 He also questions the significance of the geopolitical shift of 1989 for humanitarian ‘so-called complexities’.Footnote 41 Similarly, Monika Krause emphasises a major shift in terms of symbolic differentiation in the humanitarian sector with the founding of MSF in 1971 and suggests another shift by the end of the Cold War. However, her account makes MSF appear to be the creator of contemporary humanitarianism, while the period commencing in 1989 is mainly characterised by expansion of the basic trend.Footnote 42

Lilie Chouliaraki, who contrasts examples from the 1970s and 1980s with those of recent years, labels the entire period from the 1970s forwards as an ‘age of global spectacle’ typified by three transformations: (a) the market-compliant instrumentalisation of aid, (b) the decline of the grand narrative of solidarity, and (c) the technologically fuelled rise of self-expressive spectatorship. Taken together, she suggests that they effect an epistemic shift towards an emotional, subjective humanitarianism correlated to narcissistic morality and an emergent ‘neoliberal lifestyle of “feel good” altruism’.Footnote 43 Similarly, Mark Duffield contrasts the 1970s and the present, but ultimately suggests that the decline of modern humanitarianism and the ‘anthropocentric turn’ brought about by its postmodern variant can be traced to the Biafran War.Footnote 44 At the same time, powerful tools of results-based management were introduced in the humanitarian sector that shifted the emphasis from overarching societal to project-specific goals.Footnote 45 Our concept of expressive humanitarianism encapsulates these trends, which are also summarised in Alain Finkielkraut’s formula of the ‘sentimental alienation’ that has characterised humanitarian efforts in the past half-century.Footnote 46

A focus on major emergencies with established systems of humanitarian response, rather than key turning points, has guided the selection of our three case studies. Our interest concerns humanitarian action, not the disaster as such. For example, the death toll of the Soviet Famine of the 1920s was exceeded by that of the Ukrainian Holodomor of the 1930s and the famine accompanying China’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ (1959–61); but while the disaster of the 1920s became a major instance of transnational aid, in the Holdomor and the Chinese cases, there was domestic neglect of the emergency and they failed to attract much international attention.Footnote 47

In order to examine how the relief efforts of governmental, intergovernmental, and voluntary groups unfolded in the context of their time, we turn to overviews of the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, the Soviet Famine of 1921–3, and the famine in Ethiopia of 1984–6.

2.2 The Great Irish Famine and Ad Hoc Humanitarianism

The characteristics cited in Curti’s identification of nineteenth-century ad hoc humanitarianism were (a) the lack of formal and institutional connections between different relief efforts; (b) the marked stress on voluntary initiatives; and (c) the reliance on a fundraising repertoire that in the USA had emerged from the philhellenic movement of the 1820s. Included in these were the formation of committees for the collection of money and the transportation of foodstuffs (often linked to economic boards), public meetings, church fund drives, charity events, ladies’ bazaars, and ultimately newspaper campaigns.Footnote 48 In the UK, building upon the long-distance imperial charity of the eighteenth century, ad hoc humanitarianism had already emerged during the Napoleonic era. Despite the war context, foreign relief was an entirely civilian endeavour at the time, with links to the British and Foreign Bible Society, the evangelical and anti-slavery movement, and domestic charity.Footnote 49 In the 1820s, engagement with the Greek struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire became an exemplary international aid campaign based in several countries, although military emphasis prevailed in this early instance of ‘humanitarian intervention’, and providing relief to distressed civilians remained a subordinate goal.Footnote 50 In addition to Curti’s points, the repertoire of ad hoc humanitarianism included committee rules and procedures for the documentation of subscriptions and disbursements. However, there were no agencies active in monitoring food insecurity or other disasters, nor was there any permanent infrastructure for fundraising or aid distribution. Governments were also unprepared to manage foreign aid.

In Ireland, where famines had occurred periodically, the first significant British relief effort took place in 1822, when funds for that country were solicited by a London Tavern Committee. Collections from other British cities soon followed, and the Dublin relief committee even expressed its thanks for North American and French aid. The Irish cause included a Catholic newspaper in Paris among its supporters in 1831.Footnote 51 Some activists and donors from those years, even philhellenic veterans, later participated in relief efforts during the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s. Donors of the 1840s in turn subscribed in later years to similar campaigns, such as the Finnish famines of 1856/7 and 1867/8.Footnote 52

Despite these compassionate forces, the ‘hungry forties’ represented a difficult time for transnational relief. Europe was experiencing bad harvests, an economic downturn, and political unrest.Footnote 53 In such an environment, individual and collective action typically parted ways, as local moral economies easily clashed with larger ones. Thus, although Pope Pius IX and Sultan Abdulmejid I contributed to the Irish plight in 1847, both the Vatican State and the Ottoman Empire banned the export of grain in the face of domestic scarcity and disturbances.Footnote 54 During Easter of that year, the pope spent three times the amount he had given towards Irish relief to buy bread for poor families in Rome.Footnote 55 In France, relief efforts for Ireland only took on significant proportions when the winter was over and there was no longer fear of domestic food hardship, despite the knowledge that ‘while one suffers in France, one dies in Ireland’.Footnote 56 Disaffection with the Age of Metternich, culminating in the revolutions of 1848 (among the consequences of which were an exiled pope and a crushed Irish rebellion), minimised the concern of European elites with the Irish disaster.

In contrast to the view presented by earlier research, Ireland experienced the greatest surge of food riots in its history during the Great Famine. While they coincided with agrarian protests and hunger-induced crime more than previously, and while the authorities treated them as an ‘outrage’ and an act of ‘plundering provisions’ that had to be countered by force, a distinct Irish moral economy, similar to the English equivalent described by Thompson, was still at work.Footnote 57

Meanwhile, conditions for providing famine relief were good in the USA in 1847. A populous Irish community that was in close touch with their homeland already existed. Irish-American organisations became the nucleus for broader civic engagement and a nationwide campaign. At the same time, plentiful US harvests enabled great profits in undersupplied European markets, facilitating generosity and giving rise to the notion of a moral obligation to compensate those who suffered most under the anomalous terms of trade. Moreover, concurrent opposition to US aggression against Mexico inclined many people towards humanitarian action. The provision of famine relief for Ireland was a show of peaceful intent that allowed concerned US citizens to maintain their moral self-respect. By contrast, nativist resentment and anxiety over the prospect of paupers immigrating to the USA eventually constrained charitable giving.

UK Relief

Conditions within the UK played a special role in Irish relief. This was true from the beginning of the famine in autumn 1845, when Ireland lost nearly half its potato crop, through peaks after the nearly complete potato failures of 1846 and 1848, until its gradual diminution between 1850 and 1852.Footnote 58 The dramatic catastrophe resulted from exclusive reliance on a new food crop.Footnote 59 The famine ravaged Ireland in absolute and relative terms. The death toll amounted to approximately one million people, and it caused the emigration of more than a million more men, women, and children out of a population of slightly more than eight million. As a result, the population of Ireland shrank by a quarter in just a few years. However, this does not take regional aggravation, averted births, and long-term physical and psychological damage into account.Footnote 60

Ireland at the time was a formally integrated part of the UK which was the wealthiest polity in the world (despite an economic downturn from 1847 to 1849). The British government was generally considered responsible for safeguarding the welfare of Ireland’s population, although this meant something different in Britain and abroad. The UK administration pursued a hands-off policy, passing financial responsibility on to overtaxed local Irish authorities. As the result of a fierce market logic that did not recognise a country’s inalienable right to subsistence, Ireland was made to export foodstuffs to England while parts of its own population starved to death.Footnote 61 This lack of compassion was primarily due to British resentment towards the Irish and the influence of the evangelically inspired ‘moralist’ faction within the ruling Whig party after 1846. These ultra-liberal moralists, with their strong grip on the treasury and support from the metropolitan press, appropriated a ‘heaven-sent “opportunity” of famine to deconstruct Irish society and rebuild it anew’ along modern capitalist lines.Footnote 62 Ironically, the austere development approach was designed by the heirs of the same evangelical movement that had made up the humanitarian avant-garde at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. While moral rigidity and anxiety lest there be abuse of benevolence were not unique to the Victorian age, the second generation of evangelicals had ‘degenerated into doctrinaire pedantries’ at such a rate that a historian of the movement suggests ‘Frankenstein’s giant creation had got out of all control’.Footnote 63

In hindsight, the Irish famine compromises political economy along the lines of Smith, Malthus, and Mill, as well as confidence in the project of modernity and in the civilisational standard of the British Empire. Ireland represented the ‘other’,Footnote 64 and was routinely addressed as ‘that country’ in the correspondence of British officials at the time. Ireland was treated differently than other parts of the UK, giving Irish–British relations a transnational and colonial character, despite formal participation in the same polity.Footnote 65 Few would go so far as to characterise the British government’s conduct during the famine as genocide, but it is evident that British notions of the inferiority of an Irish ‘surplus population’ let them turn their backs while an unseen hand took the lives of the starving.Footnote 66

The first Irish voluntary organisation for relief, the Mansion House Committee, was established in Dublin in October 1845.Footnote 67 The initial response of the UK government was to accommodate relief appeals, although it adhered to free trade principles and tied relief to the repeal of the Corn Laws. Based on experience with previous food crises, the government installed a relief commission that coordinated and subsidised local committees and voluntary collections, and financed public works. It also secretly purchased maize in the USA to regulate market prices, distributing it to depots throughout Ireland, and eventually selling it to the people. These measures saved the poor from starving to death during the first year of the crisis, but they were decried in the public debate as overly generous and in part regarded as one-time interventions. In Ireland, popular unrest and opposition to its coercive suppression spread, forcing the conservative government of the UK, headed by Sir Robert Peel, to resign in June 1846.Footnote 68

Lord John Russell’s succeeding Whig administration was a weak minority government that was pressured to take a less interventionist course. Despite gravely rising food prices, it refrained from market interference and included penal elements in the public works scheme. This countered benefits to landowners from work projects and introduced performance-based remuneration that pushed the sick and the elderly below the subsistence level. After the almost complete potato failure of 1846, destitution made the number of those engaged in public relief works rise from 114,000 in October 1846 to 714,390 in March 1847. An increasing number of malnourished labourers died on the job. Notwithstanding harsh conditions and the huge number of enrollees, demand for employment in the relief scheme far exceeded availability.Footnote 69

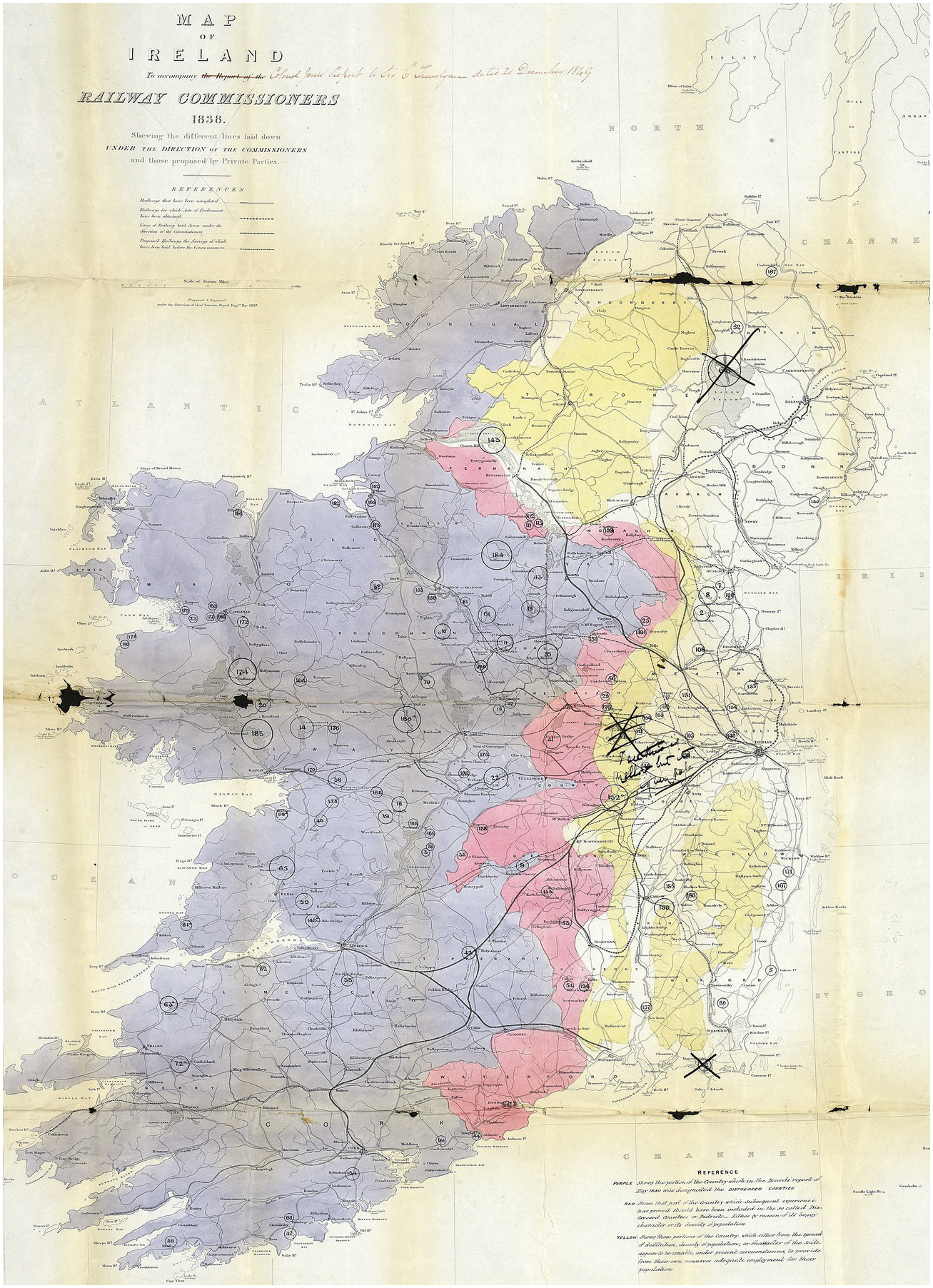

The government abandoned its public works programme by spring 1847. It was apparently ineffective and had become prohibitively expensive. Instead, the government sponsored a network of soup kitchens for the needy in conjunction with the aid being provided by the Quakers. This was a comparatively cheap entitlement-based approach that was intended to operate as a government programme only throughout the summer of 1847. By July, the soup kitchens were feeding three million people on a daily basis. In autumn, the burden of famine relief was written into an extended poor law. From then on, taxpayers in the distressed unions (i.e., ‘poor law’ districts) of Ireland had to bear the cost of the relief they received. A relative improvement in food availability during the second half of 1847 gave the illusion that the famine was over, occasioning the permanent withdrawal of means by the central government.Footnote 70 However, in 1848, blight again destroyed most of the potato crop. In 1848 and 1849, more than one million people were given relief through the extended poor law.Footnote 71 However, inmates of workhouses – the core institution of the Irish Poor Law – made up almost one-third of the victims of the Irish famine.Footnote 72 In all, public expenditures for Irish famine relief was about £10 million, mostly intended as loans.Footnote 73 Figure 2.1 depicts an official, single-copy map drawn in 1849 that uses three colours to highlight different degrees of distress. It shows that the western half of Ireland was affected most and that the government was aware of the suffering.Footnote 74

Figure 2.1 Map of Ireland accompanying Colonel Jones’s report to Sir C. Trevelyan, 21 Dec. 1849, with ‘distressed counties’ coloured.

The voluntary fundraisers during the Great Irish Famine came from varied backgrounds and their inclination to help differed considerably. Their level of activity fluctuated, although in grossly inadequate proportions, with the severity of the distress, efforts by others, and press coverage, and it decreased over time. The first faraway group to provide relief at the end of 1845 was the Irish community of Boston. In early 1846, the British imperial forces in Bengal, which included many Irish soldiers, initiated another long-distance effort. When the famine intensified at the end of that year, some Catholic parishes and proselytising societies in England, as well as Irish organisations in the USA and transnational Quaker networks, began raising funds. The SVP expanded its model of soliciting local Catholic charity in major Irish cities, and also gave some subsidies.Footnote 75

However, before the founding on 1 January 1847 of the British Association for the Relief of Extreme Distress in the Remote Parishes of Ireland and Scotland (or British Relief Association, BRA), transnational activity was low. While this new British initiative was controlled by the financial elite of London, it was directed by the same officials who had previously been responsible for inadequate government relief to Ireland – in particular, Charles Trevelyan, the permanent secretary of the treasury (and second-generation evangelical). In contrast to the communications of the Quakers and various relief efforts abroad, the BRA, following the official language policy, avoided the word ‘famine’ altogether.Footnote 76 Their campaign raised £470,000, mainly in the first months of 1847. More than two-fifths of that sum was the result of the reading of two letters by Queen Victoria in Anglican churches throughout England.Footnote 77 One-sixth of the total fund was reserved for Scotland, where some districts had also suffered from a poor harvest. The £390,000 collected for Ireland, which included donations from various parts of the empire and the wider world, was depicted as a success, although it barely exceeded funds raised during the minor famine of 1822.

Catholic and Foreign Relief

The appearance of a major British campaign encouraged the nascent relief efforts of Irish communities in the USA and Catholics around the world. Thus, a considerable, although short-lived, international voluntary effort came about in 1847, and for some time alleviated Irish distress.

British vicars apostolic (as Catholic bishops were then called) began to issue aid appeals in late 1846, perhaps challenged by the preparations being made to establish the BRA. The Catholic weekly, The Tablet, became the truest trusted conduit of news from Ireland to the British public. It continued to serve famine relief when that cause was no longer fashionable, illustrating the durative power of institutions, even journalistic ones, over individual efforts in raising aid. Catholic bishops as well as other Catholic collectors and donors in Britain generally forwarded gifts to their sister clergy, who constituted the spiritual authority for four-fifths of the Irish population, but they also contributed significant sums to the BRA.Footnote 78

Prompted by Paul Cullen, rector of the Pontifical Irish College, the newly inaugurated Pope Pius IX made a personal donation to the cause of Irish relief and, assimilating an interdenominational relief committee formed by UK citizens in Rome, mandated collections for Ireland in mid-January 1847. By means of an encyclical, he extended the call for famine relief to the greater Catholic world in March 1847. Its impact was most evident in France and Italy, although the encyclical was widely circulated and resulted in contributions from other places as well. Prelates from Italy and elsewhere forwarded offertories of their districts to the Vatican’s Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, which distributed the sums totalling upwards of £10,000 among two dozen Irish bishops and archbishops. French fundraising was also carried out by dioceses, but was ultimately coordinated by the voluntary Comité de secours pour l’Irlande, which conveyed the proceeds of roughly £20,000 to the Irish clergy. The committee’s first action, taken at a time when the pope’s sphere of activity was still limited to Rome, was to ask him to address the world-at-large.Footnote 79

The key figure behind the French petition was Jules Gossin, the president of the SVP, whose role has gone unrecognised in previous research. Gossin’s circular, issued to SVP chapters in February 1847, resulted in funds that helped establish new branches in various Irish cities. These groups and their transnational network transcended the ad hoc humanitarianism of the nineteenth century, although the amount they raised abroad barely exceeded £6,000, and their raison d’être was local charity.Footnote 80 SVP branches continued their work throughout the years of famine, even after external funding had dried up; they are still flourishing today.

The isolated relief initiatives that emerged in the USA by the end of 1846 were coordinated and expanded by a national fundraising meeting that took place in Washington, DC, in February 1847. Contemporary discourse framed US relief efforts as a national enterprise of doing good that transcended ethnic, religious, and party divisions. Researchers have corroborated those claims.Footnote 81 However, individuals and organisations with an Irish background played a crucial role in the relief committees – something that was downplayed at the time in order to appeal to a wider circle of donors. The role of personal ties is also evident when one considers that remittances from Irish people abroad dwarfed humanitarian efforts, even at the height of voluntary action. Such remittances continued to increase in the following years, whereas transnational charity as a manifestation of sympathy ebbed after a few months.Footnote 82 Since the USA was construed as a ‘nation of joiners’, most Catholic fundraisers forwarded their collection to general committees in major cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and New Orleans.Footnote 83

These committees and some of their smaller counterparts chartered ships with relief goods that they sent to Ireland – most famously, Boston’s iconic Jamestown, with a cargo bound for Cork. The UK government reimbursed freight costs across the Atlantic, a subtle move that gave England moral credit in the eyes of the world and co-opted critical opinion in the USA. Nevertheless, US committees maintained their distance from UK authorities and principally relied for the distribution of their foodstuffs on Irish Quakers, who had a sterling reputation of providing impartial relief, rather than entrusting the US cargo to the quasi-governmental BRA. Contributions from the USA totalled approximately £200,000.

Ad Hoc Voluntarism

When in 1847 relief for Ireland was on the global agenda, collections were initiated worldwide. Most significant was the imperial context, in which British, Irish, and confessional backgrounds joined forces. Substantial sums from India, Canada, and Australia were given to the BRA, to Irish relief committees, or to the clergy in Ireland. Catholics in third countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany tended to donate through church channels, whereas the BRA administered most other subscriptions and donations, including Sultan Abdulmejid I’s much-cited contribution of £1,000. Overviews of relief are frequently inflated by sums being counted twice, among other flaws.Footnote 84 The present study estimates that voluntary relief to Ireland during the Great Famine totalled £1.4–1.5 million, of which almost £1 million came from abroad.Footnote 85

By the end of 1846, the British Empire had to demonstrate its goodwill by providing famine relief in the sphere of voluntary action. Meanwhile, the Catholic world could not passively watch as the dominant Protestant society spread its benevolence over the Irish people. In the USA, people of Irish ancestry were crucial in stimulating relief efforts for Ireland, although nationality was often de-emphasised for improved outreach to US citizens who had no prior commitment to Ireland. For the same reason, Catholic churches in the USA, rather than making aid a confessional matter, joined local campaigns that principally channelled donations through Quaker intermediaries. English Catholics similarly maintained a cautious profile, trying to avoid causing their Anglican counterparts to develop a negative attitude towards Irish relief. The SVP chapter in Kilrush, which also distributed aid for the BRA and the Society of Friends, illustrates the local entanglement of foreign aid.Footnote 86

Thus, the Irish Famine of 1847 saw a broad, well-coordinated network of fundraising bodies, aid providers, and local distributors working together on a hitherto unknown scale. Nevertheless, there was no preparedness for a sustained effort. By the summer of 1847, relief committees in the USA and elsewhere began to disband, church bodies turned their attention to other issues, and volunteers who had distributed aid on the ground were exhausted. Famine raged for another three years (five years in some parts of Ireland) with no significant voluntary or official relief efforts. Few people abroad could have imagined that a powerful government as the UK would remain largely passive in view of such an ongoing domestic calamity. When in the autumn of 1847 civil servants declared the situation in Ireland under control, it was widely assumed that this was in fact the case. Thus, almost all efforts ceased after a single season, showing that ad hoc humanitarianism was a weak and unreliable source of aid.

By the mid-nineteenth century, despite the trust in public authorities, a European, trans-Atlantic, imperial disposition to engage in far-reaching humanitarian projects emerged. It qualitatively surpassed the bilateral endeavours of the Napoleonic era and the limited multilateral (chiefly military) philhellenic activism of the 1820s. Anticipating the ‘glocal’ civil society of the twentieth century, the SVP illustrates the potential of charitable structures that are more enduring than the temporary committees of the nineteenth century. While other relief initiatives slackened, the SVP extended its network of auxiliaries throughout Ireland in the latter half of the 1840s. This infrastructure allowed the local middle class to engage with their suffering compatriots and provide a maximum of aid with a minimum of resources.

2.3 The Russian Famine of 1921–3 and Organised Humanitarianism

The famine that began in parts of Soviet Russia in 1921 was preceded by bad harvests, a harsh winter, and a subsequent drought – especially in the Volga Valley (see Figure 2.2). The post-revolutionary country had been ravaged by war and by then had endured seven years of chaos. The methods of war communism, including confiscation and collectivisation, had weakened rural communities, while the White armies were still active in some parts of the country. The New Economic Policy (NEP) adopted in March 1921 did not relieve conditions immediately, and the lack of emergency planning coupled with mismanagement aggravated the situation. Twenty million people were threatened by starvation; an estimated two million eventually died.Footnote 87 Nevertheless, the Bolshevik government would not officially acknowledge the famine or solicit foreign assistance until mid-1921. At that point, the author Maxim Gorky dramatically appealed for aid. His call immediately triggered an international relief campaign for Russia.Footnote 88

Organised Humanitarianism

Historians and contemporary witnesses cite the Russian Famine of 1921–3 as a defining moment in the history of humanitarian aid.Footnote 89 The extensive international relief effort it called forth reflects trends that originated in the years around 1900 and were reinforced, refined, and sometimes redirected during and after the First World War. Those efforts provide a paradigm for what we term organised humanitarianism. The era which saw an increased focus on children, was characterised by (a) the institutionalisation and professionalisation of humanitarian practice, including businesslike fundraising, purchasing, and accounting procedures; (b) the active engagement of experts and the impact of science; (c) a ‘mixed economy’ of voluntary and state efforts; and (d) the systematic use of photographs and motion pictures in fundraising campaigns.

With origins in the late nineteenth century, the model of organised humanitarianism gained considerable momentum at the beginning of the First World War when Herbert Hoover created the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), which would also serve as the blueprint for US relief efforts after the war. Between 1914 and 1919, the CRB managed an aid operation on an unprecedented scale, sustaining an entire nation suffering under German occupation and an allied blockade. A contemporary observer described the CRB as a hybrid ‘piratical state organized for benevolence’.Footnote 90

Hoover’s accomplishment was achieved by skilful diplomacy and recourse to his business and engineering expertise. Commission offices purchased raw materials on the global food market, convoys shipped them across the Atlantic, and thousands of warehouses aided in the distribution. Overhead costs were kept low as the majority of the staff was made up of volunteers; and shipping, insurance, and other companies agreed to offer charitable discounts. Moreover, individual recipients or relief committees were asked to pay for provisions wherever they could. About 80 per cent of the US$900 million at Hoover’s disposal came from governmental sources, primarily via loans from the USA and the UK, and only 6 per cent came in private donations.Footnote 91

After the war, Hoover continued his work with the ARA, first in Central Europe and then during the famine in Soviet Russia. Mainly a government sponsored organisation, the ARA was also supported by tens of thousands of private donors. It spent US$5 billion between the armistice of 1918 and 1924.Footnote 92 The ARA Food Remittance Program, which allowed individuals to purchase food packages worth US$10 for relatives and friends in certain European countries, was a successful creation of the period, and it was also deployed during the Russian Famine.Footnote 93

Motivated more by pragmatic considerations than compassion, the principal post-war US goals were unloading an agricultural surplus, boosting the US economy, and securing future markets. In addition, the ARA and affiliated organisations like the ARC were tools to contain communism and influence the nation- and institution-building process in Central Europe.Footnote 94 More than leaders of relief efforts in former times, the new humanitarians aimed to shape the governance structures of the societies that they were targeting.Footnote 95

The Near East Relief (NER), which emerged in 1919 out of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (founded in 1915), was equally ambitious in its goal of reshaping societies in the Eastern Mediterranean by providing both emergency aid and long-term relief in the form of educational programmes. Its Protestant missionary background caused it to choose Christian children, especially Armenian orphans, as its main beneficiary group.Footnote 96 Limiting its services to a marginalised minority group contrasted with the NER’s intention of raising a generation of decision makers. The NER had close governmental ties, but depended far more than the ARA on private donations and it embraced modern fundraising techniques. Over a period of ten years it spent more than US$100 million to provide relief and ‘help to self-help’ through education and training. As did other representatives of organised humanitarianism, the NER emphasised its own professionalism and efficiency. However, while ‘tales of perfectly executed plans’ dominate its official publications, its work was in many cases based on improvisation.Footnote 97

Whereas the CRB and the ARA were examples of twentieth-century relief efforts that were largely state-financed and partially state-led, the British SCF represented an alternative format of organised voluntary action. It combined humanitarian service with advocacy, and it functioned as a corrective to government policy. Eglantyne Jebb, who co-founded the SCF in 1919, saw her organisation’s role as a counterforce to nationalist politics and consciously chose ‘enemy children’ (first German and Austrian, then Russian) as primary beneficiaries.Footnote 98 Although child-focused charity was familiar in 1919, even greater attention shifted from wounded soldiers to children after the war.Footnote 99 The ARA and affiliated organisations also focused on minors, and the innocent child became an international icon closely linked to appeals for humanitarian relief.Footnote 100

By contrast to the ARA, but like the Quakers, the outspoken SCF goal was ‘to foster a new generation of peace-loving internationalists’.Footnote 101 The SCF’s transnational ambitions were further emphasised by the foundation of the International Save the Children Union (ISCU) in Geneva in 1920. Thus, the SCF combined fundraising and relief with the championing of children’s causes more generally, and by 1924 had brought about the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of the Child by the League of Nations.

The SCF addressed its appeals to the entire population and, despite a generally progressive tendency, it actively recruited patrons and members representing a wide range of political views. In December 1919, Pope Benedict XV announced his support for the SCF, and religious leaders in Great Britain followed. Through its adoption of business methods, the SCF contributed significantly to the professionalisation of the humanitarian sector in the UK. Public relation experts from private firms, hired on a commission basis, designed nationwide advertising campaigns, and Jebb understood the ‘efficiency of controversy’ for voluntary organisations.Footnote 102 The magazine The Record, which began publication in October 1920, functioned as a mouthpiece. The SCF established, or at least popularised, an innovative scheme by which donors symbolically ‘adopted’ children in Austria, Serbia, Germany, Hungary, and other countries, creating long-term bonds. Rooted in the Christian tradition of caretaking godparents, child sponsorship has remained a popular method of humanitarian aid that has special appeal to contributors.Footnote 103

In comparison with the ARA, however, the SCF was a small-scale player. It relied almost entirely on private donations, only addressed children’s issues, and (at least during its early years) passed funding on to other groups rather than organising relief on its own. Despite its relative inexperience and a difficult political environment (‘feeding enemy children’ was far from a popular cause in post-war Britain), its fundraising methods enabled the SCF to collect about £1 million during the first two years of its existence.Footnote 104

American and British Quakers were other groups that played a significant role during the Russian Famine. They had previously set up humanitarian missions during the Russian Famine of the 1890s in the city of Buzuluk, to which they returned in 1916 and 1917, and which became the centre of their famine relief five years later. They were then engaged by both the ARA and the international Red Cross movement to channel relief.Footnote 105 During the First World War, transnational Quaker relief work was professionalised. The British Friends’ Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee (FEWVRC) and the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) were established in 1914 and 1917, respectively. Initially, both organisations cooperated closely.Footnote 106

The Nationalisation of Universal Causes

The growing awareness of global interconnectedness led to the ‘heyday of a vigorous internationalism’ in the early twentieth century that benefitted the humanitarian sector considerably.Footnote 107 However, the war experience also led to the nationalisation of transnational aid. Governments started to coordinate, seek control over, and channel humanitarian efforts from their territory, resulting in limited room for internationalist and pacifist organisations to manoeuvre.Footnote 108 As a consequence, transnational humanitarian efforts were often organised along national, rather than international, lines.Footnote 109 In the case of the Red Cross, the outcome was the juxtaposition of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which had little means but great moral authority, against the financially better-situated national Red Cross societies.Footnote 110 The relationship between the British SCF and its Geneva-based international counterpart, the ISCU, developed in a similar way. In contrast to the conservative Imperial War Relief Fund (IWRF), which emphasised the British and imperial character of its mission and shunned international cooperation, the SCF had encouraged the establishment of national chapters in other countries, a dozen of which emerged by 1921. Competing with the IWRF, the SCF also received substantial donations from the British dominions, principally New Zealand and Canada, where new chapters were forming. However, during the Russian Famine, the SCF put increasing emphasis on the nationalisation of relief and joined forces with the IWRF in an ‘All British Appeal’. Aware that the bulk of their donations came from Britain, the SCF urged that national chapters within the ISCU receive full credit for their generosity.Footnote 111

The shift in the global power balance towards the USA and the emergence of the first communist state in Russia further politicised the question of humanitarian aid. With Hoover as its leading promoter, humanitarian aid was increasingly treated as diplomacy – if not war – by other means, explicitly aimed at winning the hearts and minds of distressed populations and fighting the spread of communism in Europe.Footnote 112 Hoover was convinced that food aid would ‘win the post war’, and for that goal strict national control and administration appeared indispensable.Footnote 113 A unified national front was supposed to ‘preserve American prestige’ and ensure that beneficiaries knew and appreciated that the help they received came from the USA, something assumed to enhance political, social, and economic influence.Footnote 114

The establishment of the US European Relief Council (ERC) in 1920 was a major step in this direction. Like many other organisations, it concentrated on relief for children and in addition to the ARA, it embraced the AFSC, the ARC, the Federal Council of Churches, the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), the Knights of Columbus, the National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC), and the Young Men’s and Women’s Christian Associations (YMCA and YWCA).Footnote 115 Within a few months, an appeal to save the children of Europe addressed to the US public resulted in US$29 million in donations in late 1920, with Hoover prominently leading the campaign.Footnote 116 The organisational collaboration continued during the Russian Famine, with some changes in membership.

The difficulty of coordinating international relief during the Russian campaign is well illustrated by the example of the Society of Friends. Despite a long tradition of close cooperation between British and American Quakers, first during the Russian Famine of the 1890s, and later during the First World War, the AFSC decided to sever ties with their British counterparts in 1921.Footnote 117 Setting aside concerns about principles such as pacifism, neutrality, and impartiality, the AFSC chose to join Hoover’s US relief efforts under the protection and with the ample resources of the ARA, rather than continuing its transnational approach on a more modest scale. As Daniel Maul argues, two recurrent conflicting ideas of humanitarianism are symbolised in this decision: national versus international, and professional versus ‘ethical’.Footnote 118 The Catholic Church was also subject to similar tensions. While the NCWC regarded its inclusion under Hoover’s ARA umbrella a victory for Catholicism in the USA, some clerics decried it as a loss of episcopal autonomy.Footnote 119 For practical reasons, the NCWC and the Papal Relief Mission were later affiliated with the ARA. However, Vatican representatives continually struggled for their independence, wanting to provide aid not in the name of the USA, but as the Catholic Church.Footnote 120

Russian Famine Relief

The devastation caused by the Russian Famine, and the extent and international dimensions of the relief efforts, were exceptional. Ideological and political factors complicated the situation, as the Bolshevik regime was still fragile and unrecognised by most Western governments. As a result, any bilateral arrangement was difficult and left humanitarian operations in private hands. Both exiled Russians and conservative foreign politicians were sceptical or openly hostile to the idea of supporting Soviet Russia with food, warning that this would stabilise the tottering regime. Others saw the famine as an opportunity, either for coming to terms with the new regime or for eliciting pro-Western attitudes among Russians and increasing the chance of a regime change. In fact, almost all relief help came from parties who were opposed to the ideology represented by Lenin, which in part explains why communist leaders deeply mistrusted foreign organisations and feared a counter-revolution in humanitarian disguise.Footnote 121 Nevertheless, they realised the benefit of accepting Western aid.

In the end, some 900,000 tonnes of relief goods were brought into the famine regions between late 1921 and early 1923. More than eleven million people were receiving food aid through foreign organisations by the time operations peaked in August 1922.Footnote 122 Relief was mainly delivered by two umbrella agencies, both of which signed treaties with the Bolshevik government: Hoover’s ARA and the International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR), led by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen. The ARA drew on the experience of its vast relief efforts in post-war Europe and provided more than four-fifths of all foreign aid. The ICRR was a creation of the ICRC, in cooperation with the Secretariat of the League of Nations. By 1921, both Hoover and Nansen were already internationally celebrated humanitarians.Footnote 123

Most US relief agencies, including the ARC, worked under the ARA auspices, while Nansen represented a number of organisations from two dozen primarily European countries. The majority of humanitarian committees and organisations dealt with fundraising only. The ARA was the main agency responsible for distributing US relief, but even the AFSC in Buzuluk and, at a later point, the JDC in Ukraine worked in the field, although on a much smaller scale. Nansen depended to a great extent on the SCF and the British Quakers, who established their own distribution systems in the provinces of Saratov and Buzuluk. Some national Red Cross chapters, including Italian, Swiss, and Swedish groups, also sought to direct relief work, but due to their limited resources, their efforts were often contingent on other players.Footnote 124

Despite conflicts among organisations, few relief agencies remained outside the Nansen and Hoover spheres, although some like the SCF and the Quakers later signed their own aid treaties with the Soviet government. The most relevant exceptions were communists, such as the Berlin-based Workers’ International Relief (WIR), and its US branch, the Friends of Soviet Russia (FSR).Footnote 125 There were also competing socialist and social democratic initiatives, such as one by the Amsterdam-based International Federation of Trade Unions, (IFTU), which mirrored ideological conflicts within the international workers’ movement. In Denmark, for example, three nationwide campaigns were organised: one by the Danish Red Cross, one by the Social Democratic Union, and one by the communist Committee for Aid to Russia – the Danish auxiliary of the WIR, led by author Martin Andersen Nexø.Footnote 126 Labour movement organisations followed an agenda that differed from that of Hoover and Nansen. They saw their efforts as part of an international class struggle, rather than as a humanitarian initiative, and regarded ARA relief in particular as ‘one part Trojan Horse, one part opiate’.Footnote 127 The WIR was also an exception in making extensive use of world-renowned artists and intellectuals, such as Käthe Kollwitz, George Bernard Shaw, and Albert Einstein, in their fundraising campaigns.Footnote 128

About a month after Gorky’s appeal, the ICRC organised a conference in Geneva on 15 and 16 August 1921 that brought together representatives from more than twenty humanitarian organisations and some governments.Footnote 129 The objective was to join forces and coordinate famine relief in Russia. The most tangible result was the establishment of the ICRR as an umbrella organisation. The initial plan of a dual European–US chairmanship failed, as Hoover, whose European representative had already negotiated terms for ARA relief with Russian authorities, declined the nomination. Therefore, Nansen became the sole high commissioner, and the ICRR remained a predominantly European body.

Apart from being a celebrity, Nansen was already an experienced humanitarian worker. His commitment to the repatriation of prisoners of war on behalf of the League of Nations had gained him international respect. In September 1921, he also became the League’s high commissioner for refugees, parallel to his engagement for famine relief in Russia.

However, the preconditions for Nansen’s work were difficult, as initially no government, except for his home country, Norway, supported the ICRR, nor would the participating humanitarian organisations financially commit themselves. Only the SCF pledged in advance to feed 10,000 children. While Hoover drew on the well-functioning machinery of the ARA and had ample financial means at his disposal when bargaining with suspicious Russian authorities in Riga, Nansen’s position was weak as he negotiated the conditions under which relief would be provided. When Nansen arrived on 20 August, Hoover’s representative had already successfully secured far-reaching US control over distribution and had even obliged the Russian government to fund part of the relief work with its gold reserves.Footnote 130

Nansen’s agreement was less favourable, particularly with regard to distribution. However, his major problem remained funding.Footnote 131 European governments were generally unwilling to invest in the enterprise, either by donations or with loans, which according to the Riga treaty, Nansen was bound to negotiate on behalf of the Soviet government. Back in Geneva, Nansen delivered two acclaimed speeches before the Assembly of the League of Nations. In the first, on 9 September, he appealed to European governments for help, pointing out that private relief alone was insufficient.Footnote 132 Two weeks later, he presented an emotional sketch of the absurdity of the situation: ships and a surplus of food were available, while twenty million people in Russia were starving and Western governments remained indifferent.Footnote 133

Nansen received applause for his speech, but little money. The ICRR continued its work, depending on private charity and supported by minor sums from a few governments such as Norway, Sweden, and the Baltic states. The principal affiliated organisations like the SCF, the British Quakers, and the Swedish Red Cross acted largely on their own in their fundraising and relief work, but in many cases served as distribution agencies for ICRR provisions.

Culmination

The development of humanitarianism after 1900 culminated in the relief efforts during the Russian Famine. Foreshadowing our designation of this humanitarian era, the SCF proclaimed during the Russian Famine that ‘whatever is not organised is dead’.Footnote 134 While ARA officials praised the centralised relief work under a national umbrella, they showed little understanding for the wishes of affiliated organisations to preserve independent operations or their own culture of altruism. With regard to efficiency, the ARA suggested that ‘all these organizations would be greatly benefitted if their funds were donated outright to the ARA’.Footnote 135 The SCF adopted a similar position, suggesting that there was no longer room for amateur philanthropy.Footnote 136 Professionalisation also meant that experts would handle the logistics of relief, procurement of food and other supplies, and accounting, as well as marketing and public relations – the latter an area that especially created conflicts.Footnote 137 During the Russian Famine, various organisations produced at least five films.Footnote 138 The SCF appropriated the slogan ‘Seeing Is Believing’ and attempted to settle public controversies by claiming their documentaries irrefutably proved the reality of famine.Footnote 139

A symbiotic mixed economy, with private relief organisations on the one hand, and the goverment on the other, was a necessity if comprehensive relief was to be provided for millions threatened by starvation in Russia, as the success of the ARA illustrates. It was possible because Hoover’s goals and those of Washington generally coincided. Hoover led the ARA as a private citizen, but was also secretary of commerce in the Harding administration. Nansen and the SCF were equally quick to declare governmental support indispensable, and put great effort into lobbying for state-financed relief missions. Other than symbolic success, however, they failed because they were unable to persuade European governments that their common interest justified a joint commitment. Although the SFC saw itself as a government corrective, its attempts to gain state support show the inevitability of a humanitarian mixed economy. Even the Quakers, with their storied incorruptible relief philosophy, considered it necessary to adapt to the new development during the Russian Famine, and so the AFSC reluctantly engaged in a pragmatic relationship with the ARA, not least because of Hoover’s access to government funding.

In the wake of Gorky’s appeal, lingering conflicts between the ICRC and major national Red Cross societies surfaced, and the ICRC tried to regain the ground it had lost by setting up Nansen’s high commissariat. At the same time, the ambitions of the League of Nations created new, sometimes painful discrepancies, as Nansen’s unsuccessful appeals in Geneva demonstrate. Similarly, the SCF experienced difficulties when they began to extend their activities beyond fundraising to launching their own transport and distribution systems. The AFSC, which had a working relationship with the ARA, also had such problems, and ended up fearing for the loss of their identity.

Hoover and the ARA were confronted with the question of how practical economically and politically their endeavour had been. Could both humanitarian and political success be repeated as supposedly achieved in Central and Eastern Europe? In the end, while the huge relief apparatus significantly alleviated the suffering of the Russian people, saving many lives and winning over many hearts and minds, the operation failed to destabilise the Bolshevik regime.

2.4 Famine in Ethiopia 1984–6 and Expressive Humanitarianism

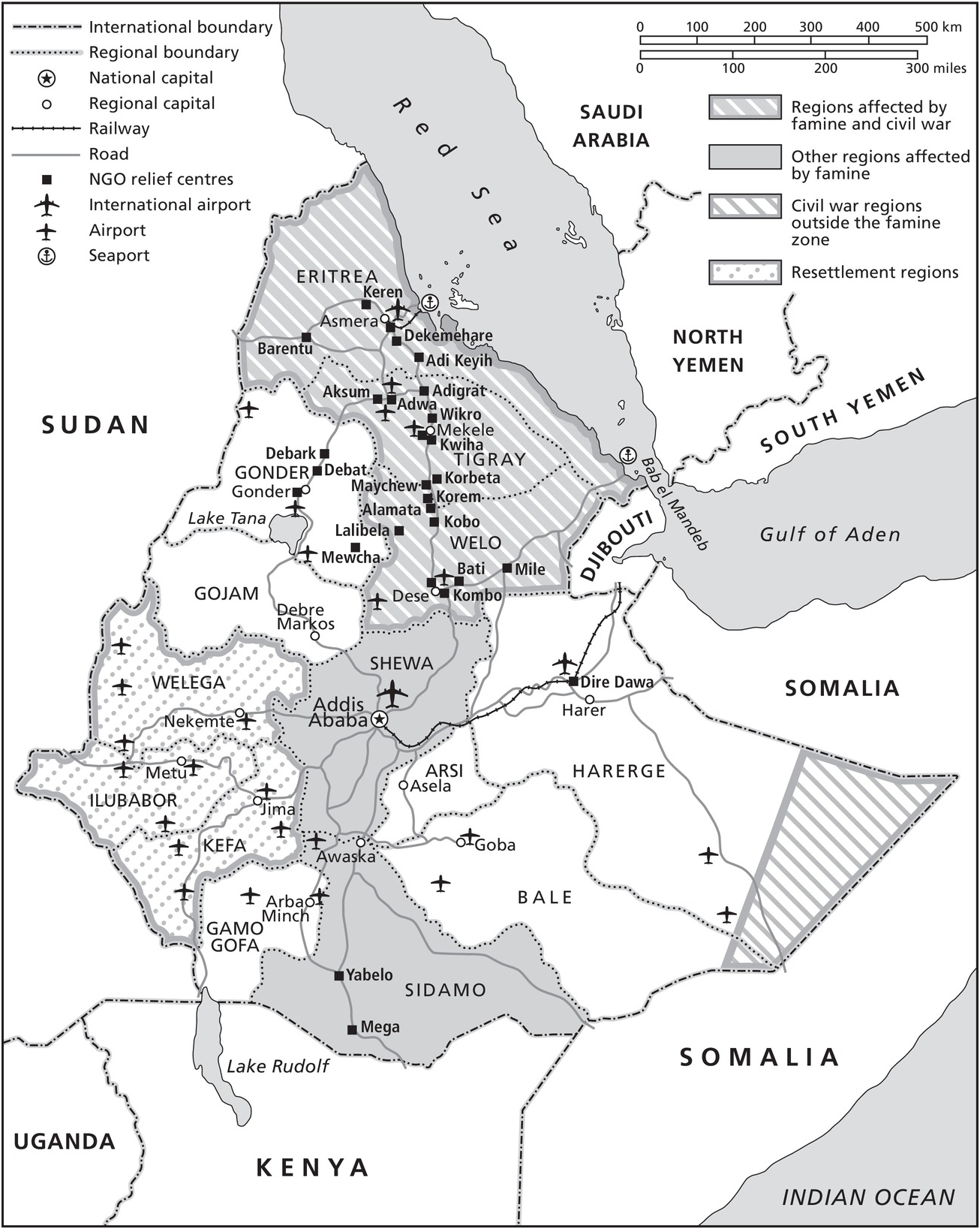

By late 1984, famine was affecting wide swaths of Sahelian Africa. The catastrophe had been developing since December 1982. Starvation acutely threatened more than seven million people in the northern and south-eastern regions of Ethiopia or approximately one-fifth of the total population. Warnings from aid organisations had been ignored by the international community and the government downplayed the scale of the crisis. In the 1980s, Ethiopia was ruled by a committee of military officers known as the Derg, headed by President Mengistu Haile Mariam.Footnote 140 These Marxists had assumed power after a 1974 coup d’etat which overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie. They consolidated their rule through a reign of terror. The long civil war the military government engaged in against the secessionist Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) escalated in 1985 (see Figure 2.3).Footnote 141 In 1982, the World Bank ranked Ethiopia as the second poorest country in the world in terms of GNP per capita. Owing to its socialist ideology, the country could not attract significant foreign investment or development aid.Footnote 142

Figure 2.3 Map showing famine-affected regions of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Tigray, 1985.

The causes of the famine are complex and disputed, but civil war, years of drought across the Sahel region, compulsory land reform, and forced collective farming policies all played a part. In addition, food aid was late in coming, and when it did arrive, problems supplying relief to rebel-held areas as well as the regime’s programme of forced resettlement for famine-affected people added to the death toll. Meanwhile, the Derg diverted food from rural areas to urban markets in an attempt to stifle political dissent in the cities. Estimates vary, but between 400,000 and 1 million people are believed to have died between 1984 and 1986.Footnote 143

An Age of Expressive Humanitarianism

The famine in Ethiopia has been cited as a landmark in the history of humanitarianism, both by those who participated in the relief operations and by others who have later written about it.Footnote 144 It signified an age of expressive humanitarianism, marked by the Band Aid and Live Aid movements, and including other phenomena that engaged the world-at-large. The relief effort saw the culmination of several trends that had their origins in the late 1960s and became prominent in the response to the humanitarian crisis in Biafra of 1968–70. These included (a) a media-driven understanding of disasters and relief efforts, as Biafra was the first time a famine was televised;Footnote 145 (b) an emphasis on celebrity, spectacle, and mass participation in relief, described as a ‘revolution in giving’ in which aid and development became attributes of an enlightened lifestyle and attracted formerly uninterested donors;Footnote 146 (c) the transformation of voluntary giving beyond established agencies to new organisations such as Band Aid, which received large sums of money and became conduits between donor governments, the charitable public, and recipients of relief, as well as voicing a commitment to ‘people-to-people’ aid;Footnote 147 and (d) an increased humanitarian concern for witnessing and reporting on misdeeds and perceived manipulations of aid.Footnote 148

The period between the 1960s and the famine in Ethiopia saw the ‘rise and rise’ of humanitarian organisations.Footnote 149 The formation of a global aid regime in the Cold War was in part facilitated by the Soviet boycott of many of the international organisations through which this system operated. It created the context for Western powers to treat development problems and humanitarian emergencies from a security point of view, employing their aid ‘to contain communism, delegitimate national liberation movements, and reproduce neocolonial rule’.Footnote 150 The Biafran crisis clearly revealed these tendencies, at the same time, it was a post-colonial conflict and domestic power struggle in West Africa that instrumentalised suffering for political ends, provoking new responses, but also rendering those offering relief complicit.Footnote 151

In May 1967, the eastern region of Nigeria declared its independence under the name Republic of Biafra. The subsequent blockade imposed by the Nigerian government led to widespread starvation, with eight million people considered in danger. The famine came to media attention around the globe in early 1968 through the efforts of Christian missionaries. The televised images of starving children pushed aid agencies and governments to take a stand, despite the complex political situation. The response signalled a break with humanitarian traditions and the emergence of a more politically engaged humanitarianism, most evident in the creation of MSF, but also seen in less well-known groups such as the Oxfam spin-off Third World First.Footnote 152 In 1968, a group of French doctors led by Bernard Kouchner publicly denounced the Red Cross principles of silence and neutrality in Biafra. On returning home, they organised marches and media events to raise awareness of Nigerian atrocities against civilians. Their activism, followed by similar experiences in Bangladesh, led to the formation of MSF in 1971.Footnote 153 Kouchner and his followers were part of a new generation of humanitarian individuals who cultivated close links with the media. Kouchner developed humanitarian action as a form of theatre or carnival.Footnote 154 MSF cherished the idea of témoignage (speaking out), although how and when this should be put into practice was subject to internal dispute. Following a split in 1979, Kouchner went on to found Médecins du Monde. By the early 1980s, MSF had become a ‘brand’ with a privileged place in French politics, but was also known for its increasingly anti-communist stance and critical view of Third Worldism.Footnote 155

The role played by voluntary organisations in disaster relief had a greater impact in attracting public attention than long-term development efforts. In the final quarter of the twentieth century, it became increasingly evident that for many organisations ‘association with high profile disasters was good for business’.Footnote 156 After Biafra, voluntary agencies acquired a reputation for efficiency, in part based on a perceived ability to work with grass-roots communities. With each major relief operation (including Bangladesh in 1970–1, the Sahel region in 1973, and work on the Thai–Cambodian border after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979), the ‘humanitarian international’ appeared as ‘more powerful and more privileged’.Footnote 157 Musicians and pop stars also became increasingly engaged in humanitarian activities, a development seen in George Harrison and Ravi Shankar’s 1971 Concert for Bangladesh and the 1979 Concerts for the People of Kampuchea (Cambodia).Footnote 158 Although modest in comparison, such events paved the way for Irish singer Bob Geldof’s global success with Band Aid and Live Aid during the 1980s.

Ethiopia, Famine, and Media-Driven Humanitarianism

In Ethiopia, recurrent famines had been met by indifference to suffering under the rule of Haile Selassie, but in 1973, the media spotlight shone on the region with the documentary ‘The Unknown Famine’ by British broadcaster Jonathan Dimbleby. It led to a global response and precipitated the emperor’s downfall.Footnote 159 The new military government set up a Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) to oversee aid work. While this institution built a reputation as one of the most effective famine relief agencies in Africa in the 1970s, with 12,000 staff across Ethiopia, by the early 1980s it had become compromised as an arm of the Mengistu regime.Footnote 160 The RRC was widely distrusted and its communications treated with scepticism by international donors. The result was that an urgent appeal for food aid in March 1984, after the failure of the short rains, was largely ignored by relief agencies.Footnote 161 A second organisation to emerge from the 1973 famine which played a key role a decade later was the Christian Relief and Development Association (CRDA). Formed mainly of Catholic charities, along with other religious groups, some secular agencies, transnational organisations, and domestic groups, CRDA’s creation was the first organised cooperation in Ethiopia between the government and voluntary organisations.Footnote 162

Initially, the mounting disaster in Ethiopia was covered only to a limited extent by the international media. In early 1983, appeals for food aid led to some news coverage and donations in the USA and Europe – particularly from the UK, Germany, and Sweden. In July 1984, a public appeal was made by the UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) to accompany a television documentary.Footnote 163 In retrospect, the delay in relief efforts has been attributed to a de facto alliance between top officials in the Reagan administration and the Mengistu regime, neither of which wanted a large-scale response. Approaching its tenth anniversary in power in August 1984, the Ethiopian government did not wish to draw attention to either famine or civil war. It exerted tight control of travel visas for journalists and aid workers during the summer of 1984. The USA, for its part, had suspended development assistance to Ethiopia in 1979 and was reluctant to participate in a relief effort for a Soviet-aligned country until increased publicity forced a change in attitude.Footnote 164 United Nations (UN) agencies and voluntary organisations themselves were also partly responsible for the delay. Scepticism over RRC figures was compounded by inaccurate and misleading data on food aid requirements from the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) during 1984.Footnote 165 At the time, many donors regarded the RRC’s invocation of the international community’s moral responsibility as offensive.Footnote 166

By September 1984, its anniversary celebrations over, the Mengistu regime shifted from a policy of denial to one of blaming the international community for the famine, notably the US government. The Ethiopian regime was not so much reluctant to accept aid, as it was to receive it on its own terms. It had traditionally preferred development assistance to emergency relief.Footnote 167 The CRDA telexed an urgent appeal calling for ‘immediate, massive, and coordinated’ action.Footnote 168 Film-maker Peter Gill, who had long been seeking access to the famine-affected regions, proposed making a documentary that would contrast overproduction of food in Europe with hunger in Ethiopia, and this met with approval, enabling him to get the necessary travel permits. Other journalists were granted access to the afflicted area. On 23 October 1984, in a now famous BBC television newscast, reporter Michael Buerk and video journalist Mohamed Amin drew the world’s attention to a ‘biblical famine’ affecting large tracts of Ethiopia. In the days that followed, their film was rebroadcast by 425 stations, reaching a global audience of 470 million, and finally sparking a major international response.Footnote 169 The famine in Ethiopia became ‘the story, and the cause’.Footnote 170 The moral outrage it raised was heightened because news of the famine came immediately after a widely reported abundant harvest in Europe, which further swelled the European Economic Community’s (EEC) notorious ‘grain mountain’.Footnote 171 As the head of the RRC put it, his country had been forgotten ‘by a world glutted with a surplus of grain’.Footnote 172

International Response