Introduction

In 1973, a Barclays banker declared that the bank’s goal was, ‘for a number of years’, to be at the ‘forefront’ of East–West financial relations.Footnote 1 He was referring to a discussion paper on Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) highlighting a significant rise in East–West diplomatic and trade contacts. As a mission statement it neatly sums up the ambitions of UK banks as they addressed the easing of East–West tensions that came to be known as détente.

UK banks played a key role in the development of East–West relations during the Cold War through actively developing business ties with CEE countries in the pursuit for new foreign markets, driven by a desire to expand their business. The UK government viewed these relationships as a way to advance its foreign policy goals towards CEE and strengthen East–West political and economic relations, which it aimed to promote through export credit guarantees granted via its Export Credit Guarantee Department (ECGD). Such political motivations would later play an important role in how the UK government, UK banks and the Bank of England navigated the Central and Eastern European sovereign debt crisis.

There is limited literature on the role of the UK’s ECGD in the context of the Central Eastern European sovereign debt crisis, with the exception of Lefèvre,Footnote 2 who analyses the ECGD in relation to the Polish debt crisis from a UK government perspective, and Mourlon-Druol,Footnote 3 who briefly discusses the ECGD but primarily focuses on France’s export credit agency (COFACE) when examining the sovereign debt crisis in Poland.

In Europe, the development of political, economic, financial and cultural ties between Western European and CEE countries was enabled by détente, which ‘became a key feature of the continent from the mid-1960s until the end of the Cold War’.Footnote 4 During this time, both Western European and CEE countries were keen to cultivate relations with each other.Footnote 5

Western European countries were driven by a desire to establish closer relations with CEE countries, working towards a united Europe, as well as countering Soviet influence in the region.Footnote 6 Enabled by détente, UK banks began developing relations with CEE in the mid- to late 1960s, which accelerated during the latter part of the decade, alongside the internationalisation of banking, as financial institutions increasingly sought opportunities to expand their activities and diversify their portfolios abroad.Footnote 7 CEE countries also enjoyed a solid reputation for servicing their debt on time and so had little difficulty borrowing money from the West.Footnote 8

This internationalisation was driven in part by competition between banks, who not only wanted to support their clients’ ventures in Europe and further afield, but also saw it as a way to maintain the ‘prestige and reputation of their institution’.Footnote 9 Another stimulus was the large surplus of dollars, known as petrodollars, being deposited in Western banks by oil producing countries during the first oil crisis of 1973. This led to a boom in sovereign lending to developing countries, including to CEE.Footnote 10

In the early 1970s, countries such as Hungary and Poland adopted ‘consumer socialism’, whereby they aimed to improve living standards and access to consumer goods in order to maintain political stability.Footnote 11 CEE countries also undertook investment programmes, such as in the energy intensive steel and petrochemical industries, to boost productivity and accelerate economic growth, relying on foreign technology and loans to support these initiatives.Footnote 12 The idea was that these industries would produce goods that could be exported in return for hard currency, which would then be used to pay back their loans to the West.Footnote 13 As they became increasingly dependent on Western credit, the shortcomings of CEE economies, combined with other domestic and global factors, such as the second oil crisis and the rise in interest rates, made servicing loans more expensive.Footnote 14 This meant they were unable to reap the benefits of their investments, which would ultimately contribute to the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in the region between 1981 and 1982, when they were no longer able to service their debt payments to the West.

This article draws on a variety of archival sources – notes, letters, reports and papers produced by UK bankers from Barclays, Lloyds, Midland and National Westminster, and officials from the Bank of England and the UK government, and is divided into three sections. It begins by discussing how UK government policy towards CEE developed over time from the 1960s to the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis. The second section focuses on how UK banks developed relations with CEE countries through visits, joint ventures and the provision of loans, and explores how the UK government supported and encouraged these initiatives through the Department of Trade, British embassies based in CEE and the Export Credit Guarantee Department (ECGD) with the aim to strengthen UK–CEE relations. It illustrates the evolving relationship between banks and the state during the Cold War, particularly with the use of the ECGD as a tool to direct the flow of credit towards CEE for foreign policy reasons. The final section examines how the UK government and banks became aware of the growing indebtedness of CEE countries in the mid-1970s, and how their reactions and response to the outbreak of the crisis were informed and influenced by the UK government’s foreign policy, through the Bank of England.

The Development of UK Government Policy Towards CEE

The UK government’s interest and policy towards CEE countries developed over time as successive governments came to power. Poland was of interest to the UK government due to the development of pluralism in the country with the emergence of the Catholic Church and the Polish trade union, Solidarity (Solidarność), as political actors that challenged the orthodoxy of the one-party socialist state.Footnote 15 Hungary was of interest as it decentralised economic decision-making and freed prices from central control – a model that the UK government wanted to see other CEE countries replicate.Footnote 16 Romania was of interest due to its willingness to pursue its own foreign policy goals independent of Moscow, which the UK government saw as an embarrassment to the Soviet Union.Footnote 17 The UK government was keen to encourage and support these trends as part of a broader foreign policy to counter Soviet influence in the region. During this time there was also a discussion within the UK government on the idea of a united Europe that included CEE, with a long-term policy focused on ‘working against the whole concept of the Iron Curtain’ and the aim to expand its relations with CEE countries ‘at all levels and in all fields’.Footnote 18

In the early to mid-1960s, the UK was at the forefront of engaging in frequent exchanges of ministerial visits with CEE and the Soviet Union. These personal contacts were an important element in fostering relations between states and helped to normalise political relations with CEE countries, improving the overall political landscape in Europe. CEE government officials attached a lot of importance to the frequency and level of seniority of these ministerial visits and used it as a way to measure the state of their bilateral political relations with the UK and other countries.Footnote 19 Besides ministerial visits, the UK was also a pioneer in promoting dialogue and cooperation with these countries through trade and was the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance’s (CMEA) main trading partner in the West until the mid-1960s.Footnote 20

Under the Conservative Edward Heath government (1970–4), UK–CEE relations were initially stagnated, primarily due to the UK’s negotiations to enter the European Economic Community (EEC) between 1970 and 1972, which were a priority at the time.Footnote 21 The negotiations finalised with Heath signing the Treaty of Accession in Brussels on 22 January 1972. In doing so, he gave a speech where he underlined the UK government’s desire to see CEE brought closer to the West: ‘“Europe” is more than Western Europe alone. There lies also to the east another part of our continent: countries whose history has been closely linked with our own’.Footnote 22 Consequently, Heath’s government began to develop its links with CEE countries by ‘adopting a more active policy towards the East’, for which it saw ‘good commercial and political reasons’. Commercially, the economies of CEE countries were growing and therefore presented opportunities for UK banks and businesses to invest and trade at a time when the domestic UK economy was stagnant and its exports were in decline. Politically, such links allowed the UK to counter Soviet influence in the region and encourage CEE to move closer to Western European countries.Footnote 23

When Labour came to power in 1974 under Harold Wilson (Prime Minister 1974–6) and later James Callaghan (Foreign Secretary 1974–6, Prime Minister 1976–9), both Wilson and Callaghan made concerted efforts to pursue a more active policy towards CEE and develop the UK’s diplomatic, trade and cultural links with CEE countries to further détente and promote closer relations. The Labour government was keen to ‘re-establish lines of communication with the Soviet and East European Governments which had fallen into some disrepair … [and] had been working through the backlog and making up for lost time’. They wanted UK relations with these countries to be on a par with their main West European allies.Footnote 24 In the words of Callaghan, writing as Wilson’s Foreign Secretary, ‘the more links of all kinds – economic, cultural and human – that can be developed … the more difficult it will become for the Soviet Union … to sever them’.Footnote 25 In 1975, UK–CEE relations greatly improved in terms of trade and increased ministerial visits in both directions in comparison to previous years.Footnote 26

With the election of Margaret Thatcher and a Conservative government in 1979, the UK continued to pursue the goals of previous governments, with Thatcher calling for contacts with CEE countries ‘at all levels’. This would allow the UK not only to learn more about CEE countries but also to cooperate on shared interests such as preventing ‘the wider proliferation of nuclear weapons’, and promote trade, particularly as there was a possibility of winning large business contracts for UK firms. The UK government also recognised that political relations were important for promoting UK–CEE economic relations, given that CEE governments were in charge of foreign trade, and so it aimed to ‘continue to provide substantial Government support for the efforts of British firms to secure business’.Footnote 27

Thatcher’s government also brought with it a more assertive foreign policy agenda towards CEE. This is characterised by the implementation of the policy of differentiation, by which the UK government would officially recognise the individuality of each CEE country and exploit these for foreign policy reasons.Footnote 28 It also adopted the policy of positive discrimination, which would reward countries that demonstrated divergence from the Soviet Union, for example by expanding trade or easier access to loans. Through this policy the UK government ‘rewarded Romania for its “independent” foreign policy; encouraged economic experiments in Hungary; and offered economic help to Poland’.Footnote 29

Expanding trade, economic and financial links was important in advancing UK and Western foreign policy goals of maintaining the stability of détente, disseminating Western values to CEE countries and encouraging them to move closer to Western Europe, away from the Soviet sphere of influence, that could make a united Europe possible. UK banks played an important role in the development of these links, which successive UK governments were keen to support.

UK Banks Developing Relations with Poland, Romania and Hungary and Its Significance to the UK Government

From the mid- to late 1960s onwards, UK banks began searching for new international markets, such as CEE, to expand their global reach, enhance their reputation and strengthen their competitiveness in relation to other domestic and foreign banks.

In order to achieve these goals, bank managers and other senior bankers such as chairmen from UK banks would visit CEE countries to develop contacts, find business opportunities and gain an understanding of the political and economic situation of the countries in which they were investing. These visits also helped UK bankers keep abreast of what their CEE counterparts were thinking, such as their wish to increase trade and business links with the UK, whether they had plans to open a branch in London or the possibility of setting up a joint venture with a UK bank.Footnote 30 CEE governments and bankers valued these visits and made considerable efforts to court commercial visitors by organising day trips, lunches and dinner arrangements in the hope of securing more concessions or a better deal from Western banks.Footnote 31

As part of these visits, bankers would write up reports on their trips, detailing their observations, such as how day-to-day life appeared in the countries they visited or the current political and economic situation, also remarking on how economic conditions had changed. They also detail outcomes of meetings with local bankers and UK embassy staff. In the early 1970s, UK bankers found CEE countries in the process of impressive economic growth with rapidly improving living standards and the associated business opportunities for banks that came as a result. A report from a Barclays visit to Romania by A.F. Tuke (Vice-Chairman), G.B. MacPhail (Manager) and G.A. Elce (Manager Eastern Europe) in 1971 praises the country’s rapid economic development, noting that on average Romania’s economy had grown 13.5 per cent in the previous five years, which was deemed ‘most impressive and easily the best in Eastern Europe’.Footnote 32

In a report on Hungary from the same year, R.G.W. Lambert (Barclays European Representative) writes of his surprise at the evident changes in the country’s capital, Budapest, in comparison to a previous visit made five years earlier. He observed that there were more buildings and a noticeable improvement in living conditions, remarking that: ‘the streets used to be comparatively empty of cars, Budapest now shares with capitalist countries the benefit of parking difficulties’.Footnote 33 Similarly, R. Dye (International Manager for Eastern and Western Europe) and R.K. Froom (Manager) visited Poland in 1973 ‘with an air of optimism’ as the country had become the largest market for UK exports in CEE and Poland’s credit rating was declared to be Grade A, ‘good for any amount’ by the ECGD.Footnote 34 Lloyds archives assert that Poland was the UK’s most important trading partner out of all the CMEA countries and that, as a group, CMEA, which included CEE countries, represented a significant market for UK goods, ‘roughly on a par with Latin America in terms of the value of British exports’.Footnote 35 It is therefore no surprise that UK banks saw the region as a sound investment.

The UK government recognised the importance of UK businesses for encouraging and strengthening East–West European relations and achieving its foreign policy goals in the region. The government was keen to support the initiatives of UK firms in CEE through a range of channels such as the Department of Trade, British embassies based in CEE and the ECGD.

The Department of Trade gave information to UK businesses on CEE, drawing on diplomatic reports. It also shared information on the UK’s commercial offerings to CEE and ‘spent a great deal of time … following the individual negotiations of each British firm’.Footnote 36

British embassies based in CEE worked together with the Department of Trade and the British Overseas Trade BoardFootnote 37 to support UK firms interested in doing business in the region. CEE governments placed great emphasis on formal detailed agreements that covered issues such as trade and technological cooperation. When doing business with CEE countries it was also important to know ‘whom best to approach in the host government’s various ministries on a particular question, and being sufficiently well acquainted with them to be able to contact them’.Footnote 38

Banks such as those in the UK and France maintained a close relationship with their embassies. They would frequently meet with embassy staff to exchange points of view, receive updates on local developments and participate in meetings along with other bankers and local officials.Footnote 39 As noted by Barclays bankers on a visit to Hungary, ‘the British Embassy were very helpful and, as usual, well informed’ on matters related to CEE countries.Footnote 40

Embassies would also give banks reassurance on the situation in CEE countries and support their business in the region. UK banks, as well as other Western banks, made efforts to embark on joint banking ventures with CEE banks. This allowed UK banks to establish closer links with CEE banks that could lead to increased access to CEE markets and more business. For example, Barclays sought ‘to establish joint ventures in London with the major Communist monopoly banks that are not already committed with a branch in London’.Footnote 41

By 1973, this had been achieved with Romania with the establishment of an Anglo-Romanian bank in London, in which Barclays entered a partnership with the Romanian Bank For Foreign Trade and the US Bank Manufacturers Hanover Trust.Footnote 42 The bank had also identified Poland as a priority country for setting up a joint venture with Bank Handlowy. The UK embassy in Poland ‘welcome[d] the move’ of improving and expanding relations with CEE countries.Footnote 43 There was also an interest in pursuing a similar initiative with the Deutsche Aussenhandelsbank from East Germany and Zivnostenska bank from Czechoslovakia. It was hoped this could lead to the establishment of branches or representative offices in CEE countries, which would not only help to increase their share of CEE business but also improve their competitiveness in comparison to other Western banks in the region by ‘virtue of our [Barclays] superior international spread and service’.Footnote 44

Besides joint ventures, banks offered credit to CEE countries throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, often through syndicated loans that were composed of funds provided by a group of banks. This allowed banks to reduce risks and limit their exposure.Footnote 45 With these loans there would be lead banks such as Lloyds, Barclays, Midland and National Westminster that would make decisions on whether to participate or not based on risk. Smaller banks would typically leave risk assessment to lead banks.Footnote 46

To support and encourage UK bank lending in CEE, the UK’s ECGD offered up to 90–95 per cent coverage to any UK business that would sustain a financial loss in CEE to reduce the risk of doing business in the region, with the percentage of coverage decided on a case-by-case basis. This level of coverage was deemed justifiable for those investing in CEE countries, where the retraction of an import licence, embargo, military activity or even the outbreak of war were potential risks.Footnote 47

Allowing UK banks to access government guaranteed credits gave them a source of low-risk lending and encouraged them to pursue even more business opportunities in CEE, which directed the flow of credit in favour of CEE countries.Footnote 48 For example, in Romania, the ECGD offered coverage to projects such as the installation of a sprinkler and irrigation system by a UK firm.Footnote 49 In Poland, projects such as the construction of a PVC factory and airport terminal building, as well as the development and modernisation of a tractor factory, were covered.Footnote 50

The ECGD was set up in 1919 as an independent department reporting to the President of the Board of Trade with the aim to address issues with financing exports to Central and Eastern Europe. Over time, the department’s responsibility evolved and it began offering insurance for UK businesses exporting goods to CEE countries.Footnote 51 In 1964, the ECGD offered its first export credit guarantee in CEE, to Czechoslovakia, with a repayment term of twelve years, which set the tone for the UK’s later dealings in the region.Footnote 52

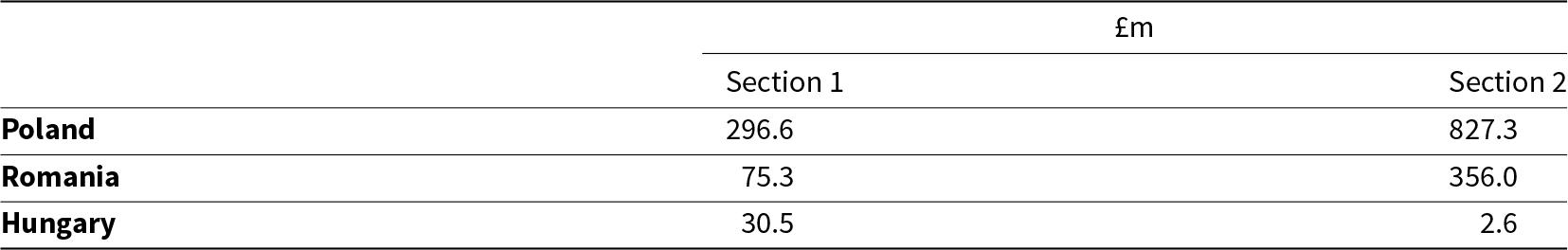

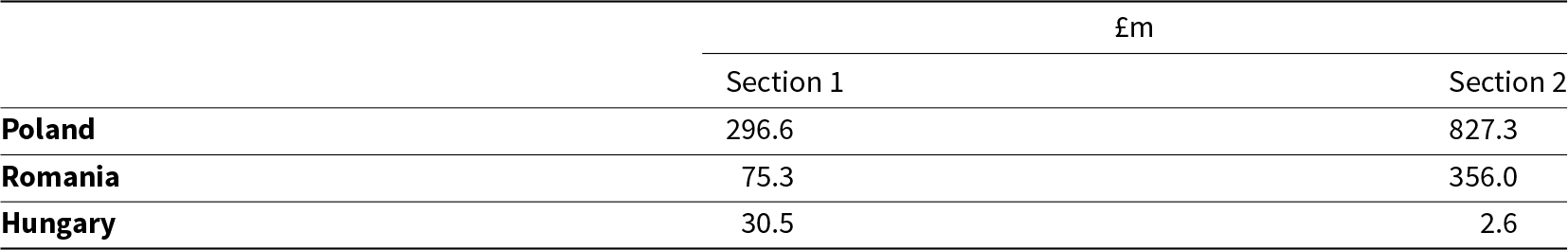

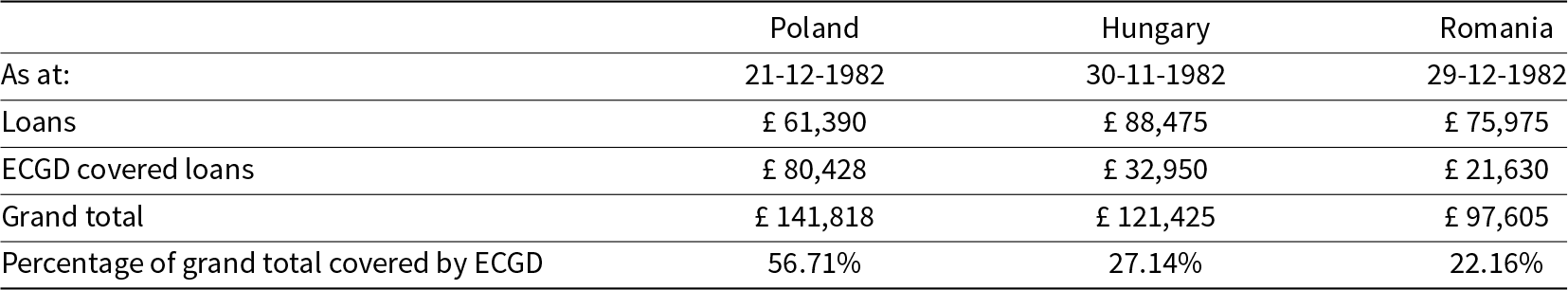

The ECGD granted credit guarantees under section one for ‘ordinary commercial business’ and section two for ‘business which would not be covered on commercial grounds but is regarded as justified in terms of UK national interest’. Any changes to the policy of section one were determined by the ECGD’s Advisory Council, which met monthly. Its members had backgrounds in economics and finance, such as bankers, export businessmen, commercial insurers and a representative of the Department of Trade. The policy of section two was overseen by the Export Guarantees Committee (EGC), which was chaired by the UK Treasury and made up of Bank of England and government officials, including those representing the ECGD, FCO, the departments of Trade and Industry, and other interested departments such as Defence.Footnote 53 Table 1 illustrates how many credits to Poland, Romania and Hungary were granted under section one and two as of October 1979.

Table 1. ECGD cover and commitments in CEE markets as of October 1979 (in millions of pounds sterling)

Source: Arrangement for cover and commitments on Eastern European Markets, Appendix A to ECGD paper Eastern European Indebtedness, January 1980, attached to note by Whitear and Nelson (HM Treasury), 5th of March 1980. BoE Archive 6A175/1.

Through section two, the UK government was able to influence the granting of export credit guarantees to CEE countries for political reasons. Provided a country had not entered into debt rescheduling, the EGC was able to process a credit guarantee application on a case-by-case approach and authorise a line of credit with a UK bank, with that enabling a certain volume of ‘officially insured trade’ to continue.Footnote 54

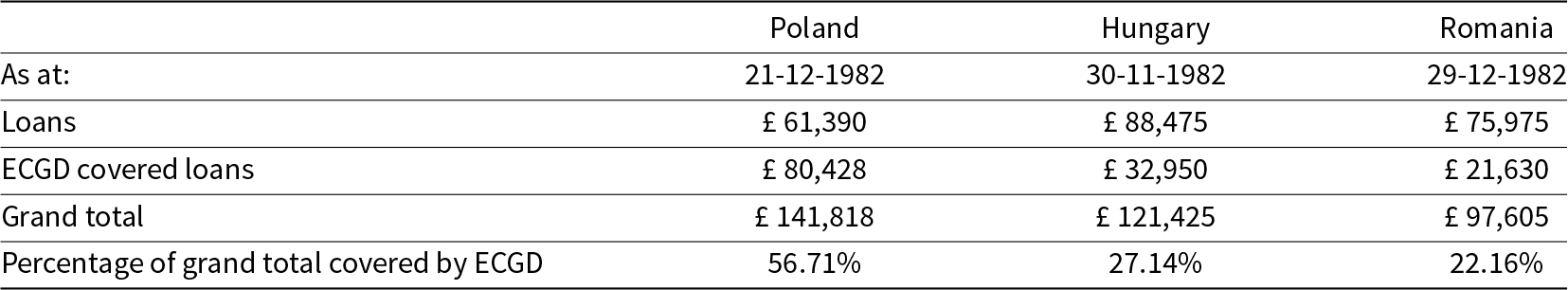

In doing so, the ECGD helped to ensure the alignment of economic activities with the UK’s broader foreign policy goals, as providing export credit guarantees to UK firms doing business in CEE contributed to strengthening UK–CEE relations and expanding the UK’s influence in the region. Table 2 illustrates the extent of ECGD coverage on Barclays loans, with over 50 per cent of loans to Poland, and approximately a quarter of the loans to Hungary and Romania, receiving coverage. Further evidence from Lloyds demonstrates that the ECGD offered similar coverage to Lloyds bank. By September 1981, $161.9 million of the $293.3 million lent to Poland by the group was covered by the ECGD, around 55 per cent.Footnote 55

Table 2. Analysis of Barclays loans outstanding, late 1982 (in thousands of pound sterling)

Source: Adapted from Mourlon-Druol, ‘Banking on Détente’, 710.

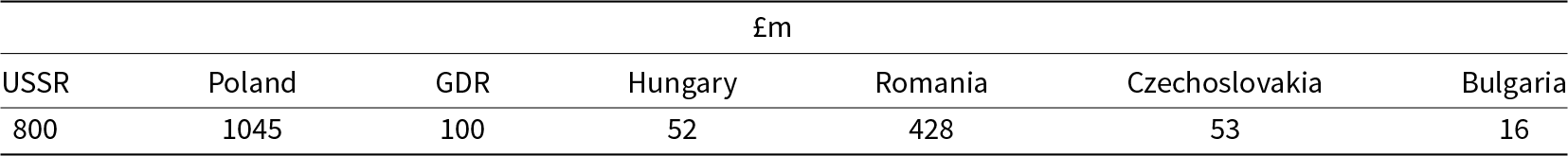

The extent to which the UK government guaranteed loans to CEE countries meant that part of the debt in the region was accumulated through these loans. Based on the data available, the UK government estimated the ECGD’s commitment to the Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe to be around £2.5 billion in February 1981, broken down into the figures per country, as illustrated in Table 3. It shows that the ECGD’s highest coverage in CEE was for loans to Poland, followed by Romania, and Hungary second lowest.

Table 3. ECGD’s total commitments on bloc as of February 1981 (in millions of pounds sterling)

Source: Defence and Oversea Policy Committee – Poland: Possible Economic sanctions, Annex III, 13 February 1981. CAB148/197.

Export credit guarantees not only helped to increase trade and financial links between the UK and CEE countries but also supported wider East–West European political relations. The UK and France are notable for their extensive use of export credit guarantees, which were combined with low interest loans on generous terms such as long repayment periods.Footnote 56 As noted by Bartel, guaranteeing loans to CEE countries ‘served the political purpose of normalizing interstate relations and the economic interest of exporters’ for Western countries.Footnote 57

It is clear that Cold War foreign policy objectives on the part of the UK government changed the way in which UK banks conducted business in Central and Eastern Europe, affecting bank lending behaviour and their approach towards risk. A letter by Julian Wathen (Barclays General Manager) underlines the appeal of ECGD loans to UK banks as he ponders whether Barclays could increase its percentage of UK government-backed loans. In his words: ‘perhaps we could wrest more mileage out of ECGD help to Eastern Europe’.Footnote 58 As deals with CMEA countries went through ministerial departments and CMEA banks, Barclays conducted its business with CEE countries through its International Division’s Correspondent Banks Department.Footnote 59 A report by Barclays discussing banking activities in 1982 confirms that the bank had been prioritising export credit finance and that the results had been positive. The bank acquired fifty-seven buyer credit mandates from UK exporters that year and had developed a strong export credits management team.Footnote 60 Lloyds also had a division within the bank that dealt specifically with export finance,Footnote 61 and its reports underline the role of export credit guarantees in its lending strategy. They state that the bank had made various financial packages available to CEE through ECGD guaranteed finance.Footnote 62

The case of the ECGD underlines that UK–CEE Cold War relations cannot be fully understood without taking into account the multilayered relationship between the UK government and UK banks. This relationship became yet more important as CEE countries started to feel the impact of their growing indebtedness, which would culminate in the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in the region, to which UK banks, the UK government and the Bank of England had to respond.

Debt Awareness and Outbreak of the Sovereign Debt Crisis

In the mid-1970s, the UK government became aware of the rising debt levels in CEE and recognised that the ‘growing level of East European indebtedness, in Poland in particular, is naturally a matter for concern’ and that careful monitoring was needed.Footnote 63 In 1976, UK banks also became aware of the increasing debt levels in CEE. A summary of a Bank of England meeting with UK banks on overseas affairs discusses how debt problems arising from sovereign lending were becoming visible in CEE and that debt rescheduling was approaching. It was noted that the Bank of England, with the approval of UK banks, intended to gather lending figures for each indebted country, CEE and beyond. This would be consolidated by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), who were looking to collect data from central banks of creditor countries to develop a global picture of debt exposure.Footnote 64

UK bankers began observing the changing political and economic landscape in CEE due to the worsening economic situation and debt build-up in these countries in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A Lloyds bank report on Hungary from August 1978 discusses the challenges facing the Hungarian economy at the time and states that despite these difficulties, the country was able to maintain internal political stability, said to be the ‘Hungarian regime’s greatest asset’.Footnote 65 A similar report on Poland from November 1978 portrays a different picture and highlights that the Polish authorities were making an effort to ‘avoid an open confrontation with dissidents and use ad hoc measures to improve market supplies if the situation threatens open unrest’.Footnote 66 Similarly, during a visit to Romania in May 1981, F.F. van Eyssen (Assistant Manager, Eastern Europe) at Midland bank observed that ‘there are signs that official attitudes may now be changing in anticipation of possible unrest in the future’. These signs included a shift in focus to agriculture at the expense of industry, efforts to address food shortages and initiatives to increase exports.Footnote 67

The ECGD had also observed signs of the worsening situation in CEE, as the number of government-backed credits had more than doubled between late 1975 and September 1979, from $20bn to $45bn respectively.Footnote 68 Notwithstanding the debt build-up in CEE, the ECGD was not deeply concerned about the developing situation in the region in early 1980. As stated in a February 1980 ECGD report:

Despite the uncertainty and less promising outlook for the East European countries, they do represent an area of the world with a meticulous payments record and a credit risk more acceptable to us than that in other parts of the developing world. We would agree that a careful watch needs to be maintained over their performance but that, Poland apart, we have not yet reached the stage where a completely negative policy towards new major contracts needs to be adopted.Footnote 69

Similarly, at an Export Guarantee Committee meeting a month later, the Bank of England expressed concerns about the UK’s credit policy for CEE countries and advised that caution should be exercised towards the countries that were becoming, or were already, over-extended.Footnote 70

Despite this, the ECGD made efforts to maintain the coverage it offered on loans to Poland. This was partly due to the country’s good record of payment, but also for political reasons. There was a recognition that reducing coverage would be seen negatively by the Polish government, which could have a detrimental impact on UK–Polish relations that the UK government was keen to see maintained and increased over the long term.Footnote 71 This is evidenced in a letter from the ECGD to HM Treasury, which states that:

we must not lose sight of the Poles’ extreme sensitivity on questions relating to their creditworthiness and the importance they are likely to attach to creditor country attitudes when determining their long term political and trade relationships. It would also be in our interests to avoid being seen as the Western country leading the retreat by cutting back on cover for Poland; particularly in the light of the French, Austrian and German attitudes towards financial assistance.Footnote 72

In March 1981, the sovereign debt crisis broke out in Poland as it could no longer maintain its debt payments.Footnote 73 It would spread to Romania a few months later and Hungary in 1982. Shortly after the outbreak of the crisis there was a discussion in the Cabinet Defence and Oversea Policy Committee on whether to offer further credit to the country, and that ‘on political grounds, and because of the close interaction between Poland’s political and economic prospects … some additional British credit should be provided as a contribution to the overall Western effort’.Footnote 74 At the time, the UK government was keen to support the development of pluralism in Polish society, which counteracted the socialist government.Footnote 75 It was also recognised that Poland was given ‘special treatment’,Footnote 76 aligning with the policy of positive discrimination under the Thatcher government whereby countries that adopted an independent attitude from the Soviet Union would be rewarded.

The outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in Poland brought publicity and an acknowledgement of the scale and complexity involved in debt rescheduling. It also led to a loss in confidence in other CMEA countries.Footnote 77 As a result of the crisis, Western banks, along with Soviet and some Arab banks, began withdrawing short-term funds and credit lines from CEE countries, thereby creating a liquidity crisis.Footnote 78 By contrast, UK banks took a more prudent attitude, recognising that the withdrawal of credits in the region could lead to more problems – or, in the words of a Barclays Senior Manager, would ‘rock the boat’.Footnote 79 Similarly, Lloyds bank identified that ‘containing and managing’ outstanding loans in Poland was a priority, and that although it would no longer seek further business in Romania, it would ‘maintain … relationships with the Foreign Trade Banks and continue to lend’ in other CMEA countries.Footnote 80 Midland bank adopted a more conservative attitude towards lending to CEE countries due to concerns over debt.Footnote 81 These attitudes are reflected in a government brief on Hungarian dealings with UK banks:

The attitude of UK banks is generally that they are prepared to maintain their current level of lending to Hungary but are reluctant to increase their exposure at this stage. When pressed, they point to the fact that other banks … were responsible for the withdrawal [of funds and credit lines] which caused the serious liquidity problems in 1981 and 1982.Footnote 82

Furthermore, UK banks actively made an effort to address the debt crisis in CEE by lobbying the UK government and the Bank of England on the need for an international coordinated approach to the crisis, exemplified by a conclusion to a 1981 Lloyds Group committee meeting: ‘The position in Poland was grave from the political and financial standpoints, which made it imperative that the U.K. and other western countries worked closely together on the problem’.Footnote 83

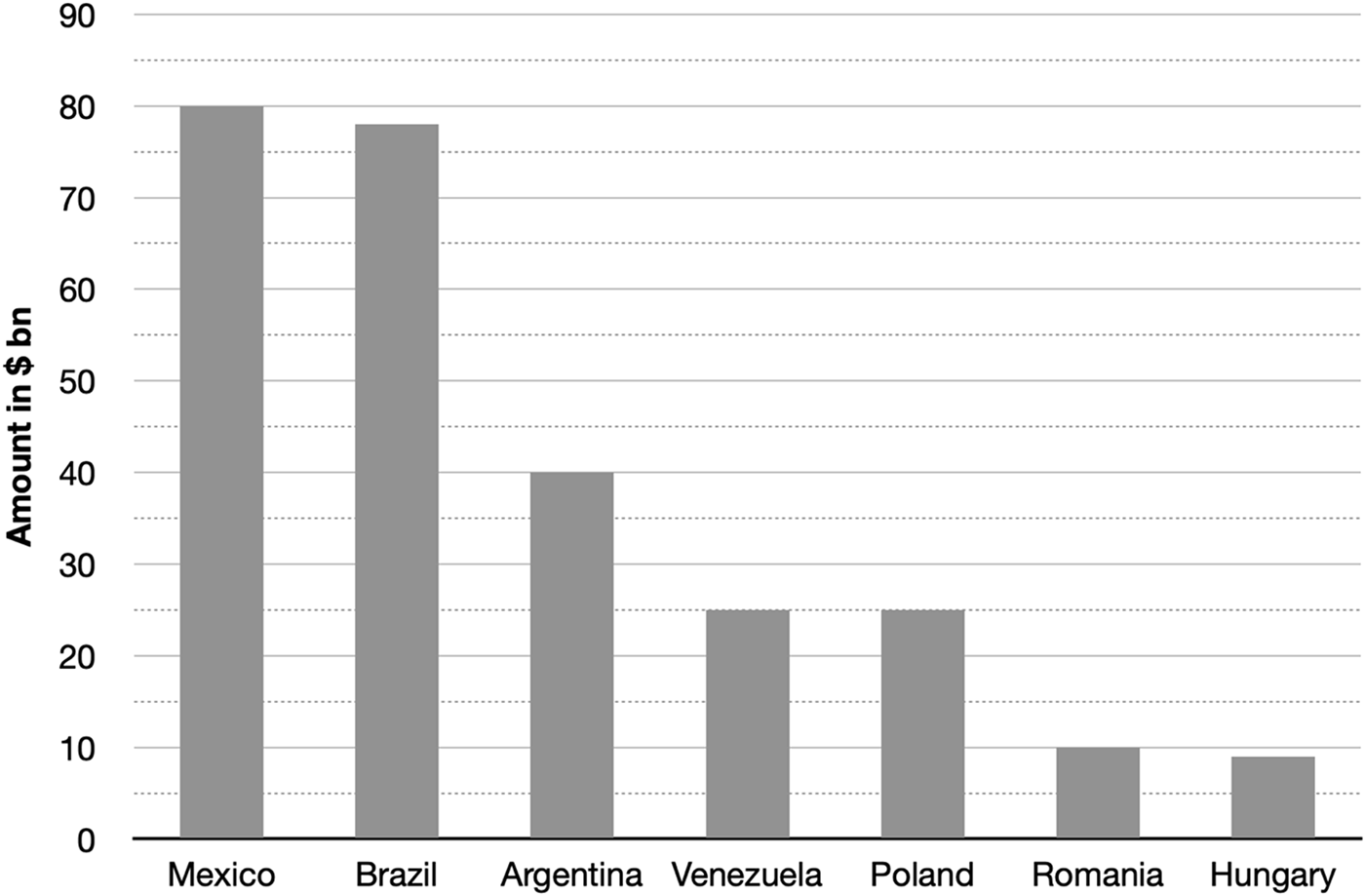

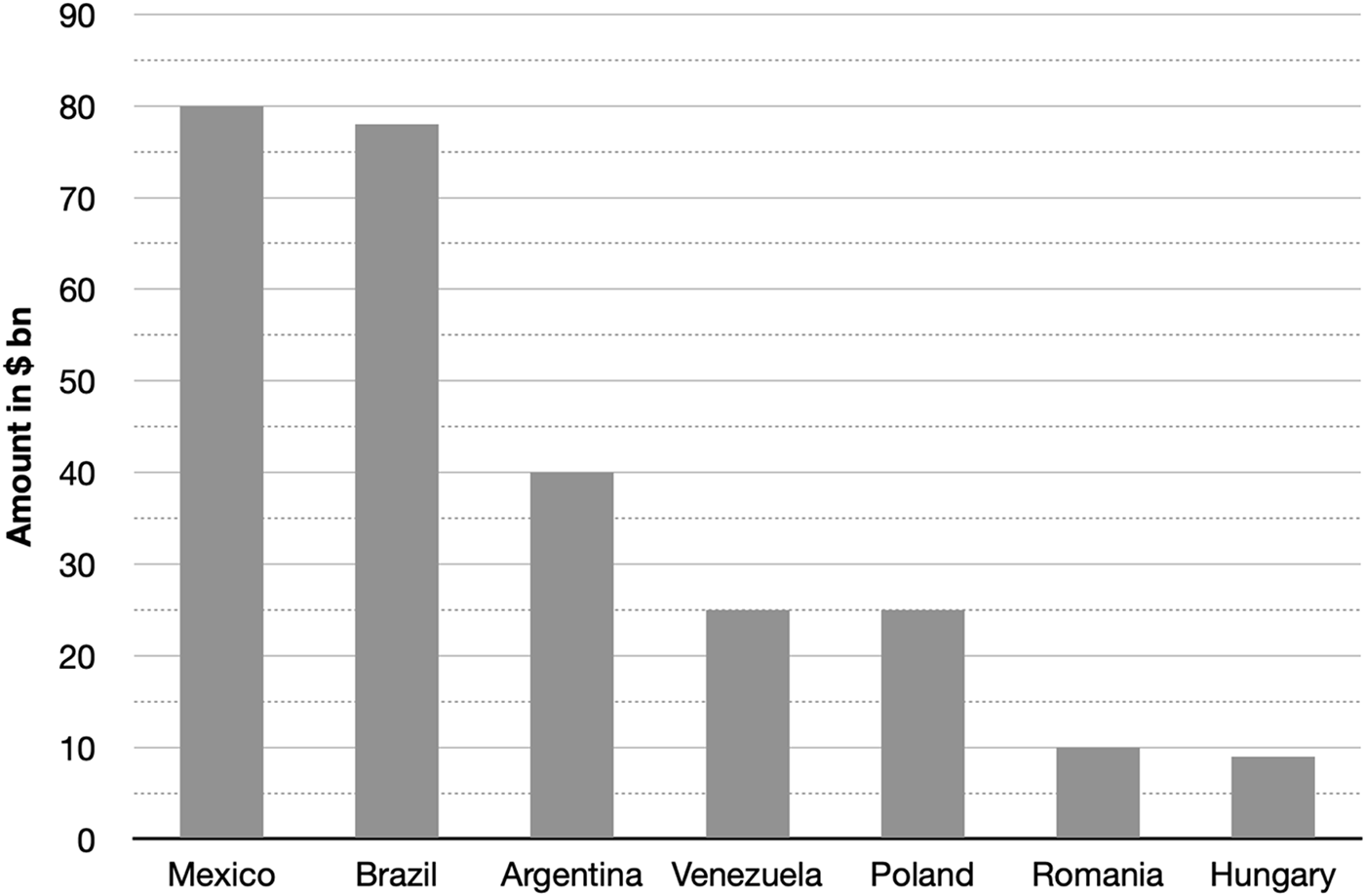

It is worth noting that the level of debt of CEE countries was significantly lower than Latin America. For comparison, in 1982, Mexico’s indebtedness was c. $80bn, followed by Brazil with c. $78bn, Argentina with c. $40bn and Venezuela with c. $25bn, whereas Polish indebtedness was c. $25bn followed by Romania with c. $10bn and Hungary with c. $9bn, as illustrated in Figure 1.Footnote 84

Figure 1. Approximate figures for Latin American vs. Central and Eastern European Sovereign Debt in 1982. Source: Rescheduling of Sovereign Debt, Institut International D’estudes Bancaires, 63rd Session, London (October 1982), report by Bevan, 15 Sept. 1982, BGA: 0080/2145, 32.

A report on sovereign debt by Timothy Bevan (Chairman of Barclays) reveals that Western banks were more concerned with Central and Eastern European debt than Latin American debt. There was some belief among western bankers that CEE countries ‘pose[d] the more dangerous challenge to the international financial system, because the Comecon economies have profound structural weaknesses’.Footnote 85 There were doubts whether these countries could bring their economic situation under control rapidly due to excessive bureaucracy, lack of an effective price mechanism and other economic inflexibilities typical of centrally planned economies.Footnote 86

UK and other Western banks were also concerned about the political aspect of debt rescheduling with CEE countries, since the political authorities of each country would have to accept and approve the rescheduling terms.Footnote 87 The political decision-making process in CEE was a slow and drawn-out affair compared to the decision-making process of their commercial authorities, which moved at a faster pace and added to the hesitancy of some Western banks in providing further credit to these countries.Footnote 88 In addition, there were also wider security concerns such as an increase in East–West tensions due to the civil unrest in Poland and Soviet intervention in countries such as Afghanistan.Footnote 89 Furthermore, as highlighted by Mourlon-Druol through the use of Barclays bank data, ECGD coverage on loans to Argentina, Brazil and Mexico was much lower than the coverage provided on loans to CEE: 1.89 per cent, 14.11 per cent and 0.98 per cent respectively. In comparison, ECGD coverage on loans to Poland, Hungary and Romania was 56.71 per cent, 27.14 per cent and 22.16 per cent respectively, as illustrated in Table 2.Footnote 90

Shortly after the outbreak of the crisis, leading UK banks collaborated to contain the effect of the sovereign debt crisis, forming a Sovereign Risk Committee, where they and the Bank of England would meet monthly to discuss developing countries’ sovereign debt and share information and data on debtor countries.Footnote 91 Its purpose was to formalise the relationship between UK banks for sharing information on sovereign debt, with the Bank of England acting as an observer. The Sovereign Risk Committee was set up as an independent initiative to avoid the leakage of information that could lead to panic and further complicate the sovereign debt situation of developing countries, which the Bank of England was keen to avoid.Footnote 92

Despite the scale of the crisis, the archives of Barclays, Lloyds and National Westminster Bank illustrate that the response of UK banks to the crisis was measured and generally optimistic. Barclays Senior General Manager Peter Leslie stated in a bank briefing that debtor countries, including those in CEE, would ‘return to good financial health as they have done in the past’, so long as the ‘necessary remedial action’ was taken – in other words, debt rescheduling.Footnote 93 A comparable tone is found in annual bank reports from this time. A statement by Lloyds bank Chairman Jeremy Morse in 1981 argues that while some indebted countries such as Poland were affected by political problems, overall risks were ‘generally well spread’ and that a domino effect of ‘default and collapse is unlikely’.Footnote 94 Similarly, a statement by National Westminster Chairman Robert Leigh-Pemberton in 1982 asserts that he believed the debt crisis could be resolved given the ‘goodwill and co-operation on the part of all those involved’.Footnote 95

UK banks were careful not to be seen as indifferent to the crisis. As Leslie stated: ‘it would be misleading to give the impression that Barclays, or indeed the international banking community as a whole, views the situation with complacency although … we do consider the risks to be containable’.Footnote 96 The calm approach and optimism shown by these UK bankers in the face of the considerable global economic challenge that confronted them could be explained by the fact that a portion of their loans to CEE were covered by the ECGD and a need to present a positive message to their customers and shareholders in their annual reports and bank briefings. However, debt rescheduling was also not a new phenomenon for banks. Leslie, writing in a 1982 Barclays newsletter, saw no reason for panic when developing countries resorted to debt rescheduling and notes the large number of countries that had previously rescheduled debt. He emphasises the importance for Western banks to maintain a level-headed approach and to continue supporting struggling countries in weathering the sovereign debt crisis as it was in their mutual interest to aid recovery:

Unlike commercial customers, countries always have time on their side to put their house in order … Since 1956 some 80 reschedulings have been experienced mostly from countries which are now regarded as healthy … The art that we and all the other banks have to practice is to keep those in trouble afloat so that they can win themselves the time for corrective action to take effect.Footnote 97

In spite of the reduction in appetite for foreign lending following the outbreak of the crisis, the UK government encouraged continued UK bank involvement in CEE for foreign policy reasons – even against some UK banks’ own commercial judgement. An example of this is evident in an internal Midland bank letter that states that despite the bank’s reluctance to increase its exposure in Central and Eastern Europe, in practice the bank could not ‘totally cease to lend, and any new loans we [Midland bank] feel obliged to make … will have to be matched by yet further reductions in existing lending’ and that the bank would have to resist ‘high-level pressure’, to avoid lending to what they deemed sensitive risk countries, such as Hungary.Footnote 98 In the case of Hungary, the UK government attached political importance to the country’s economic success and were keen to support the country through the debt crisis, while being ‘careful to avoid attempting to influence the banks directly in view of the risk that this would lead to allegations of Government interference or to demands for official guarantees for the loans’,Footnote 99 although from a political point of view the UK government would welcome the participation of UK banks in new lending.Footnote 100

While the UK government wanted to avoid applying direct pressure, it could exert indirect pressure in other ways to achieve its foreign policy goals, such as through the Bank of England. As noted in a UK Treasury paper, the Bank of England has a ‘role to play in passing Government views to the banks and vice versa’.Footnote 101

Indeed, despite their initial hesitance, UK banks would play a prominent role during the Hungarian sovereign debt crisis ‘after strong encouragement by the Bank of England’.Footnote 102 Such an example of this encouragement can be seen in one instance where Barclays, Lloyds, Midland and National Westminster banks were initially unwilling to participate in a syndicated loan to Hungary, but following the Bank of England Governor Gordon Richardson personally speaking to each of the banks’ chairmen, all four banks decided to contribute to the loan.Footnote 103 Altamura and Zendejas reveal that a similar situation occurred in Latin America as the UK government exerted pressure on National Westminster bank to continue lending to Brazil, despite the bank’s intentions to reduce their exposure.Footnote 104 Such examples show that the UK government was willing and able to exert its influence over UK commercial banks in pursuit of its foreign policy goals but also realised that this had to be done subtly, through indirect means.

While the UK government was willing to support Poland, Romania and Hungary during the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis, the case of Romania was more complicated. This was due to its political leadership under President Nicolae Ceausescu and his government’s attitude towards UK and other banks, which, as one UK government official put it, ‘could not have been better designed to destroy what little confidence remained in Western banking circles’.Footnote 105 As Romania struggled under its indebtedness, it approached the UK and other governments to request bilateral assistance, including rescheduling. The UK government was only willing to engage in multilateral rescheduling, but Ceausescu was unwilling to consider this approach.Footnote 106 The refusal to discuss and engage in debt rescheduling resulted in Romania losing access to new loans and the country amassing over one billion dollars of debt to foreign banks by the end of 1981. Furthermore, Romanian banks did not comply with international payment rules and mechanisms, which led to the deterioration of the International Monetary Fund’s confidence in the country’s authorities the same year.Footnote 107 UK banks became increasingly exasperated with Ceausescu’s approach, exemplified by one Midland bank executive expressing their frustration that ‘the immorality of the Romanians in some of their banking transactions over the last 6 months are even an embarrassment to their other Comecon partners, who are well aware of the shortcomings of the Romanian banking system’.Footnote 108

Shortly after the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis, the country adopted austerity measures that severely affected the living conditions of Romanian citizens, such as increased exports of consumer goods, including food and clothes, cuts to electricity and heating, reduction in social services and so on. While Romania did succeed in paying off its foreign debt in the spring of 1989, these measures led to widespread dissatisfaction with the Romanian regime and ultimately contributed to its downfall.Footnote 109

Conclusion

Bank–state relations from détente to the early 1980s are key to understanding the development and outbreak of, and response to, the CEE sovereign debt crisis. The emergence of détente drove the expansion of East–West political and economic relations, with both Western governments and banks pursuing their interests in CEE during this time. Western European governments were keen to maintain peace and stability in Europe and made an effort to increase contacts with CEE countries at all levels. It was hoped this would encourage them to move away from the Soviet Union and closer to Europe, making a united Europe possible.

Banks were searching for new markets abroad to do business, which would allow them to expand their international scope, prestige and client base and become more competitive in comparison to other domestic and foreign banks. The Cold War context and détente changed the way in which Western banks did business, as their home governments recognised the importance of banks in establishing East–West trade and financial links, which helped to break down Cold War divisions.

By focusing on the relationship between the UK government and UK banks during the development of the CEE sovereign debt crisis, this article shows how UK banks developed relations with CEE countries through visits, joint banking ventures and loans, and how the UK government supported these initiatives through the Department of Trade, UK embassies based in CEE and the Export Credit Guarantee Department, in pursuit of its foreign policy agenda.

The role of the ECGD during the development of the sovereign debt crisis is shown to be particularly important as it offered government guarantees on a portion of the loans granted by UK banks to CEE countries. These guarantees helped to mitigate the risk of incurring financial losses and therefore directed the flow of business to the region. Furthermore, the ECGD would grant these guaranteed credits for not only economic but also political rationales. In doing so, through the ECGD, the UK government indirectly encouraged UK banks to help finance its foreign policy towards CEE.

The article also demonstrates how the UK government and banks reacted to the development and outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in CEE. In particular, it shows how the UK government continued to encourage UK bank lending to CEE, for foreign policy reasons, using the Bank of England to apply indirect pressure in its role as a conduit between the banks and government.

A full understanding of the development and outbreak of the 1981–2 sovereign debt crisis cannot be complete without situating leading Western banks within the broader economic and political landscape of the time. Only through examining banks’ relationships with their governments and central banks, and their financial interactions with CEE countries, where the boundaries between state and market were increasingly blurred, can a comprehensive picture be achieved.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Sean Vanatta, Duncan Ross, Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol, Alastair and Andrew Cassell, and the three anonymous reviewers for their feedback and comments on earlier versions of this work. I would also like to thank the European University Institute who provided funding for archival research during my time as a Max Weber fellow, and the helpful bank archivists of Barclays, Lloyds, HSBC and NatWest. Files from the Bank of England were provided courtesy of the BoE archive. Finally, special thanks go to my dear friend Louis for his years of support and encouragement throughout the research and writing process, for which I will be ever grateful.