The study of the reciprocal relationship between political parties and the mass publicFootnote 1 has prompted two, related, research agendas. The first, advanced by spatial modellers and agenda-setting scholars, assesses how the mass public's policy positions and issueFootnote 2 priorities influence parties’ issue positions and attentionFootnote 3 (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Jennings & John, Reference Jennings and John2009; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016). The second research agenda analyses how parties reciprocally influence citizens’ issue positions and priorities, reporting consistent evidence that citizens take policy position cues from parties (Carsey & Layman, Reference Carsey and Layman2002; Milazzo et al., Reference Milazzo, Adams and Green2011). Yet there is less research on whether parties influence the public's issue attention beyond case studies on Canada (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002), Germany and Britain (Neundorf & Adams, Reference Neundorf and Adams2019) and the United States (Barbera et al., Reference Barbera, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019; Egan, Reference Egan2013).

The limited research on parties’ abilities to cue citizens’ issue attention is surprising, given scholarly interest in issue attention at the level of both parties (e.g., Green-Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2019; Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005) and mass publics (Meguid & Belanger, Reference Meguid and Belanger2008; van der Brug, Reference van der Brug2004; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005). These studies posit that parties strategically emphasise electorally advantageous issue areas (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge, Farlie, Daalder and Mair1983; Riker, Reference Riker1986), seeking to influence citizens’ issue priorities, and through this, their vote choices (Meguid & Belanger, Reference Meguid and Belanger2008; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). Yet, we lack systematic cross-national data on how strongly parties’ issue emphases are related to mass publics’ subsequent issue priorities, or within various sub-constituencies. To explore this issue, we assemble data on the levels (and level changes) of party attention across varying issue domains, along with national conditions pertaining to these domains, and use these data to predict changes in mass publics’ subsequent issue attention (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, pp. 208–226; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2013, pp. 58–63; Einsiedel et al., Reference Einsiedel, Salomone and Schneider1984; Erbring et al., Reference Erbring, Goldenberg and Miller1980; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1979; Singer, Reference Singer2011; Soroka, Reference Soroka2002; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005, pp. 562–567).

We analyse public issue attention across seven issue areas in 107 national elections in 13 western democracies between 1971 and 2021. The issue areas are unemployment, social welfare, the economy, the environment, immigration, crime and education. The countries are Austria, Australia, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. This is the most extensive cross-national, longitudinal study to date on parties’ abilities to cue public issue attention across diverse issue areas. We have entered the national election study of each of our 107 elections to build a new large-scale database on the public's issue priorities at elections via the ‘most important issue’ survey item (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005), which we will release with this publication as a major data source for research on the sources and evolution of mass publics’ issue priorities. We calibrate our data on public issue attention against data on parties’ issue emphases at elections, derived from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel, Werner and Schultze2021), along with objective measures of national conditions in each issue area such as the unemployment and economic growth rates, the crime rate, national pollution levels and immigration flows. We apply time-series, cross-sectional analyses to address the following questions: How much does party system issue attention predict the issue areas that the mass public subsequently prioritises? Does individual parties’ issue attention predict their partisan constituencies’ subsequent issue priorities? And, how strongly does public issue attention respond to objective national conditions? Given our data and aligned with the focus in the literature (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2019; Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005), we focus not on one-off topics that occupy the agenda on a short-term basis, but on the mass public's longer term issue priorities that vary across years on major issues such as the economy, the environment and immigration. In line with this, issue attention at the individual level is more fluid than a person's issue positions (Jones, Reference Jones1994), but the mass public aggregate issue attention still changes rather slowly (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1986; Green-Pedersen & Krogstrup, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Krogstrup2008). Our study generates three key findings.

First, we find little evidence that parties’ issue emphases lead issue attention in the mass public as a whole. Specifically, we uncover only weak and inconsistent evidence that the aggregate attention level to an issue area among the political parties in the system – as well as temporal changes in party system issue attention – predicts subsequent shifts in the mass public's issue attention. Indeed, these estimated relationships are so weak that we can rule out, at conventional levels of statistical significance, the proposition that any single party's issue attention meaningfully leads the public's issue attention, at least within the multiparty systems found in most western democracies. However, we explain below why the dominant parties in a two-party system – notably the US Democrats and Republicans – may be an exception to this generalisation.

Second, we estimate much stronger relationships between parties’ issue emphases and their supporters’ subsequent issue attention. We find that a focal party's issue attention (and its attention-based changes over time) reliably predicts subsequent shifts in aggregate issue attention among the party's supporters, that is, in its partisan sub-constituency. This pattern of attention-based partisan sorting may arise because partisans take ‘attention cues’ from their preferred party, or, alternatively, because citizens update their party support to align it with their pre-existing issue priorities.

Third, we find that aggregate issue attention – at the levels of the mass public and among partisan sub-constituencies – varies sharply with national conditions including the lagged levels (and level changes) of the unemployment and economic growth rates, the crime rate and immigration and pollution levels.

Our observational analyses are necessarily descriptive rather than causal, for while we can estimate how strongly parties’ issue attention and national conditions predict subsequent evolutions of the public's (and partisan sub-constituencies’) issue attention, we cannot fully rule out confounding by unobserved variables nor fully parse out the reciprocal relationship whereby citizens’ issue priorities may influence parties’ issue attention. Nevertheless, our findings identify leading indicators of public issue attention that bear on prominent theories of party competition and mass-elite linkages.

Our finding that no single party's issue emphases meaningfully lead the mass public's issue attention is at variance with a perspective advanced in recent empirical applications of the spatial models of elections (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Zur2024; Basu, Reference Basu2019), which estimate the electoral effects of parties focusing the general public's attention on electorally advantageous issue areas. In this regard, our finding that national conditions strongly predict subsequent public attention levels highlights the constraints that strategic parties may confront. To the extent this is a causal relationship, parties are largely ‘prisoners of national conditions’ in that the public's issue priorities respond strongly to these conditions, which parties have limited abilities to control in the short term. Our findings reflect positively on citizens’ capacities, suggesting that they perceive and react to longer term objective conditions, without being unduly moved by parties’ claims about which issues ‘actually’ matter. It seems normatively desirable that parties face pressure to respond to citizens’ issue concerns rather than single-mindedly seeking to shape these concerns. At the same time, our findings of attention-based partisan sorting suggest that parties may lead their supporters’ issue attention even as the wider public's attention does not follow parties’ issue emphases. This facet of our findings supports an important element of issue ownership theory (Meguid & Belanger, Reference Meguid and Belanger2008; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996).

How citizens’ issue priorities responds to parties’ issue emphases and to national conditions: Hypotheses

The relationship between issue attention in the party system and in the mass public: As noted above, there is limited research on how parties’ issue emphases influence citizens’ issue priorities. Soroka (Reference Soroka2002, pp. 72–98) analyses the evolution of the Canadian public's attention to eight issue areas across the period 1985–1996, finding that the parliamentary agenda (speeches, debates, bills) leads the public agenda on some issues, whereas national conditions lead the public agenda on others. Green-Pedersen & Krogstrup (Reference Green‐Pedersen and Krogstrup2008) find that immigration became a prolonged public issue priority in Denmark in the late 1990s at the point when statistics showed modest social integration of foreigners, and when parties began heavily politicising the issue. Along the same lines, US-based research finds that major partisan realignments, as with the race issue, reflect voters’ priority changes, not position changes (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1986). There is additional research analysing the correspondence between party issue attention and mass publics’ issue priorities, but mostly focused on the mass public's impact on parties, not vice versa (Egan, Reference Egan2013; Jennings & John, Reference Jennings and John2009; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016). The fact that parties represent the mass public's issue priorities does not automatically imply that the mass public also listen to the parties, and we therefore investigate this latter issue.Footnote 4

There are additional reasons to expect parties’ issue emphases to influence citizens’ issue attention. First, previous studies identify some fluidity in public issue attention, implying that citizens’ attention is to some degree ‘moveable’ (Jones, Reference Jones1994, 5–8). Stubager et al. (Reference Stubager, Kasper, Michael and Nadeau2021) document comparative evidence of occasionally sharp temporal shifts in mass publics’ longer term issue attention across varying domains, including the economy, the environment, public health, crime and immigration (see also Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Jennings and Wlezien2016; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2013, p. 57; Dennison, Reference Dennison2019; McCombs & Zhu, Reference McCombs and Zhu1995; Singer, Reference Singer2011). Second, while we lack experimental research that directly assesses parties’ abilities to cue citizens’ issue attention, a line of related experiments show that parties’ issue framing influences voters’ attitudes towards an issue (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2013; Slothuus & de Vreese, Reference Slothuus and de Vreese2010) along with their party evaluations (Lefevere et al., Reference Lefevere, Seeberg and Walgrave2020). These considerations motivate our first hypothesis:

The party system agenda hypothesis (H1): All else equal, greater party system attention to an issue area predicts greater subsequent public attention to the issue area.

The party system agenda hypothesis (H1) is interesting because, the above arguments notwithstanding, alternative considerations point in conflicting directions. First, extensive research documents that many citizens devote little attention to politics and are often poorly politically informed (e.g., Zaller, Reference Zaller1992), and thus may fail to receive party messages emphasising specific issue areas. Second, citizens receive their political information largely through the news media (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008), so that if the media reports an unrepresentative selection of party messages – or if the media downplays parties’ issue-based messages and instead focuses on politicians’ personalities and character (van Aelst et al., Reference van Aelst, Strömbäck, Aalberg, Esser, de Vreese, Matthes, Hopmann, Salgado, Hubé, Stępińska, Papathanassopoulos, Berganza, Legnante, Reinemann, Sheafer and Stanyer2017) – then even politically engaged citizens may receive a distorted picture of parties’ actual issue emphases (Haselmayer et al., Reference Haselmayer, Wagner and Meyer2017; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Haselmayer and Wagner2020). Third, citizens may discount parties’ arguments about which issue areas ‘really’ matter, reasoning that parties strategically emphasise electorally advantageous issue areas – as issue ownership theory posits – regardless of whether the issue is intrinsically important. In this regard, Fernandez-Vazquez (Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019, Fernandez-Vazquez & Theodoridis, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Theodoridis2020) documents that citizens discount parties’ advocacy of widely popular issue positions as insincere pandering designed to win votes. Fourth, scholars document a trend of partisan dealignment across western publics, whereby citizens express declining levels of trust in – and identification with – political parties (see, e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton2013). Thus, many citizens may view parties as non-credible sources for issue salience cues. These considerations suggest that the party system agenda hypothesis posits an upper limit for parties’ influence on public issue attention – albeit a hypothesis we see as well worth exploring, since ours is the first paper to analyse observational evidence across many countries pertaining to whether parties can systematically cue the general public's issue attention.

The relationship between parties’ issue emphases and their supporters’ priorities: Although the party system agenda hypothesis (H1) highlights the link between issue attention in the party system versus the mass public, there are reasons to expect stronger linkages at the levels of individual parties vis-à-vis their supporters, that is, their partisan constituencies. First, partisans are far more attentive to – and trusting of – their own party's issue statements than of rival parties’ statements (Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). In this regard, Barbera et al. (Reference Barbera, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019, fig. 2) find that US legislators lead their supporters’ issue attention much more strongly than they lead the general public's attention, while Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2014) document that when European parties announce a policy shift, their core supporters typically receive their in-party's communication and update their perceptions of the party's position, whereas the general public does not. Recent studies using experimental (Barber & Pope, Reference Barber and Pope2023) and quasi-experimental (Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021) designs present evidence that partisans take policy position cues from their party's elites. With respect to issue emphasis, Neundorf & Adams (Reference Neundorf and Adams2019) analyse the evolution of German and British partisans’ issue priorities over time, concluding that partisans take ‘issue salience cues’ from their preferred party by adjusting their issue priorities to match their party's long-term issue emphases in the domains of the economy, crime, immigration, and the environment. Moreover, these authors detect evidence that citizens also reciprocally update their party support to match their pre-existing issue priorities. These reciprocal processes imply that we should observe partisan sorting with respect to partisan constituencies’ issue attention. That is, when a party increases its emphasis to an issue then its pool of supporters should display greater collective attention to the issue, first because the party's pre-existing supporters increase their attention to the issue (an issue emphasis cueing effect), second because other citizens with pre-existing attention to the issue decide to affiliate with the party (a partisan updating effect).

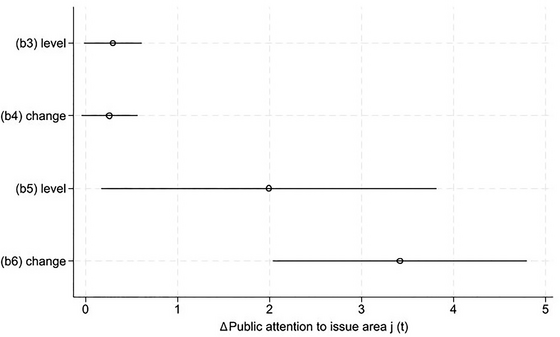

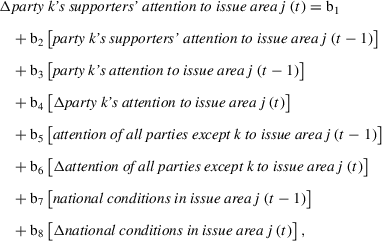

Figure 2. The prediction of a party's issue attention on its partisan constituency's attention across seven issues in 13 countries, 1971–2021. Note: The graph is based on the estimation in Appendix, Table A10, of the Supporting Information, which employs an error-correction model with country-party-issue fixed effects and panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses. Horizontal lines show 95% confidence intervals.

In western multiparty democracies, where even the largest parties rarely surpass 40 per cent of the popular vote and where many citizens are non-partisan, each party's sub-constituency of supporters is typically a small fraction of the total electorate. Yet political elites plausibly view their core supporters as their party's lifeblood, relying on this sub-constituency to contribute disproportionate shares of scarce resources including financial donations along with campaign and organisational support (Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). For these reasons, elites are likely to place special emphasis on their supporters’ issue priorities. These considerations motivate our second hypothesis:

The partisan sorting hypothesis (H2): All else equal, the more a party emphasises an issue area, the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent attention to the issue.

We see a stronger theoretical rationale for the partisan sorting hypothesis (H2) than for the party system agenda hypothesis (H1) because the conflicting considerations we raised above with respect to H1 – namely, that many citizens are politically disengaged and/or perceive parties as non-credible source cues about issue importance – have less force at the level of parties’ relationships with their own supporters. Compared with non-partisans, partisans display higher levels of political engagement and information (e.g., Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002), and as discussed above, partisans are disproportionately attentive to, and trusting of, their preferred party's communications.

The effects of national conditions: Finally, as a yard stick to assess the influence of party issue emphases on citizens’ attention, we also estimate the impact of real-world conditions. Condition changes such as the global economic recession beginning in 2008, and the European refugee crisis beginning in 2015, were associated with sharp upticks in public attention to the economy and to immigration/refugee issues, respectively (see, e.g., Stubager et al., Reference Stubager, Kasper, Michael and Nadeau2021). Meanwhile, the Covid-19 pandemic has prompted citizens to prioritise public health, while the Russian invasion of Ukraine focuses public attention on defence and foreign affairs. In addition to these examples of cross-national condition changes, conditions also differ between countries in terms of economic growth rates, crime, terrorist attacks, and so on. Previous research confirms that citizens’ personal experiences and real-world conditions influence the public's issue priorities (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, pp. 208–226; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2013, pp. 58–63; Einsiedel et al., Reference Einsiedel, Salomone and Schneider1984; Erbring et al., Reference Erbring, Goldenberg and Miller1980; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1979; Singer, Reference Singer2011; Soroka, Reference Soroka2002; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005, pp. 562–567). These considerations motivate our final hypothesis:

The national conditions hypothesis (H3): All else equal, national conditions predict subsequent issue attention levels in the mass public and within partisan constituencies.

The national conditions hypothesis (H3) is important because it allows us to compare the relative degrees to which national conditions and parties’ issue emphases predict subsequent levels of public issue attention. Furthermore, given that national conditions plausibly predict both parties’ issue emphases and public issue attention, failure to control for these conditions would introduce omitted variable bias in our estimates of how public attention is related to parties’ issue emphases. We have no doubt that national conditions also influence public issue priorities via their effect on political parties’ issue emphases (e.g., Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Borghetto and Seeberg2023, Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Mortensen, Green‐Pedersen and Seeberg2023), but leave this finer exploration to future studies.

Data on party issue attention, mass public issue attention and national conditions

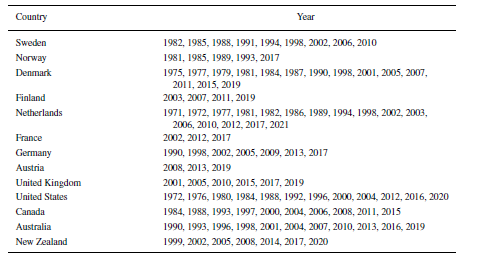

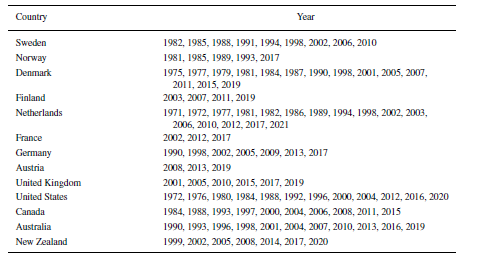

We evaluate our hypotheses by analysing data on parties’ and the mass public's issue attention and national conditions in 13 western democracies and 107 national election surveys across seven issue areas between 1971 and 2021. These are the countries and issue areas where data are available. The countries are Australia, Austria, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. This is a diverse selection that includes presidential, semi-presidential and parliamentary democracies; federal and unitary systems; and countries with different voting systems and numbers of parties. Table 1 reports the country-election years in our study. Note that while these election studies begin in the 1970s in Denmark, the Netherlands and the United States, they begin after 1980 in the remaining countries and after 2000 in Austria, Finland, France and the United Kingdom. This reflects the availability of survey data that include cross-nationally and temporally comparable questions on citizens’ issue attention, discussed below. The election-based data resonate with our focus on the parties’ and mass publics’ long-term issue priorities. We analyse 76 parties in total, an average of 5.8 per country. Section I in the Supporting Information memo lists these parties. The seven issue areas are the economy, education, the environment, crime, social welfare, unemployment and immigration. These are the issue areas for which we have sufficient survey data on citizens’ issue attention to meaningfully evaluate our hypotheses. However, as discussed below, we lack relevant survey data on one or more of these issue areas in some of the country-election years in our study, so that for some issue areas we have less than 107 usable data points. We have 677 observations for our analyses of the party system issue agenda. Appendix Section VII (of the Supporting Information) lists, for each issue area in our study, the set of country-election years included in our empirical analyses.

Table 1. Country election-years included in the analysis

Note: The table lists the country-election years included in our study of the relationship between parties’ issue emphases, national issue conditions and the public's issue priorities. As discussed in the text, this list reflects the availability of cross-nationally and temporally comparable surveys on the public's issue priorities.

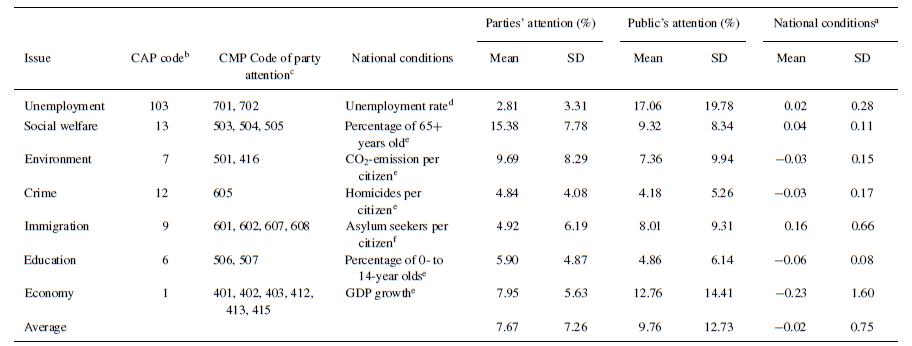

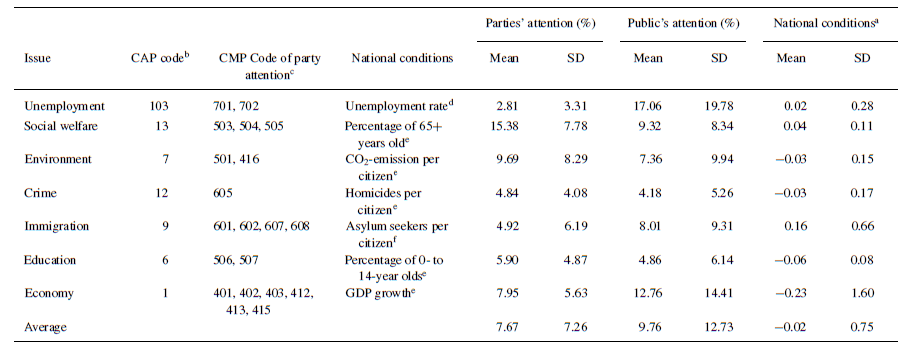

We measure parties’ issue emphases at each election in our study using CMP codings of party election manifestos. This is the only dataset that provides comparable party issue emphasis measures over time for multiple parties across multiple issues in a large number of countries (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel, Werner and Schultze2021). While acknowledging debates on the constraints of the data (Gemenis, Reference Gemenis2013), we follow previous studies that rely on CMP codings to estimate parties’ issue emphases (Abou-Chadi et al., Reference Abou‐Chadi, Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2020; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Neundorf & Adams, Reference Neundorf and Adams2019). Parties use their manifestos to communicate their issue emphases and positions to the public during national election campaigns, and research finds that party elites feel constrained to campaign on the themes developed in their manifestos (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2011), so that party manifestos plausibly provide reasonable proxies for parties’ overall issue emphases. In robustness checks described below, we explore the implications of possible slippage between our CMP-based measures and parties’ true or underlying issue emphasis levels. Table 2 presents the CMP codings for each issue area we study, along with the mean and standard deviations of parties’ coded attention to each area, averaged across the parties and elections in our study. We see that of the seven issue areas we analyse, parties were coded as devoting the most attention to social welfare (about 15 per cent of their coded manifesto statements) followed by the environment (about 9 per cent of coded statements), while parties devoted the least attention to the areas of crime, immigration and unemployment (less than 5 per cent coded statements in each issue area).Footnote 5

Table 2. Party attention, public attention and national conditions across issues

Note: aFor national conditions, we standardise the condition levels as mean-adjusted deviations from the mean on each indicator in each country. Sources: bComparative Agendas Project. cComparative Manifesto Project. dOECD. eWorld Bank. fUNHCR.

To evaluate the hypothesis that greater party system attention to an issue predicts greater subsequent public attention to the issue (H1), we calculate the overall party system issue agenda as the mean party attention to each issue area in a country-election year, averaged across all parties represented in parliament (cf. Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010), based on the CMP codings of the proportion of each party's manifesto devoted to each issue area. We categorise the CMP codings into issue areas using the Comparative Agendas codebook (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Breunig and Emiliano2020). We weight each party's issue attention by its size (vote share), given that larger parties receive more extensive media coverage (Green-Pedersen et al., Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and Thesen2017; Haselmayer et al., Reference Haselmayer, Meyer and Wagner2019). The variable [party system attention to issue area j (t)] denotes the weighted mean party system attention to issue area j in the election year t based on the CMP codings for that country-year.Footnote 6 The variable [party k's attention to issue area j (t)] denotes a specific party k’s attention to issue area j in election year t. This variable pertains to our partisan sorting hypothesis (H2), that the more a party emphasises an issue area the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent attention to that area.

To measure the mass public's issue attention, we extracted data on the ‘most important issue’ survey item or its close equivalent the ‘most important problem’ (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005) for each of the 107 national election surveys. The ‘most important issue’ survey item is a standard variable in election studies across many countries (Jennings & John, Reference Jennings and John2009) and has been used in previous research on public saliency (e.g., Soroka, Reference Soroka2002, p. 78; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2013, pp. 57–63; Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, pp. 208–226; Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Jennings and Wlezien2016). The survey item is typically phrased as ‘What is the most important issue in this country in this election?’.Footnote 7 In almost nine out of ten of our national election studies, an open-ended answer is provided where the respondent can report her issue. In about one in ten studies, including New Zealand in 1999, Germany in 2005 and Australia, a closed list is applied that asks the respondent to pick an issue on a list. For our analysis, we aggregate the percentage of survey respondents that mentions an issue in a given election. To avoid sampling error due to small samples in our analyses of the partisan sub-constituencies that we analyse for the partisan sorting hypothesis (H2), we only include estimates based on at least 50 respondents on an issue. As we discuss further for the open-ended answers in Appendix Section III (of the Supporting Information), we categorise issues using the Comparative Agendas codebook (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Breunig and Emiliano2020). Section III in the Supporting Information memo presents the question wording and discusses issues of cross-national and temporal comparability. The variable [public attention to issue area j (t)] denotes the proportion of respondents in the election survey administered in year t who identified issue j as the most important problem facing the country, computed as a proportion of all respondents who provided valid answers to the ‘most important problem’ survey item. Table 2 above reports the mean values and standard deviations of public attention for each issue area in our study. We see that public attention was greatest, on average, with respect to unemployment (a mean proportion of about 0.17) and least with respect to crime and education (about 0.05 each). The proportion of public attention to each issue area averages about 0.11, implying that the overall proportion of attention that publics collectively devoted to the seven issue areas in our study was slightly below 0.8, that is, the proportion of attention to areas outside our study was slightly above 0.2.

The election-year surveys that we analyse also elicited respondents’ party support. If the survey was prior to the election, it typically asked which party the respondent intended to vote for on a closed list. If the survey was collected immediately after the election, it asked respondents which party they voted for on a closed list. The variable [party k's supporters’ attention to issue area j (t)] denotes the proportion of party k’s self-identified supporters in year t who listed issue j as the most important problem facing the country, as a proportion of k’s supporters who provided valid responses. This variable is relevant to our partisan sorting hypothesis (H2), that the more a party emphasises an issue the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent aggregate attention to the issue. We use the CMP codebook to code the parties in the election studies to match the voter and party data at the party level. Ideally, we would measure the degree of a respondent's partisanship using a party identification measure. However, this is not uniformly available across our large number of national election studies, and research concludes that partisanship and vote choice are closely related (Dinas, Reference Dinas2014; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber and Washington2010).

To test the national conditions hypothesis (H3), that national conditions predict subsequent aggregate attention in the mass public and within partisan constituencies, we rely on national-level indices that are relevant to each of our seven issues areas, collected through the OECD, the World Bank and the UN to ensure consistency across countries and over time. We include standard problem indicators that have been used in other work (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002, pp. 77–78; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2013; Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005), and are measured annually as proxies for the problem level. Although the unemployment rate is an obvious indicator for the unemployment issue area, and the GDP growth rate is a plausible indicator for the overall economic issue area, indicators for other areas are less obvious. Our eventual selections, listed in Table 2 above, were as follows: for crime, the national homicide rate; for the environment, the CO2-emission level per citizen; for education, the proportion of zero-to-14-year-olds in the population; for social welfare, the proportion of citizens aged 65+; for immigration, the proportion of asylum seekers per citizen. Section IV in the Supporting Information memo provides a more detailed discussion and justification of our choices of issue area indicators. We are under no illusion that our indicators fully capture all relevant national conditions in these issue areas, and below we report robustness checks to assess possible consequences of ‘conceptual slippage’ between our indicators and the relevant national conditions in the areas we analyse. Moreover, we report supplementary analyses in Appendix Section VIII (of the Supporting Information) using alternative measures of national conditions.

To make the indicators comparable across countries, we measure them per capita, and we standardise the condition levels as mean-adjusted deviations from the mean on each indicator in each country. We also scale the indicators so that higher values in each area denote conditions that prompt greater public attention to the area, so that higher values are associated with lower GDP growth but with higher unemployment, crime and CO2 emission levels, and with larger proportions of asylum seekers, school-age children and senior citizens. The variable [national conditions in issue area j (t)] is thus a standardised measure of the national condition level in issue area j in the current year t.

Hypothesis tests

Model estimation

To evaluate our hypotheses, we estimate statistical models designed to predict the public's levels of attention to different issue areas. For these analyses, we estimate error-correction models (ECMs), in which the current time (t) change in the variable of interest (the dependent variable) is modelled as a function of the lagged level of that variable and the current changes in and lagged levels of the key independent variables. We spell this out for our estimations in Models 1 and 2 below. With data for multiple parties, issues, elections and countries, one advantage of the ECM framework is that the dynamic structure of the data is not specified beforehand – error correction models are suitable for both stationary and integrated data (De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008, p. 199). The intuition behind the model is that changes in the independent variables constitute a shock to the equilibrium, which the dependent variable then will return to over a period of time defined by the size of the lagged level of the dependent variable. A particularly attractive feature of the error correction model, apart from its ability to handle both stationary and integrated data, is that it estimates both short-term and long-run effects. The short-term effect is captured by the change in the independent variable, or β 4 in Model 1 below. The long-run effect is defined as the ratio between the coefficient of the lagged level of the independent variable of interest and the lagged dependent variable; that is, β 3/β 2 in Model 1. For our purpose, the long-run effects are most relevant because these are the ones that have a lasting impact on the dependent variable (De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008, p.191). The choice of this estimation technique allows us to maximise comparability with previous studies on public saliency that also rely on error correction models (cf., e.g., Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Jennings and Wlezien2016; Jennings & John, Reference Jennings and John2009). A Hausman test indicates that the random effects estimator is biased and inconsistent (χ 2 = 1964.7; p < 0.000), so we include fixed effects in our model estimation at the issue, party and country levels. We estimate the regression with panel-corrected standard errors and control for time by including a year variable.

To evaluate the party system agenda hypothesis (H1), that greater party system attention to an issue area predicts greater subsequent attention to the issue in the mass public, we estimate the parameters of the following specification:

[Model 1]

$$\begin{eqnarray*} \mathrm{\Delta}\textit{public attention to issue area}\hspace*{0.28em}j\left(t\right)&=&{\mathrm{b}}_{1}+{\mathrm{b}}_{2}\left[\textit{public attention to issue area}\hspace*{0.28em}j\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{3}\left[\textit{party system attention to issue area j}\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{4}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party system attention to issue area j}\left(t\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{5}\left[\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{6}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\left(t\right)\right], \end{eqnarray*}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray*} \mathrm{\Delta}\textit{public attention to issue area}\hspace*{0.28em}j\left(t\right)&=&{\mathrm{b}}_{1}+{\mathrm{b}}_{2}\left[\textit{public attention to issue area}\hspace*{0.28em}j\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{3}\left[\textit{party system attention to issue area j}\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{4}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party system attention to issue area j}\left(t\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{5}\left[\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\left(t-1\right)\right]\\ && +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{6}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\left(t\right)\right], \end{eqnarray*}$$

where the dependent variable [∆public attention to issue area j (t)] denotes the change in the public attention level to the issue area j at the current time period t compared to the previous period (t – 1).Footnote 8 A significantly positive estimate on the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable will support the party system agenda hypothesis (H1), since this will denote that higher lagged levels of party system attention to the issue area j predict more positive changes in the public's attention to issue j at time t. H1 also implies a positive estimate on the [∆party system attention to issue area j (t)] variable, denoting that increasing (decreasing) party system attention to issue j between times (t – 1) and t predicts increasing (decreasing) public attention to the issue across this period. Note, however, that this relationship is also consistent with the reciprocal causal process whereby party elites adjust their issue attention in response to changing issue attention in the mass public, not vice versa. Note also that the dynamic estimation is based on changes by design controls for time-invariant confounders such as political institutions and culture.

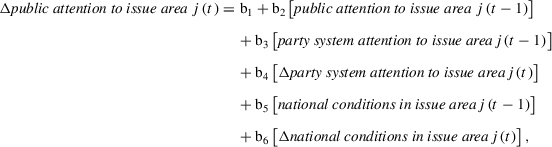

To evaluate the partisan sorting hypothesis (H2), that the more a party emphasises an issue the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent aggregate attention to the issue, we estimate the parameters of the following specification:

[Model 2]

$$\begin{eqnarray*} &&\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party k's supporters' attention to issue area j}\ (t)={\mathrm{b}}_{1}\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{2}\left[\textit{party k's supporters' attention to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{3}\left[\textit{party k's attention to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{4}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party k's attention to issue area j}\ (t)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{5}\left[\textit{attention of all parties except k to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{6}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{attention of all parties except k to issue area j}\ (t)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{7}\left[\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{8}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\ (t)\right], \end{eqnarray*}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray*} &&\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party k's supporters' attention to issue area j}\ (t)={\mathrm{b}}_{1}\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{2}\left[\textit{party k's supporters' attention to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{3}\left[\textit{party k's attention to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{4}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{party k's attention to issue area j}\ (t)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{5}\left[\textit{attention of all parties except k to issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{6}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{attention of all parties except k to issue area j}\ (t)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{7}\left[\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\ (t-1)\right]\\ &&\quad +\ {\mathrm{b}}_{8}\left[\mathrm{\Delta}\textit{national conditions in issue area j}\ (t)\right], \end{eqnarray*}$$

where the dependent variable [∆party k's supporters’ attention to issue area j (t)] denotes the change in the partisan constituency k’s aggregate attention to issue area j between time (t – 1) and t. A significantly positive estimate on the [party k's attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable will support the partisan sorting hypothesis (H2), denoting that higher lagged levels of party k’s attention to the issue area j predict more positive changes in its partisan constituency's attention to issue k, while controlling for the partisan constituency's lagged issue attention. H2 also implies a positive estimate on the [∆party k's attention to issue area j (t)] variable, although this relationship is also consistent with the reciprocal causal process whereby party elites adjust their issue attention in response to changes in their partisan constituency's issue attention. Note that we control for the issue attention of all other parties in the system by including the variables [attention of all parties except k to issue area j (t – 1)] and [∆attention of all parties except k to issue area j (t)], because these other parties’ issue attention may influence party k’s supporters attention.

Finally, the national conditions hypothesis (H3), that national conditions predict subsequent aggregate issue attention in the mass public and within partisan constituencies, implies significantly positive estimates on the [national conditions in issue area j (t – 1)] and the [∆national conditions in issue area j (t)] variables, in both Models 1 and 2. These positive coefficients would denote that higher lagged levels – and level changes – in the national condition associated with an issue area j predict increases in citizens’ attention to issue j, in analyses over the entire public (Model 1) and over partisan sub-constituencies (Model 2).

Results

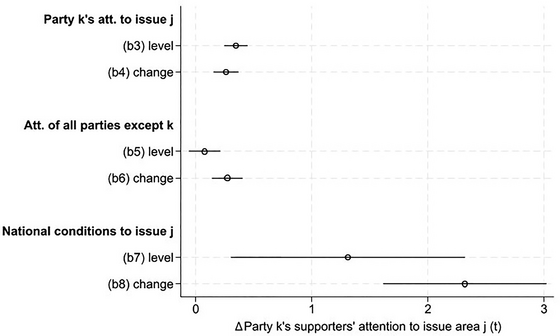

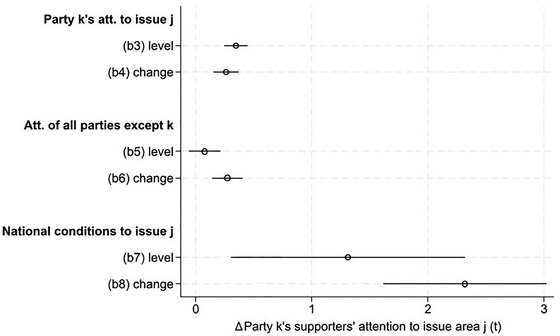

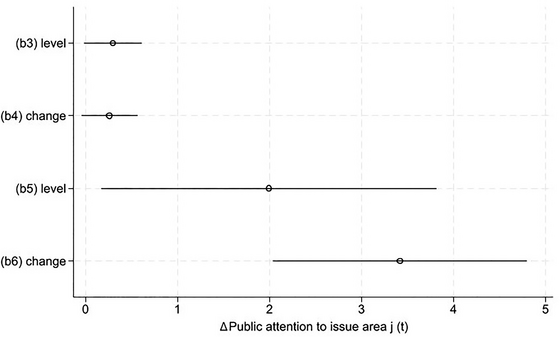

Analyses on mass publics (H1): Figure 1 reports the parameter estimates on the specification given by Model 1 above, which is relevant to the party system agenda hypothesis (H1), that greater party system attention to an issue area predicts greater subsequent longer term public attention to the issue. Our parameter estimates only weakly and inconsistently support H1: the estimate on the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable is positive but only marginally significant (p < 0.10), as the upper horizontal line in Figure 1 intersects 0 on the x-axis. Moreover, even if this positive relationship were shown to be causal, the point estimate on the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable, +0.30, implies a modest substantive impact whereby a one per cent increase in party system attention to an issue area prompts a subsequent short-term (from one election to the next) increase of about one third of one percentage point in the public's attention to that issue, all else equal. The estimate on the [∆party system attention to issue area j (t)] variable is of almost similar magnitude (+0.26) and marginally significant (p < 0.10), providing only weak evidence that public issue attention changes track party system issue attention changes over time. Recall, however, that this latter relationship may reflect the reciprocal causal process whereby parties adjust their issue attention in response to changing public issue attention, not vice versa.

Figure 1. Predicted changes in the mass public's issue attention as a function of party system issue attention and national conditions, across seven issues in 13 countries, 1971–2021. Note: The graph is based on the estimation in Appendix, Table A9, of the Supporting Information, which employs an error-correction model with country-party-issue fixed effects and panel-corrected standard errors. Horizontal lines display 95% confidence intervals.

The above estimates provide little reason to accept the party system agenda hypothesis (H1), and in fact they provide considerable evidence that most parties, by themselves, do not meaningfully lead the mass public's issue attention. To see this, note that in Model 1 we estimate the predictive power of overall party system issue attention, so that the degree to which any single party's issue attention leads public attention must be less than that for all parties combined. For instance, the issue attention of a moderately sized party k with a 20 per cent vote share is weighted at 0.2 in our weighted party system issue attention measure, so that a one-percentage-point increase in party k’s attention to issue area j at time (t – 1) increases the value of the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable by only 0.2. Thus the point estimate on the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable, +0.30, implies that a one per cent increase in party k’s lagged attention to an issue area predicts a subsequent short-term increase of less than one-seventeenth of one percentage point in the public's attention to that issue area, all else equal.Footnote 9 Even if the true value of the coefficient on the [party system attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable is two standard errors above its point estimate, a one per cent increase in party k’s lagged attention to issue j would predict a subsequent public issue attention increase of barely one-tenth of one percentage point.Footnote 10 Such an increase seems substantively trivial. And while the issue attention of larger parties – notably the dominant Democratic and Republican parties in the US two-party system – will more strongly predict subsequent public issue attention, in many western democracies even the largest parties typically win only about one-third of the popular vote. Hence our estimates provide strong evidence that, in many western party systems outside the United States, individual parties’ issue attention levels do not meaningfully lead issue attention in the mass public as a whole, while all parties combined may at most modestly lead public issue attention. We discuss this not entirely unexpected null finding in the conclusion.

By contrast, the significantly positive estimates in the bottom part of Figure 1 on the [national conditions in issue area j (t – 1)] and the [∆national conditions in issue area j (t)] variables support the national conditions hypothesis (H3), denoting that higher lagged levels – and level changes – in the national condition associated with an issue area predict increases in the mass public's longer term attention to the issue area, all else equal. Recall that the national conditions variables are standardised, so that the estimate on the [national conditions in issue area j (t – 1)] variable, +1.99 (p < 0.05), denotes that a one unit mean-adjusted deviation from the mean (μ = 0.02, σ = 0.75) increase in the lagged level of the national condition associated with issue area j predicts a subsequent rise of roughly two percentage points in the proportion of the mass public that identifies issue area j as the most important problem, all else equal. And, the estimate on the [∆national conditions in issue area j (t)] variable, +3.42 (p < 0.01), denotes that a one unit mean-adjusted deviation change from the mean in the national conditions on issue j predicts a rise of roughly 3.5 percentage points in the mass public's attention to issue area j (all else equal). Note, moreover, that these are the estimated short-term or immediate effects of national conditions. The estimated long-term effects are even larger, that is, a one-standard-deviation rise in the lagged national condition level pertaining to issue area j predicts a subsequent long-term increase in public attention to issue area j of close to four percentage points, while a one-standard-deviation change in the value of the [∆national conditions in issue area j (t)] variable predicts a change in public attention to issue j of over six percentage points.Footnote 11

Finally, the coefficient on the [public attention to issue area j (t – 1)] variable, –0.54 (p < 0.01), implies a strong pattern of regression to the mean in public issue attention (not reported in Figure 1, but in Appendix, Table A9, of the Supporting Information): when public attention to an issue area j is higher at a given time period, public attention to this issue area tends to decline in the subsequent time period, all else equal.

Overall, the estimates reported in Figure 1 suggest that the mass public's attention to any given issue area significantly increases when national conditions in that area become more severe, but that party system issue attention only weakly and inconsistently leads the public's issue priorities. To the extent that these patterns reflect causal processes, they imply that party elites have limited abilities to set the ‘terms of the debate’ during national election campaigns by emphasising specific issue areas through the party system agenda, but are instead largely prisoners of national conditions.

Analyses on partisan sorting (H2): Figure 2 reports the parameter estimates on the specification given by Model 2 above, which is relevant to the partisan sorting hypothesis (H2) that the more a party emphasises an issue area the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent attention to that issue area. Because our unit of analysis here is at the level of partisan constituencies rather than the entire mass public, we have many more observations, allowing us to estimate the relevant relationships more precisely.Footnote 12 Our parameter estimates strongly and consistently support H2: the estimates b 3 and b 4 on the [party k's attention to issue area j (t – 1)] and [∆ party k's attention to issue area j (t)] variables are positive and significant, so that we accept the hypothesis that higher lagged levels of a party's attention to an issue area (or temporal changes in the party's issue attention) the greater its partisan constituency's subsequent attention to that area (H2). The point estimate on the [party k's attention to issue area j (t)] variable, +0.26 (p < 0.01), implies that a one per cent increase in a party's lagged issue attention predicts a subsequent short-term increase of about 0.3 percentage points in its supporters’ aggregate attention to the issue, all else equal. The predicted long-term increase is nearly 0.5 percentage points.Footnote 13

By contrast, we find no evidence that a partisan constituency k’s issue attention is related to the lagged attention of other parties in the system besides party k: the coefficient b 5 on the [attention of all parties except k to issue area j (t – 1)] variable is near zero (+0.08) and statistically not significant. This provides strong evidence that individual parties’ issue attention does not meaningfully lead rival party supporters’ issue attention: Even if the true value of the coefficient on the [attention of all parties except k to issue area j (t – 1)] variable is two standard errors above its point estimate of +0.08, a one per cent increase in a medium-sized (20 per cent vote share) party k’s lagged attention to issue j predicts a subsequent rise in attention to issue j of each of its opponents’ partisan constituencies of less than one twentieth of one percentage point, all else equal.Footnote 14

Our parameter estimates on partisan sub-constituencies continue to strongly and consistently support the national conditions hypothesis (H3): the significantly positive estimates b 7 and b 8 on the [national conditions in issue area j (t – 1)] variable (+1.31, p < 0.01), and the [∆national conditions in issue area j (t)] variable (+2.32, p < 0.01), denote that higher lagged levels – and level changes – in the national conditions associated with issue area j predict subsequent increases in the partisan constituency's attention to the issue, all else equal. The point estimates on these coefficients imply that one-standard-deviation changes in these variable values predict short-term attention increases in the partisan constituency's aggregate attention to the relevant issue area of one to two percentage points, and long-term increases of two to three percentage points.

In toto, we find that national conditions relating to the economy, social welfare, immigration, education, crime and the environment strongly predict subsequent issue attention levels in the mass public and among partisan constituencies. By contrast, we find only weak and inconsistent evidence that party system issue attention predicts the mass public's subsequent issue attention. We do, however, estimate that parties’ issue emphases lead issue attention among the sub-constituency of their own partisans, even as parties do not meaningfully lead issue attention in the wider public beyond their supporters.

Robustness checks

We performed several robustness checks, which we present and discuss in Appendix Section VIII (of the Supporting Information). First, because citizens plausibly access much pertinent information about national conditions and party issue attention via media reports (Behr & Iyengar, Reference Behr and Iyengar1985; McCombs, Reference McCombs2004), we controlled for possible effects of media issue attention (see Model 5 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information). Next, we controlled for the length of time that had elapsed since the previous election (see Model 2 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information). We then controlled for whether our survey-based issue attention measure employed the ‘most important problem’ version or the ‘most important issue’ version of the question (see Model 4 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information), and for whether the answer format was closed- or open-ended (see Model 3 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information), factors that may affect survey responses (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005). With respect to the former issue, we also estimated model coefficients on the ’most important issue’ responses only (see column 6 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information). Next, we re-estimated our models using alternative national condition measures including pupil-to-teacher-ratio on education, the total migration stock on immigration, and the Gini coefficient on welfare (see column 7 in Table A8 of the Supporting Information). All these checks continued to support our substantive conclusions.

As discussed above, our measures of party issue attention (based on manifesto codings) and national conditions pertaining to different issue areas (based on indicators such as the unemployment rate, GDP growth, CO2 emissions per capita, and so on) may yield imprecise measures of the true or underlying levels of these variables. To explore the possible effects of such measurement error, we re-estimated the coefficients in Figures 1 and 2 in our paper using errors-in-variables analysis, which allows the analyst to specify the correlation between the measured values of the independent variables and the true or underlying variable values. These analyses, reported in Section V in the Supporting Information, support the same substantive conclusions we report above.

We find that our substantive conclusions do not depend on any one country or issue. If we exclude one country at a time from the analyses (results available upon request) or one issue area at a time (Appendix Section VI of the Supporting Information), the substantive conclusions are mostly unchanged.Footnote 15 We also re-estimated the models reported in Figure 1 using an unweighted party system issue attention measure (see Appendix Section II of the Supporting Information), and these estimates continued to support our substantive conclusions. We re-estimated the coefficients of the models in Figure 2 while omitting parties with very small partisan constituencies, for which our survey-based estimates of the constituency's issue attention were less reliable due to sampling error. These estimates, described in endnote 12, continued to support our substantive conclusions.

Finally, we report a Granger-style analysis (Granger, Reference Granger1969) to assess whether the relationship between parties’ issue attention and their supporters’ issue priorities may be reciprocal, that is, that parties’ issue attention influences but is also influenced by its supporters’ issue attention. As discussed in Appendix Section X (of the Supporting Information), these analyses are an approximation since to the best of our knowledge a full-scale Granger analysis cannot be calculated in a panel-structure such as in our data. Subject to this caveat, our estimates support the hypothesis of reciprocal causation, but imply stronger effects of parties’ issue attention on their supporters’ issue attention than vice versa. These tentative analyses thereby continue to support our substantive conclusions.

Conclusion

A vibrant research agenda studies parties’ issue ownership, and their attempts to set the ‘terms of the debate’ in national elections by selectively emphasising the issue areas that enhance their popular appeal. Yet there is surprisingly little cross-national research addressing whether parties’ issue attention actually leads citizens’ issue priorities, and if so, how parties’ issue leadership compares to the agenda-setting effects of national conditions that parties cannot easily manipulate. These are the questions we take up in this paper.

Analysing data on parties’ and citizens’ longer term issue attention along with national conditions across seven issue areas in thirteen western publics between 1971 and 2021, we estimate that the association between party system issue agendas and subsequent mass public's issue attention is only weak and inconsistent. Indeed, the relationships we estimate are so weak that even if the true or underlying relationships are significantly greater than our point estimates suggest, they would still imply that the party system as a whole only modestly leads public issue attention, and that no single party meaningfully leads public attention. These conclusions hold when we account for possible errors in our manifesto-based measures of party issue attention. The one exception to this conclusion may be a very large party – such as the Democratic and Republican parties in the US two-party system – whose size allows it to significantly set the party system issue agenda by itself. By contrast, we estimate substantively significant relationships between individual parties’ issue attention and their supporters’ subsequent attention. Finally, we estimate that national conditions significantly lead public issue attention, with citizens directing increasing attention to issue areas when lagged national conditions in these areas become more problematic. Our study does not include economically poorer Southern European countries in which national conditions might be even more important to voters’ issue priorities. We might therefore underestimate the true effects due to limits in our case selection. Moreover, our analysis spans many issues with distinct national conditions that impact on public attention might plausibly kick in quickly on some issues and slowly on others. We imagine that future research refines our estimations and potentially unveils an even stronger impact of the national conditions.

Although our findings might appear to challenge an implication of issue ownership theory, namely that vote-seeking parties should strategically emphasise the issue areas they ‘own’, we do not draw this conclusion. First, we do find that parties meaningfully lead their partisans’ issue priorities. Parties may view these supporters as a key resource that contributes financial donations along with volunteer work that strengthens the party's organisation and the effectiveness of its election campaigns (e.g., Tavits, Reference Tavits2013). Thus, to the extent that parties lead these core supporters’ issue priorities to align with the party's central issue emphases, this may cement these supporters’ lasting allegiance – thereby conferring long-term organisational and electoral benefits to the party. Second, parties’ issue emphases may enhance their electoral prospects for reasons unrelated to citizens’ issue priorities. For instance, by emphasising particular aspects of a given issue area, parties may frame the issue to their electoral advantage, that is, parties may cue citizens about how to think about an issue area rather than which issue areas to prioritise (e.g., Slothuus & de Vreese, Reference Slothuus and de Vreese2010). Parties may also emphasise issue areas that unite their party, campaigning on issues where the party's elites and activists agree while avoiding topics that prompt damaging intra-party divisions (Egan, Reference Egan2013). Parties can also engage with issue areas that the public widely prioritises, that is, parties can seek electoral support by responding to public issue attention rather than trying to lead this attention (Jennings & John, Reference Jennings and John2009). Finally, policy-seeking parties’ issue emphases may allow them to more credibly claim a public mandate in the event they enter government after the election: the more a party has campaigned on a given issue, the more credibly it can claim a public mandate to enact its policy proposals in this issue area after the election (e.g., Bjarnøe et al., Reference Bjarnøe, Adams and Boydstun2023).

Our study highlights avenues for future research. First, we have noted that the observational relationships we report do not allow us to completely parse out our cause and effect. Future research might analyse whether party leadership of their supporters’ subsequent issue priorities arises because partisans take ‘issue priority cues’ from their in-party; because citizens update their party support to align with their pre-existing issue priorities; or some other process. Second, we might extend this study using alternative shorter term measures of party issue attention beyond manifesto-based codings, such as party press releases (e.g., Sagarzazu & Klüver, Reference Sagarzazu and Klüver2017) and their social media communication (Barbera et al., Reference Barbera, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019). We could similarly develop alternative public issue attention measures. In this regard, it is striking that Barbera et al. (Reference Barbera, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019), who analyse US politicians’ and citizens’ issue attention in the shorter term via content analyses of both groups’ Twitter posts, uncover the same pattern we report here, namely that US legislators display limited abilities to lead the public issue attention. Third, we could investigate the possibility that the relationships we analyse are mediated by factors such as citizens’ levels of political attentiveness and parties’ organisational structures. Fourth, future research should more fully explore different observational relationships across different issue areas, to assess whether parties have greater or lesser abilities to cue citizens (both their supporters and the general public) with respect to some issue areas compared to others. Finally, we have analysed whether not why parties can (or cannot) lead citizens’ issue attention. To the extent that parties cannot meaningfully lead public attention beyond their supporters, how much does this reflect slippage between the parties’ issue messaging and the media's reports of party messaging, citizens’ inattention to party messaging, or citizens’ judgement that the party issue attention cues they receive are not credible? We hope our study motivates follow-up research that addresses these questions. Documenting the relationships between parties’ issue emphases, national conditions and citizens’ issue priorities, as we have done here, is only the beginning of the scholarly process.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as colleagues at the Aarhus Party Politics Speaker Series and the Annual Meeting in 2021 of the Danish Political Science Association for thorough and constructive comments that have much improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest statements

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The replication data (Stata version) and do-file (Stata version) for the analysis are available at the Harvard Dataverse: ‘Seeberg, Henrik Bech; Adams, James, 2024, “Replication files for “Seeberg, HB & Adams, J 2024, “Citizens” Issue Priorities Respond to National Conditions, Less So to Parties’ Issue Emphases”, European Journal of Political Research”, Harvard Dataverse’, via this link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OSCJG0. We would like to take this opportunity to express our gratitude to the enormous work of the national election studies, who have collected high-quality data for each of the multiple elections, that we study, and made it available for further research.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information