The historical and geographical persistence of patterns of political behaviour has been well documented (see, among others, Acharya, Blackwell and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016b; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Homola, Pereira and Tavits Reference Homola, Pereira and Tavits2020; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Rodden Reference Rodden2019; Sanchez-Cuenca Reference Sanchez-Cuenca2019; Tilley Reference Tilley2015; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012; Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006). In many cases, the phenomenon of political persistence is conceptualized as a historical legacy, where the effect of an extinct cause survives vast economic, social and political transformations (Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg Reference Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg2018).

We contribute to this line of research by investigating the long-term effects of agrarian inequality in interwar Europe. According to the classical theory on cleavage formation (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967), the modern system of cleavages was formed in the 1920s and 1930s with the generalization of universal male suffrage and the advent of mass politics. Following Bartolini (Reference Bartolini2000), we argue that in countries in which the economy was still heavily agrarian and there was extreme inequality, landless labourers developed strong preferences for the Left that have survived. Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) argued that the interwar system of cleavages ‘froze’ and determined party competition for many decades to come. We revisit the ‘freezing hypothesis’ from the perspective of historical legacies, arguing that the political effects of agrarian inequality survived industrialization (Tilley [2015] makes a similar argument regarding the religious cleavage).

Spain constitutes an optimal case to study the long-term effects of agrarian inequality. According to Simpson and Carmona (Reference Simpson and Carmona2020), land reform and land-related conflict were the main triggers of the collapse of the Second Republic and the posterior Civil War (1936–39). When democracy was reinstated in 1977, agrarian conflict had been largely defused (Linz and Montero Reference Linz, Montero, Karvonen and Kuhnle2001, 176). Despite Franco's long authoritarian spell, we nonetheless find a strong and robust effect of pre-Civil War agrarian inequality on support for the Left in contemporary Spain (1977–2019). In areas in which there was a greater concentration of landless labour, support for the Left is higher many decades later.

We posit the existence of two, non-exclusive causal channels that account for the persistence of the effects of agrarian inequality. First, land-related conflicts generated enduring political identities and loyalties based on memories of deprivation and repression that were transmitted generationally. Secondly, agrarian inequality had long-term economic consequences (backwardness, poverty and low human capital) that brought about favourable conditions for a strong leftist orientation in society's poorest strata. These channels are different from that envisaged by Rodden (Reference Rodden2019) in his analysis of the persistent geographical patterns of support for the Democratic Party in the US: industrial workers who lived in urban centres and voted for the Democratic Party were replaced in the post-industrial period by poor people who also voted for the Democrats.

We have collected several indicators of historical agrarian inequality at the provincial and municipal levels. No matter what indicator of agrarian inequality we use, we find a systematic effect: the greater the level of inequality, the higher the support for the Left decades later. To avoid concerns about measurement issues, we confirm these results by instrumenting agrarian inequality with the pace of the Reconquest between the eighth and fifteenth centuries. The results do not change.

To estimate the strength of the two mechanisms of transmission (the political and the economic), we use sequential g-estimation to control for potential post-treatment bias (Acharya, Blackwell and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016a). Although action takes place through the economic channel, the political channel seems to be more significant. Regarding the latter, we argue that leftist political identities survived under the dictatorship thanks to family socialization. The analysis of a unique Spanish survey with information about respondents' ideology, their parents' ideology and the side the family took during the Civil War provides suggestive evidence in favour of the family transmission mechanism.

According to the theoretical argument, the historical legacy of agrarian conflict should be observable in countries that were industrial laggards in the interwar period and had high levels of agrarian inequality. A brief exploration of the Italian and English cases confirms this pattern: both countries had extreme agrarian inequality, but Italy was a late industrializer and England an early one. The exploratory evidence we provide shows that Italy is very similar to Spain, with greater support for the Left in regions with more landless peasants, whereas the effect does not exist or is negative in the case of England. This comparative analysis helps to delimit the scope conditions of the main hypothesis.

The article is structured as follows. The first section presents the general hypothesis about the political consequences of agrarian inequality. The second section provides the historical background of the agrarian cleavage in Spain. The third section offers the baseline results and a replication exercise using instrumental variables. The fourth section examines the two causal channels (one political; the other economic) using g-estimation. The fifth section analyses the transmission mechanism of the family. Finally, the sixth section addresses the external validity of our case with a preliminary exploration of the cases of Italy and England.

Agrarian Conflict

Analysing the Western party systems of the 1960s, Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967, 50) identified strong continuity with the politics of the interwar period. As they thought that party systems were a reflection of the cleavage structures in society, they conjectured that the apparent continuity was a consequence of the ‘freezing’ of cleavages after male universal suffrage was introduced in most European countries. The hypothesis was largely confirmed by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990) in their analysis of voting for ideological blocs during the 1885–1985 period.Footnote 1

Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) wrote extensively about the land–industry cleavage. They said little, however, on the agrarian cleavage as such, that is, the social relationships organized around landownership (Urwin [1980] tried to redress this). Compared with industry, property relations in the rural world are complex and varied. Linz (Reference Linz1976) distinguished 13 strata organized in a pyramidal form, with large landowners (latifundium) on top and hired rural labourers at the bottom; in the middle, he identified several situations, from medium and small proprietors to a variety of tenant schemes. We are particularly interested in the most extreme form of conflict: the antagonism between large landowners and landless labourers.

In countries with high levels of agrarian inequality, landowners sought to maintain their privileges and to neutralize the emergence of new industrial elites; consequently, they opposed democracy, which was perceived as a threat to the status quo (Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Boix Reference Boix2003; Moore Reference Moore1967; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2008). Large landholdings are usually associated with various forms of labour coercion and, therefore, with strongly hierarchical social relations. In response, landless labourers resent their dependence on landowners, particularly if their jobs are only seasonal, and frequently support land redistribution. Politically, therefore, they lean towards the Left. Small farmers, by contrast, tend to be conservative, religious and traditionalist; they do not generally favour land redistribution.

In order to be specific about the kind of persistence we analyse, we rely on cleavage theory. Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990, 215) distinguished three elements in a cleavage: (1) the empirical element, defined in socio-structural terms (language, religion, occupation and so on); (2) the normative element, related to the social identities generated by the socio-structural element; and (3) the organizational element, that is, the institutions and organizations (such as parties) that become part of the cleavage. In the case of the agrarian cleavage, the socio-structural element was superseded by industrialization, but the normative and organizational elements survived.Footnote 2 Since the socio-structural element of the agrarian cleavage plays a small role in the contemporary politics of Western countries, we argue that the political dimension of the agrarian cleavage (the normative and organizational elements) can be analysed as a historical legacy of the original socio-structural element regarding landownership.

The agrarian cleavage became particularly salient in the interwar period, when the rural world was politically mobilized for the first time at a mass level. However, its impact varied considerably across Western Europe (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000, 472–5). In countries that industrialized early, agrarian conflict after the First World War was irrelevant or of secondary importance (for example, in Great Britain, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany). A similar diagnosis holds for countries with more egalitarian land distribution (the Nordic ones), regardless of the timing of industrialization. Things were different in countries with extreme agrarian inequality and late industrialization in the 1920s and 1930s, where landless labourers represented between a third and a half of the working class (in Southern European countries and, to a lesser extent, France). It was in these countries that the agrarian issue was key during the interwar period. Rural conflict polarized politics: leftist formations, particularly socialist parties, were less compromising and more tempted by revolution when agrarian workers had a greater presence in their ranks, in contrast to the reformist socialist or labour parties in early industrializing countries, which had a more homogeneous industrial and urban base (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000, 498–9; Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991, 295–302). The agrarian basis of support for leftist parties (socialist, anarchist or communist) in Southern European countries is a well-known phenomenon (Urwin Reference Urwin1980: ch. 4). Moreover, in these countries, the agrarian issue was reinforced by the religious cleavage due to the coalition between large landowners and the Church (Manow Reference Manow2015). Thus, anti-clerical violence was higher in areas of greater agrarian inequality, whereas in more egalitarian regions, small owners sided with the Church.

Our hypothesis, therefore, establishes that in Western European countries that were industrial laggards and had extreme agrarian inequality (with a strong presence of landless labourers), agrarian conflict was more intense and the many landless poor supported leftist parties, while in areas dominated by small landowners, support for the Right was greater. This association survived industrialization because of two complementary mechanisms that were mentioned in the introduction and are fully explored in the fourth section: an economic one in terms of enduring backwardness; and a political one in terms of persistent political identities that were transmitted generationally.

Historical Background: Agrarian Inequality and Land Conflict in Spain

In the European context, Spain was a backward country for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the 1930s, over 50 per cent of Spain's workforce were still employed in agriculture. In addition, Spain had one of the most unequal distributions of landownership in Western Europe, especially in the south-western quarter of the country. It is true that nineteenth-century land reforms had seen vast tracts of land put up for sale, but land sales did not bring about the emergence of a new class of small- to medium-sized landowners (Bernal Reference Bernal1988, 90–5). Thus, a highly unequal distribution of land inherited from the early modern period persisted into the twentieth century. Comprehensive estimates of landownership inequality at the beginning of the twentieth century do not exist, but by the interwar years, Spain had one the lowest shares of family farms in Western Europe, along with countries like Portugal and Italy (Vanhanen Reference Vanhanen2003: Appendix 5).

Poverty and dependence on large landowners were pervasive in the most unequal parts of the country, particularly in the southern provinces of Cádiz, Seville and Córdoba. In these provinces, large estates (above 250 hectares) concentrated more than 40 per cent of total land (Carrión Reference Carrión1975). For a long period from the 1880s onwards, rural labourers in Spain turned towards revolutionary ideologies that promised the confiscation and redistribution of land. Anarchist ideologies spread among the landless peasants in the Andalusian provinces of Córdoba, Seville and Cádiz (Díaz del Moral Reference Díaz del Moral1973; Kaplan Reference Kaplan1977; Maurice Reference Maurice1990).

Given vast inequalities and staggering levels of rural poverty, agrarian conflict became particularly salient during the Second Republic (1931–36) (Domenech Reference Domenech2013; Domenech and Herreros Reference Domenech and Herreros2017). Anarcho-syndicalist and, especially, socialist unions made big gains in the countryside. The membership of the socialist rural union (the National Federation of Agricultural Workers) went from 36,639 members in 1930 to 451,337 in 1933 (while the total membership of the General Workers' Union was over a million) (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991, 297). The number of strikers in agriculture multiplied twentyfold between 1931 and 1933 (Boletín del Ministerio de Trabajo y Previsión Social, Estadística de Huelgas, 1933/34; Population Census, 1930). Following the electoral victory of June 1931, a parliament dominated by socialists and leftist Republicans passed several rural labour market and tenancy reforms.

In September 1932, the Republican–socialist government introduced an ambitious land reform law (Malefakis Reference Malefakis1970, 220–1), which immediately polarized national politics. The interests of small and medium farmers coalesced in 1933 around the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA), a coalition of minor rightist political parties that included reactionary agrarian parties, Catholic groups and monarchists (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017, 348–52). Although not generally threatened by land reform, many small- and medium-sized landowners were negatively affected by accompanying reforms in rural labour and land markets, limiting their ability to hire labourers for harvest or their capacity to lease parts of the lands they owned. As a result, small- and medium-sized landowners ended up supporting the reactionary Right in the 1933 election (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991, 297; Manow Reference Manow2015; Simpson and Carmona Reference Simpson and Carmona2020, 215–19).

The victory of the Popular Front in the general election of February 1936 accelerated land reform. The government intensified the programme of land expropriations and reinstated government-sanctioned temporary expropriations of land. As in 1932 and 1933, a wave of land invasions by local landless peasants swept most municipalities in the south-western region of Extremadura. In July 1936, the Civil War followed a failed coup, dividing the country into two areas controlled by the Republican loyalist and Rebel military forces. In many areas controlled by Republicans, leftist parties, unions and worker militias took control, and land was collectivized (Garrido Reference Garrido1979; Orwell Reference Orwell1962).

The victorious side in the Civil War reversed all previous land expropriations and froze all demands for land redistribution for almost 40 years. Moreover, rapid industrialization in the 1950s and 1960s caused a boom in urban labour demand in the main industrialized areas (the Basque Country, Catalonia and Madrid). As a result, from the mid-1950s, many emigrants left the poorest and most unequal parts of the country. Fast structural change across Spain brought the share of workers in agriculture from 40 per cent in 1960 down to 16 per cent in 1980 (Herrera and Markoff Reference Herrera and Markoff2012, 458).

Thus, even if rural inequality and poverty persisted in a number of regions, agrarian conflict was pretty much deactivated by the economy's structural change. During the transition to democracy, there were echoes of the conflict, as both landless labourers and small farmers demanded better work conditions and greater protection from the state (Herrera and Markoff Reference Herrera and Markoff2012; Quirosa-Cheyrouze and Martos Reference Quirosa-Cheyrouze and Martos2019). However, the size and frequency of agrarian demonstrations were limited in scope compared with those organized in the industrial and service sectors.

Empirical Analysis

To test our main hypothesis, we leverage the heterogeneity of the structure of landownership in Spain, testing whether in those territories with historically greater agrarian inequality, support for the Left in the current democratic period is higher. First, we present our data and variables. To minimize the potential effect of measurement error, we use various indicators of agrarian inequality from different periods and measured at the provincial and the municipality levels. Secondly, we provide baseline estimates for contemporary political preferences as a dependent variable and agrarian inequality from the period 1860–1930 as the main explanatory variable. Thirdly, to address potential issues of measurement error and remote confounders, we instrumentalize land inequality with the pattern of the Spanish Reconquest. Fourthly, we introduce contemporary variables that could explain the inclination towards the Left of certain Spanish territories. In this latter case, post-treatment variables are problematic controls as they could both be affecting the outcome and have been affected by past agrarian inequality. In order to avoid potential post-treatment bias, we follow the sequential g-estimation method developed in Vansteelandt (Reference Vansteelandt2009) and applied to causal inference in political science (Acharya, Blackwell and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016b; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Homola, Pereira and Tavits Reference Homola, Pereira and Tavits2020).

Data and Variables

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is the electoral support for the main Spanish parties of the Left for the period 1977–2019 (fifteen general elections in total). It should be noted that the party system was not stable throughout this period. For instance, the incumbent party in 1977 and 1979 – the Democratic Centre Union – disappeared after 1982. More importantly, the party system suffered a deep shock after the 2011 elections due to the country's economic and political crisis (three new parties with a vote share of over 10 per cent have emerged since 2015). To avoid these fluctuations, we focus on aggregate support for the Left, including: the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), later on known as the United Left (IU); the Spanish Socialist Worker's Party (PSOE); the Socialist Popular Party (PSP) (it only ran in 1977 and merged with the PSOE in 1979); and since 2015, Podemos and Mas País. We leave aside regionalist and nationalist parties that only compete in a few provinces; although they position themselves on the left–right axis, they are also driven by the centre–periphery cleavage, which falls outside the scope of this article.Footnote 3 Nationalist parties are particularly important in two regions: the Basque Country and Catalonia. To control for this, we include a dummy for these two regions. We report vote share as the percentage of the valid vote.Footnote 4

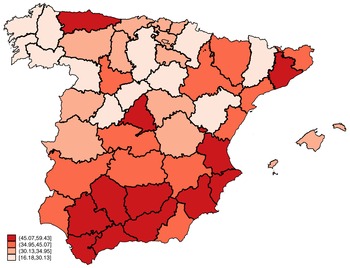

The distribution of party preferences is geographically concentrated. Figure 1 displays the provincial support for the Left in the first democratic elections in 1977.Footnote 5 The South and the Mediterranean Corridor have darker shades than the Centre and the North-West, indicating greater support for leftist parties.

Fig. 1. Electoral support for socialist and communist parties, 1977 general election.

Agrarian inequality

The most obvious measurement of agrarian inequality is the distribution of landownership. However, we lack a complete Land Registry for the early twentieth century to be able to assess this. Moreover, the distribution of farm sizes does not adequately capture agrarian inequality. A lot of land on very large estates could not be immediately used for agricultural purposes without large investments. Therefore, purely area-based indicators of inequality can be misleading.

We focus initially on occupational proxies of agrarian inequality by exploiting information on the presence of landless rural labourers in a province using the Population Census of 1860, as in Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga (Reference Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga2018). Next, we adopt a more granular approach, using municipal-level data and exploiting income-based proxies of agrarian inequality derived from the incomplete Land Registry.

Regarding the 1860 census, we calculate the share of landless farm labourers over the total agricultural population at the provincial level (see Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga Reference Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga2018). The assumption is that in those provinces with a greater share of farm labourers, agrarian inequality was greater. There is a spell of almost 70 years from this measurement to the 1930s, but this is not so problematic once we realize that there were only minor reforms in the period after 1855. Due to this glacial pace of change, the rank order of the provinces in terms of inequality was not significantly altered between 1860 and 1930.Footnote 6

Secondly, we have used direct income-based proxies of agrarian inequality at the municipal level using information from the Land Registry collected in the 1920s by Pascual Carrión (Reference Carrión1975). We use the percentage share of total taxable agricultural income in the municipality corresponding to owners with a taxable income above 5,000 pesetas.Footnote 7 This covers most municipalities in the provinces for which Carrión collected the data (Badajoz, Ciudad Real, Cáceres, Cádiz, Córdoba, Jaén, Málaga, Salamanca and Seville). This exercise gives a municipal-level dataset with income-based estimates of agrarian inequality in 882 municipalities. Our results at the municipal level should eliminate concerns about a problem of over-aggregation in the provincial analysis.

Geographical controls

Both in the provincial and municipal analyses, we add latitude and longitude to control for hidden spatial patterns. We also control for the altitude of the province capital in the provincial analysis and the altitude of the municipality in the municipal analysis.

Contemporary variables

We control for various contemporary province characteristics measured at each election year: the rate of unemployment, level of education and percentages of workers in the agricultural and industrial sectors. Table A1 in the Online Appendix contains descriptive statistics for the variables.

We start by analysing the impact of past agrarian inequality on leftist political preferences. In Table 1, we report the baseline estimates of the effects of agrarian inequality on leftist vote for the 1977–2019 period (fifteen general elections). Column 1 displays the baseline models regressing the percentage leftist vote against 1860 inequality, the geographical controls, the dummy for historical regions and election year dummies. Column 2 presents the municipal-level analysis in the nine aforementioned provinces. Column 3 corresponds to a probit model in which vote intention for the 1977 elections at the individual level is regressed against agrarian inequality in 1860 plus a battery of socio-demographic controls.

Table 1. Effects of historical agrarian inequality on contemporary voting for the Left

Notes: Provincial controls: latitude, longitude, average altitude and dummy for historical region. Municipalities from Córdoba, Jaén, Málaga, Sevilla, Cádiz, Badajoz, Cáceres, Salamanca and Ciudad Real. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

The coefficient in column 1 shows a positive and significant effect of historical land inequality on contemporary voting patterns across the general elections. An increase in ten percentage points in the share of landless peasants produces an increase of four percentage points in the leftist vote. Table B1 in the Online Appendix reports results by election with the measures of both 1860 and 1920: the coefficient is significant in each election, the strongest effect being registered in 1982; the effect becomes weaker, as might be expected, after the breakdown of the party system in the post-2011 elections.Footnote 8

Column 2 uses the municipal dataset with 513 municipalities in nine provinces in the fifteen general elections. We exclude municipalities with fewer than 1,000 voters to avoid the spurious volatility of the vote share in small municipalities.Footnote 9 The main explanatory variable is the proxy for income inequality from the Land Registry (see earlier). As these provinces had generally high levels of agrarian inequality, this is a demanding test of the main hypothesis. Nonetheless, the effect of inequality on voting almost half a century later gives a highly significant point estimate of 0.082, meaning that a one standard deviation increase in inequality increases the leftist vote by two percentage points, which is 15 per cent of the standard deviation in the leftist vote. This regression includes geographical controls, and the effect is robust to the inclusion of province fixed effects.

Since there are potential concerns with ecological analyses, we have also carried out an analysisFootnote 10 with individual data. Column 3 displays the results of a survey conducted in 1977 (survey 1135 by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas). Respondents were asked about their voting preferences before the first elections of the democratic period, when there was still much uncertainty about the levels of support for the various parties. The dependent variable is a dichotomous one, where 1 corresponds to preferences for left-wing parties and 0 for right-wing formations. People who do not report voting preferences or are willing to vote for minor parties are excluded from the analysis. The independent variable is the provincial percentage of landless labourers in 1860. At the individual level, we control for gender, age, education and religion; at the provincial level, we control for latitude, longitude and altitude, as well as for historic regions. We estimate a probit model (clustering standard errors by province). The working sample is close to 9,000 respondents. The coefficient of agrarian inequality is positive and highly significant. Keeping the other variables at their means, the probability of voting for the Left in 1977 with 30 per cent of provincial landless labourers in 1860 is 35.1 per cent; with 70 per cent of landless labourers, it goes to 59.6 per cent. The marginal effect reported in Table 1 is 0.006. Overall, baseline results point to an important and robust effect of agrarian inequality in contemporary patterns of voting.

Instrumenting Agrarian Inequality with Speed of Reconquest

Historical census data can contain significant levels of measurement error, especially in the recording of occupations. For this reason, it might be the case that the coefficients from our baseline regressions are attenuated towards zero. We follow Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila (Reference Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila2016), Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga (Reference Beltrán and Martínez-Galarraga2018) and Tur-Prats (Reference Tur-Prats2019), who have used Spain's Reconquest as an instrument for agrarian inequality and coercive institutions. The Reconquest is the period spanning from the ninth century to the fall of the kingdom of Granada in 1492, in which Christian kingdoms in the north of Spain fought Muslim kingdoms that had been present in the peninsula since the early eighth century. This period had different stages, and the speed and characteristics of this process have been linked to different settlement patterns, institutions and land holdings. The initial period of the Reconquest was characterized by a relatively compact settlement, leading to egalitarian political institutions, free peasants and dispersed landownership. In contrast, after Toledo fell into Christian hands in 1085, the aristocracy and the so-called ‘military orders’ were in charge of guaranteeing the protection of settlers in contested terrain south of the Tagus River. The result was a very dispersed pattern of settlement, with populations of dependent, landless peasants concentrated in large towns. Landownership inequality was greater in these parts of the peninsula, and has remained so until the present day. On the basis of this historical narrative, we use the ‘speed of the Reconquest’ as an instrument for mismeasured agrarian inequality in 1860.Footnote 11

Feudal privilege is linked to other factors, like lower levels of social capital and education, which might also be correlated with contemporary political outcomes (Baten and Hippe Reference Baten and Hippe2018; Baten and Juif Reference Baten and Juif2014), violating the exclusion restriction. We therefore add to our specification the rate of illiteracy in 1860 as an extra control blocking potential impacts of feudal privilege on political preferences other than inequality. By including illiteracy, the levels of human and social capital are taken into account, and the instrument captures agrarian inequality. Table 2 displays the results from the two-stage least squares regressions using ‘speed of Reconquest’ as an instrument for 1860 inequality.

Table 2. Instrumental variable estimates of effect of agrarian inequality on the leftist vote (elections 1977–2019)

Notes: Provincial controls: latitude, longitude and capital altitude. Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Regressions in Table 2 confirm the baseline results.Footnote 12 The two-stage least squares (2SLS) coefficient for agrarian inequality is positive and large.Footnote 13 We have replicated this regression for each election in Table D1, getting in every case positive, large coefficients for the variable ‘speed of Reconquest’.Footnote 14

Channels

According to our argument, agrarian inequality affects contemporary political preferences through two channels. The first causal pathway links agrarian inequality to contemporary political preferences through the political turmoil of the 1930s. We have selected as mediators two highly consequential events that capture the political dynamics of the period. First, we select support for the Popular Front in the 1936 February elections (it included all the centre-left and leftist parties in a joint coalition that won the elections). These were the Second Republic's most polarized elections, in which the electorate split into two opposing ideological sides. The agrarian question played an important role, and this cleavage was reinforced by the state–Church and the centre–periphery divisions. Five months later, the military coup against the Republic failed and brought about the Civil War. Our second mediator is Civil War repression, which deepened the political divisions between the ideological blocs and left painful scars on society. Despite the unfavourable conditions of the long dictatorial spell, we surmise that the political identities forged during the late 1930s persisted for generations to come.

The second channel is economic: agrarian inequality had long-term consequences like delayed industrialization, low human capital, poverty and unemployment (Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila Reference Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila2016); and under these conditions, the distributional issue became more acute and fostered stronger preferences for the Left among the poor.

In order to separate these two channels and to correct for potential post-treatment bias, we employ techniques from the literature on mediation analysis. In the model, historical agrarian inequality has both an effect on the mediators (voting in the 1936 elections and Civil War violence) and on the intermediate confounders (the contemporary economic conditions of the provinces). The existence of intermediate confounders and post-treatment bias suggests that a causal mediation model should be adopted. In this sense, we follow Acharya, Blackwell and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016a) and use sequential g-estimation to isolate the two potential causal relationships.

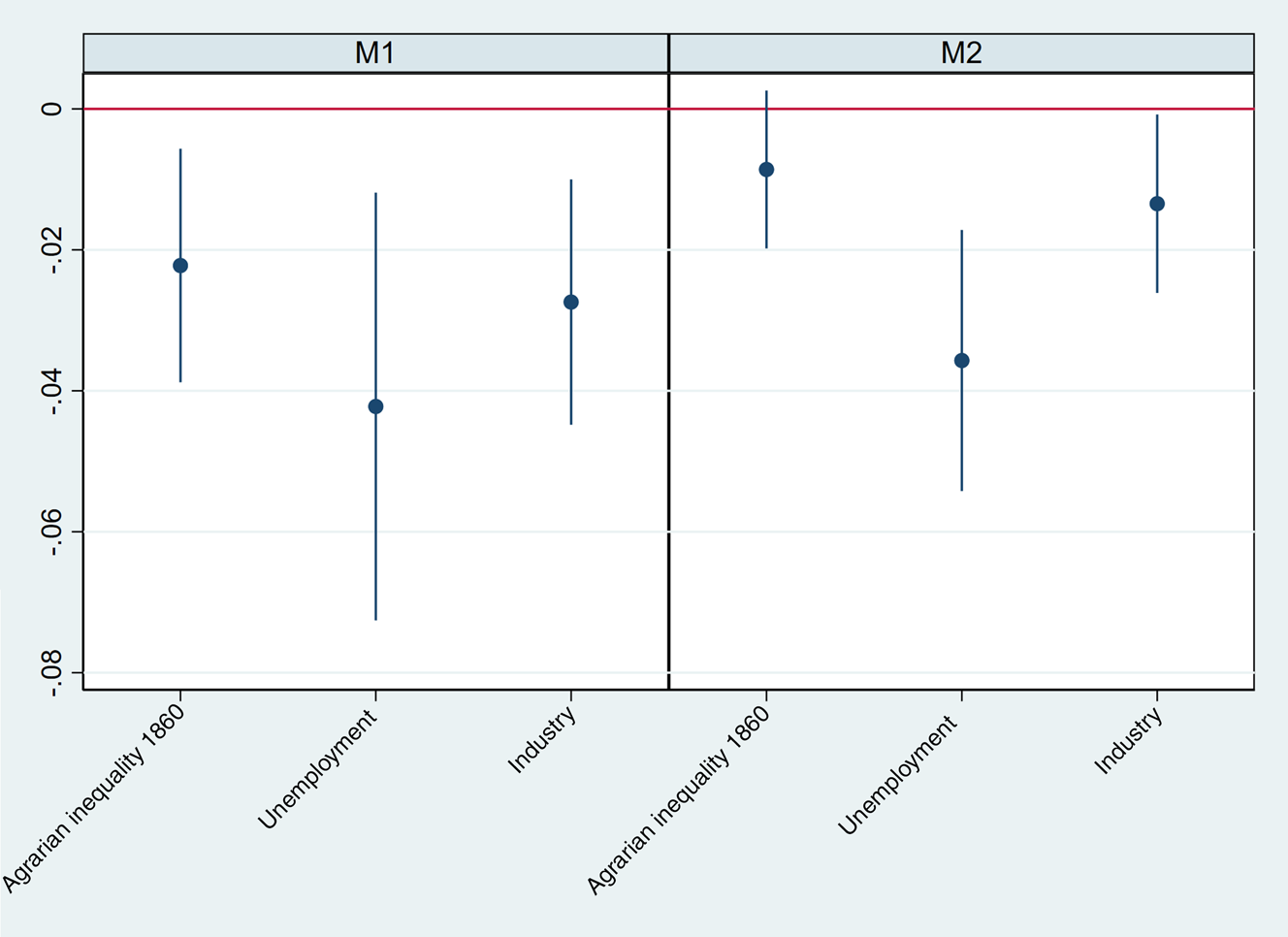

Our first step is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) displaying the main causal relationships in our simple model (see Figure 2). The graph specifies the pre-treatment variables (geographical factors and old regime characteristics), the treatment (historical agrarian inequality), the mediator variables in the political channel (the 1936 elections and Civil War repression) and the post-treatment variables that are contemporaneous to the outcome variable (levels of industrialization, education and unemployment at the time of the elections during 1977–2019).

Fig. 2. DAG explaining political attitudes in the democratic period in Spain.

To proceed with the sequential g-estimation, we first expand our baseline regressions to include the mediator variables and the intermediate confounders alternatively. One first snapshot of the relative importance of these channels can be simply grasped by gauging the change in the main coefficient on agrarian inequality when adding the mediators or the intermediate confounders to the baseline specification (Baron and Kenny Reference Baron and Kenny1986). For the mediators, we use the provincial percentage of the vote going to the Popular Front in the general election of February 1936 (the source is Alvarez Tardío and Villa [Reference Alvarez Tardío and Villa2017]). Regarding Civil War repression, we use the data from Espinosa (Reference Espinosa2010).Footnote 15 For the analysis, we include only the number of civilians killed by the Rebels since the repression of the Republicans is associated with support for the Popular Front in the 1936 elections (it makes little sense to assume that Republican repression strengthens leftist allegiances). We ‘normalize’ the number of murdered civilians using the inverse hyperbolic sine function.Footnote 16

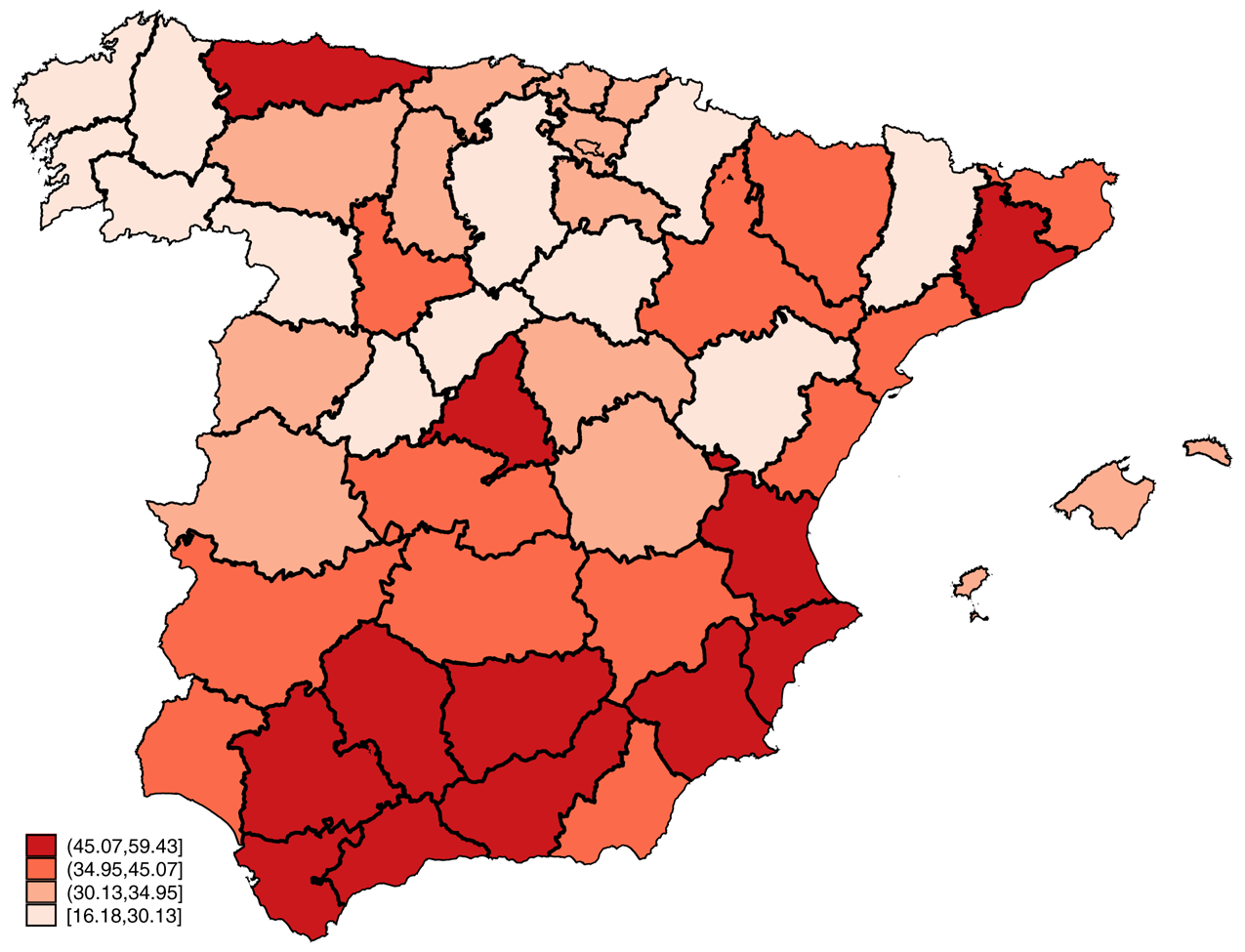

We start by analysing the main channels using the provincial-level data in Table 3. Column 1 uses the same variables as in Table 1 but now adds the percentage vote going to the Popular Front in 1936, as well as rightist Civil War repression. The two variables have positive and large coefficients. Adding the mediators sharply reduces the baseline coefficient of 1860 agrarian inequality from 0.406 to 0.107. In column 3, we focus on the intermediate confounders. Contemporary unemployment gets a large, significant coefficient while the other confounders are non-significant. The coefficient on 1860 inequality (0.294) is three times as big as that of column 1, showing a smaller reduction through this channel. Although these estimations are affected by post-treatment bias, they suggest that the political mechanism is a more dominant channel than the intermediate economic confounders.

Table 3. Provincial mediator analysis: Popular Front channel augmented with Civil War violence

Notes: Provincial controls: latitude, longitude and average altitude. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

Moving to the sequential g-estimate, we have applied the Stata code from Acharya, Blackwell and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016a) to estimate the controlled direct effects of the treatment variable. This procedure de-means the main variable to keep the intermediate confounders or the mediator constant, re-estimates the regression without post-treatment variables and bootstraps the standard errors of the coefficient of interest. In column 4, we present the results of the sequential g-estimation when the intermediate confounders (unemployment, education and industrialization) are fixed. The coefficient on agrarian inequality in 1860 captures the effect that goes through the political channel, in this case, the front-door pathway via our selected mediators. We obtain a very similar coefficient of land inequality to that of column 3. A one standard deviation increase in 1860 inequality (10.24 percentage points) is associated with a 2.94 percentage point increase in the leftist vote, which represents almost a third of the standard deviation in the leftist vote.Footnote 17 Column 2 looks at the other potential channel, this time de-meaning the level of the mediators (Popular Front and rightist repression in the Civil War) with the same procedure. The coefficient hardly changes with regard to that in column 1, confirming that both channels matterFootnote 18 but the political channel far more so.Footnote 19

We now replicate these results using municipal data. In this case, it was impossible to replicate the analysis for the municipalities from the nine provinces in Table 1, as there is no comprehensive municipal-level data set of electoral results in 1930s’ Spain. We analyse the 112 municipalities of Badajoz and Cáceres (both forming the Extremadura region), with more than 1,000 voters. Electoral data have been compiled by Espinosa (Reference Espinosa2007) and Ayala (Reference Ayala2001). We provide the same analysis for the whole set of 222 municipalities in Extremadura, with complete information in Table G1 in the Online Appendix. Since the intermediate confounders used in the provincial analysis are not available for municipalities, we use two alternative variables. We proxy the level of education using the illiteracy rate of 1930 (assuming that the ranking order between municipalities does not change significantly), we control for development by adding population change in the municipality between 1930 and 1970 (assuming that faster population growth is associated with development), and we use the total number of voters in each municipality in each election as a proxy for contemporary population.

Municipal results appear in Table 4. Column 1 includes the mediators (Popular Front vote and rightist Civil War repression). When the mediators are included, the coefficient of the treatment variable falls to 0.059 (from the 0.081 baseline).Footnote 20 Column 3 presents the regression excluding the mediator but including the intermediate confounders. The effect of agrarian inequality is now 0.079, which is much closer to the baseline coefficient. The results of the g-estimation in columns 2 and 4 confirm these results.Footnote 21 Although there is a risk of omitted variable bias, these preliminary results suggest that the effect of historical agrarian inequality on contemporary voting patterns flows with greater intensity through political preferences in the 1930s.

Table 4. Municipal mediator analysis, popular front channel augmented with Civil War violence

Notes: Controls: altitude, latitude and longitude. Provinces: Badajoz (1) and Cáceres (2). * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

In Tables I1 and I2 in the Online Appendix, we replicate the previous analyses adding the pre-treatment confounders specified in Figure 2. We use the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE 1986) to add pre-treatment variables: the share of landless peasants in the population in 1787 as a proxy for agrarian inequality; and dummies capturing the type of feudal jurisdiction of the municipality (municipality under the king's jurisdiction or under the jurisdiction of the nobility, the Church and the so-called military orders, with the reference category being the municipalities under the king's jurisdiction, in Spanish, realengo municipalities). As it is difficult to construct aggregate measures of pre-treatment confounders at the provincial level, we add the ‘speed of Reconquest’ as an extra regressor. The coefficients on our proxy for agrarian inequality in columns 2 and 4 of Tables I1 and I2 in the Online Appendix reinforce the results in Tables 3 and 4: the ‘political’ mediators have a stronger effect than the ‘economic’ intermediate confounders.

Political Allegiances

We interpret the results on the political channel as evidence that the agrarian conflict culminating in the interwar period forged resilient political identities that survived Franco's long dictatorship (1939–77). This interpretation is consistent with Maravall (Reference Maravall1982), who highlighted the remarkably close spatial correlation between the last elections of the Second Republic in 1936 and the first democratic elections after Franco's death in 1977.

The question that remains to be answered is how ideological allegiances have survived for such a long period of time under such unfavourable historical circumstances. The literature on historical legacies has contemplated several transmission mechanisms: the Church (Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006), the school (Darden and Grzymala-Busse Reference Darden and Grzymala-Busse2006) and the family (Acharya, Blackwell and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016b; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012).

Taking into account the peculiar history of Spain during the twentieth century, we surmise that the main transmission channel of political identities, particularly for those on the Left, was the family. This seems an inescapable conclusion given the extraordinary length of Franco's regime. Over almost four decades, parties and unions were banned. The Church, moreover, was closely aligned with the dictatorship.Footnote 22 Education was under the control of the state and the Church. The Church and the school may have contributed to the reinforcement of rightist identities, but not to leftist ones. Ruling out the Church, school, parties and unions, we are left to conclude that the most likely agent of generational transmission was the family (for a similar argument, see Tilley Reference Tilley2015). The importance of the family for transmission of political values is a well-documented finding in the literature on political behaviour (see, among many others, Jennings Reference Jennings1984; Jennings, Stoker and Bowers Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Ventura Reference Ventura2001).

In the absence of panel data, we cannot prove family transmission. However, we leverage aFootnote 23 unique survey that provides evidence for it (survey 2760 [April 2008] of the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas). It contains information about the respondents' ideology and the ideology that they attribute to their parents, as well as the side their ancestors took during the Civil War. If the transmission of ideology goes through the family, we should observe that respondents living in provinces with higher pre-1936 agrarian inequality attribute more leftist positions to their parents. If this is confirmed, the case for family transmission is substantially reinforced.

The ideological scale goes from 1 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right). The correlation between the respondent's ideology and the ideological position attributed to their mother and father is 0.60 and 0.56, respectively. Moreover, the association between the parents' ideology and the side that the family took during the Civil War is very strong. For instance, when the family supported the military Rebels, the ideology attributed to the father is 6.94, compared with only 4.37 in other cases (a Republican family or a divided one). The difference is strongly significant and tends to confirm the cross-generational transmission of ideological values. More systematic means comparisons are presented in Table M1 in the Online Appendix.

Going beyond bivariate relationships, we conduct an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with province-clustered standard errors in which the dependent variable is the ideology attributed to the parents (the average of the mother's and father's positions). We also control for other individual traits that might have an effect on the respondent's ideology: gender, age, education and religiosity. As for provincial variables, we introduce the percentage of landless labourers in 1860, as well as the unemployment rate and the percentage of workers in the industrial sector in 2008. Full results are reported in the in Table N1 in the Online Appendix. Here, we only focus on the provincial coefficients.

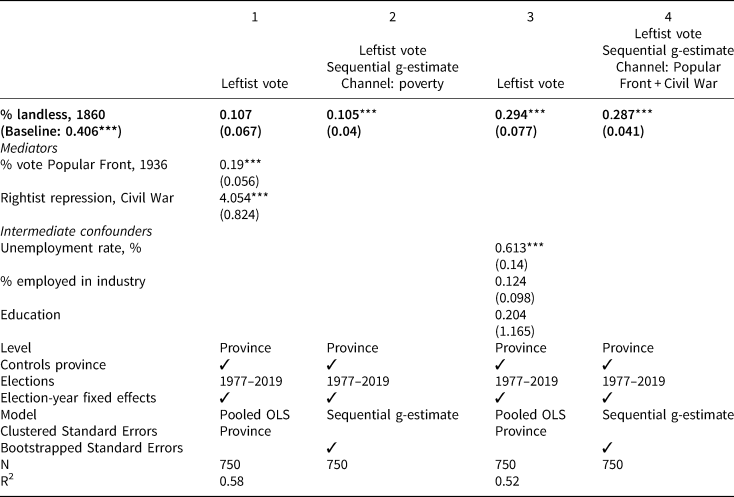

Figure 3 displays two coefficient plots. In the left panel, the coefficient on agrarian inequality is negative and significant at a 90 per cent confidence level (the higher the level of agrarian inequality, the more leftist the ideology attributed to the parents). An increase of ten points in the percentage of landless labourers in 1860 implies a shift of 0.22 points towards the left in the ideology attributed to the parents. Contemporary levels of unemployment and industrialization are negative and significant. The higher the level of unemployment, the more leftist the parents' ideology. Also, in more industrialized provinces, the parents are more leftist.

Fig. 3. Coefficient plot: M1 without family's sympathies during the Civil War; M2 with family's sympathy during the Civil War.

In the right panel, two dummies for the sympathy of the family during the Civil War with the two sides (the Republic and the military rebels) have been added. The reference category is those who do not answer or say that their family had no sympathy for either side, or that the family was divided. In line with the results about the causal channel of the previous section, we expect that once we control for the family's political allegiances in the 1930s, the effect of agrarian inequality is weakened. This is precisely what we observe: whereas the coefficients of unemployment and industry are still significant (although less so), the coefficient of agrarian inequality is cut by more than half and loses significance.

The analysis of the survey supports our main argument and adds plausibility to the family transmission mechanism. In provinces with higher historical agrarian inequality, respondents place their parents on more leftist ideological positions. The effect, however, is neutralized when we control for the family's political sympathy during the Civil War, which is consistent with the political channel.

Comparative Discussion

We now discuss if agrarian legacies can be found in other European democracies. Following Bartolini (Reference Bartolini2000), the scope conditions of our hypothesis on the electoral effects of the agrarian conflict are twofold: late industrialization and high agrarian inequality when mass politics arrived in the interwar years. Spain meets these conditions and the hypothesis is confirmed. In this section, we provide exploratory evidence of two other cases: Italy and England.Footnote 24 Both had agrarian inequality, but Italy is a late industrializer and England an early one. Therefore, we expect to find in Italy the same pattern as in Spain: greater support for the Left in regions with historically large rural inequality. In England, however, we should not find a positive association, as the agrarian question was already in the past when mass politics emerged in the interwar period.

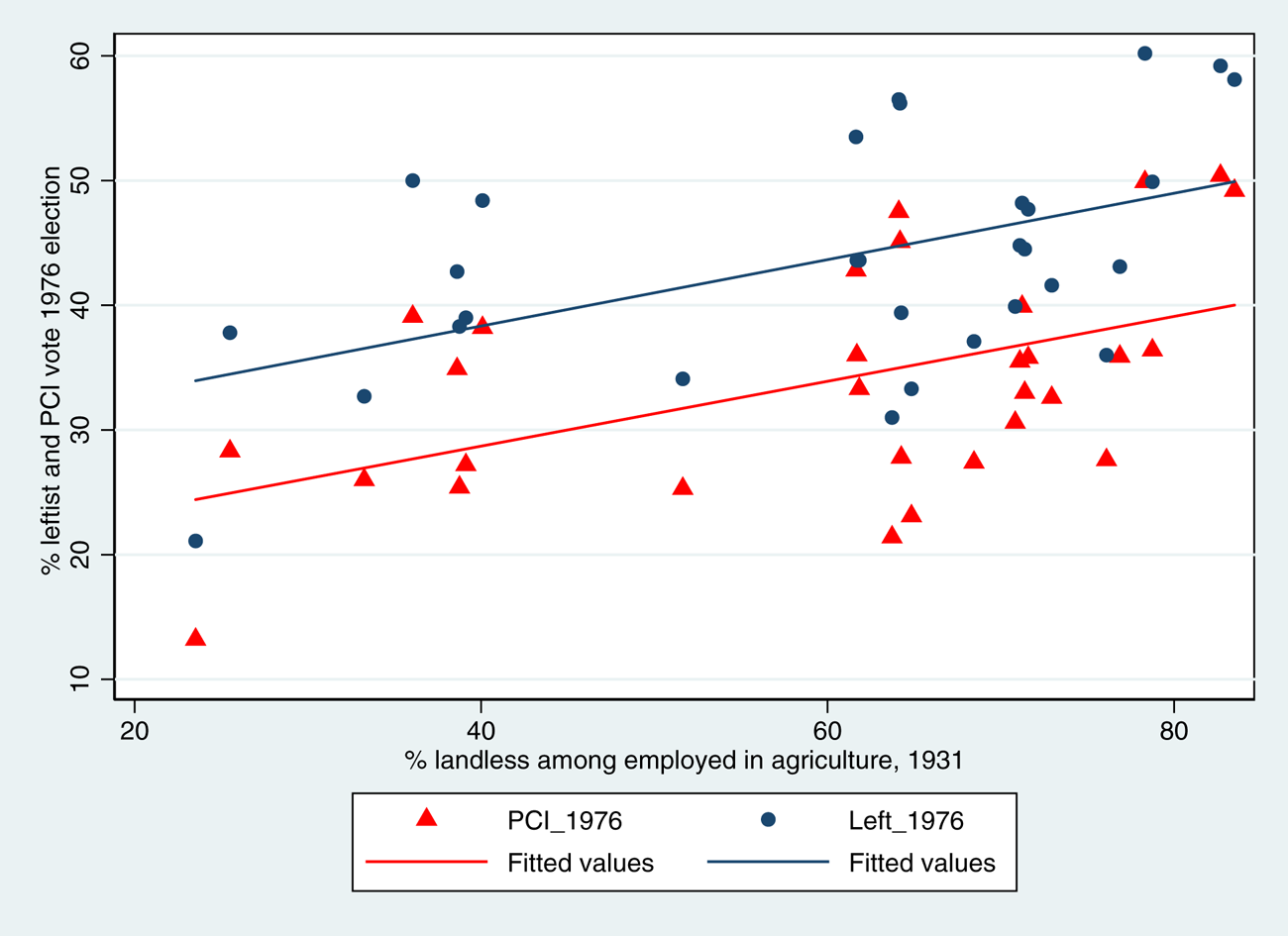

In the case of Italy, we combine voting patterns in the 1976 elections with evidence on agrarian inequality from the 1930s. By 1930, 52 per cent of Italy's gainfully employed were employed in agriculture (Broadberry, Giordano and Zollino Reference Broadberry, Giordano and Zollino2011). We use the Population Census of 1931 to calculate the proportion of landless peasants in the population. The unit of analysis is the electoral district. In Figure 4, the vertical axis separately represents the proportion of votes cast in favour of the Italian Communist Party and of all leftist parties together (including the Communist Party) in the 1976 general elections. These were the elections in which support for the Communist Party peaked in the Italian First Republic. Given very fast structural change in the 1950s and 1960s, agrarian issues were not a central concern of voters in the 1970s. However, in the case of the elections studied here, a pretty tight and a positive gradient linking agrarian inequality and preferences for leftist political parties is visible in the data. A purely exploratory analysis generates positive, significant coefficients and high goodness of fit. We use the Italian case for illustrative purposes, and do not elaborate on the complex political story behind it. Figure 4 is consistent with the main hypothesis of the article. In the Online Appendix (see Figure O1), we discuss the case of Portugal, which also shows a positive correlation between historical agrarian inequality and contemporary support for leftist parties.

Fig. 4. Relationship between agrarian inequality and leftist vote in Italy.

Note: PCI = Italian Communist Party.

The Italian case contrasts sharply with the geographical distribution of leftist preferences in England. In this case, we combine electoral support for the Labour Party in the five elections held in the 1970s from the House of Commons Library's ‘UK election statistics: 1918–2019’ with various indicators of rural poverty, conflict and inequality in the 1820s, 1830s and 1870s.Footnote 25

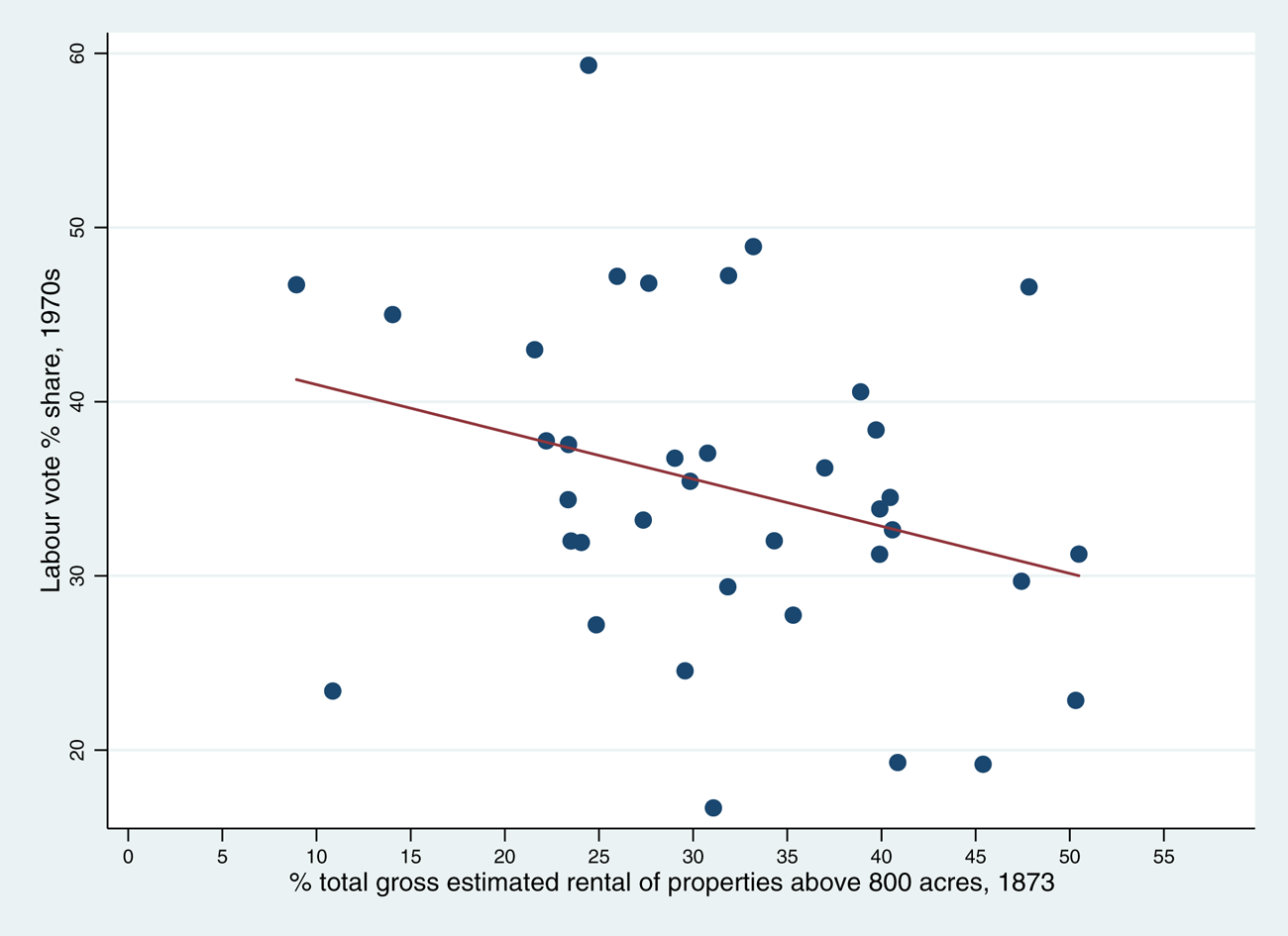

The 1820s and 1830s represent a period of rural poverty and intense rural conflict in parts of England, including significant poor relief expenditure and the Swing Riots. We use three indicators: poor relief expenditure; the Swing Riots; and an 1870 indicator of agrarian inequality. Regarding poor relief per head in the 1820s and 1830s at the county level, we rely on Blaug (Reference Blaug1963). The most authoritative quantitative study on the English Poor Law argues that poor relief expenditures in the period 1760 to 1815 were negatively correlated with access to land and positively correlated with winter unemployment rates (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 38, 132). Secondly, we focus on the Swing Riots, as they mark the peak of rural conflict in nineteenth-century England. We have collapsed at the county level the parish-level data on riot events from Caprettini and Voth (Reference Caprettini and Voth2020). Rural discontent was correlated with the use of mechanical threshers, which severely depressed the winter employment prospects of rural labourers, suggesting that the Swing Riots were closely correlated with rural poverty and landlessness (Hobsbawm and Rudé Reference Hobsbawm and Rudé1968, 359).Footnote 26 The connection between rural poverty and rural conflict shows up in the positive correlation between the average number of Swing Riots at the county level and poor relief expenditure in 1831 (correlation is 0.41). Finally, we have used the 1873 Report of Owners of Land to construct county-level measures of agrarian inequality by calculating county-level measures of the share of total rents concentrated in the hands of owners of more than 800 acres (Great Britain Local Government Board Reference Great Britain Local Government Board1875). By 1873, Britain (in this case, England) was already very urbanized, but the 1873 report is the only source that allows us to construct comparable measures of agrarian inequality with those we have for Spain in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The correlation between poor relief per head paid in 1831 and our 1873 measure of inequality is 0.3.

In contrast to the Spanish or the Italian cases, past agrarian conflict and inequality in England is not associated with stronger support for the Left in the contemporary period. On the contrary, rural poverty and rural conflict are negatively correlated with leftist vote. In Figure 5, we plot the relationship between landownership inequality in 1873 and the average share of votes for Labour in the 1970s. The negative relationship is apparent in the figure, the correlation between the share of the Labour vote and the share of total rents going to owners of more than 800 acres in 1873 is −0.3. Similarly, the correlation of leftist vote with poor relief per capita in 1831 is −0.37, while the correlation with the mean number of Swing Riots is −0.17. Therefore, there is either a negative or zero correlation between indicators of rural inequality, poverty or conflict and the Labour vote in the 1970s. Figures P1, P2 and P3 in the Online Appendix present scatter plots displaying the relationship between the various measures of rural poverty and conflict in the 1830s and the share of the Labour vote. The main conclusion of this analysis is that although England had a turbulent past of agrarian poverty, inequality and conflict, especially in the early 1830s, agrarian legacies do not explain the geography of Labour Party support there. When male suffrage became universal after the First World War, rural conflict was not a salient issue, and, consequently, we see no trace of greater support for the Left in areas of higher agrarian inequality.

Fig. 5. Relationship between agrarian inequality and leftist vote in England.

Conclusions

Although industrialization downplayed the relevance of the socio-structural element of the agrarian cleavage, the political allegiances that were part of the cleavage have survived until the contemporary period in some countries. To analyse this phenomenon, we have bridged the classical literature on cleavages and the burgeoning literature on historical legacies.

Given its troubled history during the twentieth century, including several regime breakdowns, a traumatic Civil War and a long dictatorial spell, Spain is one of the least auspicious countries in Western Europe for finding persistent political effects caused by old cleavages. Nonetheless, we have found a robust positive effect of pre-Civil War agrarian inequality on support for the Left in the contemporary democratic period (1977–2019).

The effect found in Spain is part of a larger pattern. Our argument establishes that similar effects should be found in other European countries that were late industrializers and had high agrarian inequality. By contrast, in early industrializers or in countries with a more egalitarian distribution of land, the effect should not exist. An exploratory analysis of Italy and England confirms these expectations: in Italy, we find a very similar effect to that of Spain, but not in England, the earliest industrializer in Europe. This opens the way for a more systematic and comparative investigation of the long-term consequences of the cleavage systems of the interwar period.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000387

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this paper can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PZ9OMY

Acknowledgements

We thank Francisco Espinosa for sharing his data on Civil War violence and Daniel Oto-PeralÃas for sharing his data on the speed of the Reconquest. Paloma Aguilar and participants in the Carlos III-Juan March Institute of Social Sciences seminar provided invaluable feedback.

Financial Support

This research was supported by Spain's State Agency for Research (Agencia Estatal de Investigación [AEI]) (AEI grant PID2019-104869GB-100).

Competing Interests

None.