Introduction

In a seminal contribution to this journal – from which the main title is borrowed here – Maurice Duverger (Reference Duverger1980) defined the concept of ‘semi‐presidential government’ and analysed the diversity of practices in what was then only a small set of semi‐presidential countries (see also Elgie Reference Elgie2011, Reference Elgie2016). This article carries out a similar analysis for the concept of ‘semi‐parliamentary government’. The proposal of this article is to understand the latter as the mirror image of the former. A semi‐presidential system divides the executive into two equally legitimate parts, only one of which – the prime minister – depends on assembly confidence for its survival in office. Conversely, a semi‐parliamentary system divides the assembly into two equally legitimate parts, only one of which possesses the power to dismiss the prime minister in a no‐confidence vote.Footnote 1 Such a system establishes a formal separation of power between the executive and one part of the assembly. Semi‐parliamentary government is a distinct, but neglected executive‐legislative system and a ‘missing link’ in our typological thinking about democratic constitutions.

In this article, the constitutions of the Australian Commonwealth, the bicameral Australian states and Japan are identified as semi‐parliamentary. Analysis of these cases will be connected with the comparative literature on executive‐legislative systems and the Australian experience will be drawn upon to discuss new semi‐parliamentary designs. These designs do not necessarily require formal bicameralism. For example, a simple way to implement semi‐parliamentarism is a legal threshold of confidence authority: parties with a below‐threshold vote share would be denied the right to participate in a no‐confidence vote, but they would be allowed fair representation in the legislative and deliberative process in parliament. Semi‐parliamentarism might also be an attractive option for democratising the European Union (EU).

Semi‐parliamentary government deserves the attention of constitutional and democratic theorists because it may avoid important downsides of pure presidential and parliamentary systems, while maintaining many of their core strengths. In presidential systems, neither citizens nor representatives can remove an incompetent (rather than criminal or incapacitated) president from office – at least unless they are willing to stretch the constitutional rules (e.g., Marsteintredet et al. Reference Marsteintredet, Llanos and Nolte2013).Footnote 2 The concentration of executive power in a single individual also provides strong democratic reasons for constitutional limits on re‐election, but these limits undermine the executive's electoral accountability and are often difficult to enforce (Ginsburg et al. Reference Ginsburg, Melton and Elkins2013; Linz Reference Linz, Linz and Valenzuela1994: 12). Popularly elected chief executives weaken parties’ unity and programmatic capacities (Carey Reference Carey2007; Samuels & Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010); and while they may not increase the overall risk of democratic breakdown (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007), they do seem to pose a persistent threat of authoritarian takeover by the incumbent president (Maeda Reference Maeda2010; Svolik Reference Svolik2015).

Semi‐parliamentarism may offer potential solutions to these problems. It allows citizens to choose a prime minister in a way that mimics presidential elections, but the incumbent can be re‐elected without limits and removed at any time by his or her party, or by the majority in one part of the assembly. Adequately designed, this part can function as a standing two‐party ‘confidence college’ for the prime minister. Since the executive's survival is constitutionally independent from the other part of the assembly, there is still a form of branch‐based separation of powers. Semi‐parliamentarism can achieve power separation without presidents.

A core problem of pure parliamentarism is the unavoidable tension it creates between parliament's representative, deliberative and legislative roles, on the one hand, and its function as a ‘confidence college’ for the cabinet, on the other. The former roles may suggest highly proportional electoral systems, yet the resulting fragmentation of parliament raises worries about the identifiability, accountability and stability of cabinets. Political science has discussed this tension as one between the proportional and majoritarian ‘visions of democracy’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012; Powell Reference Powell2000). Due to its separation of powers, semi‐parliamentary government has the potential to balance these visions: the part of the assembly with confidence authority can achieve the ‘majoritarian’ values of identifiability, accountability and cabinet stability, whereas the separated part can allow for proportionality, a multidimensional party system and issue‐specific deliberation on individual pieces of legislation (cf. Ward & Weale Reference Ward and Weale2010).

The discussion proceeds as follows. I begin by locating semi‐parliamentarism in a general typology of executive‐legislative relations and providing a minimal definition of it. Then, I construct an ‘ideal‐type’ of semi‐parliamentary democracy and analyse how far the (minimally) semi‐parliamentary systems in Australia and Japan approximate it. After elaborating on the theoretical argument, I go on to summarise the electoral designs in the bicameral Australian polities and empirically compare the balancing of the majoritarian and proportional visions of democracy in New South Wales and the Australian Commonwealth to the balancing achieved in 20 parliamentary and semi‐presidential systems. Finally I discuss new semi‐parliamentary designs before drawing my conclusions.

Typology and minimal definition

The dominant practice in political science has been to neglect upper houses in classifying a democracy's executive‐legislative system. In my view, this practice cannot be justified if the upper house is directly elected and thus prima facie equally legitimate as the lower house.Footnote 3 If two houses of parliament have an equal claim to represent the people, but only one of them can dismiss the prime minister, then a hybrid system is established. Once we understand the structure of this hybrid, we can also see that it does not require formal bicameralism. In developing the following typology, therefore, I will sometimes speak of the two ‘parts’ of an assembly rather than its two ‘houses’.

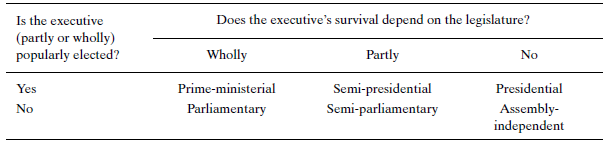

Table 1 distinguishes six types of executive‐legislative systems based on how the executive comes into and survives in office (Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). The types form three logical pairs. The first consists of the two pure types. A popularly elected fixed‐term president, whose survival in office does not depend on the assembly, defines a presidential system. If two directly elected houses exist, the president must not depend on the confidence of either of them. In a parliamentary system the executive emerges from the assembly and its survival depends on the assembly's ongoing confidence. If two equal houses exist, it is dependent on both of them (as it continues to be in Italy after the failed constitutional referendum of December 2016).

Table 1. A typology of executive‐legislative systems

Source: Adapted from Ganghof (Reference Ganghof2014).

The second pair consists of two hybrids that combine one parliamentary with one presidential feature. ‘Assembly‐independent government’ (Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992: 26) describes a system in which the executive is voted into office by the assembly but, once in office, cannot be dismissed in a no‐confidence vote. If there are two equally legitimate houses of parliament, as is the case in Switzerland, the survival of the cabinet must not depend on either of them. A popularly elected prime minister, who can be dismissed in a no‐confidence vote of the assembly, defines prime‐ministerial government. If the assembly consists of two equally legitimate houses, both must have this dismissal right. Israel established a unicameral version of this system in the mid‐1990s and abandoned it again a few years later (Ottolenghi Reference Ottolenghi2001).

The third pair also mixes elements of parliamentary and presidential government, but it does so by dividing either the executive or the assembly into two parts with equal democratic legitimacy. In semi‐presidentialism a fixed‐term president is legitimised through popular (direct) elections, but there is also a prime minister dependent on parliamentary confidence (Elgie Reference Elgie2011). If there are two equally legitimate houses, both must be able to dismiss the prime minister, as is the case in Romania. Finally, in semi‐parliamentarism both parts of the assembly (most commonly: both houses) are legitimised though direct election, but the prime minister and his or her cabinet are dependent on the confidence of only one of them.Footnote 4 Both hybrids establish a partial dependence of the executive on the assembly's confidence: either only a part of the executive is dependent on confidence (semi‐presidentialism), or only a part of the assembly needs to provide this confidence (semi‐parliamentarism).

By proposing the typology in Table 1, I do not want to suggest that the detailed institutional choices within the six basic types do not matter, that these choices follow directly from the basic type, or that the types as such are generally very useful in explaining political outcomes (see Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2014; Elgie Reference Elgie2016; Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). Yet I do contend that, based on the two well‐established analytical dimensions for classifying executive‐legislative systems, semi‐parliamentary government constitutes a distinct and neglected type. To specify it further, I first give a ‘minimal’ definition with which cases of semi‐parliamentarism can be clearly identified and distinguished from other types (cf. Strøm Reference Strøm2000). The definition builds directly on Table 1:

(1) There are no popular elections of the chief executive or head of state.

(2) The assembly has two parts both of which are directly elected.

(3) The executive's survival depends on the confidence of one part of the assembly, but not the other.

Note that this definition does not include any requirements about the legislative power of the upper house, especially its veto power. This is in line with the most recent literature on executive‐legislative systems. While earlier work on presidentialism and semi‐presidentialism views the formal powers of the president as a defining attribute (Duverger Reference Duverger1980; Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992), more recent work does not (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2014; Elgie Reference Elgie2011). Yet legislative power is certainly important. I argue below that an ideal‐type of semi‐parliamentary democracy requires that at least the separated part of the assembly (the upper house in the bicameral case) have absolute veto power over all (non‐budgetary) legislation. The minimal definition also does not rule out the possibility that the cabinet is partly drawn from the part of the assembly without confidence authority (the upper house). Upper house ministers are common in Australia. Finally, while the suggested minimal definition of pure semi‐parliamentarism rules out popular executive elections, there can also be a ‘semi‐parliamentary’ version of semi‐presidentialism. This more complex hybrid exists in the Czech Republic, which has a directly elected, fixed‐term president, a prime minister dependent on lower house confidence and a directly elected upper house without the power to dismiss the cabinet. However, the Czech constitution gives neither the president nor the upper house strong formal powers. The lower house can overrule their legislative vetoes with absolute majorities.

Based on the minimal definition, we can identify seven (pure) semi‐parliamentary democracies: the Australian Commonwealth, five Australian states and Japan.

A semi‐parliamentary ideal‐type and its approximations

This section develops a richer definition of semi‐parliamentary ‘democracy’. It is a more ‘ideal‐typical’ definition (cf. Strøm Reference Strøm2000), although not in the strict sense that no real‐world system could satisfy its conditions. One purpose is to clarify the logic of democratic delegation embodied in this constitutional regime. Another is to provide criteria for judging how closely the (minimally) semi‐parliamentary cases approximate the ideal‐type.

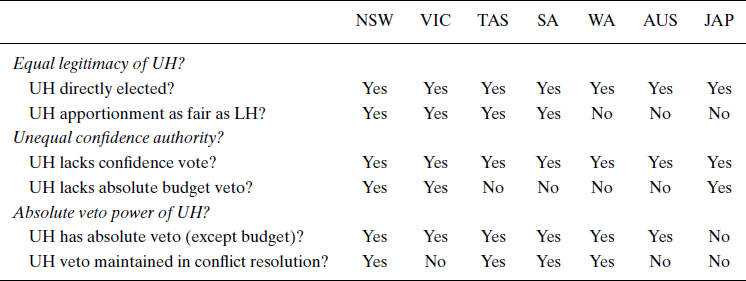

In the language of agency theory, the logic of democratic delegation in a semi‐parliamentary regime is that voters, as the ultimate principal, select two separate but equally legitimate legislative agents, only one of which then becomes the principal of the prime minister and his or her cabinet. The cabinet is hierarchically subordinate to one part of the assembly, but not the other. This logic of delegation implies three desiderata. First, the democratic legitimacy of the two parts of the assembly ought to be equal. Second, the survival of the cabinet ought to be fully independent from one part of this assembly. Third, the legislative veto power of this separated part of the assembly ought to be absolute. These desiderata have six specific institutional implications, which I discuss in turn (see Table 2).

Table 2. Approximations of semi‐parliamentary ideal‐type

Notes: UH = Upper house, LH = Lower house, NSW = New South Wales, VIC = Victoria, TAS = Tasmania, SA = South Australia, WA = Western Australia, AUS = Australian Commonwealth, JAP = Japan.

Sources: Stone (Reference Stone, Aroney, Prasser and Nethercote2008) as well as the respective constitutions and electoral statistics.

The first element to be considered is democratic legitimacy. By the minimal definition given above, all seven systems in Table 2 have directly elected upper houses. However, the relative (normative) legitimacy of the upper house is reduced if it is more malapportioned than the lower house – that is, if the apportionment of districts violates political equality to a greater extent.Footnote 5 It is well‐established that malapportionment also limits the perception of upper houses as legitimate (Russell Reference Russell2013: 384). The former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating famously referred to senators as ‘unrepresentative swill’. Most upper houses considered here have greatly reduced malapportionment. It is completely absent in the upper houses of New South Wales and South Australia due to their single state‐wide districts. However, greater malapportionment than in the respective lower house exists in the Australian Senate (30 per cent), the Legislative Council of Western Australia (around 25 per cent) and the Japanese House of Councillors (16 per cent in the constituency tier of the electoral system).Footnote 6

One might object that once we consider any deviations from equal legitimacy of the two houses, the upper houses of countries like Germany or the Netherlands might also be included in the analysis. Though not directly elected, their – formal and perceived – democratic legitimacy is quite high and might be on par with (some) directly elected but malapportioned upper houses. I am sympathetic towards extending the analysis in this way (cf. Ganghof Reference Ganghof2014: 656, n. 10). However, since I contend that we must see a certain type of bicameralism as changing the executive‐legislative system, consistency requires that I choose a restrictive operationalisation of upper house legitimacy. Analysing additional bicameral systems as semi‐parliamentary might be analytically fruitful, but it is no logical necessity in terms of our standard criteria for classifying political regimes and executive‐legislative systems.

The second element we will look at is upper house confidence. By the minimal definition of semi‐parliamentarism, all upper houses considered here lack a no‐confidence vote. However, an absolute veto over the budget can be used as a de facto no‐confidence vote. New South Wales, Victoria and Japan lack an absolute budget veto and thus come closer to the ideal‐type.Footnote 7 The other cases have an absolute budget veto and deviate more from it.

Third, the upper house's absolute legislative veto power (with the exception of the budget) is not part of the above‐proposed minimal definition of semi‐parliamentarism, but an important part of the underlying ideal of democratic delegation. If the lower house possesses absolute veto power, as it typically does, and the upper house lacks it, as in the Czech hybrid, the constitution itself makes it clear that the two houses are not equal agents of the voters. In contrast, I think that the absolute veto power of the lower house is no necessary part of semi‐parliamentary democracy. Since the lower house is the principal of the cabinet and may have substantial agenda‐setting and dissolution powers, a lack of veto power would not necessarily undermine its equal status. I will return to this issue later in the article.

In all minimally semi‐parliamentary cases, except Japan, upper houses do have absolute veto power. Even if a veto is formally absolute, though, it may be substantially weakened in the dispute resolution procedure between the two houses. The crucial question is whether dispute resolution can involve a joint session deciding a conflicted issue by simple or absolute majority and thus favouring the larger (lower) house. This is the case in the Commonwealth parliament and in Victoria. All other Australian states maintain the equality of veto power (Stone Reference Stone, Aroney, Prasser and Nethercote2008). Tasmania and Western Australia have no provisions for dispute resolution; South Australia's constitution provides for a double dissolution election but no joint session; in New South Wales persistent deadlock can only be resolved in a popular referendum in which the lower house is the agenda‐setter but both houses lose their veto power.

Table 1 is obviously a great simplification, but the overall picture is rather clear. New South Wales comes closest to the constitutional ideal‐type of semi‐parliamentarism, the Australian Commonwealth and Japan are farthest away; the other Australian states are in‐between. Note that this rough ranking does not imply the hypothesis that upper houses will be more assertive, the closer they are to the semi‐parliamentary ideal‐type. In all Australian polities, Westminster norms and conventions remain strong, and the legitimacy of the lower house is widely perceived as being superior (e.g., Reynolds Reference Reynolds2011). This is partly explained by the fact that Australian upper houses at the state level had a long anti‐democratic history and were only democratised rather recently – 1978 in the case of New South Wales (Clune & Griffith Reference Clune and Griffith2006). Another reason for the greater perceived legitimacy of the lower house is precisely its exclusive authority to dismiss the cabinet. This, I have argued, is a public misconception that political science should not replicate. After all, we do not question the democratic legitimacy of the assemblies in the United States, Uruguay or Switzerland because they lack a no‐confidence vote. The existence or lack of confidence authority does not matter for democratic legitimacy but for the executive‐legislative system.

Trade‐offs in the design of executive‐legislative systems

Semi‐parliamentarism is a particular instance of what constitutional theorists have called the ‘new separation of powers’ (Ackerman Reference Ackerman2000; see also Albert Reference Albert2010). Proponents of presidential systems often conflate the popular election of the chief executive with the branch‐based separation of powers, as if one could not be had without the other (Calabresi Reference Calabresi2001: 54–55). The analysis of semi‐parliamentarism makes clear that this is a mistake. This executive‐legislative system can achieve the main advantages associated with presidentialism, while avoiding some of its main downsides. I start with the balancing of the ‘majoritarian’ and ‘proportional’ visions of democracy and then move on to the independence of (one part of) the assembly on matters of legislation.

Balancing visions of democracy

Shugart and Carey (Reference Shugart and Carey1992: Chapter 1) argue that a parliamentary system of government exacerbates basic trade‐offs in the institutional design of democracy. Since voters elect only one agent – parliament – which then selects a cabinet, a stark trade‐off emerges between an ‘efficient’ government and a ‘representative’ assembly. The authors’ notion of efficiency relates to the so‐called ‘majoritarian’ vision of democracy (Powell Reference Powell2000). Their particular focus is on identifiability – that is, ‘the ability of voters to identify the choices of competing potential governments that are being presented to them in electoral campaigns’ (Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992: 9). ‘Representativeness’ has two different aspects. First, the institutional logic of parliamentarism weakens local representation. National policy concerns expressed by parties become paramount and the ‘assembly formally constructed to represent local interests … becomes principally an “electoral college” for determining which party holds executive power’ (Shugart & Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992: 10–11). Second, even if we understand representation solely in terms of programmatic party platforms, parliamentary government creates a strong trade‐off in the choice of the electoral system. A highly proportional electoral system leads to a representative assembly but thereby tends to undermine identifiability. Optimised designs of electoral systems may help to mitigate these trade‐offs in parliamentary systems (Carey & Hix Reference Carey and Hix2011; Shugart Reference Shugart2001), but the extent of this mitigation, as well as the costs and risks involved, are controversially discussed (Ganghof et al. Reference Ganghof, Eppner and Heeß2015; McGann Reference McGann, Nagel and Smith2013; Raabe & Linhart Reference Raabe and Linhart2017; St‐Vincent et al. Reference St‐Vincent, Blais and Pilet2016).

Shugart and Carey (Reference Shugart and Carey1992: 12–15) argue that presidential systems facilitate the balancing of conflicting design goals by allowing voters to elect two separate agents. Popular elections of a fixed‐term president can achieve the ‘majoritarian’ values of identifiability, accountability and (one sort of) cabinet stability, whereas assembly elections can be designed to maximise representativeness (see also Cheibub Reference Cheibub2006, Reference Cheibub2007; Mainwaring & Shugart Reference Mainwaring and Shugart1997: 453, 461).

Yet presidentialism's achievement of the majoritarian values comes at the price of concentrating executive power in a (single) individual. The identifiability of presidentialism ‘is of one person’ (Linz Reference Linz, Linz and Valenzuela1994: 12). Cabinet stability – to the extent that it exists (Pérez‐Liñán & Polga‐Hecimovich Reference Pérez‐Liñán and Polga‐Hecimovich2017) – is presidential stability, whereas the partisan composition of the cabinet may change frequently (e.g., Martinez‐Gallardo Reference Martinez‐Gallardo2012). Electoral accountability requires the president's re‐electability, but allowing (immediate) re‐election increases incumbency advantage and may reinforce executive power accumulation. Empirical studies suggest that this accumulation creates a greater and persistent threat of authoritarian takeover by the incumbent, relative to parliamentary and semi‐parliamentary systems (Svolik Reference Svolik2015). Functional alternatives to term limits are not easy to find (Ginsburg et al. Reference Ginsburg, Melton and Elkins2013). Moreover, even when a president is re‐electable, voters are required to wait for the end of the presidential term to demand accountability, whereas prime ministers can be made accountable to their parties at any time, which then become accountable to the voters (Linz Reference Linz, Linz and Valenzuela1994: 14). Independently elected presidents tend to weaken the party unity of governing parties relative to those in parliamentary systems ‘because they present a potentially competing source of directives against those of party leaders within the legislature’ (Carey Reference Carey2007: 106). They also contribute to weakening parties’ programmatic capacities – that is, to parties being ‘broad coalitions with diffuse ideological commitments’ (Samuels & Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010: 14).

A semi‐parliamentary system shares presidentialism's potential for balancing the majoritarian and proportional visions of democracy, while avoiding many of its negative consequences. Here, too, voters elect two agents: the two parts (houses) of the assembly. The part whose majority is fused with the cabinet – the lower house in the bicameral case – can be oriented towards the goals of ‘majoritarian’ democracy, but without undermining parties’ collective control over the chief executive. This part of the assembly is not merely an ‘electoral college’ for the prime minister, but rather a permanent confidence college. Its majority keeps the prime minister in power and is able to remove him or her at any time. Term limits are therefore unnecessary. The chief executive remains an agent of the party, which is accountable to voters. The other part of the assembly (the upper house) is similar to the assembly in a presidential system and can maximise representativeness. A highly proportional electoral system in this part of the assembly not only achieves a fair representation of existing parties, but by making it easy for new parties to form, it also helps to keep existing parties accountable and allows new interests and identities to come into play (Huber Reference Huber2012; McGann Reference McGann, Nagel and Smith2013).

Note how the three criteria of the minimal definition of semi‐parliamentarism are important here. First, the absence of popular executive elections is important for making the chief executive accountable to her party. Second, the equal legitimacy (direct election) of the two parts of the assembly matters, because with clearly inferior legitimacy, even an upper house with absolute veto power would usually need to practice behavioural self‐restraint to avoid constitutional reform pressures. Third, the upper house's lack of a confidence authority reduces the constraint the upper house puts on cabinet formation. When an upper house has confidence authority and favours certain cabinets over others, this is likely to create strong pressures for constitutional reform, as it did in Sweden (Eppner & Ganghof Reference Eppner and Ganghof2017). Institutional designers can avoid these pressures by ensuring a similar or identical composition of the two houses, as they have done, for long periods, in Belgium and Italy (Eppner & Ganghof Reference Eppner and Ganghof2017). Yet if congruence is necessary to stabilise the upper house, it cannot achieve better representation than the lower house after all. Achieving greater representativeness in a resilient manner requires upper houses to possess equal legitimacy but lack confidence authority.

Branch‐based power separation and coalition‐building

Mainwaring and Shugart (Reference Mainwaring and Shugart1997: 462) highlight another advantage of presidentialism: the assembly's independence in legislative matters. As representatives can act on legislation without worrying about immediate consequences for the survival of the government, ‘issues can be considered on their merits rather than as matters of “confidence” in the leadership of the ruling party or coalition’.

One normative argument for issue‐specific decision making is that it is potentially more egalitarian (Ward & Weale Reference Ward and Weale2010). In parliamentary systems, fixed majority coalitions tend to provide each party with informal power to veto any policy (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002). This may bias the lawmaking process towards the status quo or facilitate logrolls that move policy away from the majority (median) preference on a particular issue dimension. Such logrolls may also happen under (substantive) minority cabinets, because the opposition parties that keep the government in office demand policy gains on issues salient to them (Christiansen & Pedersen Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014). By making the proportional part of the assembly independent in legislative matters, semi‐parliamentary systems may facilitate flexible and issue‐specific decision making while avoiding the negative effects of a popularly elected president on parties’ unity and programmatic capacities.

Note two caveats, though. First, even minority presidents in presidential systems often build portfolio coalitions, partly because cabinet posts can buy policy support (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004). The same may happen in semi‐parliamentary systems, especially when the legislature is fragmented. To the extent that this coalition building establishes partisan veto players in the cabinet, some of the potential benefits of issue‐specific decision making may be lost. Second, the flipside of any branch‐based separation of powers is the possibility of deadlock. Yet deadlocks seem to be relatively rare, even in the case of single‐party minority governments under presidentialism (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004). The same seems to hold under semi‐parliamentarism (e.g., Clune & Griffith Reference Clune and Griffith2006; Ganghof & Bräuninger Reference Ganghof and Bräuninger2006; Russell & Benton Reference Russell and Benton2010; Smith Reference Smith, Clune and Smith2012). Moreover, much depends on the more detailed institutional rules. For example, the possibility of assembly dissolution may be less of a problem in semi‐parliamentarism (as compared to presidentialism), since the chief executive does not serve fixed terms. Hence, if dissolution requires simultaneous re‐election of both parts of the assembly, there is a way to resolve deadlocks without completely undermining the separation of powers. Furthermore, the part of the assembly with confidence authority (the lower house) need not possess absolute veto power over legislation. If the government's majority in the lower house cannot veto legislation but can threaten to dissolve the assembly, the situation resembles that of some minority cabinets in parliamentary systems (Becher & Christiansen Reference Becher and Christiansen2015) – with the important difference that voters can choose the cabinet party (and default formateur party) more directly than under parliamentarism. Deadlocks can also be resolved through referenda. If both parts of the assembly have the right to initiate a referendum on a deadlocked proposal, the separation of powers remains intact and the uncertainty about voter preferences may strengthen inter‐branch cooperation (Ganghof Reference Ganghof2016).

Given space constraints, I cannot analyse governments’ strategies and success in building legislative coalitions under semi‐parliamentarism in more detail. The next section shows how the semi‐parliamentary systems in Australia balance the proportional and majoritarian visions of democracy.Footnote 8

Normative balancing across executive‐legislative systems

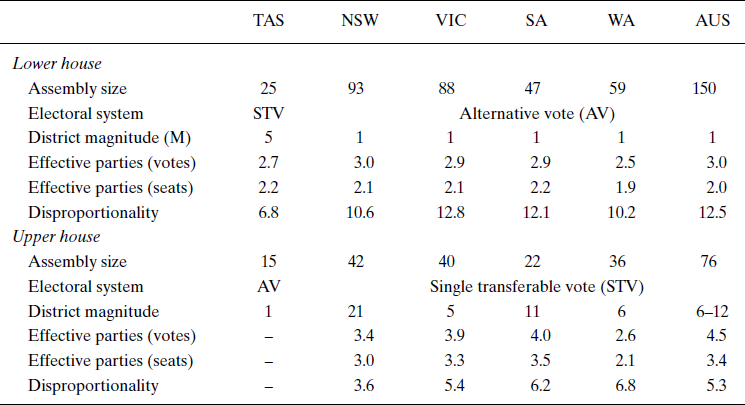

Let us start by summarising the electoral systems in Australia's bicameral systems. As Table 3 shows, Tasmania differs from the other Australian polities. It uses semi‐parliamentarism to achieve local, non‐partisan representation in the upper house (Sharman Reference Sharman2013). Alternative vote in single‐member districts (SMD) is one important element of this design; staggered yearly elections and a small assembly size are others (see Table 3). Partly due to these features, the Tasmanian upper house is dominated by independents. The resulting normative balance is that ‘[p]rogrammatic choices can be made through parties at lower‐house elections, supplemented with local representation through Independents in the upper house’ (Sharman Reference Sharman2013: 344).

Table 3. Electoral systems in Australia

Notes: All values are based on the latest election and, where necessary, author's own computations. Disproportionality is measured by the Gallagher (Reference Gallagher1991) index.

Sources: Author's own computations based on electoral statistics.

The semi‐parliamentary constitution is crucial for this equilibrium: if the upper house possessed the right to dismiss the prime minister, it would be democratically unacceptable that voters can never hold the upper house as a whole accountable for its actions and that these actions are not organised in terms of programmatic choices (cf. Fewkes Reference Fewkes2011: 91).

As to the trade‐off between ‘majoritarian’ and ‘proportional’ goals, Tasmania adopts the above‐mentioned ‘sweet spot’ (Carey & Hix Reference Carey and Hix2011) solution of using proportional representation (PR) in small districts in the lower house (all M = 5 since 1998). Indeed, it manages to have both a low effective number of legislative parties and low empirical disproportionality at the same time (see Table 3).

The more prevalent approach of using the semi‐parliamentary constitution exists in the other bicameral polities in Australia. It uses upper houses to achieve greater ideological, policy‐based representativeness. This strategy combines Alternative vote in SMD in the lower houses with Single transferable vote in upper houses. The degree of proportionality achieved in the upper houses varies due to the variation of assembly sizes and district magnitudes (Farrell & McAllister Reference Farrell and McAllister2006). Again, New South Wales stands out with the highest district magnitude and lowest disproportionality.

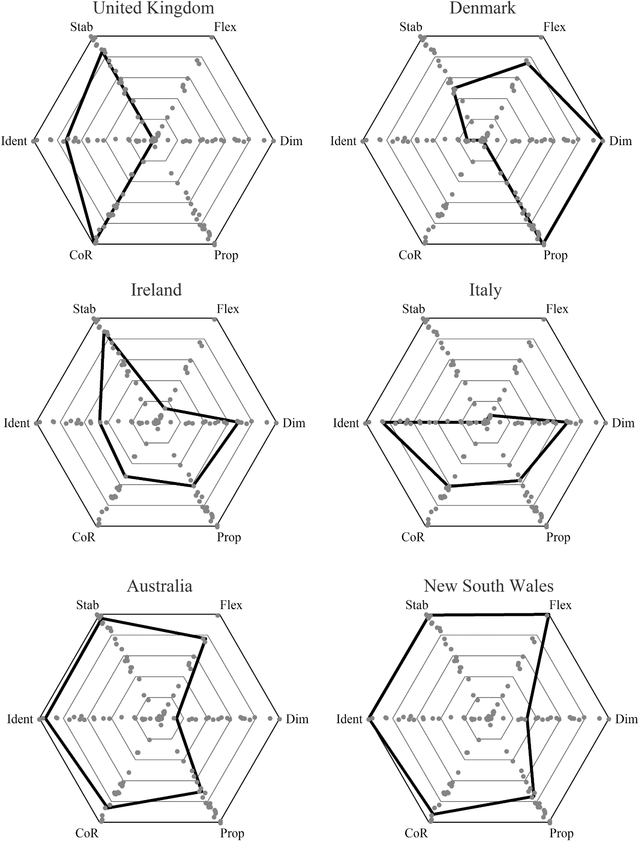

To map the normative balance achieved by these semi‐parliamentary systems more precisely, I focus on New South Wales and the Australian Commonwealth (for which expert estimates of party positions are available) and compare them to parliamentary and semi‐presidential systems. The results will also inform the comparison to presidential systems, as explained below. I compare these systems’ capability of simultaneously achieving six goals, three for each ‘vision’ of democracy (Powell Reference Powell2000).Footnote 9 The details of the six resulting indicators are provided in the Appendix. All of them take account of directly elected upper houses.

The three ‘majoritarian’ indicators are as follows. (1) Party‐based Identifiability (Ident) combines information on how much votes are concentrated on two competing pre‐electoral blocs, on whether the government consists of a single bloc and whether it has majority status (cf. Ganghof et al. Reference Ganghof, Eppner and Heeß2015; Shugart Reference Shugart2001). Since the focus is on party‐based identifiability, the indicator neglects presidential elections. (2) Clarity of responsibility (CoR) measures the ability of voters to determine which parties are responsible for past policies. The ranking of cabinet types is similar to the one proposed by Powell (Reference Powell2000: 53). (3) Cabinet stability (Stab) relates the average term length of cabinets to the constitutional maximum.

The three ‘proportional’ goals are as follows. (1) Proportionality (Prop) is simply the inverse of Gallagher's (Reference Gallagher1991) Least Squares index for the more proportional house.Footnote 10 (2) Dimensionality (Dim) is the effective number of dimensions (Ganghof et al. Reference Ganghof, Eppner and Heeß2015) in the house with higher dimensionality, based on expert survey data by Benoit and Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2006) as well as Pörschke (Reference Pörschke2014). This indicator captures the idea that if voters’ preferences are latently or potentially multidimensional – if their positions are ‘right’ on some issues and ‘left’ on others – then representativeness requires that this multidimensionality be reflected or constructed in the assembly (cf. Stecker & Tausendpfund Reference Stecker and Tausendpfund2016).Footnote 11 Finally, one version of the proportional vision wants to potentially allow all parties in the assembly to participate in decision making (Powell Reference Powell2000: 256, n.9). Hence, (3) legislative flexibility (Flex) measures – very roughly – the extent to which governing parties commit themselves to a fixed majority coalition or remain free to choose between different support parties.

Figure 1 presents the trade‐off profiles of six countries on these six variables for the period 1995–2015. All variables are period averages standardised between 0 and 1. This standardisation is based on the minimum and maximum values in a sample of 21 advanced democratic nation‐states plus New South Wales (see Appendix).Footnote 12 The figure also plots the distribution of values in this sample along the six dimensions in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Trade‐off profiles of non‐presidential democracies, 1995–2015.

The United Kingdom and Denmark exemplify the polar ‘visions’ of pure parliamentarism. They realise one vision at the expense of the other (cf. Powell Reference Powell2000). Ireland and Italy are examples of semi‐presidential and parliamentary systems, respectively, that try to balance the competing visions. The Irish strategy has been based on PR in moderately sized districts; the Italian on electoral systems that – until recently – encouraged the formation of competing pre‐electoral alliances. We see that both cases do have somewhat more balanced trade‐off profiles, but they are neither fully balanced nor do they achieve very high values on any variable (perhaps with the exception of cabinet stability in Ireland). New South Wales and the Australian Commonwealth represent semi‐parliamentarism. Both cases balance the two visions of democracy in that they realise the majoritarian goals about as well as the United Kingdom, but also reach high levels of proportionality and flexibility in their upper houses. They may only fall short, in comparison to PR‐parliamentary systems like Denmark, in representing the (potential) multidimensionality of voter preferences. However, this is not an inherent limitation of the semi‐parliamentary constitution but most likely a result of the path‐dependent designs that evolved in Australia. Most notably, the small sizes and/or district magnitudes of upper houses are likely to limit the effective number of parties and dimensions (Li & Shugart Reference Li and Shugart2016). The next section will discuss ways to reduce the constraint on dimensionality, if desired.

The empirical analysis also speaks to the comparison with presidential systems, even though they are not explicitly included. Students of presidentialism emphasise that in presidential systems identifiability is ‘institutionally guaranteed’ and that ‘presidential institutions provide a context of more “clarity of responsibility”’ (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2006: 361). Here we see that semi‐parliamentary systems can achieve equally high levels of identifiability and clarity of responsibility in a party‐based manner. Moreover, the next section shows that adequately designed semi‐parliamentary systems can also institutionally guarantee identifiability.

The design of semi‐parliamentary democracy

The bicameral systems in Australia have evolved in a long political process that often reflected the self‐interest of, and compromises between, partisan elites rather than some grand democratic design (e.g., Clune & Griffith Reference Clune and Griffith2006). If constitutional designers in other systems were to consider semi‐parliamentarism, which designs would be worth keeping, or changing? This section provides some preliminary answers.

Increasing upper house size

When we focus on the bicameral version of semi‐parliamentarism and the goal of balancing majoritarian and proportional democracy, the relative size of the two houses in Australia is the opposite of what would be desirable. If the lower house is most of all a ‘confidence college’ for the government, whereas the upper house assumes the role of the actual ‘legislature’, the latter should be larger than the former. A larger upper house would provide better conditions for proportional representation, multidimensional voter representation and scrutiny of legislation. Of course, the desirability of a smaller lower house also depends on the issue of constituency representation.

Constituency representation

There are good reasons to locate this representation, if deemed necessary, in the upper house (preferably in a form consistent with PR). For one thing, constituency representation would then be less constrained by the logic of parliamentarism. For another, lower house elections could be organised in a single district, based on absolute majority rule. Like presidential elections, lower house elections would then guarantee identifiability and allow all votes to count equally for the selection of the prime minister, regardless of where they are located. Consider, for example, a modified AV system in which voters rank all (closed) party lists in their order of preference, and the parties with the fewest votes are sequentially eliminated until only two parties are left. These parties would gain lower house (or ‘confidence college’) seats according to their final two‐party vote share (cf. Ganghof Reference Ganghof2016).

Unicameral options

As noted, bicameralism is not a necessary condition for semi‐parliamentarism. Since the members in a unicameral parliament have equal legitimacy, a differentiation of their right to participate in the no‐confidence vote would be sufficient to establish a semi‐parliamentary system. The most straightforward implementation would be to set two distinct legal thresholds. Consider the example of Germany, which currently has a 5 per cent legal threshold of representation. In the 2013 election, this threshold caused almost 16 per cent of voters to waste their votes on parties that gained no representation, but it could still not prevent the formation of a Grand Coalition of the two major parties, the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats (Poguntke & Dem Berge Reference Poguntke and von Dem Berge2014). Had there been a 2 per cent threshold of representation (as in Denmark), and a 10 per cent threshold for participating in the no‐confidence vote, at least three more parties would have gained representation, so that proportionality and dimensionality would have increased (Ganghof Reference Ganghof2016). At the same time, only the two major parties would have had confidence authority, so the Christian Democrats would have been able to build a stable cabinet seeking issue‐specific support in a more representative assembly.

The number of parties with confidence authority would not have to be reduced to two for semi‐parliamentarism to be potentially useful. When party fragmentation in parliament is very high, as in the Netherlands after the 2017 elections, a moderate threshold of confidence authority might facilitate cabinet formation and governance without necessitating a higher threshold of representation.

Another unicameral option would be to rely on the mixed‐member electoral system. In Germany half of the members of parliament are elected from party lists, the other half by plurality rule in SMD, but without affecting overall proportionality. If the right to participate in the no‐confidence procedure had only been given to the SMD representatives, and the legal threshold reduced to 2 per cent, the results would have been essentially the same as in the previous scenario.

Single‐vote options

If constitutional designers are willing to give up explicit constituency representation, as they were in parliamentary systems like Israel or the Netherlands, a semi‐parliamentary system need not require voters to cast two different votes. Elsewhere I describe a combined AV/PR system in a single district: voters rank as many parties as they wish in order of preference, and while their first preferences determine the proportional composition of the assembly, their fuller preference rankings determine the two top parties gaining seats in the ‘confidence committee’. The seats in this committee are part of the two parties’ proportional seat share and thus have no effect on the overall proportionality in the assembly (Ganghof Reference Ganghof2016).

The example of the EU

Established democracies might be unlikely to switch to semi‐parliamentarism. Yet there are certainly systems for which some constitutional creativity seems desirable. The EU is an example (cf. Praino Reference Praino2017). As long as a common European currency exists, there is an urgent need to legitimise – and give voters a choice about – the European regime of economic governance. Political scientists have mainly discussed the parliamentary and presidential options of doing so, but both seem seriously flawed in the EU context. Given the fragmentation of the European Parliament, parliamentarism could easily result in a permanent ‘Grand Coalition’ of the two major party groups rather than giving voters a substantive choice between different mandates. Presidentialism, in contrast, could undermine, and forever prevent, what a democratic EU would desperately need: the emergence of truly European programmatic parties.

To see how semi‐parliamentarism might be attractive, consider the proposal of transnational lists for European elections (Leinen Reference Leinen2015). The basic idea is to elect a fixed number of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), say 20 or 30 per cent, in a single pan‐European district. Voters would thus have two votes, one truly Europeanised. One semi‐parliamentary option would be to give only the ‘Europeanised’ MEPs the right to participate in a no‐confidence vote against the European Commission. The elections to this pan‐European ‘confidence college’ or lower house could be based on absolute majority rule, thus giving all voters a clear choice between competing programmatic mandates. The election of the rest of the European Parliament (or upper house) could be based on PR in national or local constituencies.

Conclusion

Semi‐parliamentary government is a distinct and neglected type of executive‐legislative system that deserves consideration by scholars and constitutional designers alike. Parliamentary systems struggle with the tension between the proportional and majoritarian visions of democracy, and semi‐parliamentary government is one approach to balancing these visions. Presidential systems struggle with the various negative effects of a popularly elected, fixed‐term president, and semi‐parliamentarism is one approach to avoiding these effects while maintaining or strengthening the advantages of a branch‐based separation of powers highlighted in the literature.

One question for further research is how, and how successfully, legislative coalitions form under semi‐parliamentarism. Another is how well semi‐parliamentary systems perform in the sense of producing good outcomes. A recent study by Schwindt‐Bayer and Tavits (Reference Schwindt‐Bayer and Tavits2016: 56–57) argues that high clarity of responsibility reduces corruption, and they single out Australia as a democracy that was more effective in fighting corruption when it was governed by single‐party majority cabinets – despite the fact that these cabinets usually lacked a majority in the proportionally elected Senate. While this is just one example, and perhaps a contestable one, it suggests the possibility that semi‐parliamentary systems may combine certain performance advantages of ‘majoritarian’ and ‘proportional’ democracies. This possibility deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The work on this article profited from a research stay at the University of Sydney from August to October 2016, and I would like to thank Anika Gauja and Rodney Smith for their generous help and hospitality. Portions of the article were presented at the Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg, the University of Osnabrück, the Australian Political Science Association conference 2016 in Sydney and the New South Wales parliament (sponsored by the NSW section of the Australasian Study of Parliament Group). In addition to the audiences and panel members at these events, I am grateful to Joachim Behnke, David Blunt, Scott Brenton, John M. Carey, Flemming J. Christiansen, David Clune, Sebastian Eppner, Gareth Griffith, Florian Grotz, André Kaiser, Simon Hix, J.D. Mussel, Alexander Pörschke, Stephen Reynolds, Fritz W. Scharpf, Stefan Schukraft, Campbell Sharman, Rodney Smith, Christian Stecker, Bruce Stone, Dag Tanneberg and John Uhr for helpful feedback and comments. I would also like to thank my interviewees (representatives and staff members) at the Australian Senate and the Legislative Councils of New South Wales and Victoria for their time and input. Special thanks to Sebastian Eppner and Alexander Pörschke for their contribution to the gathering and analysis of the data for this article, and to Leon Gärtner and Christian Lange for excellent research assistance. Any remaining shortcomings are my responsibility. Funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged (GA 1696/2‐1).

Appendix: Sample, measurement and sources

Note: Sample consists of: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New South Wales, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom.