A city comes to be as the product of social interactions, processes that take place in public. Many of those sociabilities are contested or unfold under unequal relations; this is perhaps nowhere as clear as in the case of colonial cities, whose racial hierarchies leaned on global systems of exploitation. Historians have sought to understand these manifestations of urban proximity under colonial rule, often building on Jürgen Habermas’ influential discussion of the ‘bourgeois public sphere’, while also seeking to challenge the limits of that model, developed largely based on an interpretation of European experiences.Footnote 1 Many have argued that colonial publics were particularly marked by their internal diversity: their polyvalence and lack of homogeneity, as phrased by Neeladri Bhattacharya in his analysis of the public sphere in India under British rule; or the ‘compound, syncopated and polyphonic’ characteristics identified by Rachel Leow in her work on the Chinese press in early twentieth-century Southeast Asia.Footnote 2 As Mark R. Frost has argued, these heterogeneities arose from conditions that were both local and global, as a product of transnational imperial flows of exchange.Footnote 3

To understand the polyphony of colonial urban sociability, it is necessary to understand the concrete setting where it took place: the city and its neighbourhoods. One common feature in analyses of the public sphere deriving from the Habermasian model has been an emphasis on the public as an ‘(ideal) communicative sphere’ rather than as a physical space, as noted by Susanne Rau.Footnote 4 Scholars have tended to embrace abstract spaces and media as the site of the public but given relatively less consideration to the concrete situatedness of public exchanges in specific sites. Yet, as Emma Hunter and Leslie James point out, the two are interconnected in their spatiality: ‘space is filled, whether on a printed page, in a public space, on the airwaves or a video, to attract and satisfy participants’.Footnote 5 Another way to think about this is Yi-Fu Tuan’s concept of ‘experiential space’, where ‘space is transformed into place as it acquires definition and meaning’: a neighbourhood, as Tuan points out, is a concept rather than a reality, and the residents’ willingness to embrace that concept depends on its experiential content, from community-building to outside messaging to public rites and rituals.Footnote 6 However, the role of concrete urban spaces and spatial relationships in the construction of colonial publics has thus far remained underexamined, a gap that this article seeks to address.

Following Susanne Rau and Richard Rodger, the analysis below will seek to bridge the gap between the city as a site and the urban as a mode, interpreting the ‘city as a space’ through ‘a nuanced account of the urban as a process’.Footnote 7 To do this, the discussion below examines the question of urban proximity from the point of view of the co-presence of several partly overlapping cultures, analysing the staging of colonial sociability in nineteenth-century Batavia as a spatial process. It is argued that the space of the city needs to be understood as not just a passive framing, but an active participant in the construction of the colonial public. Intricately choreographed moments of ceremonial exposed the colonial authorities’ thinking over who was allowed to do what and where, and crucially, with whom, setting norms for acceptable forms of engagement and sociability between communities that were tied to specific sites and neighbourhoods. Yet, these moments of heightened interest and sensitivity also provided opportunities to challenge and renegotiate top-down visions of urbanity. In order to provide focus to the argument, the analysis below will focus on two major case-studies: firstly, the 250th anniversary of the founding of Batavia held in 1869; and secondly, the festivities celebrating Queen Wilhelmina’s accession to the throne upon turning eighteen in 1898.

Batavia experienced significant growth over the second half of the nineteenth century: census data from 1847 put the total population at just under 60,000; by 1900, the figure had almost doubled, to roughly 116,000.Footnote 8 Like many colonial cities, this population was highly diverse, with the Europeans a minuscule minority – 3,000 and 9,000, respectively, over the same period. This fact caused no little consternation to the Dutch authorities, always fearful of unrest and rebellion. Alongside the local Sundanese and Javanese populations lived communities from all over the archipelago and further afield. Administratively, a distinction was made between the indigenous population (inlanders or ‘natives’) and so-called ‘foreign Orientals’ (vreemde oosterlingen), the latter group consisting primarily of the Chinese and the – far less numerous but growing – Arab communities.Footnote 9 The Chinese presence, in particular, predated the arrival of the Dutch and played a key role in the expansion of the city, crucial to the functioning of its commerce and industry.Footnote 10 That importance was reflected in the colonial authorities’ attitude towards these communities, marked by dependence on the one hand and distrust on the other.

This article aims to provide a new perspective on Batavia’s urban history by showing how this uneasy balance between need and fear, inclusion and exclusion was also stamped on Batavia’s public culture. Much of the extant historiography has focused on Batavia’s administrative structure, examining the systems set up to manage the city’s ethnically diverse population. As a means of imposing control over the people, although in some cases also as a result of more informal processes of self-segregation, the city’s communities were divided among ethnically defined neighbourhoods or kampungs from early on in the seventeenth century. These were originally clustered around specific grachten or canals, with names like Javase gracht, Chinese gracht, Moorse gracht or Maleise gracht indicating the respective groups.Footnote 11 After riots in 1740 and the bloody massacre of the Chinese that ensued, another kind of neighbourhood was established outside the city walls: the separate Chinese quarter known as Glodok that exists to this day.Footnote 12 Under the wijkenstelsel or ‘quarter system’ formalized in the early nineteenth century and maintained until 1919, specific communities were forced to live within the boundaries of specific neighbourhoods, creating the outline of a segregationist urban structure. Yet, as many authors have noted, enforcement was often patchy: social class played a big role in determining one’s opportunities and intermarrying also made it difficult to maintain strict boundaries between the groups in practice.Footnote 13

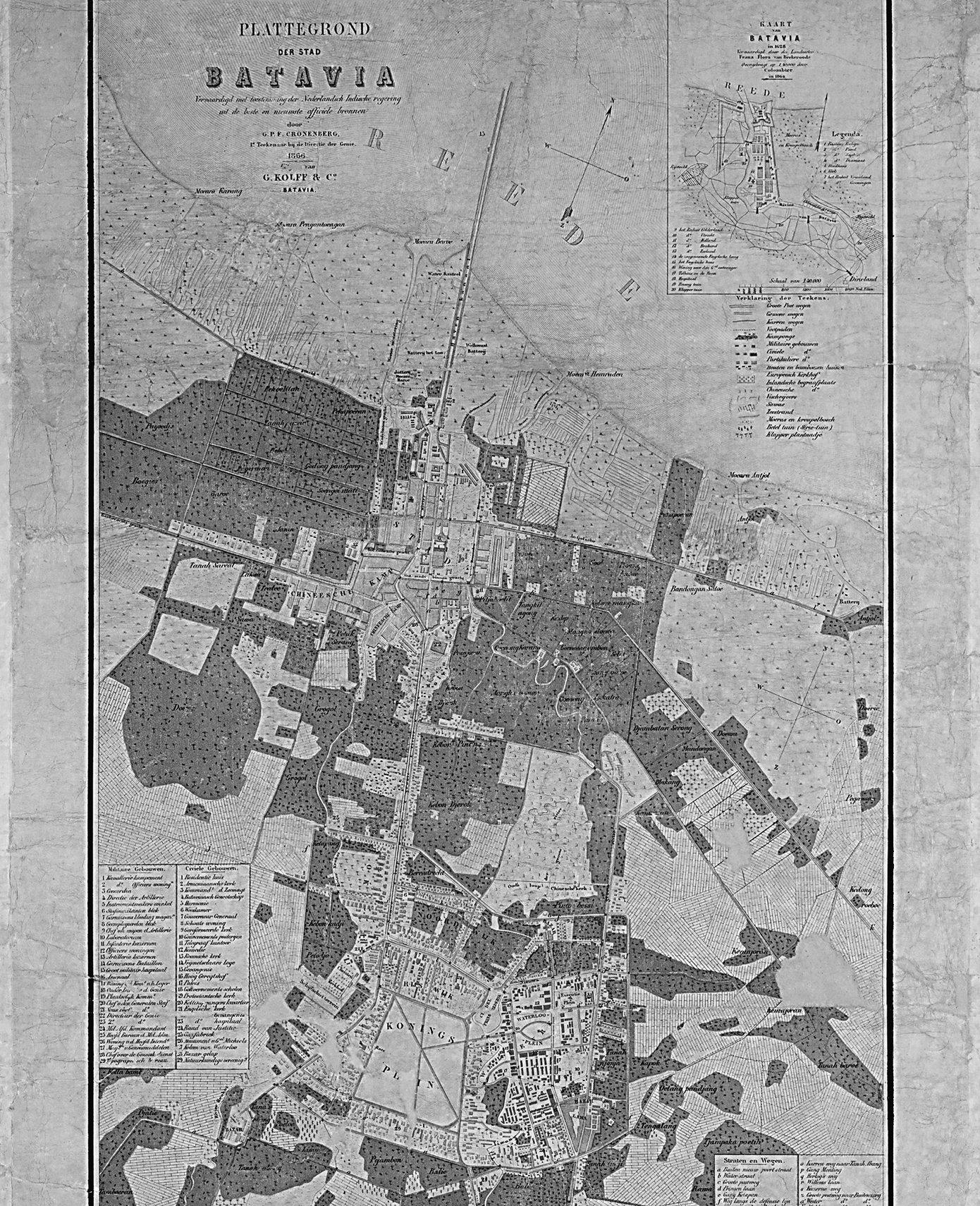

Beyond individual communities, the overall spatial organization of Batavia underwent a major change in the early nineteenth century with the creation of a new administrative centre south of the old town in an area named Weltevreden (Figure 1). This site accommodated the governor-general’s palace as well as the military headquarters and a variety of social and cultural institutions catering to Batavia’s European elites; unsurprisingly, it soon came to be the most desirable residential area for those elites, at a remove from the city’s Asian neighbourhoods. The process of southward expansion was therefore accompanied by an exodus of Europeans from the old town core up north, replaced there with a mix of Asian communities.Footnote 14 As will be demonstrated, this reorganization of the city was closely reflected in the ceremonial order that the festivals analysed below embodied; yet that order also worked in important ways to impose specific interpretations on this new spatial arrangement and to outline new and shifting meanings on its functionally and demographically varied parts. It was, in part, the ceremonies themselves that turned a varied conglomeration of kampungs, quarters and residential areas into a legible system of neighbourhoods with a shared, if contested, public culture.

Figure 1. A cropped map of Batavia from 1869 showing the city’s division into the northern old town near the port and the southern new town around the large Koningsplein square in Weltevreden. Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, KK 161-01-08. Public domain.

The analysis is divided into two sections, each dealing with one of the case-studies introduced above. The discussion will be guided by two research questions. Firstly: how was the design of the component events of each festival intended to cater to specific urban demographics? And secondly: how did the spatial distribution of the ceremonial programmes both reflect and reshape the spatial relations of colonial Batavia and its public life? The discussion will focus particularly on the changing norms around desirable and undesirable forms of public engagement, both between the populace and the colonial order, and between the city’s many communities. Throughout, close attention will also be paid to how the colonial vision of urbanity was contested from below, seeking to identify spaces – both literal and metaphorical – of grassroots agency. Overall, the analysis reveals a significant shift over time in Batavia’s norms of urban sociability and notions of the colonial public, moving from a spatially centred and culturally tightly European-coded ceremonial order to one that encompassed the whole city and a range of cultural idioms, although still bound in the straitjacket of colonial hierarchies. In order to survive, empire found – had to find – new ways to celebrate itself in the city.

Constructing a ceremonial core: the 1869 anniversary of Batavia

The 250th anniversary of Batavia in 1869 was a major showcase of Dutch colonial ceremonial, a massive multiday event that took almost a year to organize. The anniversary celebrated specifically and exclusively the Dutch colonial capital of Batavia, which had been built on the site of an earlier settlement, a Sundanese port named Sunda Kelapa or, later, Jayakarta. Apart from the shared location, however, there was limited continuity between the two towns, as the Dutch razed most of Jayakarta to the ground. The anniversary was therefore also, in effect, a celebration of Dutch imperial expansion and colonization writ large, commemorating their arrival in the archipelago at the turn of the seventeenth century.Footnote 15 The event was also the topic of some controversy among the Dutch elites, as a rift opened up between the city’s liberals and conservatives regarding the suitability of centring the festivities on the despotic and bloodstained figure of the city’s founder figure, Jan Pieterszoon Coen.

Despite such squabbles, the anniversary’s significance as an embodiment and entrenchment of the city’s ceremonial order was undisputable. The component events and their chosen venues constituted a deliberate staging of what were deemed to be acceptable sites of urban sociability, as well as a spatial configuration of the very concept of the colonial public. The programme of the anniversary consisted of several events spread out over four days between Saturday 29 May and Tuesday 1 June.Footnote 16 These included the laying of a foundation stone for a statue of Pieterszoon Coen, accompanied by music and speeches; a concert including contemporary European music and a specially commissioned cantata, a triumphalist recounting of the city’s colonial history. There was a flower show and an intended fireworks display, although this was postponed due to inclement weather. The celebration concluded with a costume ball and supper. In addition, on all three days in the mornings and afternoons there were so-called volksfeesten (folk festivals), consisting of sports competitions in things like running, mast-climbing and horse racing.Footnote 17

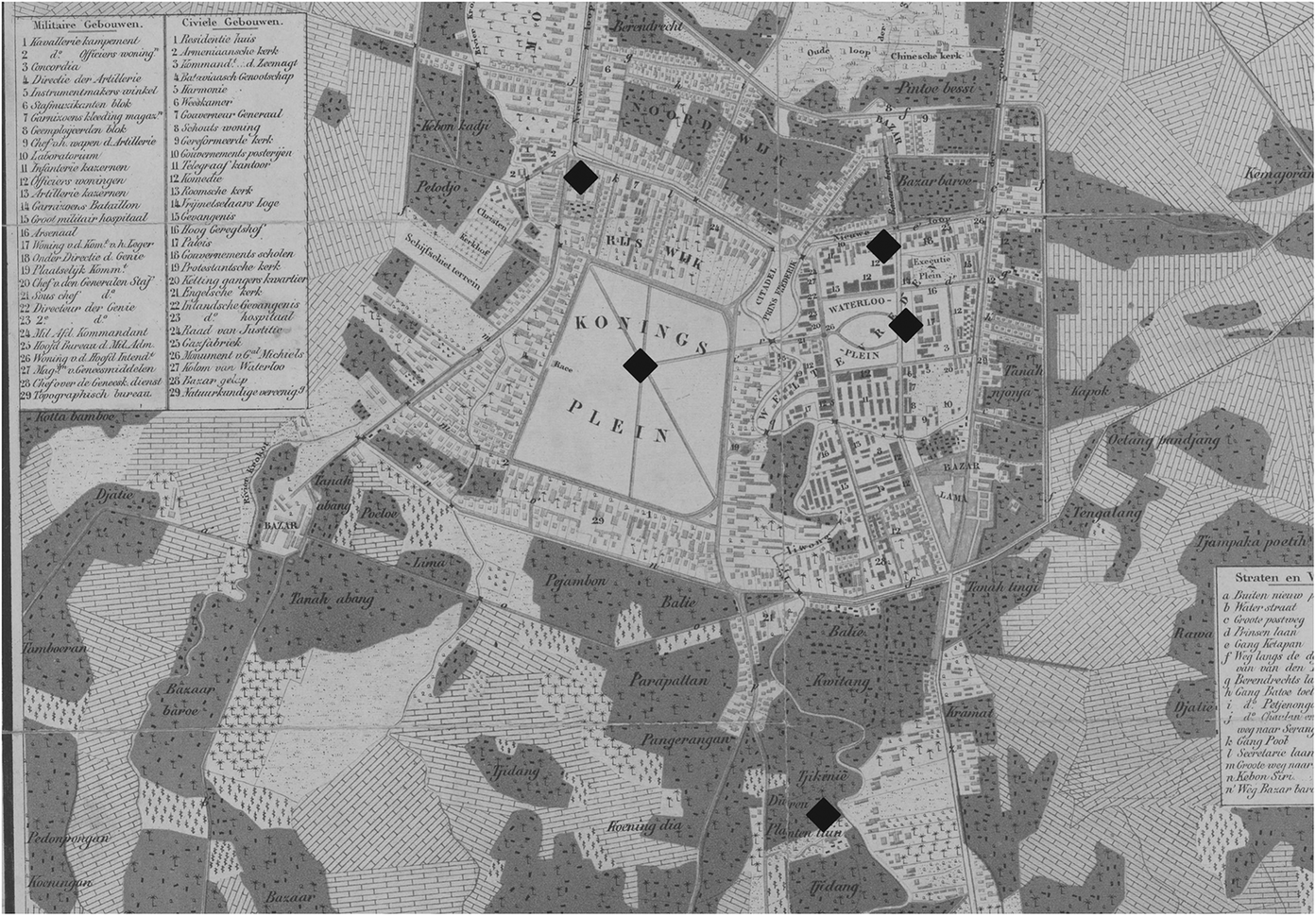

Within the space of the city, the events were clustered within a limited area centred tightly around the Koningsplein (Royal Square) in the Weltevreden neighbourhood, as can be seen from Figure 2. This constituted a determined effort to cast this area as the ceremonial core of the city, with a range of public spaces employed for different kinds of events; the outer neighbourhoods, with their more diverse populations and sociabilities, were absent in this vision. The venues employed consisted of: the park area containing a zoo and a garden (Planten- en dierentuin) to the south-east of Koningsplein, for the flower show and the fireworks display; the Harmonie clubhouse, at the north-west corner of the square, that hosted the concluding ball and supper; the Waterlooplein, a little to the north-east, where the Coen statue was to be raised and the opening speeches held; and nearby, the Schouwburg or theatre, where the concert was held. The vast open area of the Koningsplein itself was a natural choice for the site of the sports events held on multiple days.

Figure 2. A crop of the map in Figure 1, focused on the Weltevreden neighbourhood in Batavia’s new town, showing the locations of the various component events of the 1869 anniversary.

While the anniversary thus spread out over multiple locations, these venues were not merely closely clustered geographically but also highly uniform in design and purpose, embodying a specific mid-nineteenth-century European-coded middle/upper-class sociability. This was also reflected in the design of the buildings themselves: the Harmonie clubhouse (completed in 1814, see Figure 3), the theatre (1821) and the Daendels Palace (1828) dominating the Waterlooplein are all typical examples of the neoclassical, whitewashed and porticoed style of Dutch colonial architecture of the time, drawing on European cultural history for their visual reference points. The first two buildings (the Daendels Palace was used by the administration) in particular existed to serve the social and cultural needs of the colonial administrators and merchants living in the Weltevreden area, and while access was not strictly racially exclusive there was certainly little effort to attract a wider or more diverse audience or membership.

Figure 3. The Harmonie clubhouse, completed in 1819, that served as a centre of the social life of Batavia’s colonial elites. Photograph by Woodbury & Page (before 1880). Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, KITLV 26619. Public domain.

The zoo and gardens represented a more recent addition to the neighbourhood’s public life, having been opened in 1865. Though in theory an institution with scientific aims, in practice the grounds played at least as important a role as a social space. For example, the society’s first annual report in 1866 devotes ample space to describing the success and the ‘delightful tones’ of the weekly concerts given by the military band and the special Easter and Pentecost matinées; and to the planned future addition of outdoor dances to attract ‘the ladies of Batavia’ and vauxhalls ‘that evidently appeal to the tastes of the public’.Footnote 18 This mixing of a civic, educational ethos with middle-class entertainment and casual socializing embodied a new step in the city’s public life, also apparent in the opening of the museum of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences just a few years later in 1868. Compared to the earlier generation represented by the clubhouse and the theatre, the zoo also served to bring European-coded sociability into wider, outdoor vistas, facilitated by careful gardening and the introduction of gas lighting, which was heavily recommended by the society leadership as enabling the extension of socializing into the early tropical nights.

Analysing this variety of activities and venues as a cross-section of desirable colonial public life – as envisioned by the anniversary’s organizers – it becomes evident that each component event was deliberately designed to attract and engage specific demographics within the city’s diverse population. Most of the attention was on the higher echelons of the city’s colonial hierarchy, and nowhere was this more apparent than in the costume ball that formed the culmination of the festivities, designed as a glamorous showpiece for Batavia’s beau monde. Reports focused on the luxurious splendour of the costumes on display; while outside, armed cavalry with drawn sabres was deployed to keep guard and ensure order among the curious masses there gathered, both ‘European and native’, according to an eyewitness.Footnote 19 Such an arrangement laid bare the division between insider and outsider in the public life of the colonial capital.

Yet, the expected insulation of the elite from the non-elite was only one of many ways of categorizing Batavia’s population. Ethnicity played a major role in these schemes, most obviously in the case of the volksfeesten, which were explicitly directed towards the city’s non-European inhabitants, or, in the colonial administration’s language, the inlandsche bevolking (‘native population’). The usage of this crude category was a routine practice, and these communities, whether Javanese, Sundanese or other, were often treated by the Dutch as a monolithic, faceless block living a separate life within the city. Accordingly, the volksfeesten were also conceived of as a parallel celebration alongside the proper ceremonies organized for the European inhabitants. As much is evident from the fact that the sports events were not even included in the official programme booklet of the anniversary, although they were publicized in the press. The sports included non-specified inlandsche volksspelen (‘native games’) while the regulations for the horse racing specified that horses had to be both ridden and owned by inlanders. Alongside the sports, the organizers also held a twice-daily lottery ‘for the benefit of the wives and daughters of native residents’, with prizes including sarongs and ticket books for the tramway; free tickets for these lotteries could be collected from the wijkmeesters or heads of the ‘native neighbourhoods’. In fact, ticket distribution was the only mechanism that extended the otherwise highly spatially centred celebrations outward from the new town and into the kampungs.

Another example of the event-by-event calibration of the anniversary to target specific demographics is provided by the flower show, which notably sought to engage the (middle- and upper-class) women of the city. One of the organizers referred none too subtly to this gendered nature of the event by framing it as an opportunity for ‘wondering at God’s greatness in the delightful diversity of plants, flowers and fruits (not to mention his most beautiful creations)’.Footnote 20 The show and competition worked on the basis of specimens – both flowers and food crops in 27 categories – sent in by people ahead of time and then evaluated by a jury at the event.Footnote 21 And while the list of prize winners is dominated by men, the report of the event foregrounds women instead: a Mrs Junius van Hemert for her two flower bouquets and a Mrs Levyssohn Norman for a pyramid-shaped display of fruit, as well as a Mrs van Hoek for a collection of fruit in wax.Footnote 22 Indeed, there is some reason to suspect a greater share of the effort fell on women than the prize list suggests, as the two former ladies appear on a different newspaper’s list under the names of their husbands.Footnote 23 This emphasis on (elite) women and their active participation in public life reflected a broader ideological change in the culture of the time, favouring European-coded and family-friendly norms of public behaviour among the white population in order to fight off persistent accusations of the moral corruption of colonial life.

The festival also gestured towards inclusion on a more official level, assigning a place of honour in the governor-general’s immediate company to the Javanese nobility invited to the laying of the foundation stone. Such a gesture was naturally intended to buttress the legitimacy of Dutch rule by arranging a public display of Javanese acquiescence to it. Or, as a rather fanciful letter in the conservative newspaper Java-Bode put it, an occasion for the Javanese princes to prove by their presence their ‘great fondness for the brother from the West’.Footnote 24 The statue itself became, in the process, a double symbol for both military conquest – framed as a past event although in reality still ongoing – and for political and cultural integration. The author also invites ‘the Javanese and the Sundanese’ to ‘join us on the evening of the costumed ball’, underlining the significance of these transposed, Western-coded spaces of public sociability in the Weltevreden core as sites of integration and reconciliation. In the ceremonial order, it was the pre-scripted role of the colonial subject to arrive in these hand-picked spaces in order to become a part of the colonial public, whose boundaries were jealously guarded.

It is difficult to say with certainty what kind of response the anniversary celebrations received from the wider population of the city, although the location and content of the events were hardly designed to attract broad audiences. This was reflected in contemporary reporting. One commentator drew attention to the limited spatial reach of the festivities, noting the ‘deathly quiet in the streets of the old town’ with ‘everything closed, the houses depopulated’ in contrast to the ‘life’ and ‘merry, excited atmosphere’ of the Weltevreden area.Footnote 25 As for the interested demographics, an anonymous eyewitness remarked that ‘the whole morning one saw barely a single Native or Chinese or Arab without an official function, such as that of a police orderly (politie-oppasser), out on the streets’.Footnote 26 They also quipped of the sports events later that day that they were ‘real folk-games without the folk’ (echte volksspelen zonder volk).Footnote 27 Success appeared to have been limited.

Given the divisiveness of the celebrations among the city’s elites, it is possible that a disgruntled opponent may have sought to exaggerate their failure, although it is notable that a contemporary report in the Singapore press did indicate a similar lack of popular interest.Footnote 28 Other accounts were favourable or at least elided the question of participation, but these critical voices do draw attention to an important point: at a show put on by colonial authorities to legitimize their rule, at least partly dependent on the audience for its success, the people of the city could weaponize their passivity and non-participation as a deliberate withholding of support. The colonial public, contested at its core, was constructed not merely through actions that filled up space but also through inaction and emptiness.

Not that all the contestation was of the strictly passive kind. Further away from the city’s core, April 1869 had seen a violent episode in Bekasi, a village some 20 kilometres east of Batavia. Local displeasure with how the authorities handed out preferential land rights to Europeans in Batavia’s so-called Ommelanden or hinterland escalated into bloodshed, with multiple deaths on both sides; and while the event itself was long past by the time of the anniversary, it came to cast a heavy shadow over the proceedings.Footnote 29 Rumours of further violence and outright rebellion circulated among the European population and even the cancellation of the anniversary came under consideration. In the event, it did go ahead but under reinforced security measures: police controls were introduced to control the flow of people and there were even reports that the inhabitants of some kampungs were pre-emptively forced to hand out their kerises (daggers) to the authorities in advance.Footnote 30 The days passed peacefully, but the mere spreading of rumours by ‘malcontents and mischief-makers’, as they were labelled in the Straits Times, suggests that locals were aware of the significance of the occasion and found ways to organize a counternarrative to disrupt colonial ceremonial.Footnote 31 The public-ness of the festival, designed as a tool, turned into a weakness and an expression of friction.

Taken together, the component events of the anniversary worked to shape the evolving notions of urban proximity and the colonial public in the Dutch East Indies in at least two ways. Firstly, the range of events worked to create norms of active and passive engagement with the colonial order, tied to specific public spaces and ways of being. On the one hand, the events discussed above – the sports competitions, flower show and masked ball – provided the public with means to actively participate in and engage with the celebrations, carefully directed to specific modes according to ethnicity, gender and class. On the other hand, passive audiences were invited to witness the lengthy speeches at the statue site, and the evening concert. These were occasions for one-way message projection where the role of the public was to observe and, at most, applaud to show their support, thereby legitimizing the performance. The events laid out the strict rules under which proximity could be allowed to resolve into practices of sociability within the colonial city.

Secondly, the events also comprised a tiered system of public and semi-public spaces of varying exclusivities. Access to most events was controlled by ticketing regimes that discriminated on at least two levels. Price, naturally, provided one hurdle, and served to indicate the differing status of events: the open-air events – stone-laying, fireworks, flower show – had a price of 2 guldens per adult; whereas the concert ticket cost 5 guldens. The most elite occasion, the ball, had an entry price of 10 guldens.Footnote 32 Not everyone had to pay, however. At one end of the social ladder, the sports events, meant for the undifferentiated ‘native’ population, had no ticketing at all. And at the opposite end of the spectrum, high-level officials were personally invited to take part, while members of elite clubs, such as the military society Concordia, also had free access to specific events. All of this created a strict hierarchy of access calibrated around specific venues. Crucially, all sites were located within the Weltevreden area, which became a staging ground for an idealized version of colonial urbanity; the reality of life across Batavia’s diverse neighbourhoods was noticeably absent from this vision.

Yet these processes of legitimization and hierarchy-building, although controlled from above, could be disrupted. The widespread alarm occasioned by rumours of unrest represented a failure on the part of the Dutch authorities to fence the Weltevreden neighbourhood into a controlled environment, a kind of outdoor display of ideal colonial relations where everyone could be assigned a place and a role to play. Instead, the outside could not be stopped from coming in, the reality of colonial life inevitably taking centre stage as the violence inherent in the land regime of the city’s immediate surroundings was turned against the colonizer at its centre. The presence and absence of weapons came to symbolize the spatiality of the colonial city, in the sabres drawn to protect the Weltevreden elite’s clubhouse while the kerises of untrustworthy neighbourhoods were collected and locked away. Even the pressing emptiness of the central squares and fields devoid of the participants who refused to arrive from the kampungs was an embarrassment, underlining the need to rethink Batavia’s ceremonial order in the decades that followed.

Expansion and inclusion? The inauguration of Wilhelmina in 1898

In 1898, Batavia was once again the venue of major festivities. This time, the cause for celebration was empire-wide rather than centred on the city itself: the accession to the throne, upon turning 18, of Queen Wilhelmina. In many ways, the ceremonies in Batavia and elsewhere in the Dutch East Indies reflected those in Amsterdam, with a similarly lavish range of galas, decorations and processions.Footnote 33 The reflection, moreover, was not all one way: Wilhelmina’s inauguration was the first to feature indigenous representation from the colonies, with a contingent of four noblemen from Java, Sumatra and Borneo present in the Netherlands for the occasion.Footnote 34 The event thus entwined metropole and colony in both capitals, embodying the empire in the person of the young queen. This was far from accidental, Wilhelmina’s public profile having been carefully calibrated to serve the needs of the monarchy from a very young age, as Susie Protschky has noted.Footnote 35

Compared with the 1869 anniversary, the festivities in Batavia had been designed to show far greater participation in the ceremonies from people across the city’s communities. Moreover, this increased demographic diversity went hand in hand with a noticeable spatial expansion of the ceremonies throughout the city. The main ceremonial days were 30 August and 6 September, the days of Wilhelmina’s accession and official inauguration, respectively.Footnote 36 The programme spread out between these dates was reminiscent of 1869, although on a grander scale.Footnote 37 There were, for example, four separate balls, with costumes and without; sports competitions were organized on the Koningsplein as before; and there were also several fireworks displays and musical or operatic performances. An unveiling of a monument also took place, although not one dedicated to the queen. Instead, the sculpture commemorated the bloody, decades-long and still ongoing war of colonial expansion in Aceh on the island of Sumatra, but it was located in the newly designated Wilhemina Park, thus unsubtly eliding the royal and the colonial in the event’s ideological framework.

For all the evident similarities with the earlier anniversary, the 1898 celebrations reflected a meaningful shift in the city’s ceremonial order and in the expression of imperial legitimacy through urban form. This shift is captured well in the photographs of the festivities taken by the Batavia Chinese photographer Tan Tjie Lan. One of these (Figure 4) depicts a ceremonial gate in Chinese style erected for the occasion, possibly at the market in Pasar Baru. The assemblage shows a striking juxtaposition between the gate with its dragon motifs and the Dutch flag flying above in the background – a radical departure from the overwhelmingly European-coded ornamentalism of the 1869 anniversary and a striking new vision of a different kind of multiethnic empire embodied in the colonial cityscape. The ceremonial code of the mid-century had been replaced by a new language that was more fluid and open around its edges, better reflecting the internal diversity of the colonial capital. The city’s Chinese community had been invited to be a part of this celebration in a much more substantial way, a shift made all the more notable since the core of this celebration was rooted in the European past of the Dutch monarchy rather than in the colonial past of the city as in 1869.Footnote 38

Figure 4. A Chinese-style ceremonial gate erected in Batavia on the occasion of the 1898 festivities. Photograph by Tan Tjie Lan. Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, KITLV 114150. Public domain.

This new style of staging colonial ceremonial gained some resonance in the local Dutch press. One commentator in the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad praised the lively decorations set up by the Chinese community at Pasar Baru and other Chinese-dominated market areas throughout the town, making them appear ‘in festive attire’ that stood out among the ‘miserable barrenness of the surrounding neighbourhoods’.Footnote 39 The pseudonymous commentator singled out for praise the Chinese ‘major’ (community leader) Tio Tek Ho for his initiative in organizing the efforts and presented it as a sign of civic virtue and an exemplary fulfilling of a public duty that other, unnamed parties in the city could learn from. They note that the community had set up electric lighting at Pasar Baru at their own cost, and even go as far as to suggest that ‘everything shows that the Chinese have wanted to value this celebration more highly than any other ever given by them here’.Footnote 40 Clearly, then, the Chinese community did more than merely follow orders from above, and their participation was both active and internally well organized. Its motives are, of course, open to question: were these efforts a sign of true loyalty to a far-away monarch or merely a strategic play for social status and prestige in the city’s colonial hierarchy? Either way, the glowing commentary in the Dutch papers suggests that the latter goal was achieved, at least to an extent.

Greater diversity and participation were also evident in the individual component events, though coinciding with a strict division between European and Asian. This was evident in the design of the two ceremonial processions that took place on 1 September: a torch and flag procession followed by a soirée dansante for the European community; and a near-simultaneous ‘great Chinese and Malay procession through the lower and upper towns’. Importantly, though the administrative mindset preferred to keep the two categories ‘Chinese’ and ‘Malay’ separate, in practice any boundary was fuzzy at best due to extensive intermarrying in the local peranakan Chinese culture.Footnote 41 And the segregationist logic went beyond committee efforts and active participants, reaching also to the level of passive audience members. For example, in the run-up to the boat races held in the city’s port area, instructions were given out to revellers on how to proceed from the railway stop where they arrived from the city: Asian spectators, with the exception of dignitaries, were directed to the eastern side of the port and Europeans and guests of honour exclusively to the opposite side.Footnote 42 As a minor but telling organizational detail, the former were asked, upon arriving at the station on the primary, western side of the dock, to abruptly turn around and walk the long way around to reach their designated viewing areas. The cultural and social distinction between European and local was therefore strictly enforced in the ceremonial code, leaving little opportunities for mixing or interaction across cultural boundaries.

A notable new introduction were events specially designated for children, indicating that a whole new demographic had now entered the realm of ‘the public’, thus earning the right to be addressed. There were two of these events, both at the zoo gardens which therefore gained a specific association with familial sociability. On 1 September, the gardens hosted a groot kinderfeest (‘a great celebration for children’), which invited ‘all European children of Batavia’, with music, dancing, a steam-powered carousel and balloons among the entertainments provided. As many as 2,500 children took part in this event that was modelled after a similar kinderfeest held on the occasion in the Hague.Footnote 43 Two days later, the rest of Batavia’s youth got their turn, as a near-identical free event followed but intended exclusively ‘for the children of natives and foreign Orientals’. Balloons and the carousel were once again present but here all the music was provided by ‘native bands’ and the entertainments comprised of gamelan and wayang wong performances and topeng and barong dances. Not that European music was considered beyond the capacities of local children, just reserved for the select: the government disseminated the festival’s official songbook free of charge to Batavia institutes teaching locals.Footnote 44

The increased diversity of participants was reflected in the organizing committees, albeit in a limited fashion: out of the central committee and eight subcommittees, only the subcommittee for the volksspelen counted several non-Europeans among its list of members, as representatives of the ‘people’ of the city. These included the above-mentioned Tio Tek Ho and his officers, but also members of the Javanese nobility and the heads of the city’s ‘native’ districts as well as the ‘captain’ of the Arab community and the head of the ‘Moors and Bengalese’, an imprecise ethnic label that played more of a role in the city’s administrative structure than in reality. In sharp contrast to the 1869 anniversary, where the only non-European name on the committee lists was that of the famed Javanese nobleman and painter Raden Saleh, the 1898 celebrations made a distinct effort to involve the inhabitants of the outer neighbourhoods, largely through the mediation of their appointed community leaders. Yet, it would be an overstatement to suggest that they had much of a presence in the organizational effort writ large, being called upon instead to ensure a suitable display of loyalty at times and places dictated from above.

Clearly, the 1898 festivities had been designed to have the appearance of a common undertaking uniting the communities of the city. This overarching quality was also evident in the spatial design of the events: quite simply, the activities occupied a significantly larger share of the city’s map than had been the case in the earlier anniversary. If, in 1869, commentators had lamented the ‘deathly quiet’ of the streets outside the ceremonial core, by 1898, this observation was reversed: reports specifically emphasized how ‘not only the public buildings but nearly all the private houses and native kampungs were decorated with flags; all of Batavia was wrapped in festive dress’.Footnote 45 In the revised ceremonial order, the celebration of empire had become a matter for the whole city, cutting across the neighbourhoods instead of being restricted to just the ceremonial core of Weltevreden.

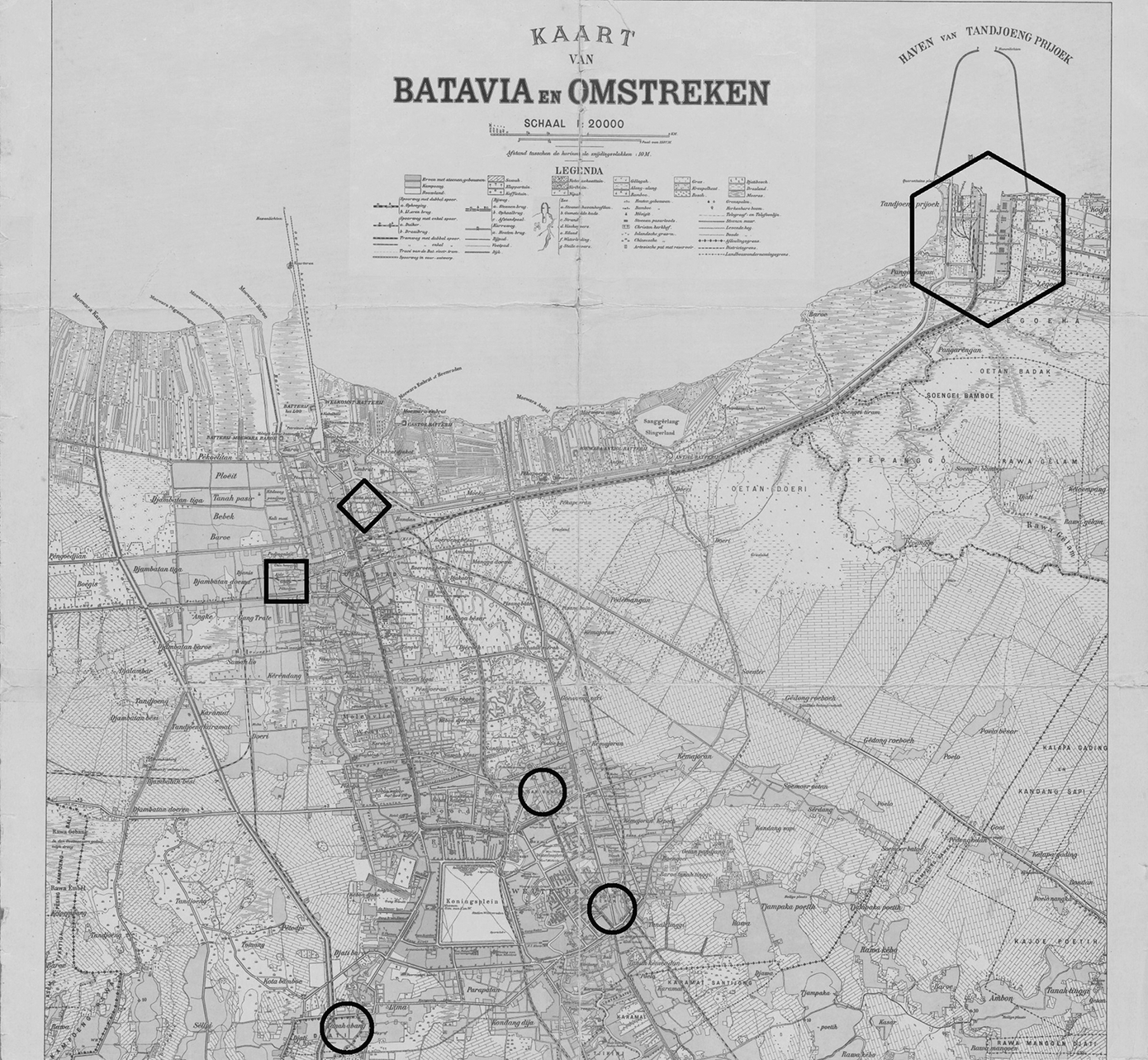

The praise garnered by the Chinese community has already been noted, but it is important to also consider the spatial effect of their participation. Under their major Tio Tek Ho, they organized to decorate not only the Chinese quarter near the old town, but also and more importantly the major market neighbourhoods where they tended to dominate trade. These were spread out on all sides of the central Koningsplein square: Pasar Baru to the north, neighbouring the Chinese graveyard; Pasar Senen a little further to the east; and Tanah Abang to the south-west (see Figure 5). This had the effect of surrounding the old ceremonial core of Koningsplein with a highly visible and culturally distinct Chinese presence, as in the gate photographed by Tan Tjie Lin. Nor was this merely a matter of flags and decorations, as specific events were also designed to take up space throughout the city’s neighbourhoods. The ‘Chinese and Malay procession’ noted above passed through both the old (lower) and new (upper) towns on its way to Pasar Baru, in a symbolic linking of the spaces – if not quite the peoples – of the city’s two halves. A similar linking of spaces took place with the boat races at the new port area of Tanjung Priok, which as a liminal space hosted not merely curious crowds on an outing from the city but also incoming foreign warships, including the British HMS Powerful bringing greetings from the neighbouring Straits Settlements, whose crews received free train tickets from the port to Batavia.Footnote 46 Batavia as a city of celebrations had undoubtedly become larger, its map filled out since 1869 and its connections to the outside world more firmly sketched out.

Figure 5. A cropped map of Batavia from 1897 showing the locations of selected events in 1898: the markets of Pasar Baru, Pasar Senen and Tanah Abang marked with circles; the Arab neighbourhood of Pekojan with a square; the old town with a diamond; and the Tanjung Priok harbour with a hexagon. Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, D E 24,7. Public domain.

The Chinese had of course formed the city’s pre-eminent – if often distrusted by the authorities – trading community for centuries, so their inclusion was arguably long overdue. However, another hotspot of this expanded version of Batavia’s ceremonial order showcased a more recent demographic change. This took place in the neighbourhood of Kampung Pekojan, to the west of the old town and neighbouring the Chinese quarter. Traditionally, this had been the home of the city’s non-indigenous Muslims or ‘Moors’, a vaguely defined Islamic community of mostly South Asian descent. Over the course of the nineteenth century, however, immigration gave the neighbourhood a predominantly Arabic character: by 1900, the city’s Arab population had come to form an important and influential trading community in their own right, numbering more than 2,000 – about a quarter of the European population although less than a tenth of the Chinese, as reckoned by census categories.Footnote 47 As the home of the great mosque (or masigit) of Batavia, Kampung Pekojan was a natural, major ceremonial centre for the city’s large Muslim population, something that the authorities sought to take advantage of.

Here, on 2 September, a prayer event took place for the benefit of the newly crowned queen, where ‘a colossal number’ of ‘the Mahommedans of Batavia’ gathered to hear, in Arabic and Malay, a prayer specially prepared for the occasion by the Pekojan-born Grand Mufti of Batavia, Usman bin Yahya, and printed and distributed at the cost of the government.Footnote 48 That same prayer was also read out at all mosques throughout the city and beyond, in a mirror image of the public prayers European churches were instructed to hold.Footnote 49 Pekojan, in turn, took on the role of a secondary centre of ceremonies next to the Koningsplein-centred Dutch cluster, with its own, parallel network of satellite locations throughout the city and beyond. And much like the Chinese major Tio Tek Ho, Usman bin Yahya managed to exploit his status as a community leader during these celebrations in order to buttress his standing in the imperial hierarchy, being awarded an Order of the Netherlands Lion on the occasion. Not that this manoeuvring was to everyone’s liking: shortly afterward, the Grand Mufti came under criticism from Arabs in Batavia and Singapore for his explicitly pro-Dutch stance.Footnote 50

The Islamic features of the celebrations, which had the effect of including the city’s population on a scale not even attempted in the 1869 anniversary, were not limited to prayers at mosques. There was also, a little further north near the old town port at Kota Inten, a grand sedekah (sadaqah in Arabic), or charity meal, held on 4 September. This occasion was also accompanied by music, dance and entertainments, with a Dutch newspaper praising the ‘excited atmosphere’ among the crowds streaming into the grounds. The sedekah was opened by a speech in Malay by Batavia’s assistant resident, followed again by the above-mentioned prayer. Food was served to around 2,000 people; while the programme also involved the organizers handing out coins to ‘native and Chinese children and the blind and handicapped’.Footnote 51 With its wide-ranging programme, the sedekah amounted to a festival for Batavia’s Muslim population. Its location near the old town now abandoned by Europeans was also laden with symbolism, with a Dutch reporter directly reminding readers that this was the very site where their ancestors had once landed to conquer the town of Jayakarta, now turned into a scene of celebration where their ‘brown brothers’ congregated to praise their Dutch monarch.Footnote 52

Conclusion: reconsidering empire through its ceremonial order

A spatial analysis of Batavia’s ceremonial order, tracing its spread from the central core of Weltevreden to an ever-wider range of neighbourhoods over the second half of the nineteenth century, shows the colonial capital finding ways to come to terms with its own internal diversity. From the top down, the difference may not have seemed great – as ever, committees were set up, programmes drawn up, speeches held – but the view from the neighbourhood reveals a drastic change in how inhabitants related to the colonial city and experienced it in their everyday environments. Whereas before, the city’s Asian – whether indigenous, Chinese or Arab – inhabitants had to make the unfamiliar trip to Weltevreden to even take part in official ceremonies, by 1898 the celebrations came to them. Residents could join in from their local mosques and marketplaces throughout the city, and were inevitably surrounded by the hubbub even if they did not much care for it. The neighbourhood had come alive as a unit of colonial urbanity: not merely as an administrative subdivision or a bureaucratic fiction, but as a stage where the city’s internal relations and dynamics unfolded in public.

In terms of demographics, colonial ceremonial came to embrace a much wider notion of who its people were and how they should be represented: from the largely overlooked sideshow of 1869’s sports day ‘for the natives’, by 1898 the programme had come to incorporate a wide range of component events catering to both specific communities and to the Asian population as a whole. In 1869, the main concern of the organizers had been the possibility and prevention of rioting, which three decades later had turned into a more positive plan of action to include the city’s many communities in the events. Naturally, such demographic broadening of the scope needed to be accompanied by a spatial rethinking: quite simply, the vast majority of the city’s population, and almost all of the non-European inhabitants, lived outside the boundaries of Weltevreden; nor were the doors of its many elite clubs and theatres exactly open to the people at large. Whereas 1869 had been about centring Batavia’s colonial public around the Koningsplein, 1898 was about decentring and redistributing it while simultaneously trying to maintain overall control of the narrative.

Yet, it was obvious that this new, outwardly more inclusive ceremonial order remained a fatally compromised and fragile construct. Throughout, it reproduced a two-tier system where Europeans had their own events and processions, their own music and their own buildings to sit in. Newspaper reports were full of praise for the lively excitement and loyalty of the empire’s subjects, crediting unspecified matriarchal traditions in the archipelago for making the people especially inclined to support the young queen. But it is difficult to see how any contradicting sentiments could have been raised in public. Moreover, a personalized honouring of the monarch fused into a wider celebration of empire and imperial conquest, as most strikingly exemplified in the unveiling of a monument for the conquest of Aceh in the newly named Wilhelmina Park. It was a new way towards an old goal; an acknowledgment that the empire relied for its continuation on a vast and diverse population that had to be included not just in everyday life as labourers, soldiers and merchants but also in pleasure as co-revellers – indeed, as neighbours.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Michael Yeo (Nanyang Technological University) for the opportunity to workshop an earlier version of this paper at the Southeast Asian Studies Seminar at the NTU.

Funding statement

Work on this article was partly funded by a postdoctoral grant from the Eino Jutikkala Fund of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. Open Access funding was provided by Freie Universität Berlin.