Introduction

A common feature of parliamentary democracies is the ability of the sitting government to trigger anticipatory elections. Opportunistic snap elections, defined as electoral competitions occasioned by incumbent prerogative for strategic gain (Balke, Reference Balke1990; Smith, Reference Smith2003), are not a rare occurrence but a ‘significant feature of parliamentary government’ (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018, p. 1184). Analysing parliamentary elections in Europe between 1945 and 2013, Schleiter and Tavits (Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016) find that one in seven post-war elections have been opportunistic. In the United Kingdom alone the two most recent elections – those of June 2017 and December 2019 – were both incumbent-triggered early summons to the polls. Additional cases can be found across parliamentary democracies such as elections in Australia (2010), Canada (2021), New Zealand (2002), and Spain (2019), to name just some illustrative examples, demonstrating the commonplace and legitimate nature of these snap electoral contests.

In this paper, I argue and empirically demonstrate that snap elections have a causal impact on political trust. Leveraging a quasi-experimental setting presented in the United Kingdom in 2017, I provide robust evidence that individuals who are exogenously exposed to incumbent-triggered early elections become significantly more trusting of the government. In April 2017, Theresa May, the incumbent Prime Minister and leader of the UK Conservative Party made the unexpected decision to call early elections. May's gamble proved to be a failure: despite the Conservative's strong polling position, early summons did not provide the party with electoral dividends and actually cost the party their legislative majority. Despite this electoral penalty, the findings of this quasi-experimental research design demonstrate that calling early elections did engender, at least in the short term, an increase in political trust in the government. Theoretically, I posit that these trust-inducing effects, whilst demonstrated to be sensitive to partisan-like moderation, are likely the result of citizens interpreting being given the opportunity to endorse or reject the incumbent's political mandate as a desirable provision of a well-functioning and responsive democracy.

Given the concern highlighted in the literature regarding the apparent widespread and systemic decline in political trust (Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000) and political support more broadly (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Williams2020)Footnote 1, one implication of these findings is that incumbent opportunism in the form of snap elections, whilst taken for strategic gain, may in fact aid in alleviating political discontent – at least in the short term. When the electoral calendar is distorted and citizens are called to the polls to express their (dis)content with the incumbent, the effect is, on average, remedial to political trust.

State of the art

The extant literature on the political consequences of snap elections is still rather limited. Most of the empirical analysis available, in addition to describing the constitutional variation in the application of these mechanisms (Schleiter & Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009), focuses on the effects of opportunistic action on aggregate (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016) and individual-level (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte and Nadeau2004) voting for the incumbent or on electoral participation (Daoust & Péloquin-Skulski, Reference Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski2021). Relying on national vote share enjoyed by incumbents, Schleiter and Tavits (Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016) demonstrate that leveraging the advantageous access to knowledge of the political and economic situation afforded by being in power (Smith, Reference Smith2003) allows incumbents to benefit from net electoral gains. Even in those scenarios where calling an early election may result in an increase in resentment,Footnote 2 the evidence suggests that only a very small minority of voters punish incumbents for calling them to the polls ahead of time (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte and Nadeau2004).

Beyond a focus on electoral choice, Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski (Reference Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski2021) consider if early elections can influence turnout. Theorising that early elections can increase costs for citizens and have the potential to induce feelings of voter fatigue (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), the authors use individual-level data from provincial elections in Canada to test their theory. In contrast to the net positive effects of snap elections on incumbency (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016), Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski (Reference Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski2021) find negative effects on incumbent support but no evidence of snap elections depressing turnout.

Whilst yet unconsidered in the empirical literature assessing the political consequences of incumbent opportunism, I make the theoretical argument that triggering snap elections is likely to have a causal effect on political trust.

Snap elections and political trust: Theoretical expectations

Political trust is the belief that political actors are trustworthy (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002) and the latter entails believing political actors act and respond in accordance with the expectations of the public (Warren, Reference Warren1999) even when unsupervised (Easton, Reference Easton1975). There are theoretically sound arguments to expect trust to be both positively and negatively affected by snap elections, presenting us with an empirical puzzle. The rationale for a positive effect rests on the assumption that citizens in democratic polities desire and take advantage of the opportunity to communicate their political preferences. My argument here is that in triggering early elections, incumbents signal the provision of a new and additional opportunity for citizens to express their political voice which democratic theory views as desirable.Footnote 3 The opportunity to ‘have their say’ is beneficial for both those with positive and negative dispositions with the incumbent: those positively predisposed are granted the opportunity to signal their endorsement of the government's mandate, whilst those who are negatively predisposed are granted the means to ‘throw the rascals out’. Moreover if, as was communicated in the case of the United Kingdom's snap election in 2017 (Margulies, Reference Margulies2019) and also evidenced from the 2021 announcement of a snap election by Canadian Liberal party Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau,Footnote 4 the incumbent relies on populist-like rhetoric of wishing to hear the ‘will of the people’ or strives to give the people ‘a voice’, citizens are also likely to be inclined to interpret seeking an electoral mandate as democratically desirable and exemplary of political trustworthiness (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002; Warren, Reference Warren1999). A rational interpretation for citizens when openly invited to endorse or reject an incumbent's mandate is that the incumbent is acting in accordance with democratic expectations and, as Warren (Reference Warren1999) argues, political actors are trusted if their actions comply with the normative expectations associated with their democratic role. In a reverse scenario whereby an incumbent opted to postpone or delay an electoral contest, a rational interpretation of such actions would view them as being undemocratic and likely indicative of untrustworthiness. As a result, my first hypothesis is that citizens will be more inclined to trust a government that provides the electorate the means of exercising their vote:

H1a: Calling snap elections will increase political trust.

An alternative expectation, however, is that the opportunistic behaviour of political incumbents may induce a fall in political trust in the government. Anticipatory elections are not called at random. In those circumstances where the incumbent opts – of their own free willFootnote 5 – to bring elections forward, then it is likely the case that doing so is the outcome of strategic considerations that are assumed to provide the incumbent with an expedient electoral advantage over their competitors (Balke, Reference Balke1990; Smith, Reference Smith2003). The strategic incentives that drive incumbents to advance the timing of elections are often extensively reported on in the media and, as a result, potential voters are likely exposed to political punditry that highlights the advantages enjoyed by the incumbent.Footnote 6 This information is likely to update citizens’ evaluations regarding the procedural fairness of the electoral process (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018) and incumbent abuse of power. Concerns about procedural fairness are strongly correlated with political trust (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2001; Grimes, Reference Grimes2006) and, therefore, in a scenario where concerns over procedural fairness may be prone to be heightened, we might reasonably expect citizens to become less trusting of the government as a result.

Additionally, snap elections may serve as an indicator of government failure. In the case of the 2017 snap elections, May's decision was in many respects a response to her inability to make advances on Brexit in the House of Commons (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018). The most recent snap elections in Spain in 2019 were, in part, the result of the incumbent socialist-led government being unable to legislate on the state budget. If snap elections come about because sitting governments seek an increased majority in order to remedy their inability to govern effectively, calling early elections may signal government failure bringing about more negative political evaluations and feelings of political trust.

H1b: Calling snap elections will reduce political trust.

Given the rich literature in motivated reasoning that highlights the role of partisanship and ideological attachment in engendering a partisan lens or ‘perceptual screen’ through which individuals filter and process political information (Bartels, Reference Bartels2002; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992) which can also influence political trust (Citrin, Reference Citrin1974), I theorise that responses to incumbent-triggered snap elections will also be subjected to partisan rationality. I hypothesise that those ideologically disposedFootnote 7 to support the government will be more likely to react positively, whilst individuals with ideologically juxtaposed predispositions will be more prone to react negatively.

H2a: The effect of snap elections on political trust will be moderated by ideological congruence with the incumbent.

In the specific case of the United Kingdom, research highlights the emergence of salient Brexit-based political identities in addition to party identities following the 2016 Brexit referendum (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). Importantly, these Brexit-based identities – whether one identifies as a pro-EU ‘Remainer’– or an anti-EU ‘Leaver’ – have not only become more prevalent than conventional partisanship, but affective attachment to these identities is also stronger than partisan identification (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2020). In a rigorous test of the ability of Brexit-based identities to operate as a partisan-like perceptual screen, Sorace and Hobolt (Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021) present both observational and experimental evidence to demonstrate that Brexit identities have replaced traditional partisan loyalties as the primary emotional political attachment that exhibits a moderating effect on the reception of processing of political and economic information. I, therefore, expect EU-based preferences (serving as proxies for Brexit identities) to moderate the effect of treatment on political trust. This is particularly probable given the political context at the time where concerns over the government's ability to legislate for Brexit were a claimed motivation for the triggering of elections.Footnote 8

H2b: The effect of calling the 2017 general election in the United Kingdom on political trust will be moderated by Leaver vs. Remainer Brexit identities.

Case study

Empirically, I test these opposing theoretical expectations via an original quasi-experimental test from a case study involving the United Kingdom's 2017 snap elections. Whilst the quasi-experimental test from a single case provides strong internal validity for the theory in that, as discussed below, it can facilitate causal identification, single cases may have limited external validity. I begin the discussion of the methodological approach by considering the utility, and potential limitations in external validity, of the concrete case of the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom's constitutional arrangement facilitates the government with the ability to trigger snap elections at will and, as detailed by Schleiter and Tavits (Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016), the availability and application of this incumbent prerogative are not uncommon in parliamentary democracies. Since 2011, the incumbent prerogative in the United Kingdom has been tempered by the introduction of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, which demands a two-thirds majority of the lower chamber for parliament to be dissolved and snap elections to take place. Early elections are common in the United Kingdom. Half of UK governments end with pre-emptive summons to the polls and similar rates of early elections are also observed in other European democracies such as Denmark and Spain (Schleiter & Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009). The United Kingdom is, therefore, by no means an outlier in terms of the constitutional provision or relative frequency of snap elections when viewed via a comparative lens with European peers.

Some features of Theresa May's shock announcement in April 2017 are, however, more unique and might signal variation from ‘typical’ snap elections. First, while in some cases the ‘shock’ factor of early elections is diluted by pre-emptive leaks or speculation among pundits and the political rumour mill, May's announcement – as discussed below – was a genuine and unanticipated shock. Second, the 2017 snap elections were presented, at least when May launched the campaign starting gun with her shock announcement, as a mandate-seeking election aimed at resolving the contentious issue of Brexit. The Conservative Party campaign, arguably to their detriment, went to great lengths to focus on a desire to form a ‘strong and stable’ government that would strengthen the United Kingdom's hand in Brexit negotiations with the EU (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018). If snap elections come about solely because the incumbent is seeking to consolidate their longevity by leveraging electoral timings to their advantage, the 2017 United Kingdom elections are somewhat distinct as an inability to effectively legislate (in this case on Brexit) also played a role. As one headline from the Brexit-supporting Daily Mail read – ‘Crush the Saboteurs’ (online appendix Figures A8–A11) – it is clear that part of May's rationale was to remedy the Brexit-related drawbacks the government had been suffering in the Commons. In a political climate where the recent referendum had politicised divisions between the people and the establishment (Russell, Reference Russell2021), May's explicit call to ‘let the people decide’ might have been acutely more resonating than in other contexts. Moreover, and given these contentious Brexit issues, one might expect that levels of political trust in the United Kingdom may deviate from the average observed among the country's European contemporaries. Mapping the proportion of citizens who report they trust the government in the United Kingdom in comparison to other countries (online appendix Figure A1), evinces that the United Kingdom is a useful case for comparison as it is very much a median country when it comes to aggregate level trust.

Other features of the UK case also make it a good test. Of note is that there were no significant policy shifts that coincided with the shock election announcement. Warren (Reference Warren1999) argues that citizens’ trust in the government reflects both the government's compliance and fulfilment of the normative functions expected of it, as well as citizens’ political (or partisan) approval of the policy output that the government provides. In the case of the United Kingdom's experimental setting, we have (exogenous) exposure to variation in the fulfilment of democratic functions without variation in government policy. In other words, whilst Theresa May's Conservative government unexpectedly intervened in the electoral calendar – providing citizens with the right to exercise their democratic ‘voice’ at the ballot box and shape the partisan makeup of Westminster – this provision did not coincide with any policy change. We can assume, therefore, that any change in trust associated with treatment allocation is not a function of policy shifts, but the government's provision of opportunities for democratic participation.

Empirical approach

The quasi-experimental identification strategy relies on the ‘unexpected event during survey fieldwork’ approach detailed by Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). The UK fieldwork for Eurobarometer 87.2Footnote 9 took place between 15 April and 24 April 2017. Then Prime Minister Theresa May made the shock announcement of early elections on 18 April. Because the UK's Fixed Term Parliament Act (2011) constrains the ability of the prime minster to call elections without the support of Westminster, a vote calling for early elections took place the following day which required a qualified majority of two-thirds of the Commons in order to pass. The mainstream opposition voted in favour of early elections along with the Conservatives. Labour support for early elections can be explained by the fact that opposition parties present themselves as the ‘government in waiting’ and, as a result, opposing early elections would be a signal that the opposition endorsed the Conservative government over their own governing potential.

The unexpected triggering of elections provides us with naturally occurring random assignment to one of two treatment conditions: (i) control (interviewed immediately before snap elections called) and (ii) treatment (interviewed immediately after snap elections called). Of note is that the snap elections were not anticipated by political pundits and media commentators. One CNN headline, for example, read ‘British Prime Minister Theresa May has stunned the UK political world by calling for an early general election[…]’ and another from BBC News read ‘How press reacted to Theresa May's shock announcement’.Footnote 10 Individuals in treatment were interviewed in a political climate that they could not have anticipated before the political news broke and varied significantly, in terms of treatment exposure, from those in control: the treatment group was interviewed after suddenly being offered an opportunity to voice their political preferences at the ballot box in advance of the organic electoral calendar, whereas those in control were not.

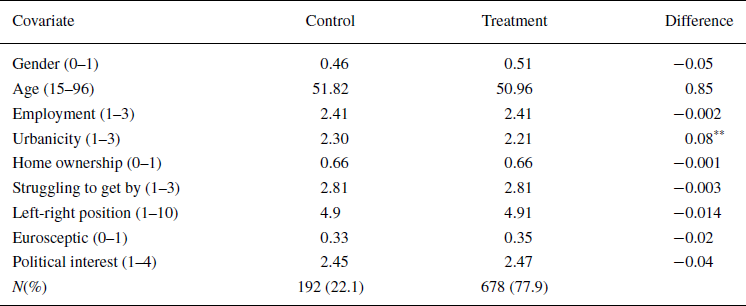

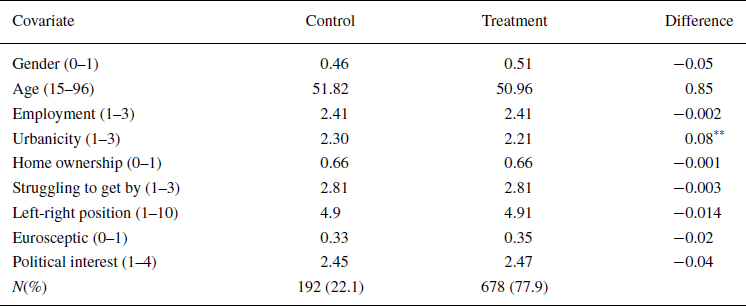

In addition to facilitating a means of causally identifying the effects of snap elections on political trust via the as good as random exposure to the early election news, our quasi-experimental design has the additional advantage of providing high levels of ecological validity given that any exposure to the news of the government's announcement is naturally occurring rather than researcher imposed. One potential threat to the inferences made by this quasi-experimental design, however, is that the composition of samples assigned to the naturally occurring treatment groups may not be symmetrical due to some temporal imbalances in the sampling of respondents (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). In Table 1, I demonstrate that there are no significant differences between the individuals in each condition, with the exception of urbanicity.Footnote 11 Individuals assigned to the control and treatment groups are, therefore, largely symmetrical with the exception that the latter could be aware of the snap elections whereas the former could not.

Table 1. Balance across treatment conditions

Note: t-test (two-tailed).

** p< 0.05.

To assess the effects of the surprise announcement of snap elections in the United Kingdom, I estimate a linear model (Model 1) in which Yi is political trust, β 1Treatmenti is the average effect of treatment assignment – the intent-to-treat effect (ITT) – and γXi is a vector of individual covariates. The results report coefficients from ordinary least squares regression modelling (Hellevik, Reference Hellevik2009), but an alternative estimation using logistic regression is reported in online appendix (online Appendix Table A3) where the findings remain unchanged. Both unadjusted and co-variate adjusted ITTs are reported. Individual covariates included in the covariate-adjusted model include gender, age, employment status, urbanicity, left-right placement and regional fixed effects. Covariate operationalisation is reported in the online appendix.

Outcome measure

The primary outcome measure is political trust. Eurobarometer 87.2 records political trust in the government via a dichotomous indicator by asking respondents what they ‘tend to trust’ (1) or ‘tend not to trust’ (0) about the national government. Importantly, the dependent variable is an indicator of specific trust in the government as opposed to diffuse trust or satisfaction with the political system (Easton, Reference Easton1975). Unfortunately, alternative measures of political trust that are more diffuse, for example, trust in parliament or satisfaction with democracy, are not available in the data but the theoretical expectations posit that diffuse regime trust would also be influenced by snap elections. If, for example, facilitating voters with the means to communicate their political preferences is viewed as desirable, we would assume that doing so would also engender (more) positive evaluations regarding the proper functioning of democracy per se and not just the trustworthiness of the incumbent. In the robustness section, we do consider some trust-related placebo outcomes.

Treatment

Treatment, based on the naturally occurring random assignment, is operationalised as

Ti= 0 (control) if respondent i interviewed before 18 April

Ti= 1 (treatment) if respondent i interviewed on or after 18 April

May's announcement – treatment to news of early elections – took place in the afternoon on 18 April. Given the strict threshold, I place on treatment assignment, that is, those individuals interviewed on or after the 18, there are potentially non-complying respondents assigned to treatment who were actually interviewed in the control period in the AM of the 18 before the news was announced. Replicating the analysis to exclude individual respondents interviewed on 18 April (N = 130), demonstrates that the potential for non-compliers at time t 0 does not bias our results as demonstrated in online appendix Figure A3.

Moderators

My hypotheses include two moderators: ideological attachment (H2a) and Brexit identities (H2b). In the absence of vote recall or expressed affinity for a political party, I rely on individual spatial identification on the left-right (1–10) axis as a proxy measurement for congruence with the incumbent. In addition to this 10-point linear measure, I also test for moderation via a dichotomous indication of ideology: left wing (ideology lower than 5) and non-left wing (ideology greater than or equal to 5). To stratify the sample based on Brexit identities, I include an indicator of those who hold negative or non-negative views of the EU. I take individuals who exhibit Eurosceptic preferences regarding the EU to be likely Leave voters (1) and those who hold other preferences to be likely Remain voters (0). Importantly, assessing the balance in moderator outcomes between individuals who identify on the left-right axis as well as individuals’ preferences on EU integration, demonstrates that moderator values are symmetrical across the two treatment conditions (Table 1). As a result, the potential for introducing post-treatment bias (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018) by considering conditional ITT effects across moderator values is limited.

Analysis

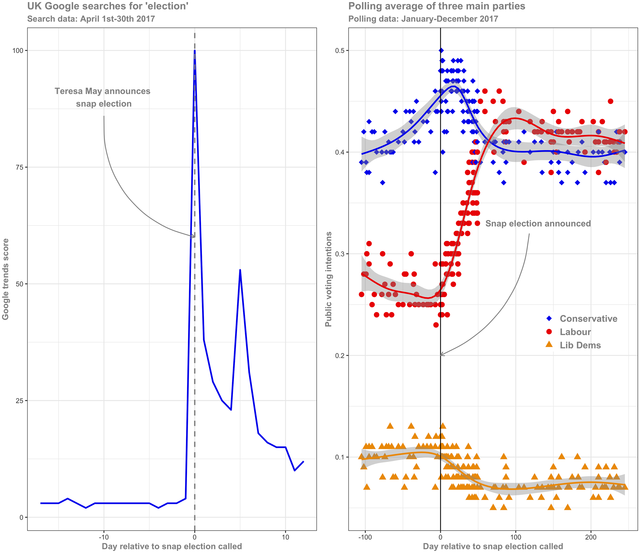

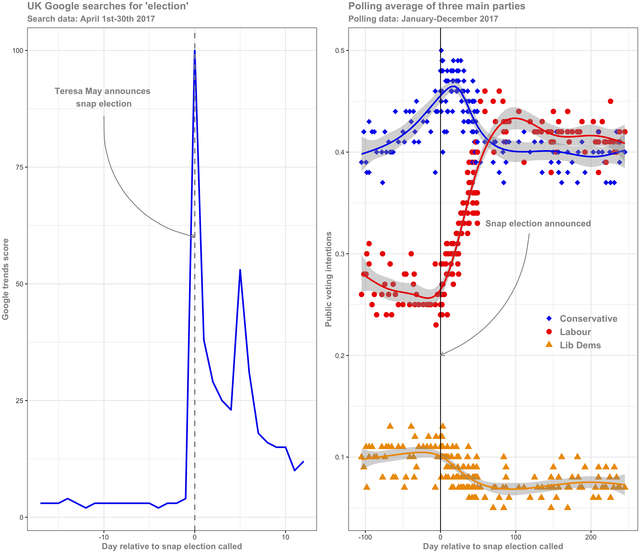

Before presenting the results, I seek to demonstrate both the exogeneity and saliency of the shock announcement. Figure 1 evinces that the early election announcement coincided with a substantive spike in online searches for ‘election’ in the United Kingdom (left-hand panel). Whilst public interest in elections was low in the lead up to 18 April (treatment date), the government's sudden triggering of snap elections can be seen to cause a significant increase and discontinuity from the pre-treatment trends.

Figure 1. Trends in interest in elections and polling performance over the treatment period. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The date of the government's intervention in the electoral calendar also correlates with a substantive change in the polling performance of the mainstream opposition UK Labour party (right-hand panel) who were polling far behind the governing Conservatives during the pre-treatment period. The poor performance of Labour in the time period prior to the snap election news is of note as it is indicative of the opportunistic nature of the government's decision. Opportunistic elections are triggered when the incumbent expects to bank increased electoral revenues (Balke, Reference Balke1990; Smith, Reference Smith2003; Schleiter & Tavits, 2016) because of a favorable political and/or economic situation (Smith, Reference Smith2003; Strøm & Swindle, Reference Strøm and Swindle2002). The advantageous polling position enjoyed by May's party before the premiere's shock announcement – as demonstrated in Figure 1 – is congruent with interpretations of the snap election as strategically opportunistic (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018). The immediate shift in the performance of the Labour party in British polling at the treatment threshold is also consistent with the ultimate electoral costs of the snap election for the Conservatives: the party suffered an electoral penalty to their parliamentary majority rather than enjoying any electoral gains.

Main effects

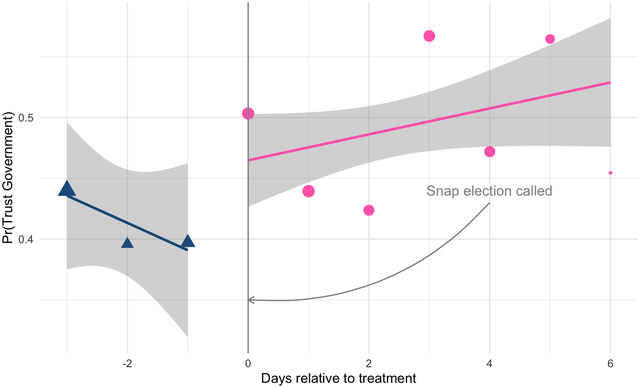

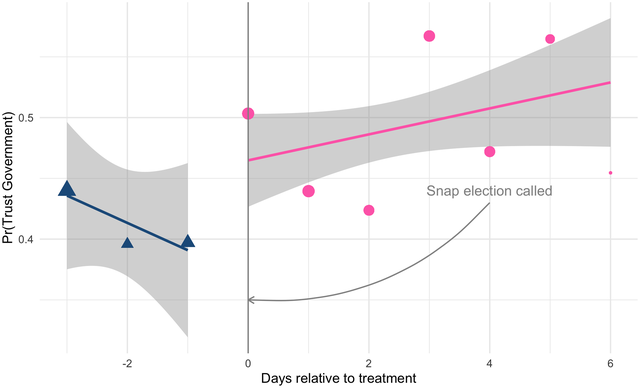

I begin by demonstrating the variation in the pre- and post-treatment trends in political trust in the government over the entire window of the UK Eurobarometer 87.2 fieldwork. As visualised in Figure 2, levels of trust in the government were largely stable during the pre-treatment period. In the immediate post-treatment period, we observe a sizeable discontinuity in trust that remains largely stable over the days for which data are available. Any divergence in trust over the treatment allocation threshold is not, therefore, a product of temporal trends.

Figure 2. Pre- and post-treatment trends in Government Trust. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

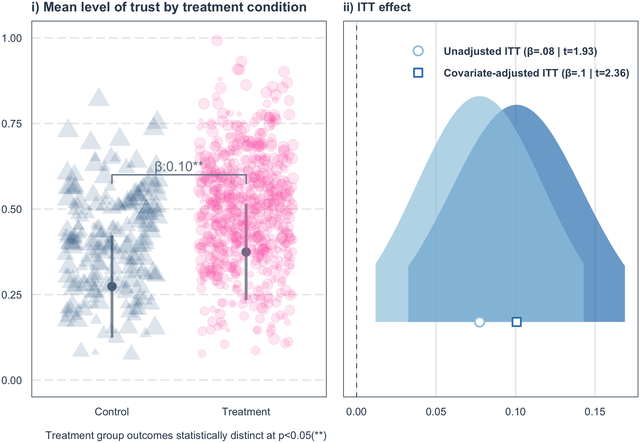

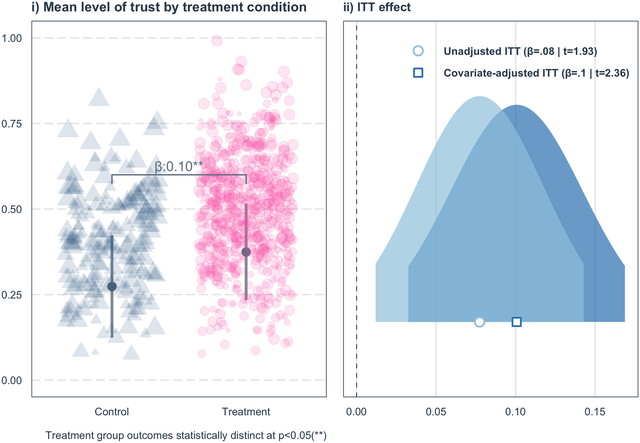

In Figure 3, I report the mean level of trust in the government among those interviewed immediately before Theresa May's surprise announcement of elections (control) and those interviewed on or following the day of the announcement (treatment). The full regression output is reported in online appendix Table A2 for consultation. The covariate-adjusted effect of treatment allocation on trusting the government is sizeable (β = 0.10) and significant (p = 0.015). In real terms, the shock announcement of early elections results in a 10 percentage-point increase in the probability of trusting the government. Congruent with the theoretical argument that allowing the people to ‘have their say’ is conducive to increasing specific (government) political support, providing voters with the advance opportunity to reward or punish the incumbent at the ballot box leads to increases in political trust as posited in H1a. In direct contention with the expectations of H1b, voters do not become less trusting of the government when opportunistic elections are triggered.

Figure 3. Effect of treatment allocation on Pr(Trust in Government). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

These results are not necessarily surprising. Despite demonstrating that opportunistic elections may raise concerns about issues of legitimacy and fairness (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018), the literature also points towards opportunistic elections providing incumbents with net gains at the ballot box (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016) – although penalties have also been observed (Daoust & Péloquin-Skulski, Reference Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski2021). If trust in the government were to collapse in response to incumbent opportunism, we would expect reduced trust in the government to correlate with reduced electoral support for the incumbent also. This is not the case. As evinced in both Figures 1 and 2, May's announcement simultaneously led to a boost in electoral support for the opposition as well as an uptick in political trust in the government.

As highlighted in the discussion of the case selection, given treatment serves as an information signal regarding the government's provision of opportunities for democratic participation without variation in government policy, we can assume that the increase in trust associated with treatment allocation is a result of the government fulfilling its normative democratic functions (Warren, Reference Warren1999).

Moderation effects: Ideological congruence and Brexit identities

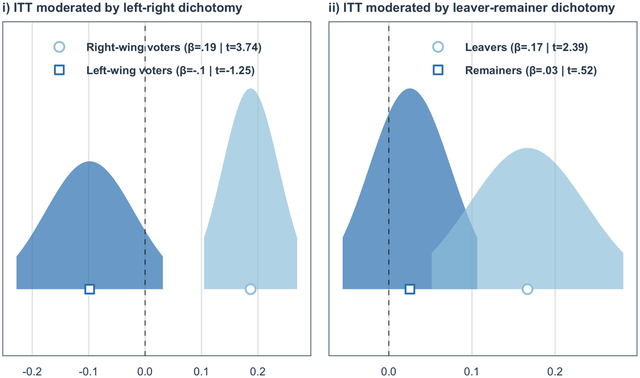

I now turn to assess the moderating effect of ideological and Brexit-based issue positions. Whilst, on average, citizens become more trusting of the government in response to the announcement of snap elections, I expect Brexit attachments (Sorace & Hobolt, Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021) and ideological (in)congruence (Bartels, Reference Bartels2002; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992) to result in asymmetric responses among citizens. H2a assumes right-leaning voters are congruent with the incumbent right-wing Conservative party and that left-wing voters are not. In the case of Brexit-based identities (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2020) which, as demonstrated by Sorace and Hobolt (Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021), have been empirically shown to moderate political information in a partisan-like lens, I assess the potential moderating role of Euroscepticism. Given that in 2017, the Conservative party became the new partisan home of Leave voters (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018), H2b posits that likely Leavers respond positively to the government's announcement of new elections.

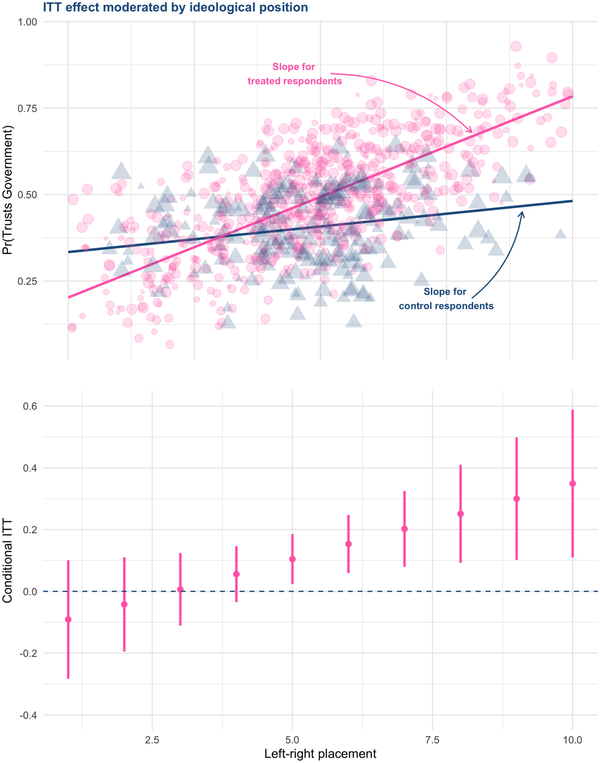

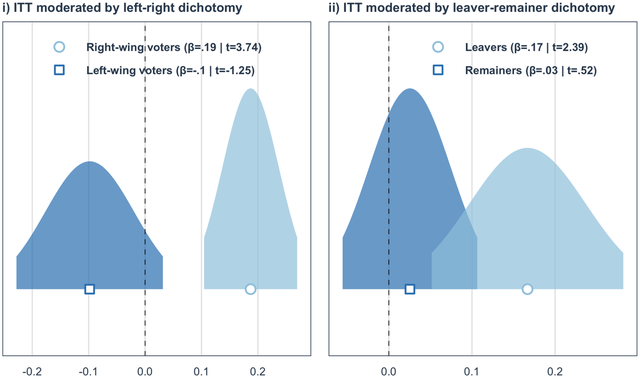

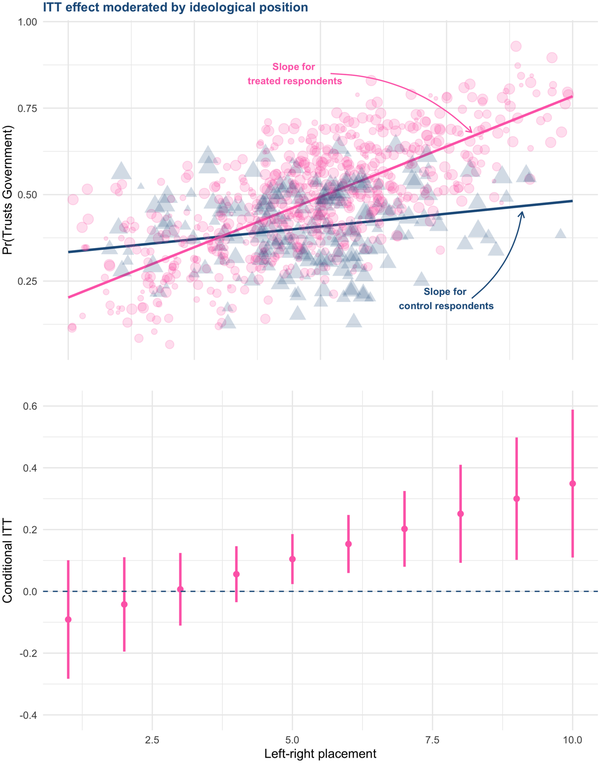

In Figures 4 and 5, I report the conditional effect of allocation to treatment across three different approaches of modelling ideological and Brexit-based attachments. In the upper panel of Figure 4, I report the modelled levels of political trust in the government by treatment condition for different levels of ideological placement. The bottom panel reports the conditional ITT effects for observed values of the 10-point left-right moderator.

Figure 4. Moderating effects (i). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 5. Moderating effects (ii). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The results demonstrate that the elevating effects of early elections on political support are unique to those individuals who identify on the right, that is, those individuals we would consider to share the ideological sympathies most congruent with the incumbent Conservative party. Considering first, the linear measure of ideology (Figure 4): levels of political trust between treatment and control among individuals who identify with a spatial position less than 5 are indistinguishable from one another. In other words, we observe null effects among those who identify on the left. For those individuals who fall in the political centre – where a plurality of respondents fall (38.62% of respondents spatially place themselves on the median value: 5) – the average effect of treatment assignment is equal to 10.5 percentage points (p = 0.012) and this effect increases substantively among those even further to the right. Among those on the ideological extreme of the right-wing space, the conditional ITT is 35 percentage points (p = 0.004). In a more simplistic interaction between a dichotomous indication of left and non-left leaning respondents, we observe a sizeable and significant positive ITT effect in the case of the latter equal to 18 percentage points (p < 0.001) but a negative (yet insignificant) effect in the case of the former (Figure 5).

Turning towards our Brexit-based moderation model, significant conditional effects are observed (Figure 5, right-hand panel). Likely Leavers naturally assigned to the treatment condition are significantly more trusting of the government than likely Leavers in control (β = 0.18 |p = 0.005). In the case of likely Remain voters, the average effect of treatment assignment is both comparatively small and also statistically indistinguishable from zero (β = 0.04 |p = 0.426). As Sorace and Hobolt (Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021) demonstrate in the case of economic evaluations, the results evince that Brexit-based orientations exhibit a partisanship-like motivated reasoning effect when it comes to forming evaluations of trust in the government in the face of incumbent opportunism.

An alternative interpretation of these interaction effects is that the survey instrument seeking to measure political trust is also capturing potential voting intentions for the incumbent. In other words, likely Leave voters are becoming more trusting of the government because they are more inclined to support the Conservatives (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018). Should that be the case, however, we would also expect negative effects to be observed amongst Remainers who, in opposition to Brexit, are less inclined to support the now explicitly pro-Brexit May-led Conservative government. We do not observe negative effects. Although the estimated effect of treatment allocation among Remainers is indistinguishable from zero, it is positively signed and, therefore, in the opposite direction of what we would expect were trust in the government purely indicative of government support.

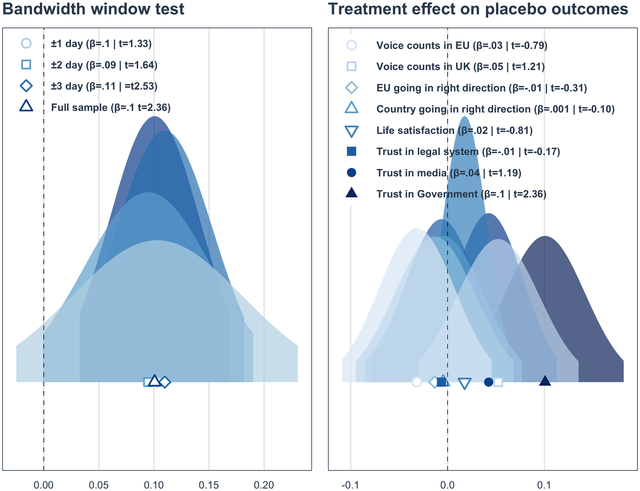

Sensitivity tests

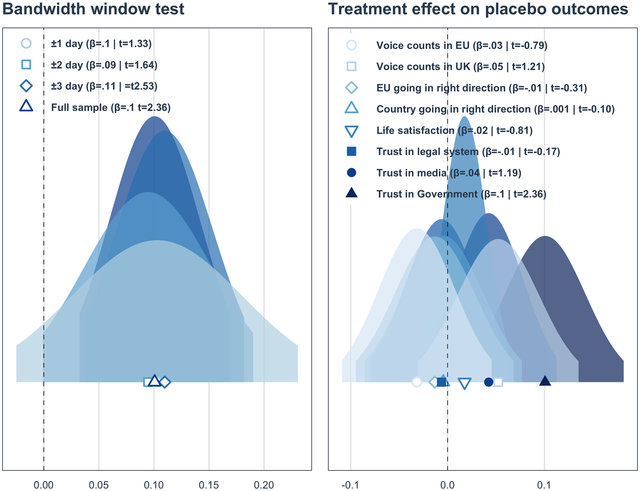

Applying a category of different sensitivity and robustness tests demonstrates the rigour of the main findings and supports the interpretation of the observed results. First, and as recommended by Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020), I assess the sensitivity of the findings across different bandwidths on either end of the treatment threshold. Comparing individuals interviewed within only a single day window (essentially a very strict local randomization test) demonstrates that the trust-inducing effect of treatment allocation is symmetrical to that observed among the full sample (Figure 6 left-hand panel). Whist the point estimates across different bandwidths are very stable, the results of the most constrained models are statistically indistinguishable from zero. These insignificant results are, however, a function of the restricted N – and consequent limited statistical power – facilitated by more conservative bandwidths.Footnote 12

Figure 6. Bandwidth and placebo tests. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To test that the primary results are not the result of spurious differences between the levels of adjacent measures of trust and political satisfaction, we also model the effect of treatment assignment on a battery of trust-related placebo measures. As visualised in the right-hand panel of Figure 6, treatment allocation does not exhibit any effects of significance or substance on (i) trust in the media, (ii) trust in the legal system, (iii) life satisfaction, (iv) the belief that the country is going in the right direction, (v) nor the belief that the EU is going in the right direction. I interpret the null effects observed on these placebo items as providing support for the theorised mechanism posited in H1a: citizens become, on, more inclined to trust the government when the government facilitates the means of the electorate to endorse or reject the incumbents’ political mandate at the ballot box.

Given the theoretical argument I present regarding increased choice, we might expect treatment to increase political efficacy (‘my voice counts’ or the sense that the country is headed in the ‘right direction’. The results reported in Figure 6 suggest that, on average, this is not the case. There are, however, significant moderation effects (see online appendix Figure A2). In line with the main effects on trust, right-wing individuals also become more inclined to believe that the country is headed in the right direction (β = 0.09 |p = 0.08) and believe that their voice matters (β = 0.08 |p = 0.14).

Additional sensitivity tests, including an analysis of the potential moderating effect of political interest (online appendix Figure A6) and permutation tests using randomly assigned placebo dates (online appendix Figure A5) are reported in the online appendix for consultation. I also provide multiverse analysis showing the robustness of our findings to alternative specifications (online appendix Figure A7).

Conclusions

The quasi-experiment exploited in this article provides a unique opportunity to assess the causal effect of early elections on political trust in the government. Elections are a core means via which citizens are afforded a window of opportunity to express their political preferences and shape the ideological and partisan colour of the government of the day. These windows of opportunity come, however, normally at regulated intervals. It is therefore difficult to assess how the provision of elections affects political trust as the timing of elections is normally endogenously established. Leveraging the setting provided by the (unexpected) announcement of opportunistic snap elections in the United Kingdom in 2017, I am able to test how snap elections influence political trust.

Theoretically, I hypothesise alternative reactions to opportunistic elections. One thesis posits that facilitating the electorate with the means of endorsing or rejecting the incumbent, a core function of representative democracy, is viewed by citizens as normatively desirable. Therefore, one might expect being given the opportunity to throw (or keep) ‘the rascals’ out (in) to increase political trust. A theoretically juxtaposed argument assumes that citizens are likely attuned to the strategic opportunism that motivates the incumbent to call anticipatory elections and, responding to concerns of procedural fairness and/or abuse of executive power (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018), respond negatively by becoming less trusting.

The quasi-experimental research design finds support for the anterior trust-inducing thesis as opposed to latter. The shock announcement of snap elections in the United Kingdom, widely reported to be opportunistically motivated (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018), caused a 10 percentage point increase in trust in the government. These positive effects are, however, not exhibited homogeneously across the population. Respondents identifying on the right of the left-right axis became significantly more trusting of the government, whilst those identifying on the left demonstrate no changes of substance or significance when exposed to treatment. In other words, those individuals who hold an ideological position that we can assume to be more congruent with the right-leaning (incumbent) Conservative party respond positively whilst those who we would consider as ideologically detached from the Conservatives do not update their levels of trust when opportunistic snap elections are announced. Eurosceptic individuals – those most likely to have voted Leave in 2016 and who flocked to the incumbent Conservative party in 2017 (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018) – became significantly more trusting of the government than their non-Eurosceptic counterparts.

Additional research would do well to replicate a similar partisan-like moderation test with a left-wing incumbent to assess if the moderating effects of ideological congruence are also conditioned by the ideological colour of the incumbent at the time. The scope conditions of my theoretical argument assume that symmetrical patterns would be observed when a left-wing government is in power. This is, however, an empirical limitation of the single case study under assessment and, given the penchant for those on the left to place a premium on values related to ‘fairness’ (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek and Haidt2012; Haidt, Reference Haidt2007), I cannot preclude that the trust premium would replicate when an incumbent of their own ideological colour calls early elections.

The overall findings of this quasi-experiment speak to the effects of opportunistic elections which, whilst not uncommon (Schleiter & Tavits, Reference Schleiter and Tavits2016), the political consequences of which we still know very little. The evidence I present here, much in line with the existing work that highlights the, on average, net positive effect of opportunistic interventions in the electoral calendar on incumbent electoral success, demonstrates that there is no penalty on political trust even in those cases where the decision results in electorally inimical outcomes. On average, calling snap elections has a trust-inducing effect which, I argue, is likely the product of citizens experiencing the chance to communicate their (dis)content with the government as desirable.

As highlighted above, the single quasi-experimental design analysed here presents a trade-off between internal and external validity that has implications when it comes to theorising under what conditions we might expect similar trust-inducing effects to be observed. Whilst the as good as random modelling approach provides a strong identification strategy, focusing on the experimental setting in the United Kingdom means I cannot test if the results are conditioned by particularities unique to the British case. Although, and as highlighted earlier, the constitutional provision and frequency of snap elections are not by any means dissimilar from comparable European democracies (Schleiter & Morgan-Jones, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009). Future replications that can leverage a research design that coalesces causal identification with cross-country comparison would be welcome contributions that can empirically test the scope conditions of the trust-inducing effect of snap elections.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to members of the TrustGov team at the University of Southampton, in particular, Viktor Valgarðsson and Will Jennings, for the critical feedback on earlier iterations of the paper. Earlier drafts also received helpful comments from José Rama and Jean-François Daoust. I am indebted to the four anonymous reviewers and the handling editor for their recommendations.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Descriptive summary statistics

Figure A1: Mean level trust measures in Eurobarometer 87.2

Table A2: OLS regression models

Table A3: Logistic regression models

Figure A2: Conditional test of mechanisms by ideology

Figure A3: ITT effect sensitivity to day 0 observations

Figure A4: rdlocrand window sensitively test

Figure A5: Randomisation inference via permutation

Figure A6: (Non-)moderating role of political interest

Figure A7: Multiverse specification curve

Figure A8: Front page – The Guardian (19th April 2017)

Figure A9: Front page – The Telegraph (19th April 2017)

Figure A10: Front page – The Daily Mail (19th April 2017)

Figure A11: Front page – The Independent (19th April 2017)

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed on the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SFUD8I