Rebellion and unrest have long been central subjects of inquiry for social scientists and historians. Social conflict reflects underlying discontent as well as competition over power disparities, contested values, perceptions of fairness, and expectations for the future. Because of its critical role in social transformation and long-term development (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979; Thompson Reference Thompson1964; Tilly Reference Tilly1986), scholars have examined how conflict shapes phenomena as wide-ranging as state formation (Slater Reference Slater2010), political consciousness (Porchnev Reference Porchnev1963; Thompson Reference Thompson1971), regime durability (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2013), and identity and beliefs (Ladurie Reference Ladurie1966). Many early students of conflict focused on episodes of violence and unrest in early modern Europe, a period marked by rapid social, cultural, and economic change alongside the emergence of centralized states (Ladurie Reference Ladurie1966; Porchnev Reference Porchnev1963; Thompson Reference Thompson1971; Tilly Reference Tilly1986). Because of the historical importance and prominence of such disorder, as well as rapid improvements in data availability and processing, a branch of emerging scholarship has turned to reexamining rebellion and unrest in this era.Footnote 1

We contribute to this growing literature by focusing on eighteenth-century France in the run-up to the French Revolution. While the Revolution has played an outsized role in history and is one of the most studied political events of the past two centuries, the thousands of localized uprisings that erupted across the French territory in the preceding decades have received comparatively little attention. These rebellions often simmered and were periodically suppressed by state agents, yet they ultimately fed into the broader revolutionary upheaval. At the same time, the monarchy heavily invested in state-building throughout the eighteenth century (Burguière and Revel Reference Burguière and Revel1989). A central element of this effort was the expansion of the horse-post relay network, which nearly doubled in size over the period. These relays established attended lodging quarters and a well-prepared set of fresh horses for messengers carrying information for the royal administration where there had previously been no support. The horse post represented one of the primary means of consolidating the hierarchical French state’s informational capacity as it sought to rule and control a fragmented territory (Marchand Reference Marchand2006).

Did this intensive expansion of the state’s informational capacity through the horse-post relay network generate backlash among populations exposed to these state-building efforts? To investigate this question, we combine original data on the development of the horse-post relay network over the eighteenth century with a comprehensive database of rebellions in pre-Revolutionary France. Using a staggered difference-in-differences framework centered on parishes—the most granular territorial unit then—we show that the introduction of a new horse-post relay in a parish was associated with more local rebellions in subsequent decades. We attribute this finding mainly to the material consequences of state efforts at penetrating and ordering local society as it centralized and enhanced its informational capacity.

The increasingly present state that was behind and facilitated by new horse-post relays became a target of popular ire for its activities, such as heavy-handed efforts at forced conscription, tax enforcement, monopolization of the roads, and inflexible enforcement of royal acts and laws perceived as unfair (Aubert Reference Aubert2015; Nicolas Reference Nicolas2002). Accordingly, we find that horse-post relays were strongly associated with rebellions against agents with coercive powers to maintain and enforce order: the military, the police, and the judiciary. They were also associated with rebellions against various forms of taxation as well as rebellions by notables that had private interests along postal roads. Furthermore, while these relationships broadly prevail and encompass the lion’s share of rebellions, we also find a disproportionate response of rebellions to horse-post relays in places of pre-existing state fragmentation and territorial divisions. These findings demonstrate an increasingly powerful state that nonetheless struggled to control local activity across a heterogeneous territory as many of its efforts were contested.

Our empirical approach and additional data give us a unique opportunity to evaluate and challenge several alternative explanations—namely, the erosion of traditional social hierarchies, the role of war zones and war involvement, information and collective action possibly spurred by the contemporaneous letter-post system, changes in the recording of rebellions by police brigades (maréchaussée) charged with keeping order, and the contemporaneous transit infrastructure. These latter three alternatives are often challenging to dismiss in more commonly studied cases where communication and transportation networks are built together from scratch and can be widely used. In eighteenth-century France, however, the horse-post relay network was built atop existing transit routes and served as a state-monopolized communications network. Moreover, the development of police brigades and the letter-post system followed a different logic than the horse post.

Our findings have implications for the scholarly understanding of the co-evolution of states, order, and disorder, as well as for the vast corpus of work on the origins of the French Revolution. While greater state capacity may ultimately support political stability and order, the process of state-building itself can be disruptive to pre-existing social structures and contested, even for decades at a time. This process likely fueled the accumulation of grievances and repertoires of resistance that ultimately exploded during the Revolution.

THE LONG AND CONTESTED PROCESS OF STATE FORMATION

There is a broad, rich literature on state formation, including the emergence of states, state centralization and consolidation, and the exercise of power. This literature makes clear that building a strong state is a long, complex, and often contested process. As Elias (Reference Elias[1939] 1994) emphasizes, it has taken most states centuries to overcome powerful fragmented regional and religious elites that had private armies and taxation rights, and many states around the world still face fundamental weaknesses (Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017; Soifer Reference Soifer2015). In Europe, monarchies slowly absorbed feudal capacities as they centralized their administration and bureaucracy, a process that Elias (Reference Elias[1939] 1994) describes as not only coercive and political but also social, as regional consciousness declined and increasing state presence in society created “civilizing” norms of state control over the use of violence.

Weber (Reference Weber1968) prominently described the newly powerful states that ultimately resulted from this process as defined by a monopoly over the use of violence within their territory, which entails the legitimation of authority and a centralized hierarchy of administration that embodies and enforces a legal-rational domination of society. Subsequent seminal scholarship elaborated concepts, such as state capacity and autonomy (Evans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol Reference Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985) and underscored the importance of a strong state to establishing and maintaining social order (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979).Footnote 2

State formation in Europe advanced through both external pressures and internal incentives and innovations. Tilly (Reference Tilly1990) emphasizes how military and fiscal demands associated with regional competition and warfighting pressured early states to accelerate their efforts at centralization and extraction in order to build the capacity to wage war and defend their territory.Footnote 3 Eventually, state efforts to penetrate society and build capacity became fortified by institutional innovations that responded to disparate interests and in doing so, fostered greater compliance with extraction (Levi Reference Levi1989).

However, most states spent numerous decades and even centuries attempting to penetrate society and centralize control and administration. A core component of those efforts has been the expansion of transportation and communication routes to facilitate the penetration of the state’s reach into society and the administration of its territory. This is closely tied to what Mann (Reference Mann1984) termed infrastructural power—namely, the capacity of the central state to penetrate its territories and logistically implement its decisions. This implicates both the state’s material capabilities and its territoriality (Soifer Reference Soifer2008). As Mann (Reference Mann1984) underscores, infrastructural power can vary separately from the despotic power used to impose mandates over society. It can also be very uneven across the territory (Boone Reference Boone2003; Pierskalla, De Juan, and Montgomery Reference Pierskalla, De Juan and Montgomery2019).

Historically, states and empires built paths, stone roads, postal routes, ports, and canals to reach remote populations, transmit information and correspondence, and deploy military forces (Bulliet Reference Bulliet1990; Rogowski et al. Reference Rogowski, Gerring, Maguire and Cojocaru2022). Today, governments continue to build and improve roads in remote rural areas, expand railway networks, construct telecommunications infrastructure, and establish stations and outposts for their security apparatus. Alongside these efforts—and in some cases facilitated by them—states typically seek to centralize their administration, strengthen tax collection and police presence, and provide public goods as they broaden their ability to project power and penetrate more deeply into society (Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017; Lindvall and Teorell Reference Lindvall and Teorell2016; Müller-Crepon, Hunziker, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Hunziker and Cederman2021).Footnote 4

Disruption and Contention During State Centralization

While stronger states can effectively monopolize violence, enforce rules, and centrally administer territory and social groups (Weber Reference Weber1968), the process of state-building itself can be contested and contentious (Boone Reference Boone2003; Garfias and Sellars Reference Garfias and Sellars2022). We build on seminal theories of state formation that emphasize the development and consolidation of a centralized administrative network across the territory. Transportation and communication infrastructures that connect localities more directly to central government authorities enhance the ability of the state to penetrate society through the control and administration of local activity and rules, extraction in the form of taxation and military service, and the disruption of existing social relations and expectations. In France, as throughout Europe, this historic process entailed the extension of authority over—and even the absorption of—disparate regional nobles, lords, church authorities, and other elites (Elias Reference Elias[1939] 1994).

Our focus, however, highlights how this process was characterized by frictions with society more broadly, and to a lesser degree, by frictions with regional elites. Indeed, the material consequences of increased but incomplete state power can generate social contestation and popular resistance stemming from the greater local capacity of the state to enforce taxes, carry out rules of justice, and conscript civilians into military service. It can also result from the crowding out of private interests and activities in spaces that the state comes to dominate. These consequences of state expansion disrupt status-quo activities and expectations, generating grievances.Footnote 5 At the same time, the state may lack sufficient coercive power and legitimacy to deter popular challenges, a dynamic that has been documented in other contexts of state-building (e.g., Pruett Reference Pruett2024).

The extent of contestation stirred by state efforts at expansion and centralization may also vary across the territory in accordance with pre-existing fragmentation in authority and administration. Centralizing states routinely encounter regional divisions linked to historical competing authorities and power centers across their territorial expanse, which can, as Migdal (Reference Migdal1988) highlights, condition the interactions between society and the state. That poses a challenge to the state’s ability to effectively penetrate and order society in a consistent fashion across space and can raise regionalized grievances and backlash. This raises the potential for the link between state-building and unrest to be characterized at least in part by heterogeneity across space in accordance with fragmentation.

We explore these dynamics in pre-Revolutionary France, where increased connectivity and penetration of society associated with state centralization fostered disruption and social unrest. While this relationship prevailed across the entire French territory, it also varied to some extent with pre-existing administrative fragmentation: where fragmentation mapped onto historic disparities in the mode of ruling and extent of intended extraction by the state, opposition to the state’s imposition of central authority through new horse-post relays varied accordingly.

STATE-BUILDING AND REBELLION IN THE RUN-UP TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

Eighteenth-century France remained an overwhelmingly rural society, undergoing gradual yet profound transformations with deep historical roots (Ladurie Reference Ladurie1966). In the countryside, the state, the nobility, and the Church competed for dominance, generating persistent frictions and local conflicts. By Lefebvre’s (Reference Lefebvre1947) classic account, this competition gave rise to a dense web of taxes, tithes, and seigneurial dues that weighed increasingly heavily on the peasantry in run-up to the Revolution. Canonical studies have examined how these burdens spurred grievances and uprisings, and resulted in a revolution (de Tocqueville Reference de[1856] 2010; Shapiro and Markoff Reference Shapiro and Markoff1998). Recent scholarship points to additional factors behind peasant revolts during this period, such as adverse climatic shocks (Chambru Reference Chambru2019; Waldinger Reference Waldinger2024) and the degree of centralization of the tax collection system (Degrave Reference Degrave2023).

There is broad consensus, however, that the monarchy made significant strides during this period in centralizing and extending its authority, as its influence spread across the kingdom and into peripheral provinces (Burguière and Revel Reference Burguière and Revel1989). As the state expanded and assumed a more prominent role in controlling daily life—though still far from an all-encompassing one—it disrupted the delicate balance of relationships, obligations, and expectations that had long structured society. A key element of this expansion was the monarchy’s exclusive communication network: the horse post (poste aux chevaux).

The Functioning of the Horse-Post Relay Network

From its inception under Louis XI in the late 1470s, the horse post served as a pivotal state-building instrument of the royal authority to consolidate its informational capacity across the kingdom, particularly in its outlying provinces (Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 183–221).Footnote 6 This infrastructure consisted of a nationwide network of relays where horse-post messengers (postillons) could exchange their horses for fresh ones in order to ensure the rapid transportation of directives, reports, and other communications of the royal administration (Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001; Marchand Reference Marchand2006; Gazagnadou Reference Gazagnadou2013, 109–16). Relays were spaced at regular intervals of 10–15 kilometers, allowing riders to switch horses after an hour or two of travel. This system enabled postillons to maintain high speeds while minimizing the risk of injury to the horse, in line with their physiological limits (Minetti Reference Minetti2003).Footnote 7 The horse-post relay network was connected by a road infrastructure maintained by the Bridges and Roads (Ponts et Chaussées) administration, which operated independently of the horse post (Arbellot Reference Arbellot1973).

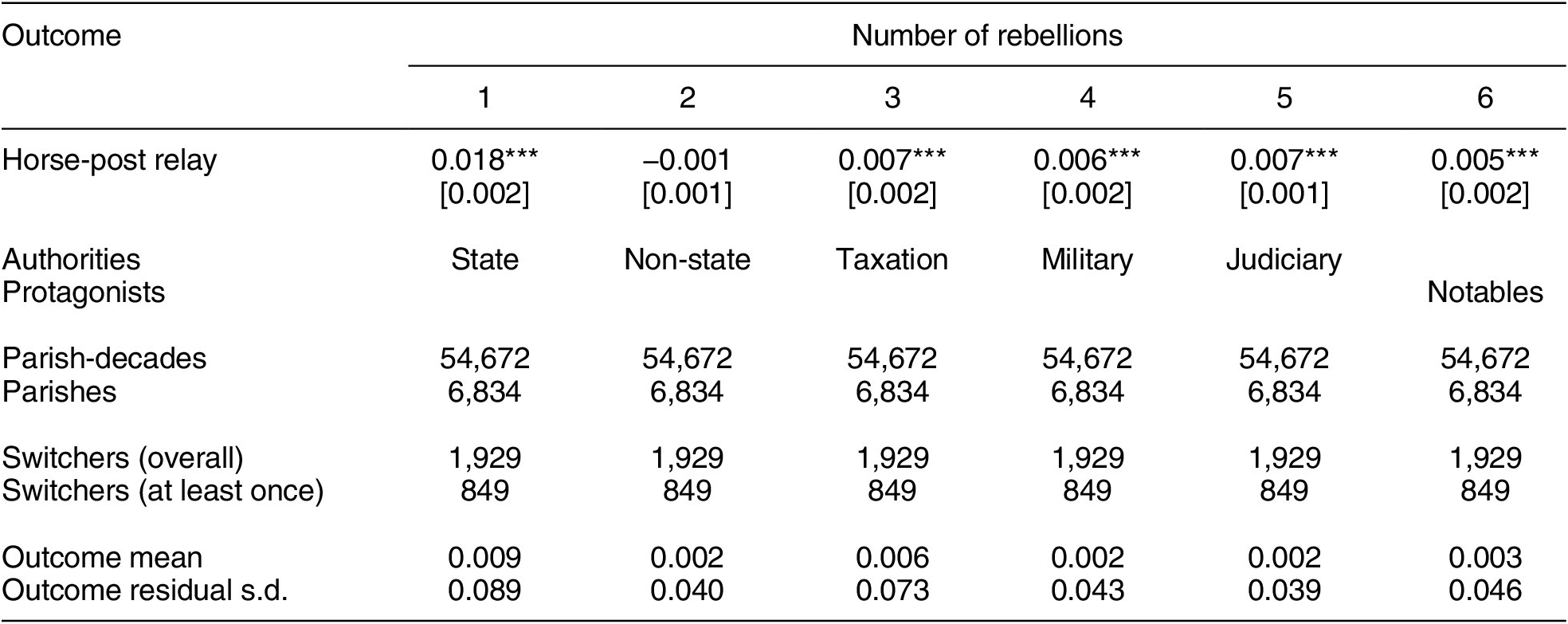

Located at the entrances to towns or at rural crossroads, horse-post relays were relatively large buildings—comprising stables, lodging quarters, and often a tavern—that stood out prominently in the rural landscape (see Panel a of Figure 1). The postillons who galloped postal roads day and night were typically young local laborers, easily identifiable by their distinctive uniforms: a royal-blue vest, a round leather hat, leather breeches, heavy black boots, and an arm badge bearing the name of their relay (Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 237–40; Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 258–64). Their horses, bred in royal stud farms, were superior to those of private horse renters and bore distinctive markings, such as a knotted or trimmed tail (Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 262–7; Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 270–5). Together, postillons’ uniforms and horses made them instantly recognizable in the public space (see Panel b of Figure 1).

Figure 1. Depictions of the Horse Post

Note: This figure displays contemporary depictions of an eighteenth-century horse-post relay in Panel a and a postillon galloping two horses back to a relay in Panel b. Sources: in Panel a, lithography by Victor-Jean Adam and Louis-Philippe-Alphonse Bichebois, based on a painting of Jean-Antoine Duclaux, La malle au relai [sic], 1817; in Panel b, painting of the French School, Postillon en livrée ramenant deux chevaux au galop, mid-nineteenth century. © Musée de La Poste, La Poste, photographs by Thierry Debonnaire.

In addition to the short distance between relays—which allowed for frequent changes of horses—a series of regulations enabled the horse-post system to achieve a higher speed of information transmission than alternative postal systems available to the general public, such as the letter post or private messenger companies (Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 100–8).Footnote 8 Indeed, postillons held a monopoly on galloping and on traveling at night on roads connecting relays, which were generally better maintained by the Bridges and Roads administration than other roads and directly connected to administrative centers (Arbellot Reference Arbellot1973, 766). The horse post also held a monopoly on horse rentals along these roads, effectively preventing private travelers from switching horses when traveling along them.Footnote 9 In addition, it had priority access to hay for feeding horses and the right of passage on congested roads. Postmasters (maîtres de postes) profited substantially from these privileges and were quick to report violations to their intendant—the provincial representative of the monarchy—who usually swiftly enforced these regulations (Vaillé Reference Vaillé1953, 166–70; Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 101–4).

The establishment of horse-post relays provided the opportunity for the royal authority to form alliances with and co-opt local elites who came to serve as postmasters. Postmasters were typically recruited among wealthy local notables—bourgeois farmers and innkeepers aspiring to noble status (Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 189–94; Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 223–8). Each held a postal certificate (brevet de poste) that granted them the exclusive right to operate a given relay. The certificate imposed several obligations on postmasters: they were required to reside at the relay, to manage their relay directly (faire-valoir direct) and not farm out its operations, and to maintain its proper functioning—such as keeping at least five or six healthy horses available at all times. In addition, they were expected to serve as intelligence agents and auxiliary police on behalf of the central administration (Vaillé Reference Vaillé1953, 268–71; Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 210–4). Their duties included monitoring passengers passing through the relay—by the late eighteenth century, this involved keeping records of names, occupations, and destinations—as well as reporting notable local political events to their intendant.

Overall, the horse-post relay network positioned the state as the sole authority controlling rapid communications in France, significantly expanding its ability to monitor society and exert control over its territory.

Consequences of the Horse Post for Local Order and Rebellion

The development of the horse-post relay network had several distinct consequences. At the national level, it enabled the rapid communication essential to the effective functioning of the state. For instance, it allowed central officials, tax farmers (fermiers généraux), and provincial intendants and local tax officials (élus) to coordinate swiftly through directives, reports, and fiscal orders on matters of tax collection and enforcement. That included efforts to suppress salt smuggling (faux-saunage) across the kingdom’s disparate and consequential salt-tax zones (gabelles). This coordination required frequent and timely exchanges between central administrators and local agents, who were responsible for estimating tax yields and implementing their collection (Caillou Reference Caillou2005, 177–293; Deharbe Reference de2010, 243–344). The speed of communication was especially critical in times of crisis, such as in the aftermath of natural disasters (Favier Reference Favier and Legay2007). The horse-post system also facilitated the transmission and enforcement of military recruitment orders, enabling directives to travel efficiently from central authorities to intendants and onward to local recruitment and conscription officers (Corvisier Reference Corvisier1964, 147–61).

Beyond these nationwide implications, the expansion of the horse-post relay network disrupted local social equilibria. A range of local actors benefited from these developments. Chief among them were postmasters. In addition to the profits they derived from their exclusive right to operate a relay, postmasters enjoyed a wide range of privileges, including substantial exemptions from taxation—most notably, from the onerous taille—as well as relief from military obligations, from accommodating passing soldiers, and from churchwarden responsibilities (Demangeon Reference Demangeon1995, 44–8; Tonnaire Reference Tonnaire2005, 48–59). They were also exempt from taxes on ancillary activities tied to relay operations, such as the sale of wine in the relay’s tavern. These material advantages fostered broad loyalty to the monarchy among postmasters (Vaillé Reference Vaillé1953, 233–48; Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 189–235; Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 200–46).Footnote 10 Other local groups also derived material benefits from the introduction of horse-post relays: innkeepers benefited from the increased traffic along roads connecting relays (Tonnaire Reference Tonnaire2005, 59–63), and families allied with postmasters often enhanced their local influence through closer ties to representatives of the royal authority (Tonnaire Reference Tonnaire2005, 48).

Local elites also likely benefited from the establishment of horse-post relays, as improved communication with provincial and central authorities may have enhanced their influence and elevated their status. For instance, historical accounts suggest that tax agents often relied on the knowledge and assistance of local notables as they traveled along the relay network in preparation for their annual round of tax collection (Caillou Reference Caillou2005, 177–293; Deharbe Reference de2010, 243–344). These interactions may have fostered mutually beneficial relationships, reinforcing the authority of local elites and further integrating them into the state’s administrative and logistical apparatus. Local notables may also have engaged with military officials and royal agents passing through or lodging at relays, for instance, by sharing local information, though such ties were likely kept discreet and remain difficult to corroborate in historical records.

By contrast, the various monopolies associated with the horse post crowded out competing private interests. First and foremost, horse-rental businesses were severely disrupted by the ban on renting their horses along roads connecting horse-post relays. Indeed, examples of horse renters attempting to violate this ban abound (e.g., Jamaux-Gohier Reference Jamaux-Gohier2001, 101–4).Footnote 11 Local farmers and innkeepers situated off postal roads also lost out, as postmasters had priority access to hay and animal fodder for their relays—a shortage potentially worsened by the increased demand brought on by rising traffic along postal roads (Tonnaire Reference Tonnaire2005, 61–4). More broadly, the monopolization of these roads by the monarchy through the horse post imposed constraints on travelers as privately owned horses were restricted to trotting during daytime and could not be exchanged at horse-rental establishments.Footnote 12

Additional social groups, such as commoners, peasants, and merchants, may have also lost out with the establishment of horse-post relays as they brought increased surveillance and stricter enforcement of state regulations. Indeed, enhanced state communication through the horse-post relay network likely made it easier for authorities to monitor and enforce tax collection, military conscription, and judicial decisions. In addition, local residents could have been subjected to new burdens, including maintaining postal roads through the unpaid labor system of the corvée (Tonnaire Reference Caillou2005, 65–86; Conchon Reference Conchon2016).

We hypothesize that these disruptions to local society fueled grievances, and eventually rebellion, though the material consequences of a new horse-post relay likely took time to fully materialize and for discontent to boil over. Adverse events such as repeated food shortages, tax enforcement campaigns, labor requisitions, or conscription orders, combined with policy changes such as tax increases or stricter judicial procedures or penal codes, could have tipped simmering discontent into open rebellion. State agents who contributed to—or were perceived as contributing to—these pressures could have become targets of local hostility. Counterfactual parishes that did not host new horse-post relays were less exposed to such state intrusion and thus avoided the same stratifying pressures that divided communities into winners and losers of state centralization. Hence, residents of these parishes may not have experienced these adverse events to the same degree, and where they did experience them, they might have been less inclined to attribute them to the presence or actions of state agents.

Several rebellious events in our data exhibit just such reactions against state agents and activities. One example occurred in 1781 in the town of Mirande, in the southwestern généralité of Auch. A decade earlier, the establishment of a new horse-post relay marked a deeper state presence in this formerly isolated region of the kingdom, as before the 1770s, this généralité had only two relays, in Pau and Orthez. Military recruitment in the area had long been among the lowest in France, but the increased needs resulting from the Anglo-French War (1778–83) brought renewed scrutiny to local enlistment.Footnote 13 In this context, the new horse-post relay facilitated information gathering on draft-eligible men. In 1781, as the subdélégué (the local representative of the monarchy), military officers, and local notables assembled in Mirande to conduct a conscription draw, draft-eligible peasants and farmers emerged from the forest with sticks and knives, shouting at the authorities, “They should all be killed!” A confrontation over draft resistance followed, resulting in several arrests before a local notable managed to defuse the situation.

A rebellion in the coastal town of Blaye in Gironde in 1783, just three years after the introduction of a horse-post relay, offers another revealing example. Members of a patache brigade—widely despised mobile tax-farming agents charged with collecting gabelles and seizing contraband—attempted to inspect the load of a Breton ship.Footnote 14 Following the establishment of a series of new relays connecting La Rochelle to Bordeaux along the eastern shore of the Gironde Estuary in the early 1780s, patache patrol boats began to more closely monitor maritime commerce in the region, including in Blaye. When the patache approached, the ship’s crew resisted inspection and joined forces with local residents to stone the patache agents once ashore at the encouragement of the ship’s captain and the owner of the merchandise. Members of the crew denounced the patache brigade as an “enemy of society” that had come to “outrage citizens” who were merely going about their usual business. In short, heightened tax enforcement facilitated by the recent expansion of the horse-post relay network sparked a wave of local resentment that quickly escalated into open resistance.

Other examples illustrate how the introduction of horse-post relays could have crowded out private interests. About a decade after a series of relays was established along the route between Dijon and Auxerre, members of the local bourgeoisie complained that inns near the new relays were monopolizing supplies of food and animal fodder (Tonnaire Reference Tonnaire2005, 63–4). In response, the subdélégué issued a ban preventing innkeepers from making early purchases at local markets to preserve access for other buyers—setting, for instance, an 8 a.m. cutoff in Avallon. Tensions between innkeepers and the bourgeoisie escalated, and although the restriction remained in place despite numerous complaints from innkeepers, many of the underlying grievances persisted. In another such example in 1775 in Picardy, in the context of the Flour War, a crowd of townspeople in Chauny attacked and ransacked the local horse-post relay on rumors that the postmaster had stockpiled wheat despite the local shortage. A detachment of troops was unable to stop the crowd.

Of course, horse-post relays could have impacted rebellion through other channels beyond those illustrated in these examples. For instance, they could have generated local income shocks, disrupted traditional social hierarchies, introduced more policing, and called attention to the recording and registration of rebellious activities. We examine these and other potential alternative mechanisms below.

DATA

Our analysis dataset comprises a panel of 35 thousand parishes of the kingdom of France as of 1789—except for Corsica—spanning eight decades from the 1710s to the 1780s. Parishes were the smallest units of administration in Ancien Régime France and no prior study has analyzed this period at such a granular level.Footnote 15 Further details on data sources are provided in the Data Appendix section of the Supplementary Material. For replication data, see Albertus and Gay (Reference Albertus and Gay2025).

The Horse-Post Relay Network

To document the development of the horse-post relay network over the eighteenth century, we construct an original historical geographic information system (GIS) based on administrative sources.Footnote 16 Beginning in 1708, the General Superintendent of Posts had a list of horse-post relays printed and updated annually: the Liste générale des postes de France (Arbellot Reference Arbellot1980, 100–2; Reference Arbellot1992, 110–4). This publication was designed to provide state messengers with the locations of horse-post relays together with distances between them. Each Liste des postes was organized by itinerary, with departure and destination relays clearly marked.Footnote 17 Distances were reported in postes—a measure of distance equivalent to 8–12 kilometers (Bretagnolle and Verdier Reference Bretagnolle and Verdier2006, 68–9).Footnote 18

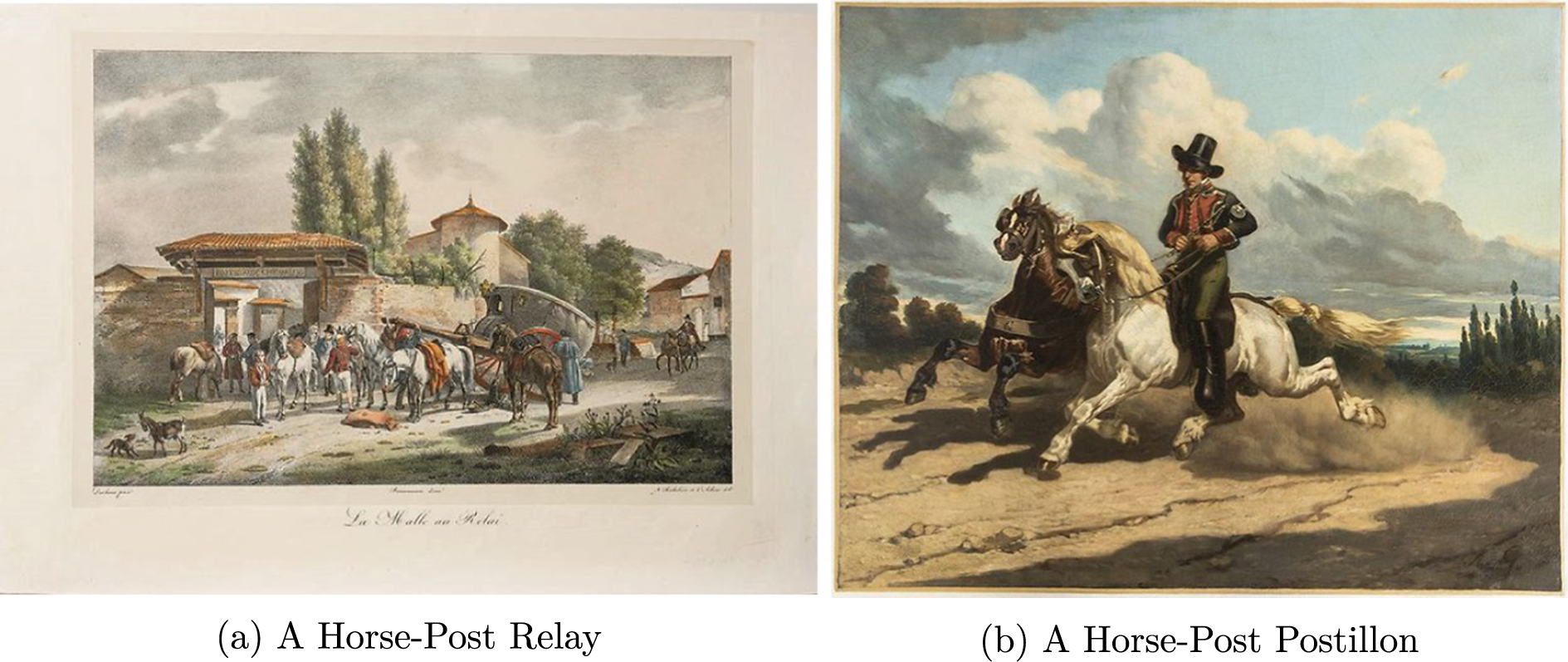

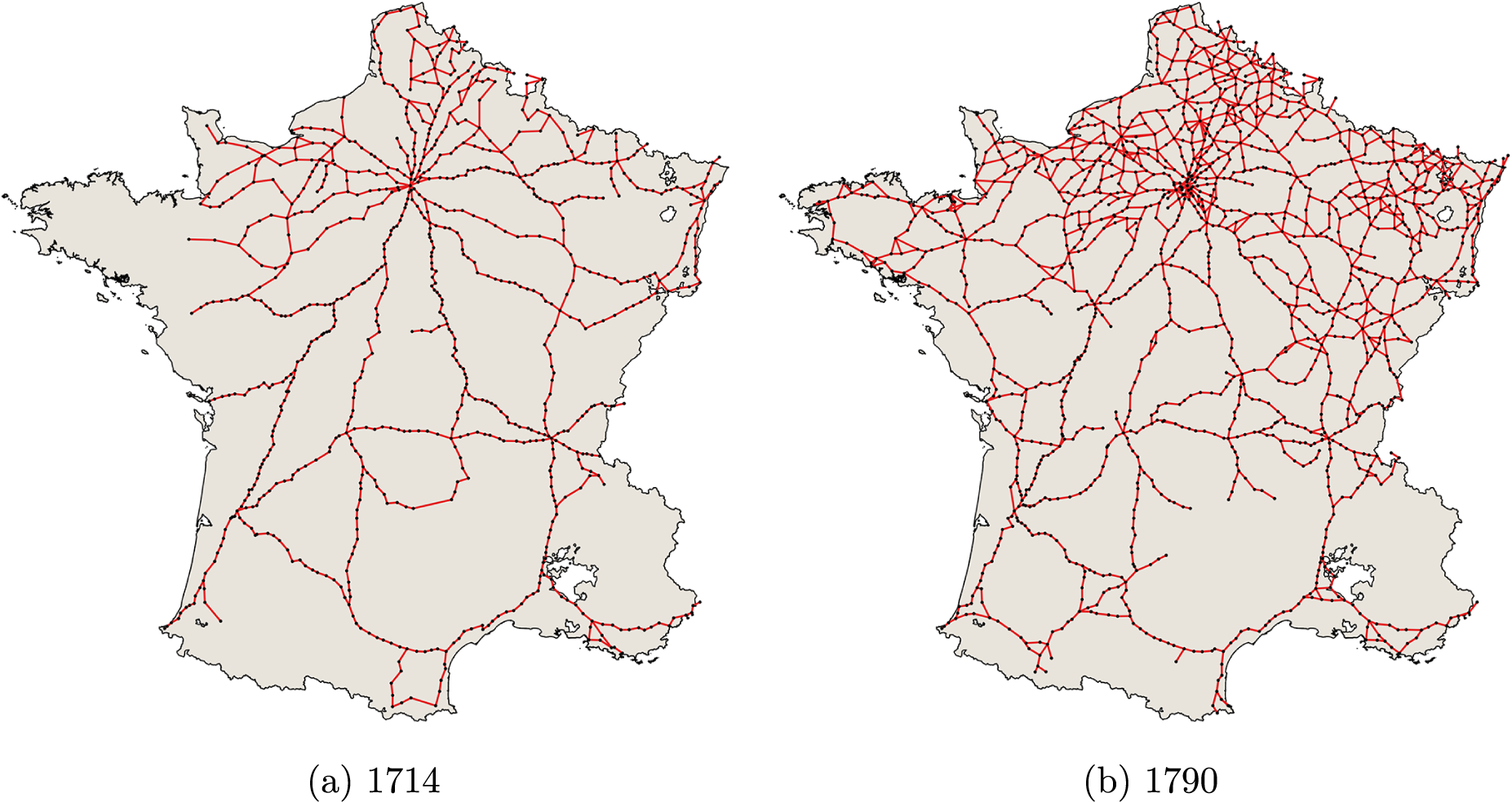

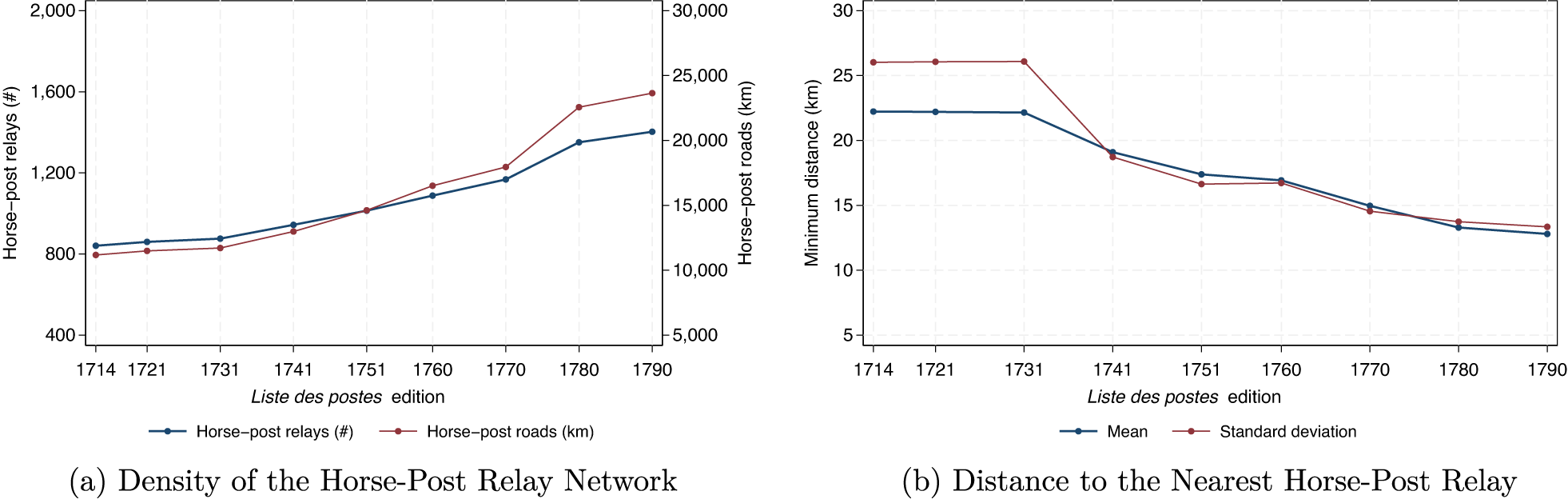

We digitized one edition of the Liste des postes per decade from the 1710s through the 1790s.Footnote 19 From each edition, we extracted all the segments between relays as listed by itinerary and matched each location to the corresponding parish. We then reconstructed itineraries by drawing straight lines between successive relays and combining the resulting segments. Figure 2 displays the spatial distribution of the horse-post relay network at the beginning and end of our period of analysis.Footnote 20 We also report the number of horse-post relays along with the length of associated postal roads for each edition of the Liste des postes included in our sample in Panel a of Figure 3.

Figure 2. The Horse-Post Relay Network

Note: This figure displays the horse-post relay network based on the 1714 and 1790 editions of the Liste des postes. Horse-post relays correspond to black dots while horse-post roads, to red segments. The underlying shapefile of the kingdom of France as of 1789 is based on Gay, Gobbi, and Goñi’s (Reference Gay, Gobbi and Goñi2024a) jurisdictions database.

The spatial configuration of the horse-post relay network at the beginning of the eighteenth century reflected the monarchy’s long-standing strategic and military concerns vis-à-vis neighboring adversaries, consistent with accounts of subnational state-building efforts that emphasize responses to prevailing geopolitical and bellicist threats (Boone Reference Boone2003; Tilly Reference Tilly1990). In the late fifteenth century, relays were established in Bordeaux, Dijon, Lyon, Arras, and Amiens due to their strategic positions relative to the Kingdoms of Spain and England, the Duchies of Burgundy and Savoy, the County of Flanders, and the Holy Roman Empire (Gazagnadou Reference Gazagnadou2013, 112). During the sixteenth century, postal routes expanded toward the kingdom’s borders, with relays established in Bayonne under Louis XII and in Nantes under Henry III. This strategic expansion continued throughout the seventeenth century, following territorial conquests: northeastward to Strasbourg after the Peace of Westphalia (1648), southwestward to Narbonne after the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), and eastward to Besançon after the Treaties of Nijmegen (1678–79) (Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 186–8). These strategic and military concerns led to a center-periphery logic resulting in a star-shaped network radiating from Paris and reinforced by key nodes along the kingdom’s borders.Footnote 21

In contrast, the eighteenth century was a period of internal densification of the horse-post relay network (Bretagnolle and Verdier Reference Bretagnolle and Verdier2005; Reference Bretagnolle, Verdier and Roux2007; Verdier Reference Verdier2009). By then, the horse post had become a key instrument in the monarchy’s strategy to assert a more uniform and centralized control over the territory and to project its power into the remotest parts of the kingdom (Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 189).Footnote 22 The network first densified in the north following the permanent establishment of the royal court at Versailles in 1682 and the consolidation of the kingdom’s territorial boundaries. From the mid-eighteenth century onward, the network expanded around regional centers, such as Bordeaux, Lyon, Dijon, Toulouse, and Rennes. By the end of the century, the horse post had evolved into a national network structured around the political center in the north and connected to secondary centers, creating the conditions for the emergence of an integrated city system (Bretagnolle and Franc Reference Bretagnolle and Franc2017).

Figure 3. Evolution of the Horse-Post Relay Network

Note: Panel a displays the evolution of the number of horse-post relays and the length of postal roads in kilometers from 1714 to 1790. Panel b displays the mean and standard deviation of the distance from the 35 thousand parishes in our sample to the nearest horse-post relay in kilometers. Horse-post relay data are based on various editions of the Liste des postes.

We quantify the expansion of the horse-post relay network over the eighteenth century in Panel a of Figure 3. The network grew steadily, essentially doubling both in length and density over the period. Whereas in 1714, it comprised 841 relays spanning 11 thousand kilometers of postal roads, by 1790, it had expanded to 1,403 relays covering 24 thousand kilometers.Footnote 23 This expansion substantially improved local accessibility to the network, as the average distance between a parish and the nearest relay decreased from 22 kilometers in 1714 to 13 kilometers in 1790, as shown in Panel b of Figure 3. These gains were spread across all parishes, as the standard deviation of this distance also fell from 26 to 13 kilometers.Footnote 24 More broadly, the proportion of parishes located near a horse-post relay rose substantially, from 18% in 1714 to 31% in 1790.Footnote 25

However, the development of the horse-post relay network was not entirely linear as it was periodically reconfigured at the local level (Bretagnolle and Verdier Reference Bretagnolle, Verdier and Roux2007; Verdier Reference Verdier2009). While net gains amounted to 562 relays over the eighteenth century, this reflected the creation of 1,001 relays and the retirement of 439 of them.Footnote 26 In particular, substantial reconfigurations occurred in the interior of the country in the 1740s and 1750s—between Bordeaux and Limoges, Bordeaux and Poitiers, Poitiers and Tours, and Lyon and Clermont-Ferrand. These reconfigurations were generally driven by local practical considerations, such as the retirement of a postmaster or the development of nearby roads in better condition (Arbellot Reference Arbellot1980, 106).Footnote 27 A comparison of the spatial distribution of newly established and retired relays by decade reveals that retired relays were, on average, 11 kilometers away from the nearest new relay.

While the initial configuration and expansion of the horse-post relay network were largely shaped by national strategic considerations, its local development over the eighteenth century was driven by practical constraints. Beyond the quality of the road network, the specific placement of relays was primarily determined by the need to maintain regular 10–15 kilometer intervals—reflecting the physiological limits of horses (Minetti Reference Minetti2003). As a result, many relays were located in small towns and villages situated along routes between administrative centers, often on riverbanks or on foothills.Footnote 28 Accordingly, about one-third of relays were located in cities with more than two thousand inhabitants—typically administrative centers—while nearly half were in towns with fewer than a thousand inhabitants, and 19% in villages with fewer than five hundred inhabitants.Footnote 29 Horse-post relays established after 1714 were even more likely to be located in smaller towns and villages.

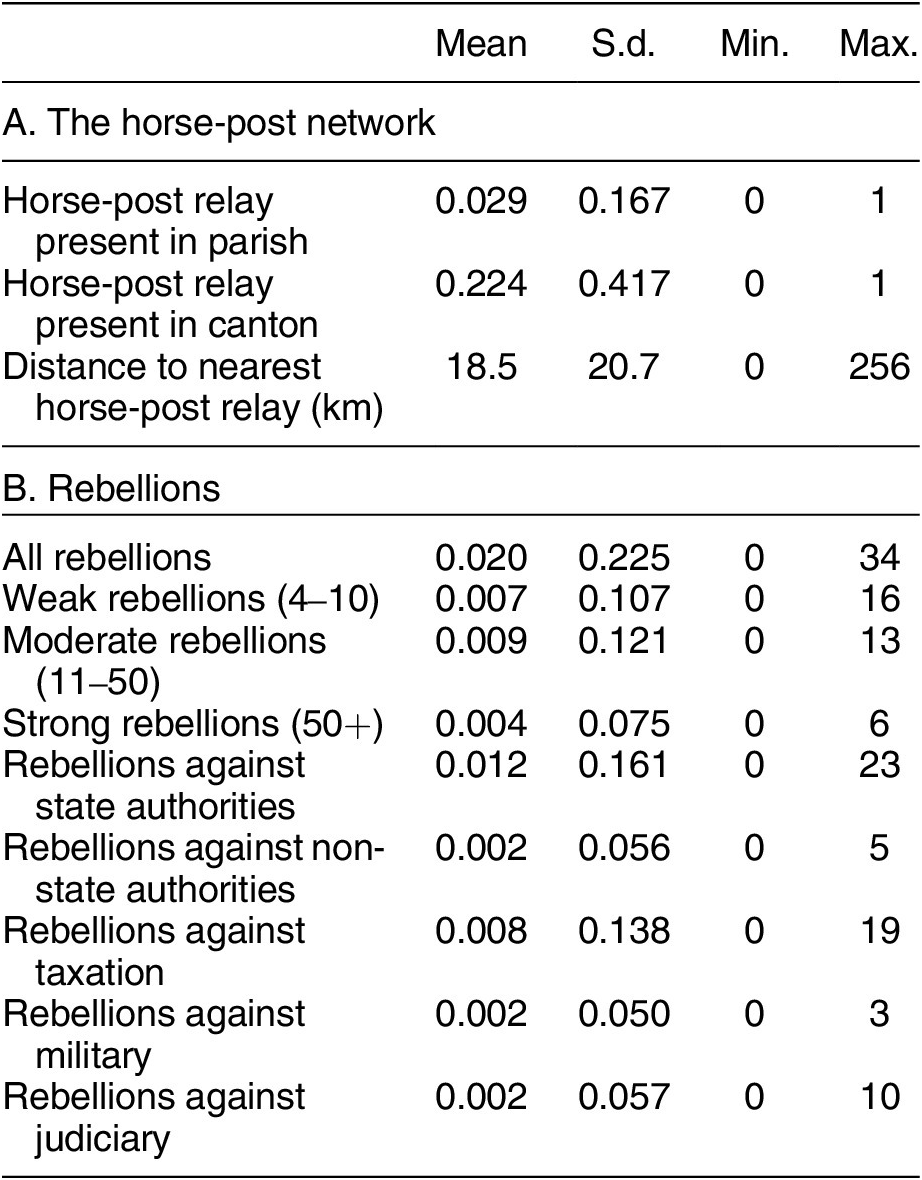

Summary statistics on the horse-post relay network at the parish-decade level are reported in Panel A of Table 1.Footnote 30

Table 1. Summary Statistics across Parish-Decades

Note: This table reports summary statistics for the main variables used in the analysis, excluding the city of Paris. The unit of observation is a parish-decade from the 1710s to the 1780s. There are 282,288 parish-decade observations in the dataset. State authorities include the fiscal, military, and judiciary authorities. Non-state authorities include the nobility, seigneurial and municipal authorities, and the Church.

Rebellions

We collect data on eighteenth-century rebellions from the Jean Nicolas survey (Nicolas Reference Nicolas and Nicolas1985; Reference Nicolas2002).Footnote 31 Compiled from extensive archival research conducted from the early 1980s to the late 1990s, this survey documents 8,516 rebellions that occurred between 1661 and 1789 (Gay Reference Gay2025, 7–11). It focuses on popular uprisings aimed at challenging authorities, protesting subsistence crises, or resisting state and local policies and actions—it excludes brigandage and strictly criminal activities. The survey sets an inclusive threshold, recording any uprising that lasted only a few hours or involved as few as four individuals. These criteria thus cast a wide net, making the Jean Nicolas survey an unparalleled thermometer of the rebellious fever that swept through France in the run-up to the Revolution.

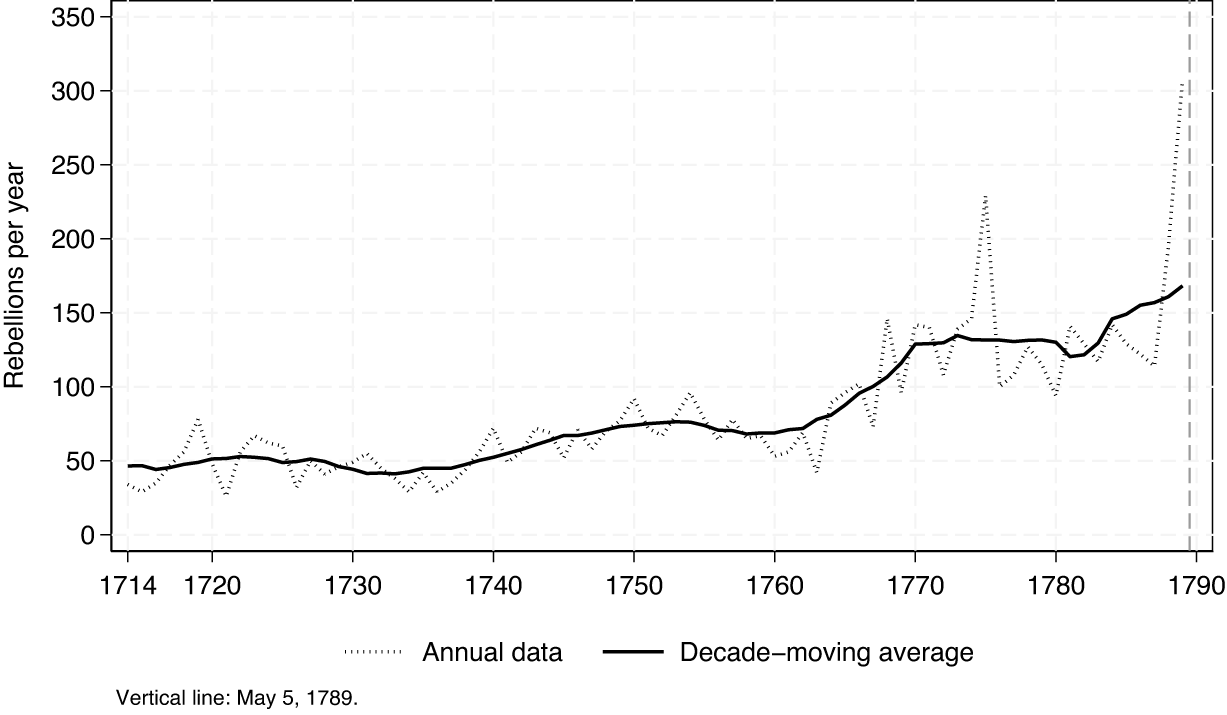

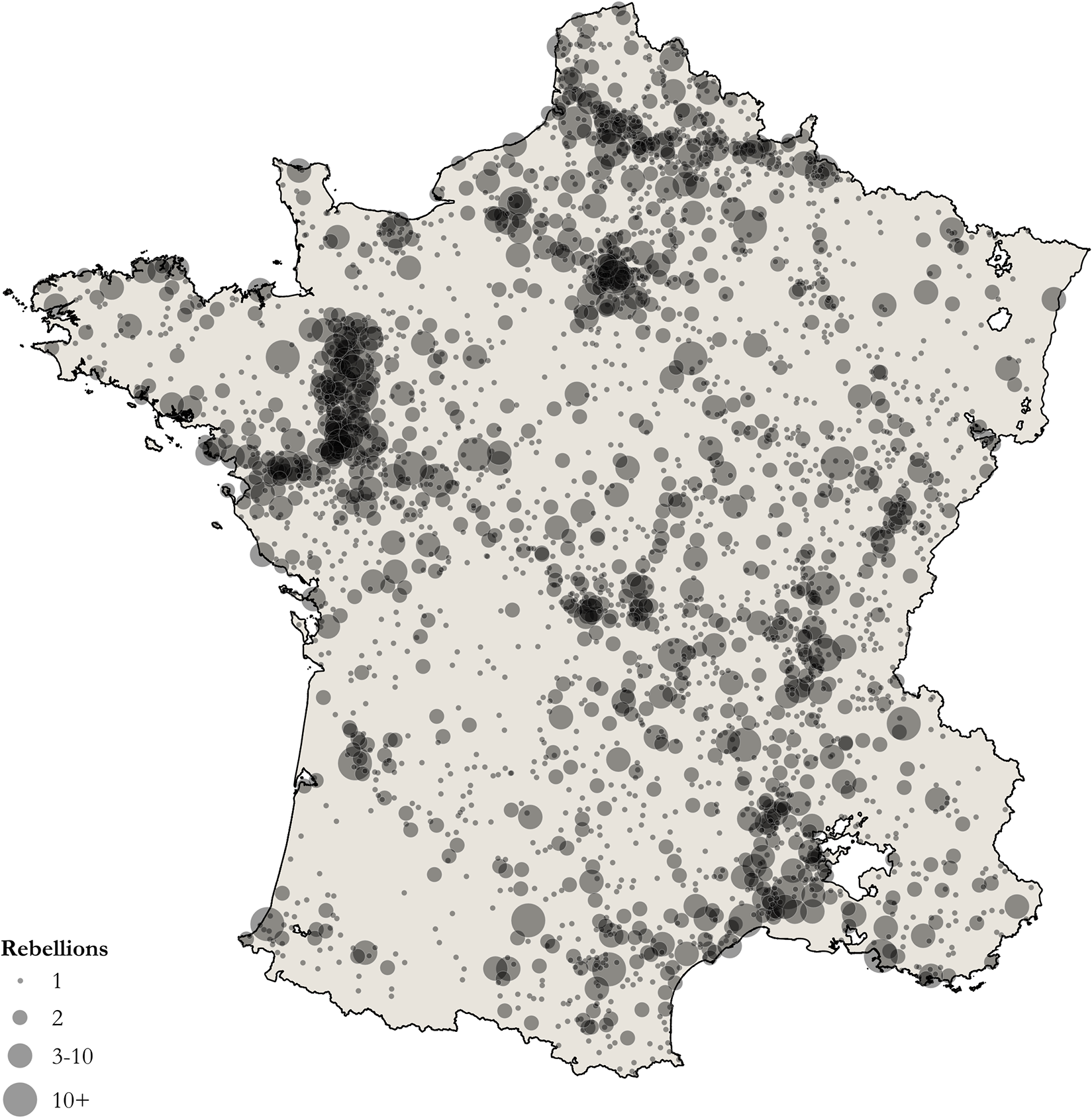

Figure 4 depicts trends in rebellious activity between 1714 and 1789, our period of analysis. Rebellions began to intensify in the 1740s before accelerating sharply in the 1760s, with more than a hundred events per year from that point onward. This escalation coincided with the growing presence of the state across the territory and rising levels of taxation (Burguière and Revel Reference Burguière and Revel1989).Footnote 32 Rebellious activities further intensified until the outbreak of the Revolution. Their territorial spread—over about three thousand locations—is shown in Figure 5.Footnote 33

Figure 4. Annual Number of Rebellions

Note: This figure displays the annual number of rebellions from 1714 to 1789 based on Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) original survey along with a decade-moving average.

We digitized all forty thousand original coding sheets of Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) survey to construct a comprehensive database of the 6,000 rebellions that took place in 3,172 parishes within the boundaries of the kingdom of France between 1714 and 1789.Footnote 34 In addition to recording the date and location of each event, we also collected information on its motives, size, and the characteristics of its participants.Footnote 35 To measure rebellious activity, we create a variable that counts the number of rebellions per parish and decade. We report summary statistics in Panel B of Table 1.Footnote 36

Figure 5. Spatial Distribution of Rebellions (1714–89)

Note: This figure displays the spatial distribution of rebellions from 1714 to 1789 based on Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) original survey. Each point corresponds to a parish that experienced at least one rebellion over the period—6,000 rebellions across 3,172 parishes in total. The underlying shapefile of the kingdom of France as of 1789 is based on Gay, Gobbi, and Goñi’s (Reference Gay, Gobbi and Goñi2024a) jurisdictions database.

Nearly half of all rebellions (46%) that occurred from 1714 to 1789 were of moderate size, involving between 11 and 50 participants. Another 21% were relatively large, with more than 50 participants. State authorities were targeted in 60% of rebellions, while 11% were directed against non-state actors—the nobility, seigneurial and municipal authorities, and the Church. Among rebellions against the state, most were aimed at taxation (66%), followed by the military (19%) and the judiciary (23%).Footnote 37 Finally, 69% of rebellions in our sample include information on the social categories of their participants. Among these, 39% involved laborers; 32%, craftsmen; 23%, notables; and 22%, socially marginalized individuals.Footnote 38 The rebellions in our dataset thus span a broad range of the social strata of French society.

While Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) survey remains the most comprehensive source of rebellious activity in France prior to the Revolution, its use requires careful attention to potential gaps and reporting biases common to historical data (Gay Reference Gay2025, 29–46). These include not only the archival recording of events, but also the possibility that the establishment of a horse-post relay may have increased the capacity of state or local authorities to record rebellions. We address these concerns below by assessing the robustness of our results to these potential sources of bias, showing that they are unlikely to account for our findings.

Administrative and Territorial Divisions

Central for our empirical strategy, parishes were embedded within a hierarchical system of administrative and territorial divisions. The largest of these were généralités. Created in the fourteenth century, these broad territorial divisions served as the basis for the administration of the territory under the authority of intendants (Gorry Reference Gorry and Zadora-Rio2014). On the eve of the Revolution, there were 32 généralités.Footnote 39 Subdélégations were territorial divisions established in the mid-seventeenth century as subdivisions of généralités to extend the territorial reach of the royal authority at the local level. The prerogatives of subdélégués—the royal agents who administered subdélégations under the authority of the intendant of their généralité—increased during the eighteenth century to encompass the fiscal, military, economic, social, and sanitary administration of their territory (Goubert, Arbellot, and Laclau Reference Goubert, Arbellot, Laclau, Nordman, Ozouf-Marignier and Laclau1989). By 1789, there were nearly 700 subdélégations. A more localized territorial unit was the canton, which held various electoral and judicial functions (Ozouf-Marignier, Graziani, and Bonin Reference Ozouf-Marignier, Graziani, Bonin, Nordman, Ozouf-Marignier and Laclau1989). Alongside parishes, cantons represented the most granular level of administration, totaling over 4,500.Footnote 40 Although they were only formally created in 1790 along with départements and districts, their territorial scope closely reflected pre-existing patterns of local interaction and daily exchange between parishes (Tanguy, Le Bihan, and Lagadec Reference Tanguy, Bihan and Lagadec2009). At the median, each généralité had 988 parishes, 782 thousand inhabitants (as of 1793), and covered a radius of 70 kilometers; each subdélégation had 39 parishes, 31 thousand inhabitants, and a radius of 15 kilometers; and each canton had 7 parishes, 5 thousand inhabitants, and a radius of 6 kilometers.

Other Data

We supplement our parish-level data with additional sources, although data for this time period remain relatively sparse. Our research design explicitly accounts for this constraint. In particular, we construct a parish-level measure of decade-average wheat prices based on data from Ridolfi (Reference Ridolfi2019), so as to control for shifting local economic conditions and for potential income shocks associated with the local development of the horse-post relay network—subsistence crises and broader changes to the price of staple foods were common triggers of collective action in eighteenth-century France (Bouton Reference Bouton1993; Chambru Reference Chambru2019; Markoff Reference Markoff1985).Footnote 41 In addition, we measure the size of each parish by its population in the 1793 census—the first census conducted in France. We also assess the connectivity of parishes to the road network based on Cassini’s maps published in 1756–90. Furthermore, we determine whether a parish served as the seat of an administrative division, and we collect information on the type of gabelle taxation regime to which it was subject. Finally, we construct a historical GIS of both the letter-post system and maréchaussée brigades, which we describe in more detail below.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The substantial variation in rebellious activity and the expansion of the horse-post relay network over the eighteenth century offer a unique opportunity to examine how state-building efforts affected unrest in the run-up to the French Revolution. Our primary estimand of interest is the causal effect of the establishment of a horse-post relay in a parish on subsequent rebellious activity in that parish over time. While rebellions ultimately stem from social and economic changes, the introduction of a relay could have triggered these changes and their associated grievances.

We employ a staggered difference-in-differences design that compares changes in rebellion in parishes that received (or lost) a horse-post relay to those that would later receive (or lose) one. This strategy accounts for fixed parish-level characteristics that might influence both the likelihood of receiving a relay and the propensity for rebellion, such as a prior history of political activism, ease of collective action, the structure of civil society, or the presence of natural resources. It relies on the identifying assumption that, absent the introduction of a relay, parishes that received a new relay and those that did not would have followed parallel trends in rebellion. While this assumption is fundamentally untestable, we assess its plausibility through event-study regressions below.

Our treatment is staggered, binary, and non-absorbing, as parishes could both enter and exit treatment over time. Within our sample, 33,602 parishes (95.2%) were never treated—they never hosted a horse-post relay between 1714 and 1789. Another 586 (1.7%) were always treated—they maintained a relay throughout the period. The remaining 1,099 (3.1%) were “ever treated” parishes that experienced at least one change in treatment status over time. Of these, 203 (18.5%) began with a relay in 1714 but lost it at some point, while 896 (81.5%) entered treatment at least once. Among the latter, 387 (43.1%) exited treatment at least once.Footnote 42

To account for the specific features of this empirical design, we follow de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024), which provide consistent and unbiased estimators for staggered difference-in-differences models in which treatment effects may be heterogeneous as well as dynamic over time.Footnote 43 Specifically, de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille’s (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024) approach estimates period-specific average treatment effects

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

of having been treated rather than untreated for

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

of having been treated rather than untreated for

![]() $ \ell $

periods by comparing switchers to not-yet switchers with the same period-one treatment.Footnote 44 This setup also ensures that the coefficients are not “contaminated” by assuming continual exposure when parishes could exit treatment. We implement this approach at the parish-decade level by estimating the following regression equation:

$ \ell $

periods by comparing switchers to not-yet switchers with the same period-one treatment.Footnote 44 This setup also ensures that the coefficients are not “contaminated” by assuming continual exposure when parishes could exit treatment. We implement this approach at the parish-decade level by estimating the following regression equation:

$$ \begin{array}{r}{\mathrm{rebellions}}_{pda}={\alpha}_p+{\lambda}_d+{\displaystyle \sum_{\begin{array}{c}\ell =-t\\ {}t\ne 0\end{array}}^{+T}}{\delta}_{\ell}\times \unicode{x1D7D9}[{\mathrm{horse}\_\mathrm{post}}_{pd}=1]\\ {}\times \unicode{x1D7D9}[d=\ell ]+{\mathrm{prices}}_{pd}+{\gamma}_{da}+{\varepsilon}_{pda,}& \end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{r}{\mathrm{rebellions}}_{pda}={\alpha}_p+{\lambda}_d+{\displaystyle \sum_{\begin{array}{c}\ell =-t\\ {}t\ne 0\end{array}}^{+T}}{\delta}_{\ell}\times \unicode{x1D7D9}[{\mathrm{horse}\_\mathrm{post}}_{pd}=1]\\ {}\times \unicode{x1D7D9}[d=\ell ]+{\mathrm{prices}}_{pd}+{\gamma}_{da}+{\varepsilon}_{pda,}& \end{array} $$

where

![]() $ {\mathrm{rebellions}}_{pda} $

denotes the number of rebellions that occurred in decade d and parish p that is part of administrative division a. Index d ranges from 1 to 8, corresponding to decades 1710 to 1780. The indicator variable

$ {\mathrm{rebellions}}_{pda} $

denotes the number of rebellions that occurred in decade d and parish p that is part of administrative division a. Index d ranges from 1 to 8, corresponding to decades 1710 to 1780. The indicator variable

![]() $ {\mathrm{horse}\_\mathrm{post}}_{pd} $

equals one if parish p hosted a horse-post relay in decade d.

$ {\mathrm{horse}\_\mathrm{post}}_{pd} $

equals one if parish p hosted a horse-post relay in decade d.

![]() $ {\alpha}_p $

denotes parish fixed effects;

$ {\alpha}_p $

denotes parish fixed effects;

![]() $ {\lambda}_d $

, decade fixed effects;

$ {\lambda}_d $

, decade fixed effects;

![]() $ {\mathrm{prices}}_{pd} $

, average wheat prices in parish p and decade d; and

$ {\mathrm{prices}}_{pd} $

, average wheat prices in parish p and decade d; and

![]() $ {\gamma}_{da} $

, decade-by-administrative division fixed effects, where we alternatively consider subdélégations and cantons. This last term enables the coefficients

$ {\gamma}_{da} $

, decade-by-administrative division fixed effects, where we alternatively consider subdélégations and cantons. This last term enables the coefficients

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

to be identified through the comparison of parishes within the same administrative division, thus accounting for administrative division-specific time trends. We cluster standard errors at the parish level.

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

to be identified through the comparison of parishes within the same administrative division, thus accounting for administrative division-specific time trends. We cluster standard errors at the parish level.

An important practical consideration is the timing of the assignment of horse-post relays and rebellions. Our baseline approach links rebellions in a given decade to the edition of the Liste des postes published at the beginning of that decade. For instance, for the 1720 decade, we use the 1721 edition of the Liste des postes together with rebellions that occurred between 1721 and 1730.Footnote 45 A second consideration is the number of leads (t) and lags (T) to include in the estimation. While de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille’s (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024) methodology allows for up to three leads and seven lags in our setting, the preferred number of leads and lags should ensure that the estimation is based on a sufficiently comparable sample of switchers. While we report estimates for the full range, our preferred specification follows de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille’s (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024, 39–40) rule of thumb, which recommends including only those leads and lags for which at least half of ever-treated parishes contribute to the estimation. This corresponds to including two leads and three lags in our setting.

IDENTIFICATION

A causal interpretation of estimates resulting from Equation 1 requires that the development of the horse-post relay network be exogenous with respect to rebellion dynamics at the parish level. As discussed above, the initial spatial configuration of the network reflected long-standing strategic political and military concerns (Panel a of Figure 2). In contrast, its development over the eighteenth century was primarily driven by the state’s efforts to expand and centralize its authority across the interior of the kingdom, resulting in the densification of the network around major regional nodes (Panel b of Figure 2).Footnote 46 However, the opening of new horse-post relays in growing urban centers may have been endogenous to population dynamics—a potential determinant of rebellious activity. To address this concern, our preferred specification exploits local variation through decade-by-administrative division fixed effects (

![]() $ {\gamma}_{da} $

). Indeed, while the establishment of a relay in an urban center may be endogenous, the precise location of a relay between regional nodes was ultimately constrained by the need to establish rest stops every 10–15 kilometers due to the physiological limits of horses (Minetti Reference Minetti2003).

$ {\gamma}_{da} $

). Indeed, while the establishment of a relay in an urban center may be endogenous, the precise location of a relay between regional nodes was ultimately constrained by the need to establish rest stops every 10–15 kilometers due to the physiological limits of horses (Minetti Reference Minetti2003).

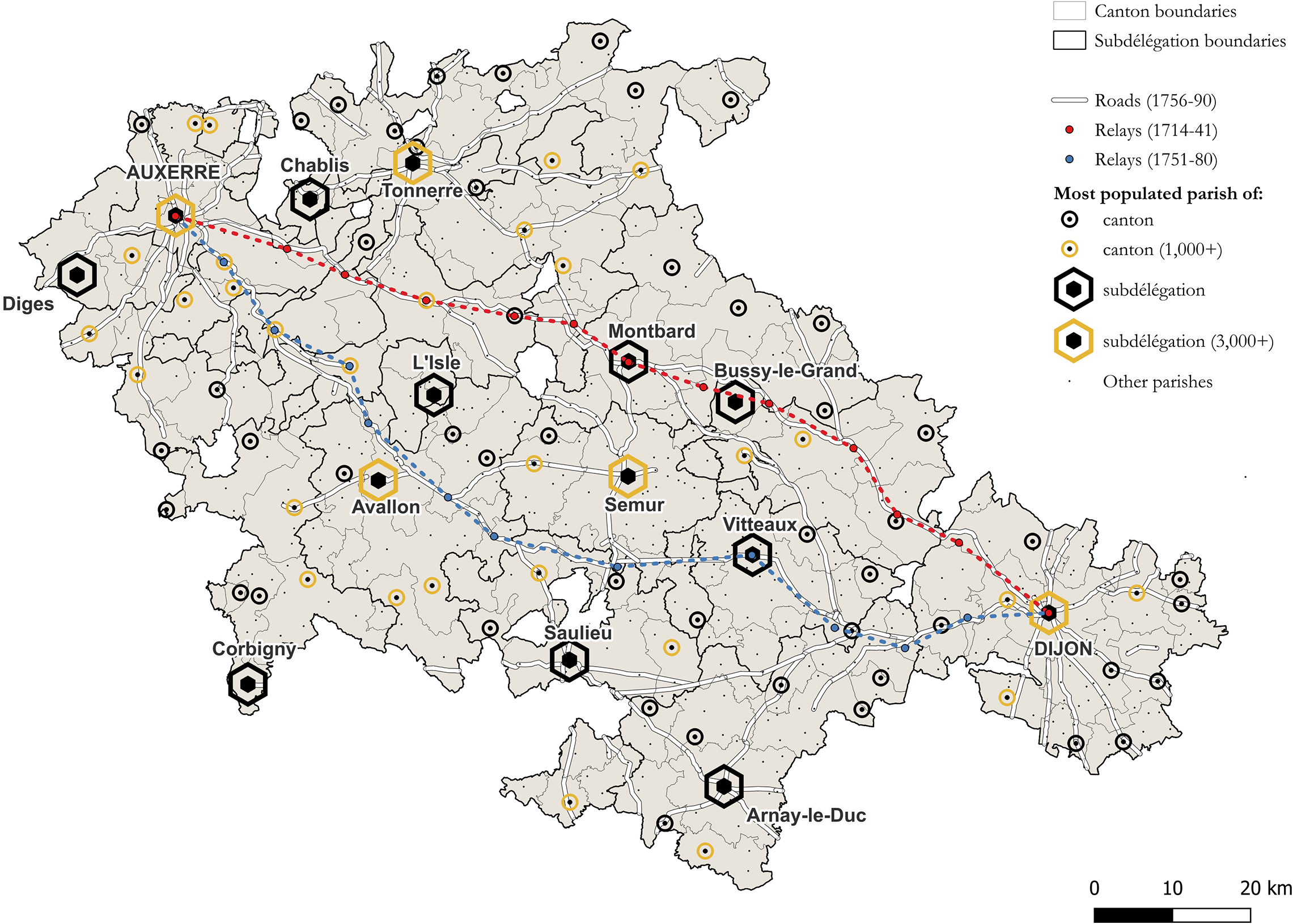

We illustrate this argument in Figure 6, which maps the postal route between Auxerre and Dijon—two regional centers and subdélégation seats in Burgundy that hosted horse-post relays throughout the eighteenth century. Since the early seventeenth century, this route had run northbound along pre-existing roads and waterways via the subdélégation seat of Montbard and eleven additional relays, spaced 11 kilometers apart on average (Nougaret Reference Nougaret1960, 30–2). However, only two of these were located in the most populous parishes of their respective cantons; the remaining nine were located in villages with fewer than five hundred inhabitants. This relay configuration formed a relatively straight route, minimizing the travel distance between the two regional centers. And although the road passed right near the subdélégation seat of Bussy-le-Grand, no relay was ever established there. In 1742, this postal route was rerouted southward through the subdélégation seat of Vitteaux and ten other relays, following road improvements carried out in the early 1730s (Nougaret Reference Nougaret1960, 32, 125–6; Tonnaire Reference Caillou2005, 98–9). As before, relays were spaced 11 kilometers apart on average, and only three of these relays were located in the most populous parishes of their respective cantons; the remaining seven were located in villages with fewer than five hundred inhabitants. This new configuration also formed a relatively straight route, minimizing travel distance between the two regional centers.

Figure 6. The Horse-Post Road from Auxerre to Dijon

Note: This figure displays the postal road from Auxerre to Dijon in Burgundy between 1714 and 1741 (northerly red dashed lines) and between 1751 and 1789 (southerly blue dashed lines). The extent of the map corresponds to the subdélégations (thick boundaries) and cantons (thin boundaries) through which this postal road passed. It also displays the spatial distributions of parishes in the area (marking the most populous ones by canton and subdélégation) and of 1756–90 roads (white lines). Horse-post relay data are based on various editions of the Liste des postes, and 1793 census data, on Cristofoli et al. (Reference Cristofoli, Vouloir, Duménieu and Motte2021). The shapefile of subdélégations is based on information in Cristofoli et al. (Reference Cristofoli, Vouloir, Duménieu and Motte2021), that of cantons, on information in cassini.ehess.fr (Motte and Vouloir Reference Motte and Vouloir2007; Motte et al. Reference Motte, Séguy, Théré and Tixier-Basse2003), and that of roads, on Perret, Gribaudi, and Barthelemy (Reference Perret, Gribaudi and Barthelemy2015).

This example illustrates that while the placement of central nodes of the horse-post relay network was likely endogenous to regional population dynamics, its local configuration between these nodes was plausibly exogenous, as it was designed to minimize travel time along pre-existing roads, subject to the constraint that relays be spaced 10–15 kilometer apart. We therefore exploit local variation in the network through decade-by-administrative division fixed effects. Because this assumption is more credible the finer the scale of analysis, our preferred specification relies on within-canton variation—the average canton contained only two towns with more than a thousand inhabitants in 1793, compared to ten per subdélégation.

This strategy restricts the sampling variation available for identification, as it requires that a canton contains at least two parishes with the same initial treatment status, and that one of them changes treatment status over time. This restriction implies four non-mutually exclusive exclusions from the sample: (i) 201 cantons composed of a single parish; (ii) 3,694 cantons where no parish ever switched treatment—either because none ever hosted a horse-post relay or those that did never lost it; (iii) 105 cantons where only one parish switched treatment and no other parish had the same initial treatment status—typically cantons where a single parish began with a relay, then lost it, while no others ever hosted one; and (iv) 14 cantons where all parishes that ever had a relay followed identical treatment paths. Together, these restrictions remove 3,847 cantons (84% of all cantons) when decade-by-canton fixed effects are introduced. This leaves 732 cantons (out of 1,342 that ever hosted a relay) for identification.Footnote 47

MAIN RESULTS

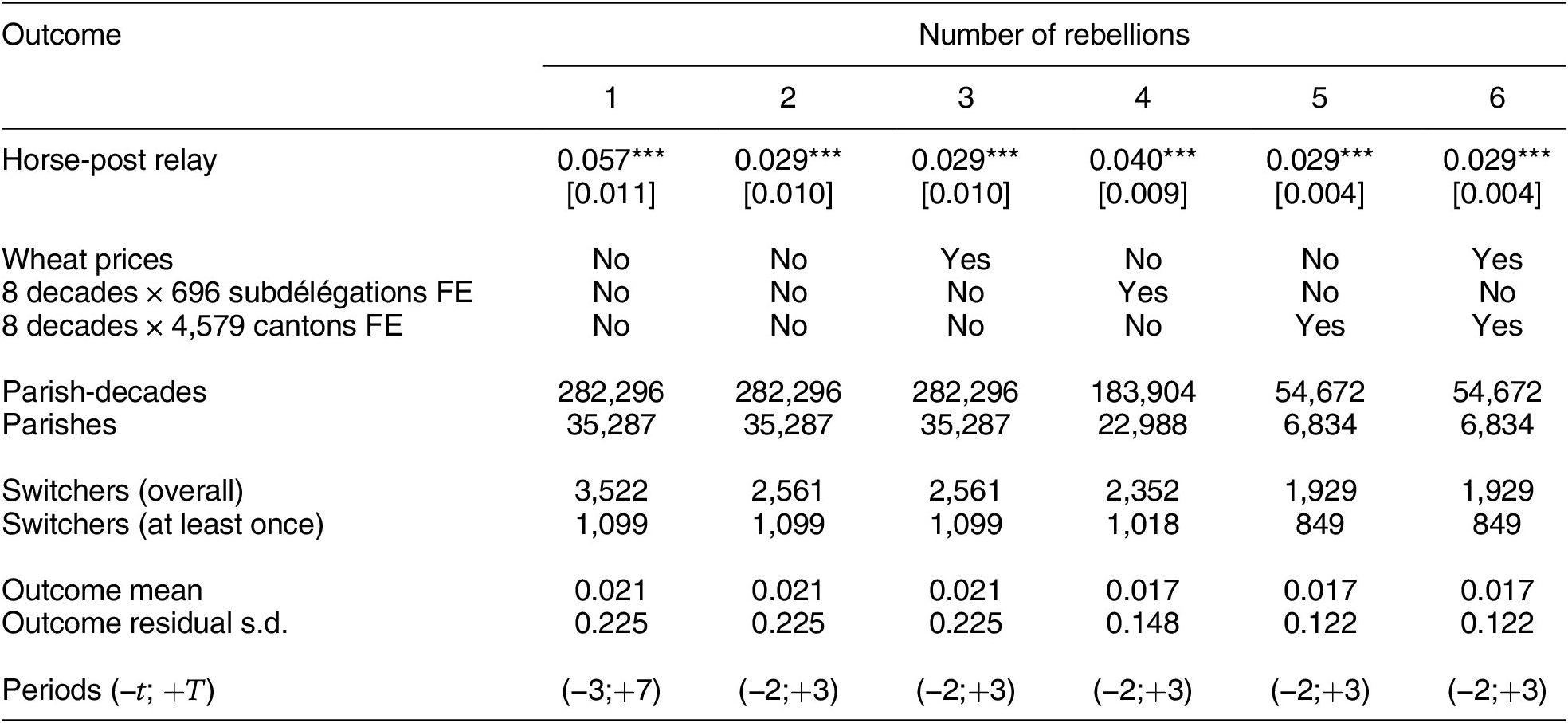

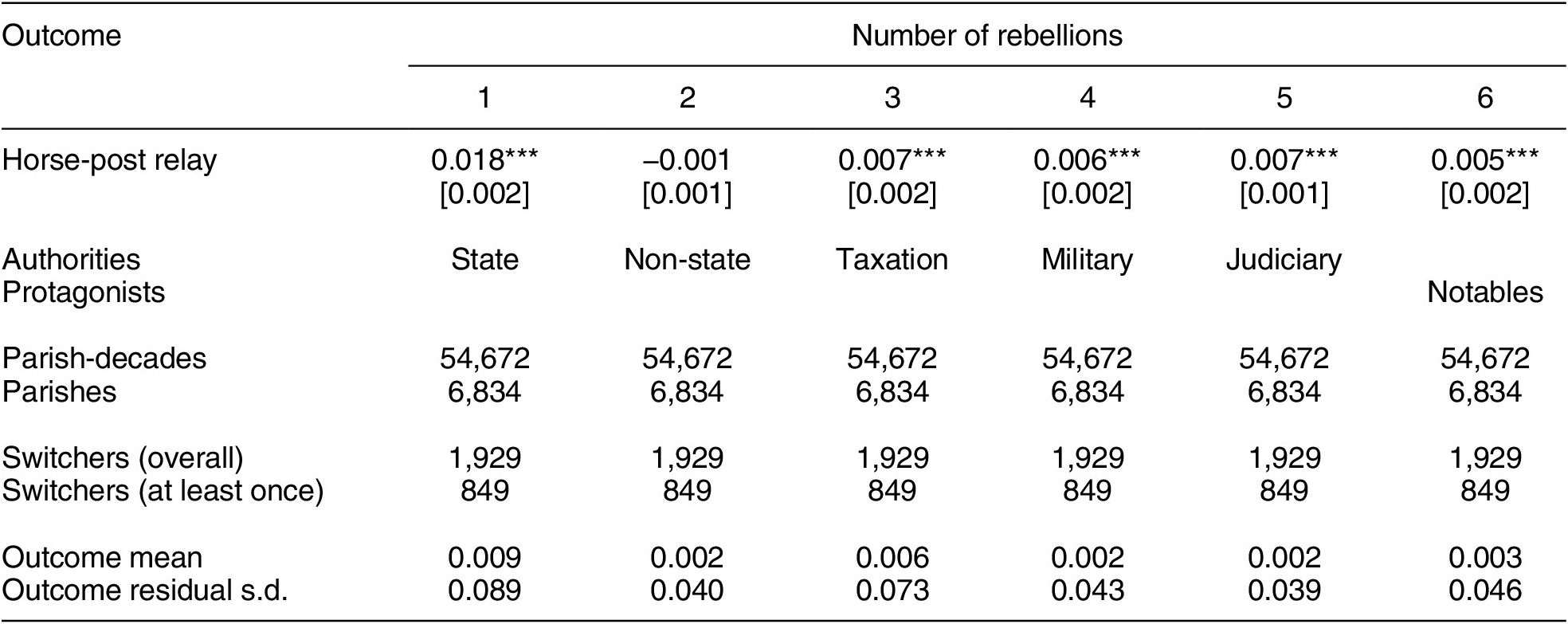

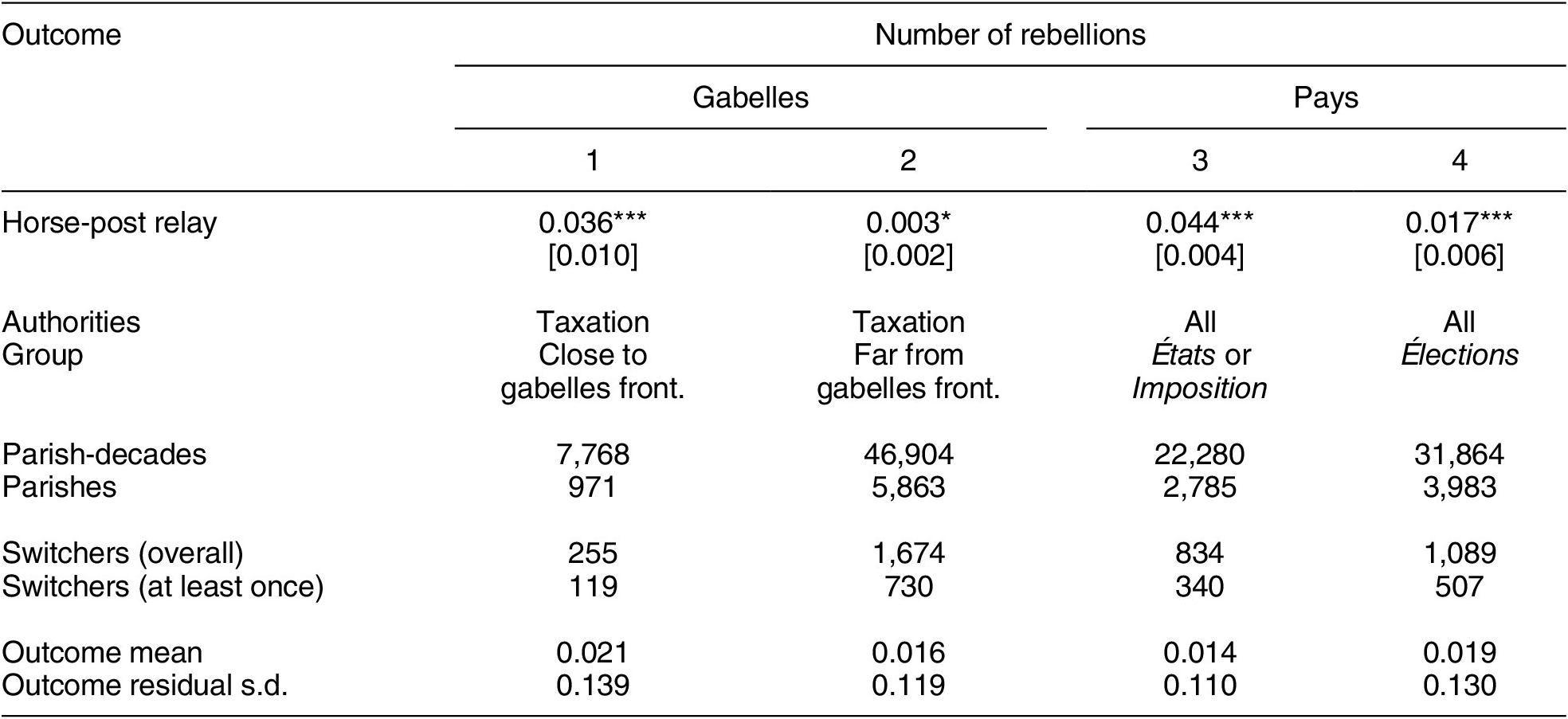

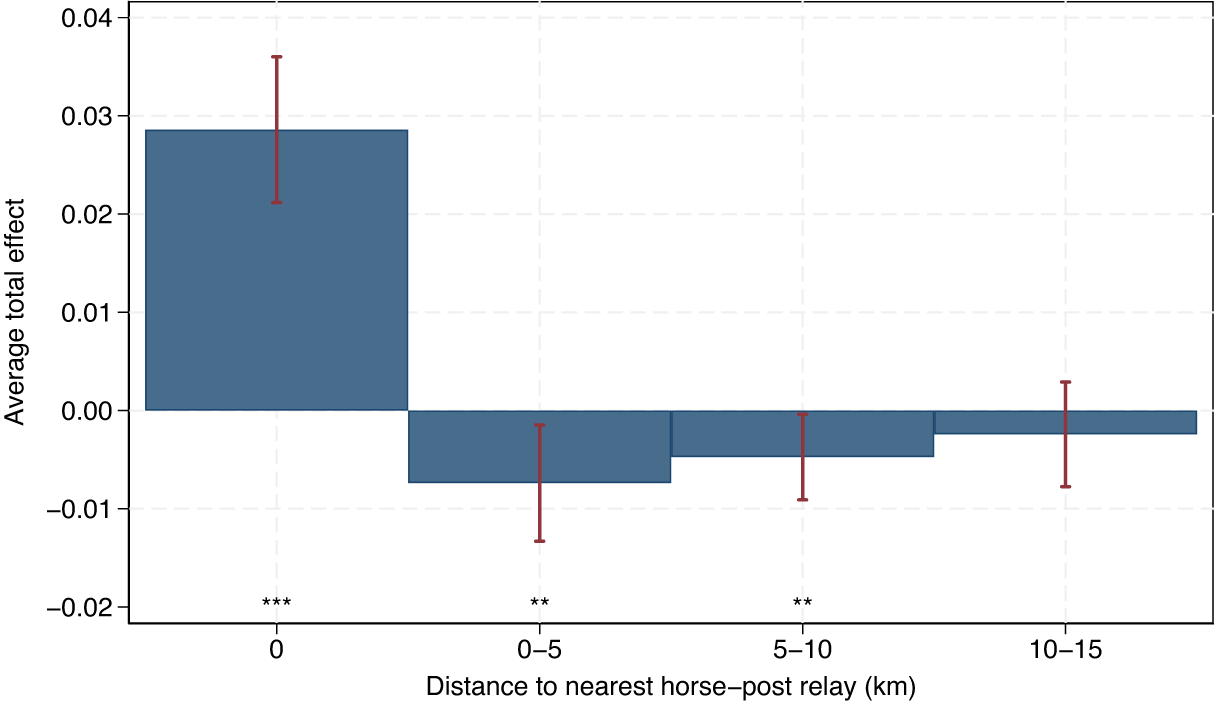

Table 2 reports the main results on the impact of the development of the horse-post relay network on rebellion across eighteenth-century France. Specifically, we report the average total effect of decade-specific event-study estimates

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

, which represents the sum of cumulated period-specific treatments (de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024, 24–5). This table further provides the effective number of parishes-decade and parish observations used for identification, the number of parish-decades that switched treatment, as well as the outcome mean and residual standard deviation calculated on the effective sample.Footnote 48

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

, which represents the sum of cumulated period-specific treatments (de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024, 24–5). This table further provides the effective number of parishes-decade and parish observations used for identification, the number of parish-decades that switched treatment, as well as the outcome mean and residual standard deviation calculated on the effective sample.Footnote 48

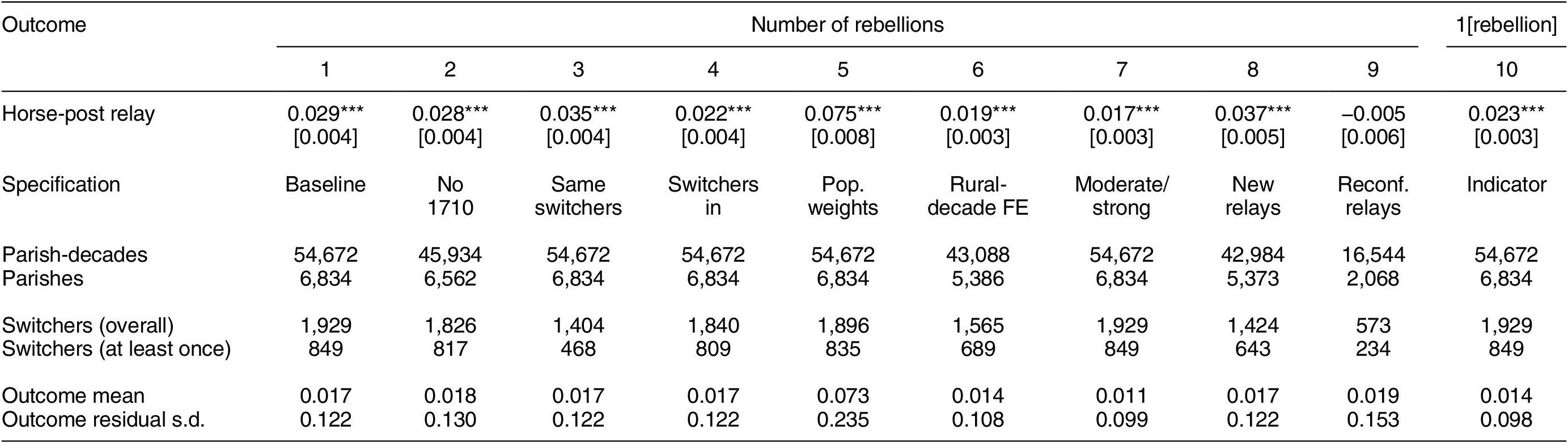

Table 2. Average Total Effect of New Horse-Post Relays on Rebellions

Note: This table reports the average total effect of non-normalized event-study effects

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1. All regressions include parish and decade fixed effects. Parish-decades and Parishes denote the number of observations effectively used in the estimation. Switchers (overall) denotes the number of parish-decade observations that switched treatment over the period, while Switchers (at least once) denotes the number of parishes that switched at least once. Outcome residual s.d. denotes the outcome standard deviation once decade, parish fixed effects, and other controls are accounted for. Summary statistics are calculated relative to the effective sample used in the estimation. Periods (

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1. All regressions include parish and decade fixed effects. Parish-decades and Parishes denote the number of observations effectively used in the estimation. Switchers (overall) denotes the number of parish-decade observations that switched treatment over the period, while Switchers (at least once) denotes the number of parishes that switched at least once. Outcome residual s.d. denotes the outcome standard deviation once decade, parish fixed effects, and other controls are accounted for. Summary statistics are calculated relative to the effective sample used in the estimation. Periods (

![]() $ -t;+T $

) denotes the number of event-study effects and placebos estimated. Estimates are calculated using de Chaisemartin et al.’s (Reference de Chaisemartin, Ciccia, D’Haultfœuille, Knau, Malézieux and Sow2023) did_multiplegt_dyn Stata command. Standard errors are clustered at the parish level and reported in brackets.

$ -t;+T $

) denotes the number of event-study effects and placebos estimated. Estimates are calculated using de Chaisemartin et al.’s (Reference de Chaisemartin, Ciccia, D’Haultfœuille, Knau, Malézieux and Sow2023) did_multiplegt_dyn Stata command. Standard errors are clustered at the parish level and reported in brackets.

![]() $ {}^{***}p\le 0.01.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{**}p\le 0.05.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{*}p\le 0.10 $

.

$ {}^{***}p\le 0.01.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{**}p\le 0.05.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{*}p\le 0.10 $

.

Column 1 reports results from a model without controls estimated using the maximum number of leads and lags allowed by the structure of the data. The establishment of a horse-post relay in a parish was associated with a subsequent increase in rebellion. The average total effect implies an increase in the number of rebellions by 0.057. This represents a little more than twice the average incidence of rebellion and one-quarter of its residual standard deviation. Column 2 restricts the number of periods used in the estimation to two leads and three lags. The coefficient decreases to 0.029 but remains significant at the 1% level and of sizable magnitude, corresponding to the average incidence of rebellion and one-tenth of its residual standard deviation. Column 3 introduces wheat prices as a time-varying control to assess whether local income shocks following the establishment of a relay might account for the results. The estimate remains unchanged, suggesting that the introduction of a relay was unrelated to changing local economic conditions that could have triggered rebellion. This finding aligns with evidence from Tonnaire (Reference Tonnaire2005, 44–62), who concludes on the basis of taille and capitation information that parishes along the postal road between Auxerre and Dijon that received a relay in the 1740s did not become wealthier in subsequent decades. If anything, her evidence points toward distributional effects, consistent with the mechanisms we propose below. Columns 4 and 5 introduce decade-by-administrative division fixed effects to compare parishes over time within the same subdélégation or canton.Footnote 49 Results are consistent with the baseline at 0.029, suggesting limited heterogeneity in treatment effects across administrative divisions. Finally, column 6 further controls for wheat prices. The resulting coefficient of 0.029 is again essentially identical to the baseline in column 2. However, its relative magnitude is about twice as large due to the reduced sampling variation after accounting for the additional controls used in this specification.

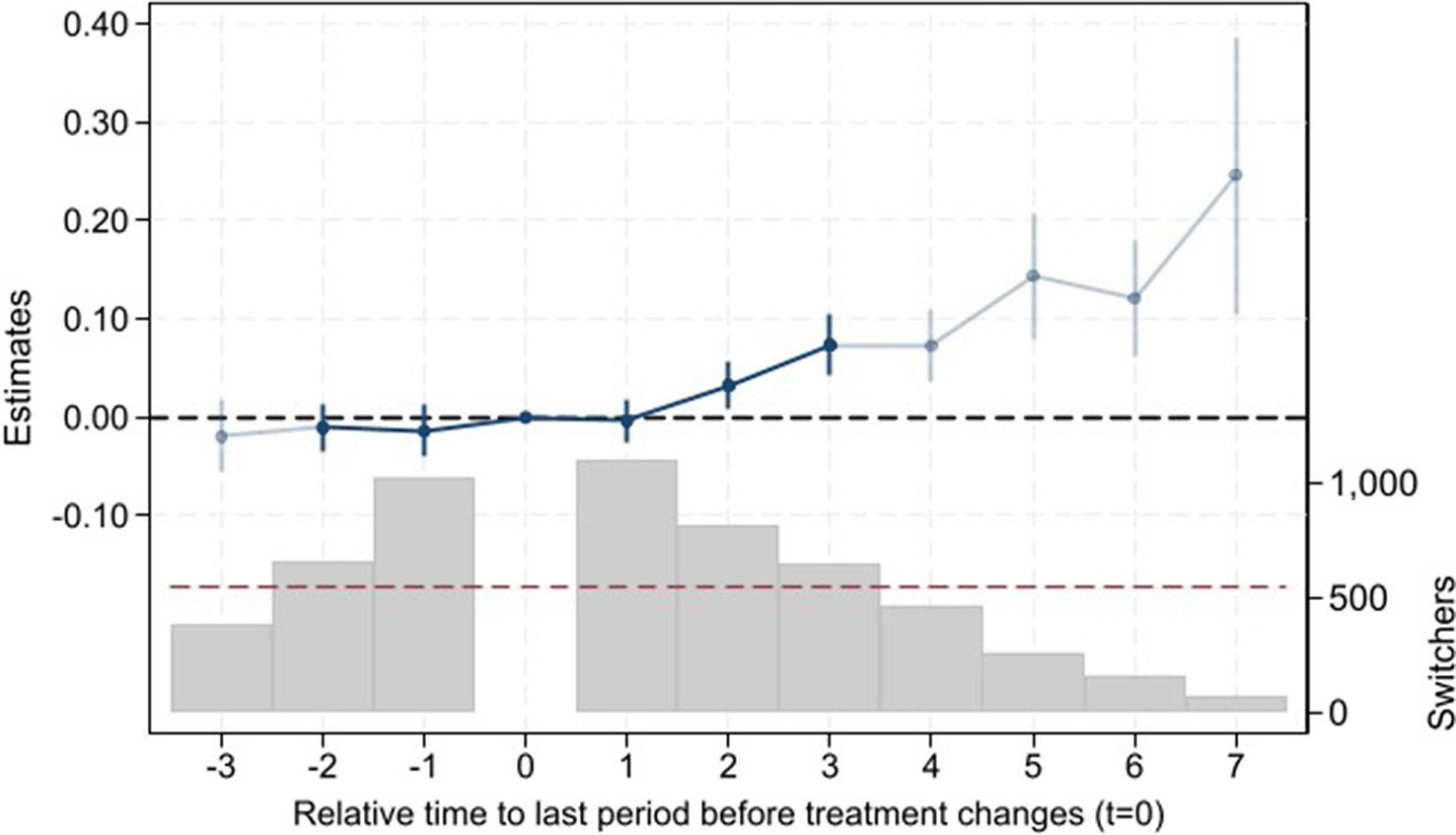

Figure 7. Event-Study Effects of New Horse-Post Relays on Rebellions

Note: The top half of this figure reports event-study effects

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1 along with 95% confidence intervals. The specifications correspond to Columns 1 and 2 in Table 3. Dark blue estimates correspond to restricting the estimation to two leads and three lags, while light blue estimates use the full three leads and seven lags in the estimation. The bottom half of this figure reports the number of switchers used for the identification of each event-study effect. The red dashed line denotes half of first-period switchers. The full set of results is available in Table A5 in the Supplementary Material.

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1 along with 95% confidence intervals. The specifications correspond to Columns 1 and 2 in Table 3. Dark blue estimates correspond to restricting the estimation to two leads and three lags, while light blue estimates use the full three leads and seven lags in the estimation. The bottom half of this figure reports the number of switchers used for the identification of each event-study effect. The red dashed line denotes half of first-period switchers. The full set of results is available in Table A5 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 7 presents an event-study plot that encapsulates the estimates from columns 1 and 2. This figure serves three purposes: first, to assess the plausibility of the parallel-trends assumptions; second, to examine the temporal dynamics of the treatment effect; and third, to display event-study coefficients without restricting the number of leads and lags. Placebo lead estimates show no evidence of differential pre-trends between treated and untreated parishes, supporting the credibility of the parallel-trends assumption. In contrast, post-treatment estimates reveal substantial dynamic treatment effects: rebellions increase in the second decade after a horse-post relay is established and continue to grow thereafter. Additional analyses using sliding decadal intervals in rebellions indicate that the treatment effect begins to materialize generally within the first decade and grows thereafter.Footnote 50 Finally, the figure indicates that the third placebo lead and the fifth, sixth, seventh period estimates rely on a relatively small number of switchers, supporting our choice to emphasize estimates using two leads and three lags. An event-study plot relative to the specification in column 6 of Table 2 leads to similar conclusions.Footnote 51

Robustness

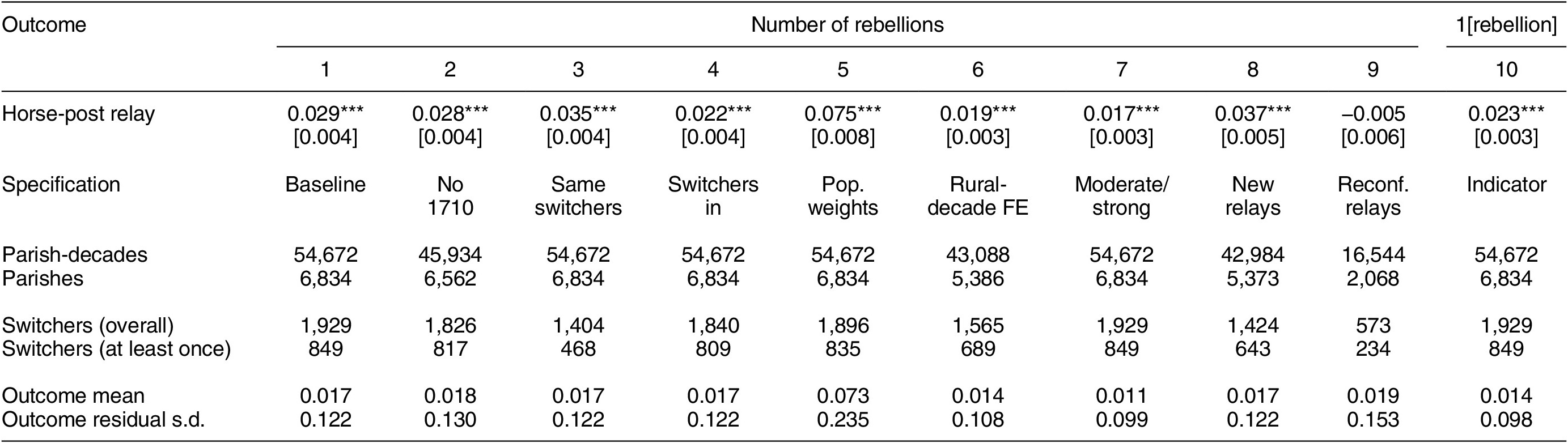

Table 3 assesses the robustness of our main results. These tests build on the full specification reported in column 6 of Table 2—reported here in column 1—which includes controls for wheat prices and decade-by-canton fixed effects.

Periodization

To assess the credibility of the “initial conditions” assumption (de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2024, 9–12), column 2 excludes the 1710 decade from the sample. The resulting estimate of 0.028 remains close to the baseline and is significant at the 1% level, suggesting that this assumption is reasonable.Footnote 52

Sample Composition

Next, we hold constant the sample of switchers used for identification to assess whether changes in the effective sample drive our results. The estimate in Column 3 of 0.035 suggests that they do not. Column 4 further restricts the sample to parishes that switch into treatment—that is, parishes that receive a new horse-post relay—as opposed to using both switchers in and switchers out—that is, parishes that also lose a relay. The estimate declines slightly to 0.022 but remains significant at the 1% level and consistent with the baseline.

Table 3. Robustness

Note: This table reports the average total effect of non-normalized event-study effects

![]() $ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1. All regressions include parish and decade fixed effects, as well as wheat prices and decade-by-canton fixed effects. The estimation is restricted to two leads and three lags. Column 2 removes parish-decades of the 1710s. Column 6 includes an additional set of decade-by-rural status fixed effects. Column 8 restricts horse-post relays to those that are at least 15 kilometers from a retired relay in the same decade, and column 9, to those that are within 15 kilometers, where Reconf. denotes reconfigured relays. The outcome is the number of rebellions in columns 1–9, and an indicator variable for the occurrence of at least one rebellion in column 10. Parish-decades and Parishes denote the number of observations effectively used in the estimation. Switchers (overall) denotes the number of parish-decade observations that switched treatment over the period, while Switchers (at least once) denotes the number of parishes that switched at least once. Outcome residual s.d. denotes the outcome standard deviation once decade, parish, and canton fixed effects, as well as wheat prices are accounted for. Estimates are calculated using de Chaisemartin et al.’s (Reference de Chaisemartin, Ciccia, D’Haultfœuille, Knau, Malézieux and Sow2023) did_multiplegt_dyn Stata command. Standard errors are clustered at the parish level and reported in brackets.

$ {\delta}_{\ell } $

estimated through Equation 1. All regressions include parish and decade fixed effects, as well as wheat prices and decade-by-canton fixed effects. The estimation is restricted to two leads and three lags. Column 2 removes parish-decades of the 1710s. Column 6 includes an additional set of decade-by-rural status fixed effects. Column 8 restricts horse-post relays to those that are at least 15 kilometers from a retired relay in the same decade, and column 9, to those that are within 15 kilometers, where Reconf. denotes reconfigured relays. The outcome is the number of rebellions in columns 1–9, and an indicator variable for the occurrence of at least one rebellion in column 10. Parish-decades and Parishes denote the number of observations effectively used in the estimation. Switchers (overall) denotes the number of parish-decade observations that switched treatment over the period, while Switchers (at least once) denotes the number of parishes that switched at least once. Outcome residual s.d. denotes the outcome standard deviation once decade, parish, and canton fixed effects, as well as wheat prices are accounted for. Estimates are calculated using de Chaisemartin et al.’s (Reference de Chaisemartin, Ciccia, D’Haultfœuille, Knau, Malézieux and Sow2023) did_multiplegt_dyn Stata command. Standard errors are clustered at the parish level and reported in brackets.

![]() $ {}^{***}p\le 0.01.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{**}p\le 0.05.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{*}p\le 0.10 $

.

$ {}^{***}p\le 0.01.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{**}p\le 0.05.\hskip2.21384pt {\hskip2.21384pt }^{*}p\le 0.10 $

.

Heterogeneity

In column 5, we estimate Equation 1 with 1793 population weights to gauge the heterogeneity of treatment effects across parish sizes. We find an effect of 0.075, suggesting that larger parishes may respond more strongly to the introduction of a new relay. However, given the higher weighted outcome mean and residual standard deviation, the magnitude remains comparable to the baseline. Similarly, in column 6, we further include decade-by-rural status fixed effects, where rural status is defined as an indicator variable that equals one if the parish had fewer than two thousand inhabitants in 1793—the threshold used to classify rural communes in nineteenth-century censuses (Le Mée Reference Le Mée1972). We find an estimate of 0.019, again comparable to the baseline. We further investigate the nature of heterogeneous treatment effects along various characteristics in Appendix B of the Supplementary Material, showing that baseline differences in population, administrative status, gabelle taxation regime, historical opposition to the central state, and mode of ruling do not account for our results. We also show that the treatment effect is generally homogeneous across regions and that the results are also robust to excluding one region at a time.Footnote 53

Rebellion Intensity

In column 7, we show that the effect we identify is not driven by small rebellions, as results are similar when focusing on moderate to strong rebellions.Footnote 54

Type of Horse-Post Relays

Columns 8 and 9 explore the nonlinear expansion dynamics of the horse-post relay network by contrasting entirely new relays with those arising from local reconfigurations.Footnote 55 We find that new relays are driving the results, while those stemming from local reconfigurations have no discernible impact on rebellion—likely because they did not meaningfully alter the local presence of the state.

Rebellions Indicator

Column 10 confirms that the results are robust when the outcome is instead specified as an indicator variable that equals one if there was at least one rebellion in a parish-decade.

Archival Reporting Biases

In addition to the robustness tests reported in Table 3, we assess whether our results could be driven by archival gaps or recording biases Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) rebellion data. For instance, information for some départements is mostly drawn from national archives, which are generally less comprehensive than departmental archives. This could introduce biases in the representativeness of rebellious events across départements. Reassuringly, our empirical strategy mitigates this potential source of bias by leveraging variation in rebellious activity within the reach of departmental archives through the use of decade-by-canton fixed effects.

But other forms of selection bias could affect our results. One concern is that the expansion of the horse-post relay network may have enhanced the state’s ability to record rebellions. However, monitoring rebellions was not part of the horse post’s surveillance function, which was primarily to control individuals passing through relays (Marchand Reference Marchand2006, 210–4). Moreover, spatial patterns presented below show no evidence of over-recording in areas surrounding relays beyond host parishes themselves. Furthermore, archives of the horse post are not among the sources of the Jean Nicolas survey, as a major flood in 1910 and destruction during the Second World War damaged much of the archives of Ancien Régime postal institutions (Krakovitch et al. Reference Krakovitch, Lalguë-Guilhemsans, Roquincourt and Vaille2000, 2). Surviving records were deposited in the National Archives in 1998, and were therefore largely inaccessible at the time the survey was conducted.Footnote 56 Instead, the main actors monitoring and punishing rebellious activity were the maréchaussée and the judiciary, much as the police and the courts today. The main sources of information on rebellion thus come from the archives of these institutions, which are well preserved and were extensively surveyed by Jean Nicolas and his collaborators (Gay Reference Gay2025, 27–8).

Alternatively, the introduction of a horse-post relay may have increased the recording of rebellions by other local actors. To assess this possibility, we reproduce our analysis using only rebellions recorded by state-level authorities and preserved in national archives, finding that the results remain robust.Footnote 57 We further sequentially exclude rebellions recorded by the most frequent reporting institutions: the central government, the central financial administration, the maréchaussée, local courts and justices, and provincial administrations. Results are again consistent with the baseline, suggesting little selection bias arising from Nicolas’s (Reference Nicolas2002) archival sources.

Additional Robustness Tests