Introduction

Parents report that around 20% of infants in western countries cry a lot without an apparent reason during the first four months of age (Alvarez, Reference Alvarez2004; Douglas and Hill, Reference Douglas and Hill2011; Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Bilgin and Samara2017). Until recently, this crying was widely attributed to gastro-intestinal disorder and pain and known as ‘infant colic’ (Illingworth, Reference Illingworth1954; Wessel et al., Reference Wessel, Cobb, Jackson, Harris and Detwiler1954). However, evidence has accumulated that most such infants are healthy and grow and develop normally (Stifter and Braungart, Reference Stifter, Anzman-Frasca, Birch and Voegtline1992; Lehtonen, Reference Lehtonen2001), that many normal infants have a crying ‘peak’ in the first three months of age (Barr, Reference Barr1990; St James-Roberts and Halil, Reference St James-Roberts and Halil1991; Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Bilgin and Samara2017), and that this crying peak and the ‘unsoothable’ crying bouts which alarm parents usually resolve spontaneously by five months of age (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Rotman, Vamengo, Leduc and Francoeur2005). This has led some reviews to conclude that the crying is usually due to normal developmental processes (Barr and Gunnar, Reference Barr and Gunnar2000; St James-Roberts et al., Reference St James-Roberts, Alvarez and Hovish2013).

Alongside these findings, the term ‘infant colic’ has been criticised for failing to distinguish adequately between ‘prolonged’ infant crying (a measure of crying duration) and a parent’s evaluation that their baby is crying too much and may be a sign that something is wrong with this baby (‘excessive infant crying’) (St James-Roberts, Reference St James-Roberts2012). Although related, there is growing awareness that ‘prolonged’ and ‘excessive’ crying need to be distinguished, so that research into the crying is matched by an equal focus on its impact on parents (Zeifman and St James-Roberts, Reference Zeifman and St James-Roberts2017). There is evidence, for instance, that crying judged to be excessive can trigger premature termination of breastfeeding (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Lanphear, Lanphear, Eberly and Lawrence2006), over-feeding (Stifter et al., Reference Stifter and Braungart2011), parental distress and depression (Murray and Cooper, Reference Murray and Cooper2001; Kurth et al., Reference Kurth, Kennedy, Spichiger and Stutz2011), poor parent–child relationships (Papouŝek et al., Reference Papouŝek, Wurmser and von Hofacker2001), problems with long-term child development (Schmid and Wolke, Reference Schmid and Wolke2014; Smarius et al., Reference Smarius, Strieder, Loomans, Doreleijers, Vrijkotte, Gemke and van Eisden2017) and infant abuse in a small number of cases (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Trent and Cross2006). Yet, there are no routine, tried and tested, UK health services for supporting parents in managing infant crying. Instead, parents turn to popular books, magazines or websites, which give conflicting advice (Catherine et al., Reference Catherine, Ko and Barr2008), or take babies to clinicians or hospital Accident & Emergency departments, although only around 5% of such infants have an organic disturbance (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Al-Harthy and Thull-Freedman2009).

By involving parents in the development of evidence-based materials they consider fit for purpose, this study aimed to take the first steps towards the provision of health care services which improve the well-being of parents whose babies cry excessively, their infants’ outcomes, and how UK National Health Service (NHS) money is spent.

Methods

Governance

Study public registration no. ISRCTN84975637; ethical approval provided by De Montfort University (ref. 13450) and the NHS (IRAS project ID 152836); Research & Development approval by Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust (LPT). The study was regulated by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-appointed Steering Committee and coordinated by a Management Group, including the research team, Senior LPT Health Visitors (HVs), a paediatrician, General Practitioner, health economist, members of Leicester Clinical Trials Unit and National Childbirth Trust (NCT), Cry-Sis and parent representatives.

Literature review

To identify evidence-based interventions to support parents who are concerned about their infant’s excessive crying, a literature review was conducted updating an existing systematic review of this material (Douglas and Hill, Reference Douglas and Hill2011). The search strategies used are described in Appendix 1. Inclusion criteria were: the existence of the intervention materials in a published and exportable form; a cost which allowed potential adoption of the materials within the NHS; availability of at least provisional evidence of effectiveness.

Although excessive infant crying is often considered to be a paediatric condition, it can also be viewed as a stressor which may impact on adult well-being and mental health (Murray and Cooper, Reference Murray and Cooper2001; Kurth et al., Reference Kurth, Kennedy, Spichiger and Stutz2011). The degree of impact is partly due to how parents cope with it, which is affected by underlying parental vulnerabilities, circumstances and resources (Laurent and Ablow, Reference Laurent and Ablow2012; Smarius et al., Reference Smarius, Strieder, Loomans, Doreleijers, Vrijkotte, Gemke and van Eisden2016). To recognise this, the literature review was also used to search for evidence of interventions that were effective in supporting parental and adult coping and mental health, particularly in the postpartum period.

Recruiting parents

In the United Kingdom, HVs provide universal primary care for parents with young babies and are the obvious choice for delivering the intended service within the NHS. With support from LPT managers collaborating in the study, HVs in five HV areas were invited to briefings about the study and to take part. In total, 55 HVs gave written informed consent to collaborate with the study by referring parents who had been distressed by their baby’s excessive crying to the research team. To widen recruitment, flyers were distributed via local NCT networks, children’s centres, HV bases and parenting/baby groups to inform parents about the study.

Following initial contact, researchers explained the study to parents and sought their written informed consent to take part. Full eligibility criteria for parents were:

∙ Living in the LPT area;

∙ Previously having a healthy baby whose excessive crying in the first six months had caused concern for either parent;

∙ Their baby was no longer crying excessively;

∙ English speaking or supported by an English speaker.

Although translation into other languages was desirable, this was costly and local HV experience was that most non-English speaking parents were accompanied by English speaking family members or friends.

Focus groups and interviews with the parents

The recruited parents were asked to take part in a focus group, held in a local venue at a time convenient for parents. They were invited to bring their babies or children with them. Four focus groups, lasting 2–3 h and ranging in size from 2 to 5 parents, were held. Since mutually convenient times could not always be found, six parents were interviewed individually following the same format. In total, 20 parents (18 mothers; two fathers) took part. Two researchers experienced in focus group and interview methods facilitated each session, whilst two others made observational notes and provided informal child care. Sessions were audio-recorded for later verbatim transcription. Themes emerging from these qualitative data are reported elsewhere (Garratt et al., Reference Garratt, Powell, Bamber, Long, Dyson and Brown2017).

Each focus group followed a planned structure, with two main parts. First, facilitators explained the group aims and procedures and participants introduced themselves, using pseudonyms if they wished to maintain anonymity. Parents were asked to describe their experience of having a baby who cried excessively, what was most challenging, who provided help, what was most helpful, what else might have helped, what sorts of supports they would have liked to have received at the time, and what routine services should include. They were asked what they considered the most suitable delivery method (website, leaflet, direct contact with a professional, telephone contact) and what devices they would prefer to use to access online information and support (computer, tablet, telephone).

In part two, materials from the four example support packages identified by the literature review were evaluated by the parents. All four packages included a website together, in some cases, with supplementary video or written materials. Sample materials from each package were shown to parents, with a changed presentation order for each session to reduce order effects. Appendix 1 gives more details. After each example, each parent was asked to give detailed feedback using five, 5-point rating scales:

(1) How attractive the materials were (very attractive – very unattractive);

(2) How clear was the information provided (very clear – very unclear);

(3) How helpful was the information provided (very helpful – very unhelpful);

(4) How much they liked each of 10 researcher-nominated features of the package (really liked – did not like);

(5) How important it was to include materials like these as part of NHS care (very important – not at all important).

In addition, parents were invited to make written comments on other features they felt were important, disliked or could be improved.

Parents were asked to re-visit the four example support package websites after the focus group sessions. Follow-up telephone calls were used to confirm whether they had done so and whether this more extensive exposure had changed their opinions and ratings. Based on feedback from the focus groups, the follow-up contacts were also used to invite parents to contribute further to the package by consenting to the inclusion of their quotes from the focus group transcripts, written experiences and/or video presentations of their story, in the study materials. To recognise parents’ contributions to the research, they were given £50 shopping vouchers on completing the focus groups and when they gave feedback on the developed package.

Results

Literature review

Appendix 1 provides a detailed description of the literature review process. Four example packages which met the study criteria, were identified:

http://www.copingwithcrying.org.uk

http://raisingchildren.net.au/articles/cry_baby_program.html/context/255

Contracts with the organisations involved were arranged to allow these materials to be included in the study focus groups. A Rhode Island USA programme which requires a multi-professional clinic was excluded because it is costly and difficult to export (Twomey et al., Reference Twomey, High and Lester2012).

The literature review also found that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)-based interventions are effective in helping adults, including parents in the postpartum period, to cope with stressful conditions and moderate psychological distress (Morell et al., Reference Morell, Slade, Warner, Paley, Dixon, Walters, Brugha, Barkham, Parry and Nicholl2009; Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013; Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Sikander, Atif, Singh, Fuhr, Rahman and Patel2014; Stein et al., 2014). Use of programmes of this type for this purpose is recommended by the UK National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE, 2009, 2014).

Focus group data

Table 1 presents demographic figures for the participating parents and their babies. Most were contacted by HVs, but five were recruited via NCT networks, flyers or other parents. Two of the 20 parents were fathers participating with female partners, but only one father provided demographic data (see Table 1 footnote). Most parents had experienced just one excessively crying baby but one mother had experienced two and described both, giving data for 19 babies in all.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of focus group parents and their babies

a Both dads provided data, but only one provided demographic information. He was white British, 42 years old with a postgraduate degree qualification.

As Table 1 shows, most mothers were white British (73%), had an undergraduate or postgraduate degree (61%) and were married or living with a partner (83%) at the time when their baby cried excessively. The mothers’ average age was 30.4 years, ranging from 19 to 41 years. Nearly half of the babies were second or third-born, with 8 of the 18 families having other children who had not cried excessively. The babies were equally likely to be boys or girls, and they were almost equally divided between breast, formula or mixed feeding when the crying started. None had a fever and only two seemed unwell. Although 58% of their mothers reported that their baby had problems with feeding, all the babies had been checked by clinicians for weight gain and 89% for feeding problems, without any specific problem being confirmed.

Typically, the babies’ excessive crying started at around 1 week and stopped by 5 months of age. However, the variability in how long the crying lasted was substantial, ranging from 4 to 100 weeks.

Table 2 summarises the 20 parents’ reports about sources of information and support. During the period when their baby was crying excessively, 89% of parents visited a HV, doctor or other health professional, 50% spoke with a health professional over the telephone, and 89% considered these to be effective sources. Websites were similarly popular, being consulted by 80% of parents, valued by all 20 parents, and considered an effective way to communicate information by 89%. Most parents (78%) preferred to access online information through their mobile phone, 44% via tablets (some preferred these equally). Most considered leaflets to be helpful (72%) and effective in communicating information (76%), but just 45% had used them during the period when their baby was crying excessively. All parents considered that groups to meet other parents with excessively crying babies would offer a valuable additional source of information and support.

Table 2 Sources of information and support

HV=health visitor.

a Two parents did not provide this information. Parents could use or prefer more than one device.

All four example support packages shown to parents in the focus groups were rated attractive or very attractive, clear or very clear and helpful or very helpful by the majority (range 11–20) of parents. All 20 parents reported it was important that materials like these should be included as part of routine NHS care. Because our aim was to identify which features parents judged to be needed in future materials (not to compare existing examples). Tables 3 and 4 summarise the features parents liked in at least one website. All 10 researcher-nominated features were liked or really liked. Features parents added in their written comments (Table 4) included accessible, relevant information; practical advice; an attractive, easy to use format; and offering reassurance to parents about their baby’s crying.

Table 3 Parents’ ratings of researcher-nominated features of the four sample websites (n=20)

Table 4 Features parents added in their written comments (n=20)

Twelve of the 20 parents were successfully re-contacted after the focus groups. Eight had revisited one or more of the example websites. None wished to amend the responses given within the focus groups.

Production of a set of parental support materials

Reflecting the literature review and focus group data, three package elements were developed: a Surviving Crying website; a printed version of the website materials; and a programme of CBT-based support sessions delivered directly to parents by a qualified practitioner.

A commercial marketing and communications agency was appointed to assist in developing the website materials. Their brief included preparing templates for the website design and layout, incorporating text, pictures and video materials prepared by the study team, setting up and testing the website for compatibility with different devices and operating systems, hosting and maintaining the website and setting up Google Analytics to allow figures for website access by parents, HVs and visitors to be obtained.

The website materials were uploaded by the study team, using an iterative process of drafting and revision, taking account of the focus group findings. Care was taken to ensure that all advice was evidence-based and a section listing sources was included. The text was adjusted to a reading age of 9–12 years. With parents’ permission, three videos of parents speaking about their experiences and five written stories were uploaded onto the website with names changed to maintain anonymity, together with three videos of professionals providing information and guidance.

The draft website materials were shown or sent to the 20 focus group parents for review (16 provided feedback) and were circulated to HVs for approval, checked for clinical accuracy by the study paediatrician, and revised as necessary. Figure 1 shows the home page of the resulting Surviving Crying website as it appears on phone, tablet, laptop and desktop computer screens. The website remains copyright and requires a login and password.

Figure 1 The Surviving Crying home page as it appears on various devices

Following the website design and content so far as possible, a printed version of the materials was prepared as a booklet.

Based on prior CBT studies (NICE, 2009, 2014; Tandon et al., Reference Tandon, Perry, Mendelson, Kemp and Leis2011; Alexander, Reference Alexander2013) and the longitudinal course of infant crying, a programme of practitioner CBT support was designed to include up to five sessions, each lasting 60–90 min, delivered to parents in person or by telephone within a 4–6-week period. The sessions could be delivered at home or in a local centre, according to parents’ wishes. Depending on the availability of other parents, parents could choose whether to take part in one-to-one or small-group sessions.

Three key topics were included in each practitioner-delivered session:

∙ Assessing infant crying and well-being, making arrangements to obtain any other information or support needed, and providing parents with information and reassurance.

∙ Monitoring the soothing and baby-care methods parents were using.

∙ Supporting parents in developing coping strategies which helped them to manage their own emotions and actions and enhance their well-being.

A practitioner manual for delivering the CBT programme was prepared by the study team in collaboration with a CBT-qualified counselling psychologist with extensive experience in supporting adult mental health in the NHS. The manual underwent iterative revisions, was piloted, and then checked by parent and HV members of the Study Management Group. The adopted version included practitioner guidance and record sheets as well as materials for parents.

Safeguarding procedures

Together with the LPT safeguarding officers, clinical staff and the study paediatrician, the study team developed safeguarding protocols to ensure the safety of parents and babies involved in the study.

Methods for evaluating the package materials

Measures of participation and cost, questionnaires assessing infant crying, feeding and health, parental well-being and crying knowledge, together with rating scales to evaluate each element of the support package, were developed. To avoid duplication, these methods will be described together with the evaluation findings when available.

Discussion

Stage 1 of the Surviving Crying study, reported here, was designed to develop a new, evidence-based, package of materials to support parents who are concerned about their baby’s excessive crying. The term ‘excessive infant crying’ refers to a parent’s evaluation that their baby is crying too much and may be a sign that something is wrong with this baby, as opposed to ‘prolonged crying’ which implies a measure of crying duration.

Based on a literature review, four example support packages met study criteria and were selected for inclusion in the study. The review also showed that CBT-based interventions are effective in helping adults, including parents in the postpartum period, to cope with stressful conditions and moderate psychological distress, anxiety and depression.

In total, 20 parents whose babies had cried excessively in the first six months of infancy took part in focus groups or interviews designed to obtain information about the sorts of parental supports needed and to evaluate the example support packages. This small number of parents and their demographic characteristics – they were predominantly white, well-educated and living with partners in stable relationships, while only two were fathers – are limitations of the study which need to be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Inclusion of larger and more culturally diverse groups in future studies will indicate whether the findings apply to different communities and identify any improvements to the support package which need to be made.

Several findings were, however, highly consistent across the parents who participated. First, they had used and rated two sources of support – direct contact with a health service professional and a website providing information and guidance – very highly. Other sources, including telephone contacts and online discussion forums, were valued by around half or more parents. Notably, a large majority of parents wished to access the online material on their mobile phones. Leaflets, arguably the most common source of information in the NHS, were considered valuable by most parents, but fewer had used them when their baby was crying excessively. All 20 participants identified the need for groups to meet other parents as a source of information and support.

The parents’ evaluations of the four example support packages provided evidence about features the parents liked and did not like. Features they liked or very much liked included providing clear and relevant practical information and guidance, reassurance, trustworthiness, that information was aimed at both parents, and the use of videos. Other parents’ experiences and ideas, and expert advice, were also highly valued.

As well as a Surviving Crying website and printed version, a programme of CBT-based sessions for direct delivery to parents by a qualified professional was developed, together with a manual for delivering the programme. In addition to monitoring infant crying, baby-care and soothing strategies, the programme aimed to support parents in developing coping strategies which manage their own emotions and actions and enhance their well-being.

The study focused on parents, but some parental report data about their baby’s crying were collected. The onset age for their crying (median 1 week) and age at which it stopped (median 19 weeks) are broadly in line with previous studies and the evidence that infant crying peaks in the first few months of age (Barr, Reference Barr1990; St James-Roberts, Reference St James-Roberts2012; Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Bilgin and Samara2017). However, variability between infants in the age at which the crying stopped (range 8.5–104 weeks), and how long the crying lasted (range 4–100 weeks) was substantial. Although accuracy varies, studies have found moderate to good agreement between parental reports and objective measures of infant crying (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Kramer, Boisjoly, Mcvey-White and Pless1988; Reference Barr, Paterson, Macmartin, Lehtonen and Young1992; St James-Roberts et al., Reference St. James-Roberts, Hurry and Bowyer1993; Reference St James-Roberts, Conroy and Wilsher1996). Furthermore, although most babies reported to cry excessively have normal outcomes, those reported to do so beyond four months of age are at risk for long-term developmental and behavioural problems (Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Rizzo and Woods2002; Schmid and Wolke, Reference Schmid and Wolke2014). These findings emphasise the need for NHS services which provide parents, particularly in vulnerable circumstances, with information and support.

In keeping with previous research, too, the majority of parents (58%) reported that their baby had feeding problems (Catherine et al., Reference Catherine, Ko and Barr2008). However, almost all (89%) infants had been checked for feeding difficulties, and all had been checked for weight gain, by a health professional, without confirming these as a problem. At the time of crying, just two of the 19 infants were judged unwell and one to be failing to gain enough weight. Although some researchers link unsettled behaviour in early infancy to feeding difficulties (Douglas and Hill, Reference Douglas and Hill2011), the evidence remains unclear and is likely to remain so until tests capable of distinguishing feeding, digestive and other organic causes are developed (Sung and St James-Roberts, Reference Sung and St James-Roberts2017).

Taken altogether, these findings identify an unmet need in UK National Health Services and provide evidence of the sorts of services parents would like to have available. Stage two of the study, involving a preliminary evaluation of whether the Surviving Crying materials are cost-effective and suitable for this purpose, is underway.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the families who participated, the NIHR HTA Programme for its support, the staff of Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust (LPT) for their assistance, and our Steering Committee and Management Group for their guidance. In particular, the study could not have taken place without the help of the following LPT staff: Nicy Turney, FiHV, Professional Lead Health Visiting, Families Young People and Children Services; Joanne Chessman, Clinical Team Leader; Gail Melvin, Research Manager; Joanna McGarr, Trainee Research Assistant; Lynn Hartwell, Research Nurse; the many HVs who took part. Consider Creative provided expert professional assistance in the development of the Surviving Crying website. The authors also thank other UK collaborators: Dr Elaine Boyle, University of Leicester; Charlie Owen, University College London; Sally Rudge, Counselling Psychologist & CBT Practitioner; Rachel Plachcinski, National Childbirth Trust; Jan and John Bullen, Cry-Sis. Four university or charity research groups gave permission to evaluate their parental support materials during the study and the authors are grateful to them and their institutions for this support: Ron and Marilyn Barr for the PURPLE Crying Programme; Harriet Hiscock and Fallon Cook of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute for Cry Baby; Jane Fisher and Heather Rowe, Monash University, for What Were We Thinking; Denise Coster and Peter Richards of the National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children, for Coping with Crying.

De Montfort University acknowledges the support of the National Institute of Health Research Clinical Research Network.

Disclaimer

This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, the HTA Programme or the Department of Health.

Financial Support

This research was funded by Grant no. 12-150-04 from the National Institute for Health Research HTA Programme.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Appendix 1: Literature review strategy

Aims

As part of the process of developing the intervention for this study, a focused literature review was undertaken with two aims:

∙ to identify recent evidence of existing interventions to support parents of babies considered to be crying excessively;

∙ to select a number of these interventions to show to parents attending focus groups in order to gain their feedback.

Strategy

The review was designed to update Douglas and Hill’s (Reference Douglas and Hill2011) systematic review concerning the causes of, and interventions to manage, term infants who cry excessively in the first few months of age. For the purposes of this review, ‘excessive crying’ was taken to mean any crying behaviour that parents considered problematic. Whilst a full systematic review could not be undertaken within the project’s resources, all relevant research needed to be considered. A review strategy was drawn up based on Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework for a scoping study.

The review question was identified as: What support is available to parents with an excessively crying baby who is six months or under and who is otherwise well?

Eligibility criteria

Population

Parents of excessively crying babies up to six months, where no medical reason for the crying had been identified. Based on the evidence that the term ‘colic’ is often applied to unsoothable crying, babies described as having colic were included.

Parents of babies over six months were excluded to rule out sleep problems and other issues that arise at older ages. Premature babies or those medically diagnosed as unwell were also excluded as constituting a different population with a given reason for the crying, and potentially different needs. Medically diagnosed feeding problems were excluded for similar reasons.

Interventions for parents with diagnosed physical or mental health problems were excluded, apart from those experiencing postnatal depression or anxiety, these conditions having a known association with excessive infant crying.

Intervention

All primary studies which had evaluated relevant interventions, using either qualitative or quantitative methods, were included.

Studies investigating the use of relevant measures of crying but not an intervention were excluded. Protocols for trials of interventions were excluded, as these did not evaluate the intervention concerned.

Methodological quality

Methodological quality of studies was not assessed, as the aim of the review was to identify the range of published material.

Publication type/status

All relevant studies, regardless of publication status were included.

Due to time limitations, articles not available in English were excluded. Literature published before June 2011 was excluded to avoid duplication of the evidence already reviewed by Douglas and Hill (Reference Douglas and Hill2011). However, we included an intervention programme evaluated in Fisher et al. (Reference Fisher, Wynter and Rowe2010) which met our criteria but was omitted by Douglas and Hill (Reference Douglas and Hill2011).

Search strategy

During early December 2014, the following databases were searched: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and DARE. In addition, grey literature was searched via the OpenGrey database.

Search terms were identified pertaining to four key aspects of the review question: babies/infants; parents; crying/distress; and parental distress, support and coping. These terms were applied to each database, with a slightly modified search process in OpenGrey due the database’s limitations.

Selection

Retrieved references were reviewed in a number of stages. First, all titles were evaluated against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two team members, with titles being included for further review where at least one team member considered them relevant. In the second stage, abstracts for all included references were obtained where possible, and these were then reviewed by two team members. Where abstracts could not be obtained, a decision regarding inclusion was made on the basis of available information. Finally, the full text of the remaining papers was obtained where possible, and these were then evaluated by two researchers as before. Disagreements were resolved by a third team member at all stages.

Results

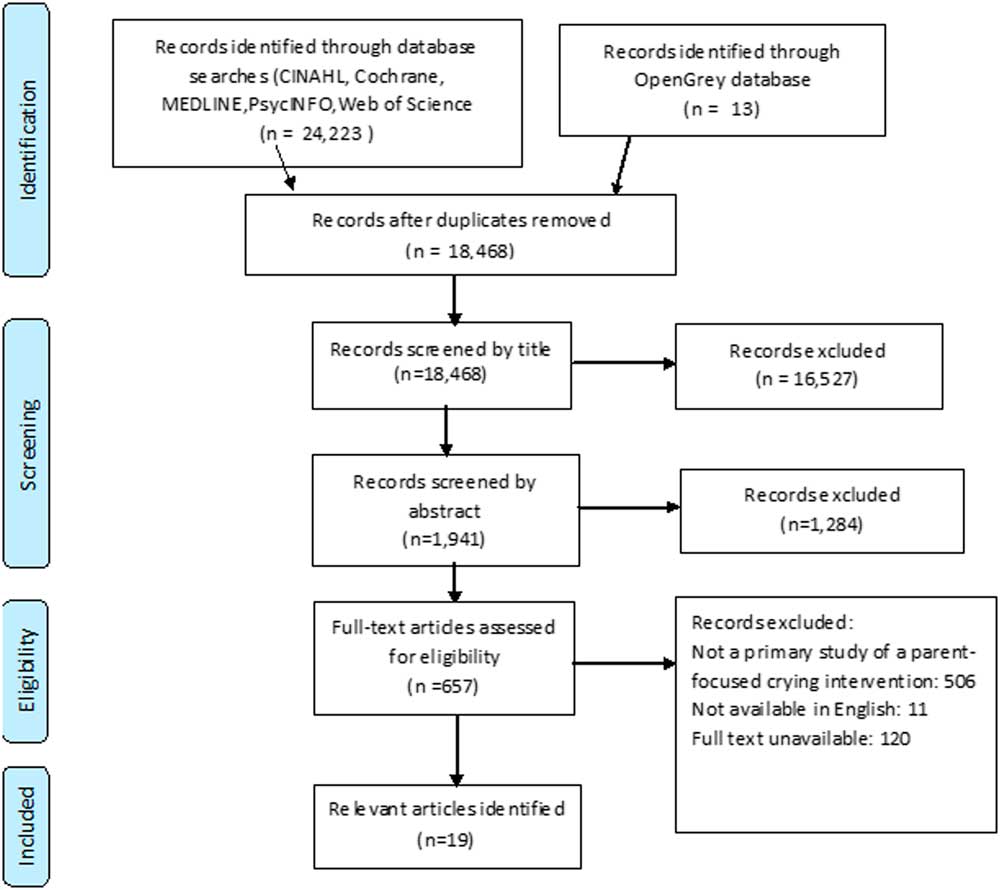

The results of the literature search are shown in Figure A1. Following removal of duplicates, 18 468 potentially relevant records were identified. Once title and abstract screening were completed, 657 records remained to be assessed for eligibility. Upon review, it was found that whilst many articles contained information relating to excessive crying, they did not meet the review criteria. These included studies considering factors which may contribute to the crying, and parents’ experiences of a crying baby. Others explored interventions not specifically targeting support for parents with crying babies, focusing instead on maternal mental health or directly attempting to treat the baby’s crying. Once these were excluded, a total of 19 relevant articles remained.

Figure A1 Results of the literature review process

The included articles identified a total of 11 different interventions (more than one paper having been published in relation to some interventions). These interventions were reviewed in order to consider their appropriateness within the context of this study using the following criteria:

∙ intervention materials available in a published and exportable form;

∙ delivery costs which allowed potential adoption of the intervention within the NHS;

∙ at least provisional evidence of effectiveness;

As a result of this process, four interventions were selected as shown in Table A1. The relevant organisations were contacted to gain permission for the materials to be shown and reviewed in the focus groups.

Table A1 Example support materials shown to the focus group parents

Identifying evidence for interventions to support parents experiencing postpartum distress

As well as identifying example support packages, the literature review aimed to review evidence for interventions found effective in supporting parental coping in general during the postpartum period. This decision was based on the premise that, since infant crying can be viewed as a stressor, its impact on parents would be due partly to how parents evaluated and coped with it and, consequently to parents’ underlying resources, vulnerabilities and circumstances. Using the same search strategies to identify relevant research, this literature review highlighted the existence of multiple randomised-controlled trials recommending the use of CBT programmes for this purpose. As these findings were also supported by UK National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (NICE, 2009; 2014) this was considered sufficient evidence for this study.