In July 1979, Charlotte Hutton, a working-class woman, not being able to afford a legal abortion in England, sought one in a back-alley clinic in Belfast. While the streets were battle zones for paramilitary combat, the alleys of the city witnessed another kind of violence, this one hidden from view. She died after the procedure. Although the Abortion Act of 1967 decriminalized abortion in Britain, the legislation did not extend to Northern Ireland due to the devolved Stormont government. Even after the introduction of “Direct Rule” in 1972, there was no expansion of the act into Northern Ireland. Much of the subsequent fight for abortion reform in Northern Ireland centered on extending the act to Ulster.

Hutton was memorialized in June 1980 in a socialist women's magazine in an article entitled “Scarlet Women 11,” which explained to readers: “She was not another victim of the troubles, but of a society that does not allow women control over their own bodies … she was not the first woman to die of such circumstances nor is she likely to be the last.”Footnote 1 Women like “Lotte” were not the exception, but archival silences have often led to their invisibility. The history of women during The Troubles (1969–98) contains large gaps and has been overshadowed by narratives of men in the period. Paramilitaries, for example, are chronicled in a number of archives, which contain a wealth of material on men's motivations, prison experiences, role as founders of political movements, and identities. Even though Sandra McEvoy conducted interviews with loyalist women in 2006, her access to those women was “heavily regulated by loyalist men.”Footnote 2 Filling in gendered knowledge gaps about The Troubles requires sources and archives that overcome this “regulation.”

Three decades after the Good Friday Agreement, repositories such as the Linen Hall Library in Belfast have built collections that explore the impact of sectarian violence and the path to peace.Footnote 3 While the Northern Ireland Political Collection is a must for any scholar of The Troubles, the library is also filled with resources for British scholars in a number of areas. One such innovative resource – the ExtraORDINARY Women collection – helps scholars answer questions about how gender history interacts with contemporary and local political history.Footnote 4 The collection documents the history of a range of women's political and civil rights in holdings that range from 1965 to the present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Banner for extraordinary women digital collection. Linen hall library website.

Grassroots organizations, second-wave feminism, increases in “mainstream” political activism, equal marriage, and abortion reform are documented in this wide-ranging collection. The archive contains a wellspring of material on how women in Northern Ireland navigated the familiar and continuous struggles around abortion, family care, workplace harassment, and political organizing. These were battles they had to wage while living in the extraordinary time of The Troubles, where one's well-being was precarious at best. Such quotidian struggles play out in these papers.

A challenge inherent in writing contemporary history is its reliance on declassified material, often stored in centralized locations. While national and state archives privilege official stories, historians can also make use of decentralized, local libraries and repositories. The Linen Hall archive relies on women sharing their private materials and thus dislodging the dominance of paramilitary and men's history from 1965 onwards. Pamphlets, buttons, magazines, and photos provide both breadth and a complicated view of cross-border Irish women's history, demonstrating political and civil rights campaigns that spread across the whole of Ireland and Britain. The collection markets itself as highlighting the unity and commonality among women during a highly divisive and tense period.

Founded in 1788, the Linen Hall Library is the oldest library in Belfast proper (Figure 2).Footnote 5 Located in a former linen warehouse, it is a rare institution in that it still has a subscription service to generate income. This system allows the library to remain free to the public. With two floors, a cafe, giftshop, and charity bookshop, the library has much to offer researchers, including archives ranging from nineteenth-century records to contemporary local history.

Figure 2. Entrance to linen hall library, belfast. Linen hall library website.

My own scholarship focuses on The Troubles, and specifically on the peace process that brought about the Good Friday Agreement. As a fourth-year graduate student at the University of Mississippi, I have had few chances to rummage around in the nooks and crannies of libraries and attics, seeking archival gems. Most of my research has occurred in national archives, which have highly standardized and rigorously controlled ordering processes and identification cards. One of the barriers in my work is the sensitive nature of many materials, leading to classification and closure. While studying a more contemporary subject has its downsides, such as documents that are off limits, one benefit is the chance to tell stories that have yet to see the light of day and that make use of records that are built into the city itself: in Belfast, for example, political murals and dividing walls still narrate a story of the internal violence of the period. The Linen Hall Library fills the space between the national archives and street-level culture. While the “divided society” has made great strides since the 1998 peace agreement, the process of coming to grips with public events is ongoing and contested. This occurred for me when I discovered the ExtraORDINARY Women's collection.

In searching through this archive, I hoped to find historical evidence centered on women's political issues during The Troubles, as I was seeking to understand how this period was central to what scholars usually identify as women's issues: abortion rights, sexual harassment, the fight for equal pay, unemployment. What I found – a rich vein of materials exploring women's lives during The Troubles – meant that I had to narrow my focus to one topic: abortion. Feminist magazines, political posters, and pamphlets demonstrate the continuous fight for abortion reform in Northern Ireland. The materials showcase how abortion was an all-Ireland issue, and The Troubles did not stop women's rights groups from reaching out across the border. Material here also illuminates a space where men in the two political traditions found common ground in opposing abortion reform. Furthermore, for British historians, the United Kingdom's influence on these Irish debates is also exposed.

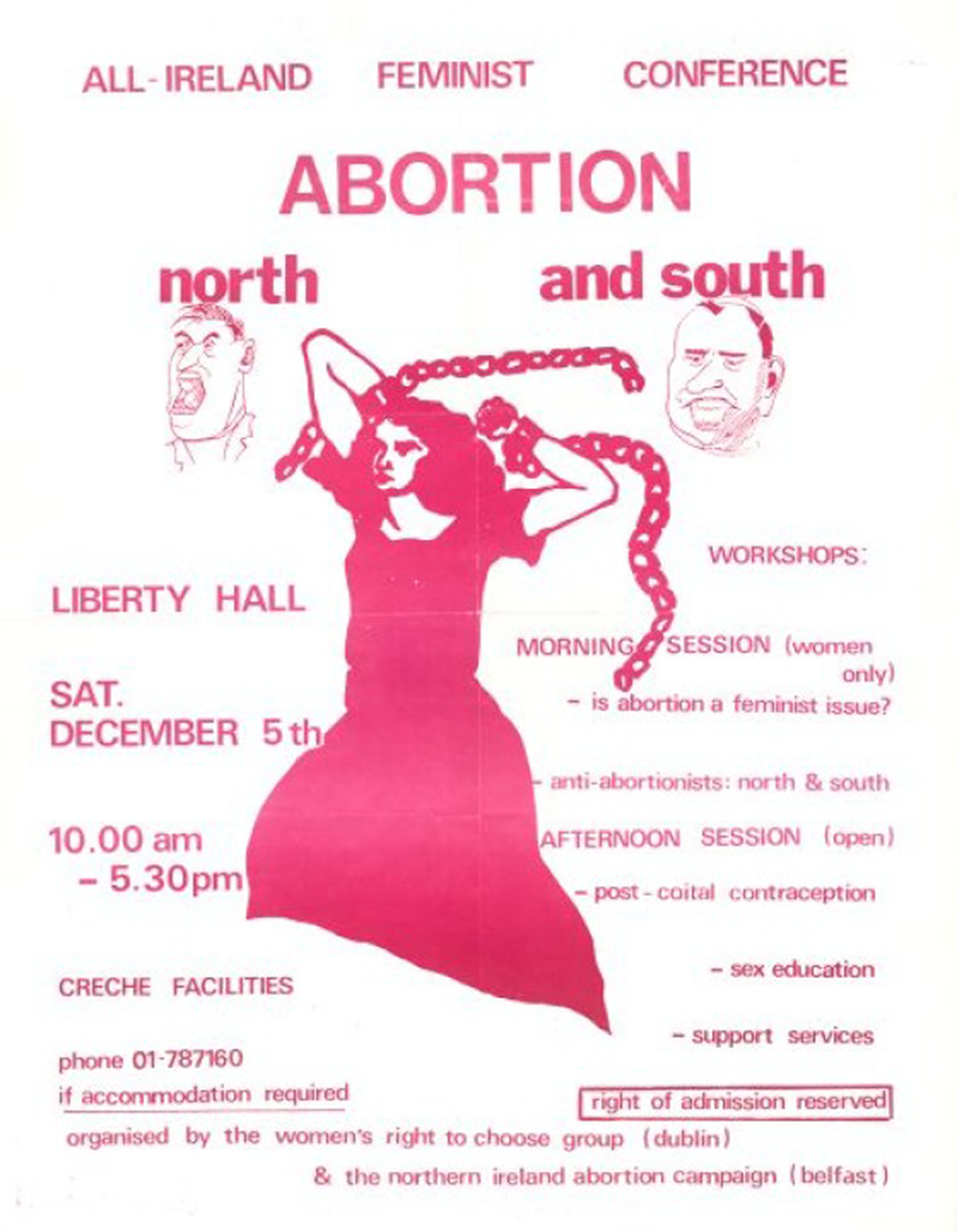

The collection contains records of organizations and individuals, and it crosses political divides – from liberal feminists to anarchist groups. Because abortion politics crossed borders, the library also collects pamphlets and periodicals that place Northern Ireland within a larger context. For example, the conference program for the “All-Ireland Feminist Conference” in 1981 presented abortion as an Irish woman's dilemma, for both “north and south” (Figure 3).Footnote 6 The meeting was organized by two civil rights groups coming together: the Women's Right to Choose (Dublin) and the Northern Ireland Abortion Campaign. Given the conservative Catholic Church's hold in the south and the dominance of Protestant churches in the north, solidarity among women's groups shines through, calling into question the rigidity of sectarian divides.Footnote 7 At one such meeting in 1981, the speaker from Northern Ireland noted the lack of attendance of the “organized left” and various feminist groups, saying “Perhaps Irish women's rights over their own fertility is too trivial an issue for them.”Footnote 8 In other words, the complexity of gender, politics, religion, and class is exposed through these archival holdings.

Figure 3. Pamphlet for the all-Ireland feminist conference in 1981. Linen hall library.

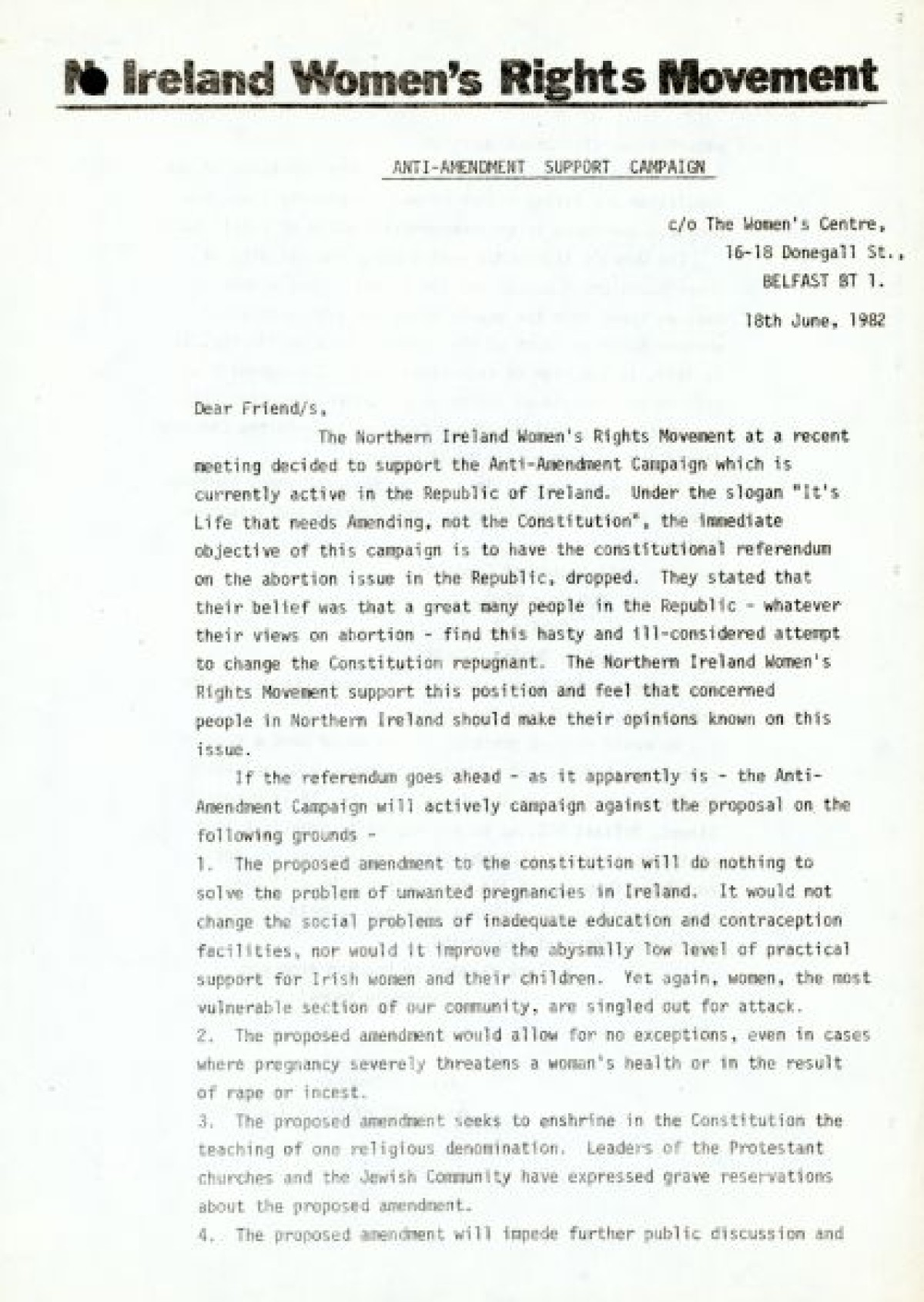

One particularly compelling set of documents from the early 1980s highlights a campaign against abortion legislation within the Republic led by Northern Irish women. Although the legislation did not directly impact their own rights, women campaigners understood the connections between their access to reproductive services and those across the border. One circular letter laid out the issue quite clearly: “The proposed amendment to the constitution will do nothing to solve the problem of unwanted pregnancies in Ireland … nor would it improve the abysmally low level of practical support for Irish women and their children. Yet again, women, the most vulnerable section of our community, are singled out for attack” (Figure 4).Footnote 9 The campaign makes the point that the amendment would not have made exceptions for potential health risks, rape, or incest, but also it was a “waste of public funds” at a time where one out of three in the population was living below the poverty line. The authors argued that the resources mobilized against legalizing abortion would be better spent improving the lives of those who were struggling, creating a connection that transcends political boundaries. Additionally, the organization lambasted the ways in which the amendment would enshrine Catholicism in the Constitution, incorporating the concern of both Protestant and Jewish leaders about the amendment. The organization voiced confidence in women's collaborative work to secure bodily autonomy, arguing that such solidarity between North and South, was a sign of “true sisterhood.”Footnote 10

Figure 4. Pamphlet for the northern Ireland women's rights movement (NIWRM) and their protest against the anti-abortion legislation in 1982. Linen hall library.

Solidarity is a recurring theme throughout much of the material, demonstrating that unity across the border was a way for all Irish women to create stronger coalitions against anti-abortion laws. Ironically, opposition to the liberalization of abortion law highlighted a solidarity among male nationalists and unionists, a fact that was not lost on women at the time. In 1991, a Belfast women's center newsletter spelled it out: “Ulster's political brethren are constantly united in their opposition to the extension of this act to Northern Ireland. Thus, what we have is a bizarre unity to block a woman's right to choose.”Footnote 11

By focusing on the single theme of abortion, I used the primary sources in this collection to highlight both solidarity and the multiple divisions within the “divided society.” Through encountering this collection, my research expanded to include a larger geographic scope as a result of the cross-border political material in this archive. I continue to research local and national cross-border political history leading up to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, and the Linen Hall archive informs and expands my perspective. While much history writing has focused on the differences between the two political traditions in Northern Ireland, working with the ExtraORDINARY Women's collection provides opportunities for new narratives that emphasize cross-border coalitions. Furthermore, the collection's focus on women provides opportunities to disrupt the exclusive focus on histories of political violence that often exclude both women and gendered analysis.

Bruce Wade Hodell is a 5th year PhD candidate at the University of Mississippi, Department of History, where he writes on the Northern Ireland Peace Process and British diplomacy in the aftermath of its empire.