Introduction

The uses of information and communication technology, digital devices, and the internet are now established ways of delivering health care. The term eHealth is used to describe these and encompasses “mHealth” (using mobile phones) and “telehealth” (using telephone or video software) offering digital health interventions that connect patients and health-care providers located in different physical locations (“connected health technology”) (World Health Organization (WHO) 2018). The potential for technology to dispense services to individuals and groups located in diverse locations has seen increased investment in eHealth by governments, bringing innovation and change to health-care systems (WHO 2019). The recent global pandemic of coronavirus (COVID-19) has accelerated advances in eHealth, as drastic measures to restrict viral transmission have meant computer technology becoming more important for communication to reduce in-person contact (Anthony Jnr Reference Anthony Jnr2020). Virtual care will be a key feature of health care going forward in a post-COVID world (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, Eggett and Holliday2021).

The uses of eHealth to change, monitor, and maintain patients’ behaviors and to educate and inform health-care providers, families, and communities have been a focus of research. For people living with life-shortening illnesses, eHealth can allow easier access to health-care professionals, reducing costs of travel and time and supporting patients and carers to cope with difficult and burdensome health conditions (Allsop et al. Reference Allsop, Powell and Namisango2018; Bonsignore et al. Reference Bonsignore, Bloom and Steinhauser2018). Increasingly, digital health interventions are being used to support the psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of this population, for example, web-based psychosocial interventions for caregivers (DuBenske et al. Reference DuBenske, Gustafson and Namkoong2014) and eHealth mindfulness-based programs (Matis et al. Reference Matis, Svetlak and Slezackova2020).

Favorable or similar quality-of-life outcomes for a palliative care population have been found in studies comparing virtual with in-person care (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, Eggett and Holliday2021). Nevertheless, there is limited knowledge of the effectiveness of eHealth for palliative care (Capurro et al. Reference Capurro, Ganzinger and Perez-Lu2014) and eHealth depends on user engagement, requiring additional strategies such as prompts to support this (Alkhaldi et al. Reference Alkhaldi, Hamilton and Lau2016). Importantly, there are concerns that enthusiasm for eHealth is overshadowing the need for evidence of its feasibility and effectiveness (Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Preston and Jones2019).

While recent systematic reviews describe the range of eHealth in palliative care, little is known about its application for psychosocial interventions. The breadth of applications of technology (education, decision aid, promotion of advance care planning, physical symptom relief, improving quality of life, and improving communication skills), the settings in which these are used (clinic and home), and the modes of interaction involved have been reviewed (Ostherr et al. Reference Ostherr, Killoran and Shegog2016). Another review highlights as beneficial the time-saving features of video consultations, the inclusion of relatives in patients’ treatment, and the uptake of video consultations by a wide age range of service users (Jess et al. Reference Jess, Timm and Dieperink2019). In their review, the provision of clinical assessments and communication with health-care professionals about symptom management by video is considered a strength (Jess et al. Reference Jess, Timm and Dieperink2019). Yet, another review by Finucane recognizes a lack of evaluation in research studies of digital health interventions. They highlight the positive impacts of eHealth such as communication, exchanges of information, and decision-making and education (Finucane et al. Reference Finucane, Donnell and Lugton2021). Mentioned within these and other recent reviews are the users’ experiences of eHealth, and there is some evidence across the world of eHealth’s acceptability by patients with a range of physical and mental health needs (Eze et al. Reference Eze, Mateus and Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi2020).

It is widely acknowledged that psychosocial interventions are integral to good palliative care (Warth et al. Reference Warth, Kessler and Koehler2019; Wood et al. Reference Wood, Jacobson and Cridford2019). These are provided by the multi-professional team (social workers, allied health professionals, psychologists, chaplains, and volunteers) working alongside doctors and nurses to support patients and their families at the end of life. However, there is a lack of information in current reviews of eHealth about psychosocial interventions for a palliative population delivered by trained practitioners. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the development and use of these interventions with computer-mediated communication supplementing and enabling standard interventions. The aim of this scoping review is to bring clarity and fill this knowledge gap by describing digital means of delivering psychosocial interventions (specifically where these involve a patient–practitioner relationship), their methods and therapeutic purposes, the personnel involved in delivering interventions, their outcomes, and ways these are evaluated for a palliative care population.

Review question

What are the digitally enabled psychosocial interventions delivered by trained practitioners being undertaken with adults with life-shortening or terminal illnesses and their carers/families receiving palliative care, and how are they being delivered and evaluated?

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco2020). Scoping reviews are usually deliberately designed to map the breadth of knowledge in a topic when its literature is heterogenous or its key concepts are unclear. In this way, the distinctive features of the area of interest are described and made available for further exploration. Unlike other types of systematically conducted reviews, there is no intention to aggregate, analyze, or synthesize the literature. The checklist set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Aanalyses extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al. Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin2018) supported the reporting of this review.

Concepts determining the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria

1. Psychosocial intervention: This refers any non-pharmacological intervention involving an interpersonal relationship between a service user (patient or family caregiver) and one or more trained health-care practitioners. This definition is based on Treanor et al.’s (Reference Treanor, Santin and Prue2019) review, which encompassed interventions that were “psychological, psycho‐therapeutic, psycho‐educational, or psychosocial,” or included a psychological or social component. The present review includes arts therapies (Collette et al. Reference Collette, Güell and Fariñas2020; Kievisiene et al. Reference Kievisiene, Jautakyte and Rauckiene-Michaelsson2020; McConnell and Porter Reference McConnell and Porter2017) and social prescription interventions (Fancourt and Finn Reference Fancourt and Finn2019).

2. People living with life-shortening, life-limiting, and palliative care needs: These are patients with non-curative, progressive, and advanced physical conditions that require the input from palliative care services, either in community settings or in specialist settings. It also includes their relatives and informal caregivers.

3. eHealth: This term encompasses “mHealth” (using mobile phones) and “telehealth” (using telephone or video software) offering digital health interventions connecting those located in different physical locations (“connected health technology”).

See Table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Review inclusion and exclusion criteria

Search strategy

Four databases were searched: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Academic Search Ultimate (see the Supplementary Appendix for an example of one search full strategy). Search terms were built around the concepts of “Psychosocial intervention,” “People living with life-shortening, life-limiting, and palliative care needs,” and “eHealth,” drawing from published search strings from relevant Cochrane reviews (Parahoo et al. Reference Parahoo, McDonough and McCaughan2013; Poort et al. Reference Poort, Peters and Bleijenberg2017; Semple et al. Reference Semple, Parahoo and Norman2013; Treanor et al. Reference Treanor, Santin and Prue2019) and sensitive and specific palliative care search filters (Rietjens et al. Reference Rietjens, Bramer and Geijteman2019; Zwakman et al. Reference Zwakman, Verberne and Kars2018). A sensitive search strategy was developed with the support of a specialist librarian by using database-indexed terms and adjacent words, (within keywords, titles, and abstracts of papers) as free text and search words for “palliative care”, “eHealth”, and “psychosocial.” The strategy was adjusted for each database and tested on 5 papers to ensure it was effective. Date restriction for retrievals was between January 2011 and April 2021, with no language restrictions (and an updated search was undertaken in November 2022). To capture the contemporary nature of the phenomenon, a 10-year time frame was considered appropriate for studies reporting research into telehealth. Quality assessment of the studies was not undertaken since it is not recommended for a scoping review, where the aim is to map evidence and not provide specific answers to defined clinical issues (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco2020).

Data extraction and management

Retrieved citations and papers were imported into Covidence, a web-based systematic review platform accessible to the review team. The reviewers M.W. and A.M. screened titles and abstracts independently and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with C.W. Discerning digital health interventions that met our criteria required careful reading given our inclusion criteria and the breadth of eHealth categories. Full texts were read by M.W. to confirm eligibility, and a sample was checked by C.W. Nonrelevant papers were removed at each stage. Data extraction of the included studies was undertaken by M.W. and C.W. using the template shown in Box 1. Following data extraction, data were summarized across studies, and a content analysis approach was used to identify and code broad thematic areas across the included studies.

Box 1. Data extraction tool

1. Citation details; peer reviewed Y/N?

2. Study methodology and description

3. Digital intervention description, characteristics, delivery, and context

4. Participant characteristics

5. Study evaluations and outcomes

6. Reviewer’s further thoughts/comments

Results

The number of citations retrieved, screened, and included is outlined in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Aanalyses extension for Scoping Reviews flow diagram.

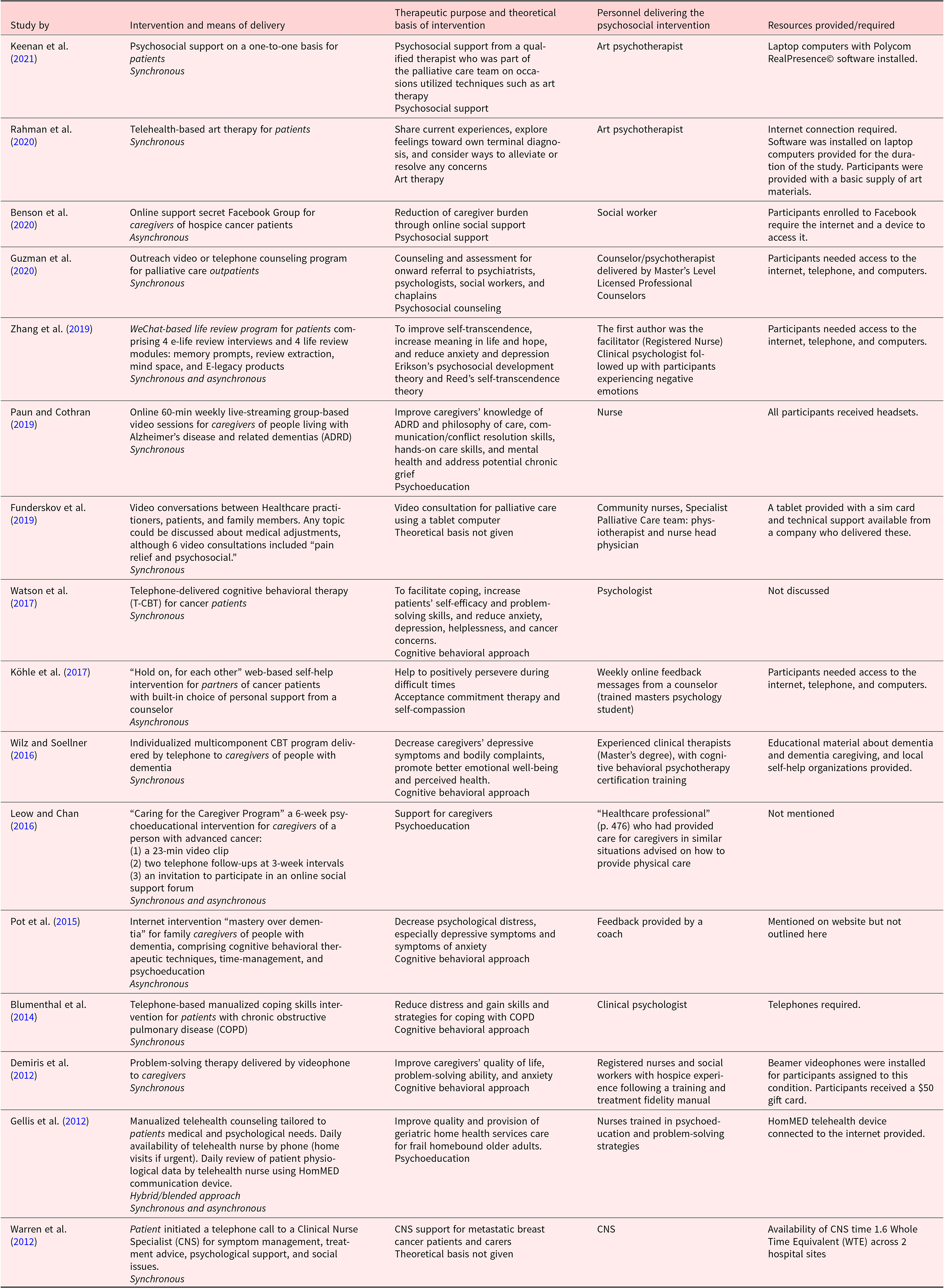

Retrieved studies came from Europe, including the UK (n = 8), Asia (n = 2), and the USA (n = 6), reporting small-scale pilot projects to studies embedded in randomized control trials. These heterogenous findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of included studies

Interventions

A range of digitally enabled interventions delivered in real time (synchronously) by telephone and video calls to palliative patients including those with advanced cancers, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were reported. Three interventions used workbooks or information on websites to supplement face-to-face and telephone support asynchronously (Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012; Leow and Chan Reference Leow and Chan2016; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019). Personnel delivering the digitally enabled psychosocial interventions included medics, nurses, social workers, psychologists, an art psychotherapist, a coach, and counselors in training. The most frequent psychosocial approach taken by interventions was cognitive behavior therapy in a manualized format (Blumenthal et al. Reference Blumenthal, Emery and Smith2014; Demiris et al. Reference Demiris, Parker Oliver and Wittenberg-Lyles2012; Köhle et al. Reference Köhle, Drossaert and Jaran2017; Pot et al. Reference Pot, Blom and Willemse2015; Watson et al. Reference Watson, White and Lynch2017; Wilz and Soellner Reference Wilz and Soellner2016), and other approaches included Erikson’s psychosocial developmental theory (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019) and art therapy (Keenan et al. Reference Keenan, Rahman and Hudson2021; Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Keenan and Hudson2020). Six interventions had a psychoeducational purpose offering strategies for managing distress, problem-solving, or gaining coping skills (Blumenthal et al. Reference Blumenthal, Emery and Smith2014; Demiris et al. Reference Demiris, Parker Oliver and Wittenberg-Lyles2011; Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012; Leow and Chan Reference Leow and Chan2016; Paun and Cothran Reference Paun and Cothran2019; Pot et al. Reference Pot, Blom and Willemse2015). Psychological and emotional support, reduction of physical and mental difficulties, and an increase in the quality of life were the therapeutic aims of other interventions. Personnel delivering these were not limited to one professional group – social workers, nurses, counselors, psychologists, and an art therapist were identified in our review’s studies. Who delivered the intervention depended on the context; medical and nursing staff offered psychosocial support within their general palliative care provision, referring to specialists when appropriate. Innovative bespoke/standalone psychosocial interventions were delivered by experienced trained staff or those undertaking training. Digitally enabled psychosocial interventions were provided at several points in the patient’s illness trajectory, from acute care of advanced cancer in hospital settings to patients living in their own homes or staying in hospice or residential facilities. Table 3 summarizes the interventions.

Table 3. Summary of interventions

Participants

Studies included patients, informal caregivers or family members, and health-care professionals.

The accessibility of psychosocial digital interventions was only occasionally discussed by authors. One study excluded participants with hearing loss (Funderskov et al. Reference Funderskov, Boe Danbjørg and Jess2019), in another at least 33% of participants were hearing impaired (Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012), and faced with technical difficulties one participant had to exchange their hearing aid for the headset at each session (Paun and Cothran Reference Paun and Cothran2019). Homogeneity of the ethnicity of participants was acknowledged as a limitation in several studies. Most recipients of interventions required a telephone as a minimum; most would have needed access to the internet and a computer. Membership of the social media platform Facebook was a requirement in Benson’s et al. (Reference Benson, Oliver and Washington2020) study. Only a few service provider agencies gave patients the digital tools to access services.

Evaluations and outcomes

Studies evaluated different types of outcomes, encompassing psychological phenomena, social functioning, general health, and users’ technical competence and preferences. Five quantitative studies reported statistically significant results for their digital interventions with improved changes in mood, meaning in life and hope (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019), improved well-being (Wilz and Soellner Reference Wilz and Soellner2016), quality of life (Blumenthal et al. Reference Blumenthal, Emery and Smith2014), increased caregivers’ problem-solving ability (Demiris et al. Reference Demiris, Parker Oliver and Wittenberg-Lyles2012), and fewer visiting to the emergency department (Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012), although effect sizes were modest or small. Two studies found no effect of the digital intervention. Watson et al. found no difference between their intervention delivered remotely and in-person for anxiety and depression (both groups improved) (Watson et al. Reference Watson, White and Lynch2017). The support of a coach in Pot et al.’s study of a self-help web resource made no difference to outcomes (Pot et al. Reference Pot, Blom and Willemse2015). Perspectives, expectations, and experiences reported by patients, health professionals, and caregivers all differed, as did participants’ preferences for visual and audio connection (video) and audio only (telephone). There was a preference for telephone from patients (Guzman et al. Reference Guzman, Ann-Yi and Bruera2020); caregivers in another study found video more useful than telephone (Leow and Chan Reference Leow and Chan2016); and health-care professionals valued being able to see changes in patients’ health during video consultations (Funderskov et al. Reference Funderskov, Boe Danbjørg and Jess2019).

Discussion

In this scoping review, primary research is mapped to describe digitally enabled psychosocial interventions delivered by trained practitioners to adults living with life-shortening and terminal illnesses and their family caregivers. The 16 eligible studies reviewed were qualitative and quantitative and undertaken by researchers in the USA, the UK, Europe, China, and Singapore. Research designs were pre- and post- studies, randomized control trials, feasibility, and pilot studies. Digital interventions encompassed asynchronous multicomponent web-based psychoeducational resources and synchronous contacts with practitioners by telephone and/or video call. While 2 studies mention mobile phones specifically (Wilz and Soellner Reference Wilz and Soellner2016; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019), and another describes telephone lines in patients’ homes that connected them to the study’s monitoring unit (Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012), further details about what type of telephones were used in other studies were absent. Understanding the impact of additional features of mobile phones – their portability, functionality in accessing the internet, and transmission of SMS texts – is likely to benefit the development of eHealth. Specialist practitioners, trainees, and nursing staff delivered interventions that were predominantly based on cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation principles, although counseling, emotional support and advice, and art therapy were also featured. The target recipients of these interventions were patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, advanced cancers, COPD, and heart failure, and family caregivers.

The reported effectiveness of digital tools to deliver, extend, or replace usual emotional support interventions varied between the studies. Better or equivalent outcomes to treatment as usual were noted in 4 out of 7 quantitative studies, supporting the positive findings documented in the qualitative studies. Our review highlights practitioners’ adaptations of usual practices for an online environment, indicating that it is possible to use technology to deliver this. The convenience of video consultations for medical and nursing purposes noted in other reviews is also important for patients needing psychosocial interventions (Mateo-Ortega et al. Reference Mateo-Ortega, Gómez-Batiste and Maté2018).

The relationship between health-care practitioners and service users was central to our review’s definition of “psychosocial intervention.” Different relational aspects of digitally enabled interventions were reported in the included studies, suggesting this as an enabling factor for getting started (Paun and Cothran Reference Paun and Cothran2019) or following up on any distress (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019). In (Watson et al. Reference Watson, White and Lynch2017) cognitive behavioral therapy study, the psychologist delivering interventions was expected to build collaborative therapeutic relationships; their patients’ mental health improved irrespective of the method of delivery (telephone or in-person), suggesting the relational value of the intervention. Nevertheless, the inclusion of self-guided psychoeducational activities for participants reported in some of our review’s studies favors the self-management approach that is in ascendence more generally in health care (Budhwani et al. Reference Budhwani, Wodchis and Zimmermann2019; Escriva Boulley et al. Reference Escriva Boulley, Leroy and Bernetière2018).

Other reviews have explored eHealth for caregivers. Wasilewski and colleagues concluded that web-based interventions are best targeted to caregivers’ needs at specific stages (Wasilewski et al. Reference Wasilewski, Stinson and Cameron2017), while Slev et al. (Reference Slev, Pasman and Eeltink2017) were unable to find any effects of eHealth for informal caregivers. These studies in our review indicate that the development and effectiveness of eHealth for caregivers is an area for further research.

Interventions in our review which integrated in-person and remote synchronous and asynchronous methods (Gellis et al. Reference Gellis, Kenaley and McGinty2012; Leow and Chan Reference Leow and Chan2016; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019) offer a model for health-care delivery post-COVID which is likely to be a hybrid of in-person, telephone, and online. However, patients’ preference and convenience may be the guide for how psychological interventions are delivered (Watson et al. Reference Watson, White and Lynch2017).

For people unable to travel to health appointments, telephone and video consultations are helpful, as studies reported in this review show. Widberg et al.’s systematic review of patients’ experiences of eHealth also makes this point; when patients and their families are involved virtually, they feel more included in care and symptom management (Widberg et al. Reference Widberg, Wiklund and Klarare2020). For frail older people with limited or no social and financial resources to transport them to health-care appointments, the provision of telehealth resources can be a lifeline, as seen in other populations (Suntai Reference Suntai2021).

Our review included research reporting the benefits of digital group interventions, reiterating findings from a systematic review of home-based support groups by videoconferencing, that these interventions were feasible even for those with limited digital literacy (Banbury et al. Reference Banbury, Nancarrow and Dart2018).

Strengths and limitations of this review

Identification of relevant studies was done against clear criteria and in a robust manner, but nevertheless determining inclusion and exclusion was challenging due to the range of terms and definitions used within the literature. We acknowledge the ambiguity created by studies that aggregated results from participants with advanced and earlier stage illnesses. Papers where the majority of participants had advanced illnesses but where palliative care was not mentioned did meet our inclusion criteria (Blumenthal et al. Reference Blumenthal, Emery and Smith2014; Watson et al. Reference Watson, White and Lynch2017). This reflects known fuzziness in practice where patients transitioning from curative to palliative care services overlap (Petrova et al. Reference Petrova, Wong and Kuhn2021). Our search terms focused on the interpersonal aspects of telehealth for a palliative care population (see the search strategy available in the Supplementary material); given the complexity of these phenomena, we cannot be sure to have identified or included all relevant studies.

Recommendations for research

Equity of access to appropriate psychosocial support is an ethical imperative for patients and this review has highlighted areas where further research could benefit palliative care services and the development of digitally enabled psychosocial provision for this sector. eHealth has the potential to reach more people by delivering targeted and cost-effective care. To do this, research studies must include those communities where communication and cultural barriers to psychosocial support in palliative care currently exist. These are people who are deaf and hard of hearing, have cognitive impairments or dementia, are people of color, or are from marginalized groups; individuals from these communities were under-represented in our review’s studies. The provision of digital resources by services to enable patients and family members to access interventions was evident in a minority of studies. This raises the issue of how those disadvantaged by low socioeconomic status (Demakakos et al. Reference Demakakos, Nazroo and Breeze2008) are at risk of digital exclusion from getting the care they need. Some steps are already being taken to research this area; more is needed (Watts et al. Reference Watts, Gazaway and Malone2020).

Manualized interventions based on cognitive behavioral therapy were most evident in the research studies; however, research into affective, spiritual, and cultural approaches to psychosocial support would benefit the field. Examples of these were seen in our review (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao and Chen2019) with its focus on psychospiritual well-being, the provision of art therapy packs (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Keenan and Hudson2020), and participants’ sharing gifs, emojis, and photos (Benson et al. Reference Benson, Oliver and Washington2020).

Our review identified personnel involved in digital interventions ranging from trained psychotherapy specialists and coaches to nurses offering psychosocial support and advice within their general remit. Identifying what type of practitioner is effective for the delivery of psychosocial interventions will be important for organizations establishing their staffing skill mix. Finally, further studies on when digital interventions are best offered on the care pathway to meet individuals’ palliative care support needs could help build effective hybrid multicomponent models of care.

Conclusion

All papers included in this review report digital health interventions prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting activities of early adopters of technology. Since then the pandemic has expanded this field of development in end-of-life and palliative care (Cherniwchan Reference Cherniwchan2022).

The findings of this review offer evidence that synchronous and asynchronous technologies, in conjunction with an interpersonal relationship between practitioner and patient/carer can be used to provide standard and novel psychosocial interventions to adults and families living with life-shortening illnesses. Emotional and psychological support at key points of the palliative patient’s illness trajectory can be delivered in-person, or remotely by telephone or video call. Websites can be used to disseminate information and educational activities that support psychosocial care, and social media platforms can enhance peer support for caregivers. The disruption to in-person palliative care services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted all health-care providers to consider telehealth. Lessons learned from studies cited in this review include issues of accessibility, digital exclusion, and how to build hybrid models of digitally enabled psychosocial interventions in palliative care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951523000172.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.