Writing in The Cambrian News, one reporter explained how the oldest inhabitants in the market town of Tregaron in Ceredigion, north Wales, could not remember a time like 1893 when the river Brenig ran dry under the town bridge.Footnote 1 Such memories and personal experiences of hot summers and low rainfall were used by newspapers and in official reports to make sense of the severity of conditions when local water supplies failed. What The Cambrian News article and other such accounts reveal is how throughout the long nineteenth century the need to understand periods of water scarcity and precarity became intimately interconnected with people’s experiences of water as Britain and Europe faced short- and long-term droughts. These accounts show how by the Edwardian period, communities regularly experienced the reality of their taps and wells running dry as informal, municipal, and commercial supplies were restricted or failed. Evidence from recent and historic droughts shows how water scarcity results in disruption and adaptation. Yet, there is a danger that we reduce these periods of disruption to a narrative of adaptive capacity that strips out how people experienced drought. To understand how drought affected communities, this article places the experiences of drought at the centre of analysis to ask: what did drought disruption mean for different communities in the long nineteenth century and how did behaviours change during drought?

As extreme weather events become more frequent, and as the crisis of global climate change intensifies, scholars have documented the links between climate variability and societal responses to predict the future. An increasing number of historians have become interested in the same issues. As the environmental historian J. R. McNeill commented in 2008, ‘the more one unpacks the concept of climate change into its components, the more the record of the past becomes relevant to imagining the future’.Footnote 2 Often focusing on the macro scale of pre-industrial societies, studies explored climate–society relations, social vulnerability, and adaption. The effects of regional social and economic activities, embedded cultural knowledge, values and norms, and infrastructures have been examined to understand responses to climate variability. Increasingly, attention has moved away from a narrative of statewide disaster and collapse to focus on the ability of societies to absorb external shocks (or their resilience) or recover from tipping points.Footnote 3 What has emerged is an image of pre-industrial societies as able to adsorb or adapt to climate fluctuations. In his work on medieval North Sea flooding, Tim Soens offered a nuanced reading of resilience as an adaptive process that unfolds in different geographical, temporal, and social scales, while other historians connected societal or regional vulnerability and adaptation to ecological, social, political, cultural, and economic systems.Footnote 4 Yet, despite the links between climate change and Bayly’s ‘birth of the modern world’, the same attention to climate and weather shocks, adaptation, and resilience has not been given to the post-1800 period even though climate-related events had a significant impact on nations and regions.Footnote 5

Droughts are highly visible weather shocks in the historical record but when scholars examine historic droughts in Britain they primarily use hydrological and meteorological data from the nineteenth century onwards to show when droughts occurred and what caused them.Footnote 6 Such attempts to recover the nature of past droughts has improved our understanding of climate variability, but knowing when drought occurs tells us little about responses to drought or how people experienced them. In ‘Drought is normal’, Vanessa Taylor, Heather Chappells, Will Medd, and Frank Trentmann broke with this approach. They used evidence from seven droughts in England between 1893 and 2007 to frame drought as a recurring socio-technical phenomenon shaped by historic patterns of infrastructure, water governance, and ideas of ‘normal’ water consumption.Footnote 7 Importantly, they argued that drought in England was not an exceptional crisis. Developing this idea, Taylor and Trentmann place scarcity in the context of governance and provision in their reading of the everyday politics of water and governmentality. They argue that scarcity is a form of ‘everyday disruption’ that illustrates key practices of everyday life as a terrain for negotiating citizenship and consumer rights.Footnote 8 Yet, while Taylor and Trentmann acknowledge adaption and agency through middle-class resistance and working-class improvisation during a discrete period of scarcity – the East End ‘water famine’ of the 1890s – their geographical and temporal focus, and their emphasis on middle-class consumers and institutional actors, obscures how other regions and social groups reacted to scarcity across the long nineteenth century. Equally, by seeing drought as a form of ‘everyday disruption’ they downplay different spatial and social vulnerabilities. What is missing from the existing scholarship is how people understood drought and experienced scarcity away from those large English cities where constant supply had become the norm by the 1890s. If Taylor and Trentmann champion the need to consider everyday experiences of water, geographical scholarship foregrounds how an understanding of climate–society relations is only possible through an examination of how people in different spatial contexts experienced weather shocks to get at ‘the consequences of environmental change for the everyday lives of people’.Footnote 9 Such an understanding requires an approach that combines an examination of how different regions experienced weather shocks and the messy world of everyday experiences. By utilizing evidence from meteorological reports, newspapers, official reports, and local government archives, this article sets out to provide this study of everyday experiences by comparing how urban and rural communities experienced drought and how daily behaviours and routines were adapted in response.

Drought is not something ‘objective’. It was experienced. Using the ‘everyday’ as an analytical tool helps us access these experiences. In the last few decades, the everyday has become a popular lens for social historians to reconsider questions of agency by examining common practices from banking to early modern seasonality or colonial life in South Asia.Footnote 10 Everyday life is never simple. As the social historian Joe Moran persuasively shows in his work on the spaces, practices, and mythologies of European life, the everyday places emphasis on those taken for granted quotidian practices and mundane routines that are often overlooked but make up people’s lives.Footnote 11 It makes the seemingly insignificant, such as domestic activities, significant. Equally, as the feminist theorist Rita Felski argues, it draws attention to the leakages between home and non-home and their temporal fluidity.Footnote 12 In this framework, drought in the long nineteenth century was not a non-quotidian event or a moment of crisis: it featured and shaped people’s daily or seasonal lives. These everyday experiences were firmly rooted in time and place. So too, as Georgina Endfield explains, were climate and weather which are always ‘nested in places’. Only through detailed regional studies is it possible to understand the effects of weather shocks.Footnote 13

A focus on Wales between 1826, the first major drought to affect Britain in the nineteenth century, and the end of ‘The Long Drought’ in 1910 provides a rich context through which to understand how urban and rural communities experienced drought. Welsh newspapers actively reported on local and regional droughts, while the reports submitted annually by Welsh local authorities to the Local Government Board (LGB), the main body responsible for public health and welfare in England and Wales, detailed their responses to scarcity.Footnote 14 Evidence from sanitary officials’ published and unpublished reports and from local archives adds to this picture of drought. Although the experiences of drought varied by region and community – silences exist in the source material when drought was short term or had little impact on local supplies – taken together these sources challenge perceptions of Wales as ‘a wet part of the world’ and give insights into everyday experiences that went far beyond short-term disruption.Footnote 15 The nature of industrialization, urban growth, and in-migration, and changing patterns of water supply in Wales created challenges that were common to other nations facing water precarity and scarcity, revealing generalized features of the experiences of drought. Wales was also a mountainous and rural nation, making it possible to explore the interconnections and differences between urban and rural experiences. Thinking about droughts in Wales challenges how our understanding that water scarcity only affects certain nations, regions, or communities.

The article is divided into four parts. The first section moves beyond a reading of hydrological and meteorological data to consider ‘when’ contemporaries felt they were in a drought. Where existing studies of drought focus on causation, an analysis of press reports, official records, and other evidence reveals how drought was experienced by those living in urban and rural communities as a regular occurrence between 1826 and 1880. What becomes clear from this evidence is how after 1880 droughts were experienced as occurring more frequently, lasting longer, and being more intense. By focusing on ‘when’ contemporaries thought they were in drought, it becomes possible to understand how perceptions and experiences of drought changed across the period; experiences that had little to do with questions of causation or scientific measurements of riverflow, rainfall, or temperature which attracted limited interest for newspaper readerships. The next section places experiences of drought in the context of urban and rural water supplies. It reveals the unevenness of supply to show different vulnerabilities to scarcity. By exploring how precarity and scarcity were rooted in political choices about water and its supply and local environmental conditions, the section compares the fragility of urban and rural supplies to challenge dominant narratives that stress municipalization and the creation of piped networks of supply. The third section reveals the tactics adopted to get water during times of drought. In doing so, it focuses on what water scarcity meant for people living in urban and rural communities and how drought reshaped behaviours. Rather than a unifying experience emerging during ‘The Long Drought’, the section shows how the social and gendered impact of drought on experiences and behaviours differed. The final, concluding section places everyday experiences of drought in the context of debates on resilience. It suggests how the everyday can helps us question the ‘resilience paradigm’ commonly used to think about the impact of weather shocks or climate change. In highlighting the plurality of practices, the article reconfigures how we think about responses to weather shocks and what happened at an everyday level when sources or networks of water supply dwindle or fail.

I

The Little Ice Age (1300 to 1850) had seen widespread periodic cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, but the wetter summers that had characterized the eighteenth century came to an end at the beginning of the nineteenth century.Footnote 16 Droughts became more common. Present-day reconstructions identify major droughts across England and Wales in 1826, 1854 to 1860 connected to a series of dry winters, and 1865, with the late nineteenth century seeing a clustering of major droughts in 1887 to 1888, 1891 to 1894, and 1902 to 1910.Footnote 17 Evidence from Europe and Africa suggests how these droughts were part of a wider pattern. Multi-year droughts after 1890 were part of ‘The Long Drought’ (1890 to 1910), the result of a cumulative hydrological deficit following a series of dry and cold winters and El Niño events. Yet, droughts had a temporal variability, fluctuating in intensity and duration. Distinctions exist between short duration droughts, such as the 1826 drought, which threatened water supplies in areas dependent on surface water, and long duration droughts (eighteen months plus) that characterized the period after 1890. Meteorological droughts are defined by sustained and significant periods of below-average rainfall and build up over a period of weeks, while hydrological droughts are associated with prolonged periods of shortfalls in surface or groundwater and occur over longer timescales. The latter produced a cumulative impact which affected urban water supplies in the nineteenth century. ‘The Long Drought’ saw the largest accumulation of hydrological deficits between 1890 and 2015 with rivers in England and Wales dropping to levels not seen nationally until the 1930s. The intensity of drought equally varied. Nationally, the 1887–8 drought was the third most severe since 1820 and particularly affected northern and western Britain, while 1893, 1898, 1899, 1902, and 1905 were the most acute years of ‘The Long Drought’ due to extremely dry autumns and winters.Footnote 18 Drought conditions across England and Wales in 1887–8 and 1905–6 were only exceeded again in 1976.Footnote 19 If droughts were not discrete events – they are part of large-scale patterns of atmospheric circulation – there were regional and local differences in their severity and duration. What, therefore, can the reporting of drought conditions in Victorian and Edwardian Wales tell us about the experience and frequency of water scarcity in the long nineteenth century?

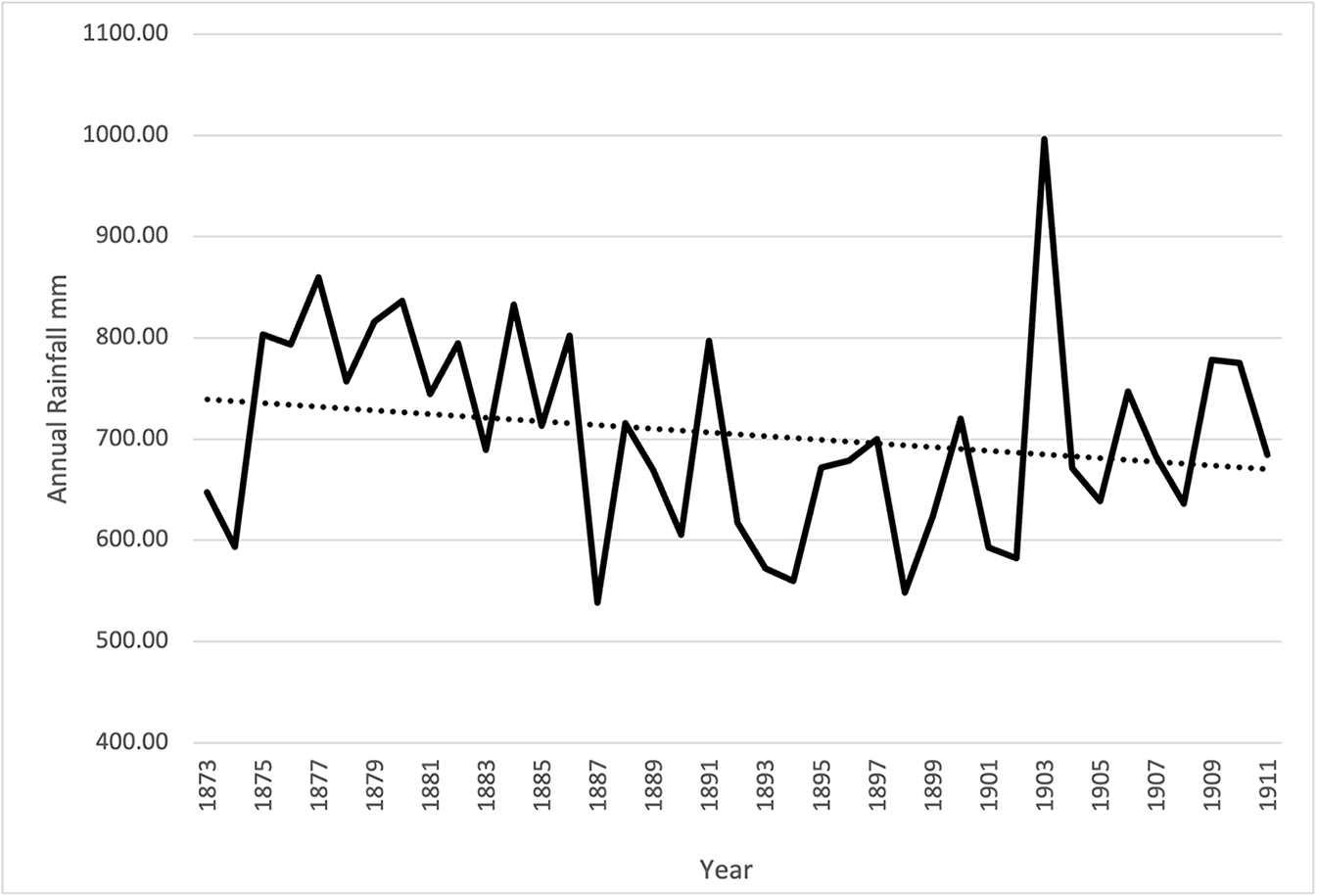

Limited or inconsistent instrumental evidence for rainfall, temperature, and riverflow before the late nineteenth century has created barriers for analysing patterns of drought in the past. Historic reconstructions recognize these limitations but extrapolated from hydrometeorological evidence from England. Incidences of drought in Wales have been subsumed into a narrative of major national droughts.Footnote 20 Annual rainfall data at a regional level does exist for the period after 1874 but Wales and the south-west are combined in one meteorological region. As Figure 1 demonstrates, periods of low annual rainfall in the region coincide with national droughts but also reveal how yearly average rainfall for the south-west and Wales declined across the period, with the years 1892 to 1902 seeing below average rainfall. Reconstructions from river catchments for the rivers Wye, Eden, and Teifi adds further evidence to highlight drier conditions in Wales in 1887, the 1890s, and 1905.Footnote 21 However, hydrometeorological evidence only goes so far. Drought is not something objective, simply determined by the measurement of rainfall or riverflows. What such evidence does not consider is the regional or community experiences of drought.

Figure 1. Annual rainfall in mm for south-west England and Wales, 1873–1911.

Evidence from newspapers and reports offer more insights to build a picture of when drought conditions were experienced. Newspapers not only reported on the actions of local authorities in response to scarcity but also ran editorials and published correspondence on drought. Where some reports might be little more than a few lines – simply reporting water shortages or moves to restrict supplies – they reveal how an experience of being ‘in’ drought conditions was a reoccurring feature of urban and rural life in Victorian and Edwardian Wales. Where anthropogenic pressures were acknowledged, different types of drought – meteorological, hydrological, socio-economic – were seldom identified. Drought was reduced to simple categories.Footnote 22 Accounts drew on the broad taxonomies identified by the British Rainfall Organization in 1868. As part of a remodelling of the science of meteorology to place increased emphasis on standardization and measurement, the British Rainfall Organization defined drought in two ways: ‘absolute drought’ – fifteen consecutive days with no rain – and ‘partial drought’ – twenty-nine consecutive days when the mean daily rainfall observation did not exceed 0.2mm.Footnote 23 While not all local episodes of drought attracted the same attention – droughts which lasted a short time or where local water supplies remained adequate for a community’s needs attracted little attention – the growing frequency of droughts after 1880 ensured that accounts increasingly spoke in terms of ‘absolute drought’ or more commonly of ‘water famines’. Reports went beyond the obsession with observations about the weather associated historically with the British: subjective reporting of local or regional experiences and conditions were central to how drought was written about.Footnote 24 Official records and the minutes of local authorities detailed how they and local communities responded to scarcity. Individual accounts and newspaper reports highlighted rivers and wells drying up, mountains and moors being devasted by fire, and the plight of communities and their struggles to get water. This contemporary reporting constructed a sense of drought from piecing together local and regional experiences, the state of local waterways, the impact of dry weather on agriculture, disruption to water supplies and industry, and changes in the landscape.

Newspapers had a central role. The growth of mass literacy ensured that more and more people were experiencing local, regional, and national events through the press. Weather shocks were no different. With weather experienced locally, newspapers provided an important conduit for making sense of drought at a regional or national level. As drought lacked a defining cataclysmic event and had a slow onset, newspapers charted the move from low rainfall to precarity to drought, piecing together local occurrences to create a sense of drought. Newspaper reports were little concerned with the causes of drought beyond noting high temperatures or low rainfall. Instead, they offered readers a human perspective on what constituted drought conditions for communities that had little to do with scientific measurement or thresholds. Common themes emerge: drought was presented as a crisis and after 1850 as an increasingly urban problem, with newspapers using drought to passionately demand better water supplies and berate industries or private householders for wasting water.

Despite the explosive growth of urban settlements in industrial south Wales, droughts in Wales before the 1850s were primarily understood through their impact on farming and agriculture. These droughts were typically of short duration and the repercussions for local communities were seldom documented. In part, this was because precarious water supplies were an accepted part of life for many communities into the mid-Victorian period.Footnote 25 The ‘unprecedented’ drought of 1854/5 marked a shift in how experiences of drought were reported. As Wales industrialized, as the number of water-dependent industries rose, as in-migration increased, and as urban settlements grew in number, size, and density, drought ceased to be viewed as simply an issue for farming. By April 1854, reports on farming had been replaced by concerns about the impact of drought on industrial communities, industrial production, and employment. After six months of drought, concerns shifted again. In September, reports started to focus on how towns were deprived of their usual water supplies. Drought became a problem for towns and villages as reports stressed local struggles to get water.Footnote 26 Reports on drought in 1858, 1859, and 1864 followed a similar trajectory: attention quickly moved from accounts of the impact on farming to alarm about water shortages in towns and industrial communities. By the mid-1870s, newspapers increasingly emphasized the impact of water scarcity on towns and industry.Footnote 27

Such recording of drought reveals the growing pressure on urban water supplies. Industrialization, migration, and changes to the built environment, particularly in industrial and mining communities in south Wales after 1850, placed existing water supplies under stress and made communities more vulnerable to scarcity in a period when water companies in large towns were only able to deliver a moderately reliable supply during periods of normal rainfall. Mining required regular draining to prevent flooding. This could affect local water tables beyond the colliery: watercourses were diverted and springs would disappear as they were tapped by mines.Footnote 28 Ironworks equally demanded substantial amounts of water: in Merthyr Tydfil, for instance, the mid-nineteenth century saw a water war as local inhabitants blamed the ironmasters for cursing the town with ‘drought, dirt and disease’ given their resistance to any scheme that would divert water from their works.Footnote 29 While industrial expansion placed demands on water supplies, reports stressed how water infrastructures were slow to catch up with urban growth. For example, the expansion of Newport as a focus for coal exports saw the population rise from 5,825 in 1811 to 27,435 in 1871, ensuring that the old reservoir was too small by the mid-1870s to supply the town during drought. Newspapers bemoaned how in Cardiff the 1880 drought was as much a result of dry weather as it was a ‘stationary’ water supply that had failed to keep up with rapid population growth.Footnote 30 Higher water consumption and new domestic habits, with the introduction of water closets and baths, were felt to add further pressure on existing supplies. Waves of reservoir construction after 1870 draws attention to unrelenting concerns about current and future needs as engineers and surveyors came under pressure to find new and reliable supplies in the face of urban growth and water scarcity. Caerphilly’s medical officer of health (MOH) outlined a common predicament facing urban councils by the early twentieth century: industrial growth, increasing urban populations, and migration had seen the demand for water rise at such ‘an alarming rate that it is only too evident our sources of supply are totally inadequate’.Footnote 31

As droughts became more frequent and more severe after 1880, and as reliable water supplies became the desired norm, a change occurred in how the experiences of drought were reported. If the impact on agriculture was not overlooked, a change in report styles associated with New Journalism saw opinion pieces, letters, and editorials increasingly highlight the human cost of drought. Drought became news. Between 1887 and 1889, reports drew attention to the hardship caused as communities were shown to be measuring their water supplies in days. Localized water famines were described in rural communities.Footnote 32 Where the 1887–8 drought was described as ‘exceptional’, the 1893 drought was reported to be ‘extraordinary’ and ‘unparalleled’ in its severity: even upland areas – where rainfall was higher – experienced severe shortages.Footnote 33 According to The Western Mail, March and April were the driest ‘ever experienced’.Footnote 34 One rainfall observer at Ross on the English–Welsh border reported in December how ‘The drought, which had lasted for 729 days…was the greatest since records began in 1818.’Footnote 35 As hydrological, meteorological, and anthropogenic pressures combined in the 1890s, the 1898–9 drought was remembered as the worst for decades.Footnote 36

Reports described communities and regions experiencing further, intense droughts in the Edwardian period: 1901, 1902, 1905, 1906, 1909, and 1911 proved particularly bad years in Wales as the accumulated impact of ‘The Long Drought’ hit communities hard.Footnote 37 North Wales and the upland areas experienced notable periods of water scarcity during these years when rainfall was 10 per cent lower than the average low rainfall for the previous decade.Footnote 38 Low rainfall over the winter saw drought warnings in February 1905 and by May newspapers described how queues formed to get water as some towns went without a supply for three weeks.Footnote 39 Throughout 1906, newspaper reports kept readers updated on reservoir levels which continued to fall: the largest reservoir in Llangollen district was reported to contain only a few gallons of water, while other reservoirs were described as down to holding less than a week’s supply.Footnote 40 Accounts spoke of restrictions placed on piped supplies, how water carts became an urban feature, and how householders were being advised to boil water as more marginal sources were turned to by urban authorities.Footnote 41 While for south Wales 1909 saw the severest period of drought since 1887, a further ‘abnormally dry’ summer was recorded in Wales in 1911.Footnote 42 W. Burgess, the rainfall observer at Whitney-on-Wye, noted how ‘Water in deep wells and surface streams failed almost entirely.’Footnote 43 Individual droughts may have been severe or prolonged, but by 1911 they were being reported as regular features of urban and rural life.

II

Experiences of water precarity and scarcity were rooted in local environmental conditions and political choices about water and its supply. Where macro-level studies note how vulnerability to weather events reflect time and place specific social, economic, and demographic conditions, a focus on the experiences of drought reveals how access to and the nature of supplies were important factors in producing different ‘trajectories of vulnerability’.Footnote 44 The creation of urban networks of supply, their relationship to public health and hygiene, and the fraught process of municipalization is a familiar narrative. Rather than a linear process, studies of nineteenth-century urban supplies reveal the ‘fractured and ambivalent course of municipal and public health reforms’, but the nature of provision and demand for durable supplies beyond large English cities is less well known.Footnote 45

Before the 1850s, many communities in England and Wales relied upon traditional means of supply from wells, ponds, rainwater harvesting, springs, or local watercourses. Supply was essentially localized and informal. Where John Hassan notes that English towns faced an impending crisis of supply by the 1840s as they grappled with the degradation of local supplies and growing demands from urban growth and industrial expansion, patterns of industrialization and urbanization in Wales and the relative small size of many Welsh towns and mining communities mitigated demand and ensured that the growth of commercial water companies was slower than in England.Footnote 46 While England saw a transition from informal to public supplies between 1850 and 1870, private companies came to dominate urban provision in Wales from the 1850s to the 1880s as local boards struggled with questions around cost and control.Footnote 47 With private companies motivated by profit, supplies were often restricted to domestic users in favour of industry or only served the main streets. In Swansea in south Wales, for example, only 13 per cent of properties were supplied by the private water company. In the market town of Denbigh, many of the side streets remained dependent on wells while those areas that were supplied by the private company had an intermittent supply into the 1890s.Footnote 48

The 1870s witnessed the start of a slow shift to municipal supplies in Welsh towns, a move in part shaped by the connections made between water scarcity and disease and by changing attitudes to municipal governance. As towns grew in size and as concerns about sanitation intensified, the decade saw significant borrowing by Aberdare, Aberystwyth, Bethesda, Cardiff, Conwy, Llandudno, and Maesteg to finance municipal water works. Further significant investment in water infrastructures occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Continued population and urban growth along with the need for more control over supplies to meet public health needs provided one set of impetuses. Demand also came from community pressure. As Taylor and Trentmann show for London’s East End during the ‘water famine’ of the 1890s, scarcity and disruptions further shaped the contours of this demand.Footnote 49 If there is little evidence of water users beyond Cardiff being mobilized as consumers, in calling for clean water supplies ratepayers mixed fears about outbreaks of disease with demands for more durable supplies as expectations about supply changed. Faced with growing and overlapping pressures, an increasing number of urban authorities took over responsibility from private companies. However, the provision of uninterrupted domestic supplies through municipal control was slow and uneven in Wales.Footnote 50 Ystradyfodwg Urban District Council, the largest urban district in Britain, for example, had piped water for only a couple of hours a day into the mid-1890s. Neath in south Wales was a major industrial centre but only had a constant water supply for eight months a year in 1898: for the rest of the year, supplies were limited to nine hours per day.Footnote 51 Other urban communities, particularly colliery villages, continued to rely on standpipes.Footnote 52 The slow pace of municipalization and the fragmented move to high-pressure, constant supplies in Welsh towns ensured that the new connections between private and public life forged through improved water infrastructures was slower to take shape.Footnote 53 With intermittent supplies the norm in Wales, numerous towns hence remained vulnerable to scarcity during the Edwardian period: many were reliant on a mixture of wells, pumps, and piped supplies from private and municipal sources.

Urban networks of supply became visible as they broke down during drought. In the rapidly growing industrial town of Swansea, drought in 1870 saw ‘ratepayers put on half-time’ and the municipal water supply cut off in the afternoon.Footnote 54 Seventeen years later, Swansea again experienced precarious supplies for the next three years. By June 1887, reports spoke of parts of the town going without a supply for ten days. Over thirty water carts were in use and consumers were advised to boil their water as the supply from temporary standpipes was not fit to drink. Old wells had to be reopened.Footnote 55 Writing about the parish of Ystradyfodwg on the border of Brecknockshire in 1887, J. R. James, the MOH, described how ‘The long Summer drought found our two Water Companies to be unequal to the supply required by the District.’ As residents complained about lack of water, he told the local board how ‘many houses went, now, and again, for days without any supply’.Footnote 56

Following the 1887–8 drought, an investment in extending catchment areas, improving water storage, and managing consumer demand ensured that water supplies in towns became more durable. Yet, these technical responses did not insulate towns from the privations of drought. Drought conditions between 1893 and 1899 – one of the longest in seventy years – put urban water supplies under considerable stress. Scarcity exposed the limits of Liberal governance when predicated on voluntary restraint and social norms.Footnote 57 New techniques of control were introduced. Across Wales, urban authorities responded not just with technical solutions to improve supply but through an intensification of regulation. Scarcity offered a rationale to extend controls as local boards deployed a range of strategies to maintain some level of domestic supply as individual rights were balanced against community responsibilities. These interventions were framed as serving ‘the public good’ yet also reveal how the desired standards of character and respectability associated with Victorian liberalism proved flexible during drought. The inability of individuals to self-regulate in the face of frequent and severe drought legitimized the use of by-laws to intervene in the everyday routines of consumption, which municipalization in the 1880s and 1890s made possible. In the Rhondda valley, for instance, printed signs informed residents when water was available as municipal supplies were restricted to three hours per day during the 1895 and 1899 droughts.Footnote 58 After four years of the accumulated effects of drought, many towns, even those that had good supplies, restricted water supplies to a few hours a day during the 1899 drought. Between 1905 and 1911, repeated reports of restrictions reveal the continuing fragility of urban supplies, especially in manufacturing and small towns.Footnote 59 The limited availability of high-pressure, constant supplies across Wales meant that these controls provoked little overt resistance. Unlike English cities, where uninterrupted supply became the norm in the 1890s, urban consumers in Wales adapted to a regime in which drought and restriction were embedded in the rhythms of everyday life during ‘The Long Drought’.

Restrictions to supply were not the only indicator of, and urban response to, scarcity. As water supplies dwindled, urban authorities expanded their regulatory reach in an effort to police consumption.Footnote 60 Special notices were printed urging restraint and discouraging waste. In the small town of Llanyssul in Ceredigion, for example, special wardens were appointed in 1893 to regulate access to scarce supplies as the amount of water per person was limited to a gallon and a half, a twelfth of what public health experts considered the daily minimum for personal and domestic use.Footnote 61 Hosepipe bans were introduced, such as in Cardiff during the 1896 drought.Footnote 62 Scarcity saw urban authorities increase their surveillance. Nuisance inspectors used regular house-to-house inspections to identify leaking taps and fittings to limit wastage. In a number of towns, the police were asked to exercise vigilance to identify those felt to be unnecessarily wasting water against a background of local and national debate on entitlement and waste in times of scarcity.Footnote 63 In Aberdare, for example, where supplies were limited to one hour per day during the height of the 1896 drought, police courts issued ‘exemplary fines’ to those ‘wilfully wasting water’. In Cardiff, police courts felt that they had little choice but to impose the maximum fines of 40 shillings for wastage.Footnote 64 Councillors calling for harsher penalties against those caught wasting water found ready support in editorials as urban communities struggled with scarcity.Footnote 65 These practices reveal how drought functioned to extend municipal surveillance to reinforce a moral economy of restraint during periods when drought made water into a limited resource.

Drought was not just an urban problem. Where droughts reveal the precarity of urban supplies, poverty and the nature of supplies in rural communities made them yet more vulnerable to drought. Rural vulnerability was more than a discourse constructed through the press and reports: even at the best of times many villages did not have reliable water supplies. Contemporary commentators were quick to blame those living in rural communities for these deficiencies, accusing them of clinging to old-fashioned ways and being ignorant of modern standards of domestic comfort. Evidence from the records of rural authorities challenge these interpretations. Pressure to improve local supplies grew after 1880 as rural communities embraced the value of clean and reliable supplies in the same way as those living in towns. However, practical and economic barriers existed to both municipalization and piped networks of supply.Footnote 66 Many rural authorities in Wales were poor and had limited financial resources. They faced the same barriers to sanitary improvement Christopher Hamlin identities for mid-Victorian towns but were further constrained by the relative isolation of many rural communities or the distances between them. Low population densities and high levels of out-migration meant that the demand for local authority control was limited. Although groundwater provided a small but vital component in rural supplies, Wales’s reliance on surface water and technical difficulties of supplying water, especially to communities in mountainous districts, created further barriers. Many rural authorities therefore had little option but to rely on low-cost, localized solutions to meet the growing demand from communities for improved water supplies.Footnote 67

Notwithstanding growing demand for better rural supplies, many rural homes in England and Wales lacked piped or reliable water supplies until the 1920s. ‘Almost without exception’, as The Leeds Mercury explained in 1892, those living in rural districts on both sides of the English/Welsh border ‘are dependent upon streams, ponds, and wells’.Footnote 68 In a paper before the North Wales Sanitarians in 1900, Levi John, sanitary inspector to the Conwy Rural District Council (RDC) in north Wales, explained how the ‘water-supply in Rural Districts is in most cases of a variable character – some districts are dependent entirely on rainwater stored in wooden tubs and casks, others derive their supply from shallow wells’.Footnote 69 Inspectors for the LGB commented on how even in larger villages fetching water from local watercourses or using buckets at local wells or pumps remained a feature of rural life into the Edwardian period.Footnote 70 The clergyman and diarist Francis Kilvert wrote in his diary about how in the 1870s people in the village of Clyro in Radnorshire used pitchers to get water from the river Wye. Forty years later, a 1911 report on Cowbridge in Glamorganshire detailed how nearly half the houses took their water in buckets from the local well.Footnote 71 Getting water could be demanding work in rural communities. As Lloyd Roberts, MOH for St Asaph RDC in Denbighshire, explained in 1909, children in Rhyd-y-vale would carry ‘half a gallon of water a quarter of a mile and up a steep hill’ often waiting hours for the well to re-fill. Water precarity was part of the rural experience. Even in an average summer, water supply in rural communities was widely viewed as inadequate.Footnote 72

If those living in rural communities were more familiar than their urban counterparts with water precarity, poor or limited supplies in villages made them vulnerable to drought. For The Western Mail, getting water in rural communities during the 1887 drought became as difficult as it had been in the 1840s and 1850s when little water infrastructure existed.Footnote 73 As droughts became more regular and lasted longer, they placed slowly building stress on rural communities. For instance, in Hay rural district, the MOH wrote about how villagers faced slowly dwindling supplies during the 1893 drought.Footnote 74 During the 1911 drought, the Llantrisant and Llantwit Fardre RDC had to cut off the local supply, first for days and then weeks.Footnote 75 Where water supplies could be intermittent in towns, villages faced the prospect of supplies entirely failing during drought, forcing inhabitants to walk long distances to get water. Equally, the coping strategies available to the inhabitants of towns with piped supplies during water shortages, such as leaving taps open to collect water when it came back on, were not available in rural communities.Footnote 76 Instead, those living in them had to rely on ‘locally situated ways of knowing’ to determine where other sources of water could be found during droughts.Footnote 77

III

Recording the frequency and intensity of droughts tells us little about their social significance. Reporting on the difficulties of supplying water in the villages around the market town of Cowbridge in the Vale of Glamorgan in 1901, the medical officer Booth Meller highlighted the ‘great inconvenience’ communities across his district faced during droughts.Footnote 78 ‘Inconvenience’ could mean different things for urban and rural communities and for the individuals living in them. For individuals, experiences were shaped by local environmental conditions and their access to water, their location, class, and gender. Those with domestic servants, for instance, were more distant from the difficulties of getting water during drought. Their experiences were not recorded. Most accounts focused on the community level or talked in general terms about ‘people’ but hints are given about how different groups were affected. Women and children in working-class and poor families had a heavier burden. Miners were affected in other ways as reports noted the difficulties of washing after work. Accounts stressed how those living in rural communities faced particular challenges. What did ‘inconvenience’ mean in practice, and how did drought reshape behaviours?

As Endfield explains, ‘the weather has been woven into our experiences of modern life in many ways’. It ‘punctuates our daily routines’ and is inscribed into the fabric of communities.Footnote 79 During drought, these daily routines were disrupted: if the water closet saw a trend for households to turn inward, drought forced them to look outward.Footnote 80 As drought became imminent, urban authorities called for consumers to reduce their usage to ensure ‘every drop of pure water is saved’ for the whole community.Footnote 81 As drought deepened, ordinary everyday practices became more visible and more difficult. Daily routines, habits, and practices changed. At a mundane level, people washed less or not at all. As E. P. Tapp told The South Wales Echo in 1887, moves to restrict water supplies during drought had a direct impact on working men. With many not returning home until after 6pm, Tapp pointed to the distress caused by moves to limit or cut water supplies in the evenings and how this left no water for men to wash in.Footnote 82 Newspapers described how the backbreaking but domestically significant work undertaken by the wives, mothers, and daughters in washing miners’ bodies at the end of shifts ceased during drought or saw miners making use of what little water remained in local ponds. Nor was the impact limited to miners and working men. With piped supplies restricted, reports noted how people turned to wastewater or ‘slop’ to wash in.Footnote 83

As practises are entangled with the materiality of supply, pragmatism became important when the sources of supply people routinely used were restricted or failed. Queues formed at pumps and water carts as people waited their turn to get water.Footnote 84 During the 1864 drought, The North Wales Chronicle described how in Holyhead, the largest town on Anglesey, ‘scores of every age and sex [were] to be seen waiting their turn’ for the water cart ‘not only every day of the week, but every hour of the day and night as well’.Footnote 85 Accounts spoke of water carts being besieged when they arrived. Getting water became a preoccupation. Pitiful sights were observed in Briton Ferry during the 1896 drought: here people waited ‘for hours to obtain a supply in their small jugs, tin cans, buckets’, while in the Cockett district of Swansea people ‘waited all night long’ during the 1899 drought to fill their jugs with water.Footnote 86 Where some queued or waited hours to get water, others walked to find water. Where distances of 400 to 500 yards were considered normal to get water, during droughts people were reported walking up to three miles.Footnote 87 For example, as many wells dried up in the market town of Conwy during 1864, The North Wales Chronicle spoke of people ‘wander[ing] for miles amongst the mountains to obtain a can full of clear water’.Footnote 88 Residents of the village of Dyffryn wrote to the LGB to complain about the distances they were forced to go to get water during the 1893 drought: ‘All the wells are dry & there is only one place where we can get for a distance of nearly two miles.’Footnote 89 If drought drove local residents to walk to ‘the neighbouring hills’ with ‘pails, toilet jugs and tin cans of every description’ to find water, people would equally rise at three or four o’clock in the morning to make the most of what little water had collected overnight in local wells and streams. Neighbours would endeavour to beat others ‘in order to catch’ any available water.Footnote 90 Getting water became competitive.

Different decisions were made during drought about what water was fit to use and drink. The usual telltale olfactory and visible indications of purity and cleanliness were overlooked during periods of scarcity, particularly in rural areas.Footnote 91 In the mainly agricultural district of Penclawdd in the Gower peninsula, for example, the MOH described how during droughts residents used foul-smelling water ‘from many sources subject to pollution’. This included the Newton well near Bishopstone, which was locally known to be polluted by dogs, pigs, and other animals.Footnote 92 Members of the Llanelli RDC were informed how during the 1907 drought, tenants and farmer labourers ‘are actually compelled to use ditch water for drinking purposes’.Footnote 93 Those living in smaller towns could find themselves in a similar position as they struggled with water shortages. For instance, those living in the seaside town of Penarth complained they faced Hobson’s Choice during the 1884–5 drought: ‘either foul water or none’.Footnote 94 The consequences of using such supplies were viewed as ‘disastrous’ but calls for people to avoid them were ignored.Footnote 95 Long-standing tensions over the quality of water supplies seemingly evaporated during periods of drought.

Often the biggest impact of scarcity was on the everyday routines of the home. As The Cambrian News commented, drought ‘hinders household duties’.Footnote 96 Ordinary domestic tasks became more difficult or time consuming. Although household labour was seldom talked about in sources on drought, just as towns saved water by not flushing drains or cleaning streets, tasks that needed large quantities of water, such as washing clothes or preparing baths, became more infrequent or required a different approach. Where water was scarce, some ceased domestic chores. Writing about local villages, H. J. Hill explained to Chepstow RDC how during the 1909 drought a shortage of water meant that ‘I have known people…unable consequently to do their washing.’Footnote 97 More often, alternative strategies were adopted. In the colliery village of Ynysybwl in the Rhondda valley, for instance, one inhabitant explained how during the 1887–8 drought the

scarcity has become so serious that the inhabitants are compelled to resort to the river [Nant Clydach]. I noticed to-day several parties on the river’s bank with their water utensils engaged in scrubbing different articles of clothing-to their heart’s content. Fires were lit on the rock; for the means of boiling the water.Footnote 98

That the change of behaviour in Ynysybwl was worth reporting suggests that this was an unusual sight when it came to washing clothes. The class and gendered dynamic of water scarcity was at its clearest here. Working with an earlier eighteenth-century frame, Emma Moesswilde showed how the nature of women’s lives ensured they had an intimate knowledge of local variabilities in the climate, which they responded to in going about their domestic work.Footnote 99 Although reports on drought in the long nineteenth century did not foreground working-class women’s experiences, they equally hint at how it was women who changed their behaviours in response to variations. Scarcity reshaped the rhythms of their days. Reports indirectly suggest how water scarcity materially increased women’s domestic work and the hardships they faced, especially for miners’ wives in physically isolated valleys.Footnote 100

In an opinion piece ‘What the drought means’, The Western Mail hinted at this work. Women, as homemakers or domestic servants, were expected to tackle the large amount of dust that came into the home with drought, reinforcing how individual and public respectability linked women’s domestic work to cleanliness. But women’s toil and domestic labour did not stop there. Crucially, The Western Mail explained how during droughts ‘it becomes housewives to be more zealous than ever’ in how they marshalled water resources.Footnote 101 Newspapers gave little voice to these or other women given assumptions about their domestic roles. If the toil and exhaustion of domestic labour was rarely discussed, newspapers made generic reference to ‘females’, ‘wives’, ‘mothers’, and ‘daughters’. Writing during the 1884–5 drought, one correspondent to The Flintshire Observer described how ‘our females are on the watch all night through at water fissures here and there to waylay the precious liquid as it painfully oozes out’. They went on to describe how ‘I see daily, mothers and daughters of our people skimming to and fro like swallows in search of water.’Footnote 102 Drought not only increased domestic labour but also changed the rhythms and routines of women’s days. In the villages covered by Swansea RDC, The Western Mail reported how the burden of getting water fell on women during drought. It reported how they waited hours ‘at night [for] their turn to get water’. In the Swansea suburb of Cockett during the 1899 drought, both young and old women were seen ‘trudging along under the weight, some of one, others even of two earthenware or tin cans, holding from three to five gallons of the indispensable liquid’.Footnote 103 Queuing, travelling, and waiting for water fell mainly on women, adding to the hardship of their domestic tasks given the ‘exacting standards of domestic labour’ in Wales.Footnote 104

IV

Speaking at a meeting of Bangor town council in 1910, the mayor H. C. Vincent told those in attendance: ‘who is to say in his wisdom that in the coming summer they would not have a serious drought’.Footnote 105 Although ‘The Long Drought’ was to end that year, drought had become a regular feature of people’s lives in communities across Wales throughout the 1890s and 1900s. Even in those communities with a piped supply, water precarity and scarcity had become commonplace. The Welsh press spoke of ‘drought season’ with a sense of inevitability. In urban areas, regular droughts saw water supplies restricted to a few hours per day, queues form at standpipes or water carts, prosecutions rise for those believed to be wasting water, and warnings issued about water quality. In rural districts, communities could go without an easily accessible supply of water, sometimes for weeks. Where experiences did converge was at a local authority level. As drought became regular and mundane, urban and rural authorities worked to improve water supplies: they anticipated drought and factored it into their planning. For instance, although the seaside resort of Aberystwyth largely escaped drought restrictions, the design of the new service reservoir ensured ‘an ample supply’ should there be a six-week drought.Footnote 106 Likewise, in mid-Wales, the Rhayader rural sanitary authority enlarged its reservoir to meet the needs of the district during anticipated droughts.Footnote 107 As newspapers repeated the fears of local counsellors and medical officers of health about the prospect of imminent water famines, water scarcity saw communities adopt behaviours for conserving or getting water.

Did this make communities in Wales resilient? In the historical literature on resilience, the focus has been on adaptation. Here, resilience becomes a positive adaptive strategy.Footnote 108 In this sense, Wales in the long nineteenth century proved ‘resilient’ to drought: short-term adaptions were made and local authorities worked to mitigate the impact of water scarcity or invested in more durable water supplies. However, as Soens persuasively argues, historical case-studies reveal the limitations of the ‘resilience paradigm’ with its focus on adaptive cycles. For Soens, we need to consider how resilience could unfold differently across geographic, temporal, and social scales.Footnote 109 We also need to ask who gets to be resilient to disaggregate individual and community experience from societal-level analysis. Weather shocks (or natural hazards) such as drought did not affect society evenly as a whole. Framing them as part of an adaptive cycle overlooks how they could strengthen vulnerabilities, periodically overwhelm existing services, or become part of people’s daily or seasonal lives. Resilience emerges out of the context of everyday life. It occurs often in familiar places from the home to the village pump, places overlooked in existing accounts which focus on a societal or regional level. Resilience is not just about what individuals, communities, or governments do, but about the places they live, the choices they can make, and the resources they have access to. If historical case-studies are encouraging scholars to be attuned to the socially patterned nature of vulnerability and how adaptive strategies are unevenly distributed, what ‘resilience’ and adaptation looks like for one town or village was very different from what being ‘resilient’ might constitute elsewhere.Footnote 110 When it came to drought, changes to behaviour and the nature and shape of adaptation was influenced by the precarity of local supplies, by how households accessed water, and by class, gender, and location. The same differences play out across time given changing attitudes to water consumption and access to durable supplies. Although Edwardian local authorities planned for drought, precarity, scarcity, and disruption had a spatial and temporal dimension. A comparison of multiple reports, newspaper accounts, and archival records shows how different local or regional circumstances, local knowledges and practices, and existing water infrastructures affected the impact of droughts. All had (and have) a bearing on resilience and how drought was experienced. As routines and practices changed in response to scarcity, drought revealed the fragility of urban and rural water supplies, the shifting nature of water precarity, and different vulnerabilities.

No single, unifying experience of drought emerged. Changes to behaviour could be big or small but while drought became a feature of everyday life during ‘The Long Drought’, experiences differed across urban and rural boundaries. For urban communities, the disruption caused by the growing frequency, intensity, and duration of drought after 1880 was partly offset by an investment in municipal water supplies. This did not mean that towns escaped disruption: their experiences of drought were increasingly framed by restrictions and intermittent supplies rather than by a breakdown in supplies which had characterized the early to mid-nineteenth century. Rural experiences were different. If drought was disruptive for urban centres, precarious supplies in rural communities ensured that the everyday effects of water scarcity became acute in villages and could last longer. In some villages, drought continued to overwhelm the water resources available to them. Where urban and rural experiences of disruption reveal the varying spatial and temporal contexts of weather shocks, adaption equally meant different things for different communities and individuals. These differences reflected the variable material conditions of supply and an individual’s or communities’ ability to secure a water supply during drought. For some, adaption meant queuing for water or walking long distances to find water; for others, it meant frustration and jostling at water carts or turning to polluted supplies. For women and children, it meant an increased burden.

While simple analogies or parallels are problematic between past societies and the modern world, how different communities in the long nineteenth century experienced weather shocks on a regional and local level provides valuable insights into the nature of disruption and adaptation. As Endfield explained in 2007, understanding resilience in the past might help increase our ability to respond to long-term changes given models that predict an increased frequency of weather shocks.Footnote 111 Since global climate changes manifest through local weather events, and communities’ experiences are an essential ingredient of understanding the effects of climate change on people’s lives, delving into the everyday experiences of drought allows us to recognize the diverse vulnerabilities and adaptive practices that existed in the past and how responses to weather shocks played out at a day-to-day level. With weather a fundamental part of the lived environment, this nuanced understanding of how Victorian and Edwardian communities experienced and adapted to drought highlights the complex assemblages of environmental, political, physical, and social factors in shaping responses to water scarcity and insecurity, providing us with valuable evidence that connect the past to our present challenges.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the anonymous reviewers for the journal for their excellent comments and the editors for their support and kindness. I am very grateful to Katherine Weikert, Lloyd Bowen, David Doddington, Adrian Healy, and Mark Williams for reading drafts, and to those attending outings of my talks on drought to the Bremen Blue Humanities Research Group, European Association for the History of Medicine and Health conference, and University College London for their perceptive comments and suggestions.