1. Introduction

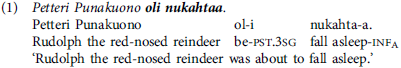

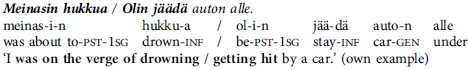

ANA grams (for Action Narrowly Averted), avertives, and frustratives are notions referring to what can be seen as a family of semantically related constructions with the meaning ‘Subject nearly/almost V-ed/Subject was on the verge of V-ing [but did not V]’ (Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998:115). The purpose of this paper is to describe in detail three verbal constructions in Finnish, which are frequently used to express a non-realised action with a meaning similar to ‘was about to’, as shown in (1)–(3):Footnote 1

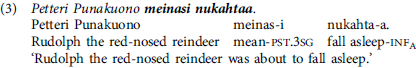

In her seminal paper on avertive constructions, Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998) considers the example Olin kaatuaFootnote 3 kadulla ‘I nearly fell (down) on the street’ an avertive use of the verb olla ‘to be’ in combination with the A-infinitive kaatua ‘to fall’ (we gloss this form as INFA). Within the Finnish grammatical tradition, the above constructions have been noticed since way back and described with terms such as propinquatives or proximatives (Penttilä Reference Penttilä1963, Maamies Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997, Ylikoski Reference Ylikoski2003).

The constructions found in (1), (2), and (3) can be labeled olla + INFA, olla + mAisillA Footnote 4 and meinata + INFA, for short. We have, however, restricted the investigation to the past tense uses of the auxiliariesFootnote 5 olla ‘to be’ and meinata ‘to mean, intend’, due to the fact that avertives are usually restricted to the past tense (see e.g. Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998, Hansen Reference Hansen, Bican, Klaska, Macurova and Zmrzlikova2010, Arkadiev Reference Arkadiev2019).Footnote 6 This is, of course, a consequence of the meaning of the construction itself (see Section 2), since an unsuccessfully completed event can most naturally be observed in retrospect.

For Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:137), pastness is indeed a defining trait of avertivity (see also Hansen Reference Hansen, Bican, Klaska, Macurova and Zmrzlikova2010, Arkadiev Reference Arkadiev2019, Zinner & Dowah Reference Zinner and Dowah2020) along with imminence and counterfactuality. As the analysis will show, the three constructions under investigation are not unambiguously avertive in all their uses, but avertivity is a prominent meaning for all of them and the main meaning of, at least, olla + INFA.

As stated above, the main purpose of this paper is to describe the three avertive constructions in Finnish in as much detail as possible. In order to achieve this, we use a quantitative method called collostructional analysis (Stefanowitsch & Gries Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003). As far as we are aware, there exists no systematic, corpus-based study of these constructions in Finnish as markers of avertivity.Footnote 7 In our analysis we also try to determine to what extent the three constructions, which share certain structural traits (the auxiliary olla and the INFA form, respectively), coincide in terms of meaning nuances and collocational preferences. Secondly, we situate the three constructions within the Finnish construction inventory, or constructicon, as understood within the framework of Construction Grammar (see Fried & Östman Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004, Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019, Hilpert Reference Hilpert2019); we also provide a description of the constructions, at two different levels of schematicity, by means of the nested box notation presented by Fried & Östman (Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004). Third and finally, we evaluate where on the avertive/frustrative continuum the three Finnish constructions are situated (see Overall Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017, Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019, Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023, and Section 2 for more details).

One of the advantages of collostructional analysis (CollA) is that it highlights the most important verbal collocates, or collexemes, of the construction under investigation. And collocates go a long toward determining the meaning of a construction, as indicated, among others, by Firth’s (1968:179) famous statement ‘You shall know a word by the company it keeps.’ CollA is also profoundly empirical, and thus well suited to large corpus data (Stefanowitsch & Gries Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003). Finally, the constructions we are interested in have not been investigated previously by means of CollA. We are thus confident that our analyses will bring new insights into the use and semantic profiles of the three constructions.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we present, first, an overview of avertivity and avertive markers from a typological perspective (Section 2.1) before moving on to previous studies on the Finnish constructions under focus (Section 2.2). Section 3 presents the data and the methods used to analyse it, while the analysis itself is presented in Section 4. The results are discussed in Section 5, where we attempt to situate the constructions within the constructional hierarchy, or constructicon, of Finnish and offer traditional box notation characterisations of the constructions at two distinct levels of schematicity. Section 6 concludes.

2. Theoretical background

2.1 Avertivity and the functions of avertive markers

The notions avertive and frustrative refer to a family of related constructions, morphemes, or grams, expressing the non-realisation of a past situation or, more precisely, a situation that almost happened but failed to materialise (cf. Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998, Overall Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017, Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019, Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023). According to Caudal’s (2023:§6.1) definition, the avertive indicates that a ‘Subject nearly/almost V-ed/Subject was going to V [but didn’t]’. These constructions, which are expressed by different means in different languages, have been subsumed under the cover term of ‘non-realisation’ by Kuteva et al. (Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019). The terminology surrounding these forms is varied, as the following discussion will show.

In her seminal paper, Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998) makes a first attempt to describe the family of ‘almost V’ constructions from a typological point of view, relying on data from African, Amazonian, Australian, and European languages. She introduces the notion of Action Narrowly Averted (ANA), which she analyses as a gram (in the sense of Bybee Reference Bybee1985 and Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994) bearing the meaning was on the verge of V-ing, but did not V (1998:115).

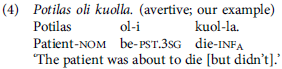

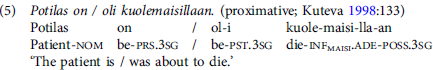

According to Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:119), there are three features which are considered ‘essential characteristics’ of ANA (Action Narrowly Averted) structures: imminence, pastness and counterfactuality, out of which ‘pastness is an essential semantic characteristic’. Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:127–129) contrasts the ANA gram with what she calls the proximative, which, on her account, refers to an imminent action but can be used in both past and non-past contexts. ANA, on the other hand, involves counterfactuality (negation) and pastness, apart from imminence (Reference Kuteva1998:132). Similarly, Arkadiev (Reference Arkadiev2019:71) distinguishes the avertive from the proximative by underlining that the ‘avertive includes counterfactuality as part of its encoded meaning’; he also notes that the avertive is restricted to the past, while the proximative is not. This contrast is exemplified in (4) and (5):

Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:145) also notes that ‘in some languages one and the same form can have, depending on context, either the ANA or the proximative function’. As we will see (Section 4.1), this is the case of the Finnish olla + mAisillA construction.

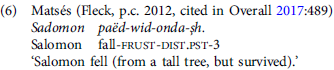

Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017) offers a typological perspective of the avertive–frustrative continuum, focusing on frustratives as an areal phenomenon of the Amazon region. For Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:479) ‘[f]rustrative is a grammatical marker that expresses the non-realisation of some expected outcome implied by the proposition expressed in the marked clause’. It ‘implies two propositions’, as exemplified by a sentence such as ‘I arrived at the town (but I didn’t accomplish what I went there for)’. For Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:480), then, the ‘frustrative indicates that some expected subsequent state of affairs (proposition q) failed to manifest’.

Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:482) makes a point of distinguishing the frustrative from what he calls the avertive/incompletive. For Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:488–89), then, an expression such as you nearly fell is a case of avertivity, whereas a canonical frustrative is found in (6), involving a morphological frustrative marker. Canonical frustratives in Overall’s sense seem to be rare in European languages, including Finnish.

Similarly to Overall (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017), Kuteva et al. (Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019) present a total of five different categories of non-realisation: avertivity, apprehensiveness, two types of frustrativity (initial and completion), and inconsequentiality. The features that distinguish the categories in Kuteva et al. (Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019:§3) are partly aspectual and partly pragmatic. Avertivity is concerned with an imminent event described as a whole (with a perfective reading), which is not completed. Initial frustrativity focuses on the initial phase of a situation, and completional frustrativity on its completion. Apprehensionality is associated with the non-fulfilment of an undesirable situation and inconsequentiality with the non-achievement of an expected outcome. In the former type, apprehensionality, the undesirable situation is avoided, while in the latter, inconsequentiality, the situation described by the verb structure is in fact achieved, but the situation as a whole does not correspond to the expected outcome. Kuteva et al.’s notion of inconsequentiality thus corresponds closely to Overall’s (Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017) canonical frustrative.

Caudal’s (Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023) model resembles the classification of Kuteva et al. (Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019) but only distinguishes four categories of non-realisation instead of five. Kuteva et al.’s (Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019) notion of apprehensionality, in which the non-realised event is undesirable, is not included in Caudal’s classification (see below). All of Caudal’s categories are considered subtypes of avertivity and his classification is based primarily on event-structural characteristics. An event can be considered either in its entirety or from within: in the first type ((a) full event structure avertive reading) the expected or desired situation fails to materialise in its entirety; in the second type ((b) preparatory stage avertive reading) the situation is initiated but the core meaning expressed by the verb (structure) is not realised. In the third type ((c) inner stage avertive reading), a situation that has been initiated does not lead to completion. The fourth type ((d) result stage avertive reading) involves a situation which is itself carried out but which ends in some atypical, unpredictable, or undesirable outcome. The ultimate interpretation of the different subtypes of aversiveness is influenced by lexical aspect as well as by other factors such as the intentionality of the subject and other contextual cues.Footnote 8

-

(a) Full event structure avertive reading: the expected or desired situation fails to materialise in its entirety.

-

(b) Preparatory stage avertive reading: the situation is initiated but the core meaning expressed by the verb (structure) is not realised.

-

(c) Inner stage avertive reading: a situation that has been initiated does not lead to completion.

-

(d) Result stage avertive reading: a situation which is itself carried out but which ends in some atypical, unpredictable or undesirable outcome.

No examples of this type were found in our data.Footnote 10

As in the previous analyses of avertives, Caudal’s model incorporates pragmatic features into the meaning carried by the constructions. This is the case of the first type ((a) full event structure) and fourth type of avertives ((d) result stage), where the non-realised event and the outcome of the realised event (fourth type) are associated with a certain attitude or set of expectations. The non-occurrence of an event and the occurrence of an event in a certain way involve negative affect (cf. Overall Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:484-488), whereas Caudal’s avertives of the second and third type can be characterised as affectively neutral for the speaker. We find Caudal’s avertive continuum the most convincing, given its conceptual clarity and the presence of the aspectual dimension of the verb situations, and hence use it as the conceptual base onto which we situate the Finnish avertive constructions.

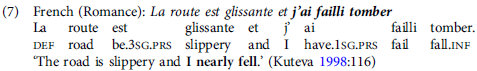

Conventionalised means of expressing avertivity can take many forms. Avertivity can be expressed by various periphrastic verb structures, i.e. sequences including a verbal element describing the event or, for example, by a copula or other grammatical element, or by lexical material (Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019:886). Periphrastic structures are found in many European languages.Footnote 11 In French, for example, the avertive consists of the verb faillir ‘to fail’, conjugated in the past tense, a failli, and the infinitive of the content verb, as in (7):

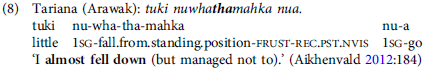

Avertivity can also be expressed morphologically by various kinds of affixes. Morphological avertivity is found, for example, in languages spoken in the Amazon (Sparing-Chávez Reference Sparing-Chávez2003, Overall Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017) and Australia (Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019, Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023). The typologically oriented study of avertives and frustratives actually originated in the analysis of indigenous languages (see Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023 for a review). For example, in the Tariana language, spoken in Brazil, avertivity/frustrativity is expressed by the affix -tha-, as in (8). In (8), the sense of immediacy is also reinforced by the form tuki ‘little’.

According to Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:138), typical elements of structures expressing avertivity are verbs of the type ‘be’ or ‘have’, forms expressing volition or purpose or a verb such as ‘fail’ expressing a more specific meaning. Like aspectual structures, verb semantics and lexical aspect are also essential for the interpretation of different types of avertive expressions.

As we have already seen, avertive constructions can express several types of avertivity, in which case the meaning of the content verb and its aspectual features play an essential role (Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019:877–879, 887, Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023). In languages where the marking of perfective and imperfective is grammatically explicit, a perfective verb is used in avertive constructions, and, overall, the situation expressed by avertives is inherently perfective (Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019:858–859). Avertive structures can also differ in terms of the kind of subject: degree of animacy, volition, and intentionality vary from language to language and from structure to structure (Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998:118–119).

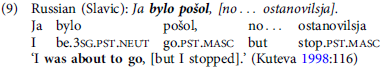

Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998:121) suggests that avertives typically are only loosely grammaticalised. Accordingly, the use of avertive markers is not obligatory but optional. The boundary between lexical and grammaticalised devices can also be fuzzy (Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998:126). On Kuteva’s account, in the early development of avertive constructions, the subject is often animate, and the meaning of being close to events can be derived from the context. A construction that expresses avertivity without the support of the co(n)text or the speech situation can thus be considered ‘stronger’ than one that requires context to support this reading. On the other hand, from a constructional point of view, avertives often occur in bi-clausal sequences (cf. Overall Reference Overall, Aikhenvald and Dixon2017:499–501, Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Aarts, Popova and Abbi2019:865, 873–874). For example, in constructions such as the Russian bylo + preterite perfect [+ no + V], the event expressed by the adversative no ‘but’ clause (in square brackets) in (9) makes it clear that the event expressed in the main clause is not realised:

As we will see, in Finnish the presence of the adversative conjunction mutta ‘but’ often reinforces the avertive reading of an expression. On the other hand, especially with the olla + mAisillA construction, contextual cues are often needed for it to be interpreted as an avertive instead of a proximative.

2.2 Avertive constructions in Finnish

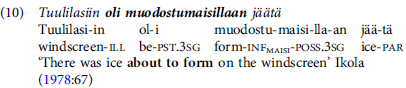

Within the tradition of Finnish grammar, the terms avertive or frustrative have not been used to characterise constructions such as olla + INFA and olla + mAisillA. Instead, they are described as expressing an event whose realisation is near (e.g. Jahnsson Reference Jahnsson1871:112, 128, Setälä Reference Setälä1952, Penttilä Reference Penttilä1963:482, 620, 416-417, Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1978:254-256, Tommola Reference Tommola, Dahl, de Groot and Tommola1992, ISK:§1521), i.e. proximative in Kuteva’s terms. In the Finnish tradition, the meaning ‘close to the event’ has been called propinquity (propinkvatiivisuus). The meaning of the two structures mentioned above has been described in the literature precisely through the notion of propinquity, and few previous accounts address the question of what implications the structure carries with respect to the occurrence of the event, or whether it carries any such implications at all. For example, according to Ikola (Reference Ikola1978:67), the structure in (10) leaves the realisation open to interpretation:

Both Maamies (Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997) and Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003:12) explicitly consider the structure olla + mAisillA to be propinquative, whereas Kuteva (Reference Kuteva2001:80, 97) considers it an avertive. Maamies (Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997:37) and Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003:28) draw attention to the semantics carried by the content verb of the structure: the stem verb of the -mAisillA form in the propinquative sense often expresses a sudden change of state and is usually momentary in aspect and thus perfective. According to Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003), stem verbs are usually intransitive, typical examples being ‘to die’, ‘to fall asleep’, ‘to fall down’, and ‘to crack’.

The structure olla + INFA, on the other hand, appears more clearly as an avertive. Previous research on Finnish cites the construction as an example of the expression of non-realisation (see Ylikoski Reference Ylikoski2003:12, ISK:§1521). Although non-realisation is not always mentioned, the structure is often equated with the structure olla vähällä + INFA ‘to be close to V (i.e. almost V)’ (Penttilä Reference Penttilä1963:620, Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1978:254, Tommola Reference Tommola and Dahl2000:663). Because of this parallelism, the interpretation of the olla + INFA construction is inevitably avertive, since the adverb vähällä ‘nearly’ implies that the situation is not realised.

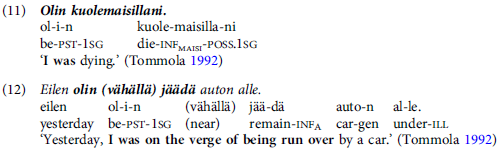

Tommola (Reference Tommola, Dahl, de Groot and Tommola1992, Reference Tommola and Dahl2000:663) draws attention to the temporal form of the constructions olla + INFA and olla + mAisillA. According to Tommola, both structures imply non-realisation when olla is in the past tense, as in (11) and (12). In neither example does the situation (dying and being hit by a car) actually take place.

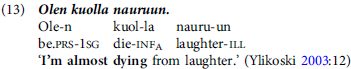

Kuteva (Reference Kuteva2001:97) also considers only the past tense use of the olla + INFA construction as an avertive. Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003:12), however, notes that it is possible to interpret even the present tense structure shown in (13) as an avertive; it is clear from context that dying of laughter is not realised.

It might thus be possible to consider that olla + INFA has become grammaticalised to express avertivity irrespective of tense.Footnote 12

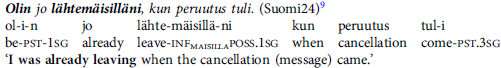

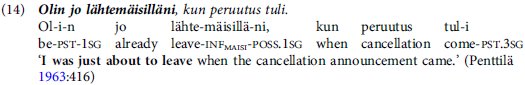

More generally, it should be noted that not only the tense of olla, but also the semantics of the main verb and the overall contextual meaning of the expression are essential factors in the avertive interpretation of the constructions olla + INFA and olla + mAisillA. In example (13), the expression involves a first person subject and can thus hardly be interpreted as anything other than an avertive. The interpretation can also be influenced by the broader sentence context: the avertive reading is evident, for example, when a subordinate clause expresses the interruption of the situation. In (14), the cancellation of plans or something else causes the departure not to take place:

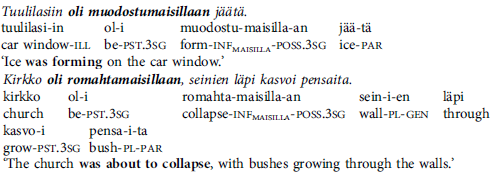

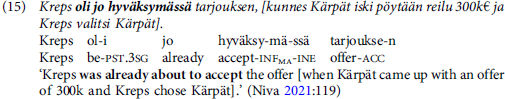

The structure olla + mAisillA further resembles a number of structures involving the mA- infinitive form (e.g. Penttilä Reference Penttilä1963:620, Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1978:256), which can acquire different degrees of proximativity/avertivity. A very common structure is olla + mAssA, which expresses, among other things, progressivity and, in the context of a momentary stem verb, propinquity (e.g. Tommola Reference Tommola and Dahl2000). Similarly to olla + mAisillA, this structure can be used to invoke avertive readings (cf. Niva Reference Niva2021:119), as in (15):

On the other hand, olla + mAssA probably involves the same type of overall meaning as olla + mAisillA, that is, the interpretation can involve the realisation of the situation. For example, the expression Loppumetreillä näin, että olin voittamassa ‘In the final metres I saw that I was about to win’ (ISK:§1520) most probably means that the subject actually won.

The meanings of the constructions olla + mAssA and olla + mAisillA are further connected by the fact that, when the stem is a punctual verb, both can ambivalently express both genuine propinquity, i.e. a situation that has not yet taken place, and progressivity, i.e. a situation in which an event is in progress, but in which the situation reaches its end point only after a delay, as in an expression such as Lentokone on laskeutumassa/laskeutumaisillaan ‘The plane is about to land/landing’ (see Markkanen Reference Markkanen1979:69–70).

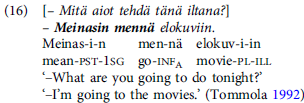

The structure meinata + INFA, finally, differs from olla + INFA and olla + mAisillA in a couple of ways. First, its auxiliary is the verb meinata ‘to mean, intend’ instead of ‘to be’. The verb itself is often considered somewhat colloquial, partly due to its loan origin from the Swedish verb mena ‘to mean’ (e.g. Tommola Reference Tommola, Dahl, de Groot and Tommola1992). Second, as can be inferred from the semantics of the verb, the construction with meinata can be used to express the intent of the subject. According to Tommola (Reference Tommola, Dahl, de Groot and Tommola1992), meinata + INFA can express present intent not only in the present tense but also in the past tense, as shown in (16):

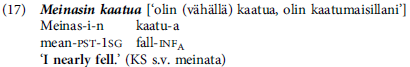

The literature does not really take a position on whether the structure with meinata in the past tense implies the non-realisation of the event or not. However, it has been noted that meinata + INFA can express that something is or was about to happen (Paunonen Reference Paunonen2000:632; KS s.v. meinata), as in (17), which is ambiguous between avertive and proximative readings:

In the dictionary Kielitoimiston sanakirja (KS, s.v. meinata), the avertive meaning of meinata + INFA is expressed through paraphrases such as olla (vähällä) + INFA ‘to be close to V’ and olla + mAisillA. As with the structures olla + INFA and olla + mAisillA, verb semantics and the overall interpretation of the expression in context have an effect on the interpretation of an expression as an avertive or not.

3. Methods and data

The analysis presented below is a classic case of collostructional analysis as introduced by Stefanowitsch & Gries (Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003) with slight adaptations following the lines of Flach (Reference Flach2021). The term collostruction is a neologism coined by Stefanowitsch & Gries (Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003) to capture the importance of collocates for capturing the meaning and usage of a construction, understood here in terms of Construction Grammar (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2005, Reference Goldberg, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013, Fried & Östman Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004, Hilpert Reference Hilpert2019). As Gries (Reference Gries2019) notes, collostructional analysis can actually be seen as a family of distinct analyses (see Gries & Stefanowitsch Reference Gries and Stefanowitsch2004a and Reference Gries, Stefanowitsch, Achard and Kemmer2004b for two elaborations). The original collexeme analysis, introduced in Stefanowitsch & Gries (Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003), involves a mathematical test, the Fisher Yates Exact test (FYE), to calculate the probability of finding a given lexeme within the construction under focus in comparison to all other lexemes and all other constructions in the corpus. In Flach’s version of the collexeme analysis, the log-likelihood test is used instead of FYE, but the main idea remains exactly the same: ranking the top collexemes according to the strength of their association to the construction.

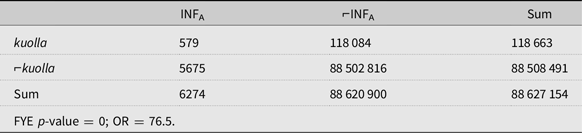

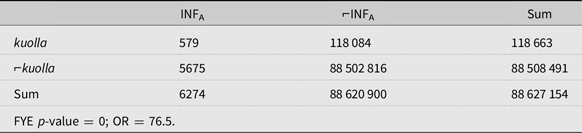

Table 1 includes four frequency counts illustrating how the collexeme analysis works for the use of the verb kuolla ‘to die’ in the olla + INFA construction, i.e. olin kuolla ‘I was about to die’. As Table 1 indicates, kuolla appears a total of 579 times in the olla + INFA construction, which in turn appears a total of 6254 times in the Suomi24 corpus (see below for details). On the other hand, in the ⌐INFA column, the values indicate the frequency of kuolla in other constructions (118 084 cases) as well as the frequency of all other verbs in all other (verbal) constructions (∼88.6 million cases).Footnote 13 The p-value of the Fisher Yates Exact test for this distribution is 0, indicating that it is very unlikely due to chance. Second, the OddsRatio value of 76.5, included in the calculation of the FYE in R, indicates that kuolla is used in the olla + INFA construction significantly more often than what could be expected (with the odds of 76.5 to 1 compared to all other verbs) (see Schmid & Küchenhoff Reference Schmid and Küchenhoff2013 and Gries Reference Gries2019 for discussion).

Table 1. Contingency table for kuolla in the olla + INFA construction in the Suomi24 corpus

The data used for the collexeme analyses performed in this paper was retrieved from the large online database known as Kielipankki (The Language Bank of Finland), which, in turn, is accessed through the Korp interface (Borin et al. Reference Borin, Forsberg and Roxendal2012). More specifically, we used the Suomi24 corpus, consisting of a large compilation of written texts retrieved from an online discussion forum called Suomi24 (‘Finland24’). The Suomi24 version we used (the searches were performed in December 2022 and February 2023) encompasses the period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2020 and includes a total of roughly 4.58 billion words. As the examples discussed below reveal, the language used on this platform is highly varied but can be characterised as informal and close to everyday language use. The Suomi24 corpus is thus well suited to analysing constructions which are typically used in everyday storytelling, where reference is often made to past events; see Niva, Silvennoinen & Wahlström (Reference Niva, Silvennoinen and Wahlström2025) for a critical evaluation of the data included in this subcorpus.

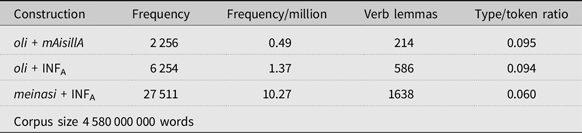

Table 2 shows the usage frequencies of the three constructions found in the corpus. Note, however, that the data set is limited in several ways. First, following the definition of avertives as referring to past situations (Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998), we only consider past tense forms of the verbs olla and meinata (i.e. ‘was’ and ‘meant to’).Footnote 14 Second, the searches involving the infinitive form (i.e. the meinasi + INFA and oli + INFA constructions) were limited to first and second person singular and plural, as well as the third person plural, i.e. olin/meinasin, olit/meinasit, olimme/meinasimme, olitte/meinasitte, and olivat/meinasivat. Third person singular subjects were excluded in order to avoid, as far as possible, the occurrence of inanimate subjects, which, especially in the oli + INFA construction, yield a considerable amount of false positives.Footnote 15 The search queries used were the following: [word = ‘oli(n|t|vat)?’] [word = ‘.*m.isill.*’] for oli + mAisillA, [sana = olin|olit|olimme|olitte|olivat + sanaluokka = verbi + morfologinen analyysi = NUM_Sg|CASE_Lat|VOICE_Act|INF_Inf1] for oli + INFA and [sana = meinasin|meinasit|meinasimme|meinasitte|meinasivat + sanaluokka = verbi + morfologinen analyysi = NUM_Sg|CASE_Lat|VOICE_Act|INF_Inf1] for meinasi + INFA.

Table 2. Frequencies of the three Finnish frustrative constructions in the Suomi24 corpus

We are of course aware that restricting the queries in this way affects the overall frequencies of the verbs occupying the infinitive slot of the constructions. In this sense, the results of our study should be treated with some caution. However, a small-scale evaluation of samples of 100 examples of oli + INFA and meinasi + INFA shows no differences in the verb lemmas occurring with third person subjects as compared to the first and second person subjects. Only the frequencies vary, given that the third person samples include a higher proportion of inanimate subjects. For example, highly general verbs such as tulla ‘to come’, mennä ‘to go’, käydä ‘to visit’ are more frequent with inanimate subjects, and their importance for the construction is thus downplayed when third person subjects are excluded.

Third and finally, given that we are dealing with a total of over 36 000 corpus cases across the three constructions, the raw data set used as input was not manually checked for avertive/proximative, or in the case of meinata, for avertive vs. intentional, readings or for doublets/repetitions. The input into the collexeme analysis thus includes some non-warranted cases. However, since the qualitative analysis only deals with the top rated verb collexemes of each construction (see below), most of the initial ‘noise’ automatically disappears from the output, and the remaining unwarranted cases can be manually checked post hoc as part of the qualitative analysis of the top verbs.

As the figures in Table 2 indicate, the three constructions are far from equally frequent in the corpus, with meinata + INFA being over ten and four times as frequent as the two constructions with olla. However, as shown in the last column, which captures the type/token ratio of the constructions, insofar as the type/token frequency can be seen as an indication of construction productivity (see Hilpert Reference Hilpert, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013:463–465), the significantly lower frequency of olla + mAisillA does not mean that it is not productive in our dataset.

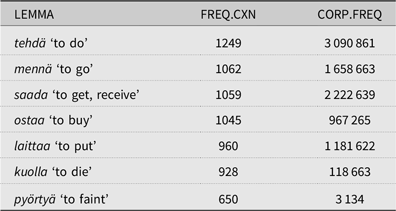

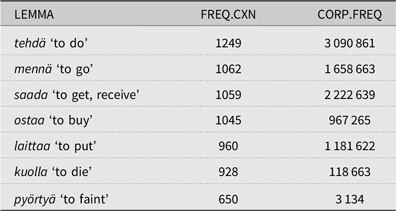

To carry out the collexeme analysis, we used the collex function of the collostructions package created for R by Flach (Reference Flach2021). This function takes as its input a table with three columns, one listing the verb lemmas of the construction to be analysed, another showing the frequency of each lemma in the construction, and the third column including the overall frequency of each verb in the corpus. Table 3 shows a seven-verb sample of the input of the meinasi + INFA construction.

Table 3. Table of verb frequencies with meinasi + INFA used as input to the collex function in R

Given that the three constructions are not equally frequent in the corpus (see Table 2), we restricted the number of verb lemmas to be included in the collostructional analysis in order for them to represent a similar portion of the whole (1 / 2256 ≈ 2 / 6254 ≈ 10 / 27 511). For the olla + mAisillA construction we included all 214 lemmas, for the olla + INFA construction we included all verbs occurring at least twice (n = 285) and for the meinata + INFA construction we included all verbs occurring at least ten times (n = 264).

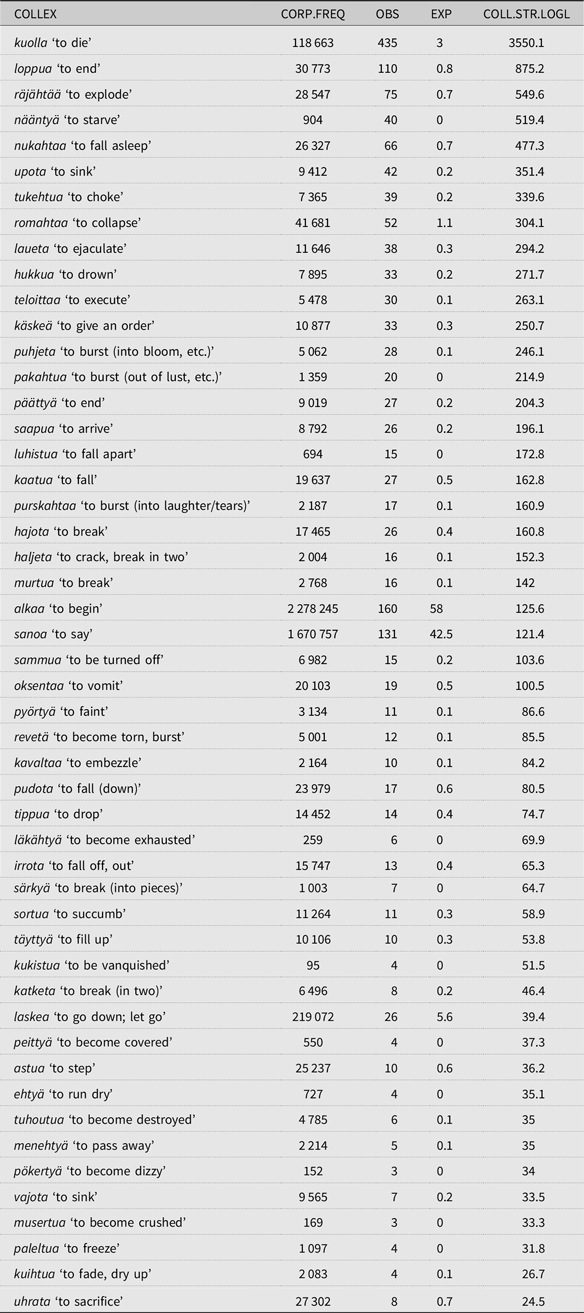

The output of the collexeme analysis (as performed by the collex() function), on the other hand, is a seven-column table indicating, for each verb, first the frequencies used in the input, i.e. its overall frequency in the corpus (CORP.FREQ) and its observed (OBS) frequency in the construction (see Table 3), followed by (i) its expected (EXP) frequency in the construction, (ii) its degree of association (ASSOC) to the construction (attraction or repulsion), (iii) the strength (COLL.STR) of this association (according to different statistical measures, such as the FYE test or log likelihood), and (iv) the degree of significance (SIGNIF) of the association (ranging from 0 to five stars). This is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Output of the collostruction analysis of the meinasi + INFA construction

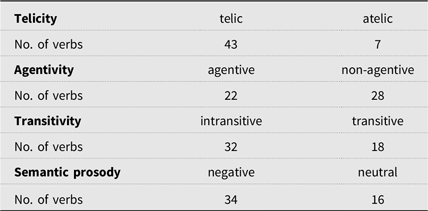

Given that the outcome of the collexeme analysis is a list of lexemes ranked according to the strength of the association, or attraction, to the construction (as shown in the COLL.STR.LOGL column in Table 4), in order to move beyond simply listing the top verbs used in each construction, we classified the top verbs semantically according to different parameters.Footnote 16

First, we classified all the verb lemmas according to their telicity, distinguishing between telic and atelic verbs (see Vendler Reference Vendler1967, ISK:§1501). Second, we marked all the verbs according to agentivity (see Yamamoto Reference Yamamoto2006:12–19), i.e. whether they combine with agentive or non-agentive subjects. Thirdly, we also recorded differences in transitivity, separating transitive and intransitive verbs. Fourth and finally, we classified the verbs according to their semantic prosody (see Olguín Martínez & Gries Reference Martínez, Francisco and Gries2024). We used two classes of semantic prosody, namely negative vs. neutral connotations, based on both verb meaning and the usage context. Thus, verbs such as kuolla ‘to die’ and oksentaa ‘to throw up’ inherently have negative connotations, whereas others, such as täyttyä ‘become ful(filled)’ and lähteä ‘to leave’, do not. On the other hand, although revetä ‘to crack, burst’ might inherently be seen as negatively charged, in context it is often combined with the noun nauruun ‘into laughter’, so it is classified as a having neutral connotations. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the meaning of a verb can change when it is used idiomatically or metaphorically.

In addition, in the detailed analysis of the different constructions we also comment on the verbs’ semantics in order to reach a more comprehensive picture of the top collexemes. These semantic characterisations arise from the corpus and are arrived at by taking into account the usage context; they constitute an attempt to capture and describe salient kinds of situations and events encoded by the verbs (e.g. detrimental verbs, verbs of communication, physical actions). In addition, we highlight the fact that a considerable proportion of the verbs make reference to punctual events.

The idea is to use the above criteria to characterise both commonalities and differences between the three constructions on a more general level as compared to the individual collexemes.

4. Analysis

In this section we report on the major findings of the collexeme analysis of the three constructions under study. In Sections 4.1–4.3 the focus lies on presenting the data and characterising each construction, including a semantic description of the main collexemes. In Section 4.4 we compare the constructions in terms of their collexemes and discuss the overall semantics of the Finnish avertive constructions. In Section 5, finally, we characterise the three constructions from the perspective of Construction Grammar, presenting a schematic illustration of the constructions as part of the Finnish constructicon. We also provide box notations based on Fried & Östman (Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004) for two members of the construction network, the schematic AUX+INFX construction and a specific usage instance of the oli + INFA construction, olin pyörtyä ‘I was about to faint’.

4.1 The oli + mAisillA construction

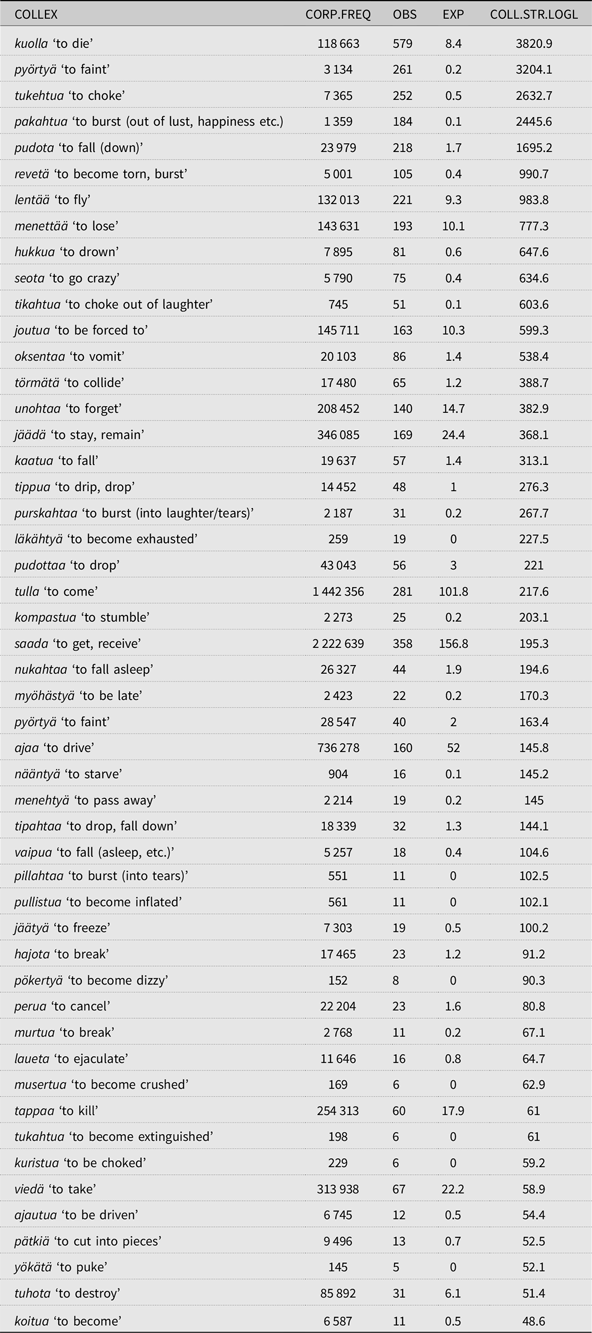

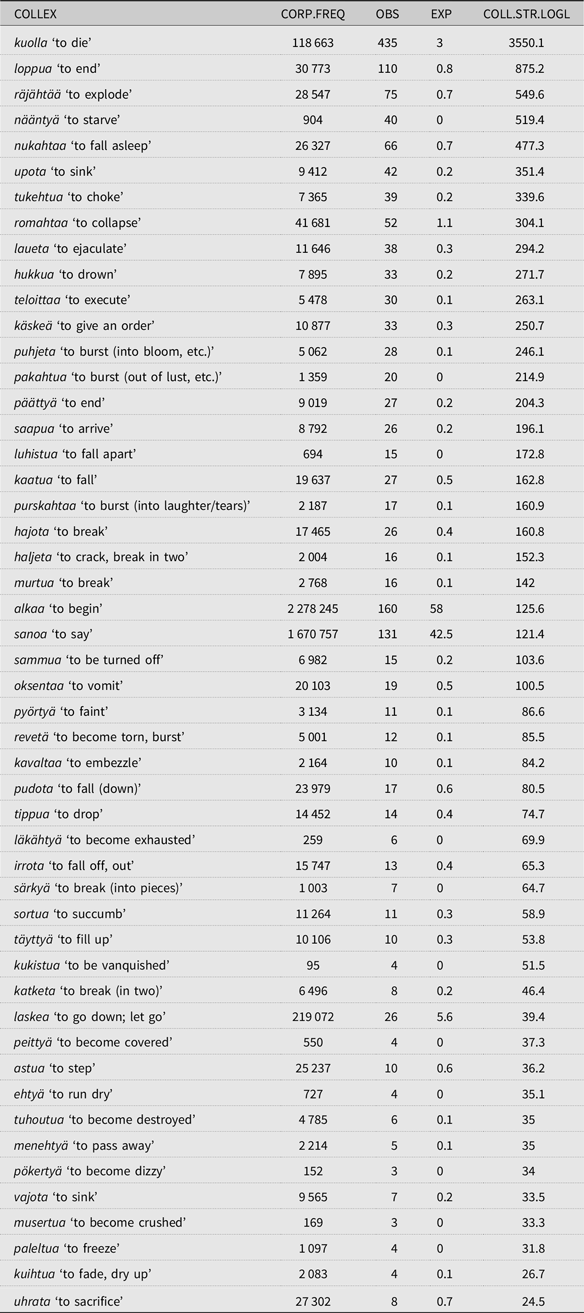

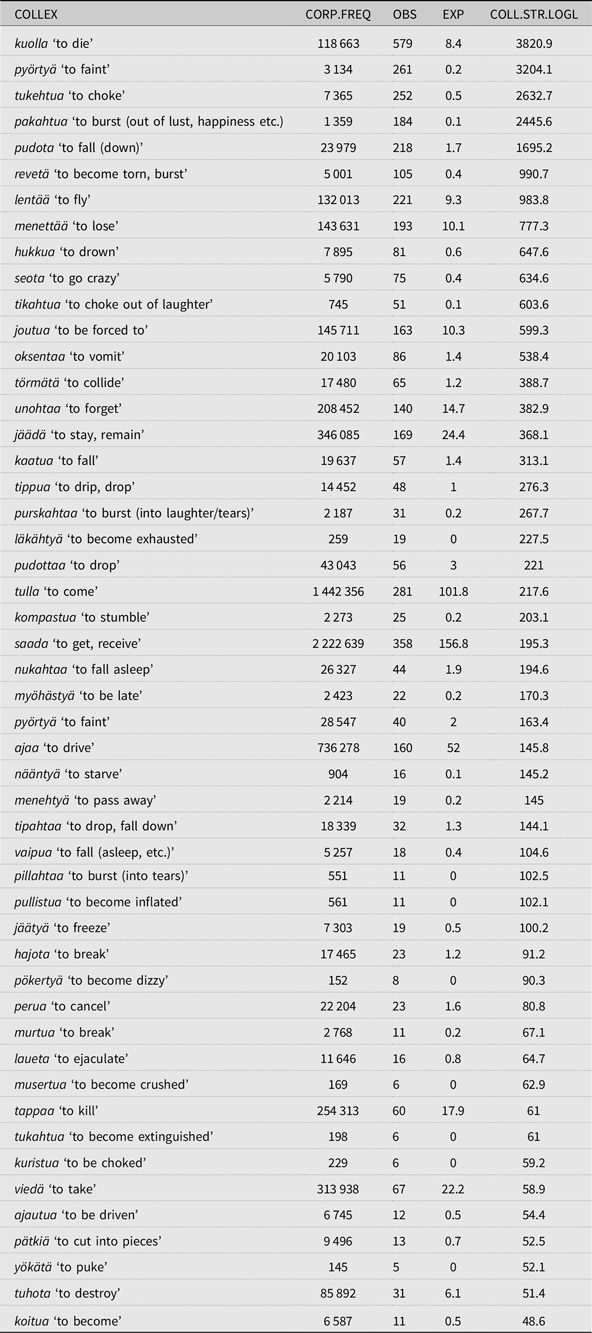

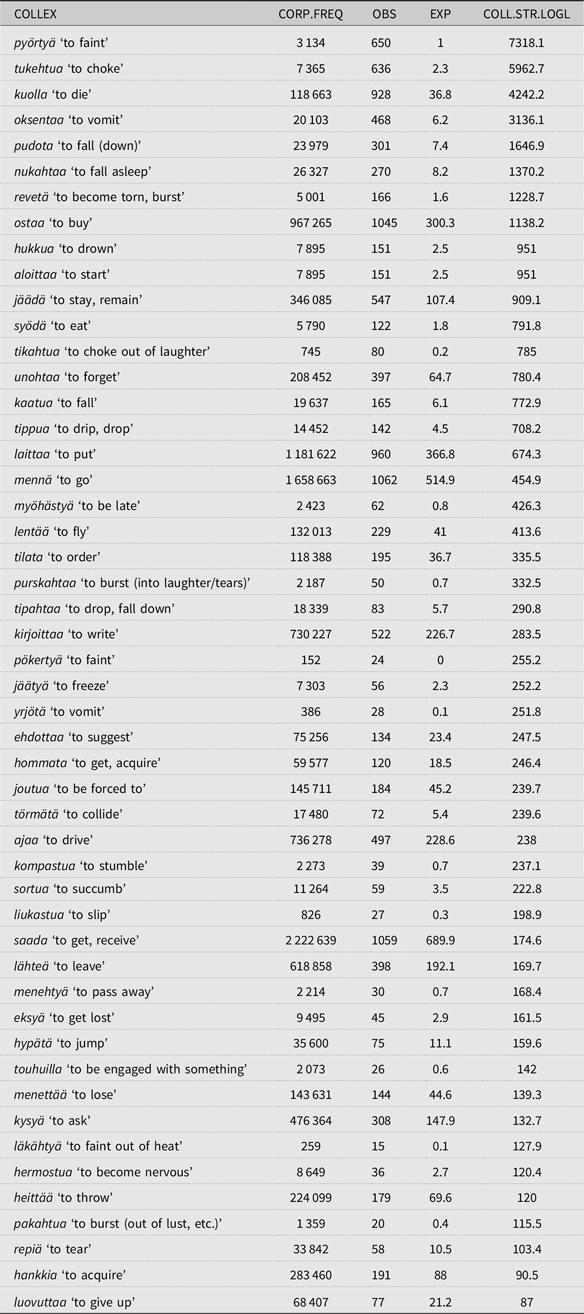

Out of the 215 verbs that are used in the oli + mAisillA construction in the corpus, 105 (49%) are significantly attracted to it. This means that, according to the statistical test performed within the collostructional analysis, they occur more frequently with oli in the -mAisillA form than could be expected based on their overall frequency in the corpus. On the contrary, 27 verbs (13%) are repelled, i.e. occur significantly less frequently than expected. In the ensuing analysis, we focus on the top 50 verbs (based on the collostructional strength) of the oli +mAisillA construction, which are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. The top 50 verbs of the oli + mAisillA construction in Finnish ranked according to collostruction strength. a

a In comparison with the total output of the collex() algorithm, we have decided to leave out two columns in our presentation, namely ASSOC, indicating whether the collexeme is attracted or repelled by the construction, and SIGNIF, showing the strength of the association/repulsion on scale from five (*****) to one (*) asterisk. All the lexemes included in Tables 5, 7, and 9 are for obvious reasons attracted to the construction, and the top 50 verbs are all associated with the highest possible degree of significance, i.e. *****.

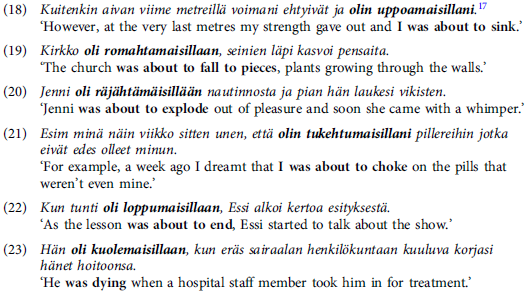

Based on Table 5, it is interesting to note that a large part of the top 50 verbs expresses either physical actions, as in kaatua ‘to fall (over), to trip’, or some kind of bodily reactions, such as nukahtaa ‘to fall asleep’. In general, most of the verbs express punctual situations. The top collexeme, kuolla ‘to die’, makes up a group of verbs linked to the semantic field of death and ceasing to exist, together with others, such as hukkua ‘to drown’, which is also a top 10 collexeme, and menehtyä ‘to pass away’. Overall, the top verb collexemes often have a negative semantic prosody, in the sense that they are associated with unpleasant, undesired situations such as dying, choking, starving, collapsing, etc. Many of these verbs could be classified as existential verbs in the field of ceasing to exist (see ISK:§459). Examples (18)–(23) illustrate the use of the most typical verbs found in the corpus.

From the point of view of avertivity, note that not all of the examples above involve a truly averted situation, in the sense that it is not clear if it eventually occurred or not. For example, as the lesson was about to end in example (22), one must assume that it eventually ended rather than went on forever. The reading is thus more that of an imminent than an averted event, and thus rather corresponds to what Maamies (Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997) and Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003) call the propinquative, or Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998) the proximative. The imminent situation in (19), where a church is on the verge of collapsing, can also be seen as lying on the border between an avertive and a proximative reading. The probable outcome is that the church did not collapse, at least not in the immediate future. Instead, what is transmitted is the church’s state of decay, and not the fact that the church was on the verge of collapsing.

The situation described in example (20) appears to be ambiguous: the verb räjähtää ‘to explode’ is used metaphorically to refer to physical pleasure. In the sexual act of this example, the subject, Jenni, is close to completion, but depending on how literally the explosion metaphor is interpreted, this either takes place or not.

On the other hand, examples (18), (21), and (23) all involve avertive readings: in (18) the subject was on the verge of sinking, but clearly did not, given that s/he is telling the story now (see Arkadiev Reference Arkadiev2019:71); also, importantly, the sinking was about to take place only in the last metres of swimming. Similarly, in (23) the subject is about to die, a reading shared by both the avertive and the proximative, but the appearance of the hospital staff member explicitly averts the undesirable event from taking place.

What these examples show is how the uses of the oli + mAisillA construction are situated along a continuum of past proximativity and avertivity. Given that avertive readings are activated only in the sentential context, based on this evidence we consider oli + mAisillA to be mainly a proximative construction rather than an avertive. This is in accordance with the analyses by Maamies (Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997) and Ylikoski (Reference Ylikoski2003) on Finnish; see also Arkadiev’s (Reference Arkadiev2019) analysis of Lithuanian.

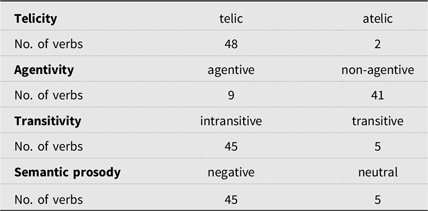

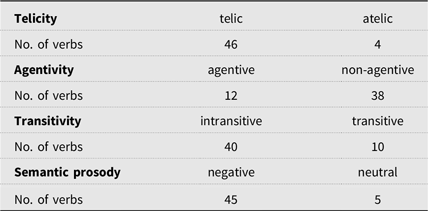

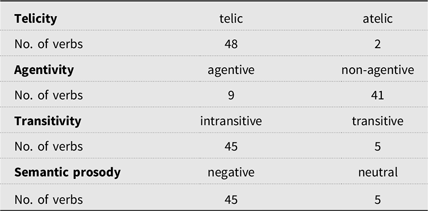

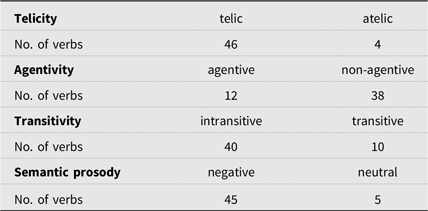

Table 6 presents the distribution of the top 50 verbs over the features we used in order to capture the semantics of the constructions. As the figures show, the distributions reveal quite clear tendencies. Firstly, over 95% of the verbs are telic, 90% are intransitive and have negative semantic prosody, and over 80% are used with non-agentive subjects. For example, all the verbs in examples (18)–(23), i.e. upota ‘to sink’, romahtaa ‘to fall apart’, räjähtää ‘to explode’, tukehtua ‘to choke’, loppua ‘to end’, and kuolla ‘to die’, express bounded situations. They are also intransitive and combined with non-agentive subjects, which are unable to control the situation described by the verb. This is congruent with the semantic prosody, since, with the exception loppua, the verbs express situations that can be considered undesirable for the undergoing subject. Note, however, that most of the verb actions involved in (18)–(23) appear to be construed as ongoing or immediate situations instead of as averted events.

Table 6. Summary of the different classifications of the top 50 verbs of the oli + mAisillA construction

All in all, the semantic characterisation of the top 50 verb collexemes of oli + mAisillA shows that this construction has a clear semantic profile: the imminent situations which are expressed by the mAisillA morpheme cluster tend to be telic events over which the undergoing subject has little or no control. This is, of course, perfectly in line with the meaning of the avertive, expressing past, imminent, yet unrealised actions. In addition, they typically have negative semantic prosody. As the discussion of the examples presented in this section show, the uses of the oli + mAisillA construction are situated somewhere between past proximatives and avertives. However, given that avertive readings are only activated in the sentential context, we propose that the oli + mAisillA construction is considered a proximative rather than an avertive (see Maamies Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997, Ylikoski Reference Ylikoski2003).

4.2 The oli + INF A construction

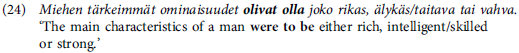

Turning to the oli + INFA construction, we find that 149 out of 285 (52%) different verbs are significantly attracted to this construction. This is a very similar proportion to the one observed for oli + mAisillA. On the other hand, 68 verbs are repelled (24%), i.e. used significantly less often than expected, and this figure is much higher than the corresponding proportion of oli + mAisillA. This is probably at least partly a question of the overall frequency of the two constructions; the more frequent the construction, the more often a verb needs to be inserted in it in order for the association to become significant. Another potential explanation is the existence of homophonous constructions, i.e. where the oli + INFA combination is not an example of the avertive but of some other construction. This is what happens with the combination olivat olla ‘were to be’ in (24), where the infinitival clause functions as the subject.Footnote 18 Among the other top verbs which are repelled we find frequent verbs such as pitää, a highly polysemous verb with meanings such as ‘to have to, need, must’, ‘to like’, and ‘to hold’ (KS, s.v. pitää), alkaa ‘to start’, antaa ‘to give’, and ottaa ‘to take’.

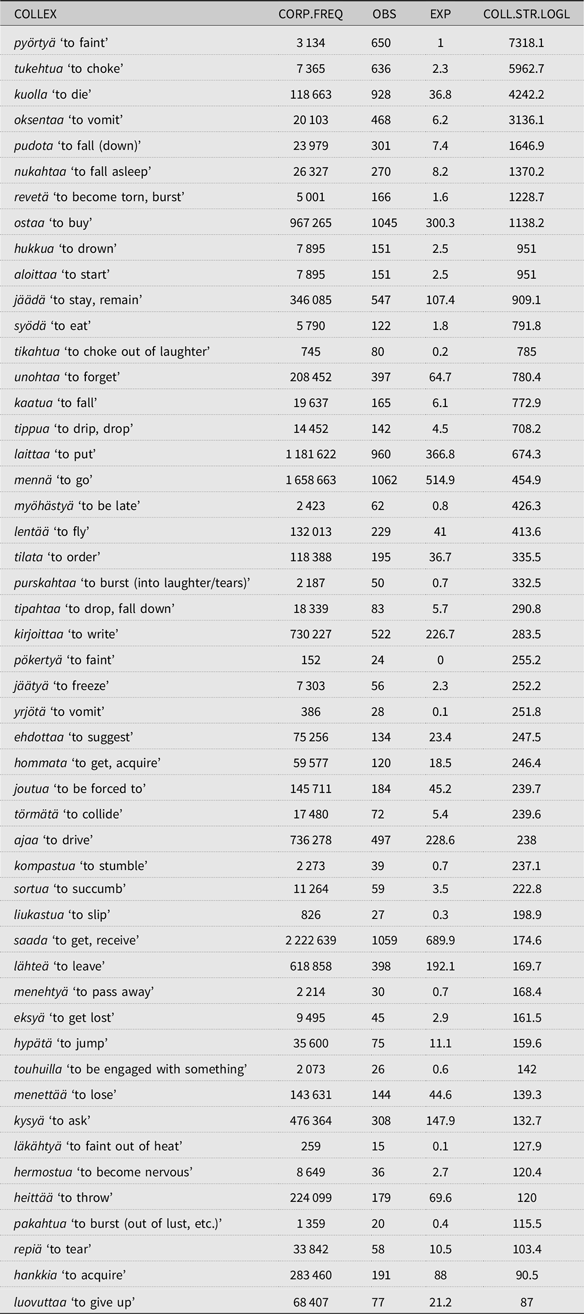

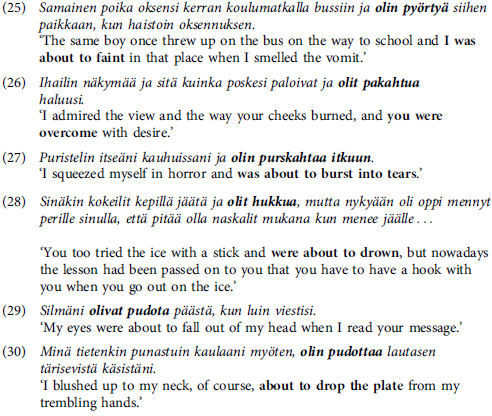

The top 50 verbs of the oli + INFA construction are listed in Table 7, ordered according to collostructional strength, shown in the rightmost column.

Table 7. The top 50 verbs of the oli + INFA construction in Finnish ranked according to collostruction strength

As was the case with the oli + mAisillA construction, kuolla ‘to die’ is the top verb of the oli + INFA construction. Other verbs related to dying among the top 50 collexemes are the intransitives hukkua ‘to drown’, menehtyä ‘to pass away’, and transitive tappaa ‘to kill’. Among the top collexemes we also observe a number of verbs expressing bodily reactions, such as pyörtyä ‘to faint’, tukehtua ‘to choke’, pakahtua ‘to burst (out of lust, happiness)’, and tikahtua ‘to succumb from thirst/heat, etc.’. Note that many of the bodily reaction verbs include both the detransitivising affix -U- and the momentaneousness affix -AhtA- (tukehtua, pakahtua, tikahtua, läkähtyä, tukahtua Footnote 19 ), or one of them (purskahtaa ‘to burst (into)’, nukahtaa ‘to fall asleep’, pillahtaa ‘to burst into tears’, and pyörtyä ‘to faint’, nääntyä ‘to starve’, jäätyä ‘to freeze’, pökertyä ‘to become dizzy’). A second group of verbs indicating some sort of downward movement can also be identified, as in pudota ‘to fall’, kaatua ‘to trip, fall’, tippua ‘to drip, drop’, pudottaa ‘to drop’, kompastua ‘to stumble’, and tipahtaa ‘to drop, fall down’. Interestingly, this group of verbs includes two verb pairs, i.e. intransitive pudota ‘to fall’ and transitive pudottaa ‘to drop’, on the one hand, and tippua ‘to drip, drop’ and tipahtaa ‘to drop, fall down’, involving the momentaneous suffix AhtA.

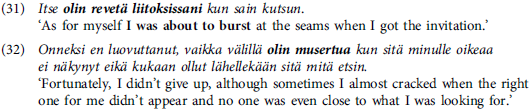

All in all, typically averted actions in the oli + INFA construction appear in contexts where some external force or condition influences the non-agentive (undergoer, experiencer) subject in a negative way, creating a sense of nearly going under, bursting, exploding, etc., as shown by examples (25)–(30).

Contrary to oli + mAisillA, examples (25)–(30) consistently involve averted events. The avertive reading thus seems to be an essential part of the construction. In (28) the avertive reading is strengthened by the adversative conjunction mutta ‘but’, showcasing how the avertive is often realised in bipartite structures. Something similar occurs in (29), where the presence of the temporal conjunction kun ‘as, when’ introduces a subordinate clause indicating the cause of the reaction. Finally, note that although pudottaa in (30) is a transitive verb, the subject can hardly be considered agentive; rather, an external force influences the subject to the point of almost losing its agentivity and control.

On the other hand, all the verb situations are construed as imminent, as was the case with oli + mAisillA in examples (18)–(23). Examples (25)–(30) also show that the usage context of the oli + INFA construction coincides with oli + mAisillA in typically involving negative semantic prosody and non-agentive subjects (undergoers) lacking control over the event they experience; in addition, the verbs are intransitive and telic. These tendencies are presented in numerical format in Table 8.Footnote 20

Table 8. Summary of the different classifications of the top 50 verbs of the oli + INFA construction

Furthermore, the data shows the presence of a couple of idioms, such as silmät olivat pudota päästä ‘the eyes were about to fall out of her/his head’ and purskahtaa itkuun/nauruun ‘to burst into tears/laughter’. Another observation is that the examples showcase a vivid use of this construction in colloquial texts (see especially example (26), alluding to a situation involving sex). Finally, one can observe several examples of different kinds of metaphorical uses of concrete verbs used in a bodily or mental sense, as illustrated in (29). Two further examples are presented in (31) and (32). The first one involves the verb revetä, one of many verbs sharing the meaning ‘to burst, break into pieces’. In (31) revetä is used metaphorically to express emotional overload, here, exceptionally, of a positive nature, whereby the human body cracks at its seams. Another telling example is the use of the verb musertua ‘to be crushed’ in (32), where this physical verb refers to a mental meltdown.

All in all, the analysed data draw a picture of the oli + INFA construction as semantically very similar to oli + mAisillA, with the main difference that it is more frequent and also less ambiguous; there are few non-avertive uses, so oli + INFA can clearly be seen as a conventionalised avertive marker in Finnish.

4.3 The meinasi + INF A construction

With a total of 27 511 cases found in the corpus, meinasi + INFA is by far the most frequent of the three constructions, with ten times more cases than oli + mAisillA and four times more than oli + INFA. Meinasi is also combined with the greatest number of different verbs in the infinitive slot, a total of 1638. This is almost three times as many as the oli + INFA and more than seven times as many as the oli + mAisillA construction (see Table 2). However, as indicated by the figures in Table 2, the type/token ratio of 0.06 is actually somewhat lower than for the two constructions with oli.

In light of the collostructional analysis, we find that 123 out of 264 (50%) different verbs are significantly ‘attracted’ to the meinasi + INFA construction. This is a very similar figure as compared to both the oli + mAisillA and oli + INFA constructions. On the other hand, as many as 90 (42%) of the co-occurring verbs are repelled. This is an increase of almost 20 percentage points as compared to oli + INFA. This last figure is clearly the highest among the three constructions and supports the observation made above (Section 4.2). That is, since meinasi + INFA is the most frequent of the three constructions, many verbs which do occur in it are not particularly attracted to it. The repelled verbs are highly frequent verbs, such as olla ‘to be’, pitää ‘to have to, need, must; to like; to hold’, näyttää ‘to show’, lukea ‘to read’, etc.

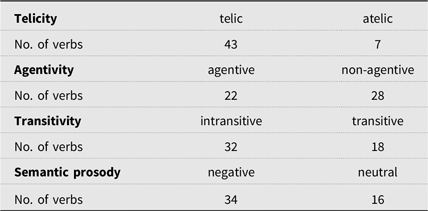

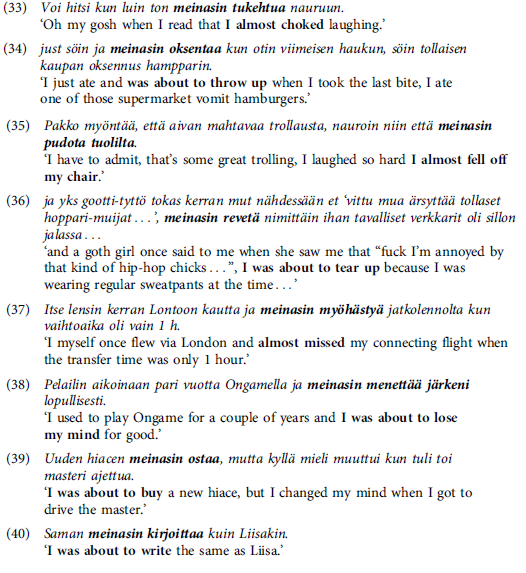

Table 9 lists the top 50 verbs of the meinasi + INFA construction.

Table 9. The top 50 verbs of the meinasi + INFA construction in Finnish ranked according to collostruction strength

As Table 9 shows, the top collexeme is pyörtyä ‘to faint’, which makes up a group of verbs expressing bodily reactions, involving others such as tukehtua ‘to choke’, oksentaa ‘to vomit’, and tikahtua ‘to choke out of laughter’. There are also, as was found with oli + INFA, a series of verbs referring to downward motion, such as pudota ‘to fall’, kaatua ‘to fall’, tippua ‘to drip, drop’, tipahtaa ‘to drop, fall down’, kompastua ‘to stumble’, sortua ‘to succumb’, and liukastua ‘to slip’. All these verbs mainly show a negative semantic prosody, as is also the case with other top collocate verbs such as unohtaa ‘to forget’, myöhästyä ‘to be late’, and menettää ‘to lose’.

Contrary to the previous two constructions, among the top collexemes of meinasi we find several transitive verbs which are used with agentive subjects. Among these are ostaa ‘to buy’, tilata ‘to order’, hommata ‘to get, acquire’, and hankkia ‘to acquire’, referring to the acquisition of something. Another group of verbs are kirjoittaa ‘to write’, ehdottaa ‘to suggest’, and kysyä ‘to ask’, belonging to the domain of interpersonal communication.

Examples (33)–(39) illustrate the use of the meinasi + INFA construction with its most salient verb collexemes:

The presence of a number of acquisition and communication verbs, which are used with active, agentive subjects among the top collexemes of meinasi is probably due to the fact that its original meaning involves a sense of intention (meinata ‘to mean, to intend, to have in mind’; see KS, s.v. meinata). Changing your mind when making a purchase is a frequent situation in everyday life, which might explain why the meinasi + INFA construction is so frequently used with verbs like buying, ordering, acquiring (see (39)). The same applies to the example in (40), where the process of writing is interrupted by the subject.Footnote 21

Importantly, from the perspective of the kind of avertivity of the meinasi + INFA construction, examples (39) and (40) illustrate how the use of verbs such as ostaa and kirjoittaa involving an agentive subject gives rise to an avertive reading of type (b) according to Caudal’s classification (see Section 2.1). In both examples, the meaning conveyed is that of an intention to buy and to write. In (39), the subordinate clause introduced by mutta ‘but’ makes it very explicit that the subject does not go on buying a Hiace. In (40), on the other hand, the non-realisation of the intended action is conveyed simply by the construction. Although meinasi + INFA has a conventionalised use as a marker of avertivity (as in examples (33)–(38)), examples (39) and (40) show that, with agentive subjects, what is averted is, strictly speaking, the intention, whereby the situation itself is only averted by entailment.

The above contrasts with the remaining six examples (33)–(38), which all involve non- agentive subjects and are interpreted as type (a) avertives (according to Caudal Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023; see Section 2.1). The association of the avertive reading with intransitive verbs bearing negative semantic prosody and non-agentive subjects is due to the fact that the undesired situations which are averted, being late, losing, getting hit by a car, and so on, are something the subjects do not control but instead are probably happy to escape.

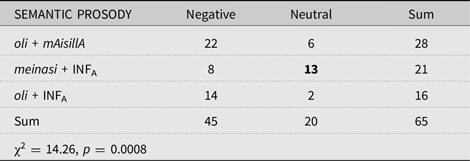

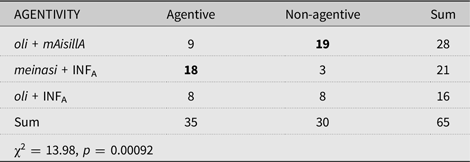

As Table 10 shows, it seems to be characteristic of the meinasi + INFA construction as compared to the oli + INFA and the oli + mAisillA constructions that a larger amount of the top collexemes have a neutral semantic prosody (e.g. acquisition and communication verbs). In addition, strongly associated acquisition verbs such as ostaa ‘to buy’, hommata ‘to get, acquire’, tilata ‘to order’, saada ‘to get, receive’ are mainly used as transitives and, with the exception of saada, have agentive subjects; other transitive verbs are aloittaa ‘to begin’ and syödä ‘to eat’. Many of these verbs lack the negative semantic prosody which are typical of the averted situations (only 68% for meinasi). This can be related to the intentionality reading which is typical of meinasi.Footnote 22

Table 10. Summary of the different classifications of the top 50 verbs of the meinasi + INFA construction

All in all, apart from the notable presence of verbs with neutral semantic prosody used with agentive subjects, the core of meinasi + INFA is quite similar to the other two constructions: the majority of the top collexemes refer to telic, punctual events in which a non-agentive subject avoids experiencing an undesirable situation.

4.4 Overview and comparison of the three constructions

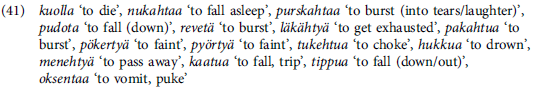

All in all, the analysis of the top 50 verbal collocates of the three constructions reveals a total of 100 different collexemes (100/150 = 67%). This means that there is a considerable amount of variation in the top collexemes of the three constructions. In fact, only 15 of the 100 collocate verbs occur among the top 50 of all three constructions. These 15 verbs, which occur in the top 50 of all three constructions, can be considered to constitute the lexical core of the family of Finnish avertive constructions. They are listed in (41):

All these verbs are intransitive and have negative semantic prosody. Apart from one activity (oksentaa ‘to vomit’), 14 refer to telic, punctual events and combine with non-agentive, undergoer-like subjects, and 9 have the detransitivising affix -U-. Three of them are verbs related to dying (hukkua, kuolla, menehtyä), three express downward motion (pudota, kaatua, tippua), and eight express bodily reactions (nukahtaa, purskahtaa, läkähtyä, pakahtua, pökertyä, pyörtyä, tukehtua, oksentaa). The common core of the three constructions thus seems quite clear: the Finnish avertive constructions express the non-realisation of undesired situations over which the undergoing human subject has little or no control. The core verbs thus situate the Finnish constructions in the top part of Caudal’s (Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023:12) avertivity/frustrativity continuum, corresponding to his full event structure avertive reading (type (a); see Section 2.1).Footnote 23

On the other hand, when contrasting the three constructions there are also some notable differences. For example, apart from the shared 15 verbal collexemes there are 20 more verbs which are shared by two of the three constructions. Of these, 17 are punctual, bear negative semantic prosody and combine with non-agentive subjects; 16 are intransitive, and 9 have the morpheme -U-. Semantically they are highly similar to the core verbs. Comparing the three constructions, however, one can observe that only 1 of these 20 verbs is shared by meinasi and oli + mAisillA, 6 are shared by oli + INFA and oli + mAisillA, and 13 are shared by meinasi + INFA and oli + INFA.

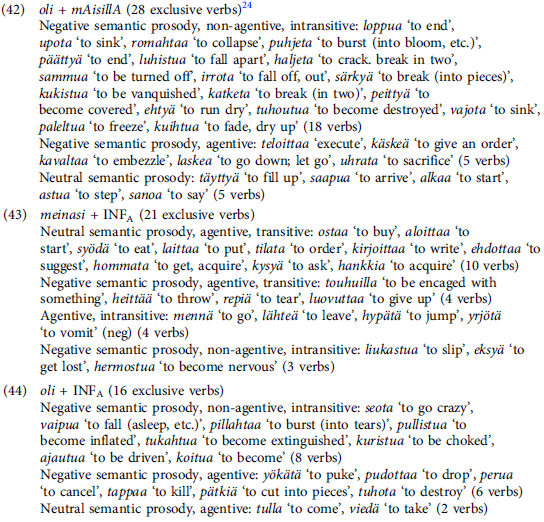

From this perspective, then, oli + mAisillA stands out as the most distinct of the three constructions, sharing 22 of its 50 top collexeme with the other two constructions, and having 28 verbs which are exclusive to its own top 50 (i.e. 56%). Meinasi + INFA occupies the second position in this comparison, sharing 13 verbs with the oli + INFA construction and 1 with oli + mAisillA (apart from the 15 common ones). This means that 21 (42%) of the top 50 verbs are exclusive to meinasi + INFA. The oli + INFA construction, finally, only has 16 exclusive verbs. The exclusive verbs of each construction are listed in (42)–(44):

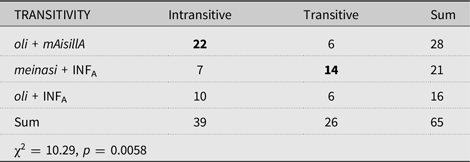

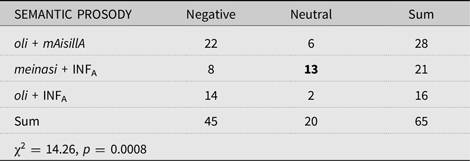

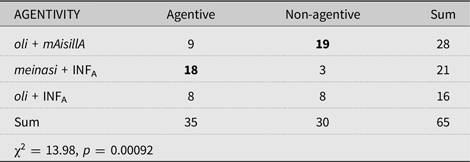

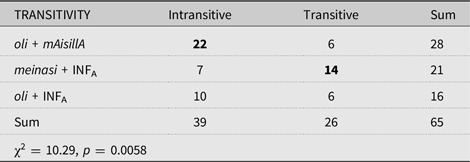

The verbs listed in (42)–(44) are organised so that they reflect the figures presented in Tables 11–14, which illustrate their distribution across the different classifications (semantic prosody > agentivity > transitivity > and telicity). As the figures in Tables 11–14 show, three of the verb features contribute to distinguish the three constructions: semantic prosody, agentivity, transitivity. The distribution of telicity (Table 14) is not significantly distinct across the three constructions. As pointed out above, this is, of course, a natural consequence of the notion of avertivity, which shows a marked preference for telic verbs.

Table 11. Distribution of the semantic prosody of the top 50 non-shared verbal collexemes across the three constructions

Table 12. Distribution of agentivity of the top 50 non-shared verbal collexemes across the three constructions

Table 13. Distribution of transitivity of the top 50 non-shared verbal collexemes across the three constructions

Table 14. Distribution of telicity of the top 50 non-shared verbal collexemes across the three constructions

Starting with oli + mAisillA, Tables 11, 12, and 13 and the verbs listed in (42) show that its exclusive verb collexemes are predominantly non-agentive, intransitive verbs (68% and 79% in Tables 13 and 14, respectively) with negative semantic prosody (79% in Table 12). The preference for non-agentive, intransitive verbs is what sets oli + mAisillA apart from the other two constructions. Compared to the top 50 collexemes, the exclusive verbs confirm the overall characterisation of oli + mAisillA as the construction most clearly restricted to intransitive, non-agentive verbs carrying negative semantic prosody.

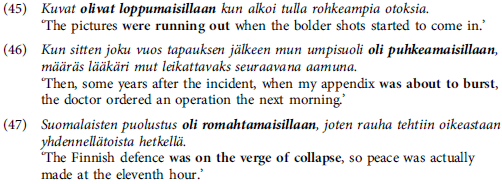

Examples (45)–(47) illustrate the use of three of the top ranked verbs which are exclusive to oli + mAisillA. As the translations reveal, the verbs loppua ‘to end’, puhjeta ‘to burst’, and romahtaa ‘to collapse’ are all intransitive, punctual verbs construed with non-agentive (patient) subjects and, with the exception of loppua, refer to negative situations.Footnote 25 On the other hand, the examples also indicate how the verb situations are mainly seen as imminent rather than as averted. This appears to be typical of the oli + mAisillA construction, which has been classified as a proximative, or propinquative, in earlier research (see Maamies Reference Maamies, Lehtinen and Laitinen1997 and Ylikoski Reference Ylikoski2003). However, it is also clear from the sentence context that the pictures did not run out in (45), that the subject’s appendix did not burst in (46), and that the Finnish defence did not (quite) collapse when peace was made in (47). These examples can thus be considered avertives, corresponding to Caudal’s (Reference Caudal and Jaszczolt2023) preparatory stage avertive readings.

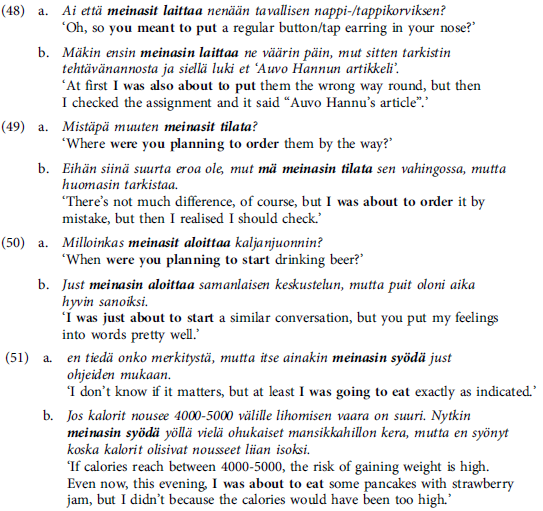

Meinasi + INFA, on the other hand, contrasts clearly with the other two constructions: eight of its 21 exclusive verbal collexemes (38%) do not carry negative semantic prosody, 18 have mainly active, agentive subjects (86%), and 14 are transitive (67%). Meinasi also has the highest proportion of atelic verbs (see Table 14). Examples (48)–(51) illustrate four of the top ranked verbs which are exclusive to meinasi + INFA, namely laittaa ‘to put’, tilata ‘to order’, aloittaa ‘to begin’, and syödä ‘to eat’. As these examples show, with meinasi not all the uses involving verbs with active subjects are avertives. Instead, depending on the context, the interpretation may be simply that of intention, that is, the verb situation is, of course, non-realised, but not averted. This is what the sentences in (48a)–(51a) indicate, in contrast to the b sentences, where the verb situations are explicitly averted by the adversative conjunction mut(ta) ‘but’. The uses in (48b)–(51b) express mainly avertives with a full event structure reading, or, perhaps, in (51b), an inner stage avertive reading.

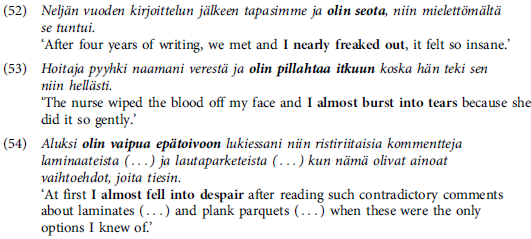

Finally, the 16 exclusive verb collexemes of the oli + INFA constructions have predominantly negative semantic prosody (88%), but they can be either intransitive or transitive (10:6) and combine with both agentive and non-agentive subjects (8:8). In short, the verbs which are exclusive to oli + INFA are very similar to those of oli + mAisillA, the main difference lying in a greater preference of oli + INFA for negative semantic prosody (see Table 11). This finding underlines that oli + INFA is the most clearly avertive construction of the three, as examples (52)–(54) illustrate:

Indeed, in these examples, despite the absence of any adversative conjunction, the interpretation is that the verb situation is averted either completely (full event structure avertive), as with seota ‘to go crazy’ and pillahtaa ‘to burst into tears’ in (52) and (53), or before completion, as with vaipua ‘to fall (into despair)’ in (54) (inner stage avertive reading).

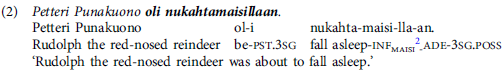

5. Overall characterisation of the Finnish avertive constructions

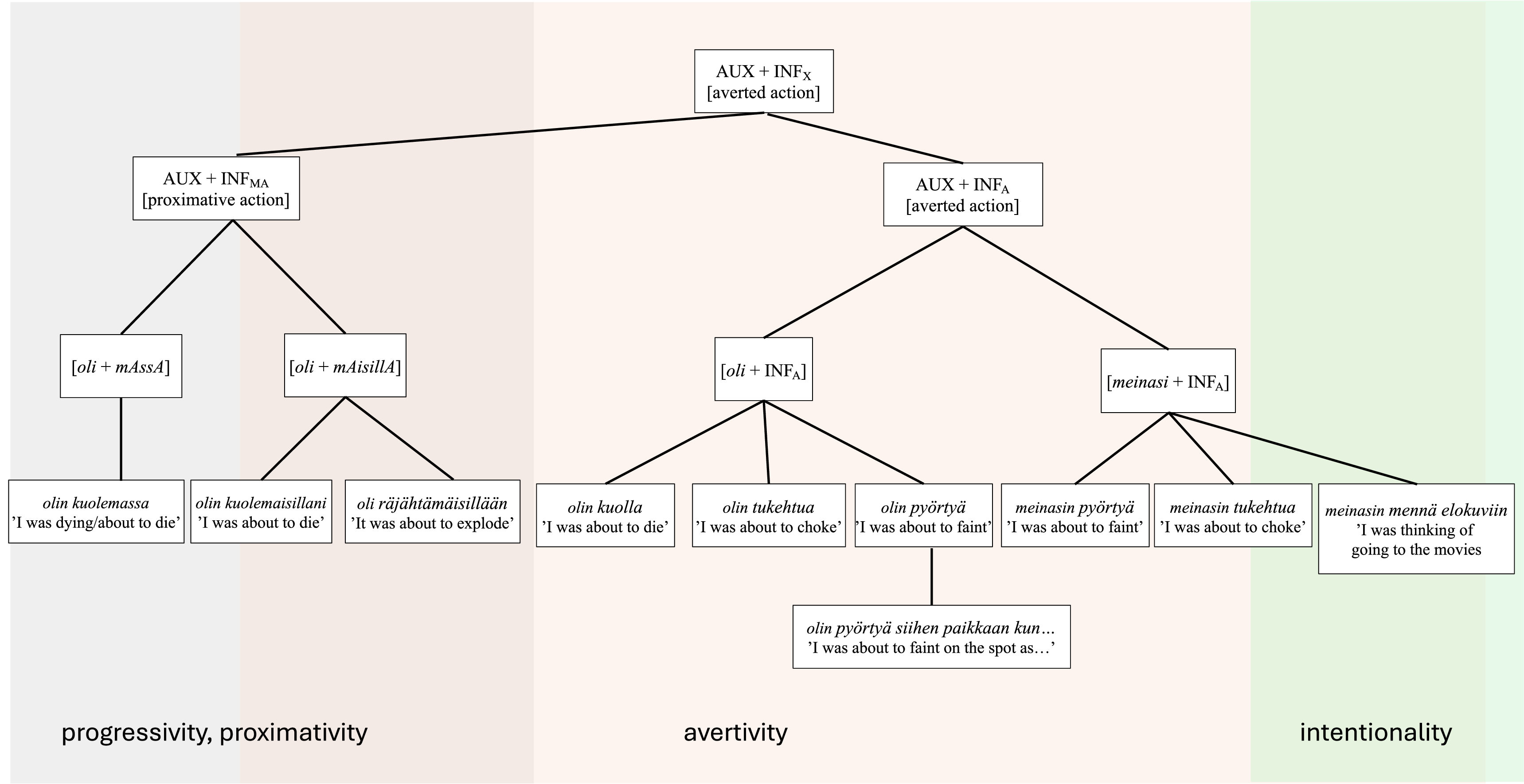

In this subsection we provide an overall characterisation of the constructions under study by illustrating how they can be situated within the Finnish constructicon, on the one hand, and with regard to each other, on the other. It is important to bear in mind that we are considering both the meaning and the form of the constructions as well as their relationship to other similar AUX + infinitive constructions in Finnish.Footnote 26 In this regard, we may first note that oli + mAisillA is related to the olla mA- + inessive case construction, e.g. olla tekemässä ‘to be doing’, which is a prominent progressive construction in Finnish (see Niva Reference Niva2021). This construction is often used with an imminent reading (Olin juuri sanomassa ‘I was just about to say’), from which the avertive reading is a potential extension: progressivity > imminence > (sometimes) avertive.

Second, the olla + INFA construction is, of course, formally related to the oli -mA-inessive case and the oli + mAisillA construction by means of the auxiliary olla ‘to be’; but olla can also be combined with other non-finite forms, such as the participle form to create the compound perfect tense form olla tehnyt ‘to have done’, the periphrastic modal construction olla tehtävä, olla mentävä ‘to have to do, to have to go’. Within the family of olla + non-finite verb, olla + INFA has become specialised as the most clearly avertive construction in Finnish. Thirdly, meinasi + INFA can be seen as a parallel to oli + INFA, involving the same INFA element but another auxiliary.

This means that the INFA form appears to make up a productive constructional schema together with auxiliar verbs, AUX + INFA. From this perspective, the introduction of meinata can be seen as an analogical extension of the avertive construction oli + INFA.Footnote 27 At what time the meinasi + INFA construction was coined and to what degree it has developed in relation to olla + INFA is, however, a matter that must be left for future research. Of course, all three constructions merit their own, detailed descriptive analysis, something we also have to leave for future endeavours.

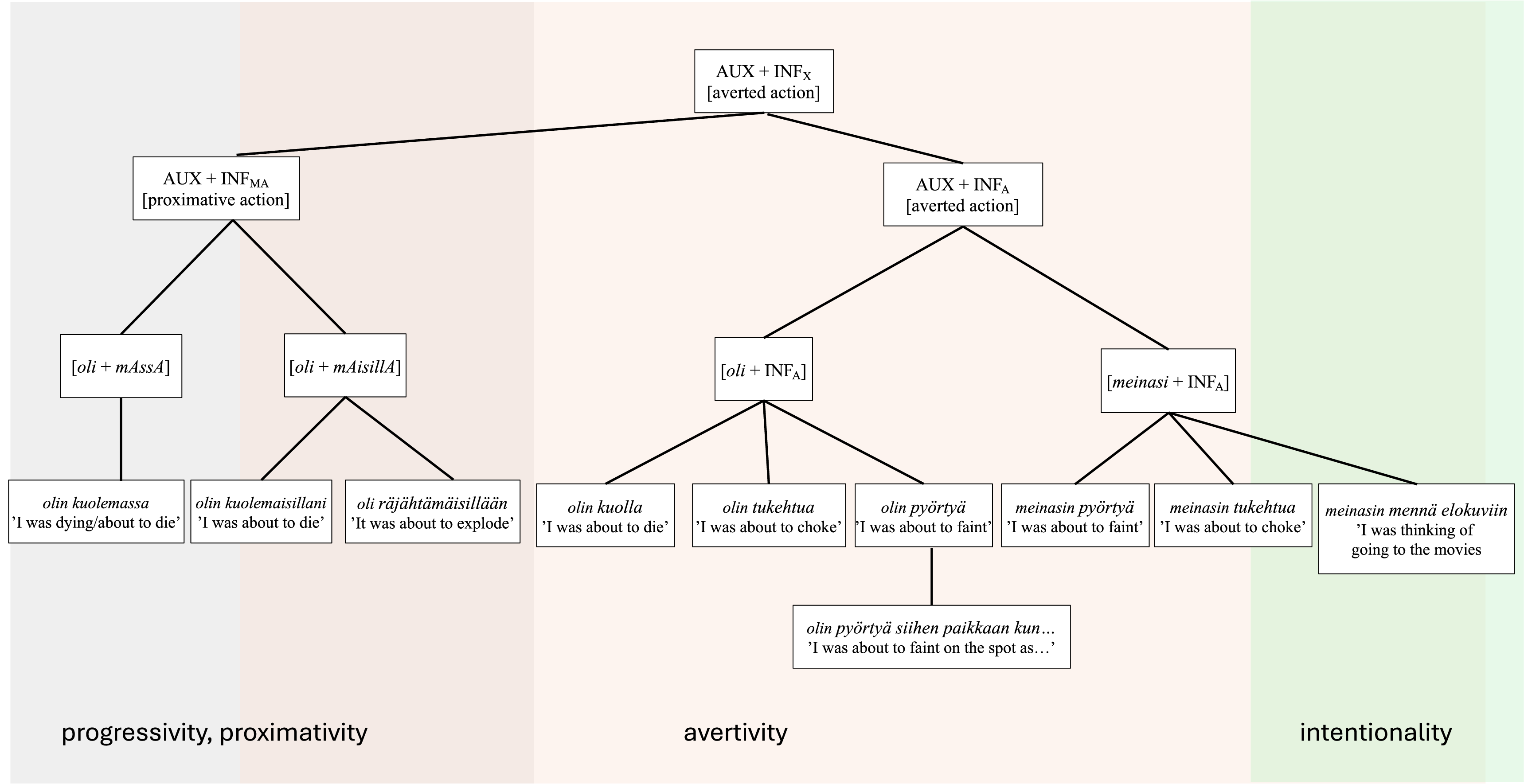

In Figure 1 we have tried to situate the three avertive constructions within both the broader constructional network (formal dimension) and the semantic domains of progressivity, proximativity, avertivity, and intentionality, considering the semantic poles of the three constructions (marked by different background colours). That is, in Figure 1 we situate the oli + mAisillA construction on the left, associating it with the progressive construction, olla mA+inessive; it frequently exhibits meanings such as proximativity/imminence, as indicated in the lower part of Figure 1. The olla + INFA construction, on the other hand, inherits its form from the more schematic AUX + INFX construction, but it is intrinsically tied to the specific meaning of avertivity. Meinasi + INFA, finally, is also an elaboration of the AUX + INFX and, secondarily, the AUX + INFA schema, but its meaning components coincide only partially with olla + INFA due to the semantic purport of meinata, which occupies the auxiliary slot and carries a meaning of intentionality.

Figure 1. Network structure of the avertive construction family.

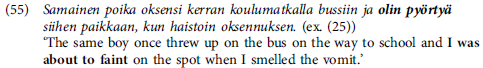

Note that the notification used in Figure 1 is meant to indicate that the expressions are all situated at the level of constructions, i.e. abstractions over contextually observed uses (constructs). The verbs used in the INFA and mAisillA slots, kuolla ‘to die’, räjähtää ‘to explode’, tukehtua ‘to choke’, pyörtyä ‘to faint’, and mennä ‘to go’ represent top collexemes, i.e. typical collocates, of the constructions, following the results of the collostructional analysis presented above. We have also included a more specific expression within the oli + INFA construction, i.e. olin pyörtyä siihen paikkaan kun ‘I was about to faint on the spot as …’ (see example (55)), in order to illustrate that there are, of course, more elaborate constructions, depending on the verb used in the INF-slot of the construction.

A final comment on Figure 1 involves the three colour shades, with the avertive notional area in the centre; this area extends left and right, towards the areas of progressivity/proximativity (left) and intentionality (right) situated on the edges. The overlap, on the left, between the dimensions of progressivity/proximativity and avertivity reflects the fact that it is impossible to decide on the schematic construction level whether a given oli + mAisillA combination has an avertive or proximative meaning. Only on the specific level of the construct, i.e. the actual usage context, is the reading disambiguated (see examples (18)–(23) in Section 4.1).

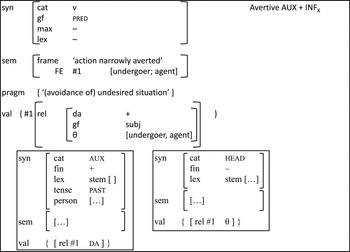

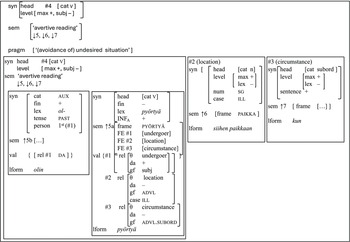

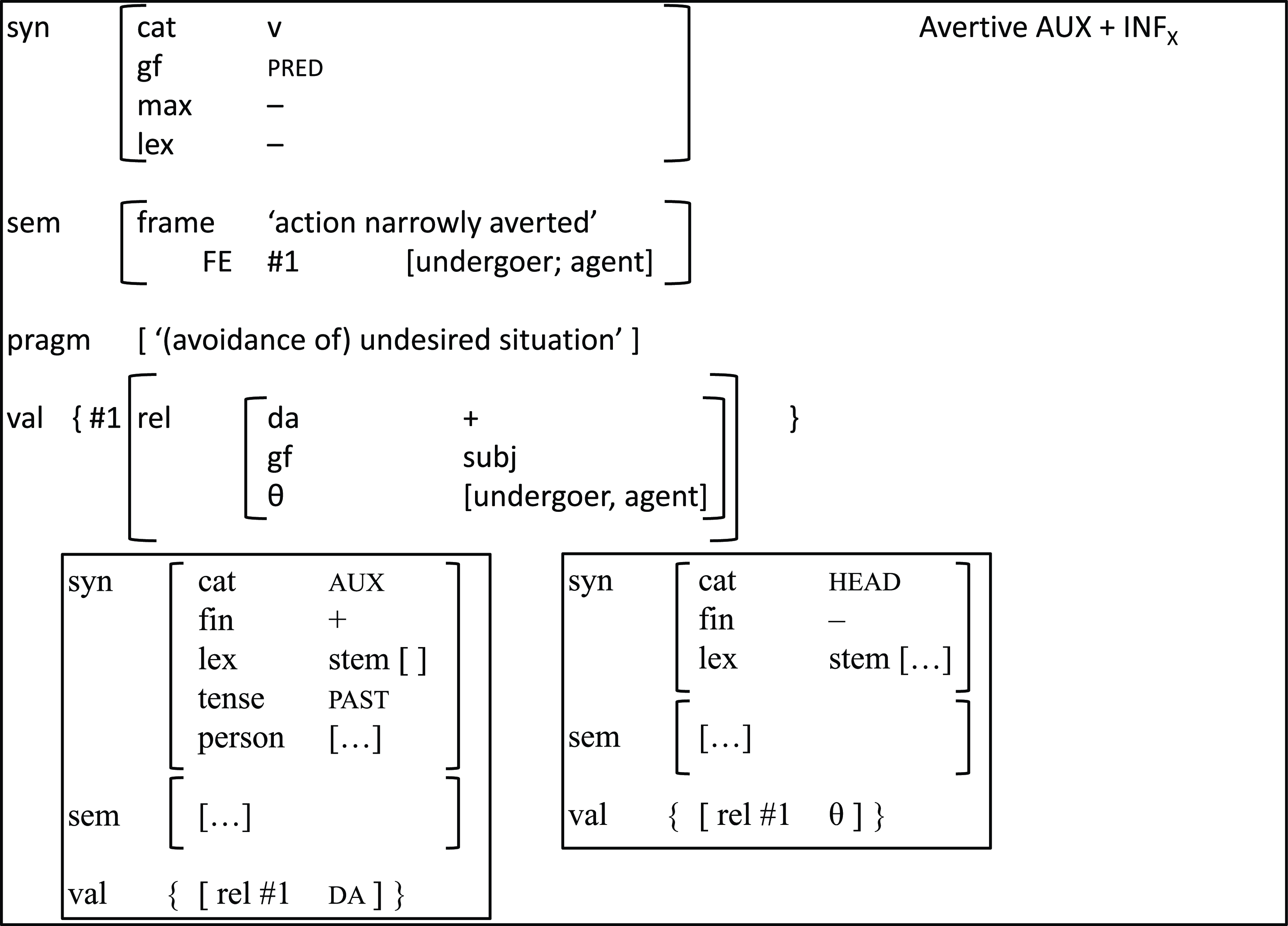

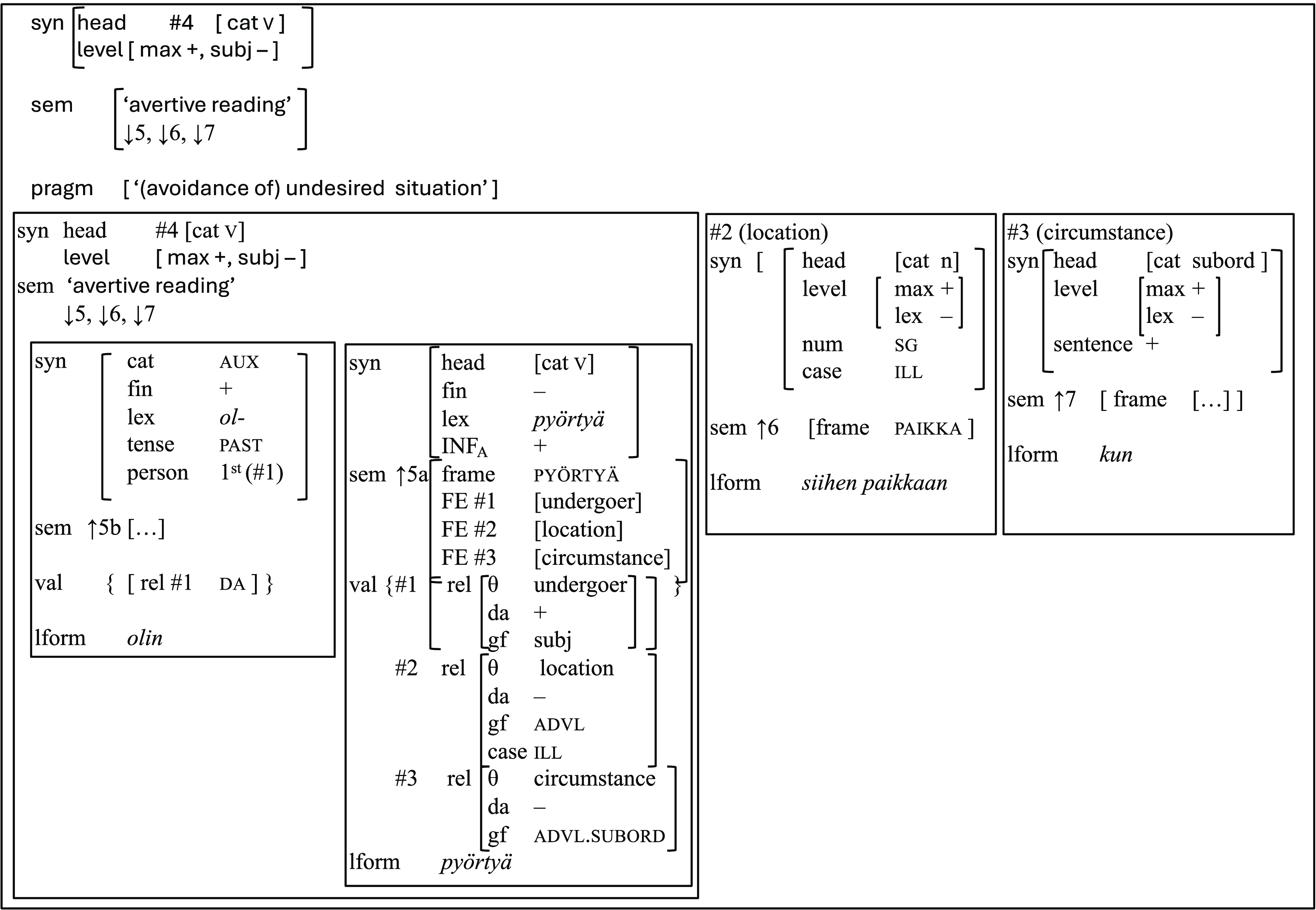

In order to complement the simplified and schematic illustration of the proximative/ avertive subpart of the Finnish constructicon in Figure 1, in Figures 2 and 3 we provide classical CxG box notations following Fried & Östman (Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004) at two levels of specificity. Figure 2, first, is an attempt to characterise the schematic avertive construction in Finnish, i.e. an abstraction over the three constructions, olla + mAisillA, olla + INFA and meinasi + INFA, as seen at the top of Figure 1. Figure 3, in turn, is a description of a specific, substantial contextual usage instance of oli + INFA.

Figure 2. Box notation of the schematic avertive construction.

Figure 3. Box notation of a specific usage instance of the oli + INFA construction: olin pyörtyä siihen paikkaan kun… ‘I was about to pass out on the spot when…’.

What exactly does this schematic avertive construction involve? Following Fried & Östman (Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004:Ch.6), at the top of the box notation, we suggest that the construction is syntactically (syn = syntactic domain) categorised as a verb functioning (gf = grammatical function) as the predicate of the sentence in which it is used. It is also a phrasal predicate (lex –) which needs to be expanded (max –) (see Fried & Östman Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004:30–31). In the semantic domain (sem), the construction’s meaning is characterised as ‘action narrowly averted’ following Kuteva (Reference Kuteva1998), and we argue that it involves one obligatory argument, or frame element (FE), bearing the #1 and corresponding to the semantic role of undergoer (rarely, an agent). Pragmatically (pragm), the construction typically refers to (the avoidance of) undesired situations (reflecting the negative semantic prosody of its collexemes). Finally, in the valence of the construction the syntactic realisation of the prime frame element (FE #1) is stipulated: it is a distinguished argument (da +), it bears the grammatical function (gf) of subject, and its thematic role is that of an undergoer or, exceptionally, an agent.Footnote 28

The lower part of the notation involves two boxes, describing the syntactic, semantic and valence information of the two elements of the complex predicate, i.e. the auxiliary and the infinitive. The auxiliary is characterised as precisely that (aux) and also as a finite verb form (fin +); it is a lexically unspecified stem (lex stem []) in the past tense with an unspecified person ending. Semantically the auxiliary is unspecified for meaning. Its valence, finally, specifies that, from the perspective of the auxiliary, the primary frame element (FE #1) is a distinguished argument (da), i.e. one that needs to be realised here. In the second box, referring to the infinitive, the valence of the construction stipulates that the relationship (rel) between the primary frame element (FE #1) and the verb corresponds to the thematic role stipulated in the construction level valence above, i.e. undergoer (or agent). The semantics of the infinitive is unspecified at this level of schematicity (lacking an explicit verb stem), and the syntactic level simply specifies that the infinitive is the head, is non-finite (fin –) and lexically unspecified.

Whereas Figure 2 illustrates the schematic avertive auxiliary construction, in Figure 3 we offer a detailed characterisation based on a specific usage instance of the oli + INFA construction, namely example (25), repeated here as (55):

In (55), the averted action is to faint. Apart from the first-person subject, the verb is combined with two additional arguments: first, an adverbial indicating the location (where the fainting takes place, i.e. ‘on the spot’) and, second, a subordinate clause indicating the circumstance which, in this case, is the cause of the (non-realised) fainting. From the perspective of this specific usage instance of the oli + INFA construction, both these elements are important for the averted event: the locative element adds drama and emphasis to pyörtyä, whereas the circumstantial when-clause amounts to the cause of the event. In fact, pyörtyä siihen paikkaan can be considered an idiom, and used as such, the locative element is a fixed part of the expression. The box notation in Figure 3 thus includes these two elements as part of the frame of the construction apart from the ‘obligatory’ undergoing subject. Compared to the box notation in Figure 2, there are several layers of additional complexity when characterising a construct, so detailed comments on Figure 3 are in order.

Starting with the syntactic dimension at the top, the first thing to notice is that the construct, as a whole, is categorised as a verb (cat V), which is maximally realised, i.e. it cannot be expanded further (Fried & Östman Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and Östman2004:30). Finnish being a pro-drop language, the subject is not (necessarily) realised as a syntactically distinct element, hence the notation (subj –). Semantically, the construct is only specified as having an avertive meaning, and the numbers (5, 6, and 7) with downward pointing arrows refer to the three main elements of the expression in (55): 5 being the complex predicate (olin pyörtyä), 6 the locative adverbial siihen paikkaan, and 7 the circumstantial kun-clause. Pragmatically we find the same information as in Figure 2, that is, the construct is associated with (the avoidance of) an undesired situation.

Moving down to the three constituents, we can start by the verbal construction, olin pyörtyä ‘I was about to faint’, which is formalised in the largest, leftmost one of the three enclosed boxes. The predicate is, quite naturally, categorised as a verb (cat v); it is marked with #4 to reflect the fact that it is the formal realisation of the head of the sentence (numbers 1–3 are reserved for the frame elements (FE #1, #2, and #3)). As a complex verb form it is, again, maximally realised (hence max +), but its subject is not syntactically explicit but only marked morphologically on the verb (hence subj –). Reference to the three main semantically defined elements of the predicate (↓5, ↓6, ↓7) is repeated on the semantic level (sem) along with the specification of the whole construct bearing an ‘avertive reading’.

In the leftmost of the four small boxes in the lower part of Figure 3 is the specification of the auxiliar form olin ‘I was’. This form is characterised, syntactically, as auxiliary (cat aux) and finite (fin +); it is lexically specified as the stem ol- (to which tense (tense past) and person affixes (person 1st) are later added). Note two things here: first, although the subject is not explicitly realised (hence there is no box marked with #1), it is present here in the form of the person ending on the auxiliary. Second, the auxiliary form is marked, on the semantic level, with ↑5b, indicating that it is part of the predicate, which makes up constituent 5 in the general description (in the upper part of Figure 3). In the valence description of olin, there is also a reference to the subject (constituent #1 of the main verb pyörtyä ‘to faint’) which is a distinguished argument (da) albeit it is syntactically not realised.

The most important information of Figure 3 is found in the characterisation of the main verb pyörtyä (second box from the left on the lower level). Syntactically, pyörtyä is, of course, a verb and it is the head of the sentence (head [cat V]), it is non-finite, lexically specific (lex pyörtyä) and appears in the INFA form. Semantically, this is where most information is located: the frame is made up by the meaning of the verb, i.e. ‘to faint’, and this verb is construed around three elements: a subject (FE #1), a location (FE #2), and a circumstance (FE #3). The characteristics of the three frame elements (FEs) are specified below: FE #1 refers to the subject (gf subj), which is deemed a distinguished argument (da +) and its semantic role is that of an undergoer. FE #2, on the other hand, is the location (θ location), which is not a distinguished argument (hence da –), it is realised as an adverbial (gf advl) bearing illative case. Finally, FE #3 corresponds to the circumstantial subordinate clause (θ circumstance; gf advl.subord), which is not a distinguished argument (da –).

The two rightmost boxes of the lower part of Figure 3 refer to frame elements #2 and #3, i.e. the locative and circumstance adverbials. #2, siihen paikkaan ‘on the spot’ is syntactically specified as a noun phrase (cat n, lex –) which is, in this case, maximally realised (max +), singular (num sg) and in illative case (case ill). Semantically, this NP is made up of the predicate paikka ‘place, spot’ and corresponds to argument 6 in the global construction, hence the mark ↑6, meeting the ↓6 of the higher level boxes.

The subordinate clause introduced by kun ‘when’, finally, makes up frame element #3, and is specified as a subordinate clause (cat subord), it is complex (lex –), maximally realised (max +) and a sentence (sentence +). Semantically, we have decided to leave the characterisation without further specification due to space limitations (in Figure 3 we only include kun, but actually the whole subordinate sentence, with all its elements, would need to be specified in a similar fashion to the earlier parts of Figure 3, which is neither pertinent nor relevant since our aim is to describe the avertive construction). Thus, Figure 3 simply indicates that the frame would need further elaboration in a full account.

We also refrain from elaborating specific constructs, i.e. attested usage instances, of the remaining two constructions, oli + mAisillA and meinasi + INFA due to space limitations and probable overlap, but we hope that the information included in the box notations shown in Figures 2 and 3 illustrate both the relationships among the salient elements of a specific example of one of the constructions (Figure 3) and between the schematic avertive construction and more specific constructions (Figure 2).

6. Conclusions

In this paper we set out to explore what a collostructional analysis of three verbal constructions in Finnish can tell us about the expression of avertivity in Finnish, both from a language-internal and a cross-linguistic perspective. Where on the avertivity continuum are the Finnish constructions situated? And how do they relate to (a) other similar (AUX + INF) constructions in Finnish and (b) other means of expressing the meaning ‘almost V’ (Kuteva Reference Kuteva1998)?