The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and the resulting widespread political and economic instability provided fertile soil for criticism of and alternatives to the international liberal order. Among them, financial nationalism with an illiberal orientation emerged as a particularly appealing approach for many governments and populaces. Beginning in the postcommunist region, parties like Fidesz in Hungary and Law and Justice in Poland came to power with an illiberal agenda that was nationalist in content and an economic development approach that was financial in focus. Over time, those principles gathered political support in other countries and regions as well. Although the details have varied among states, a discernable, internally coherent illiberal financial nationalist worldview and policy program has emerged internationally and continues to evolve.

The spread of illiberal financial nationalism represents a potent challenge to economic liberalism and political democracy. At the same time, this contemporary manifestation of financial nationalism is fundamentally shaped by its emergence from within the international liberal order. Financial globalization both constrains the policy options of financial nationalists and provides opportunities for them to draw on transnational financial resources and institutions to advance nationalist causes. Contemporary financial nationalism is thus not characterized by the simple rejection of financial openness but rather by the strategic deployment of that openness to the benefit of the nation.

In this article, we offer a conceptual description and analysis of contemporary financial nationalism. We begin by delineating the approach’s fundamental characteristics, what distinguishes it from other versions of economic nationalism or developmentalism, and how the evolution of the global financial system made it both appealing and feasible for nationalist governments. In doing so, we suggest why this version of financial nationalism first took hold in middle-tier economies on the periphery of Europe after the global financial crisis. We next outline a four-part typology of policy approaches that leaders with a financial nationalist agenda might adopt—internal insulating, internal revisionist, external insulating, and external revisionist—which we call the four faces of illiberal financial nationalism. We then turn to policy choice and implementation, identifying the resources and capabilities needed to pursue such policies and explaining how the four policy approaches can build on one another. Throughout, we provide illustrative examples from such influential cases as Hungary, Poland, and Russia. We conclude by discussing the domestic and international implications of pursuing illiberal financial nationalism as well as how that pursuit might evolve over time.

The Worldview: Nationalist, Finance-Centric, and Illiberal

Recent years have seen a resurgence in economic nationalist sentiment around the world, prompting extensive scholarly efforts to document, analyze, and classify it. Much research has focused on the paradigmatic cases of Hungary and Poland and to a lesser extent other European postcommunist states (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Mérő and Piroska Reference Méró and Piroska2016; Bohle and Greskovits Reference Bohle and Greskovits2019; Toplišek Reference Toplišek2020; Ban and Bohle Reference Ban and Bohle2021; Piroska and Mérő Reference Piroska, Mérő, Mertens, Thiemann and Volberding2021; Varga Reference Varga2021; Naczyk Reference Naczyk2022; Oellerich Reference Oellerich2022; Piroska Reference Piroska and Pickel2022; Sebők and Simons Reference Sebők and Simons2022; Ban, Scheiring, and Vasile Reference Ban, Scheiring and Vasile2023). The phenomenon has not been limited to this region, however, with scholars exploring the rise in economic nationalism in countries and regions as diverse as China (Helleiner and Wang Reference Helleiner and Wang2019), Russia (Johnson and Köstem Reference Johnson and Köstem2016), Turkey (Köstem Reference Köstem2018b; Madra and Yılmaz Reference Madra and Yılmaz2019), Bolivia (Naqvi Reference Naqvi2021), India (Jain and Gabor Reference Jain and Gabor2020; Chacko Reference Chacko2021), Great Britain (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2017), Western Europe (Epstein and Rhodes Reference Epstein, Rhodes, Caporaso and Rhodes2016; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2019; Donnelly and Asimakopoulos Reference Donnelly and Asimakopoulos2020; Donnelly and Pometto Reference Donnelly and Pometto2024), and North America (Helleiner Reference Helleiner2019; Baltz Reference Baltz2021). As many have rightly noted, these economic nationalisms are diverse in political orientation and economic focus, so much so that using “economic nationalism” as a blanket term to describe them can obscure as much as it reveals. This has led scholars to take deeper dives into contemporary economic nationalisms, exploring their nature by region and by subtype.

It is in that spirit that we explore the rise of a particular subtype of economic nationalism—illiberal financial nationalism—across the postcrisis world. Although contemporary economic nationalisms vary in multiple respects, one commonality is a much greater emphasis on the financial sector than has been typical in other eras. As De Bolle and Zettelmeyer (Reference De Bolle and Zettelmeyer2019) find in their analysis of 55 party platforms across the G-20 states, for example, both advanced and emerging-market economies experienced shifts toward what they characterize as “macroeconomic populism” as well as skepticism of multilateral organizations. As we explore further below, this makes sense given both the unprecedented financial globalization of recent decades and the finance-centric nature of the 2008 crisis and its aftershocks.

Contemporary financial nationalism represents a view of the world that is (1) nationalist in its motivation for political action, (2) financial in its policy focus, and (3) illiberal in its conception of political economy. In this section, we elaborate on each of those characteristics, distinguishing them from similar concepts and exploring how they combine to create a policy space that is both consistent enough for theory and flexible enough for practice. We also show why and how these particular characteristics have flourished in recent years.

Nationalist in Motivation

Financial nationalism is first and foremost a nationalist project, which creates a different palette of likely policies and a different pattern of politics than other approaches do (Helleiner Reference Helleiner2002; Nakano Reference Nakano2004; Crane Reference Crane1998; Shulman Reference Shulman2000). Nationalism is a political ideology that places the collective interest of the home nation above that of the individual, other groups, and other nations. Nationalists draw contrasts between national insiders as opposed to “foreign” outsiders and identify both groups through collective rather than individual characteristics. Nationalists also typically identify a particular state or territory as the nation’s homeland and believe that members of the nation should exercise political sovereignty over that geographic region. The perceived geographic boundaries of the nation may encompass territories larger or smaller than existing state boundaries.

Furthermore, nationalists who identify with a particular state rarely consider all residents of that state to be members of the nation as well. Nationalists will typically identify specific individuals and groups as outsiders—that is, not legitimate members of the nation—because of transnational, ideological, ethnic, religious, or linguistic identities, relationships, or behaviors that nationalist elites perceive as antithetical to the nation. Similarly, external groups (such as coethnic diasporas) may be defined as national insiders and thus as potential beneficiaries of nationalist policies despite their physical location. Although nationalists may also be populists who express distrust of elites and expertise and claim to elevate “the people,” the two should not be conflated (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Nationalism and populism coexist only to the extent that a particular nationalist ideology draws an insider/outsider distinction based on elite status.

The nationalist conception of the international political economy, therefore, differs from both the liberal and the developmentalist ones. Whereas liberalism views individuals and firms as the primary actors in the global economy, conceives of the economic arena as one of exchanges among those actors, and argues that voluntary exchange can make all participants better off, nationalists see nations as the primary actors and the rightful beneficiaries of government policies. Likewise, where developmentalism argues that each government needs to promote its own economy or leading sectors, nationalism argues that the nation rather than the state or any segment of it is the most relevant actor in the system and that economic policy should be in its service.

A nationalist approach to policy thus focuses on achieving relative gains for national insiders vis-à-vis outsiders and casts its criticism of alternative economic policies in the same language. Economic nationalists seek to align the economic position of the nation and its insiders with what they perceive to be the nation’s identity and rightful status. Economic nationalists might, for example, seek to reorient a country’s international economic relationships more toward regions, countries, and groups that they believe share broader identities, values, histories, and/or cultural attributes with their nation and away from those that do not (Abdelal Reference Abdelal2001; Köstem Reference Köstem2018a). Second, and related, economic nationalists believe in using economic institutions and policies to build national unity and to serve the nationalist cause (Nakano Reference Nakano2004). For example, economic nationalists might support the expropriation of foreign-owned companies in favor of national insiders, who in turn would be expected to use these companies not just to make money for themselves but to work collaboratively with other national insiders to advance the collective cause.

Clift and Woll (Reference Clift and Woll2012) have more broadly described the post-GFC reemergence of interventionism in economic policy making as economic patriotism, a term embraced by politicians as diverse as Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán and US Senator and former presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (see also Clift Reference Clift and Pickel2022). For Clift and Woll, economic patriotism “is agnostic about the precise nature of the unit claimed as patrie: it can also refer to supranational or sub-national economic citizenship” (307). It is therefore a more encompassing concept than economic nationalism. Both concepts, however, have at their core the ideological commitment to distinguish in-group from out-group members based on collective rather than individual characteristics and to pursue economic policies to privilege the in-group.

Orbán began using the term “economic patriotism” to describe his government’s policies as early as 2012, and he has called the 2008 global financial crisis a system-breaking event comparable in scale to World War I, World War II, and the collapse of the Soviet bloc (Orban Reference Orbán2014a). He boasted in his February 2014 State of the Nation address that “we have had enough of the politics that is forever concerned with how we might satisfy the West, the bankers, big capital and the foreign press…. Over the past four years we have overcome that … subservient mentality…. Hungary will not succumb again!” (Orban Reference Orbán2014b). More ominously, as he noted in 2016 in a special forum on economic patriotism, “People say that money doesn’t smell, but the owner of the money does” (Strzelecki Reference Strzelecki2016).

Such a nationalist (or patriotic) conception of political economy can inspire different measures of policy success and failure than other approaches, which may help sustain a nationalist leadership in times of trouble. Whereas developmentalist programs evaluate themselves based on economic growth or the success of particular industrial sectors, economic nationalism’s fundamental goal is to promote “the nation.” All economic programs eventually face downturns, which make them susceptible to political challenge. Economic nationalists reject such challenges on nationalist grounds; not only does the national purpose justify economic sacrifice, but downturns can be blamed on disloyal actors or on the calumny of other nations or international institutions.

Financial in Emphasis

Financial nationalism, as a subset of economic nationalism, intentionally leverages financial systems, institutions, and rules to pursue nationalist ends. Financial nationalists identify the use and control of central and commercial banks, state-owned and development banks, national currencies, monetary policy and exchange rates, portfolio and FDI flows, taxation, sovereign debt and lending, international reserves, financial regulation, and international financial institutions as tools through which to advance their goals. The approach thus differs from traditional models of developmentalism or state capitalism, as it does not inherently demand trade protectionism or require the state to own or fund large production enterprises.

Although financial nationalism has clear intellectual precedents in early nationalist debates over creating territorial currencies, building national public debt, dealing with foreign banks, and the strategic use of foreign borrowing (Helleiner and Wang Reference Helleiner and Wang2019), it has become increasingly salient as a response to financialization and financial globalization. Financialization, as explored in Krippner’s (Reference Krippner2005, Reference Krippner2012) now classic work, began in earnest in the 1980s in the United States and is the domestic process by which financial profit-making achieves increasing dominance over the “real” economy that produces and trades goods and services. Financial globalization, meanwhile, is the parallel international process by which countries have opened their financial systems to each other through mechanisms such as capital account liberalization, often through the encouragement of international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund. This went hand in hand with the US dollar’s increasing dominance in international accounting and transactions as well as the creation or further empowerment of an expansive range of international institutions, standards, and systems for facilitating cross-border financial flows. Financialization and financial globalization fed on and reinforced each other, profoundly transforming domestic and international economic relationships (Mader, Mertens, and Van Der Zwan Reference Mader, Mertens, Van Der Zwan, Mader, Mertens and Van Der Zwan2020).

This reciprocal process underwent a qualitative change in the 2000s as market-based banking (for example, shadow banking and direct financing through capital markets) took off and increasingly supplanted traditional bank-based lending, challenging domestic regulators and making the international financial system more vulnerable to crises (Hardie et al. Reference Hardie, Howarth, Maxfield and Verdun2013; Braun and Deeg Reference Braun and Deeg2020). In their influential work on the infrastructural power of finance, Braun and Gabor (Reference Braun, Gabor, Mader, Mertens and van der Zwan2020) argue that the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank worked with private actors to facilitate the rise of market-based banking, not only deeply entangling the state with international financial markets but also engendering central bank dependence on shadow banking for implementing and transmitting monetary policy. The active worldwide diffusion of the model of the independent central bank focused on price stability and inflation targeting reinforced such dynamics, as central bankers became less responsive to their own governments and more embedded in international financial networks (Johnson Reference Johnson2016). The global payments and clearing infrastructure that these international financial flows depend on is primarily provided by a handful of private companies (Brandl and Dieterich Reference Brandl and Dieterich2023). Financialization and financial globalization not only transformed economic relationships and deepened cross-border connections but also transferred power away from state institutions and actors while reinforcing the structural power of finance. As international financial flows became more intense and less connected to the real economy, they also became less likely to enhance economic growth and increased the likelihood of financial crises (Dafe et al. Reference Dafe, Hager, Naqvi and Wansleben2022).

For these reasons, although financialization and financial globalization have profoundly affected governance everywhere, these effects have been different and more challenging for developing and emerging economies (DEEs). Alami et al. (Reference Alami, Alves, Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, Koddenbrock, Kvangraven and Powell2023) identify DEEs as victims of international financial subordination, meaning “a spatial relation of domination, inferiority, and subjugation between different spaces across the world market, expressed in and through money and finance, which penalizes actors in DEEs disproportionately” (1379). International financial subordination, sometimes also referred to as dependent financialization, renders DEEs increasingly reliant on external capital markets and foreign financial institutions to finance domestic investment needs for everything from large companies to household mortgages. It complicates the ability of DEEs to conduct independent macroeconomic policies and to maintain financial stability. This financial dependence, openness, and integration easily transmits financial shocks to DEEs from the core and puts the burden of adjustment on DEEs (Bortz and Kaltenbrunner Reference Bortz and Kaltenbrunner2018), whereas global wealth chains transfer financial resources from DEEs to the core (Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, and Powell Reference Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner and Powell2022).

The 2008 global financial crisis and its aftermath sparked nationalist challenges to this financial dominance and vulnerability in advanced industrial economies and DEEs alike, as the fact that a massive crisis could begin within the USA’s nearly unregulated shadow-banking realm and spread worldwide within a matter of months, destroying lives and wealth, undermined the legitimacy of the international financial system and put “apolitical” finance back on the political agenda. At the same time, the GFC provided opportunities and political cover for governments in DEEs to reorient their financial relationships and practices, as financial institutions from the wealthier economies pulled resources out of DEEs and leading central banks embraced “unorthodox” quantitative easing and financial stability policies. Although Gabor (Reference Gabor2021) and others have shown the persistence and evolution of financial globalization after the GFC, attempts to challenge it politically have evolved as well. Central and East European states have, for example, actively used macroprudential policy to manage the uneven effects of financial globalization and European integration (Piroska, Gorelkina, and Johnson Reference Piroska, Gorelkina and Johnson2021). As Dafe and Rethel (Reference Dafe and Rethel2022) observe, the contemporary centrality of finance in domestic and international political economies has made standard industry-focused development strategies relatively ineffective, forcing developmentalists to turn their focus to the financial sector.Footnote 1 We argue that the same is true for economic nationalists, who have increasingly seen finance as the key economic sector that should reflect the nation’s identity and advance the nationalist cause.

Illiberal in Conception

Although nationalist ideas have historically inspired economic policies across the ideological spectrum (Mikecz Reference Mikecz2019; Abdelal Reference Abdelal2001; Helleiner Reference Helleiner2002; Pickel Reference Pickel2003) and economic nationalism itself has diverse roots and forms (Helleiner Reference Helleiner2021), the dominant form of financial nationalism today is self-consciously illiberal. That is, contemporary financial nationalism is an expression not only of support for “the nation” but also of opposition to the international liberal order. As such, it received a strong political boost from the global financial crisis and first emerged as a leading political contender in Central and Eastern Europe, where externally driven financialization had progressed the farthest (Karwowski Reference Karwowski2022) and the idea that the allegedly unbiased rules of market economies were actually tools of Western dominance had historical resonance. Financial nationalism’s latest illiberal iteration arose as a reaction to the perceived failure of the post-1945 Western-led “coalition for economic openness” (Fioretos Reference Fioretos2019) and its financial institutions, norms, and practices that spurred unprecedented levels of financial globalization. The global financial crisis and its aftermath provided fertile soil for criticism of the dominant international liberal order and made challenging or even overturning it newly “thinkable” and attractive.

Contemporary financial nationalists view with deep skepticism the claims of transnational expert communities that open financial policies benefit all players and reward innovation and efficiency. Indeed, these politicians express doubt that economic liberalism truly motivates any governments or technocrats in practice. They argue that these actors are cynical, knowing that their allegedly universalist policies benefit their own countries at the expense of others. As a Polish politician put it, “Rich countries have already reached the peak of their development, and now they are defending deregulation, a liberal approach and globalization because it is good for them” (Foy Reference Foy2016). Advocates of today’s illiberal version of financial nationalism see it as a way to circumvent the unjust constraints of the international liberal order. Illiberal financial nationalism is an ideology of challenge and of change, which is why it is often imbued with populism and is especially attractive to DEEs in positions of international financial subordination.

When speaking to external audiences, illiberal financial nationalists may argue that their policies are fundamentally no different from those of so-called liberal states that regularly intervene in markets. Virtually every government engages in at least some financially “heterodox” policies. Few currencies float entirely freely, and most states pursue domestic monetary sovereignty. Furthermore, states often try to insulate their economies, firms, and citizens from the periodic shocks inherent in global capitalism. Indeed, the major reactions to each financial crisis since the Great Depression can be seen as attempts to protect market participants and the liberal system itself from catastrophic meltdowns: bank recapitalization, deposit insurance, laws on financial prudence, and the adoption or abandonment of currency pegs are just a few examples. The introduction of these policies may even include some us-versus-them language, and leaders may speak about their domestic economies as if they were competing with similar units around the world.

It is important to recognize, however, that such “ordinary illiberalism” is not framed in terms of nationality or national purpose. Illiberal financial nationalism, in contrast, is justified as protecting “the nation,” not just the domestic economy, and goes well beyond pursuing monetary sovereignty or providing insurance for those caught in a financial crash (Varga Reference Varga2021). Advocates of illiberal financial nationalism replace the Marxist argument that the international liberal order serves capitalists with the nationalist argument that the international liberal order serves unworthy nations, often the United States, those in “the West,” or particular ethnic or religious groups (see Lockwood Reference Lockwood2021).

Policy Clusters: The Four Faces of Contemporary Financial Nationalism

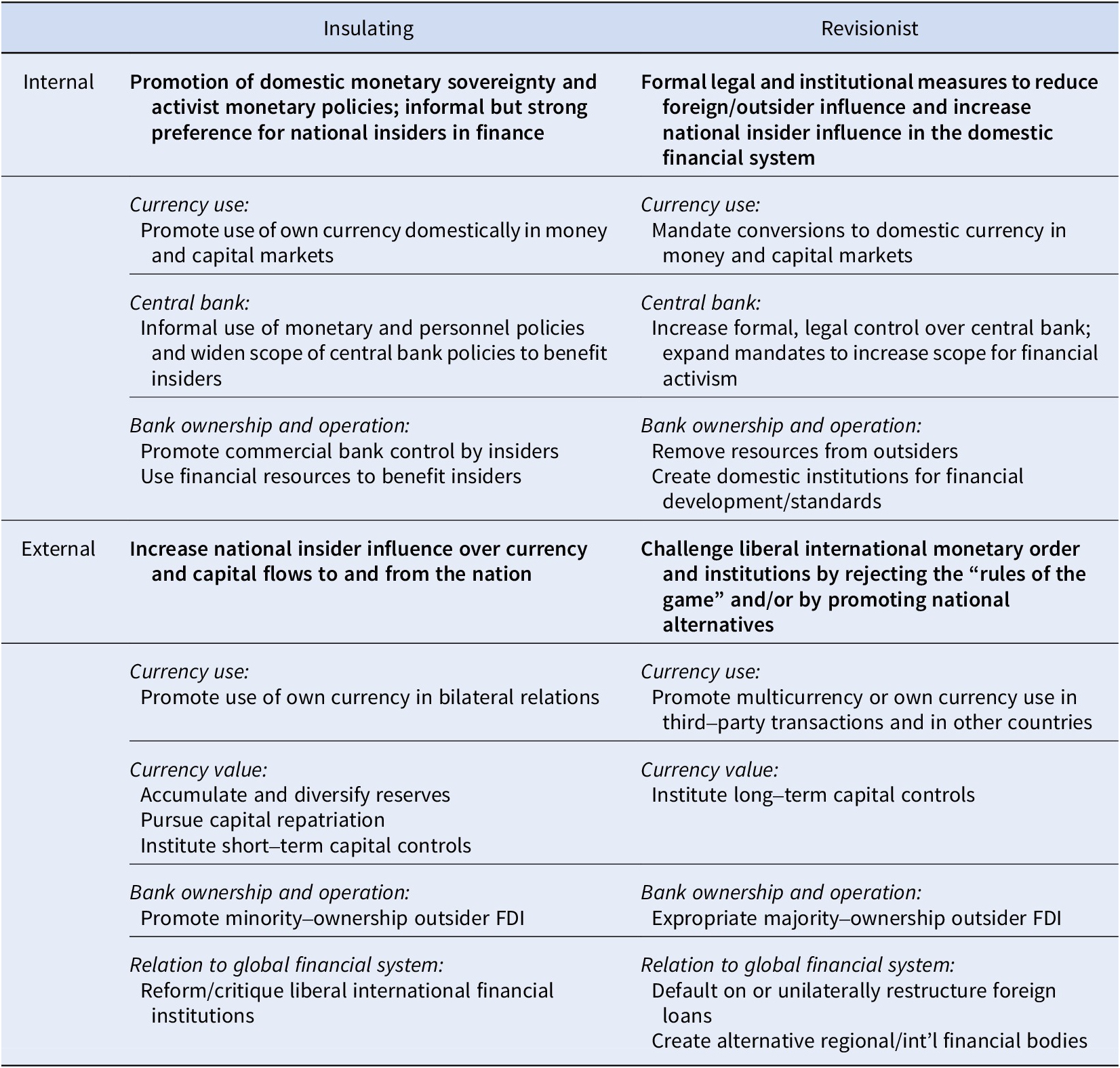

The combination of nationalist purpose, financial methods, and illiberal worldview distinguishes illiberal financial nationalism from other approaches to economic policy. If a political movement adopts an illiberal financial nationalist outlook, the sorts of financial policies it might advocate and pursue when in power can be usefully clustered along two dimensions (see Table 1). The first dimension runs from insulating to revisionist. Insulating policies control or limit the nation’s exposure to national outsiders (for example, through financial protectionism). Revisionist policies, on the other hand, directly challenge national outsiders and their place in financial institutions and orders (for example, by transforming or replacing institutions). Insulating policies typically work through established and more informal channels, whereas revisionist policies entail formal and more extensive legal and institutional change. The second dimension runs from internal to external. Internal policies focus on the domestic financial system (for example, the central bank), whereas external policies focus on the nation’s role in international or regional financial systems (for example, currency internationalization) and on the influence of international financial forces on the nation (for example, through exchange rates and international capital markets). Combining the two dimensions yields the four faces of contemporary illiberal financial nationalism: internal insulating, internal revisionist, external insulating, and external revisionist.Footnote 2

Table 1. The Four Faces of Illiberal Financial Nationalism

It is important to recognize that these “faces” represent approaches to financial nationalism and are therefore classifications of policy types, not states. As we will see, financial nationalists can advocate for and pursue multiple approaches, if they have the resources and capability. Table 2 presents policy clusters that are compatible with each ideal-type approach.

Table 2. Illiberal Financial Nationalism in Practice

Internal insulating financial nationalism involves promoting the use of the state’s currency in domestic pricing, savings, and private and commercial loans. To the extent possible, a financial nationalist government will support its spending through public debt denominated in the domestic currency (this has been a central preoccupation of the Orbán government and Hungary’s Government Debt Management Agency, AKK). Conducting business in foreign currencies will typically be discouraged, as will moves toward joining a supranational currency union or adopting a currency board. Financial nationalist leaders in both Hungary and Poland firmly rejected the idea of joining the euro area, even though both countries are obliged to do so by their accession agreements. Advocates also promote the physical currency and its iconography as a national symbol and emphasize its use in daily transactions and savings as a patriotic act (Helleiner Reference Helleiner1998)—for example, as Russian leaders did during their pre-GFC de-dollarization campaign (Johnson Reference Johnson2008).

Internal insulating policies also seek to direct financial resources to national insiders for avowedly nationalist purposes, employing insider-controlled commercial banks, state-owned banks, or the central bank to do so. Illiberal financial nationalist governments thus have a strong preference for establishing insider majority-owned or majority-directed institutions throughout the financial sector, including domestic development banks. Internal insulating policies include supporting institutions owned by national insiders through preferential policies regarding regulation, taxation, and access to government accounts. Illiberal financial nationalists prefer greater control over the central bank because active government use of monetary power, by definition, precludes meaningful central bank independence. In addition, technocratic central bankers have typically been socialized into a transnational central banking community with a universalist outlook and suspicion of nationalist, particularistic goals (Johnson Reference Johnson2016).

Internal insulating financial nationalist policies would include installing loyalists at the central bank or assigning it financially activist tasks that fall outside the normal scope of duties for an independent central bank. Once appointed, financial nationalists within the central bank may expand the scope of its informal “operating mission” to achieve greater leverage over the domestic financial system and benefit national insiders (Sebők, Makszin, and Simons Reference Sebők, Makszin and Simons2022). In a particularly egregious example, Hungarian national bank governor György Matolcsy used over $1 billion of the bank’s profits during 2014–2015 to found six new Hungarian institutes that “do not propagate failed neoliberal doctrines” (Portfolio.hu 2014).Footnote 3 A scandal erupted in 2016 when it was revealed that in addition to their educational work (which included publishing a six-volume amateur history of Hungary intended to “strengthen the patriotic sentiment against globalist view”), the foundations had purchased government debt, acquired Hungarian artwork and real estate, supported Fidesz-friendly media outlets, and funneled significant sums to a private Hungarian bank owned by a relative of Matolcsy (The Economist 2016).

Internal revisionist policies seek not only to influence the domestic financial system for the benefit of national insiders but also to restructure it formally and institutionally in important ways. Formal control over the central bank can be expected to increase when a government decides to move in this direction, including legislative changes to reduce central bank independence (Sebők Reference Sebők, Bakir and Darryl2018; Piroska, Gorelkina, and Johnson Reference Piroska, Gorelkina and Johnson2021). New rules may require conversion of businesses’ international profits to domestic currency to support its value and encourage investment at home. Banks may be required to convert foreign-currency-denominated loans into the local currency at unfavorable rates, as occurred in both Hungary and Poland. Internal financial revisionists may also take on foreign ownership in the financial sector, either driving foreign owners out completely or reducing their holdings to minority shares. For example, when Fidesz came to power, over 85% of the Hungarian banking sector was foreign owned. Orbán said repeatedly that so much foreign ownership in the banking sector was “unhealthy” and that at least 50% (later 60%) should be held by Hungarians. The government had achieved the 50% target by 2014 through foreign exit and domestic acquisition of major institutions (Buckley Reference Buckley2014). In Poland, even before the electoral victory of Law and Justice in 2015, its chairperson Jarosław Kaczynski in 2012 declared, “It must be made clear … that our goal is a re-Polonisation of Polish banks” (Goclowski Reference Goclowski2016). Likewise, they may seek to create domestic investment funds and ratings bureaus that they can use to promote the interests of the nation as they understand it.

The policies that are characteristic of external insulating financial nationalism include promoting the use of the national currency in bilateral trade contracts, swap lines, loans, and bonds. Politicians advocating these policies prefer domestic over international sources of finance when available and chafe at owing money to outsiders. They will accumulate extensive and diversified reserves to insulate the national currency against exchange rate risk and external shocks, which may also involve creating sovereign wealth funds. At the same time, financial nationalist politicians with an eye toward external insulation will welcome external investment as long as they believe such flows can be controlled and harnessed in support of the nation (cf. Logvinenko Reference Logvinenko2021 on Russia). They may, for example, actively encourage foreign investment to help build the national economy but in limited and targeted ways, denominated in domestic currency, and in minority rather than majority shareholder roles.

Would-be external insulators also seek to reform established liberal international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the International Monetary Fund or the European Central Bank. Financial nationalist leaders deride the neutral, universalist rhetoric of IFIs as a smokescreen for policies that intentionally weaken those states and enterprises that could otherwise displace current leaders in the global economy. In 2012, Fidesz rejected IMF assistance entirely, throwing the IMF resident representative out of the country in 2013 and eventually repaying Hungary’s debt to the IMF in order to reduce dependence (Balasz Reference Balasz2012; Central Banking 2013). Financial nationalist politicians can be wary of taking advice and funds from these institutions, believing that doing so undermines national sovereignty, while at the same time they may agitate for greater representation in these institutions to give their nations their rightful voice.

As discussed more extensively below, external revisionist financial nationalists seek to transform the international liberal order and the state’s relationship with it for the benefit and glory of the nation. They may, for example, promote the use of their own currency in other countries and/or institute long-term capital controls to protect their currency. In the arena of ownership, external revisionists may expropriate assets that are majority owned by outsiders, and if they think they can get away with it, they may be willing to default on foreign-currency loans during tough times. Perhaps most ambitiously, external revisionist governments can attempt to establish new international financial institutions and standards to supplement or even replace the existing ones they distrust.

Illiberal financial nationalists should not be expected to pursue every policy within a category. Indeed, choosing and implementing certain policies could undermine the effectiveness of others—for example, currency internationalization has the potential to negatively affect the flexibility of domestic monetary policy and precludes capital controls (Cohen Reference Cohen2018). It is the conjunction of nationalist rhetoric and justifications—that is, the explicit articulation of a financial nationalist purpose that challenges the international liberal order—with the promotion of one or more of these policy approaches that makes illiberal financial nationalism.

Policy Choice and Implementation: Constraints and Enablers

Intellectually embracing illiberal financial nationalism is one thing, but actually implementing financial nationalist policies is another. Political, economic, and structural factors determine a political movement or leadership’s ability to successfully pursue policies across the four clusters. First, financial nationalists must have political control over the domestic levers that are necessary to execute the policies in question. Second, they need sources of financing. Third, their capacity to implement externally oriented policies in particular depends on their state’s position in the international system. The interplay among these factors affects both choice and implementation.

Domestic Political Power

A foundational requirement for carrying out illiberal financial nationalist policies is gaining political control over the domestic levers necessary to enact and execute those policies. In the policy-making arena, this means dominating the legislature (or its equivalent) as well as marginalizing any liberal opposition. In the executive branch, the most important agencies are the central bank and such ministries as finance and economics, which enable financial nationalists to shape banking and currency policy. In addition, some illiberal financial nationalists must influence the judiciary to stave off challenges to their policies. As Karas (Reference Karas2022) demonstrates, in Hungary this process involved the Orbán government’s creation of a “financial vertical” that consolidated state control over the central bank, credit provision, and domestic financial institutions. Persuasively arguing that having a subordinate position in the international financial system does not mean that domestic actors lack agency in confronting it, he shows that Orbán was able to turn Hungary’s financialized system to his own political and economic ends.

In practice, the pursuit of this political efficacy has led to creeping authoritarianism wherever it has been attempted, even where financial nationalists originally came to power in democratic elections including in Hungary (Piroska Reference Piroska and Pickel2022), Poland (Jasiecki Reference Jasiecki, Bluhm and Varga2018), and Turkey (Apaydin and Çoban Reference Apaydin and Çoban2023). Illiberal financial nationalist policies are based on an exclusionary version of nationalism and frequently entail major changes in privileges and practices within the financial sector. This means that the nationalists are challenging significant vested interests and they regularly seek ways to circumvent those interests. Importantly, opposition to financial nationalist policies is not likely to come from a broad alliance of citizens, who may be indifferent to or supportive of them. Instead, resistance is more likely to come from technocrats, bureaucrats, foreigners, and established financial actors who stand to lose from the changes. In Poland, for example, domestic banks were able to block forced forex loan exchange programs at least temporarily. Generally, however, financial nationalism often benefits important domestic interests and politicians’ nationalist rhetoric can be a powerful political tool for staving off challenges.

Sources of Financing

Like any other government, one that hopes to pursue illiberal financial nationalist policies needs reliable sources of financing. In today’s world, that requires interacting in meaningful ways with the existing global financial system, even as these governments deride, deflect, or try to change that system. Thus, although illiberal financial nationalism positions itself in opposition to the universalist claims of the international liberal order, it is also fundamentally shaped by its emergence from within that order. Just as financialization makes it possible to create a domestic “financial vertical” (Karas Reference Karas2022), financial globalization and its institutions not only constrain the policy options of illiberal financial nationalists but also provide opportunities for them to draw on transnational financial resources and institutions to advance their nationalist cause. Illiberal financial nationalists must strategically deploy international relationships to benefit national insiders and their allies, and in fact successful financial nationalist strategies are often actively enabled by the liberal international institutions.

The most general source of external funding for governments is the international bond market. It may seem counterintuitive that international lenders would tolerate financial nationalist policies and the undemocratic politics they often entail, but in practice those lenders appear to be concerned almost entirely about borrowers’ ability and willingness to make bond payments on time. That is, as a group, bond traders behave as if they have a single-minded commitment to returns relative to risk, without much regard for political openness, nationalist policy goals, or even negative treatment of foreign-owned financial institutions (Mosley Reference Mosley2003; Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Barta and Johnston Reference Barta and Johnston2023). This does place constraints on DEE governments in particular—they must maintain a manageable level of inflation and enough fiscal discipline to ensure timely payments on sovereign debt—but otherwise, practical restrictions are few. Access to the international bond market requires that the government’s fiscal and monetary policies be seen as at least minimally “credible” (Grittersová Reference Grittersová2017). Moreover, in a world with permeable financial borders, monetary instability would invite the informal replacement of domestic currency with foreign, undermining monetary sovereignty. Successful contemporary financial nationalist governments can therefore be expected to pursue baseline orthodox goals, even if by unorthodox means. Financial nationalist governments may reject the logic of austerity and the self-imposed chains of conservative central banking, but successfully achieving monetary sovereignty, privileging national financial institutions, and promoting one’s own financial institutions or currency abroad requires a certain restraint, predictability, and stability in critical monetary and fiscal indicators. Thus, the internal goal of monetary sovereignty in an external environment of financial globalization creates pressure to achieve relatively orthodox outcomes in terms of controlling inflation as well as public debt and deficits.Footnote 4 Indeed, Hungary’s failure to do so after the 2020 COVID shock and subsequent election-related spending made the Orbán government’s economic model vulnerable for the first time since its consolidation over a decade ago.

A more geographically limited source of finance is direct support from an economic bloc. Countries in the European Union, for example, can take advantage of the Structural and Cohesion Funds to bridge budget deficits, even if leading members of the bloc oppose financial nationalist policies (Bozóki and Hegedűs Reference Bozóki and Hegedűs2018). The process for gaining access to such funds, and even the ability to do so, is determined by individual blocs’ rules of governance and their internal distributions of political power, but to date, no state has been effectively excluded from these resources because of its economic policy choices. Hungary and Poland remained net recipients of funding from the EU even as the union finally began to impose sanctions in response to corruption and violations of democratic principles. Governments need only meet the macroeconomic standards of the bloc, reinforcing the pressure to keep inflation, debt, and deficits under control to pursue financial nationalism successfully.

A third source of external finance is trade and selective permission for foreign direct investment. This too seems to depend much more on investors’ perception of risk and return than on the broader policy environment, including questions of civil liberties. Even international efforts to sanction particular countries do not effectively shut off access to external investments if the lure of returns is sufficient. The key for the financial nationalist government is to actively guide the terms and timing of these financial inflows and outflows such that foreign investment cannot lead to outsider control over major domestic financial institutions or corporations, establish major foreign-owned competitors to them, or become so dominant that unexpected outflows would lead to financial crisis. In this way, contemporary financial nationalist governments can leverage international capital to suit their own strategic purposes.

Finally, select countries may have the internal resources to self-finance. This is easiest in countries with large domestic economies and/or significant natural resources, such as Russia or China. As with the other options, a successful financial nationalist government will need to participate in the international financial system sufficiently reliably to exchange payments with international buyers and their banks, but as long as it meets those minimum requirements, it will have significant leeway in structuring its domestic financial sector.

Position in the International System

Even if domestic political power and sources of financing are secured, a government’s ability to pursue or even sensibly contemplate illiberal financial nationalist policies is affected by its position in the international financial system. Murau and van’t Klooster (Reference Murau and van’t Klooster2023) have introduced the concept of “effective monetary sovereignty” to capture what states under conditions of financial globalization are actually able to do. They define effective monetary sovereignty as “the state’s ability to use its tools for monetary governance to achieve its economic policy objectives” (1328), which involves state monetary governance over “not only the issuance of public money forms, but also governance of regulated banks and unregulated money forms, onshore and offshore” (1320). States with more privileged positions in the international hierarchy of money simply have more policy space. For example, the government of a small DEE state cannot realistically consider external revisionist policies, regardless of how consolidated its power is at home. The options open to a regional or global financial powerhouse, in contrast, are more considerable, as they can try to insist that certain trades be conducted in their own currency, that bank transactions take place through their preferred payment systems, and so on. The concerns of financial nationalists in these countries may be thought of in terms of two ideal types. The first, as in Russia, see their nation as disadvantaged by the Western-dominated international financial order and seek to create an alternative that at least puts them on an even footing with other powerful states. The second, more paradoxically, are financial nationalists in core countries of the international financial system like the United States, whose predecessors helped create the current international order and whose citizens benefitted from it for many decades but who nonetheless believe that the system at present disadvantages their nation. Regardless of the nature of the grievance, weakening or destroying the current order is easier than constructing a new one, which only the revisionists in China, discussed in more detail below, currently seem to appreciate.

Combination and Directionality

These resources and constraints combine to produce a certain directionality to illiberal financial nationalist approaches. Having first established a modicum of political control, politicians can be expected to begin their efforts in the upper-left quadrant of Table 2: internal insulating policies are the cornerstone of illiberal financial nationalism. Not only are they often the easiest to implement, but they create the preconditions for successfully pursuing the other three approaches. In Hungary, for example, among the Orbán government’s early targets was the National Bank of Hungary, and the Law and Justice government in Poland likewise used its initial electoral victory to begin taking de facto control over key financial-sector institutions, including the National Bank, the Financial Supervision Authority, and the Finance Ministry (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015).

If they have enough practical power to implement internal insulating policies, illiberal financial nationalist governments may also try to move toward internal revisionist policies and/or toward external insulating ones. The types of policies a particular state emphasizes will depend on the content of its nationalism as well as on the political and economic resources available to it.

To pursue internal revisionist policies, illiberal financial nationalists need a domestic governing coalition that can overcome the objections of holders of foreign currency assets as well as the advocates of such principles as central bank independence. In an era of nationalist ascendency and antiliberal sentiment, it may be relatively easy to garner support for forcing existing foreign-owned banks out of the country, transitioning from majority foreign to majority insider control, and applying new discriminatory financial and access policies. A central bank might be portrayed as an agent of foreign ideas, making bringing it under state control widely palatable at home. Somewhat more difficult may be the mandatory conversion of existing foreign-currency instruments to domestic currency, which multinationals may resist, even if they are domestically owned. There are multiple ways to overcome opposition to such policies, however, including beginning with foreign holders of assets, focusing on politically unpopular actors such as oligarchs or natural-resource exporters, and/or buying off domestic opponents.

If the government can secure the financial wherewithal to support it, it may be possible to increase state ownership of banks or create national development banks that can be used to fund their preferred projects. The government may also privilege national as opposed to international regulatory, clearing, settlement, audit, ratings, or accounting bodies when it believes that doing so will not undermine insider financial institutions. The Reserve Bank of India, for example, has taken this approach by requiring that payment-system data be stored in India, an obvious hurdle for international companies like GooglePay and a boon for such Indian companies as JioMoney (Chacko Reference Chacko2021). Similarly, the Russian government established its own National Card Payment System in June 2014 and began processing payments through it in February 2015 (Krivobok Reference Krivobok2014). Advertisements for the new “MIR” bank card associated with the National Card Payment System assured users, “Your card is free from external factors. Created in Russia” (RFE/RL 2017). In addition, the Central Bank of Russia created a new, Russian-controlled credit-rating agency, the Analytical Credit Rating Agency, in November 2015 (see Analytical Credit Rating Agency 2024). These kinds of policies all depend on access to capital, and, ironically, the institutions and practices of the liberal international financial order help make them available.

External insulating policies require slightly different capacities, beginning with the ability to influence the decision making of external actors. No leader of a small economy, at least without a globally important sector, can hope to persuade international actors to abide by significant restrictions on currency use and investment flows. In contrast, a regional hegemon with an enormous hydrocarbons export sector like Russia can pursue external insulating financial policies far more effectively than a Poland or a Hungary. The Russian government, for example, used the money it raised during the oil boom of the early 2000s to pay off nearly all of its public foreign-currency debt (Johnson and Köstem Reference Johnson and Köstem2016). Another prong of the Russian government’s external insulating financial nationalism has been its concerted effort to promote rubles rather than US dollars in export contract quotation and settlement, an effort that began to bear fruit beginning in 2018 (Central Bank of Russia 2021). The changes have varied across regions, but Russia is steadily reducing its dollar-based trade. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the ensuing international sanctions have only reinforced these earlier trends.

External revisionism is no mean feat. To even consider pursuing it, a government must already have successfully implemented policies from the other three quadrants. Furthermore, an external revisionist state needs the domestic power and international influence that can only reasonably be expected of a regional or global hegemon. Would-be external revisionists believe that because the global liberal financial order does not benefit the nation, it should be upended and transformed everywhere. Doing so, however, requires resources beyond the reach of most countries. In terms of the domestic political economy, these governments need the political strength and acumen to take on potential opponents directly as well as the macroeconomic conditions and tools to discourage or block rapid financial outflows.Footnote 5 Creating an international development bank, for example, requires start-up capital, multiple members, a good reason to join, and a credible pledge to exist for the long term. A system for verifying interstate banking transactions requires analogous capacities. A single state with the initial investment, a large domestic market, and the ability to monitor and enforce compliance has an enormous head start toward creating such an institution that others might join, and if it can also punish them for not joining, so much the better. As discussed in the next section, Russia is the country currently pursuing external revisionist financial nationalism most insistently, although China has the capacity to do so, and nationalist-driven sentiment for an overhaul is a significant political force in the United States, as well.

Evolution and Implications

When contemporary illiberal financial nationalism began to take shape in Hungary after the global financial crisis, many were tempted to write it off as a quixotic experiment that could not be sustained. It was, after all, being attempted in a small country and went against the grain of both the global financial system and the regional economic bloc of which that country was a part. In practice, however, Hungary’s policies have often been relatively successful on their own terms, and more countries, not fewer, have begun to experiment with them. Similarly, illiberal financial nationalism is not simple bluster or merely a smokescreen for elite avarice. Corruption, theft, and manipulation exist in myriad forms of political economy. Both the rhetoric and behavior of these governments centers on an exclusive nationalism; elite enrichment stems more from the increasingly authoritarian context in which financial nationalist policies thrive than from the content of the policies themselves.

Essential for understanding the apparent sustainability of these policies is recognizing how they avoid the mistakes of other economic nationalist approaches. Rather than embracing a crude protectionism or autarky, financial nationalists seek to strategically deploy their country’s financial openness to engage the international financial system on their own terms. Nor do financial nationalist governments automatically run large deficits or drive interest rates down to stimulate their economies. In fact, they have incentives to avoid doing so, as it would undermine the monetary sovereignty they are trying to achieve. Turkish monetary policy under Erdogan is a cautionary tale in this respect (Köstem Reference Köstem2018b; Apaydin and Çoban Reference Apaydin and Çoban2023). Those incentives, in turn, may help them avoid such pitfalls as inflation, currency depreciation, or debt crises. Contemporary financial nationalism also has no intrinsic implications for industrial policy, trade regulations, or nonfinancial enterprise ownership. Old-school protectionism required more and more complex government economic planning and monitoring over time (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1968). Financially focused nationalism does not. In sum, the nature and logic of contemporary illiberal financial nationalist policies do not make them inherently self-destructive.Footnote 6

The apparent staying power and popularity of illiberal financial nationalism has implications both for the domestic environments of the countries pursuing it and for the international liberal financial order. Domestically, contemporary financial nationalism both facilitates and benefits from authoritarian politics. As Piroska (Reference Piroska and Pickel2022, 258) notes for the country in which financial nationalists have gained the firmest grip on political power,

[f]inancial nationalism, as it is advanced in Hungary, severely harms democratic institutions, provides financial resources only to well-connected businesses and unevenly integrates the society into the benefits of the financial nationalist policies. The fact that financially nationalist governments may take advantage of their increasing control over domestic monetary institutions and flows to undermine democratic policymaking is the key Hungarian lesson that future IPE scholarship on financial nationalism should take more seriously.

Illiberal financial nationalism is predicated on an exclusionary definition of the nation, which itself undermines the democratic conception of civil rights. Defining group membership in this way creates justifications for voter suppression, discrimination and violence against legal immigrants, censorship in and beyond education, and more. When exclusionary nationalist motives drive otherwise innocuous financial policies, it poses a real threat to democratic practices.

Moreover, many financial nationalist policies require significant redistribution of economic resources and power, and their advocates often overcome resistance to such redistribution in ways that lay the groundwork for more authoritarian practices. For example, policies challenging foreign bank owners encourage these owners to appeal to the courts. This in turn incentivizes financial nationalist governments to stack the courts, which may then favor the government when it comes to other questions as well. Financial nationalists challenge technocratic and internationally networked central bankers and other civil servants, which provides incentives to defeat these opponents by manipulating bureaucratic politics, altering constitutions, gerrymandering electoral districts, and so on. In pursuit of financial nationalist policies, many leaders have established rules that concentrate their political and economic power as well as trample on civil rights.

Individually, most financial nationalist policies have only minor implications for the sustainability of the international financial system as a whole. Financial globalization continues apace, and insulating policies, whether internally or externally focused (quadrants I and III), and revisionist policies that are internally focused (quadrant II) are all compatible with the international liberal order, even as they seek to take advantage of it. Insulating policies will draw criticism from the IMF and similar organizations, but based on their own internal logics, they may coexist with the system indefinitely. Similarly, even though internal revisionism may challenge the position of global banks, credit card companies, and enforcers of financial standards within particular countries, it does not inherently challenge the international order. Still, if enough states pursue financial nationalist policies, it could make such policies collectively less viable. The success of illiberal financial nationalism relies on a parasitic relationship with globalized finance, and the more extensive spread of these policies could eventually spark a meaningful backlash from the system.

Nevertheless, the most direct threat to the liberal international financial order is external revisionism. The preeminent example of a country pursuing external revisionist financial nationalism after the global financial crisis was Russia, which had moderate success in joining and creating alternative international financial institutions as well as in diversifying international exchanges away from the dollar. The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), for example, launched the New Development Bank during its July 2015 summit in Ufa, Russia, and the Bank’s original home page stated that it was founded “as an alternative to the existing US-dominated World Bank and International Monetary Fund.”Footnote 7 That same year, the Russian government signed on to the new, China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as its third-largest shareholder. Russia also launched the Eurasian Economic Union in January 2015 as a response to the dangers of being too dependent on Western financial structures. The Russian government also sought to expand the use of its own new domestic financial standards institutions to members of the Eurasian Economic Union and beyond (Parliamentskaia gazeta 2019). These measures sought to diminish the hegemony of the US dollar and facilitate ruble use in third-party international transactions, pricing, and reserves. Since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the harsh international sanctions that followed—many focused directly on the financial sector—the Russian government has redoubled its efforts on these fronts.

Russia, however, is not alone. Another state with the potential for significant external revisionism is China, although to date the preferred path of the Chinese leadership has been to engage the international financial system on its own terms rather than replace it, even as the country’s leadership has adopted an increasingly nationalist worldview (see, for example, Helleiner and Wang Reference Helleiner and Wang2019). Most significantly, although it has resisted making its currency fully convertible for decades, it has nevertheless moved slowly in that direction and participated in global financial markets, including voraciously acquiring foreign-denominated reserves. Chinese companies operate smoothly in dollars, euros, and other currencies, and foreign investment is welcomed even though restricted. China wields the power to challenge the international financial order but has so far not seen fit to do so. This could change if and when Chinese leaders believe other countries’ actions have weakened the system in detrimental ways.

Remarkably, prominent political leaders in Great Britain and the United States, the main architects and greatest beneficiaries of the post–World War II international liberal order, also embraced forms of external revisionist financial nationalism. US President Donald Trump’s “America first” rhetoric was explicitly nationalist in its description of the world, arguing that Americans had for too long supported international institutions that only hampered their development. Trump and many British politicians supported Brexit and openly challenged the wisdom of maintaining the European Union or funding global financial institutions. Trump may have done more than any single person to hasten other governments’ diversification away from US dollars in their international reserves. Such rhetoric has had broad resonance in the US political system, and the US state certainly commands the power necessary to undermine the global order. External revisionist impulses by major players should thus be taken seriously, especially because destruction is easier than construction. What might replace the current order is much harder to say, as illiberal financial nationalism itself relies so heavily on exploiting it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rawi Abdelal, Ben Clift, Eric Helleiner, Mark Metzler, Jonathan Kirshner, Hongying Wang, Seçkin Köstem, Ilene Grabel, Waltraud Schelkle, Dóra Piroska, Jerry Cohen, Hyoung-kyu Chey, Julian Gruin, Wade Jacoby, Abby Innes, Yuval Weber, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure

None.