Seit Beginn dieses Planeten hat sich der Himmel niemals wiederholt.

(Since the beginning of this planet, the sky has never repeated itself.)

Blixa Bargeld

The music theater performance Flammenwerfer (flamethrower), created by the international performance theater house Hotel Pro Forma, spectacularly stages an intricate problem with which mental health services, psychiatric organizations, and the field of psychopathology more broadly, have been struggling since their very emergence. This problem concerns a certain incommensurability and incommunicability between two different modes of language: the established and authoritative clinical discourse of the psychiatric organization and the experiential discourse of its patients subjected to and at times resisting this authority. The communicational abyss between these discourses poses not only a clinical problem but also an ethical and organizational challenge that needs to be addressed and that becomes especially critical when considering the services and care offered to persons diagnosed within the spectrum of schizophrenia disorders (SSD). Such persons often suffer from so-called ‘anomalous’ experiences, which are difficult, if not impossible, to express or convey within conventional means of communication (Michaelsen Reference Michaelsen2021). Furthermore, they often report to undergo profound, yet almost ineffable, alterations of their thoughts and language concerning these experiences, gravitating around a sense of desertion and detachment not only from the surrounding world and others, but also from themselves. Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions often develop from the onset of these subtle alterations of experience and language (Parnas and Handest Reference Parnas and Handest2003; Sass et al. Reference Sass, Pienkos, Skodlar, Stanghellini, Fuchs, Parnas and Jones2017). From a clinical viewpoint, SSD thus involves a ‘disturbance’ of experience and language, which the authoritative psychiatric discourse has had a historical tendency to reduce to a pathological silence incomprehensible to and thus excluded from and oppressed by (Bigo Reference Bigo2018) the powerful voice of reason understood as “a monologue about madness” (Foucault Reference Foucault, Murphy and Khalfa2006, xxviii). The ethical demand vis-à-vis such historical silencing concerns not only that professionals in mental health organizations are open or generous to ‘the other’—ethical norms of care and hospitality are already present among mental health care workers. Rather, from an organizations and business ethics perspective, the ethical demand concerns how to relate such interpersonal ethics of care to a practice of organizational justice (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2023).

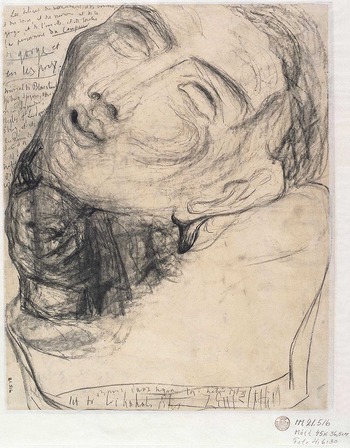

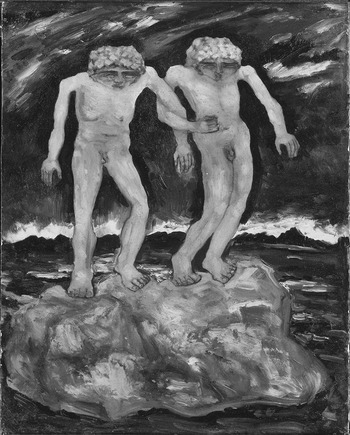

Flammenwerfer stages the problematic issue of incommensurability and incommunicability between the authoritative clinical discourse of psychiatric organizations and the experiential language of persons with SSD with an artistic precision that is invaluable and difficult to convey more clearly or forcefully by any other means. It captures the profoundness of the problem in a way that clinical reports or academic research papers could never imitate—thus subverting the ancient hierarchy of art as an imitation of reality. In this case, art is the only ‘original’ conveyance of the conflictual reality at stake. Flammenwerfer is based on the life and works of the Swedish visual artist Carl Fredrick Hill, whose artistic style changes dramatically in the immediate aftermath of his presumed psychotic breakdown in 1877–78 at the age of 28. For an exemplification of this shift in both style and materials, see Figures 1–4.

Figure 1: C. F. Hill, River Landscape II: Champagne, 1876

Note. Courtesy of the National Museum, Stockholm.

Figure 2: C. F. Hill, Seine: Motif from St Germain, 1877

Note. Courtesy of the National Museum, Stockholm.

Figure 3: C. F. Hill, Man Who Cut His Throat, between 1883 and 1911

Note. Courtesy of the Malmö Art Museum.

Figure 4: C. F. Hill, The Last Human Beings, between 1883 and 1911

Note. Courtesy of the National Museum, Stockholm. Photo by Åsa Lundén, 1994.

Following his breakdown, Hill is diagnosed with ‘incurable insanity’ (this was before the diagnosis of schizophrenia or dementia praecox was coined) at a psychiatric clinic just outside of Paris where he was living at the time and where he remained for two years. After being brought back to Sweden and briefly admitted to a clinic where he protested the treatment he was receiving, Hill spent the remaining years of his life in his childhood home under the care of his mother and sister in almost absolute isolation from the surrounding world until his death in 1911. Hill has been described as working manically and constantly, creating a prolific body of work and leaving behind well over 4,000 works of arts, mainly drawings and paintings but also a book manuscript under the pseudonym “Nagug” entitled Poems and Authorship in a Few Languages, the most extensive collection of which is preserved at Malmö Art Museum.

The difficulty of communicating experiences such as the ones lived by Hill pose a formidable challenge to mental health organizations and professionals aiming to understand and treat SSD. Studies have shown that language may undergo significant alterations in concurrence with such ‘anomalous’ experiences (Pienkos and Sass Reference Pienkos and Sass2017; Rosenbaum and Sonne Reference Rosenbaum and Sonne1987) resulting in a significant hindrance to the prospect of recovery or mitigation challenging not only psychiatric institutions but also to relatives and workplaces that want to support people through mental health crises (Vanheule Reference Vanheule2024). As the psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler—who coined the notion of “schizophrenia”—stated in 1911, difficulties in treatment arise because “the examiner and the patient do not really speak the same language” (Bleuler Reference Bleuler, Zinkin and Lewis1950, 14). Within the tradition of organizing modern psychiatry from the turn of the twentieth century up until the major classification systems of mental disorders of today (i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM], International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD]), there has been a prevalent tendency to regard the language of schizophrenia spectrum disorders as fundamentally “nonsensical” (Kraepelin Reference Kraepelin1915), “incomprehensible” (Jaspers Reference Jaspers1946), “bizarre” or “disorganized” (APA 2013), or not within the realm of language at all (Fuentenebro and Berrios Reference Fuentenebro and Berríos1997). These disturbances of language, which are talked about but not engaged with, are however causing urgent and alarming difficulties for the contemporary organization of psychiatry, which the dominating biomedical paradigm of recent decades has not been able to solve. On the contrary, studies show how mental health services are failing these patients in that 50–75 percent of persons with SSD interrupt their psychiatric treatment after only 1–2 years (Henriksen and Parnas Reference Henriksen and Parnas2014; Leijala et al. Reference Leijala, Kampman, Suvisaari and Eskelinen2021) and research into recovery remains largely neglected (De Ruysscher et al. Reference De Ruysscher, Vandevelde, Vanheule, Bryssinck, Haeck and Vanderplasschen2022). These discouraging results show a need to create an alternative ‘ethical register’ that is “not at the mercy of organizational authority and where ethics is enacted through an ethical subjectivity formed from people’s affective and embodied relations” (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2023, 499). In turn, such an ‘ethical register’ should not abandon collective ethics, but instead be able to affect and transform the current organizational authority of the clinical discourse, turning towards justice and making it more susceptible to the experiential language of its subjects and their difficulties of expression, and thus enable “novel thinking about established forms of knowledge” and thereby open “new vistas of theory development and empirical investigation” (Ezzamel and Willmott Reference Ezzamel and Willmott2014, 1014). The main problem of communicational abyss between mental health organizations and persons with SSD, concerns not only lacking knowledge and understanding in the psychopathological field, but also an inadequacy on the part of the psychiatric organization and discourse to engage with this difficulty for their patients. This dissymmetry between a sedimented organizational discourse and an experiential language that struggles to articulate itself creates an obstacle to the prospect of recovery and prolongs the suffering of psychiatric patients, resulting in a broader societal problem. It is therefore imperative to view the ‘disturbance’ of communication not only from the perspective of the psychiatric organization but also from the persons undergoing the ‘anomalous’ experiences and encountering a psychiatric discourse inadequate to encounter them. This is where artistic practices and aesthetic expressions, such as poetic writing, visual, or performative art may come forward as a ‘third’ mode of language that can help to bridge the communicational abyss not only between the respective languages of clinicians and patients, but also between the ineffable and the effable, thus facilitating an alleviating transfiguration of the potentially isolating and painful exposure to anomalous experiences by making them somehow communicable.

The theatrical performance Flammenwerfer follows a tradition in the arts which has tried to address this communicative abyss and seriously engage with schizophrenic language and artistic expression. Some important examples from various fields are to be found in the complete works of Antonin Artaud (Reference Artaud1970–1994) and in Derrida’s (Reference Derrida1967, Reference Derrida1986) and Deleuze’s (Reference Deleuze1969) incomparable texts on Artaud’s writings and drawings, in Cronenberg’s film Spider from 2002, as well as in various ‘art brut’ collections such as the Halle Saint-Pierre (Paris), the Prinzhorn Sammlung (Heidelberg), or the Collection de l’Art Brut (Lausanne), and museum exhibitions such as “Approaching Unreason” in Palais de Tokyo, Paris, which presents artistic practices as a way to combat forms of systemic violence in mental health organizations and society.

Flammenwerfer ingeniously conveys the communicative abyss between clinical or psychiatric discourse and the experiential and artistic expressions of Carl Fredrik Hill in two main ways: sonically and visually.

First, by interweaving the compositions of the German composers and musicians Blixa Bargeld and Nils Frahm, the performance gives voice both to the authoritative clinical discourse and the experiential language of Hill subjected to and resisting the authority of the clinical discourse. The authoritative clinical discourse is voiced by incumbent definitions of various symptoms and symptom constellations, such as psychosis, hallucination, depression, and anxiety, in the style of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which are sung out by the vocal ensemble IKI and accompanied by the compositions of Frahm. The experiential language of Hill is in turn voiced by the musical compositions and poetic lyrics of Bargeld, which are performed by himself and sometimes crosses the boundaries of what can be communicated by words into high-pitched, bird-like noises, cries, and screams—akin to the “breath-words” and “cry-words” of Artaud (Deleuze Reference Deleuze1969, 108). See Figures 5 and 6. Here language borders on the verge of the ineffable, the inexpressible, and even of the inhuman—almost as if language folded back on itself in a remembrance of its own archaic, painful, and enjoyable origins in meaningless sounds, repetitive babblings, and cries. It is beautiful to the point of the unbearable.

Figure 5: Flammenwerfer, Blixa Bargeld screaming, 2024

Note. Photo by Emma Larsson.

Figure 6: Flammenwerfer, Blixa Bargeld in front of Hill, 2024

Note. Photo by Emma Larsson.

Second, visually the performance stages the communicative abyss by the employment of several effects. By maintaining a great physical distance between Bargeld and the vocal ensemble, the performance mimics in its own way the role of the choir in the Greek tragedies, which comments and reflects on the events and protagonists of the play, but hardly ever intervenes directly. This distance also reflects the alienating experience reported by many patients in the psychiatric system of being examined and commentated on but not really interacted with. The trouble of communicating anomalous experiences is therefore increased by the fact that even trained psychiatrists are not always capable to facilitate self-descriptions by the patients. On the contrary, studies show that even when patients actively try to talk about their anomalous experiences or psychotic symptoms, the psychiatrists often avoid further exploration (McCabe et al. Reference Rosemarie, Heath, Burns and Priebe2002; Steele, Chadwick, and McCabe Reference Steele, Chadwick and McCabe2018; Stephensen, Urfer-Parnas, and Parnas Reference Stephensen, Urfer-Parnas and Parnas2024). Suicidal ideation in schizophrenia spectrum disorders is in fact associated with the experience of an unbearable isolation and loneliness due to difficulties in interacting, communicating, and participating in common daily life with other people (Škodlar, Tomori, and Parnas Reference Škodlar, Tomori and Parnas2008). Furthermore, by displaying the artworks of Hill on stage in a dynamic manner where they transform from transparency and vague visibility to untransparent visibility and by locating the vocal ensemble either behind or in front of these art works (see Figures 7 and 8), the performance stages both the fluctuating dominance of the clinical or the experiential discourses, as well as the always ‘missed encounter’ (Lacan Reference Lacan and Sheridan1978) between the two.

Figure 7: Flammenwerfer, transparency, 2024

Note. Photo by Emma Larsson.

Figure 8: Flammenwerfer, intransparency, 2024

Note. Photo by Emma Larsson.

By so clearly and powerfully staging the clinical, ethical, and organizational problem at hand, the performance of Flammenwerfer can remind us that the understanding of SSD, as of any disorder, is inextricable from an understanding of the experience of disturbances at both sensible, linguistic, and reflective levels of selfhood and subjectivity formation. The still unanswered questions of communicating experiences bordering on the ineffable are as ethical, aesthetic, and organizational in nature as they are clinical or psychiatric (Marquard Reference Marquard, Norman and Welchman2004). Therefore, development of an adequate theoretical framework for understanding the complex nature of SSD, and not least how these disorders are perceived, sensed, and experienced from a subjective point of view, requires a sustained interdisciplinary effort. Psychiatric institutions need to join forces with the arts as well as organizational ethics scholars to ensure the dignity of their patients and their experiences (Pless, Maak, and Harris Reference Pless, Maak and Harris2017). An ethical register in which an unconventional cross-fertilization between the fields of art theory, philosophical aesthetics, business ethics, organizational studies, psychoanalysis, psychopathology, and psychiatry can unfold is called for to surpass the state-of-the-art and develop novel approaches and solutions to the unsolved problem of the communicative abyss between clinical discourse and the experience of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Showcasing the relational, affective, and normative aspects of the problem at hand, this effort is both an ethical and organizational demand if services in mental health organizations are to have any chance of becoming a tool to combat deep forms of systemic and discursive violence for persons with SSD.

Cathrine Bjørnholt Michaelsen (cbm.bhl@cbs.dk, corresponding author) is assistant professor at Copenhagen Business School. Her research takes place at the intersections of deconstruction, psychoanalysis, phenomenology, business ethics, and organization studies, centering on questions of subjectivity-formation in organizations and society. Her research foci are the relations between selfhood and otherness, experiences of alienation, anxiety, boredom, depersonalization, and solitude, and questions of responsibility, thoughtlessness, and undecidability. Her published works include the monograph Remains of a Self: Solitude in the Aftermath of Psychoanalysis and Deconstruction and contributions in Business Ethics Quarterly, Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, Comparative and Continental Philosophy, and International Journal for Philosophical Studies.

Ana Maria Munar is associate professor at Copenhagen Business School. Her scholarship is postdisciplinary and characterized by the application of experimental writing, critical theory, and philosophical thought to study social phenomena. Her latest book is Desire: Subject, Sexuation and Love (Punctum Books), an exploration of desire through Lacanian psychoanalysis, philosophy, art and literature. Her passion lies in philosophizing and developing creative academic communities, where love and joy are possible. One of these is the Critical Tourism Studies network that she co-chaired together with Professor Kellee Caton. Her philosophical and gender research combines academic publications with advocacy and action research projects.