Introduction

Throughout the late 20th and 21st centuries, women’s parties have consistently formed across European countries, seeking to improve women’s descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020). These parties often emerge in response to mainstream parties’ failures to adequately address gender issues. Where they appear, mainstream parties have increased their share of women candidates (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2011, Reference Cowell-Meyers2014) and devoted greater attention to gender issues (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2017; Dominelli and Jonsdottir Reference Dominelli and Jonsdottir1988; Levin Reference Levin1999). Since the 2010s, a wave of explicitly feminist women’s parties has emerged, achieving regular local and regional representation, and actively pushing mainstream parties to take gender issues more seriously. For example, the UK Women’s Equality Party (WEP) during the 2016 London mayoral election pressured mainstream candidates to address childcare and domestic violence (Stewart Reference Stewart2016). Similarly, after Sweden’s Feministiskt Initiativ secured the first ever European Parliament (EP) seat for a women’s party in 2014, mainstream parties increased their attention to gender issues in subsequent elections (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2017).

Women’s parties thus play a potentially significant role as “entrepreneurs” (Hobolt and De Vries Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015) of gender issues, increasing their salience on the policy agenda. However, despite their consistent emergence and apparent impact, there is limited systematic knowledge of the full range of issues they mobilize. Existing research primarily comprises case studies that examine individual women’s parties’ formation, organization, and electoral performance (Cockburn Reference Cockburn1991; Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2011, Reference Cowell-Meyers2014, Reference Cowell-Meyers2020; Dominelli and Jonsdottir Reference Dominelli and Jonsdottir1988; Evans and Kenny Reference Evans and Kenny2019, Reference Evans and Kenny2020; Levin Reference Levin1999; Slater Reference Slater and Lane1995; Zaborsky Reference Zaborszky1987). Meanwhile, wider research on party families often ignores women’s parties (Langsæther Reference Langsæther2023) or dismisses them as single-issue parties (Wagner Reference Wagner, Carter, Keith, Sindre and Vasilopoulou2023), overlooking their potential to engage with a broad array of issues. And while some research has demonstrated that women’s parties can shape mainstream parties’ attention to gender issues (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2017), there is a lack of comparative empirical analysis of their issue appeals and overall influence.

This paper addresses that gap through a novel comparative investigation of the issue concerns of European women’s parties. This advances knowledge of the women’s party family by systematically analyzing their issue emphases while also contributing to wider discussions of gender representation and the collective definition of “women’s issues.” Do women’s parties exclusively focus on traditional concerns such as childcare and equal pay, or do they engage with broader issues like economic justice, migration, or environmental policy? This also informs knowledge of the wider representation of gender issues, signaling areas where feminist actors perceive mainstream parties as insufficiently addressing gender concerns or where backlash the gender equality threatens existing rights.

Particularly, by mapping women’s parties’ issue concerns, this study lays the empirical foundation for future research into how gender issues are politicized and contested in electoral politics. While individual case studies suggest that women’s parties have successfully pressured mainstream parties to increase women’s representation (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2011, Reference Cowell-Meyers2017), their broader impact on political agendas remains difficult to assess, precisely because we lack systematic knowledge of their issue concerns. At the same time, many women’s parties are short-lived and electorally unsuccessful, while in contrast, far-right parties have increasingly successfully mobilized anti-feminist positions (Reinhardt, Heft, and Pavan Reference Reinhardt, Heft and Pavan2024). The ability of women’s parties to survive and influence policy depends on their ability to identify a distinct gap in the policy space and to articulate issues that resonate with voters. Previous research has explored these dynamics in individual cases (Evans and Kenny Reference Evans and Kenny2019), but a comparative perspective is needed to understand broader patterns.

To analyze women’s parties’ issue concerns I collect an original dataset of European women’s party manifestos covering the period 1990–2020, the largest to date. Using a mixed-method text analysis approach, I combine computational text analysis techniques, including structural topic modelling, with a manual thematic analysis. I ask first, what common concerns, if any, characterize women’s parties? I then examine whether women’s parties can be differentiated based on their issue emphases.

Drawing on established frameworks of the substantive representation of women (Molyneux, Reference Molyneux1985, Reference Molyneux1988), previous literature has conceptualized two primary types of women’s parties with distinct issue orientations. Essentialist women’s parties tend to emerge in contexts of political and economic instability, prioritizing women’s material needs without necessarily challenging patriarchal institutions and structures (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003; Shin Reference Shin2020). In contrast, feminist parties, which are more prevalent in advanced industrialized democracies, advocate explicitly feminist platforms (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016, 16; Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin, Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020; Shin Reference Shin2020). While these categories are well-established in theory, empirical research has yet to systematically examine whether the supposed difference in issue emphasis exist in reality.

This study provides, to my knowledge, the first systematic empirical test of these distinctions. I find that European women’s parties across contexts share core concerns regarding equal rights for women and minority groups, as well as social policy, particularly in areas that disproportionately affect women. However, my findings also reveal a substantive difference in issue concern between essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties that transcend specific emergent contexts. Feminist parties emphasize a distinct set of issues, including gender-based violence and human security, which are absent from essentialist women’s parties’ manifestos and frame shared issue concerns around structural gender inequality. These results contribute to a more nuanced understanding of women’s parties and sets the stage for future research to explore their role in shaping gender representation, influencing the policy offerings of mainstream parties, and directly competing with far-right anti-gender equality positions.

Conceptualizing Women’s Parties

The first step in analyzing women’s parties’ issue concerns is to define what is and what is not a women’s party. The first working definition of a women’s party for comparative research is offered by Cowell-Meyers (Reference Cowell-Meyers2016, 4) as “autonomous organisations of or for women that run candidates for elected office,” whose aim is to “advance the volume and range of women’s voices in politics.” This definition establishes three important characteristics of women’s parties. First, they are political parties that run candidates for elected office. A fact that separates women’s parties from women’s social movements or women’s advocacy groups.

Second, women’s parties are formed predominantly by women. Specifically, women who feel a “perception of exclusion from mainstream political processes” (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016, 16) and a frustration with the lack of women’s representation, either descriptively or substantively. Evidence from both East (Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003) and West (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016) Europe demonstrates that supply-side factors for the emergence of a women’s party include a population of women with relatively high socioeconomic and educational empowerment but with comparably low political representation.Footnote 1

Third, women’s parties are formed for women. Their central aim is to improve women’s political representation descriptively, substantively, or symbolically (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020, 12). This mobilization around gender identity separates women’s parties from other parties that may have a high proportion of women members, candidates, or leaders but who do not take gender as their “principal organisational and analytical focus” (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020, 6; Shin Reference Shin2020).

This appeal for greater women’s representation may take different forms across parties. In addition to seeking descriptive electoral representation, women’s parties may also pursue policy-seeking strategies to further the substantive representation of women. For example, consciousness raising was an important goal of several women’s parties in the 1980s and 1990s (Levin Reference Levin1999; Zaborsky Reference Zaborszky1987). Contemporary women’s parties have been more explicit about their aims to influence the policy offers of other parties. For instance, ahead of the 2017 UK General Election, the WEP launched the “Nickable Policies” campaign, delivering their manifesto to each competitor party’s head office with the words “Steal Me” printed on the cover. Parties have also allowed members to hold joint membership with other parties, seeking to increase women’s descriptive and substantive representation across politics more broadly (for example, Germany’s Feministische Party Die Frauen [2021, 8]).

In pursuing these explicit policy-seeking strategies, contemporary women’s parties potentially function as entrepreneurs of gender issues (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Hobolt and De Vries Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015). By repeatedly emphasizing specific gender issues they may increase their salience among voters and the media, thereby encouraging mainstream parties to take them up. Case study research suggests that women’s parties have had success in putting women’s issues on the agenda (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2011, Reference Cowell-Meyers2014, Reference Cowell-Meyers2017; Dominelli and Jonsdittir Reference Dominelli and Jonsdottir1988; Levin Reference Levin1999). Notably, in one of the few studies to empirically examine the contagion effect of women’s parties, Cowell-Meyers (Reference Cowell-Meyers2017) finds that mainstream parties in Sweden devoted greater attention to gender issues in their manifestos following the emergence of the Feministiskt Initiativ as a viable contender in the 2014 EP elections.

However, to further investigate women’s parties’ role in the increasing salience and competition over gender issues, we need an established empirical understanding of parties’ individual and collective issue concerns. The existing literature is predominantly comprised of case studies on singular parties. Moreover, in comparative work, the goal of the party family is defined deliberately broadly as a “desire for gender equality, meaning that women and men should have equal citizenship rights and a pro-women perspective on social justice” (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020, 13). This breadth acknowledges that the concept of gender equality can vary across individual parties and different sociopolitical and cultural contexts (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020; see also Beckwith Reference Beckwith2000, 437). However, the disadvantage of this deliberately broad definition is that it offers little indication of exactly how women’s parties mobilize around the shared identity of sex/gender or what specific issues they emphasize in their party platforms. Consequently, the first exploratory question that I address in this paper is:

RQ1: What are the shared issue concerns of the women’s party family?

Essentialist Women’s Parties and Feminist Parties

Establishing the shared issue concerns of women’s parties is an important first step. However, scholarship on the substantive representation of women (SRW) has consistently emphasized that women are a heterogenous group with varied (intersectional) interests (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014; Sanders, Gains, and Annesley Reference Sanders, Gains and Annesley2021). This makes it problematic for comparative empirical research to group parties with potentially different issue concerns into a single analytical category. Instead, it is preferable to consider “women’s parties” as the wider party family, encompassing any political organization that fields candidates for elected office on a platform that seeks to improve the representation of women. Empirically, identifying sub-types of women’s parties, which share greater commonalities issue focus, provides a more useful analytical framework.

SRW scholarship has explored various approaches to conceptualizing and categorizing the representation of women’s interests (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985; Reference Molyneux1988; Reingold and Swers Reference Reingold and Swers2011). One of the most well-established frameworks is Molyneux’s (Reference Molyneux1985, Reference Molyneux1988) distinction between women’s practical interests, which emerge from their position within the gendered division of labor, and women’s strategic interests, which aim to dismantle structures that perpetuate women’s subordination. Similarly, Htun and Weldon’s work on gender equality policies (Reference Htun and Weldon2010, Reference Htun and Weldon2018) distinguishes between policies that seek to improve women’s class-based interests and those that represent women’s interests as a status group. These frameworks highlight that an actor’s pursuit of SRW can have different foci, from improving women’s material living conditions to striving for equality between women and men (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008, 106). For women’s parties, this may manifest as distinguishable issue emphases.

Applying these SRW frameworks to parties, Shin (Reference Shin2020) develops a theoretical typology of three categories of women’s party, based on their approach to women’s substantive representation. First are “proactive women’s parties” which predominantly focus on women’s practical concerns and material needs. Second are “feminist” parties which emphasize women’s strategic concerns. The third category, “reactive women’s parties,” is defined as including parties mobilized by women but that either place a low priority on women’s concerns or actively promote anti-gender equality policies. However, this category raises conceptual challenges, as defining a party as a women’s party implies a commitment — however varied — to advancing gender equality (Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020). Moreover, it is illogical to group together parties in the same party family that hold diametrically opposing ideological views. Given these concerns, I do not adopt the “reactive” category in my categorization.

Otherwise, the “proactive” and “feminist” categories offer a promising conceptual foundation to classify women’s parties and explore their issue emphasis. Moreover, the distinction has been observed in Cowell-Meyers’ (Reference Cowell-Meyers2016) empirical research on patterns in the emergence of women’s parties, in which she identifies two broad categories. First are essentialist women’s parties (what Shin [Reference Shin2020] labels “proactive”), which typically emerge in contexts of political and economic turbulence — such as states undergoing democratic transition — to ensure that women’s voices are included in the development of new political institutions and processes (Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003). Examples include women’s parties that emerged in Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union, such as Russia’s Zhenshchiny Rossii (Women of Russia [WOR]), Armenia’s Shamiram Party, and Belarus’ Nadzeya (Hope). These parties are generally formed as a representative branch of an existing women’s movement, with platforms focused partly on protecting women’s democratic and social rights but predominantly on securing women’s material needs, rather than advocating for broader social reorganization (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016).

Second are feminist parties, which typically form in established democracies and post-industrial economies, often in Western Europe. In these contexts, there is a relatively high proportion of women in the labor market and in political institutions, yet women feel their substantive representation is lacking (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016; Shin Reference Shin2020). Feminist parties are more often formed by political and social elitesFootnote 2 and commonly self-identify as feminist, for example, Finland’s Feministinen Puolue (Feminist Party [FP]), the UK’s WEP,Footnote 3 and various branches of “Feminist Initiative” in Denmark, Norway, Poland, Spain, and Sweden. These parties arguably do not seek to represent women en masse, but to represent feminism as an ideological position. Their membership is often open to men, and some, such as Finland’s FP and Sweden’s Feminist Initiativ, have had male leaders. Their platforms tend to focus on strategic gender interests, advocating policies that directly challenge patriarchal structures and institutions, including broader cultural and political concerns. For example, in 2019, feminist parties across Europe formed the Feminists United Network (FUN) and developed a common platform for the 2019 EP elections, which included positions on the environment, asylum, and challenging right-wing nationalism (Feministiskt Initiativ 2019).

Combining conceptual SRW frameworks with existing empirical research provides a strong rationale for distinguishing between two types of women’s party that emphasize substantively different issues. However, it is important to clarify that while essentialist women’s parties are distinguished from feminist parties, this does not imply that they are not feminist actors (in this paper, I use essentialist women’s parties rather than “proactive” (Shin Reference Shin2020) as it offers a more substantive indication of parties’ approach to women’s representation), rather that they do not claim to represent “feminism” as an ideology. At the same time, it is important to recognize that feminism itself is ideologically diverse, encompassing perspectives such as liberal, radical, and socialist feminism, which may emerge as different policy concerns across as well as within parties. While more granular ideological distinctions may be valuable in certain analyses — such as examining intra-party debates (for example, Evans and Kenny Reference Evans and Kenny2019) — they are less suited to the objectives of this study, which aims to develop broader, analytically meaningful categories that enable cross-national analysis.

For this purpose, the binary classification of essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties strikes an effective balance between theoretical clarity and empirical applicability. It follows the common comparative party politics approach wherein party families are defined based on core ideological themes, while subgroups are identified by their emphasis on specific issues/policies (Ennser Reference Ennser2012; Langsæther Reference Langsæther2023; Mudde Reference Mudde1996). Distinguishing parties by a focus on women’s material conditions versus aims to transform gender hierarchies provides a structured yet flexible typology for comparative research that accommodates internal variation. This broad distinction has previously been used to classify women’s organizations (Alvarez Reference Alvarez1990; Beckwith Reference Beckwith2000; Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985, Reference Molyneux1988) and to analyze the representation of women’s interests in mainstream parties’ platforms (Sanders, Gains, and Annesley Reference Sanders, Gains and Annesley2021; Sanders and Gains Reference Sanders and Gains2024).

Applying this framework to women’s parties’ platforms also reflects the practicalities of empirical comparative analysis. Extant research has linked differences in women’s parties’ platforms to the specific sociopolitical contexts of their emergence (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016). Indeed, party platforms are not developed in isolation but are responsive to their broader political and social environments. For instance, Htun and Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2010) highlight the significance of democracy, state capacity, and institutions in the implementation of gender equality policy, while Shorrocks (Reference Shorrocks2018) finds that Western European voters became significantly less likely to support traditional division of social roles between 1990 and 2010. However, while these contextual factors shape women’s parties’ agendas, issue-based classification provides a more dynamic and flexible framework for understanding their role in party competition.Footnote 4 Unlike static classifications based on party origin, an issue-centered approach allows parties to shift between the essentialist women’s party and feminist party categories as their priorities evolve. At the same time, it acknowledges that SRW exists on a spectrum, where parties’ platforms may incorporate both practical and strategic gender interests. To empirically evaluate whether these theorized differences in issue emphasis exist in practice, the second research question I ask is:

RQ2: Do essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties emphasize different issue concerns?

Data and Methods

Data

To answer my research questions, I collected an original dataset of European women’s party manifestos published 1990–2020. Party manifestos are a well-established source for comparative study of party ideology, issue emphasis, and policy positions and have been widely used to examine party salience and position on gender issues (Cabeza Pérez, Alonso Sáenz de Oger, and Gómez Fortes Reference Cabeza Pérez, de Oger and Fortes2023; Childs, Webb, and Marthaler Reference Childs, Webb and Marthaler2010; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2019; Sanders, Gains, and Annesley Reference Sanders, Gains and Annesley2021; Weeks et al. Reference Weeks, Caravantes, Espírito-Santo, Lombardo, Stratigaki and Gul2024).

Manifestos are particularly valuable for examining the issue concerns of small parties, like women’s parties, for whom there is often little alternative data such as press releases, political speeches, or internal party documents (Mudde Reference Mudde2013). While manifesto data comes with certain shortcomings — for example, policy inclusion may be strategically constructed to accommodate internal factions — they remain a reliable indicator of parties’ collectively endorsed policy agendas.

I focus on manifestos produced between 1990–2020 as the breadth of this 30-year period allows me to examine changes over time and differences across party type. While women’s parties did compete in European countries before 1990 (for example Iceland’s Kvennalistinn [Women’s List] won parliamentary seats throughout the 1980s), research indicates a higher concentration of women’s parties from 1990-onward (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2020, 9).

I identified 54 women’s parties operating in Europe 1990–2020 by searching existing literature, electoral databases, and news archives using keywords common in women’s party labels, such as “woman/women,” “feminist,” “mothers,” and “daughters.”Footnote 5 I then collected manifestos for these parties from both first- and second-order elections in order to construct the most comprehensive dataset possible. While a small number of manifestos are available from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Burst, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2023), I retrieved most manifestos from party websites and national political archives or library collections. The final dataset comprises 45 manifestos from 20 women’s parties across 18 European countries (Appendix A1). Hence, for 34 of the 54 identified parties, no accessible manifesto could be found. This is (to my knowledge) the most comprehensive dataset of women’s party manifestos to date.

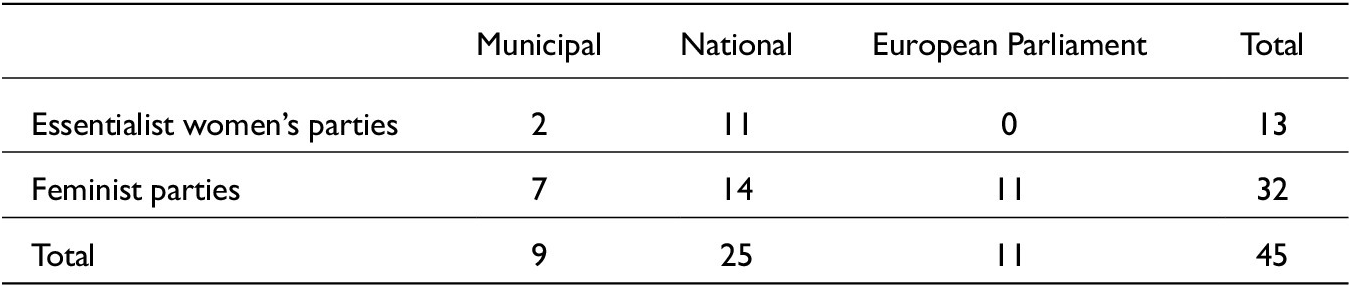

Next, I categorized each party as either an essentialist women’s party or feminist party using party labels, characteristics of parties’ emergent conditions, and classifications from prior research (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016; Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003). These categories are of course ideal types and some parties present “blurred” cases. For example, the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition (NIWC) emerged in a period of political instability during the 1990s peace process but has been identified in previous research as having a platform oriented toward gender equality (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2017). However, as NIWC themselves consistently rejected the label of a feminist party (Cleary Reference Cleary1996), I categorize them as an essentialist women’s party, in line with their emergent conditions. Overall, the dataset comprises 13 manifestos from nine essentialist women’s parties and 32 manifestos from 11 feminist parties (Table 1).Footnote 6

Table 1. Summary of women’s party manifesto data

Notes: A full summary of the manifesto dataset can be found in Appendix A1.

Finally, I translated all non-English manifestos into English using the Microsoft Translator API. Empirical testing has demonstrated that machine translation produces reliable results in comparison to either human translation or multilingual methods, particularly when using bag-of-words techniques like topic modelling (de Vries, Schoonvelde, and Schumacher Reference de Vries, Schoonvelde and Schumacher2018; Licht et al. Reference Licht, Sczepanski, Laurer and Bekmuratovna2024; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Nielsen, Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2015; Windsor, Cupit, and Windsor Reference Windsor, Cupit and Windsor2019).

Methods

Existing approaches for measuring parties’ issue concerns, such as the CMP code scheme (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Burst, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2023) are not presently applicable to women’s parties’ manifestos, because they lack granular coding of gender issues. For this reason, I implement a sequential mixed method text analysis design to identify issue concerns (visualized in Appendix A2). First, I apply computational text analysis techniques to examine patterns in issue emphasis across the full dataset. Second, I conduct a thematic analysis of a sub-sample of manifestos to provide closer examination of parties’ positions and issue framings. This combination balances the broad comparisons facilitated by large-scale text analysis with the depth of qualitative interpretation.

Computational Text Analysis

To prepare the texts for computational analysis, I constructed a corpus of translated manifestos and applied standard pre-processing techniques. These include tokenizing the texts into individual words, compounding commonly occurring multi-word expressions, lowercasing, removing standard English stopwords and a dictionary of party names (Appendix A3), stemming words to their root form, and trimming very rare terms (appearing fewer than three times in the full corpus). Each of these steps reduces “noise” in the data, ensuring that computational techniques capture meaningful patterns.

My first aim is to identify shared concerns in women’s party manifestos, and secondly, to test differences in issue emphasis between essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties. To achieve this, I first conduct word frequency analyses to identify the most commonly used terms in manifestos. This provides an initial indication of the dominant issues, their evolution over time, and variation across party type. Then, to identify broader themes across manifestos, I fitted a structural topic model (STM) (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2019). Topic modelling is an unsupervised machine learning model that detects latent, semantically coherent “topics” by clustering terms that frequently co-occur within and across texts (Eisele et al. Reference Eisele, Heidenreich, Litvyak and Boomgaarden2023, 210). This method enables an inductive examination of deeper themes in manifestos, whether issue-related, ideological, or procedural. I implemented a model with five topics, as diagnostic tests (Appendix A5) indicated this number would optimally balance the frequency of terms within a topic and their exclusivity to that topic compared to another. I evaluated the top terms associated with each topic and assigned labels based on their substantive content.

A key advantage of STM over other topic modelling approaches is its ability to incorporate document-level metadata, allowing for statistical tests of topic prevalence across different variables (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2019, 2). Hence, to empirically assess whether the theorized distinction between essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties is reflected in their substantive platforms, I included party type as a covariate in the model. I then ran a linear regression to estimate differences in topic prevalence between the two types of women’s party.

Manual Thematic Analysis

Following the computational analysis, I conducted a manual thematic analysis of a sub-sample of six manifestos (Table 2) to more deeply investigate similarities and differences in issue concern and issue framing. The sample of parties was selected to reflect diversity in political system, time period, sociopolitical context of party emergence, and variation in issue concern as indicated from the quantitative analyses. Due to these choices, the manifestos within the subsample also cover different election types. Homogeneity over election-type would have been preferable, but I prioritized selecting a sample that represented variety in parties’ emergent conditions and supposed issue focus.

Table 2. Sub-sample of women’s parties’ manifestos for thematic analysis

To summarize the sample: WOR is a classic example of an essentialist women’s party, emerging in the post-USSR period and promoting a party platform centered on political and economic stability. Bulgaria’s Partiya na Bulgarskite Zheni (Party of Bulgarian Women [POBW]), whilst not emerging in a period of democratic transition, existed in a tumultuous political system, and explicitly branded itself as a nonfeminist party promoting traditional Christian values. The Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition (NIWC) presents one of the most blurred cases. Although formed in period of unstable political transition and explicitly not identifying as a feminist party, it nevertheless promoted a platform containing strategic gender equality issues. Spain’s Iniciativa Feminista (Feminist Initiative [IF]), the UK’s WEP, and Finland’s FP are all self-identified feminist parties that emerged in established democracies but do not necessarily occupy the same space on the spectrum of feminist thought and activism.

I followed the well-established iterative coding process developed by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). From deep reading of the manifestos, I generated a set of initial policy-related codes, such as “education” and “economics,” as well as discourse/narrative codes, such as “intersectionality” (the codebook was also informed by the results of the computational analyses). I then systematically coded the manifestos, reflecting on and modifying the codebook throughout the process and re-coding the data accordingly. Once a point of satiation was reached in which no more relevant codes could be identified, I holistically reviewed the codes and identified common themes and sub-themes across the manifestos, both in issue concern and issue framing (full thematic analysis codebook in Appendix A3).

In the following section, I present the quantitative and qualitative results together, to offer a comprehensive interrogation of similarities and differences in issue concern and issue framing across women’s parties’ manifestos.

Women’s Parties’ Shared Issue Concerns

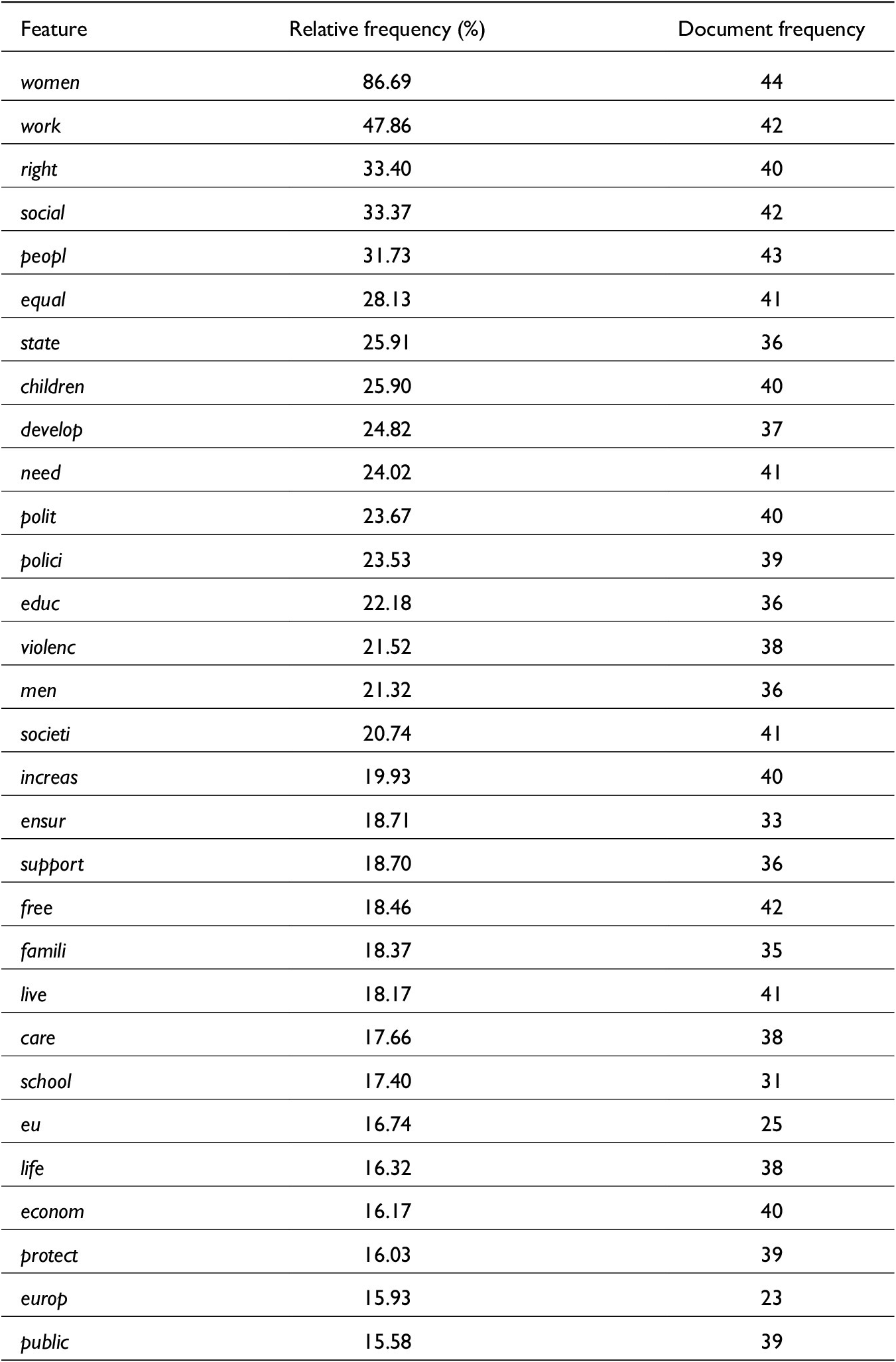

My first research question is what, if any, issue concerns are shared across the women’s party family. An initial quantitative analysis of the most relatively frequentFootnote 7 terms in the 45 manifestos (Table 3) shows that the most common terms relate to women’s rights and equality, including “women,” “right,” and “equal.” These terms were present in least 90% of the manifestos, underscoring their centrality across parties’ platforms.

Table 3. Top 30 terms with highest relative frequency in women’s parties’ manifestos 1990-2020

Appeals to equality also emerged as a highly prevalent theme in the thematic analysis, although parties were in fact vocal about equal treatment of all people, not only women. For example, Finland’s FP begin their manifesto: “we defend human rights and place the principle of non-discrimination at the heart of politics” (FP 2019). WOR claim to defend the “the rights and interests of Russian Citizens, regardless of gender, nationality, social status, religious beliefs and political views” (WOR 1993). Moreover, where women’s parties do discuss gender equality, it is often framed within a broader narrative of social justice. A recurring message articulated in the UK’s WEP manifesto (WEP 2017) is that “equality is better for everyone.” In fact, in the case of Bulgaria’s POBW, the central focus of the party platform is social justice for all people, without specific mention of gender equality.

This framing of gender equality within a broader social justice discourse may indicate a strategic effort to appeal beyond a women-focused electorate. Related to this commitment to social justice, terms such as “children,” educ[ation],” “social,” “care,” and “famili” indicate an overarching concern with social policy, particularly in areas like childcare and support for vulnerable women. Manifestos across the sample frequently advocated childcare policies framed around equality of access and the benefits to wider society:

Preservation of the state system of preschool and out-of-school children’s institutions and ensuring their accessibility for every family. (WOR 1993)

High-quality, affordable day-care should be available to all who need it. (NIWC 1998)

States ensure sufficient and quality public services for the care of dependents and minors from age 0 to 3 or until the date of entry into standardized education. (IF 2009)

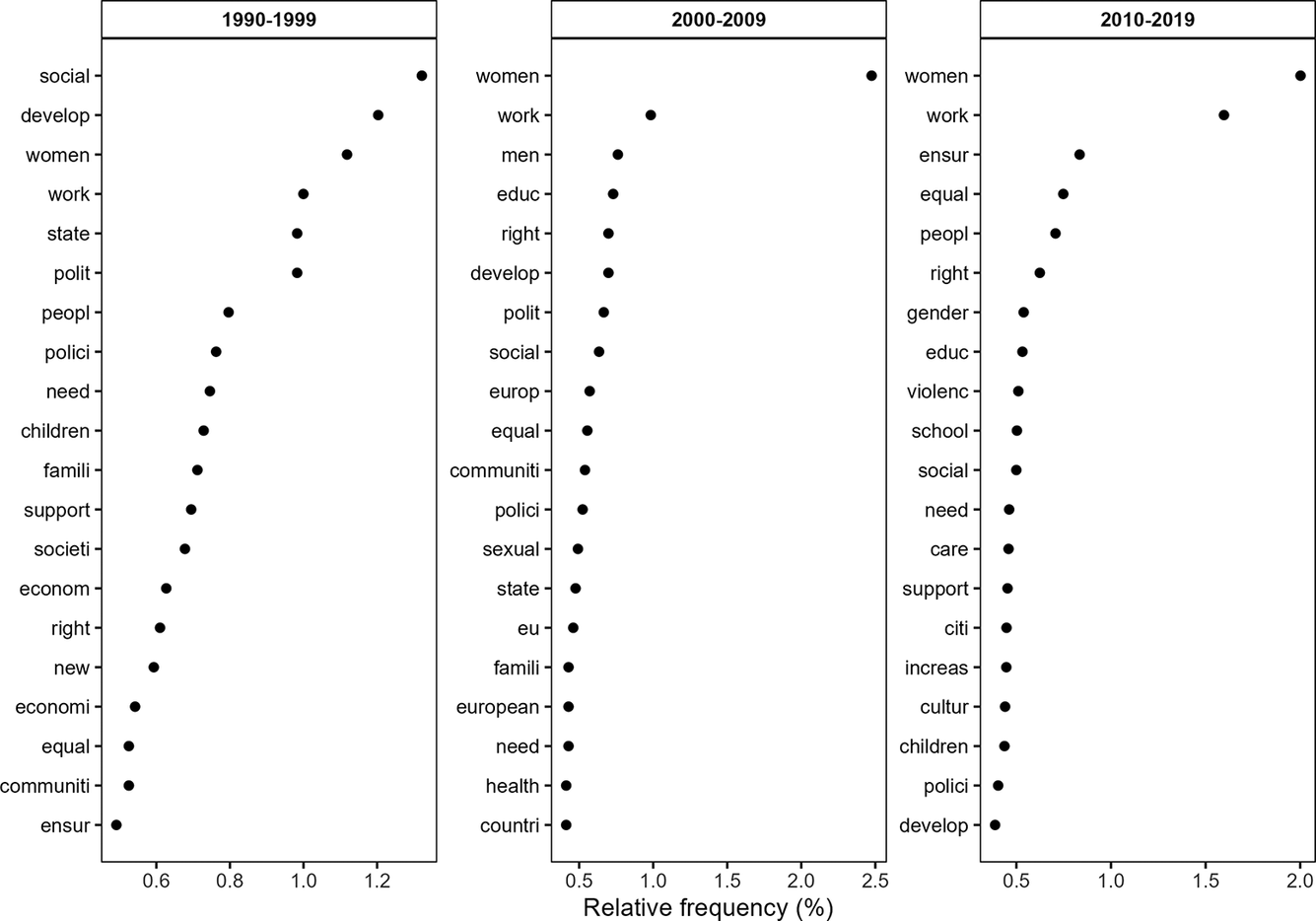

This emphasis on social policy is also a consistent trend over time, as shown in Figure 1, which plots the 20 most frequent words (weighted by document length) in manifestos published in each decade of the 30-year time period. Terms like “social,” “children,” and “famili” are consistently frequent over time. Meanwhile, “educ[ation]” emerges as an increasing priority in manifestos published between 2000–09 and 2010–20, and “care” and “school” are among the most frequent terms in the 2010–20 group.

Figure 1. Top 20 relatively frequent terms in women’s parties’ manifestos 1990–2020 by decade.

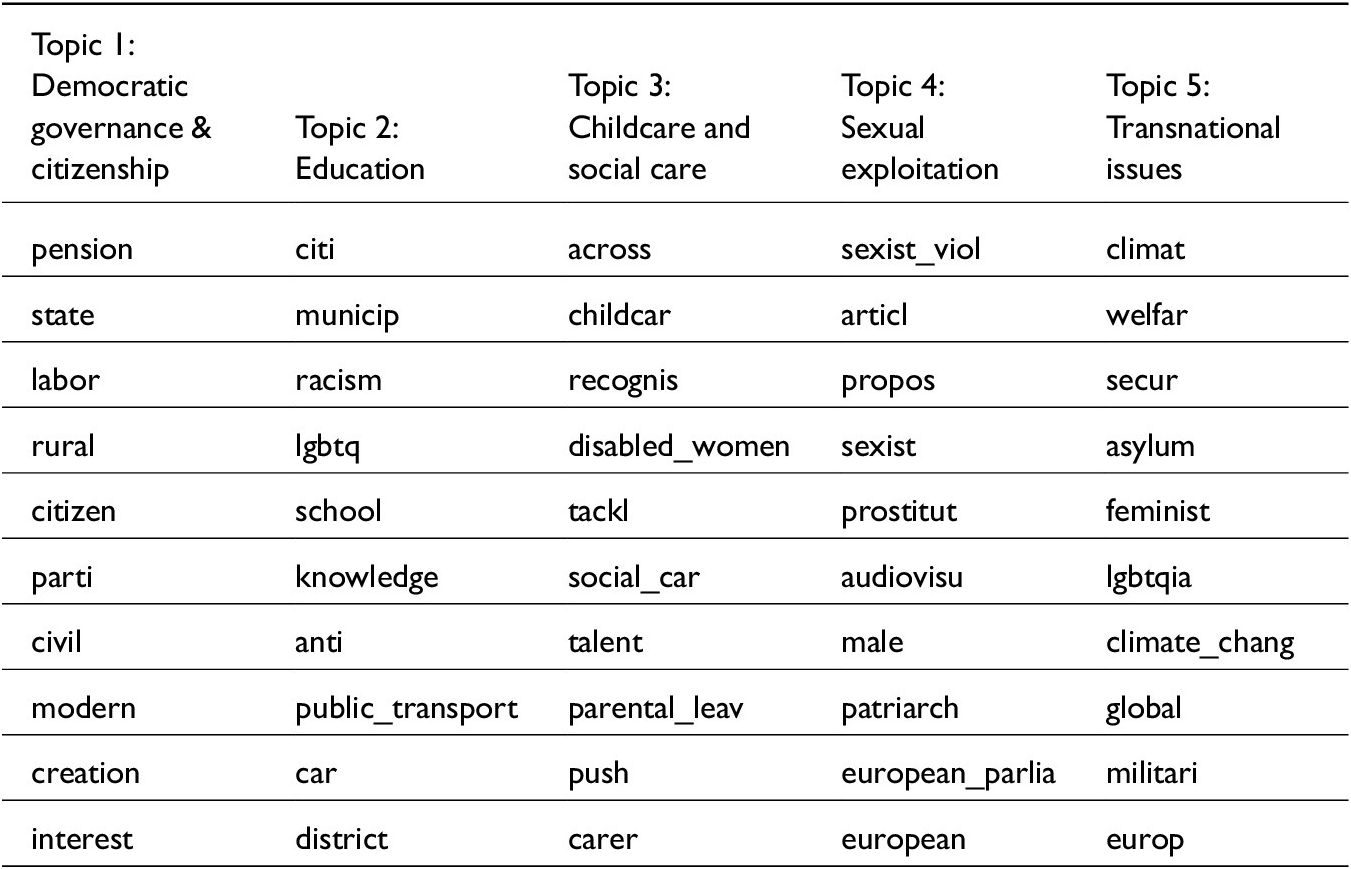

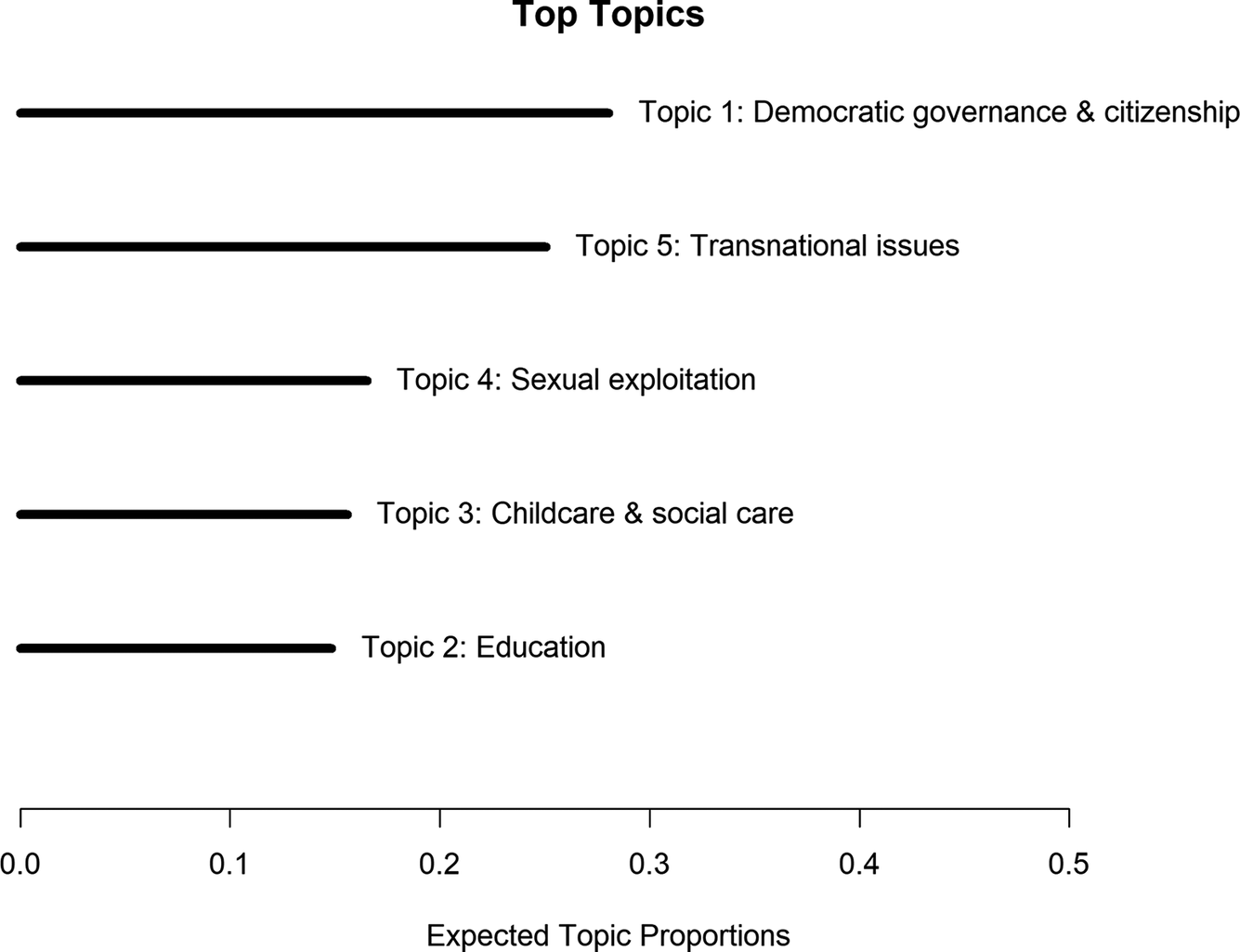

This initial overview highlights a prioritization of equality and social policy. The structural topic model (STM) enables deeper exploration of how these words collectively form shared themes. The STM identified five distinct topics, each reflecting a different aspect of women’s parties’ concerns. Table 4 presents the 10 most frequent and exclusive terms associated with each topic, alongside the labels I assigned, while Figure 2 plots their prevalence within the full corpus of manifestos.

Table 4. STM topics and their top 10 most frequent and exclusive terms in women’s parties’ manifestos

Figure 2. Expected topic proportions of STM topics in women’s party manifestos, 1990–2020.

Taking each topic turn, Topic 1, “Democratic governance and citizenship,” is the most prevalent across all manifestos. The topic includes terms such as “civil,” “citizen,” “partici[pation],” and “state.” Parties in the thematic analysis sub-sample commonly linked the representation of women and minoritized groups with democratic legitimacy, as summarized in WOR’s (1993) battle cry: “Without women there is no democracy!”

Two topics emerged relating to social policy. Topic 2 labeled “Education,” clusters terms such as “school” and “knowledge” alongside “municip[al]” and “public_transport.” Although terms related to municipal governance feature, I have assigned the label “Education” because further investigation of the context of terms such as “anti,” “racism,” and “lgbtq” in manifestos show that they are prevalent in several feminist parties’ education policies.Footnote 8 For example, advocating a norm critical curriculum:

Reduce sexual harassment with norm-critical education, stop racism from getting a hold in the everyday life of young people and improve the study results of boys by dismantling harmful masculinity norms, such as anti-education attitudes and low levels of reading. (FP 2019)

Thus, the STM appears to have clustered some terms within this topic from a smaller number of women’s parties’ platforms, although broader thematic terms like “educ[ation]” and “school” were among the top 30 relatively frequent terms in the full corpus (Table 3). Meanwhile, Topic 3, “Childcare and social care,” further evidences women’s parties shared concern with social care and childcare policies, alongside terms relating to equal parenting, such as “parental_leave.”Footnote 9

Two additional topics uncovered by the STM move beyond issues identified in the initial frequency analysis. Topic 4, “Sexual exploitation.” groups together terms relating to exploitation and violence toward women (“sexist_viol[ence]” and “prostitut[ion]”) alongside themes of patriarchy and discrimination (“sexist,” “male,” and “patriarch”). While the term “violenc[e]” featured prominently within the full sample of women’s party manifestos (Table 3), it notably only entered the most frequently mentioned terms in manifestos published after 2010 (Figure 1). This suggests a more recent focus on gender-based violence among women’s parties.

Finally, Topic 5, labeled “Transnational issues,” groups terms relating to transnational governance (“europe,” “global”) and policy areas such as security (“security,” “militari”), environmental protection (“climate”), and humanitarian concerns (“asylum”). Interestingly, these transnational issues did not appear among the most frequent terms in either the full corpus (Table 3) or any individual decade (Figure 1). Nonetheless, the term “security” was mentioned by 13 of the 20 parties represented in the dataset, and thematic analysis found several parties explicitly promoting foreign policy pledges:

Strengthening the international authority of Russia, developing an equal, mutually beneficial cooperation with CIS countries, and other foreign states in the interests of stability, peace and security. (WOR 1993)

Finland must act to prevent military threats, to strengthen arms control and to further disarmament. (FP 2019)

In contrast, other key terms in this topic, such as “environ[ment]” and “asylum,” were predominantly emphasized by self-identified feminist parties. This suggests that while the “Transnational issues” topic is internally coherent, it may not represent a universally shared concern across all women’s parties.

Combining quantitative and qualitative text analysis techniques, I have identified two core shared issue concerns emphasized in the women’s parties’ manifestos: (i) the pursuit of equal rights for women and minoritized groups and (ii) the promotion of social policy oriented toward social justice. These findings substantiate the definition of the women’s party family ideology provided by Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin (Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020, 13) as a “desire for gender equality… and a pro-women perspective on social justice.” However, the presence of more distinct topics and framings also offers early indication of significant differences in issue concern across party type. Therefore, I now address my second research question, testing whether there are systematic differences in issue concern between essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties.

Differences Between Essentialist Women’s Parties and Feminist Parties

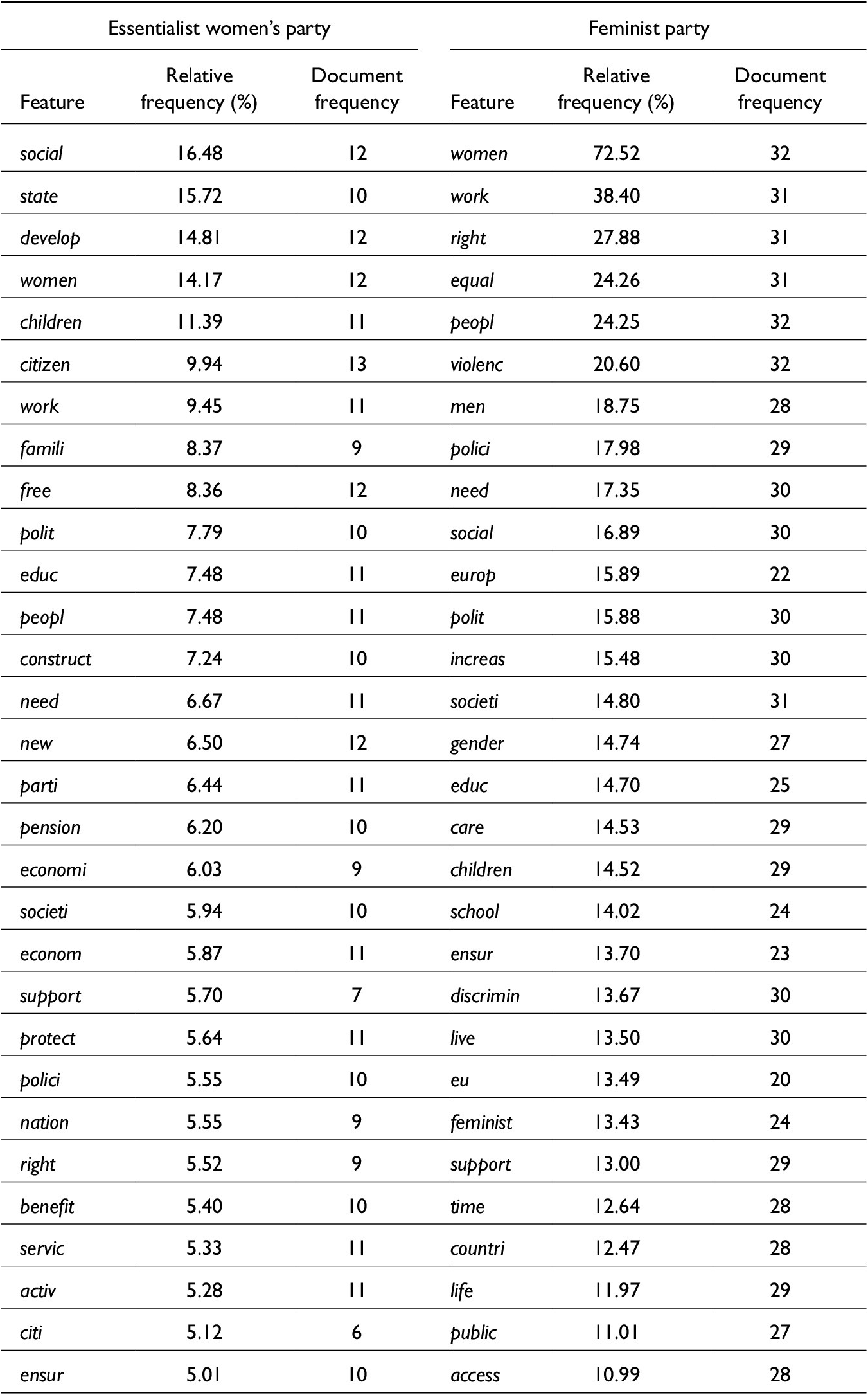

As an initial exploration, I first compare the relative frequency of terms in essentialist women’s party and feminist party manifestos (Table 5). These results first highlight the shared emphasis of equality issues across both party types. Among the most frequently mentioned terms in essentialist women’s party manifestos are “women,” “right,” “protect,” and “free.” Feminist party manifestos similarly emphasize terms such as “women,” “gender,” “equal,” and “discrimin[ation].”

Table 5. Top 30 relatively frequent terms in essentialist women’s party and feminist party manifestos, 1990–2020

However, qualitative examination reveals notable differences in the framing of these shared concerns. Essentialist women’s parties predominantly focus on protection and securing material benefits for minoritized groups, emphasizing diversity and tolerance. For example, WOR (1993) shaped their economic policy around the “labor interests of youth, women, including pregnant women and nursing mothers, single parents with children, persons of pre-retirement age, disabled people.” In comparison, feminist parties frequently adopt an intersectional framework, emphasizing the structural nature of discrimination:

Our policies aim to recognise and address the fact that many women experience additional inequalities due to the intersections of socio-economic status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, immigration status and gender identity. (WEP 2017)

These differences become even clearer when examining specific policy proposals. While social policy issues like childcare feature prominently across all manifestos, the positions taken by essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties reflects the distinction between practical and strategic gender interests (Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985; Shin Reference Shin2020). Both prioritize improved childcare provision, particularly for vulnerable women, but feminist parties explicitly link these policies to broader structural critiques of gender inequality:

In all member countries, it is much more time women spend performing household chores and caring for other people than employed by men. In particular, Spanish women spend four more hours each day than they do in such tasks. (IF 2009)

We all need care at some point in our lives. Yet the old political parties treat care as separate from the economy, as if our communities and businesses could survive without the paid and unpaid care work that is mainly undertaken by women. (WEP 2017)

By contrast, essentialist women’s parties focus primarily on practical interventions through existing systems, such as increases in maternity pay and welfare benefits to single mothers (POBW 2013).Footnote 10

Contextual factors, including the specific country-level provision of services and historical development of feminist discourses, undoubtedly influence these differences (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010). For instance, essentialist women’s parties emerging in post-Soviet Eastern Europe in the 1990s had arguably less exposure to the language of intersectionality and structural discrimination compared to more contemporary Western European parties. Indeed, some essentialist women’s parties did promote policies focused on the additional inequalities faced by some women:

The Women’s Coalition will continue to prioritise women’s needs for housing and social services -- a key factor in their ability to remove themselves and their children out of violent situations. (NIWC 1998)

The amount of family monthly benefits received by the uninsured mothers to raise a child in the first year, be provided with the changed from 100 BGN to the equivalent of the minimum wage (POBW 2013)

Nevertheless, the quantitative and qualitative analyses consistently indicate that feminist discourse and broader engagement with structural gender inequality is predominantly absent from essentialist women’s parties’ manifestos. Explicit mentions of “feminist” and “feminism” appear exclusively in the feminist parties manifestos in my sample.Footnote 11 This cannot solely be attributed to historical or regional factors, as parties like Iceland’s Kvennalistin (Women’s List) or Germany’s Die Frauen (The Women), active in the 1980s and 1990s, openly identified as feminist. Meanwhile, some Eastern European essentialist parties like WOR faced criticism from feminist groups for their lack of engagement with feminist objectives at the time (Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003). Moreover, I find that this disengagement from feminist discourses persists into the 21st century in parties like POBW in Bulgaria. This sustained divergence highlights a fundamental distinction in how different women’s parties approach SRW — as a matter of social inclusion or systemic transformation.

Beyond issue framing, Table 5 also indicates clear differences in issue focus. Essentialist women’s party manifestos highlight economic concerns (“econom” and “economi,” “pension”), whereas feminist party manifestos place greater emphasis on gender-based “violenc[e].” Thus, the initial differences in issue emphasis identified in the full dataset appear closely aligned with party type, rather than solely temporal variations (Figure 1).

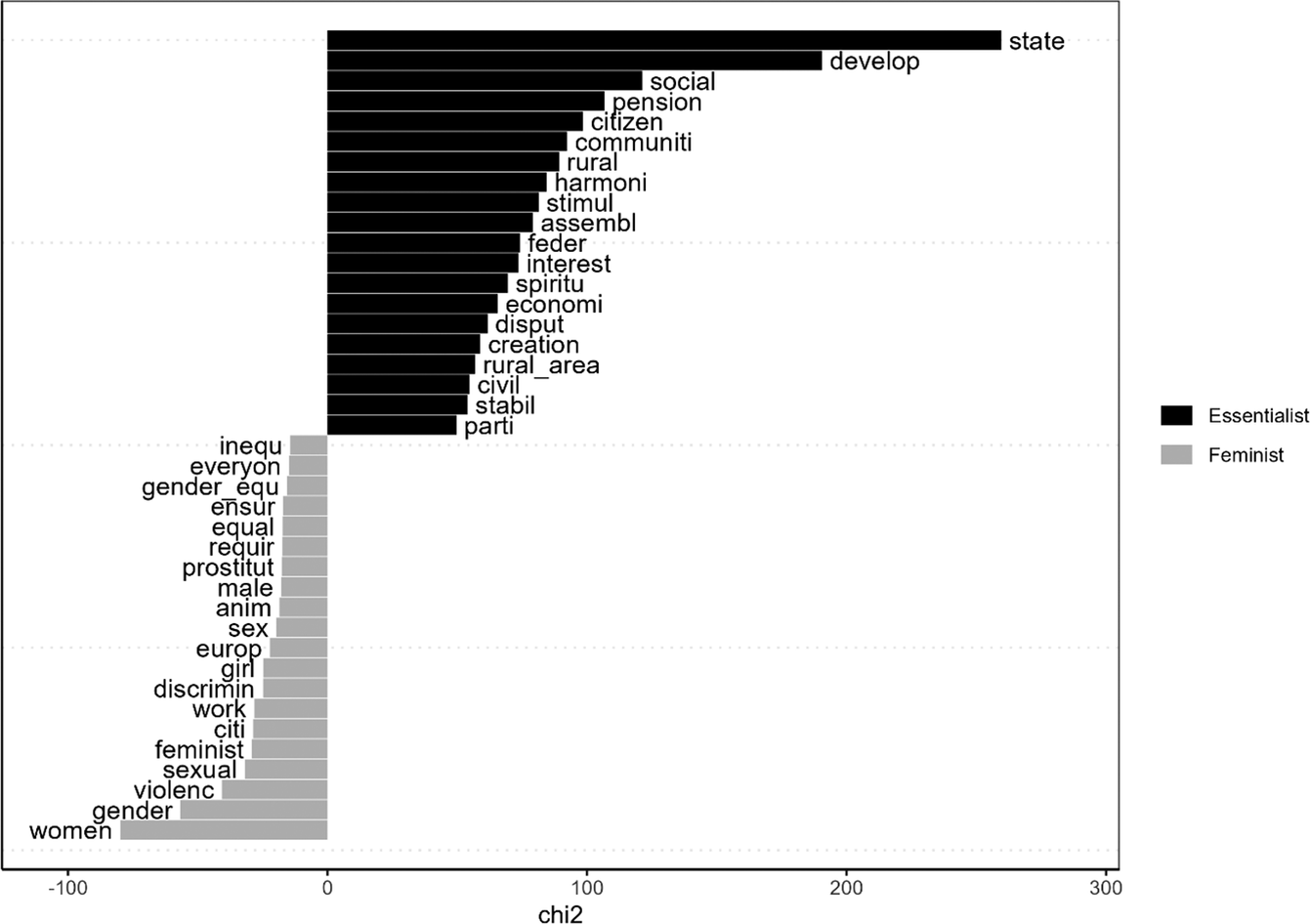

To deepen this analysis, I examine the most distinctively used terms in each party type’s manifestos. Keyness analysis identifies words that are significantly more prevalent in one set of manifestos compared to the other, revealing more precisely where the substantive differences in party agendas lie. Figure 3 presents the 20 words that appear significantly more frequently in essentialist women’s party versus feminist party manifestos.

Figure 3. Key words in essentialist women’s party and feminist party manifestos.

Keywords in essentialist women’s parties’ manifestos, such as “develop,” stabil,” “harmoni,” “communiti,” “feder[al],” and “state,” reflect a strong focus on state-building and governance. These parties prioritize issues around establishing and maintaining political stability and democratic institutions, likely influenced by their emergence in contexts of political transition and economic uncertainty (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016). Additionally, terms such as “economi,” “stimulus,” and “pension” indicate an emphasis on practical economic policy solutions.

In contrast, key words from the feminist party manifestos like “feminist,” “gender_equ,” and “discrimination” mark their distinct ideological orientation.”Footnote 12 Additionally, terms such as “sexual,” “violenc[e],” and “prostitut[ion]” underscore their distinctive emphasis on structural gender equality issues.

Although “Sexual exploitation” was identified as a shared topic in the STM (Table 4), further analysis highlights its differential salience across party types. Of the 665 total mentions of “violenc[e]” across all manifestos, only 16 occur in essentialist women’s parties’ manifestos, and these are primarily not related to sexual or gender-based violence.Footnote 13 For example, the Belarusian party Nadzeya (Hope) (1995) sought to “protect citizens from preaching inhumane ideas, violence and immorality.”

There are, however, two notable exceptions, where essentialist women’s parties do explicitly reference sexual or domestic violence. The NIWC (2003) states: “There are 12 domestic violence assaults every day in Northern Ireland and a more proactive strategy is needed to protect and support the cycle of violence.” Whereas WOR (1995) discuss the need for a “system of rehabilitation for women and children affected from violence including in the family.”

Despite these exceptions, gender-based violence remains more salient in feminist parties’ manifestos and as illustrated in the thematic analysis, feminist parties articulate more detailed policy responses to violence, explicitly addressing male violence toward women and children and advocating comprehensive structural reforms:

Ensure all women and children fleeing domestic abuse are offered a stable place to live and that they are never forced out of their homes unless it is necessary for their safety. (WEP 2017)

End violence against women. Make Finland the safest country for women in Europe by the year 2030. Implement a structural reform that creates permanent, expert and well-resourced support services on national as well as provincial and municipal levels. (FP 2019)

Moreover, feminist parties frame gender-based violence as symptomatic of broader patriarchal structures:

These are not individual or isolated phenomena. This is structural violence that limits women’s opportunities and restricts their freedom. Violence against women and girls is both a cause and a consequence of gender inequality. (WEP 2017)

The EU must establish a regulatory framework for all Member States based on the express recognition that violence against women is part of the social structure and therefore that all means must be available to change the individual or collective behaviours that help, protect and justify it. (IF 2009)

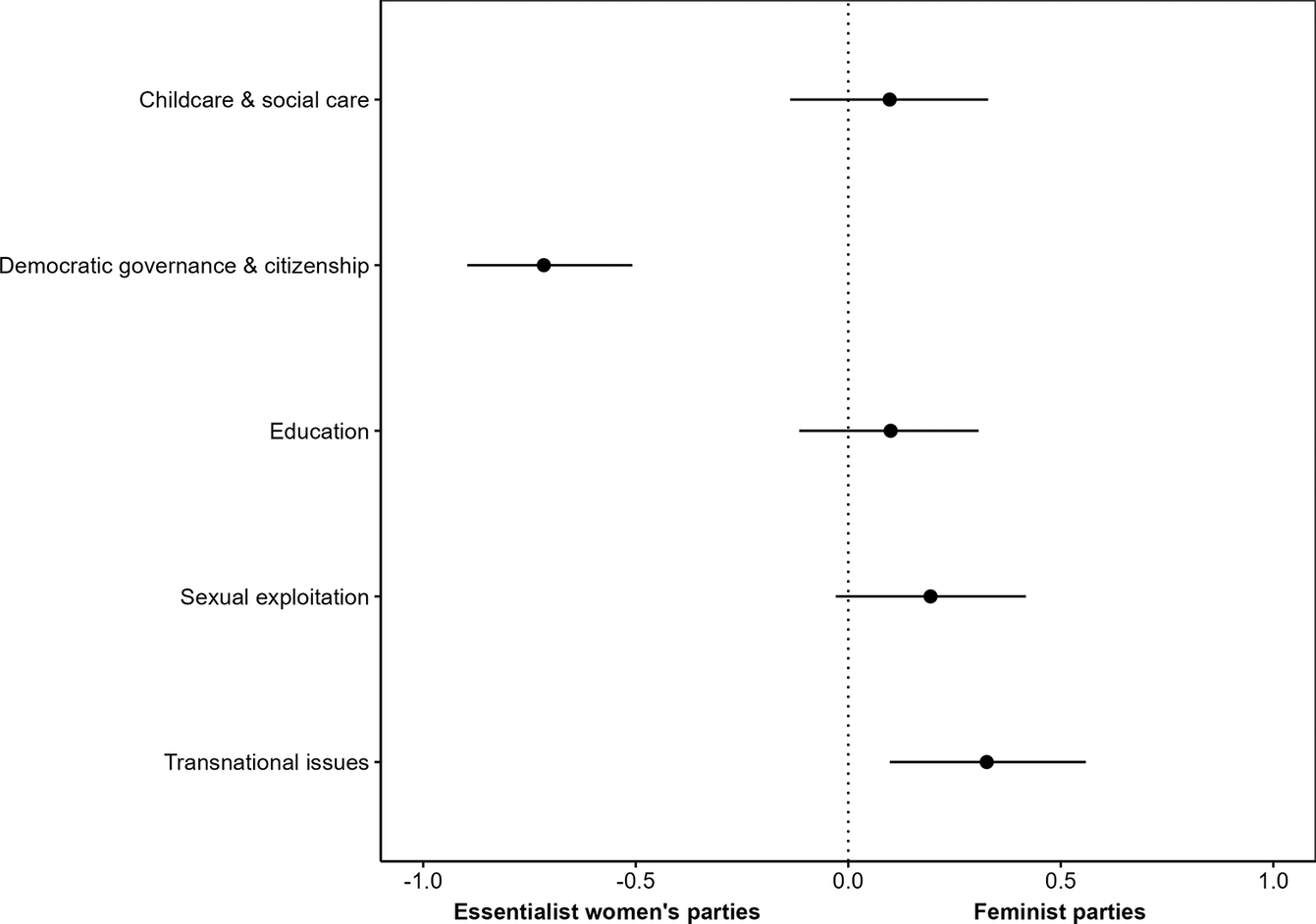

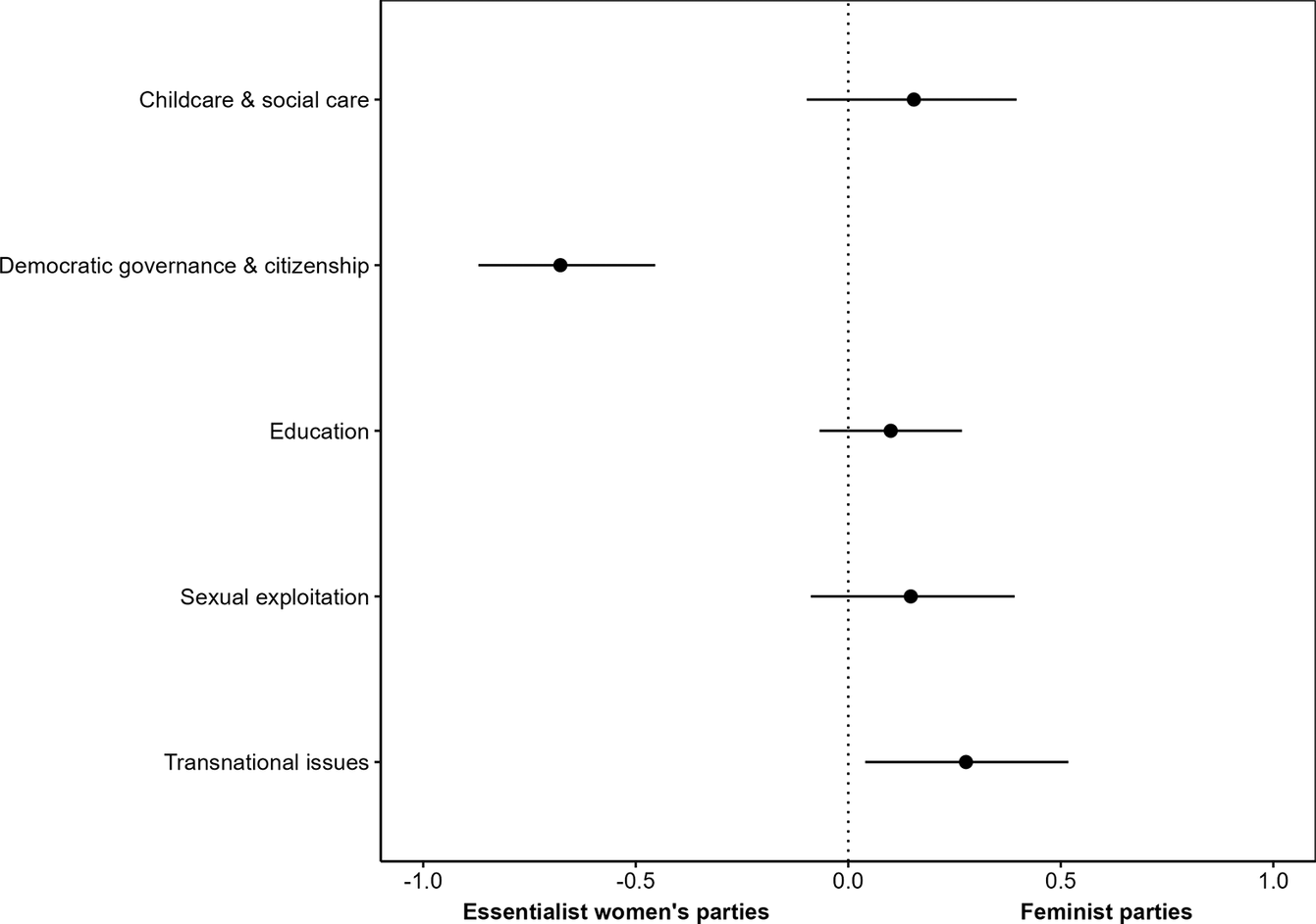

While keyness analysis highlights which words are disproportionately emphasized by each party type, it does not capture differences in emphasis of broader issue concerns. Thus, to systematically test thematic distinctions, I return to the STM and employ a linear regression to test whether the prevalence of the identified topics significantly differs between essentialist women’s parties’ and feminist parties’ manifestos. Figure 4 presents the differences in mean topic proportions, with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Difference in mean topic proportion between essentialist women’s parties’ and feminist parties’ manifestos, with 95% confidence intervals.

Three topics show no statistically significant difference in prevalence across the two-party types. Two of these — “Education” and “Childcare and social care” — align with my previous findings, reinforcing that social policy is a consistently salient issue for women’s parties, even if the specific framing and emphasis vary.

Notably, while “Sexual exploitation” appears more frequently in feminist party manifestos, this difference is not statistically significant. A potential explanation for this is that terms included in this topic (Table 4), such as “articl,” “propos,” “european,” and “european_parlia[ment],” are not exclusively linked to sexual exploitation. Instead, they reflect the broader legislative and institutional context in which feminist parties articulate their positions on this issue. For example, Spain’s IF references specific EU legal frameworks in advocating for stronger measures to combat gender-based violence:

The “Rights, Equality and Citizenship” programme finances, among others, those measures that contribute to the eradication of violence against women based on Article 168 of the TFEU [Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union] (IF, 2019)

However, because terms like “articl[e]” and “european_parlia[ment]” also feature in other policy areas, their lower exclusivity to this topic likely contributed to the lack of statistical significance.Footnote 14 Despite this, the combined quantitative and qualitative evidence robustly supports feminist parties’ heightened emphasis on gender-based violence in comparison to essentialist women’s parties.

Meanwhile, two topics do exhibit statistically significant differences in prevalence across party type. First, “Democratic governance and citizenship” is more prevalent in essentialist women’s party manifestos (p < 0.001). This provides empirical substantiation to previous research, which has linked essentialist women’s parties’ emergent contexts to issue platforms focused on securing women’s fundamental democratic rights (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003). My findings extend on this literature by demonstrating that that democratic governance and citizenship remains a core concern of essentialist women’s parties even beyond their emergence in 1990s Eastern Europe.

Second, “Transnational issues” is statistically significantly more prevalent in feminist party manifestos (p < 0.01). Drawing from the thematic analysis, I find that feminist parties are particularly concerned with human security. Feminist actors have long engaged with the concept of human security, advocating a focus on the intersectional impacts of transnational threats on marginalized groups, including women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ+ communities (Hudson Reference Hudson2005). This approach is particularly well-established in the Nordic region, where the Social-Democratic-Green government in Sweden launched a feminist foreign policy in 2014 to institutionalize gender equality in international relations (Ministry for Foreign Affairs 2018, 9).Footnote 15 However, my findings indicate that human security is a shared concern across feminist parties in multiple European contexts:

Human security to the forefront of security policy. Shift the focus from armed defense of territories towards a broader concept of security, so that we can better prepare for crises and new societal threats. (FP 2019)

Armed conflict and wars bring high suffering to civilians, an estimated 90% of victims are not contenders. (IF 2009)

Use the UK’s position in the Security Council to promote gendered analysis in conflict resolutions. (WEP 2017)

This topic also includes terms relating to “climate_change,” another issue that is present in both essentialist women’s parties’ and feminist parties’ manifestos but framed distinctively differently. While essentialist women’s parties engage with environmental issues within a broader concern for community development:

The Women’s Coalition supports planning policies which reflect the need to protect the environment, while allowing people to live and work in rural areas. (NIWC 1998)

Consistent and permanent actions for restoration, preservation, reproduction and improvement of environmental qualities. (POBW 2013)

Feminist parties explicitly link climate change to human security and structural inequalities:

Climate change is an issue of human security. (FP 2019)

We are affected by the development of cities and the distance from spaces of work and living, decisions about sustainable transport or the assessment of social factors that influence access to environmental goods and services, or roles and responsibilities that may be assigned differently to men and women. (IF 2009)

This finding provides compelling evidence that human security is an issue concern exclusive to feminist parties, further corroborated by the inclusion of terms like “feminist” and “lgbtqia” in the topic. However, the presence of terms like “global” and “europ” in Topic 5 raises an alternative explanation: the STM may have clustered transnational issues particularly salient in manifestos produced for EP elections. Notably, all the EP manifestos in my dataset were produced by feminist parties (Table 1). Therefore, to assess whether election type is a confounding factor in my results, I repeated the STM analysis with election type as an additional covariate. Figure 5 confirms that when election type is included, “Transnational issues” remains statistically significantly more prevalent in feminist parties’ manifestos (p < 0.05). Therefore, both the quantitative and qualitative analyses suggest that this is indeed an exclusive issue concern of feminist parties.

Figure 5. Mean difference in topic proportion between essentialist women’s party and feminist party manifestos, controlling for election type, with 95% confidence intervals.

Notes: Election type variables held at median value

Nevertheless, election type likely influences feminist parties’ issue emphasis and framing. Previous research suggests that parties adapt their issue emphasis across first- and second-order elections (Braun and Schmitt Reference Braun and Schmitt2020; Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2014). This raises questions about the extent to which feminist parties’ engagement with transnational issues reflects ideological commitment versus strategic adaptation to the electoral playing field. For example, the creation of FUN and the development of a common platform of issues for the 2019 EP elections indicates strategic behavior aimed at increasing the salience of specific issues on the European policy agenda.

Figure 5 also confirms that the “Democratic governance and citizenship” topic remains significantly more prevalent in essentialist women’s party manifestos when election type is included in the model (p < 0.001). This finding reaffirms the connection between the characteristics of many essentialist women’s parties’ emergent conditions and their more narrow issue focus in securing women’s material needs. Nevertheless, the differences in collective emphasis of specific issues that cut across contexts — such as gender-based violence by feminist parties compared to economic policy by essentialist women’s parties — demonstrates the value in differentiating women’s parties based on their issue concerns and broader approach to SRW.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has presented, to my knowledge, the first comparative empirical analysis of women’s parties’ issue concerns using the most comprehensive dataset of party manifestos to date. The results provide empirical evidence that women’s parties form a cohesive party family while also exhibiting meaningful internal differentiation. First, I demonstrated that European women’s parties share two core concerns in (i) social justice for women and minoritized groups and (ii) social policy, particularly in areas which disproportionately affect women within their gendered socialized roles. This empirically substantiates Cowell-Meyers, Evans, and Shin’s (Reference Cowell-Meyers, Evans and Shin2020, 13) definition of the shared ideology of the women’s party family as centered on “gender equality…and a pro-women perspective on social justice.” These findings challenge the reductive categorization of women’s parties as single-issue parties (Wagner Reference Wagner, Carter, Keith, Sindre and Vasilopoulou2023), demonstrating that they apply a social justice perspective across a broad range of issues. This raises critical questions about their primary electoral competitors and the constituencies they seek to represent.

To address these questions, this study also provides an empirical framework for further analysis. I demonstrate that essentialist women’s parties and feminist parties form two analytically distinct subgroups, differing in both issue emphasis and framing. While essentialist women’s parties focus on economic redistribution, welfare provision, and securing democratic legitimacy and stability, feminist parties near-exclusively emphasize human security and gender-based violence. Even within shared issue areas, feminist parties connect policies to structural gender inequalities, whereas essentialist women’s parties predominantly focus on material provisions. This distinction not only reinforces theoretical classifications proposed in past research (Shin Reference Shin2020) but also highlights how different visions of SRW translate into substantive policy agendas.

A major finding is feminist parties’ unique engagement with transnational feminist concerns, particularly human security, climate change, and asylum. This issue emphasis suggests that they are not only responding to national policy debates but also positioning themselves within wider feminist advocacy movements that operate across borders (Kelly-Thompson et al. Reference Kelly-Thompson, Lusvardi, Forester and Weldon2024). This an expanded conceptualization of SRW in two ways. First, it moves beyond national policy concerns, framing gender equality as a structural global challenge that requires transnational solutions. Second, it expands beyond women as a constituency. While essentialist women’s parties seek to represent women (particularly those facing material disadvantage), feminist parties represent a wider vision of feminism — promoting an intersectional vision of equality that incorporates LGBTQ+ rights, anti-racism, and economic justice.

This transnational focus is reflected in feminist parties’ electoral strategies. The formation of FUN for the 2019 EP elections and the adoption of shared branding and the “Feminist Initiative” label by parties across Europe in the 2010s suggests an attempt to construct a unified European feminist political movement, operating within electoral institutions. This transnational coordination meets a key criterion for defining party families (Mair and Mudde, Reference Mair and Mudde1998), reinforcing the argument that feminist parties share an ideological and structural basis beyond individual national contexts. At the same time, this engagement could be understood as a strategic response to the growing influence of far-right nationalism, which similarly operates through transnational networks (Heft et al. Reference Heft, Pfetsch, Voskresenskii and Benert2023) and increasingly mobilizes gender issues (Reinhardt, Heft, and Pavan Reference Reinhardt, Heft and Pavan2024).

While these patterns of issue emphasis suggest an ideological divergence, they are also shaped by regional and historical contexts. The distinctions I find map onto broader regional patterns identified in past research which has, for example, linked the material focus of Eastern European to post-transition political instability (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2016; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2003). However, my findings suggest that these differences are not solely contextual. The long-standing distinction between advocating systemic transformation versus securing women’s inclusion, recognized in scholarship on women’s movements (Alvarez Reference Alvarez1990; Beckwith Reference Beckwith2000; Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985, Reference Molyneux1988) and theorized in work on women’s parties (Shin Reference Shin2020), is empirically substantiated in this study. More broadly, this demonstrates that classifying parties by their issue focus, rather than emergent contexts, offers a more flexible framework for future comparative analysis.

These findings contribute to SRW literature that expands the scope of who is considered a “critical actor” in women’s representation beyond individual legislators (Mackay Reference Mackay2008; Weldon Reference Weldon2002). Gender party politics scholarship has made significant contributions to understanding how mainstream parties engage with gender issues (Childs, Webb, and Marthaler Reference Childs, Webb and Marthaler2010; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2019; Sanders, Gains, and Annesley Reference Sanders, Gains and Annesley2021; Sanders and Gains Reference Sanders and Gains2024) and case studies have demonstrated feminist parties’ agenda-setting role (Cowell-Meyers Reference Cowell-Meyers2017). Establishing women’s parties’ core issue concerns provides foundation to systematically and comparatively assess their impact on mainstream party competition. Future research should examine whether — and how — feminist parties influence mainstream parties’ adoption of pro-gender equality positions, particularly in contexts where far-right parties are mobilizing gender as a site of ideological contestation. Including feminist parties in these analyses is crucial for integrating gender perspectives into mainstream party politics scholarship (Kenny et al. Reference Kenny, Bjarnegård, Lovenduski, Childs, Evans and Verge2022).

Beyond party competition, this study contributes to understanding how parties across the political spectrum engage with women’s issues. Applying the broader framework of inclusion versus systemic change (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Molyneux Reference Molyneux1985) through computational text analysis allows for large-scale comparative analysis of whether — and how — the gendered issue frames introduced by women’s parties are adopted by mainstream parties. This can be traced through parties’ rhetorical commitments in manifestos and speeches to tangible policy implementation (Erikson Reference Erikson2015).

Finally, the findings raise important questions about the challenges women’s parties face in consolidating an electoral base that reflects the heterogeneity of women’s interests. Essentialist women’s parties’ focus on localized material inequalities may limit their broader appeal, while feminist parties’ expansive, ideologically driven issue concerns may be too diffuse to engage voters with immediate socioeconomic needs. Future research could further explore the ideological diversity within women’s parties, examining how different strands of feminism shape their policy agendas and electoral strategies. Understanding how women’s parties balance ideological cohesion with electoral viability will be critical to assessing their long-term role in gender and party politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X2510010X.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, LL, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The research in this article was conducted as part of a PhD at Newcastle University. I would like to sincerely thank Maarja Lühiste and Karen Ross for their invaluable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. I am also grateful to participants at the ECPR Joint Sessions, COMPTEXT Conference, and Elections, Public Opinion and Parties Annual Conference. Finally, I would like to express my appreciation to the three anonymous reviewers and the editor, Mona Lena Krook, for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Ethics approval statement

Approval was attained from Newcastle University Faculty of Humanity and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 18317/2019).

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council funded NINE Doctoral Training Partnership [grant number ES/P000762/1].